Abstract

Thirteen (Z)-2-(substituted benzylidene)benzimidazothiazolone analogs were synthesized and evaluated for their inhibitory activity against mushroom tyrosinase. Among the compounds synthesized, compounds 1–3 showed greater inhibitory activity than kojic acid (IC50 = 18.27 ± 0.89 μM); IC50 = 3.70 ± 0.51 μM for 1; IC50 = 3.05 ± 0.95 μM for 2; and IC50 = 5.00 ± 0.38 μM for 3, and found to be competitive tyrosinase inhibitors. In silico molecular docking simulations demonstrated that compounds 1–3 could bind to the catalytic sites of tyrosinase. Compounds 1–3 inhibited melanin production and cellular tyrosinase activity in a concentration-dependent manner. Notably, compound 2 dose-dependently scavenged ROS in B16F10 cells. Furthermore, compound 2 downregulated the protein kinase A (PKA)/cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways, which led to a reduction in microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) expression, and decreased tyrosinase, tyrosinase related protein 1 (TRP1), and TRP2 expression, resulting in anti-melanogenesis activity. Hence, compound 2 may serve as an anti-melanogenic agent against hyperpigmentation diseases.

1. Introduction

Tyrosinase (polyphenol oxidase, EC 1.14.18.1), a binuclear copper-containing monooxygenase, is a critical rate-limiting melanogenic enzyme involved in melanogenesis, the process of melanin synthesis in the skin. Melanogenesis is initiated by the hydroxylation of tyrosine to l-3,4-dihydroxy-phenylalanine (DOPA), which is catalyzed by tyrosinase. Tyrosinase also catalyzes the subsequent enzymatic conversion of DOPA to dopaquinone [1,2]. Tyrosinase is the key factor involved in inducing dermatological disorders, including age spots, freckles, and melasma. Commercial tyrosinase inhibitors, such as hydroquinone, arbutin [3], kojic acid [4], ellagic acid [5], and tranexamic acid, have been used as skin-whitening agents; however, they are associated with certain side effects, including carcinogenicity, chemical instability, and poor bioavailability [6,7]. Thus, novel and efficient, anti-tyrosinase inhibitor with a favorable safety profile are necessary for anti-hyperpigmentation. There is a need to develop safe skin-whitening agents in order to overcome the limitations of established products.

α-Melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH) and 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) are the main physiological inducers of melanogenesis and accelerate tyrosinase activity through the cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) signaling pathway [8]. Furthermore, α-MSH binds to melanocortin-1 receptors (MC1R) on the surface of melanocytes to activate the protein kinase A (PKA) pathway, phosphorylate the cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) transcription factor; and induce the expression of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF), thus promoting melanogenesis [9,10]. Activated MITF induces the expression of melanogenic enzyme genes, such as tyrosinase-related protein 1 (TRP1) and dopachrome tautomerase (TRP2; DCT) [11,12,13]. The PKA/CREB and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways are important in melanogenesis; therefore, we wondered if chemicals or agents that block or activate this axis could have anti- or pro-melanogenic activity and thus serve as potential therapeutic agents for hyperpigmentation disorders [14,15,16].

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) have been linked to several disorders, including aging and age-related diseases [17,18]. Importantly, ROS levels can accelerate skin aging and increase both melanocyte proliferation and hyperpigmentation [19,20]. Among the reactive species (RS) derived from melanocytes and keratinocytes, nitric oxide (∙NO) and superoxide anion radical (O2˙−) stimulate melanin synthesis by enhancing the protein expression of tyrosinase and TRP1 [21,22,23,24]. Therefore, antioxidants, inhibitors of tyrosinase, and scavengers of ROS may suppress melanogenesis in the epidermis.

Benzimidazothiazoles, as core rings, are polycyclic isosteres whose derivatives have been reported to exert anticancer [25] and anti-inflammatory [26,27] activities. However, no study has yet described its anti-tyrosinase and hyperpigmenting effects in vitro model. Previously, we reported that (Z)-β-phenyl-α,β-unsaturated carbonyl scaffolds inhibit tyrosinase and melanogenesis both in vitro [28,29,30,31]. As our continuous efforts to find potent tyrosinase inhibitors using (Z)-β-phenyl-α,β-unsaturated carbonyl scaffolds, we integrated the benzimidazothiazolone template with other benzaldehydes to synthesize a (Z)-β-phenyl-α,β-unsaturated carbonyl scaffold.

In the present study, we evaluated the ability of (Z)-2-(substituted benzylidene)benzimidazothiazolone derivatives to inhibit mushroom tyrosinase enzyme, and performed kinetic studies and molecular docking simulations in silico; and investigated the scavenge ROS and the hyperpigmentation mechanism of a potent compound expression levels of melanogenic proteins and mRNA in B16F10 cells. As part of our continued work on potent tyrosinase inhibitors, this study aimed to evaluate the anti-melanogenic effects of benzimidazothiazolone derivatives.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Antibodies

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from WelGene (Gyeongsan-si, Daegu, Korea). Kojic acid, l-tyrosine, l-DOPA, mushroom tyrosinase (EC 1.14.18.1), α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH), and 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Antibodies against tyrosinase (sc-7833), MITF (sc-11002), phospho-CREB (p-CREB) (sc-81486), p-PKA (sc-12905), PKA (sc-365615), p-JNK (sc-6254), p-ERK (sc-7383), ERK (sc-514302), p-p38 (sc-7973), p38 (sc-535), TFIIB (sc-271736), and β-actin (sc-47778) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). CREB (#9197s) and JNK (#9252s) antibody purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Peroxidase-labeled anti-rabbit, anti-mouse, and anti-goat immunoglobulins were acquired from GeneTex (Irvine, CA, USA). Reagent-grade chemicals and solvents were purchased from commercial sources. Ultra-pure water was used throughout the experiment.

2.2. General Experimental Methods

2.2.1. Mushroom Tyrosinase Inhibitory Assay

The tyrosinase inhibitory activity assay was accomplished using mushroom tyrosinase enzyme, as previously described by Hyun et al., 2008 [32], with minor modifications. The IC50 (concentration necessary for 50% inhibition of enzyme activity) was calculated by constructing a linear regression curve presenting compound concentrations on the x-axis and percentage inhibition on the y-axis. A negative control was obtained by adding dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) instead of the compounds. Kojic acid was used as a positive control.

2.2.2. Enzyme Kinetic Analysis of Mushroom Tyrosinase

Lineweaver–Burk and Dixon plots [33,34] were used to calculate the inhibition mode and inhibition constant (Ki) against mushroom tyrosinase. Kinetic parameters for various concentrations of the l-tyrosine substrate (0.5–4 mM) and inhibitors (0.4, 2, and 10 µM for compound 1; and 2, 4, and 8 µM for compound 2; and 2.5, 5, and 10 µM for compound 3, respectively) were achieved.

