Peace with Pirates? Maghrebi Maritime Combat, Diplomacy, and Trade in English Periodical News, 1622–1714

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Preliminary Analysis

3. British Relations with the Maghreb

3.1. Power and Payments, 1622–1660

By seizing on English or Welsh, Irish or Scottish merchants and travelers, the Moors and the Turks produced an image of a dangerous “Mahumetan” world in the minds of the British reading, traveling, trading and sailing public. As a result, and instead of viewing themselves as rulers of the waves, Britons were forced to compromise with Muslims, and to negotiate and bargain, plead and appeal—even to submit to the forceful might of the corsairs.

There came lately from Algiere (a sea town in the Mediterranian, upon the African side, where is resident a Turkish Bassaw, as Governour, who hath all Turks in Command under him; the Pirates of this Town, for so they are called, because the Grand Seignior [i.e., the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire] doth not own their taking of Ships from other States) a Ship called the Charles, Commanded by Captain Will. Weildy, who brought 175 Captives redeemed out of slavery (being the second Ship that hath acted in this good work) the Captives were redeemed by monies advanced upon an Ordinance, which imposeth 5 per Cent. upon certain Merchandise; these redeemed ones attended lately the Parliament, giving them thanks for so great a favour afforded.(Moderate Intelligencer, 23–30 September 1647)10

3.2. Combat and Negotiation, 1660–1680

rival interpretations of treaty articles and difficulties determining the actual provenance of particular vessels led to regular outbreaks of violence between England and the regencies, culminating in a long and costly war with Algiers [in 1677–1682]… Although England enjoyed notable military successes, especially against Tripoli, these conflicts illustrated its inability to impose lasting terms on either Morocco or Algiers.(Stein 2015, pp. 610–11; see also Matar 2010)

that off the North Cape they met with an Algier man of War of 36 Guns, who sent their boat aboard them, and made a strict search, but that the Master of this ship and the Merchant going aboard the Turks man of War were civily Treated, and offered a supply of any necessaries they could furnish them with, excusing the strictness of the search upon several abuses put upon them by such of their Enemies as had pretended their ships and goods to have been English.(London Gazette, 29 March–1 April 1669; see also London Gazette, 10–13 May 1669)

The Seas are of late well secured from the Sally Men of War by the diligence of Captain Richard Rooth, who with the Garland and Francis Frigats cruising upon their Coasts, on the 25th of September last forced a Pink with 8 Guns and about 80 men, with her Prize, another Pink of 70 or 80 Tons, belonging to Dublin, over the Barre of Sally, within the Command of the Castle; which fired many Guns for their rescue: but the Pinks striking several times on the sands, both of them sunk upon their entrance.(London Gazette, 19–23 November 1668)16

Since my last, these following Ships were brought up hither, 7 English Ships with Sugar and Tobacco, coming from the Barbados, and two going thither; ten Laden with Fish from New-found-Land, two with Iron and Wooll, one with Hemp, Flax and Fish, one with Iron, Liquors, and other Wares, going for Guiney: The number of men on board these Ships were two hundred and ninety.(Mercurius Civicus, 22 March 1680)

3.3. Ambassadorial Splendour, 1681–1682

That the Morocco Ambassador is so well pleased with his Reception, That this morning he waited upon his Majesty, being conducted in his Majesty’s Coach to Whitehall; where he presented his Majesty with six most curious Barbary Horses. After which, he invited his Majesty into St. James’s Park, to divert himself, with seeing himself and his Attendants shoot, after the manner of their Country, which was performed with such force and exactness, in hitting a small mark at a great distance, That it was a matter of Admiration to his Majesty and all the Spectators, and exceeded the Report of their Expertness.

declaring to several Persons of quality, who have since been to wait on him, That he did not imagine England could have afforded such pleasures, much less the Greatness and Generosity he found at Newmarket and Cambridge; and having spoken much in the Honour of His Majesty, and Favours received from him, he was pleased further to add, That he thought his Royal Highness the completest Prince in the Universe; saying that nothing more remained for him to do, but to buy a quantity of English Goods, and so return to his own Country, there to Blazon as much as in him lyeth, the Greatness of the English Court throughout the World.(London Mercury, 10 April 1682; see also Domestic Intelligence, 26–30 January 1682; Loyal Protestant, and True Domestick Intelligence, 2 February, 4 February 1682)

3.4. Governed Peace, 1683–1703

By making the Mediterranean pass the basis for securing English vessels from the threat of Algerian corsairs, the treaty of 1682 established those instruments as an essential and central feature of British navigation. The Admiralty issued 789 Mediterranean passes in 1683, more than it had for the entire 1660s, and 1002 the year following.

The 28th. past arrived here the English Admiral from Algiers, having made his Peace with those Rovers; and besides the old Treaty, he has got several favourable Articles. Amongst the rest, one that the English shall sail 15 months free, without being obliged to show their Pass–ports, and all Foreign Merchandizes and persons in the said Ships shall pass unmolested; and that the Turks of Algiers shall be obliged to strike to all the Kings Ships. The Admiral has presented to the King of Algiers 50 Turkish Slaves, and the Captain of the Tiger, being a Renegade.(Loyal Protestant, and True Domestick Intelligence, 1 June 1682; see also Post Man, 29–31 August 1700)

3.5. Cooperation, Commodities, Comedy, 1704–1714

‘Tis discoursed here that the English have concluded a new Alliance with the Emperor of Morocco, who is to furnish them with Horses, &c. and the Alcaide Aly [the provincial governor near Tangier] was ordered to supply the Garrison of Gibraltar with Provisions. They add, that the Prince of Darmstat [a German ally of Britain] sent an Engineer to Compliment the Alcaide, and view the Works of the Moors against Ceuta, which he did, and ordered some Batteries to be chang’d.(Post Man, 15–17 March 1705)

