Chronic Alcohol Use and Accelerated Brain Aging: Shared Mechanisms with Alzheimer’s Disease Pathophysiology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Alcohol-Induced Damage in Key Brain Regions

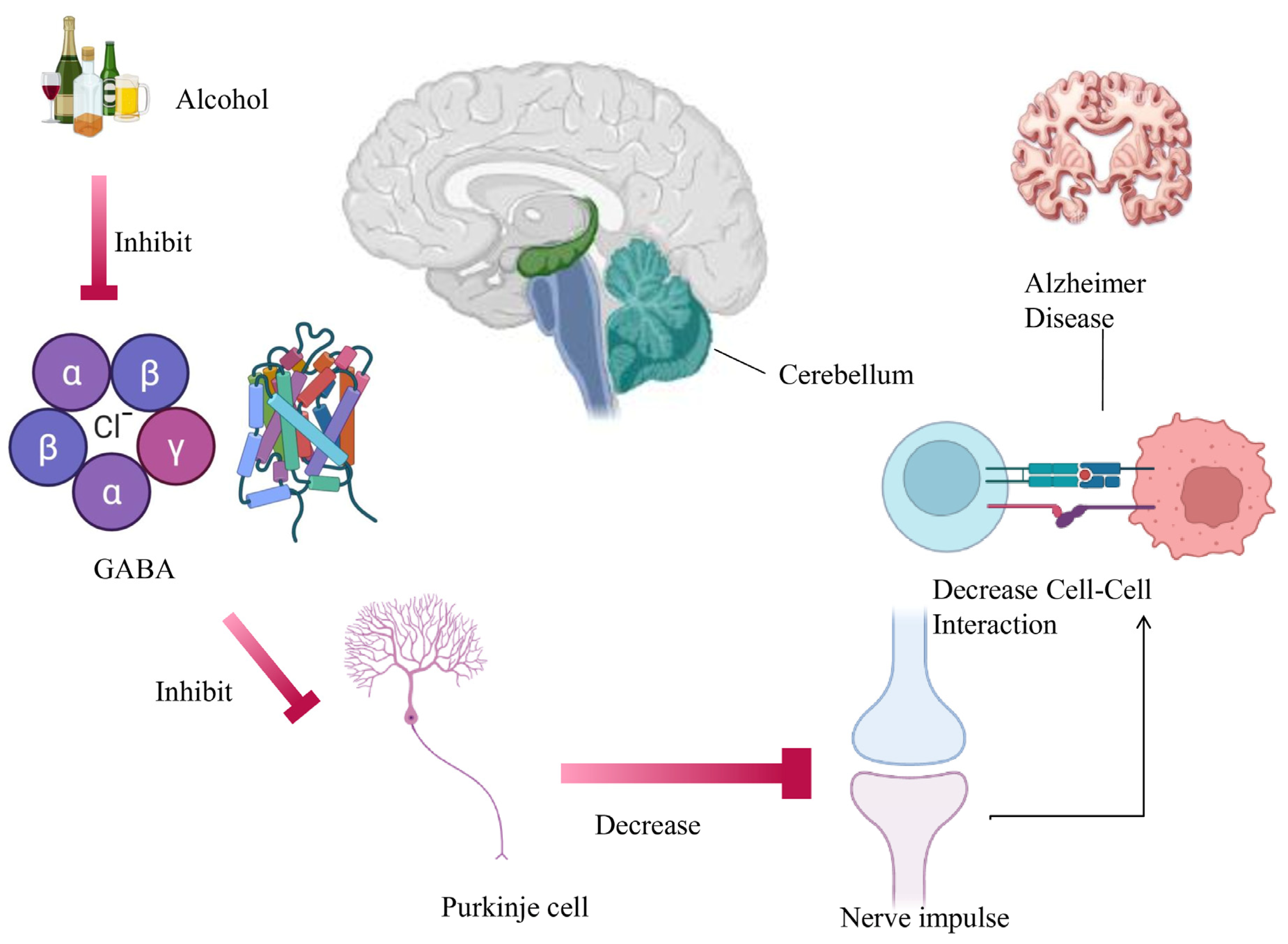

2.1. Cerebellum

2.2. Hippocampus

2.3. Hypothalamus

2.4. Amygdala

2.5. Basolateral Amygdala (BLA)

2.6. Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal (HPA Axis)

