Abstract

This essay explores the value of the undergraduate English major today in terms of the knowledge and skills it develops, graduate school and employment opportunities it provides, and self-actualization and social improvement it fosters. From the perspective of an English department chair, this essay stresses both the tangible and intangible benefits of the study of literature and writing, and it does so as a defense against those that seek to cut funding or devolve English departments. With reference to data from both a small, private, liberal arts college in southern California and national sources to give context, the essay shows how the English major is not only perennially valuable, but particularly valuable today in the midst of the world-wide coronavirus pandemic and the protests that aim to arrest police brutality against African Americans and their communities.

1. Introduction

What is the value of the English major today? Over the past two years, I have had occasion to think about this question because of two key roles I have held that involved assessment of my English department at a small, private, liberal arts college in southern California. First, I was the principal investigator for our seven-year departmental review and the author of the requisite report. Then, my colleagues nominated me to be chair of the department, and unanimously voted in favor of the nomination, which the dean of the College of Arts and Sciences approved. As one of my colleagues said to me quite cheerfully at the time, having dodged that bullet himself, “No one else wants to do it!” and then hastily added, “But you’ll be great at it!”

I had to laugh. I did not want to be chair any more than my colleague—in fact, I was quite intimidated by the prospect—but I was willing to do it. That is because my entire department was under the gun, as are many English departments across the country, and we were facing the possibility of a forced merger with another department. Our dean had appointed a professor from outside our department as our chair, and there were meetings galore about “re-alignment”. All faculty stakeholders felt the stress and feared for their jobs. But when our dean departed for the position of provost at another university, we seized our golden opportunity, staged a tiny coup, and reclaimed leadership of our own department. This bold move was helped along by the actions of an outside ally: the external reviewer, who was invited to assess our department as part of our seven-year review, registered a deep level of shock that a university English department was technically being run by someone who did not hold a doctorate in our field, and he communicated this to the new interim dean. Then, voilà! I was suddenly confirmed as chair—much to my own surprise.

Now at the end of my first year of a three-year term as chair of the English department, in the midst of a university budgetary crisis brought on by the world-wide coronavirus pandemic, I am reflecting ever more deeply on how important the English major is. In fact, I continue to defend our department’s uninterrupted existence as our administration, which is wielding a sharp budgetary ax, comes ever closer to our salaries and retirement benefits (which have been reduced), our tenure-track job searches (which have been halted), and adjuncts (who have been let go). Our course loads and our class enrollment caps, meanwhile, have both been increased for next year (much to everyone’s dismay). As far as I can tell, this is quite common in the battlegrounds of higher education today, and the best we can do is defend ourselves with the wisdom, courage, and honor we have.

A number of misleading, if not downright wrong, claims have been leveled against the Humanities in general and the English major in particular about their value. Every employer wants workers who can write and communicate clearly, skills that an English major hones and develops, but the study of literature is increasingly undervalued in a society in which fewer and fewer people read books or newspapers. Those in the discipline of English itself have debated the “canon”—classic texts versus contemporary literature by a more diverse range of authors, especially women and people of color—and as a result of substantial shifts in the literature being taught, some feel that English departments are too politicized: too left-leaning in some places, too right-leaning in others. As English programs have expanded to embrace many kinds of “texts” for analysis—not just poetry, drama, fiction, and creative nonfiction, but graphic novels and motion pictures—and have increasingly fostered cultural studies to contextualize the study of literature, some wonder if the English major has lost its distinctiveness.

Meanwhile, people protest that university graduates, including English majors, cannot pay off their student-loan debt and that their debt-to-income ratio is too high upon graduation. This has become increasingly concerning as more women than men enter the English major. Women in all areas of employment in America still make less than men: an average of 82 cents to the dollar, which amounts to a $10,194 difference annually (National Partnership for Women and Families 2020)1. This “gender wage gap” is real, and when we assess the income of English graduates, the fact that women still do not make salaries comparable to those of men in our society means that female English graduates make less money than those in traditionally male-dominated professions, such as the STEM fields.