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The Parliament took into consideration, the sad and deplorable condition of many hundreds of poor Christians, which have long lain under the persecution of Turkish Tyranny; and after some Debate thereupon came to this glorious Result, viz. That the Speaker be forthwith dispatched to Argier in Turkey (not the Speaker of the Hous, mistake me not; but the good ship called the Speaker) with the sum of thirty thousand pounds, to redeem poor English Captives from exile and cruell slavery: Which ship lies now at Tilbury–Hope, under the Conduct and Command of Captain Thorowgood, who hath 27 Chests of Silver aboard her, and is ready to weigh Anchor, and hoyst sayl, for the performance of this gallant Enterprise. A prosperous Gale attend his Motion; and a Christian Vote, and Blessing, be present, in all his Debates and Consultations; for, doubtless, ’tis a Sacrifice pleasing both to God and Man, and plainly denotes unto the people of England, that our Magistrates had rather buy home exiles, then make more.(Faithful Scout, 23–30 January 1652)

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akihito, Kudo, and Ota Atsushi. 2018. Privateers in the Early-Modern Mediterranean: Violence, Diplomacy and Commerce in the Maghreb, c. 1600–1830. In In the Name of the Battle Against Piracy: Ideas and Practices in State Monopoly of Maritime Violence in Europe and Asia in the Period of Transition. Edited by Ota Atsushi. Leiden: Brill, pp. 19–42. [Google Scholar]

- Andrea, Bernadette, and Linda McJannet, eds. 2011. Early Modern England and Islamic Worlds. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Auchterlonie, Paul. 2012. Encountering Islam: Joseph Pitts: An English Slave in 17th-Century Algiers and Mecca. London: Arabian Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Backman, Clifford R. 2014. Piracy. In A Companion to Mediterranean History. Edited by Peregrine Horden and Sharon Kinoshita. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 170–83. [Google Scholar]

- Bak, Greg. 2000. English Representations of Islam at the Turn of the Century: Islam Imagined and Experienced, 1575–1625. Ph.D. dissertation, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Barbano, Matteo. 2018. A lucrative, dangerous business: le consulat anglais à Alger, Tunis et Tripoli dans la deuxième moitié du XVIIe siècle. In De L’utilité Commerciale des Consuls. L’institution Consulaire et les Marchands dans le Monde Méditerranéen (XVIIe-XXe Siècle). Edited by Arnaud Bartolomei, Guillaume Calafat, Mathieu Grenet and Jörg Ulbert. Rome: École Française de Rome, pp. 253–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels, Emily C. 2008. Speaking of the Moor from Alcazar to Othello. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beijit, Karim. 2015. English Colonial Texts on Tangier, 1661–1684: Imperialism and the Politics of Resistance. Farnham: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Rejeb, Lofti. 2012. “The General Belief of the World”: Barbary as genre and discourse in Mediterranean history. European Review of History: Revue européenne d’histoire 19: 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, Helen. 2000. An Early Coffee House Periodical and its Readers: The Athenian Mercury, 1691–1697. London Journal 25: 14–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birchwood, Matthew, and Matthew Dimmock. 2005. Introduction. In Cultural Encounters Between East and West, 1453–1699. Edited by Matthew Birchwood and Matthew Dimmock. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Press, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Birchwood, Matthew. 2005. News from Vienna: Titus Oates and the True Protestant Turk. In Cultural Encounters Between East and West, 1453–1699. Edited by Matthew Birchwood and Matthew Dimmock. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Press, pp. 64–76. [Google Scholar]

- Birchwood, Matthew. 2007. Staging Islam in England: Drama and Culture, 1640–1685. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer. [Google Scholar]

- Black, Jeremy. 2001. British Diplomats and Diplomacy 1688–1800. Exeter: University of Exeter Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.A.O.C. 2008. Anglo-Moroccan Relations and the Embassy of Ahmad Qardanash, 1706–1708. Historical Journal 51: 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, Jonathan. 2005. Traffic and Turning: Islam and English Drama, 1579–1624. Newark: University of Delaware Press. [Google Scholar]

- Calafat, Guillaume. 2011. Ottoman North Africa and ius publicus europaeum: The case of the treaties of peace and trade (1600–1750). In War, Trade and Neutrality: Europe and the Mediterranean in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Edited by Antonella Alimento. Milan: Franco Angelli, pp. 171–86. [Google Scholar]

- Chaney, Eric. 2015. Measuring the military decline of the Western Islamic World: Evidence from Barbary ransoms. Explorations in Economic History 58: 107–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, John. 1987. The Sales of Government Gazettes during the Exclusion Crisis, 1678–81. English Historical Review 102: 103–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çirakman, Asli. 2005. From the "Terror of the World" to the "Sick Man of Europe": European Images of Ottoman Empire and Society from the Sixteenth Century to the Nineteenth. New York: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan, Brian. 2004. The Rise of the Coffeehouse Reconsidered. Historical Journal 47: 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, Nat. 2018. Turks, Moors, Deys and Kingdoms: North African Diversity in English News before 1700. Melbourne Historical Journal 46: 61–84. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Robert C. 2009. Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: Tales of Christian-Muslim Slavery in the Early-Modern Mediterranean. Santa Barbara: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Dimmock, Matthew. 2016. New Turkes: Dramatising Islam and the Ottomans in Early Modern England. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ellinghausen, Laurie. 2018. Pirates, Traitors, and Apostates: Renegade Identities in Early Modern English Writing. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Erzini, Nadia. 2002. Moroccan-British Diplomatic and Commercial Relations in the Early 18th Century: The Abortive Embassy to Meknes in 1718. (Durham Middle East Paper 70). Durham: University of Durham Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, Adam. 2002. Oral and Literate Culture in England 1500–1700. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ghobrial, John-Paul. 2013. The Whispers of Cities: Information Flows in Istanbul, London, and Paris in the Age of William Trumbull. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glaisyer, Natasha. 2017. The Most Universal Intelligencers: The circulation of the London Gazette in the 1690s. Media History 23: 256–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guasco, Michael. 2014. Slaves and Englishmen: Human Bondage in the Early Modern Atlantic World. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Handover, P. M. 1965. A History of the London Gazette 1665–1965. London: HM Stationery Office. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, Mark G. 2015. Pirate Nests and the Rise of the British Empire, 1570–1740. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Helgason, Þorsteinn. 2018. The Corsairs’ Longest Voyage: The Turkish Raid in Iceland 1627. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Hershenzon, Daniel. 2018. Slavery, Communication, and Commerce in Early Modern Spain and the Mediterranean. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heywood, Colin. 2007. Ideology and the profit motive in the Algerine Corso: The strange case of the Isabella of Kirkcaldy. In Anglo-Saxons in the Mediterranean: Commerce, Politics and Ideas (XVII-XX Centuries). Edited by C. Vassallo and M. D’Angelo. Malta: Malta University Press, pp. 17–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, F. Robert. 1999. Rethinking Europe’s Conquest of North Africa and the Middle East: The opening of the Maghreb, 1660–1814. Journal of North African Studies 4: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang Degenhardt, Jane. 2010. Islamic Conversion and Christian Resistance on the Early Modern Stage. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, Wolfgang, and Guillaume Calafat. 2014. Violence, Protection and Commerce: Corsairing and ars piratica in the Early Modern Mediterranean. In Persistent Piracy: Maritime Violence and State-Formation in Global Historical Perspective. Edited by Stefan Eklöf Amirell and Leos Müller. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 69–92. [Google Scholar]

