Efficient and Accurate Epilepsy Seizure Prediction and Detection Based on Multi-Teacher Knowledge Distillation RGF-Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

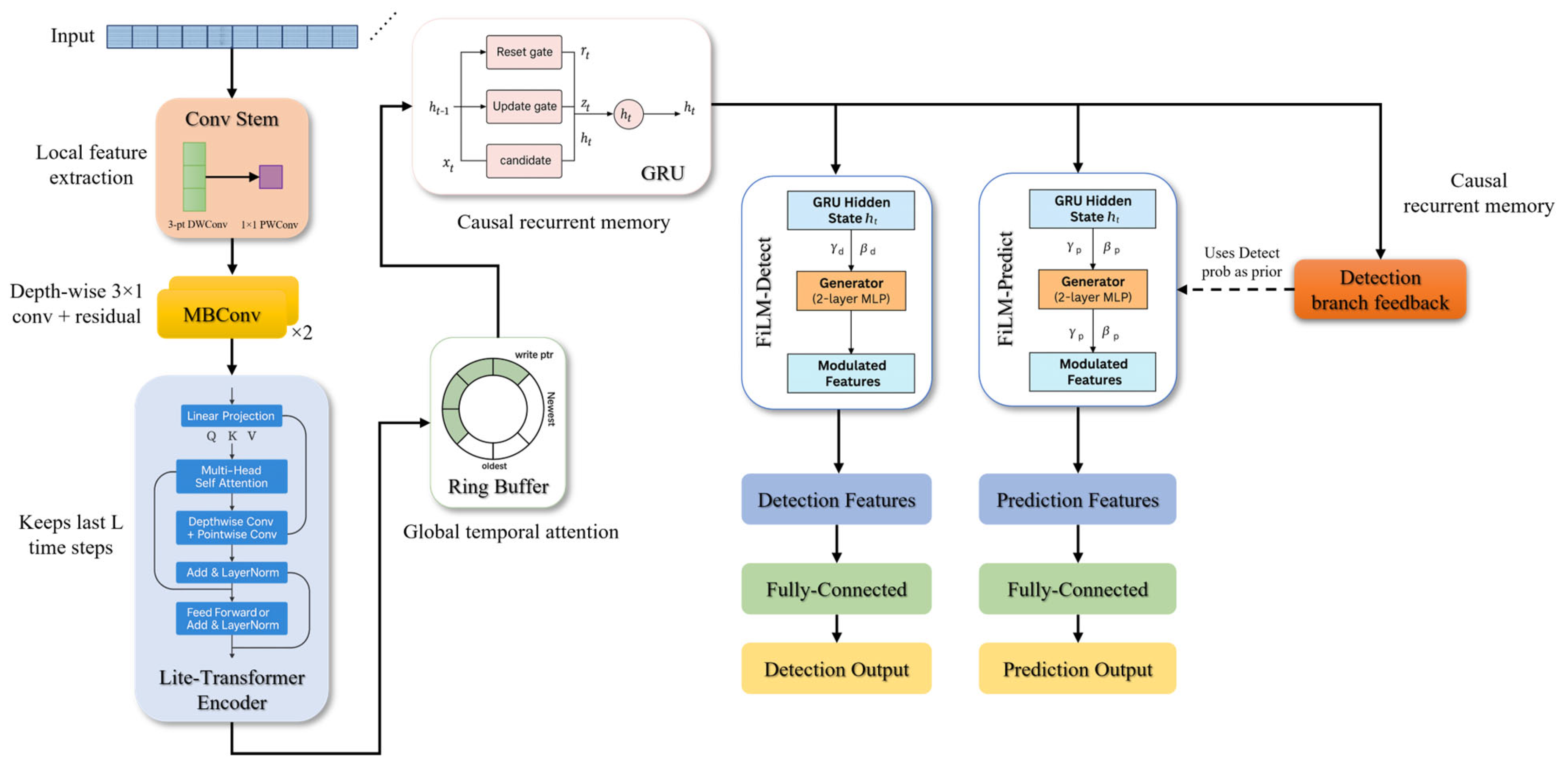

- It introduces the lightweight RGF-Model, achieving unified modeling and real-time inference for prediction and detection through FiLM-modulated GRU gating.

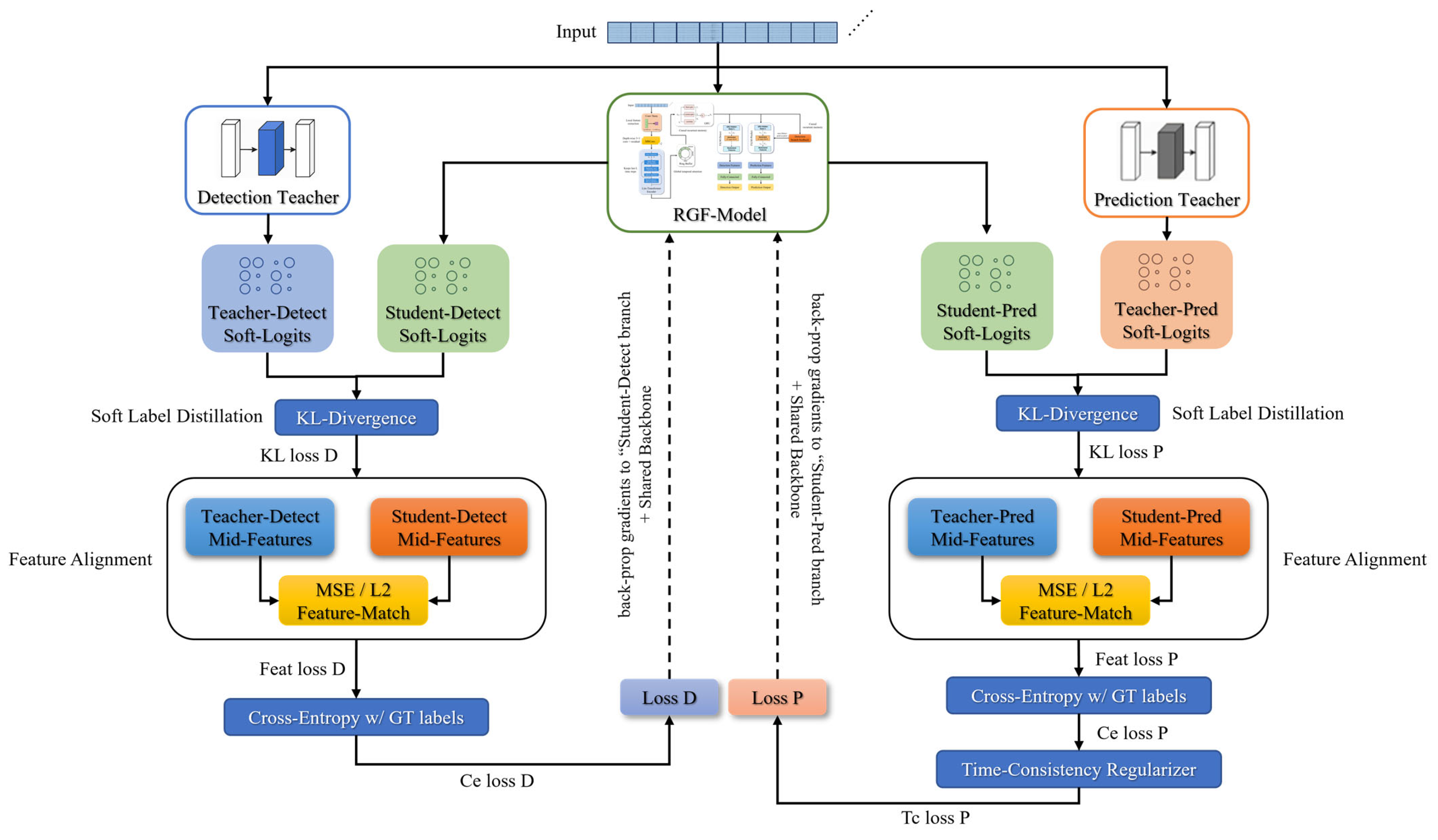

- It develops a multi-teacher knowledge distillation framework that transfers knowledge from detection and prediction teachers to a lightweight student and incorporates a SFPM to enhance Sen to preictal signals.

- A ring-structured gating mechanism that enforces causal consistency in temporal tasks was designed, enabling online dual-task operation on resource-constrained devices.

- It demonstrates on the CHB-MIT and Siena datasets that the model significantly reduces parameter count and computational costs while achieving prediction and detection performance comparable to or better than mainstream methods.

