A Web-GIS Platform for Real-Time Scenario-Based Seismic Risk Assessment at National Level

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Concept, Innovation, and Features of the SEIS-MEC Simulator

- National-Scale Applicability: SEIS-MEC is designed to perform comprehensive impact evaluations across entire countries, supporting strategic planning and rapid response.

- Multi-Sector Synthesis: The tool consolidates seismic effects on buildings, infrastructure, population, and other critical sectors, delivering a consolidated impact overview.

- Web-Based Service: As an online platform, SEIS-MEC avoids the need for complex installations and software licenses, promoting accessibility and ease of use.

- Standalone Operation with GIS Capabilities: Although fully operational independently of traditional GIS desktop environments, SEIS-MEC incorporates GIS mapping functionalities for spatial visualization and analysis.

- User-Friendly Interface: A graphical user interface tailored for civil protection and DRM agents enhances usability, empowering non-expert users to operate the simulator efficiently during emergencies or simulations.

- Immediate Operability: By leveraging freeware databases and minimizing data preparation requirements, SEIS-MEC is ready for deployment in any country without extensive setup or calibration.

- Customizable and Integrative: Users can customize scenarios and input parameters, and the platform is designed to integrate heterogeneous national data sources, ensuring adaptability to various national contexts and data availabilities.

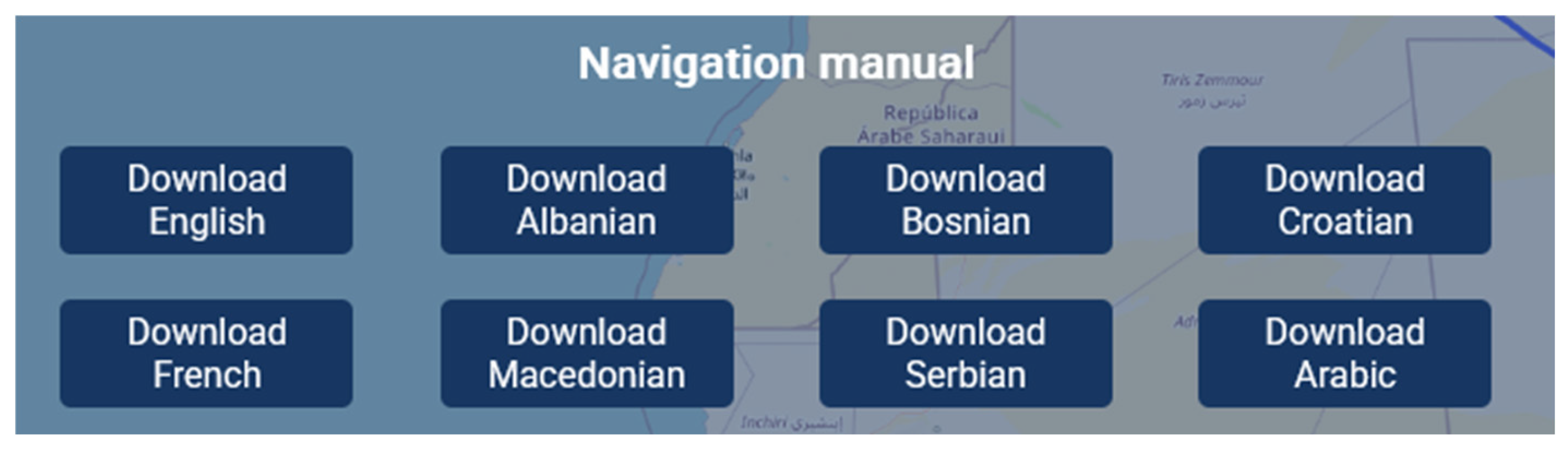

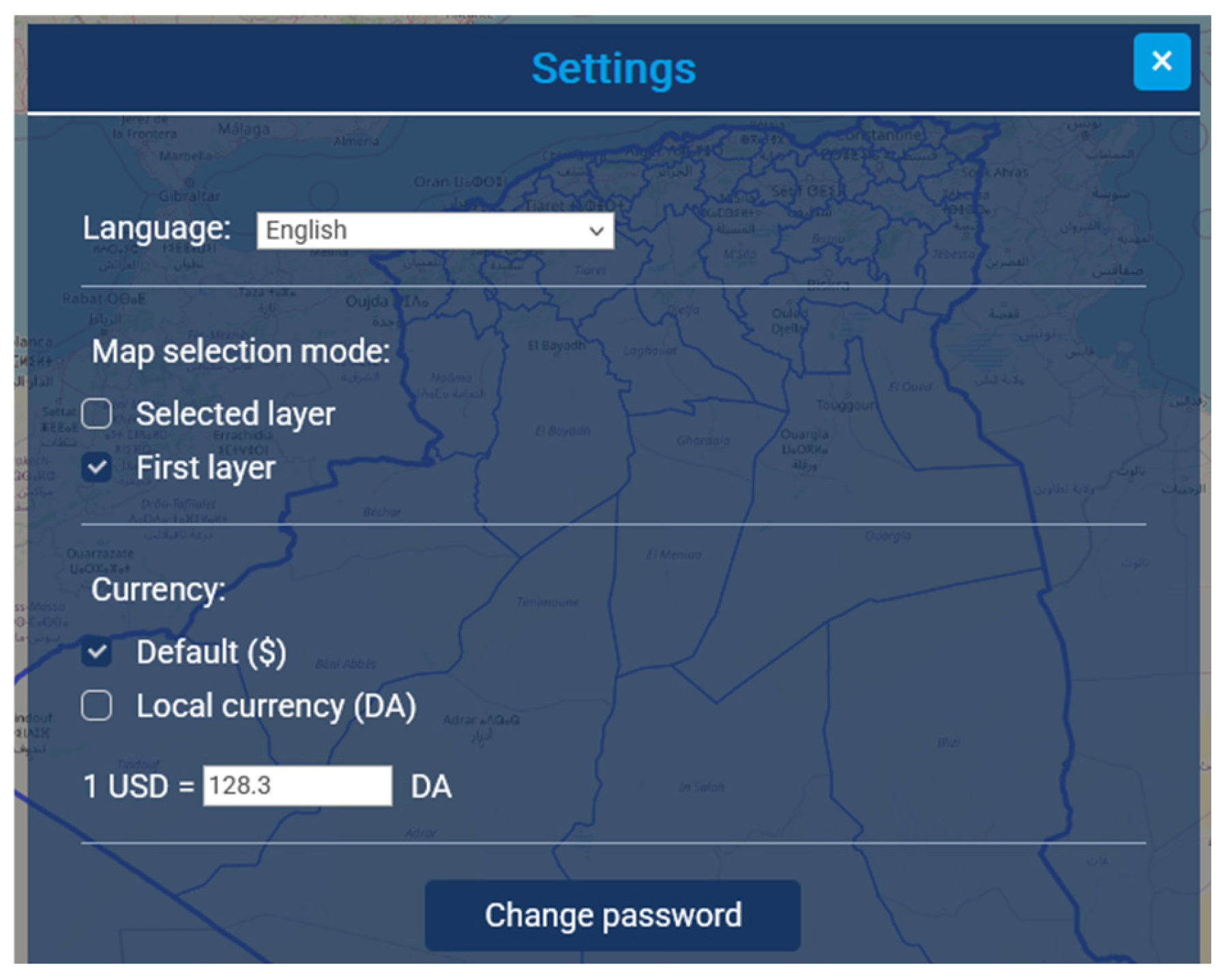

- Multilingual Accessibility: SEIS-MEC supports multiple languages for both the user interface and documentation, enhancing usability and inclusiveness for a broad range of national and international stakeholders.

