Disruption of Calcium Homeostasis in Human Spermatozoa: Implications on Mitochondrial Bioenergetics, ROS Production, Phosphatidylserine Externalization, and Motility

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Semen Collection and Analysis

2.2. Induction of Ca2+ Overload in Human Spermatozoa

2.3. Analysis of Intracellular Ca2+ Overload Induced by Ionomycin in Human Sperm Cells

2.4. Analysis of the Effect of Intracellular Ca2+ Overload on ROS Production in Human Spermatozoa

2.5. Analysis of the Effect of Intracellular Ca2+ Overload on Mitochondrial O2− Production in Human Spermatozoa

2.6. Analysis of the Effect of Intracellular Ca2+ Overload on ΔΨm in Human Spermatozoa

2.7. Analysis of the Effect of Intracellular Ca2+ Overload on ATP Levels in Human Spermatozoa

2.8. Analysis of the Effect of Intracellular Ca2+ Overload on cAMP Content in Human Spermatozoa

2.9. Analysis of the Effect of Intracellular Ca2+ Overload on Sperm Motility in Human Spermatozoa

2.10. Analysis of the Effect of Intracellular Ca2+ Overload on Phosphatidylserine (PS) Externalization in Human Spermatozoa

2.11. Analysis by Flow Cytometry

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Intracellular Ca2+ Overload Induced by Ionomycin in Human Sperm Cells