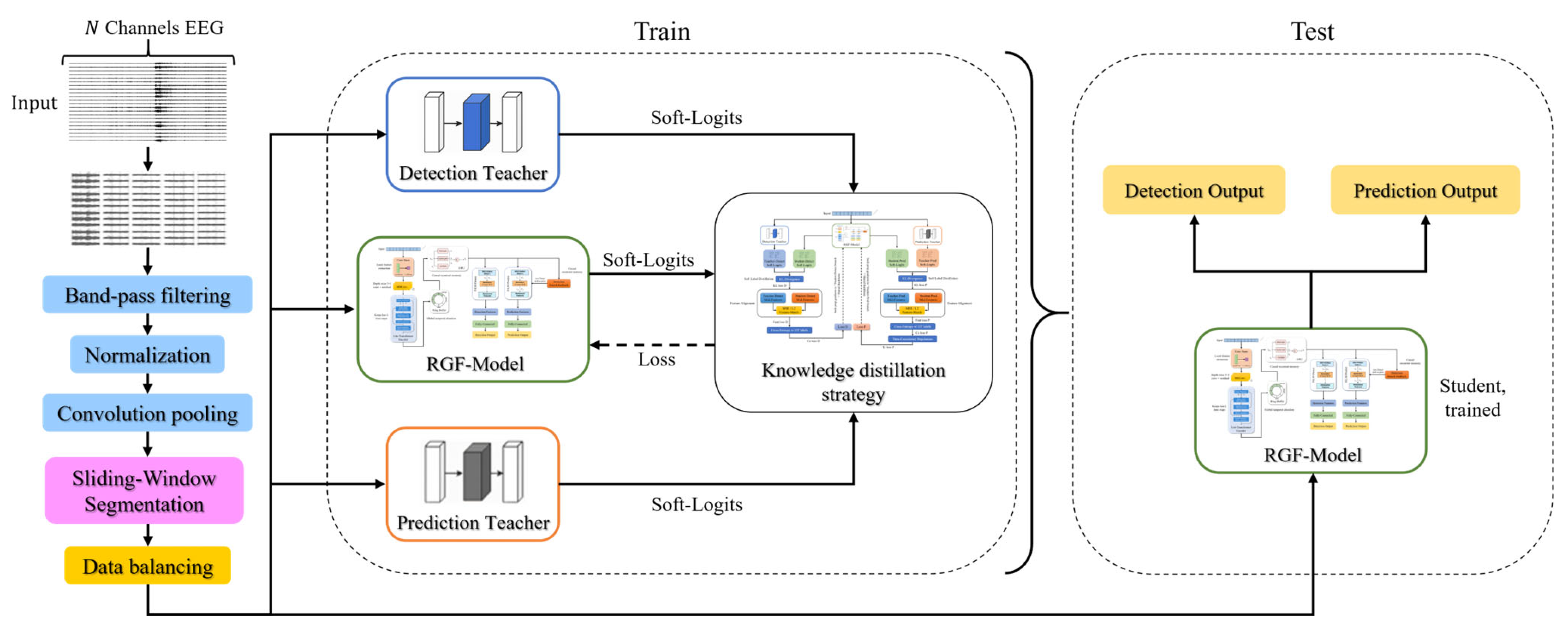

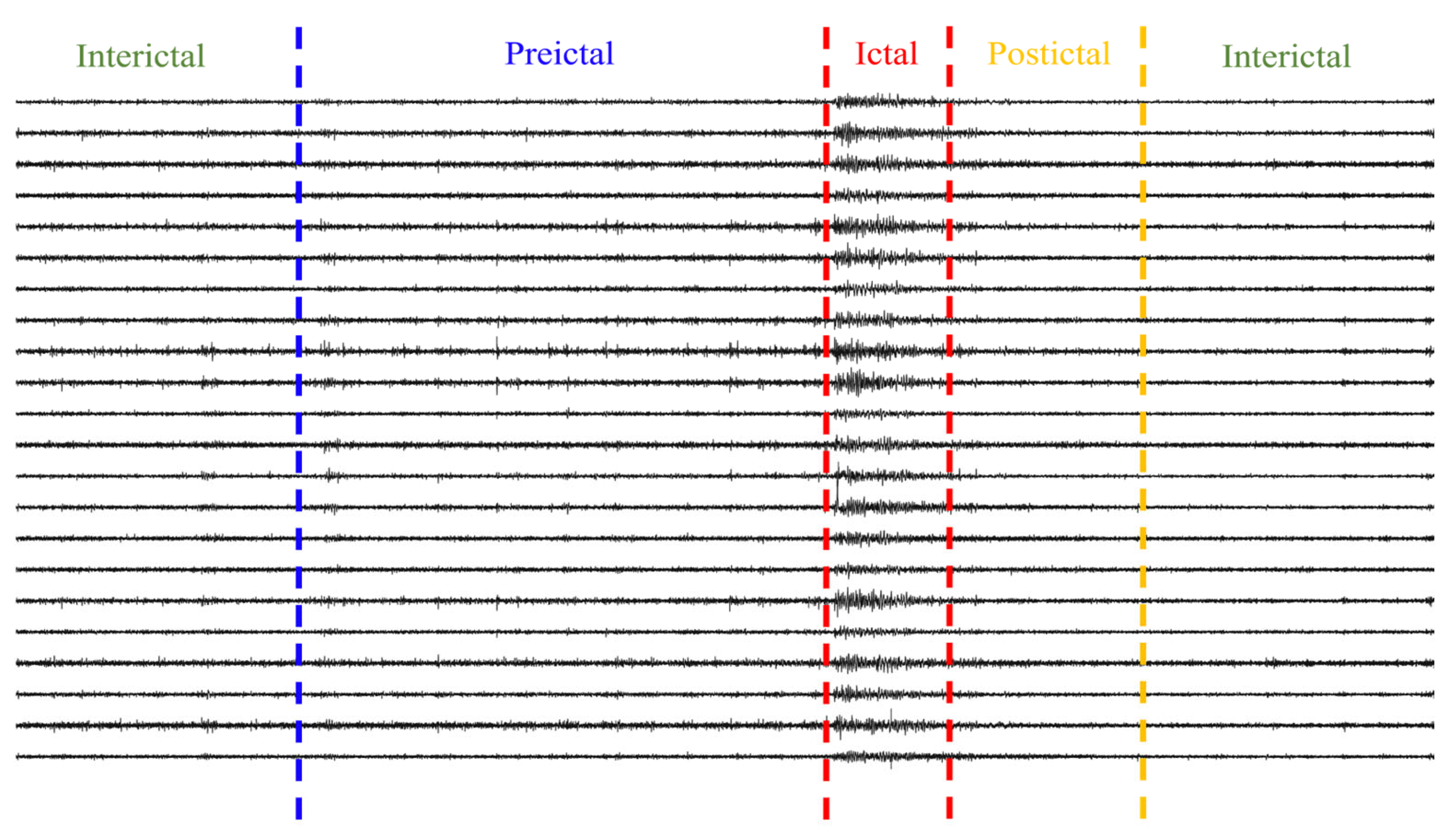

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

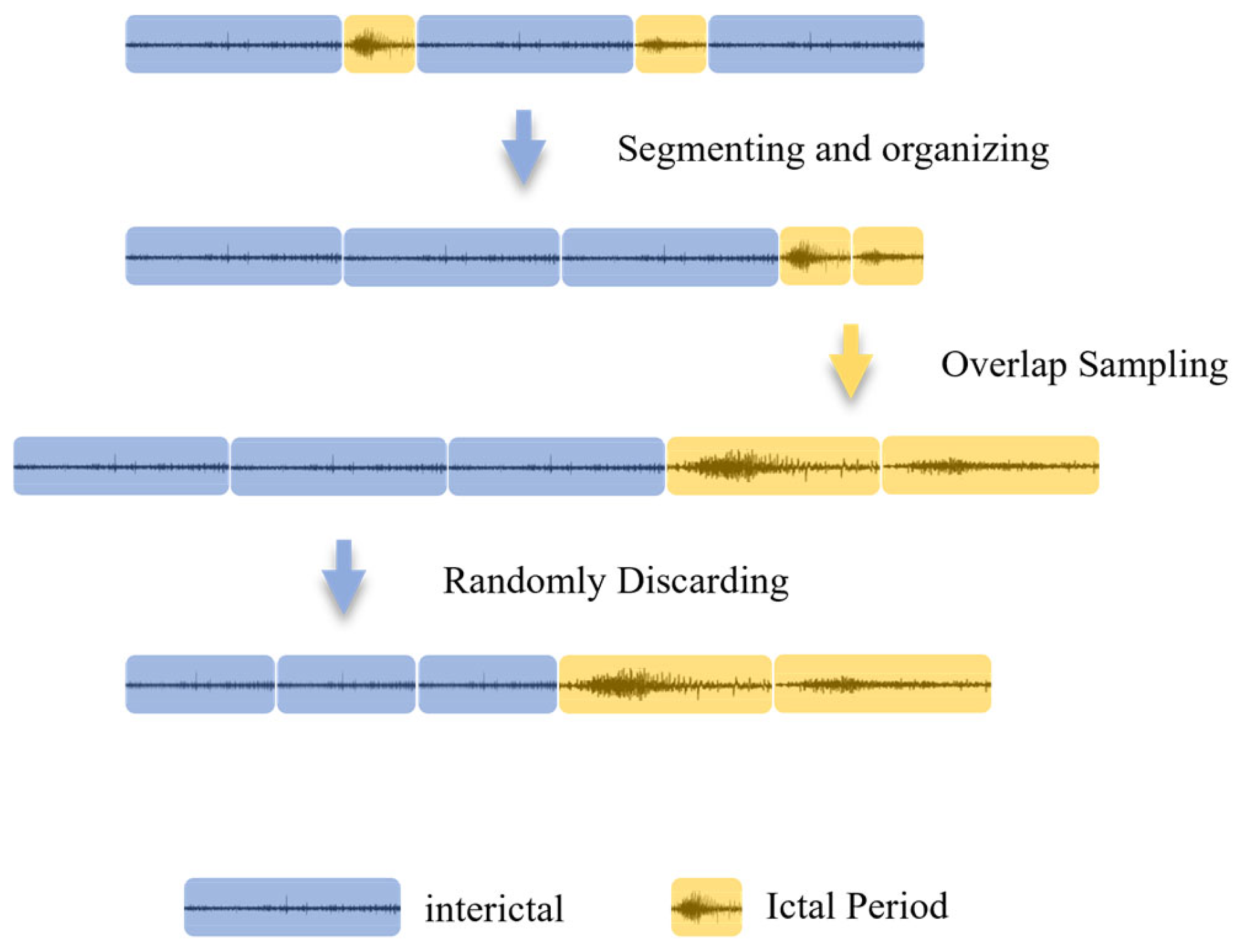

2.2. Data Preprocessing

2.3. Teacher Model

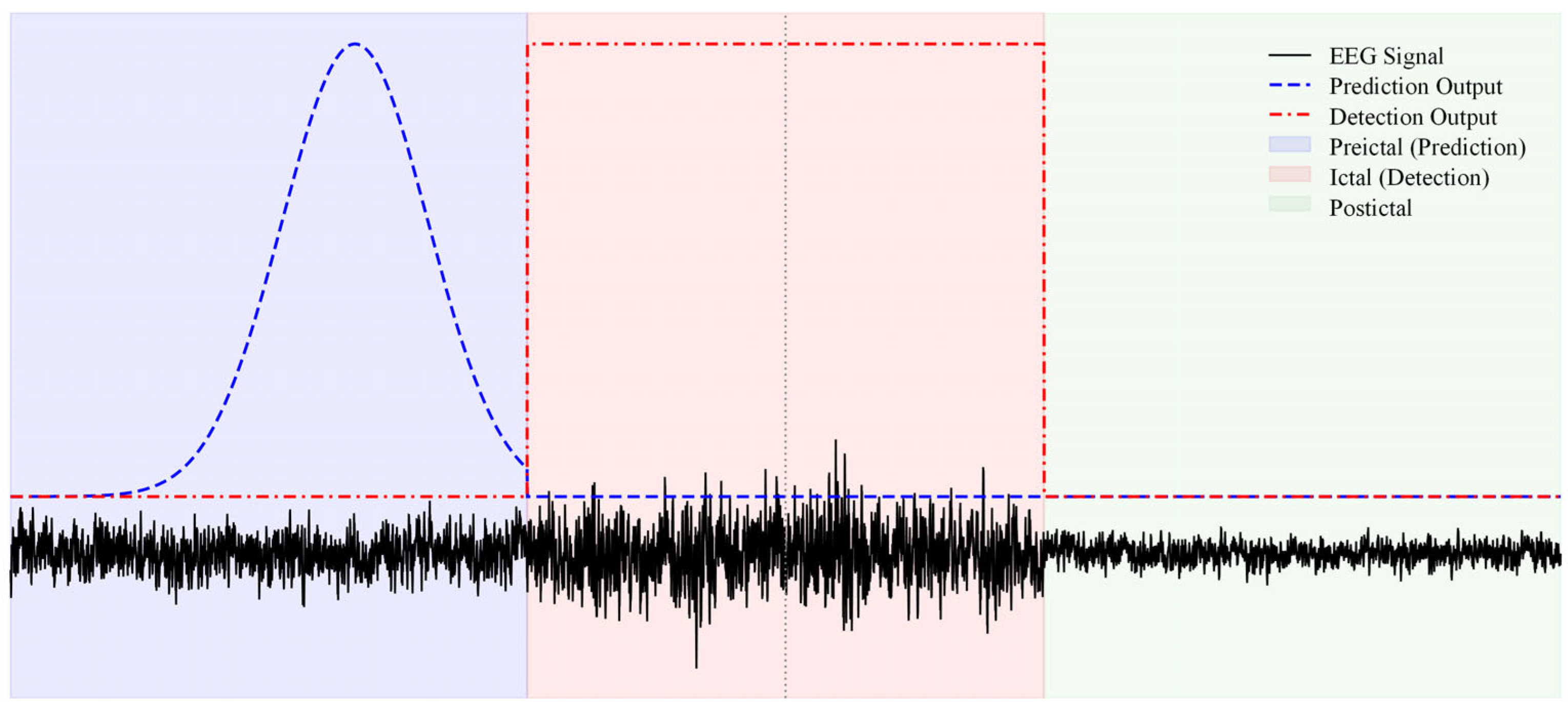

2.4. RGF-Model

2.5. Multi-Teacher Knowledge Distillation Strategy

2.6. Training and Loss Function

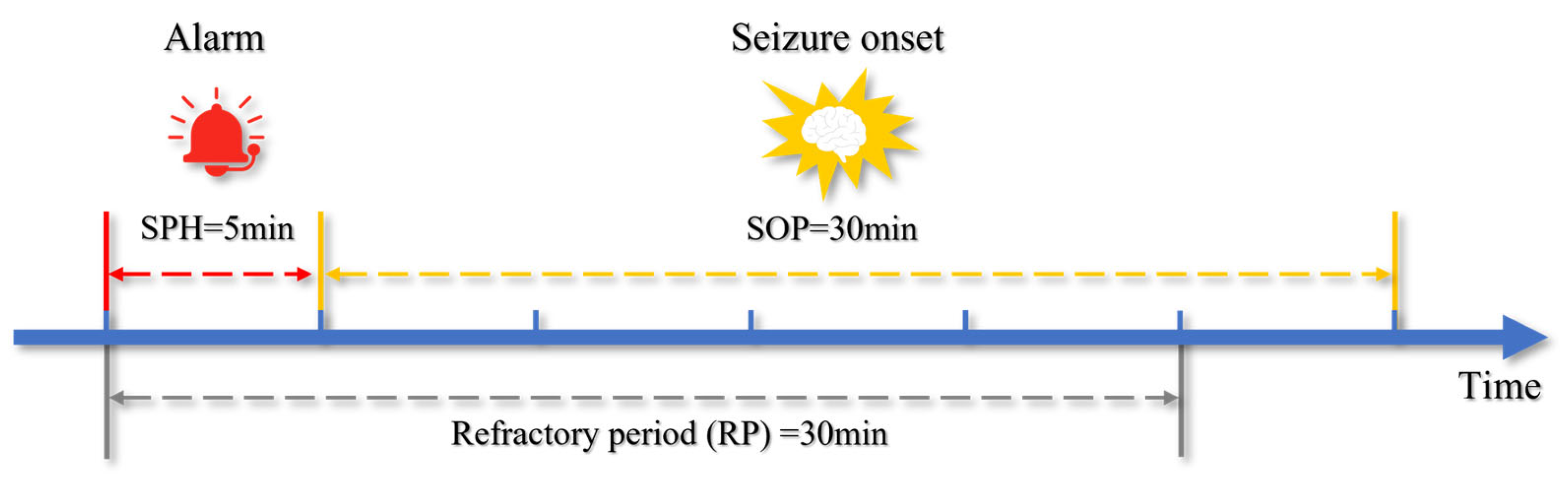

2.7. Postprocessing

2.8. Experimental Environment

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Settings

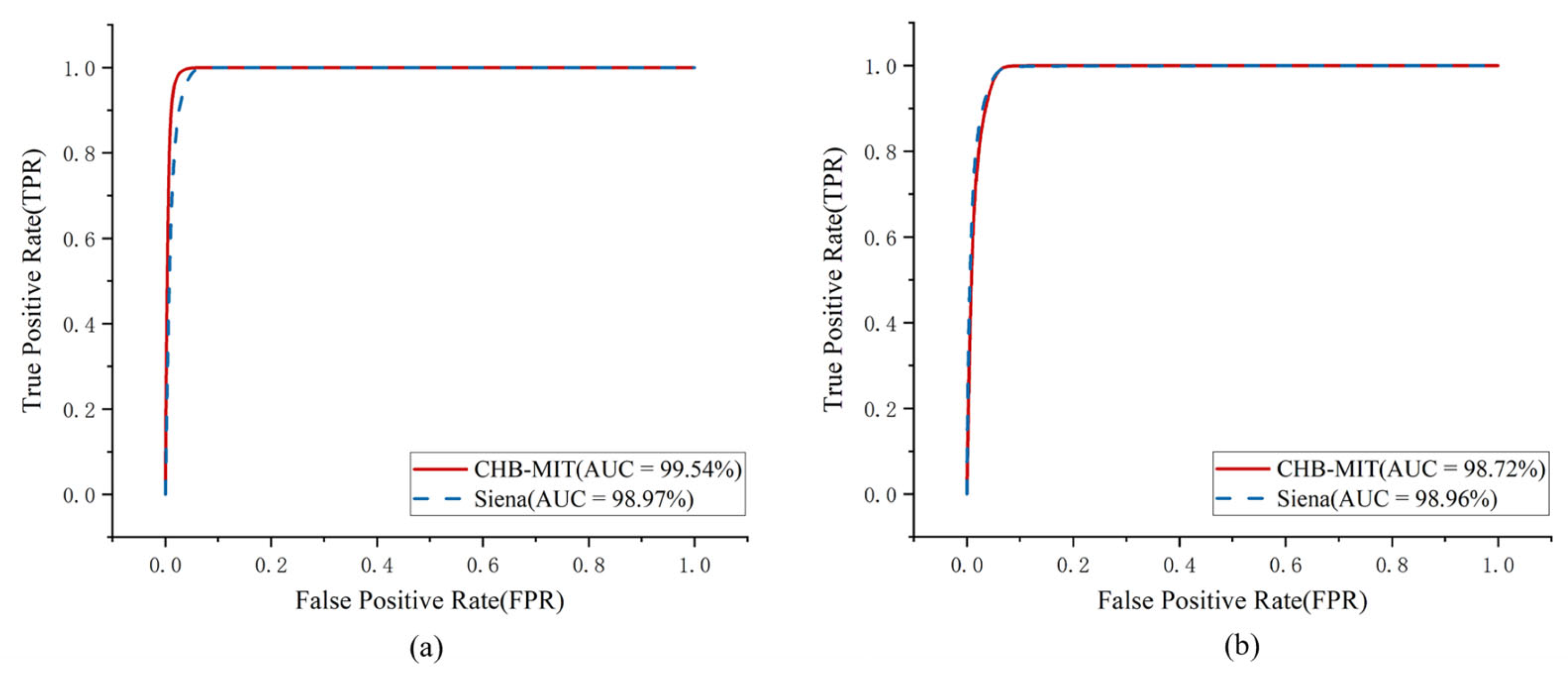

3.2. Experimental Results

3.3. Ablation Experiment

3.4. Cross Subject and Cross Dataset Generalization Experiments

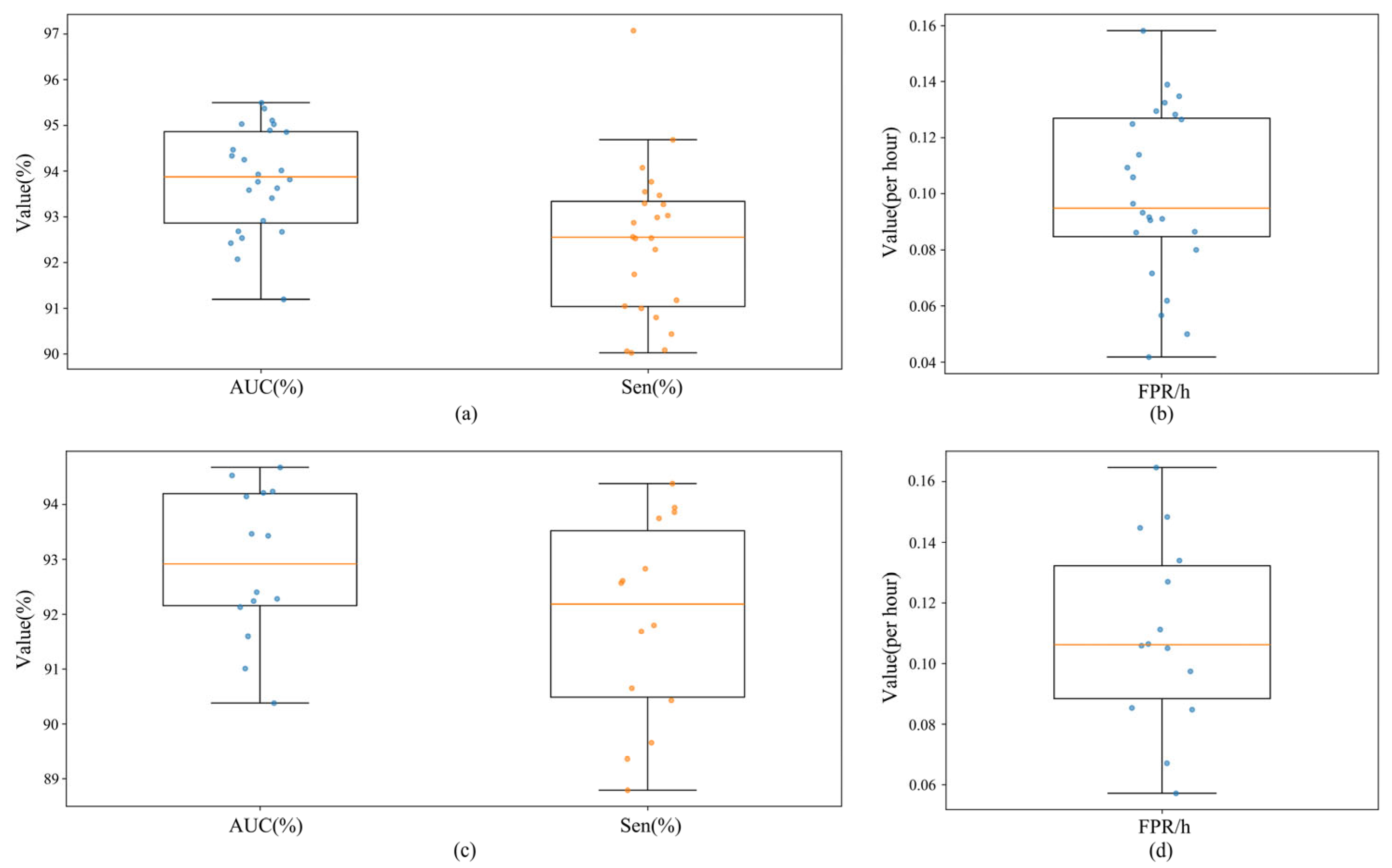

3.5. Robustness Testing of Teacher Model Random Pairing

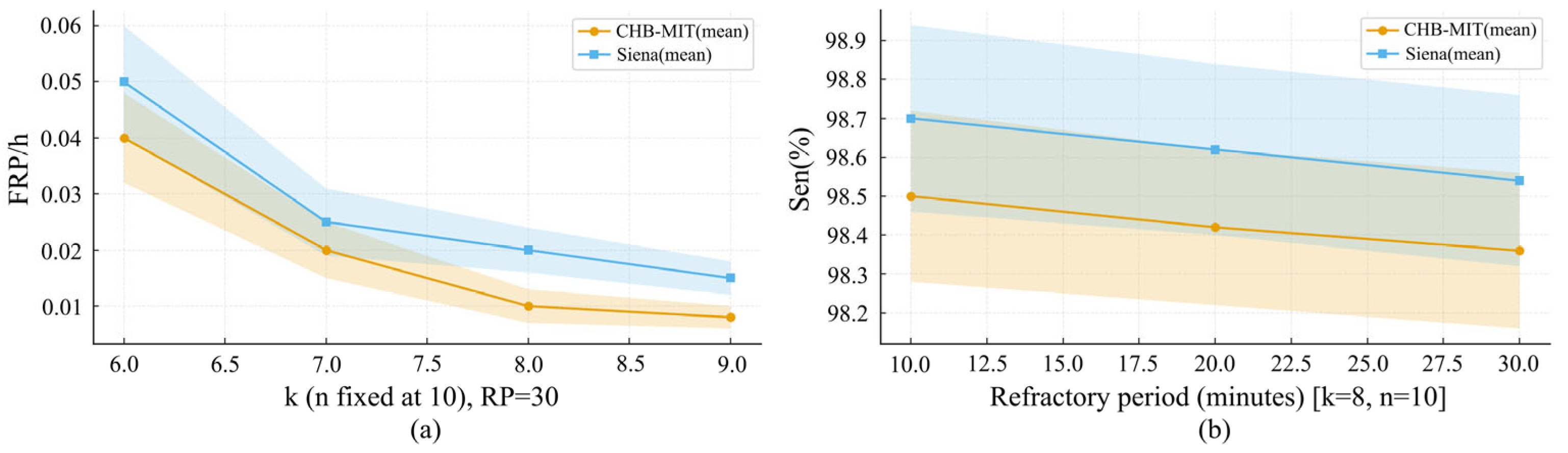

3.6. k-of-n Voting and Refractory Period Sen Analysis

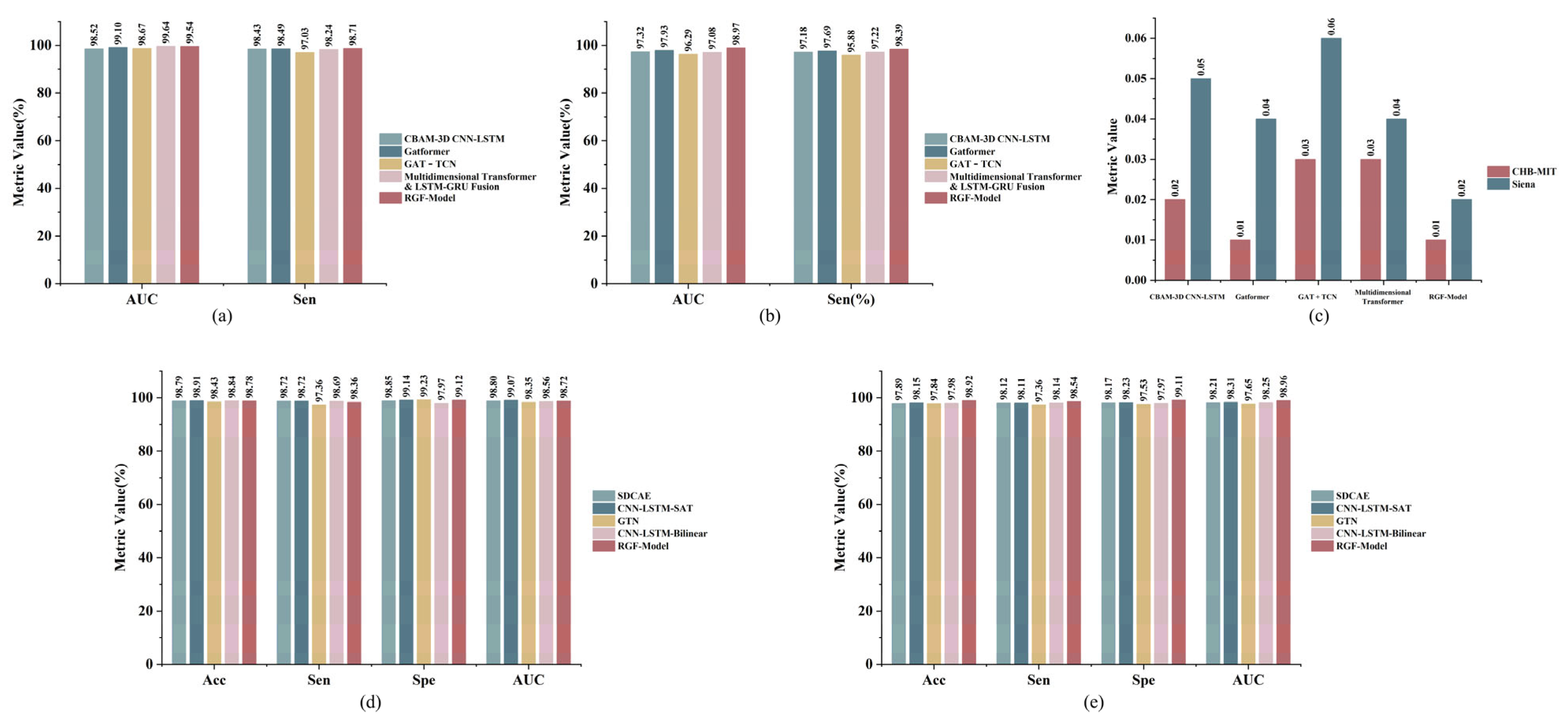

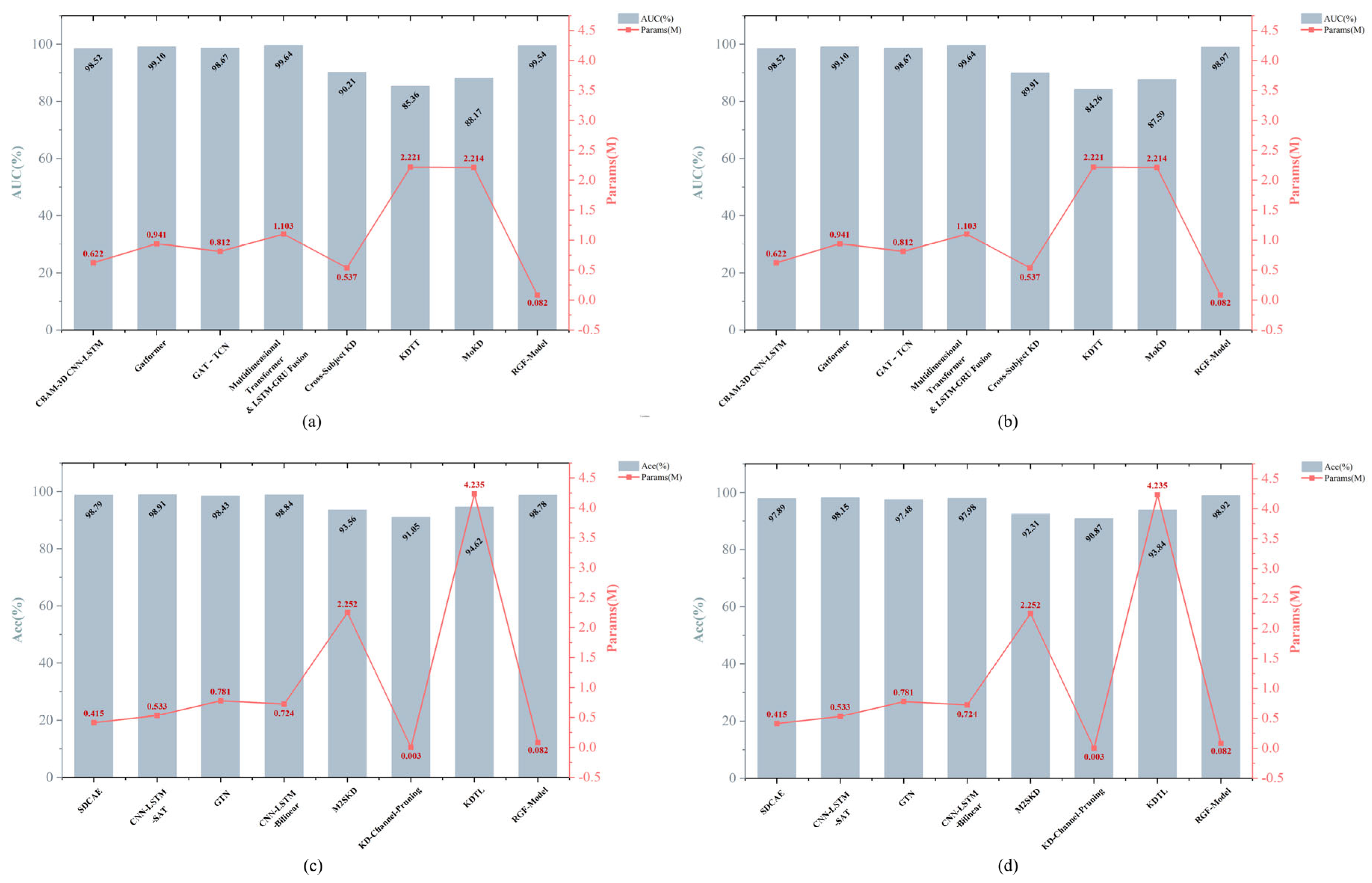

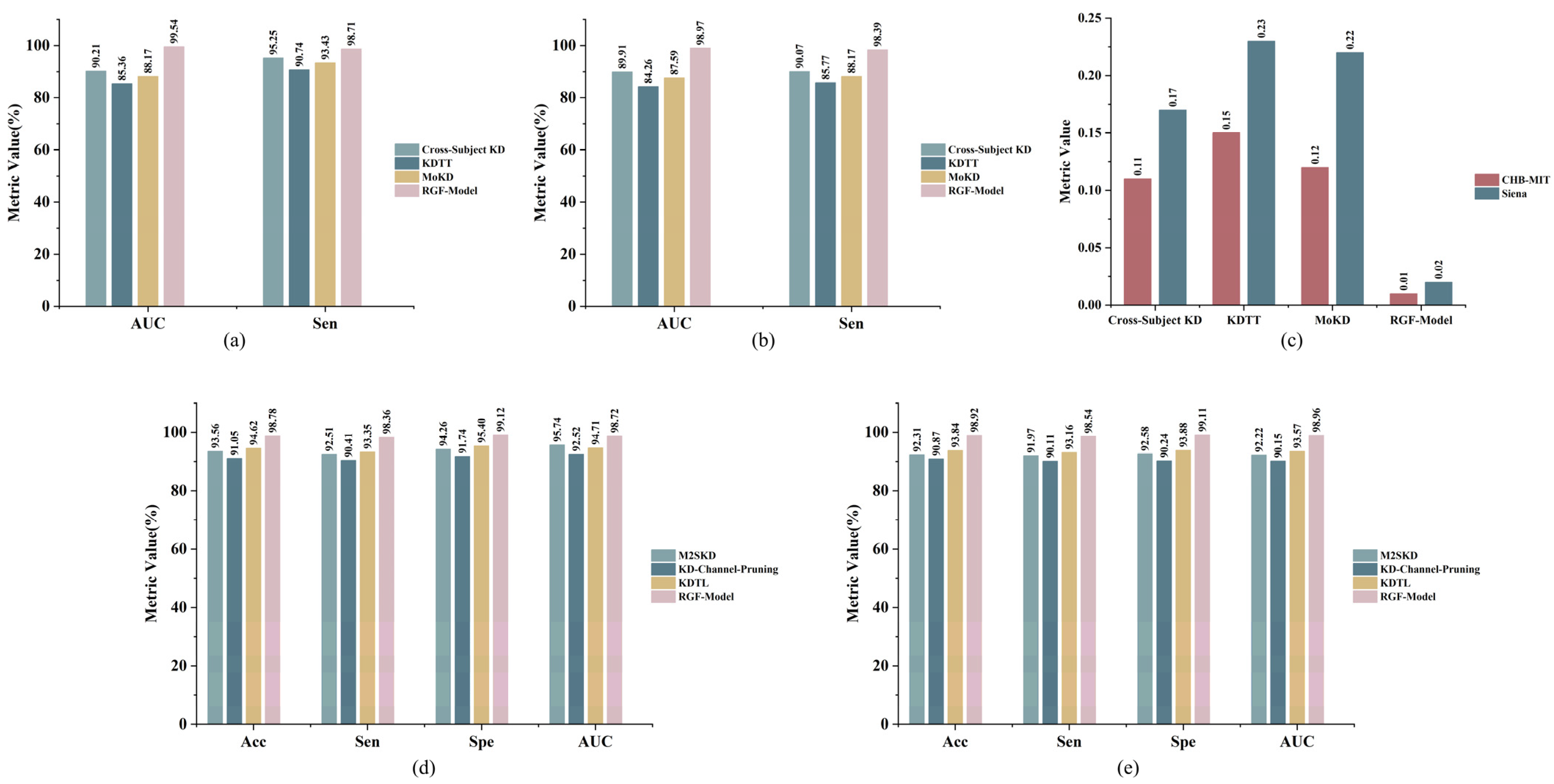

3.7. Comparative Experiments with Other Methods

3.8. On-Device Efficiency Benchmarks

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, X.Z.; Zhang, X.L.; Huang, Q.; Chen, F.M. A review of epilepsy detection and prediction methods based on EEG signal processing and deep learning. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1468967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.X.; Wu, Q.Y.; Mao, H.F.; Guo, L.H. Epileptic Seizure Detection Based on Path Signature and Bi-LSTM Network with Attention Mechanism. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2024, 32, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frauscher, B.; Rossetti, A.O.; Beniczky, S. Recent advances in clinical electroencephalography. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2024, 37, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.S.; Wang, Y.L.; Liu, D.W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.J. Automated recognition of epilepsy from EEG signals using a combining space-time algorithm of CNN-LSTM. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Cao, W.; Zhang, A.Y. Multi-stream feature fusion of vision transformer and CNN for precise epileptic seizure detection from EEG signals. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, D.Z.; He, L.D.; Dong, X.C.; Li, H.T.; Zhong, X.W.; Liu, G.Y.; Zhou, W.D. Epileptic Seizure Prediction Using Spatiotemporal Feature Fusion on EEG. Int. J. Neural Syst. 2024, 34, 2450041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, Y.F.; He, Z.P.; Chen, Z.Y.; Zhou, Y. Combining temporal and spatial attention for seizure prediction. Health Inf. Sci. Syst. 2023, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Pan, W.X.; Liu, J.X.; Shang, J.L. Epileptic seizure prediction via multidimensional transformer and recurrent neural network fusion. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhameed, A.; Bayoumi, M. A Deep Learning Approach for Automatic Seizure Detection in Children with Epilepsy. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 650050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Li, S.S.; Cai, L.H. Multi-dimensional hybrid bilinear CNN-LSTM models for epileptic seizure detection and prediction using EEG signals. J. Neural Eng. 2024, 21, 066045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.S.; Park, H.J.; Kim, J.E.; Kim, H.J.; Chon, S.; Kim, S.; Jang, J.; Kim, J.K.; Jang, S.; Gil, Y.; et al. Compressed Deep Learning to Classify Arrhythmia in an Embedded Wearable Device. Sensors 2022, 22, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadatnejad, S.; Oveisi, M.; Hashemi, M. LSTM-Based ECG Classification for Continuous Monitoring on Personal Wearable Devices. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2020, 24, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gou, J.P.; Yu, B.S.; Maybank, S.J.; Tao, D.C. Knowledge Distillation: A Survey. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2021, 129, 1789–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Li, G.Q.; Han, S.; Shi, L.P.; Xie, Y. Model Compression and Hardware Acceleration for Neural Networks: A Comprehensive Survey. Proc. IEEE 2020, 108, 485–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, H.; Meng, L. Model Compression for Deep Neural Networks: A Survey. Computers 2023, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, G.; Cho, Y.; Lee, J.H.; Kang, M.; Choi, G.; Kim, D. Difficulty level-based knowledge distillation. Neurocomputing 2024, 606, 128375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.P.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z.T.; Yang, X.M. Interactive Knowledge Distillation for image classification. Neurocomputing 2021, 449, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghersalimi, S.; Amirshahi, A.; Forooghifar, F.; Teijeiro, T.; Aminifar, A.; Atienza, D. M2SKD: Multi-to-Single Knowledge Distillation of Real-Time Epileptic Seizure Detection for Low-Power Wearable Systems. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2024, 15, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Yang, J.; Sawan, M. Bridging the gap between patient-specific and patient-independent seizure prediction via knowledge distillation. J. Neural Eng. 2022, 19, 036035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.W.; Li, S.Y.; Wu, D.R. Canine EEG helps human: Cross-species and cross-modality epileptic seizure detection via multi-space alignment. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2025, 12, nwaf086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Tan, C.; Tang, K. An optimization model for arterial coordination control based on sampled vehicle trajectories: The STREAM model. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 109, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.C.; Zheng, S.J.; Chen, W.N.; Du, G.Q.; Fu, Q.Z.; Jiang, H.W. A scheme combining feature fusion and hybrid deep learning models for epileptic seizure detection and prediction. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Kim, M.J.; Yum, M.S.; Jeong, D.H. Deep Convolutional Gated Recurrent Unit Combined with Attention Mechanism to Classify Pre-Ictal from Interictal EEG with Minimized Number of Channels. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weerakody, P.B.; Wong, K.W.; Wang, G.J. Cyclic Gate Recurrent Neural Networks for Time Series Data with Missing Values. Neural Process. Lett. 2023, 55, 1527–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, G.M.; Sangeetha, S.K.B. Improved Birthweight Prediction with Feature-Wise Linear Modulation, GRU, and Attention Mechanism in Ultrasound Data. J. Ultrasound Med. 2025, 44, 711–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoeb, A.H. Application of Machine Learning to Epileptic Seizure Onset Detection and Treatment. Ph.D. Thesis, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Qin, X.L.; Wen, H.; Li, F.; Lin, X.G. Patient-specific approach using data fusion and adversarial training for epileptic seizure prediction. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1172987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhao, G.; Muir, D.R.; Ling, Y.; Burelo, K.; Khoe, M.; Wang, D.; Xing, Y.; Qiao, N. Real-time sub-milliwatt epilepsy detection implemented on a spiking neural network edge inference processor. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 183, 109225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirsa, V.K.; Proix, T.; Perdikis, D.; Woodman, M.M.; Wang, H.; Gonzalez-Martinez, J.; Bernard, C.; Bénar, C.; Guye, M.; Chauvel, P.; et al. The Virtual Epileptic Patient: Individualized whole-brain models of epilepsy spread. Neuroimage 2017, 145, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.C.; Li, C.; Liu, X.; Qian, R.B.; Song, R.C.; Chen, X. Patient-Specific Seizure Prediction via Adder Network and Supervised Contrastive Learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2022, 30, 1536–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, H.; Bayoumi, M.A. Efficient Epileptic Seizure Prediction Based on Deep Learning. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2019, 13, 804–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Huang, X.Y.; Song, R.C.; Qian, R.B.; Liu, X.; Chen, X. EEG-based seizure prediction via Transformer guided CNN. Measurement 2022, 203, 111948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.G.; Cho, A.; Kim, H.; Kim, K.J. Single-channel seizure detection with clinical confirmation of seizure locations using CHB-MIT dataset. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1389731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila, C.G.; Bott, F.S.; Tiemann, L.; Hohn, V.D.; May, E.S.; Nickel, M.M.; Zebhauser, P.T.; Gross, J.; Ploner, M. DISCOVER-EEG: An open, fully automated EEG pipeline for biomarker discovery in clinical neuroscience. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandecasteele, K.; De Cooman, T.; Dan, J.; Cleeren, E.; Van Huffel, S.; Hunyadi, B.; Van Paesschen, W. Visual seizure annotation and automated seizure detection using behind-the-ear electroencephalographic channels. Epilepsia 2020, 61, 766–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Mengoni, P. Seizure classification with selected frequency bands and EEG montages: A natural language processing approach. Brain Inform. 2022, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.Y.; Tang, J.; Shen, Y.M. Long time series of ocean wave prediction based on PatchTST model. Ocean Eng. 2024, 301, 117572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, E.; Angelova, M.; Karmakar, C. Epileptic seizure detection using CHB-MIT dataset: The overlooked perspectives. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2024, 11, 230601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Wen, A.H.; Sun, L.; Wang, H.; Guo, Y.J.; Ren, Y.D. An Epileptic Seizure Prediction Method Based on CBAM-3D CNN-LSTM Model. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. JTEHM 2023, 11, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, T.; Jrad, N.; Abdallah, F.; Humeau-Heurtier, A.; Van Bogaert, P. A self-attention model for cross-subject seizure detection. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 165, 107427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.; Xu, F.Z. Epileptic EEG Classification via Graph Transformer Network. Int. J. Neural Syst. 2023, 33, 2350042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.H.; Cherian, P.J.; Caicedo, A.; Naulaers, G.; De Vos, M.; Van Huffel, S. Neonatal Seizure Detection Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Int. J. Neural Syst. 2019, 29, 1850011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.N.; Chu, D.Y.; He, J.T.; Xue, M.R.; Jia, W.K.; Xu, F.Z.; Zheng, Y.J. Interactive local and global feature coupling for EEG-based epileptic seizure detection. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2023, 81, 104441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freestone, D.R.; Karoly, P.J.; Cook, M.J. A forward-looking review of seizure prediction. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2017, 30, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, N.D.; Nguyen, A.D.; Kuhlmann, L.; Bonyadi, M.R.; Yang, J.W.; Ippolito, S.; Kavehei, O. Convolutional neural networks for seizure prediction using intracranial and scalp electroencephalogram. Neural Netw. 2018, 105, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonyakitanont, P.; Lek-Uthai, A.; Songsiri, J. ScoreNet: A Neural Network-Based Post-Processing Model for Identifying Epileptic Seizure Onset and Offset in EEGs. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2021, 29, 2474–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, Y.D.; An, G.Y.; Wei, Z.; Chen, H.M. Epilepsy detection based on multi-head self-attention mechanism. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0305166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, T.; Guddati, M.N. Full wave simulation of arterial response under acoustic radiation force. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 149, 106021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, R.; Mukherjee, I. Deep learning based efficient epileptic seizure prediction with EEG channel optimization. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2021, 68, 102767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Liu, A.P.; Wu, L.; Li, C.; Qian, R.B.; Ward, R.K.; Chen, X. Semisupervised Seizure Prediction in Scalp EEG Using Consistency Regularization. J. Healthc. Eng. 2022, 2022, 1573076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonetti, F.; Zotto, M.D.; Minasian, R. SymTFTs for Continuous non-Abelian Symmetries. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.12347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaravel, V.P.; Pale, U.; Teijeiro, T.; Farella, E.; Atienza, D. Knowledge Distillation-based Channel Reduction for Wearable EEG Applications. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Jadli, H.; Priya, R.P.; Prasath, V.B.S. KDTL: Knowledge-distilled transfer learning framework for diagnosing mental disorders using EEG spectrograms. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 18919–18934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.D.; Hwang, K.; Li, K.Q.; Wu, J.; Ji, T.K. Graph-generative neural network for EEG-based epileptic seizure detection via discovery of dynamic brain functional connectivity. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, M.a. Automatic epilepsy detection with an attention-based multiscale residual network. Sheng Wu Yi Xue Gong Cheng Xue Za Zhi 2024, 41, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.Y.; Wang, W.J.; Jiao, H.L. LightSeizureNet: A Lightweight Deep Learning Model for Real-Time Epileptic Seizure Detection. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2023, 27, 1845–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.Y.; Li, J.Y.; Jiang, X.C. Research on information leakage in time series prediction based on empirical mode decomposition. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekmatmanesh, A.; Wu, H.; Li, M.; Handroos, H. A Combined Projection for Remote Control of a Vehicle Based on Movement Imagination: A Single Trial Brain Computer Interface Study. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 6165–6174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. of Patients | Interictal Hours (h) | No. of Seizures |