3. The Platform: Data, Engine and Outputs

3.1. Freeware Data and Models Preloaded into the Platform

- Exposure database of buildings: Derived from the GEM Foundation global dataset [37,38,39,40]. It provides aggregated data on the number of residential, industrial and commercial buildings (not building by building). For each building type, it includes the number of buildings, number of occupants (residential only), repair cost, and building taxonomy. The taxonomy is expressed in terms of material, Lateral Load Resisting System, design code, number of storeys, lateral force coefficient.

- Primary and secondary roads, hospitals and schools, fire and police stations: These data are retrieved from https://mapcruzin.com (accessed on 1 January 2020 and on 1 January 2025). They can be visualized on the maps, but are not included in damage scenario calculations. A map of primary roads is reported in Figure 2 as an example.

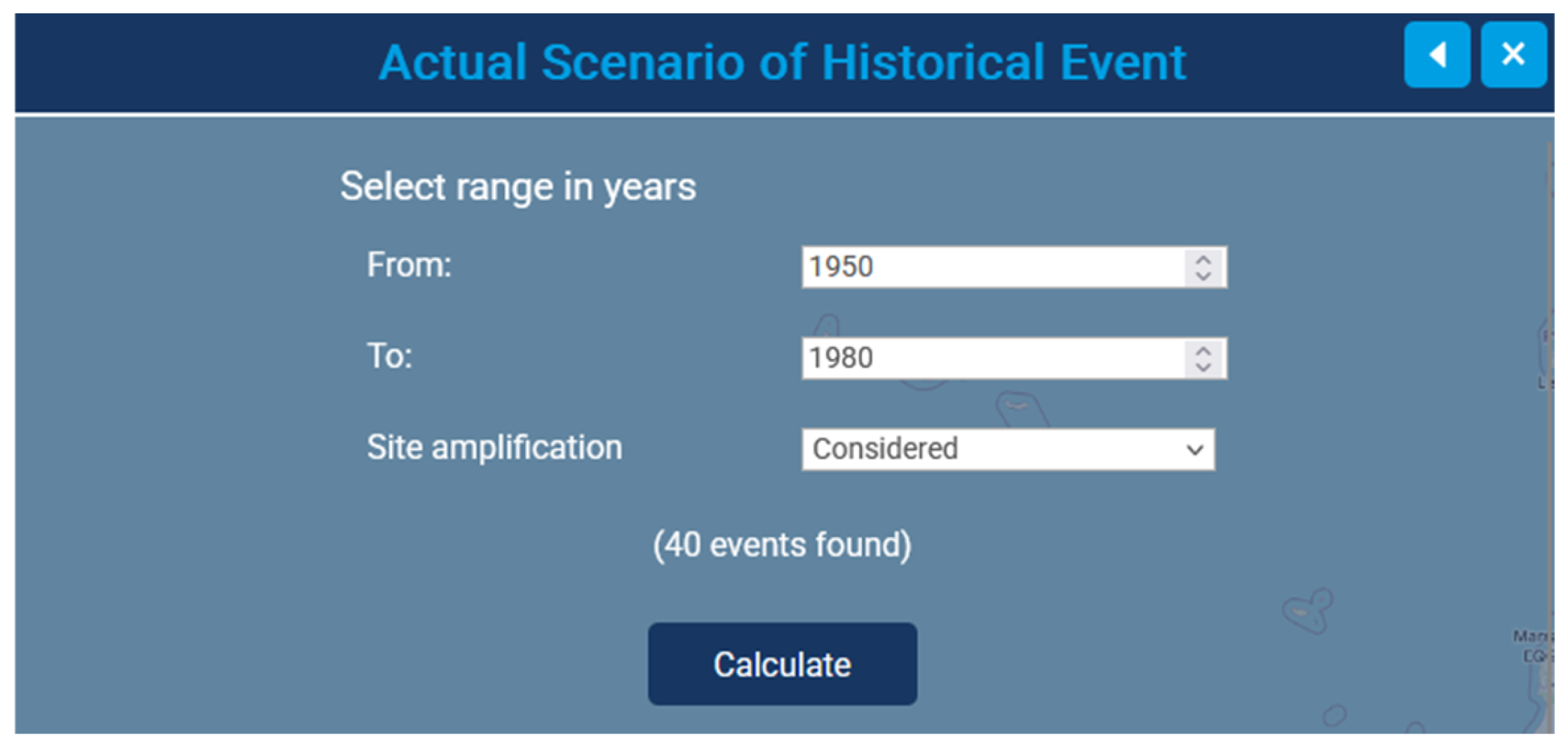

- Historical events: The catalog of relevant historical events was compiled using data from the global ISC-GEM catalog (http://www.isc.ac.uk/iscgem/, accessed on 1 January 2020 and on 1 January 2025). Includes events within national borders and outside that could significantly affect the country. Each event contains date, magnitude, depth, longitude, and latitude, and is both viewable and searchable on the map (Figure 4). These events are used to calculate “actual scenarios” for historical earthquakes.