2.7. Prefrontal Cortex (PFC)

2.8. Redox Signaling in AD

3. Alcohol and Tau Pathology

4. Neuroinflammation and Microglial Priming

5. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction

6. Cholinergic Dysfunction

7. Amyloid-β Metabolism and Clearance

8. Conclusions and Public Health Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABAD | Amyloid β Binding Alcohol Dehydrogenase |

| Aβ | Amyloid-β |

| ACh | Acetylcholine |

| AD | Alzheimer’s Disease |

| AMPA | α-Amino-3-Hydroxy-5-Methyl-4-Isoxazolepropionic Acid |

| APP | Amyloid Precursor Protein |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| BACE-1 | Beta-Site APP-Cleaving Enzyme-1 |

| CA1/CA2/CA3/CA4 | Cornu Ammonis Regions of the Hippocampus |

| CeA | Central Nucleus of the Amygdala |

| ChAT | Choline Acetyltransferase |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| CRF | Corticotropin-Releasing Factor |

| CYP2E1 | Cytochrome P450 2E1 |

| DG | Dentate Gyrus |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| ER | Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| GABA | Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid |

| GABAA | Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Type A Receptor |

| GSK-3/GSK-3β | Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 Beta |

| HEK | Human Embryonic Kidney |

| HMGB1 | High-Mobility Group Box-1 |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen Peroxide |

| MAP2 | Microtubule-Associated Protein 2 |

| MCH | Melanin-Concentrating Hormone |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| mPFC | Medial Prefrontal Cortex |

| mTOR | Mammalian Target of Rapamycin |

| NMDA/NMDAR | N-Methyl-D-Aspartate (Receptor) |

| NFTs | Neurofibrillary Tangles |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa-Light-Chain-Enhancer of Activated B Cells |

| NOX | NADPH Oxidase |

| NPY | Neuropeptide Y |

| PFC | Prefrontal Cortex |

| PHF-1 | Paired Helical Filament-1 |

| POMC | Pro-opiomelanocortin |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SWRs | Sharp-Wave Ripples |

| TLR/TLR4 | Toll-Like Receptor/Toll-Like Receptor 4 |

| XOX | Xanthine Oxidase |

References

- DeTure, M.A.; Dickson, D.W. The neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2019, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, J.; Sharma, L. Potential Enzymatic Targets in Alzheimer’s: A Comprehensive Review. Curr. Drug Targets 2019, 20, 316–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Luo, J. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Ethanol Neurotoxicity. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 2538–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.; Li, S.; Xu, H.; Walsh, D.M.; Selkoe, D.J. Large soluble oligomers of amyloid β-protein from Alzheimer brain are far less neuroactive than the smaller oligomers to which they dissociate. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S.E.; Rehuman, N.A.; Harilal, S.; Vincent, A.; Rajamma, R.G.; Behl, T. Molecular mechanism of zinc neurotoxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 43542–43552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ferrari, G.V.; Inestrosa, N.C. Wnt signaling function in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. Rev. 2000, 33, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, D.; Sharma, A.; Sharma, L. A Comprehensive Review of Alzheimer’s Association with Related Proteins: Pathological Role and Therapeutic Significance. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2020, 18, 674–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, P.K.; Saharan, S.; Penna, O.; Fodale, V. Anesthesia issues in central nervous system disorders. Curr. Aging Sci. 2016, 9, 116–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagga, S.; Kumar, M. Current Status of Alzheimer’s Disease and Pathological Mechanisms Investigating the Therapeutic Molecular Targets. Curr. Mol. Med. 2023, 23, 492–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, K.C.; Chen, H.; Schwarzschild, M.; Ascherio, A. Hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, and risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology 2007, 69, 1688–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, A.; Mangialasche, F.; Richard, E.; Andrieu, S.; Bennett, D.A.; Breteler, M.; Fratiglioni, L.; Hooshmand, B.; Khachaturian, A.S.; Schneider, L.S.; et al. Advances in the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. J. Intern. Med. 2014, 275, 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aarsland, D.; Batzu, L.; Halliday, G.M.; Geurtsen, G.J.; Ballard, C.; Ray Chaudhuri, K.; Weintraub, D. Parkinson disease-associated cognitive impairment. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anstey, K.J.; Mack, H.A.; Cherbuin, N. Alcohol consumption as a risk factor for dementia and cognitive decline: Meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2009, 17, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.; Mahesh, S. (Eds.) Strengths-Based Practice in Adult Social Work and Social Care; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2025; pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Brust, J.C.M. A 74-year-old man with memory loss and neuropathy who enjoys alcoholic beverages. JAMA 2008, 299, 1046–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visontay, R.; Rao, R.T.; Mewton, L. Alcohol use and dementia: New research directions. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2021, 34, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, G.L.; Sharma, L. Bacopa monnieri abrogates alcohol abstinence-induced anxiety-like behavior by regulating biochemical and Gabra1, Gabra4, Gabra5 gene expression of GABAA receptor signaling pathway in rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 111, 1417–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedder, L.C.; Hall, J.M.; Jabrouin, K.R.; Savage, L.M. Interactions between chronic ethanol consumption and thiamine deficiency on neural plasticity, spatial memory, and cognitive flexibility. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2015, 39, 2143–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, R.J.; Yee, B.K.; Krishnaswamy, S.; Robertson, D.; Lappe-Siefke, C.; Pochmann, D.; Rinke, I.; Becker, C.M. Glycine transporters as novel therapeutic targets in schizophrenia, alcohol dependence and pain. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013, 12, 866–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S.P.; Bondugji, D. Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) and the Endocannabinoids: Understanding the Risks and Opportunities. In Natural Drugs from Plants; El-Shemy, H.A., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, H.S.; Jeong, E.-K.; Choi, S.; Kwon, Y.; Park, H.-J.; Kim, I. Changes of neurotransmitters in youth with Internet and smartphone addiction: A comparison with healthy controls and changes after cognitive behavioral therapy. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2020, 41, 1293–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, L.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, D.; Asthana, M.K.; Lalhlenmawia, H.; Kumar, A.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Kumar, D. Promising protein biomarkers in the early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Metab. Brain Dis. 2022, 37, 1727–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberto, M.; Kirson, D.; Khom, S. The role of the central amygdala in alcohol dependence. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2021, 11, a039339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.M.; Koob, G.F. Overview of addiction and the brain. In The Routledge Handbook of Social Work and Addictive Behaviors; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 58–77. [Google Scholar]

