Efficacy and Safety of Clonidine in the Treatment of Acute Mania in Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategies

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Methodological Quality and Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

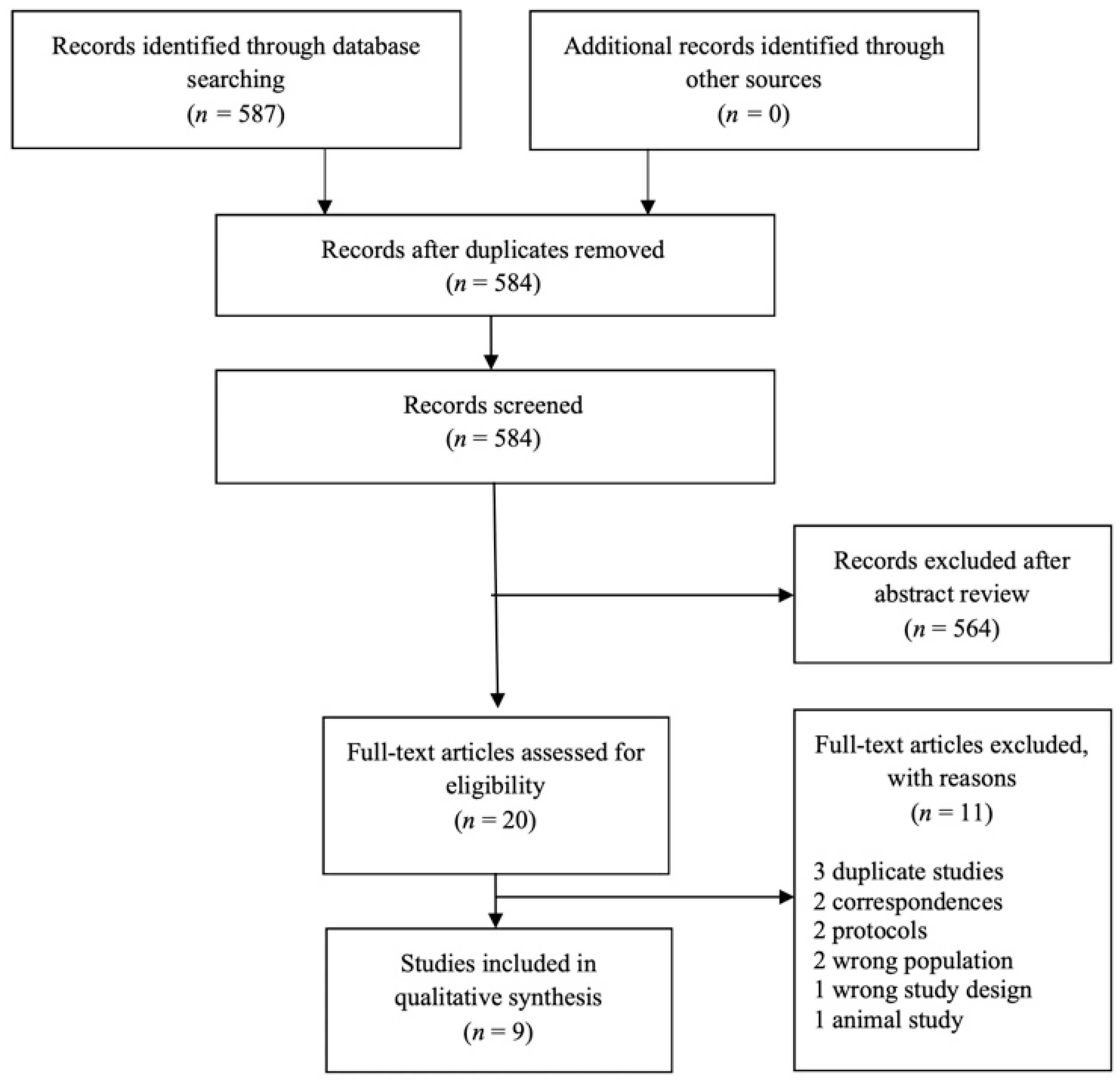

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.3. Randomized Controlled Trials: Five Studies (n = 159)

3.3.1. Clonidine vs. Placebo

3.3.2. Clonidine vs. Control (Lithium or Verapamil; n = 44)

3.4. Non-Randomized Studies (n = 63)

3.5. Adverse Events

3.6. Dropouts

3.7. Methodological Quality and Risk of Bias Assessment

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary and Interpretation of Findings