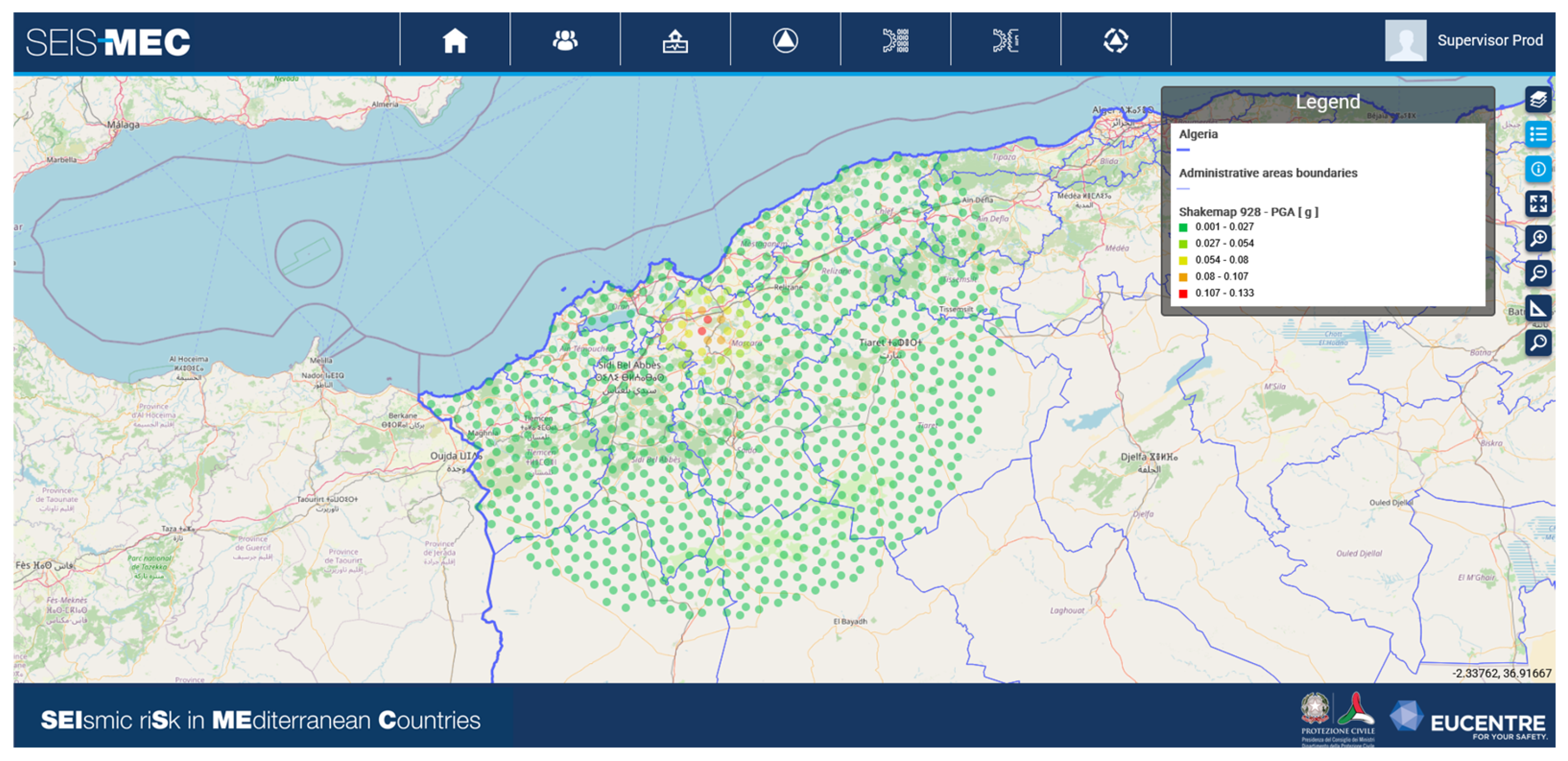

- Vs30 map: The platform integrates the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Vs30 map (average shear-wave velocity in the top 30 m), as grid of points spaced at 0.0083 degrees, freely available from [41] (Figure 5), to incorporate ground motion amplification effects. Users can generate scenarios based on rock conditions only or including soil effects.

- Fragility functions: Retrieved from the GEM Foundation database [42]. Each building taxonomy has a fragility curve, indicating the probability of reaching four damage levels: slight (D1), moderate (D2), extensive (D3), and complete (D4) for a given intensity parameter.

- Class A: Vs30 ≥ 800 m/s;

- Class B: Vs30 ≥ 360 and <800 m/s;

- Class C: Vs30 ≥ 180 and <360 m/s;

- Class D: Vs30 < 180 m/s.