- Klarer, Mario, ed. 2019. Piracy and Captivity in the Mediterranean, 1550–1810. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Leask, Nigel. 2019. Eighteenth-Century Travel Writing. In The Cambridge History of Travel Writing. Edited by Nandini Das and Tim Young. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 93–107. [Google Scholar]

- Lofkrantz, Jennifer, and Olatunji Ojo, eds. 2016. Ransoming, Captivity & Piracy in Africa and the Mediterranean. Trenton: Africa World Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lunsford, Virginia West. 2005. Piracy and Privateering in the Golden Age Netherlands. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Maclean, Gerald. 1995. Culture and Society in the Stuart Restoration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maclean, Gerald. 2007. Looking East: English Writing and the Ottoman Empire before 1800. Houndmills: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Maclean, Gerald. 2019. Early Modern Travel Writing (1): Print and Early Modern European Travel Writing. In The Cambridge History of Travel Writing. Edited by Nandini Das and Tim Young. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 62–76. [Google Scholar]

- Matar, Nabil. 1999. Turks, Moors, and Englishmen in the Age of Discovery. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Matar, Nabil. 2001a. The Barbary Corsairs, King Charles I and the Civil War. Seventeenth Century 16: 239–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matar, Nabil. 2001b. Introduction: England and Mediterranean Captivity, 1577–1704. In Piracy, Slavery, and Redemption. Edited by Daniel J. Vitkus. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Matar, Nabil. 2003. The Last Moors: Maghāriba in Early Eighteenth-Century Britain. Journal of Islamic Studies 14: 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matar, Nabil. 2005. Britain and Barbary, 1589–1689. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. [Google Scholar]

- Matar, Nabil. 2008. Islam in Britain, 1689–1750. Journal of British Studies 47: 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matar, Nabil. 2010. The Maghariba and the Sea: Maritime Decline in North Africa in the Early Modern Period. In Trade and Cultural Exchange in the Early Modern Mediterranean: Braudel’s Maritime Legacy. Edited by Maria Fusaro, Colin Heywood and Mohamed-Salah Omri. London: I.B. Tauris, pp. 117–39. [Google Scholar]

- Matar, Nabil. 2013. Morocco and Britain during the War of the Spanish Succession. Hespéris-Tamuda 48: 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Matar, Nabil. 2014. British Captives from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic, 1563–1760. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- McCluskey, Phillip. 2009. Commerce before Crusade? France, The Ottoman Empire and the Barbary Pirates (1661–1669). French History 23: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McJannet, Linda. 2006. The Sultan Speaks: Dialogue in English Plays and Histories about the Ottoman Empire. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, Allan R. 1977. Beeswax and Politics in Morocco, 1697–1701. Bee World 58: 153–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrice, Roger. 2009. The Entring Book of Roger Morrice [1677–1691]. Edited by Mark Goldie. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, Theresa Denise. 2006. From Baltimore to Barbary: The 1631 Sack of Baltimore. History Ireland 14: 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Carolyn, and Matthew Seccombe. 1987. British Newspapers and Periodicals 1641–1700. New York: Modern Language Association of America. [Google Scholar]

- Panzac, Daniel. 2005. Barbary Corsairs: The End of a Legend 1800–1820. Translated by Victoria Hobson, and John E. Hawkes. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, Kenneth. 2004. Reading Barbary in Early Modern England, 1550–1685. Seventeenth Century 19: 87–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, Clive, ed. 1969–1980. Consolidated Treaty Series. New York: Oceana Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Pepys, Samuel. 1660–1669. Diary. Available online: https://www.pepysdiary.com (accessed on 13 November 2019).

