Abstract

Literary animal studies are confronted with a systematic question: How can writing, as a human-made sign system, represent the nonhuman animal as an autonomous agent without falling back into the pitfalls of anthropomorphism? Against the backdrop of this problem, this paper asks how the medium of film allows for a different representation of the animal and analyzes two of Werner Herzog’s later documentary films. Although the depiction of animals and landscapes has always played a significant part in Herzog’s films, critical assessments of his work—including those of Herzog himself—tended to view the role of nature imagery as purely allegorical: it expresses the inner nature, the inner landscapes of the film’s human protagonists. This paper tries to open up a different view. It argues that both Grizzly Man and Encounters at the End of the World develop an aesthetic that depicts nonhuman nature as an autonomous and lively presence. In the close proximity amongst camera, human, and nonhuman agents, a clear distinction between nature and culture is increasingly blurred.

1. The White Whale

In Moby-Dick, whose legibility both as a novel and as a whale is constantly put into question, Ishmael reminds the reader that the sperm whale has never “written a book, or spoken a speech” (Melville 1983, p. 1164). Nonhuman animals do a lot of things, a lot of things human animals don’t quite understand. Even though the whale’s fin might cover bones whose structure is similar to that of a human hand, it never held a pen. Melville’s Leviathan does not step on the stage as the narrator of a novel that, after all, bears his name. This “pyramidical silence” (Melville 1983, p. 1164), as Ishmael puts it, marks a curious mismatch: As has been sufficiently stressed, Moby-Dick is steeped in cultural, economic and scientific discourses. Taken from “any book whatsoever, sacred or profane” (Melville 1983, p. 782), the vast abundance of ceteological knowledge and narratives that both constitutes the novel’s dusty paratextual library and structures its encyclopedic series of 135 chapters stands in stark contrast to what is said, told and known by the whale itself—which is nothing. Instead of being an autonomous subject, the whale becomes an eagerly sought-after object of understanding. The metabolic rhythm between surfacing in the air and submerging into an unfathomable depth seems to constitute an allegorical game of hide and seek with a narrator who is bound for a breathless chase. “Wonder ye then at the fiery hunt?” (Melville 1983, p. 1001). Unlike Ahab and similar to the reader, however, Ishmael is not hunting for revenge and blood but for a more pressing issue and a more subtle substance: meaning. Comparing the features of the whale’s bulky physiognomy to “wrinkled granite hieroglyphics” (Melville 1983, p. 1165), Ishmael transforms the whale into a coded text, which can or could be deciphered, if only one had the right translation manual: “[H]ow may unlettered Ishmael hope to read the awful Chaldae of the Sperm Whale’s brow? I put that brow before you. Read it if you can.” (Melville 1983, p. 1165). With this encouragement, the reader is sent on a mission which the narrator himself has already failed. Right from the novel’s beginning, Ishmael is a survivor of the events he is about to relate, the only one who “did survive the wreck” (Melville 1983, p. 1408) of the fatal ending. The human being gets away with his life and a story to tell: “Call me Ishmael.” (Melville 1983, p. 795). The animal, however, remains both elusive and untranslated. Undeterred, the white whale dives and stays hidden under the untroubled surface of an ocean that bears no mark or writing.

In this light, Moby-Dick could be seen as the exemplification of a structural problem in the relationship between animals and narration. Recent debates in animal studies and ecocriticism have challenged the view of human exceptionalism and stressed the similarities, mutual dependencies, and histories of co-evolution that shape the relationship between humans and animals. As a consequence, agency and other forms of meaningful self-expression are no longer considered as exclusively human capabilities. Kate Rigby, for instance, points out:

[t]he necessity of an ecological enlightenment, in which the nonhuman is resituated as agentic, communicative, and ethically considerable, while human consciousness is recognized as embodied and interconnected with a more-than human world that is neither fully knowable nor entirely controllable.(Rigby 2014, p. 219)