|---|---|---|

| Pt1 | 17.7 | 7 |

| Pt2 | 23.1 | 3 |

| Pt3 | 21.9 | 6 |

| Pt5 | 14.4 | 5 |

| Pt8 | 3.5 | 5 |

| Pt9 | 50 | 4 |

| Pt10 | 26 | 6 |

| Pt13 | 15.6 | 5 |

| Pt14 | 4.2 | 5 |

| Pt16 | 5.6 | 10 |

| Pt17 | 10.1 | 3 |

| Pt18 | 25 | 6 |

| Pt19 | 23.1 | 3 |

| Pt20 | 20.8 | 5 |

| Pt21 | 21.6 | 4 |

| Pt23 | 14.2 | 5 |

| Total | 296.8 | 82 |

| No. of Patients | Interictal Hours (h) | No. of Seizures |

|---|---|---|

| PN00 | 3.2 | 5 |

| PN05 | 6 | 3 |

| PN06 | 12 | 5 |

| PN09 | 6.8 | 3 |

| PN10 | 16.6 | 10 |

| PN12 | 4 | 4 |

| PN13 | 5.6 | 3 |

| PN14 | 23.4 | 4 |

| Total | 77.6 | 37 |

| Prediction Methods | Detection Methods | AUC (%) | Sen (%) | FPR/h | Sig. (%) | Params (M) | Model Size (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBAM-3D CNN -LSTM [39] | SDCAE [9] | 98.40 ± 1.42 | 98.21 ± 2.02 | 0.03 ± 0.015 | 100% | 0.060 | 0.24 |

| CNN-LSTM-SAT [40] | 98.33 ± 1.77 | 97.94 ± 1.93 | 0.02 ± 0.014 | 100% | 0.064 | 0.26 | |

| GTN [41] | 98.71 ± 1.64 | 98.45 ± 1.79 | 0.01 ± 0.005 | 100% | 0.073 | 0.29 | |

| CNN-LSTM-Bilinear [10] | 98.55 ± 1.56 | 98.28 ± 2.11 | 0.02 ± 0.009 | 100% | 0.068 | 0.27 | |

| Gatformer [7] | SDCAE [9] | 98.46 ± 1.29 | 97.85 ± 1.64 | 0.02 ± 0.013 | 100% | 0.071 | 0.28 |

| CNN-LSTM-SAT [40] | 98.77 ± 1.29 | 98.50 ± 1.79 | 0.01 ± 0.005 | 100% | 0.076 | 0.30 | |

| GTN [41] | 99.02 ± 1.23 | 98.55 ± 1.87 | 0.01 ± 0.004 | 100% | 0.084 | 0.34 | |

| CNN-LSTM-Bilinear [10] | 98.88 ± 1.72 | 98.43 ± 1.96 | 0.01 ± 0.005 | 100% | 0.081 | 0.32 | |

| GAT-TCN [6] | SDCAE [9] | 97.95 ± 1.56 | 96.81 ± 2.29 | 0.04 ± 0.016 | 100% | 0.066 | 0.26 |

| CNN-LSTM-SAT [40] | 98.22 ± 1.62 | 97.40 ± 1.70 | 0.03 ± 0.014 | 100% | 0.072 | 0.28 | |

| GTN [41] | 97.68 ± 1.21 | 96.55 ± 2.01 | 0.05 ± 0.019 | 100% | 0.078 | 0.31 | |

| CNN-LSTM-Bilinear [10] | 98.11 ± 1.78 | 97.02 ± 2.09 | 0.04 ± 0.025 | 100% | 0.074 | 0.30 | |

| Multidimensional Transformer & LSTM-GRU Fusion [8] | SDCAE [9] | 99.31 ± 1.70 | 98.62 ± 1.55 | 0.02 ± 0.010 | 100% | 0.079 | 0.32 |

| CNN-LSTM-SAT [40] | 99.54 ± 1.33 | 98.71 ± 2.11 | 0.01 ± 0.006 | 100% | 0.082 | 0.33 | |

| GTN [41] | 99.12 ± 1.31 | 98.37 ± 1.67 | 0.02 ± 0.012 | 100% | 0.091 | 0.36 | |

| CNN-LSTM-Bilinear [10] | 99.43 ± 1.31 | 98.59 ± 1.57 | 0.01 ± 0.004 | 100% | 0.086 | 0.34 | |

| Aver | 98.66 | 98.02 | 0.02 | - | 0.075 | 0.30 |

| Prediction Methods | Detection Methods | AUC (%) | Sen (%) | FPR/h | Sig. (%) | Params (M) | Model Size (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBAM-3D CNN -LSTM [39] | SDCAE [9] | 97.12 ± 1.65 | 96.83 ± 2.24 | 0.05 ± 0.035 | 100% | 0.060 | 0.24 |

| CNN-LSTM-SAT [40] | 97.30 ± 2.29 | 97.74 ± 1.91 | 0.03 ± 0.021 | 100% | 0.064 | 0.26 | |

| GTN [41] | 96.95 ± 1.67 | 96.43 ± 2.98 | 0.02 ± 0.014 | 100% | 0.073 | 0.29 | |

| CNN-LSTM-Bilinear [10] | 97.25 ± 1.81 | 96.98 ± 2.99 | 0.05 ± 0.028 | 100% | 0.068 | 0.27 | |

| Gatformer [7] | SDCAE [9] | 97.47 ± 1.93 | 97.18 ± 3.16 | 0.04 ± 0.013 | 100% | 0.071 | 0.28 |

| CNN-LSTM-SAT [40] | 97.68 ± 2.62 | 97.75 ± 2.34 | 0.03 ± 0.014 | 100% | 0.076 | 0.31 | |

| GTN [41] | 98.21 ± 2.37 | 97.93 ± 3.14 | 0.04 ± 0.022 | 100% | 0.084 | 0.34 | |

| CNN-LSTM-Bilinear [10] | 97.45 ± 2.20 | 97.54 ± 2.42 | 0.02 ± 0.011 | 100% | 0.081 | 0.32 | |

| GAT-TCN [6] | SDCAE [9] | 96.95 ± 1.54 | 96.62 ± 2.74 | 0.06 ± 0.033 | 100% | 0.066 | 0.26 |

| CNN-LSTM-SAT [40] | 97.11 ± 2.45 | 96.81 ± 1.92 | 0.04 ± 0.019 | 100% | 0.072 | 0.28 | |

| GTN [41] | 96.76 ± 2.01 | 96.38 ± 3.06 | 0.05 ± 0.029 | 100% | 0.078 | 0.31 | |

| CNN-LSTM-Bilinear [10] | 97.09 ± 2.54 | 96.77 ± 2.22 | 0.05 ± 0.024 | 100% | 0.074 | 0.30 | |

| Multidimensional Transformer & LSTM-GRU Fusion [8] | SDCAE [9] | 98.03 ± 1.83 | 97.97 ± 2.17 | 0.04 ± 0.021 | 100% | 0.079 | 0.32 |

| CNN-LSTM-SAT [40] | 98.97 ± 1.57 | 98.39 ± 1.81 | 0.02 ± 0.009 | 100% | 0.082 | 0.33 | |

| GTN [41] | 98.12 ± 2.63 | 97.87 ± 2.56 | 0.04 ± 0.016 | 100% | 0.091 | 0.35 | |

| CNN-LSTM-Bilinear [10] | 98.43 ± 1.79 | 98.29 ± 2.47 | 0.02 ± 0.015 | 100% | 0.086 | 0.34 | |

| Aver | 97.56 | 97.34 | 0.04 | - | 0.075 | 0.30 |

| Prediction Methods | Detection Methods | Acc (%) | Sen (%) | Spe (%) | AUC (%) | Params (M) | Model Size (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBAM-3D CNN -LSTM [39] | SDCAE [9] | 98.34 ± 1.20 | 98.36 ± 1.43 | 98.33 ± 1.46 | 98.82 ± 0.97 | 0.060 | 0.24 |

| CNN-LSTM -SAT [40] | 98.33 ± 1.04 | 98.14 ± 1.30 | 98.52 ± 0.84 | 98.32 ± 1.18 | 0.064 | 0.26 | |

| GTN [41] | 98.01 ± 1.05 | 97.41 ± 1.47 | 98.65 ± 1.01 | 98.23 ± 1.05 | 0.073 | 0.29 | |

| CNN-LSTM -Bilinear [10] | 98.46 ± 1.14 | 98.27 ± 1.20 | 98.70 ± 0.99 | 98.56 ± 1.10 | 0.068 | 0.27 | |

| Gatformer [7] | SDCAE [9] | 98.57 ± 0.83 | 98.22 ± 1.21 | 98.91 ± 0.96 | 98.54 ± 0.71 | 0.071 | 0.28 |

| CNN-LSTM -SAT [40] | 98.74 ± 1.20 | 98.61 ± 1.16 | 98.94 ± 0.73 | 98.91 ± 0.74 | 0.076 | 0.30 | |

| GTN [41] | 98.62 ± 0.84 | 98.05 ± 1.24 | 99.20 ± 1.01 | 98.75 ± 1.00 | 0.084 | 0.34 | |

| CNN-LSTM -Bilinear [10] | 98.69 ± 1.06 | 98.33 ± 1.30 | 99.02 ± 1.13 | 98.80 ± 0.89 | 0.081 | 0.32 | |

| GAT-TCN [6] | SDCAE [9] | 97.88 ± 1.73 | 97.54 ± 1.24 | 98.21 ± 1.38 | 97.85 ± 1.25 | 0.066 | 0.26 |

| CNN-LSTM -SAT [40] | 98.11 ± 1.09 | 97.72 ± 1.43 | 98.43 ± 1.16 | 98.15 ± 0.98 | 0.072 | 0.28 | |

| GTN [41] | 97.36 ± 1.44 | 96.84 ± 1.24 | 98.25 ± 1.45 | 97.35 ± 1.28 | 0.078 | 0.31 | |

| CNN-LSTM -Bilinear [10] | 97.75 ± 1.45 | 97.19 ± 1.33 | 98.03 ± 1.37 | 97.56 ± 1.53 | 0.074 | 0.30 | |

| Multidimensional Transformer & LSTM-GRU Fusion [8] | SDCAE [9] | 98.72 ± 0.69 | 98.64 ± 1.16 | 98.80 ± 1.04 | 98.90 ± 0.92 | 0.079 | 0.32 |

| CNN-LSTM -SAT [40] | 98.78 ± 1.18 | 98.36 ± 1.46 | 99.12 ± 0.67 | 98.72 ± 1.17 | 0.082 | 0.33 | |

| GTN [41] | 98.56 ± 1.15 | 98.49 ± 1.33 | 98.68 ± 1.15 | 98.85 ± 0.95 | 0.091 | 0.36 | |

| CNN-LSTM -Bilinear [10] | 98.67 ± 0.94 | 98.41 ± 1.34 | 98.93 ± 0.83 | 98.95 ± 0.92 | 0.086 | 0.34 | |

| Aver | 98.35 | 98.04 | 98.67 | 98.45 | 0.075 | 0.30 |

| Prediction Methods | Detection Methods | Acc (%) | Sen (%) | Spe (%) | AUC (%) | Params (M) | Model Size (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBAM-3D CNN -LSTM [39] | SDCAE [9] | 98.63 ± 1.08 | 98.18 ± 1.33 | 98.95 ± 0.71 | 98.62 ± 1.37 | 0.060 | 0.24 |

| CNN-LSTM -SAT [40] | 98.68 ± 1.01 | 98.26 ± 1.50 | 98.82 ± 0.82 | 98.73 ± 1.46 | 0.064 | 0.26 | |

| GTN [41] | 98.72 ± 1.09 | 98.33 ± 1.58 | 98.76 ± 0.91 | 98.74 ± 1.40 | 0.073 | 0.29 | |

| CNN-LSTM -Bilinear [10] | 98.74 ± 1.30 | 98.32 ± 1.58 | 98.88 ± 0.97 | 98.76 ± 1.48 | 0.068 | 0.27 | |

