Real-World Open-Label Experience with Rimegepant for the Acute Treatment of Migraine Attacks: A Multicenter Pilot Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018, 38, 1–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsarava, Z.; Buse, D.C.; Manack, A.N.; Lipton, R.B. Defining the differences between episodic migraine and chronic migraine. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2012, 16, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorlund, K.; Toor, K.; Wu, P.; Chan, K.; Druyts, E.; Ramos, E.; Bhambri, R.; Donnet, A.; Stark, R.; Goadsby, P.J. Comparative tolerability of treatments for acute migraine: A network meta-analysis. Cephalalgia 2017, 37, 965–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermitzakis, E.V.; Argyriou, A.A.; Bilias, K.; Barmpa, E.; Liapi, S.; Rikos, D.; Xiromerisiou, G.; Soldatos, P.; Vikelis, M. Results of a Web-Based Survey on 2565 Greek Migraine Patients in 2023: Demographic Data, Imposed Burden and Satisfaction to Acute and Prophylactic Treatments in the Era of New Treatment Options. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderPluym, J.H.; Singh, R.B.H.; Urtecho, M.; Morrow, A.S.; Nayfeh, T.; Roldan, V.D.T.; Farah, M.H.; Hasan, B.; Saadi, S.; Shah, S.; et al. Acute Treatments for Episodic Migraine in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 2021, 325, 2357–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, S.H.; Cho, S.; Kim, K.M.; Chu, M.K. Most bothersome symptom in migraine and probable migraine: A population-based study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikelis, M.; Rikos, D.; Argyriou, A.A.; Papachristou, P.; Rallis, D.; Karapanayiotides, T.; Galanopoulos, A.; Spingos, K.; Dimisianos, N.; Giakoumakis, E.; et al. Preferences and perceptions of 617 migraine patients on acute and preventive migraine treatment attributes and clinical trial endpoints. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2024, 24, 815–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenaerts, M.E.; Couch, J.R., Jr. Treatment of headache following triptan failure after successful triptan therapy. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2015, 17, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Xu, L.; He, Y.; Lv, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Li, L. Efficacy of triptans for the treatment of acute migraines: A quantitative comparison based on the dose-effect and time-course characteristics. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 75, 1369–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorlund, K.; Mills, E.J.; Wu, P.; Ramos, E.; Chatterjee, A.; Druyts, E.; Goadsby, P.J. Comparative efficacy of triptans for the abortive treatment of migraine: A multiple treatment comparison meta-analysis. Cephalalgia 2014, 34, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanshani, S.; Chen, C.; Lin, B.; Duan, L.; Shen, Y.A.; Lee, M. Risk of Acute Myocardial Infarction, Heart Failure, and Death in Migraine Patients Treated with Triptans. Headache 2020, 60, 2166–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyriou, A.A.; Mantovani, E.; Mitsikostas, D.-D.; Vikelis, M.; Tamburin, S. A systematic review with expert opinion on the role of gepants for the preventive and abortive treatment of migraine. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2022, 22, 469–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfizer Limited USA. Summary of Product Characteristics. Vydura INN-Rimegepant Sulfate. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community-register/2022/20220425155292/anx_155292_en.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Wang, Q.; Wang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, F. Clinical efficacy and safety of rimegepant in the treatment of migraine: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1205778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, R.; Hanna, M.S.; Morris, B.A.; Matschke, K.T.; Bertz, R.; Croop, R.S.; Liu, J. No clinically relevant electrocardiogram effects in a randomized TQT study of single therapeutic/supratherapeutic rimegepant doses in healthy adults. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2024, 17, e13727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermitzakis, E.V.; Vikelis, M.; Xiromerisiou, G.; Rallis, D.; Soldatos, P.; Litsardopoulos, P.; Rikos, D.; Argyriou, A.A. Nine-Month Continuous Fremanezumab Prophylaxis on the Response to Triptans and Also on the Incidence of Triggers, Hypersensitivity and Prodromal Symptoms of Patients with High-Frequency Episodic Migraine. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Ajona, D.; Pérez-Rodríguez, A.; Goadsby, P.J. Gepants, calcitonin-gene-related peptide receptor antagonists: What could be their role in migraine treatment? Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2020, 33, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFalco, A.P.; Lazim, R.; Cope, N.E. Rimegepant Orally Disintegrating Tablet for Acute Migraine Treatment: A Review. Ann. Pharmacother. 2021, 55, 650–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Z. Efficacy and Safety of Rimegepant for the Acute Treatment of Migraine: Evidence From Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 10, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, R.B.; Blumenfeld, A.; Jensen, C.M.; Croop, R.; Thiry, A.; L’italien, G.; Morris, B.A.; Coric, V.; Goadsby, P.J. Efficacy of rimegepant for the acute treatment of migraine based on triptan treatment experience: Pooled results from three phase 3 randomized clinical trials. Cephalalgia 2023, 43, 3331024221141686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, R.; Goadsby, P.J.; Dodick, D.; Stock, D.; Manos, G.; Fischer, T.Z. BMS-927711 for the acute treatment of migraine: A double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled, dose-ranging trial. Cephalalgia 2014, 34, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, R.B.; Croop, R.; Stock, E.G.; Stock, D.A.; Morris, B.A.; Frost, M.; Dubowchik, G.M.; Conway, C.M.; Coric, V.; Goadsby, P.J. Rimegepant, an Oral Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide Receptor Antagonist, for Migraine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croop, R.; Goadsby, P.J.; Stock, D.A.; Conway, C.M.; Forshaw, M.; Stock, E.G.; Coric, V.; Lipton, R.B. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of rimegepant orally disintegrating tablet for the acute treatment of migraine: A randomised, phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, R.B.; Thiry, A.; Morris, B.; Croop, R. Efficacy and Safety of Rimegepant 75 mg Oral Tablet, a CGRP Receptor Antagonist, for the Acute Treatment of Migraine: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Pain Res. 2024, 17, 2431–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, X.; Niu, M.; Wei, Q.; Zhong, H.; Li, X.; Yuan, W.; Xu, W.; Zhu, S.; Yu, S.; et al. First real-world study on the effectiveness and tolerability of rimegepant for acute migraine therapy in Chinese patients. J. Headache Pain 2024, 25, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croop, R.; Berman, G.; Kudrow, D.; Mullin, K.; Thiry, A.; Lovegren, M.; L’italien, G.; Lipton, R.B. A multicenter, open-label long-term safety study of rimegepant for the acute treatment of migraine. Cephalalgia 2024, 44, 3331024241232944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Liao, X.; Wu, H.; Huang, Y.; Liang, T.; Li, H. Real-world study of adverse events associated with gepant use in migraine treatment based on the VigiAccess and U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s adverse event reporting system databases. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1431562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenschieber, E.; Blunck, D. Impact of reimbursement systems on patient care—A systematic review of systematic reviews. Health Econ. Rev. 2024, 14, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, R.B.; Fanning, K.M.; Serrano, D.; Reed, M.L.; Cady, R.; Buse, D.C. Ineffective acute treatment of episodic migraine is associated with new-onset chronic migraine. Neurology 2015, 84, 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Headache Type | |