- Raymond, Joad. 1998. The newspaper, public opinion, and the public sphere in the seventeenth century. Prose Studies 21: 109–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, Joad. 2011a. Introduction: The Origins of Popular Print Culture. In The Oxford History of Popular Print Culture, Volume 1: Cheap Print in Britain and Ireland to 1660. Edited by Joad Raymond. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, Joad. 2011b. News. In The Oxford History of Popular Print Culture, Volume 1: Cheap Print in Britain and Ireland to 1660. Edited by Joad Raymond. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 377–97. [Google Scholar]

- Rech, Walter. 2019. Ambivalences of recognition: The position of the Barbary corsairs in early modern international law and international politics. In Piracy and Captivity in the Mediterranean 1550–1810. Edited by Mario Klarer. London: Routledge, pp. 76–98. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Benedict S. 2007. Islam and Early Modern English Literature: The Politics of Romance from Spenser to Milton. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Sisneros, Katie. 2016. “The Abhorred Name of Turk”: Muslims and the Politics of Identity in Seventeenth-Century English Broadside Ballads. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Tristan M. 2012. The Mediterranean in the English Empire of Trade, 1660–1748. Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, Harvard, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Tristan. 2015. Passes and Protection in the Making of a British Mediterranean. Journal of British Studies 54: 602–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, James. 1986. The Restoration Newspaper and Its Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, Ann. 1987. Barbary and Enlightenment: European Attitudes towards the Maghreb in the 18th Century. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, Judith E. 2019. Piracy of the Eighteenth-Century Mediterranean: Navigating Laws and Legal Practices. In The Making of the Modern Mediterranean: Views from the South. Edited by Judith E. Tucker. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 123–48. [Google Scholar]

- Vitkus, Daniel J. 1999. Early Modern Orientalism: Representations of Islam in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Europe. In Western Views of Islam in Medieval and Early Modern Europe: Perception of Other. Edited by David R. Blacks and Michael Frassetto. New York: St. Martin’s Press, pp. 207–30. [Google Scholar]

- Vitkus, Daniel. 2003. Turning Turk: English Theatre and the Multicultural Mediterranean, 1570–1630. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Waite, Gary K. 2019. Jews and Muslims in Seventeenth-Century Discourse: From Religious Enemies to Allies and Friends. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Keith. 1977. The English Newspaper. London: Springwood Books. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | It is instructive, in light of analysis below, that the same naval term ‘man of war’ is being used for both enemies and friends. |

| 2 | (Nabil Matar 1999, pp. 5–18, 170) argues that this essentialising discourse, drawing heavily on colonialist perceptions of Amerindians, actually strengthened over the seventeenth and eighteenth century, before reaching its fullest form in nineteenth-century Orientalism. Both Ann (Thomson 1987, pp. 1–32; Asli Çirakman 2005, pp. 2–3) perceive a linear movement from sixteenth-century ignorance to nineteenth-century Orientalism. |

| 3 | To this assessment may be added another “side-glance” use of newspapers in the discussion of seventeenth-century Maghrebi corsairing: Michael Guasco, Slaves and Englishmen: Human Bondage in the Early Modern Atlantic World (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014), 126; and the more significant use of the London Gazette in relation to Istanbul in Ghobrial, Whispers of Cities, pp. 122–58. |

| 4 | I have used the term ‘printed periodicals’ deliberately to exclude once-off news pamphlets and manuscript newsletters, and to focus on those publications which were designed to provide a regular, consistent and reliable flow of news to their readers. |

| 5 | London Gazette available at https://www.thegazette.co.uk; Burney Collection available at https://www.gale.com/uk/c/17th-and-18th-century-burney-newspapers-collection; Nichols Collection available at https://www.gale.com/c/17th-and-18th-century-nichols-newspapers-collection. |

| 6 | This paper will not consider land warfare against European presidios in the Maghreb, relations among Maghrebi states or between Maghrebi states and the Ottoman Empire, or local Maghrebi news, though there is significant evidence that British newspapers reported on these events as well–see (Cutter 2018, pp. 76, 78–81). |

| 7 | Since in most cases, maritime combat was ongoing, and presented as retaliation or precaution against the others’ aggressions, I have chosen to organise the cases based on the instigator, and in cases where the instigator is unclear, the eventual victor. The aggressor count also includes references to naval preparations intended against the opposing side, even when framed as retaliation. |

| 8 | In both these cases, I have taken a somewhat broad definition: ‘diplomacy’ includes all references to intended or actual diplomatic activity, as well as references to Maghrebi diplomats engaging in less strictly diplomatic activities while in Europe; and ‘peaceful trade’ includes references ranging from brief reports of Italian merchant ships arriving with messages from Tunis up to page-long treatments of the advantages of trade with the Maghreb. |

| 9 | Algerian corsairs even ventured as far north as Iceland (Helgason 2018). |

| 10 | It is instructive to note the careful definition of ‘pirate’ here, which allows that they might be considered legitimate privateers if England had recognised Algiers as an autonomous state, rather than a subordinate province of the Ottoman Empire; the status of Algiers in English opinion was to change rapidly after the Restoration. See also Faithful Scout, 23–30 January 1652. |

| 11 | The French observed a similar diplomatic pattern in the 1660s (McCluskey 2009). |

| 12 | London Gazette, 13–17 April 1676, point XIX contains a reasonably summary of article XIX in the original treaty included in (Parry 1969–1980, vol. 14, pp. 79–80). See also Kingdomes Intelligencer, 23–30 June 1662, which contains a broadly faithful summary of the 1662 treaty with Algiers, cf. Parry 1969–80, 7: 175–79. |

| 13 | Of course, in reality it is hardly like that all ‘the people’ of Tunis desired ‘nothing more’ than peace with the English; this presentation clearly exaggerates diplomatic niceties for popular audiences. |

| 14 | The definitive article on Mediterranean passes and their role in British relations with the Maghrebi states is (Stein 2015). |

| 15 | (Matar 2005, pp. 150–58) has recognised a similar trend, ’a wide interest in eyewitness accounts and [a] deep-seated desire to valorize British warriors and annihilate the unnamed and unknown Moors’, in a small flurry of accounts relating to Tangier that appeared around 1680. |

| 16 | Other examples include London Gazette, 22–26 September, 3–6 October, 3–7 November 1670, 29 December 1670–1672 January 1671, 30 January–2 February 1671, 23–27 September 1675, 23–27 March 1676, 8–12 November 1677, 25–29 April 1678, 9–12 May, 23–27 June, 3–7 November 1681; Current Intelligence 1–5 November 1681; Impartial Protestant Mercury 4–8 November 1681, 28 February–2 March 1682. |

