“Sing the Bones Home”: Material Memory and the Project of Freedom in M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong!

Abstract

Our entrance to the past is through memory. And water. In this case salt water. Sea water.—M. NourbeSe Philip, “Notanda”

Full fathom five thy father lies,Of his bones are coral made;Those are pearls that were his eyes;Nothing of him that doth fadeBut doth suffer a sea-changeInto something rich and strange.

Where are your monuments, your battles, martyrs?Where is your tribal memory? Sirs,in that great vault. The sea. The seahas locked them up.

Thinking with marine life fosters complex mappings of agencies and interactions in which—for humans as well as for pelagic and benthic creatures—there is, ultimately, no firm divide between mind and matter, organism and environment, self and world. Submersing ourselves, descending rather than transcending, is essential lest our tendencies toward Human exceptionalism prevent us from recognizing that... we dwell within and as part of a dynamic, intraactive, emergent, material world that demands new forms of ethical thought and practice.

1. “A Lively and Energetic Materiality”

This is what we know about those Africans thrown, jumped, dumped overboard in Middle Passage; they are with us still, in the time of the wake, known as residence time.—Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being

2. Decontamination

I begin from a position of complete distrust of language and do not believe that english (sic)—or any European language, for that matter—can truly speak our truths without the language in question being put through some sort of transformative process. A decontaminating process is probably more accurate, since a language as deeply implicated in imperialism as english has been cannot but be contaminated by such a history and experience. The only way I can then work with it is to fracture it, fragment it, dislocate it. And for me this is where form becomes so very important, because part of the transformative and decontaminating process is also to find the appropriate form for what I’m saying.(ibid., emphasis added)