| Gatformer [7] | SDCAE [9] | 98.70 ± 1.24 | 98.31 ± 1.25 | 98.71 ± 1.29 | 98.72 ± 1.23 | 0.071 | 0.28 |

| CNN-LSTM -SAT [40] | 98.78 ± 1.14 | 98.38 ± 1.55 | 98.98 ± 1.13 | 98.84 ± 0.72 | 0.076 | 0.30 | |

| GTN [41] | 98.62 ± 1.13 | 98.42 ± 1.70 | 98.63 ± 1.05 | 98.84 ± 0.79 | 0.084 | 0.34 | |

| CNN-LSTM -Bilinear [10] | 98.84 ± 0.71 | 98.44 ± 1.38 | 98.85 ± 1.16 | 98.86 ± 0.98 | 0.081 | 0.32 | |

| GAT-TCN [6] | SDCAE [9] | 98.62 ± 1.00 | 98.22 ± 1.79 | 98.97 ± 1.28 | 98.64 ± 1.31 | 0.066 | 0.26 |

| CNN-LSTM -SAT [40] | 98.71 ± 0.97 | 98.31 ± 1.53 | 98.75 ± 1.22 | 98.73 ± 1.31 | 0.072 | 0.28 | |

| GTN [41] | 98.75 ± 1.32 | 98.35 ± 1.78 | 98.89 ± 0.96 | 98.77 ± 1.34 | 0.078 | 0.31 | |

| CNN-LSTM -Bilinear [10] | 98.78 ± 1.42 | 98.38 ± 1.41 | 98.82 ± 1.00 | 98.81 ± 1.29 | 0.074 | 0.30 | |

| Multidimensional Transformer & LSTM-GRU Fusion [8] | SDCAE [9] | 98.80 ± 1.10 | 98.42 ± 1.51 | 98.93 ± 1.16 | 98.84 ± 0.94 | 0.079 | 0.32 |

| CNN-LSTM -SAT [40] | 98.92 ± 1.30 | 98.54 ± 1.49 | 99.11 ± 0.89 | 98.96 ± 1.01 | 0.082 | 0.33 | |

| GTN [41] | 98.86 ± 0.78 | 98.48 ± 1.32 | 99.08 ± 0.80 | 98.90 ± 1.25 | 0.091 | 0.36 | |

| CNN-LSTM -Bilinear [10] | 98.91 ± 1.00 | 98.52 ± 1.49 | 99.03 ± 1.07 | 98.94 ± 0.93 | 0.086 | 0.34 | |

| Aver | 98.75 | 98.37 | 98.89 | 98.79 | 0.075 | 0.30 |

| Ablation | Seizure Prediction | Seizure Detection | Params (M) | Model Size (MB) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (%) | Sen (%) | FPR/h | Sig. (%) | Acc (%) | Sen (%) | Spe (%) | AUC (%) | |||

| Full KD | 99.54 ± 1.36 | 98.71 ± 1.50 | 0.01 ± 0.006 | 100% | 98.78 ± 1.31 | 98.36 ± 1.28 | 99.12 ± 1.40 | 98.72 ± 1.78 | 0.082 | 0.33 |

| No FiLM | 96.42 ± 2.60 | 96.73 ± 2.26 | 0.03 ± 0.014 | 100% | 96.52 ± 2.05 | 96.21 ± 1.90 | 97.02 ± 2.26 | 96.88 ± 2.19 | 0.079 | 0.31 |

| No Transformer | 97.27 ± 1.91 | 96.83 ± 2.09 | 0.04 ± 0.022 | 100% | 97.23 ± 2.01 | 97.30 ± 2.05 | 96.73 ± 2.44 | 96.79 ± 2.19 | 0.075 | 0.30 |

| No SFPM | 97.12 ± 2.13 | 98.03 ± 1.36 | 0.03 ± 0.014 | 100% | 98.55 ± 1.28 | 98.29 ± 1.60 | 97.98 ± 1.63 | 98.05 ± 1.32 | 0.081 | 0.31 |

| No TimeReg | 98.26 ± 1.39 | 98.11 ± 1.55 | 0.03 ± 0.014 | 100% | 97.69 ± 1.71 | 98.19 ± 1.41 | 97.77 ± 1.61 | 98.08 ± 1.75 | 0.081 | 0.31 |

| Only prediction teacher | 98.92 ± 1.29 | 98.30 ± 1.39 | 0.02 ± 0.014 | 100% | - | - | - | - | 0.082 | 0.33 |

| Only detection teacher | - | - | - | - | 98.45 ± 1.79 | 97.98 ± 1.84 | 98.95 ± 1.36 | 98.36 ± 1.71 | 0.082 | 0.33 |

| No KD | 95.78 ± 3.13 | 95.21 ± 3.41 | 0.07 ± 0.035 | 100% | 96.12 ± 2.78 | 95.58 ± 3.23 | 96.84 ± 2.29 | 96.10 ± 2.04 | 0.082 | 0.33 |

| Ablation | Seizure Prediction | Seizure Detection | Params (M) | Model Size (MB) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (%) | Sen (%) | FPR/h | Sig. (%) | Acc (%) | Sen (%) | Spe (%) | AUC (%) | |||

| Full KD | 98.97 ± 1.51 | 98.39 ± 2.01 | 0.02 ± 0.013 | 100% | 98.92 ± 1.69 | 98.54 ± 1.49 | 99.11 ± 1.57 | 98.96 ± 1.77 | 0.082 | 0.33 |

| No FiLM | 97.03 ± 2.51 | 96.95 ± 2.65 | 0.02 ± 0.010 | 100% | 96.87 ± 2.85 | 96.57 ± 3.30 | 97.13 ± 2.37 | 97.05 ± 2.73 | 0.079 | 0.31 |

| No Transformer | 97.54 ± 2.02 | 97.02 ± 2.60 | 0.02 ± 0.014 | 100% | 97.17 ± 2.45 | 96.93 ± 2.99 | 97.26 ± 1.85 | 96.88 ± 2.46 | 0.075 | 0.30 |

| No SFPM | 96.97 ± 2.94 | 97.11 ± 1.86 | 0.04 ± 0.019 | 100% | 98.21 ± 1.81 | 98.18 ± 2.58 | 98.27 ± 2.18 | 97.94 ± 2.46 | 0.081 | 0.31 |

| No TimeReg | 97.77 ± 2.53 | 97.61 ± 2.03 | 0.03 ± 0.024 | 100% | 97.05 ± 2.33 | 96.98 ± 2.86 | 97.24 ± 1.99 | 97.16 ± 1.87 | 0.081 | 0.31 |

| Only prediction teacher | 98.22 ± 2.35 | 98.30 ± 2.23 | 0.02 ± 0.008 | 100% | - | - | - | - | 0.082 | 0.33 |

| Only detection teacher | - | - | - | - | 98.40 ± 2.06 | 98.05 ± 2.16 | 98.83 ± 1.26 | 98.52 ± 1.56 | 0.082 | 0.33 |

| No KD | 95.89 ± 3.68 | 95.47 ± 3.54 | 0.07 ± 0.038 | 100% | 96.05 ± 3.03 | 95.42 ± 4.34 | 96.92 ± 2.82 | 96.18 ± 2.84 | 0.082 | 0.33 |

| Experiment | Seizure Prediction | Seizure Detection | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (%) | Sen (%) | FPR/h | Sig. (%) | Acc (%) | Sen (%) | Spe (%) | AUC (%) | |

| Exp. 1 | 93.81 ± 1.12 | 92.43 ± 1.65 | 0.10 ± 0.03 | 100% | 94.86 ± 0.87 | 93.52 ± 1.35 | 94.95 ± 0.93 | 94.67 ± 1.08 |

| Exp. 2 | 92.91 ± 1.33 | 91.88 ± 1.78 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 100% | 94.23 ± 0.93 | 93.15 ± 1.42 | 94.31 ± 0.94 | 94.17 ± 1.15 |

| Exp. 3 | 87.01 ± 8.51 | 87.92 ± 13.9 | 0.18 ± 0.09 | 100% | 91.06 ± 3.29 | 87.87 ± 7.14 | 91.35 ± 2.89 | 90.22 ± 5.19 |

| Exp. 4 | 83.82 ± 8.10 | 83.02 ± 14.5 | 0.20 ± 0.08 | 100% | 89.09 ± 3.54 | 86.42 ± 6.64 | 88.69 ± 3.21 | 87.63 ± 5.09 |

| Exp. 5 | 95.09 ± 1.07 | 93.92 ± 1.43 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 100% | 95.71 ± 0.77 | 94.65 ± 1.11 | 95.73 ± 0.87 | 95.42 ± 0.94 |

| Patient ID | Seizure Prediction | Seizure Detection | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (%) | Sen (%) | FPR/h | Acc (%) | Sen (%) | Spe (%) | AUC (%) | |

| PN00 | 88.43 | 100.00 | 0.14 | 92.13 | 85.34 | 92.49 | 91.19 |

| PN05 | 96.17 | 100.00 | 0.07 | 94.49 | 96.19 | 94.11 | 95.79 |

| PN06 | 85.32 | 80.00 | 0.21 | 89.21 | 82.51 | 90.14 | 88.46 |

| PN09 | 76.54 | 66.67 | 0.28 | 87.43 | 78.59 | 88.51 | 84.19 |

| PN10 | 92.13 | 90.00 | 0.12 | 93.61 | 92.39 | 93.79 | 93.49 |

| PN12 | 97.87 | 100.00 | 0.09 | 95.12 | 98.12 | 94.81 | 96.61 |

| PN13 | 74.31 | 66.67 | 0.31 | 86.29 | 81.49 | 86.79 | 82.14 |

| PN14 | 85.34 | 100.00 | 0.22 | 90.24 | 88.31 | 90.16 | 89.87 |

| Mean ± SD | 87.01 ± 8.51 | 87.92 ± 13.9 | 0.18 ± 0.09 | 91.06 ± 3.29 | 87.87 ± 7.14 | 91.35 ± 2.89 | 90.22 ± 5.19 |

| Patient ID | Seizure Prediction | Seizure Detection | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (%) | Sen (%) | FPR/h | Acc (%) | Sen (%) | Spe (%) | AUC (%) | |

| Pt1 | 94.49 | 100.00 | 0.06 | 94.19 | 96.49 | 94.11 | 95.79 |

| Pt2 | 76.41 | 66.67 | 0.24 | 86.41 | 83.11 | 86.59 | 84.49 |

| Pt3 | 86.19 | 83.33 | 0.18 | 89.49 | 88.19 | 89.79 | 89.19 |

| Pt5 | 93.11 | 100.00 | 0.11 | 92.81 | 93.59 | 92.51 | 93.39 |

| Pt8 | 69.51 | 60.00 | 0.34 | 83.59 | 76.39 | 84.19 | 80.11 |

| Pt9 | 92.29 | 100.00 | 0.12 | 91.21 | 92.81 | 91.11 | 91.49 |

| Pt10 | 83.59 | 83.33 | 0.19 | 88.09 | 86.49 | 88.39 | 87.19 |

| Pt13 | 82.19 | 80.00 | 0.18 | 89.39 | 87.19 | 89.59 | 88.79 |

| Pt14 | 95.39 | 100.00 | 0.08 | 93.49 | 94.81 | 93.19 | 94.41 |

| Pt16 | 73.79 | 70.00 | 0.32 | 82.79 | 73.49 | 83.89 | 78.49 |

| Pt17 | 74.21 | 66.67 | 0.28 | 85.19 | 80.41 | 85.49 | 83.19 |

| Pt18 | 84.49 | 83.33 | 0.22 | 87.49 | 86.11 | 87.79 | 86.59 |

| Pt19 | 91.39 | 100.00 | 0.11 | 91.81 | 92.49 | 91.61 | 92.19 |

| Pt20 | 80.11 | 80.00 | 0.24 | 86.89 | 84.21 | 87.11 | 85.39 |

| Pt21 | 77.49 | 75.00 | 0.26 | 84.49 | 80.31 | 85.19 | 82.49 |

| Pt23 | 86.43 | 80.00 | 0.19 | 88.11 | 86.59 | 88.49 | 88.89 |

| Mean ± SD | 83.82 ± 8.10 | 83.02 ± 14.5 | 0.20 ± 0.08 | 89.09 ± 3.54 | 86.42 ± 6.64 | 88.69 ± 3.21 | 87.63 ± 5.09 |