| 17 | In contrast to the accuracy clearly represented in newspaper sources, Matar’s analysis of Elkanah Settle’s (admittedly very inaccurate) play The Heir of Morocco leads him to conclude that ‘although Bin Haddu was creating much excitement at court and in the city, he was not generating interest in accuracy’ (Matar 2005, p. 161). See also (Birchwood and Dimmock 2005, pp. 3–5). |

| 18 | The latter was likely a political move: his master Sultan Ismail ibn Sharif also decried the English regicide, and this sentiment would have played well with Restoration-era audiences. |

| 19 | This drop may also have been to do with the increased level of peaceful interaction—(Ghobrial 2013, p. 27) has noted that ‘news about the Ottomans peaked at specific moments of military confrontation’ like the battle of Lepanto (1571), the conquest of Candia (1669) and the siege of Vienna (1683), and declined in periods of relative peace. |

| 20 | (Ghobrial 2013, pp. 122–58) has documented in great detail how stories of the deposition of the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed IV made their way from local events through English diplomats to English newspapers and English readers. |

| 21 | (Matar 2005, pp. 153, 158) does recognise isolated Restoration publications as serving a propagandistic purpose in support of defending Tangier against the Moroccans (one government and several private), as well as one printed account heralding a naval victory against Tripoli, but in neither case do the writers present a positive view of the Maghrebi states or their relationships with Britain. |

| 22 | (Parker 2004, p. 101) asks this question in relation to the official, stand-alone publication of Articles of Peace in the early Restoration period, but does not venture to answer it. |

| 23 | (Ghobrial 2013, p. 37) has noted that Sir William Trumbull collected copies of the London Gazette (as well as French equivalents and numerous printed books and pamphlets) before, during and after his tenure as British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, but does not comment on the content or effect of this material. |

| 24 | Pepys 1660–1669, 19 January 1662 (available at: https://www.pepysdiary.com/diary/1662/01/19/), 22 November 1662 (available at https://www.pepysdiary.com/diary/1662/11/22/), 28 November 1664 (https://www.pepysdiary.com/diary/1664/11/28/). |

| 25 | (Birchwood 2007) ends where it does for similar reasons. See also (Birchwood 2005, p. 74). |

| Period | Articles | Average Per Year | % of Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1622–1660 | 106 | 2.7 | 3.13% |

| 1661–1680 | 1010 | 50.5 | 29.84% |

| 1681–1682 | 434 | 217.0 | 12.82% |

| 1683–1703 | 1240 | 59.0 | 36.63% |

| 1704–1714 | 595 | 54.1 | 17.58% |

| Total | 3385 | 36.4 | 100.00% |

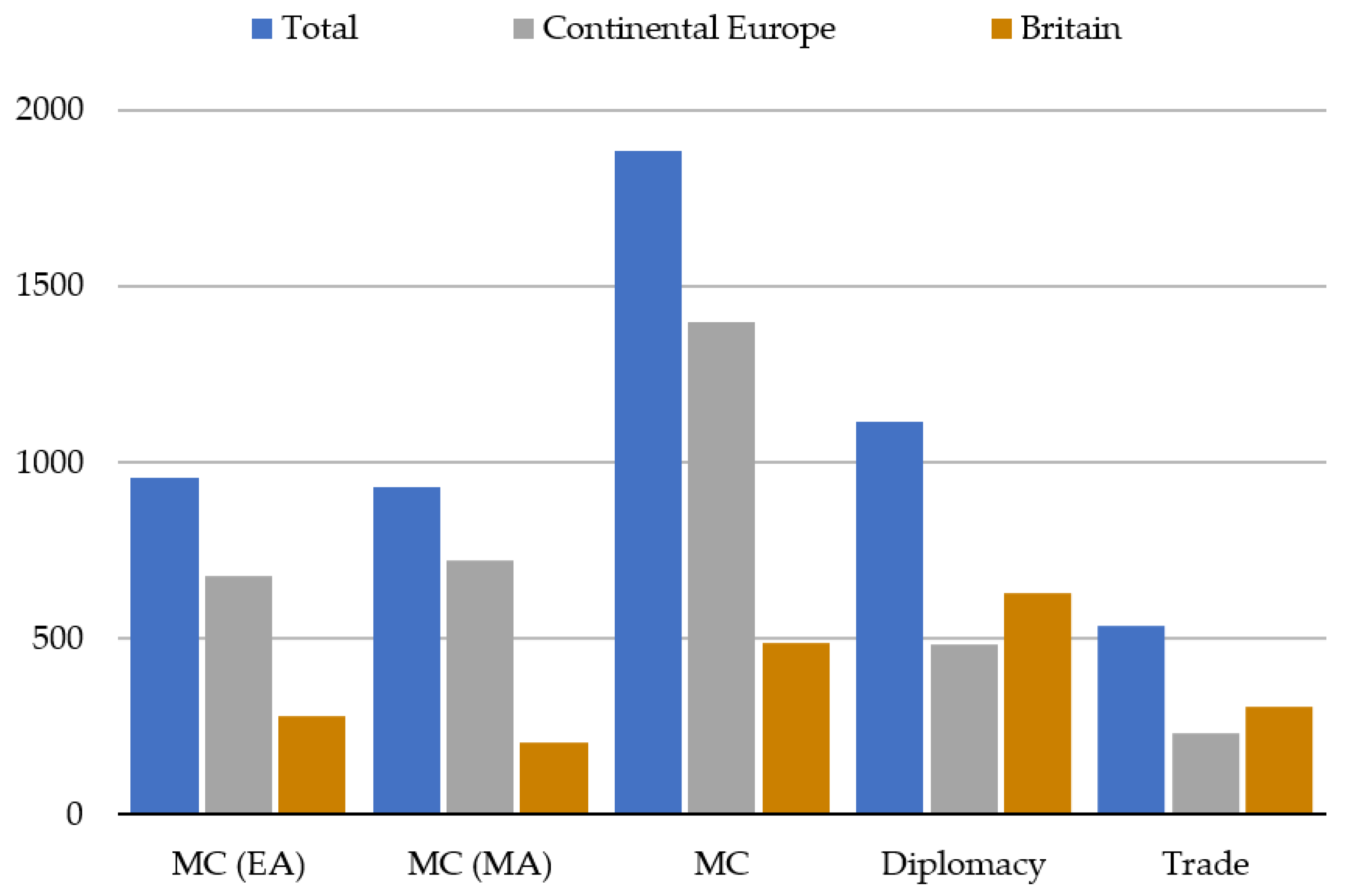

| Topic Category | Total References | Continental Europe | Britain | Britain % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maritime Combat (European attack) | 956 | 676 | 280 | 29.29% |

