Abstract

This article examines a mass produced postcard image as a picture of conflict. It considers the postcard as a Benjaminian ‘prismatic fringe’ through which an archive can be viewed, wherein documents of the British trade in Chilean nitrate are juxtaposed with those of General Pinochet’s 1973 military coup. The archive itself is explored as a site of loss and its postcard, an unvarying idealisation, as a particularly problematic but powerful image that renders conflict out of sight.

1. Introduction

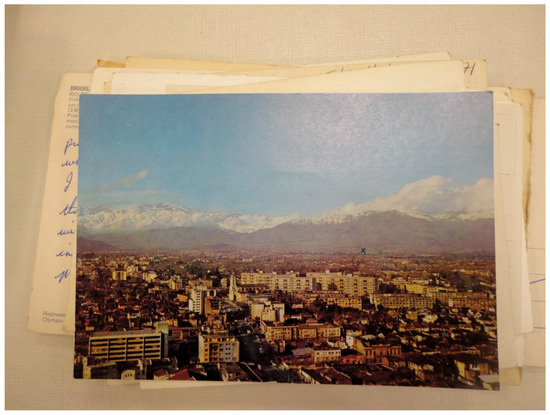

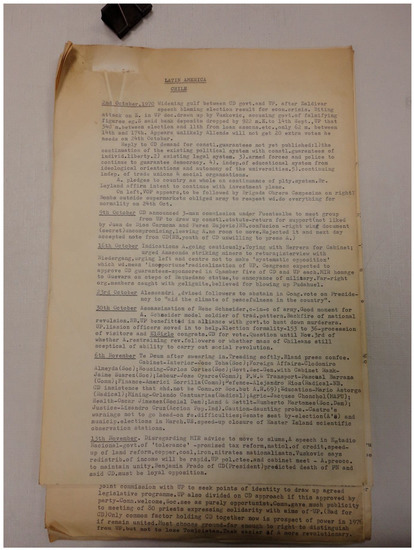

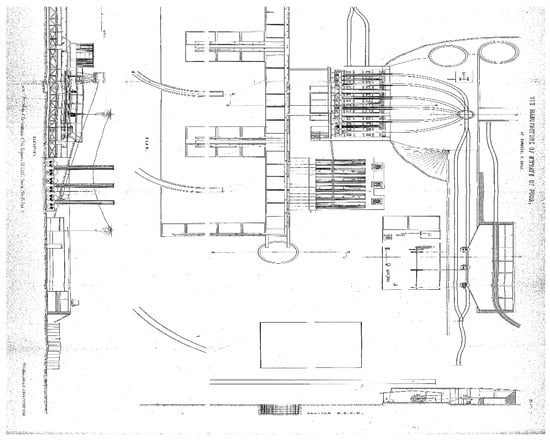

Not all pictures of conflict carry the visual shock of photojournalism in either its past or present forms, not all have the sombre grey tones of newspaper photographic reproductions that depict the awful wreckage of exploded bombs, and not all consist of the bright pixels sent across internet sites that clinically translate the horror of bodies ripped apart. Some pictures of conflict are everyday artefacts. For all their banality (Billig 1995), they can be more powerful than the shocking exposures of war because they are less disruptive. Insidious instead, they quietly install the inequalities of conflict into everyday life (Edensor 2002), while conflict itself, and the terrible acts of violence that accompanies it, are often obscured. A postcard examined in this article, is one such everyday artefact, a mass produced image intended for domestic exchange. It is a cityscape titled, Santiago, Luz de Atardecer, con Vista de la Cordillera de Los Andes (Santiago in the Evening Light with a view of the Andes Mountains), sent in the early years of General Augusto Pincohet’s military dictatorship from a historian of nineteenth century Chilean economic politics to his London family (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Santiago, Luz de Atardecer, con Vista de la Cordillera de Los Andes (Santiago in the Evening Light with a View of the Andes Mountains), The Harold Blakemore Latin American Archive, Special Collections, J. B. Priestley Library, University of Bradford.

‘The mass medium of the picture postcard’, wrote Bernhard Siegert, ‘had taken the place of memory and experience’ (Siegert 1997, p. 162). The image, Santiago, Luz de Atardecer, although the postcard is not only an image, could be considered part of what Pierre Nora identified as the ‘collapse of memory’ that has occurred through ‘mass culture on a global scale’ (Nora 1989, p. 7).1 Reproductions contribute to the undoing of real life that was once lived with memory, which now relies upon historical records. Once a mass produced picture starts to circulate, once it is seen, sold, and sent, it becomes difficult to recognise what happened outside the image, to see what was, or is still, out of sight.

This picture postcard of conflict faces the problem of many records of the everyday, one that is not shared by the war imagery that has entered a political domain, even if only momentarily. As artefacts of domestic exchange, the preservation of everyday records is most arbitrary and dependent upon the contingencies of archiving other histories considered more significant than its own quotidian condition. Santiago, Luz de Atardecer, is bound to records of Chilean and British economic history, boxed up between notes on City of London banks and Tarapacá nitrate mines in the Harold Blakemore Latin American Archive housed within the J. B. Priestley Library at the University of Bradford. Mass produced domestic things that end up in archives are often accessioned without detailed annotation; they are simply gathered up along with documents of already agreed historical significance. Although overlooked, they are tangible evidence of the ties between the routines of domestic exchange and the operations of the political domain: the formations colonial power and its legacies, the workings of industrial and financial capitalism that has extended competition for resources across the world, fuelling conflict. Postcards, in particular, draw together the domestic and the political; they cross the separations of capitalism and conflict. Postcard images are sent back home, from periphery to centre, satellite to metropolis (Gunder Frank [1969] 1971): a temporal trace of a spatial relationship. Picture postcards may not fire the shocking charge of photojournalism, but can carry a weight of historical connections. Their load is not obvious at first sight. The bright commercial colours of a mass produced image of Santiago seem decoratively superfluous to the business of the Harold Blakemore Latin American Archive, on the ‘fringes’ of its documentation of academic investigations of the British-Chilean economic history punctuated by conflict: the 1879–1884 Pacific War, the 1881 Civil War, the 1914–1918 World War, and the 1973 Pinochet coup. However, Santiago, Luz de Atardecer, an image of light over a city, refracts it across the archive and the historical documents contained within.

