A GABAergic Projection from the Zona Incerta to the Rostral Ventromedial Medulla Modulates Descending Control of Neuropathic Pain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. CCI Model

2.3. Viruses and Chemicals

2.4. Stereotaxic Surgery

2.5. Immunohistochemistry and Imaging

2.6. In Vivo Optogenetic Manipulation

2.7. Behavioral Tests

2.7.1. Von Frey Test

2.7.2. Open Field Test

2.7.3. Elevated Plus Maze

2.8. Quantification and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

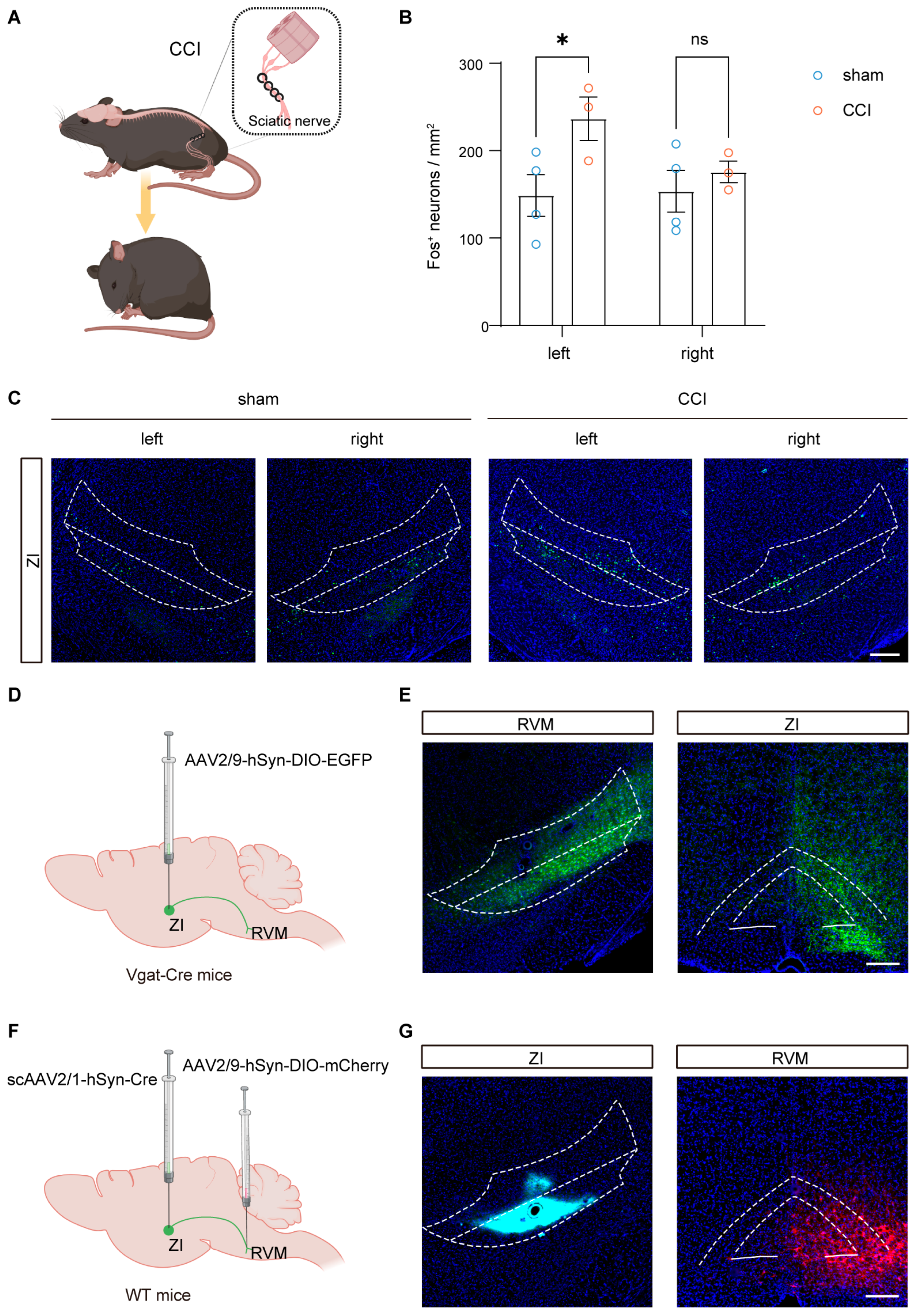