Continual Reformation

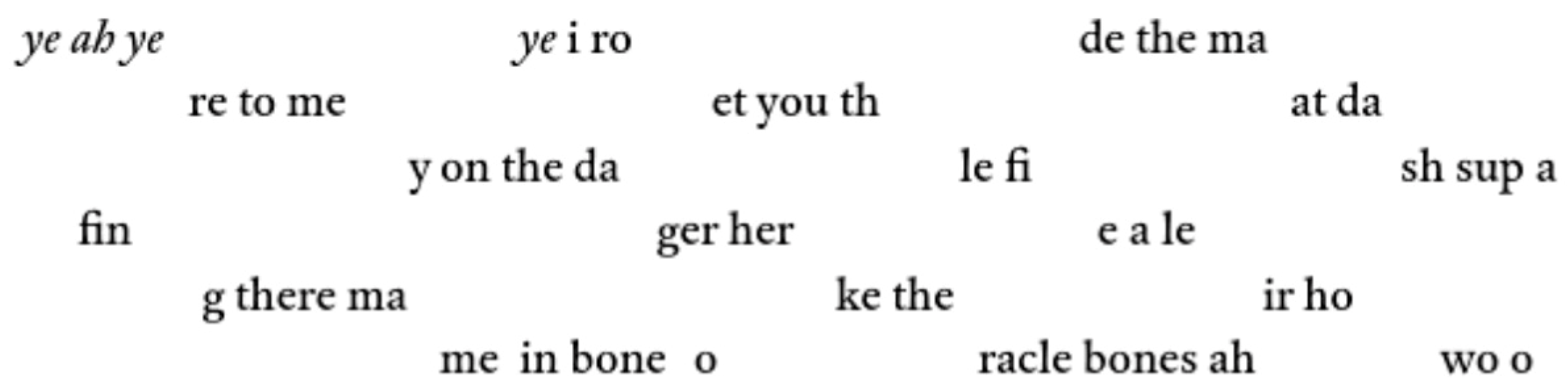

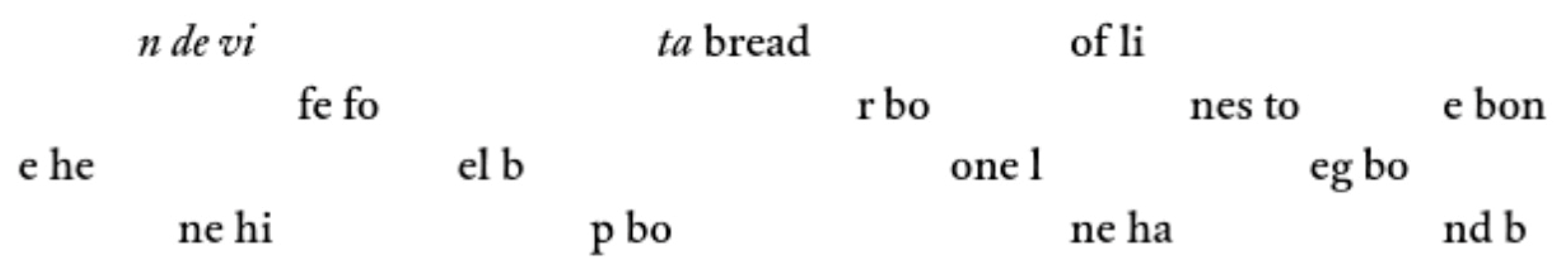

Thus, every word of the twenty-six numbered poems (and the six unnumbered poems labeled “Dicta”) in the first section of Zong!, called “Os” (Latin for “bone”), can be found in the Gregson decision. After working with (and working over) the legal discourse in this highly constrained manner, Philip has written the remaining four sections—”Sal,” “Ventus,” “Ratio,” and “Ferrum” (Latin for “salt,” “wind,” “reason,” and “iron”)—with a word store composed of the words of the decision as well as any words to be found within each of those words (each word’s imperfect anagram, that is).

3. Shoals

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alaimo, Stacy. 2011. New Materialisms, Old Humanisms, or, Following the Submersible. NORA—Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research 19: 280–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

