Exploring Bidirectional Associations Between Voice Acoustics and Objective Motor Metrics in Parkinson’s Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

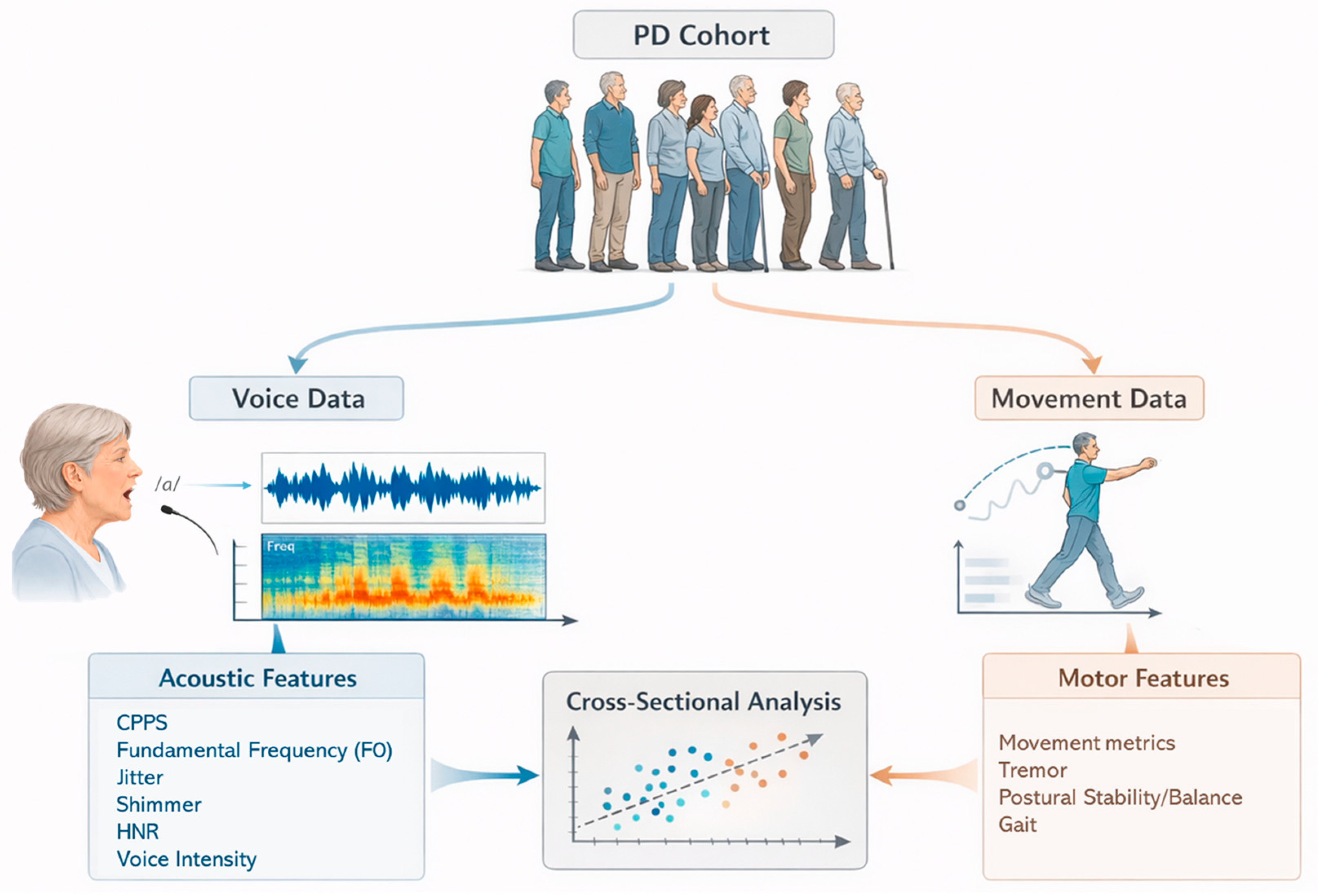

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Part III (UPDRS-III)