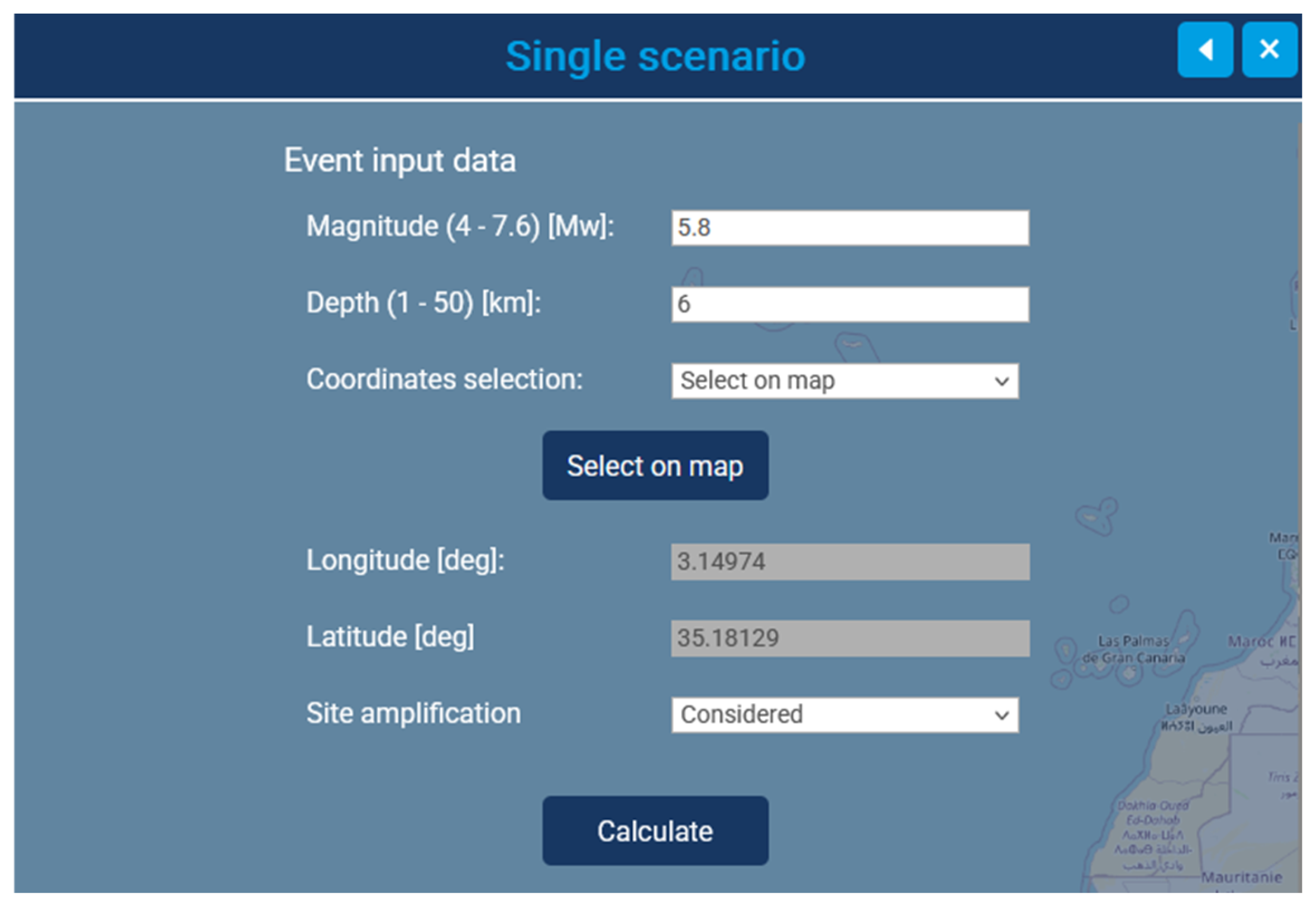

3.2. Earthquake Input Parameters Entered by the User

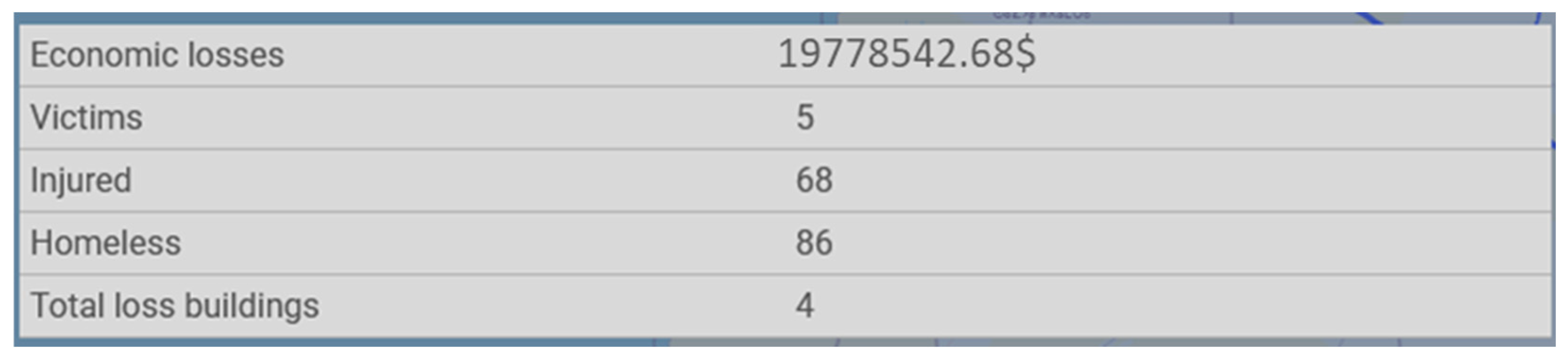

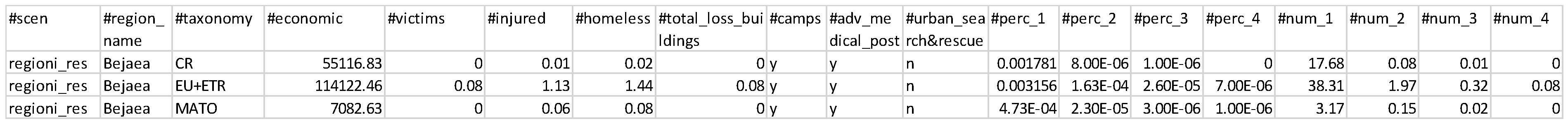

3.3. Damage Scenario Calculation and Results

- Shelters or tent camps are activated if the number of homeless reaches 20 or more.

- Advanced medical posts are activated if the number of injured is 10 or more.

- USAR teams are activated if there is 1 or more totally lost building.

