1. Introduction

Pharmacological evaluation of medicinal plants has recently witnessed a growing interest amongst researchers worldwide. Research on the therapeutic potential of plants has surged over the years, with volumes of scientifically documented information showing considerable potential for medicinal plants to be used in the treatment of several diseases [

1]. However, while voluminous pharmacological studies have been conducted to ascertain the subjective traditional uses of various medicinal plants, very few plants have been thoroughly evaluated for their detrimental effect. Reports of efficacy are, by far, more numerous than those on toxicity [

2,

3]. There is, therefore, a need to further the investigation of herbal remedies and phytochemicals to incorporate the observations of short and long-term toxicity manifestations and to ensure effectual open communication of such findings.

Alstonia scholaris, a species of the family Apocyanaceae, has been widely studied for its numerous pharmacological properties [

4]. It is native to the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia.

A. scholaris has been investigated for its anti-inflammatory, analgesic [

5], antidiabetic, antihyperlipidemic [

6], anti-malarial [

7], and anti-microbial effects [

8], in addition to it theraputic potential against other diseases. Boiled decoctions of this herb have been reported to treat several diseases, such as asthma, hypertension, lung cancer and pneumonia; and also as remedies for fever [

9,

10,

11]. The present study evaluates the acute and subacute oral toxicity of the methanol extract of

Alstonia scholaris in experimental animals.

4. Discussion

Considering the numerous therapeutic potentials of

Alstonia scholaris as an alternative medicine effective for a wide range of diseases and infections, as reported in a number of scientific papers [

21], it is only pertinent that a safety profile of the plant be established as a guide for the management of its applications and usage in herbal preparations. This should serve to prevent exposing human subjects to potential toxicity-related health risks while using

A. scholaris. Toxicity studies in appropriate animal models are commonly used to assess potential health risks in humans. Such toxicity studies assess the hazard and determine the risk level by addressing the probability of exposure to that particular hazard at certain doses or concentrations [

22].