Visual technologies and political strategy collide. Military bureaucracy dedicated to ensuring that opposition and its oppression were out of sight characterized the Latin American dictatorships of the 1960s and 1970s. Disappearances, the removal of the person and the trace of their body through imprisonment, torture, death, and disposal of their remains, were the practice of political repression. The National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture or Valech Commission found that between 1973 and 1990, that is the Pinochet years, 3216 people were disappeared and 38,254 tortured (National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture 2005).2 Families of the desaparecidos have appealed to both memory and history, attested to both a real life lived and evidence of that life, to reclaim their relative’s existence. Material traces are forms of resistance to disappearance. To roughly summarise Nora (1989, p. 12), loss of memory leads us to archives. But historical loss may be all there is to find: material traces that do not repair loss but only recognise it, or worse, reinstate it. My search in an archive for traces of the extraction and export of Chilean nitrate found them entangled in a history of loss.

My attempt to interpret this postcard as a picture of conflict is written as a series of encounters with the archive in which it is held, with the writings of historian Harold Blakemore, who sent it, and with the history of the nineteenth century British trade in Chilean nitrate about which he wrote. I have sought not to separate the postcard and its historical moment, the repression of the military dictatorship in twentieth century Chile. Nor have I sought to remove it from its present location in an archive, where the postcard is part of a longer past. It is a circuitous way of making an argument about the historical materiality of images of war: traces of past exploitation are present in contemporary conflicts and can be found in the most everyday artefacts of exchange.

2. Archive

Despite my initial emailed request to see the whole Harold Blackmore Latin American Archive, when I visited the University of Bradford’s J. B. Priestley Library, the archivists brought only the ‘Notes from British business archives on historic Anglo-Chilean business links and the nitrates trade’ (Blakemore 1993) (Figure 2). This box, I was told, is the one ‘most people want to see.’ It contained the research for Harold Blakemore’s defining work, British Nitrates and Chilean Politics, 1886–1896: Balmaceda and North, published in 1974. It contains a long series of handwritten notes copied from records of The Bank of Tarapacá and London, and correspondence between London merchant house Antony Gibbs and Sons, and their Chilean representatives, William Gibbs Company. It is a simultaneous record of two moments in time: that of the history of British interests in nitrate mining in the late nineteenth century, and of a British academic who studied this history in the late twentieth. As the certainty of the first two words of its title indicates, British Nitrates, the book, is not a debate about the ownership of an element of the Earth, nitrogen, which is locked in the salty rocks of the Atacama Desert (Blakemore 1974). It is an examination of the ways that the political transactions over the export of nitrate to the European chemical market affected Chilean national history and were, inevitably, caught up in the moment of its writing. The Unidad Popular government led by Dr Salvadore Allende, elected on 4 September 1970, carried out an extensive nationalisation programme of natural resources that included the remaining nitrate industry, copper mines, and farming land, until its socialist project was overthrown by the military coup led by General Augusto Pinochet, aided by the United States’ Central intelligence Agency, on 11 September 1973.

Figure 2.

Notes from British business archives on historic Anglo-Chilean business links and the nitrates trade, The Harold Blakemore Latin American Archive, Special Collections, J. B. Priestley Library, University of Bradford.

Harold Blakemore, ‘standard-bearer of Latin American studies’, was an important figure in its institutionalisation within the British University system (Fox 1991, p. 333). When the Society of Latin American Studies formed in 1964, he was a founder member. A year later, when the Institute of Latin American Studies was established at the University of London, he was its first secretary. He played administrative and academic roles in the organisation of Latin American Studies for much of his working life, as, for example, being the editor of the Journal of Latin American Studies, from 1969 to 1987. He was Emeritus Reader in Latin American History at the University of London when he died. His archive, donated to the University of Bradford two years after his death in 1993, comprises his ‘books and papers,’ the materials of an academic’s office.

I tried to explain to the J. B. Priestley’ Library’s archivists that the entirety of the Harold Blakemore Latin American Archive was of relevance to my work for the project Traces of Nitrate (www.tracesofnitrate.org). A short summary of my pleas should suffice: of course, I could not possibly read in a week all of every paper that comprises a life’s work, but I needed to know what was there, to find the material forms through which nitrate might appear here in an academic’s office, to examine the traces of a once highly prized but forgotten trade, in a substance of historical significance that is now all but invisible. A trolley of boxes of files was wheeled between my reader’s desk and the archivists’ station (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Trolley of boxes, The Harold Blakemore Latin American Archive, Special Collections, J. B. Priestley Library, University of Bradford.

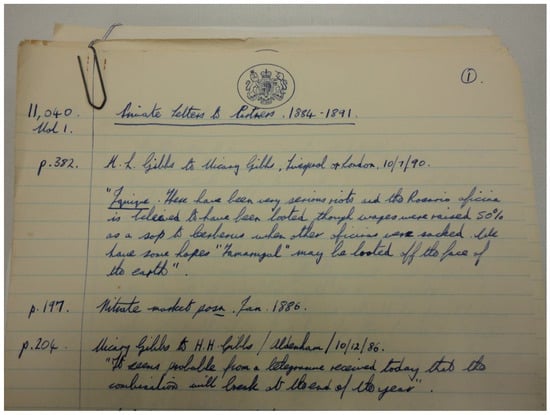

The Harold Blackmore Latin American Archive contains stacks of handwritten notes, financial transactions labouriously translated at least one decade before the widespread use of rapid analogue reproduction, the now all too familiar feeding documents through a photocopier, and another two before the installment of scanners that would digitise the archive. In ink pen on lined paper, Blakemore transcribed, for example, thousands and thousands of words from the Antony Gibbs Papers then held in Guildhall Library. For example, in his first page of notes from ‘Private Letters to Partners 1884 to 1891’, he copied the communication from ‘Vicary Gibbs to H. H. Gibbs’ of ‘10/12/86’, wherein the former warned the latter that “It seemed probable from a telegramme received today that the combination will break at the end of the year.” Another hand copied extract is to ‘Vicary Gibbs’ from ‘M. L. Gibbs’ on ‘10/7/90’:

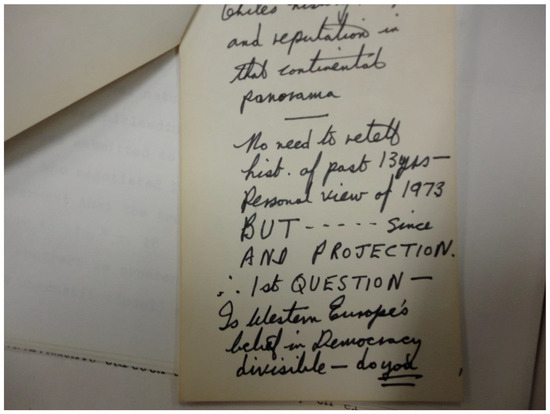

“Iquique: there have been very serious riots and the Rosario oficina is believed to have been looted though wages were raised 50% as a sop to workers when other oficinas were sacked. We have some hopes that “Tamarugul” may be looted off the face of the earth”.(Blakemore 1993) (Figure 4) Figure 4. ‘Private Letters to Partners 1884 to 1891,’ hand-written notes from Antony Gibbs Papers, The Harold Blakemore Latin American Archive, Special Collections, J. B. Priestley Library, University of Bradford.

Figure 4. ‘Private Letters to Partners 1884 to 1891,’ hand-written notes from Antony Gibbs Papers, The Harold Blakemore Latin American Archive, Special Collections, J. B. Priestley Library, University of Bradford.

This account, which reveals the calculating nature of a nitrate capitalist’s labour relations, as well as disregard for nitrate lands, was boxed up above folders of newspaper clippings from the Chilean press about Allende’s election and the early days of the government of the Unidad Popular. Another box contained the chronology of these events. An entry under ‘6th November’ reads, ‘U.S speed up closure of Easter Island scientific observation stations.’ Another from ‘13th November’: ‘A speech in Estadio Nacional—govt of “tolerance” promised tax reform, natiol of credit, speed up of land reform, copper, coal, iron, nitrates nationalisatn.’ That of ‘19th November’ recorded, ‘Castro visit—praised Chilean road to Socialism and urged left Unity…Portents suggest US non-coop. with regime’ (Blakemore 1993) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Chronology: ‘Latin America, Chile’, The Harold Blakemore Latin American Archive, Special Collections, J. B. Priestley Library, University of Bradford.

This typed chronology, as detailed as a diary, has the note form and present tense of a contemporaneous record, but it is one on which the dust has settled. Dust, in Carolyn Steedman’s meditation on the archive, is formed by the disintegration of historical materials, parchments, and papers; it creates a physiological transfer between the people of the past and those who seek to study them (Steedman 2002). I would suggest that dust is also the materialisation of neglect; it is, like all things, a gathering, that is physical and symbolic. A gathering of dust only takes place when other things are left alone. Dust is a timekeeper; it accumulates with the passage of uninterrupted days that run into years. The even undisturbed layer of dust on the rounded impressions of a typewriter that summarised plans for the Chilean socialist economy and its opposition, demonstrates disregard. But these documents, not significant enough to be consulted because they lay outside the main business of the archive, are the very things that reveal its condition. Texts of the extraction of nitrate by late nineteenth century British capitalists and that of the nationalisation of resources by late twentieth Chilean socialists are a ‘constellation,’ in Walter Benjamin’s words, of historical events (Benjamin 1992a).

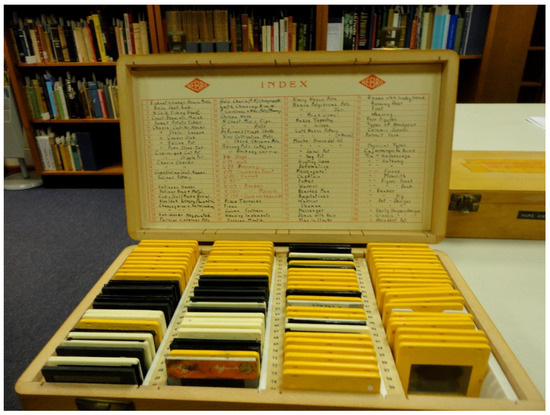

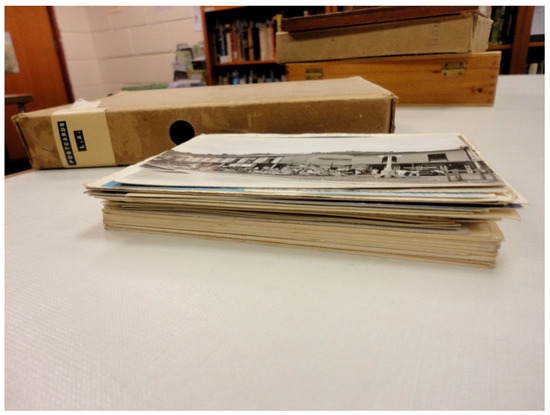

There is more: 1970s tourist guidebooks, 1980s lecture notes on responsibility for the restoration of democracy in Chile, slide boxes filled with colour transparencies of Latin American archaeology, pressed plants, and postcards from friends and to family (Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8). It is these piles of picture postcards that might appear most out of place in the archives of a university library: they are neither academic texts nor the words of a well-known author, such as J.B. Priestley, whose life and narratives were connected to the English northern industrial town in which the archive is located (Figure 8). The picture postcards are on the margins of the archive and when I arrived there, they were left on the shelf by the archivists. They are from the places Benjamin described as ‘fringe areas’; they are the ‘prismatic fringes of a library’, that is, the things through which it is possible to view the whole collection of documents differently: a distributed focus and a fractured view that alters perception (Benjamin 1992a).