In this context, practices of storytelling have been attributed a particular importance and critics are asking for new, more holistic ways of representation and stylization that would change the view of the animal as the mere witless other of humanity. This approach, however, poses problems of its own that can be put in narratological terms, for, lacking the faculty of speech, animals don’t tell stories in a strict sense. As Ahab remarks in regard to the (dead) sperm whale’s head, “not one syllable is thine!” (Melville 1983, p. 1127). But the symbolic system of human language not only constitutes the material that literature is made out of. In the history of philosophy, throughout its various attempts to establish an essence or unique capability of the human, language use was virtually always identified as marking a distinctive frontier or even “abyss”, as Martin Heidegger puts it, between humans and the realm of nature. From this perspective, the prosaic means of literature could be seen as particularly unfit for any approach to nonhuman animals. To understand them, we have to rely on acts of interpretation and meaning-making, operations that easily transform their subject into an otherwise empty screen for anything we want to project onto it. This highly anthropocentric view of the animal as a kind of allegorical device becomes particularly notable in the case of Moby-Dick. As Melville’s readers are informed, the whale not only provides a wide range of materials, due to its absence of color, the white whale is so polymorphic in its symbolic meaning that it can signify virtually anything, including the very outmost container of this “anything”: “the heartless voids and immensities of the universe” (Melville 1983, p. 1001). However, in order to realize this versatility, its absence of color is first and foremost that of a blank page upon which the human hand inscribes its designs. The whale itself, we are reminded, “has never written a book,” even though its oil might have provided the light for the book’s completion.

If, however, an animal in literature starts to speak or even appropriates the writing materials of its oblivious masters, it is only insofar as it behaves similarly to human beings or, more precisely, mockingly mimics a certain idea of the human. Jonathan Swift’s only too well reasoning Houyhnhms, E.T.A Hoffmann’s writing Tomcat Murr, and Franz Kafka’s Red Peter all question and trouble the very notion of the human whose language they speak so eloquently. Still, these different mappings and transitions of the border between the human and the animal are articulated through the code of human language. As Philip Armstrong puts it:

Of course novelists, scientists and scholars can never actually access, let alone reproduce, what other animals mean on their own terms. Humans can only represent animals’ experience through the mediation of cultural encoding, which inevitably involves a reshaping according to our own intentions, attitudes and preconceptions.(Armstrong 2008, p. 2)

The structure of the problem seems to entail a dilemma, for either the animal is seen as a mute automaton, devoid of speech and all capacities it entails or it becomes animated by a voice that barely disguises its human origin. Instead of arguing in favor of one of the horns, one option in dealing with dilemmas is to refute their validity altogether. One could ask, for instance, if whales, grizzly bears, or seals could ever access, let alone reproduce, what human-animals mean on their own terms. But for all his interest in animals as autonomous narrative instances, it seems that Armstrong reserves the creative activity of “cultural encoding”, and thereby the realm of culture generally, to humans and their language games. Nonetheless, he suggests a kind of reading that tracks down the material traces that animals might have left in artistic forms of representation. Traces that could hint at a nonhuman world as an origin of meaning and subjectivity in its own right:

Hence, in seeking to go beyond the use of animals as mere mirrors for human meaning, our best hope is to ‘locate’ the tracks left by animals in texts, the ways cultural formations are affected by the materiality of animals and their relationship with humans.(Armstrong 2008, p. 3)

To elaborate on this notion of materiality, the following paper will leave the realm of the literary text in a strict sense and focus on two of Werner Herzog’s later documentaries in which the medium of film is brought into close quarters with the physical presence of nonhuman nature: Grizzly Man (2005) and Encounters at the End of the World (2007). In this attempt, the notion of the material will inform the paper’s general perspective. While Ishmael, himself a narrative specksnyder, cuts through layers of whale blubber in order to reach an imaginary kennel, I would like to focus my attention upon all the greasy stuff that is cut away and usually discarded. This implies a more pronounced attention to the material fluxes and exchanges, the melees amongst nonhuman animals, cameras, and humans that are made prominent in Herzog’s later works. My hope is that the specific qualities of film will allow for a different representation of human and nonhuman animals and develop a gaze that is able to reach beyond the anthropocentric confinements of language.