2.2.3. Mushroom Tyrosinase Molecular Docking Simulations

The AutoDock4.2 software (La Jolla, CA, USA) was used to determine the structure of the enzyme-inhibitor complex and confirm precision, repeatability, and reliability of the docking results. For docking studies, the crystal structure of mushroom tyrosinase protein target was obtained from protein sequence alignment (PDB ID: 2Y9X) (http://www.rcsb.org/adb, accessed on 10 February 2021) [35]. For the docking procedure, the 2D structure was converted into a 3D structure, charges were planned, and hydrogen atoms were added using the ChemDraw program (ChemDraw Ultra 10.0, Cambridge soft) (http://www.cambridgesoft.com, accessed on 12 February 2021) [36]. The docking results were visualized and analyzed using the UCSF Chimera molecular graphics system (v1.14, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA) and AutoDockTools (v1.5.6, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA).

2.3. Biological Evaluation

2.3.1. Cell Culture and Viability Analysis

The mouse melanoma cell line B16F10 was acquired from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC®; CCL-6475™) (Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured in DMEM, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin, at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cell viability assays were performed with minor modifications, as previously reported [37]. Cell viability was evaluated using the EZ-Cytox assay kit (DaeilLab, Seoul, Korea). The compounds were dissolved in DMSO for the in vitro experiments.

2.3.2. Determination of Intracellular ROS Levels

ROS scavenging activity was determined according to the method reported by Ali et al. [38] and Lebel and Bondy [39]. Briefly, 2′,7′-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein-diacetate (DCFH-DA) (2.5 mM, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) mixed with esterase (1.5 units/mL), was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min and placed on ice in the dark until immediately prior to the study. Phosphate buffer (50 mM) at pH 7.4 was used. To determine intracellular ROS scavenging activity, B16F10 cells (1 × 104/well) were seeded in black 96-well plates. After 24 h, the cells were incubated with DCFH-DA (20 µM) and SIN-1 (200 µM) for 30 min to induce ROS generation. The fluorescence intensity of oxidized DCFH was measured using a fluorescent microplate reader at excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 and 530 nm, respectively (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland). Trolox was used as the positive control.

2.3.3. Melanin Contents in B16F10 Cells

The effect of inhibitors on the melanin content in B16F10 cells was investigated as previously described [40,41]. The amount of melanin was determined spectrophotometrically by measuring the absorbance at 492 nm using a microplate reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland). All results were standardized to the total protein concentration of the cell lysates using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.3.4. Cellular Tyrosinase Activity Assay in B16F10 Cells

B16F10 cells were seeded at a density of 3 × 103/well in 6-well plates for 24 h at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 95% air/5% CO2. Each test agent was dissolved in DMSO at a final concentration up to 20 µM and pretreated with the indicated concentration of each compound; then, α-MSH (5 µM) and IBMX (200 µM) were added to the medium for 48 h. After treatment, the cells were washed with ice-PBS and lysed by the addition of 50 mM phosphate buffer containing 1% Triton X-100 and 1% PMSF at −80 °C for 1 h. The lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 5600× g for 10 min at 4 °C; then, 80 µL of the cell lysate was added to 20 µL of l-DOPA (2 mg/mL in distilled water). The mixture was incubated for 10 min at 37 °C, and the absorbance of the reaction mixture at 492 nm was recorded using a microplate reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland). Kojic acid was used as the positive control.

2.3.5. RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

RNA from cell samples was purified using the RiboEx Total RNA solution (GeneAll Biotechnology, Seoul, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA (2 µg) treated with ribonuclease (RNase) free deoxyribonuclease (DNase) was reverse-transcribed using HyperscriptTM One-Step RT-PCR (GeneAll Biotechnology, Seoul, Korea). Real-time qPCR was performed using the SensiFASTTM SYBR® No-ROX dye (Bioline, London, UK.) and a CFX Connect System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Relative gene expression was calculated with the standard curve method using GAPDH as the internal control. Ct values were obtained with qPCR. Three independent tests were performed. The primer sequences are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sets used for real-time PCR.

2.3.6. Western Blot Analysis

Lysed samples were boiled for 10 min with gel-loading buffer (0.125 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 10% 2-mercaptoethanol and 0.2% bromophenol blue) at a volume ratio of 1:1. Total protein equivalents were separated with SDS-PAGE using 9–10% acrylamide gels and then transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) at 25 V for 10 min in a semi-dry transfer system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The membranes were immediately placed in blocking buffer (5% non-fat milk) in 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween-20. The blots were blocked at room temperature for 1 h. The membranes were incubated with appropriate specific primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight and then treated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse, anti-rabbit or anti-goat antibodies (1:5000) at 25 °C for 1 h (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA). Protein bands were visualized using the SuperSignal® West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate kit (Advansta, San Jose, CA, USA) and Davinch-ChemiTM (Davinch-K, Seoul, Korea).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The statistical significance of the differences between groups was determined with one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. An associated probability of (p value) < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results and Discussion

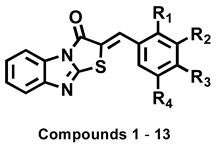

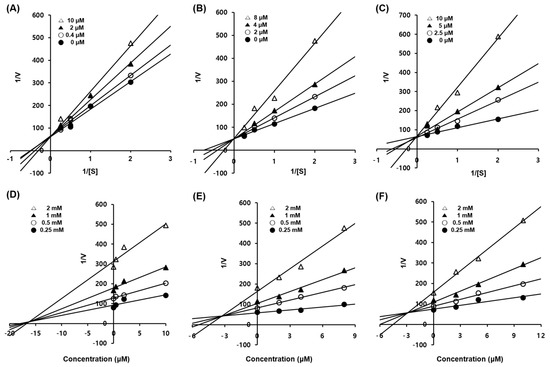

3.1. Synthesis of (Z)-2-(Substituted benzylidene)benzimidazothiazolone Derivatives 1–13

The synthetic route for the benzimidazothiazolone derivatives 1–13 is illustrated in Scheme 1. To synthesize the core template benzimidazothiazolone 15, commercially available 2-mercaptobenzimidazole was first condensed with bromoacetic acid. The reaction provided the desired compound 15 at a yield of 8%, with an intermediate 14 (59%). In the presence of acetic anhydride and pyridine, the intermediate 14 could be converted to the core template 15 rapidly and in high yield (91%) under reflux. Heating 15 and various benzaldehydes in the presence of acetic acid and sodium acetate for 15 h to 3 days produced 13 benzimidazothiazolone derivatives 1–13 as solids in yields of 35–82%. The configuration of the newly formed double bond was determined using the vicinal 1H and 13C-coupling constants (3J) in the proton-coupled 13C spectra.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis scheme of (Z)-2-(substituted benzylidene)benzimidazothiazolone derivatives 1–13.