Figure 6.

Lecture notes, The Harold Blakemore Latin American Archive, Special Collections, J. B. Priestley Library, University of Bradford.

Figure 7.

Colour transparencies, The Harold Blakemore Latin American Archive, Special Collections, J. B. Priestley Library, University of Bradford.

Figure 8.

Postcards, The Harold Blakemore Latin American Archive, Special Collections, J. B. Priestley Library, University of Bradford.

3. Nitrate

The pivotal event of Harold Blakemore’s British Nitrates and Chilean Politics, 1886–1896, is the 1891 civil war, a confrontation between Congress and Presidency, between a Chilean elite whose financial interests lay with European nitrate traders and José Balmeceda. Blakemore considered the role that nitrate revenues and nitrate monopolies played in Chilean national history, although his focus was not upon the larger structures or long-term development of the Chilean state. He wrote of the intricacies of financial and personal relationships within the nitrate trade that he discovered in the lines upon lines of letters sent between Chile and Britain, between partners and managers of nitrate companies, which now lie stacked in boxes in his University of Bradford archive. These were competitive relationships. The prestige and profit of British capitalists were staked upon securing the richest nitrate grounds in the Atacama Desert, mining and refining a chemical from its caliche rock that was then exported as a fertiliser or an explosive, and upon ownership of the railways that carried bags of refined nitrate from the oficinas to the ports on the Pacific coast, Iquique and Pisagua, ready to sail on to Liverpool or London. Those who constructed and controlled these lines of transport could extort high carriage charges, squeezing further profits from the nitrate trade that reduced those of nitrate mining itself. Furthermore, the construction of the railways was a concession that required political approval: thus, railways brokered a relationship between the competing interests of British capital, as well as between British capital and the Chilean state.

The ten-year period of Blakemore’s book, 1886 to 1896, covers the height of nitrate trade, but it has a longer industrial history. The Atacama Desert was intensively mined for nitrate from the 1879–1884 War of the Pacific to the 1914–1918 First World War. The former was a land grab for nitrate, recognised in its German name Satlpeterkrieg. Nitrate was a highly sought raw material that naturally occurred in its sodium form only in the dry land between the Andes and the Pacific. There are records of its processing in Peru through the Spanish colonial period, but the transformation of natural nitrate into a commodity of life and death was attendant upon the capitalisation and industrialisation of the Atacama desert, led by traders from London and Liverpool. The ‘merchant houses were the basic commercial units of British expansion’ writes Michael Monteón (Monteón 1975, p. 118).

In a paper presented at the Institute of Civil Engineers in London in 1885, entitled “Machinery for the Manufacture of Nitrate of Soda at the Ramirez Factory, Northern Chili”, Robert Harvey, a Cornish mining engineer and partner in John Thomas North’s Liverpool Nitrate and Railway Company that owned Ramirez oficina, boasted that its machinery (six steel boilers, twelve boiling-tanks, locomotives and rolling-stock, engines, pumps, machine-tools), for Shanks process of refining soda, adapted for nitrate production, were made at a number of workshops in St. Helens and Leeds (Harvey 1884–1885) (Figure 9). Just one part of the plant, one group of machines, the crushers, were made in the Chilean port of Iquique, by an English firm owned by Harvey’s partner, John Thomas North. Once all the machinery was installed, and capital fixed, mining nitrate was a matter of hard manual work. Labouring men, Chilean, Bolivian, and Peruvian, were brought and bound through an enganche system to live in the nitrate oficinas (Monteón 1979). Thus the nineteenth century nitrate industry was driven by British capital that colonised the Atacama, an inhospitable place, an almost waterless environment (Figure 10).

Figure 9.

Manufacture of Nitrate of Soda at Ramirez, N. Chili. Proceedings of the Institute of Civil Engineers. Paper No. 2086, pp. 337–38.

Figure 10.

‘Emptying the Bateas’ Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899, Album 12, Fondo Fotográfico Fundación Universidad de Navarra, Pamplona.

Exports were taxed. The Chilean government gained revenue derived from taxing nitrate. A high production of nitrate delivering high volumes of export was in the Chilean national interest: more nitrate accrued more revenue. But high exports lowered prices in world markets. It was in the interest of British and other European companies to restrict production, reduce exports, and raise prices; successive ‘combinations’ of competing companies, nitrate mining monopolies, were established to regulate production. One, led by ‘English companies,’ established a Permanent Nitrate Committee based in London in March 1891 (Brown 1963, p. 236). The much-quoted warning about the future of Tarapacá, ‘we ought not to allow this rich and extensive region to be converted simply into a foreign factory’, summarised Chile’s President José Balmaceda’s opposition to British monpolistas (Blakemore 1974, p. 150). Market and nation were opposed and, in 1891, the market divided the nation and set the Congress whose political elites were entangled with European nitrate interests against a President seeking to moderate and regulate those same interests. Congress revolted. From January 1891, Congressional navy and Presidential army fought in the nitrate ports and provinces until the Congressionalists seized Tarapacá. In the eight months of civil war, 10,000 people were killed, including José Balmadeca, who shot himself on 18 September 1891 on the day his elected Presidency ended.

