Abstract

Climate-related geohazards, such as landslides, floods, and coastal erosion due to climate change, are increasingly impacting human settlements and activities. This study, part of the European Project RESPONSe (Interreg Italy–Croatia), investigates the perception of climate change as a catalyst of future geohazards among the citizens of the Veneto region (northeastern Italy). A total of 1233 questionnaires were completed by adult citizens and analyzed by means of inferential statistics. The results highlight a widespread perception of climate change as a general threat for the environment, but not directly transposed to the frequency and intensity of future geohazards. Certainly, changes in temperatures and rainfall are widely expected and acknowledged, yet the comprehension related to the hydrogeological effects seems to vary proportionally to the physical proximity to these hazards. Such outcomes underline that there is still a common lack of understanding of the eventual local impact of the climate crisis. For these reasons, it is suggested that decision makers consider directing their efforts to enhance the citizens’ knowledge base in order to build a climate-resilient society.

1. Introduction

The Earth’s changing climate is causing alterations in a vast number of environmental conditions [1,2,3,4,5,6], that trigger, inter alia, different geological hazards such as floods, landslides and coastal erosion. Such phenomena have been largely studied from a physical point of view, using mathematical models in order to quantify the impact and predict future scenarios [2]. Moreover, because of the alarming speed of ongoing changes, research is also focusing on evaluating the vulnerability to climate change and geohazards considering cultural, social, and economic factors [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Climate change is indeed a global phenomenon, mitigation for which requires both global and local effort, while adaptation to its impact is mainly feasible by considering specific features at a local scale [21]. Although climate change has been strongly associated to an issue of global governance, even in terms of disaster risk reduction [22], the role of the specific geographical context, at different scales, has been recognized only more recently [23].

As a matter of fact, due to its geographical, physical and geomorphological setting, Italy is severely affected by climate change, even though in a nonuniform manner [24]. For example, a study carried out by Lionello et al. [25] showed that precipitation decreased more in the center and south than in the north, especially in the winter period. Moreover, the frequency and intensity of climate-related geohazards seems consistently related to ongoing local climate change [26,27,28]. For instance, studies conducted throughout Italy at the regional–local scale show that the projected changes in precipitation patterns are expected, in some cases, to increase [29,30], while, in other cases, to decrease [31,32] the probability of landslides occurrence. Particularly, the Veneto region, located in northeast Italy, is exposed to various geohazards, such as landslides in the internal mountainous areas and floods and erosion of beaches, wetlands and river mouths in the plains and coastal areas [33,34,35,36,37]. In the future, the occurrence of these events is even expected to intensify [33,34,35,36]. Moreover, Veneto is affected by the slow sinking movement that concerns the northeastern Italian coast which, together with the sea level rise, will expose the coastal areas and the flood plains to an enhanced risk of flooding [38]. It is therefore important that communities living in this area susceptible to geological hazards have a realistic perception of the risks associated with these phenomena.

Risk perception is a subjective process of collecting, selecting and interpreting signals about the impact of events directly or indirectly experienced [39,40,41,42]. The importance of risk perception is closely linked to the response of citizens to a natural event and, as such, it is increasingly recognized in the scientific literature. According to the protection motivation theory [43,44], for example, the perception of risk is the result of two elements, namely the perceived probability and the perceived severity, two elements with a very different meaning. The perceived probability refers only to the moment in which a citizen thinks that a certain event will occur, without worrying about how this happens and what consequences it may have; the perceived severity, on the other hand, consists in attributing a quantification in terms of damage deriving from a certain event. It is therefore evident that the perception of a high probability of risk translates into a weak motivation if not accompanied by the awareness of the damage that such an event will cause [43].

For these reasons, significant differences in climate change perception may arise among individual stakeholders and groups within a specific geographical and cultural context, driven by psychological and cultural factors, values, and beliefs [45,46]. Hence, a lack of self-vulnerability perception of a local community can influence the effectiveness and durability of the adaptation measures implemented by local authorities, and consequently the resilience of these individuals [47]. As a matter of fact, communication represents one of the main challenges to increase citizens’ risk perception and scientific communicators have been struggling to convey the dangers of climate change [48,49], as well as the relation with geohazards [50]. In this sense, the role of institutions is crucial in influencing the adaptive and maladaptive behaviors [51,52] of citizens. They may represent the link between citizens and the scientific community [53] and the promoters of contextual public engagement involved in discussing, learning about, prioritizing, and acting on climate change, thus shaping new aspects of local climate culture [54,55].

The perception of geohazards has been largely investigated in Italy [16,56,57,58,59,60]. For instance, a study concerning the area of Frosinone, within the Lazio region, evidenced that though confirming recurrent experiences of landslides, local respondents did not appear particularly aware of the related risk, nor that it could actually affect their daily life, although the eventual responsibility was mainly placed on local authorities and on land management plans [56]. On the contrary, research that involved the multihazard area surrounding Vesuvius in the Campania region suggested that the direct experience of landslides and floods positively influenced the perception of hazard occurrence, while for earthquakes there was no association. In addition, in that case it was also possible to evidence that though the perceived likelihood of the occurrence of floods was consistent with the projections of the local emergency plans, the perceived severity varied with actual exposure to such events [57]. The risk of tsunami was investigated in the southern regions of Calabria and Puglia, where it emerged that it was rather undervalued. Nevertheless, a rather significantly different perception appeared to be related to past events in the area, as well as the proximity to a real or supposed source of threat (such as nearby volcanoes), though further influencing factors might also be education and gender [58]. The Calabria region was involved also in specific research into the perception of geohazards, following some recently occurred events, that allowed the general high awareness of the population of the threat posed by landslides and floods for their area, and their personal exposure to such threats to be observed. In addition, the responsibility for the detrimental consequences of the geohazards were mainly attributed to human activities and in particular to the inefficacy of the actions implemented by local authorities [59]. Particularly, in a specific community of the Calabria region, the awareness of local geohazard risk was high and the predictability of the occurrence was deemed significant by locals, as a consequence of the knowledge of their surroundings and of past experiences of analogous events [60]. As a last example, a study conducted in 2014 showed that Italians are more concerned about earthquakes than about floods and landslides, and that floods and landslides are primarily caused by inappropriate land management [16]. Even if climate change is taken into consideration in many of these studies, there is still the need to deepen the understanding of the perception of climate change as a driver for geohazards.

In such a context, this study is introduced, pursuing the following objectives: (1) to analyze the climate change perception of the Veneto region’s citizens; (2) to analyze their perception of the current and future impact of geohazards; (3) to analyze the influence of geographical position in such perceptions. This research makes a unique contribution to the literature by providing some of the first empirical evidence of the perception of geological hazards in the context of climate change. This work ultimately aims at identifying the possible relations that would guide decision makers in the definition of efficient and durable management and adaptation strategies that consider the connection between climate change and geological hazards.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The research is part of the Interreg Italy–Croatia Project RESPONSe (Strategies to adapt to climate change in Adriatic regions) that aims at empowering local policy makers to enable climate-smart governance approaches and promote sustainable living in the Adriatic marine and coastal areas. The Veneto Region is one of the pilot areas involved in the RESPONSe project.

The region is made up of approximately 60% of flat land and 40% of hilly and mountainous land. From the geomorphological point of view, it can be divided into different units enclosed in two main groups: on the one hand, the forms with prevalent erosion observable in the Alpine and pre-alpine high grounds, on the other, the forms with prevalent accumulation corresponding to the foothills and the Padano-Venetian plain [61]. From the hydrological point of view, the Veneto reality is extremely complex. Here many rivers, including the Po, the most important river in Italy, have large embankments along their course and are often suspended in the final portion, resulting in the river flowing above ground level. In addition, there is an important minor hydrographic network, mainly located in the eastern portion, which flows below sea level and for which a mechanical lifting system is required for the outflow. Finally, the city of Venice, the best known in the region, is strongly affected by the periodic variations of the sea level.

The Veneto Region is the fourth most densely populated region of Italy, with 4 852 453 residents and a density of about 264 people per km2. About 41% of the population lives in coastal provinces (Metropolitan City of Venice, Rovigo and Padova), where the population density is particularly high. Here are present intensive crops, intensive farming, inhabited areas and small industries even outside the large, inhabited centers. The remaining 59% of the population lives in inner provinces, thus farther from the sea, characterized by the presence of hills and mountains, as well as plains (Verona, Treviso, Vicenza and Belluno) [62].

