Bilinguals’ Working Memory (WM) Advantage and Their Dual Language Practices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Working Memory and Language Practices

2.1. Working Memory in Bilingualism

2.2. Findings in Bilingual WM Studies

2.3. Degree of Bilingualism

2.4. Cognitive Advantages and Language Practices

2.5. The Purpose of the Study

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Questionnaire

3.3. IQ and Age

3.4. Digit Span Tasks (Auditory and Visual)

3.5. Semi-Structured Interviews

4. Analysis

5. Results

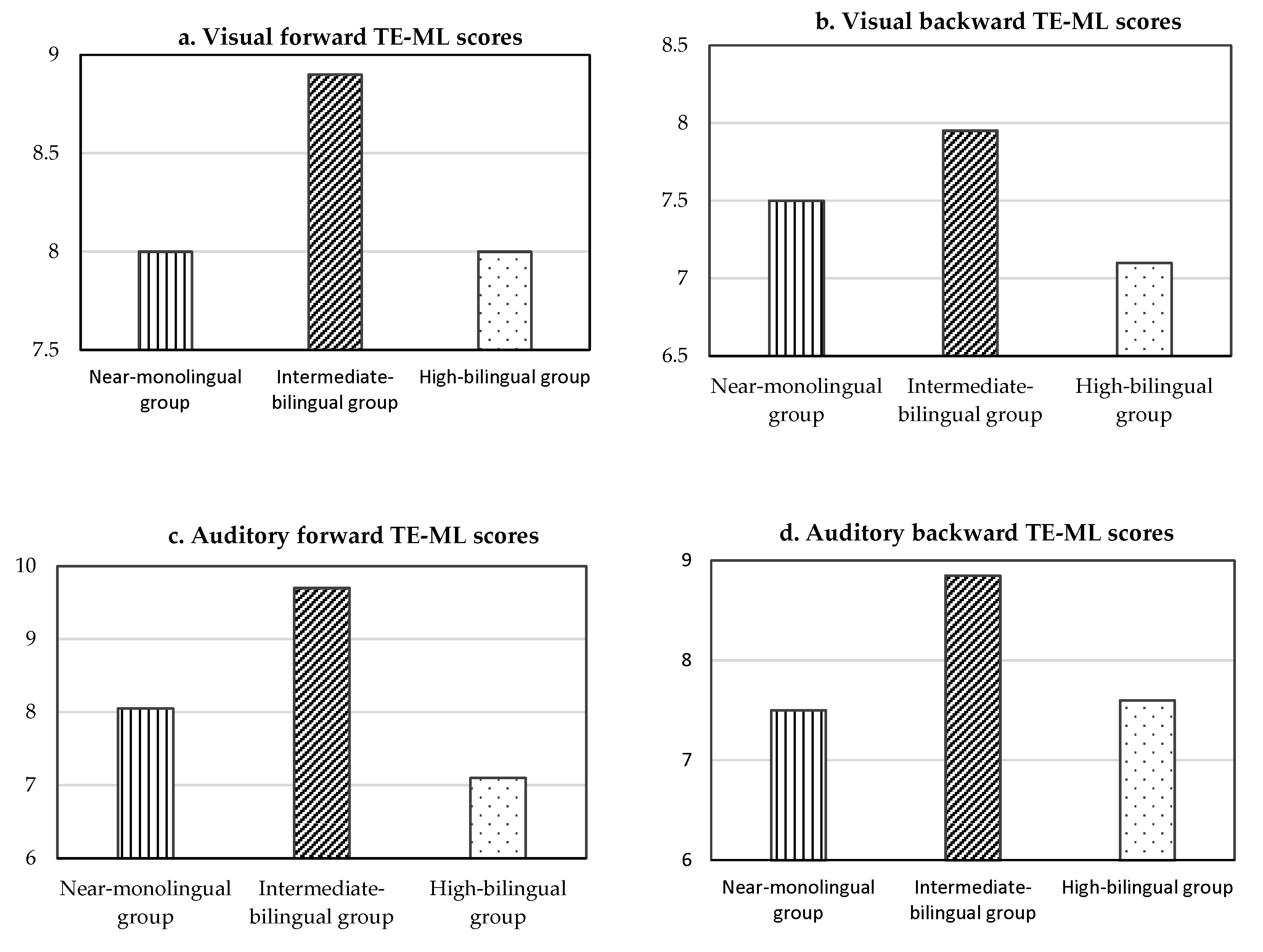

5.1. Results from Digit Span Tasks

5.2. Results from Semi-Structured Interviews

5.2.1. Strategies in Using a Second Language

- Difference between L1 and L2. All bilingual participants were aware of the language differences between Korean and English since they started learning their L2 with their fully developed L1. The language difference was one of the reasons why they felt difficulties in learning their L2. However, the difficulties led them to develop their own strategies to overcome them. For instance, participant B commented on her experiences on language differences from her early stage of learning English:English and Korean have different sentence structures: in English, verbs follow subjects, but in Korean, verbs are at the end of the sentences. It was very confusing when I started learning English. It was like I needed to remember the whole sentence and reorganize it to fully understand what I hear.She said that Korean and English have different sentence structures. This made her remember the sentence that she heard, then she re-organized it in order to understand. In her comment, “Reorganize” means that she rearranged English words in the sentence into the Korean sentence structure to interpret the meaning of the sentence. When she was asked whether she meant “reorganize” by “translating L2 into L1”, she said: “not really; I need to know where the verb is.” Her comment implied that, even though she was not translating, she put English words into the frame of her native language structure. Considering the different word order between English (Subject + Verb + Object) and Korean (Subject + Object + Verb), her re-organizing indicated that, at least in her early stage of L2 learning, she relied on her L1 system, to some degree, to understand her L2 input. Based on her comment, it can be assumed that her L2 system had not reached a level at which she was able to understand as she was hearing the L2 input, so that she needed to use her L1 system to understand. All interview participants reported this practice in their early L2 learning stage.