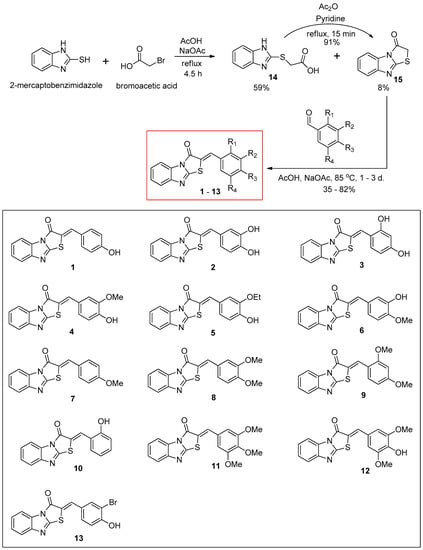

Vögeli et al. [42] reported that the configuration of trisubstituted exocyclic C, C-double bonds in a general structure A (Figure 1) differentiated the C, H-spin coupling constants over three bonds. The 3J of C(1) of compounds in which the oxygen of carbonyl and the 3-hydrogen were on the same side was 3.6 to 6.4 Hz, whereas that of the compounds in which the oxygen of carbonyl and 3-hydrogen were on the same side was roughly twice as large (generally >10 Hz). The 3J of C(1) of compound 11 was 5.3 Hz, confirming that 11 is a (Z)-isomer. Structures of the 13 final compounds were confirmed with 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy and mass spectroscopy.

Figure 1.

General structure of derivatives with trisubstituted exocyclic C, C-double bond, and the proton-coupled 13C spectrum of compound 11.

3.2. Inhibitory Activities of (Z)-2-(Substituted Benzylidene)benzimidazothiazolone Derivatives 1–13 against Mushroom Tyrosinase

To choose potent derivatives for cell-based in vitro of anti-tyrosinase and melanogenic-inhibitory activity, we synthesized 13 (Z)-2-(substituted benzylidene)benzimidazothiazolone derivatives 1–13, which were determined using mushroom tyrosinase and kojic acid (as a potent tyrosinase inhibitor) [43,44]. The inhibitory potential of compounds 1–13 against tyrosinase was assessed using l-tyrosine as the substrate, and the results were described as the IC50 values determined with linear regression analysis (Table 2). Of the 13 synthesized compounds, three exhibited potent tyrosinase inhibitor; 1 (IC50 = 3.70 µM) with a 4-hydroxy substituent; 2 (IC50 = 3.05 µM) with a 3,4-dihydroxy substituent; and 3 (IC50 = 5.00 µM) with a 2,4-dihydroxy substituent. Specifically, the inhibitory potencies of compounds 1, 2, and 3 were 4.9-, 6.0-, and 3.7-fold greater, respectively, than those of kojic acid (IC50 = 18.27 µM). Compounds 4, 5, 8, 10, 11, and 13 showed moderate inhibitory activities, with IC50 values of 42.06 µM, 21.03 µM, 41.40 µM, 27.96 µM, 34.10 µM, and 34.60 µM, respectively. Compounds 6, 7, 9, and 12 were inactive at the tested concentrations.

Table 2.

Mushroom tyrosinase inhibitory activity of (Z)-2-(substituted benzylidene) benzimidazothiazolone derivatives 1–13.

Insertion of an additional hydroxyl group into the β-phenyl ring of compound 1 with a 4-hydroxyphenyl ring increased tyrosinase inhibitory activity (compounds 1 vs. 2 and 3). Furthermore, the introduction of methoxyl, ethoxyl, or bromo groups at the 3-position of the β-phenyl ring of compound 1 with a 4-hydroxyphenyl ring abated tyrosinase inhibitory activity (compounds 1 vs. 4 and 5 and 13). Compounds 7, 8, 9, and 11, without a hydroxyl group on the β-phenyl ring showed weak or no inhibition. The 3-methoxy-4-hydroxy group of the β-phenyl ring increased tyrosinase inhibitory activity compared to the 3-hydroxy-4-methoxy group of the β-phenyl ring (compounds 4 vs. 6). Unlike the hydroxyl group, 2,4-dimethoxyphenyl groups act as hydrogen bond acceptors and are very weak or inactive. The present results are in close agreement with those of a previous reported [45].

Based on the results of our previous studies, 3,4-dihydroxyphenyl compound exhibit potent inhibitory activity against mushroom tyrosinase and cell-based cellular tyrosinase assays [46]. As expected, compound 2, with a 3,4-dihydroxyphenyl substituent (catechol moiety), exerted excellent tyrosinase inhibition, and compounds with 4-hydroxyphenyl (1) and 2,4-dihydroxyphenyl (3, resorcinol moiety) substituents also exerted potent tyrosinase inhibition. These results indicate that the 4-substitueted resorcinol moiety importantly confers tyrosinase inhibiting activity.

The position and number of hydroxyl substituents on the phenyl ring significantly influenced the inhibitory activity against tyrosinase. However, the details of certain chemical structures attached to the one or two hydroxyphenyl moieties for tyrosinase activity remain unknown; this will be the focus of future research.

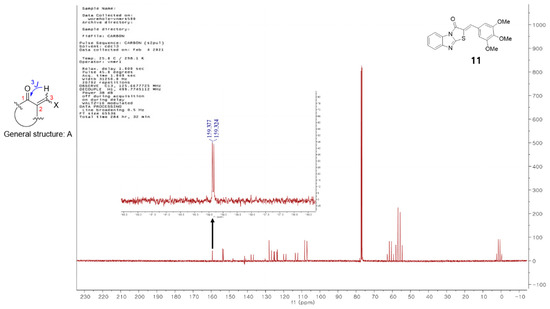

3.3. Enzyme Kinetic Studies of Compounds 1–3

To elucidate the type of enzymatic inhibition, a kinetic analysis was accomplished at several concentrations of the l-tyrosine substrate and inhibitors (1–3), according to the Lineweaver–Burk and Dixon plot methods (Table 3 and Figure 2). Kojic acid, a competitive tyrosinase inhibitor, was used as the standard [44]. Using the Lineweaver–Burk plot method, the lines representing inhibitors 1–3 intersected at the same point on the y-axis, demonstrating that Km increased with increasing concentrations of inhibitors 1–3, while 1/Vmax did not change [33]. Compounds 1–3 showed competitive inhibition. These data suggest that compounds 1–3 are effective inhibitors that bind to the active site of the enzyme [7]. Furthermore, the Dixon plot is a graphical method [plot of 1/enzyme velocity (1/V) against inhibitor concentration (I)] used to determine the type of enzymatic inhibition and the dissociation or inhibition constant (Kic) for the enzyme-inhibitor complex [33].

Table 3.

Kinetic studies of compounds 1–3 against mushroom tyrosinase.

Figure 2.

Enzymatic kinetics study of compounds 1–3 against tyrosinase. Lineweaver–Burk plots for the inhibition of mushroom tyrosinase of compounds 1 (A), 2 (B), and 3 (C). Dixon plots for tyrosinase inhibition of compounds 1 (D), 2 (E), and 3 (F) using l-tyrosine as the substrate. Data are presented as the mean values of 1/V, defined as the inverse of increased absorbance at 492 nm, as determined at several different l-tyrosine concentrations (0.5, 1, 2 and 4 mM).

The Kic (≈Ki) values for compounds 1–3 were 16.55, 3.21, and 3.01 µM, respectively, against mushroom tyrosinase (Table 3 and Figure 2). As the Kic value represents the concentration required to combine the inhibitor with an enzyme, compounds with lower Kic values were generally more effective tyrosinase inhibitors; this is an important requisite for the development of preventive and therapeutic agents.