- Zha, J.; Chen, H.; Sun, Z.; Shi, R.; Yan, R.; Guo, L.; Chen, X.; Lan, X.; Huang, H.; Wang, L. Effects of esketamine on postoperative delirium and postoperative cognitive function in elderly gastrointestinal tumor patients with preoperative anxiety. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2025, 19, 9425–9437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khouja, J.N.; Attwood, A.S.; Penton-Voak, I.S.; Munafò, M.R. Effects of acute alcohol consumption on emotion recognition in social alcohol drinkers. J. Psychopharmacol. 2019, 33, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heltemes, K.J.; Dougherty, A.L.; MacGregor, A.J.; Galarneau, M.R. Alcohol abuse disorders among U.S. service members with mild traumatic brain injury. Mil. Med. 2011, 176, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, K.G.; Swygart, D.; Yin, Y.; Bauer, M.R.; Morningstar, M.D.; Timme, N.M.; Barnett, W.H.; McGonigle, C.E.; Engleman, E.A.; Sheets, P.L.; et al. Acute alcohol in prefrontal cortex is characterized by enhanced inhibition that transitions to excitation. iScience 2025, 28, 112920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrò, R.S.; Cacciola, A.; Bruschetta, D.; Milardi, D.; Quattrini, F.; Sciarrone, F.; La Rosa, G.; Bramanti, P.; Anastasi, G. Neuroanatomy and function of human sexual behavior: A neglected or unknown issue? Brain Behav. 2019, 9, e01389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, H.Y.; Feldman, J.L.; Leggio, L.; Napadow, V.; Park, J.; Price, C.J. Interventions and manipulations of interoception. Trends Neurosci. 2021, 44, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehar, U.; Rawat, P.; Reddy, A.P.; Kopel, J.; Reddy, P.H. Amyloid-β in Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawat, P.; Sehar, U.; Bisht, J.; Selman, A.; Culberson, J.; Reddy, P.H. Phosphorylated Tau in Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Tauopathies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K. Alcohol interaction with cocaine, methamphetamine, opioids, nicotine, cannabis, and γ-hydroxybutyric acid. Biomedicines 2019, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, C.J.; Drew, P.D. Neuroinflammatory contribution of microglia and astrocytes in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. J. Neurosci. Res. 2020, 99, 1973–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Nandy, S.K.; Jyoti, A.; Saxena, J.; Sharma, A.; Siddiqui, A.J.; Sharma, L. Protein Kinase C (PKC) in Neurological Health: Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease and Chronic Alcohol Consumption. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuninger, M.M.; Grosso, J.A.; Hunter, W.; Dolan, S.L. Treatment of alcohol use disorder: Integration of Alcoholics Anonymous and cognitive behavioral therapy. Train. Educ. Prof. Psychol. 2020, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Lee, J.E. Impact of drinking alcohol on gut microbiota: Recent perspectives on ethanol and alcoholic beverage. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 37, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasi, D.; Wiers, C.E.; Manza, P.; Shokri-Kojori, E.; Michele-Vera, Y.; Zhang, R.; Kroll, D.; Feldman, D.; McPherson, K.; Biesecker, C.; et al. Accelerated aging of the amygdala in alcohol use disorders: Relevance to the dark side of addiction. Cereb. Cortex 2021, 31, 3254–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egervari, G.; Siciliano, C.A.; Whiteley, E.L.; Ron, D. Alcohol and the brain: From genes to circuits. Trends Neurosci. 2021, 44, 1004–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crews, F.T.; Vetreno, R.P.; Broadwater, M.A.; Robinson, D.L. Adolescent alcohol exposure persistently impacts adult neurobiology and behavior. Pharmacol. Rev. 2016, 68, 1074–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Wu, J.; Hu, J. Non-coding RNA in alcohol use disorder by affecting synaptic plasticity. Exp. Brain Res. 2022, 240, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, B.; Sharma, R.; Yadav, S.; Parashar, V.; Jagdish, P. Ethanol exposure induces cerebellar neuronal loss in rats. Eur. J. Anat. 2020, 24, 407–413. [Google Scholar]