2. “The Ripple of Leaves”: Filming in the Wilderness

Herzog’s relation to nature seems contradictory. While the depiction of sublime, wild and oftentimes hostile landscapes plays a huge part in virtually all of his works from Aguirre to the most recent Into the Inferno, he has distanced himself from sentimental and anthropomorphic appropriations of nature on several occasions. Scattered throughout various interviews, statements and other paratextual forms, his approach to questions of nature and its aesthetic representation is most explicitly and extensively addressed in Grizzly Man from 2005. Grizzly Man retraces the life of Timothy Treadwell who spent 13 summers in Katmai National Park in southern Alaska among wild brown bears, claiming and believing that only he could protect them against poachers and other intruders into an otherwise pristine natural habitat. As it becomes clear during the film, no such threat ultimately existed for the bears. Timothy spent his summers amid a healthy population of brown bears and if there was any imminent danger, it was for the human being. When Treadwell and his partner Amy Huguenard prolonged their stay into the fall of 2003, a season when the bears prepare for hibernation, both were fatally attacked.

What makes such a fascinating figure for Herzog’s film is Treadwell’s role as a passionate amateur filmmaker who shot over 100 h of videotape under challenging conditions. The original videotapes, which constitute the raw material of Herzog’s approach, are not only edited and presented by a narrative voice-over but placed within a complex network of interviews with Timothy’s friends and colleagues, a former girlfriend, his parents, biologists, ecologists, and even the coroner. Some of the difficulties in coming to terms with Grizzly Man stem from this multiperspectival form: It forces the viewer to differentiate between Treadwell as a historical figure, as the director and main character of his own recordings, and, on yet another level, Herzog’s representation of him as a filmic subject and the film’s particular storytelling, which introduces substantial deviations from Treadwell’s viewpoints. While all these different perspectives and layers can be understood as interpretative attempts to explore the possible meaning of Treadwell’s work, their interplay functions as a kaleidoscope or echo-chamber, in which new and unforeseen possibilities of understanding start to proliferate.

Despite his often playful mannerisms, Treadwell does not come across as naïve and shows a keen awareness of the potential threats that he faced every day: Referring to one of the older bears that would attack him only a few days later, he stresses that “[…] these are the bears that on occasion do for survival kill and eat humans. Could only the big old bear possibly kill and eat Timothy Treadwell?” (Grizzly Man 2005, 00:14:53). It might seem puzzling that this awareness never translated into a resolution to leave. Treadwell had a deep trust in his intimate understanding of the animals he lived with for thirteen years, seeing some of them grow up from cubs to full grown carnivores. “I know the language of the bear.” (Grizzly Man 2005, 00:14:27), Treadwell claims, a belief that separates him from the more skeptical voices in the film that question both the existence of such a language and Treadwell’s competence in performing this feat. Against the backdrop of this view of nature as essentially mute, Grizzly Man’s representation of Treadwell is structured by the spatial figure of a fateful transgression. Right at the film’s beginning, Herzog’s narrative voice claims that Treadwell “crossed an invisible borderline” (Grizzly Man 2005, 00:04:15), and other characters appearing in the film vary this pattern of thought only slightly, stating that he crossed an “unspoken boundary” (Grizzly Man 2005, 00:29:13) between humans and bears. One of the most moving, yet disturbing scenes of the footage shows Treadwell hesitantly trying to touch a bear when both of them encounter each other in the liminal region at the shore of a lake (see Figure 1) (Grizzly Man 2005, 00:28:57–00:29:32).

Figure 1.

Treadwell filming himself with a bear.

What are the rhetorical and ideological currents that are at play in Herzog’s narration of Treadwell as a figure of transgression? It is noticeable that, in spite of its designation as an “unspoken boundary”, the film reproduces a strict distinction between animals and humans repeatedly and in quite an audible manner. It is spoken all the time. The apparent need to establish this distance seems to be related to the bear’s status as a carnivore. This could be conceived as too obvious to merit any discussion. Of course I do not want to deny that there can be good and very practical reasons why humans should evade grizzly bears, not least for the latter’s benefit. With reference to the local Alutiiq community that he is both a scholar and a descendant of, Sven Haakanson points out to Herzog that “if you habituate bears to humans, they think that all humans are safe. Where I grew up, they avoid us and we avoid them.” (Grizzly Man 2005, 00:28:54). Yet, I wonder if Herzog’s view of the grizzly bears as “metonyms of wild nature” (Ladino 2009, p. 54), as Jennifer Ladino accurately puts it, does not reiterate a more complex and problematic opposition between human and nonhuman animals on a general level. To illustrate this point, I would like to refer to a seemingly more timid animal that is mentioned only briefly in the film. Every now and then hikers in the Alps are attacked and eventually killed by cows that probably feel the need to protect their calf.1 However, it is rather unlikely that the victims of these bovine encounters could create a “story of human ecstasy” (Grizzly Man 2005, 00:03:55) and be depicted as the sublime yet lamentable trespassers into a “world” of cows. In regard to Grizzly Man it therefore seems important that the bear is not only a wild, undomesticated omnivore that is able to kill, but that it eats and eventually digests the human body as it would do with any other form of meat.

