Advancements and Applications of EEG in Gustatory Perception

Abstract

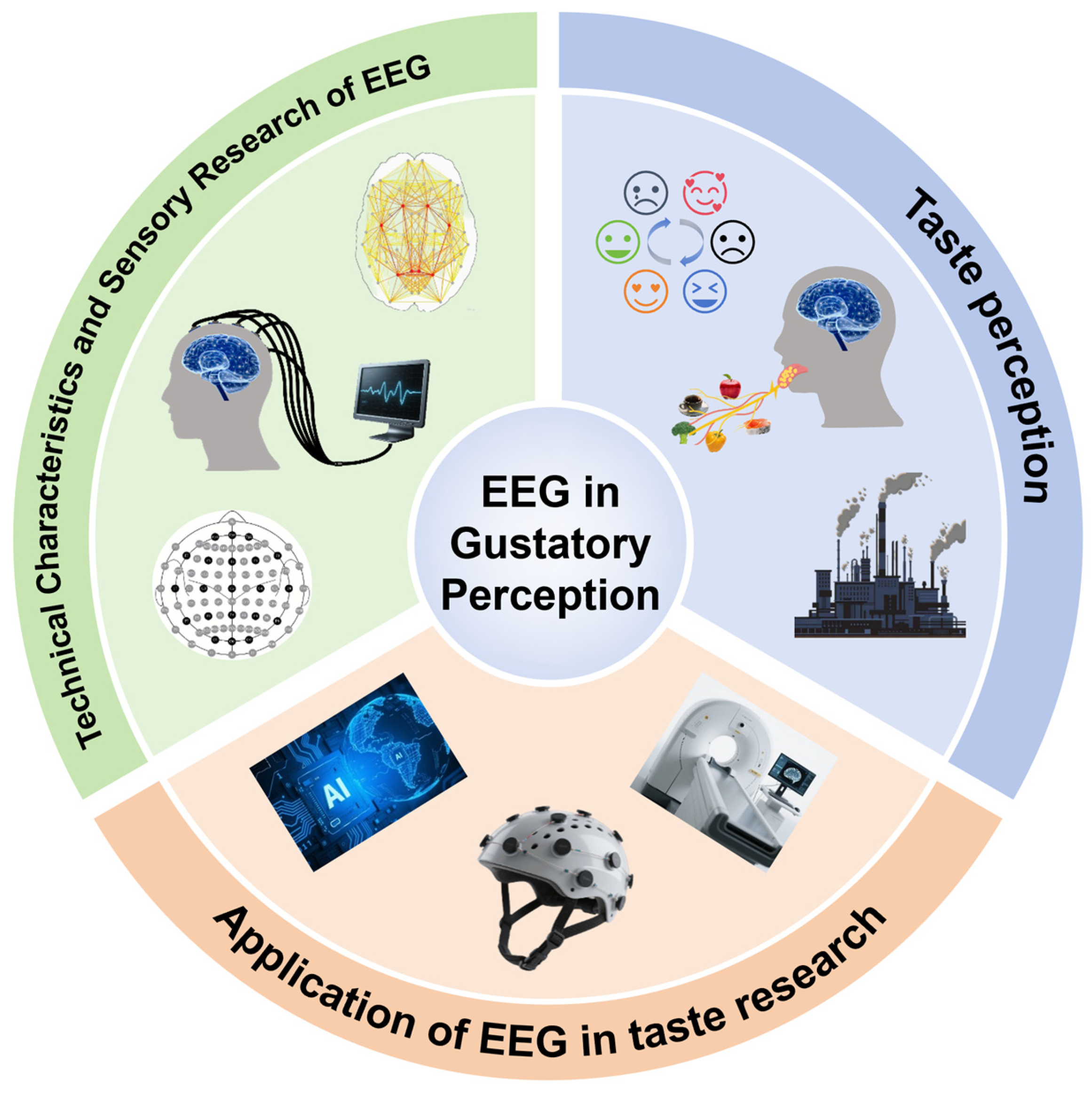

1. Introduction

Literature Search Methodology

2. Taste Perception

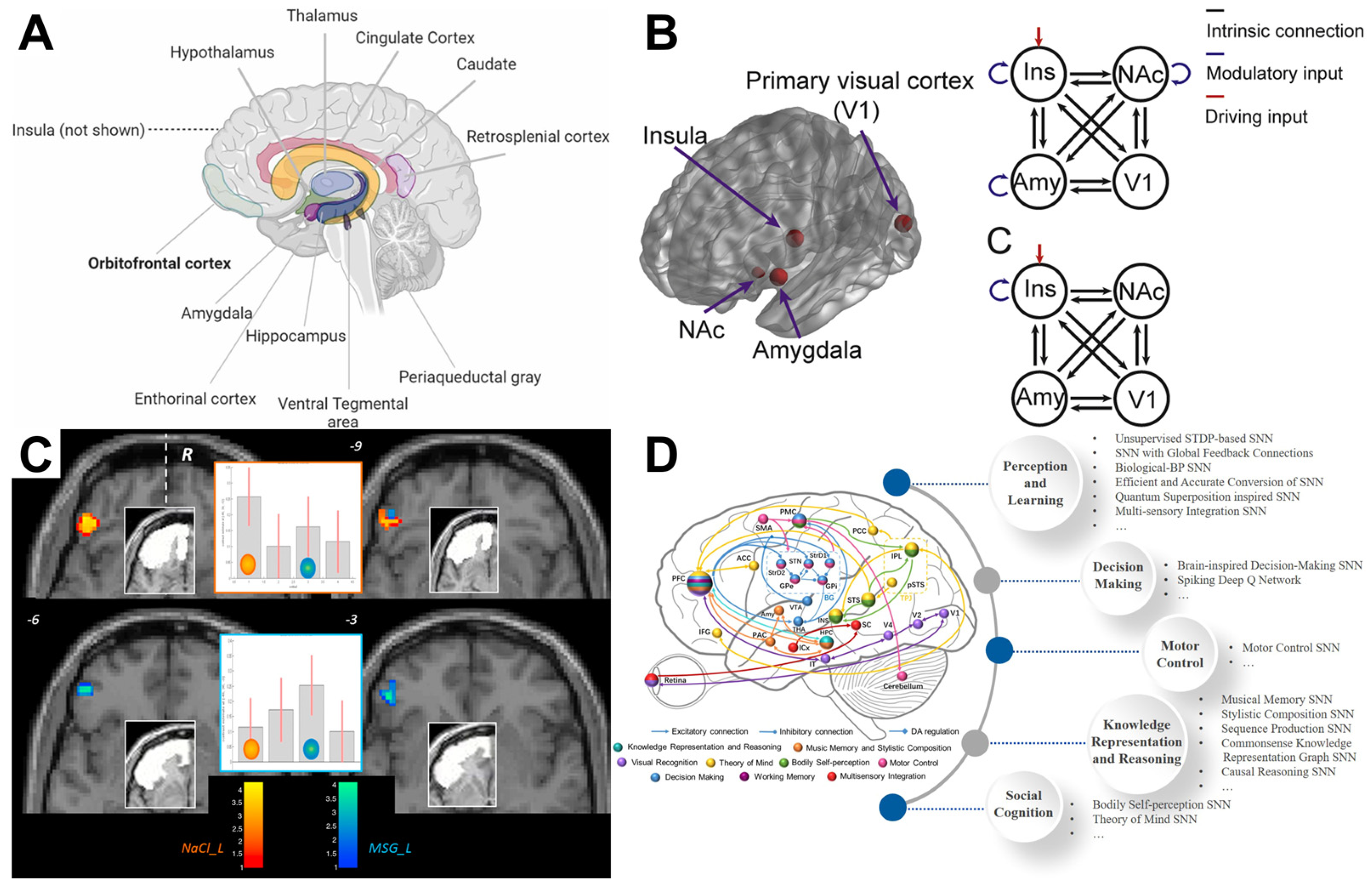

2.1. The Physiological Basis of Taste Mechanisms

2.2. The Influence of Environmental and Psychological Factors on Taste Perception

2.3. Individual Differences in Taste Perception

3. Technical Characteristics and Sensory Research of EEG

3.1. Basic Principles of EEG

3.2. EEG Signal Characteristics and Measurements

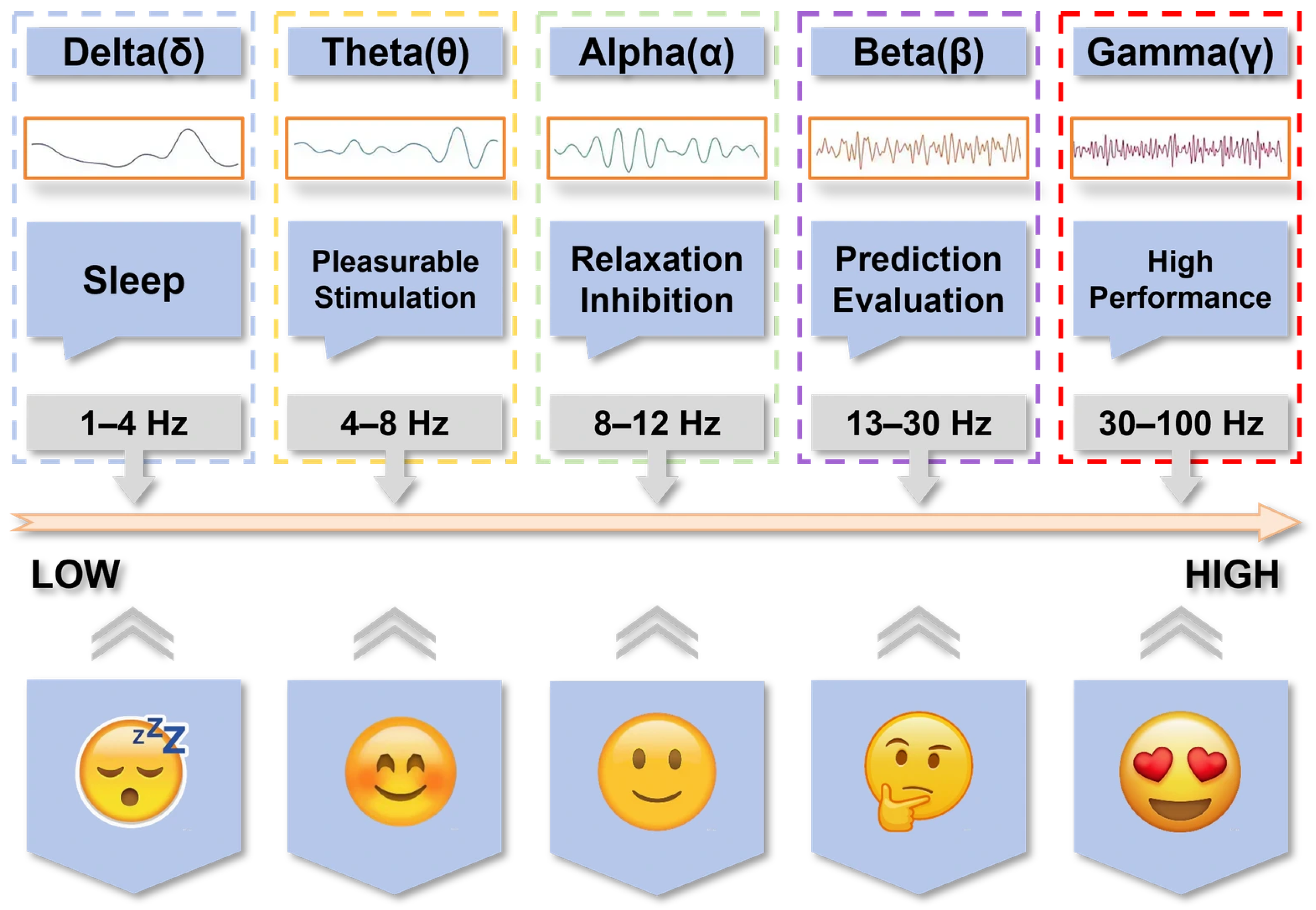

3.3. EEG Indicators Applicable to Food Sensory Research

4. Application of EEG in Taste Research

4.1. Analysis of ERPs Induced by Taste Stimuli

4.2. Power Spectrum Analysis of Taste-Related Frequency Band Characteristics

4.2.1. Delta and Theta Oscillations in Gustatory Processing

4.2.2. Alpha Oscillations and Taste Evaluation

4.2.3. Beta Oscillations and Taste Quality Discrimination

4.2.4. Gamma Oscillations and Multisensory Integration

4.2.5. Methodological Challenges and Advances in Power Spectrum Analysis

4.2.6. Individual Differences in Taste-Related Oscillations

4.3. Brain Network Analysis and Taste Perception

4.3.1. Gustatory Perception and Brain Network Dynamics

4.3.2. The Role of the Gustatory Network in Taste Processing

4.3.3. Brain Network Topology and Gustatory Perception

4.3.4. Applications of Brain Network Analysis in Gustatory Research

4.3.5. Future Directions in Brain Network Analysis and Gustatory Perception

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allar, I.B.; Hua, A.; Rowland, B.A.; Maier, J.X. Gustatory Cortex Neurons Perform Reliability-Dependent Integration of Multisensory Flavor Inputs. Curr. Biol. 2025, 35, 600–611.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.E.; Morton, L.; Braakhuis, A.J. Exploring Genetic Modifiers Influencing Adult Eating Behaviour: A Scoping Review. Appetite 2025, 214, 108193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Deng, P.; Zhang, X.; Zhai, M.; Shang, G.; Hong, B. Gustatory Perception and Its Influence on Emotional and Psychological Responses under Outdoor Thermal Stress. Urban Clim. 2025, 61, 102416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wu, X.; Liu, Z.; Shi, M.; Fan, H.; Liu, Y.; Kuang, N.; Peng, S.; Lian, Z.; Huang, C.; et al. Genetic Influence and Neural Pathways Underlying the Dose-Response Relationships between Wearable-Measured Physical Activity and Mental Health in Adolescence. Psychiatry Res. 2025, 349, 116503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuang, N.; Liu, Z.; Yu, G.; Wu, X.; Becker, B.; Fan, H.; Peng, S.