|---|---|

| LFEM | 23 |

| HFEM | 9 |

| CM | 22 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 45 |

| Male | 9 |

| Age in years Mean ± standard deviation (min–max) | 45.3 ± 12.8 (19–69) |

| BMI | |

| Av. (min–max) | 24.5 (17.3–35.5) |

| Age at first migraine diagnosis | |

| Av. (min–max) | 21.2 (7–41) |

| History of triptan use | |

| Yes | 53 |

| No | 1 |

| No. of failed triptans | |

| 1 triptan, n (%) | 16 (29.6) |

| 2 triptans, n (%) | 16 (26.6) |

| 3 triptans, n (%) | 9 (16.7) |

| 4 triptans, n (%) | 3 (5.6) |

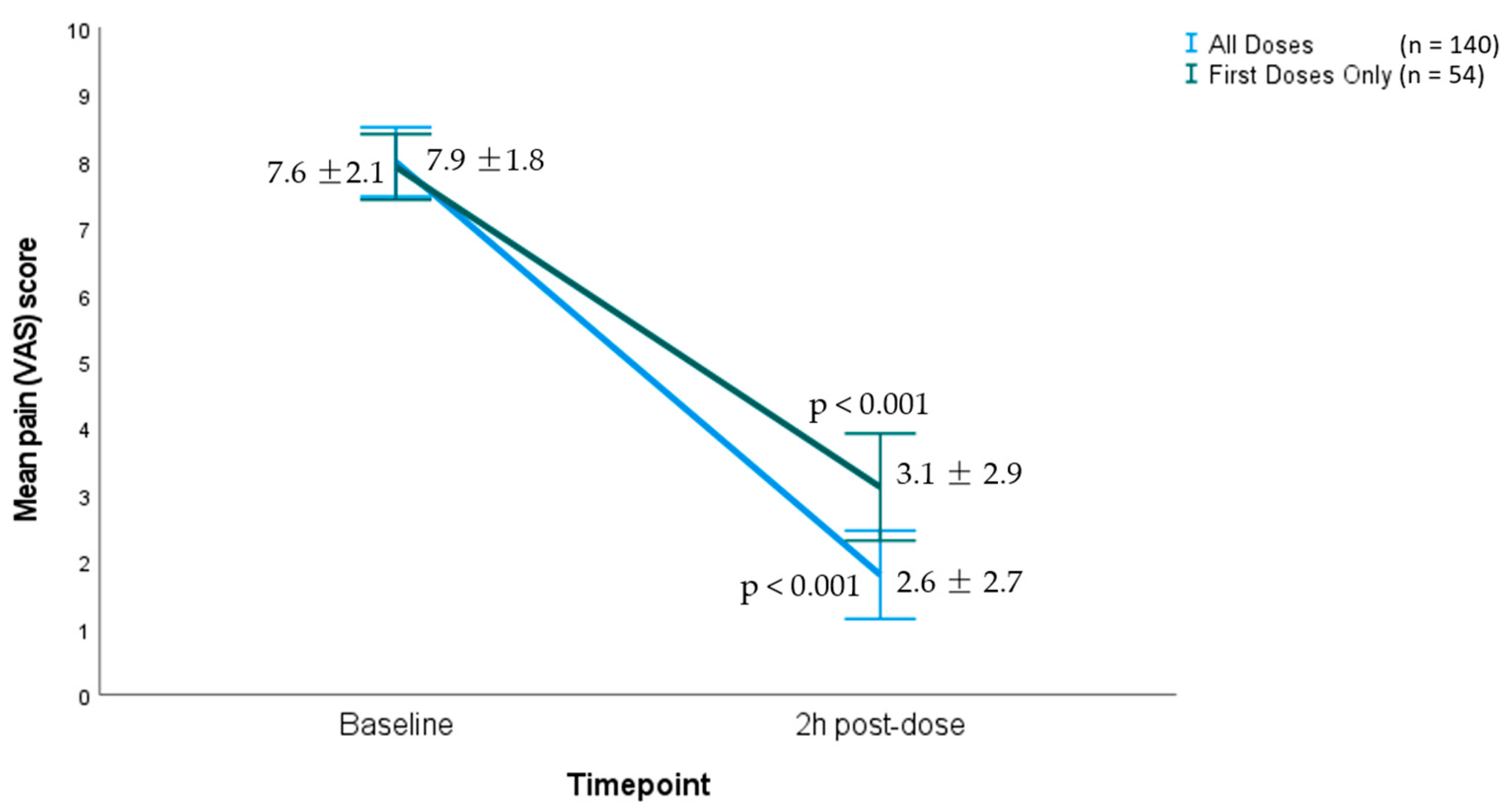

| Pre-Treatment | 2 h Post-Treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Change in pain VAS score (paired samples t-test) | Mean difference | ||