3.4. Docking Simulation and of Ligands against Tyrosinase

Based on the in vitro results, compound 1–3—docking complexes were evaluated to understand their binding conformation within the active site of the tyrosinase. To predict the binding site of the potent compounds 1–3, molecular docking simulations were performed using the open-source programs for AutoDock4.2 [36] and AutoDock Vina [47] along with AutoDockTools, a graphical user interface compliment to the AutoDock software suite. AutoDock 4.0 uses a semi-empirical free energy force field to predict the binding free energies of protein–ligand complexes of a known structure and the binding energy for both bound and unbound states [36]. AutoDock vina was developed as a successor to AutoDock 4.2 and provides more rapid and accurate results with less direct investment required by the end user [48].

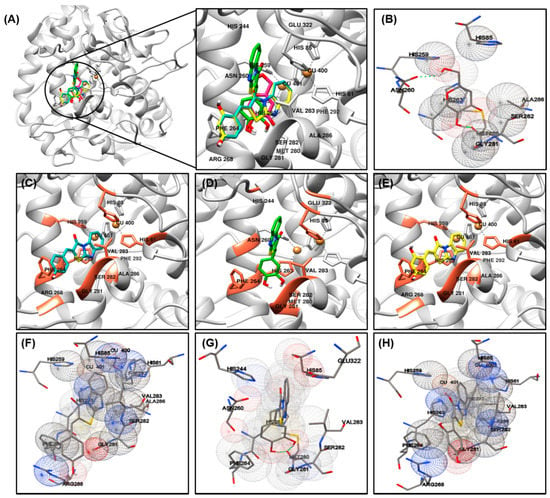

The most important factor involved in tyrosinase inhibition are coordinated with Cu ions, which played an important role in the activity. The binding energy, number of interaction residues of the compounds, and the reference compound kojic acid (competitive inhibitor) (Figure 3B) [49,50] are summarized in Table 4 and Figure 3A. The most potent compound 2 was stabilized by HIS85-, HIS244-, ASN260-, HIS263-, PHE264-, MET280-, GLY281-, SER282-, VAL283-, and GLU322-interacting (hydrogen/hydrophobic) residues (Figure 3D,G). Similarly, compound 1- or compound 3-tyrosinase complexes interacted with HIS61, HIS85, HIS259, HIS263, PHE264, ARG268, GLY281, SER282, VAL283, ALA286, and PHE292 residues, as shown in Figure 3C,F for compound 1; and Figure 3E,H for compound 3. The residues of active site of tyrosinase are HIS61, HIS85, HIS94, His259, HIS263, VAL283, and HIS296, detailed results for searching active site of tyrosinase have been previously reported [51], which also partially observed in our compounds 1–3. The binding energies of –6.73/–6.3, –6.92/–6.5, –6.35/–6.4 kcal/mol were consumed by compounds 1–3, as determined using the AutoDock 4.2 and AutoDock Vina programs. The binding scores of kojic acid were –4.21/–5.6 kcal/mol, indicating that compounds 1–3 may be bind to tyrosinase with stronger affinity than kojic acid. The basic skeleton of the synthesized compounds was similar; therefore, no significant difference in energy value was observed between the docking results. Data from the literature have also confirmed the importance of HIS259 and HIS263 residues in bonding with other tyrosinase inhibitors, supporting our docking results [51,52,53].

Figure 3.

Molecular docking simulations of tyrosinase inhibition by the reference compound and compounds 1 ((C), blue stick), 2 ((D), green stick), and 3 ((E), yellow stick) in the active site of Agaricus bisporus mushroom tyrosinase (PBD ID: 2Y9X) (A). The binding residues of kojic acid (B) and compounds 1 (F), 2 (G), and 3 (H) with tyrosinase were analyzed using the AutoDockTools software. Oxygen and nitrogen atoms are displayed in red and blue, respectively. Copper ions are shown in orange.

Table 4.

Docking energy and binding sites of compounds 1–3 against mushroom tyrosinase (PDB ID: 2Y9X), as performed using the AutoDock 4.2 and AutoDock Vina programs.

3.5. Cell Viability of Compounds 1–3

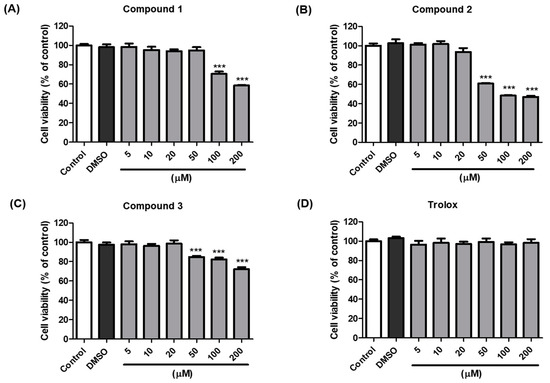

The anti-melanogenic activity of compounds 1–3, which were the most effective in B16F10 cells, was tested in a cell-based in vitro model. The EZ-Cytox assay was used to estimate cell viability. Cells were treated with various concentrations (5–200 µM) of compounds 1–3 and trolox to examine whether these compounds exhibited cytotoxic effects on melanocytes. The results indicated that compounds 1–3 and trolox did not significantly affect cell viability at concentrations up to 20 µM compared with the vehicle control cells for 48 h (Figure 4). Consequently, 20 µM sample concentrations of compounds 1–3 and trolox were used for further experiments.

Figure 4.

Effects of compounds 1–3 and trolox on the viability of B16F10 cells. Cells were incubated with different concentrations (5–200 µM) of compound 1 (A), 2 (B), 3 (C), and trolox (D) for 48 h, and cell viability was determined using EZ-Cytox assay. *** p < 0.001 vs. DMSO-treated.

3.6. ROS Scavenging Activity

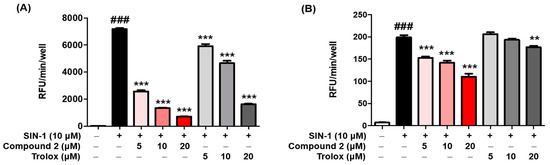

ROS may regulate melanogenesis in melanoma cells [20,54,55]. The principle of the intracellular ROS assay is that DCF-DA spreads through the cell membrane and is enzymatically hydrolyzed to DCF by esterase; DCFH then responses with ROS to yield DCF [56]. The ROS scavenging activity of compounds 1–3 was investigated in vitro by using fluorescence probes, (DCF-DA) for ROS. SIN-1 is used as an NO donor [57,58]. As demonstrated in Figure 5A, compound 2 exerted potent scavenging activity against ROS, with an IC50 value of 2.36 ± 0.48 µM, comparable with that of the reference control, trolox, which had an IC50 value of 13.25 ± 0.73 µM. However, compounds 1 and 3 did not present any activity at the tested concentrations at ≥50 µM. Furthermore, as shown in Figure 5B, treatment with SIN-1 significantly increased ROS generation compared to that in untreated B16F10 cells. Pretreatment with compound 2 reduced SIN-1-induced ROS generation in a dose-dependent manner. These results indicated that compound 2 attenuated the SIN-1-induced increase in ROS activity and intracellular ROS levels. Structure comparison of the benzimidaxothiazolone skeleton and ROS scavenging activities reveals that a ortho-dihydroxy groups of the benzylidene plays a crucial role in the observed scavenging activity. The importance of catechol moiety (3,4-dihydroxy group) for ROS scavenging activity was reported in previous studies in the literature [59,60].