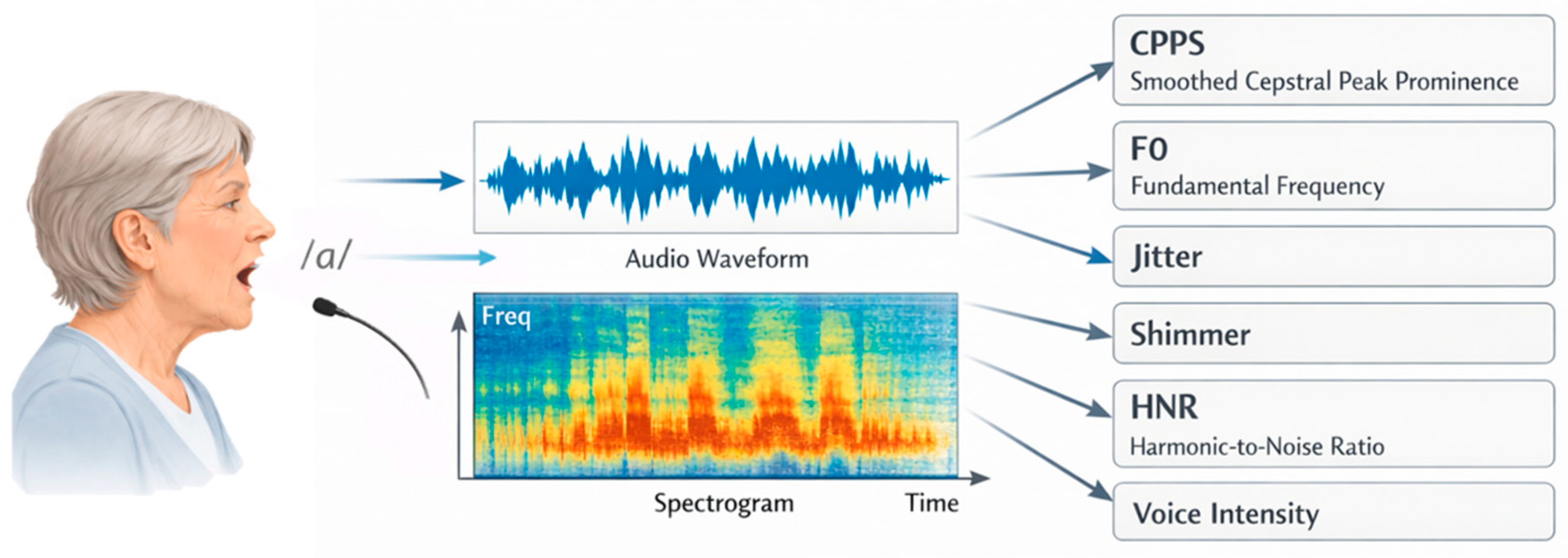

2.4. Vocal Recording and Measures

2.5. Integrated Motion Analysis Suite (IMAS)

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants Characteristics

3.2. Associations Between Voice and Motor Related Variables

3.2.1. Associations with Voice Outcomes

3.2.2. Associations with Motor Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Acronym | Full Term |

| CPPS | Cepstral Peak Prominence Smoothed |

| dB | Decibels |

| F0 | Fundamental Frequency |

| HNR | Harmonic-to-Noise Ratio |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| IMAS | Integrated Motion Analysis Suite |

| PD | Parkinson’s Disease |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| UPDRS-III | Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Part III |