- Monitoring languages. Most of the bilingual groups paid extra attention to their L2 output to monitor it, even if the degree of attention and the language features they focused on varied between the participants (this is discussed in detail under the theme ‘Effort is continuous’). The language features to which they attended included pronunciation of words, usages of words, and language structures. Participant G described how he was attentive to the L2 grammar when he communicated with people in English:I think I pay attention to the language forms when I listen to English, cuz most of the time, I can tell “oh that person didn’t put 3rd person singular”, “Oh, my tense is wrong”, but I don’t do those kind of things when I hear Korean. Korean comes so naturally I do not even need to think.He was attentive to his L2 form and his attention enabled him to pinpoint his L2 errors in his speech. However, he did not intentionally focus on his L2 output. For example, he said he “thinks” he “pays” attention to the language form because he was able to notice his own errors, while he was not able to notice any errors when he used Korean; as he stated: “I do not even need to think.” G’s comment also implied that he had a tendency to check the L2 forms and his tendency became automatic and unnoticed unless he found himself producing errors. Most bilingual participants across the language groups reported that they had a tendency to monitor their language in attempts to produce proper and correct language. Participant H shared an example of his monitoring and his reason to monitor his L2:Even though I think ahead, sometimes I make mistakes, but I always think. I need to say proper words and correct sentences so people will understand me. So that is why I think, especially when I say longer sentences, I think carefully, I focus on what I need to say…I kinda remember words and sentences that I use, you know, cuz I can tell whether my English is correct or not as I speak.He said he wanted to produce “proper words” and “sentences” so that people could easily comprehend his English. H monitored his language to produce “correct” English, and this monitoring was done carefully with focus; as he said, “I focus on what I need to say.” This can be interpreted to mean that he pays extra attention to what he wants to focus on when he uses English. He also said that he “always thinks” about what he was going to say ahead of time. This implies not only that he monitors his L2 intentionally every time he uses it but also that this monitoring has become habitual for him since he does it whenever he uses his L2 to avoid making mistakes. His comment, “I can tell whether my English is correct or not as I speak,” indicates that his monitoring has become an automatic process so that he can recognize his mistakes whenever they are committed.