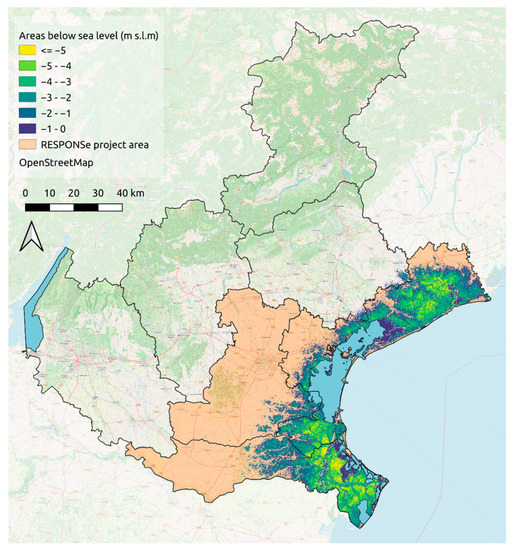

The characteristics of the Veneto Region are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The Veneto Region with provincial borders and highlighted in orange the provinces that are eligible areas of the RESPONSe project. The other colored areas identify the portions of the plain below sea level.

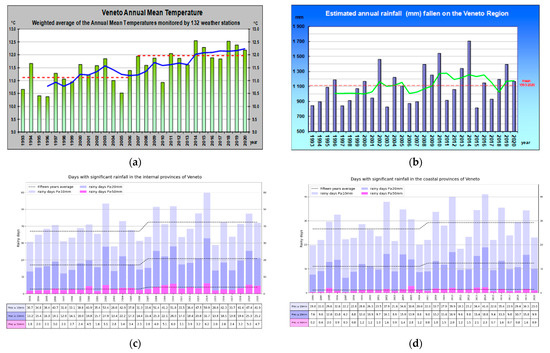

In addition to the already complex situation, the effects of the changing climate are evident in the region. During the period 1993–2019, the 132 meteorological stations of the Regional Agency for Environmental Protection and Prevention of Veneto (ARPAV) network registered an increase in the mean temperature of about 0.5 °C per decade (Figure 2a). Furthermore, during the period 1993–2020, the 160 rain gauge stations of the ARPAV network registered a considerable variability of the annual precipitation with alternation of drought situations to situations of pluviometric surplus (Figure 2b). Such anomalies are less visible in the coastal provinces (Figure 2d) than in hilly and mountainous provinces, where the number of days with intense precipitation is higher (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Trend in the last 28 years of average annual temperatures in Veneto (considering 132 meteorological stations). The red dotted lines represent the average in the first and subsequent 14 years (increase of about 0.8 °C). The blue line represents the 4-year moving average and also, in this case, the increase over time is well highlighted (a). Estimation of the annual rainfall of the period 1993–2020 that fell on the Veneto region, elaborated by spatializing the measurements carried out by 160 rain gauge stations. The red dotted line represents the 1993–2020 average. The green line represents the 4-year moving average. A tendential increase in rainfall is observed in the period 2008–2014 (b). Days with significant precipitation for the period 1993–2020 in the hilly and mountainous provinces of Veneto (c). Days with significant precipitations for the period 1993–2020 in the coastal provinces of Veneto (d).

As a consequence of such premises, the Veneto Region is particularly subject to both climate change and geological hazards. In 2007 (26 September), the coastal area, already strongly characterized by erosion phenomena, was affected by high intensity precipitation events that saw the area between Chioggia and Mestre-Marghera (Metropolitan City of Venice), crucial from an economic point of view, affected by a quantity of rainfall equal to 35–40% of the total which affects the sector on average in a year, with consequent widespread flooding.

In September of the following years of 2008, 2009 and 2010, in the coastal area, storms lasting 6–12 h of significant intensity were observed even if with lower rainfall levels (140–250 mm in 12 h). In 2010 (31 October–2 November), the region was affected by a major flood that caused numerous landslides (822), especially in the mountain sector, with river bank breaks (13 on main waterways) and with extensive flooding that affected rural areas and urban agglomerations. This event resulted in 3 deaths, 168 injuries and 3500 displaced persons, as well as significant economic damage to the agricultural and industrial sectors [63]. More recently, the Vaia storm (27–30 October 2018) produced in the initial phase multiple phenomena of hydrological instability in the mountain sector and, in the final phase of the event, major crashes of forest plants, about 12,227 hectares of forest felled in Veneto and 42,500 hectares felled overall in the Alps [64].

During this event, important high tide phenomena also occurred in Venice, which were repeated with even greater intensity in the following November, 2019. The damage of the Vaia storm in Veneto can be summarized as: 3 deaths, EUR 1 billion in damage to homes and the road network; 1.5 million m3 of sand removed from the coasts, with restoration costs estimated at EUR 20 million and 170 thousand electrical users disconnected in the hours and days following the event [65].

2.2. Analysis

2.2.1. Data Collection

To investigate the level of perception of geohazards in the context of climate change of the Veneto population, the responses provided to a questionnaire distributed to the population as part of the RESPONSe project were analyzed.

Due to the impossibility of administering the questionnaires using a face-to-face methodology because of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the questionnaire was administered to the population by publishing it on the website of the National Network System for Environmental Protection (SNPA). This choice, forced by the circumstances, might have influenced the type of public reached by the survey, which could have been characterized by a common interest in environmental issues, leaving behind those who do not have internet access or are not familiar with computers [66] or do not have a specific interest in the questionnaire topic [67]. Nevertheless, the high dissemination achieved may have helped flatten this bias. Indeed, online surveys have been recognized as a powerful instrument to increase the size of the sample in many research fields [68] and are becoming more and more popular in academic research [69], to the point of definitively replacing face-to-face surveys [70]. Although not being representative of the entire Venetian population (the online data collection method emphasized the group of respondents who were male and aged between 35 and 64 years), this study provides information about the perception of how geohazards are considered related to climate change by part of the adult Venetian population.

The questionnaires were collected during the period March 2020–April 2021.

The sampling method chosen for the sample sizing is the non-probabilistic per-quota method [71], selecting as a variable the residence in the Veneto Region.

The questionnaire was structured in two parts:

- Perception part, aimed at collecting information relating to the knowledge, understanding and propensity of the population to mitigate and adapt to climate change and its impacts;

- General part, aimed at outlining the demographic profile of the participants.

The questions included in the questionnaire are of four types:

- Single answer questions, for which the respondent can express only one choice;

- Multiple choice questions, for which the respondent can express more than one choice;

- Single-answer questions on a psychometric scale, for which the respondent can express an opinion more or less in agreement with a stated assumption on a “Likert” scale;

- Open questions.

The questionnaire administered to the population as part of the RESPONSe Project consists of 42 questions, 6 of which provide information relating to the perception of geohazards and were therefore selected for the realization of this study (see Appendix A).

2.2.2. Data Elaboration

The analyses were carried out to verify whether the degree of perception of the geohazards is influenced by (a) demographic characteristics, such as gender and age, (b) the proximity to the coast, and (c) the presence of other types of hazards in the surrounding area.

To verify the above hypotheses, the perception questions and the demographic questions were selected from the questionnaire created for the purposes of the RESPONSe Project. The analyzed questions are shown in Table 1 and Appendix A. It should be noted that for analytical purposes most of the questions were reclassified by the authors into fewer and broader categories, in order to facilitate the interpretation of the responses. For instance, this was the case for the multiple choice question Q6 and for the open question Q19, where the collected answers were later simplified within the four categories of hazards or impact proposed for the Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT) by the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters [72].

Table 1.

Overview of the questions of the RESPONSe perception questionnaire selected for the analysis.

To determine whether there was a correlation between the answers provided by the questionnaires (considered categorical variables, i.e., nominal or ordinal variables with less than 5 rankings), the non-parametric chi-square χ2 test for independence [73] was chosen. The chi-square test can be considered significant if the level of significance, the p-value, is lower than 0.05. For levels of p lower than 0.001 the significance of the test is extremely high. To carry out the analysis, the questions with answers on a “Likert” scale were combined in three answers: “Strongly/disagree” or “Not at all/little”; “Uncertain” or “Neutral”; “Completely agree/agree” or “Quite/very much”, depending on the formulation of the question analyzed.

Once verified, the presence of a dependence between two variables, the degree of association was evaluated using the Cramer’s V index, appropriate for variables that each have more than two values (i.e., contingency tables bigger than 2 × 2). The value of Cramer’s V is defined on the basis of the degrees of freedom (df). Depending on the degrees of freedom, different classifications are used for the Cramer’s V values [73]. For example: for two df, 0.07 corresponds to a weak degree of association, 0.21 to a medium degree of association, 0.35 to a strong degree of association [74].