3.1. Ipsilateral ZI Is Activated by Nerve Injury and Innervates the RVM

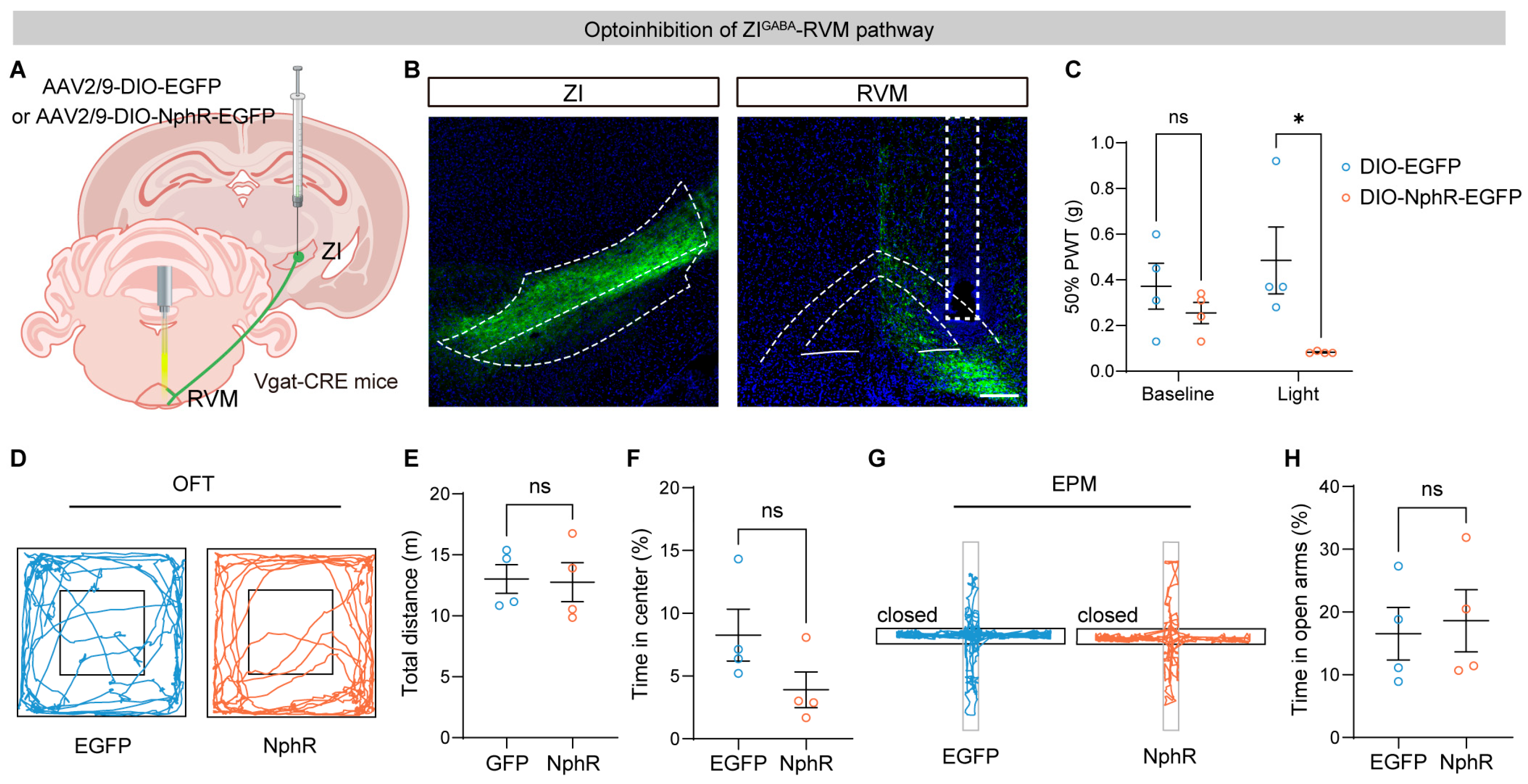

3.2. Optogenetic Inhibition of the ZI–RVM Pathway Induces Mechanical Allodynia

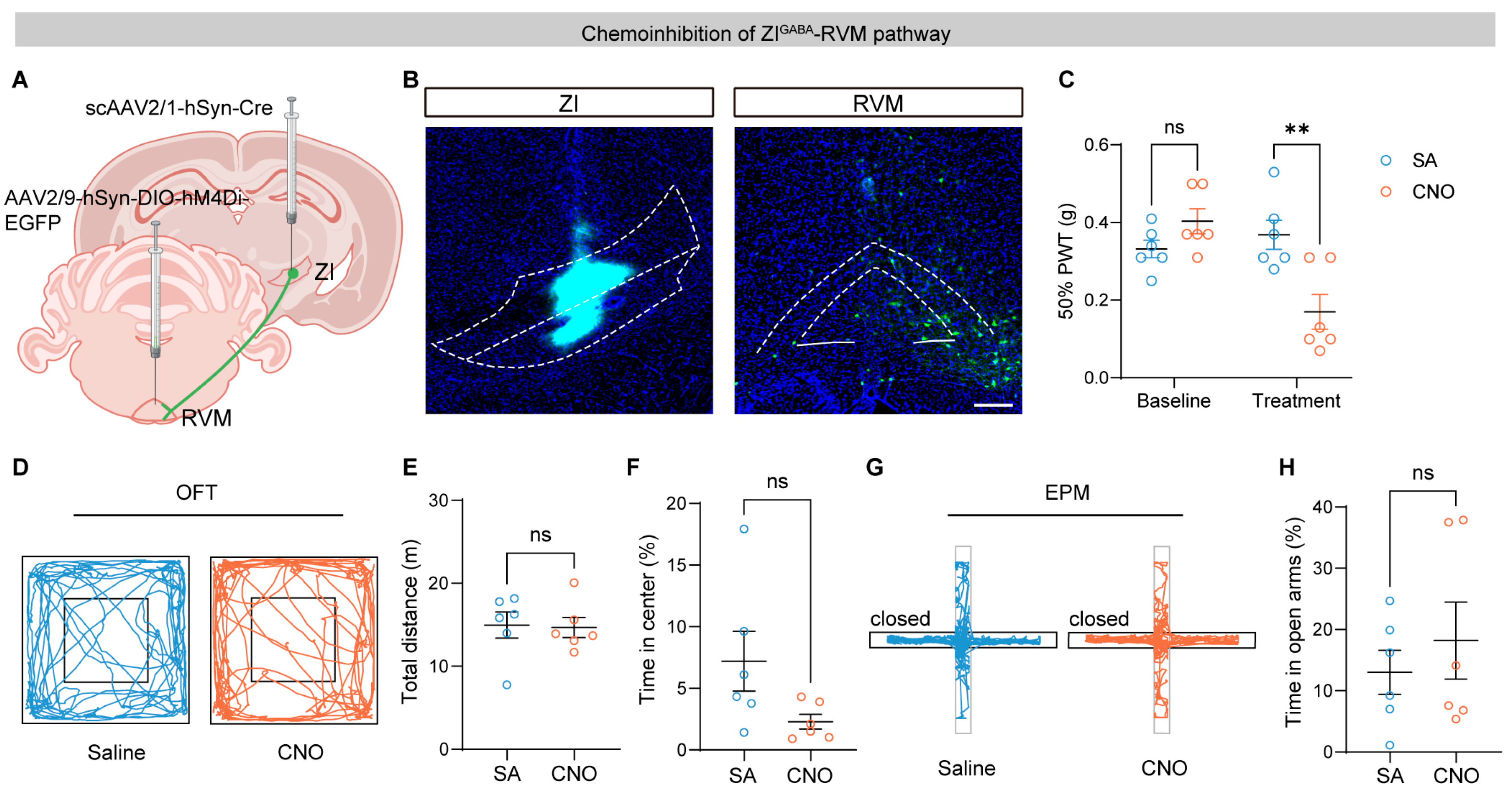

3.3. Chemogenetic Inhibition of ZI–RVM Neurons Promotes Pain Hypersensitivity

