Research on the Impact of Regional-Scale Soil Mechanics Parameter Disturbances on Rainfall Landslides Warning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method and Data

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Soil Sample and Soil Direct Tests

2.3. Distribution Characteristics of Mechanical Parameters in Different Lithological Zones

2.3.1. Distribution Characteristics of Mechanical Parameters Under Liquid Limit and Plastic Limit of Different Lithological Zones

2.3.2. Distribution Characteristics of Mechanical Parameters Under Different Disturbance Conditions

2.4. Calculation of HSU Instability Probability Under Each Disturbance Condition

2.4.1. The Extraction of HSUs

2.4.2. The Safety Factor Fs Calculation of HSUs

2.4.3. The Hydrological Simulation Process

2.4.4. The Calculation of Instability Probability of the HSUs

2.5. Rainfall Data

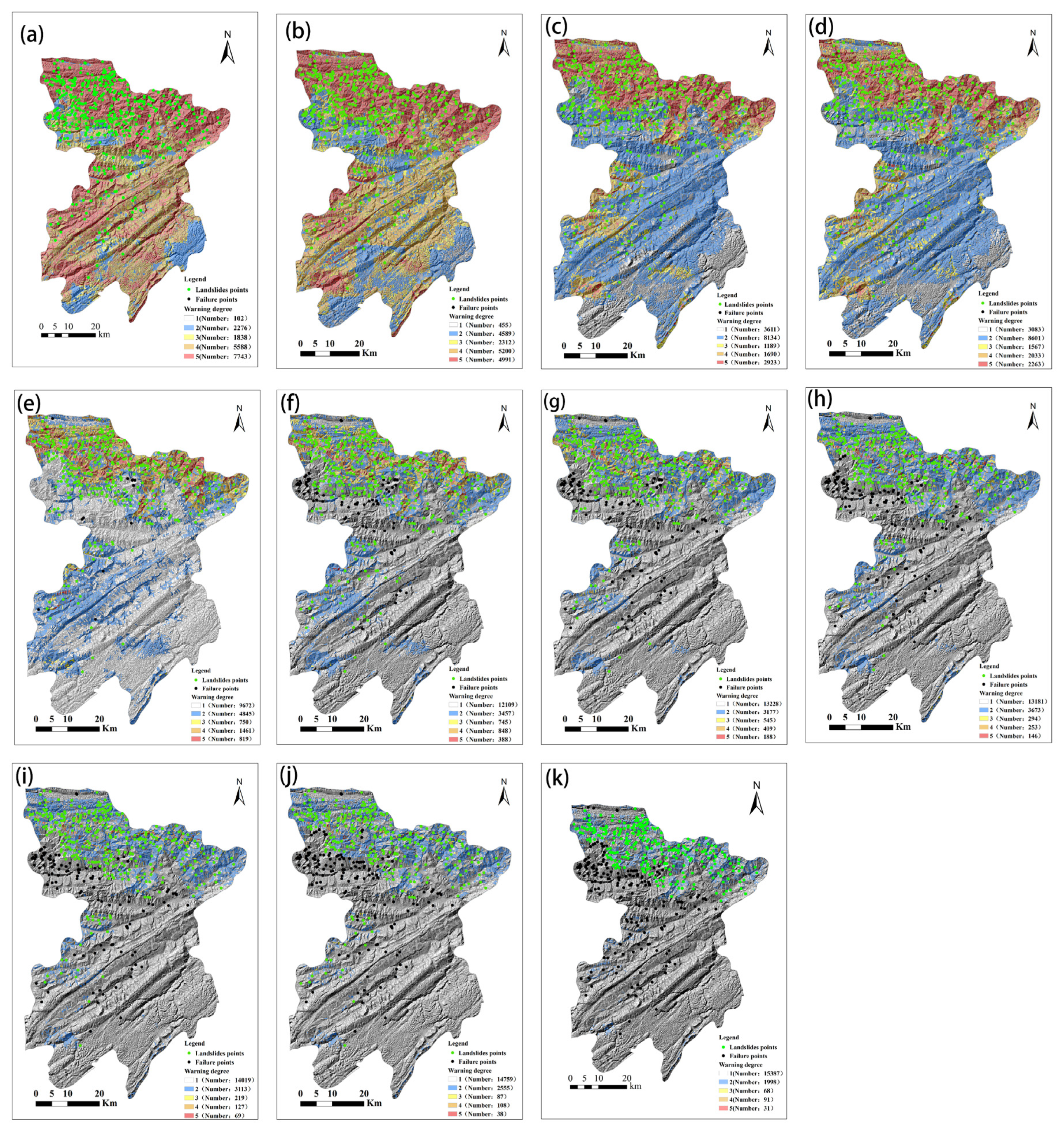

3. Application: “8.31” Rainfall-Induced Landslide Forecast

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, C.W.; Tung, Y.S.; Liou, J.J.; Li, H.C.; Cheng, C.T.; Chen, Y.M.; Oguchi, T. Assessing landslide characteristics in a changing climate in northern Taiwan. Catena 2019, 175, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Shen, J.H.; Li, Y.; Duan, W.F.; Yang, R.C.; Shu, J.C.; Li, H.W.; Tao, S.Y.; Zheng, S.Z. Mechanism of colluvial landslide induction by rainfall and slope construction: A case study. J. Mt. Sci. 2021, 18, 1013–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Victor, C.; Duan, M. Research on the rainfall-induced regional slope failures along the Yangtze River of Anhui, China. Landslides 2021, 18, 1801–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yin, K.; Du, J.; Chen, L.; Xie, X.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, X. Landslides triggered by the extreme rainfall on July 4, 2023, Wanzhou, China. Landslides 2024, 22, 2935–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, X.; Hu, S.; Wang, D.; Lian, B.; Xue, C.; Liu, K. Controlling effect of sliding zone soil on rainfall-triggered colluvial landslide in Qinling-Bashan Mountains—A typical case study. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2025, 50, e70134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, M.; Lazzari, M. A kernel density estimation approach for landslide susceptibility assessment. In Proceedings of the International Conference on “Mountain Risks: Bringing Science to Society”, Florence, Italy, 24–26 November 2010; pp. 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Lazzari, M.; Danese, M. A multitemporal kernel density estimation approach for new triggered landslide forecasting and susceptibility assessment. Disaster Adv. 2012, 5, 100–108. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, S.; Lari, S. Regional landslide susceptibility zoning with considering the aggregation of landslide points and the weights of factors. Landslides 2014, 11, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezak, N.; Šraj, M.; Mikoš, M. Copula-based IDF curves and empirical rainfall thresholds for flash floods and rainfall-induced landslides. J. Hydrol. 