| Average in first dose (n = 54) | 7.9 (1.8) | 3.1 (2.9) | 4.8 (p < 0.001) |

| Average in all doses (n = 140) | 7.6 (2.1) | 2.6 (2.7) | 5 (p < 0.001) |

| Patients who had the symptom and became symptom-free at 2 h post-dose | |||

| Photophobia (n = 122) | |||

| No | 18 | 70 | 52 (43%) |

| Some | 26 | 54 | |

| Much | 32 | 7 | |

| Very much | 64 | 9 | |

| Phonophobia (n = 129) | |||

| No | 11 | 79 | 68 (53%) |

| Some | 33 | 46 | |

| Much | 33 | 14 | |

| Very much | 63 | 1 | |

| Nausea (n = 91) | |||

| No | 49 | 101 | 52 (57%) |

| Some | 31 | 27 | |

| Much | 38 | 9 | |

| Very much | 22 | 3 | |

| Response at 2 h (n = 140) | n (%) | ||

| <50% | 26 (19) | ||

| >50% | 37 (26) | ||

| >75% | 32 (23) | ||

| 100% (pain freedom) | 45 (32) | ||

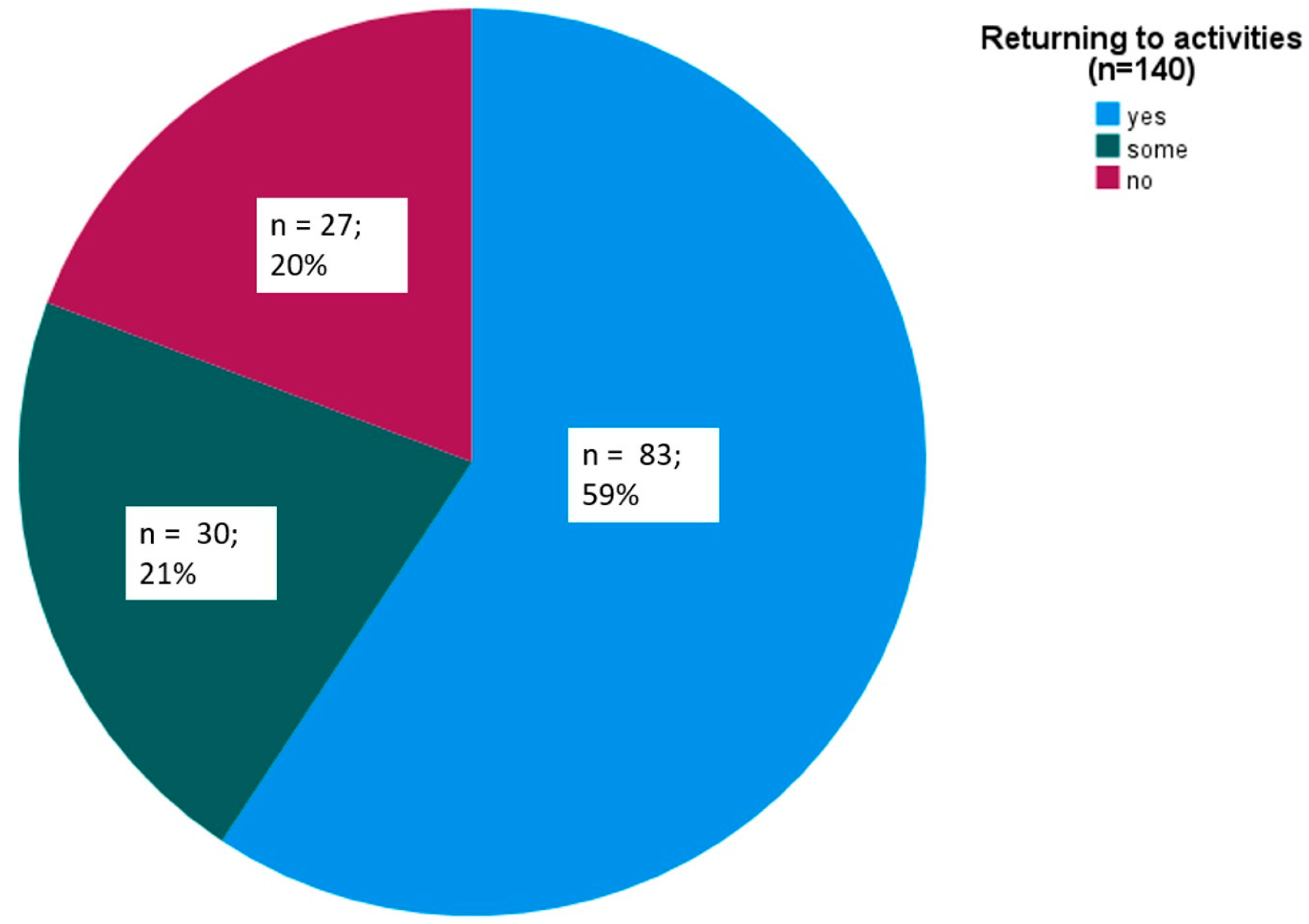

| Returning to everyday activities at 2 h (n = 140) | |||

| Yes | 83 (59) | ||

| Somewhat | 30 (21) | ||

| No | 27 (20) | ||

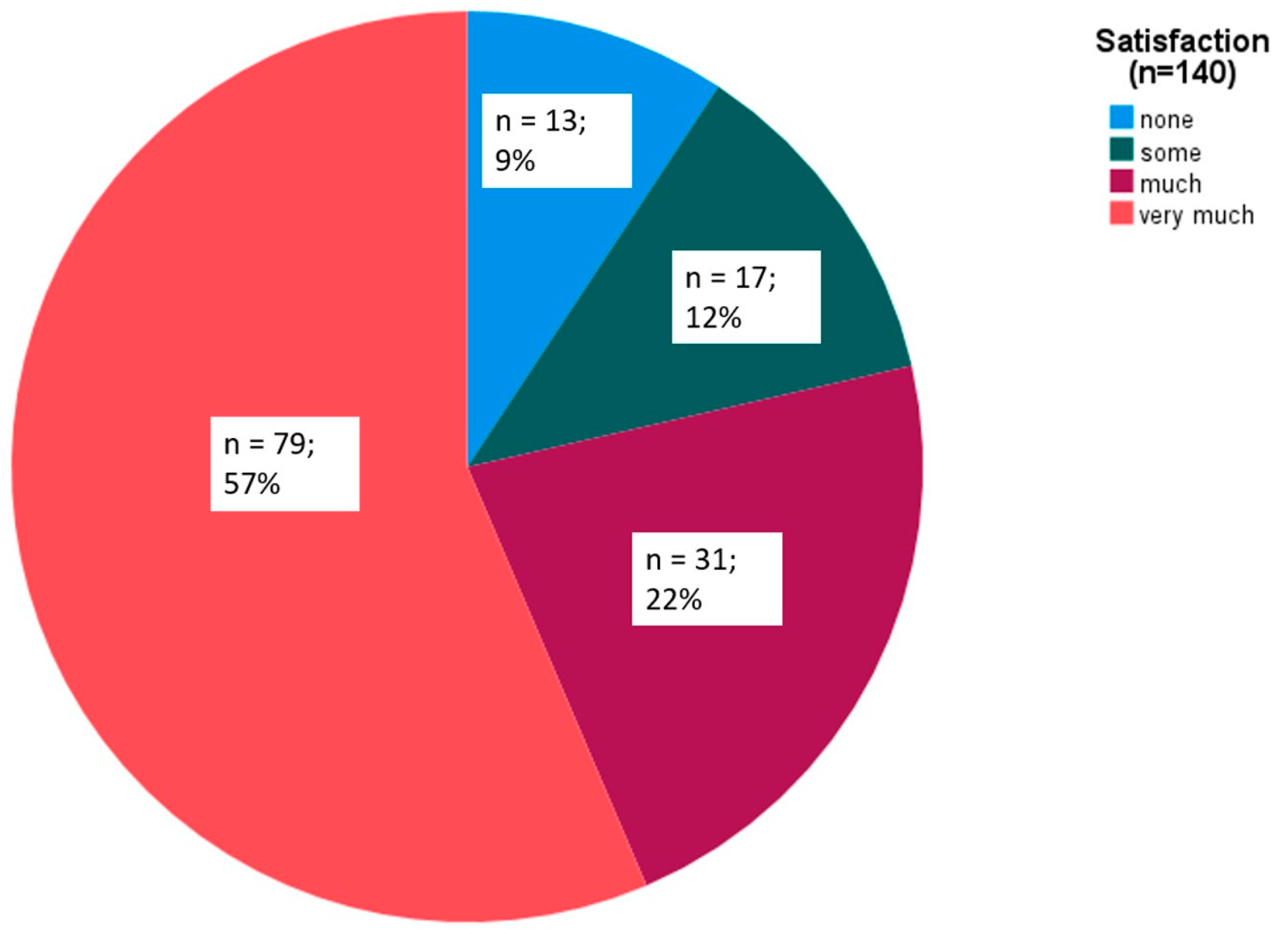

| Overall satisfaction at 2 h (n = 140) | |||

| Not at all | 13 (9) | ||

| Some | 17 (12) | ||

| Much | 31 (22) | ||

| Very much | 79 (57) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dermitzakis, E.V.; Rikos, D.; Vikelis, M.; Xiromerisiou, G.; Zisopoulou, S.; Rallis, D.; Soldatos, P.; Vlachos, G.S.; Vasiliadis, G.G.; Argyriou, A.A. Real-World Open-Label Experience with Rimegepant for the Acute Treatment of Migraine Attacks: A Multicenter Pilot Study. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 1169. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14121169