In fact, the bear’s metabolism and its various stages constitute a minor yet recurring background process of Grizzly Man. Treadwell himself is obsessed with the feces of Wendy, one of the bears, and cannot resist touching it with his hands. This fascination with an object that was “just inside of her” (Grizzly Man 2005, 1:06:38) develops a rather uncanny meaning, since Treadwell seems passionately drawn to the final product of a digestive system that he himself is eventually going to be a part of, an aspect that was already made explicit by the pilot Sam Egli earlier in the film. Egli was present after the park service shot and opened the bear that killed Amy Huguenard and Timothy Treadwell. In a restrained tone of disgust he reports that the body of the bear was “cut open, it was full of people, it was full of clothing, it was—we hauled away four garbage bags of people, out of that bear.” (Grizzly Man 2005, 00:17:37). One of the interesting things about disgust is that its cause, effect, and content are all related to the borders of the human body. At first, the sight of a disintegrating human body can be discerned as the essential cause of disgust. At the same time, the disgusted person’s own body and its relation to the spatial environment constitute the site of the feeling itself. As Winfried Menninghaus writes: “The fundamental schema of disgust is the experience of a nearness that is not wanted. An intrusive presence, a smell or taste is spontaneously assessed as contamination and forcibly distanced.” (Menninghaus 2003, p. 1). Therefore, one of the most logical effects of disgust is a sudden expulsion of the interior to the exterior: vomiting. Finally, the act of vomiting makes it clear that disgust is a corporal reaction that overwhelms the human body. In this context, Egli’s slight tone of disgust is given a different ring that concerns the quasi-ontological relationship between animals and the human: The spatial figure of “nearness” and “contamination” that Menninghaus writes about refers to the sight of a human body that is absorbed by the digestive system of a carnivore. Designated as “people”, the human being not only loses its identity as an individual person but as a supposedly exceptional species. It finds itself right in the middle of a food chain that humanity is supposed to be in control of and normally is set apart from. As James Hatley argues, the sheer fact of edibility blurs a strict line between human and animal:

In merely the threat of being eaten, one finds oneself in the situation that the very body that sustains one’s own life suddenly is also the body that is to be ingested, in order that another’s life might be sustained. What was most intimate becomes most strange, and what was most strange becomes most intimate.(Hatley 2004, p. 23)

It seems that exactly this kind of uncanny replacement between inside and outside and its ontological connotation is the object of Egli’s disgust. However, what is so gratifying about Treadwell’s found footage is exactly that it circumvents stereotypical images of the bear as a bleak carnivore and emphasizes forms of behavior that are indicative of a complex social being. Human being and bear are not reduced to the same (edible) corporeality.2 Both life forms resemble each other by virtue of their respective engagement in practices of meaning-making, an aspect that leads me back to the question of animal expressiveness that this essay started with. Treadwell neither had a background in biology nor was he interested in adhering to norms of intellectual or academic rigor. Nevertheless, empirical research on grizzly bears does make use, if carefully, of “culture” as an explanatory term for their behavior. Regarding the question of social relationships and forms of communication among grizzlies G. A. Bradshaw writes:

Bear country is riddled with intricate bear trails and marker trees that serve to convey information in the absence of bear-to-bear physical proximity. These communiqués create an invisible web of messages that brings coherence to a physically dispersed community. Bears’ psychology is thus uniquely suited to their habitat. We might then envision bear collective life as a dynamic network of relationships that is shaped by resources and terrain, much of which […] is hidden from human eyes.(Bradshaw 2017, p. 78)