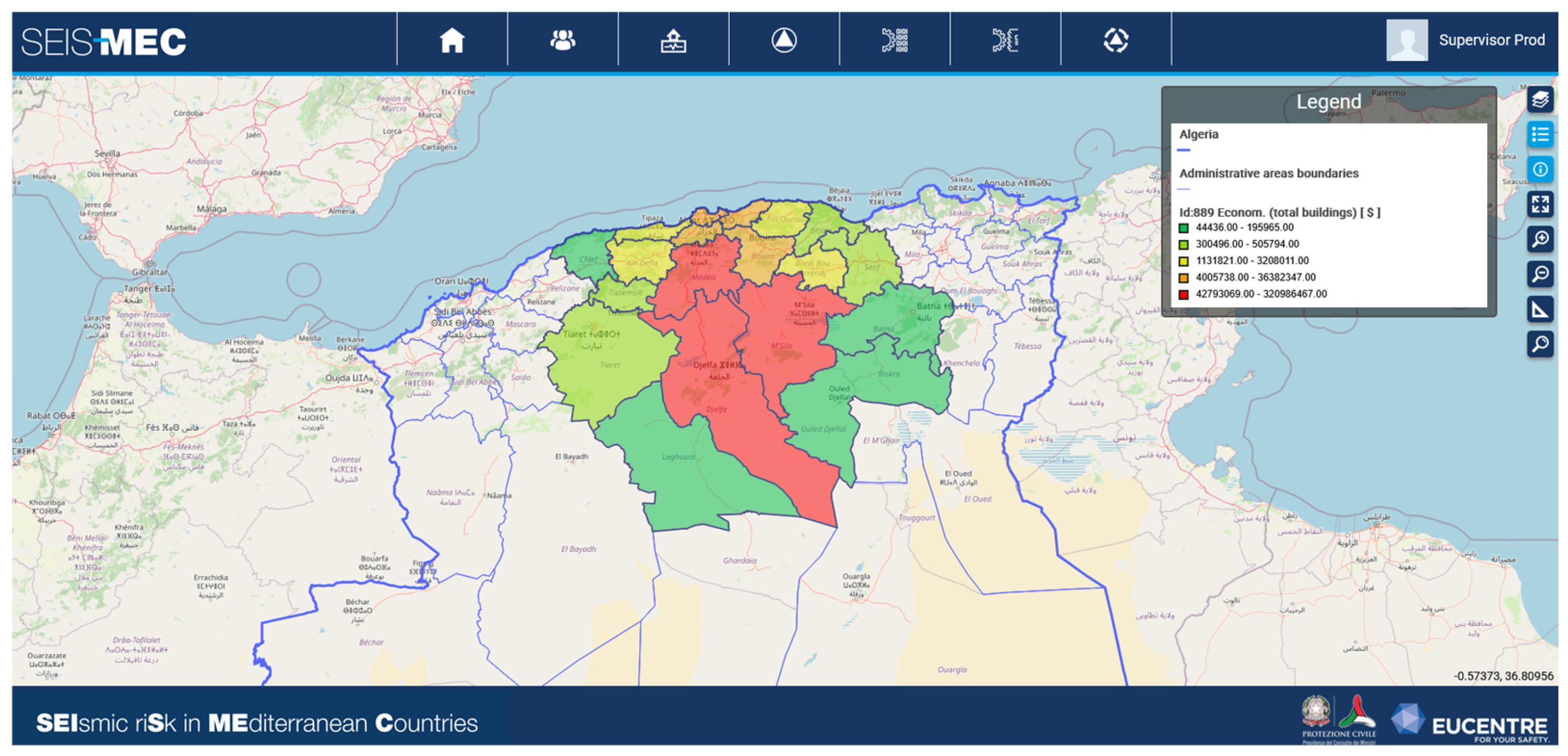

3.4. Visualization and Export Options

3.5. Reliability of the SEIS-MEC Platform

4. Application and Use Cases

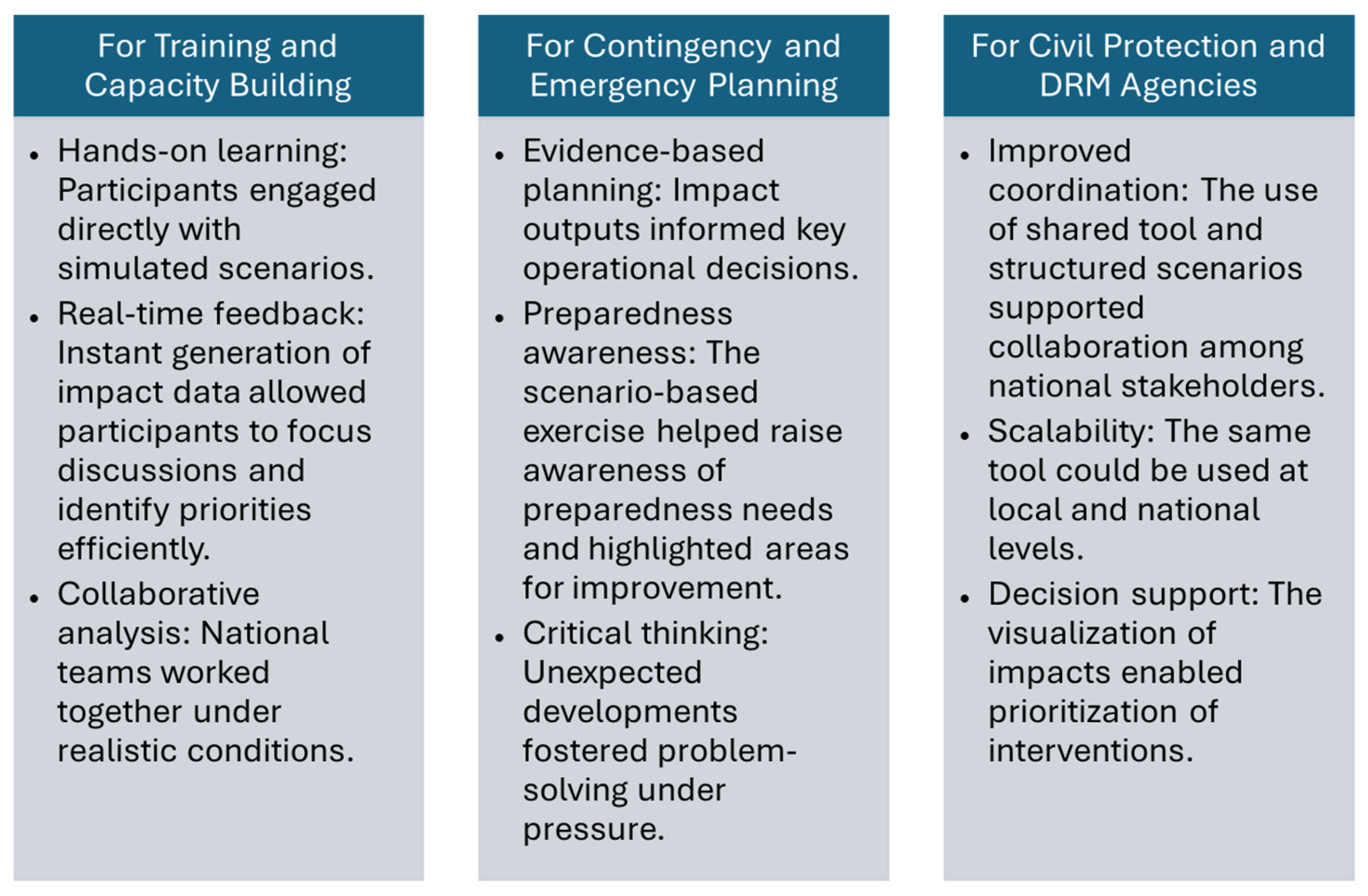

- Capacity building through simulation-based training;

- Supporting scenario-based contingency planning;

- Informing emergency response actions in real time;

- Strengthening coordination across agencies and sectors.

- Test the national teams’ ability to operate the seismic simulator;

- Build capacity in scenario-based planning;

- Reinforce linkages between simulated impacts and operational planning;

- Promote good practices in earthquake response and public communication.

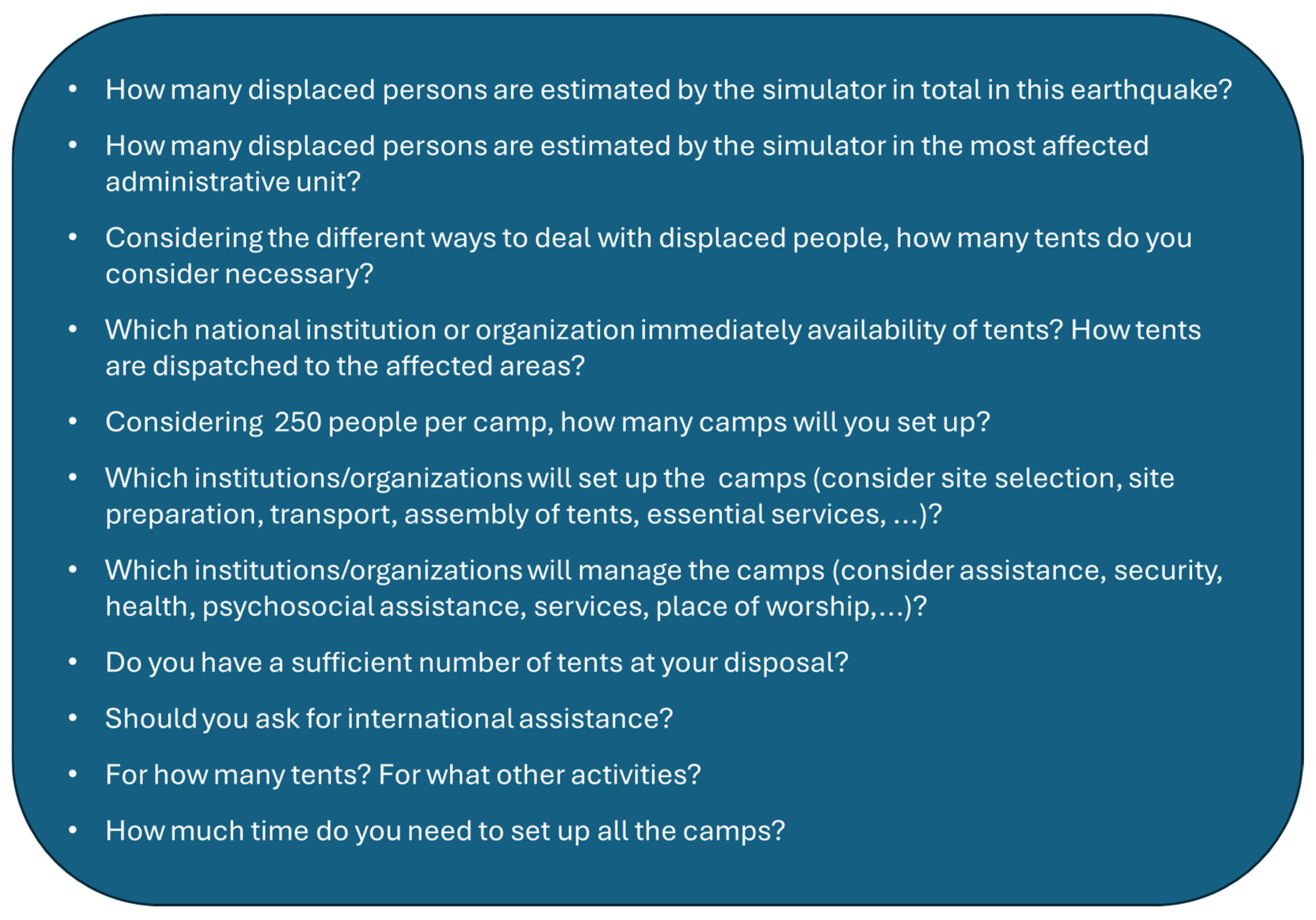

- Real-time generation of building damage and displaced population;

- Identification of priority response areas;

- Support for calculating shelter needs and logistical requirements;

- Output visualization for emergency coordination and planning.