Finally, for the ordinal variables, the direction of the association, positive or negative, was evaluated through the gamma index (γ) of Goodman and Kruskal. The γ index varies from −1 to 1. Values close to an absolute value of 1 indicate a strong relationship between the two variables, negative or positive. Values close to zero indicate scarcity or absence of relationship [75].

Test processing was done with the use of IBM SPSS Statistic 19 software.

As a final analysis, contingency tables were constructed to verify the degree of association between two of the variables under consideration. This methodology made it possible to evaluate the number of respondents observed for all combinations of the categories of the two variables and to determine whether the considered variables were dependent or independent of each other.

3. Results and Discussions

A total of 1233 individuals among the adult citizens of the Veneto region filled out the questionnaire. Given the number of questionnaires collected, it has been possible to assume that the response would be representative of part of the Venetian population.

The results of the climate change perception part of the questionnaire (Table 2) show that the vast majority of the respondents were male (78.2%), adults between the ages of 35 and 64 years (71.9%) and citizens that have been living in the same place for more than 20 years (92.1%). On the other hand, the distance between the percentages of respondents who live in the coastal area and those who live in the hinterland was narrower (36.6 and 63.4% respectively). According to the Italian Institute of Statistics [76], the demographic characteristics of the sample compared rather well with those of the whole population for the variables age (Q31), geographical distribution (Q32), and duration of current residence (Q33). For evaluation of the latter (Q33), the migratory balance was used as a proxy. In contrast, for the variable gender (Q30), the male respondents of the questionnaires were overabundant.

Table 2.

Answers to the general part of the questionnaires (sample size = 1233 individuals).

The results of the climate change perception part of the questionnaire (see Appendix B) show that the vast majority of the respondents is strongly worried about the climate crisis (Q1: strongly agree = 64.4%) but they are not equally certain that it is affecting the specific area where they live (Q4: strongly agree = 41.9%). Even more indecision arose among the respondents when asked if the climate risks are becoming more important than others in their region (Q20: strongly agree = 23.5%; undecided = 26.1%). This reveals a deep concern about current climate change as a global problem but also hesitation in considering it a necessarily relatable issue, possibly due to a lacking understanding of such a difficult matter. Nevertheless, according to the respondents, among all the hazards (not only climate related) that might affect the Veneto region, the utmost perceived are hydrological (Q19: 27.9%), meteorological (Q19: 19.3%) and environmental/biological (Q19: 18.4%) ones, while less concern is linked to geological hazards (Q19: 15.1%), the frequency and intensity of which are rather linked to climate change. Moreover, the changes expected in the long term are mainly changes in temperature (Q6: 13.4%), extreme weather (Q6: 12.2%), and changes to rainfall patterns (Q6: 11.2%), while increased flooding and landslides (Q6: 7.7%), drought and desertification (Q6: 7.2%), and coastal erosion (Q6: 4.9%) are left on the lower positions. This shows that while the most commonly acknowledged climate change impacts can be recognized by the citizens in their own area, it is still difficult to link them with second order effects such as the variation of the geohazards. Finally, the sectors deemed most impacted by climate change are biodiversity/ecosystem conservation (Q5: 15.9%), agriculture/breeding (Q5: 15.0%), the use and management of the territory (Q5: 13.7%), and human health (Q5: 12.6%). This implies that the perceived most impacted domain is related to the local environment, before human livelihood, settlements and even health.

To examine in depth these findings, a comparison was made between the answers to the relevant questions of the questionnaire and, wherever possible, a cross correlation with a chi-square χ2 test for independence. In the following paragraphs the most significant results for the study have been reported. All the remaining statistics are available in Appendix C for reader’s insight.

3.1. Perception of Climate Change

Table 3 and Table 4 summarize the outcomes of the chi-square χ2 test for independence performed to find a correlation of the concern caused by the climate crisis (Q1) with the perceived impact on the local territory (Q4) as well as with the sociodemographic variables related to age (Q31) and the residence area (Q32) (Table 3), and a correlation of the perceived local impact (Q4) with the perceived relevance of climate risks (Q20) as well as with the demographic variables, that are related to gender (Q30) and residence area (Q32) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Cross table of Q1 and Q4, Q31 and Q1, and Q32 and Q1 with frequencies (percentages) of the answers.

Table 4.

Cross table of Q20 and Q4, Q30 and Q4, and Q32 and Q4 with frequencies (percentages) of the answers.

The results suggest that there is a widespread perception of the climate crisis, and that the citizens who are concerned about the climate crisis are also concerned about how their region could be affected (Table 3). Indeed, the majority of the respondents appeared to agree, evenly strongly, with the proposed affirmation of apprehension over the climate crisis (Q1), regardless of their viewpoints on their surroundings and personal characteristics (Q4, and Q31, Q32). Comparably, the results evidence that a generalized recognition of climate impact on the local area (Q4) could stand in spite of differences in the recognized prominence of climate risks (Q20) or in personal characteristics (Q30, Q32) (Table 4). Nevertheless, it might be interesting to observe how the worry about the current climate crisis weakens with age, as young respondents tended to be less uncertain and doubtful of the current crisis compared to the elderly, in particular (Table 3). At the same time, gender also appeared to influence the perception of local climate impact, as males seemed slightly more uncertain in acknowledging local climate issues (Table 4). Furthermore, respondents from the coastal area appeared more concerned and less hesitant than those of the hinterland in acknowledging the ongoing climate crisis (Table 3) and the related local effects (Table 4).

Interestingly, there was a small but relevant and coherent percentage of the population (2.6–2.8%) that was not worried either for the general climate crisis or for the climate risks that are affecting their region (Table 3 and Table 4). This result is in line with a recent Eurobarometer survey carried out in the 28 Member States of the European Union by the European Commission, according to which 5% of the Italian respondents believe that climate change is not a serious problem [77].

Following, Table 5 summarizes the related measures of association (p-value, gamma and Cramer’s V). In general terms, the correlation between concern over the ongoing climate crisis (Q1) and the perception of the related local impact (Q4) was statistically highly significant (p = 0.000) with a strong and positive association (gamma = 0.844). Similarly, the correlation between the belief in the local impact of climate change (Q4) and the growing relevance of climate risks (Q20) was statistically highly significant (p = 0.000) with a strong and positive association (gamma = 0.681). In addition, the correlation between the concern about the climate crisis (Q1) and age (Q31) was very significant (p = 0.012), with a strong but negative association (gamma = −0.302). The statistical significance was still granted (p < 0.05) for all other correlated questions, although the strength of such correlations was lower, as Cramer’s V was nearly null for all of them (df = 2 for all).

Overall, the outcomes of the analysis suggest that the climate crisis and the related negative effects are a recognized issue for the local area, although the personal attributes of the respondents might influence the reported perspective. For instance, the endorsement of both authorities and general public in tackling climate change might be contributing in shaping a novel culture where climate-related issues are visible and considered a priority for action, bearing in mind that the political view can be a driver of general beliefs about the causes of climate change and its future consequences [2]. Within this context, younger generations might have been more exposed to and, as a result, more accepting of this cultural shift than older generations, who in turn might tend to remain attached to their consolidated viewpoints. Gender might play an analogous role in this case to that played when dealing with risks [23]. Women appeared more confident in recognizing the local impact of the climate crisis similarly to the general trend of being more concerned by the negative consequences of risks. Finally, the residents of coastal areas reported consistent awareness over risks and impact, possibly due to the evident effects that climate change has on marine systems and ecosystems [24]. Indeed, in such areas the occurrence of climate change might be hardly deniable, especially compared to the inner areas, where alterations might be less visible or involve phenomena that are already perceived as a threat.

3.2. Perception of Current and Future Impact of Geohazards

As already mentioned, concern about the climate crisis is growing in the younger age groups (Table 3). However, even if young people perceive the general climate crisis more, the worry and the importance given to climatic risks in the local area do not depend on age (see Appendix C). Indeed, young people, adults, and the elderly believe that the meteorological hazards are prevalent, and their impact will increase more than others (Table 6). Moreover, they all place greater uncertainties on the importance of technological/anthropogenic hazards and on the future impact on human assets. However, even if current geohazards are the second most perceived across all ages, in the long term among young people the perception of the increase in environmental impact (197) is higher than the perception of the increase in geohazards (175), while for adults and the elderly the order is the opposite.