3.2. Intracellular Ca2+ Overload Effect on Cytosolic and Mitochondrial ROS Production in Human Spermatozoa

3.3. Intracellular Ca2+ Overload Effect on ΔΨm and ATP in Human Spermatozoa

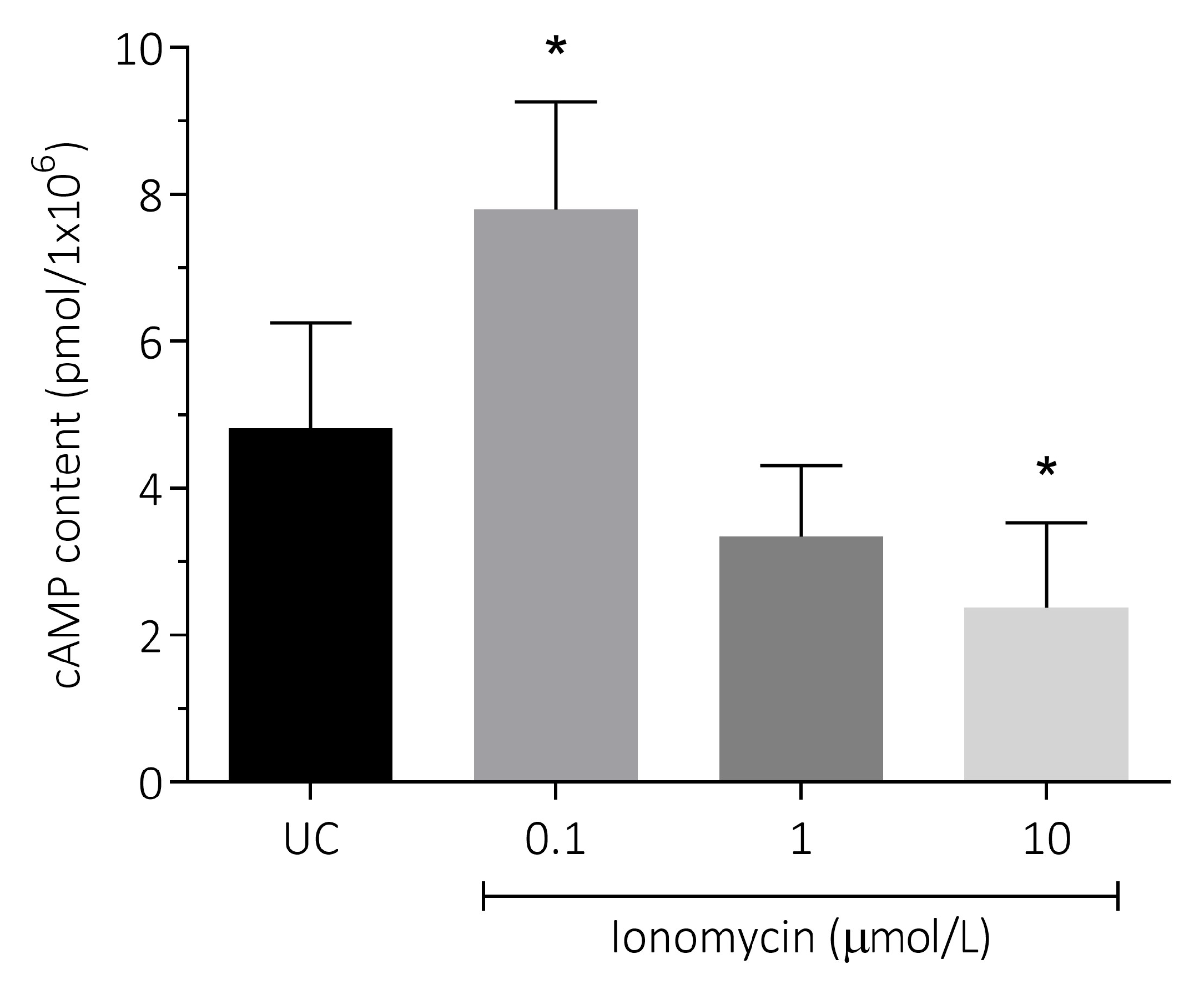

3.4. Effect of Intracellular Ca2+ Overload on cAMP Content in Human Spermatozoa

3.5. Effect of Intracellular Ca2+ Overload on Sperm Motility in Human Spermatozoa

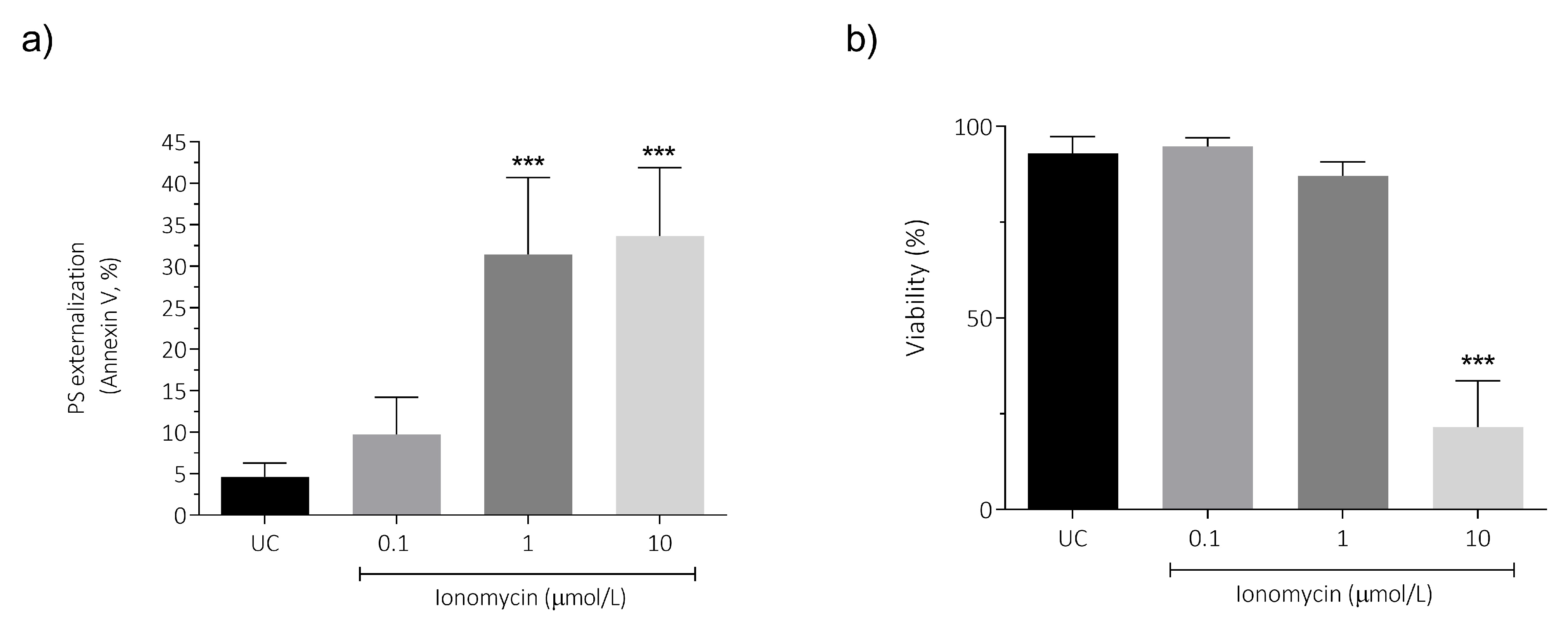

3.6. Intracellular Ca2+ Overload Effect on PS Externalization and Viability in Human Spermatozoa

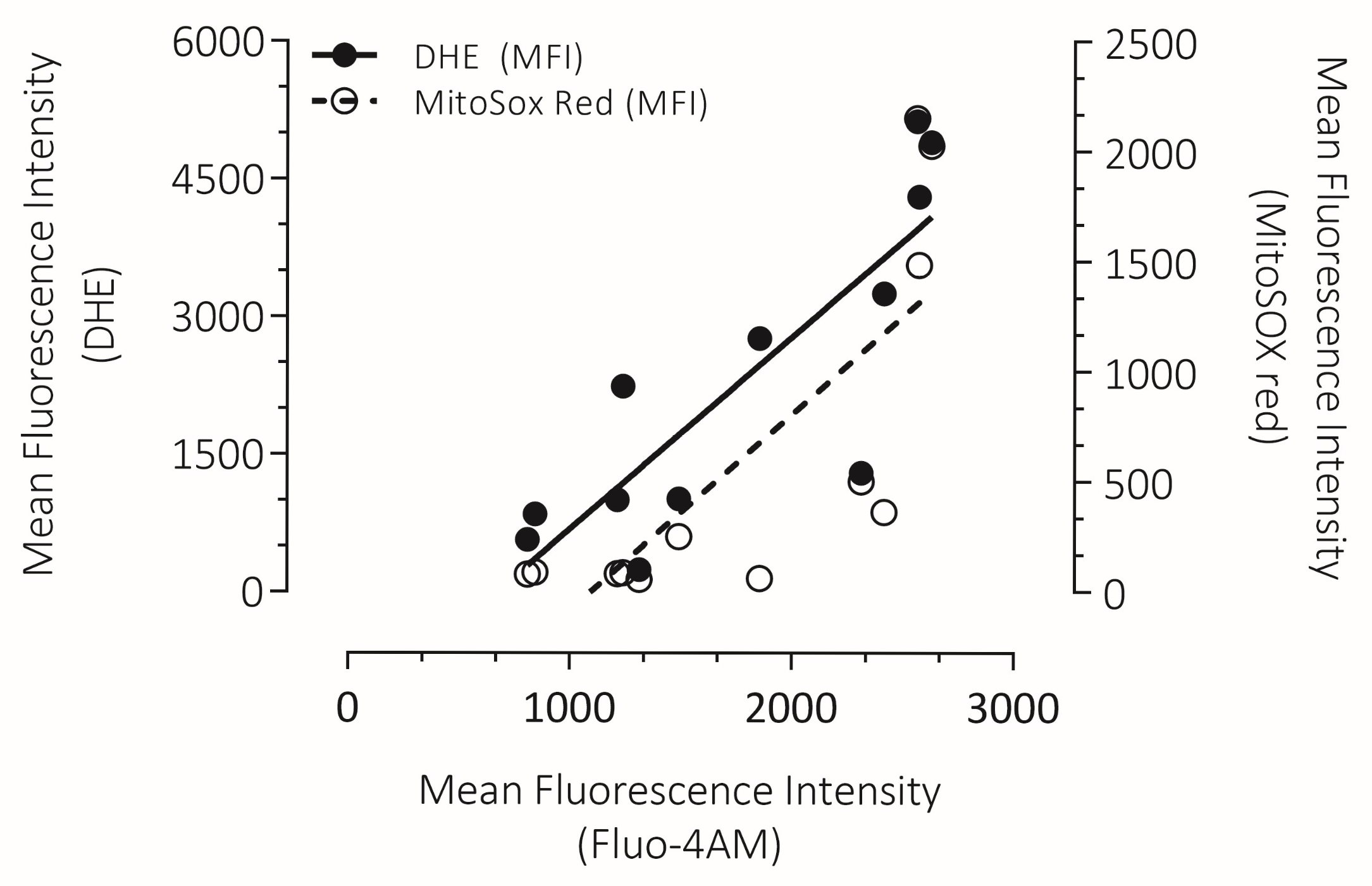

3.7. Correlation Between Intracellular Ca2+ Overload with Cytosolic ROS and mROS Production in Human Spermatozoa

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Definitions of infertility and recurrent pregnancy loss: A committee opinion. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 99, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zegers-Hochschild, F.; Adamson, G.D.; Dyer, S.; Racowsky, C.; de Mouzon, J.; Sokol, R.; Rienzi, L.; Sunde, A.; Schmidt, L.; Cooke, I.D.; et al. The International Glossary on Infertility and Fertility Care, 2017. Fertil. Steril. 2017, 108, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, C.M.; Thoma, M.E.; Tchangalova, N.; Mburu, G.; Bornstein, M.J.; Johnson, C.L.; Kiarie, J. Infertility prevalence and the methods of estimation from 1990 to 2021: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Open 2022, 2022, hoac051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Shrivastava, D. Psychological Problems Related to Infertility. Cureus 2022, 14, e30320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkodziak, P.; Wozniak, S.; Czuczwar, P.; Wozniakowska, E.; Milart, P.; Mroczkowski, A.; Paszkowski, T. Infertility in the light of new scientific reports—Focus on male factor. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. AAEM 2016, 23, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, A.; Mulgund, A.; Hamada, A.; Chyatte, M.R. A unique view on male infertility around the globe. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2015, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, C.R.; Meyers, S. The sperm mitochondrion: Organelle of many functions. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2018, 194, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Parekh, N.; Panner Selvam, M.K.; Henkel, R.; Shah, R.; Homa, S.T.; Ramasamy, R.; Ko, E.; Tremellen, K.; Esteves, S.; et al. Male Oxidative Stress Infertility (MOSI): Proposed Terminology and Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Idiopathic Male Infertility. World J. Men’s Health 2019, 37, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, R.J. Not every sperm is sacred; a perspective on male infertility. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 24, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aitken, R.J.; Gibb, Z.; Baker, M.A.; Drevet, J.; Gharagozloo, P. Causes and consequences of oxidative stress in spermatozoa. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2016, 28, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalata, A.A.; Christophe, A.B.; Depuydt, C.E.; Schoonjans, F.; Comhaire, F.H. The fatty acid composition of phospholipids of spermatozoa from infertile patients. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 1998, 4, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aitken, R.J.; Clarkson, J.S.; Fishel, S. Generation of reactive oxygen species, lipid peroxidation, and human sperm function. Biol. Reprod. 1989, 41, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, R.J.; Jones, K.T.; Robertson, S.A. Reactive oxygen species and sperm function--in sickness and in health. J. Androl. 