Nevertheless, English remains a viable and robust major of great value. In this essay, I will explore the value of the English major, which my colleagues and I—both at my university and beyond—are engaged in developing and sustaining for all of our students, who are truly amazing human beings. To do so, I will draw on data from my own small, private, liberal arts college in southern California as well as from national sources to give context, showing how the English major is not only perennially valuable, but particularly valuable today in the midst of the twin crises of the world-wide coronavirus pandemic and violence perpetuated against African Americans. I will discuss the real, tangible benefits of an education in English, which is what administrators so often say that they want to see assessed via measurable outcomes. But I will also discuss the real, intangible benefits, which accrue over the course of a lifetime. From knowledge and skills, to graduate school and careers, to self-actualization and social improvement, the learning obtained through the English major provides not only what students need to succeed, but what society needs to change for the better.

However imperfect we may be (and, in humility, admit that we are), those working in the field of English studies know the value of the English major. This needs to be clearly communicated to others outside of our field in order for us to be able to continue to pursue our quest: the education of the next generation. So let us begin our defense.

2. The Value of the English Major: Skills and Knowledge

Does the English major give undergraduate students the skills and knowledge to succeed in the future? The answer is, emphatically, yes (UC Davis, Stanford)2. This can be demonstrated from data obtained from local, regional, and national areas, which, in the case of my university, is data specifically from Los Angeles, California, in the United States. But this emphatic “yes” also holds true in other cities, states, and countries.

Yet when English is compared to other university majors—in the Business, Psychology, or STEM fields, for example, which appear on the surface to have more direct connections between the training provided and the graduate education or employment opportunities that come upon graduation—then the value of the English major is sometimes questioned, not only by those outside of the field, but even by those within it! (Lyman 2018)3 The explanation for this doubt, I believe, derives in part from this: the capitalistic culture of America places premium value on education that leads to money-making careers, that enrich the individual monetarily and pay dividends to society through taxes. Indeed, cultural forces within our society promote the idea that the quicker that money comes, the better.

This utilitarian attitude toward education in general and the English major in particular is ironic. First, although English majors do not make as much money in their first year or two after graduation as their STEM counterparts, they make plenty of money over the course of their working lives4. Second, as many a survey has shown, people do not derive satisfaction and happiness in life solely from making money. While poverty does have dire consequences for the individual (and society) both practically and emotionally (Payne 2005)5, graduates with a degree in the Humanities are not impoverished in their careers. It is worth noting that research shows that money made past a certain average annual salary does not increase satisfaction in work or happiness in life (Fottrell 2018)6. It turns out that people who major in fields in the Humanities, including English, not only make money but also report enjoying greater satisfaction in their work and their lives (Jaschik 2018)7. Perhaps this is partly because their training in their collegiate studies broadened their perspectives to a wider world beyond the debt-slavery of making money for the sake of the excessive lifestyles promoted in the American media.

In my own English department, we have identified key learning outcomes for students majoring in English, and these have been thoughtfully assessed and developed from “best practices” identified by the Association of Departments of English (ADE 2018), particularly in its impressive document: “A Changing Major: The Report of the 2016–2017 ADE Ad Hoc Committee on the English Major.”8 Our program learning outcomes include the expectation that, upon graduating with the English major, our students will be able to:

- Read closely, think critically, and write effectively;

- Understand the historical breadth and depth of English and American literature;

- Analyze a wide variety of literary genres (including poetry, drama, and novel);

- Apply intercultural knowledge to their study of literature.

The knowledge and skills acquired in the English major have a wide variety of applications in work and in life. When they apply what they have learned, English majors succeed.

3. The Value of the English Major: Graduate Study and Career Paths

Does the English major prepare students for graduate study and advancement in their future careers? Yes, it certainly does (American Academy of Arts and Sciences 2018)9. That said, it is worth noting that research shows American employees will hold twelve different jobs over the course of their careers (Doyle 2020)10, while experiencing unemployment or underemployment at times, sometimes directly following graduation. To address this, certain government funds for educational institutions (namely, directly federal financial aid for student scholarships and loans) are now directly tied to whether universities foster employment opportunities through Career Centers and majors that produce employable persons soon after graduation. From reports by the Association of Department of English and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the national data shows that English majors are firmly among those who do regularly find their way to graduate school and successful career paths.

