Senegal, the African Slave Trade, and the Door of No Return: Giving Witness to Gorée Island

Abstract

1. Introduction

Ethos is created when writers locate themselves.—Nedra Reynolds, “Ethos as Location” (Reynolds 1993, p. 336)

A person has a past. The experiences gathered during one’s life are a part of today as well as yesterday. Memory exists in the nostrils and the hands, not only in the mind. A fragrance drifts by, and a memory is evoked. It damages people to rob them of their past and deny their memories, or to mock their fears and worries. A person without a past is incomplete.—Eric J. Cassel, “The Nature of Suffering” (Cassel 1982, p. 642)

2. Failing to See

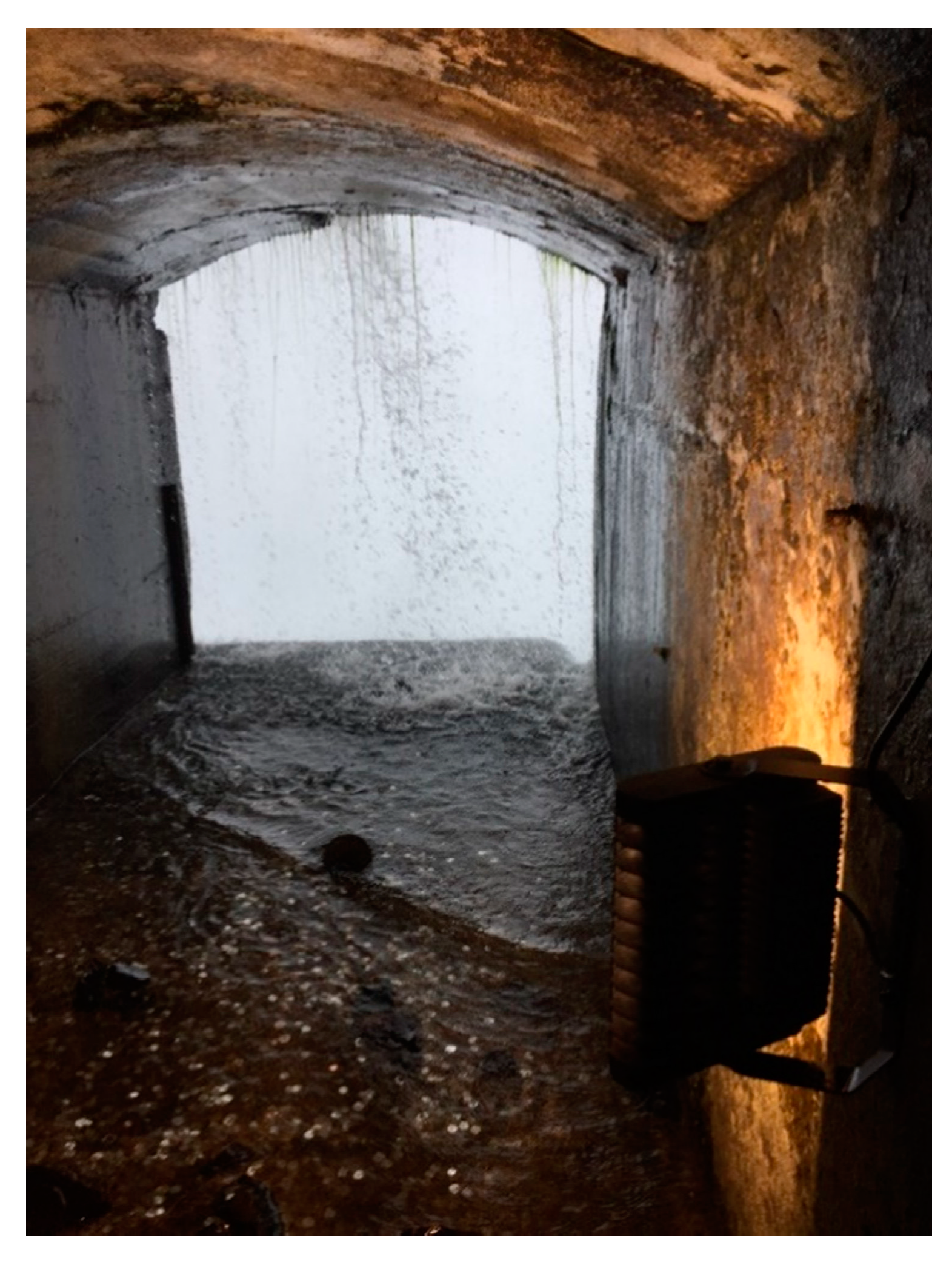

Seeing is of course very much a matter of verbalization. Unless I call my attention to what passes before my eyes, I simply will not see it. It is, as Ruskin says, “not merely unnoticed, but in the full, clear sense of the word, unseen.”—Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (Dillard 1974, p. 33)

3. Learning to See Better

[W]e presume that specific life-events—traumas for the most part—play constitutive roles in identity-formation. The abused spouse lives within an event and a narrative of that event: the abuse becomes thematic within that person’s self-image and life-story…. A further corollary to postclassical ethos … is the need to tell one’s story, particularly those aspects that bear wounds. Indeed, the highest aim of ethotic discourse is, or ought to be, to share one’s story; and, with respect to one’s functioning as audience, the highest corresponding aim is to bear witness to that other’s story.—James S. Baumlin and Craig A. Meyer, “Positioning Ethos” (Baumlin and Meyer 2018, p. 17)

To understand Senegalese ethos today, one must understand the importance of the experience of the African slave trade, which extends to the visuals, the emotions, the memories of place—that is, to the entire experience (Fixico 2003, p. 22). It is the mythos of Gorée Island and the House of Slaves that we must seek to understand. For the European bystander, it is easy to dismiss the slave trade as having happened over 100 years ago to