2016, 541, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaard, T.A.; Greco, R. Hydrological perspectives on precipitation intensity-duration thresholds for a landslide initiation: Proposing hydro-meteorological thresholds. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 18, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, S.; Di Perna, A.; Martinelli, M. Modelling the spatio-temporal evolution of a rainfall-induced retrogressive landslide in an unsaturated slope. Eng. Geol. 2021, 294, 106371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantar, B.; Ueda, N.; Saeidi, V.; Ahmadi, K.; Halin, A.A.; Shabani, F. Landslide susceptibility mapping: Machine and ensemble learning based on remote sensing big data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.J.; Ma, Z.G.; Li, Y.J.; Hu, K.H.; Zhang, Q.; Li, L. A grid-based physical model to analyze the stability of slope unit. Geomorphology 2021, 391, 107887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, T.M.; Augusto Filho, O. Landslide susceptibility mapping using the infinite slope, SHALSTAB, SINMAP, and TRIGRS models in Serra do Mar, Brazil. J. Mt. Sci. 2022, 19, 1018–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Ding, M. Spatiotemporal changes of landslide susceptibility in response to rainfall and its future prediction—A case study of Sichuan Province, China. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 84, 102862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Ding, M.; Cai, J.; He, Y.; Ming, Y.; Ren, H.; Li, F. Spatiotemporal landslide susceptibility assessment integrating typhoon tracks: A case study of typhoon Lekima. J. Mt. Sci. 2025, 22, 3017–3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Teng, H.; Wang, M.; Deng, Y.; Liu, F.; Mu, H. Hazard Assessment of Shallow Loess Landslides Under Different Rainfall Intensities Based on the SINMAP Model: A Case Study of Yuzhong County. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, R.L.; Savage, W.Z.; Godt, J.W. TRIGRS—A Fortran Program for Transient Rainfall Infiltration and Grid-Based Regional Slope-stability Analysis; Version 2.0; Open-File Report No. 2008-1159; US Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2008; p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, R.L.; Savage, W.Z.; Godt, J.W. Trigrs: A Fortran Program for Transient Rainfall Infiltration and Grid-Based Regional Slope-Stability Analysis; Open-File Report 2002-424; US Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Montrasio, L.; Valentino, R. A model for triggering mechanisms of shallow landslides. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2008, 8, 1149–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G.; Catani, F.; Leoni, L.; Segoni, S.; Tofani, V. HIRESSS: A physically based slope stability simulator for HPC applications. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 13, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrasio, L.; Valentino, R. Modelling rainfall-induced shallow landslides at different scales using SLIP-Part II. Procedia Eng. 2016, 158, 482–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aristizábal, E.; Vélez, J.I.; Martínez, H.E.; Jaboyedoff, M. SHIA_Landslide: A distributed conceptual and physically based model to forecast the temporal and spatial occurrence of shallow landslides triggered by rainfall in tropical and mountainous basins. Landslides 2016, 13, 497–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, V.; Hürlimann, M.; Guo, Z.; Lloret, A.; Vaunat, J. Fast physically-based model for rainfall-induced landslide susceptibility assessment at regional scale. Catena 2021, 201, 105213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnone, E.; Francipane, A.; Dialynas, Y.G.; Noto, L.V.; Bras, R.L. Implications of terrain resolution on modeling rainfall-triggered landslides using a TIN-based model. Environ. Model. Softw. 2021, 141, 105067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Uchida, T. Performance and topographic preferences of dynamic and steady models for shallow landslide prediction in a small catchment. Landslides 2022, 19, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Ji, J.; Hürlimann, M.; Medina, V. Probabilistic and physically-based modelling of rainfall-induced landslide susceptibility using integrated GIS-FORM algorithm. Landslides 2024, 21, 1461–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, S.; DelgadoTéllez, R.; Wei, F. A new slope unit extraction method for regional landslide analysis based on morphological image analysis. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2019, 78, 4139–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufano, R.; Formetta, G.; Calcaterra, D.; De Vita, P. Hydrological control of soil thickness spatial variability on the initiation of rainfall-induced shallow landslides using a three-dimensional model. Landslides 2021, 18, 3367–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, L.; Delgado-Tellez, R.; Bao, H. A physics-based probabilistic forecasting model for rainfall-induced shallow landslides at regional scale. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 18, 969–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, R.J.; Velásquez, M.F.; Sánchez, O. Applicability and performance of deterministic and probabilistic physically based landslide modeling in a data-scarce environment of the Colombian Andes. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 2021, 108, 103175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Lee, J.H.; Woo, I. Assessment of rainfall-induced shallow landslide susceptibility using a GIS-based probabilistic approach. Eng. Geol. 2013, 161, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Park, H.J. Assessment of shallow landslide susceptibility using the transient infiltration flow model and GIS-based probabilistic approach. Landslides 2016, 13, 885–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, R.J.; Mattos, A.J. Physically-based landslide susceptibility analysis using Monte Carlo simulation in a tropical mountain basin. Georisk 2020, 14, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajith, A.; Pillai, R.J. TRIGRS-FOSM: Probabilistic slope stability tool for rainfall-induced landslide susceptibility assessment. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 3401–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, T.; Guo, Z.; Wang, L.; Xu, C.; Wu, F.; Jin, B.; Peduto, D. Hazard prediction modeling for typhoon-triggered shallow landslides by integrating physically-based model and extreme rainfall analysis. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2025, 84, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, S.J.; Xie, W.L.; Guan, H. Prediction of the instability probability for rainfall induced landslides: The effect of morphological differences in geomorphology within mapping units. J. Mt. Sci. 2023, 20, 1249–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisina, C.; Scarabelli, S. A comparative analysis of terrain stability models for predicting shallow landslides in colluvial soils. Geomorphology 2007, 87, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terhorst, B.; Kreja, R. Slope stability modelling with SINMAP in a settlement area of the Swabian Alb. Landslides 2009, 6, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, I.; Keskin, I. GIS based statistical and physical approaches to landslide susceptibility mapping (Sebinkarahisar, Turkey). Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2009, 68, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.; Turek, G.; Clark, M.P.; Uddstrom, M.; Dymond, J.R. Probabilistic forecasting of shallow, rainfall-triggered landslides using real-time numerical weather predictions. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2008, 8, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Wu, B.; Wang, W.; Peng, Z. Quantifying Root Cohesion Spatial Heterogeneity Using Remote Sensing for Improved Landslide Susceptibility Modeling: A Case Study of Caijiachuan Landslides. Sensors 2025, 25, 4221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raia, S.; Alvioli, M.; Rossi, M.; Baum, R.L.; Godt, J.W.; Guzzetti, F. Improving predictive power of physically based rainfall-induced shallow landslide models: A probabilistic approach. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1305.4803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D6528-17; Standard Test Method for Consolidated Undrained Direct Simple Shear Testing of Fine Grain Soils. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- Ghorbani, A.; Babaeian, E.; Sadeghi, M.; Durner, W.; Jones, S.B.; van Genuchten, M.T. An improved van Genuchten soil water characteristic model to account for surface adsorptive forces. J. Hydrol. 2025, 661, 133692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, T. An introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2006, 27, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lithology | Dolomite | Limestone | Mudstone | Sandstone | Shale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (km2) | 254.80 | 2704.82 | 247.50 | 755.23 | 124.65 |