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, J.; Kang, J.; et al. Neurodevelopmental Risk and Adaptation as a Model for Comorbidity among Internalizing and Externalizing Disorders: Genomics and Cell-Specific Expression Enriched Morphometric Study. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Zhu, M.; Wang, W.; Xu, C.; Li, K.; Liu, B.; Shi, X. A Preliminary Study on the Application of Electrical Impedance Tomography Based on Cerebral Perfusion Monitoring to Intracranial Pressure Changes. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1390977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliya; Jiang, S.; Jiang, X.; Chen, P.; Zhang, D.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y. Evaluation of Flavor Perception of Strong-Aroma Baijiu Based on Electroencephalography (EEG) and Surface Electromyography (EMG) Techniques. Food Chem. 2025, 472, 142893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, H.A.; Abdalla, K.K. EEG-Based Emotion Recognition Systems; Comprehensive Study. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.R.; Pereira, H.R.; Silva, M.L.; Pereira, P.; Ferreira, H.A. Impact of Five Basic Tastes Perception on Neurophysiological Response: Results from Brain Activity. Food Qual. Prefer. 2025, 131, 105572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohla, K.; Toepel, U.; le Coutre, J.; Hudry, J. Electrical Neuroimaging Reveals Intensity-Dependent Activation of Human Cortical Gustatory and Somatosensory Areas by Electric Taste. Biol. Psychol. 2010, 85, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorjan, S.; Gremsl, A.; Schienle, A. Changing the Visualization of Food to Reduce Food Cue Reactivity: An Event-Related Potential Study. Biol. Psychol. 2021, 164, 108173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, P.; Baeuchl, C.; Hoppstädter, M. Insights from Simultaneous EEG-FMRI and Patient Data Illuminate the Role of the Anterior Medial Temporal Lobe in N400 Generation. Neuropsychologia 2024, 193, 108762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, S.Y.; Jeong, Y.T. Neural Circuits for Taste Sensation. Mol. Cells 2024, 47, 100078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, V.B.; Hayes, J.E. Biological Basis and Functional Assessment of Oral Sensation. In Handbook of Eating and Drinking; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ozeck, M.; Brust, P.; Xu, H.; Servant, G. Receptors for Bitter, Sweet and Umami Taste Couple to Inhibitory G Protein Signaling Pathways. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2004, 489, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Luo, N.; Guo, C.; Luo, J.; Wei, J.; Zhang, N.; Yin, X.; Feng, X.; Wang, X.; Cao, J. Current Trends and Perspectives on Salty and Salt Taste–Enhancing Peptides: A Focus on Preparation, Evaluation and Perception Mechanisms of Salt Taste. Food Res. Int. 2024, 190, 114593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolls, E.T. Functions of the Anterior Insula in Taste, Autonomic, and Related Functions. Brain Cogn. 2016, 110, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, L.-D.; Strike, L.T.; Couvy-Duchesne, B.; de Zubicaray, G.I.; McMahon, K.; Breslin, P.A.S.; Reed, D.R.; Martin, N.G.; Wright, M.J. Associations between Brain Structure and Perceived Intensity of Sweet and Bitter Tastes. Behav. Brain Res. 2019, 363, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Z.; Zhao, L.; Shi, B.; Yu, X.; Yang, T.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Ma, C. Trigeminal Sensations in Representative Spices: Sensory Characteristics, Chemical Compounds, Salt Reduction, and Mechanisms of Saltiness Enhancement. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 162, 105112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, K.; Li, S.; Cao, H.; Guan, X. Multidimensional Exploration of the Interactions and Mechanisms between Fat and Salt: Saltiness Perception, and Taste Perception and Oxidation of Fat. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 162, 105099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, S.; Hasford, J.; Boman, L. Less Light, Better Bite: How Ambient Lighting Influences Taste Perceptions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 65, 102732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togawa, T.; Park, J.; Ishii, H.; Deng, X. A Packaging Visual-Gustatory Correspondence Effect: Using Visual Packaging Design to Influence Flavor Perception and Healthy Eating Decisions. J. Retail. 2019, 95, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaime-Lara, R.B.; Franks, A.T.; Nawal, N.; Steck, M.C.; Chao, A.M.; Allen, C.; Brooks, B.E.; Atkinson, M.; Courville, A.B.; Guo, J.; et al. The Role of Diet and Hormones on Taste: Low Carb Compared with Low Fat Study Findings. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2025, 9, 107467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, S.S.; Zervakis, J. Taste and Smell Perception in the Elderly: Effect of Medications and Disease. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2002, 44, 247–346. [Google Scholar]