Figure 5.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging activity of compound 2. The inhibitory effect of compound 2 on ROS production was evaluated. A DCFDA assay was performed to determine ROS levels. The ROS scavenger trolox was used as the positive control. The scavenging activity of compound 2 on oxidative stress induced by 10 µM SIN-1 was estimated in cell-free in vitro (A). B16F10 cells were pre-treated with compound 2 and trolox for 3 h and further treated with 10 µM SIN-1 (B). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. ### p < 0.001 vs. control. ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001 vs. SIN-1-treated or SIN-1-treated cells, respectively.

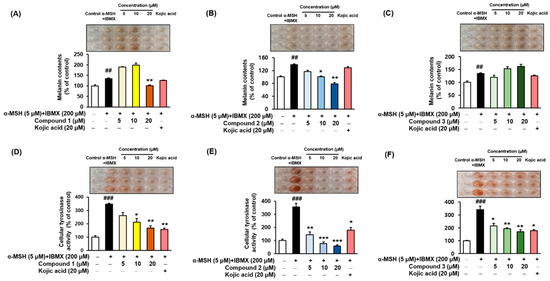

3.7. Melanin Contents and Cellular Tyrosinase Assay

α-MSH and IBMX increase the levels of intracellular cAMP, which induces melanogenesis [9,61,62]. Melanin contents were measured after pretreating the B16F10 cells with different concentrations (5, 10, and 20 µM) of the compounds 1–3 for 3 h, followed by 48 h of α-MSH and IBMX treatment. The melanin contents increased to 134.78 ± 2.95%, 137.96 ± 3.02%, and 134.78 ± 2.95% (Figure 6A–C, respectively) following treatment with α-MSH and IBMX. As shown in Figure 6B, compound 2 led to a dose-dependent decrease in the intracellular tyrosinase activity to 116.75 ± 3.52%, 100.52 ± 2.08%, and 78.80 ± 3.66%. Kojic acid at 20 µM reduced the content to 128.53 ± 2.95%. In parallel to the enzyme assay, compound 1 reduced the melanin content at 20 µM (Figure 6A), and compound 3 increased the melanin contents in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6C). To determine the inhibitory potency of compounds 1–3 in the cellular model system, the inhibitory effect on the tyrosinase activity of B16F10 cells treated with 5 µM α-MSH and 200 µM IBMX were examined. The level of intracellular tyrosinase after α-MSH and IBMX treatment was 347.03 ± 7.97%, 356.28 ± 27.70%, and 341.30 ± 26.76% (Figure 6D–F, respectively). However, cellular tyrosinase activity decreased in a concentration-dependent manner upon exposure to compounds 1–3. In both melanin contents and cellular tyrosinase inhibitory assay, compound 2 exhibited potent inhibitory activities, indicating that the presence of 3,4-dihydroxy (catechol moiety) substituent of benzimidaxothiazolone derivatives influence inhibitory activity. These results suggest that compound 2 is a promising candidate therapeutic anti-melanogenesis agent among benzimidazothiazolone derivatives.

Figure 6.

Effects of compounds 1–3 on the cellular melanin contents (A–C) and tyrosinase inhibitory activities (D–F) of α-MSH and IBMX-induced B16F10 cells, respectively. Cells were pre-incubated for 24 h and then stimulated with α-MSH (5 µM) and IBMX (200 µM) in the presence of compounds 1–3 (5, 10, and 20 µM) or kojic acid (20 µM) for 48 h. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. ## p < 0.01 and ### p < 0.001 vs. control. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001 vs. α-MSH and IBMX-treated cells.

3.8. Effects of Compound 2 on Melanogenesis-Related Signaling

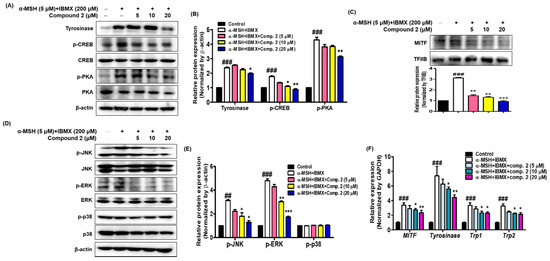

It is important to determine whether the inhibition of melanin synthesis by compound 2 is related to melanogenesis signaling and gene expression. To investigate whether compound 2 could affect the melanogenic signaling of tyrosinase, the expression of tyrosinase, phosphorylated CREB and PKA was determined with Western blot analysis using cytosolic factions from the cell lysates of α-MSH- and IBMX-induced B16F10 cells. As shown in Figure 7A,B, treatment with α-MSH and IBMX significantly upregulated these proteins; however, compound 2 decreased their expression on these proteins in a dose-dependent manner. MITF, a leucine zipper transcription factor, activates the expression of multiple genes encoding enzymes involved in the conversion of tyrosine into melanin, resulting in increased levels of these melanin-producing proteins [63,64]. Expression of MITF in α-MSH- and IBMX-induced B16F10 cells was upregulated, while compound 2 significantly suppressed MITF levels in the nuclear faction from total cell lysate (Figure 7C). The skin is site of oxidative stress due to exposure to daylight and environmental oxidizing pollutants. It is known that ROS stimulates α-MSH- and IBMX-induced production in melanoma cells leading to melanogenesis by upregulating MITF, a transcription factor that induces tyrosinase gene expression [65,66]. Since oxidative stress has been shown to activate MITF through MAPK, we investigated whether compound 2 controls MAPK signaling [67,68]. The results shown in Figure 7D,E revealed that compound 2 decreased the levels of phosphorylated JNK and ERK in a concentration-dependent manner. However, the levels of phosphorylated p38 were not affected by treatment with compound 2. In our study, both p-JNK and p-ERK were decreased by compound 2. Thus, our results suggest that compound 2, which suppresses the phosphorylated PKA and MAPK signaling pathways and MITF-mediated melanogenic enzyme expression, has potential as an anti-melanogenic agent.

Figure 7.

Effects of compound 2 on melanogenic proteins and mRNA levels in α-MSH- and IBMX-induced B16F10 cells. Cells were pre-incubated for 24 h and then stimulated with α-MSH (5 µM) and IBMX (200 µM) in the presence of compound 2 (5, 10, and 20 µM). The expression levels of tyrosinase, p-CREB, p-PKA, p-JNK, p-ERK, p-p38, and β-actin were determined with Western blotting in the cytosolic fraction. β-actin was used as the loading control (A,B,D,E). The expression levels of MITF and TFIIB were determined with Western blotting in the nuclear fraction. TFIIB was used as the loading control (C). Relative mRNA levels of the melanogenic genes MITF, Tyrosinase, Trp1, and Trp2 in the cells were quantified using real-time qPCR and normalized to the GAPDH mRNA level (F). The primer sets are shown in Table 1. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. ## p < 0.01 and ### p < 0.001 vs. control. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001 vs. α-MSH and IBMX-treated cells.

