Odysseus and the Cyclops: Constructing Fear in Renaissance Marriage Chest Paintings

Abstract

:When the beam … was nearly at the point of catching fire and glowed, terribly incandescent … [the men] seized the beam of olive, sharp at the end, and leaned on it into the eye, while I from above leaning my weight on it twirled it, like a man with a brace-and-bit who bores into a ship timber … So seizing the fire-point-hardened timber we twirled it in his eye, and the blood boiled around the hot point, so that the blast and scorch of the burning ball singed all his eyebrows and eyelids, and the fire made the roots of his eye crackle. As when a man who works as a blacksmith plunges a screaming great ax blade or plane into cold water … even so Cyclops’ eye sizzled about the beam of the olive. He gave a giant horrible cry and the rocks rattled to the sound, and we scuttled away in fear. He pulled the timber out of his eye, and it blubbered with plenty of blood, then when he had frantically taken it in his hands and thrown it away, he cried aloud to the Cyclopes.24(Od. IX.378–99 [147])

If, as new husbands usually do, you don’t want to lose their still precarious favor, you may ask your in-laws in restrained and casual words [about the balance of the dowry]. Then you are forced to accept any little excuse they may offer. If you make a more forthright demand for what is your own, they will explain to you their many obligations, will complain of fortune, blame the conditions of the time, complain of other men, and say that they hope to be able to ask much of you in greater difficulties. As long as they can, in fact, they will promise you bounteous repayment at an ever-receding date. They will beg you, and overwhelm you, nor will it seem possible for you to spurn the prayers of people you have accepted as your own family. Finally, you will be put in a position where you must either suffer the loss in silence or enter upon expensive litigation and create enmity.

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, William Scovil. 2005. The Art of the Aeneid, 2nd ed.Mundelein: Bolchazy-Carducci. [Google Scholar]

- Baskins, Cristelle L. 1998. Cassone Painting, Humanism, and Gender in Early Modern Italy. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baskins, Cristelle L. 2002. (In)Famous Men: The Continence of Scipio and Formations of Masculinity in Fifteenth-Century Tuscan Domestic Painting. Studies in Iconography 23: 109–36. [Google Scholar]

- Baskins, Cristelle L., Adrian W. B. Randolph, and Jacqueline Marie Musacchio. 2008. The Triumph of Marriage: Painted Cassoni of the Renaissance. Boston: Isabella Steward Gardner Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Marc Bizer, trans. 2011, Homer and the Politics of Authority in Renaissance France. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Botley, Paul. 2004. Latin Translation in the Italian Renaissance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Christopher G. 1996. In the Cyclops’ Cave: Revenge and Justice in Odyssey 9. Mnemosyne 49: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brucker, Gene A. 1986. Giovanni and Lusanna: Love and Marriage in Renaissance Florence. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bruni, Leonardo. 2010. Rerum suo Tempore Gestarum Commentarius. Edited by Anthony Grafton, Glenn W. Most and Salvatore Settis. The Classical Tradition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cachey, Theodore J., Jr. 2009. Between Petrarch and Dante, Prolegomenon to a Critical Discourse. In Petrarch & Dante: Anti-Dantism, Metaphysics, Tradition. Edited by Zygmunt G. Baranski and Theodore J. Cachey Jr. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, pp. 3–49. [Google Scholar]

- Callmann, Ellen. 1974. Apollonio di Giovanni. Oxford: Oxford University Press, nos. 3–5, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Celenza, Christopher S. 2016. An Imagined Library in the Italian Renaissance: The Presence of Greek in Angelo Decembrio’s De politia literaria. In For the Sake of Learning: Essays in Honor of Anthony Grafton. Edited by Ann Blair and Anja-Silvia Goeing. Leiden: Brill, vol. 1, pp. 393–403. [Google Scholar]