Table 6.

Cross table of Q6 and Q31, and Q19 and Q31 with frequencies (percentages) of the answers.

Accordingly, it appears that young people tend to fear future meteoclimatic and environmental impact, despite failing to understand the link between climate change and geohazards. In this case, the experience gained by adults and the elderly during past events and disasters may have helped to enhance the perception of the increased frequency and intensity of phenomena such as floods, landslides, and coastal erosion. At the same time, a consistent consciousness of the younger generations emerges towards issues related to natural ecosystems, possibly influenced also in this case by the increasing visibility of recent informative campaigns and, in general, as a consequence of the growing environmental culture.

As previously mentioned, this study also supports the proposition that gender affects the general concern about the climate crisis in the study area. It appears that both men and women believe that the effects of meteoclimatic hazards are the most noticeable and the most high-impact in the long term, but women put geohazards in last place while men in second place (Table 7). However, it should be remembered that the number of male and female respondents is disproportionate, thus not allowing further inferences.

Table 7.

Cross table of Q6 and Q30, and Q19 and Q30 with frequencies (percentages) of the answers.

In spite of the inherent limitations of this study, these outcomes still suggest that while in the long-term the perspective of males and females converges, the present issues are perceived differently and especially the most urgent threats do not receive a common consensus. Indeed, apart from the shared concern over current and future meteoclimatic issues, geohazards appears to be acknowledged mainly by males, possibly due to the different relationship with their surroundings. These results appear to align with the available literature, that is dotted with reports on how gender actually influences the perception of risk and of personal risk [58,78,79], to the extent of altering the approach towards each phase of dealing with a disaster [80]. Nonetheless, such polarization of perception with gender is not always consistent [81] and it might also be affected by the conditions of the surrounding environment, especially in terms of exposure to recurring multiple hazards [82]. Finally, it has also been pointed out that gender might play a significant role in shaping risk perception and response due to the social construct related to it, in terms of norms, behaviors, attitudes and limitations [83].

Another interesting outcome is that the respondents who believe that their region is affected by climate change mainly expect an increase in the impact of meteorological and climatic hazards (83.3%), followed almost equally by environmental hazards (63.0%), geohazards (61.6%) and impact on human assets (59.1%) (Table 8). Nevertheless, it might also be noteworthy that the increase in meteoclimatic hazards gathers the highest common concern of all respondents, in spite of the perceived local impact of climate change (Table 8).

Table 8.

Cross table of Q4 and Q6 with frequencies (percentages) of the answers.

These results appear to further confirm that the awareness related to meteoclimatic hazards tends to be higher than that related to geohazards, even among those who do not believe that their region is affected by climate change. This might possibly be due to the occurrence of such events, that are becoming more and more relevant for local territories, with a sensible and undeniable shift toward severer tolls.

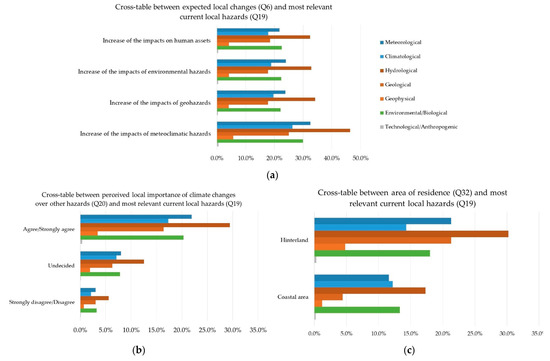

Lastly, the perception of the most relevant current local hazards (Q19) was related to the expected local changes (Q6), to the perceived local importance of climate change over other hazards (Q20) and the area of residence (Q32). Figure 3 represents the resulting cross tabulations. In general terms, hydrological hazards are perceived as the most relevant ones, regardless of the feared future effects of climate change (Figure 3a). Nevertheless, hydrological phenomena are recognized, especially by those who show awareness of future meteoclimatic impact (highest percentage, 46.4%). These same respondents also reported the highest responses to future meteorological events (highest percentage, 32.5%), although there is a shared agreement among the respondents on the relevance of these events, as meteorological events always reach the second highest percentage. The only exception are the respondents most concerned for the impact on human assets, who consider environmental and biological hazards (30.0%) as most relevant after the hydrological ones (32.4%) and before meteorological ones (21.8%). This indicates that those who are especially focused on the effects of the climate crisis also recognize the related impact on the geological and hydrological processes, whereas those who are less worried about climate change tend also to discard their secondary effects.

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of the cross tables between the perception of the most relevant current local hazards related to (a) the expected local changes (Q6 and Q19), (b) the perceived local importance of climate changes over other hazards (Q20 and Q19), and (c) the area of residence (Q32 and Q19).

The results also showed a relationship between the perception of the increasing local relevance of climate risks and of the actual relevance of geohazards (Figure 3b). Indeed, an agreement corresponded to the highest perception associated with hydrological hazards (29.4%), followed by meteorological (21.9%) and environmental/biological (20.3%) ones. In this case, while the hydrological hazards remained predominant over the others, the proportion between the meteorological and environmental/biological hazards varied progressively with the recognized relevance of climate risks, as the most cautious respondents eventually reversed the preferences (meteorological hazard 3.2%, environmental/biological hazards 3.0%). These results confirm that hesitation in recognizing climate risks tends to also conceal the consequences in terms of increased geohazard frequency and intensity.

The influence of geographical position on the selection of the relevant hazards also appears significant (Figure 3c). The respondents from the hinterland reported the highest perception of hydrological (30.2%), geological (21.3%) and meteorological (21.3%) hazards, while responses from the coastal area indicated hydrological (17.3%), environmental/biological (13.3%) and climatological (12.2%) hazards. Hence, geohazards were widely recognized by all the respondents, although hydrological phenomena received the widest agreement.

Overall, the results appear to support the interpretation that there is a significant and shared responsiveness over hydrological hazards, reasonably due to the widespread impact of extreme rainfall that affects a large portion of Veneto with increasing occurrence. Nevertheless, the proximity to hydrological and geological hazards might also play a significant role in this sense, as the respondents from the hinterland, historically more exposed to both geohazards, acknowledge more than the others the growing threat posed by such phenomena [84]. Furthermore, coastal residents reported a higher perception of the impact of climate change on environmental and biological equilibria that is consistent with the previous suggestion that these communities might be more exposed and thus aware of the current and impending alterations caused by climate change to the (marine) ecosystems [79].

3.3. The Influence of Geographic Position on the Perception of Geohazards

As previously mentioned, Veneto is highly varied in terms of morphological features, as well as of local climatic features, that significantly define different local conditions, when considering areas either farther from or nearer to the Adriatic Sea. Accordingly, it has already been suggested that depending on the area of residence (being either the coast or the hinterland) the respondents delivered different perceptions of climate change and hazards. Indeed, there is a very significant correlation between concern for climate change (Q1) and area of residence (Q32), but the association is small (Table 5). Moreover, the relation between the recognition of climate change in their own territory (Q4) and the area of residence (Q32) is significant, but the association is small (Table 5). Specifically, respondents from the coastal area evidenced a more solid acknowledgement of the climate crisis (Table 3) and of the local impact of climate change (Table 4), where respondents from the hinterland revealed a slightly higher percentage of moderate dissent. In general terms, this suggests that doubts concerning the climate crisis and its impact increase moving away from the coast. In addition, coastal respondents appear to acknowledge both geohazards and meteoclimatic hazards as relevant for their area, even though geological hazards received a rather limited recognition. In contrast, respondents residing in the hinterland indicated geohazards as the most significant, although meteorological hazards closely followed the geological ones (Figure 3a–c).

The last results related to geographical position (Table 9) concern the sectors that are considered more impacted by climate change (Q5). In general terms, the results showed an overall agreement on the most impacted sectors among all the respondents, as percentages varied slightly when considering the geographical position. In decreasing order, preferences were given to: biodiversity and ecosystem conservation (total 75.3%), agriculture and breeding (total 71.0%), use and management of the territory (total 65.1%), water resource management (total 62.1%), human health (total 59.9%). These results suggest a shared general awareness of the climate’s impact on the ecosystem-related sectors, an impact that is more significantly perceived than that on human settlements and assets, with the exception of the coastal management sector. Indeed, respondents from the coastal area assigned to this sector almost as much preferences as to human health (239 and 279 preferences, respectively), while respondents from the hinterland assigned less than half preferences to coastal management compared to human health (259 and 459 preferences, respectively).