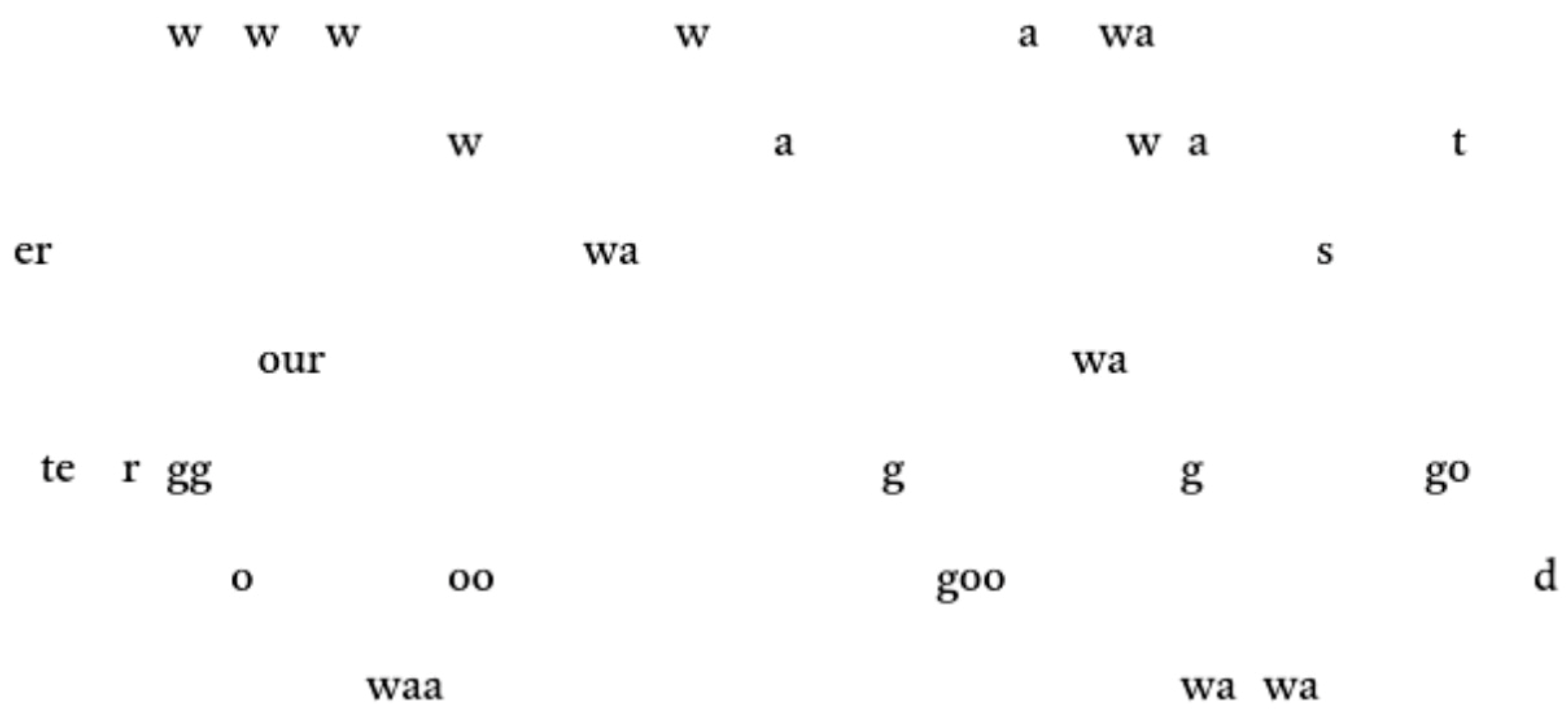

- Baraka, Amiri. 1971. SOS. In The Black Poets. Edited by Dudley Randall. Toronto: Bantam, p. 181. [Google Scholar]

- BeguilingAcronym. 2010. NourbeSe Reads from Zong! YouTube. March 22. Available online: https://youtu.be/my4eE4denus (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- Brathwaite, Edward Kamau. 1984. History of the Voice: The Development of Nation Language in Anglophone Caribbean Poetry. London: New Beacon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brathwaite, Edward Kamau. 1994. Dreamstories. Harlow: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Césaire, Aimé. 2000. A Tempest: Based on Shakespeare’s The Tempest: Adaptation for a Black Theatre. Translated by Philip Crispin. London: Oberon. First published 1969. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Coppola, Manuela. 2013. “This is, not was”: M. NourbeSe Philip’s Language of Modernity. Textus 26: 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- DeLoughrey, Elizabeth. 2009. Routes and Roots: Navigating Caribbean and Pacific Island Literatures. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- DeLoughrey, Elizabeth. 2010. Heavy Waters: Waste and Atlantic Modernity. PMLA 125: 703–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLoughrey, Elizabeth. 2017. The Oceanic Turn: Submarine Futures of the Anthropocene. In Humanities for the Environment: Integrating Knowledge, Forging New Constellations of Practice. Edited by Joni Adamson and Michael Davis. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 242–58. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, Sarah. 2011. Persons and Voices: Sounding Impossible Bodies in M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! Canadian Literature 210/211: 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Eichhorn, Kate. 2010. Multiple Registers of Silence in M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! XCP: Cross-Cultural Poetics 23: 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Eliot, Thomas Stearns. 2006. The Annotated Waste Land with Eliot’s Contemporary Prose. Edited by Lawrence Rainey. New Haven: Yale University Press. First published 1922. [Google Scholar]

- Fehskens, Erin M. 2012. Accounts Unpaid, Accounts Untold: M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! and the Catalogue. Callaloo: A Journal of African Diaspora Arts and Letters 35: 407–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervasio, Nicole. 2019. The Ruth in (T)ruth: Redactive Reading and Feminist Provocations to History in M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 30: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glissant, Édouard. 2010. Poetics of Relation. Translated by Betsy Wing. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. First published 1990. (In French by Gallimard, In English 1997). [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Douglas. 1999. In Miserable Slavery: Thomas Thistlewood in Jamaica: 1750–1786. Kingston: University of West Indies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, Saidiya. 2008. Venus in Two Acts. Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 12: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, Robert. 1985. Collected Poems. New York: Liveright Press. [Google Scholar]

- Helmreich, Stefan. 2017. The Genders of Waves. WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly 45: 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howley, Ellen. 2019. The Sea and Memory: Poetic Reconsiderations of the Zong Massacre. The Journal of Commonwealth Literature, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Zakiyyah Iman. 2015. Outer Worlds: The Persistence of Race in Movement “Beyond the Human.”. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 21: 215–81. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Lee M. 2004. The Language of Caribbean Poetry: Boundaries of Expression. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. [Google Scholar]