The effects of compound 2 on the expression of mRNA melanogenic factors were evaluated in α-MSH- and IBMX-induced B16F10 cells. Total mRNAs were extracted from cells treated with α-MSH and IBMX in the absence or presence of compound 2. Tyrosinase, TRP1 and TRP2 are key enzymes involved in melanin biosynthesis [64]. During melanin synthesis, tyrosine undergoes tyrosinase-dependent conversion, which is catalyzed by dapaquinone and subsequently by dopachrome. TRP2 converts dopachrome to 5,6-dihydroxyindole-2-carboxylic acid (DHICA), whereas TRP1 oxidizes DHICA to a carboxylated indole-quinone, which is eventually converted into melanin [12,68,69]. The mRNA levels of tyrosinase, TRP1, TRP2, and MITF were quantified with real-time qPCR (Figure 7F). Compound 2 significantly inhibited the expression of the MITF and downstream enzymes, such as tyrosinase, TRP1, and TRP2. These results indicate that compound 2 might be an effective hypopigmenting agent with implications in various dermatologic hyperpigmentation disorders, such as freckles and melasma, and has useful effects in whitening cosmetic agents.

4. Conclusions

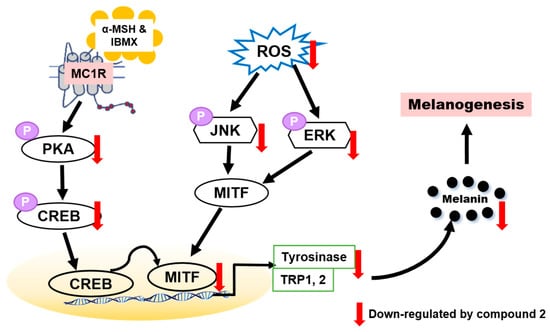

To determine whether benzimidazothiazolone with a (Z)-β-phenyl-α,β-unsaturated carbonyl scaffold plays an important role in tyrosinase inhibition, 13 derivatives were synthesized. The mushroom tyrosinase inhibitory assay revealed that three benzimidazothiazolone derivatives (compounds 1–3) with 4-, 3,4-, and 2,4-dihydroxyls on the phenyl ring of the benzimidazothiazolone scaffold, respectively, inhibited tyrosinase significantly more than the positive control (kojic acid). Enzymatic kinetic studies indicated that compounds 1–3 were competitive inhibitors. Docking simulation of compounds 1–3 predicted that they bind more strongly to the active site of tyrosinase than kojic acid. In vitro experiments showed that compounds 1–3 inhibited cellular tyrosinase inhibitory activity in a dose-dependent manner. Compound 2 scavenged ROS and inhibited melanin biosynthesis downregulating the PKA/CREB and MAPK signaling pathways, leading to suppression of MITF expression and tyrosinase (Figure 8). This is the first report of benzimidazothiazolone with a (Z)-β-phenyl-α,β-unsaturated carbonyl scaffold for anti-tyrosinase and anti-melanogenesis effects to the best our knowledge.

Figure 8.

Proposed mechanism of action of compound 2 against melanogenesis.

In the present study, it was found that compound 2 suppressed intracellular ROS level in a dose-dependent manner. Compound 2 appears to be a potential whitening agent that might protect melanoma cells from oxidative injury. Hence, compound 2 has potential for use as a novel dermatological anti-melanogenesis agent and an effective skin-whitening agent. Although many synthetic inhibitors exhibited remarkable tyrosinase inhibitory activity, only a few of them showed melanogenesis inhibition activity in cell-based or skin models. Therefore, further studies may be required to assess the potential for developing safe products of skin-whitening agents by in vivo studies [70], such as zebra fish, and may have practical applications for humans.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/antiox10071078/s1. The synthetic methods and 1H and 13C NMR data for studied compounds are included.

Author Contributions

Study design and data acquisition: H.J.J. and D.C.C.; Synthesis compounds: H.C., I.C., I.Y.R. and H.R.M.; Data analysis: H.J.J., S.G.N. and D.C.C.; Writing (original draft preparation): H.J.J.; Writing (review and editing): H.R.M. and H.Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT-2018R1A2A3075425). In addition, this research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2021R1I1A1A01052284).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article and Supplementary Material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