- Holding information. Bilingual participants across the groups frequently mentioned that they tried to remember what they heard when they conversed in English. However, there were differences between participants as to how they remembered information and why. The pattern that the intermediate bilinguals showed was mostly remembering sentences. Participant E is a representative example of bilinguals’ sentence remembering strategy:When I first started learning English, I needed to remember what I heard so I could understand, I mean, I needed to play what I heard in my mind if I didn’t understand what I heard back then. It was hard for me to understand as I heard, you know what I mean, so I could keep thinking [about] the sentence so I could get the meaning. Sometimes, when I heard a very difficult sentence, I needed to translate sentences into Korean to have full understanding, so I needed to remember what I heard.Participant E tried to remember what she had heard in order to understand the conversation correctly. She reported that when she first started learning English, she tried to hold sentences in her mind so she could replay them when she could not understand the meaning of sentences as she heard them. It seemed that this replaying activity saved some time for her to decode the meaning of the sentences. Participants often reported that they also needed to replay the input in order to translate it into their L1, especially in the early stage of L2 acquisition; as Participant E said, “I needed to translate.” Translation seems to help them understand the conversation in the early L2 learning stage, when their emerging L2 skills challenged them to understand the ongoing L2 conversation. In other words, their lack of L2 proficiency caused them to develop strategies to replay their L2 input and translate it into their L1 for managing ongoing communication.However, participants reported that translation, which appeared at an earlier L2 acquisition stage, disappeared after a few years (most participants said after three or four years) and by the time it faded they were able to understand sentences naturally as they heard the language. For instance, most intermediate bilinguals reported that they still translated L2 into L1 when they needed, while high bilinguals reported that they did not need to use their L1 to understand L2. With improved L2 proficiency, they did not need to mentally repeat sentences to process them. However, their tendency for remembering and holding information did not totally disappear; it appeared in different forms. This is discussed under the theme ‘Effort is continuous’.

5.2.2. Effort is Continuous

- Stabilized L2 system. All participants mentioned that they felt comfortable using English as their years spent in the United States increased. For example, participant F mentioned how her strategy had changed as her L2 improved: “I feel more confident in speaking in English, less translation.” She indicated that she was less likely to translate what she heard as her L2 proficiency improved. The bilinguals’ needs for translating from L2 to L1 or remembering sentences for the purpose of understanding seemed to decrease as they felt confident in their L2. The high bilinguals also indicated that their stabilized L2 helped them to use their L2 with less effort. Participant D mentioned: “I got comfortable using English; in a lot of cases, I understand English as [well as] I understand Korean.” He indicated that his L2 system had stabilized to the degree that he was able to process English as he processed Korean. Bilinguals’ developed L2 seemed to free them from using some of the L2 strategies that they built up while acquiring their L2.

- Improving L2. Even though high bilinguals reported that they no longer needed to hold what they heard in L2 in mind for translation, they tended to remember sentences from conversations for a different purpose. Participant A reported his habit of using English:When I talk to my friends, sometimes I hear expressions that I want to use but I haven’t used so I repeat the sentences in my mind and try to memorize them, because I want to use them later if I have any chances to use them.During conversations with native speakers of English, he caught expressions that he did not use in English and then he tried to remember them for future use. The interview data showed that bilinguals were attentive to L2 most of the time when they used the language. Similar to their earlier L2 stage, bilinguals employed remembering strategies continuously but the goal of this practice was not the overcoming of their lower L2 proficiency but improving their L2 skills.

- Degree of monitoring. The two bilingual groups also showed different degrees of monitoring. For example, in a group interview, the intermediate bilinguals agreed that they tended to be attentive to their L2 whenever they used it, while the high bilinguals agreed that they often did not notice their attention to the L2. Following is an interview with the high bilingual group about their remembering strategy:

- D:

- No, I don’t, if I am able to understand it, I understand it right away, if I don’t understand, I ask right away what the person tries to say, but I don’t try to remember information. When I first learned English, I mean when I tried to learn English, I did, that was how I learned English, but I do not do it any more I guess, I just ask if I missed something.

- Interviewer:

- What about you?