- Jue, Melody. 2014. Proteus and the Digital: Scalar Transformations of Seawater’s Materiality in Ocean Animations. Animation: An Interdisciplinary Journal 9: 245–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Tiffany Lethabo. 2019. The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, Laurie R. 2016. Poetics of Reparation in M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! Global South 10: 107–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, David, Luciana Martins, and Miles Ogborn. 2006. Currents, Visions and Voyages: Historical Geographies of the Sea. Journal of Historical Geography 32: 479–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, Diana. 2016a. The Mattering of Black Lives: Octavia Butler’s Hyperempathy and the Promise of the New Materialisms. Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 2: 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, Diana. 2016b. The Salt Bones: Zong! and an Ecology of Thirst. ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 23: 798–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moïse, Myriam. 2018. “Ain’t I a Woman?” Grace Nichols and M. NourbeSe Philip. Re-Membering and Healing the Black Female Body. Commonwealth Essays and Studies 40: 135–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. 2017. Summary Table of Mean Ocean Concentrations and Residence Times. MBARI.org. Available online: https://www.mbari.org/summary-table-of-mean-ocean-concentrations-and-residence-times/ (accessed on 22 August 2019).

- Moten, Fred. 2017. Black and Blur. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, Jennifer C. 2014. The Black Body in Ecstasy: Reading Race, Reading Pornography. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, Birgit, and Jan Rupp. 2016. Sea Passages: Cultural Flows in Caribbean Poetry. Atlantic Studies 13: 472–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, Grace. 1987. I Is a Long Memoried Woman. London: Karnak. [Google Scholar]

- Philip, Marlene NourbeSe. 1997. A Genealogy of Resistance: And Other Essays. Toronto: Mercury Press. [Google Scholar]

- Philip, Marlene NourbeSe. 2008. Zong! Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Philip, Marlene NourbeSe. 2017. M. NourbeSe Philip: Interview with an Empire. Lemonhound 3.0. Available online: lemonhound.com/2017/12/12/m-nourbese-philip-interview-with-an-empire/ (accessed on 17 February 2019).

- Pinnix, Aaron. 2018. Sargassum in the Black Atlantic: Entanglement and the abyss in Bearden, Walcott, and Philip. Atlantic Studies. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, Charles W. 2004. New World Modernisms: T. S. Eliot, Derek Walcott, and Kamau Brathwaite. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Quashie, Kevin Everod. 2009. The Trouble with Publicness: Toward a Theory of Black Quiet. African American Review 43: 329–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, Anthony. 2014. Freedom Time: The Poetics and Politics of Black Experimental Writing. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shakespeare, William. 2008. The Tempest. Edited by Stephen Orgel. Oxford: Oxford University Press. First published 1623. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe, Jenny. 2014. The Archive and Affective Memory in M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! Interventions 16: 465–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, Christina. 2016. In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shockley, Evie. 2011. Going Overboard: African American Poetic Innovation and the Middle Passage. Contemporary Literature 52: 791–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shujaa, Mwalimu J., and Kenya J. Shujaa, eds. 2015. The SAGE Encyclopedia of African Cultural Heritage in North America. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siklosi, Kate. 2016. “The absolute/of water”: The Submarine Poetic of M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! Canadian Literature 228–229: 111–30. [Google Scholar]

- Spillers, Hortense J. 1987. Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book. Diacritics 17: 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, Philip E. 2013. Of Other Seas: Metaphors and Materialities in Maritime Regions. Atlantic Studies 10: 156–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sub Pop. 2017. Clipping—The Deep. YouTube. August 18. Available online: https://youtu.be/zT1ujfuXFVo (accessed on 5 October 2018).

- Walcott, Derek. 1986. The Sea Is History. In Collected Poems. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, pp. 364–65. First published 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Walcott, Derek. 1990. Omeros. London: Faber and Faber. [Google Scholar]