2012, 33, 1096–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavriliouk, D.; Aitken, R.J. Damage to Sperm DNA Mediated by Reactive Oxygen Species: Its Impact on Human Reproduction and the Health Trajectory of Offspring. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2015, 868, 23–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bootman, M.D.; Collins, T.J.; Peppiatt, C.M.; Prothero, L.S.; MacKenzie, L.; De Smet, P.; Travers, M.; Tovey, S.C.; Seo, J.T.; Berridge, M.J.; et al. Calcium signalling—An overview. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2001, 12, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernyhough, P.; Calcutt, N.A. Abnormal calcium homeostasis in peripheral neuropathies. Cell Calcium 2010, 47, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görlach, A.; Bertram, K.; Hudecova, S.; Krizanova, O. Calcium and ROS: A mutual interplay. Redox Biol. 2015, 6, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, T.; Benson, J.C.; Tang, P.W.; Trebak, M.; Hempel, N. Crosstalk between calcium and reactive oxygen species signaling in cancer revisited. Cell Calcium 2025, 127, 103014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feissner, R.F.; Skalska, J.; Gaum, W.E.; Sheu, S.S. Crosstalk signaling between mitochondrial Ca2+ and ROS. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 2009, 14, 1197–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, T.I.; Jou, M.J. Oxidative stress caused by mitochondrial calcium overload. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1201, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treulen, F.; Uribe, P.; Boguen, R.; Villegas, J.V. Mitochondrial permeability transition increases reactive oxygen species production and induces DNA fragmentation in human spermatozoa. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 30, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirnamniha, M.; Faroughi, F.; Tahmasbpour, E.; Ebrahimi, P.; Beigi Harchegani, A. An overview on role of some trace elements in human reproductive health, sperm function and fertilization process. Rev. Environ. Health 2019, 34, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saling, P.M.; Storey, B.T.; Wolf, D.P. Calcium-dependent binding of mouse epididymal spermatozoa to the zona pellucida. Dev. Biol. 1978, 65, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, Z.; Aitken, R.J.; Sheridan, A.R.; Holt, B.; Waugh, S.; Swegen, A. The effects of oxidative stress and intracellular calcium on mitochondrial permeability transition pore formation in equine spermatozoa. FASEB Bioadv. 2024, 6, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanaei, H.; Keshtgar, S.; Bahmanpour, S.; Ghannadi, A.; Kazeroni, M. Beneficial effects of α-tocopherol against intracellular calcium overload in human sperm. Reprod. Sci. 2011, 18, 978–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffer, C.; Müller, A.; Egeberg, D.L.; Alvarez, L.; Brenker, C.; Rehfeld, A.; Frederiksen, H.; Wäschle, B.; Kaupp, U.B.; Balbach, M.; et al. Direct action of endocrine disrupting chemicals on human sperm. EMBO Rep. 2014, 15, 758–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen, 5th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- Quinn, P.; Kerin, J.; Warnes, G. Improved pregnancy rate in human in vitro fertilization with the use of a medium based on the composition of human tubal fluid. Fertil. Steril. 1985, 44, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedkova, E.N.; Sigova, A.A.; Zinchenko, V.P. Mechanism of action of calcium ionophores on intact cells: Ionophore-resistant cells. Membr. Cell Biol. 2000, 13, 357–368. [Google Scholar]