- An Intervention Plan, focusing on the social system (e.g., displaced population, sheltering, healthcare logistics);

- A Communication Plan, addressing both affected and unaffected populations.

5. Conclusions

- National census data on residential buildings and living population;

- Information on the location of faults;

- Soil-related data directly provided by the countries;

- More detailed data on critical facilities like schools, hospitals, police stations, airports;

- Information about the type of hospitals and their bed capability;

- The possibility to upload and use existing ShakeMaps;

- The evaluation of uncertainties;

- The possibility to consult satellite cartography directly from the tool;

- Dynamic data functionalities, for sharing real-time information with other tools;

- Connection to monitoring systems installed on buildings.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAPRA | Central America Probabilistic Risk Assessment |

| D1 | Slight damage |

| D2 | Moderate damage |

| D3 | Extensive damage |

| D4 | Complete damage |

| DRM | Disaster Risk Management |

| EC8 | Eurocode 8 |

| EMT | Emergency Medical Team |

| EU | European Union |

| EUCLIDE | EUCentre for Loss-Impact and Damage Evaluation |

| FEMA | Federal Emergency Management Agency |

| GEM | Global Earthquake Model |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| GMMs | Ground Motion Models |

| GMPE | Ground Motion Prediction Equation |

| GU | Geographic Unit |

| JRC | Joint Research Centre |

| PGA | Peak Ground Acceleration |

| PPRD | Prevention, Preparedness and Response to natural and man-made Disasters |

| SEIS-MEC | SEIsmic riSk in MEditerranean Countries |

| SELENA | SEismic Loss EstimatioN using a logic tree Approach |

| SIGE | Sistema Informativo Geografico per l’Emergenza |

| TTX | Tabletop Exercise |

| USAR | Urban Search and Rescue |

| USGS | United States Geological Survey |

| Vs30 | Average shear-wave velocity in the first 30 m of depth |

References

- Erdik, M.; Fahjan, Y. Local Earthquake Rapid Loss Assessment Systems. In Rapid Earthquake Loss Assessment After Damaging Earthquakes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- LESSLOSS. Earthquake Disaster Scenario Prediction and Loss Modelling for Urban Areas; Spence, R., Ed.; IUSS Press: Pavia, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- So, E.; Spence, R. Estimating shaking-induced casualties and building damage for global earthquake events: A proposed modelling approach. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2013, 11, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdik, M.; Şeşetyan, K.; Demircioğlu, M.B.; Zülfikar, C.; Hancılar, U.; Tüzün, C.; Harmandar, E. Rapid earthquake loss assessment after damaging earthquakes. In Perspectives on European Earthquake Engineering and Seismology. Geotechnical, Geological and Earthquake Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faravelli, M.; Di Meo, A.; Borzi, B.; Cantoni, A.; Salvadori, L.; Speranza, E.; Dolce, M. SICURO+: A web platform to raise awareness on seismic risk in Italy. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 103, 104345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazantzidou-Firtinidou, D.; Gountromichou, C.; Kyriakides, N.C.; Liassides, P.; Hadjigeorgiou, K. Seismic Risk Assessment as a Basic Tool for Emergency Planning: “PACES” EU Project. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2017, 173, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, H.; Chen, L. The application of seismic risk-benefit analysis to land use planning in Taipei City. Disasters 2007, 31, 256–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roohi, M.; Ghasemi, S.; Sediek, O.; Jeond, H.; Van de Lindt, J.H.; Shields, M.; Hamideh, S.; Cutler, H. Multi-disciplinary seismic resilience modeling for developing mitigation policies and recovery planning. Resilient Cities Struct. 2024, 3, 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, A.; Samela, C.; Santarsiero, G.; Vona, M. Scenari di danno sismico per l’esercitazione nazionale di Protezione civile “Terremoto Val d’Agri 2006”. In Proceedings of the XII Convegno ANIDIS L’Ingegneria Sismica in Italia, Pisa, Italy, 10–14 June 2007. [Google Scholar]

- UNDRR. Design and Conduct Simulation Exercises—SIMEX. Words into Action Guideline Series. 2012. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/publication/words-action-guidelines-design-and-conduct-simulation-exercises-simex (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Silva, V.; Crowley, H.; Bazzurro, P. Exploring risk-targeted hazard maps for Europe. Earthq. Spectra 2016, 32, 1165–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, I.E.; Bommer, J.J.; Stafford, P.J.; Crowley, H.; Pinho, R. The Influence of Geographical Resolution of Urban Exposure Data in an Earthquake Loss Model for Istanbul. Earthq. Spectra 2010, 26, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuccolo, E.; Bolzon, G.; Pitari, F.; Rodríguez Muñoz, L.; Monsalvo Franco, I.E.; Scaini, C.; Poggi, V.; Smerzini, C.; Salon, S. UrgentShake: An HPC System for Near Real-Time Physics-Based Ground Shaking Simulations to Support Emergency Response Efforts; EGU25-9353; EGU General Assembly: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, A.; Falcone, S.; D’Alessandro, A.; Vitale, G.; Giovinazzi, G.; Morici, M.; Dall’Asta, A.; Buongiorno, M.F. A Technological System for Post-Earthquake Damage Scenarios Based on the Monitoring by Means of an Urban Seismic Network. Sensors 2021, 21, 7887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.; Horspool, N. Combining USGS ShakeMaps and the OpenQuake-engine for damage and loss assessment. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2019, 48, 634–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zeng, X.; Xu, Z.; Guan, H. Improving the Accuracy of near Real-Time Seismic Loss Estimation using Post-Earthquake Remote Sensing Images. Earthq. Spectra 2018, 34, 1219–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubaldi, E.; Özer, E.; Douglas, J.; Gehl, P. Examining the contribution of near real-time data for rapid seismic loss assessment of structures. Struct. Health Monit. 2022, 21, 118–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.; Crowley, H.; Pagani, M.; Monelli, D.; Pinho, R. Development of the OpenQuake engine, the Global Earthquake Model’s open-source software for seismic risk assessment. Nat. Hazards 2014, 72, 1409–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Saiz, J.; González-Rodrigo, B.; Rejas-Ayuga, J.G.; Hidalgo-Leiva, D.A.; Marchamalo-Sacristán, M. Assessing Building Seismic Exposure Using Geospatial Technologies in Data-Scarce Environments: Case Study of San José, Costa Rica. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, F.O.; Stafford, P.J.; Bommer, J.J.; Erdik, M. State of the Art of European Earthquake Loss Estimation Software. In Proceedings of the 14th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Beijing, China, 12–17 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Makhoul, N.; Argyroudis, S. Loss estimation software: Developments, limitations and future needs. In Proceedings of the 16th European Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Thessaloniki, Greece, 18–21 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Guérin-Marthe, S.; Gehl, P.; Negulescu, C.; Auclair, S.; Fayjaloun, R. Rapid earthquake response: The state-of-the art and recommendations with a focus on European systems. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 52, 101958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.L.; Tsionis, G. National seismic risk assessment: An overview and practical guide. Nat. Hazards 2025, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JRC. Seismic Risk Assessment Tools Workshop: Overview and Comparative Analysis; Joint Research Centre, European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). HAZUS Earthquake Model; Technical manual Hazus 6.1; Federal Emergency Management Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Cardona, O.D.; Ordaz, M.; Reinoso, E. CAPRA—Comprehensive Approach for Probabilistic Risk Assessment: International initiative for risk management effectiveness. In Proceedings of the 15th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Lisbon, Portugal, 24–28 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yalçın, D.; Fahjan, Y.; Eravcı, B.; Yanık, K. AFAD-RED Rapid Earthquake Damage and Loss Estimation Software: Example of Adıyaman Samsat Earthquake. In Proceedings of the 9th Congress of the Balkan Geophysical Society, European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers (EAGE), Antalya, Turkey, 5–9 November 2017; ISBN 9781510857162. [Google Scholar]