- Walvin, James. 2011. The Zong: A Massacre, The Law, and the End of Slavery. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weheliye, Alexander. 2014. Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynter, Sylvia. 2003. Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument. CR: The New Centennial Review 3: 257–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | |

| 2 | In Elizabeth DeLoughrey’s (2017) explication of the “oceanic turn”, she comments that during the spatial turn of the 1990s “the ocean became a place for theorizing the materiality of history, yet it rarely figured as material in itself”; however, “[i]n the Caribbean the ocean has long been understood as a material entity; it is an ecology for ‘subtle and submarine’ poetics in the words of Derek Walcott” (p. 243). |

| 3 | Complementary rather than derivative, Caribbean modernisms revitalize “the Eliotic version of tradition … as a much more fluid and radical formulation, where the new text extends, qualifies, and transfigures the tradition with which it conducts its dialogue” in order to respond to the complexities of the Caribbean experience (Jenkins 2004, p. 10; Pollard 2004). Further, while both reflect an ambivalence to modernity, European and Caribbean modernisms have distinct and important ideological, aesthetic, and epistemological differences (Pollard 2004). Modernism’s aesthetic innovations are not bound to colonialism’s ideology: “Forces of colonialism shaped modernism’s initial vision, but leading postcolonial writers are reshaping its contemporary expression” (ibid.). |

| 4 | Jenkins also notes that Brathwaite’s sister, Mary Morgan, described tidealectics as “a way of interpreting [Caribbean life] and history as sea-change” (quoted in Jenkins 2004, p. 188). |

| 5 | Elizabeth DeLoughrey’s essay “Heavy Waters: Waste and Atlantic Modernity” (DeLoughrey 2010) reads Glissant’s “balls and chains gone green” as making legible Atlantic modernity’s “dissolution of wasted lives” (p. 703). |

| 6 | Philip’s challenge to both colonial language and male-centered canonical formations joins her to a genealogy of black feminist poets that includes Lorna Goodison, Grace Nichols, and Audre Lorde, who have theorized gender as key to understanding the Caribbean (Neumann and Rupp 2016). For a comparative reading of Grace Nichols and M. NourbeSe Philip’s work, see Myriam Moïse’s article “‘Ain’t I a Woman?’ Grace Nichols and M. NourbeSe Philip. Re-Membering and Healing the Black Female Body” (Moïse 2018). |

| 7 | Philip’s revisionary response may extend to Shakespeare’s The Tempest, of which she asks, “what of the Black Woman?” (Philip 1997, p. 165). Sycorax “is present only by her absence” (p. 166). |

| 8 | In The Zong, James Walvin notes that the historic record shows discrepancies in the exact number of people killed: “One report suggested a total of 150 Africans had been drowned. James Kelsall [the ship’s first mate] thought that 142 Africans had perished, but the legal hearings in London later accepted a figure of 122 murdered, in addition to the ten who had jumped to their deaths” (Walvin 2011, p. 98). Walvin’s own research suggests that number was 134. I follow Philip in using the figure of 150, because that is what is given in the legal text from which she draws (Philip 2008, p. 189). |

| 9 | A large body of criticism has considered Zong!, focusing at once on the problem of writing histories of enslavement with the language and logic of the enslavers and the poem’s experiments with form to deal with that problem. Most have argued that the poem seeks a form for “not telling”, responding to Philip’s notes to the poem that announce the story of the Zong massacre as “a story that can only be told by not telling” (Philip 2008, p. 191). Kate Eichhorn (2010) locates this dynamic in Philip’s use of constraints, arguing that the use of constraints is not merely about extending established innovative writing practices but rather allows for Philip’s central aim of “telling a story that cannot be told”. Sarah Dowling (2011) too notes that Zong! is motivated by a historiographic problem, but she focuses on how Philip’s poem attempts to write the non-person using innovative poetic forms and voices. Erin M. Fehksens argues that Zong! shows that the “epistemological crisis” of writing such a history requires a non-narrative epic mode of the catalogue. |

| 10 | In other words, due to the work the poem has done, the Gregson v. Gilbert archival document is no longer taken as a whole, stable account of the event but rather as one piece of the history that can be confronted in its entirety now that it has been decontaminated and recontextualized amid the other document(s) (Zong! itself) that the poem has put into the record. |