| Maritime Combat (Maghrebi attack) | 929 | 723 | 206 | 22.17% |

| Maritime Combat | 1885 | 1399 | 486 | 25.78% |

| Diplomacy | 1113 | 482 | 631 | 56.69% |

| Peaceful Trade | 537 | 230 | 307 | 57.17% |

| Term | 1622–1660 | 1661–1680 | 1681–1682 | 1683–1703 | 1704–1714 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pirate | 41 | 88 | 23 | 40 | 21 | 213 |

| Rover | 4 | 1 | 6 | 93 | 35 | 139 |

| Illegitimate | 44 | 89 | 29 | 130 | 53 | 345 |

| Corsair | 1 | 224 | 18 | 102 | 57 | 399 |

| Privateer | 0 | 17 | 2 | 16 | 33 | 68 |

| Licensed | 1 | 229 | 20 | 116 | 83 | 449 |

| Man of War | 3 | 173 | 29 | 58 | 11 | 270 |

| Admiral | 1 | 19 | 3 | 20 | 10 | 52 |

| Naval | 4 | 189 | 32 | 74 | 21 | 322 |

| Ship etc. | 20 | 71 | 7 | 36 | 18 | 152 |

| Term | 1622–1660 | 1661–1680 | 1681–1682 | 1683–1703 | 1704–1714 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pirate | 38.68% | 8.71% | 5.30% | 3.23% | 3.53% | 6.29% |