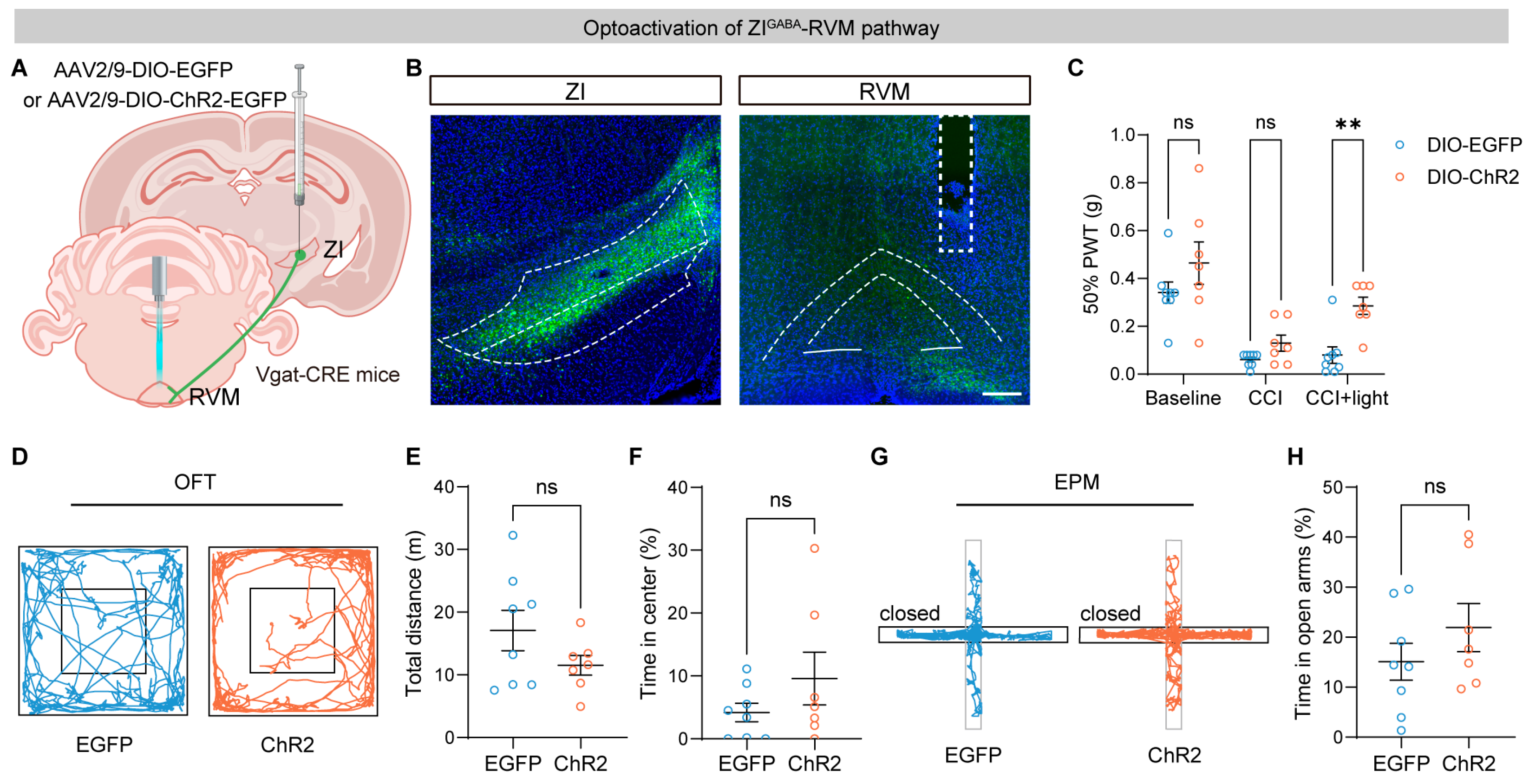

3.4. Optogenetic Activation of the ZI–RVM Pathway Alleviates Neuropathic Pain

3.5. Chemogenetic Activation of ZI–RVM Neurons Attenuates Pain Hypersensitivity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RVM | Rostral ventromedial medulla |