- Chabot, Isabelle. 2011. La Dette des Familles: Femmes, Lignage et Patrimoine à Florence aux XIVe et XVe siècles. Rome: École française de Rome. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Howard W. 1967. The Art of the Odyssey. Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Howard W. 1981. Homer’s Readers: A Historical Introduction to the Iliad and the Odyssey. Newark: University of Delaware Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crabb, Ann. 2000. The Strozzi of Florence. Widowhood and Family Solidarity in the Renaissance. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong, Irene J. F., ed. 1998. Homer: Critical Assessments. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dué, Casey. 2005. Homer’s Post-Classical Legacy. In A Companion to Ancient Epic. Edited by John Miles Foley. Malden: Blackwell, pp. 397–414. [Google Scholar]

- Everson, Jane. 2001. The Italian Romance Epic in the Age of Humanism: The Matter of Italy and the World of Rome. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri, Lorenzo. 1991. Alleanza Matrimoniale e Patriziato Nella Firenze del Quattrocento. Studio sulla Famiglia Strozzi. Florence: Olschki. [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri, R. 1997. Sulle traduzioni umanistiche da Omero. In Posthomerica I. Tradizioni Omeriche Dall’antichità al Rinascimento, Pubblicazioni del Dipartimento di Archeologia, Filologia Classica e Loro Tradizioni 173. Edited by F. Montanari and S. Pittaluga. Genova: Dipartimento di archeologia, filologia classica e loro tradizioni, pp. 99–124. [Google Scholar]

- Fenzi, Enrico. 2003. Tra Dante e Petrarca: Il fantasma di Ulisse. In Saggi petrarcheschi. Fiesole: Cadmo, pp. 492–517. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentino, V. D. B. 1951. Vita di uomini illustri del secolo XV. Edited by P. d’Ancona and E. Aeschlimann. Milan: Toulouse. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, Philip. 2007. De Troie à Ithaque: Réception des Épopées Homériques à la Renaissance. Geneva: Librairie Droz. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, Margaret. 2006. Boccaccio’s Heroines: Power and Virtue in Renaissance Society. Burlington, VT and Aldershot: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, Margaret. 2014. Virgil and the Femina Furens: Reading the Aeneid in Renaissance Cassone Paintings. Vergilius 60: 127–44. [Google Scholar]

- Freccero, John. 1986. Dante: The Poetics of Conversion. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli, Maria Cristina. 2001. The Flight of the Vernacular: Seamus Heaney, Derek Walcott and the Impress of Dante. Amsterdam: Rodopi. [Google Scholar]

- Grafton, Anthony. 1992. Renaissance Readers of Homer’s Ancient Readers. In Homer’s Ancient Readers: The Hermeneutis of Greek Epic’s Earliest Exegetes. Edited by Robert Lamberton and J. J. Keaney. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 149–72. [Google Scholar]

- Grendler, Paul F. 2002. The Universities of the Italian Renaissance. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, Olivia. 2008. Dante’s Two Beloveds: Ethics and Erotics in the Divine Comedy. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Horkheimer, Max, and Theodor W. Adorno. 2002. Dialectics of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments. Edited by Gunzelin Noerr. Translated by Edmunds Jephcott. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Joost-Gaugier, Christiane. 1982. The Early Beginnings of the Notion of Uomini Famosi and the De viris illustribus in Greco-Roman Literary Tradition. Artibus et Historiae, 97–115. [Google Scholar]

- Kallendorf, Craig. 1989. In Praise of Aeneas: Virgil and Epideictic Rhetoric in the Early Italian Renaissance. Hanover: University Press of New England. [Google Scholar]