- Robino, A.; Concas, M.P.; Spinelli, S.; Pierguidi, L.; Tepper, B.J.; Gasparini, P.; Prescott, J.; Monteleone, E.; Gallina Toschi, T.; Torri, L.; et al. Combined Influence of TAS2R38 Genotype and PROP Phenotype on the Intensity of Basic Tastes, Astringency and Pungency in the Italian Taste Project. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 95, 104361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbarossa, I.T.; Melis, M.; Mattes, M.Z.; Calò, C.; Muroni, P.; Crnjar, R.; Tepper, B.J. The Gustin (CA6) Gene Polymorphism, Rs2274333 (A/G), Is Associated with Fungiform Papilla Density, Whereas PROP Bitterness Is Mostly Due to TAS2R38 in an Ethnically-Mixed Population. Physiol. Behav. 2015, 138, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perna, S.; Degli Agosti, I.; Moncaglieri, F.; Nichetti, M.; Spadaccini, D.; Rondanelli, M. Association of Gene TAS1R2 Polymorphisms (RS35874116) with Food Preferences, Biochemical Parameters and Body Composition. Nutrition 2018, 50, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, J.; Seflova, J.; Park, J.; Pribadi, M.; Sanematsu, K.; Shigemura, N.; Serna, V.; Yi, F.; Mari, A.; Procko, E.; et al. The Ile191Val Is a Partial Loss-of-Function Variant of the TAS1R2 Sweet-Taste Receptor and Is Associated with Reduced Glucose Excursions in Humans. Mol. Metab. 2021, 54, 101339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padiglia, A.; Zonza, A.; Atzori, E.; Chillotti, C.; Calò, C.; Tepper, B.J.; Barbarossa, I.T. Sensitivity to 6-n-Propylthiouracil Is Associated with Gustin (Carbonic Anhydrase VI) Gene Polymorphism, Salivary Zinc, and Body Mass Index in Humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, E.L.; Duffy, V.; Oncken, C.; Litt, M.D. E-Cigarette Palatability in Smokers as a Function of Flavorings, Nicotine Content and Propylthiouracil (PROP) Taster Phenotype. Addict. Behav. 2019, 91, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeomans, M.R.; Vi, C.; Mohammed, N.; Armitage, R.M. Re-Evaluating How Sweet-Liking and PROP-Tasting Are Related. Physiol. Behav. 2022, 246, 113702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, T.; Liu, Y.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Gao, Z.; Ma, X.; Wang, W. Deciphering Cheese Taste Formation: Core Microorganisms, Enzymatic Catalysis, and Metabolic Mechanisms. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 162, 105089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Bakry, A.M.; Shi, L.; Zhan, P.; He, W.; Eid, W.A.M.; Ferweez, H.; Hamed, Y.S.; Ismail, H.A.; Tian, H.; et al. Mechanistic Insights into Cross-Modal Aroma-Taste Interactions Mediating Sweetness Perception Enhancement in Fu Brick Tea. Food Chem. 2025, 489, 144933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaumont, J.D.; Davis, D.; Dalton, M.; Nowicky, A.; Russell, M.; Barwood, M.J. The Effect of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (TDCS) on Food Craving, Reward and Appetite in a Healthy Population. Appetite 2021, 157, 105004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.; Wang, M.; Du, J.; Dai, Y.; Dang, L.; Li, Z.; Shu, J. Glycans in the Oral Bacteria and Fungi: Shaping Host-Microbe Interactions and Human Health. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 136932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Ye, X.; Liu, J.; Xiao, Y.; Tan, M.; Deng, Y.; Yuan, M.; Luo, X.; Zhang, D.; Xie, X.; et al. Recent Advancements in the Taste Transduction Mechanism, Identification, and Characterization of Taste Components. Food Chem. 2024, 433, 137282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Feng, X.; Blank, I.; Wang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Ni, L.; Lin, C.-C.; Wang, K.; Liu, Y. A Review of Umami Taste of Tea: Substances, Perception Mechanism, and Physiological Measurement Prospects. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 162, 105082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Cui, Y.; Wei, C.; Polat, K.; Alenezi, F. Advances in EEG-Based Emotion Recognition: Challenges, Methodologies, and Future Directions. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 180, 113478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Park, J.; Rosenberg, M.D. Understanding Cognitive Processes across Spatial Scales of the Brain. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2025, 29, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paus, T. Tracking Development of Connectivity in the Human Brain: Axons and Dendrites. Biol. Psychiatry 2023, 93, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, B.; Liang, L.; Wang, Y.; Gao, S.; Gao, X. Signal Acquisition of Brain–Computer Interfaces: A Medical-Engineering Crossover Perspective Review. Fundam. Res. 2025, 5, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, I. Removal of Physiological Artifacts from Simultaneous EEG and FMRI Recordings. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2021, 132, 2371–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi-Sargezeh, B.; Foodeh, R.; Shalchyan, V.; Daliri, M.R. EEG Artifact Rejection by Extracting Spatial and Spatio-Spectral Common Components. J. Neurosci. Methods 2021, 358, 109182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hou, S.; Li, F.; Long, S.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhao, L.; Yu, Y. Preoperative Recovery Sleep Ameliorates Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction Aggravated by Sleep Fragmentation in Aged Mice by Enhancing EEG Delta-Wave Activity and LFP Theta Oscillation in Hippocampal CA1. Brain Res. Bull. 2024, 211, 110945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncharova, I.I.; Barlow, J.S. Changes in EEG Mean Frequency and Spectral Purity during Spontaneous Alpha Blocking. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1990, 76, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohaia, W.; Saurels, B.W.; Johnston, A.; Yarrow, K.; Arnold, D.H. Occipital Alpha-Band Brain Waves When the Eyes Are Closed Are Shaped by Ongoing Visual Processes. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Xu, M. Landscape Perception Identification and Classification Based on Electroencephalogram (EEG) Features. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saminu, S.; Xu, G.; Zhang, S.; Kader, I.A.E.; Aliyu, H.A.; Jabire, A.H.; Ahmed, Y.K.; Adamu, M.J. Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Automatic Detection of Epileptic Seizures Using EEG Signals: A Review. Artif. Intell. Appl. 2022, 1, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimzadeh, E.; Saharkhiz, S.; Rajabion, L.; Oskouei, H.B.; Seraji, M.; Fayaz, F.; Saliminia, S.; Sadjadi, S.M.; Soltanian-Zadeh, H. Simultaneous Electroencephalography-Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Assessment of Human Brain Function. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 934266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.K.; Krishnan, S. Trends in EEG Signal Feature Extraction Applications. Front. Artif. Intell. 2023, 5, 1072801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanei, S.; Chambers, J.A. EEG Signal Processing and Machine Learning; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; ISBN 9781119386940. [Google Scholar]