| EC | Eyes Closed |

| EO | Eyes Open |

References

- Jankovic, J.; Tan, E.K. Parkinson’s disease: Etiopathogenesis and treatment. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2020, 91, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausdorff, J.M. Gait dynamics in Parkinson’s disease: Common and distinct behavior among stride length, gait variability, and fractal-like scaling. Chaos 2009, 19, 026113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espay, A.J.; Beaton, D.E.; Morgante, F.; Gunraj, C.A.; Lang, A.E.; Chen, R. Impairments of speed and amplitude of movement in Parkinson’s disease: A pilot study. Mov. Disord. 2009, 24, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Y.; Herman, T.; Brozgol, M.; Giladi, N.; Mirelman, A.; Hausdorff, J.M. SPARC: A new approach to quantifying gait smoothness in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2018, 15, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloem, B.R.; Okun, M.S.; Klein, C. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 2021, 397, 2284–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, K.R.; Healy, D.G.; Schapira, A.H.; National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: Diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skodda, S.; Gronheit, W.; Schlegel, U. Impairment of vowel articulation as a possible marker of disease progression in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e32132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skodda, S.; Visser, W.; Schlegel, U. Vowel articulation in Parkinson’s disease. J. Voice 2011, 25, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusz, J.; Tykalova, T.; Novotny, M.; Ruzicka, E.; Dusek, P. Distinct patterns of speech disorder in early-onset and late-onset de-novo Parkinson’s disease. npj Parkinsons Dis. 2021, 7, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalling, E.; Johansson, K.; Hartelius, L. Speech and Communication Changes Reported by People with Parkinson’s Disease. Folia Phoniatr. Logop. 2017, 69, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramig, L.O.; Fox, C.; Sapir, S. Parkinson’s disease: Speech and voice disorders and their treatment with the Lee Silverman Voice Treatment. Semin. Speech Lang. 2004, 25, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusz, J.; Cmejla, R.; Tykalova, T.; Ruzickova, H.; Klempir, J.; Majerova, V.; Picmausova, J.; Roth, J.; Ruzicka, E. Imprecise vowel articulation as a potential early marker of Parkinson’s disease: Effect of speaking task. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2013, 134, 2171–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atalar, M.S.; Oguz, O.; Genc, G. Hypokinetic Dysarthria in Parkinson’s Disease: A Narrative Review. Sisli Etfal Hastan. Tip. Bul. 2023, 57, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, A.K.; Bradshaw, J.L.; Iansek, R.; Alfredson, R. Speech volume regulation in Parkinson’s disease: Effects of implicit cues and explicit instructions. Neuropsychologia 1999, 37, 1453–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapir, S.; Ramig, L.; Fox, C. Speech and swallowing disorders in Parkinson disease. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2008, 16, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox Cynthia, M.; Ramig Lorraine, O. Vocal Sound Pressure Level and Self-Perception of Speech and Voice in Men and Women With Idiopathic Parkinson Disease. Am. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 1997, 6, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, H.; Hertrich, I. The contribution of the cerebellum to speech processing. J. Neurolinguistics 2000, 13, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Horwitz, B. Laryngeal motor cortex and control of speech in humans. Neuroscientist 2011, 17, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stadio, A.; Sossamon, J.; De Luca, P.; Indovina, I.; Motta, G.; Ralli, M.; Brenner, M.J.; Frohman, E.M.; Plant, G.T. “Do You Hear What I Hear?” Speech and Voice Alterations in Hearing Loss: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor-Cutiva, L.C.; Ramani, S.A.; Walden, P.R.; Hunter, E.J. Screening of Voice Pathologies: Identifying the Predictive Value of Voice Acoustic Parameters for Common Voice Pathologies. J. Voice 2023, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silbergleit, A.K.; LeWitt, P.A.; Peterson, E.L.; Gardner, G.M. Quantitative Analysis of Voice in Parkinson Disease Compared to Motor Performance: A Pilot Study. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2015, 5, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dipietro, L.; Eden, U.; Elkin-Frankston, S.; El-Hagrassy, M.M.; Camsari, D.D.; Ramos-Estebanez, C.; Fregni, F.; Wagner, T. Integrating Big Data, Artificial Intelligence, and motion analysis for emerging precision medicine applications in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berardelli, A.; Rothwell, J.C.; Thompson, P.D.; Hallett, M. Pathophysiology of bradykinesia in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2001, 124, 2131–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzoni, P.; Shabbott, B.; Cortes, J.C. Motor control abnormalities in Parkinson’s disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a009282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Vogel, A.P.; Gharahkhani, P.; Renteria, M.E. Speech and language biomarkers for Parkinson’s disease prediction, early diagnosis and progression. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2025, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.K.; Bradshaw, J.L.; Iansek, R. For better or worse: The effect of levodopa on speech in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skodda, S.; Visser, W.; Schlegel, U. Short- and long-term dopaminergic effects on dysarthria in early Parkinson’s disease. J. Neural. Transm. 2010, 117, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convey, R.B.; Laukkanen, A.M.; Ylinen, S.; Penttila, N. Analysis of Voice Changes in Early-Stage Parkinson’s Disease with AVQI and ABI: A Follow-up Study. J. Voice 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midi, I.; Dogan, M.; Koseoglu, M.; Can, G.; Sehitoglu, M.A.; Gunal, D.I. Voice abnormalities and their relation with motor dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2008, 117, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skodda, S.; Visser, W.; Schlegel, U. Gender-related patterns of dysprosody in Parkinson disease and correlation between speech variables and motor symptoms. J. Voice 2011, 25, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goberman, A.M. Correlation between acoustic speech characteristics and non-speech motor performance in Parkinson Disease. Med. Sci. Monit. 2005, 11, CR109–CR116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dias, A.E.; Barbosa, M.T.; Limongi, J.C.; Barbosa, E.R. Speech disorders did not correlate with age at onset of Parkinson’s disease. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2016, 74, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianlorenco, A.C.; Costa, V.; Fabris-Moraes, W.; Teixeira, P.E.P.; Gonzalez, P.; Pacheco-Barrios, K.; Ramos-Estebanez, C.; Di Stadio, A.; El-Hagrassy, M.M.; Camsari, D.D.; et al. Associations of Voice Metrics with Postural Function in Parkinson’s Disease. Life 2024, 15, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordio, S.; Bernitsas, E.; Meneghello, F.; Palmer, K.; Stabile, M.R.; Dipietro, L.; Di Stadio, A. Expiratory and phonation times as measures of disease severity in patients with Multiple Sclerosis. A case-control study. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2018, 23, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movement Disorder Society Task Force on Rating Scales for Parkinson’s, D. The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS): Status and recommendations. Mov. Disord. 2003, 18, 738–750. [CrossRef]