- Kallendorf, Craig. 1999. Virgil and the Myth of Venice: Books and Readers in the Italian Renaissance. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kallendorf, Craig. 2007. The Other Virgil: ‘Pessimistic’ Readings of the “Aeneid” in Early Modern Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kanter, Laurence B. 2000. Rethinking the Griselda Master. Gazette des Beaux-Arts 135: 147–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, Douglas, and Martin L. McLaughlin. 1995. Literary Imitation in the Italian Renaissance. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kircher, Timothy. 2014. Wrestling with Ulysses: Humanist Translations of Homeric Epic around 1440. In Neo-Latin and the Humanities: Essays in Honour of Charles E. Fantazzi. Edited by Luc Deitz, Timothy Kircher and Jonathan Reid. Essays and Studies 32. Toronto: Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, pp. 61–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kirshner, Julius. 1993. Materials for a Gilded Cage: Non-Dotal Assets in Florence, 1300–1500. In The Family in Italy from Antiquity to the Present. Edited by David I Kertzer and Richard P. Saller. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 184–207. [Google Scholar]

- Kirshner, Julius. 2002. Li Emergenti Bisogni Matrimoniali in Renaissance Florence. In Society and Individual in Renaissance Florence. Edited by William J. Connell. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, pp. 79–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kirshner, Julius. 2015. Marriage, Dowry, and Citizenship in Late Medieval and Renaissance Italy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Klapisch-Zuber, Christiane. 1985. Women, Family, and Ritual in Renaissance Italy. Translated by Lydia Cochrane. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krohn, Deborah L. 2008. Marriage as a Key to Understanding the Past. In Art and Love in Renaissance Italy. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn, Thomas. 1991. Law, Family & Women: Toward a Legal Anthropology of Renaissance Italy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn, Thomas. 2016. Property of Spouses in Law in Renaissance Florence. In Family Law in and Society in Europe from the Middle Ages to the Contemporary Era. Edited by Maria Gigliola di Renzo Villata. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- McKnight, Kate Denny. 1924. The Ulysses Panels by Piero di Cosimo at Vassar College. The Art Bulletin 6: 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miziolek, Jerzy. 2006. The ‘Odyssey’ Cassone Panels from the Lanckoroński Collection: On the Origins of Depicting Homer’s Epic in the Art of the Italian Renaissance. Artibus et Historiae 27: 57–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miziolek, Jerzy. 2016. Ulysses, Penelope and the Charm of the Sirens’ Song. In Renaissance Wedding and the Antique: Italian Secular Paintings from the Lanckoronski Collection. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony Molho, trans. 1994, Marriage Alliance in Late Medieval Florence. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Montiglio, Silvia. 2011. From Villain to Hero: Odysseus in Ancient Thought. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, Jennifer Klein. 1992. Apollonio di Giovanni’s “Aeneid” Cassoni and the Virgil Commentators. Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin, 26–47. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, Stephen. 1997. The Gift of Immortality: Myths of Power and Humanist Poetics. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Myrsiades, Kostas. 2001. Homer, 1715–1996—Homer: Critical Assessments by Irene J. F. DeJong. College Literature 28: 171–77. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, Rick M. 2008. Assembly and Hospitality in the “Cyclopeia”. College Literature 35: 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicols, John. 2011. Hospitality among the Romans. In The Oxford Handbook of Social Relations in the Roman World. Edited by Michael Peachin. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 422–37. [Google Scholar]

- Nybakken, Oscar E. 1946. The Moral Basis of Hospitium Privatum. The Classical Journal 41: 248–53. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan, James N. 1987. Observations on the Kyklopeia. Symbolae Osloenses 62: 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padoan, Giorgio. 1977. Ulisse ‘fandi fictor’ e le vie della sapienza. Momenti di una tradizione (da Virgilio a Dante). In Il pio Enea e l’empio Ulisse: Tradizione classica e intendimento medievale in Dante. Ravenna: Longo, pp. 170–99. [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri, Matteo. 1982. Vita Civile. Edited by Gino Belloni. Florence: Sansoni. [Google Scholar]

- Pertusi, Agostino. 1964. Leonzio Pilato fra Petrarca e Boccaccio: Le sue Versioni Omeriche Negli Autografi di Venezia e la Cultura Greca del Primo Umanesimo. Venice: Istituto per la collaborazione culturale. [Google Scholar]