- Oliva, C.; Changoluisa, V.; Rodríguez, F.B.; Lago-Fernández, L.F. Detecting P300-ERPs Building a Post-Validation Neural Ensemble with Informative Neurons from a Recurrent Neural Network. In Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ignatious, E.; Azam, S.; Jonkman, M.; De Boer, F. Frequency and Time Domain Analysis of EEG Based Auditory Evoked Potentials to Detect Binaural Hearing in Noise. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farago, E.; MacIsaac, D.; Suk, M.; Chan, A.D.C. A Review of Techniques for Surface Electromyography Signal Quality Analysis. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 16, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjan, D.; Gramann, K.; De Pauw, K.; Marusic, U. Removal of Movement-Induced EEG Artifacts: Current State of the Art and Guidelines. J. Neural Eng. 2022, 19, 011004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, C.; Li, M.; Balaban, E.; Casson, A.J. Motion Artefact Removal in Electroencephalography and Electrocardiography by Using Multichannel Inertial Measurement Units and Adaptive Filtering. Healthc. Technol. Lett. 2021, 8, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrisani, L.; Arpaia, P.; De Benedetto, E.; Duraccio, L.; Regio, F.L.; Tedesco, A. Wearable Brain–Computer Interfaces Based on Steady-State Visually Evoked Potentials and Augmented Reality: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 16501–16514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Lin, R.; Mutlu, M.C.; Lorentz, L.; Shaikh, U.J.; Graeve, J.D.; Badkoubeh, N.; Zeng, R.R.; Klein, F.; Lührs, M.; et al. The Use of Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (FNIRS) for Monitoring Brain Function, Predicting Outcomes, and Evaluating Rehabilitative Interventional Responses in Poststroke Patients with Upper Limb Hemiplegia: A Systematic Review. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2025, 31, 6800210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chang, X.; Zhang, C.; Lan, H.; Huang, M.; Zhou, B.; Sun, B. Beyond Aromas: Exploring the Development and Potential Applications of Electroencephalography in Olfactory Research—From General Scents to Food Flavor Science Frontiers. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 16, 147–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zsoldos, I.; Sinding, C.; Chambaron, S. Using Event-Related Potentials to Study Food-Related Cognition: An Overview of Methods and Perspectives for Future Research. Brain Cogn. 2022, 159, 105864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fields, E.C. The P300, the LPP, Context Updating, and Memory: What Is the Functional Significance of the Emotion-Related Late Positive Potential? Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2023, 192, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, A.; Port, J.D.; Acosta, A. Integrative Hedonic and Homeostatic Food Intake Regulation by the Central Nervous System: Insights from Neuroimaging. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codispoti, M.; De Cesarei, A.; Ferrari, V. Alpha-band Oscillations and Emotion: A Review of Studies on Picture Perception. Psychophysiology 2023, 60, e14438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahumada-Méndez, F.; Lucero, B.; Avenanti, A.; Saracini, C.; Muñoz-Quezada, M.T.; Cortés-Rivera, C.; Canales-Johnson, A. Affective Modulation of Cognitive Control: A Systematic Review of EEG Studies. Physiol. Behav. 2022, 249, 113743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahar, N.S.; Mat Safri, N.; Zakaria, N.A. Use of EEG Technique in a Cognitive Process Study- A Review. ELEKTRIKA-J. Electr. Eng. 2022, 21, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturtewagen, L.; van Mil, H.; van der Linden, E. Complexity, Uncertainty, and Entropy: Applications to Food Sensory Perception and Other Complex Phenomena. Entropy 2025, 27, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Ye, Z.; Deng, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, D.; Ye, X.; Cheng, H. An Advance in Novel Intelligent Sensory Technologies: From an Implicit-tracking Perspective of Food Perception. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adem, A.; Çakıt, E.; Dağdeviren, M.; Szopa, A.; Karwowski, W. A Symbiosis of Multi-Criteria Decision Making and Electroencephalography: A Review of Techniques, Applications, and Future Directions. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 75071–75088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Sharma, A. Advances in Non-Invasive EEG-Based Brain-Computer Interfaces: Signal Acquisition, Processing, Emerging Approaches, and Applications. In Signal Processing Strategies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 281–310. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Gu, Y.; Teng, J.; Zheng, S.; Pang, Y.; Lu, X.; Liu, B.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Q. Advancing EEG-Based Brain-Computer Interface Technology via PEDOT:PSS Electrodes. Matter 2024, 7, 2859–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmousalami, H.; Hui, F.K.P.; Aye, L. Electroencephalography (EEG) for Psychological Hazards and Mental Health in Construction Safety Automation: Algorithmic Systematic Review (ASR). Autom. Constr. 2025, 177, 106346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Zhang, P.; Xing, L.; Hu, J.; Feng, R.; Zhong, J.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Yang, Y.; et al. Insights into Brain Perceptions of the Different Taste Qualities and Hedonic Valence of Food via Scalp Electroencephalogram. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso-Cladera, A.; Bremer, M.; Ladouce, S.; Parada, F. A Systematic Review of Mobile Brain/Body Imaging Studies Using the P300 Event-Related Potentials to Investigate Cognition beyond the Laboratory. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2024, 24, 631–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranwal, A.; Gadhvi, M.A.; Dixit, A. Unveiling the Scented Spectrum: A Mini Review of Objective Olfactory Assessment and Event-Related Potentials. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2024, 139, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franken, I.H.A.; Huijding, J.; Nijs, I.M.T.; van Strien, J.W. Electrophysiology of Appetitive Taste and Appetitive Taste Conditioning in Humans. Biol. Psychol. 2011, 86, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, S.; Hensels, I.S.; Talmi, D. An EEG Study on the Effect of Being Overweight on Anticipatory and Consummatory Reward in Response to Pleasant Taste Stimuli. Physiol. Behav. 