Table 9.

Cross table of Q5 and Q32 with frequencies (percentages) of the answers.

Altogether, the results appear to confirm that geographical variables influenced how respondents perceived the changes and the threats affecting their area. In general, the proximity to the coasts of the Adriatic Sea, and thus to the related hazards, seemed to elicit a higher awareness of the detrimental consequences of climate change. Residents of the coastal areas appeared to recognize the link between the current climate crisis and the worsening of extreme events both as meteoclimatic phenomena (e.g., extreme rainfall) and geological and hydrological processes (e.g., floods). Such awareness was mirrored also by the responsiveness over the critical issues that are rising, not only in terms of degraded ecosystems but also of increased nuisances in local land management, in this case coastal management. Indeed, past events might have left a long-lasting mark in the memory of the locals, as, for instance, flood events impacted harshly on the highly urbanized plains and coasts of Veneto. At the same time, the rise of the sea level and the increased intensity of rainfall might be more evident when living in areas lying along the coastline and historically less rainy than the rest of the region. In contrast, the prospective relationship of climate change and geohazards was weaker for hinterland residents, who hesitated to accept the former but were aware of the latter. Furthermore, residents in the hinterland perceived the ongoing alterations as far from their personal life, at most affecting the environment or the human activities strictly relying on ecosystem functions (e.g., agriculture). In this case, the proximity to hazards might have significantly influenced local perception, as geological phenomena have more frequently affected inner mountainous areas, as well as recent dramatic storms and their impact on local ecosystems might still be vivid in the locals’ minds.

4. Conclusions

The consequences of the acceleration of the hydrological cycle due to a warmer atmosphere will affect the frequency of geohazards such as landslides, floods, and coastal erosion to name a few. In the near future, societies will have to face these climate-related hazards along with all the other consequences of climate change.

This study, conducted as part of the Interreg Italy–Croatia Project RESPONSe, investigates the perceptions of current and future climate change, geohazards, and the influence of geographical position on such perceptions among the citizens of the Veneto region (northeastern Italy). A total of 1233 adult citizens were reached by means of an online questionnaire. Hence, such a high number of responses provided allows us to assume that this study offers an overview on the perception of part of the adult population of the Veneto region concerning geohazards as related to climate change.

Overall, the results suggest that the majority of the respondents is strongly worried about the climate crisis, though they appear slightly undecided when asked about the area where they live. This seems in line with previous findings concerning geological risks where communities of other Italian regions indeed exhibited awareness of geohazards, though were less prone to recognize the impending threat on their own surroundings [55]. However, the residents that were more concerned about the climate crisis were also concerned about how their region could be affected and believed that climate risks were becoming more important. Consequently, this might result in being a key factor to strengthen the overall perception of local risks and thus foster local advocacy to act against them. Moreover, the concern about the climate crisis is inversely proportional to age. It appears, indeed, that young people are more focused on environmental impact, while adults and the elderly on geohazards. This could be due on the one hand to the exposure of the younger generation to a novel culture that prioritizes climate-related issues, and on the other hand to the direct experience of geohazards gained by the older generation during past events and disasters. Gender might also play a role in risk perception, since women appeared more confident in recognizing the local impact of the climate crisis. This seemingly confirms the findings of previous studies concerning tsunamis in southern Italy, where the related perception resulted higher with growing age (excluding the elderly), possibly due to the temporal distance of the last events from younger generations. At the same time, women appeared more knowledgeable of tsunami risk compared to their male counterparts [58].

Furthermore, according to the respondents, the hazards (not only climate related) feared the most are the hydrological and meteorological ones, reasonably due to the increasing and widespread impact of extreme rainfall; lower concern is linked to geological hazards. Indeed, past experiences are also reported to influence risk perception in other case studies, especially evidencing how different phenomena caused different personal awareness to the related risk [50,57,60]. The expected changes in the long term, especially by those who believe that their region is affected by climate change, are mainly meteoclimatic changes (e.g., temperature, extreme weather, rainfall patterns), while increased flooding and landslides, drought and desertification, and coastal erosion are left in the lower positions. Yet, while the most common impact from climate change can be recognized, respondents do not appear to link such phenomena with the frequency and intensity of second order effects such as geohazards.

Finally, the proximity of the respondents to hydrological and geological hazards also seems to affect the perception of the impact of climate change. Specifically, while the coastal inhabitants are more concerned about the climate crisis and recognize meteoclimatic and hydrological hazards as relevant for their area, the hinterland inhabitants indicated geohazards (both hydrological and geological) as the most significant, although meteorological hazards closely followed the geological ones. The reasons might be ascribable to the fact that, historically, the hinterland has been more exposed to geohazards, possibly leaving a significant mark in the memory of the local communities. Similar outcomes were reported in other research articles investigating a variety of natural hazards (tsunamis and flood, landslides, earthquakes, volcanoes), which highlighted a greater risk awareness by people either living near the source of the hazard [57] or having recently experienced its impact [58].

These results suggest that while the climate crisis and the related negative effects are indeed recognized issues, there is still a widespread lack of understanding of the local impact. Additionally, hesitation in recognizing climate risk tends to also conceal the consequences in terms of increased geohazard frequency and intensity. In this context, the present study proposes a distinct perspective, investigating the perception of climate change with a multihazard approach, possibly more realistic than single hazard scenarios [58], especially in the case of compound events such as those triggered by climate alterations. This approach appears particularly significant as the results suggest that the perception of climate change influences the recognition of its potential effects on local communities. Results also suggest that while geohazards are acknowledged by residents, activities may be necessary to clarify the link between such phenomena and climate change. This would be especially important as underestimating the personal condition of vulnerability might lead to an unfounded sense of security [47]. We want this study to serve as a support and stimulus to decision makers to define durable management and adaptation strategies that consider the connection between climate change and geological hazards.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.G., C.C., A.C. and F.M.; methodology, C.C. and F.Z.; analysis, E.G. and A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, E.G., C.C. and A.C.; writing—review and editing, F.Z. and F.M.; project administration, F.M.; funding acquisition, F.M. and E.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the EU INTERREG V-A IT-HR CBC Programme through the “Strategies to adapt to climate change in Adriatic regions, RESPONSe” project (ID 10046849).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data used in this study are well referenced within the article and can be accessed to generate the results presented.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Regional Agency for Environmental Protection and Prevention of Veneto for the essential contribution in the study. Moreover, we would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for the constructive comments that greatly improved the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Perception questionnaire administered to the population for the RESPONSe Project activities. The questions providing information about the perception of geohazards are in bold.

Table A1.

Perception questionnaire administered to the population for the RESPONSe Project activities. The questions providing information about the perception of geohazards are in bold.

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| Q1: I am worried about the current climate crisis | Strongly disagree |

| Disagree | |

| Undecided | |

| Agree | |

| Strongly agree | |

| Q2: The speed of current climate change is a direct consequence of human activities | Strongly disagree |

| Disagree | |

| Undecided | |

| Agree | |

| Strongly agree | |

| Q3: Sea and coasts of the Adriatic region are affected by climate change | Not at all |

| Little | |

| Neutral | |

| Quite | |

| Very much | |

| Q4: Specifically, the territory where you live is affected by climate change | Not at all |

| Little | |

| Neutral | |

| Quite | |

| Very much | |

| Q5: Which of the following sectors are impacted the most? | Agriculture/breeding |

| Biodiversity/ecosystem conservation | |

| Coastal management | |

| Emergency and rescue services | |

| Production and distribution of electricity | |

| Human health | |

| Use and management of the territory | |

| Tourism and recreation | |

| Transport and infrastructure | |

| Water resource management | |

| Industry | |

| Business | |

| Other | |

| Q6: In the long-term (over 5 years), what changes do you expect in your territory? | Sea level rise |

| Changes in temperature | |

| Increased flooding | |

| Changes to freshwater quality/access | |

| Drought and desertification | |

| Extreme weather | |

| Changes to rainfall patterns | |

| Increased pollution in the water and air | |

| Coastal erosion | |

| Ecosystem degradation | |

| Economic decline | |

| Increased costs of life | |

| Adverse impact on human health | |

| Other | |

| Q7: In your territory, which groups are more vulnerable to the impact of climate change? | Children |