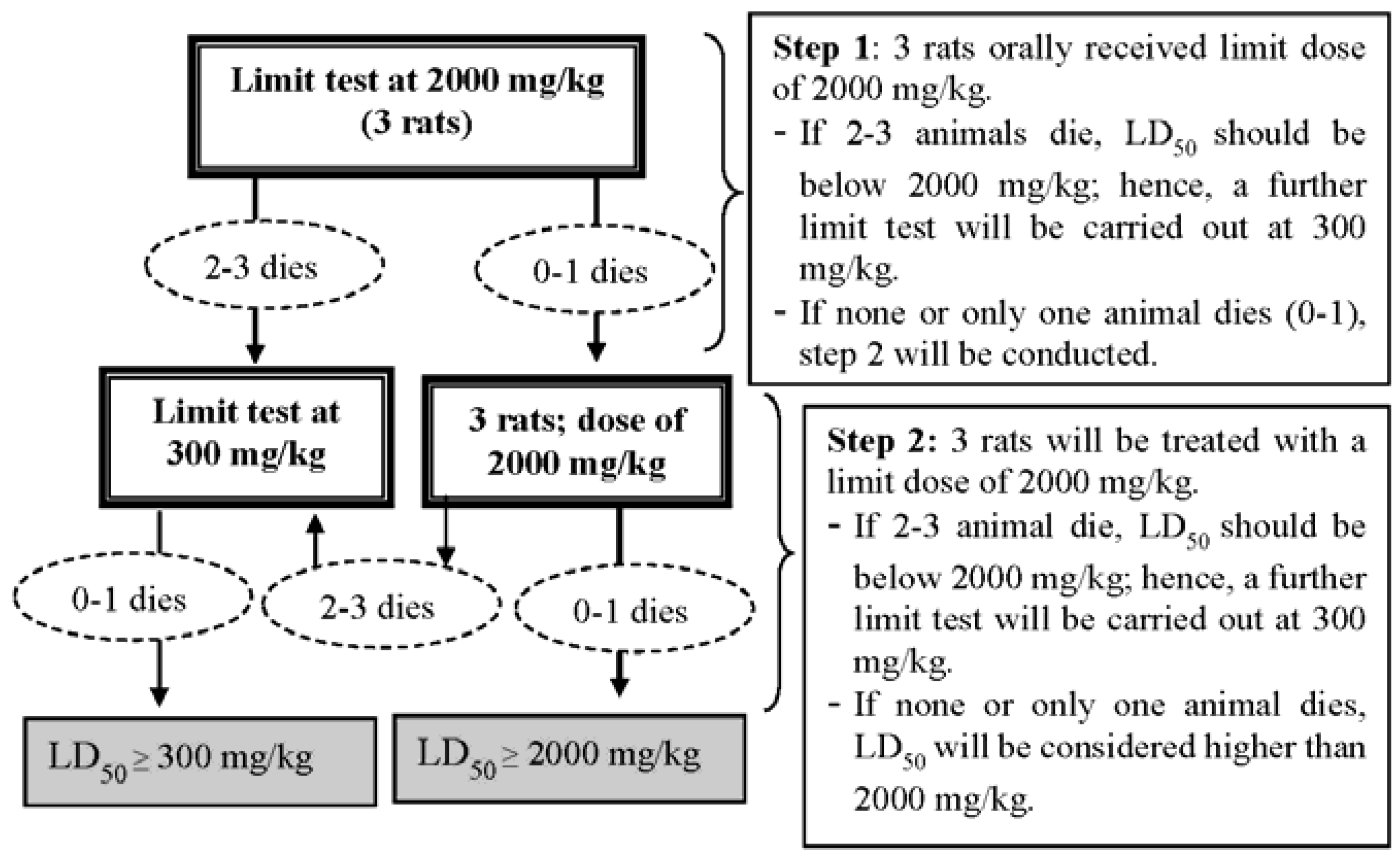

In the present study, single-dose oral administration of ASME in female rats at 2000 mg/kg b.w. had no effects on mortality, examined clinical signs, body weight or overall observation. Therefore, no acute toxicity was found in rats treated with ASME and the approximate lethal dose was determined to be higher than 2000 mg/kg. Yet, the lack of toxicity-indicative manifestations upon acute oral administration of ASME can be attributed to sub-sufficient absorption of the extract in the gastrointestinal tract, or a high first-pass metabolism rate in the liver, by which toxic components would have been converted to their harmless derivatives. Nonetheless, the knowledge gained from our acute toxicity study may serve for choosing more appropriately the test doses of A. scholaris extracts for later chronic or sub-chronic toxicity studies to report results of greater clinical relevance—as was the case in the present investigation.