During my research for our departmental review, I did a survey of our alumni to see what careers they had followed. At the same time, I did research to see what kinds of careers English majors have followed across the USA. The results aligned, and they were fascinating.

Like others majoring in Humanities disciplines, English majors have heard the old joke, “Those who can, do; those who can’t, teach”. This “joke” is both fallacious and misleading: as any teacher knows, it takes a lot of “can do” gumption and “derring-do” to teach. Aristotle actually put it differently: “Those who know, do. Those who understand, teach”. To this point can be added several others of equal or greater merit:

- “It is the supreme art of the teacher to awaken joy in creative expression and knowledge.”

- “The best teachers are those who show you where to look but don’t tell you what to see.”

- “If you have to put someone on a pedestal, put teachers. They are society’s heroes.”

- “Teaching is the one profession that creates all other professions.”11

Some English majors do become teachers at the elementary, high school or collegiate levels. Some become educational administrators. Some become educators in other fields, such as business or non-profit organizations. At the same time, as admirable a profession as teaching is, it is not the only career that English majors pursue.

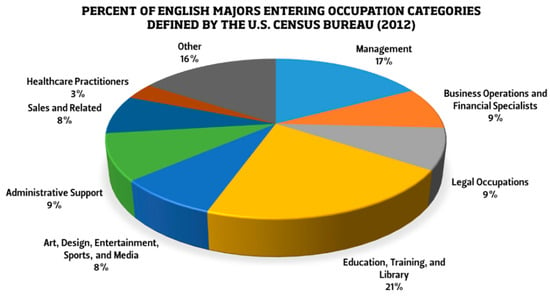

The U.S. Census Bureau has collected data in its ten-year surveys about the percentage of English majors entering different types of careers nationally, which is represented in the following graph (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Source: https://liberalarts.oregonstate.edu/what-careers-do-english-majors-pursue. See (OSU n.d.).

The diversity of professional categories is quite striking, with education, inclusive of librarianship, taking about one-fifth of the pie, while the remainder is divided between business and management, legal professions and administrative support, entertainment and media, sales and, interestingly, medicine and healthcare as well as a mysterious “other” category, which, upon investigation, includes a wide variety of jobs and professions of all kinds (OSU).

When I was conducting my English department’s seven-year review, I surveyed our alumni who had graduated with the English degree. I learned that, yes, some of our students had gone into education for their careers—and succeeded admirably. Among our respondents, we had a literature professor at Purdue University, an Assistant Superintendent of Curriculum involved in ESL programs and developing literacy, high school English and Drama teachers, and a coordinator of an after-school educational program. Retirees wrote to us about their careers in education spanning thirty-three, thirty-five, forty-one, and forty-two years. They were proud of their work and the education as English majors they received at our university that laid the foundation that prepared them to do their work. They were aware that they had made life-changing impacts on their students and had positive effects on society as well.

Our English majors not only have gone on to teach, but also have fulfilled many other career roles in other fields, such as professional writing and communication in information technology, city governance, and finance sectors, librarianship, law, social work, and psychology as well as business and management. This is an impressive array of professions. One of our alumni remarked:

“I have been fortunate enough to find myself as a professional editor and program writer, which was possible through my achievement of a Bachelors of Arts degree in English. In only two weeks after my graduation, I was able to get the job I wanted and the first thing my employer looked at was at my undergraduate degree in English. Having an extensive background in literature, analytical and critical thinking, a mastery of research and writing, and being detail-oriented has empowered me to do what I love ... Thank you for the valuable lessons and life-long learning that I have gained with this program.”(Beal 2019)

Reading comments like these from other alumni who have become librarians (like my own grandmother, who was a librarian in Portland, Oregon where she lived for over fifty years), I was reminded of comments from our graduating seniors, which we also collect in annual surveys. One of my students told me in her survey that when I took her and her classmates to the library to look at early printed editions of the Bible as part of a field trip for our course, “Literature of the Bible,” she took an immediate interest in old books. She began an internship in the library, worked in the archives, and presented her research at a conference. Upon graduation, she applied to and was accepted to a Master of Library and Information Science program. She said that my class field trip was what sparked her interest. I was amazed to realize that the English major helped her to discover her future career, and so changed her life—not to mention the people and communities she will serve in her work. It is true: the English major changes lives.