| 11 | Kate Siklosi and Diana Leong both focus on the sea in their readings of Zong! Siklosi (2016) locates a resistant “submarine unity” in Zong!’s “submarine poetics” that contests the Gregson v. Gilbert account of history as “singularly authoritative” by fragmenting the language of the legal decision to release “a fugue of submerged voices, sounds, silences, and stories”. Diana Leong positions the question of thirst at the center of Zong!, observing that the poem suggests “the manipulation of water is part of a long-standing strategy to police the human” (Leong 2016b, p. 799). Further, she comments that “Zong!... provides ecocritics with an opportunity to discover how the history of modern racial slavery and its afterlives is also the history of environmental politics and thought” (p. 800). Both highlight the centrality of the sea in Zong! and the conversations about history, memory, race, and the idea of the human that this focus makes possible. See also Birgit Neumann and Jan Rupp’s “Sea Passages: Cultural Flows in Caribbean Poetry” (Neumann and Rupp 2016) and Aaron Pinnix’s “Sargassum in the Black Atlantic: Entanglement and the Abyss in Bearden, Walcott, and Philip” (Pinnix 2018), both in Atlantic Studies. |

| 12 | Nicole Gervasio reads Zong! as a “radical feminist challenge to the erasure of women from most canonical formations and archival records surrounding atrocities like transatlantic slavery” through focusing on the character of Ruth (Gervasio 2019, p. 3). |

| 13 | Zakiyyah Iman Jackson (2015) points out that appeals by some post-humanists and scholars of the new materialisms to move “beyond the human” can reintroduce Eurocentric transcendentalism as attempts to move beyond race, even though “blackness conditions and constitutes the very nonhuman disruption and/or displacement they invite” (pp. 215–16, emphasis in original). Bringing this insight to an investigation of blackness and matter, Leong adds that “one of the primary figures of the new materialisms—the material body—is defined by and through disavowed social fantasies about black female flesh that are linked to the global legacies of modern slavery” and argues against “against a misrecognition of black female flesh as a resource against the violence of hierarchical differences, rather than the site of their active production” (Leong 2016a, p. 6). |

| 14 | A fifth section title, Ẹbọra, meaning “underwater spirits” in Yoruba, signals a spiritual geography of the Caribbean (Philip 2008, p. 184). |

| 15 | For more on David Dabydeen and Lorna Goodison’s desire for the “cleansing and redemption” of language, refer to Jenkins’s The Language of Caribbean Poetry: Boundaries of Expression (Jenkins 2004, p. 173). See, also, Grace Nichols’s poetry collection I Is a Long Memoried Woman (Nichols 1987). |

| 16 | Laurie Lambert shows that Philip “produces new and unexpected meanings” through fragmenting and reordering the Gregson v. Gilbert legal decision (Lambert 2016, p. 122). |

| 17 | While the sea undoes notions of gender, gendered notions of the sea have always been unstable (Helmreich 2017; DeLoughrey 2009). The female body has been conflated with land, rootedness, stability, and stasis; however, gendered conflations of men with mobility invoke “feminized flows, fluidity, and circulation”, conjuring the female borderless body and in-betweenness (much as the sea is viewed as an in-between space) (DeLoughrey 2009, p. 5; Neumann and Rupp 2016). |

| 18 | The disintegrating language points to the difficulty of speaking from an experience of profound trauma compounded by the refusal to speak as a result of that experience. The initial “w w w” evokes the stuttering attempt to begin telling what “cannot be told”. At the same time, it registers difficulty and asserts the refusal of naming the thing that brought such terror: water. Fred Moten refers to the transatlantic slave trade as the “long history of water terror that stretches from the Gold Coast to the Leeward Islands, from Birmingham to Birmingham” (Moten 2017, p. 159). Christina Sharpe argues that, in the trauma of this moment, “[l]anguage disintegrates” (Sharpe 2016, p. 69). For her, this evokes the inability to speak because the mouth is utterly dry from thirst: “Language has deserted the tongue that is thirsty” (ibid.) |

| 19 | Walvin reports that the ship had taken ten weeks to reach the Caribbean, and then, once in sight of Jamaica, the crew made a serious navigational error: they mistook Jamaica for Cape Tiburon on St. Domingue, an enemy island, and steered away from it (Walvin 2011, pp. 88, 92). |