- B:

- My case is the same, when I started trying to learn English, I tried to remember as much as possible, but I don’t know whether I do that or not. Hmm, I do that sometimes when someone use words that I haven’t used, new expressions, yeah, then I would remember it so I can use it, but not often, I feel quite comfortable with English, (I have) been living here about eight years.

- Interviewer:

- Do you guys agree on this?

- C:

- Yeah, English is quite comfortable, sometimes, more comfortable than Korean, [I] do not need to think that much when I use English, I guess.

D reported that he had tried to remember words, expressions, and sentences as he heard them when he started to learn L2, but he “does not do it anymore.” This pattern was also observed by all the high bilingual participants in their individual interviews. They were not sure whether they consciously remembered the information anymore; as B said, “I don’t know whether I do that or not.” In addition, they focused on and remembered less of their L2 output than they used to. C pointed out that she was quite comfortable with English, so she did not need to focus on her language. However, bilinguals in this study were still attentive to what they heard; as B said: “I do that sometimes when someone use words that I haven’t used.” Her comment shows that she noticed an expression that was not familiar with. This indicates that she was still attentive to her L2 input even though she did not realize until she heard a new expression. B felt “quite comfortable with English” after living in the United States “for about eight years,” so she did not need to use strategies as intensively as she did when she was in an earlier stage of L2 learning. This suggests that she established a stabilized L2 language system during her stay in the United States, so she was able to use her L2 without using strategies she developed when she first came to the United States.

6. Conclusions and Discussion

7. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bialystok, E. Attentional control in children’s metalinguistic performance and measures of field independence. Dev. Psychol. 1992, 28, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E. Effect of bilingualism and computer video game experience on the Simon task. Can. J. Exp. Psychol. 2006, 60, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ransdell, S.; Barbier, M.; Niit, T. Metacognitions about language skill and working memory among monolingual and bilingual college students: When does multilingualism matter? Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2006, 9, 728–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorstman, E.; Swart, H.; Ceginskas, V.; Bergh, H. Language learning experience in school context and metacognitive awareness of multilingual children. Int. J. Multiling. 2009, 6, 258–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharkhurin, A.V. The effect of linguistic proficiency, age of second language acquisition, and length of exposure to a new cultural environment on bilinguals’ divergent thinking. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2008, 11, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardelli, L.A. Creativity and bilingualism. J. Creat. Behav. 1992, 26, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E.; Craik, F.I.M.; Klein, R.; Viswanathan, M. Bilingualism, aging, and cognitive control: Evidence from the Simon task. Psychol. Aging 2004, 19, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brysbaert, M. Word recognition in bilinguals: Evidence against the existence of two separate lexicons. Psychol. Belg. 1998, 38, 163–175. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, A.; Timmermans, M.; Schriefers, H. On being blinded by your other language: Effects of task demands on interlingual homograph recognition. J. Mem. Lang. 2000, 42, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, W.S. Analogical transfer of problem solutions within and between languages in Spanish-English bilinguals. J. Mem. Lang. 1999, 40, 301–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollan, T.H.; Kroll, J.F. Bilingual lexical access. In The Handbook of Cognitive Neuropsychology: What Deficits Reveal about the Human Mind; Rapp, B., Ed.; Psychology Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2001; pp. 321–345. [Google Scholar]