- Poliziano, Angelo. 2004. Silvae. Translated and Edited by Charles Fantazzi. The I Tatti Renaissance Library 14. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Poliziano, Andrea. 2007. Oratio in Expositione Homeri. Edited by Paola Megna. Edizione Nazionale dei testi umanistici 7. Rome: Edizioni di storia e letteratura. [Google Scholar]

- Pontani, Filippomaria. 2005. Sguardi su Ulisse: La Tradizione Esegetica Greca all’Odissea, Sussidi eruditi 63. Rome: Edizioni di storia e letteratura, pp. 341–534. [Google Scholar]

- Pontani, Filippomaria. 2007. From Budé to Zenodotus: Homeric Readings in the European Renaissance. International Journal of the Classical Tradition 14: 375–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöschl, Victor. 1950. Die Dichtkunst Vergils: Bild und Symbol in der Aeneis. Innsbruck: Margareta Friedrich Rohrer. [Google Scholar]

- Reece, Steve. 1993. The Stranger’s Welcome: Oral Theory and the Aesthetics of the Homeric Hospitality Scene. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schein, Seth L. 1970. Odysseus and Polyphemus in the Odyssey. Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 11: 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Schubring, Paul. 1923. Cassoni, Truhen und Truhenbilder der Italienischen Frühhrenaissance. Leipzig: Hiersemann, nos. 245–52. [Google Scholar]

- Segal, Charles. 1992. Divine Justice in the Odyssey: Poseidon, Cyclops, and Helios. American Journal of Philology 113: 489–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siren, Osvald, and Maurice Walter Brockwell. 1917. Catalogue of a Loan Exhibition of Italian Primitives. New York: F. Kleinberger Galleries. [Google Scholar]

- Sowerby, Robin. 1996. The Homeric “Versio Latina”. Illinois Classical Studies 21: 161–202. [Google Scholar]

- Sowerby, Robin. 1997. Early Humanist Failure with Homer. International Journal of the Classical Tradition 4: 37–63, 165–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford, William Bedell. 1963. The Ulysses Theme: A Study in the Adaptability of a Traditional Hero. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. First published 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Stefaniak, Regina. 2008. Mysterium Magnum: Michelangelo’s Tondo Doni. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Strozzi, Alessandra Macinghi. 1997. Selected Letters of Alessandra Strozzi, bilingual ed. Translated by Heather Gregory. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vandiver, Elizabeth. 2012. ‘Strangers are from Zeus’: Homeric Xenia at the Courts of Proteus and Croesus. In Myth, Truth, and Narrative in Herodotus. Edited by Emily Baragwanath and Mathieu de Bakker. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 143–66. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Naquet, Pierre. 1991. Le Chasseur noir. Formes de Pensée et Formes de Société dans le Monde Grec. Paris: La Découverte, pp. 39–68. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, Neu. 1969. The Family in Renaissance Florence. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- West, Emily Blanchard. 2005–2006. An Indic Reflex of the Homeric Cyclopeia. The Classical Journal 101: 125–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson-Okamura, David Scott. 2010. Virgil in the Renaissance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zerba, Michelle. 2017. Renaissance Homer and Wedding Chests: The Odyssey at the Crossroads of Humanist Learning, the Visual Vernacular, and the Socialization of Bodies. Renaissance Quarterly 70: 831–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Quoted and trans. from (Bruni 2010, p. 812). For the attempts of prominent quattrocento humanists to grapple with ancient Greek and its translations, see (Kircher 2014); and (Botley 2004). |

| 2 | See, for example, (Ford 2007); and (Grafton 1992). |

| 3 | Angelo Poliziano, “In Explanation of Homer,” quoted and trans. in (Clarke 1981, p. 63). See (Poliziano 2007); also (Poliziano 2004, pp. 68–109). |

| 4 | (Sowerby 1997). See also (Wilson-Okamura 2010, esp. pp. 124–32). Of course, the myth of Troy endured in other literary forms; see (Dué 2005); and (Montiglio 2011). |

| 5 | (Zerba 2017). This phenomenon has also been recognized in Apollonio’s treatment of Virgil’s Aeneid; see, for example, (Franklin 2014); and (Morrison 1992). |