| Rover | 3.77% | 0.10% | 1.38% | 7.50% | 5.88% | 4.11% |

| Illegitimate | 41.51% | 8.81% | 6.68% | 10.48% | 8.91% | 10.19% |

| Corsair | 0.94% | 22.18% | 4.15% | 8.23% | 9.58% | 11.79% |

| Privateer | 0.00% | 1.68% | 0.46% | 1.29% | 5.55% | 2.01% |

| Licensed | 0.94% | 22.67% | 4.61% | 9.35% | 13.95% | 13.26% |

| Man of War | 2.83% | 17.13% | 6.68% | 4.68% | 1.85% | 7.98% |

| Admiral | 0.94% | 1.88% | 0.69% | 1.61% | 1.68% | 1.54% |

| Naval | 3.77% | 18.71% | 7.37% | 5.97% | 3.53% | 9.51% |

| Ship etc. | 18.87% | 7.03% | 1.61% | 2.90% | 3.03% | 4.49% |

| Corpus articles | 106 | 1010 | 434 | 1240 | 595 | 3385 |

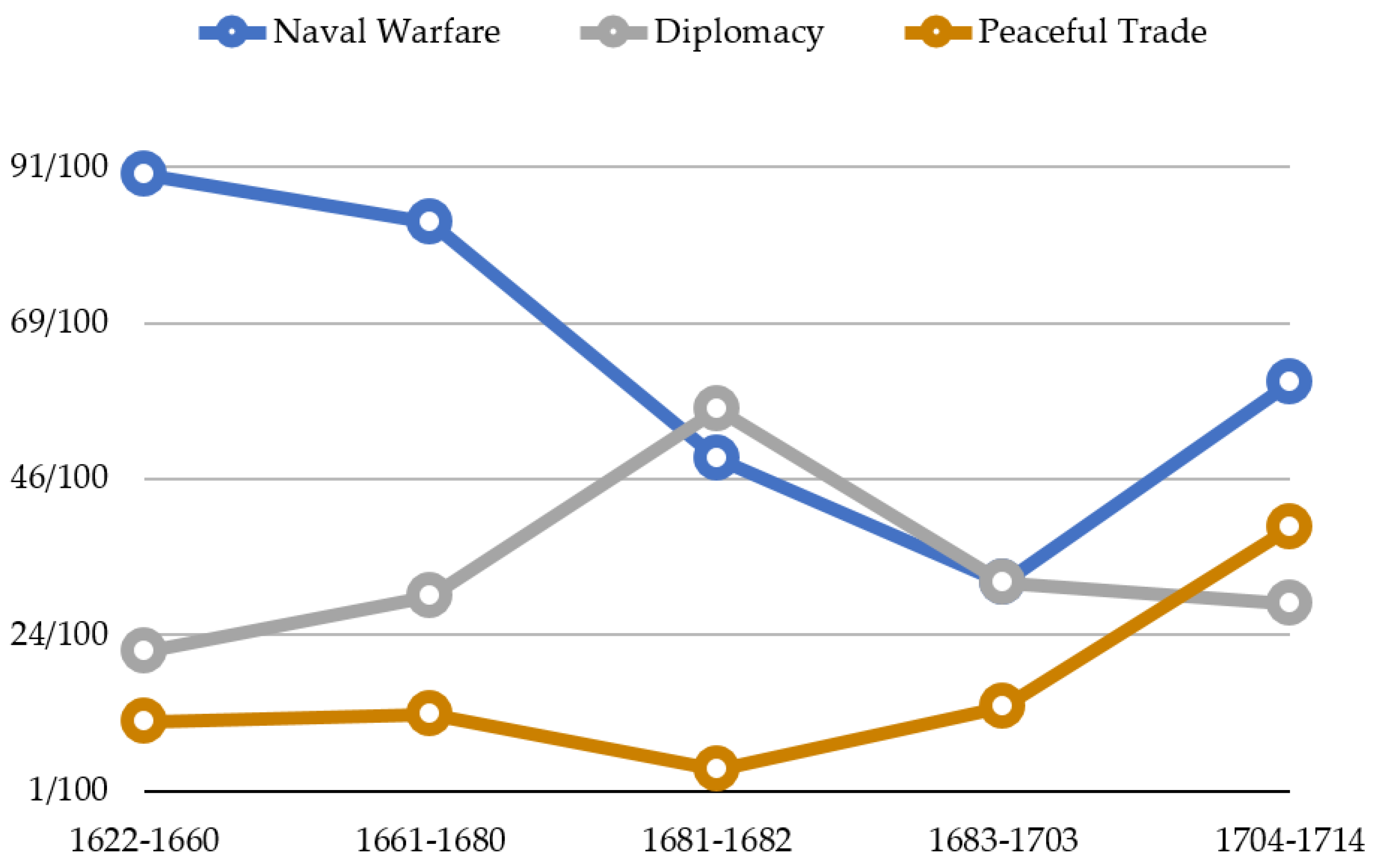

| Topic Category | Time Period | References | % of Category | References per 100 Articles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maritime Combat (European against Maghrebi) | 1622–1660 | 41 | 4.29% | 39/100 |

| 1661–1680 | 409 | 42.78% | 40/100 | |

| 1681–1682 | 134 | 14.02% | 31/100 | |

| 1683–1703 | 120 | 12.55% | 10/100 | |

| 1704–1714 | 252 | 26.36% | 42/100 | |

| Total | 956 | 100.00% | 28/100 | |

| Maritime Combat (Maghrebi against European) | 1622–1660 | 54 | 5.81% | 51/100 |