- Blum, K.; Gold, M.S.; Llanos-Gomez, L.; Jalali, R.; Thanos, P.K.; Bowirrat, A.; Downs, W.B.; Bagchi, D.; Braverman, E.R.; Baron, D.; et al. Hypothesizing nutrigenomic-based precision anti-obesity treatment and prophylaxis: Should we be targeting sarcopenia-induced brain dysfunction? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasten, C.R.; Holmgren, E.B.; Wills, T.A. Metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 in alcohol-induced negative affect. Brain Sci. 2019, 9, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šimić, G.; Tkalčić, M.; Vukić, V.; Mulc, D.; Španic, E.; Šagud, M.; Olucha-Bordonau, F.E.; Vukšić, M.; Hof, P.R. Understanding emotions: Origins and roles of the amygdala. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, D.S.A.; Oliver, P.L. ROS generation in microglia: Understanding oxidative stress and inflammation in neurodegenerative disease. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourzinal, D.; Yang, J.H.J.; Bakker, A.; McMahon, K.L.; Byrne, G.J.; Pontone, G.M.; Mari, Z.; Dissanayaka, N.N. Hippocampal correlates of episodic memory in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review of magnetic resonance imaging studies. J. Neurosci. Res. 2021, 99, 2097–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.L.; Ganaraja, B.; Murlimanju, B.V.; Joy, T.; Krishnamurthy, A.; Agrawal, A. Hippocampus and its involvement in Alzheimer’s disease: A review. 3 Biotech 2022, 12, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwenya, L.B.; Heyworth, N.C.; Shwe, Y.; Moore, T.L.; Rosene, D.L. Age-related changes in dentate gyrus cell numbers, neurogenesis, and associations with cognitive impairments in the rhesus monkey. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, E.V.; Pfefferbaum, A. Brain-behavior relations and effects of aging and common comorbidities in alcohol use disorder: A review. Neuropsychology 2019, 33, 760–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedrosa, R.; Nazari, M.; Mohajerani, M.H.; Knöpfel, T.; Stella, F.; Battaglia, F.P. Hippocampal gamma and sharp wave/ripples mediate bidirectional interactions with cortical networks during sleep. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2204959119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Callaghan, C.; Walpola, I.C.; Shine, J.M. Neuromodulation of the mind-wandering brain state: The interaction between neuromodulatory tone, sharp wave-ripples and spontaneous thought. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2021, 376, 20190699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribarič, S. Detecting early cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease with brain synaptic structural and functional evaluation. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordaro, M.; Salinaro, A.T.; Siracusa, R.; D’Amico, R.; Impellizzeri, D.; Scuto, M.; Ontario, M.L.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Di Paola, R.; Fusco, R.; et al. Key mechanisms and potential implications of Hericium erinaceus in NLRP3 inflammasome activation by reactive oxygen species during Alzheimer’s disease. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimers, A.; Odin, P.; Ljung, H. Drug-induced cognitive impairment. Drug Saf. 2025, 48, 339–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendell, P.G.; Mazur, M.; Henry, J.D. Prospective memory impairment in former users of methamphetamine. Psychopharmacology 2009, 203, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffernan, T.M. The impact of excessive alcohol use on prospective memory: A brief review. Curr. Drug Abuse Rev. 2008, 1, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Rodríguez, I.; Temprano-Carazo, S.; Jeremic, D.; Delgado-Garcia, J.M.; Gruart, A.; Navarro-López, J.D.; Jiménez-Díaz, L. Recognition memory induces natural LTP-like hippocampal synaptic excitation and inhibition. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Rojas, C.; Mira, R.G.; Torres, A.K.; Jara, C.; Pérez, M.J.; Vergara, E.H.; Cerpa, W.; Quintanilla, R.A. Alcohol consumption during adolescence: A link between mitochondrial damage and ethanol brain intoxication. Birth Defects Res. 2017, 109, 1623–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, M.D.; Kisler, K.; Montagne, A.; Toga, A.W.; Zlokovic, B.V. The role of brain vasculature in neurodegenerative disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 1318–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genders, S.G.; Scheller, K.J.; Djouma, E. Neuropeptide modulation of addiction: Focus on galanin. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 110, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, V.; Demirkol, A.; Ridley, N.; Withall, A.; Draper, B. Alcohol-related cognitive impairment: Current trends and future perspectives. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2016, 6, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barson, J.R.; Leibowitz, S.F. Hypothalamic neuropeptide signaling in alcohol addiction. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2015, 65, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallöf, D.; Maccioni, P.; Colombo, G.; Mandrapa, M.; Jörnulf, J.W.; Egecioglu, E.; Engel, J.A.; Jerlhag, E. The glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist liraglutide attenuates the reinforcing properties of alcohol in rodents. Addiction Biol. 2016, 21, 422–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.E. Neuropeptidomics: Mass spectrometry-based identification and quantitation of neuropeptides. Genom. Inform. 