2022, 252, 113819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannilli, E.; Sorokowska, A.; Zhigang, Z.; Hähner, A.; Warr, J.; Hummel, T. Source Localization of Event-Related Brain Activity Elicited by Food and Nonfood Odors. Neuroscience 2015, 289, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, R.; Qi, Y.; Wan, X. An Event-Related Potential Study of Consumers’ Responses to Food Bundles. Appetite 2020, 147, 104538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinding, C.; Thibault, H.; Hummel, T.; Thomas-Danguin, T. Odor-Induced Saltiness Enhancement: Insights Into The Brain Chronometry Of Flavor Perception. Neuroscience 2021, 452, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welge-Lüssen, A.; Drago, J.; Wolfensberger, M.; Hummel, T. Gustatory Stimulation Influences the Processing of Intranasal Stimuli. Brain Res. 2005, 1038, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruijter, J.; de Ruiter, M.B.; Snel, J.; Lorist, M.M. The Influence of Caffeine on Spatial-Selective Attention: An Event-Related Potential Study. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2000, 111, 2223–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criado, J.R.; Ehlers, C.L. Event-Related Oscillations as Risk Markers in Genetic Mouse Models of High Alcohol Preference. Neuroscience 2009, 163, 506–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Feig, E.H.; Winter, S.R.; Kounios, J.; Erickson, B.; Berkowitz, S.A.; Lowe, M.R. The Role of Hunger State and Dieting History in Neural Response to Food Cues: An Event-Related Potential Study. Physiol. Behav. 2017, 179, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jackson, T.; Wang, J.; Yang, R.; Chen, H. Effects of Negative Mood State on Event-Related Potentials of Restrained Eating Subgroups during an Inhibitory Control Task. Behav. Brain Res. 2020, 377, 112249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirsten, H.; Seib-Pfeifer, L.-E.; Gibbons, H. Effects of the Calorie Content of Visual Food Stimuli and Simulated Situations on Event-Related Frontal Alpha Asymmetry and Event-Related Potentials in the Context of Food Choices. Appetite 2022, 169, 105805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Pan, F.; Stöppelmann, F.; Liang, J.; Qin, D.; Xiang, C.; Rigling, M.; Hannemann, L.; Wagner, T.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Unlocking the Potential of Odor-Induced Sugar Reduction: An Updated Review of the Underlying Mechanisms, Substance Selections, and Technical Methodologies. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 147, 104423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbertson, T.A.; Damak, S.; Margolskee, R.F. The Molecular Physiology of Taste Transduction. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2000, 10, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, K. Umami the Fifth Basic Taste: History of Studies on Receptor Mechanisms and Role as a Food Flavor. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 189402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raggi, A.; Serretti, A.; Ferri, R. The P300 Component of the Auditory Event-Related Potential in Adult Psychiatric and Neurologic Disorders: A Narrative Review of Clinical and Experimental Evidence. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2025, 40, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olichney, J.; Xia, J.; Church, K.J.; Moebius, H.J. Predictive Power of Cognitive Biomarkers in Neurodegenerative Disease Drug Development: Utility of the P300 Event-Related Potential. Neural Plast. 2022, 2022, 2104880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, P. Advances in Research on Brain Processing of Food Odors Using Different Neuroimaging Techniques. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 42, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohla, K.; Busch, N.A.; Lundström, J.N. Time for Taste—A Review of the Early Cerebral Processing of Gustatory Perception. Chemosens. Percept. 2012, 5, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiluy, J.C.; David, I.A.; Daquer, A.F.C.; Duchesne, M.; Volchan, E.; Appolinario, J.C. A Systematic Review of Electrophysiological Findings in Binge-Purge Eating Disorders: A Window Into Brain Dynamics. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 619780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chami, R.; Cardi, V.; Lautarescu, A.; Mallorquí-Bagué, N.; McLoughlin, G. Neural Responses to Food Stimuli among Individuals with Eating and Weight Disorders: A Systematic Review of Event-Related Potentials. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2019, 31, 318–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, D.; Toet, A.; Brouwer, A.-M.; Kallen, V.; van Erp, J.B.F. Methods for Evaluating Emotions Evoked by Food Experiences: A Literature Review. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pause, B.M.; Sojka, B.; Krauel, K.; Ferstl, R. The Nature of the Late Positive Complex within the Olfactory Event-related Potential (OERP). Psychophysiology 1996, 33, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudziol, H.; Guntinas-Lichius, O. Electrophysiologic Assessment of Olfactory and Gustatory Function. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2019, 164, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Domínguez, P.R. The Study of Postnatal and Later Development of the Taste and Olfactory Systems Using the Human Brain Mapping Approach: An Update. Brain Res. Bull. 2011, 84, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mydlikowska-Śmigórska, A.; Śmigórski, K.; Rymaszewska, J. Characteristics of Olfactory Function in a Healthy Geriatric Population. Differences between Physiological Aging and Pathology. Psychiatr. Pol. 2019, 53, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfano, V.; Mele, G.; Cotugno, A.; Longarzo, M. Multimodal Neuroimaging in Anorexia Nervosa. J. Neurosci. Res. 2020, 98, 2178–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.-H.; Hsieh, S.-W.; Huang, P.; Liu, H.-Y.; Chen, C.-H.; Hung, C.-H. Pharmacological Management of Dysphagia in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease: A Narrative Review. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2022, 19, 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmony, T. The Functional Significance of Delta Oscillations in Cognitive Processing. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbarasan, R.; Gomez Carmona, D.; Mahendran, R. Human Taste-Perception: Brain Computer Interface (BCI) and Its Application as an Engineering Tool for Taste-Driven Sensory Studies. Food Eng. Rev. 2022, 14, 408–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Líbano, D.; Kay, L.M. Olfactory System Gamma Oscillations: The Physiological Dissection of a Cognitive Neural System. Cogn. Neurodyn. 2008, 2, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganzetti, M.; Mantini, D. Functional Connectivity and Oscillatory Neuronal Activity in the Resting Human Brain. Neuroscience 2013, 240, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.N. Human Electroencephalographic (EEG) Response to Olfactory Stimulation: Two Experiments Using the Aroma of Food. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 1998, 30, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagyu, T.; Kondakor, I.; Kochi, K.; Koenig, T.; Lehmann, D.; Kinoshita, T.; Hirota, T.; Yagyu, T. Smell and Taste of Chewing Gum Affect Frequency Domain Eeg Source Localizations. Int. J. Neurosci. 