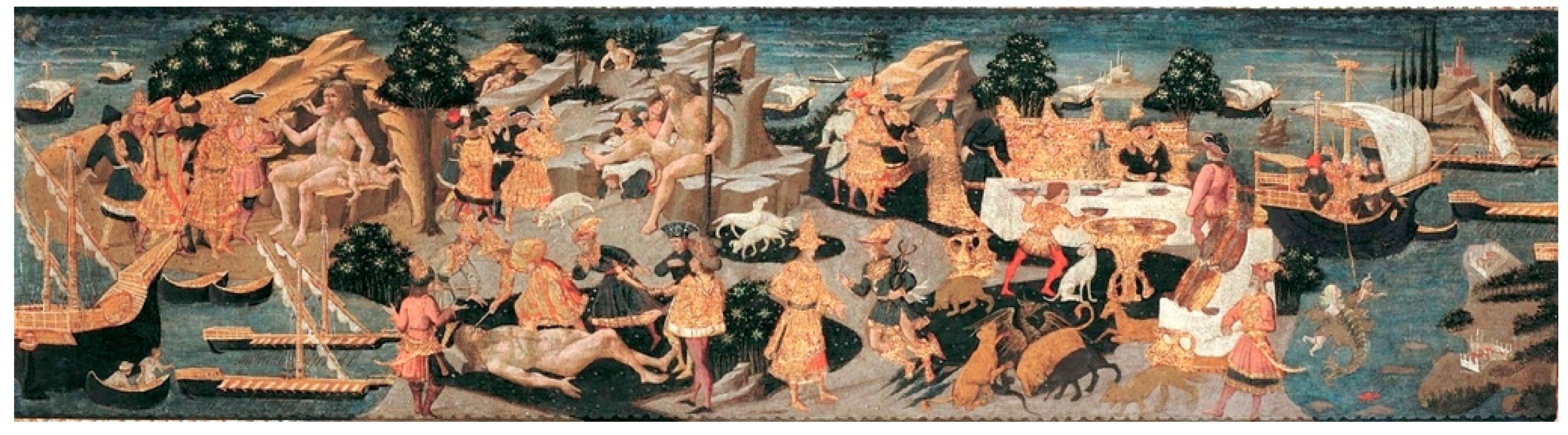

| 6 | For attribution history and dating of these panels, see (Miziolek 2006, p. 58). |

| 7 | For scholarship and comprehensive bibliographies related to Renaissance cassoni and their decoration, see (Baskins et al. 2008); (Franklin 2006); and (Baskins 1998). |

| 8 | For a good overview of ancient and medieval treatments of the character of Odysseus, see (Stanford [1954] 1963). See also, for example, (Dué 2005); and (Montiglio 2011). |

| 9 | Florentine Chancellor Coluccio Salutati, for example, found these translations, in which Latin was interpolated word-for-word above the Greek, “barbarous and unsophisticated … bloodless and inelegant.” Quoted from a letter written to Antonio Loschi in 1392, trans. Sowerby, “Humanist Failure,” (Sowerby 1997, p. 57). Sowerby finds Pilato’s work to read “strangely with many awkward and unidiomatic Latin expressions” that “do not consistently provide a reliable key to the primary meaning” (Sowerby 1997, p. 186). For the humanist response to Pilato, see also (Pertusi 1964); (Sowerby 1996); and (Fabbri 1997). Pier Candido Decembrio’s partial revision (c.1440) and Lorenzo Valla’s prose translation of the Iliad (c.1444) did little to improve on Pilato’s; see (Sowerby 1997, “Humanist Failure,” p. 186). Petrarch’s Pilato manuscripts are now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (ms lat. 7880(1) and 7880(2)). |