some group at some place; it is markedly different if one’s cultural identity rests in a continual retelling—in effect, a reliving—of colonialism. As Donald L. Fixico writes, “When retold, the experience comes alive again, recreating the experience by evoking the emotions of listeners, transcending past-present-future. Time does not imprison the story” (Fixico 2003, p. 22). The telling of these stories forms an integral part of Senegalese ethos, both as-haunt and as-wound.3

Both the place and the events of the slave trade haunt the Senegalese cultural memory, which rests in the collective experience of trauma and the place—the physical haunt—of its occurrence. As such, a Senegalese ethos derives from haunt and wound. Ethos-as-haunt demonstrates how location constitutes a people, its culture, traditions, stories, and history…. Simply put, the events that occur on a parcel of land lends it character to the people of that land…. With this summary of the slave trade as a starting point, I turn now to review the Western model of ethos and its potential as haunt. From this understanding of location…. I suggest a bridge between haunt and wound as it relates to a Senegalese ethos and the hopeful healing that can take place through an acknowledgement of that woundedness. The conclusion offers insight into Senegalese wisdom for the Westernized humanities and the possibility of healing the wound from two different perspectives: European and African.4

4. Connecting Words, Images, Memories

The mythic seeks instead to unite, to synthesize, to assert wholeness in multiple or contrasting choices and interpretations. Mythos thus offers a synthetic and analogical, as opposed to analytic, mode of proof, one that discovers—indeed, celebrates—the diversity of truth.—James S. Baumlin and Tita French Baumlin, “On the Psychology of the Pisteis” (Baumlin and Baumlin 1994, p. 106)

5. Returning to Gorée

About the time the King’s soldiers came, the eldest of these four sons, Kunta, when he had about 16 rains, went away from his village to chop wood to make a drum … and he was never seen again …—Tribal story as told to Alex Haley ((Haley 1972), “My Furthest,” p. 12)