4.2. Strengths and Limitations:

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clemente, A.S.; Diniz, B.S.; Nicolato, R.; Kapczinski, F.P.; Soares, J.C.; Firmo, J.O.; Castro-Costa, É. Bipolar disorder prevalence: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2015, 37, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merikangas, K.R.; Jin, R.; He, J.-P.; Kessler, R.C.; Lee, S.; Sampson, N.A.; Viana, M.C.; Andrade, L.H.; Hu, C.; Karam, E.G. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011, 68, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, F.K.; Jamison, K.R. Manic-Depressive Illness: Bipolar Disorders and Recurrent Depression; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Elsayed, O.H.; Ercis, M.; Pahwa, M.; Singh, B. Treatment-Resistant Bipolar Depression: Therapeutic Trends, Challenges and Future Directions. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2022, 18, 2927–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdick, K.E.; Millett, C.E.; Yocum, A.K.; Altimus, C.M.; Andreassen, O.A.; Aubin, V.; Belzeaux, R.; Berk, M.; Biernacka, J.M.; Blumberg, H.P.; et al. Predictors of functional impairment in bipolar disorder: Results from 13 cohorts from seven countries by the global bipolar cohort collaborative. Bipolar Disord. 2022, 24, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieta, E.; Berk, M.; Schulze, T.G.; Carvalho, A.F.; Suppes, T.; Calabrese, J.R.; Gao, K.; Miskowiak, K.W.; Grande, I. Bipolar disorders. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2018, 4, 18008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatham, L.N.; Kennedy, S.H.; Parikh, S.V.; Schaffer, A.; Bond, D.J.; Frey, B.N.; Sharma, V.; Goldstein, B.I.; Rej, S.; Beaulieu, S. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018, 20, 97–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntyre, R.S.; Berk, M.; Brietzke, E.; Goldstein, B.I.; López-Jaramillo, C.; Kessing, L.V.; Malhi, G.S.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Rosenblat, J.D.; Majeed, A. Bipolar disorders. Lancet 2020, 396, 1841–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, S.M.; Laredo, S.; Morrissette, D.A. Cariprazine as a treatment across the bipolar I spectrum from depression to mania: Mechanism of action and review of clinical data. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 10, 2045125320905752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skonieczna-Żydecka, K.; Łoniewski, I.; Misera, A.; Stachowska, E.; Maciejewska, D.; Marlicz, W.; Galling, B. Second-generation antipsychotics and metabolism alterations: A systematic review of the role of the gut microbiome. Psychopharmacology 2019, 236, 1491–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunney, W.E. Jr The current status of research in the catecholamine theories of affective disorders. Psychopharmacol. Commun. 1975, 1, 599–609. [Google Scholar]

- Manji, H.K.; Quiroz, J.A.; Payne, J.L.; Singh, J.; Lopes, B.P.; Viegas, J.S.; Zarate, C.A. The underlying neurobiology of bipolar disorder. World Psychiatry 2003, 2, 136. [Google Scholar]

- Rihmer, Z.; Gonda, X.; Dome, P. Is mania the hypertension of the mood? Discussion of a hypothesis. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2017, 15, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, M.-C.; Lecrubier, Y.; Widlöcher, D. Efficacy of clonidine in 24 patients with acute mania. Am. J. Psychiatry 1986, 143, 1450–1453. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tudorache, B.; Diacicov, S. The effect of clonidine in the treatment of acute mania. Rev. Roum. Neurol. Et Psychiatr. 1991, 29, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubenko, G.S.; Cohen, B.M.; Lipinski, J.F.; Jonas, J.M. Clonidine in the treatment of mania and mixed bipolar disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 1984, 141, 1617–1618. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Naguy, A. Clonidine use in psychiatry: Panacea or panache? Pharmacology 2016, 98, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, S.M. Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Practical Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yasaei, R.; Saadabadi, A. Clonidine. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Isaac, L. Clonidine in the central nervous system: Site and mechanism of hypotensive action. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1980, 2, S5–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fava, M. The promise and challenges of drug repurposing in psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2018, 17, 28–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadpanah, M.; Pezeshki, R.; Soltanian, A.R.; Jahangard, L.; Dürsteler, K.M.; Keshavarzi, A.; Brand, S. Influence of adjuvant clonidine on mania, sleep disturbances and cognitive performance—Results from a double-blind and placebo-controlled randomized study in individuals with bipolar I disorder during their manic phase. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 146, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, W-65–W-94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savović, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slim, K.; Nini, E.; Forestier, D.; Kwiatkowski, F.; Panis, Y.; Chipponi, J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS): Development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J. Surg. 2003, 73, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, B.; Parsaik, A.K.; Ahmed, A.T.; Erwin, P.J.; Singh, B. A systematic review on the efficacy of intravenous racemic ketamine for bipolar depression. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 41, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Nuñez, N.A.; Prokop, L.J.; Veldic, M.; Betcher, H.; Singh, B. Association of optimal lamotrigine serum levels and therapeutic efficacy in mood disorders: A systematic review. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 41, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janicak, P.; Sharma, R.; Easton, M.; Comaty, J.; Davis, J. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of clonidine in the treatment of acute mania. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1989, 25, 243–245. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy-Bayle, M.; Lecrubier, Y.; Lancrenon, S.; Laine, J.; Allilaire, J.; Des Lauriers, A. Clonidine versus a placebo trial in manic disorder. L’encephale 1989, 15, 523–526. [Google Scholar]