- Tokowicz, N.; Michael, E.B.; Kroll, J.F. The roles of study-abroad experience and working-memory capacity in the types of errors made during translation. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2004, 7, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, A.D. Working Memory, Thought, and Action; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fuster, J.M. Memory in the Cerebral Cortex: An Empirical Approach to Neural Networks in the Human and Nonhuman Primate; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Linck, J.A.; Weiss, D.J. Working memory predicts the acquisition of explicit L2 knowledge. In Implicit and Explicit Lang. Learning: Conditions, Processes, and Knowledge in SLA and Bilingualism; Sanz, C., Leow, R.P., Eds.; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Logie, R.; Baddeley, A.; Mané, A.; Donchin, E.; Sheptak, R. Working memory in the acquisition of complex cognitive skills. Acta Psychol. 1989, 71, 53–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logie, R.; Gilhooly, K.; Wynn, V. Counting on working memory in arithmetic problem solving. Mem. Cogn. 2008, 22, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.I.; Ellis, N.C. The roles of phonological short-term memory and working memory in L2 grammar and vocabulary learning. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 2012, 34, 379–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, E.B.; Gollan, T.H. Being and becoming bilingual: Individual differences and consequences for language production. In Handbook of Bilingualism: Psycholinguistic Approaches; Kroll, J.F., De Groot, A.M.B., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 389–408. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley, A.D.; Hitch, G. Working Memory. In The psychology of Learning and Motivation: Advances in Research and Theory; Bower, G.A., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974; pp. 47–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ashcraft, M.H. Fundamentals of Cognition; Addison-Wesley: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lezak, M.D. Neuropsychological Assessment; Oxford University: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam, M.M. The human frontal lobes: Transcending the default mode through contingent encoding. In Principles of Frontal Lobe Function; Stuss, D., Knight, R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 8–30. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, A. The early development of executive function. In Lifespan Cognition: Mechanisms of Change; Bialystok, E., Craik, F., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 70–95. [Google Scholar]

- Miyake, A.; Friedman, N.; Emerson, M.; Witzki, A.; Howerter, A.; Wager, T.D. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cogn. Psychol. 2000, 41, 49–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bialystok, E.; Craik, F.I.M.; Grady, C.; Chau, W.; Ishii, R.; Gunji, A.; Pantev, C. Effect of bilingualism on cognitive control in the Simon task: Evidence from MEG. NeuroImage 2005, 24, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bialystok, E.; DePape, A.M. Musical expertise, bilingualism, and executive functioning. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 2009, 35, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, A.; Hernandez, M.; Costa-Faidella, J.; Sebastian-Galles, N. On the bilingual advantage in conflict procession: Now you see it, now you don’t. Cognition 2009, 113, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmorey, K.; Luk, G.; Pyers, J.E.; Bialystok, E. The source of enhanced cognitive control in bilinguals: Evidence from bimodal bilinguals. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 19, 1201–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Rhee, M.M.; Bialystok, E. The development of two types of inhibitory control in monolingual and bilingual children. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2008, 11, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E.; Craik, F.; Luk, G. Cognitive control and lexical access in younger and older bilinguals. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2008, 34, 859–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyake, A.; Friedman, N.P. The nature and organization of individual differences in executive functions: Four general conclusions. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 21, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, J.; Calvo, A.; Bialystok, E. Working memory development in monolingual and bilingual children. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2013, 114, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blom, E.; Kuntay, A.C.; Messer, M.; Verhagen, J.; Leseman, P. The benefits of being bilingual: Working memory in bilingual Turkish-Dutch children. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2014, 128, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez-Clellen, V.F.; Calderon, J.; Weismer, S.E. Verbal working memory in bilingual children. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2004, 47, 863–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namazi, M.; Thordardottir, E. A working memory, not bilingual advantage, in controlled attention. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2010, 13, 597–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel de Abreu, P.M. Working memory in multilingual children: Is there a bilingual effect? Memory 2011, 19, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummins, J. Linguistic Interdependence and the Educational Development of Bilingual Children. Rev. Educ. Res. 1979, 49, 222–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, J. Language, Power and Pedagogy: Bilingual Children in the Crossfire; Multilingual Matters: Clevedon, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn, A.M. A Study of the Relationship Between Code Switching and the Bilingual Advantage: Evidence that Language Use Modulates Neural Indices of Language Processing and Cognitive Control. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Green, D.W.; Abutalebi, J. Language control in bilinguals: The adaptive control hypothesis. J. Cogn. Psychol. 2013, 25, 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heredia, R.R.; Altarriba, J. Bilingual Language Mixing: Why Do Bilinguals Code-Switch? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2001, 10, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers-Scotton, C.; Namazi, M.; Thordardottir, E. Duelling Languages: Grammatical Structure in Codeswitching; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Teddlie, C.; Tashakkori, A. Foundations of Mixed Methods Research: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches in the Social and Behavioral Sciences; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, V.P. How long? A synthesis of research on academic achievement in second language. TESOL Q. 1989, 23, 509–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E. Levels of bilingualism and levels of linguistic awareness. Dev. Psychol. 1988, 24, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, C.R.; Goggin, J.P. The measurement of bilingualism and its relationship to cognitive ability. Appl. Psycholinguist. 1989, 10, 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, A.E.; Li, P. Age of acquisition: Its neural and computational mechanisms. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 638–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, L.C.; Crowly, A.C. Development of cortical circuits: Lessons from ocular dominance. Nature 2002, 3, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Understanding Your TOEFL iBT® Test Scores. Site. Available online: http://www.ets.org/toefl/ibt/scores/understand (accessed on 10 July 2017).