- Sauder, C.; Bretl, M.; Eadie, T. Predicting Voice Disorder Status From Smoothed Measures of Cepstral Peak Prominence Using Praat and Analysis of Dysphonia in Speech and Voice (ADSV). J. Voice 2017, 31, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heman-Ackah, Y.D.; Heuer, R.J.; Michael, D.D.; Ostrowski, R.; Horman, M.; Baroody, M.M.; Hillenbrand, J.; Sataloff, R.T. Cepstral peak prominence: A more reliable measure of dysphonia. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2003, 112, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hippargekar, P.; Bhise, S.; Kothule, S.; Shelke, S. Acoustic Voice Analysis of Normal and Pathological Voices in Indian Population Using Praat Software. Indian. J. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2022, 74, 5069–5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Hou, Q.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, Z.; Gong, S. Acoustic parameters for the evaluation of voice quality in patients with voice disorders. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2020, 10, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.J.; Zhang, Y.; MacCallum, J.; Sprecher, A.; Zhou, L. Objective acoustic analysis of pathological voices from patients with vocal nodules and polyps. Folia Phoniatr. Logop. 2009, 61, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryn, Y.; Weenink, D. Objective dysphonia measures in the program Praat: Smoothed cepstral peak prominence and acoustic voice quality index. J. Voice 2015, 29, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horii, Y. Some statistical characteristics of voice fundamental frequency. J. Speech Hear. Res. 1975, 18, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, A.P.; Maruff, P.; Snyder, P.J.; Mundt, J.C. Standardization of pitch-range settings in voice acoustic analysis. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, R.R.; Awan, S.N.; Barkmeier-Kraemer, J.; Courey, M.; Deliyski, D.; Eadie, T.; Paul, D.; Švec, J.G.; Hillman, R. Recommended Protocols for Instrumental Assessment of Voice: American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Expert Panel to Develop a Protocol for Instrumental Assessment of Vocal Function. Am. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2018, 27, 887–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipietro, L.; Gonzalez-Mego, P.; Ramos-Estebanez, C.; Zukowski, L.H.; Mikkilineni, R.; Rushmore, R.J.; Wagner, T. The evolution of Big Data in neuroscience and neurology. J. Big Data 2023, 10, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, A.; Aron, E.N. Statistics for Psychology; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Allyn and Bacon: Needham Heights, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoads, C.H. Problems with Tests of the Missingness Mechanism in Quantitative Policy Studies. Stat. Politics Policy 2012, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymans, M.W.; Twisk, J.W.R. Handling missing data in clinical research. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2022, 151, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunimatsu, J.; Suzuki, T.W.; Ohmae, S.; Tanaka, M. Different contributions of preparatory activity in the basal ganglia and cerebellum for self-timing. eLife 2018, 7, e35676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Hallett, M. The cerebellum in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2013, 136, 696–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, J.; Onate, M.; Khatami, L.; Vera, J.; Nadim, F.; Khodakhah, K. Cerebellar Contributions to the Basal Ganglia Influence Motor Coordination, Reward Processing, and Movement Vigor. J. Neurosci. 2022, 42, 8406–8415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manes, J.L.; Bullock, L.; Meier, A.M.; Turner, R.S.; Richardson, R.M.; Guenther, F.H. A neurocomputational view of the effects of Parkinson’s disease on speech production. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1383714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, K.Z.; Brabo, N.C.; Minett, T.S.C. Sensorimotor speech disorders in Parkinson’s disease: Programming and execution deficits. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2016, 10, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.; Ngan, E.; Liotti, M. A larynx area in the human motor cortex. Cereb. Cortex 2008, 18, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenyon, K.H.; Boonstra, F.; Noffs, G.; Morgan, A.T.; Vogel, A.P.; Kolbe, S.; Van Der Walt, A. The characteristics and reproducibility of motor speech functional neuroimaging in healthy controls. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1382102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grahn, J.A.; Brett, M. Impairment of beat-based rhythm discrimination in Parkinson’s disease. Cortex 2009, 45, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveri, M.C. Contribution of the Cerebellum and the Basal Ganglia to Language Production: Speech, Word Fluency, and Sentence Construction-Evidence from Pathology. Cerebellum 2021, 20, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Jiang, H.Y.; Zhang, C.X.; Jin, Z.H.; Gao, L.; Wang, R.D.; Fang, J.P.; Su, Y.; Xi, J.N.; Fang, B.Y. The Role of the Diaphragm in Postural Stability and Visceral Function in Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 785020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, A.; Lau, K.K.; Thyagarajan, D. Voice changes in Parkinson’s disease: What are they telling us? J. Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 72, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varas-Diaz, G.; Kannan, L.; Bhatt, T. Effect of Mental Fatigue on Postural Sway in Healthy Older Adults and Stroke Populations. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliabue, M.; Ferrigno, G.; Horak, F. Effects of Parkinson’s disease on proprioceptive control of posture and reaching while standing. Neuroscience 2009, 158, 1206–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, M.; Horak, F.B.; Zampieri, C.; Carlson-Kuhta, P.; Nutt, J.G.; Chiari, L. Trunk accelerometry reveals postural instability in untreated Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2011, 17, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancini, M.; Carlson-Kuhta, P.; Zampieri, C.; Nutt, J.G.; Chiari, L.; Horak, F.B. Postural sway as a marker of progression in Parkinson’s disease: A pilot longitudinal study. Gait Posture 2012, 36, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeem, I.; Ditta, A.; Mazhar, T.; Anwar, M.; Saeed, M.M.; Hamam, H. Voice biomarkers as prognostic indicators for Parkinson’s disease using machine learning techniques. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusz, J.; Hlavnicka, J.; Tykalova, T.; Buskova, J.; Ulmanova, O.; Ruzicka, E.; Sonka, K. Quantitative assessment of motor speech abnormalities in idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder. Sleep. Med. 2016, 19, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbruzzese, G.; Marchese, R.; Avanzino, L.; Pelosin, E. Rehabilitation for Parkinson’s disease: Current outlook and future challenges. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2016, 22, S60–S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaulding, S.J.; Barber, B.; Colby, M.; Cormack, B.; Mick, T.; Jenkins, M.E. Cueing and gait improvement among people with Parkinson’s disease: A meta-analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013, 94, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, G.; Wentzel-Larsen, T.; Aarsland, D.; Larsen, J.P. Progression of motor impairment and disability in Parkinson disease: A population-based study. Neurology 2005, 65, 1436–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, C.R. Epidemiology, diagnosis and differential diagnosis in Parkinson’s disease tremor. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2012, 18, S90–S92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haaxma, C.A.; Bloem, B.R.; Borm, G.F.; Oyen, W.J.; Leenders, K.L.; Eshuis, S.; Booij, J.; Dluzen, D.E.; Horstink, M.W. Gender differences in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2007, 78, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| UPDRS-III-Derived Variables (Domains) | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Speech | 1.2 ± 0.9 |