- Nievas, C.I.; Crowley, H.; Weatherill, G.; Cotton, F. Real-Time Loss Tools: Open-Source Software for Time- and State-Dependent Seismic Damage and Loss Calculations. Features and Application to the 2023 Türkiye-Syria Sequence. Seismica 2025, 4, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, A.; Pitilakis, K.; Silva, V.; Rao, A. Infrastructure seismic risk assessment: An overview and integration to contemporary open tool towards global usage. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 21, 4237–4262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, S.; Lang, D.H.; Lindholm, C.D. SELENA: An open-source tool for seismic risk and loss assessment using a logic tree computation procedure. Comput. Geosci. 2010, 36, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momeni, P.; Goda, K.; Sirous, N.; Molnar, S. Rapid Computation of Seismic Loss Curves for Canadian Buildings Using Tail Approximation Method. Geohazard 2025, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goretti, A.; Sabetta, F. Real Time Seismic Loss Estimation in Italy; Geophysical Research Abstracts, EGU2009-544; EGU General Assembly: Vienna, Austria, 2009; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Di Pasquale, G.; Ferlito, R.; Orsini, G.; Papa, F.; Pizza, G.; Van Dyck, D. Seismic scenario tools for emergency planning and management. In Proceedings of the XXIX General Assembly of the European Seismological Commission, Potsdam, Germany, 13–17 September 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Faravelli, M.; Borzi, B.; Onida, M.; Pagano, M. Tools for seismic risk assessment on different asset types. In Proceedings of the 18th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Milan, Italy, 30 June–5 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bozzoni, F.; Borzi, B.; Faravelli, M.; Onida, M.; Pagano, M.; Quaroni, D. A webgis tool to assess the seismic risk of health facilities for emergency management in Italy. In Proceedings of the 18th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Milan, Italy, 30 June–5 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dolce, M.; Goretti, A.; Germagnoli, F.; Borzi, B.; Faravelli, M. The SeisMec WebGis Platform for Real-time Seismic Scenarios Supporting Disaster Risk Management. In Proceedings of the 5th Annual Seminar of Disaster Risk Management Center, Virtual, 17–18 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Global Earthquake Model. GEM Foundation. Available online: https://www.globalquakemodel.org/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Crowley, H.; Despotaki, V.; Rodrigues, D.; Silva, V.; Toma-Danila, D.; Riga, E.; Karatzetzou, A.; Fotopoulou, S.; Zugic, Z.; Sousa, L.; et al. Exposure model for European seismic risk assessment. Earthq. Spectra 2020, 36 (Suppl. 1), 252–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabeek, J.; Silva, V. Modeling the residential building stock in the Middle East for multi-hazard risk assessment. Nat. Hazards 2020, 100, 781–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicole, P.; Silva, V.; Amo-Oduro, D. Development of a uniform exposure model for the African continent for use in disaster risk assessment. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 71, 102823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USGS Database. Available online: https://earthquake.usgs.gov/data/vs30/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Martins, L.; Silva, V. Global Vulnerability Model of the GEM Foundation; GitHub: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://github.com/gem/global_vulnerability_model/ (accessed on 1 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Akkar, S.; Sandıkkaya, M.A.; Bommer, J.J. Empirical Ground-Motion Models for Point- and Extended-Source Crustal Earthquake Scenarios in Europe and the Middle East. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2014, 12, 359–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1998-1; Eurocode 8: Design of Structures for Earthquake Resistance—Part 1: General Rules, Seismic Actions and Rules for Buildings. The European Union Per Regulation 305/2011, Directive 98/34/EC, Directive 2004/18/EC. European Standards: Brussels, Belgium, 2004.

- Papadopoulos, G.A.; Agalos, A.; Carydis, P.; Lekkas, E.; Mavroulis, S.; Triantafyllou, I. The 26 November 2019 Mw 6.4 Albania Destructive Earthquake. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2020, 91, 3129–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duni, L.; Theodoulidis, N. Short Note on the November 26, 2019, Durrës (Albania) M 6.4 Earthquake: Strong Ground Motion with Emphasis in Durrës City. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Durrës Earthquake and Eurocodes (ISDEE-2020), Tirana, Albania, 21–22 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Albania; European Union; United Nations Agencies; World Bank. Albania Post-Disaster Needs Assessment, Volume A Report; OCHA: Tirana, Albania, 2020.