- Giannini, A.J.; Loiselle, R.H.; Price, W.A.; Giannini, M.C. Comparison of antimanic efficacy of clonidine and verapamil. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1985, 25, 307–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, A.J.; Pascarzi, G.A.; Loiselle, R.H.; Price, W.A.; Giannini, M.C. Comparison of clonidine and lithium in the treatment of mania. Am. J. Psychiatry 1986, 143, 1608–1609. [Google Scholar]

- Jouvent, R.; Lecrubier, Y.; Puech, A.; Simon, P.; Widlöcher, D. Antimanic effect of clonidine. Am. J. Psychiatry 1980, 137, 1275–1276. [Google Scholar]

- Giannini, A.J.; Extein, I.; Gold, M.S.; Pottash, A.; Castellani, S. Clonidine in mania. Drug Dev. Res. 1983, 3, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech, P.; Rafaelsen, O.J.; Kramp, P.; Bolwig, T.G. The mania rating scale: Scale construction and inter-observer agreement. Neuropharmacology 1978, 17, 430–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celano, C.M.; Freudenreich, O.; Fernandez-Robles, C.; Stern, T.A.; Caro, M.A.; Huffman, J.C. Depressogenic effects of medications: A review. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2022, 13, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, B. Clinical Trial Designs. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2019, 10, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schildkraut, J.J. The catecholamine hypothesis of affective disorders: A review of supporting evidence. Am. J. Psychiatry 1965, 122, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartoli, F.; Cavaleri, D.; Bachi, B.; Moretti, F.; Riboldi, I.; Crocamo, C.; Carrà, G. Repurposed drugs as adjunctive treatments for mania and bipolar depression: A meta-review and critical appraisal of meta-analyses of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 143, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langer, S.Z. Presynaptic regulation of catecholamine release. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1974, 23, 1793–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehrich, H.; Gold, M. Propranolol as adjunct to clonidine in opiate detoxification. Am. J. Psychiatry 1987, 144, 1099–1100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Author, Year, Country | Study Type | Control Group n (Male %) | Clonidine Group n (Male %) | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Age in Years (Mean ± SD) | Outcome Measures | Study Duration (Days) | Dose of Clonidine | Concomitant Medications Allowed | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jouvent et al., 1980 [32], France | Open Label | NA | 8 (62.5) | Adult patients diagnosed with mania or hypomania | Not mentioned | 50.5 ± 16.2 | Bech MRS; Mean score = 23.5 ± 5.4 | 7 | 0.15–0.45 mg/day | Diazepam, Chlorpromazine, Droperidol, Lithium | Clonidine showed antimanic effects. Insomnia, hypotension, and depression were the common side-effects. |

| Giannini et al., 1983 [33], US | Non-Randomized | NA | 11 (54.5) | Research Diagnostic Criteria for mania and hypomania | Concomitant use of psychotropic medication | 28 ± 1 | Biegel-Murphy MSRS; Mean score = 219 ± 26 | 25 | 17 µg/kg/day | NA | Clonidine showed antimanic effects. Relapse observed in patients who discontinued clonidine. Sedation and hypotension were the common side-effects. |

| Giannini et al., 1985 [30], US | RCT | Verapamil 10 (100) | 10 (100) | Adult DSM III for manic episode. Unsatisfactory response to lithium. | Not mentioned | NA | BPRS; Mean score = NA | 45 | 17 µg/kg/day | NA | 60% of patients improved with verapamil. Verapamil was superior to clonidine. Hypotension was a prominent side-effect with clonidine. |