Blakemore would consider my summary ‘superficially attractive’ relating to a ‘misreading’ of Balmaceda, who, he argues, was more equivocal towards ‘foreign interests.’ Moreover, nitrates played only a ‘minor role’ in the Congressional opposition; the ‘domestic political situation’ was more important (Blakemore 1974, p. 193). However, Blakemore recognised that Balmaceda has become an historical allegory, a lost Chilean history personified and about to be redeemed. He wrote:

In this process of using Chile’s past not only to explain the present but also to shape the future, Balmeceda occupies a crucial place, and his personal tragedy assumes the dimensions of a national catastrophe. To marxists, he appears as a president with clear ideas about state intervention in the economy and as a economic nationalist who was determined to recover the national patrimony which had been alienated under the ruling philosophy of laissez-faire: had he succeeded, it is suggested, he might well have changed the course of Chilean history, setting the country on the path of democratic politics, social justice and economic growth based on national ownership of basic resources. It is an image that has proved useful in recent Chilean history: in the presidential election of 1970 and subsequently, Balmeceda was used as an exemplar for the left-wing coalition of parties under Dr Salvador Allende whose programme included massive state intervention in the economy and the expropriation of foreign assets.(Blakemore 1974, p. 245)

His tragedy ‘assumes’, he ‘appears’, and it is ‘suggested’: Blakemore’s scholarly tone does not quite mask his disbelief in the reality of the analogy of past loss. Yet, loss pervades all the documents kept by Blakemore, even if it is subdued in his published writings. The ‘history of the archive is a history of loss,’ observed Burton (2001, p. 66) and it cannot be otherwise: all documents, the transcribed late nineteenth century letters between nitrate capitalists and typed chronology of the early days of Unidad Popular government, the colour transparencies of Latin American archaeology, and the picture postcards, are records of a moment of time that has passed.

4. Postcard

Santiago, Luz de Atardecer, con Vista de la Cordillera de Los Andes has the bright, light blue skies of the typical tourist postcard; there is an azure background to so many sandy beaches, pretty villages, or sophisticated cities that are sent as souvenirs (Figure 1). Luz de Atardecer translates as sunset. Postcards of sunsets are as common as azure skies; the sinking sun shedding glorious light on a landscape about to fade from view is a photographic favourite (Pollen 2016; Stallabrass 1996). It appears both unique and universal; a specific moment in the turning of the Earth’s orbit is cleverly captured and reproduced to offer a shared sense of time: the end of the day.

It would be difficult to find a more unexceptional postcard than this: a view of a city in good light, summarised in the standard form exchanged across the globe, an oblong of four by six inches. It is a well-organised view: from the elevated position from which the colour photograph was taken, the built space of the city spreads out over almost exactly half the size of the postcard to meet the mountains. Clouds and sky cover the other half until they reach the sharp line of the top edge of the card. The balance between ground and sky, foreground and background, built and natural, is reassuringly conventional. Each part of the landscape is in its expected place.

Such views are everywhere; they are commonplace. Firstly, this is because postcards of cities are abundant and, secondly, because cities are visualised through the postcard form. These two statements are not quite the same. Of the different genres of postcards, the reproduction of views constitutes one of its largest categories, and city views are abundant within that category. ‘One of the main postcard genres, view cards feature primarily cities and urban environments,’ note Prochaska and Mendelson (2010, p. xii). Cityscapes are a typical postcard and there are plenty of them. Their ubiquity has affected the way in which the city is seen. Nancy Stieber states that ‘by 1900 the postcard had become the chief mode for mass production of city images’ (Stieber 2010, p. 24). Their number is significant, as is their form, which shapes the way in which the city is seen. The postcard city standard dominates in the circuit of visuality of urban life, guiding the expectations and experiences of both urban dwellers and urban visitors.

The image of the modern architecture of Santiago surrounded by the snow-topped Andes reveals a historical development in a geographical location; it has to do this to perform as a postcard: a small reproducible print of time and place, the most common souvenir. Mass produced for mass communication, it has the reliable character of all commodities; it is a predictable form, a summary of Santiago, a stock image, that will suffice as a souvenir: cheaply bought, quickly sent, rapidly received. Its reliability as a representation, along with its azure skies, is an idealisation: an unvarying view.

The city centre and the city limits, the buildings, streets and circulating traffic, and the urban geography condensed into a small tangible rectangle is, as Prochaska and Mendelson describe, ‘a means to identify and possess the totality of the city’ (Prochaska and Mendelson 2010, p. xii). This is particularly the case with postcard panoramas, of which Blakemore’s is one. Panoramas rise high above the lived experience of a landscape which must be eked out at ground level, but they appear to offer, at a glance, a comprehensive account of the city: its architectural types, its traffic routes, its reach, its environs. All this from a position that can never be occupied except as a viewpoint: an ideal place. The idealisation of the panorama compliments that of the unvarying view.

The recipient of the postcard will glance down upon its elevated view as it is held between their thumb and index finger. Half an arm’s length away, between a hand and an eye, an entire city appears as a focal point within a domestic field of vision: the glass and wood of the inside of a front door, the carpeted stairs, the cups and plates on a kitchen table. The commanding position of the photographer over Santiago and the magnifying apparatus of the camera is mimicked and partially recaptured, by the recipient of the postcard. In this way, a Chilean landscape is presented and Santiago is made known in London.

A cross has been added to the picture postcard view. There are two short diagonal strokes of blue biro halfway up in the right third, marking the place where the sender, Harold Blakemore, is staying. Just the cross instates what Esther Milne calls the ‘“here and now” of corporeality’ (Milne 2010, p. 15). The entire reverse of the picture postcard performs this function. Harold Blakemore explained to his children, to whom the card was addressed, that the position of the cross was ‘a bit of a guess.’ ‘But’, he continued:

as you can see, when I wake up in the morning and walk out on my verandah, I can see the mountains shining in the sun. It is very hot here and there are no clouds in the sky. The temperature today is over a 100 degrees Fahrenheit, but there is always a cooling breeze coming from the mountains. Tell Mummy I had lunch today with Gabriel who is much looking forward to seeing you all in January, and that I shall be seeing Mercedes tomorrow. I will write her long letter soon. I hope that you are all well and you are being very good. I am having a very interesting and busy time, but am going to the seaside for a weekend at the end of October. So I am planning to have a rest now and then.All my love,Daddy.P.S. Give my love to Whisky and Snowy.(Blakemore 1993) (Figure 11) Figure 11. Santiago, Luz de Atardecer, con Vista de la Cordillera de Los Andes. Reverse. The Harold Blakemore Latin American Archive, Special Collections, J. B. Priestley Library, University of Bradford.