1998, 93, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HajiHosseini, A.; Hutcherson, C.A. Alpha Oscillations and Event-Related Potentials Reflect Distinct Dynamics of Attribute Construction and Evidence Accumulation in Dietary Decision Making. eLife 2021, 10, e60874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastinu, M.; Grzeschuchna, L.S.; Mignot, C.; Guducu, C.; Bogdanov, V.; Hummel, T. Time–Frequency Analysis of Gustatory Event Related Potentials (GERP) in Taste Disorders. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Zhang, B.; Hu, L.; Zhuang, L.; Hu, N.; Wang, P. A Novel Bioelectronic Tongue in Vivo for Highly Sensitive Bitterness Detection with Brain–Machine Interface. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 78, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fourcaud-Trocmé, N.; Lefèvre, L.; Garcia, S.; Messaoudi, B.; Buonviso, N. High Beta Rhythm Amplitude in Olfactory Learning Signs a Well-Consolidated and Non-Flexible Behavioral State. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senkowski, D.; Talsma, D.; Grigutsch, M.; Herrmann, C.S.; Woldorff, M.G. Good Times for Multisensory Integration: Effects of the Precision of Temporal Synchrony as Revealed by Gamma-Band Oscillations. Neuropsychologia 2007, 45, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, D.B.; Coffman, B.A.; Bustillo, J.R.; Aine, C.J.; Stephen, J.M. Multisensory Stimuli Elicit Altered Oscillatory Brain Responses at Gamma Frequencies in Patients with Schizophrenia. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misselhorn, J.; Schwab, B.C.; Schneider, T.R.; Engel, A.K. Synchronization of Sensory Gamma Oscillations Promotes Multisensory Communication. eNeuro 2019, 6, ENEURO.0101-19.2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Wang, Z. Neural Oscillations and Multisensory Processing. In Advances of Multisensory Integration in the Brain; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Senkowski, D.; Schneider, T.R.; Foxe, J.J.; Engel, A.K. Crossmodal Binding through Neural Coherence: Implications for Multisensory Processing. Trends Neurosci. 2008, 31, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, B.J.; White, E.A.; Koelliker, Y.; Lanzara, C.; D’Adamo, P.; Gasparini, P. Genetic Variation in Taste Sensitivity to 6-n-Propylthiouracil and Its Relationship to Taste Perception and Food Selection. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1170, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewnowski, A. Nontasters, Tasters, and Supertasters of 6-n-Propylthiouracil (PROP) and Hedonic Response to Sweet. Physiol. Behav. 1997, 62, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewnowski, A. Genetic Taste Responses to 6-n-Propylthiouracil Among Adults: A Screening Tool for Epidemiological Studies. Chem. Senses 2001, 26, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, M.; Laurienti, P.J.; Shappell, H.M.; Simpson, S.L. Brain Network Analysis: A Review on Multivariate Analytical Methods. Brain Connect 2023, 13, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohla, K. Flexible and Dynamic Representations of Gustatory Information. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2021, 20, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogut, E. Mathematical and Dynamic Modeling of the Anatomical Localization of the Insula in the Brain. Neuroinformatics 2025, 23, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lorenzo, P.M. Taste in the Brain Is Encoded by Sensorimotor State Changes. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2021, 20, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boughter, J.D.; Fletcher, M. Rethinking the Role of Taste Processing in Insular Cortex and Forebrain Circuits. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2021, 20, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannilli, E.; Gudziol, V. Gustatory Pathway in Humans: A Review of Models of Taste Perception and Their Potential Lateralization. J. Neurosci. Res. 2019, 97, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, J.V.; Engelen, L. The Neurocognitive Bases of Human Multimodal Food Perception: Sensory Integration. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2006, 30, 613–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.M. Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (FMRI) in Food Research: A Three-Decade Retrospective Bibliometric Network Analysis. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2025, 23, 246–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Ji, H.; Kong, J.; Yan, W.; Zhang, Q.; Li, J.; Zuo, M. Recent Advances and Applications of Deep Learning, Electroencephalography, and Modern Analysis Techniques in Screening, Evaluation, and Mechanistic Analysis of Taste Peptides. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 150, 104607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, W.; Qin, D.; Zheng, X.; Wang, Y.; Ding, B.; Li, Y.; Liang, G. Prediction of Bitterant and Sweetener Using Structure-Taste Relationship Models Based on an Artificial Neural Network. Food Res. Int. 2022, 153, 110974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, D.; Shan, Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, B.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y. Recent Trends in Aroma Release and Perception during Food Oral Processing: A Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 3441–3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukaew, T. The Current and Emerging Research Related Aroma and Flavor. In Aroma and Flavor in Product Development: Characterization, Perception, and Application; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 329–369. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.; Baek, S.-H.; Lai, M.K.P.; Arumugam, T.V.; Jo, D.-G. Aging-Associated Sensory Decline and Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2024, 19, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruge, O.; Hoppe, J.P.M.; Dalle Molle, R.; Silveira, P.P. Early Environmental Influences on the Orbito-Frontal Cortex Function and Its Effects on Behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2025, 169, 106013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Ishida, T. The Effect of Multiband Sequences on Statistical Outcome Measures in Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Using a Gustatory Stimulus. Neuroimage 2024, 300, 120867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannilli, E.; Singh, P.B.; Schuster, B.; Gerber, J.; Hummel, T. Taste Laterality Studied by Means of Umami and Salt Stimuli: An FMRI Study. Neuroimage 2012, 60, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.; Zhao, D.; Zhao, F.; Shen, G.; Dong, Y.; Lu, E.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Liang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; et al. BrainCog: A Spiking Neural Network Based, Brain-Inspired Cognitive Intelligence Engine for Brain-Inspired AI and Brain Simulation. Patterns 2023, 4, 100789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Components | Taste | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ERPs | P1, P3 | Sweet Fluid | [75] |