- De Ribaupierre, A.; Lecerf, T. Relationships between working memory and intelligence from a developmental perspective: Convergent evidence from a neo-Piagetian and a psychometric approach. Eur. J. Cogn. Psychol. 2006, 18, 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salthouse, T.A.; Babcock, R.L.; Mitchell, D.R.D.; Palmon, R.; Skovronek, E. Sources of individual differences in spatial visualization ability. Intelligence 1990, 14, 187–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattell, R.B.; Cattell, A.K.S. Measuring Intelligence with the Culture Fair Tests; Hogrefe: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Deary, I.J.; Whalley, L.J.; Starr, J.M. A Lifetime of Intelligence; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, J.T.E. Measures of short-term memory; a historical review. Cortex 2007, 43, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, D.L.; Kishiyama, M.M.; Yund, E.W.; Herron, T.J.; Edwards, B.; Poliva, O.; Hink, R.F.; Reed, B. Improving digit span assessment of short-term verbal memory. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2011, 33, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, J. Focusing on the focus group. In Qualitative Research Methods in Human Geography; Hay, I., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Victoria, Australia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, M.A.; Smith, M.W. Capturing the group effect in focus groups: A special concern in analysis. Qual. Health Res. 1994, 4, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamathi, A.; Shuler, P. Focus group interview: A research technique. J. Adv. Nurs. 1990, 15, 1281–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinfurt, K.P. Multivariate analysis of variance. In Reading and Understanding Multivariate Statistics; Grimm, L.G., Yarnold, P.R., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp. 317–362. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A.P. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS for Windows: Advanced Techniques for the Beginner; Sage: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis, R.E. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, L.S.; Gamst, G.; Guarino, A.J. Applied Multivariate Research: Design and Interpretation; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebb, D.O. The effects of early experience on problem-solving at maturity. Am. Psychol. 1947, 2, 306–307. [Google Scholar]

- Hebb, D.O. The Organization of Behavior: A Neuropsychological Theory; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Fratiglioni, L.; Paillard-Borg, S.; Winblad, B. An active and socially integrated lifestyle in late life might protect against dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2004, 3, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, C.S.; Bavelier, D. Exercising your brain: A review of human brain plasticity and training-induced learning. Psychol. Aging 2008, 23, 692–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potter, G.G.; Helms, M.J.; Plassman, B.L. Associations of job demands and intelligence with cognitive performance among men in late life. Neurology 2008, 70, 1803–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prior, A.; Gollan, T.H. Good language-switchers are good task-switchers: Evidence from Spanish–English and Mandarin-English bilinguals. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2011, 17, 682–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soveri, A.; Rodriguez-Fornells, A.; Laine, M. Is there a relationship between language switching and executive functions in bilingualism? Introducing a within group Analysis Approach. Front. Psychol. 2011, 2, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macnamara, B.N.; Conway, A.R. Novel evidence in support of the bilingual advantage: Influences of task demands and experience on cognitive control and working memory. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2014, 21, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahadi, S.A.; Rothbart, M.K.; Ye, R. Children’s temperament in the US and China similarities and differences. Eur. J. Pers. 1993, 7, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hastings, P.D.; Rubin, K.H.; Chen, H.; Cen, G.; Stewart, S.L. Child-rearing attitudes and behavioral inhibition in Chinese and Canadian toddlers: A crosscultural study. Dev. Psychol. 1998, 34, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Yang, H.; Lust, B. Early childhood bilingualism leads to advances in executive attention: Dissociating culture and language. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2011, 14, 412–422. [Google Scholar]