| Number of sampling points | 28 | 192 | 14 | 54 | 8 |

| Lithology | Sample Point ID | Plastic Limit | Liquid Limit | Lithology | Sample Point ID | Plastic Limit | Liquid Limit | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c (kPa) | φ (°) | c (kPa) | φ (°) | c (kPa) | φ (°) | c (kPa) | φ (°) | ||||

| Dolomite | 1–32 | 13.4 | 17.0 | 7.1 | 9.5 | Mudstone | 2–50 | 24.7 | 30.3 | 7.9 | 12.3 |

| 1–52 | 20.2 | 25.2 | 15.5 | 13.7 | 2–93 | 20.8 | 17.5 | 3.2 | 12.1 | ||

| 2–17 | 28.9 | 16.0 | 1.0 | 7.9 | 2–137 | 12.3 | 36.3 | 1.0 | 31.2 | ||

| 2–18 | 48.5 | 18.6 | 4.9 | 9.1 | 2–110 | 18.9 | 19.3 | 5.1 | 4.8 | ||

| 1–44 | 59.5 | 15.4 | 2.9 | 3.5 | 2–113 | 26.8 | 10.8 | 4.2 | 6.6 | ||

| 1–114 | 29.4 | 23.1 | 18.8 | 5.0 | 2–99 | 16.8 | 29.9 | 10.5 | 20.0 | ||

| 1–96 | 9.5 | 16.4 | 3.0 | 5.5 | Sandstone | 2–84 | 5.5 | 18.9 | 3.3 | 8.1 | |

| 1–46 | 37.9 | 30.5 | 0.7 | 5.7 | 2–92 | 18.3 | 13.4 | 1.9 | 6.1 | ||

| Limestone | 2–70 | 12.7 | 28.7 | 8.6 | 7.0 | 2–96 | 8.1 | 12.6 | 3.8 | 5.9 | |

| 2–78 | 38.7 | 19.8 | 5.9 | 3.7 | 2–130 | 14.1 | 8.1 | 1.1 | 10.0 | ||

| 2–108 | 11.0 | 29.6 | 1.0 | 18.8 | 2–41 | 18.8 | 30.2 | 2.7 | 15.6 | ||

| 2–109 | 17.3 | 12.6 | 3.4 | 7.0 | 2–135 | 14.2 | 8.7 | 3.3 | 7.8 | ||

| FJ015 | 50.4 | 25.8 | 0.4 | 8.6 | Shale | 2–73 | 12.2 | 14.1 | 3.1 | 6.4 | |

| FJ030 | 15.9 | 12.8 | 2.0 | 5.7 | 2–34 | 20.9 | 29.9 | 1.6 | 9.3 | ||

| 1–95 | 26.5 | 21.8 | 2.6 | 3.4 | 2–53 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 4.6 | 7.3 | ||

| 1–55 | 26.7 | 28.9 | 0.9 | 7.5 | 2–80 | 7.8 | 7.0 | 1.8 | 6.6 | ||

| 1–56 | 22.2 | 14.8 | 5.4 | 3.6 | 2–107 | 17.2 | 24.8 | 1.4 | 9.3 | ||

| Mechanical Parameter | / | Dolomite | Limestone | Mudstone | Sandstone | Shale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c (kPa) | Mean value | 30.1 | 23.14 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 12.8 |

| Standard error | 12.0 | 9.26 | 9.2 | 9.8 | 7.5 | |

| Test method | S-W test | K-S test | S-W test | K-S test | S-W test | |

| Significance p-value | 0.363 | 0.123 | 0.877 | 0.144 | 0.577 | |

| φ (°) | Mean value | 19.6 | 13.89 | 20.1 | 16.7 | 16.3 |

| Standard error | 5.4 | 5.23 | 10.2 | 7.8 | 9.0 | |

| Test method | S-W test | K-S test | S-W test | K-S test | S-W test | |

| Significance p-value | 0.57 | 0.055 | 0.605 | 0.057 | 0.581 |

| Mechanical Parameter | / | Dolomite | Limestone | Mudstone | Sandstone | Shale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c (kPa) | Mean value | 4.33 | 3.99 | 6.0 | 5.1 | 2.5 |

| Standard error | 2.46 | 1.55 | 3.7 | 6.7 | 1.5 | |

| Test method | S-W test | K-S test | S-W test | K-S test | S-W test | |

| Significance p-value | 0.560 | 0.126 | 0.799 | 0.14 | 0.529 | |

| φ (°) | Mean value | 9.3 | 5.72 | 5.15 | 6.06 | 9.0 |

| Standard error | 2.7 | 1.53 | 1.28 | 1.79 | 2.5 | |

| Test method | S-W test | K-S test | S-W test | K-S test | S-W test | |

| Significance p-value | 0.413 | 0.114 | 0.822 | 0.52 | 0.466 |

| Mechanical Parameter | Disturbance Factor | Dolomite | Limestone | Mudstone | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Value (kPa) | Standard Error | Significance p-Value | Mean Value (kPa) | Standard Error | Significance p-Value | Mean Value (kPa) | Standard Error | Significance p-Value | ||

| c (kPa) | 0.1 | 6.84 | 1.62 | 0.702 | 5.76 | 1.64 | 0.129 | 7.20 | 3.30 | 0.759 |