| Giannini et al., 1986 [31], US | RCT | Lithium 12 (100) | 12 (100) | Adult DSM III for manic episode. Previous episodes responded to lithium. | Not mentioned | NA | BPRS; Mean score = 1.27 ± 1.02 (lithium); 1.17 ± 1.28 (clonidine) | 75 | 17 µg/kg/day | NA | Lithium showed superior efficacy than clonidine at 30 days. No differences in orthostatic hypotension between groups. |

| Hardy et al., 1986 [14], France | Open Label | NA | 24 (41.7) | Adult DSM III for manic episode. All BD | Rapid cycling; hypomanic | 47 ± 19 | Bech MRS; Mean score = 26.8 ± 7.1 | 14 | 0.45–0.9 mg/day | Lithium, Droperidol | Clonidine showed antimanic effects and an earlier response predicted final outcome. Good tolerability (mild sedation). four patients had worsening of agitation symptoms at higher dose (0.75–0.9 mg). |

| Janicak et al., 1989 [28], US | RCT | Placebo 9 (NA) | 12 (NA) | Adult in-patients diagnosed with BPAD, manic or mixed phase illness according to DSM-III | At least 30% worsening of symptoms on BPRS; intolerable side effects; uncooperative patients | 32 ± 18 | BPRS, 9-item mania scale; mean BPRS scale = 44.4 ± 10, mean mania scale = 26.6 ± 6 | 14 | 0.2–0.8 mg/day | NA | No significant differences between groups. Clonidine had a higher dropout rate |

| Hardy et al., 1989 [29], France | RCT | Placebo 12 (25) | 12 (25) | Adult DSM III for manic or hypomanic episode. | Patients treated with hypertensive agents and associated treatments. Rapid cyclers. | 40.8 ± 16.2 (Clonidine group) 30.8 ± 13.6 (Placebo group) | CGS | 14 | 0.25–0.9 mg/day | Droperidol | No significant differences between groups. |

| Tudorache and Diacicov, 1991 [15], Romania | Open Label | NA | 20 (40) | Adult in-patients diagnosed with mania according to DSM-III | Rapid cycling; hypomanic | 42 ± 18 | Bech MRS; Mean score = 32.4 ± 6.1 | 30 | 0.45–0.75 mg/day | Lithium, Haloperidol | Clonidine was efficacious as an antimanic agent. Hypotension was reported in one patient. |

| Ahmadpanah et al., 2022 [22], Iran | RCT | Placebo 34 (82.3) | 36 (86.1) | 18–65years of age; Diagnosed with BPAD according to DSM-5; YMRS > 20; At least one hospitalization for BPAD in past 2 years | Known allergies against lithium/alpha-2-adrenergic receptor stimulant drugs. Suicide attempt within the last 8 weeks. Risk of suicide attempt; h/o other psychiatric illness Current use of anticholinergic drugs or TCAs. Females: Pregnant, breastfeeding or planning to become pregnant | 37.4 ± 11.75 | YMRS; Mean score = 28.21 ± 5.89 | 24 | 0.2–0.6 mg/day | Lithium, Sodium Valproate, Antipsychotic | Adjuvant clonidine with lithium significantly improved mania and subjective sleep quality more than placebo, but not cognitive performance. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Singal, P.; Nuñez, N.A.; Joseph, B.; Hassett, L.C.; Seshadri, A.; Singh, B. Efficacy and Safety of Clonidine in the Treatment of Acute Mania in Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic Review. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 547. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13040547

Singal P, Nuñez NA, Joseph B, Hassett LC, Seshadri A, Singh B. Efficacy and Safety of Clonidine in the Treatment of Acute Mania in Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic Review. Brain Sciences. 2023; 13(4):547. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13040547

Chicago/Turabian StyleSingal, Prakamya, Nicolas A. Nuñez, Boney Joseph, Leslie C. Hassett, Ashok Seshadri, and Balwinder Singh. 2023. "Efficacy and Safety of Clonidine in the Treatment of Acute Mania in Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic Review" Brain Sciences 13, no. 4: 547. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13040547

APA StyleSingal, P., Nuñez, N. A., Joseph, B., Hassett, L. C., Seshadri, A., & Singh, B. (2023). Efficacy and Safety of Clonidine in the Treatment of Acute Mania in Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic Review. Brain Sciences, 13(4), 547. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13040547