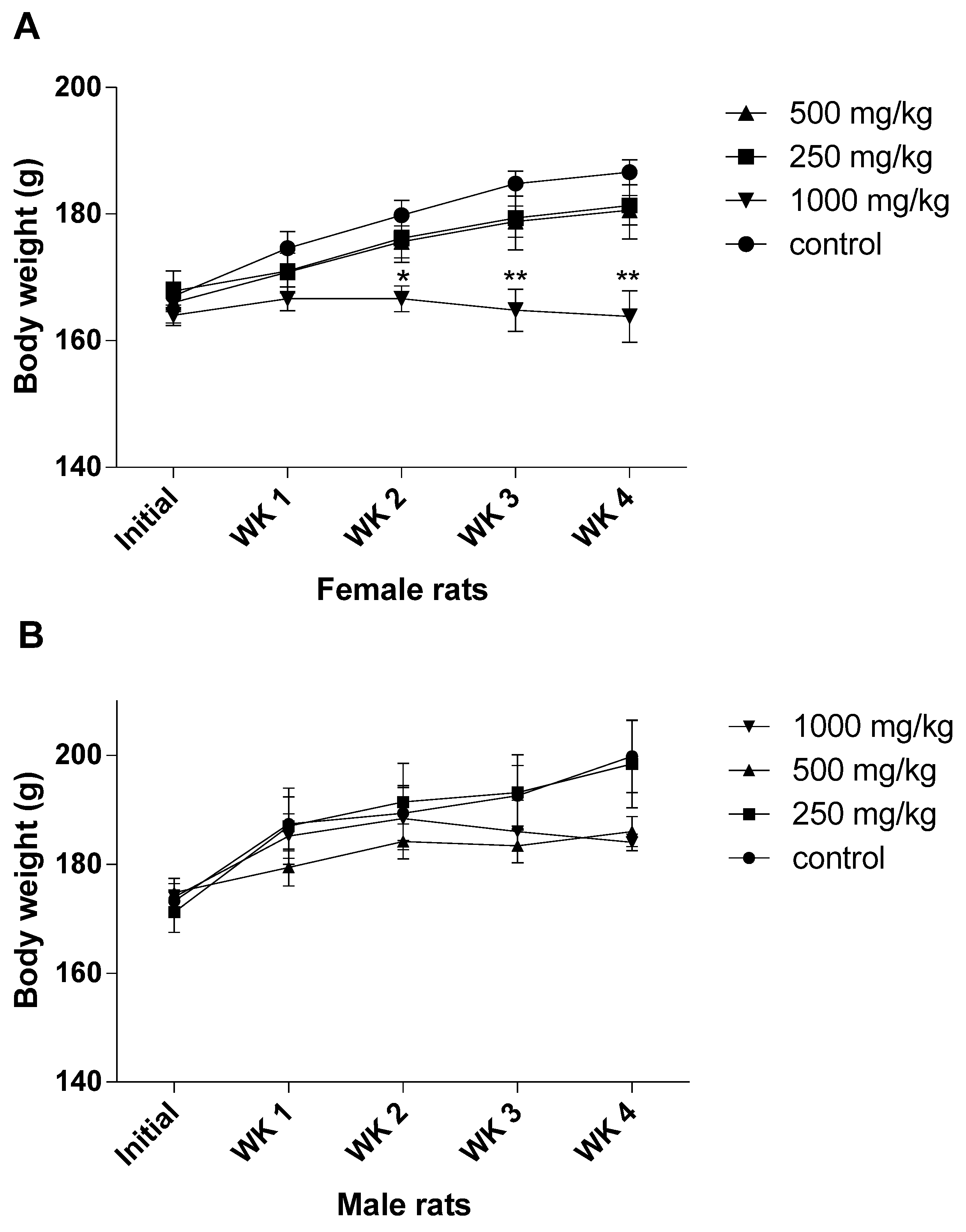

The sub-acute toxicity study, which involved rats given ASME orally at doses of 250, 500 and 1000 mg/kg b.w., demonstrated significant changes in animal behavior, as well as significant reductions in body weight in both male and female rats at high doses (500 and 1000 mg/kg b.w.). Similarly, it was also observed that, with the exception of the lungs, no significant differences were found in the organ weights of the treated rats in comparison with the control groups. It goes without saying that a decrease in body weight may be an indicator of adverse effects [

23,

24]. The liver and the kidneys are target organs for toxic chemicals due to their essential functions in bodily detoxification and excretion processes. Thus, they are considered highly useful in toxicity studies because of their sensitivity to harmful compounds and their potential to predict toxicity. Toxicity-related changes in the weights of these vital organs are often accompanied by corresponding histopathological findings. Changes in the weight of the lungs have less toxicity implications due to the lungs’ limited role in the removal of harmful substances from the body [

25,

26]. Therefore, it could safely be claimed that the liver and the kidneys could serve as the primary target organs in investigations related to the sub-acute oral toxicity of a herbal extract.