- Rossato, M.; Di Virgilio, F.; Rizzuto, R.; Galeazzi, C.; Foresta, C. Intracellular calcium store depletion and acrosome reaction in human spermatozoa: Role of calcium and plasma membrane potential. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2001, 7, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, D.C.; Bakowska, J.C. Determination of mitochondrial membrane potential and reactive oxygen species in live rat cortical neurons. J. Vis. Exp. 2011, 23, 2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaduto, R.C., Jr.; Grotyohann, L.W. Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential using fluorescent rhodamine derivatives. Biophys. J. 1999, 76, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uribe, P.; Boguen, R.; Treulen, F.; Sánchez, R.; Villegas, J.V. Peroxynitrite-mediated nitrosative stress decreases motility and mitochondrial membrane potential in human spermatozoa. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 21, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewangan, J.; Srivastava, S.; Mishra, S.; Pandey, P.K.; Divakar, A.; Rath, S.K. Chetomin induces apoptosis in human triple-negative breast cancer cells by promoting calcium overload and mitochondrial dysfunction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 495, 1915–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Mongillo, M.; Chin, K.T.; Harding, H.; Ron, D.; Marks, A.R.; Tabas, I. Role of ERO1-alpha-mediated stimulation of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor activity in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 186, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielecińska, A.; Kciuk, M.; Kontek, R. The Impact of Calcium Overload on Cellular Processes: Exploring Calcicoptosis and Its Therapeutic Potential in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam-Vizi, V.; Starkov, A.A. Calcium and mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation: How to read the facts. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2010, 20 (Suppl. S2), S413–S426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.; Chauhan, P.; Saha, B.; Kubatzky, K.F. Conceptual Evolution of Cell Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeste, M.; Fernandez-Novell, J.M.; Ramio-Lluch, L.; Estrada, E.; Rocha, L.G.; Cebrian-Perez, J.A.; Muino-Blanco, T.; Concha, I.; Ramirez, A.; Rodriguez-Gil, J.E. Intracellular calcium movements of boar spermatozoa during ‘in vitro’ capacitation and subsequent acrosome exocytosis follow a multiple-storage place, extracellular calcium-dependent model. Andrology 2015, 3, 729–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serres, C.; Feneux, D.; Berthon, B. Decrease of internal free calcium and human sperm movement. Cell Motil. Cytoskelet. 1991, 18, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelstein, M.; Etkovitz, N.; Breitbart, H. Ca(2+) signaling in mammalian spermatozoa. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2020, 516, 110953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, J.; Michelangeli, F.; Publicover, S. Regulation and roles of Ca2+ stores in human sperm. Reproduction 2015, 150, R65–R76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, P.C.; Satorre, M.M.; Beconi, M.T. Effect of two intracellular calcium modulators on sperm motility and heparin-induced capacitation in cryopreserved bovine spermatozoa. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2012, 131, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, L.; Han, X.; Wu, K.; Mei, G.; Wu, B.; Cheng, Y. The regulation role of calcium channels in mammalian sperm function: A narrative review with a focus on humans and mice. PeerJ 2024, 12, e18429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferramosca, A.; Provenzano, S.P.; Coppola, L.; Zara, V. Mitochondrial respiratory efficiency is positively correlated with human sperm motility. Urology 2012, 79, 809–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, A.I.; Griffiths, E.J.; Rutter, G.A. Regulation of ATP production by mitochondrial Ca(2+). Cell Calcium 2012, 52, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glancy, B.; Balaban, R.S. Role of mitochondrial Ca2+ in the regulation of cellular energetics. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 2959–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, J.; Reigada, D.; Mitchell, C.H.; Ren, D. CATSPER channel-mediated Ca2+ entry into mouse sperm triggers a tail-to-head propagation. Biol. Reprod. 2007, 77, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lishko, P.V.; Kirichok, Y.; Ren, D.; Navarro, B.; Chung, J.J.; Clapham, D.E. The control of male fertility by spermatozoan ion channels. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2012, 74, 453–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visconti, P.E.; Krapf, D.; de la Vega-Beltran, J.L.; Acevedo, J.J.; Darszon, A. Ion channels, phosphorylation and mammalian sperm capacitation. Asian J. Androl. 2011, 13, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.P.; Rajender, S. CatSper channel, sperm function and male fertility. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2015, 30, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordeeva, A.V.; Zvyagilskaya, R.A.; Labas, Y.A. Cross-talk between reactive oxygen species and calcium in living cells. Biochemistry 2003, 68, 1077–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookes, P.S.; Yoon, Y.; Robotham, J.L.; Anders, M.W.; Sheu, S.S. Calcium, ATP, and ROS: A mitochondrial love-hate triangle. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2004, 287, C817–C833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulda, S.; Debatin, K.M. Sensitization for anticancer drug-induced apoptosis by betulinic Acid. Neoplasia 2005, 7, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, J.E.; Gottlieb, R.A.; Green, D.R. Caspase-mediated loss of mitochondrial function and generation of reactive oxygen species during apoptosis. J. Cell Biol. 2003, 160, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.P. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem. J. 2009, 417, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camello-Almaraz, C.; Gomez-Pinilla, P.J.; Pozo, M.J.; Camello, P.J. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and Ca2+ signaling. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2006, 291, C1082–C1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, C.; Barrow, S.; Voronina, S.; Chvanov, M.; Petersen, O.H.; Tepikin, A. Modulation of calcium signalling by mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1787, 1374–1382. [Google Scholar]