Figure 11. Santiago, Luz de Atardecer, con Vista de la Cordillera de Los Andes. Reverse. The Harold Blakemore Latin American Archive, Special Collections, J. B. Priestley Library, University of Bradford.

Blakemore’s strategies of writing, despite the formal typed script, are intimate, intended to make himself present to his children and to draw them into his place and his time: see where I am, see what I see. His is an attempt to include his family in the same visual world despite their distance from it. Even the banality of reverse postcard descriptions of the weather, written by the dutiful tourist with not much to say and that space on the back of the postcard to fill, are not empty sentences. They are an invitation to share a sensory world, often also asking for sympathy: these are the conditions affecting me when I am not with you. Harold Blakemore wants to both surprise and reassure his children; he would be impossibly hot, he explains, although manages well because he feels the breeze from the snow-topped mountains that he sees in the morning light. This postcard as other acts of writing between correspondents, shows the effort, as Milne notes, ‘to collapse the time and distance that separates them.’ His requests to his children to speak for him to both their mother and their pets, are redundant except as an attempt to disregard the temporal and spatial realities. His postcard will certainly arrive after tomorrow’s meeting with Mercedes and his long letter written long before the postcard arrives.

The postcard is a record of time and place. I am writing to you now from here. Join me. The cross inserts Blackmore into the cityscape as he invites his children to experience the view from his verandah. Time and place asserted by the diagonal biro strokes on the image of the city on the postcard’s front are underscored by writing on its back. The image ought to be the imprint of the unrepeatable moment, the here and now of photography, onto the card, since that is the technology from which it derives. But reality briefly reproduced as the shutter over the camera lens opens and closes to light, is too overlaid by idealisation to perform entirely as photography; the particular and the passing moment are subsumed by a more generic notion of geographical and historical place. Santiago is expressed by the postcard only as an ideal form; its real moment in time is carried by the act of writing and sending the postcard rather than the photographic image. The panorama then appears historical rather than idealised, as if the moment of its written exchange is the moment of the image, which it is not. Harold Blakemore dated the postcard ‘20/10/75.’ It has been two years and more than month since the military coup.

But, it is as if nothing happened because the city, in its overview, has stayed the same. I want to ask: where are the landmarks of military dictatorship? Where is the detention and torture centre, Villa Grimaldi? What of the five thousand prisoners held between 1974 and 1977? Are there any signs of those held in Santiago? Where are the poblaciones (districts) from which the disappeared were taken? They are not here. The image does not lie. They are not hidden or erased. They exist on a different picture plane, but they have never been here under the azure skies of the postcard. The tortured, the disappeared, the dead, never existed in this ideal view far above the lived experience. In the postcard summary of the city, in its generic form, all appears unchanged.

Yet, the postcard counts as an historical record; it has a precise historical referent: a time and place. The small rectangle is a broad canvas onto which the words of the sender insists it is a document of reality. This is here, says Harold Blakemore to his children, this is now.

The postcard presents a problem of a different order to that usually associated with images of conflict, with pictures of war. Since the publication of Susan Sontag’s, On Photography, those interested in the potential and limitations of photography of conflict have examined its inoculating effect (Sontag 1977). The visual testimony to the terrible acts of war, the photojournalist’s attempt to demonstrate the destruction of life in order to preserve it in the future, usually fail. Apathy spreads out over the viewers; the horror is too much. Either a photograph of war is too difficult to gaze upon, or if some contemplation of that image is possible, another more awful image soon overtakes it, nullifying its capacity to alert its viewer to take action. A dose of atrocity photographically reproduced will guarantee a lack of effect. Looking at images of war and pictures of conflict, and looking away, amount to the same thing: the viewer is overwhelmed by reality, stops looking, and ceases any concern for life or regard for ‘the pain of others’ (Sontag 2003).

Sontag’s criticism of the denuded power of the photography of atrocity changed over time. In her last piece published in the New York Times Magazine, which addressed the photographs taken by United States soldiers of their own acts of torture of Iraqis held in Abu Ghraib prison, she explored the attempts to contain the power of conflict photography. Sontag observed that photographs themselves were considered the problem rather than the inhuman, degrading treatment of prisoners following the second US invasion of Iraq in 2003. There was ‘the displacement of the reality onto the photographs themselves’ (Sontag 2004). They interrupted the Bush administration’s media narrative as if that narrative was the war itself. Yet, their residual power as an exposure of an event of a time and in a place, of the actual event in here and now, was a spike of reality in US policy: ‘Considered in this light,’ states Sontag, ‘the photographs are us’ (Sontag 2004).

The unvarying postcard image of the city under azure skies poses a larger problem than that to which Susan Sontag has alerted us: all those attempts to avoid the power of photography are responses to its exposure of reality, the horror seen before it is suppressed. Postcard photography is on another plane of existence. Such images are summaries of landscapes made still and stable; they are not timeless but so lacking in specificity that political realities cannot be seen; they are lost from view.

5. Loss and the Landscape

Loss is not evident in the pristine postcard image. The postcard presents Harold Blakemore’s view in more than one respect. He concluded British Nitrates and Chilean Politics by refuting that the past actions of José Balmaceda could have averted the loss of Chile’s future, that they changed the ‘course of history’ as ‘suggested’ by ‘marxists’. Certainly, this is the case made by Andre Gunder Frank. Chilean nitrate is one of the economic studies through which he explains underdevelopment as the condition of capitalism, not the condition that its expansion could solve: extraction of surplus value through processes of production of capitalism is writ large over the world as material values of land and labour are taken from a colonialised periphery to a colonialising centre. In Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Latin America, Gunder Frank did indeed infer that if Balmaceda’s supporters won over the Congressional forces and were aided by British nitrate traders, the historical transformation of loss from satellite to metropolis might have halted. He wrote:

My review of Chilean experience suggested that there may have been times in which even certain structural changes within Chile’s capitalist structure might have materially changed the course of the country’s remaining history. When these changes were not made, all the attempts to make them were not carried out as the circumstances of the times required, these opportunities—such as investment of the economic surplus produced in Chile’s nitrate mines—were lost forever. The experiences of Chile suggest that the history of the development of underdevelopment in many parts of the world was—and still is—punctuated by such failure to take advantage of opportunities to eliminate or shorten the suffering created by underdevelopment.(Gunder Frank [1969] 1971)

All mining makes a loss. Useful and valuable materials are extracted from the earth to leave the useless and valueless. Lands are emptied of their substances and their spoils are scattered. Mining industries expand rapidly as markets for newly unearthed substances boom. The rushes for future materials and the value they hold send fertile earth into a scene of slag heaps and vast dumps. The faster materials are extracted, the quicker the slump, resulting in an accelerated fall in value that leaves only waste: a material loss.