| 10 | This panel’s pendant has not been identified; its subject matter therefore remains unknown. |

| 11 | A fourth panel adaptation of the first Kraków panel is now in the Museo Stibbert, Florence. The current whereabouts of two other similar adaptations are unknown, though they have been preserved through photographs. Odyssey panels have been catalogued by (Schubring 1923); and (Callmann 1974). |

| 12 | The only figure depicted from the apologoi in this panel is Calypso, who prepares Odysseus’ boat for his journey home. Another small fragment of a cassone painting attributed to Apollonio and identified as Scene from the Odyssey: Calypso and Hermes is in the Harvard Fogg Museum. |

| 13 | (Callmann 1974, p. 17); (Miziolek 2006, “‘Odyssey’ Cassone Panels,” p. 66). For the Kraków panels, see also (Miziolek 2016). |

| 14 | A prominent and often-cited exemplar of these virtues in Renaissance Florence was the Roman general Scipio Africanus. Although a brilliant military mind, he was most frequently commemorated in the visual arts for refusing both to deflower a young virgin and accept ransom for her return. “The Continence of Scipio” was celebrated in cassone panels as well as in portraits of uomini famosi, which functioned as visual analogs of viri illustri encomia. The inscription beneath one such portrait reads, “A young girl was offered to me, superb booty; I would have been conquered, but I, who beat my enemies in war, conquered myself with reason: thus, I am worthy of a double triumph.” For this and other Scipio imagery, see (Baskins 2002, inscription on p. 113); also (Kanter 2000). |

| 15 | For Renaissance uomini famosi/donne illustri cycles, see, for example, (Joost-Gaugier 1982, 97–115); and (Franklin 2006). |

| 16 | (Bizer 2011, p. 21). For the tradition of reading Aeneas as a vir perfectus, see, for example, (Pöschl 1950); (Grendler 2002, pp. 235–72); (Kelly and McLaughlin 1995); (Kallendorf 1989); and (Wilson-Okamura 2010, pp. 208–12). |

| 17 | |

| 18 | For the limited humanist awareness of ancient Odyssey exegesis, see (Pontani 2005). The body of modern scholarship addressing earlier criticism is vast and nuanced; essential early works include (Stanford [1954] 1963); and (Clarke 1967, Art of the Odyssey). See also the four-volume anthology (De Jong 1998). Also valuable is the review of this collection by (Myrsiades 2001). For recent scholarship on Dante’s treatment of Odysseus, see (Holmes 2008); (Fumagalli 2001, pp. 19–30); (Freccero 1986, esp. 136–51); and (Padoan 1977). For recent Petrarch scholarship, see (Fenzi 2003); and (Cachey 2009). |

| 19 | “… you might give us a guest present or otherwise some gift of grace, for such is the right of strangers … Zeus the guest god, who stands behind all strangers with honors due them, avenges any wrong toward strangers and suppliants,” Od. IX.267–71 (144). |

| 20 | There is a vast body of scholarship addressing Renaissance veneration of the Aeneid; for recent work, see (Celenza 2016); (Wilson-Okamura 2010). |

| 21 | Aen. 3.802 (75). On the kinship of Homer’s Cyclopes to man, see, for example, (Brown 1996, p. 21); and (Segal 1992, p. 494). |