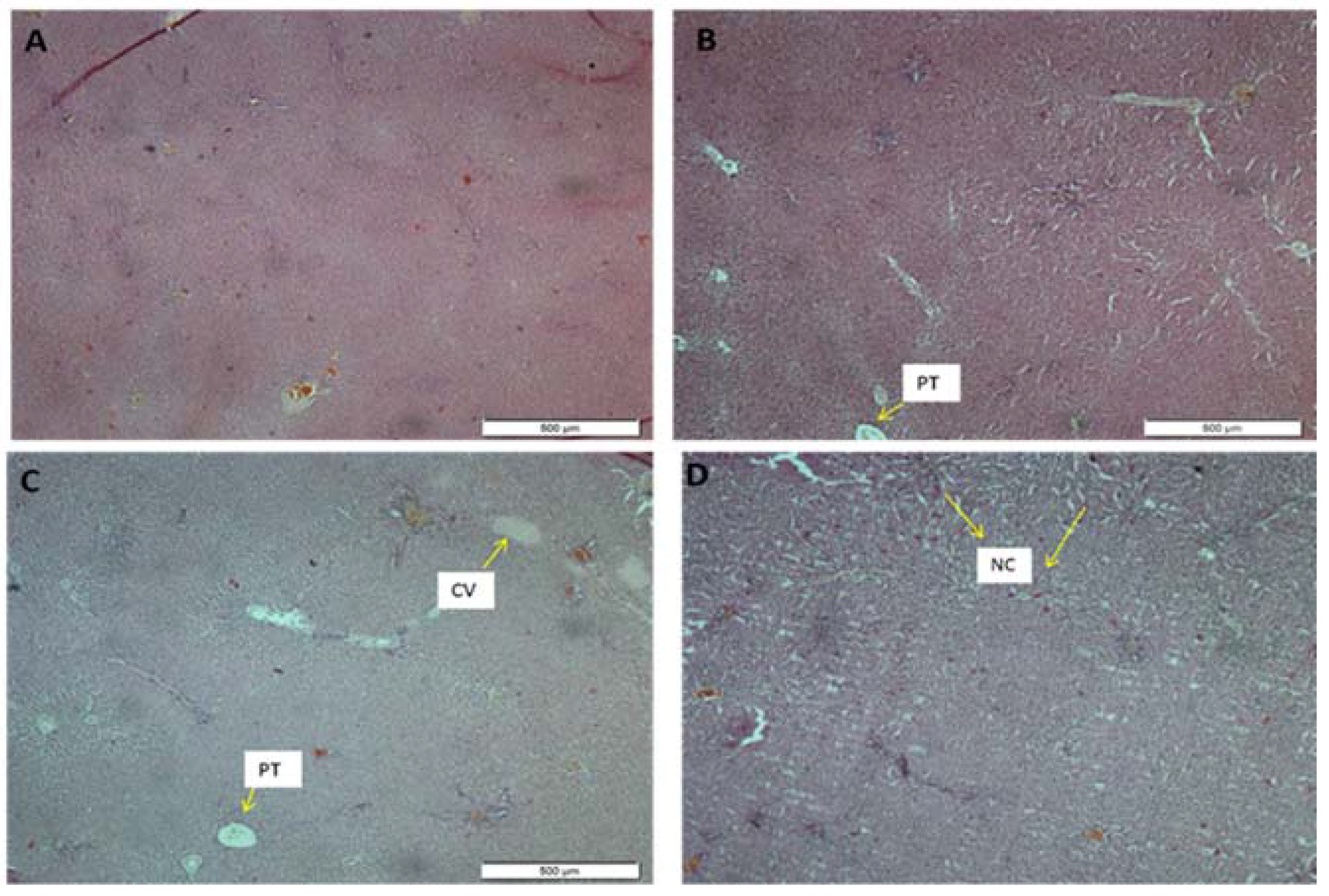

The histological features of the liver in this study were displayed in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 for the female and the male rats, respectively. The morphology of the hepatic cells in both the male and the female control groups was normal. However, in the extract-treated group, severe morphological alterations in the structure were observed, which was most expressed in the highest-dose group. Furthermore, histological evaluation showed occasional centrilobular necrosis [

27]. It was also observed that the central vein in the groups treated with ASME had been enlarged, an effect which could lead to congestive hepatopathy [

28].