2016, 14, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joya, X.; García-Algar, O.; Salat-Batlle, J.; Pujades, C.; Vall, O. Advances in the development of novel antioxidant therapies as an approach for fetal alcohol syndrome prevention. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2015, 103, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandimalla, R.; Vallamkondu, J.; Corgiat, E.B.; Gill, K.D. Understanding aspects of aluminum exposure in Alzheimer’s disease development. Brain Pathol. 2016, 26, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomiyama, T.; Shimada, H. APP Osaka mutation in familial Alzheimer’s disease—Its discovery, phenotypes, and mechanism of recessive inheritance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, W.H.; Canals, S.; Bifone, A.; Heilig, M.; Hyytiä, P. From a systems view to spotting a hidden island: A narrative review implicating insula function in alcoholism. Neuropharmacology 2022, 209, 108989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisby, B.R.; Farris, S.P.; McManus, M.M.; Varodayan, F.P.; Roberto, M.; Harris, R.A.; Ponomarev, I. Alcohol dependence in rats is associated with global changes in gene expression in the central amygdala. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Guo, Y.; Cao, W.; Gao, W.; Qiu, J.; Su, L.; Jiao, Q.; Lu, G. Correlation between decreased amygdala subnuclei volumes and impaired cognitive functions in pediatric bipolar disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, A.; Seguin, D.; Correa, S.; Wang, J.; Martinez-Trujillo, J.C.; Nicolson, R.; Duerden, E.G. Anxiety in children and youth with autism spectrum disorder and the association with amygdala subnuclei structure. Autism 2023, 27, 1053–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kargl, D.; Kaczanowska, J.; Ulonska, S.; Groessl, F.; Piszczek, L.; Lazovic, J.; Buehler, K.; Haubensak, W. The amygdala instructs insular feedback for affective learning. eLife 2020, 9, e60336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, R.; Caruso, P.; Dal Ben, M.; Gazzin, S.; Tiribelli, C. Thiamine and alcohol for brain pathology: Super-imposing or different causative factors for brain damage? Curr. Drug Abuse Rev. 2017, 10, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson-Drummer, P.A.; Heroux, N.A.; Stanton, M.E. Antagonism of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in medial prefrontal cortex disrupts the context preexposure facilitation effect. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2017, 143, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Skike, C.E.; Goodlett, C.; Matthews, D.B. Acute alcohol and cognition: Remembering what it causes us to forget. Alcohol 2019, 79, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cabrerizo, R.; Carbia, C.; Ochoa-Sanchez, R.; Marañón, G.; O’Shea, E.; Harkin, A. Microbiota-gut-brain axis as a regulator of reward processes. J. Neurochem. 2021, 157, 1495–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiström, E.D.; O’Connell, K.S.; Karadag, N.; Bahrami, S.; Hindley, G.F.; Lin, A.; Cheng, W.; Steen, N.E.; Shadrin, A.; Frei, O.; et al. Genome-wide analysis reveals genetic overlap between alcohol use behaviours, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and identifies novel shared risk loci. Addiction 2022, 117, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Luo, S.; Chu, C.; Wu, D.; Liu, R.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, X. Extract of sesame cake and sesamol alleviate chronic unpredictable mild stress-induced depressive-like behaviors and memory deficits. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 42, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wen, S.; Zhou, J.; Ding, S. Association between malnutrition and hyperhomocysteine in Alzheimer’s disease patients and diet intervention of betaine. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2017, 31, e22090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holubiec, M.I.; Gellert, M.; Hanschmann, E.M. Redox signaling and metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 1003721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pîrşcoveanu, D.F.; Pirici, I.; Tudorică, V.A.; Bălşeanu, T.A.; Albu, V.C.; Bondari, S.; Bumbea, A.M.; Pîrşcoveanu, M. Tau protein in neurodegenerative diseases—A review. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2017, 58, 1141–1150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shanmughapriya, S.; Langford, D.; Natarajaseenivasan, K. Inter- and intracellular mitochondrial trafficking in health and disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 62, 101128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, J.L.; Faccidomo, S.; Kim, M.; Taylor, S.M.; Agoglia, A.E.; May, A.M.; Smith, E.N.; Wong, L.C.; Hodge, C.W. Alcohol drinking exacerbates neural and behavioral pathology in the 3xTg-AD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2019, 148, 169–230. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, S.J.; Chakraborty, S.; Srikumar, B.N.; Raju, T.R.; Shankaranarayana Rao, B.S. Basolateral amygdalar inactivation blocks chronic stress-induced lamina-specific reduction in prefrontal cortex volume and associated anxiety-like behavior. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 88, 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Kumar, C.; Khandia, R. The insight into the role of protein misfolding and tau oligomers in Alzheimer’s disease. In Proteostasis: Investigating Molecular Dynamics in Neurodegenerative Disorders; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 253–275. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, G.Y.; Lee, C.; Park, G.H.; Jang, J.H. Amelioration of scopolamine-induced learning and memory impairment by α-pinene in C57BL/6 mice. In Multiple Bioactivities of Traditional Medicinal Herbs for Treatment of Neurodegenerative Diseases; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Narayan, P.J.; Lill, C.; Faull, R.; Curtis, M.A.; Dragunow, M. Increased acetyl and total histone levels in post-mortem Alzheimer’s disease brain. Neurobiol. Dis. 2015, 74, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesinos, J.; Alfonso-Loeches, S.; Guerri, C. Impact of the innate immune response in the actions of ethanol on the central nervous system. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2016, 40, 2260–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciafrè, S.; Ferraguti, G.; Greco, A.; Polimeni, A.; Ralli, M.; Ceci, F.M.; Ceccanti, M.; Fiore, M. Alcohol as an early-life stressor: Epigenetic, metabolic, neuroendocrine and neurobehavioral implications. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 118, 654–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, P.T.; Kipp, B.T.; Reitz, N.L.; Savage, L.M. Aging with alcohol-related brain damage: Critical brain circuits associated with cognitive dysfunction. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2019, 148, 101–168. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lim, H.S.; Kim, J.S.; Moon, B.C.; Ryu, S.M.; Lee, J.; Park, G. Batryticatus bombyx protects dopaminergic neurons against MPTP-induced neurotoxicity by inhibiting oxidative damage. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.; Sharma, A.; Dash, A.K. A standardized polyherbal preparation POL-6 diminishes alcohol withdrawal anxiety by regulating Gabra1, Gabra2, Gabra3, Gabra4, Gabra5 gene expression of GABAA receptor signaling pathway in rats. BMC Complement Med. Ther. 2021, 21, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, L.S.; Wang, X.; Pang, P.; Wang, D.Q.; Liuyang, Z.Y.; Man, H.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, L.Q.; et al. Correcting abnormalities in miR-124/PTPN1 signaling rescues tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2020, 154, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, S.; Raza, A.; Hassan, M.I. Therapeutic targeting of glycogen synthase kinase-3: Strategy to address neurodegenerative diseases. In Protein Kinase Inhibitors; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 535–569. [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard, O.; Coleman, M. Alzheimer’s Disease: Etiology, Neuropathology and Pathogenesis; Exon Publications: Brisbane, Australia, 2020; Volume 19; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Katsumoto, A.; Takeuchi, H.; Tanaka, F. Tau pathology in chronic traumatic encephalopathy and Alzheimer’s disease: Similarities and differences. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodakuntla, S.; Jijumon, A.S.; Villablanca, C.; Gonzalez-Billault, C.; Janke, C. Microtubule-associated proteins: Structuring the cytoskeleton. Trends Cell Biol. 2019, 29, 804–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Tjernberg, L.O.; Schedin-Weiss, S. Neuronal trafficking of the amyloid precursor protein—What do we really know? Biomedicines 2021, 9, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandris, A.S.; Walker, L.; Liu, A.K.; McAleese, K.E.; Johnson, M.; Pearce, R.K.; Gentleman, S.M.; Attems, J. Cholinergic deficits and galaninergic hyperinnervation of the nucleus basalis of Meynert in Alzheimer’s disease and Lewy body disorders. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2020, 46, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, A.; Aruoma, O.I. Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease: A nutritional toxicology perspective of the impact of oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, nutrigenomics and environmental chemicals. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2020, 39, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, T.; Kim, T.; Rehman, S.U.; Khan, M.S.; Amin, F.U.; Khan, M.; Ikram, M.; Kim, M.O. Natural dietary supplementation of anthocyanins via PI3K/Akt/Nrf2/HO-1 pathways mitigate oxidative stress, neurodegeneration, and memory impairment in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 6076–6093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyon, W.M.; Thomas, A.M.; Ostroumov, A.; Dong, Y.; Dani, J.A. Potential substrates for nicotine and alcohol interactions: A focus on the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2013, 86, 1181–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda, M.L.; Nogales, F.; del Carmen Gallego-López, M.; Carreras, O. Binge drinking during adolescence causes oxidative damage-induced cardiometabolic disorders: A possible ameliorative approach with selenium supplementation. Life Sci. 2022, 301, 120618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.; Drake, D.M.; Miller, L.; Wells, P.G. Oxidative stress and DNA damage in the mechanism of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Birth Defects Res. 2019, 111, 714–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, P.; Wu, J.; Yi, W.; Ping, L.; Xinxin, H. The cascade of oxidative stress and tau protein autophagic dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dis Chall. Future 2015, 1, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Agostini, J.F.; Toé, H.C.; Vieira, K.M.; Baldin, S.L.; Costa, N.L.; Cruz, C.U.; Longo, L.; Machado, M.M.; da Silveira, T.R.; Schuck, P.F.; et al. Cholinergic system and oxidative stress changes in the brain of a zebrafish model chronically exposed to ethanol. Neurotox. Res. 2018, 33, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, T.E.; Fontana, B.D.; Bertoncello, K.T.; Franscescon, F.; Mezzomo, N.J.; Canzian, J.; Stefanello, F.V.; Parker, M.O.; Gerlai, R.; Rosemberg, D.B. Understanding the neurobiological effects of drug abuse: Lessons from zebrafish models. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 100, 109873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, R.; Prado-Cabrero, A.; Mulcahy, R.; Howard, A.; Nolan, J.M. The role of nutrition for the aging population: Implications for cognition and Alzheimer’s disease. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 10, 619–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winek, K.; Soreq, H.; Meisel, A. Regulators of cholinergic signaling in disorders of the central nervous system. J. Neurochem. 2021, 158, 1425–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Xu, S.; Zhu, W.; Wan, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Pi, L.; Lobo, M.K.; Ren, B.; Ying, Z.; et al. Decreased taurine and creatine in the thalamus may relate to minimal hepatic encephalopathy in ethanol-fed mice using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Metab. Brain Dis. 2018, 33, 345–355. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.X.; Yan, S.S. Role of mitochondrial amyloid-β in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2010, 20, S569–S578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, V.; Sharma, S. Role of mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and autophagy in progression of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 2021, 421, 117253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Domenico, F.; Barone, E.; Perluigi, M.; Butterfield, D.A. The triangle of death in Alzheimer’s disease brain: The aberrant cross-talk among energy metabolism, mTOR signaling, and protein homeostasis revealed by redox proteomics. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2017, 26, 364–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yussof, A.; Yoon, P.; Krkljes, C.; Schweinberg, S.; Cottrell, J.; Chu, T.; Chang, S.L. A meta-analysis of the effect of binge drinking on the oral microbiome and its relation to Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Yu, M.; Yang, S.; Lou, D.; Zhou, W.; Zheng, L.; Wang, Z.; Cai, F.; Zhou, W.; Li, T.; et al. Ethanol alters APP processing and aggravates Alzheimer-associated phenotypes. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 5006–5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webers, A.; Heneka, M.T.; Gleeson, P.A. The role of innate immune responses and neuroinflammation in amyloid accumulation and progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2020, 98, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padovani, A.; Benussi, A.; Cantoni, V.; Dell’Era, V.; Cotelli, M.S.; Caratozzolo, S.; Turrone, R.; Rozzini, L.; Alberici, A.; Altomare, D.; et al. Diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease with transcranial magnetic stimulation. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 65, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; Shi, X.; Ma, C. An overview on therapeutics attenuating amyloid-β level in Alzheimer’s disease: Targeting neurotransmission, inflammation, oxidative stress and enhanced cholesterol levels. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2016, 8, 246–269. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, S.; Cabrera, M.A.; Boyadjieva, N.I.; Berger, G.; Rousseau, B.; Sarkar, D.K. Alcohol increases exosome release from microglia to promote complement C1q-induced cellular death of POMC neurons in the hypothalamus in a rat model of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 7965–7979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, M.; Xu, Q.Q.; Huang, M.Q.; Zhan, R.T.; Huang, X.Q.; Yang, W.; Lin, Z.X.; Xian, Y.F. Rhynchophylline alleviates cognitive deficits in multiple transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease via modulating neuropathology and gut microbiota. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2025, 46, 1813–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonioni, A.; Raho, E.M.; Di Lorenzo, F.; Manzoli, L.; Flacco, M.E.; Koch, G. Blood phosphorylated Tau217 distinguishes amyloid-positive from amyloid-negative subjects in the Alzheimer’s disease continuum. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. 2025, 272, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| AD Model | Alcohol Exposure Protocol | Main Outcomes (Behavior, Pathology, Inflammation, Redox) | Major Conclusions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APP/PS1 mice | Chronic ethanol in drinking water (4–6 months) | Worsened spatial memory, increased Aβ burden, elevated lipid peroxidation, and reduced antioxidant enzymes. | Alcohol accelerates amyloid pathology and oxidative stress in genetically vulnerable brains. | [84,85] |