| 0.2 | 9.65 | 2.08 | 0.080 | 7.65 | 2.14 | 0.231 | 8.63 | 3.28 | 0.388 | |

| 0.3 | 12.90 | 5.00 | 0.075 | 9.55 | 2.79 | 0.300 | 10.00 | 3.50 | 0.746 | |

| 0.4 | 15.39 | 5.66 | 0.454 | 11.44 | 3.51 | 0.102 | 11.44 | 4.05 | 0.903 | |

| 0.5 | 17.90 | 6.50 | 0.762 | 13.33 | 4.26 | 0.492 | 12.80 | 4.70 | 0.752 | |

| 0.6 | 20.37 | 7.52 | 0.650 | 15.22 | 5.04 | 0.274 | 14.25 | 5.54 | 0.776 | |

| 0.7 | 22.90 | 8.60 | 0.795 | 17.12 | 5.83 | 0.337 | 9.70 | 5.00 | 0.846 | |

| 0.8 | 25.35 | 9.78 | 0.959 | 19.01 | 6.62 | 0.397 | 17.06 | 7.32 | 0.965 | |

| 0.9 | 27.80 | 11.00 | 0.660 | 20.90 | 7.43 | 0.307 | 18.50 | 8.30 | 0.974 | |

| φ (°) | 0.1 | 8.00 | 2.70 | 0.802 | 6.44 | 1.54 | 0.318 | 11.00 | 8.00 | 0.056 |

| 0.2 | 9.28 | 2.70 | 0.479 | 7.22 | 1.73 | 0.232 | 12.04 | 8.09 | 0.057 | |

| 0.3 | 10.60 | 2.80 | 0.075 | 8.00 | 2.05 | 0.060 | 13.00 | 8.20 | 0.096 | |

| 0.4 | 11.92 | 2.97 | 0.213 | 8.65 | 1.85 | 0.155 | 14.05 | 8.36 | 0.168 | |

| 0.5 | 13.20 | 3.20 | 0.345 | 9.40 | 2.24 | 0.096 | 15.10 | 8.60 | 0.325 | |

| 0.6 | 14.57 | 3.59 | 0.697 | 10.34 | 3.29 | 0.051 | 16.07 | 8.83 | 0.542 | |

| 0.7 | 15.90 | 4.00 | 0.444 | 11.11 | 3.76 | 0.102 | 17.10 | 9.10 | 0.388 | |

| 0.8 | 17.21 | 4.41 | 0.630 | 11.89 | 4.24 | 0.214 | 18.09 | 9.46 | 0.248 | |

| 0.9 | 18.50 | 4.90 | 0.504 | 12.67 | 4.70 | 0.154 | 19.10 | 9.80 | 0.408 | |

| Mechanical Parameter | Disturbance Factor | Sandstone | Shale | |||||||

| Mean Value (kPa) | Standard Error | Significance p-Value | Mean Value (kPa) | Standard Error | Significance p-Value | |||||