| Section | Range of Scores | What It Means |

|---|---|---|

| Reading | 0–30 | 0–14 (low) |

| 15–21 (intermediate) | ||

| 22–30 (high) | ||

| Listening | 0–30 | 0–14 (low) |

| 15–21 (intermediate) | ||

| 22–30 (high) | ||

| Speaking | 0–4 points, converted into a 0–30 scale | 0–9 (weak) |

| 10–17 (limited) | ||

| 18–25 (fair) | ||

| 26–30 (good) | ||

| Writing | 0–5 points, converted into a 0–30 scale | 1–16 (limited) |

| 17–23 (fair) | ||

| 24–30 (good) |

| SES | Education | Gender | Daily L2 Exposure (Hour) | Year of Stay in L2 Speaking Country | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of M.C. | No. of U.M.C. | No. of U.G.S | No. of G.S | M | F | |||

| Near-Monolingual (N = 20) | 15 | 5 | 14 | 6 | 9 | 11 | 1.88 | Less than 2 months |

| Intermediate Bilinguals (N = 20) | 16 | 4 | 13 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 8.9 | 4.14 |

| High Bilinguals (N = 20) | 18 | 2 | 13 | 7 | 11 | 9 | 8.8 | 8.25 |

| Language Groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Monolingual (N = 20) | Intermediate Bilinguals (N = 20) | High Bilinguals (N = 20) | |

| Age | 24.50 (4.01) | 24.45 (4.07) | 23.50 (2.373) |

| Cattell | 59.35 (5.65) | 59.15 (5.35) | 58.90 (5.34) |

| Participants | Language Group | Age | Gender | TOEFL Score | Years in USA | Field of Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | H.B | 22 | Male | 102 | 8 | Pharmacy |

| B | H.B | 25 | Female | 97 | 7.2 | Management |

| C | H.B | 24 | Female | 98 | 6 | Business |

| D | H.B | 27 | Male | 94 | 10 | Physical therapy |

| E | I.B | 22 | Female | 70 | 4.5 | Management |

| F | I.B | 25 | Female | 86 | 4.8 | Biology |

| G | I.B | 28 | Male | 88 | 3.2 | Education |

| H | I.B | 29 | Male | 80 | 4 | Computer science |

| Theme | Categories |

|---|---|

| Strategies in using 2nd language | 1. Difference between L1 and L2 |

| 2. Monitoring languages | |

| 3. Holding information | |

| Efforts is continuous | 1. Stabilized L2 system |

| 2. Improving L2 | |

| 3. Degree of monitoring |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. VF TE-ML | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 2. VF TE-TT | 0.850 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 3. VF ML | 0.740 ** | 0.551 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 4. VF MS | 0.741 ** | 0.423 ** | 0.912 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 5. VB TE-ML | 0.535 ** | 0.399 ** | 0.574 ** | 0.544 ** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 6. VB TE-TT | 0.399 ** | 0.360 ** | 0.360 ** | 0.320 * | 0.808 ** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 7. VB ML | 0.525 ** | 0.328 * | 0.629 ** | 0.643 ** | 0.745 ** | 0.534 ** | 1 | |||||||||

| 8. VB MS | 0.502 ** | 0.341 ** | 0.574 ** | 0.610 ** | 0.732 ** | 0.510 ** | 0.900 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| 9. AF TE-ML | 0.389 ** | 0.358 ** | 0.437 ** | 0.389 ** | 0.472 ** | 0.324 * | 0.500 ** | 0.534 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 10. AF TE-TT | 0.298 * | 0.295 * | 0.329 * | 0.270 * | 0.319 * | 0.211 | 0.364 ** | 0.361 ** | 0.919 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 11. AF ML | 0.501 ** | 0.505 ** | 0.521 ** | 0.482 ** | 0.591 ** | 0.325 * | 0.530 ** | 0.605 ** | 0.694 ** | 0.539 ** | 1 | |||||