| Datasets | Seizure Prediction | Seizure Detection | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (%) | Sen (%) | FPR/h | Acc (%) | Sen (%) | Spe (%) | AUC (%) | |

| CHB-MIT | 99.54 ± 0.06 | 98.71 ± 0.12 | 0.01 ± 0.003 | 98.78 ± 0.08 | 98.36 ± 0.14 | 99.12 ± 0.06 | 98.72 ± 0.0.9 |

| Siena | 98.97 ± 0.08 | 98.39 ± 0.13 | 0.02 ± 0.004 | 98.92 ± 0.07 | 98.54 ± 0.12 | 99.11 ± 0.06 | 98.96 ± 0.08 |

| Prediction Methods | AUC (%) | Sen (%) | FPR/h | Sig. (%) | Params (M) | Model Size (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBAM-3D CNN-LSTM [39] | 98.52 ± 1.49 | 98.43 ± 1.94 | 0.02 ± 0.016 | 100% | 0.622 | 2.48 |

| Gatformer [7] | 99.10 ± 1.93 | 98.49 ± 1.95 | 0.01 ± 0.005 | 100% | 0.941 | 3.76 |

| GAT-TCN [6] | 98.67 ± 1.70 | 97.03 ± 2.46 | 0.03 ± 0.016 | 100% | 0.812 | 3.24 |

| Multidimensional Transformer & LSTM-GRU Fusion [8] | 99.64 ± 1.89 | 98.24 ± 1.91 | 0.03 ± 0.016 | 100% | 1.103 | 4.40 |

| RGF-Model | 99.54 ± 1.36 | 98.71 ± 1.50 | 0.01 ± 0.006 | 100% | 0.082 | 0.33 |

| Prediction Methods | AUC (%) | Sen (%) | FPR/h | Sig. (%) | Params (M) | Model Size (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBAM-3D CNN-LSTM [39] | 97.32 ± 2.75 | 97.18 ± 2.44 | 0.05 ± 0.029 | 100% | 0.622 | 2.48 |

| Gatformer [7] | 97.93 ± 2.52 | 97.69 ± 3.13 | 0.04 ± 0.023 | 100% | 0.941 | 3.76 |

| GAT-TCN [6] | 96.29 ± 3.07 | 95.88 ± 3.58 | 0.06 ± 0.024 | 100% | 0.812 | 3.24 |

| Multidimensional Transformer & LSTM-GRU Fusion [8] | 97.08 ± 2.47 | 97.22 ± 3.00 | 0.04 ± 0.021 | 100% | 1.103 | 4.40 |

| RGF-Model | 98.97 ± 1.51 | 98.39 ± 2.01 | 0.02 ± 0.013 | 100% | 0.082 | 0.33 |

| Detection Methods | Acc (%) | Sen (%) | Spe (%) | AUC (%) | Params (M) | Model Size (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDCAE [9] | 98.79 ± 0.91 | 98.72 ± 1.20 | 98.85 ± 0.90 | 98.80 ± 0.83 | 0.415 | 1.64 |

| CNN-LSTM -SAT [40] | 98.91 ± 1.05 | 98.72 ± 1.54 | 99.14 ± 1.40 | 99.07 ± 1.25 | 0.533 | 2.12 |

| GTN [41] | 98.43 ± 1.24 | 97.36 ± 2.15 | 99.23 ± 1.22 | 98.35 ± 0.84 | 0.781 | 3.12 |

| CNN-LSTM -Bilinear [10] | 98.84 ± 0.90 | 98.69 ± 1.10 | 97.97 ± 1.38 | 98.56 ± 1.26 | 0.724 | 2.88 |

| RGF-Model | 98.78 ± 1.18 | 98.36 ± 1.46 | 99.12 ± 0.67 | 98.72 ± 1.17 | 0.082 | 0.33 |

| Detection Methods | Acc (%) | Sen (%) | Spe (%) | AUC (%) | Params (M) | Model Size (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDCAE [9] | 97.89 ± 1.80 | 98.12 ± 1.20 | 98.17 ± 1.35 | 98.21 ± 1.42 | 0.415 | 1.64 |

| CNN-LSTM -SAT [40] | 98.15 ± 1.29 | 98.11 ± 1.46 | 98.23 ± 1.93 | 98.31 ± 1.28 | 0.533 | 2.12 |

| GTN [41] | 97.48 ± 2.00 | 97.36 ± 2.07 | 97.53 ± 2.71 | 97.65 ± 2.07 | 0.781 | 3.12 |

| CNN-LSTM -Bilinear [10] | 97.98 ± 1.44 | 98.14 ± 1.67 | 97.97 ± 1.59 | 98.25 ± 1.88 | 0.724 | 2.88 |

| RGF-Model | 98.92 ± 1.69 | 98.54 ± 1.49 | 99.11 ± 1.57 | 98.96 ± 1.77 | 0.082 | 0.33 |

| Dataset | Methods | AUC (%) | Sen (%) | FPR/h | Sig. (%) | Params (M) | Model Size (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHB-MIT | Cross-Subject KD [19] | 90.21 ± 3.86 | 95.25 ± 2.94 | 0.11 ± 0.022 | 100% | 0.537 | 2.03 |

| KDTT [51] | 85.36 ± 3.89 | 90.74 ± 3.87 | 0.1 ± 0.028 | 100% | 2.221 | 8.85 | |

| MoKD [18] | 88.17 ± 3.82 | 93.43 ± 2.62 | 0.12 ± 0.024 | 100% | 2.214 | 8.74 | |

| RGF-Model | 99.54 ± 1.36 | 98.71 ± 1.50 | 0.01 ± 0.006 | 100% | 0.082 | 0.33 | |

| Siena | Cross-Subject KD [19] | 89.91 ± 3.61 | 90.07 ± 3.67 | 0.17 ± 0.035 | 100% | 0.537 | 2.03 |

| KDTT [51] | 84.26 ± 4.55 | 85.77 ± 3.67 | 0.23 ± 0.045 | 87.50% | 2.221 | 8.85 | |

| MoKD [18] | 87.59 ± 4.28 | 88.17 ± 3.46 | 0.22 ± 0.040 | 75.00% | 2.214 | 8.74 | |

| RGF-Model | 98.97 ± 1.51 | 98.39 ± 2.01 | 0.02 ± 0.013 | 100% | 0.082 | 0.33 |

| Dataset | Methods | Acc (%) | Sen (%) | Spe (%) | AUC (%) | Params (M) | Model Size (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHB-MIT | M2SKD [18] | 93.56 ± 2.33 | 92.51 ± 1.68 | 94.26 ± 1.90 | 95.74 ± 1.75 | 2.252 | 8.77 |

| KD-Channel- Pruning [52] | 91.05 ± 2.82 | 90.41 ± 2.89 | 91.74 ± 2.56 | 92.52 ± 1.97 | 0.003 | 0.01 | |

| KDTL [53] | 94.62 ± 1.88 | 93.35 ± 1.80 | 95.40 ± 1.58 | 94.71 ± 2.17 | 4.235 | 16.85 | |

| RGF-Model | 98.78 ± 1.18 | 98.36 ± 1.46 | 99.12 ± 0.67 | 98.72 ± 1.17 | 0.082 | 0.33 | |

| Siena | M2SKD [18] | 92.31 ± 1.81 | 91.97 ± 3.23 | 92.58 ± 2.42 | 92.22 ± 2.48 | 2.252 | 8.77 |

| KD-Channel- Pruning [52] | 90.87 ± 3.07 | 90.11 ± 3.43 | 90.24 ± 3.04 | 90.15 ± 3.47 | 0.003 | 0.01 | |

| KDTL [53] | 93.84 ± 2.20 | 93.16 ± 2.36 | 93.88 ± 1.97 | 93.57 ± 2.02 | 4.235 | 16.85 | |

| RGF-Model | 98.92 ± 1.69 | 98.54 ± 1.49 | 99.11 ± 1.57 | 98.96 ± 1.77 | 0.082 | 0.33 |

| Role | Methods | Params (M) | Model Size (MB) | FLOPs per 2-s Window (M) | Peak RAM (MB) | Latency per 2-s window (ms) ± SD | Real- Time Factor | Energy per Inference (mJ, Estimated) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prediction | student | RGF-Model | 0.082 | 0.33 | 35 | 70 | 11.8 ± 0.9 | 0.0059 | 1.4 |

| Teacher A | Multidimensional Transformer & LSTM-GRU Fusion [8] | 1.103 | 4.40 | 210 | 180 | 28.6 ± 2.0 | 0.0143 | 8.4 | |

| Teacher B | Gatformer [7] | 0.941 | 3.76 | 240 | 200 | 32.4 ± 2.3 | 0.0162 | 9.6 | |

| Representative SOTA | CBAM-3D CNN-LSTM [39] | 0.622 | 2.48 | 320 | 220 | 44.8 ± 3.1 | 0.0224 | 12.8 | |

| Representative SOTA | GAT-TCN [6] | 0.812 | 3.24 | 260 | 190 | 36.9 ± 2.6 | 0.0185 | 10.4 | |

| Detection | student | RGF-Model | 0.082 | 0.33 | 35 | 70 | 11.7 ± 0.8 | 0.0058 | 1.4 |

| Teacher A | CNN-LSTM-SAT [40] | 0.533 | 2.12 | 190 | 170 | 26.1 ± 1.8 | 0.0131 | 7.6 | |

| Teacher B | SDCAE [9] | 0.415 | 1.64 | 160 | 150 | 22.4 ± 1.6 | 0.0112 | 6.4 | |

| Representative SOTA | GTN [41] | 0.781 | 3.12 | 380 | 230 | 53.6 ± 3.7 | 0.0268 | 15.2 | |

| Representative SOTA | CNN-LSTM -Bilinear [10] | 0.724 | 2.88 | 300 | 210 | 41.3 ± 2.9 | 0.0207 | 12.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cao, W.; Li, Q.; Zhang, A.; Wang, T. Efficient and Accurate Epilepsy Seizure Prediction and Detection Based on Multi-Teacher Knowledge Distillation RGF-Model. Brain Sci. 2026, 16, 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010083

Cao W, Li Q, Zhang A, Wang T. Efficient and Accurate Epilepsy Seizure Prediction and Detection Based on Multi-Teacher Knowledge Distillation RGF-Model. Brain Sciences. 2026; 16(1):83. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010083

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Wei, Qi Li, Anyuan Zhang, and Tianze Wang. 2026. "Efficient and Accurate Epilepsy Seizure Prediction and Detection Based on Multi-Teacher Knowledge Distillation RGF-Model" Brain Sciences 16, no. 1: 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010083

APA StyleCao, W., Li, Q., Zhang, A., & Wang, T. (2026). Efficient and Accurate Epilepsy Seizure Prediction and Detection Based on Multi-Teacher Knowledge Distillation RGF-Model. Brain Sciences, 16(1), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010083