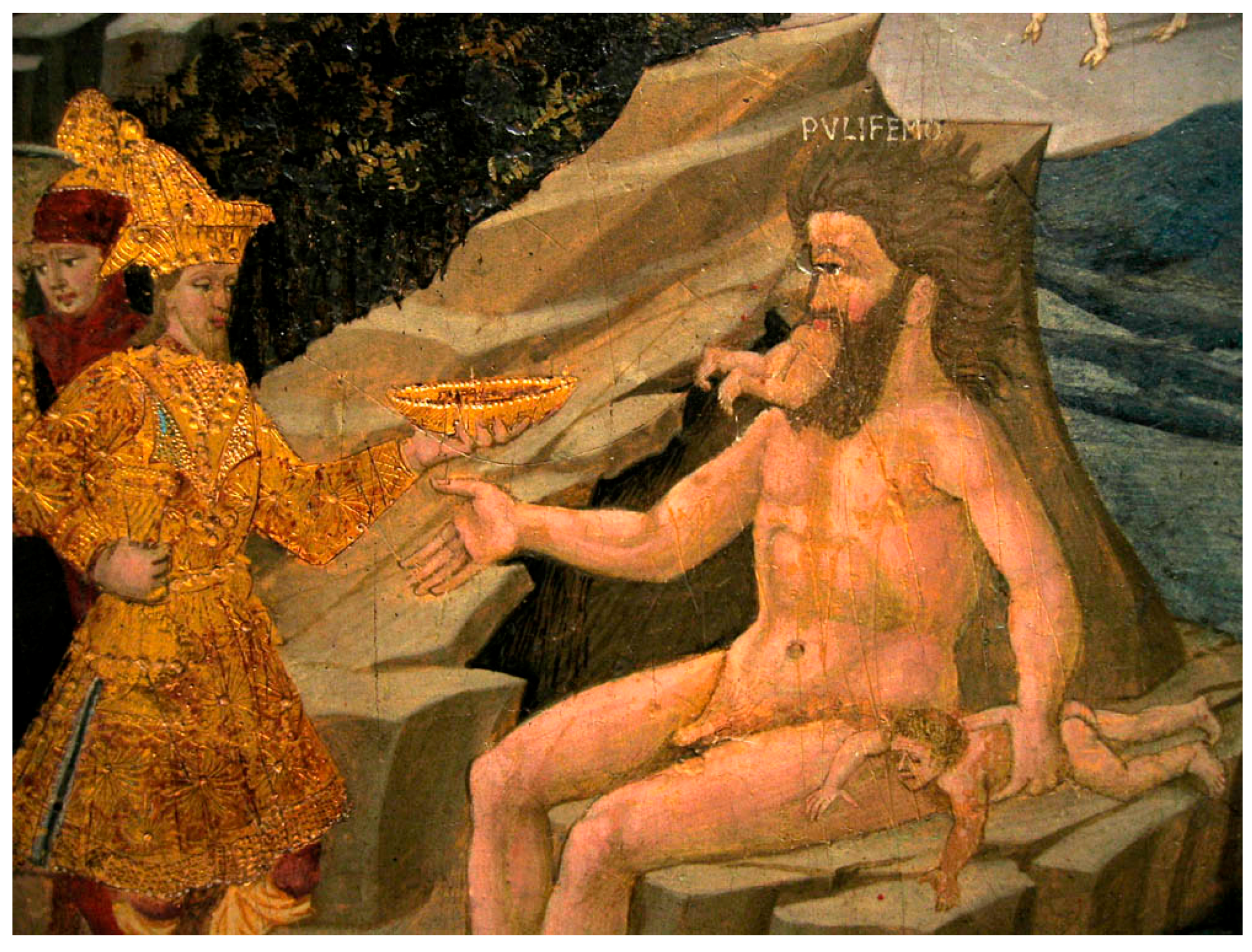

| 22 | Homer repeats that Polyphemus “prepared the men for dinner” two additional times; see Od. IX.311 (145) and Od. IX.344 (146). Most critics believe that Homer’s Polyphemus cooked the men before eating them; see, for example, (West 2005–2006, pp. 141–2); and (O’Sullivan 1987, p. 18). For a conflicting view, see (Schein 1970, pp. 74–5). |

| 23 | Aen. 3.822–23 (75). |

| 24 | |

| 25 | (Miziolek 2006, “The ‘Odyssey’ Cassone Panels,” p. 68). |

| 26 | See, for example, (Horkheimer and Adorno 2002, pp. 35–62); and (Vidal-Naquet 1991). My thanks to an anonymous reader for the following insightful observations: “[In this context] Ulysses’ dress makes him look like an allegory of a dowry: he is, after all, covered in what look to be coins … [also] the representation of cannibalism and of a nude (and, let’s be frank, erect) Polyphemus raises all sorts of questions about marriage and eroticism in the context of a cassone.” |