- McCormack, J.G.; Halestrap, A.P.; Denton, R.M. Role of calcium ions in regulation of mammalian intramitochondrial metabolism. Physiol. Rev. 1990, 70, 391–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyssens, A.; Nowicky, A.V.; Patterson, L.; Crompton, M.; Duchen, M.R. The relationship between mitochondrial state, ATP hydrolysis, [Mg2+]i and [Ca2+]i studied in isolated rat cardiomyocytes. J. Physiol. 1996, 496, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lamirande, E.; Jiang, H.; Zini, A.; Kodama, H.; Gagnon, C. Reactive oxygen species and sperm physiology. Rev. Reprod. 1997, 2, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, S.; McCarron, J.G. The mitochondrial membrane potential and Ca2+ oscillations in smooth muscle. J. Cell Sci. 2008, 121, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piomboni, P.; Focarelli, R.; Stendardi, A.; Ferramosca, A.; Zara, V. The role of mitochondria in energy production for human sperm motility. Int. J. Androl. 2012, 35, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, A.; Sánchez, R.; Zambrano, F.; Uribe, P. Exogenous Oxidative Stress in Human Spermatozoa Induces Opening of the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore: Effect on Mitochondrial Function, Sperm Motility and Induction of Cell Death. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; Mann, T.; Sherins, R. Peroxidative breakdown of phospholipids in human spermatozoa, spermicidal properties of fatty acid peroxides, and protective action of seminal plasma. Fertil. Steril. 1979, 31, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, S.H.; Chao, H.T.; Chen, H.W.; Hwang, T.I.; Liao, T.L.; Wei, Y.H. Increase of oxidative stress in human sperm with lower motility. Fertil. Steril. 2008, 89, 1183–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremellen, K. Oxidative stress and male infertility--a clinical perspective. Hum. Reprod. Update 2008, 14, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, C.; Obert, G.; Deffosez, A.; Formstecher, P.; Marchetti, P. Study of mitochondrial membrane potential, reactive oxygen species, DNA fragmentation and cell viability by flow cytometry in human sperm. Hum. Reprod. 2002, 17, 1257–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, A.; Treulen, F.; Uribe, P.; Boguen, R.; Felmer, R.; Villegas, J.V. Effect of mitochondrial calcium uniporter blocking on human spermatozoa. Andrologia 2015, 47, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guthrie, H.D.; Welch, G.R. Effects of reactive oxygen species on sperm function. Theriogenology 2012, 78, 1700–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Wen, Y.; Wang, L.; Peng, Z.; Yeerken, R.; Zhen, L.; Li, P.; Li, X. Ca(2+) ionophore A23187 inhibits ATP generation reducing mouse sperm motility and PKA-dependent phosphorylation. Tissue Cell 2020, 66, 101381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzi, L.; Bravo-San Pedro, J.M.; Vitale, I.; Aaronson, S.A.; Abrams, J.M.; Adam, D.; Alnemri, E.S.; Altucci, L.; Andrews, D.; Annicchiarico-Petruzzelli, M.; et al. Essential versus accessory aspects of cell death: Recommendations of the NCCD 2015. Cell Death Differ. 2015, 22, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.J.; Reutelingsperger, C.P.; McGahon, A.J.; Rader, J.A.; van Schie, R.C.; LaFace, D.M.; Green, D.R. Early redistribution of plasma membrane phosphatidylserine is a general feature of apoptosis regardless of the initiating stimulus: Inhibition by overexpression of Bcl-2 and Abl. J. Exp. Med. 1995, 182, 1545–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, P.; Meriño, J.; Matus, C.E.; Schulz, M.; Zambrano, F.; Villegas, J.V.; Conejeros, I.; Taubert, A.; Hermosilla, C.; Sánchez, R. Autophagy is activated in human spermatozoa subjected to oxidative stress and its inhibition impairs sperm quality and promotes cell death. Hum. Reprod. 2022, 37, 680–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, R.J.; Baker, M.A. Causes and consequences of apoptosis in spermatozoa; contributions to infertility and impacts on development. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2013, 57, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dix, T.A.; Aikens, J. Mechanisms and biological relevance of lipid peroxidation initiation. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1993, 6, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushnareva, Y.; Newmeyer, D.D. Bioenergetics and cell death. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1201, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demaurex, N.; Distelhorst, C. Cell biology. Apoptosis--the calcium connection. Science 2003, 300, 65–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.R.; Galluzzi, L.; Kroemer, G. Cell biology. Metabolic control of cell death. Science 2014, 345, 1250256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sperm Motility Patterns | Ionomycin (µmol/L) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated Control | 0.1 | 1 | 10 | |