This year, as we have surveyed our English majors graduating in January and June, we learned about the plans they have, which include, among other things:

- Entering a single-subject credential program in order to teach at high school level;

- Attending graduate school in English, law, or librarianship;

- Entering the job force directly;

- Or taking a gap year to pursue personal enrichment opportunities, like travel or working to save money for future educational endeavors.

One student joined the Japanese English Teaching (JET) program and is teaching English as a second language internationally in Japan. A few went directly into substitute teaching in local school districts as they simultaneously began their credential programs. Multiple students went on to Master’s degree programs in English literature, including the one offered by Claremont Graduate University close by, while others chose graduate schools in the Midwest and on the east coast. One student received a full-ride, Sandra Day O’Connor Merit Scholarship to attend New England Law in Boston, Massachusetts. Another joined the dynamic team at Monster Energy (of Monster.com fame) after completing an internship there while still an undergraduate English major. Still another student completed an internship with the Walt Disney Company and plans to return to work there after graduation. A few students reported that they planned to take a gap year, travel outside of California, and then go to graduate school out of state. In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, one student said she would work, stay at home, and help her family. All of these decisions represent opportunity, not only for our English majors, but for our society.

4. The Value of the English Major: Self-Actualization and Social Change

Can the English major lead to self-actualization and help change society for the better? Yes, it can. We live in a world where changing the world is sometimes viewed as foolish idealism, but becoming who you are and improving society are both vital missions that give purpose to life.

The English major not only lives up to social, educational, and governmental expectations of producing employable persons, but also fosters the development of people who are self-actualized and improve society in many different ways. Many of these graduates are not famous at all, but are quietly going about their lives and making a difference for themselves, their families and friends, and those in their communities and spheres of influence. It also so happens that some English majors have attained a level of success that has made them notable public figures, and I mention them here now, as many people do not realize that these public figures were English majors (Table 1). Some readers, including current English majors, may find this list of famous English majors inspiring:

Table 1.

Famous English Majors.

As both statistical and anecdotal evidence shows, by tangible measures, the English major measures up. But it is really the intangible benefits of the English major that make it so valuable. As I was doing my research for this essay, I found a blog post written by an English major explaining her choice of major quite beautifully. The author values the knowledge and skills that make her employable across a variety of professional fields, but she goes beyond that metric to comment on self-actualization and the relationship of stories to society. Chelsey Hensley writes:

I feel my major has allowed me to possess and master certain skills sets that make me a desirable employee in many fields. Skills like critical thinking, analytical thinking, writing skills, interpersonal skills, synthetic thinking, lateral thinking, creativity and most importantly communication skills. If you can communicate with varying audiences effectively, you can do pretty much anything.But my choice to be an English major had nothing to do with the skills it would equip me with for the post-graduate job force. As a bright-eyed 18-year-old, I didn’t even consider those skills. I decided to be an English major because I loved to read. Reading allowed me to become other people, to see the world through the eyes of Bronte, Hemingway, Yeats, Milton, and Joyce. It wasn’t a form of escape, it was a way to live a life outside of my own. To experience the world and meet new people outside of my small college campus.Can you imagine a world without literature? A world without stories, letters, poems, plays, movies, song lyrics?What would be the purpose to life? To simply work, produce products, sell, consume, and die? That would be proposing a life without art, a life without symbolism, a life without humanity.Civilization is built upon stories and texts and analysis of history. We learn from the past and history is written and told; why else is it called history? From these stories, we learn to endure and to grow and to live.Our existence is meant for more than simply working and producing in order to survive. We are born to create and to enjoy and to share.(Hensley 2017)12

To these excellent points may be added points from research that shows that reading fiction fosters empathy and analyzing literature fosters critical thinking (Hammond 2019)13. More than ever before, in the midst of the world-wide coronavirus pandemic and the protests against police brutality against African Americans, we need people who can empathize with others and think critically about the social problems that we are facing so that we can bring about necessary change by working together.