Bradshaw invites us to imagine the bear’s landscape as replete and entrenched with meaning, maybe similar to a network of hiking trails whose system of signposts is constantly modified and rewritten by each individual hiker. Her description sheds light on a rich material semiotics that certainly differs from human sign systems, yet is no less real. Unsurprisingly, this interpretation of the bear as an expressive being would be fundamentally at odds with Herzog’s view on nature as dominated by “chaos, hostility and murder” (Grizzly Man 2005, 01:08:09). Showing the face of the bear that probably killed Treadwell in close up, Herzog’s voice-over scorns at the rhetorical means of prosopopoeia:

And what haunts me is that in all the faces of all the bears that Treadwell ever filmed, I discover no kinship, no understanding, no mercy. I see only the overwhelming indifference of nature. To me there is no such thing as the secret world of the bears and this blank stare speaks only of a half bored interest in food, but for Timothy Treadwell this bear was a friend, a savior.(Grizzly Man 2005, 01:32:51)

Prosopopoeia is typically considered as a sub-form of metaphor and is defined as the attribution of human features to animals, plants or inanimate objects. For Herzog, no such metaphorical transaction of expressive features to the natural world, be it animal or plant, seems legitimate. The animal is the absence of all meaning. For if the “blank stare” is able to speak, then only to indicate its own muteness and “indifference”. As I pointed out with reference to research by Bradshaw, this assessment of the animal as devoid of any meaning or expression would seem doubtful from an ethological perspective. But even within Herzog’s own work, the marginalization of the animal by reference to its lack of expression is less evident than it might seem. To elaborate on this point, the remaining part of this section will consider the role of the camera in both Treadwell’s and Herzog’s work.

As Herzog suggests, Treadwell held a fatal misconception. He did not realize that, instead of waiting for a big, furry, moving automaton to accept his tedious attempts at courtship, he could have pursued a probably less thrilling yet more dependable relationship: “Beyond his posings,” Herzog states, “the camera was his omnipresent companion.” (Grizzly Man 2005, 00:39:05). This notion of companionship with the camera also has consequences for the question of genre. According to Herzog, Treadwell’s footage constitutes “something way beyond a wildlife film” (Grizzly Man 2005, 00:37:36). In Herzog’s terms, however, this “beyond” implies nothing but the irrelevance of “wildlife” altogether:3

Treadwell is gone. The argument how wrong or how right he was disappears into a distance, into a fog. What remains is his footage. And while we watch the animals in their joys of being in their grace and ferociousness, a thought becomes more and more clear: that it is not so much a look at wild nature as it is an insight into ourselves, into our nature.(Grizzly Man 2005, 01:35:42)

While refusing an anthropomorphized view of the environment as overtly naive, Herzog refers to the notion of “wild nature” as the metaphorical vehicle for Treadwell’s excessive inner states. Referring to the ragged surface of a glacier that is located some miles from Timothy’s camp in the Alaskan backcountry, Herzog concludes “that this landscape in turmoil is a metaphor of his soul” (Grizzly Man 2005, 00:57:42). Apart from its function as the material of signification, nature remains insignificant, without features. Both the slowly moving glacier and the forceful mammal might have a complex history of its own, its own story to tell, but for the moment this aspect remains in the background. It strikes me that this metaphorical conception of nature as designating human phenomena is not so different to the anthropomorphic view that Herzog rejects. Similar to Ishmael’s projection of writing onto the white surface of Moby Dick’s rugged skin, Herzog attributes any desired meaning to nature just as he does to Treadwell. At this point, a historical qualification seems to be warranted: When Herzog links the human environment that Treadwell is trying to escape from with “the same civilization that cast Thoreau out of Walden and John Muir into the wild” (Grizzly Man 2005, 01:22:20), this historical analogy to American Transcendentalism seems equally true for Herzog’s own conception of nature. When Ralph Waldo Emerson analyses the relationship between language and the tangible environment in his essay Nature from 1853, he refers to the structure of metaphor:

We are like travelers using the cinders of a volcano to roast their eggs. Whilst we see that it always stands ready to clothe what we would say, we cannot avoid the question whether the characters are significant of themselves. Have mountains, and waves, and skies no significance but what we consciously give them, when we employ them as emblems of our thought? Parts of speech are metaphors, because the whole of nature is a metaphor of the human mind.(Emerson 1983, p. 24)

How, Emerson asks, can nature have significance apart from our language games and practices of interpretation? This question that “we cannot avoid,” cannot be answered either, or so it seems. In a strange form of distraction, Emerson circles back to the assumption whose validity he wanted to contest: “the whole of nature is a metaphor”.