| 3xTg-AD mice | Intermittent or chronic ethanol exposure | Enhanced tau phosphorylation, synaptic loss, increased microglial activation, and mitochondrial dysfunction | Alcohol amplifies both Aβ and tau pathology via redox-inflammatory mechanisms. | [84,85] |

| Tau transgenic models | Long-term ethanol administration | Increased tau aggregation, oxidative protein damage, impaired motor and cognitive function | Redox imbalance links alcohol exposure to tau-driven neurodegeneration | [84,85] |

| Aged wild-type mice | Chronic or binge-like ethanol exposure | Cognitive deficits, neuroinflammation, glutathione depletion, mitochondrial ROS elevation | Aging reduces redox reserve, increasing sensitivity to alcohol-induced brain damage. | [84,85] |

| AD + aging models | Alcohol exposure during mid- to late-life | Exaggerated synaptic loss, impaired neurovascular coupling, and BBB disruption | Alcohol acts as a second hit that accelerates age- and AD-related redox failure. | [84,85] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Singh, N.; Nandy, S.K.; Sharma, A.; Vansh; Siddiqui, A.J.; Sharma, L. Chronic Alcohol Use and Accelerated Brain Aging: Shared Mechanisms with Alzheimer’s Disease Pathophysiology. Brain Sci. 2026, 16, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010035

Singh N, Nandy SK, Sharma A, Vansh, Siddiqui AJ, Sharma L. Chronic Alcohol Use and Accelerated Brain Aging: Shared Mechanisms with Alzheimer’s Disease Pathophysiology. Brain Sciences. 2026; 16(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010035

Chicago/Turabian StyleSingh, Nishtha, Shouvik Kumar Nandy, Aditi Sharma, Vansh, Arif Jamal Siddiqui, and Lalit Sharma. 2026. "Chronic Alcohol Use and Accelerated Brain Aging: Shared Mechanisms with Alzheimer’s Disease Pathophysiology" Brain Sciences 16, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010035

APA StyleSingh, N., Nandy, S. K., Sharma, A., Vansh, Siddiqui, A. J., & Sharma, L. (2026). Chronic Alcohol Use and Accelerated Brain Aging: Shared Mechanisms with Alzheimer’s Disease Pathophysiology. Brain Sciences, 16(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010035