| c (kPa) | 0.1 | 5.41 | 1.66 | 0.088 | 3.60 | 1.20 | 0.487 | |||

| 0.2 | 7.46 | 3.04 | 0.092 | 4.58 | 1.43 | 0.187 | ||||

| 0.3 | 9.25 | 3.49 | 0.262 | 5.60 | 2.00 | 0.874 | ||||

| 0.4 | 11.25 | 5.63 | 0.186 | 6.64 | 2.70 | 0.443 | ||||

| 0.5 | 11.94 | 4.01 | 0.088 | 7.70 | 3.50 | 0.159 | ||||

| 0.6 | 11.79 | 2.30 | 0.075 | 8.70 | 4.24 | 0.120 | ||||

| 0.7 | 14.49 | 3.70 | 0.074 | 9.70 | 5.00 | 0.232 | ||||

| 0.8 | 17.33 | 7.97 | 0.084 | 10.75 | 5.85 | 0.365 | ||||

| 0.9 | 18.80 | 8.90 | 0.065 | 11.80 | 6.70 | 0.475 | ||||

| φ (°) | 0.1 | 7.06 | 1.73 | 0.95 | 8.20 | 2.00 | 0.255 | |||

| 0.2 | 8.05 | 1.91 | 0.542 | 9.06 | 2.53 | 0.058 | ||||

| 0.3 | 8.86 | 1.20 | 0.689 | 10.00 | 3.20 | 0.226 | ||||

| 0.4 | 10.05 | 2.78 | 0.143 | 10.88 | 3.94 | 0.826 | ||||

| 0.5 | 11.04 | 3.32 | 0.16 | 11.80 | 4.70 | 0.860 | ||||

| 0.6 | 12.04 | 3.90 | 0.135 | 12.70 | 5.56 | 0.776 | ||||

| 0.7 | 13.04 | 4.50 | 0.079 | 13.60 | 6.40 | 0.710 | ||||

| 0.8 | 14.03 | 5.10 | 0.084 | 14.52 | 7.24 | 0.660 | ||||

| 0.9 | 15.03 | 5.70 | 0.065 | 15.40 | 8.10 | 0.617 | ||||

| Lithology | Dolomite | Limestone | Mudstone | Sandstone | Shale | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (km2) | 254.80 | 2704.82 | 247.50 | 755.23 | 124.65 | 4087.00 |

| Number of slope unit | 1154 | 11,661 | 1159 | 3063 | 510 | 17,547 |

| Ratio Interval/% | 0 ≤ HSUprob < 20 | 20 ≤ HSUprob < 50 | 50 ≤ HSUprob < 60 | 60 ≤ HSUprob < 80 | 80 ≤ HSUprob ≤ 100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warning degree | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Warning color | No color | Blue | Yellow | Orange | Red |