Dermitzakis EV, Rikos D, Vikelis M, Xiromerisiou G, Zisopoulou S, Rallis D, Soldatos P, Vlachos GS, Vasiliadis GG, Argyriou AA. Real-World Open-Label Experience with Rimegepant for the Acute Treatment of Migraine Attacks: A Multicenter Pilot Study. Brain Sciences. 2024; 14(12):1169. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14121169

Chicago/Turabian StyleDermitzakis, Emmanouil V., Dimitrios Rikos, Michail Vikelis, Georgia Xiromerisiou, Styliani Zisopoulou, Dimitrios Rallis, Panagiotis Soldatos, George S. Vlachos, Georgios G. Vasiliadis, and Andreas A. Argyriou. 2024. "Real-World Open-Label Experience with Rimegepant for the Acute Treatment of Migraine Attacks: A Multicenter Pilot Study" Brain Sciences 14, no. 12: 1169. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14121169

APA StyleDermitzakis, E. V., Rikos, D., Vikelis, M., Xiromerisiou, G., Zisopoulou, S., Rallis, D., Soldatos, P., Vlachos, G. S., Vasiliadis, G. G., & Argyriou, A. A. (2024). Real-World Open-Label Experience with Rimegepant for the Acute Treatment of Migraine Attacks: A Multicenter Pilot Study. Brain Sciences, 14(12), 1169. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14121169