References

- Decker, H.; Tuczek, F. Tyrosinase/catecholoxidase activity of hemocyanins: Structural basis and molecular mechanism. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000, 25, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.J.; Choi, B.R.; Lee, E.K.; Kim, S.H.; Yi, H.Y.; Park, H.R.; Song, C.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Ku, S.K. Inhibitory effect of dried pomegranate concentration powder on melanogenesis in B16F10 melanoma cells; involvement of p38 and PKA signaling pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 24219–24242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nakajima, M.; Shinoda, I.; Fukuwatary, Y.; Hayahawa, H. Arbutin increases the pigmentation of cultured human melanocytes through mechanisms other than the induction of tyrosinase activity. Pigment Cell Res. 1998, 11, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takizawa, T.; Imai, T.; Onose, J.-I.; Ueda, M.; Tamura, T.; Mitsumori, K.; Izumi, K.; Hirose, M. Enhancement of hepatocarcinogenesis by kojic acid in rat two-stage models after initiation with N-bis(2-hydroxypropyl)nitrosamine or N-diethylnitrosamine. Toxicol. Sci. 2004, 81, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arulmozhi, V.; Pandian, K.; Mirunalini, S. Ellagic acid encapsulated chitosan nanoparticles for drug delivery system in human oral cancer cell line (KB). Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2013, 110, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.S. An updated review of tyrosinase inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 2440–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pillaiyar, T.; Manickam, M.; Namasivayam, V. Skin whitening agents: Medicinal chemistry perspective of tyrosinase inhibitors. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2017, 32, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, H.J.; Park, S.K.; Kang, J.Y.; Kim, J.M.; Yoo, S.K.; Heo, H.J. Anti-melanogenic effect of ethanolic extract of Sorghum bicolor on IBMX-induced melanogenesis in B16/F10 melanoma cells. Nutrients 2020, 12, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rzepka, Z.; Buszman, E.; Beberok, A.; Wrześniok, D. From tyrosine to melanin: Signaling pathways and factors regulating melanogenesis. Postepy Hig. Med. Dosw. 2016, 70, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Jin, M.L.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, Y.; Lee, S.J. Aromatic-turmerone inhibits α-MSH and IBMX-induced melanogenesis by inactivating CREB and MITF signaling pathways. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2011, 303, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Cervantes, C.; Solano, F.; Kobayashi, T.; Urabe, K.; Hearing, V.J.; Lozano, J.A.; García-Borrón, J.C. A new enzymatic function in the melanogenic pathway. The 5,6-dihydroxyindole-2-carboxylic acid oxidase activity of tyrosinase-related protein-1 (TRP1). J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 17993–18000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachibana, M. MITF: A stream flowing for pigment cells. Pigment Cell Res. 2000, 13, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Mello, S.A.; Finlay, G.J.; Baguley, B.C.; Askarian-Amiri, M.E. Signaling pathways in melanogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 7, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kang, H.Y.; Suzuki, I.; Lee, D.J.; Ha, J.; Reiniche, P.; Aubert, J.; Deret, S.; Zugaj, D.; Voegel, J.J.; Ortonne, J.P. Transcriptional profiling shows altered expression of wnt pathway- and lipid metabolism-related genes as well as melanogenesis-related genes in melasma. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2011, 131, 1692–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bang, S.; Won, K.H.; Moon, H.R.; Yoo, H.; Hong, A.; Song, Y.; Chang, S.E. Novel regulation of melanogenesis by adiponectin via the AMPK/CRTC pathway. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2017, 30, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, C.Y.; Ko, S.M.; Choi, Y.P.; Kim, B.J.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, J.Y.; Song, J.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Hwang, B.Y.; et al. α-Viniferin improves facial hyperpigmentation via accelerating feedback termination of cAMP/PKA-signaled phosphorylation circuit in facultative melanogenesis. Theranostics 2018, 8, 2031–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Finkel, T.; Holbrook, N.J. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature 2000, 408, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.J.; Kim, S.M.; Kim, D.H.; Bang, E.; Kang, D.; Lee, S.; Chun, P.; Moon, H.R.; Chung, H.Y. 2,4-Dihydroxyphenyl-benzo[d]thiazole (MHY553), a synthetic PPARα agonist, decreases age-associated inflammatory responses through PPARα activation and RS scavenging in the skin. Exp. Gerontol. 2021, 143, 111153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masaki, H. Role of antioxidants in the skin: Anti-aging effects. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2010, 58, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.S.; Peshavariya, H.; Higuchi, M.; Brewer, A.C.; Chang, C.W.T.; Chan, E.C.; Dusting, G.J. Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor modulates expression of NADPH oxidase type 4: A negative regulator of melanogenesis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 52, 1835–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roméro-Graillet, C.; Aberdam, E.; Clément, M.; Ortonne, J.P.; Ballotti, R. Nitric oxide produced by ultraviolet-irradiated keratinocytes stimulates melanogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 1997, 99, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sasaki, M.; Horikoshi, T.; Uchiwa, H.; Miyachi, Y. Up-regulation of tyrosinase gene by nitric oxide in human melanocytes. Pigment Cell Res. 2000, 13, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Sakamoto, K. Pyruvic acid/ethyl pyruvate inhibits melanogenesis in B16F10 melanoma cells through PI3K/AKT, GSK3β, and ROS-ERK signaling pathways. Genes Cells 2019, 24, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miao, F.; Su, M.Y.; Jiang, S.; Luo, L.F.; Shi, Y.; Lei, T.C. Intramelanocytic acidification plays a role in the antimelanogenic and antioxidative properties of vitamin C and its derivatives. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 2084805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Noha, R.M.; Abdelhameid, M.K.; Ismail, M.M.; Mohammed, M.R.; Salwa, E. Design, synthesis and screening of benzimidazole containing compounds with methoxylated aryl radicals as cytotoxic molecules on (HCT-116) colon cancer cells. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 209, 112870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenichel, R.L.; Alburn, H.E.; Schreck, P.A.; Bloom, R.; Gregory, F.J. Immunomodulating and antimetastatic activity of 3-(p-chlorophenyl) thiazolo[3, 2-a]benzimidazole-2-acetic acid (Wy-18, 251, Nsc 310633). J. Immunopharmacol. 1980, 2, 491–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Kerdawy, M.M.; Ghaly, M.A.; Darwish, S.A.; Abdel-Aziz, H.A.; Elsheakh, A.R.; Abdelrahman, R.S.; Hassan, G.S. New benzimidazothiazole derivatives as anti-inflammatory, antitumor active agents: Synthesis, in-vitro and in-vivo screening and molecular modeling studies. Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 83, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.R.; Lee, H.J.; Choi, Y.J.; Park, Y.J.; Woo, Y.; Kim, S.J.; Park, M.H.; Lee, H.W.; Chun, P.; Chung, H.Y.; et al. Benzylidene-linked thiohydantoin derivatives as inhibitors of tyrosinase and melanogenesis: Importance of the β-phenyl-α,β-unsaturated carbonyl functionality. MedChemComm 2014, 5, 1410–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Son, S.; Yun, H.Y.; Kim, D.H.; Chun, P.; Moon, H.R. Tyrosinase inhibitors: A patent review (2011–2015). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2016, 26, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.J.; Lee, M.J.; Park, Y.J.; Noh, S.G.; Lee, A.K.; Moon, K.M.; Lee, E.K.; Bang, E.J.; Park, Y.J.; Kim, S.J.; et al. A novel synthetic compound, (Z)-5-(3-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzylidene)-2-iminothiazolidin-4-one (MHY773) inhibits mushroom tyrosinase. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2018, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.J.; Yang, J.; Lee, S.; Park, C.; Kang, D.; Akter, J.; Ullah, S.; Kim, Y.J.; Chun, P.; Moon, H.R. The tyrosinase inhibitory effects of isoxazolone derivatives with a (Z)-β-phenyl-α, β-unsaturated carbonyl scaffold. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018, 26, 3882–3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.K.; Lee, W.-H.; Jeong, D.M.; Kim, Y.; Choi, J.S. Inhibitory effects of kurarinol, kuraridinol, and trifolirhizin from Sophora flavescens on tyrosinase and melanin synthesis. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 31, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lineweaver, H.; Burk, D. The determination of enzyme dissociation constants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1934, 56, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish-Bowden, A. A simple graphical method for determining the inhibition constants of mixed, uncompetitive and non-competitive inhibitors. Biochem. J. 1974, 137, 143–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismaya, W.T.; Rozeboom, H.J.; Weijn, A.; Mes, J.J.; Fusetti, F.; Wichers, H.J.; Dijkstra, B.W. Crystal structure of Agaricus bisporus mushroom tyrosinase: Identity of the tetramer subunits and interaction with Tropolone. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 5477–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- No, J.K.; Soung, D.Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Shim, K.H.; Jun, Y.S.; Rhee, S.H.; Yokozawa, T.; Chung, H.Y. Inhibition of tyrosinase by green tea components. Life Sci. 1999, 65, PL241–PL246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.F.; LeBel, C.P.; Bondy, S.C. Reactive oxygen species formation as a biomarker of methylmercury and trimethyltin neurotoxicity. Neurotoxicology 1992, 13, 637–648. [Google Scholar]