| Facial expression | 1.2 ± 1.0 |

| Rigidity | 3.2 ± 2.0 |

| Finger tapping | 1.8 ± 1.2 |

| Hand movements | 1.9 ± 1.5 |

| Alternating movements | 1.8 ± 1.5 |

| Leg agility | 1.8 ± 1.7 |

| Posture | 1.1 ± 0.8 |

| Gait | 0.8 ± 0.7 |

| Postural stability | 0.7 ± 0.6 |

| Bradykinesia | 1.5 ± 1.0 |

| Arising from chair * | 0 (0) |

| Kinetic Tremor * | 2.0 (1–2) |

| Rest Tremor * | 1.0 (0–3) |

| Variable | Obs | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPPS | 12 | 11.75 | 2.86 | 5.06 | 15.75 |

| Median F0 | 10 | 152.54 | 31.21 | 97.27 | 203.49 |

| Jitter | 10 | 0.67 | 0.37 | 0.27 | 1.53 |

| Voice Shimmer | 10 | 6.56 | 2.12 | 2.75 | 10.02 |

| HNR | 10 | 21.11 | 5.94 | 10.36 | 32.75 |

| SD F0 * | 10 | 4.6 | 3.48 | 2.04 | 19.96 |

| Voice Intensity * | 12 | 48.1 | 7.47 | 32.49 | 68.23 |

| Voice Variables | Meaning/Interpretation |

| Voice_HNR | Ratio of harmonic (periodic) to noise (aperiodic) energy in the voice. Higher values = clearer, less breathy/hoarse voice. |

| CPPS | Degree of harmonic organization in the voice signal. Higher values = improved voice quality (greater cepstral prominence). |

| Voice_Intensity | Overall intensity (loudness) of the voice (vocal projection). Higher values = louder voice. |

| Voice_F0_SD | F0 variability (standard deviation of F0). Lower values = less variation in vocal frequency (more stable F0); Higher values = greater variation in vocal frequency (less stable F0). |

| IMAS (Motor) Variables | Task/Meaning |

| Balance_Jerk_EC | Eyes closed balance test—peak jerk amplitude. Higher values = greater postural adjustment irregularity. |

| Balance_Jerk_EO | Eyes open balance test—peak jerk amplitude. Higher values = greater postural adjustment irregularity. |

| Elbow Flex/Ext _PeakSpeed | Continuous elbow flexion/extension movements—peak speed of movement (average across movements). |

| Elbow Flex/Ext _MeanSpeed | Continuous elbow flexion/extension movements—mean speed of movement (average across movements). |

| Elbow Flex/Ext_MeanSpeed_SD | Continuous elbow flexion/extension movements—standard deviation for mean speed of the Elbow Flex/Ext movement. |

| Gait_StepDur_Mean | Walking test—average step duration. Higher values = slower gait. |

| Gait_StrideCount_Mean | Walking test—stride count. More strides = shorter steps. |

| ElbowDisc_MeanSpeed | Discrete elbow flexion/extension movements—mean speed of movement (average across movements). |

| HandSqueeze_InterTime | Hand opening/closing task—time between squeezes. Smaller values = faster repetition rate (average across movements). |

| HandNose_MoveDur | Hand-to-nose—mean duration of movement (average across movements). |

| Dependent Variable (Voice) | Independent Variable (Motor) | R2 | β Coefficient | p-Value | Interpretation | Pcorr | p-Value (Pcorr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voice_F0_SD | Balance_Jerk_EO | 0.78 | 2.72 | 0.001 | Higher balance jerk (eyes open, greater postural adjustment irregularity) → greater variation in vocal frequency (less stable F0). | 0.8806 | 0.0017 |

| Voice_HNR | ElbowFlex/Ext_PeakSpeed | 0.56 | 8.50 | 0.013 | Faster elbow flexion–extension movements → clearer, more periodic phonation. | 0.7601 | 0.0174 |

| Voice_HNR | ElbowDisc_MeanSpeed | 0.47 | 25.00 | 0.029 | Faster discrete elbow flexion–extension speed → clearer, more periodic phonation. | 0.6669 | 0.0498 |

| Voice_HNR | Balance_Jerk_EC | 0.41 | 1.89 | 0.045 | Higher balance jerk (eyes closed, greater postural adjustment irregularity) → clearer, more periodic phonation. | 0.6759 | 0.0457 |

| Voice_Intensity | HandNose_MoveDur | 0.40 | −26.75 | 0.027 | Longer hand-to-nose movement duration → lower vocal intensity. | −0.6389 | 0.0343 |

| Voice_Intensity | HandSqueeze_InterTime | 0.39 | 44.14 | 0.029 | Longer time between hand squeezes → higher vocal intensity. | 0.7071 | 0.0149 |

| Voice_Intensity | Balance_Jerk_EC | 0.36 | 3.16 | 0.038 | Higher balance jerk (eyes closed, greater postural adjustment irregularity) → higher vocal intensity. | 0.6103 | 0.0462 |

| Dependent Variable (Motor) | Independent Variable (Voice) | R2 | β | p-Value | Interpretation of Direction | Pcorr | p-Value (Pcorr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balance_Jerk_EO | Voice_F0_SD | 0.78 | 0.29 | 0.001 | Greater variation in vocal frequency (less stable F0) → higher balance jerk (eyes open, greater postural adjustment irregularity). | 0.8806 | 0.0017 |