In contrast to modern notions of the person or self, [classical] ethos emphasizes the conventional rather than idiosyncratic, the public rather than the private. The most concrete meaning given for the term [ethos] in the Greek lexicon is “a habitual gathering place,” and I suspect that it is upon this image of people gathering together in a public place, sharing experiences and ideas, that its meaning as character rests.—S. Michael Halloran, “Aristotle’s Concept of Ethos” (Halloran 1982, p. 60)

6. Conclusions: Healing the Wounds of Colonialism

Ku xam’ul fa nga jëm dellu fa nga jugé (He who doesn’t know where he is heading toward should go back to where he is from).—Wolof proverb

None of us lives without a history; each of us is a narrative. We’re always standing some place in our lives, and there is always a tale of how we came to stand there, though few of us have marked carefully the dimensions of the place where we are or kept time with the tale of how we came to be there.—Jim W. Corder, “Argument as Emergence, Rhetoric as Love” (Corder 1985, p. 16)

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agence France Press. 2018. Quarante noyades en plages interdites à la baignade à Dakar. VOA Afrique. Available online: https://www.voaafrique.com/a/noyades-en-deux-mois-dans-des-plages-interdites-%C3%A0-la-baignade-%C3%A0-dakar/4509324.html (accessed on 2 September 2018).

- APA News. 2006. 2006 a été une “Année charnière” pour le Sénégal. IC/ib/APA. Available online: https://www.seneweb.com/news/Politique/2006-a-t-une-ann-e-charni-re-pour-le-s-n-gal_n_7604.html (accessed on 2 September 2019).

- Attenborough, Richard. 1982. Gandhi. Screenplay by John Briley. Culver City: Columbia Pictures. [Google Scholar]

- Attenborough, Richard. 1987. Cry Freedom. Screenplay by John Briley. Los Angeles: Universal Pictures. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, Jessica. 2003. Senegal Ferry Disaster Reveals Need for Psychological. The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Available online: https://www.ifrc.org/en/news-and-media/news-stories/africa/senegal/senegal -ferry-disaster-reveals-need-for-psychological-support/ (accessed on 2 September 2018).

- Baumlin, James S., and Tita French Baumlin. 1994. On the Psychology of the Pisteis: Mapping the Terrains of Mind and Rhetoric. In Ethos: New Essays in Rhetorical and Critical Theory. Edited by James S. Baumlin and Tita French Baumlin. Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, pp. 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Baumlin, James S., and Craig A. Meyer. 2018. Positioning Ethos in/for the Twenty-First Century: An Introduction to Histories of Ethos. Humanities 7: 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC News. 2007. The Slave Trade. Available online: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/6445941.stm#sa-link_location=more-story-2&intlink_from_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.bbc.com%2Fnews%2Fworld-africa-23078662&intlink_ts=1572437957176&story_slot=1-sa (accessed on 2 September 2018).

- Bob Marley and the Wailers. 1980. Redemption Song. In Uprising. Kingston: Tuff Gong. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchareb, Rachid. 2001. Little Senegal. Screenplay by Rachid Bouchareb and Olivier Lorelle. Berlin: 3B Productions et Taunus Film. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Julian. 2016. The Road to Soweto: Resistance and the Uprising of 16 June 1976. Auckland Park: Jacana Media. [Google Scholar]

- Cassel, Eric J. 1982. The Nature of Suffering and the Goals of Medicine. New England Journal of Medicine 306: 639–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chomsky, Marvin J. 1977. Roots. Screenplay by Alex Haley. New York: ABC Television. [Google Scholar]

- Corder, Jim W. 1985. Argument as Emergence, Rhetoric as Love. Rhetoric Review 4: 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanon, Frantz. 1952. Peau noir Masque Blancs. Paris: Les Éditions du Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Fixico, Donald. 2003. The American Indian Mind in a Linear World: American Indian Studies and Traditional Knowledge. Abingdon-on-Thames: Taylor & Francis Group. 207p, ISBN (Print)0415944562, 9780203954621. [Google Scholar]

- Fofana, Dalla Malé. 2015. La subjectivité journalistique en entrevue médiatique: une approche rhétorique et interactionnelle de l’émission Péncum Sénégal. Lettres et sciences humaines. Moissonnage: Collection moissonnée par Bibliothèques et Archives Canada. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11143/7712 (accessed on 18 November 2018).