| Elderly | |

| Poor | |

| Women | |

| People with special needs | |

| None | |

| Other | |

| Q8: Climate change will impact your lifestyle | Strongly disagree |

| Disagree | |

| Undecided | |

| Agree | |

| Strongly agree | |

| Q9: What do you think will have to change in your lifestyle? | [open ended question] |

| Q10: Do you think that reliable information on climate change is easily accessible? | Strongly disagree |

| Disagree | |

| Undecided | |

| Agree | |

| Strongly agree | |

| Q11: Where do you search for this information? | Television |

| Radio | |

| Newspaper | |

| Internet | |

| Academic journals/special publications | |

| Environmental forums | |

| School/University | |

| Government agencies | |

| Books | |

| Social media (non-official web pages) | |

| Family or friends | |

| Other | |

| Q12: Did you attend any educational or informative event about climate change? | Yes |

| No | |

| I do not remember | |

| Q13: If yes, which one? To whom were they addressed? | [open ended question] |

| Q14: Who organized them? | Municipality |

| Region | |

| Civil Protection | |

| I do not remember | |

| Other | |

| Q15: Scientists can effectively assess the causes and effects of climate change | Strongly disagree |

| Disagree | |

| Undecided | |

| Agree | |

| Strongly agree | |

| Q16: Public institutions can effectively respond to the challenges posed by climate change | Strongly disagree |

| Disagree | |

| Undecided | |

| Agree | |

| Strongly agree | |

| Q17: Which institutions should be involved? | Municipality |

| Associations of neighboring municipalities | |

| Region | |

| State | |

| International organizations | |

| Government agencies | |

| Environmental agencies | |

| Corporations and industries | |

| University | |

| Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) Experts/Technicians | |

| Other | |

| Q18: To be effective, mitigation strategies (e.g., to reduce pollution levels in the atmosphere) should be carried out at the following scale (MAKE A RANKING) | Local |

| Regional | |

| National | |

| European | |

| International | |

| Q19: What are the main hazards (not only climate related) in your territory? | [open ended question] |

| Q20: Climate risks are becoming more important than others in your territory | Strongly disagree |

| Disagree | |

| Undecided | |

| Agree | |

| Strongly agree | |

| Q21: The current climate crisis can be averted | Strongly disagree |

| Disagree | |

| Undecided | |

| Agree | |

| Strongly agree | |

| Q22: The current climate crisis can be resolved with technological development | Strongly disagree |

| Disagree | |

| Undecided | |

| Agree | |

| Strongly agree | |

| Q23: The impact of climate change can be reduced | Strongly disagree |

| Disagree | |

| Undecided | |

| Agree | |

| Strongly agree | |

| Q24: My lifestyle contributes to climate change | Strongly disagree |

| Disagree | |

| Undecided | |

| Agree | |

| Strongly agree | |

| Q25: The cost of mitigation (to reduce pollution levels in the atmosphere) of, and adaptation (to implement strategies to limit the effects) to climate change should be exclusively paid for by the government | Strongly disagree |

| Disagree | |

| Undecided | |

| Agree | |

| Strongly agree | |

| Q26: The effectiveness of mitigation (to reduce pollution levels in the atmosphere) and adaptation (to implement strategies to limit the effects) strategies also depend on citizens’ engagement | Strongly disagree |

| Disagree | |

| Undecided | |

| Agree | |

| Strongly agree | |

| Q27: What habits do you consider useful to mitigate (to reduce pollution levels in the atmosphere) climate change? | None |

| Use public transportation | |

| Use the bicycle | |

| Recycle | |

| Reduce consumptions | |

| Reduce the use of fuel and electricity | |

| Saving water | |

| Equip your home with alternative energy systems | |

| Other | |

| Q28: What can you do, at the individual level, to prepare for climate related hazards? | I am not willing to change my habits to prepare for climate change impact |

| Protect my assets with insurance | |

| Lower the energy consumption in my home | |

| Attend educational and informative events | |

| Change home to lower my exposure | |

| Other | |

| I am not willing to change my habits to prepare for climate change impact | |

| Q29: Can you list concrete steps that you and your family have taken to face climate change? | [open ended question] |

| Q30: Gender | Male |

| Female | |

| I prefer not to answer | |

| Q31: Age (years) | [open ended question] |

| Q32: Where do you live? | Neretva river delta (Dubrovačko-neretvanska) |

| Lignano Sabbiadoro (Friuli-Venezia Giulia) | |

| Cres (Primorsko-goranska) | |

| Montemarciano (Marche) | |

| Brindisi (Puglia) | |

| Šibenik (Šibensko-Kninska) | |

| Veneto coastal area (PD, VE, RO) | |

| Veneto hinterland (VI, TV, BL) | |

| I prefer not to answer | |

| Q33: How long have you lived there? | [open ended question] |

| Q34: Do you feel integrated in your community? | Yes |

| No | |

| I do not know | |

| I prefer not to answer | |

| Q35: How far from the coast do you live? | <200 m |

| 200–1000 m | |

| >1000 m | |

| I do not know | |

| I prefer not to answer | |

| Q36: What is the highest level of education you have completed? | Primary |

| Middle | |

| Secondary | |

| University | |

| I prefer not to answer | |

| Other | |

| Q37: What is your profession? | Lawmakers, managers and entrepreneurs (e.g., directors of large and small companies, public administration) |

| Scientists or experts (e.g., doctors, engineers, university professors…) | |

| Technicians | |

| Administrative workers | |

| Sales and service workers | |

| Craftsmen, skilled workers and farmers | |

| Plant operators, workers of stationary and mobile machines and vehicle drivers | |

| Not skilled workers | |

| Soldiers | |

| I prefer not to answer | |

| Other | |

| Q38: Will climate change impact your job? | Yes |

| No | |

| I do not know | |

| I prefer not to answer | |

| Q39: What is your nationality? | Croatian |

| Italian | |

| Other | |

| I prefer not to answer | |

| Q40: Are you the owner of the house where you live? | Yes |

| No | |

| I prefer not to answer | |

| Q41: Total family income bracket | EUR 0–15,000 |

| EUR 15,001–30,000 | |

| EUR 30,001–40,000 | |

| EUR > 40,000 | |

| I prefer not to answer | |

| Q42: Do you have children? | No |

| Yes, 0–6 years | |

| Yes, 7–17 years | |

| Yes, over 18 years | |

| I prefer not to answer |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Answers to the perception part of the questionnaires (sample size = 1233 individuals). For analytical purposes Q6 and Q19 were reclassified into fewer and broader categories.

Table A2.

Answers to the perception part of the questionnaires (sample size = 1233 individuals). For analytical purposes Q6 and Q19 were reclassified into fewer and broader categories.

| Question | Answer | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1: I am worried about the current climate crisis 1 | Strongly disagree | 20 | 1.6 |

| Disagree | 31 | 2.5 | |

| Undecided | 84 | 6.8 | |

| Agree | 301 | 24.4 | |

| Strongly agree | 797 | 64.6 | |

| Total | 1233 | 100.0 | |

| Q4: Specifically, the territory where you live is affected by climate change 1 | Not at all | 14 | 1.1 |

| Little | 40 | 3.2 | |

| Neutral | 145 | 11.8 | |

| Quite | 517 | 41.9 | |

| Very much | 517 | 41.9 | |

| Total | 1233 | 100.0 | |

| Q5: Which of the following sectors are impacted the most? 2 | Agriculture/breeding | 875 | 15.0 |

| Biodiversity/ecosystem conservation | 928 | 15.9 | |

| Coastal management | 498 | 8.5 | |

| Emergency and rescue services | 284 | 4.9 | |

| Production and distribution of electricity | 171 | 2.9 | |

| Human health | 738 | 12.6 | |

| Use and management of the territory | 802 | 13.7 | |

| Tourism and recreation | 303 | 5.2 | |

| Transport and infrastructure | 236 | 4.0 | |

| Water resource management | 765 | 13.1 | |

| Industry | 147 | 2.5 | |

| Business | 99 | 1.7 | |

| Telecommunication systems | 2 | 0.0 | |

| Residential | 2 | 0.0 | |

| Total | 5850 | 100.0 | |

| Q6: In the long-term (over 5 years), what changes do you expect in your territory? 2 | Sea level rise | 473 | 6.1 |