Today, I recognize that we are living in a world seriously impacted by the coronavirus pandemic and by profound social unrest resulting from police brutality against African Americans. Writing at this time, I feel that I would be remiss not to mention the preventable deaths of thousands of people from COVID-19 and the protests sparked by the murders of martyrs like George Floyd, Ahmaud Aubery, and Breonna Taylor. Faced with these horrific tragedies, I remember that the knowledge and skills developed in the English major can help to bring about social change. Many English majors across the country are involved in efforts to stem the rising tide of illness and death from coronavirus. Many are involved in the protests that are seeking to bring justice and change to our society. These are amazing human beings who have learned to read literature about these issues of disease and racism before they came so forcefully to our attention once again in 2020. These are people who have studied the history of nonviolent resistance to bring about social change in America.

Personally, I am dedicated to teaching English majors for the purposes of developing their knowledge and skills and of providing opportunities to go to graduate school and pursue diverse career paths. I am also firmly committed to fostering self-actualization and social justice. For I am not only a professor of English literature and chair of an English department, I am an English major myself with a varied career path and a diverse family. I served in the healthcare field as a midwife for seven years, in major urban areas like Chicago, Denver, and San Francisco as well as in Uganda, East Africa, and I have close friends and family members who are doctors, midwives, nurses, nurse administrators, and healthcare providers involved in the fight to save lives from COVID-19. I have a brother-in-law, a sister-in-law, and nieces and nephews who are African Americans living in the San Francisco Bay Area, and I also have a brother, brother-in-law, and long-time family friend who are police officers in Oakland, California.

My heart goes out to all those affected by the current conflict and historical injustice, and I fiercely wish for an end to violence that harms people and takes their life. I love and care for all members of my family, and by extension, the whole human family. I think the world could be a different place if all people saw African Americans and police officers as their family, as I do, because in my case, they literally are! But empathy could allow anyone to see this, and critical thinking could empower people to help to make the changes in society that are needed to bring about justice for those who are being systemically oppressed. In my view, empathy and critical thinking are life-saving and society-changing. I am so glad that the English major fosters them, a key point which leads me to the conclusion that the value of the English major is perennial, but it is also particularly valuable today.

5. The Value of the English Major: Conclusions

The value of the English major is clear. Students studying English develop the skills of reading closely, thinking critically, and writing effectively. They also gain a breadth and depth of knowledge in English and American literature and, quite often, various world literary traditions, including classical mythology, biblical literature, and global literatures in English or in English translation. They learn the art of literary analysis and, often, literary criticism, so they come to understand the finer points of genre, including poetry, drama, and fictional forms, like novel and short story (and often film), and the application of intercultural knowledge to texts and life.

Rather than being esoteric knowledge, this knowledge gained by students of English proves to have great practical value in preparing individuals for graduate school and future careers in a variety of fields. The English major does not simply prepare students for one job, but for many, and this is significant when we know that American employees will hold approximately twelve jobs over the course of their careers (Doyle 2020). While about one-fifth of English majors go into teaching and librarianship, the rest find their success in business and management, sales and marketing, legal professions and government administration, psychology and social work, entertainment and media, and medicine and healthcare as well as other fields.