But what the Transcendentalists could not have yet considered and Herzog cannot get around is the technical make-up of the camera and its relationship to the natural environment. Similar to Herzog’s own tendency of prolonging scenes to a point when his interviewees visibly start feeling awkward and uneasy, Treadwell’s material is most interesting to Herzog at exactly those transitory moments when a scene is already terminated, but the camera is still running and thereby creates a kind of surplus: “In his action movie mode, Treadwell probably did not realize that seemingly empty moments had a strange beauty. Sometimes images develop their own life, their own mysterious stardom” (Grizzly Man 2005, 00:38:55). Here, Herzog’s voice-over refers to a view of bushes and grass that are stirred by wind and rain. In an almost iconological way, this image recalls Siegfried Kracauer’s Theory of Film. In a chapter entitled “A whole with a purpose,” he writes:

[F]or a film built from elements whose only raison d’être consists in implementing the (pre-established) “idea conception” at the core of the whole runs counter to the spirit of a medium privileged to capture “the ripple of leaves in the wind”.(Kracauer 1960, pp. 221–22)

Emerson regards “the whole of nature” indeed as “a whole with a purpose,” since it provides humans with the material to clothe their words and thoughts. By contrast, the technique of film introduces a different perspective. For Kracauer, the medium’s unique potential lies in its ability to record the miniscule and seemingly insignificant, the purposeless manifoldness of the physical world that lies beyond the limits of narrative schemes and grand ideological frameworks. In this aspect, it differs fundamentally both from the genre of the novel and the drama, in which, according to Kracauer, every single element plays an integral part in the process of storytelling. In a similar way, Herzog seems to imply that it is exactly when the filmic stylization and well-wrought narration give way to unplanned moments of emptiness and quietude that not only Treadwell’s recordings, but also the medium of film fulfill their own potential: An ephemeral grassy landscape in the middle of nowhere set in motion by wind and rain; foxes that surprisingly enter a scene in which Treadwell just completed his practiced monologue with the camera. The film offers the possibility of an excess that exceeds human narration. As Herzog puts it: “now the scene seems to be over but as a filmmaker sometimes things fall into your lap, which you couldn’t expect, never even dream of.” (Grizzly Man 2005, 00:24:22).

This is one of the decisive aspects of Treadwell’s raw footage: Installed on a tripod, the camera constitutes an ambiguous, dynamic space that is habituated both by human and nonhuman agents. Treadwell’s footage shows him, brown bears, and other animals within the same frame, sharing the same living space and at times, these fleeting moments constitute an almost geometrical choreography, a cycle of different life forms, as it can be seen in Figure 2. Here, Treadwell appears less as a transgressive intruder into a hostile realm of wild nature than as a part of an assemblage. This closeness does not necessarily imply a relationship of unconditional harmony. In the beginning of Grizzly Man there is an encounter with a bear that slowly trots towards the camera and eventually gets so close to it that the picture becomes blurred. Something is going wrong, but this becomes manifest only by the fact that Timothy suddenly loses his balance, gasps and almost drops the hand-held camera (Grizzly Man 2005, 00:04:34–00:04:42). In the sudden interruption, the seemingly transparent medium of filmic representation is stressed and thus becomes located as a part of the natural world that it tries to depict. As I would like to suggest, this kind of physical exposure slightly alters the image of nonhuman nature. In the immediate contact with the camera the animal leaves traces on the film and thus gains an autonomous, unruly presence, a possibly disturbing agency that counteracts any attempt to read it as a mere metaphor for cultural or psychological phenomena. Furthermore, this precarious interconnectedness also concerns the question of the film’s genre. Principally, though for different reasons, Herzog is right when he claims that Treadwell’s footage is “beyond a wildlife film”. In the realistic aesthetics of the wildlife film, the camera seems to imitate a disembodied gaze with almost magical abilities: itself invisible, it sees everything and, while remaining distant, it discloses the natural world in every detail. This way, the view emerges of a self-contained, transcendent environment that is undisturbed by the presence of humans. However, as William Cronon has pointed out, when nature is defined by the absence of humans, and humans, accordingly, by the absence of nature, the idea of a fundamental difference between both realms is reinforced.4 This view of the wilderness as sublime and untouched has problematic effects. Cronon writes that:

if by definition wilderness leaves no place for human beings, save perhaps as contemplative sojourners enjoying their leisurely reverie in God’s natural cathedral—then also by definition it can offer no solution to the environmental and other problems that confront us. To the extent that we celebrate wilderness as the measure with which we judge civilization, we reproduce the dualism that sets humanity and nature at opposite poles.(Cronon 1995, p. 81)