| Changes in temperature | 1039 | 13.4 | |

| Increased flooding and landslides | 595 | 7.7 | |

| Changes to freshwater quality/access | 347 | 4.5 | |

| Drought and desertification | 557 | 7.2 | |

| Extreme weather | 949 | 12.2 | |

| Changes to rainfall patterns | 909 | 11.7 | |

| Increased pollution in the water and air | 563 | 7.3 | |

| Coastal erosion | 380 | 4.9 | |

| Ecosystem degradation | 615 | 7.9 | |

| Economic decline | 266 | 3.4 | |

| Increased cost of living | 361 | 4.7 | |

| Adverse impact on human health | 703 | 9.1 | |

| Environmental migrations | 3 | 0.0 | |

| Total | 7760 | 100.0 | |

| Q19: What are the main hazards (not only climate related) in your territory? 3 | Geophysical | 72 | 3.5 |

| Hydrological | 577 | 27.9 | |

| Geological | 312 | 15.1 | |

| Climatological | 322 | 15.6 | |

| Meteorological | 399 | 19.3 | |

| Environmental/biological | 381 | 18.4 | |

| Technological/anthropogenic | 7 | 0.3 | |

| Total | 2070 | 100.0 | |

| Q20: Climate risks are becoming more important than others in your territory 1 | Strongly disagree | 38 | 3.1 |

| Disagree | 103 | 8.4 | |

| Undecided | 322 | 26.1 | |

| Agree | 480 | 38.9 | |

| Strongly agree | 290 | 23.5 | |

| Total | 1233 | 100.0 |

1 Likert scale. 2 Multiple choice question. 3 Open question.

Appendix C

Table A3.

Cross table of Q1 and Q30, and Q20 and Q30, with frequencies (percentages) of the answers.

Table A3.

Cross table of Q1 and Q30, and Q20 and Q30, with frequencies (percentages) of the answers.

| Q30: Gender | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Total | ||

| Q1: I am worried about the current climate crisis | Strongly disagree/disagree | 41 (3.3%) | 10 (0.8%) | 51 (4.2%) |

| Undecided | 73 (6.0%) | 11 (0.9%) | 84 (6.9%) | |

| Agree/strongly agree | 850 (69.4%) | 240 (19.6%) | 1090 (89.0%) | |

| Total | 964 (78.7%) | 261 (21.3%) | 1225 (100.0%) | |

| Q20: Climate risks are becoming more important than others in your territory | Strongly disagree/disagree | 113 (9.2%) | 27 (2.2%) | 140 (11.4%) |

| Undecided | 250 (20.4%) | 69 (5.6%) | 319 (26.0%) | |

| Agree/strongly agree | 601 (49.1%) | 165 (13.5%) | 766 (62.5%) | |

| Total | 964 (78.7%) | 261 (21.3%) | 1225 (100.0%) | |

Table A4.

Cross table of Q4 and Q31, and Q20 and Q31, with frequencies (percentages) of the answers.

Table A4.

Cross table of Q4 and Q31, and Q20 and Q31, with frequencies (percentages) of the answers.

| 31: Age | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young (18–34 Years) | Young (18–34 Years) | Young (18–34 Years) | Total | ||

| Q4: Specifically, the territory where you live is affected by climate change | Not at all/little | 4 (0.3%) | 44 (3.6%) | 6 (0.5%) | 54 (4.4%) |

| Neutral | 32 (2.6%) | 98 (7.9%) | 15 (1.2%) | 145 (11.8%) | |

| Quite/very much | 204 (16.5%) | 744 (60.3%) | 86 (7.0%) | 1034 (83.9%) | |

| Total | 240 (19.5%) | 886 (71.9%) | 107 (8.7%) | 1233 (100.0%) | |

| Q20: Climate risks are becoming more important than others in your territory | Strongly disagree/disagree | 25 (2.0%) | 103 (8.4%) | 13 (1.1%) | 141 (11.4%) |

| Undecided | 55 (4.5%) | 238 (19.3%) | 29 (2.4%) | 322 (26.1%) | |

| Agree/strongly agree | 160 (13.0%) | 545 (44.2%) | 65 (5.3%) | 770 (62.4%) | |

| Total | 240 (19.5%) | 886 (71.9%) | 107 (8.7%) | 1233 (100.0%) | |

Table A5.

Cross table of Q1 and Q33, Q4 and Q33, and Q20 and Q33, with frequencies (percentages) of the answers.

Table A5.

Cross table of Q1 and Q33, Q4 and Q33, and Q20 and Q33, with frequencies (percentages) of the answers.

| Q33: How Long Have You Lived There? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤20 Years | >20 Years | Total | ||

| Q1: I am worried about the current climate crisis | Strongly disagree/disagree | 4 (0.3%) | 47 (3.8%) | 51 (4.1%) |

| Undecided | 5 (0.4%) | 79 (6.4%) | 84 (6.8%) | |

| Agree/strongly agree | 85 (6.9%) | 1010 (82.1%) | 1095 (89.0%) | |

| Total | 94 (7.6%) | 1136 (92.4%) | 1230 (100.0%) | |

| Q4: Specifically, the territory where you live is affected by climate change | Not at all/little | 2 (0.2%) | 52 (4.2%) | 54 (4.4%) |

| Neutral | 6 (0.5%) | 139 (11.3%) | 145 (11.8%) | |

| Quite/very much | 86 (7.0%) | 945 (76.8%) | 1031 (83.8%) | |

| Total | 94 (7.6%) | 1136 (92.4%) | 1230 (100.0%) | |

| Q20: Climate risks are becoming more important than others in your territory | Strongly disagree/disagree | 6 (0.5%) | 135 (11.0%) | 141 (11.5%) |

| Undecided | 21 (1.7%) | 300 (24.4%) | 321 (26.1%) | |

| Agree/strongly agree | 67 (5.4%) | 701 (57.0%) | 768 (62.4%) | |

| Total | 94 (7.6%) | 1136 (92.4%) | 1230 (100.0%) | |

Table A6.

Summary of the measures of the chi-square χ2 test for the cross tables presented in Table A3, Table A4 and Table A5.

| p Value | Gamma | Cramer’s V | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 × Q30 | 0.150 | - | 0.056 |

| Q20 × Q30 | 0.825 | - | 0.018 |

| Q4 × Q31 | 0.157 | −0.083 | - |

| Q20 × Q31 | 0.677 | −0.075 | - |

| Q1 × Q33 | 0.833 | - | 0.017 |

| Q4 × Q33 | 0.110 | - | 0.060 |

Table A7.

Cross table of Q6 and Q33, and Q19 and Q33, with frequencies (percentages) of the answers.

Table A7.

Cross table of Q6 and Q33, and Q19 and Q33, with frequencies (percentages) of the answers.

| Q33: How Long Have You Lived There? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤20 Years | ≤20 Years | ≤20 Years | ||

| Q6: In the long-term (over 5 years), what changes do you expect in your territory? | Increase in the impact of meteoclimatic hazards | 92 (7.5%) | 1099 (89.8%) | 1191 (97.3%) |

| Increase in the impact of geohazards | 63 (5.1%) | 803 (65.6%) | 866 (70.8%) | |

| Increase in the impact of environmental hazards | 72 (5.9%) | 792 (64.7%) | 864 (70.6%) | |

| Increase in the impact on human assets | 64 (5.2%) | 765 (62.5%) | 829 (67.7%) | |

| Total | 93 (7.6%) | 1131 (92.4%) | 1224 (100.0%) | |

| Q19: What are the main hazards (not only climate related) in your territory | Meteoclimatic | 42 (4.0%) | 544 (51.3%) | 586 (55.3%) |

| Geohazards | 35 (3.3%) | 388 (36.6%) | 423 (39.9%) | |

| Environmental | 35 (3.3%) | 334 (32.5%) | 379 (35.8%) | |

| Technological/anthropogenic | 1 (0.1%) | 6 (0.6%) | 7 (0.7%) | |

| Total | 84 (7.9%) | 976 (92.1%) | 1060 (100.0%) | |

Table A8.

Cross table of Q6 and Q19, Q20 and Q19, and Q32 and Q19, with frequencies (percentages) of the answers.

Table A8.