- LeBel, C.P.; Bondy, S.C. Sensitive and rapid quantitation of oxygen reactive species formation in rat synaptosomes. Neurochem. Int. 1990, 17, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsuboi, T.; Kondoh, H.; Hiratsuka, J.; Mishima, Y. Enhanced melanogenesis induced by tyrosinase gene-transfer increases boron-uptake and killing effect of boron neutron capture therapy for amelanotic melanoma. Pigment Cell Res. 1998, 11, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.G.; Chang, W.L.; Lee, C.J.; Lee, L.T.; Shih, C.M.; Wang, C.C. Melanogenesis inhibition by gallotannins from Chinese galls in B16 mouse melanoma cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2009, 32, 1447–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vögeli, U.; von Philipsborn, W.; Nagarajan, K.; Nair, M.D. Structures of addition products of acetylenedicarboxylic acid esters with various dinucleophiles. An application of C, H-spin-coupling constants. Helv. Chim. Acta 1987, 61, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashooriha, M.; Khoshneviszadeh, M.; Khoshneviszadeh, M.; Rafiei, A.; Kardan, M.; Yazdian-Robati, R.; Emami, S. Kojic acid-natural product conjugates as mushroom tyrosinase inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 201, 112480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larik, F.A.; Saeed, A.; Channar, P.A.; Muqadar, U.; Abbas, Q.; Hassan, M.; Seo, S.Y.; Bolte, M. Design, synthesis, kinetic mechanism and molecular docking studies of novel 1-pentanoyl-3-arylthioureas as inhibitors of mushroom tyrosinase and free radical scavengers. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 141, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, I.; Park, Y.; Ryu, I.Y.; Jung, H.J.; Ullah, S.; Choi, H.; Park, C.; Kang, D.; Lee, S.; Chun, P.; et al. In silico and in vitro insights into tyrosinase inhibitors with a 2-thioxooxazoline-4-one template. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, K.W.; Jeong, H.O.; Jang, E.J.; Choi, Y.J.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, S.R.; Lee, K.J.; Lee, H.J.; Chun, P.; Byun, Y.; et al. Characterization of a small molecule inhibitor of melanogenesis that inhibits tyrosinase activity and scavenges nitric oxide (NO). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1830, 4752–4761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heitz, M.P.; Rupp, J.W. Determining mushroom tyrosinase inhibition by imidazolium ionic liquids: A spectroscopic and molecular docking study. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 107, 1971–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaini, G.; Monzani, E.; Casella, L.; Santagostini, L.; Pagliarin, R. Inhibition of the catecholase activity of biomimetic dinuclear copper complexes by kojic acid. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2000, 5, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujan, R.; Saeed, A.; Ashraf, S.; Channar, P.A.; Abbas, Q.; Rind, M.A.; Hassan, M.; Raza, H.; Seo, S.Y.; El-Seedi, H.R. Synthesis, computational studies and enzyme inhibitory kinetics of benzothiazole-linked thioureas as mushroom tyrosinase inhibitors. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.L.; Lim, G.T.; Yin, S.J.; Lee, J.; Si, Y.X.; Yang, J.M.; Park, Y.D.; Qian, G.Y. The inhibitory effect of pyrogallol on tyrosinase activity and structure: Integration study of inhibition kinetics with molecular dynamics simulation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 121, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, A.; Mahesar, P.A.; Channar, P.A.; Abbas, Q.; Larik, F.A.; Hassan, M.; Raza, H.; Seo, S.Y. Synthesis, molecular docking studies of coumarinyl-pyrazolinyl substituted thiazoles as non-competitive inhibitors of mushroom tyrosinase. Bioorg. Chem. 2017, 74, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, H.; Abbasi, M.A.; Siddiqui, S.Z.; Hassan, M.; Abbas, Q.; Hong, H.; Shah, S.A.A.; Shahid, M.; Seo, S.Y. Synthesis, molecular docking, dynamic simulations, kinetic mechanism, cytotoxicity evaluation of N-(substituted-phenyl)-4-{(4-[(E)-3-phenyl-2-propenyl]-1-piperazinyl} butanamides as tyrosinase and melanin inhibitors: In vitro, in vivo and in silico approaches. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 94, 103445. [Google Scholar]

- Pelle, E.; Mammone, T.; Maes, D.; Frenkel, K. Keratinocytes act as a source of reactive oxygen species by transferring hydrogen peroxide to melanocytes. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2005, 124, 793–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, S.; Huang, J.; Pei, S.; Ouyang, Y.; Ding, Y.; Jiang, L.; Lu, J.; Kang, L.; Huang, L.; Xiang, H.; et al. Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharide inhibits UVB-induced melanogenesis by antagonizing cAMP/PKA and ROS/MAPK signaling pathways. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 7330–7340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldefie-Chézet, F.; Walrand, S.; Moinard, C.; Tridon, A.; Chassagne, J.; Vasson, M.P. Is the neutrophil reactive oxygen species production measured by luminol and lucigenin chemiluminescence intra or extracellular? Comparison with DCFH-DA flow cytometry and cytochrome c reduction. Clin. Chim. Acta 2002, 319, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becquet, F.; Courtois, Y.; Goureau, O. Nitric oxide decreases in vitro phagocytosis of photoreceptor outer segments by bovine retinal pigmented epithelial cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 1994, 159, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feelisch, M.; Ostrowski, J.; Noack, E. On the mechanism of NO release from sydnonimines. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1989, 14, S13–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anouar, E. A Quantum chemical and statistical study of phenolic schiff bases with antioxidant activity against DPPH free radical. Antioxidants 2014, 3, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marc, G.; Atana, A.; Oniga, S.D.; Pirnau, A.; Vlase, L.; Oniga, O. New phenolic derivatives of thiazolidine-2,4-dione with antioxidant and antiradical properties: Synthesis, characterization, in vitro evaluation, and quantum studies. Molecules 2019, 24, 2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corre, S.; Primot, A.; Sviderskaya, E.; Bennett, D.C.; Vaulont, S.; Goding, C.R.; Galibert, M.D. UV-induced expression of key component of the tanning process, the POMC and MC1R genes, is dependent on the p-38-activated upstream stimulating factor-1 (USF-1). J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 51226–51233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oh, T.I.; Jung, H.J.; Lee, Y.M.; Lee, S.; Kim, G.H.; Kan, S.Y.; Kang, H.; Oh, T.; Ko, H.M.; Kwak, K.C.; et al. Zerumbone, a tropical ginger sesquiterpene of Zingiber officinale Roscoe, attenuates α-MSH-induced melanogenesis in B16F10 Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhuang, Y. Antioxidant and anti-tyrosinase activities of phenolic extracts from rape bee pollen and inhibitory melanogenesis by cAMP/MITF/TYR pathway in B16 mouse melanoma cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hirata, N.; Naruto, S.; Ohguchi, K.; Akao, Y.; Nozawa, Y.; Iinuma, M.; Matsuda, H. Mechanism of the melanogenesis stimulation activity of (−)-cubebin in murine B16 melanoma cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007, 15, 4897–4902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Cao, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Z.; Bai, R.; Hao, H.; He, X.; Fan, R.; Dong, C. Nitric oxide enhances the sensitivity of alpaca melanocytes to respond to alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone by up-regulating melanocortin-1 receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 396, 849–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horikoshi, T.; Nakahara, M.; Kaminaga, H.; Sasaki, M.; Uchiwa, H.; Miyachi, Y. Involvement of nitric oxide in UVB-induced pigmentation in guinea pig skin. Pigment Cell Res. 2000, 13, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smalley, K.; Eisen, T. The involvement of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in the α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH)-induced melanogenic and anti-proliferative effects in B16 murine melanoma cells. FEBS Lett. 2000, 476, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, H.Y.; Kosmadaki, M.; Yaar, M.; Gilchrest, B.A. Cellular mechanisms regulating human melanogenesis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009, 66, 1493–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Videira, I.F.; Moura, D.F.; Magina, S. Mechanisms regulating melanogenesis. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2013, 88, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hsu, K.D.; Chen, H.J.; Wang, C.S.; Lum, C.C.; Wu, S.P.; Lin, S.P.; Cheng, K.C. Extract of Ganoderma formosamum mycelium as a highly potent tyrosinase inhibitor. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).