| 27 | For recent scholarship and references relevant to xenia, see (Vandiver 2012). |

| 28 | For a review of the proximate and extended obligations of hospitium and the ancient writings that elucidate them, see (Nicols 2011). Nicols quotes and translates Cicero (“quod sanctissimum est,” In Verrem 2.2.110), p. 424, and Seneca (“duo sacratissima inter homines … hospitium et adfinitas”: “two things are most sacred amongst men … hospitality and close relationships,” Con. 8.6.17), pp. 424–25. |

| 29 | (Molho 1994, p. 344). For the original Italian, see (Palmieri 1982, p. 161). |

| 30 | For recent work and references, see (Kirshner 2015, esp. pp. 55–73); (Krohn 2008); and (Molho 1994). |

| 31 | Lionardo, in Leon Battista Alberti, I libri della famiglia, Book Two (begun c. 1432), trans. Renée (Watkins 1969, p. 117). |

| 32 | For extended discussions of social homogamy, see (Brucker 1986, esp. pp. 94–108); and (Molho 1994). |

| 33 | In his study of Rinuccini marriages, Molho determines that “movement was not the prevalent marriage pattern among members of the Florentine propertied classes” whose marital unions were “more like cautious side steps rather than slides downward or climbs upward on the social scale (Molho 1994, p. 286).” |

| 34 | Vespasiano di Bicci uses gentilezza in this way throughout his biographies of famous men; see (Fiorentino 1951). For examples and analyses of quattrocento ideas of gentilezza, see (Stefaniak 2008, esp. pp. 127–29). |

| 35 | |

| 36 | A wealth of documentation attests to the frequent recourse to litigation, arbitration, and other legal measures in the interest of resolving dowry disputes. In addition to Kirshner, 2015, see (Kuehn 2016), and (Kuehn 1991); also (Chabot 2011). Foundational for study of the Florentine Renaissance dowry is (Klapisch-Zuber 1985). |

| 37 | For non-dotal assets, see (Kirshner 2015, pp. 55–73), and (Kirshner 1993). |

| 38 | See (Kirshner 2015, pp. 55–73). |

| 39 | For recent work and bibliographies on the theme of hospitality in the Cyclopeia, see (Newton 2008); and (Reece 1993). |

| 40 | For early Renaissance reading of epic poetry in “stark, black-and-white terms”, see (Kallendorf 2007, p. 33); and (Kallendorf 1999). |

| 41 | Little work has been done on this series beyond the reassessment of its attribution, which has been variously assigned to Piero di Cosimo, Francesco Granacci, and Antonio Pollaiuolo. See catalog entry by Osvald Siren and Maurice Walter Brockwell in (Siren and Walter 1917, pp. 101–3); and (McKnight 1924). |

| 42 | The figures on the left third of the panel are identified in the catalog as “Athena in the sky wreaking devastation on the walled city of Troy,” and “Ajax Oileus blasted by an angry Poseidon.” |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Franklin, M. Odysseus and the Cyclops: Constructing Fear in Renaissance Marriage Chest Paintings. Humanities 2018, 7, 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/h7040107

Franklin M. Odysseus and the Cyclops: Constructing Fear in Renaissance Marriage Chest Paintings. Humanities. 2018; 7(4):107. https://doi.org/10.3390/h7040107

Chicago/Turabian StyleFranklin, Margaret. 2018. "Odysseus and the Cyclops: Constructing Fear in Renaissance Marriage Chest Paintings" Humanities 7, no. 4: 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/h7040107

APA StyleFranklin, M. (2018). Odysseus and the Cyclops: Constructing Fear in Renaissance Marriage Chest Paintings. Humanities, 7(4), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/h7040107