The English major thus produces imminently employable persons, a desirable outcome for educational, cultural, and governmental institutions. But it goes beyond this practical goal by fostering the development of people who are self-actualized and improve society. The English major particularly fosters empathy, which enables human beings to see things from someone else’s point of view and to care about perspectives different from their own. It also fosters critical thinking about social problems and ways to solve them. The challenging times in which we are living call for people trained in the English major, and other, allied majors in the Humanities (Classen forthcoming), who are not only working to better themselves and others economically, but who are working to change the world for the better.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to the University of La Verne, where I am both thankful and thrilled to be employed as a tenured, full professor and chair of the English department. I was supported in my research for our English department’s seven-year review by a course release granted by the College of Arts and Sciences; selections from relevant findings collected for that report are shared in this essay. My thanks go also to the following organizations for their research and reports as well: the Association of Departments of English, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the National Partnership for Women and Families, and the U.S. Census. I am also thankful to all survey respondents, bloggers, and other writers whose words I shared herein.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- ADE (Association of Departments of English) Ad Hoc Committee on the English Major. 2018. The Changing Major: The Report of the 2016–2017 ADE Ad Hoc Committee on the English Major. Available online: https://www.ade.mla.org/content/download/98513/2276619/A-Changing-Major.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 2018. The State of the Humanities 2018: Graduates in the Workforce and Beyond. Available online: https://www.amacad.org/sites/default/files/academy/multimedia/pdfs/publications/researchpapersmonographs/HI_Workforce-2018.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Beal, Jane. 2019. English Department Program Review Report (2011–2018). La Verne: University of La Verne. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2020. National Longitudinal Surveys FAQs. 16 January 2020 (last modified). Available online: https://www.bls.gov/nls/questions-and-answers.htm#anch41 (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Careers Advice Online. n.d. Career Change Statistics. Available online: http://careers-advice-online.com/career-change-statistics.html (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Classen, Albrecht. Forthcoming. Manifesto in Support of the Humanities: What Truly Matters in the End? Gottfried von Strazburg’s Tristan, Dante’s Divina Commedia, Boccaccio’s Decameron, Michael Ende’s Momo, and Fatih Atkin’s Soul Kitchen. Humanities 10.

- Deming, David. 2019. In the Salary Race, Engineers Spring but English Majors Endure. The New York Times. September 20. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/20/business/liberal-arts-stem-salaries.html (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Doyle, Allison. 2020. How Often Do People Change Jobs During a Lifetime? The Balance: Careers. Available online: https://www.thebalancecareers.com/how-often-do-people-change-jobs-2060467 (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Flaherty, Colleen. 2019. The Evolving English Major. Inside Higher Ed. July 18. Available online: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/07/18/new-analysis-english-departments-says-numbers-majors-are-way-down-2012-its-not-death (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Fottrell, Quentin. 2018. Psychologists say they’ve found the exact amount of money you need to be happy. MarketWatch. March 4. Available online: https://www.marketwatch.com/story/this-is-exactly-how-much-money-you-need-to-be-truly-happy-earning-more-wont-help-2018-02-14 (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Giang, Vivian, Lynne Guey, and Max Nisen. 2013. 16 Wildly Successful People Who Majored in English. Business Insider. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/successful-people-with-english-majors-2013-5#singer-sting-was-an-english-major-at-northern-counties-college-of-education-1 (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Hammond, Claudia. 2019. Does Reading Fiction Make Us Better People? BBC Future. June 2. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20190523-does-reading-fiction-make-us-better-people (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Hensley, Chelsea. 2017. In Defense of the English Major. Bookriot. March 13. Available online: https://bookriot.com/2017/03/13/in-defense-of-the-english-major/ (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Jaschik, Scott. 2018. Shocker: Humanities Grads Gainfully Employed and Happy: New Data Suggest that STEM Majors Are Not the Only Route to Success. Inside Higher Ed. Available online: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/02/07/study-finds-humanities-majors-land-jobs-and-are-happy-them (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Kolmar, Chris. 2020. 23 Celebrities with an English Major that May or May Not Surprise You. Zippia: The Career Expert, Available online: https://www.zippia.com/advice/celebrities-with-an-english-major/ (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Lyman, Paige. 2018. The Questioning Anxiety Behind Becoming an English Major. Dear English Major. March 2. Available online: http://www.dearenglishmajor.com/blog/the-questioning-anxiety-behind-becoming-an-english-major (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Mansfield University. n.d. Famous English Majors. Available online: https://www.mansfield.edu/english/why-english/famous-english-majors.cfm (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- National Partnership for Women and Families. 2020. “America’s Women and the Wage Gap” Fact Sheet. March 2020. Available online: https://www.nationalpartnership.org/our-work/resources/economic-justice/fair-pay/americas-women-and-the-wage-gap.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Newton, Derek. 2019. Studying Stem Isn’t the Career Boost We Think. Forbes. September 29. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/dereknewton/2019/09/29/studying-stem-isnt-the-career-boost-we-think/#7e052f592539 (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- OSU. n.d. A Record of Post-Graduate Success: Careers—What Careers Do English Majors Pursue? Corvallis: Oregon State University, Available online: https://liberalarts.oregonstate.edu/what-careers-do-english-majors-pursue (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Payne, Ruby. 2005. A Framework for Understanding Poverty, 4th ed. Highlands: Aha Process, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- TeachThought Staff. 2017. 50 of the Best Quotes about Teaching. TeachThought. November 17. Available online: https://www.teachthought.com/pedagogy/great-best-quotes-about-teaching/ (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- University of Arkansas, Little Rock. Department of English. n.d. Famous English Majors. Available online: https://ualr.edu/english/job-info/famous/ (accessed on 10 July 2020).