- Fofana, Dalla Malé. 2017. Perspectives et retour sur le drame de l’émigration clandestine. Blogspot. Available online: http://dallamalefofana.blogspot.ca/2017/02/perspective-et-retour-sur-le-drame-de.html (accessed on 10 September 2018).

- Ginio, Ruth. 2008. French Colonialism Unmasked: The Vichy Years in French West Africa. Library of Congress. Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. 264p, ISBN-10 0803217463. [Google Scholar]

- Gueye, M. 2006. Un dispositif pour freiner les clandestins: Les pays d’Europe surveillent le Sénégal et la Mauritanie. Le Quotidien. Available online: http://archives.e-mauritanie.net/mauritanie-detail_la_une.php?p=2919 (accessed on 20 September 2018).

- Haley, Alex. 1972. My Furthest-Back Person—“The African”. New York Times. Section M. p. 12. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/1972/07/16/archives/my-furthestback-personthe-african.html (accessed on 18 September 2018).

- Haley, Alex. 1976. Roots: The Saga of an American Family. New York: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Halloran, S. Michael. 1982. Aristotle’s Concept of Ethos, or If Not His Somebody Else’s. Rhetoric Review 1.1: 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, Nicolas. 2018. Hundreds swim to former Senegal slave island in annual race. Aljazeera. October. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/10/hundreds-swim-senegal-slave-island-annual-race-181001080334142.html (accessed on 17 November 2018).

- Hébert, Louis. 2011. Les fonctions du langage. Signo. Available online: http://www.signosemio.com/jakobson/fonctions- du-langage.asp (accessed on 20 September 2018).

- Letort, Delphine. 2014. Rethinking the Diaspora through the Legacy of Slavery in Rachid Bouchareb’s Little Senegal. Black Camera 6.1 (Fall 2014): 139–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, Nick. 2011. The Amritsar Massacre: The Untold Story of One Fateful Day. London: (Anglais) I. B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, Fiona. 2015. There Are Seven Types of Near-Death Experiences, According to Research. Sciencealert. Available online: https://www.sciencealert.com/there-are-seven-types-of-near-death-experiences-according-to- new-research (accessed on 10 September 2018).

- Mbaye, Massamba. 2006. Moussa dieng kala, réalisateur d’un film sur l’émigration clandestine: “Les jeunes candidats au voyage me disent qu’ils sont déjà morts’’. Yekini. Available online: https://www.seneweb.com/news/Societe/moussa-dieng-kala-r-alisateur-d-un-film-sur-l-migration-clandestine-les-jeunes-candidats-au-voyage-me-disent-qu-ils-sont-d-j-morts_n_5570.html (accessed on 20 December 2018).

- Meyer, Craig A. 2019. From Wounded Knee to Sacred Circles: Oglala Lakota Ethos as “Haunt” and “Wound”. Humanities 8: 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourre, Martin. 2017. Thiaroye 1944. Histoire et Mémoire d’un Massacre Colonial. Presses Rennes: Universitaires de Rennes. [Google Scholar]

- N’diaye, Joseph. 2006. Il fut un jour à Gorée... L’esclavage raconté aux Enfants. Neuilly-sur-Seine: Michel lafon. [Google Scholar]

- N’diaye-Correard, G., and J. Schmidt. 1979. Le français au Sénégal, Enquête Lexicale. Dakar: Université de Dakar. [Google Scholar]

- Ndao, P. Alioune. 2002. Le Français au Sénégal: Une approche polynomique. Sudonline 1. Available online: http://www.sudlangues.sn/spip.php?article42 (accessed on 3 September 2018).