The loss of mined nitrate is profound. Its substance disappears. Chilean nitrate is sodium nitrate, a salt, NaNO3. Sodium nitrate is soluble in water and once lixiviated, that is, separated from caliche, the Desert rocks, it crystalises into the chemical form that can be sold as a fertiliser and explosive. It is nitrogen, 80 per cent of the earth’s atmosphere materialised in the compound sodium nitrate that has an accelerating effect upon plant growth and a yet more dynamic, destructive force upon the environment, which makes it such a desirable substance: an element of the Earth in commodity form. Once the salty, irritant crystals of nitrate were shovelled into bags, loaded onto trains that crossed the Atacama Desert, loaded again into warehouses, and again onto lighters to take them to the ships sailing to British ports, they were ready and waiting, as shares and profits in the nitrate trade rose or fell, to be transformed, to disappear into something else. Nitrate was dug into the soils of northern Europe. Late nineteenth century farmers liked its quickening effect upon the beets they used to feed the cows they slaughtered to feed the expanding urban markets. It became a chemical commodity lost in a western food supply chain, in another continent’s nitrogen cycle, altering the structure of soils, polluting rivers and seas after it accelerated into another form and then drained away.

Explosions are nitrate’s most dramatic disappearance. Mixed with equal amounts of sulphuric acid, nitrate was distilled to produce the nitric acid required for the manufacture of dynamite, nitroglycerine, and nitro-toluol necessary for TNT (trinitrotoluene). It was an ingredient in the industrialisation of war; it was, during the First World War, ‘more valuable than ever before’ insists Stephen Bown, for it filled ‘all armaments—from smokeless powder in canons and rifles, to mortars, mines and all other explosives’ (Bown 2005, p. 197). Moreover, its scarcity in Germany following the Allied blockade, led to the industrial production of a synthetic substitute. In 1913, BASF (Badische Anilin und Soda-Fabrik/Baden Aniline and Soda Factory) opened the chemical plant Oppau; Carl Bosch engineered the industrial structures for the commercial production of Fritz Haber’s laboratory process of ammonia synthesis; nitrogen and hydrogen were combined at high pressures and high temperatures. Initially, a relatively small-scale production at Oppau supplied fertiliser, but soon enough, the Haber-Bosch process sustained the German war effort. Known as ‘nitrogen fixation’, it created explosions from the air. Both natural and synthetic forms of nitrogen destroyed both human bodies and grass landscapes, turning both to mud: ‘craters within and without’ wrote Remarque in All Quiet on the Western Front (Remarque [1929] 1966).

The bodies mixed in the mud of the battlefields in France and Belgium are no longer there to see: former fronts are greened over. Loss appears in the outlines and atmosphere of landscapes. In the dust of the Atacama Desert, piled high on slag heaps, the signs of industrial work are everywhere, and a sense of lost labour is pervasive, but the effort of life is not annotated here as in an archive. Waste is difficult to decipher. It is in these wastelands that relatives of the desaparacidos still search for the bones of their sisters and sons, brothers and lovers, comrades and friends, dropped from aeroplanes and mixed with the residues of nitrate mining (Guzmán 2010).

6. Loss and the Archive

All archives are records of loss, of which the Harold Blackmore Latin American Archive at the University of Bradford is no exception. Historical loss is materialised in every archival artefact, from hand-written notes to picture postcards: each fallen from their place in the past to wait as the representative of that past for a visitor from the future, such as myself. I encountered one single moment of terrible loss. Nitrate mining in the nineteenth century and military intervention in the twentieth appeared as the same historical formation: the extraction and oppression of capitalism. It is difficult, from a twenty-first century perspective of living in global neo-liberal order, to see how it could be otherwise. Harold Blakemore’s hand-written and typed transcriptions of nitrate combinations that ‘will break’ at the close of 1886 or ‘Portents’ in 1970 of ‘US non-coop’ with the Allende’s Unidad Popular government, read as storm warnings (Benjamin 1992b) of the future violence of capital control of the Earth’s diminishing resources.

The Harold Blakemore Latin American Archive contains the material forms of writing a Chilean history in the 1970s; the flowing lines of ink pen or the impressions of mechanical keys on paper that ‘flash up’ danger also tell of the social conditions of academic life in post-war Britain and of another moment that is lost. Harold Blakemore represents a tradition of left-liberal empiricism; he asserts detail against the structural analysis of Marxist theory, particularly that of the development of underdevelopment of Latin America associated with the work of Gunder Frank. There is, of course, a structural explanation, if not analysis, for post-war liberal empiricism; it derives from its historical conditions. The son of a Yorkshire miner and trade unionist himself, Harold Blakemore was part of the generation that benefited from the progressive reforms of the period of the post-war welfare state that encouraged optimism about economic and political development throughout the same ‘post-colonial’ period. The egalitarianism of expanding state institutions and the social stability of traditional ones, such as the family, fostered the dedication of Blakemore’s generation, regardless of whether they were miners or academics, although they were usually men, to public work. He could examine every detail of the domestic politics of nitrate mining in the nineteenth century and establish himself in his field in the public sector. His position also enabled him to work beyond its boundaries, in the private sector, in the global market. Between 1972 and 1985, he was a member of the Latin American Trade Advisory Group; he was a consultant to Lloyds bank for 12 years and to Control Risks, an ‘independent’ global security consultancy, through the 1980s. ‘Harold truly cared for Chile’ wrote William Sater, one of his obituary writers (Sater 1991, p. 864). The ‘Preface’ to British Nitrates and Chilean Politics best expresses his care, the paternalism of the post-war period: ‘If this book had a dedication it would be to the land and people of Chile, and it has been written as a contribution to the better understanding of their history by one who will always regard them with sympathy and affection’ (Blakemore 1974).