| ZI | Zona incerta |

| CCI | Chronic constriction injury |

| PAG | Periaqueductal gray |

| OFT | Open field test |

| EPM | Elevated plus maze |

| PWT | Paw withdrawal threshold |

References

- Wagner, I.C.; Rütgen, M.; Hummer, A.; Windischberger, C.; Lamm, C. Placebo-induced pain reduction is associated with negative coupling between brain networks at rest. Neuroimage 2020, 219, 117024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Preter, C.C.; Heinricher, M.M. The ‘in’s and out’s’ of descending pain modulation from the rostral ventromedial medulla. Trends Neurosci. 2024, 47, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoegh, M.; Bannister, K. Pain Science in Practice (Part 6): How Does Descending Modulation of Pain Work? J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2024, 54, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, M. Descending facilitation. Mol. Pain 2017, 13, 1744806917699212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.-S.; Chiang, C.Y.; Dostrovsky, J.O.; Yao, D.; Sessle, B.J. Responses of neurons in rostral ventromedial medulla to nociceptive stimulation of craniofacial region and tail in rats. Brain Res. 2021, 1767, 147539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatt, M.P.; Zhang, M.-D.; Kupari, J.; Altınkök, M.; Yang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Svenningsson, P.; Ernfors, P. Morphine-responsive neurons that regulate mechanical antinociception. Science 2024, 385, eado6593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeder, Z.; Chen, Q.; Davis, S.; Carlson, J.D.; Tupone, D.; Heinricher, M.M. Parabrachial complex links pain transmission to descending pain modulation. Pain 2016, 157, 2697–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basbaum, A.I.; Bautista, D.M.; Scherrer, G.; Julius, D. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pain. Cell 2009, 139, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, E.; Grajales-Reyes, J.G.; Gereau, R.W.; Ross, S.E. Cell type-specific dissection of sensory pathways involved in descending modulation. Trends Neurosci. 2023, 46, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, D.; Labrakakis, C. Multiple Posterior Insula Projections to the Brainstem Descending Pain Modulatory System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Yin, P.; Chen, J.; Jin, S.; Liu, J.; Luo, F. CaMKIIα may modulate fentanyl-induced hyperalgesia via a CeLC-PAG-RVM-spinal cord descending facilitative pain pathway in rats. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Dong, P.; He, C.; Feng, X.-Y.; Huang, Y.; Yang, W.-W.; Gao, H.-J.; Shen, X.-F.; Lin, S.; Cao, S.-X.; et al. Incerta-thalamic Circuit Controls Nocifensive Behavior via Cannabinoid Type 1 Receptors. Neuron 2020, 107, 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chou, X.-L.; Zhang, L.I.; Tao, H.W. Zona Incerta: An Integrative Node for Global Behavioral Modulation. Trends Neurosci. 2019, 43, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oertel, W.H.; Tappaz, M.L.; Berod, A.; Mugnaini, E. Two-color immunohistochemistry for dopamine and GABA neurons in rat substantia nigra and zona incerta. Brain Res. Bull. 1982, 9, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.-L.; Chen, S.-H.; Li, J.-N.; Zhao, L.-J.; Wu, X.-M.; Hong, J.; Zhu, K.-H.; Sun, H.-X.; Shi, S.-J.; Mao, E.; et al. Projections from the Rostral Zona Incerta to the Thalamic Paraventricular Nucleus Mediate Nociceptive Neurotransmission in Mice. Metabolites 2023, 13, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Yu, L.; Jiang, B.-C.; Wang, J.; Guo, X.; Huang, Y.; Ren, J.; Sun, N.; Gao, D.S.; Ding, H.; et al. ZNF382 controls mouse neuropathic pain via silencer-based epigenetic inhibition of Cxcl13 in DRG neurons. J. Exp. Med. 2021, 218, e20210920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, C.; Chen, M.; Qian, K.; Lv, X.; Wang, H.; Jiang, L.; Yu, L.; Zhuo, M.; Qiu, S. The anterior insular cortex unilaterally controls feeding in response to aversive visceral stimuli in mice. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Li, M.; Zhao, R.; Sun, L.; Yang, G. A sleep-active basalocortical pathway crucial for generation and maintenance of chronic pain. Nat. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, W.J. Efficient analysis of experimental observations. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1980, 20, 441–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- François, A.; Low, S.A.; Sypek, E.I.; Christensen, A.J.; Sotoudeh, C.; Beier, K.T.; Ramakrishnan, C.; Ritola, K.D.; Sharif-Naeini, R.; Deisseroth, K.; et al. A Brainstem-Spinal Cord Inhibitory Circuit for Mechanical Pain Modulation by GABA and Enkephalins. Neuron 2017, 93, 822–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.-H.; Hou, X.-Y.; Liu, H.-Z.; Zhou, Z.-R.; Lv, S.-S.; Yi, L.-X.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.-Q. Descending projection neurons in the primary sensorimotor cortex regulate neuropathic pain and locomotion in mice. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.-D.; Chen, Z.; Xiang, X.; Hu, M.; Xie, H.; Jia, X.; Cai, F.; Cui, Y.; Chen, Z.; Qian, L.; et al. Zona incerta GABAergic neurons integrate prey-related sensory signals and induce an appetitive drive to promote hunting. Nat. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 921–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, H.C.; Park, Y.S. Reduced GABAergic neuronal activity in zona incerta causes neuropathic pain in a rat sciatic nerve chronic constriction injury model. J. Pain Res. 2017, 10, 1125–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Qian, J.; Shi, Y.; Liu, Y.; Qu, L.; Jia, W.; Xie, J.; Shi, L. Activation of the zona incerta GABAergic circuit for the treatment of pain hypersensitivity in Parkinson’s disease mice model. J. Headache Pain 2025, 26, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-C.; Zhang, F.-C.; Li, D.; Weng, R.-X.; Yu, Y.; Gao, R.; Xu, G.-Y. Distinct circuits and molecular targets of the paraventricular hypothalamus decode visceral and somatic pain. Neuron 2024, 112, 3734–3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, J.; Ren, P.; Tian, B.; Li, J.; Qi, C.; Huang, Q.; Ren, K.; Hu, E.; Mao, H.; Zang, Y.; et al. Ventral zona incerta parvalbumin neurons modulate sensory-induced and stress-induced self-grooming via input-dependent mechanisms in mice. iScience 2024, 27, 110165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillu, D.V.; Gebhart, G.F.; Sluka, K.A. Descending facilitatory pathways from the RVM initiate and maintain bilateral hyperalgesia after muscle insult. Pain 2007, 136, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, X.; Xin, W.-J.; He, S.; Deng, J.; Ruan, X. Somatostatin Neurons from Periaqueductal Gray to Medulla Facilitate Neuropathic Pain in Male Mice. J. Pain 2023, 24, 1020–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, B.K.; Vaughan, C.W. Descending modulation of pain: The GABA disinhibition hypothesis of analgesia. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2014, 29, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobaldini, G.; Sardi, N.F.; Guilhen, V.A.; Fischer, L. Pain Inhibits Pain: An Ascending-Descending Pain Modulation Pathway Linking Mesolimbic and Classical Descending Mechanisms. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 56, 1000–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, V.; Gregory, R.; Davies, W.-E.; Harrison, L.; Moran, R.; Pickering, A.E.; Brooks, J.C.W. Parallel cortical-brainstem pathways to attentional analgesia. Neuroimage 2020, 226, 117548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seijo-Fernandez, F.; Saiz, A.; Santamarta, E.; Nader, L.; Alvarez-Vega, M.A.; Lozano, B.; Seijo, E.; Barcia, J.A. Long-Term Results of Deep Brain Stimulation of the Mamillotegmental Fasciculus in Chronic Cluster Headache. Stereotact. Funct. Neurosurg. 2018, 96, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulbaki, A.; Wöhrle, J.C.; Blahak, C.; Weigel, R.; Kollewe, K.; Capelle, H.H.; Bäzner, H.; Krauss, J.K. Somatosensory evoked potentials recorded from DBS electrodes: The origin of subcortical N18. J. Neural Transm. 2024, 131, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.W.; Harper, D.E.; Askari, A.; Willsey, M.S.; Vu, P.P.; Schrepf, A.D.; Harte, S.E.; Patil, P.G. Stimulation of zona incerta selectively modulates pain in humans. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-H.; Wu, C.; Lian, Y.-N.; Cao, X.-W.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Dong, J.-J.; Wu, Q.; Liu, L.; Sun, L.; Chen, W.; et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing uncovers the cell type-dependent transcriptomic changes in the retrosplenial cortex after peripheral nerve injury. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 113551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zou, L.; Ding, H.; Hu, Y.; Wen, Z.; Yu, L.; Yan, M. A GABAergic Projection from the Zona Incerta to the Rostral Ventromedial Medulla Modulates Descending Control of Neuropathic Pain. Brain Sci. 2026, 16, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010072

Zou L, Ding H, Hu Y, Wen Z, Yu L, Yan M. A GABAergic Projection from the Zona Incerta to the Rostral Ventromedial Medulla Modulates Descending Control of Neuropathic Pain. Brain Sciences. 2026; 16(1):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010072

Chicago/Turabian StyleZou, Lijing, Hao Ding, Yujiao Hu, Zhuo Wen, Lina Yu, and Min Yan. 2026. "A GABAergic Projection from the Zona Incerta to the Rostral Ventromedial Medulla Modulates Descending Control of Neuropathic Pain" Brain Sciences 16, no. 1: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010072

APA StyleZou, L., Ding, H., Hu, Y., Wen, Z., Yu, L., & Yan, M. (2026). A GABAergic Projection from the Zona Incerta to the Rostral Ventromedial Medulla Modulates Descending Control of Neuropathic Pain. Brain Sciences, 16(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010072