- Reynolds, Nedra. 1993. Ethos as Location: New Sites for Understanding Discursive Authority. Rhetoric Review 11: 325–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, Will. 2007. Slavery’s long effects on Africa. BBC News, March 29. [Google Scholar]

- Sembène, Ousmane. 1988. Camp de Thiaroye. Paris: Enaproc and Société Nouvelle Pathé Cinéma. [Google Scholar]

- Sylla, Ndongo Samba. 2017. The CFA Franc: French Monetary Imperialism in Africa. Blog Editor. Available online: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/ (accessed on 20 September 2018).

- Transport Accident Commission. 1989. If you drink, then you drive, you’re a bloody idiot, Australia. Available online: https://www.tac.vic.gov.au/ (accessed on 18 September 2018).

- UNESCO/NHK. 2019. Island of Gorée. Unesco World Heritage Centre. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/26/ (accessed on 20 September 2018).

| 1 | School trips to Gorée Island in Senegal at that time were not institutionalized. The consequence of this lack of formality is that we did not even make a phone call or register for a guided tour of the House. Moreover, we failed to show up in time for one of the daily visits. The only sneak peek some of us (the most insistent ones) could have of the place was under the pressure of a security guard who finally let us in for a very short while. A small group of two boys and three girls who came back after the big group moved away and implored on the brink of tears for the clemency of the security guide. It was July 1990. So, we obviously did not see Joseph Ndiaye, but his voice resonated in our ears in the way he would usually narrate the tragedy in that fashion that is so well rooted in the African traditional storytelling. |

| 2 | It might be somewhat puzzling for some readers to notice that I did not/could not go back to the House of Slaves, given how important it reveals itself to be for me. But one thing to bear in mind is that going back to Senegal for a month or less is a hectic experience for many of us, not compatible with the poise needed to go to that place for a proper self-examination. Back to Senegal for that short time, one literally sinks in urgent material needs as well as in concerns that have to do with families and relatives. As a matter of fact, even the locals do not feel the need to go to Gorée (repeatedly). They feel that struggling to cope with everyday life and economic problems is more relevant. Such daily hardships make a visit to Gorée a secondary concern. Besides, it is important to point out that in Africa, we do not have the culture of travelling from a place to another for sightseeing (to see “things”). We would rather do that to meet or visit relatives. As an example, most Senegalese have never been to the local zoo. On the other hand, the paradigm of Gorée Island is not a subject of common discussion in the media. The discussed topics are rather the current economic and political situation which is presented as linked to government’s actions rather than to a more remote event. Many consider relating the current situation to the Slave Trade is taking a fatalist stance. The House of Slaves therefore attracts far more foreign tourists along with diaspora, slave-descendant Black Americans than African locals. In fact, they make us remember. Coverage of high-profile visitors to the House of Slave is the only occasion for this part of our history to be mentioned in the media. And we would again see Joseph Ndiaye and hear again his firm and strong voice re-telling his well-known narration that educated locals know so well even without having been there. |

| 3 | Meyer’s original reads: To understand Oglala Lakota ethos today, one must understand the importance of the experience of this massacre, which extends to the visuals, the emotions, the memories of the scene—that is, to the entire experience (Fixico 2003, p. 22). It is the mythos of the massacre that we must seek to understand. For the EuroAmerican bystander, it is easy to dismiss the Wounded Knee Massacre as having happened over 100 years ago to some group at some place; it is markedly different if one’s cultural identity rests in a continual retelling—in effect, a reliving—of the Massacre. As Donald L. Fixico writes, “When retold, the experience comes alive again, recreating the experience by evoking the emotions of listeners, transcending past-present-future. Time does not imprison the story” (Fixico 2003, p. 22). The telling of these stories forms an integral part of Oglala ethos, both as-haunt and as-wound. (Meyer 2019, p. 4) |