Analysis of blood parameters in animal toxicity studies is important to report alterations in those parameters and evaluate the relative risk to the hematopoietic system when extrapolating those findings to humans [

29,

30]. Determining certain blood biochemical parameters and investigating major toxic effects on specific tissues, specifically the kidneys and the liver, may provide useful information regarding the mechanisms of toxicity of an otherwise safe and therapeutic agent [

31]. Significant increases in the levels of some biochemical parameters, particularly ALP and AST, were observed in both the male and the female rats treated with ASME, as compared with the respective controls. ALT levels were mildly reduced in the female treated rats, but they were significantly altered in the male ones which received the doses of 250 and 1000 mg/kg b.w. Due to its distinctive abundance in the cytoplasm of liver cells, ALT has been commonly used as a marker to quantify suspected liver cell damage [

32,

33]. AST is more ubiquitous in nature. Besides making up 80% and 20% of the total intracellular enzymes in hepatic mitochondria and cytoplasm, respectively, it is found in the heart, skeletal muscle, kidneys, brain, pancreas and blood cells [

34,

35]. To state another observation, mild and statistically-insignificant increases in serum albumin, total protein, globulin and bilirubin were observed in the male, rather than the female, animals of the highest-dose group. These findings could signal mild degeneration and the presence of lesions, which was confirmed by histopathological examination of the livers of the animals in the highest-dose group. These results suggest that ASME may have altered few hepatic functions and indicate that the rats’ livers in the highest-dose group may have been injured upon sub-acute administration.

Abnormally high levels of serum creatinine, uric acid and urea are biomarkers of possible malfunction of the kidneys [

36]. In this study, both urea and creatinine levels were marginally altered in both the male and the female treated rats compared with their respective controls. Nevertheless, the values were within the normal ranges of these parameters, which ruled out the possibility of precipitated abnormalities. Thus, these findings suggest that ASME does not affect the normal kidney function.

In regards to the observed hematological values, most of the values shown in the treated groups were normal in comparison with the control group. Yet, some values were significantly different from those of the control group, such as those pertaining to hemoglobin, RBC, MCV and MCHC. Reductions in these indices indicated that the extract interfered with the normal production of Hb and its concentrations within RBCs. Thus, it should be concluded that ASME may possess the potential to induce anemia [

37]. Moreover, the observed reductions in WBC, including lymphocytes, monocytes, and eosinophils, and platelets counts may suggest a decline in the function of the immune system. Therefore, these results suggest that the extract has a tendency to cause anemia and immunological defects in rats, rendering the animals more vulnerable to infections. It was also evident that the hematological values were more altered in the female, rather than the male, treated rats.

The lipid profiles of the treated rats demonstrated significantly increased HDL levels, which corresponded to mild decreases in LDL levels. HDL is known to be the good cholesterol in the body as it facilitates the prevention of cardiovascular risk factors. Therefore, the observation herein further confirmed the reported antidiabetic and antihyperlipidemic activities of

Alstonia scholaris [

6], even though TC, TG and glucose levels were not significantly changed in the animals treated with ASME in this study when compared to the control group.

The death of two female rats indicate gender sensitivity of the toxic effect. However, this contradicts the previous findings by Baliga

et al. [

38] where the male rats are reported to be more susceptible to the toxic effect of the extract. Another difference is the variation in the lethal (LD

50) dose; while the previous study [

38], a sub-chronic toxicity study, showed that an oral dose of 240 mg/kg of ethanol extract of

Alstonia scholaris bark collected in the monsoon season in India is highly toxic, in this current study, 250 mg/kg of the methanol extract was found to be non-toxic for 28-day oral administration. Ecological and environmental factors such as seasonal variation in rainfall and extraction process used on the plant sample are known to affect the phytoconstituents in any given species as much as the biological factors [

39]. Thus, it is plausible that the disparity is the toxic effect may be due to differences in geographical location, collection time of the plants samples and the extraction procedure. Evidently,

Alstonia scholaris bark extract collected during the summer period showcased a less toxic effect.

A limiting factor in this study was the lack of certainty as to whether the plant sample used could serve as a prototype of

Alstonia scholaris species. Plant identification was based on morphological features; taxonomical data and other regional pharmacopeia information were used for validation at USM Herbarium Unit. Secondly, chemical characterization of the plant material was not conducted. Nonetheless, the toxic of

Alstonia scholaris has previously been attributed to echitamine [

38] which has been reported to exert a cytotoxic effect on cell lines [

40]. Hence, although this work may serve as a template for future animal studies, and provide guidelines pertaining to the provincial use of

Alstonia scholaris by Asian patients, considering the lack of any chemical characterization, the present results might not be comparable to any future studies utilizing this same plant species.