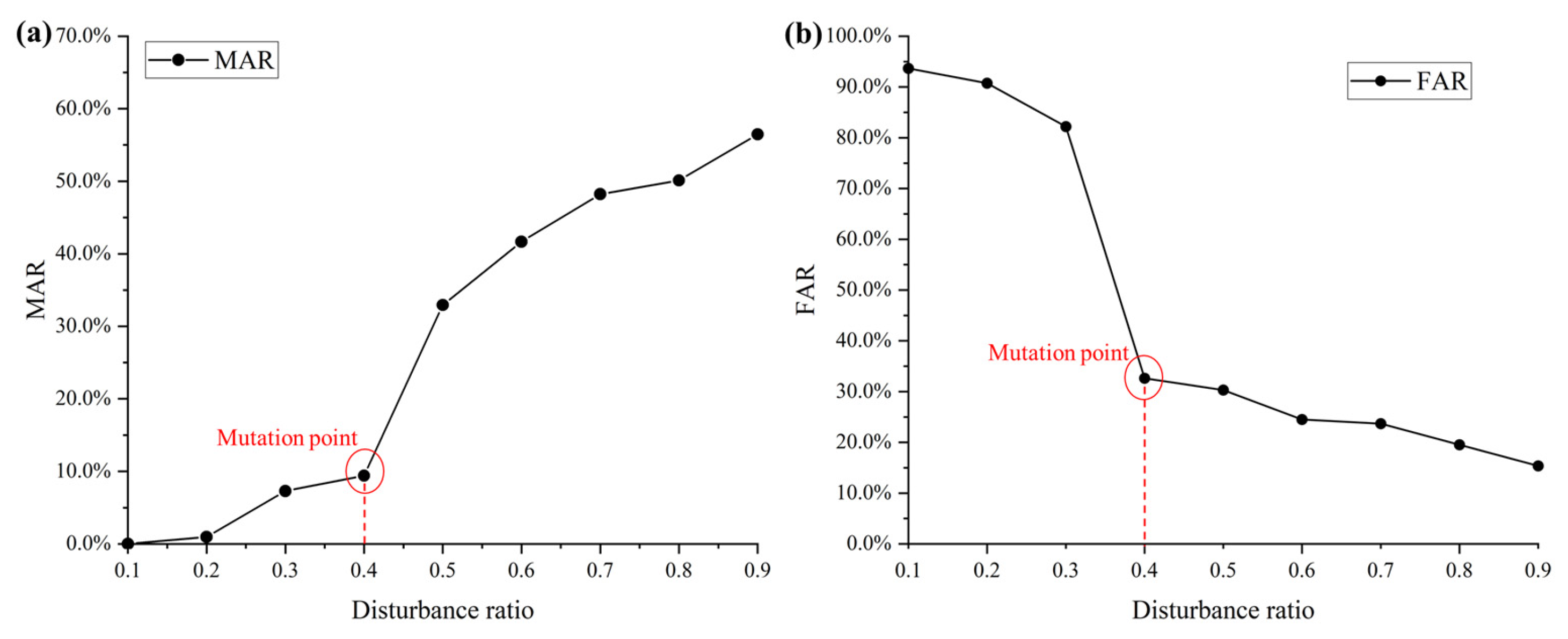

| Ratio αi | Unstable HSUs | TP | TN | FP | FN | MAR | FAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 16,461 | 425 | 1086 | 16,036 | 0 | 0.00% | 93.66% |

| 0.2 | 15,960 | 421 | 1583 | 15,539 | 4 | 0.94% | 90.75% |

| 0.3 | 14,470 | 394 | 3046 | 14,076 | 31 | 7.29% | 82.21% |

| 0.4 | 6972 | 385 | 10,535 | 6587 | 40 | 9.41% | 32.63% |

| 0.5 | 5473 | 285 | 11,934 | 5188 | 140 | 32.94% | 30.30% |

| 0.6 | 4445 | 248 | 12,925 | 4197 | 177 | 41.65% | 24.51% |

| 0.7 | 4273 | 220 | 13,069 | 4053 | 205 | 48.24% | 23.67% |

| 0.8 | 3554 | 212 | 13,780 | 3342 | 213 | 50.12% | 19.52% |

| 0.9 | 2816 | 185 | 14,491 | 2631 | 240 | 56.47% | 15.37% |

| Time (h) | Unstable HSUs | MAR | FAR | Accuracy | Precision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | 5171 | 30.59% | 28.48% | 71.47% | 70.91% |

| 20 | 5460 | 22.82% | 29.97% | 70.20% | 72.03% |

| 22 | 5707 | 13.41% | 31.18% | 69.25% | 73.52% |

| 24 | 5972 | 9.41% | 32.63% | 67.93% | 73.52% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, K.; Xie, S.; Xie, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, L.; Qi, F.; Luo, H.; Zhao, X. Research on the Impact of Regional-Scale Soil Mechanics Parameter Disturbances on Rainfall Landslides Warning. Geosciences 2025, 15, 449. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120449

Wang K, Xie S, Xie L, Zhang S, Zhu L, Qi F, Luo H, Zhao X. Research on the Impact of Regional-Scale Soil Mechanics Parameter Disturbances on Rainfall Landslides Warning. Geosciences. 2025; 15(12):449. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120449

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Kai, Shuailong Xie, Linmao Xie, Shaojie Zhang, Lin Zhu, Fuzhou Qi, Haohao Luo, and Xiangyang Zhao. 2025. "Research on the Impact of Regional-Scale Soil Mechanics Parameter Disturbances on Rainfall Landslides Warning" Geosciences 15, no. 12: 449. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120449

APA StyleWang, K., Xie, S., Xie, L., Zhang, S., Zhu, L., Qi, F., Luo, H., & Zhao, X. (2025). Research on the Impact of Regional-Scale Soil Mechanics Parameter Disturbances on Rainfall Landslides Warning. Geosciences, 15(12), 449. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120449