| 4 | Again, Meyer’s original: Both the place and the events of the massacre haunt the Lakotan cultural memory, which rests in the collective experience of trauma and the place—the physical haunt—of its occurrence. As such, an Oglala Lakota ethos derives from haunt and wound. Ethos-as-haunt demonstrates how location constitutes a people, its culture, traditions, stories, and history…. Simply put, the events that occur on a parcel of land lends it character to the people on that land…. With this summary of the Wounded Knee Massacre as a starting point, I turn now to review the Western model of ethos and its potential as haunt. From this understanding of location, I suggest a bridge between haunt and wound as it relates to an Oglala Lakota ethos and the hopeful healing that can take place through an acknowledgement of that woundedness. The conclusion offers insight into Oglala wisdom for the Westernized humanities and the possibility of healing the wound from two different perspectives: EuroAmerican and Oglala. (Meyer 2019, p. 5) |

| 5 | Referring to Roots leads us to the Algerian film Little Senegal directed by Rachid Bouchareb (Bouchareb 2001). The theme of the movie is somewhat the opposite of Haley’s Root in the sense that the character Alloune (Sotigui Kouyaté), a tour guide at a Senegalese slave museum decided to go to America to live another more experimental dimension of the deportation, after the theoretical narration of the lave trade and the vision of a common origin. This would make him come to terms with the various realities of how African descendants feel and consider their past. He could experience the problem that we refer to with the 1956 Paris Congress of Black Writers and Artists in 1956 (see later). That trip reveals itself to be a true challenge to an “idealized view of the diaspora”, and an experience of “the real and imagined community relationship among dispersed populations” (Letort 2014, p. 142). |

| 6 | We cannot talk about Gorée Island without mentioning divergent historical readings (for further details, see Philip D. Curtin or David Eltis) of the slavery past at Gorée Island. For some historians, there is lack of requisite evidence for the House of Slaves to be considered an official site of slave deportation. Questions are indeed raised about the actual number of slaves deported or about the shoreline being possibly too rocky or not deep enough for ships to dock near the fort. These questions are certainly important for historians and specialists who need more measurable facts for the site to be considered either a cultural or a historical symbol. But African locals totally ignore and dismiss polemics and claims about the minor role (if any) of the House of Slave in the African slave trade. They consider those claims as attempts to erase this so iconic print of a crime on Mankind. In a way, they experience the same feeling as Jews in front of claims that deem Shoah to be fabricated despite many formal evidence. For Africans, since the slave trade is factual and the House of Slaves a physical symbol that connects them to its atrocities, then they would not wonder at all about how important the role it played into it. |

| 7 | Curiously, this mirrors the etymology of English “virtue,” where the Latin virtus—meaning nobility of character—derives from vir, for “man.” Hence, virtus is the quality of high and noble character associated with “manliness.” |

| 8 | Again, the myth of European superiority is real, though its expressions are often subtle. I have already mentioned political leaders who keep replicating policies dictated form Europe. We consume European entertainments—films especially—rather than make our own. And even sadder, in my opinion, are the many black Africans, women mostly, who resort to chemical products to lighten their skin. The effects of colonialism remain with us, still. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fofana, D.M. Senegal, the African Slave Trade, and the Door of No Return: Giving Witness to Gorée Island. Humanities 2020, 9, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/h9030057

Fofana DM. Senegal, the African Slave Trade, and the Door of No Return: Giving Witness to Gorée Island. Humanities. 2020; 9(3):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/h9030057

Chicago/Turabian StyleFofana, Dalla Malé. 2020. "Senegal, the African Slave Trade, and the Door of No Return: Giving Witness to Gorée Island" Humanities 9, no. 3: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/h9030057

APA StyleFofana, D. M. (2020). Senegal, the African Slave Trade, and the Door of No Return: Giving Witness to Gorée Island. Humanities, 9(3), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/h9030057