Cross table of Q6 and Q19, Q20 and Q19, and Q32 and Q19, with frequencies (percentages) of the answers.

| Q19: What Are the Main Hazards (Not Only Climate Related) in Your Territory | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meteorological | Climatological | Hydrological | Geological | Geophysical | Environmental | Technological/Anthropogenic | Total | ||

| Q6: In the long-term (over 5 years), what changes do you expect in your territory? | Increase in the impact of meteoclimatic hazards | 393 (32.5%) | 318 (26.3%) | 560 (46.4%) | 302 (25.0%) | 69 (5.7%) | 362 (30.0%) | 7 (0.6%) | 1175 (97.3%) |

| Increase in the impact of geohazards | 288 (23.8%) | 238 (19.7%) | 413 (34.2%) | 215 (17.8%) | 50 (4.1%) | 268 (22.2%) | 4 (0.3%) | 853 (70.6%) | |

| Increase in the impact of environmental hazards | 290 (24.0%) | 228 (18.9%) | 396 (32.8%) | 215 (17.8%) | 51 (4.2%) | 271 (22.4%) | 5 (0.4%) | 851 (70.4%) | |

| Increase in the impact on human assets | 263 (21.8%) | 216 (17.9%) | 391 (32.4%) | 223 (18.5%) | 51 (4.2%) | 273 (22.6%) | 5 (0.4%) | 820 (67.9%) | |

| Total | 398 (32.9%) | 321 (26.6%) | 573 (47.4%) | 310 (25.7%) | 72 (6.0%) | 377 (31.2%) | 7 (0.6%) | 1208 (100.0%) | |

| Q20: Climate risks are becoming more important than others in your territory | Strongly disagree/disagree | 36 (3.0%) | 26 (2.1%) | 68 (5.6%) | 36 (3.0%) | 8 (0.7%) | 39 (3.2%) | 1 (0.1%) | 134 (11.0%) |

| Undecided | 97 (8.0%) | 86 (7.1%) | 152 (12.5%) | 77 (6.3%) | 23 (1.9%) | 95 (7.8%) | 1 (0.1%) | 319 (26.3%) | |

| Agree/strongly agree | 266 (21.9%) | 210 (17.3%) | 357 (29.4%) | 199 (16.4%) | 41 (3.4%) | 247 (20.3%) | 5 (0.4%) | 761 (62.7%) | |

| Total | 399 (32.9%) | 322 (26.5%) | 577 (47.5%) | 312 (25.7%) | 72 (5.9%) | 381 (31.4%) | 7 (0.6%) | 1214 (100.0%) | |

| Q32: Where do you live | Coastal area | 14 (1.2%) | 210 (17.3%) | 53 (4.4%) | 148 (12.2%) | 141 (11.6%) | 162 (13.3%) | 3 (0.2%) | 443 (36.5%) |

| Hinterland | 58 (4.8%) | 367 (30.2%) | 259 (21.3%) | 174 (14.3%) | 258 (21.3%) | 219 (18.0%) | 4 (0.3%) | 771 (63.5%) | |

| Total | 72 (5.9%) | 577 (47.5%) | 312 (25.7%) | 322 (26.5%) | 399 (32.9%) | 381 (31.4%) | 7 (0.6%) | 1214 (100.0%) | |

References

- Field, C.B.; Barros, V.; Stocker, T.F.; Dahe, Q.; Jon Dokken, D.; Ebi, K.L.; Mastrandrea, M.D.; Mach, K.J.; Plattner, G.K.; Allen, S.K.; et al. Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation: Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 9781107025. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, W.; Holmberg, K.; Hellsten, I.; Nerlich, B. Climate change on twitter: Topics, communities and conversations about the 2013 IPCC Working Group 1 report. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friesinger, S.; Bernatchez, P. Perceptions of Gulf of St. Lawrence coastal communities confronting environmental change: Hazards and adaptation, Québec, Canada. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2010, 53, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaedicke, C.; Solheim, A.; Blikra, L.H.; Stalsberg, K.; Sorteberg, A.; Aaheim, A.; Kronholm, K.; Vikhamar-Schuler, D.; Isaksen, K.; Sletten, K.; et al. Spatial and temporal variations of Norwegian geohazards in a changing climate, the GeoExtreme Project. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2008, 8, 893–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palin, E.J. Change and Geohazards in S Outh -W Est Projections, Progress and Challenges. Geosci. South-West Engl. 2012, 13, 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, A.; Culshaw, M. Implications of climate change for hazardous ground conditions in the UK. Geol. Today 2004, 20, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Michlik, L.; Espaldon, V. Assessing vulnerability of selected farming communities in the Philippines based on a behavioural model of agent’s adaptation to global environmental change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2008, 18, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcleman, R.A.; Brklacich, M.; Woodrow, M.; Vodden, K.; Gallaugher, P.; Sander-Regier, R.; Dewulf, A.; Wilby, R.L.; Benz, A.; Kemmerzell, J.; et al. Vulnerability before adaptation: Toward transformative climate action. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2012, 32, 1689–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Füssel, H.M. Vulnerability: A generally applicable conceptual framework for climate change research. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2007, 17, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovats, R.S.; Haines, A. Global climate change and health: Recent findings and future steps. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2005, 172, 501–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cutter, S.L.; Barnes, L.; Berry, M.; Burton, C.; Evans, E.; Tate, E.; Webb, J. A place-based model for understanding community resilience to natural disasters. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2008, 18, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, B.; Wandel, J. Adaptation, adaptive capacity and vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, T.W.; Bostrom, A.; Read, D.; Morgan, M.G. Now What Do People Know About Global Climate Change? Survey Studies of Educated Laypeople. Risk Anal. 2010, 30, 1520–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liarakou, G.; Athanasiadis, I.; Gavrilakis, C. What Greek secondary school students believe about climate change? Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2011, 6, 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Salvati, P.; Bianchi, C.; Fiorucci, F.; Giostrella, P.; Marchesini, I.; Guzzetti, F. Perception of flood and landslide risk in Italy: A preliminary analysis. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2014, 14, 2589–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salvati, P.; Petrucci, O.; Rossi, M.; Bianchi, C.; Pasqua, A.A.; Guzzetti, F. Gender, age and circumstances analysis of flood and landslide fatalities in Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 610–611, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierlach, E.; Belsher, B.E.; Beutler, L.E. Cross-Cultural Differences in Risk Perceptions of Disasters. Risk Anal. 2010, 30, 1539–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouter Botzen, W.J.; Van Den Bergh, J.C.J.M. Monetary valuation of insurance against flood risk under climate change. Int. Econ. Rev. 2012, 53, 1005–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundblad, E.L.; Biel, A.; Gärling, T. Cognitive and affective risk judgements related to climate change. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ameztegui, A.; Solarik, K.A.; Parkins, J.R.; Houle, D.; Messier, C.; Gravel, D. Perceptions of climate change across the Canadian forest sector: The key factors of institutional and geographical environment. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, J. Disaster Risk reduction or Climate Change Adaptatio: Are we reinventing the wheel? J. Int. Dev. 2010, 22, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, M. Geographical work at the boundaries of climate change. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2008, 33, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare. Fourth National Communication under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change; Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare: Rome, Italy, 2007. Available online: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/natc/itanc4.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Lionello, P.; Baldi, M.; Brunetti, M.; Cacciamani, C.; Maugeri, M.; Nanni, T.; Pavan, V.; Tomozieu, R.; Tomozeiu, R. Eventi climatici estremi: Tendenze attuali e clima futuro dell’Italia. In I Cambiamenti Climatici in Italia: Evidenze, Vulnerabilità e Impatti; Castellari, S., Artale, V., Eds.; Bononia University Press: Bologna, Italy, 2009; pp. 81–106. ISBN 9788873954842. [Google Scholar]

- Alvioli, M.; Melillo, M.; Guzzetti, F.; Rossi, M.; Palazzi, E.; von Hardenberg, J.; Brunetti, M.T.; Peruccacci, S. Implications of climate change on landslide hazard in Central Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 630, 1528–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gariano, S.L.; Guzzetti, F. Landslides in a changing climate. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2016, 162, 227–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Messeri, A.; Morabito, M.; Messeri, G.; Brandani, G.; Petralli, M.; Natali, F.; Grifoni, D.; Crisci, A.; Gensini, G.; Orlandini, S. Weather-Related Flood and Landslide Damage: A Risk Index for Italian Regions. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gariano, S.L.; Rianna, G.; Petrucci, O.; Guzzetti, F. Assessing future changes in the occurrence of rainfall-induced landslides at a regional scale. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 596–597, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangelantoni, L.; Gioia, E.; Marincioni, F. Impact of Climate Change on Landslides Frequency: The Esino River Basin Case Study (Central Italy). Nat. Hazards 2018, 93, 849–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rianna, G.; Reder, A.; Mercogliano, P.; Pagano, L. Evaluation of variations in frequency of landslide events affecting pyroclastic covers in Campania region under the effect of climate changes. Hydrology 2017, 4, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]