| P1, N1, P2, P3 | Orange and Apple/Blackcurrant | [76] | |

| P1, N1 | Sour, Salty and Metallic Tastes | [10] | |

| P1, N1 | Strawberry and Lily | [77] | |

| P1, N2 | Yogurt | [78] | |

| P1, P3 | Green-pea Puree, Salty Solution, Evian Water | [79] | |

| P1, N1 | Sweet, Sour | [80] | |

| P1, N1, P2, N2 | Caffeine | [81] | |

| P1, N1, P3 | Alcohol | [82] | |

| N1, P2, LPP | Brownie, Cheeseburger, Cucumber, Rice | [83] | |

| N2, P3 | High-caloric and Low-caloric | [84] | |

| P3, LPP | High-caloric and Low-caloric | [85] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, L.; Zhang, C.; Wu, W.; Xie, J.; Ding, Z. Advancements and Applications of EEG in Gustatory Perception. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1317. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121317

Yang L, Zhang C, Wu W, Xie J, Ding Z. Advancements and Applications of EEG in Gustatory Perception. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1317. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121317

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Lingfeng, Chengpeng Zhang, Wei Wu, Jing Xie, and Zhaoyang Ding. 2025. "Advancements and Applications of EEG in Gustatory Perception" Brain Sciences 15, no. 12: 1317. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121317

APA StyleYang, L., Zhang, C., Wu, W., Xie, J., & Ding, Z. (2025). Advancements and Applications of EEG in Gustatory Perception. Brain Sciences, 15(12), 1317. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121317