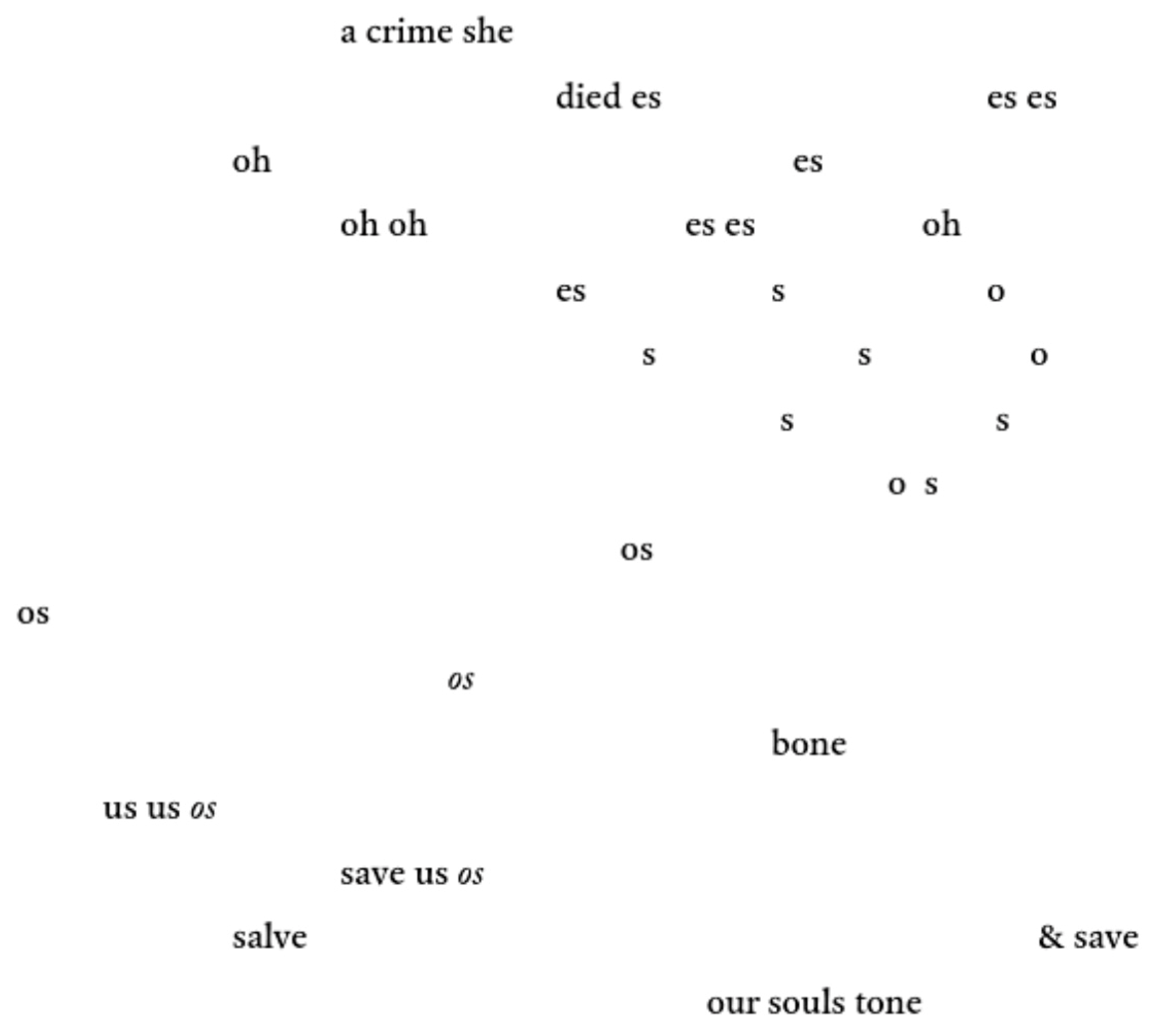

| 20 | Here, the poem may gesture to Amiri Baraka’s “SOS”:

The urgent appeal in Baraka’s “SOS”, a poem that calls “all black people” in, echoes Zong!’s own plea: “save us”. |

| 21 | Some Afrofuturistic works imagine new beings who are the descendants of drowned Africans and who have created their own communities on the floor of the ocean. See, for example, clipping.’s “The Deep” (Sub Pop 2017). |

| 22 | Brathwaite explains that “imported languages” such as the languages of “Ashanti, Congo, Yoruba, all that mighty coast of western Africa” had “to submerge themselves, because officially the conquering peoples—the Spaniards, the English, the French, the Dutch—insisted that the language of public discourse and conversation, of obedience, command and conception should be English, French, Spanish or Dutch. They did not wish to hear people speaking Ashanti or any of the Congolese languages. So there was a submergence of this imported language. Its status became one of inferiority” (Brathwaite 1984, p. 7). |

| 23 | Brathwaite continues, “What T. S. Eliot did for Caribbean poetry and Caribbean literature was to introduce the notion of the speaking voice, the conversational tone. That is what really attracted us to Eliot. And you can see how the Caribbean poets introduced here [Claude McKay, George Campbell, John Figueroa, Derek Walcott] have been influenced by him, although they eventually went on to become part of their own environmental expression” (Brathwaite 1984, pp. 30–31). He further claims that it was Eliot’s actual voice heard on recordings that drove this shift toward breaking the pentameter. Notably, T. S. Eliot is the only European influence on his poetry that Brathwaite will acknowledge (Pollard 2004, p. 2; Jenkins 2004, p. 95). |

| 24 | Per the glossary that appears at the end of Zong!, “lava lava” is West African patois for “talk” (Philip 2008, p. 184). |

| 25 | (Zong!)’s use of “rose” to refer to an enslaved African woman recalls Robert Hayden’s poem “Middle Passage” in which “That Crew and Captain lusted with the comeliest/of the savage girls kept naked in the cabins; that there was one they called The Guinea Rose” (Hayden 1985, p. 50). |

| 26 | For a more extensive comparative reading of Dabydeen’s “Turner” and Philip’s Zong! refer to Ellen Howley’s essay “The Sea and Memory: Poetic Reconsiderations of the Zong Massacre” in The Journal of Commonwealth Literature (Howley 2019). |

| 27 | |

| 28 | Wynter’s category of “Man” is emblematic of the proper “mode of being Human” (p. 260). In Leong’s reading of Zong!, she explains that “mechanisms of ‘Man’ have concentrated on establishing black populations as inferior” (Leong 2016b, p. 807). In other words, “to be ‘Man’ means to be non-black” (ibid.). |

| 29 | This brief discussion of quiet is in conversation with Kevin Everod Quashie’s theory of black quiet. He understands quiet as “a quality or a sensibility of being, as a manner of expression” of the interior, or the inner life (Quashie 2009, p. 333). As such, quiet offers a frame for understanding black culture in a “richer, fuller, more complicated [way] than a discourse of resistance can paint” (p. 339). In so doing, it “honors the contemplative quality that is also characteristic of black culture” (ibid.) In contrast with silence, which “implies something that is suppressed or repressed”, quiet, he argues, is “presence” and “can encompass and represent wild motion” (p. 334). |

| 30 | A distinguished scholarship explores the poem’s formal effects in relation to the gaps and silences in the archive of enslavement, arguing that the poem seeks to tell the story of the Zong massacre while highlighting the missing voices from the archive. See, for example, Jenny Sharpe’s “The Archive and Affective Memory in M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong!” (Sharpe 2014) and Evie Shockley’s “Going Overboard: African American Poetic Innovation and the Middle Passage” (Shockley 2011). In particular, Manuela Coppola (2013) explores how the poem “engages history rather than merely representing it” through its use of gaps and silences that “explode” language complicit in oppression and that question traditional representations of memory (pp. 67, 72). |

| 31 | In a brief reading of Zong! in Black and Blur, Moten registers Philip’s echoing “phonic remains” of “the shipped” as a quiet that is “barely audible, given only in distortion” but ongoing: “Her cryptanalytic immersion in the exhausted, mute, mutating language of animate cargo muffled by socially dead captains marks and extends this persistence” of sound in water (Moten 2017, pp. 160–1). |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fink, L. “Sing the Bones Home”: Material Memory and the Project of Freedom in M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! Humanities 2020, 9, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/h9010022

Fink L. “Sing the Bones Home”: Material Memory and the Project of Freedom in M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! Humanities. 2020; 9(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/h9010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleFink, Lisa. 2020. "“Sing the Bones Home”: Material Memory and the Project of Freedom in M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong!" Humanities 9, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/h9010022

APA StyleFink, L. (2020). “Sing the Bones Home”: Material Memory and the Project of Freedom in M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! Humanities, 9(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/h9010022