| 1 | This is the average difference, but it should be noted that women of color earn substantially less than the average: Black women make 62 cents, Native American women make 57 cents, and Hispanic women make 54 cents, compared to every dollar paid to white, non-Hispanic men. In certain areas of America, the gender wage gap is more pronounced; for example, women in Louisiana make an average of 69 cents while women in California make an average of 88 cents to a man’s dollar. See NPWF’s “America’s Women and the Wage Gap” Fact Sheet here: https://www.nationalpartnership.org/our-work/resources/economic-justice/fair-pay/americas-women-and-the-wage-gap.pdf. |

| 2 | A number of English departments at universities around the USA have begun including a page on their websites listing various studies and articles detailing how English majors acquire knowledge and skills that allow them to obtain gainful employment with salaries comparable to other university majors over time. In some cases, such university English departments pages show that majors in English and the Humanities disciplines are actually sought after over and above pre-professional and STEM majors. An excellent example of such a page, containing a series of useful references, is available from the University of California Davis: https://english.ucdavis.edu/majorminor-english/why-major-english. Other university English departments provide testimonials from their majors about their successful career paths. See Stanford: https://english.stanford.edu/information-for/undergraduates/careers-after-english-major. |

| 3 | For an example of facing the internal and external pressure of doubt about becoming an English major, and successfully overcoming it, see Paige Lyman’s blog post here: http://www.dearenglishmajor.com/blog/the-questioning-anxiety-behind-becoming-an-english-major. |

| 4 | A number of articles, published in the New York Times and Forbes magazine and elsewhere, have been written on how college graduates who majored in English make plenty of money overtime compared to their Business and STEM counterparts. See: (Deming 2019) and (Newton 2019). |

| 5 | See (Payne 2005), A Framework for Understanding Poverty, 4th rev. ed. (Highlands, TX: Aha Process, Inc.). |

| 6 | For a consideration of psychologists’ findings on this point, see: https://www.marketwatch.com/story/this-is-exactly-how-much-money-you-need-to-be-truly-happy-earning-more-wont-help-2018-02-14. |

| 7 | For the article reviewing the key study, see: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/02/07/study-finds-humanities-majors-land-jobs-and-are-happy-them. For the study itself by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, see: https://www.amacad.org/sites/default/files/academy/multimedia/pdfs/publications/researchpapersmonographs/HI_Workforce-2018.pdf. |

| 8 | A link to the ADE Report is available here: https://www.ade.mla.org/content/download/98513/2276619/A-Changing-Major.pdf. For a useful discussion of the report, see the Chronicle of Higher Education: (Flaherty 2019). |

| 9 | See the study of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences cited above, footnote 6. |

| 10 | See (Careers Advice Online n.d.). The Bureau of Labor Statistics has a report that provides research on this matter. See “Number of Jobs Held in a Lifetime” at: (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2020). |

| 11 | See (TeachThought Staff 2017). |

| 12 | Chelsea Hensley, “In Defense of the English Major,” Bookriot (13 March 2017). See https://bookriot.com/2017/03/13/in-defense-of-the-english-major/. |

| 13 | Claudia Hammond, “Does Reading Fiction Make Us Better People?” BBC Future (2 June 2019). https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20190523-does-reading-fiction-make-us-better-people. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).