| Gait_StrideCount_Mean | CPPS | 0.58 | −0.59 | 0.004 | Higher CPPS values, indicating improved vocal quality → lower stride count (fewer, longer steps to cover the 10 m). | −0.7081 | 0.0148 |

| ElbowFlex/Ext_PeakSpeed | Voice_HNR | 0.56 | 0.070 | 0.013 | Clearer, more periodic phonation → higher peak speed in continuous elbow flexion/extension movements. | 0.7601 | 0.0174 |

| ElbowFlex/Ext_MeanSpeed | Voice_HNR | 0.52 | 0.040 | 0.018 | Clearer, more periodic phonation → faster continuous elbow flexion/extension movements. | 0.7186 | 0.0292 |

| Gait_StepDur_Mean | CPPS | 0.49 | −0.63 | 0.011 | Higher CPPS values, indicating improved vocal quality → shorter walking cycle duration (faster gait). | −0.6285 | 0.0383 |

| ElbowDisc_MeanSpeed | Voice_HNR | 0.47 | 0.020 | 0.029 | Clearer, more periodic phonation → faster discrete elbow flexion/extension movements. | 0.6669 | 0.0498 |

| Balance_Jerk_EC | Voice_HNR | 0.41 | 0.220 | 0.045 | Clearer, more periodic phonation → higher balance jerk (eyes closed, greater postural adjustment irregularity). | 0.6759 | 0.0457 |

| HandNose_MoveDur | Voice_Intensity | 0.40 | −0.01 | 0.027 | Higher vocal intensity → shorter hand-to-nose movement duration (faster movements). | −0.6389 | 0.0343 |

| ElbowFlex/Ext_MeanSpeed_SD | CPPS | 0.39 | 0.020 | 0.030 | Higher CPPS values, indicating improved vocal quality → slightly greater variability in mean speed in continuous elbow flexion/extension movements. | 0.6998 | 0.0165 |

| HandSqueeze_InterTime | Voice_Intensity | 0.39 | 0.010 | 0.029 | Higher vocal intensity → longer time between squeezes (slower hand opening/closing repetition rate). | 0.707 | 0.0149 |

| Balance_Jerk_EC | Voice_Intensity | 0.36 | 0.110 | 0.038 | Higher vocal intensity → higher balance jerk (eyes closed, greater postural adjustment irregularity). | 0.6103 | 0.0462 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gianlorenço, A.C.; Teixeira, P.E.P.; Costa, V.; Fabris-Moraes, W.; Gonzalez-Mego, P.; Ramos-Estebanez, C.; Di Stadio, A.; Camsari, D.D.; El-Hagrassy, M.M.; Fregni, F.; et al. Exploring Bidirectional Associations Between Voice Acoustics and Objective Motor Metrics in Parkinson’s Disease. Brain Sci. 2026, 16, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010048

Gianlorenço AC, Teixeira PEP, Costa V, Fabris-Moraes W, Gonzalez-Mego P, Ramos-Estebanez C, Di Stadio A, Camsari DD, El-Hagrassy MM, Fregni F, et al. Exploring Bidirectional Associations Between Voice Acoustics and Objective Motor Metrics in Parkinson’s Disease. Brain Sciences. 2026; 16(1):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010048

Chicago/Turabian StyleGianlorenço, Anna Carolyna, Paulo Eduardo Portes Teixeira, Valton Costa, Walter Fabris-Moraes, Paola Gonzalez-Mego, Ciro Ramos-Estebanez, Arianna Di Stadio, Deniz Doruk Camsari, Mirret M. El-Hagrassy, Felipe Fregni, and et al. 2026. "Exploring Bidirectional Associations Between Voice Acoustics and Objective Motor Metrics in Parkinson’s Disease" Brain Sciences 16, no. 1: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010048

APA StyleGianlorenço, A. C., Teixeira, P. E. P., Costa, V., Fabris-Moraes, W., Gonzalez-Mego, P., Ramos-Estebanez, C., Di Stadio, A., Camsari, D. D., El-Hagrassy, M. M., Fregni, F., Wagner, T., & Dipietro, L. (2026). Exploring Bidirectional Associations Between Voice Acoustics and Objective Motor Metrics in Parkinson’s Disease. Brain Sciences, 16(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010048