Black Sesame Pigment Ameliorates Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease via Modulation of the Gut–Liver Axis and HIF-1 Signaling Pathway

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Extraction and In Vitro Digestion of BSP and FBSP

2.2. Determination of Yield and Color Value

2.3. Characterizations of Pigments

2.4. 1H NMR Spectroscopy Analysis

2.5. Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy Analysis

2.6. In Vitro Simulated Digestion Methods

2.7. Animal Experiments

2.8. Fasting Blood Glucose

2.9. Liver Histology Examination

2.10. Determination of Plasma Biochemical Parameters

2.11. Network Pharmacology Analysis

2.12. LC-MS Metabolomics Analysis

2.13. Gut Microbiota Analysis

2.14. Human Liver Organoid Culture

2.15. Histology and Immunofluorescence Analysis

2.16. Oil Red Staining and Measurement of Lipid Accumulation

2.17. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

2.18. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Extraction and Structural Characterization of Pigment

3.2. The Protective Effects of Pigment on NAFLD

3.3. Network Pharmacology Analysis

3.3.1. Target Identification of BSP for NAFLD

3.3.2. KEGG and GO Enrichment Analysis of BSP for NAFLD

3.4. LC-MS Metabolomics Analysis

3.4.1. Multivariate Statistical Analysis

3.4.2. Differential Metabolites in Urine with Different Treatments

3.4.3. Joint Pathway Analysis of Targets and Metabolites

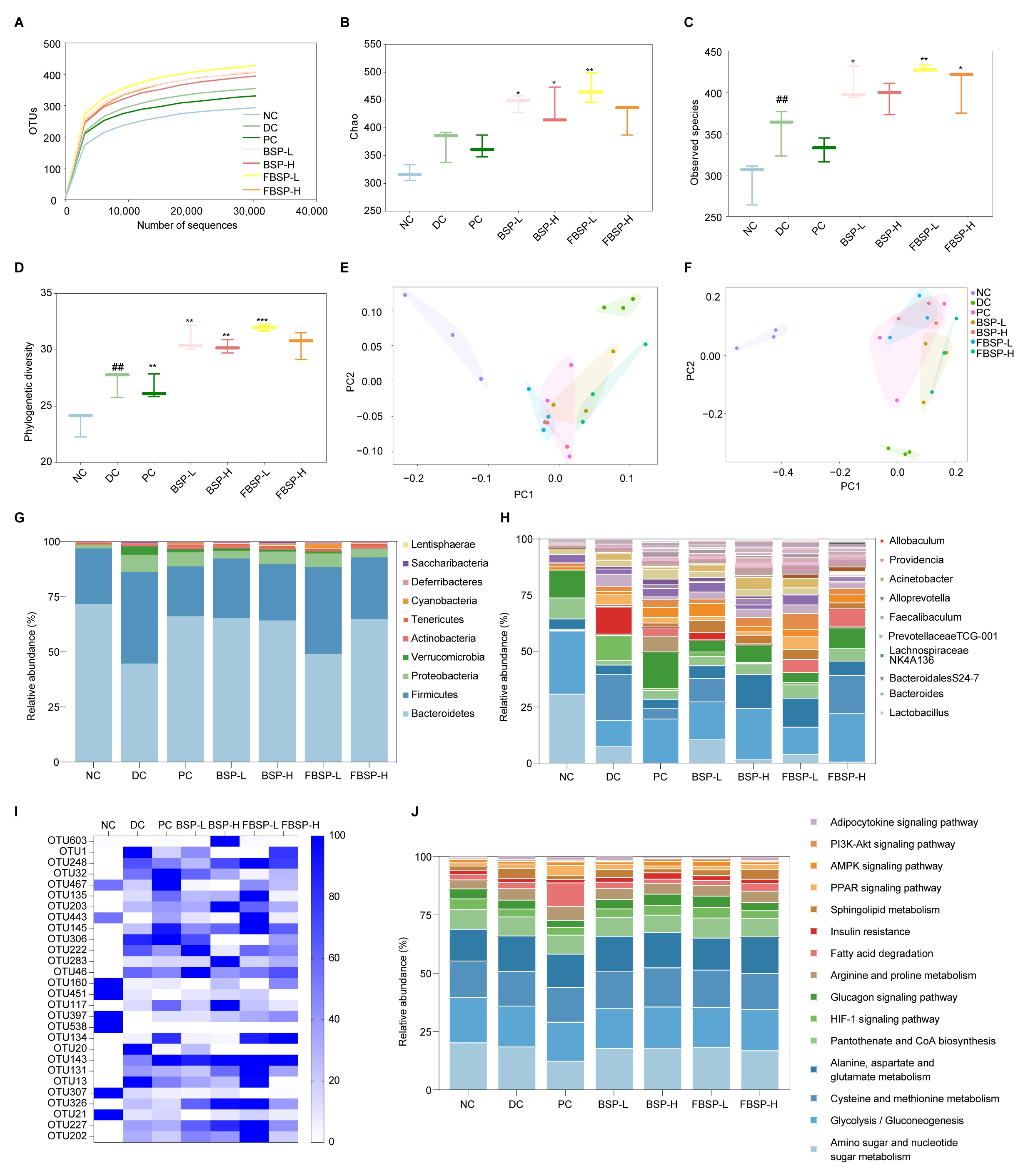

3.5. Gut Microbiota Analysis

3.5.1. Intake of BSP Improved the Gut Microbiota Diversity

3.5.2. Intake of BSP Reversed the Gut Microbiota Community

3.5.3. Potential Functions of Gut Microbiota

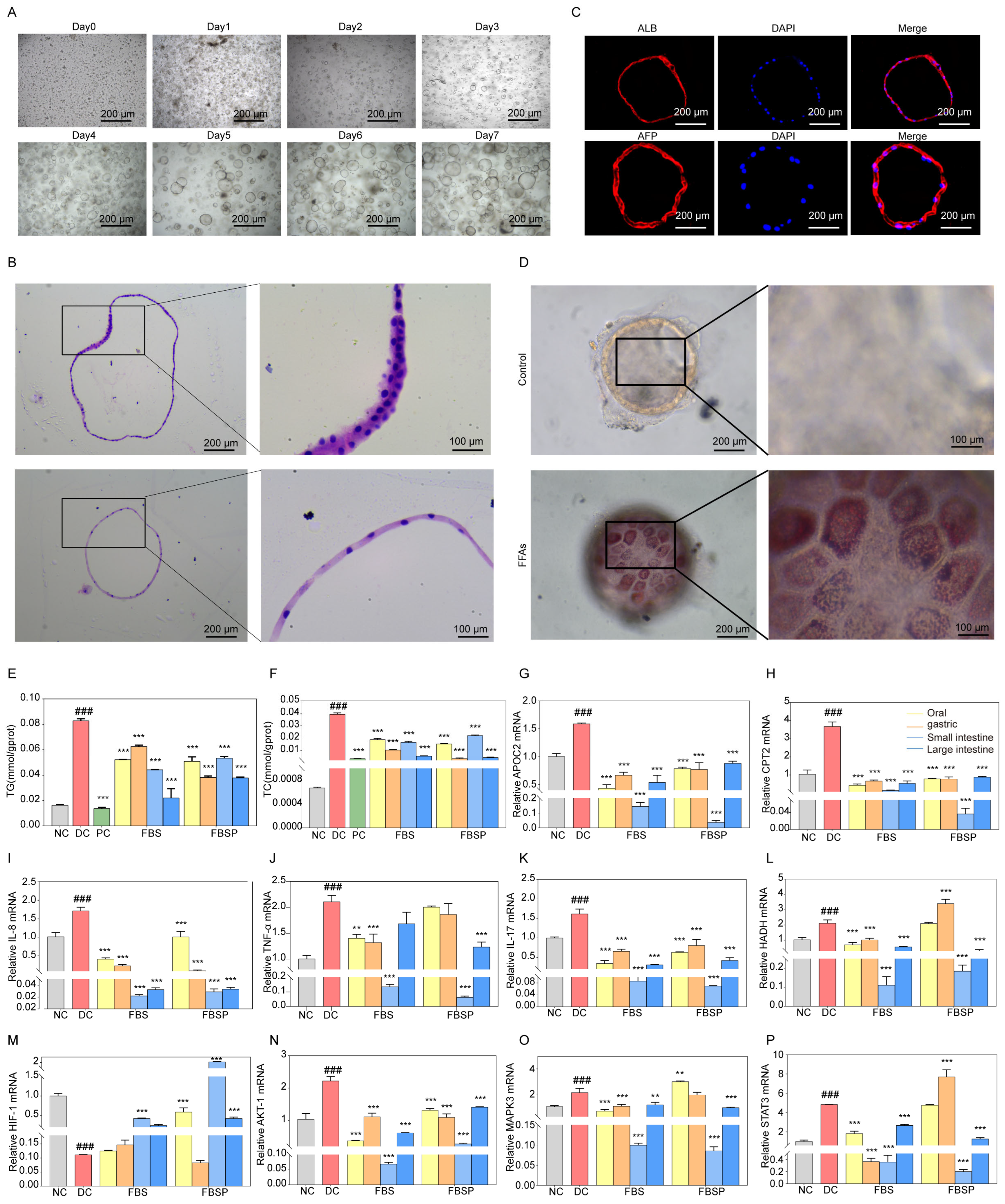

3.6. Liver Organoid Analysis

3.6.1. Establishment and Characterization of Human Liver Organoids

3.6.2. Effects of FBSP on Biomarkers of Lipid Metabolism and Inflammation

3.6.3. FBSP Modulates the Hepatic HIF-1 Pathway and Ameliorates NAFLD

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| APOC2 | apolipoprotein C2 | HFD | high-fat diet | NC | naive control |

| ALB | albumin | H&E | hematoxylin and eosin | NAFLD | non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| AFP | alpha-Fetoprotein | HADH | hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase | PCOA | principal coordinates analysis |

| AKT1 | serine/threonine kinase 1 | HIF1A | hif-1alpha | PCA | principal component analysis |

| BS | black sesame | IF | immunofluorescence | STZ | streptozotocin |

| BSP | black sesame pigment | IL-17 | interleukin-17 | SEM | mean ± standard error of the mean |

| CPT2 | carnitine palmitoyl transferase 2 | IL-18 | interleukin-18 | STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| FBSP | fired black sesame pigment | LC-MS | liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry | TG | triglyceride |

| FFAs | free fatty acids | MCODE | molecular complex detection | TC | total cholesterol |

| FMT | fecal microbiota transplantation | MAPK3 | mitogen-activated protein kinase 3 | TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