| Progressive Motility (%) | 30.6 ± 10.5 | 39.0 ± 9.7 | 18.9 ± 10.2 | 0 ± 0.0 * |

| Non-Progressive Motility (%) | 47.2 ± 8.5 | 42.4 ± 9.9 | 15.5 ± 15.8 * | 0 ± 0.0 ** |

| Immotile (%) | 22.2 ± 18.4 | 18.6 ± 11.3 | 65.5 ± 26 ** | 100 ± 0.0 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bravo, A.; Jofré-Fernández, I.; Boguen, R.; Sánchez, R.; Zambrano, F.; Uribe, P. Disruption of Calcium Homeostasis in Human Spermatozoa: Implications on Mitochondrial Bioenergetics, ROS Production, Phosphatidylserine Externalization, and Motility. Antioxidants 2026, 15, 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15020213

Bravo A, Jofré-Fernández I, Boguen R, Sánchez R, Zambrano F, Uribe P. Disruption of Calcium Homeostasis in Human Spermatozoa: Implications on Mitochondrial Bioenergetics, ROS Production, Phosphatidylserine Externalization, and Motility. Antioxidants. 2026; 15(2):213. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15020213

Chicago/Turabian StyleBravo, Anita, Ignacio Jofré-Fernández, Rodrigo Boguen, Raúl Sánchez, Fabiola Zambrano, and Pamela Uribe. 2026. "Disruption of Calcium Homeostasis in Human Spermatozoa: Implications on Mitochondrial Bioenergetics, ROS Production, Phosphatidylserine Externalization, and Motility" Antioxidants 15, no. 2: 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15020213

APA StyleBravo, A., Jofré-Fernández, I., Boguen, R., Sánchez, R., Zambrano, F., & Uribe, P. (2026). Disruption of Calcium Homeostasis in Human Spermatozoa: Implications on Mitochondrial Bioenergetics, ROS Production, Phosphatidylserine Externalization, and Motility. Antioxidants, 15(2), 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15020213