7. La Luz

The postcard of light over the cityscape of Santiago sent back to London in 1975 connects these two places, a vivid trace of historical and geographic relation between nineteenth century economic exploitation and twentieth century political repression. It is a colourful denial of conflict when viewed as an image, but within its archive, it performs the ‘prismatic’ work of the peripheral artefact, a shard that disperses light over the contents of the adjacent documents of once discontinuous histories: the 1891 Civil War in Chile and the First World War in Europe, nineteenth monopoly capital and twentieth century security culture, nitrate mining and the 1973 coup. The light captured in the postcard image and that about which Harold Blakemore wrote to his children is refracted from its cardboard surface.

Funding

This research was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), grant number AH/I021671/1 and AH/R001391/1

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Aguilera, Carolina. 2014. Memories and Silences of a Segregated City: Monuments and Political Violence in Santiago, Chile, 1970–1991. Memory Studies 8: 102–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, Walter. 1992a. Theses on the Philosophy of History. Edited by Hannah Arendt. London: Fontana. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Walter. 1992b. Unpacking My Library. Edited by Hannah Arendt. London: Fontana. [Google Scholar]

- Billig, Michael. 1995. Banal Nationalism. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore, Harold. 1974. British Nitrates and Chilean Politics, 1886–1896: Balmacda and North. London: Athlone Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore, Harold. 1993. Private Letters to Partners 1884 to 1891; Postcards. Bradford: The Harold Blakemore Latin American Archive, Special Collections J. B. Priestley Library, University of Bradford. [Google Scholar]

- Bown, Stephen R. 2005. A Most Damnable Invention: Dynamite, Nitrates and the Making of the Modern World. New York: Thomas Dunne Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Joseph R. 1963. Nitrate Crises, Combinations, and the Chilean Government in the Nitrate Age. The Hispanic American Historical Review 43: 230–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, Antionette. 2001. Thinking beyond the Boundaries: Empire, Feminism and the Domains of History. Social History 26: 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Cath, Katherine Hite, and Alfredo Joignant, eds. 2013. The Politics of Memory in Chile: From Pinochet to Bachelet. London: First Forum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edensor, Tim. 2002. National Identity, Popular Culture and Everyday Life. Oxford: Berg. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, David J. 1991. Harold Blakemore (1930–1991): An Appreciation. Bulletin of Latin American Research 10: 333–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gunder Frank, Andre. 1971. Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Latin America. Middlesex: Penguin Books. First published 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, Patricio. 2010. Nostalgia de la Luz. Brooklyn: Icarus Films. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, Robert. 1884–1885. Machinery for the Manufacture of Nitrate of Soda at the Ramirez Factory; No, Northern Chili. In Proceedings of the Institute of Civil Engineers. London: Institute of Civil Engineers, Paper No. 2086. pp. 337–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, William. 2005. From the Moselle to the Pyrenees: Commemoration, cultural memory and the ‘debatable lands’. Journal of European Studies 35: 114–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, Esther. 2010. Letters, Postcards, Email: Technologies of Presence. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Monteón, Michael. 1975. The British in the Atacama Desert: The Cultural Bases of Economic Imperialism. The Journal of Economic History 35: 117–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteón, Micheal. 1979. The Enganche in the Chilean Nitrate Sector, 1880–1930. Latin American Perspectives 6: 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture. 2005. The Valech Report. Available online: http://www.comisiontortura.cl (accessed on 5 November 2018).

- Nora, Pierre. 1989. Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Memoire. Representations 26: 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollen, Annebella. 2016. Mass Photography: Collective Histories of Everyday Life. London: I. B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska, David, and Jordanna Mendelson. 2010. Introduction. Postcards: Ephemeral Histories of Modernity. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Remarque, Erich Maria. 1966. All Quiet on the Western Front. London: Folio Society. First published 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Sater, William F. 1991. Harold Blakemore (1930–1991). The Hispanic American Historical Review 71: 863–64. [Google Scholar]

- Siegert, Bernhard. 1997. Relays: Literature as an Epoch of the Postal System. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag, Susan. 1977. On Photography. New York: Dell. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag, Susan. 2003. Regarding the Pain of Others. London: Hamish Hamilton. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag, Susan. 2004. Regarding the Torture of Others. The New York Times Magazine. May 23. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/2004/05/23/magazine/regarding-the-torture-of-others.html (accessed on 10 December 2017).

- Stallabrass, Julian. 1996. Gargantua: Manufactured Mass Culture. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Steedman, Carolyn. 2002. Dust. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, Steve. 2010. Reckoning with Pinochet: The Memory Question in Democratic Chile, 1989–2006. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stieber, Nancy. 2010. Postcards and the Invention of Old Amsterdam Around 1900 in Prochaska, David and Mendelson, Jordanna. Postcards: Ephemeral Histories of Modernity. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | See William Kidd’s work for a critique of Pierre Nora’s own act of forgetfulness, the absence of consideration of how French national memory was shaped by colonial power and takes a form of nostalgia for nation and empire (Kidd 2005). Here, there is an attempt to lever out of its European national context the sense of loss described by Nora and use it to illuminate the colonial condition of history and memory in Chile under military dictatorship of the 1970s and 1980s. Most work on memory is focused on the following ‘post-dictatorship’ period (Stern 2010; Collins et al. 2013). |

| 2 | Carolina Aguilera argues for a longer periodisation of political violence, from 1970–1991 (Aguilera 2014, p. 103). |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).