| 12. AF MS | 0.509 ** | 0.487 ** | 0.544 ** | 0.527 ** | 0.602 ** | 0.359 ** | 0.573 ** | 0.655 ** | 0.731 ** | 0.496 ** | 0.926 ** | 1 | ||||

| 13. AB TE-ML | 0.365 ** | 0.306 * | 0.385 ** | 0.382 ** | 0.503 ** | 0.361 ** | 0.527 ** | 0.595 ** | 0.701 ** | 0.574 ** | 0.551 ** | 0.623 ** | 1 | |||

| 14. AB TE-TT | 0.287 * | 0.222 | 0.239 | 0.247 | 0.459 ** | 0.339 ** | 0.479 ** | 0.558 ** | 0.557 ** | 0.455 ** | 0.381 ** | 0.450 ** | 0.896 ** | 1 | ||

| 15. AB ML | 0.447 ** | 0.379 ** | 0.534 ** | 0.516 ** | 0.604 ** | 0.416 ** | 0.544 ** | 0.604 ** | 0.668 ** | 0.532 ** | 0.724 ** | 0.758 ** | 0.715 ** | 0.515 ** | 1 | |

| 16. AB MS | 0.432 ** | 0.359 ** | 0.524 ** | 0.520 ** | 0.535 ** | 0.355 ** | 0.507 ** | 0.575 ** | 0.700 ** | 0.548 ** | 0.713 ** | 0.759 ** | 0.740 ** | 0.493 ** | 0.958 ** | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Visual forward TE-ML | 1 | 8.30 | 1.38 | |||

| 2. Visual backward TE-ML | 0.535 ** | 1 | 7.52 | 1.19 | ||

| 3. Auditory forward TE-ML | 0.389 ** | 0.472 ** | 1 | 8.68 | 1.57 | |

| 4. Auditory backward TE-ML | 0.365 ** | 0.503 ** | 0.701 ** | 1 | 7.98 | 1.69 |

| Levene’s | ANOVAs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F (2, 57) | p | F (2, 57) | p | η2 | |

| Visual forward TE-ML | 1.18 | 0.315 | 3.02 | 0.056 | 0.096 |

| Visual backward VB TE-ML | 0.34 | 0.716 | 2.72 | 0.074 | 0.087 |

| Auditory forward AF TE-ML | 0.34 | 0.711 | 4.41 | 0.017 | 0.134 |

| Auditory backward AB TE-ML | 0.98 | 0.380 | 7.95 | 0.001 | 0.218 |

| N. M. | I. B. | H. B | N. M. vs. I. B. (Cohen’s d) | N. M. vs. H.B. (Cohen’s d) | I. B. vs. H. B. (Cohen’s d) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| VF TE-ML | 8.00 | 1.52 | 8.90 | 1.73 | 8.00 | 1.08 | 0.90 * (0.62) | 0.00 | 0.90 * (0.73) |

| VB TE-ML | 7.50 | 1.28 | 7.95 | 1.10 | 7.10 | 1.07 | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.85 * (0.78) |

| AF TE-ML | 8.05 | 1.82 | 9.70 | 1.42 | 8.30 | 1.54 | 1.65 * (1.01) | 0.25 | 1.40 * (0.95) |

| AB TE-ML | 7.50 | 1.43 | 8.85 | 1.17 | 7.60 | 1.59 | 1.35 * (0.94) | 0.10 | 1.25 * (0.83) |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, E. Bilinguals’ Working Memory (WM) Advantage and Their Dual Language Practices. Brain Sci. 2017, 7, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci7070086

Yang E. Bilinguals’ Working Memory (WM) Advantage and Their Dual Language Practices. Brain Sciences. 2017; 7(7):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci7070086

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Eunju. 2017. "Bilinguals’ Working Memory (WM) Advantage and Their Dual Language Practices" Brain Sciences 7, no. 7: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci7070086

APA StyleYang, E. (2017). Bilinguals’ Working Memory (WM) Advantage and Their Dual Language Practices. Brain Sciences, 7(7), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci7070086