References

- Liu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Dong, R.; Liu, P.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Lai, X.; Cheong, H.-F.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Rutin ameliorated lipid metabolism dysfunction of diabetic NAFLD via AMPK/SREBP1 pathway. Phytomedicine 2024, 126, 155437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimer, N.; Choucair, I.; Wang, Z.; Nemet, I.; Li, L.; Gukasyan, J.; Weeks, T.L.; Alkhouri, N.; Zein, N.; Tang, W.H.W.; et al. Bile acids profile, histopathological indices and genetic variants for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease progression. Metabolism 2021, 116, 154457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Lin, X.; Abbasi, A.M.; Zheng, B. Phytochemical Contents and Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Activities of Selected Black and White Sesame Seeds. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 8495630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, T.; Fu, X.; Abbasi, A.M.; Zheng, B.; Liu, R.H. Phenolics content, antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of dehulled highland barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). J. Funct. Foods 2015, 19, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Li, M.; Jiang, N.; Gui, C.; Wang, Y.; An, Y.; Xiang, X.; Deng, Q. Black sesame seeds: Nutritional value, health benefits, and food industrial applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 153, 104740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Col, J.P.; de Lima, E.P.; Pompeu, F.M.; Araujo, A.C.; Goulart, R.d.A.; Bechara, M.D.; Laurindo, L.F.; Mendez-Sanchez, N.; Barbalho, S.M. Underlying Mechanisms behind the Brain-Gut-Liver Axis and Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD): An Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallianou, N.G.; Kounatidis, D.; Psallida, S.; Vythoulkas-Biotis, N.; Adamou, A.; Zachariadou, T.; Kargioti, S.; Karampela, I.; Dalamaga, M. NAFLD/MASLD and the Gut-Liver Axis: From Pathogenesis to Treatment Options. Metabolites 2024, 14, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masarone, M.; Troisi, J.; Aglitti, A.; Torre, P.; Colucci, A.; Dallio, M.; Federico, A.; Balsano, C.; Persico, M. Untargeted metabolomics as a diagnostic tool in NAFLD: Discrimination of steatosis, steatohepatitis and cirrhosis. Metabolomics 2021, 17, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, C.; Lin, H.; Xu, G.; Li, H.; Wang, C.; Chen, J.; Sun, J. Study on the Hepatoprotection of Schisandra chinensis Caulis Polysaccharides in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Rats Based on Metabolomics. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 727636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Xue, C.; Gu, X.; Shan, D.; Chu, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhu, H.; Chen, Z. Multi-Omics Characterizes the Effects and Mechanisms of CD1d in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Development. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 830702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Lu, J.; Wu, L.; Lin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Pi, W.; Cai, D.; et al. Integrative multi-omics unravels the amelioration effects of Zanthoxylum bungeanum Maxim. on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Phytomedicine 2023, 109, 154576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altyar, A.E.; Albadrani, G.M.; Farouk, S.M.; Alamoudi, M.K.; Sayed, A.A.; Mohammedsaleh, Z.M.; Al-Ghadi, M.Q.; Saleem, R.M.; Sakr, H.I.; Abdel-Daim, M.M. The antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic effects of sesamin against cisplatin-induced renal and testicular toxicity in rats. Ren. Fail. 2024, 46, 2378212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Zhang, T.; Liang, X.; Cheng, X.; Shi, F.; Yuan, H.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, X. Sesamin alleviates lipid accumulation induced by oleic acid via PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy in HepG2 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2024, 708, 149815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossou, S.S.K.; Xu, F.-t.; Dossa, K.; Zhou, R.; Zhao, Y.-z.; Wang, L.-h. Antioxidant lignans sesamin and sesamolin in sesame (Sesamum indicum L.): A comprehensive review and future prospects. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, D.A.; Mir, T.A.; Alzhrani, A.; Altuhami, A.; Shamma, T.; Ahmed, S.; Kazmi, S.; Fujitsuka, I.; Ikhlaq, M.; Shabab, M.; et al. Using Liver Organoids as Models to Study the Pathobiology of Rare Liver Diseases. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.W.; Lo, Y.M.; Chang, W.C.; Lin, C.Y.; Chen, J.A.; Wu, J.S.; Huang, W.C.; Shen, S.C. Alleviative effect of Ruellia tuberosa L. on NAFLD and hepatic lipid accumulation via modulating hepatic de novo lipogenesis in high-fat diet plus streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 5710–5716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schafer, K.A.; Eighmy, J.; Fikes, J.D.; Halpern, W.G.; Hukkanen, R.R.; Long, G.G.; Meseck, E.K.; Patrick, D.J.; Thibodeau, M.S.; Wood, C.E.; et al. Use of Severity Grades to Characterize Histopathologic Changes. Toxicol. Pathol. 2018, 46, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiner, D.E.; Brunt, E.M.; Van Natta, M.; Behling, C.; Contos, M.J.; Cummings, O.W.; Ferrell, L.D.; Liu, Y.C.; Torbenson, M.S.; Unalp-Arida, A.; et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005, 41, 1313–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alegría-Arcos, M.; Barbosa, T.; Sepúlveda, F.; Combariza, G.; González, J.; Gil, C.; Martínez, A.; Ramírez, D. Network pharmacology reveals multitarget mechanism of action of drugs to be repurposed for COVID-19. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 952192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yin, Q.; Xie, Q.; Jiang, C.; Zhou, L.; Liu, J.; Li, B.; Jiang, S. 2′-Fucosyllactose Promotes the Production of Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Improves Immune Function in Human-Microbiota-Associated Mice by Regulating Gut Microbiota. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 13615–13625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Ding, P.; Song, Y.; Zhou, J.; Chen, X.; Peng, C.; Liu, S. FDX1 downregulation activates mitophagy and the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway to promote hepatocellular carcinoma progression by inducing ROS production. Redox Biol. 2024, 75, 103302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Zhang, H.; Yu, Q.; Yin, H.; Ou, X.; Yuan, J.; Peng, L. Study on the Mechanism of Notch Pathway Mediates the Role of Lenvatinib-resistant Hepatocellular Carcinoma Based on Organoids. Curr. Mol. Med. 2025, 25, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Deng, P.; Tao, T.; Liu, H.; Wu, S.; Chen, W.; Qin, J. Modeling Human Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) with an Organoids-on-a-Chip System. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 5734–5743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broutier, L.; Andersson-Rolf, A.; Hindley, C.J.; Boj, S.F.; Clevers, H.; Koo, B.K.; Huch, M. Culture and establishment of self-renewing human and mouse adult liver and pancreas 3D organoids and their genetic manipulation. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 1724–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekkers, J.F.; Alieva, M.; Wellens, L.M.; Ariese, H.C.R.; Jamieson, P.R.; Vonk, A.M.; Amatngalim, G.D.; Hu, H.; Oost, K.C.; Snippert, H.J.G.; et al. High-resolution 3D imaging of fixed and cleared organoids. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 1756–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Khatib, M.; Costa, J.; Spinelli, D.; Capecchi, E.; Saladino, R.; Baratto, M.C.; Pogni, R. Homogentisic Acid and Gentisic Acid Biosynthesized Pyomelanin Mimics: Structural Characterization and Antioxidant Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seelam, S.D.; Agsar, D.; Halmuthur M, S.K.; Shetty, P.R.; Vemireddy, S.; Reddy, K.M.; Umesh, M.K.; Rajitha, C.H. Characterization and photoprotective potentiality of lime dwelling Pseudomonas mediated melanin as sunscreen agent against UV-B radiations. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2021, 216, 112126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalmi, P.; Bodke, P.; Wahidullah, S.; Raghukumar, S. The fungus Gliocephalotrichum simplex as a source of abundant, extracellular melanin for biotechnological applications. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 28, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, R.; Liu, X.; Yan, J.; Xiang, K.; Wu, X.; Lin, W.; Chen, G.; Zheng, M.; Fu, J. Characterization of natural melanin from Auricularia auricula and its hepatoprotective effect on acute alcohol liver injury in mice. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 1017–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manini, P.; Panzella, L.; Eidenberger, T.; Giarra, A.; Cerruti, P.; Trifuoggi, M.; Napolitano, A. Efficient Binding of Heavy Metals by Black Sesame Pigment: Toward Innovative Dietary Strategies To Prevent Bioaccumulation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 890–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Zhang, X.; Sun, S.; Zhang, L.; Shan, S.; Zhu, H. Production of natural melanin by Auricularia auricula and study on its molecular structure. Food Chem. 2016, 190, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, S.; Li, L.; Li, J.; Shaikh, F.; Yang, L.; Ye, M. Structure Characterization and Lead Detoxification Effect of Carboxymethylated Melanin Derived from Lachnum Sp. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2017, 182, 669–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavez, J.A.; Siddique, M.M.; Wang, S.T.; Ching, J.; Shayman, J.A.; Summers, S.A. Ceramides and glucosylceramides are independent antagonists of insulin signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikman, B.T. A role for sphingolipids in the pathophysiology of obesity-induced inflammation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2012, 69, 2135–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maceyka, M.; Spiegel, S. Sphingolipid metabolites in inflammatory disease. Nature 2014, 510, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magkos, F.; Su, X.; Bradley, D.; Fabbrini, E.; Conte, C.; Eagon, J.C.; Varela, J.E.; Brunt, E.M.; Patterson, B.W.; Klein, S. Intrahepatic diacylglycerol content is associated with hepatic insulin resistance in obese subjects. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 1444–1446.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotronen, A.; Seppänen-Laakso, T.; Westerbacka, J.; Kiviluoto, T.; Arola, J.; Ruskeepää, A.L.; Oresic, M.; Yki-Järvinen, H. Hepatic stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD)-1 activity and diacylglycerol but not ceramide concentrations are increased in the nonalcoholic human fatty liver. Diabetes 2009, 58, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raichur, S.; Brunner, B.; Bielohuby, M.; Hansen, G.; Pfenninger, A.; Wang, B.; Bruning, J.C.; Larsen, P.J.; Tennagels, N. The role of C16:0 ceramide in the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes: CerS6 inhibition as a novel therapeutic approach. Mol. Metab. 2019, 21, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasumov, T.; Li, L.; Li, M.; Gulshan, K.; Kirwan, J.P.; Liu, X.; Previs, S.; Willard, B.; Smith, J.D.; McCullough, A. Ceramide as a mediator of non-alcoholic Fatty liver disease and associated atherosclerosis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, M.K.; Brown, S.H.; Lim, X.Y.; Fiveash, C.E.; Osborne, B.; Bentley, N.L.; Braude, J.P.; Mitchell, T.W.; Coster, A.C.; Don, A.S.; et al. Regulation of glucose homeostasis and insulin action by ceramide acyl-chain length: A beneficial role for very long-chain sphingolipid species. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1861, 1828–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haus, J.M.; Kashyap, S.R.; Kasumov, T.; Zhang, R.; Kelly, K.R.; Defronzo, R.A.; Kirwan, J.P. Plasma ceramides are elevated in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes and correlate with the severity of insulin resistance. Diabetes 2009, 58, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Kasumov, T.; Gatmaitan, P.; Heneghan, H.M.; Kashyap, S.R.; Schauer, P.R.; Brethauer, S.A.; Kirwan, J.P. Gastric bypass surgery reduces plasma ceramide subspecies and improves insulin sensitivity in severely obese patients. Obesity 2011, 19, 2235–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, H.; Ellström, P.; Ekström, K.; Gustafsson, L.; Gustafsson, M.; Svanborg, C. Ceramide as a TLR4 agonist; a putative signalling intermediate between sphingolipid receptors for microbial ligands and TLR4. Cell. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 1239–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Huang, S.; Yi, Q.; Liu, N.; Cui, T.; Duan, S.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; et al. Hepatic Clstn3 Ameliorates Lipid Metabolism Disorders in High Fat Diet-Induced NAFLD through Activation of FXR. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 26158–26169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Qi, M.; Huang, M.; Zhou, S.; Xiong, J. Honokiol Inhibits HIF-1α-Mediated Glycolysis to Halt Breast Cancer Growth. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 796763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, M.; McClain, C.J. Intestinal HIF-1α overexpression ameliorates western dietinduced nafld and metabolic phenotypes. Gastroenterology 2023, 164, S1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Yang, X.; Zhang, G.; Xiang, Z. Therapeutic Effect and Mechanism Prediction of Fuzi-Gancao Herb Couple on Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) based on Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2024, 27, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, C.; Li, X.; Shangguan, Z.; Wei, W.; Liu, S.; Yang, S.; Liu, Y. HFD and HFD-provoked hepatic hypoxia act as reciprocal causation for NAFLD via HIF-independent signaling. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020, 20, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Dou, X.; Shan, Q.; Ning, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, T.; Cheng, T.; Shi, K.; Li, S.; Han, X.; et al. Targeting AKT to treat liver disease: Opportunities and challenges. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2025, 242, 117208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emelyanova, A.; Modestov, A.; Buzdin, A.; Poddubskaya, E. Role of ERK1/2 and p38 Protein Kinases in Tumors: Biological Insights and Clinical Implications. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 2025, 30, 31317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Niu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Yu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhu, T.; Wang, G.; Yang, L.; Yin, Y.; Li, P. Amorphous selenium nanodots alleviate non-alcoholic fatty liver disease via activating VEGF receptor 1 to further inhibit phosphorylation of JNK/p38 MAPK pathways. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 932, 175235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Dong, Z.; Liu, K. Unraveling the complexity of STAT3 in cancer: Molecular understanding and drug discovery. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Q.; Sun, X.; Zhang, M.; Chu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Han, X.; Guan, S.; Ding, C. Protective effect of baicalin against arsenic trioxide-induced acute hepatic injury in mice through JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2022, 36, 20587384211073397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, J.; Li, S.; Li, M. Apigenin attenuates atherosclerosis and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease through inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome in mice. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, K.C.; Iglesias-Carres, L.; Herring, J.A.; Wieland, K.L.; Ellsworth, P.N.; Tessem, J.S.; Ferruzzi, M.G.; Kay, C.D.; Neilson, A.P. The high-fat diet and low-dose streptozotocin type-2 diabetes model induces hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance in male but not female C57BL/6J mice. Nutr. Res. 2024, 131, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Q.; Zhu, M.; Zeng, X.; Liu, W.; Fu, F.; Li, X.; Liao, G.; Lu, Y.; Chen, Y. Comparison of Animal Models for the Study of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Lab. Investig. 2023, 103, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, B.K.; Choi, W.I.; Choi, W.; Moon, J.; Lee, W.H.; Choi, C.; Choi, I.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, J.K.; Ju, Y.S.; et al. A male mouse model for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Q.; Gu, X.; Zheng, Q.; Zhu, H. Regulatory mechanism of HIF-1α and its role in liver diseases: A narrative review. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Du, P.; Luo, K.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, W.; Zeng, C.; Ye, Q.; Xiao, Q. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha protects the liver against ischemia-reperfusion injury by regulating the A2B adenosine receptor. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 3737–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagundes, R.R.; Zaldumbide, A.; Taylor, C.T. Role of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in type 1 diabetes. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2024, 45, 798–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Jia, W.; Meng, W.; Zhang, R.; Qi, Z.; Chen, Z.; Xie, S.; Min, J.; Liu, L.; Shen, J. DAB2IP inhibits glucose uptake by modulating HIF-1α ubiquitination under hypoxia in breast cancer. Oncogenesis 2024, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kors, L.; Rampanelli, E.; Stokman, G.; Butter, L.M.; Held, N.M.; Claessen, N.; Larsen, P.W.B.; Verheij, J.; Zuurbier, C.J.; Liebisch, G.; et al. Deletion of NLRX1 increases fatty acid metabolism and prevents diet-induced hepatic steatosis and metabolic syndrome. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2018, 1864, 1883–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwo, A.; Merrill, R.A.; Wendt, L.; Pape, D.; Thakkar, H.; Maschek, J.A.; Cox, J.; Summers, S.A.; Chaurasia, B.; Pothireddy, N.; et al. Metabolite perturbations in type 1 diabetes associated with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1500242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behary, J.; Amorim, N.; Jiang, X.T.; Raposo, A.; Gong, L.; McGovern, E.; Ibrahim, R.; Chu, F.; Stephens, C.; Jebeili, H.; et al. Gut microbiota impact on the peripheral immune response in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease related hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, S.L.; Stine, J.C.; Bisanz, J.E.; Okafor, C.D.; Patterson, A.D. Bile acids and the gut microbiota: Metabolic interactions and impacts on disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.Y.; Shin, M.J.; Youn, G.S.; Yoon, S.J.; Choi, Y.R.; Kim, H.S.; Gupta, H.; Han, S.H.; Kim, B.K.; Lee, D.Y.; et al. Lactobacillus attenuates progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by lowering cholesterol and steatosis. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2021, 27, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, W.; Ling, C.W.; He, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Fu, Y.; Xu, F.; Miao, Z.; Sun, T.Y.; Lin, J.S.; Zhu, H.L.; et al. Interpretable Machine Learning Framework Reveals Robust Gut Microbiome Features Associated with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, S.; Zhu, S.; Lu, J.; Iqbal, M.; Jamil, T.; Kiani, F.A.; Dong, H.; Dai, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, F.; et al. Targeting gut microbiota in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): Pathogenesis and therapeutic insights: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 330, 147995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, H.; Zheng, Q.; Sun, X. Crucial functions of gut microbiota on gut–liver repair. hLife 2025, 3, 364–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pral, L.P.; Fachi, J.L.; Corrêa, R.O.; Colonna, M.; Vinolo, M.A.R. Hypoxia and HIF-1 as key regulators of gut microbiota and host interactions. Trends Immunol. 2021, 42, 604–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yu, Y.; Dong, L.; Gan, J.; Mao, T.; Liu, T.; Li, X.; He, L. Effects of moderate exercise on hepatic amino acid and fatty acid composition, liver transcriptome, and intestinal microbiota in channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genom. Proteom. 2021, 40, 100921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, S.; Ersoy, N.; Bagriyanik, A.; Arslan, N.; Önder, T.T.; Erdal, E. Generation of Functional Endodermal Hepatic Organoids. J. Vis. Exp. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, T.; Tanaka, M.; Goda, N. HIF-1-dependent lipin1 induction prevents excessive lipid accumulation in choline-deficient diet-induced fatty liver. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, S.; Yu, H.; Liu, X.; Gao, X. The Study on the Mechanism of Hugan Tablets in Treating Drug-Induced Liver Injury Induced by Atorvastatin. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 683707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Chen, D.; Du, Q.; Pan, T.; Tu, H.; Xu, Y.; Teng, T.; Tu, J.; Li, J.; Lin, Z.; et al. Dietary Copper Plays an Important Role in Maintaining Intestinal Barrier Integrity During Alcohol-Induced Liver Disease Through Regulation of the Intestinal HIF-1α Signaling Pathway and Oxidative Stress. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessone, F.; Razori, M.V.; Roma, M.G. Molecular pathways of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease development and progression. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 99–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drareni, K.; Ballaire, R.; Barilla, S.; Mathew, M.J.; Toubal, A.; Fan, R.; Liang, N.; Chollet, C.; Huang, Z.; Kondili, M.; et al. GPS2 Deficiency Triggers Maladaptive White Adipose Tissue Expansion in Obesity via HIF1A Activation. Cell Rep. 2018, 24, 2957–2971.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, Q.; Liang, Z.; Li, Q.; Wang, K.; Zhu, S.; Xiao, W.; Zhou, L. Black Sesame Pigment Ameliorates Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease via Modulation of the Gut–Liver Axis and HIF-1 Signaling Pathway. Antioxidants 2026, 15, 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15020177

Huang Q, Liang Z, Li Q, Wang K, Zhu S, Xiao W, Zhou L. Black Sesame Pigment Ameliorates Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease via Modulation of the Gut–Liver Axis and HIF-1 Signaling Pathway. Antioxidants. 2026; 15(2):177. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15020177

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Qian, Zhuowen Liang, Qingpeng Li, Ke Wang, Shuang Zhu, Wei Xiao, and Lin Zhou. 2026. "Black Sesame Pigment Ameliorates Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease via Modulation of the Gut–Liver Axis and HIF-1 Signaling Pathway" Antioxidants 15, no. 2: 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15020177

APA StyleHuang, Q., Liang, Z., Li, Q., Wang, K., Zhu, S., Xiao, W., & Zhou, L. (2026). Black Sesame Pigment Ameliorates Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease via Modulation of the Gut–Liver Axis and HIF-1 Signaling Pathway. Antioxidants, 15(2), 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15020177