| 1661–1680 | 426 | 45.86% | 42/100 | |

| 1681–1682 | 79 | 8.50% | 18/100 | |

| 1683–1703 | 267 | 28.74% | 22/100 | |

| 1704–1714 | 103 | 11.09% | 17/100 | |

| Total | 929 | 100.00% | 27/100 | |

| Maritime Combat (Total) | 1622–1660 | 95 | 5.04% | 90/100 |

| 1661–1680 | 835 | 44.30% | 83/100 | |

| 1681–1682 | 213 | 11.30% | 49/100 | |

| 1683–1703 | 387 | 20.53% | 31/100 | |

| 1704–1714 | 355 | 18.83% | 60/100 | |

| Total | 1885 | 100.00% | 56/100 | |

| Diplomacy (Maghrebi with European) | 1622–1660 | 22 | 1.98% | 21/100 |

| 1661–1680 | 297 | 26.68% | 29/100 | |

| 1681–1682 | 242 | 21.74% | 56/100 | |

| 1683–1703 | 388 | 34.86% | 31/100 | |

| 1704–1714 | 164 | 14.73% | 28/100 | |

| Total | 1113 | 100.00% | 33/100 | |

| Peaceful Trade (Maghrebi with European) | 1622–1660 | 12 | 2.23% | 11/100 |

| 1661–1680 | 118 | 21.97% | 12/100 | |

| 1681–1682 | 16 | 2.98% | 4/100 | |

| 1683–1703 | 161 | 29.98% | 13/100 | |

| 1704–1714 | 230 | 42.83% | 39/100 | |

| Total | 537 | 100.00% | 16/100 |

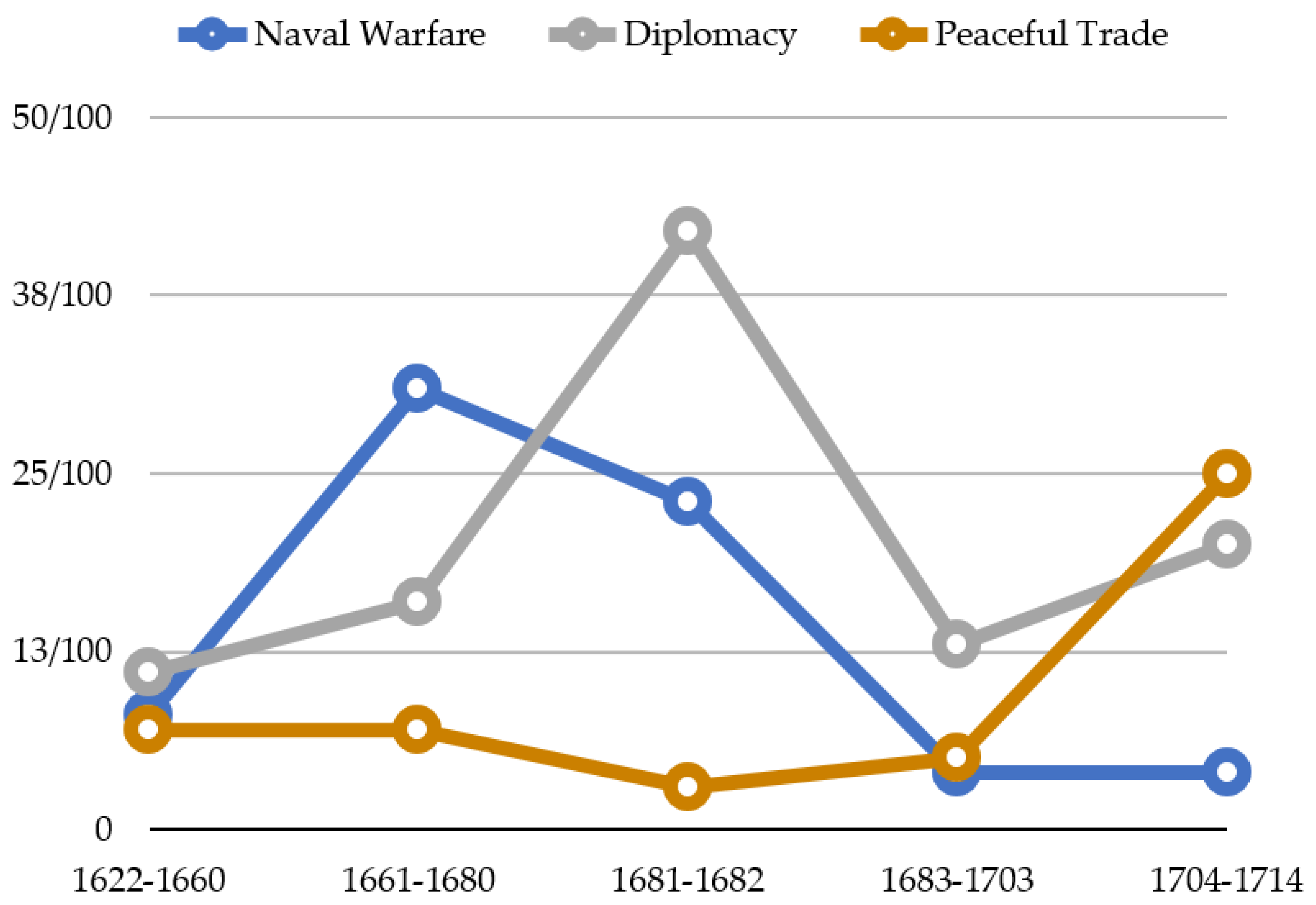

| Topic Category | Time Period | References | % of British across All Periods | References per 100 Articles | % of all European in Each Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maritime Combat (British against Maghrebi) | 1622–1660 | 2 | 0.71% | 2/100 | 4.88% |

| 1661–1680 | 184 | 65.71% | 18/100 | 44.99% | |

| 1681–1682 | 65 | 23.21% | 15/100 | 48.51% | |

| 1683–1703 | 22 | 7.86% | 2/100 | 18.33% | |

| 1704–1714 | 7 | 2.50% | 1/100 | 2.78% | |

| Total | 280 | 100.00% | 8/100 | 29.29% | |

| Maritime Combat (Maghrebi against British) | 1622–1660 | 6 | 2.91% | 6/100 | 11.11% |

| 1661–1680 | 127 | 61.65% | 13/100 | 29.81% | |

| 1681–1682 | 33 | 16.02% | 8/100 | 41.77% | |

| 1683–1703 | 22 | 10.68% | 2/100 | 8.24% | |

| 1704–1714 | 18 | 8.74% | 3/100 | 17.48% | |

| Total | 206 | 100.00% | 6/100 | 22.17% | |

| Maritime Combat (Total) | 1622–1660 | 8 | 1.65% | 8/100 | 8.42% |

| 1661–1680 | 311 | 63.99% | 31/100 | 37.25% | |

| 1681–1682 | 98 | 20.16% | 23/100 | 46.01% | |

| 1683–1703 | 44 | 9.05% | 4/100 | 11.37% | |

| 1704–1714 | 25 | 5.14% | 4/100 | 7.04% | |

| Total | 486 | 100.00% | 14/100 | 25.78% | |

| Diplomacy (Maghrebi with British) | 1622–1660 | 12 | 1.90% | 11/100 | 54.55% |

| 1661–1680 | 162 | 25.67% | 16/100 | 54.55% | |

| 1681–1682 | 181 | 28.68% | 42/100 | 74.79% | |

| 1683–1703 | 159 | 25.20% | 13/100 | 40.98% | |

| 1704–1714 | 117 | 18.54% | 20/100 | 71.34% | |

| Total | 631 | 100.00% | 19/100 | 56.69% | |

| Peaceful Trade (Maghrebi with British) | 1622–1660 | 7 | 2.28% | 7/100 | 58.33% |

| 1661–1680 | 75 | 24.43% | 7/100 | 63.56% | |

| 1681–1682 | 12 | 3.91% | 3/100 | 75.00% | |

| 1683–1703 | 64 | 20.85% | 5/100 | 39.75% | |

| 1704–1714 | 149 | 48.53% | 25/100 | 64.78% | |

| Total | 307 | 100.00% | 9/100 | 57.17% |

| Publication | Articles | % of Total Articles |

|---|---|---|

| Oxford/London Gazette (1665–1714+) | 1445 | 42.69% |

| Post Boy (1695–1714+) | 282 | 8.33% |

| Daily Courant (1702–1714+) | 260 | 7.68% |

| Flying Post (1695–1714+) | 229 | 6.77% |

| Post Man (1695–1714+) | 196 | 5.79% |

| London Post (1699–1705) | 98 | 2.90% |

| Domestic Intelligence (1679–1681) | 74 | 2.19% |

| True Protestant Mercury (1680–1682) | 70 | 2.07% |

| Loyal Protestant and True Domestick Intelligence (1681–1683) | 60 | 1.77% |

| British Mercury (1710–1714+) | 54 | 1.60% |

| English Post (1700–1709) | 47 | 1.39% |

| Evening Post (1710–1714+) | 38 | 1.12% |

| Total: Top 12 (each over 1% of total) | 2853 | 84.28% |

| Total: Remaining 95 (each less than 1% of total) | 532 | 15.72% |

| Total: Government Papers | 1574 | 46.50% |

| Total: Non-Government Papers | 1811 | 53.50% |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cutter, N. Peace with Pirates? Maghrebi Maritime Combat, Diplomacy, and Trade in English Periodical News, 1622–1714. Humanities 2019, 8, 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8040179

Cutter N. Peace with Pirates? Maghrebi Maritime Combat, Diplomacy, and Trade in English Periodical News, 1622–1714. Humanities. 2019; 8(4):179. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8040179

Chicago/Turabian StyleCutter, Nat. 2019. "Peace with Pirates? Maghrebi Maritime Combat, Diplomacy, and Trade in English Periodical News, 1622–1714" Humanities 8, no. 4: 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8040179

APA StyleCutter, N. (2019). Peace with Pirates? Maghrebi Maritime Combat, Diplomacy, and Trade in English Periodical News, 1622–1714. Humanities, 8(4), 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8040179