- USGS. M 6.4, 15km WSW of Mamurras, Albania, PAGER, Event ID: us70006d0m. 2020. Available online: https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us70006d0m#pager (accessed on 15 September 2025).

| Icon | Section | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Home | Provides general information, a disclaimer, and data sources. |

| Exposure layers | Allows users to add or remove layers representing elements exposed to risk, such as buildings, roads, and other assets. |

| Seismic data | Manages the visualization of seismic data layers, including hazard maps and historical seismic events. |

| Civil protection layers | Manages the visualization of the strategic buildings vital for emergency operations, like fire-fighting and police stations. |

| Single scenario | This tab is dedicated to the calculation and visualization of results for an earthquake scenario defined by the user through magnitude, epicenter, and focal depth. |

| Actual Scenario of Historical Event | Manages the selection of a set of historical seismic event from a specified time window (seismic catalog), enabling the platform to calculate and visualize the impacts associated with all the selected event. |

| Emergency management | Manage the visualization of the response needs derived from previously calculated scenarios, such as the potential need for tent camps, advanced medical posts, or Urban Search And Rescue (USAR) teams. |

| Icon | Function | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Layers panel | Used to show/hide, select or delete layers. |

| Legend panel | The legends for the visible layers are displayed. |

| Info | Toggles the info function: when activated, clicking on a feature on the map selects it and displays a pop-up info window. When deactivated, clicking on the map has no effect. |

| Zoom extent | Display the full extent. |

| Zoom in | Zooms to a closer view. |

| Zoom out | Zooms to a wider view. |

| Measurement tool | Enables the measuring tool. Clicking on the map adds measurement points, and double-clicking displays a pop-up showing the distance in km. |

| Search | Opens the search panel. Two different search options are available: By municipality or by coordinates. |

| Type of Losses | Parameters |

|---|---|

| Economic losses | 5% D1 + 30% D2 + 60% D3 + 100% D4 |

| Fatalities | 1% D3 + 10% D4 |

| Injured | 30% D3 + 85% D4 |

| Homeless | 40% D3 + 100% D4 |

| SEIS-MEC | PAGER | PDNA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatalities | 89 | 128 | 55 |

| Injured | 1020 | 913 | |

| Repair cost | 53 | 325 | 603 |

| Buildings at D1 + D2 | 8964 | 10,667 | |

| Buildings at D3 | 302 | 3163 | |

| Buildings at D4 | 223 | 1915 |

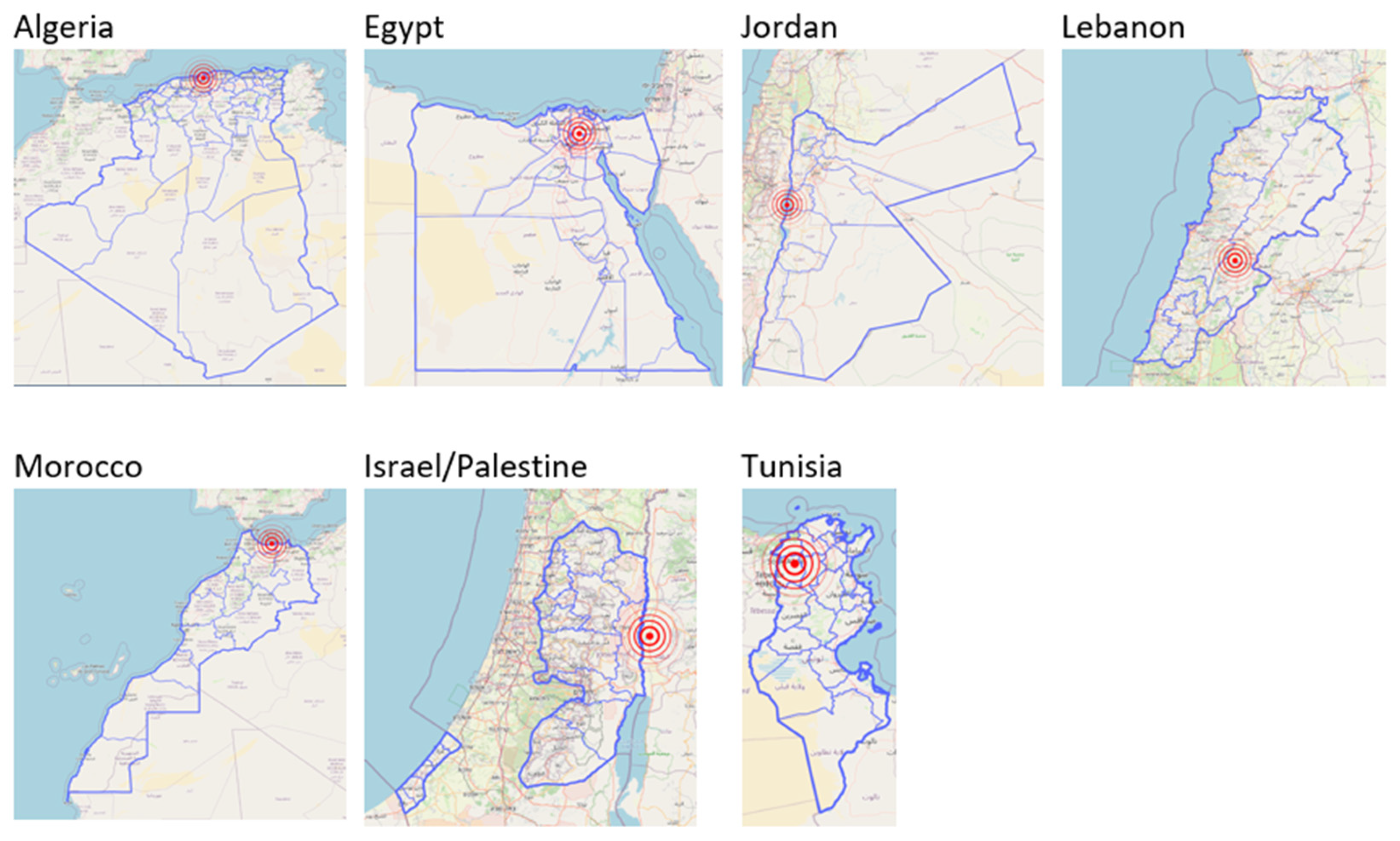

| Country | Magnitude (Mw) | Depth (km) | Longitude | Latitude | Event Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algeria | 7.08 | 10 | 1.374 | 36.199 | 10 October 1980 |

| Egypt | 5.77 | 23.3 | 31.138 | 29.746 | 12 October 1992 |

| Jordan | 5.67 | 15 | 35.487 | 31.522 | 18 December 1956 |

| Lebanon | 5.5 | 15 | 35.812 | 33.687 | 16 March 1956 |

| Morocco | 6.34 | 12.2 | −4.016 | 35.232 | 24 February 2004 |

| Israel/Palestine | 6.13 | 15 | 35.579 | 32.031 | 11 July 1927 |

| Tunisia | 5.51 | 15 | 8.836 | 36.232 | 20 February 1957 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goretti, A.; Faravelli, M.; Casarotti, C.; Borzi, B.; Quaroni, D. A Web-GIS Platform for Real-Time Scenario-Based Seismic Risk Assessment at National Level. Geosciences 2025, 15, 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15100385

Goretti A, Faravelli M, Casarotti C, Borzi B, Quaroni D. A Web-GIS Platform for Real-Time Scenario-Based Seismic Risk Assessment at National Level. Geosciences. 2025; 15(10):385. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15100385

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoretti, Agostino, Marta Faravelli, Chiara Casarotti, Barbara Borzi, and Davide Quaroni. 2025. "A Web-GIS Platform for Real-Time Scenario-Based Seismic Risk Assessment at National Level" Geosciences 15, no. 10: 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15100385

APA StyleGoretti, A., Faravelli, M., Casarotti, C., Borzi, B., & Quaroni, D. (2025). A Web-GIS Platform for Real-Time Scenario-Based Seismic Risk Assessment at National Level. Geosciences, 15(10), 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15100385