Figure 2.

Bear, foxes, Timothy Treadwell.

Granted, Treadwell’s self image was constituted by the idea of (masculine) solitude and the absence of other human beings in a landscape that he refers to as the “sanctuary” (Grizzly Man 2005, 00:09:49). By carrying a very situated and corporeal camera around with him, however, he creates an aesthetic form that disturbs the ideological view of an external realm of nature uncontaminated by human beings.

How does this analysis relate to my initial question about the relationship between animal expressiveness and human narration? When Herzog emphasizes how Treadwell’s images are able to “develop their own life, their own mysterious stardom” (Grizzly Man 2005, 00:38:55), he refers to a potentiality and vivacity of reality that lies beyond the control of the person that operates the camera. Drawing on Kracauer’s considerations regarding ideology and film I would argue that the filmic gaze suspends a solely human perspective and narration and is able to open up new and quite lively possibilities of perception. When Treadwell’s monologue with the camera is interrupted and he is shown amid the presence of bear, fox, and cub, the possibilities of different, non-human worlds can become accessible. Just as the images of the Alaskan grass landscapes can “develop their own life”, they might give presence to differing forms of meaning-making. I think, for instance, of the semiotic network of trails and marked trees that configure the bear’s material environment and thereby constitute a storied place as Thom van Dooren uses the term. The adjective “storied” refers to “the way in which places are interwoven with and embedded in broader histories and systems of meaning through ongoing, embodied, and inter-subjective practices of ‘place making‘” (van Dooren 2014, p. 67). These practices of appropriation are not unique to human beings. Corresponding to its “invisibility” for untrained human perception, the system of trails and signs is part of a grass landscape that is only “seemingly empty”, as Herzog puts it. Treadwell’s footage therefore could be seen as the engagement with a particular place and how it is shaped and inhabited both by human and nonhuman beings. However, and as the following section will argue, this image of an entanglement across the borders of seemingly different ontological realms is not necessarily limited to a notion of place, understood as a scene of dwelling. It can also be taken a step further and expanded to a global perspective.

3. Whiteout

Since Treadwell spent much of his time in Alaska alone, he oftentimes filmed himself talking to the camera or even filmed himself filming the environment. Grizzly Man, one could argue, is not least a meta-fictional film about the act of filming and bringing a camera to a place that is called the wilderness. Indeed, the triadic arrangement between human perception, technical recording device, and nonhuman nature has become a constant feature in Herzog’s later work as a filmmaker, most notably in Encounters at the End of the World (2007), shot in Antarctica. The film title’s plural form seems to be well chosen. In a rather loose sequence of appearances, Encounters shows the people that work and live in the surrounding of McMurdo Station, a United States research center on Ross Island, situated close to the mainland of Antarctica, that was established in 1955. Described by Herzog both as an “ugly mining town” (Encounters at the End of the World 2008, 00:09:16) and as coming “closest to what a future space settlement would look like” (Encounters at the End of the World 2008, 01:09:46), McMurdo is introduced as a place that oscillates between the banal and the unreal. Its inhabitants are ascribed an “intention to jump the margin of the map” (Encounters at the End of the World 2008, 00:11:23), as philosopher and forklift driver Stefan Pashov puts it at the film’s beginning. Indeed, the quirky microcosm of mechanics, biologists, plumbers, glaciologists, volcanologists, physicists, and a seemingly somewhat out-of-place linguist seems to merge into the dreamlike. When Herzog interviews them in their respective working environments and fields of study, they all seem to struggle with phenomena of nature that exceed the means of a purely empirical approach and demand indirect means of representation such as the dream—or the film they are about to take a part in.

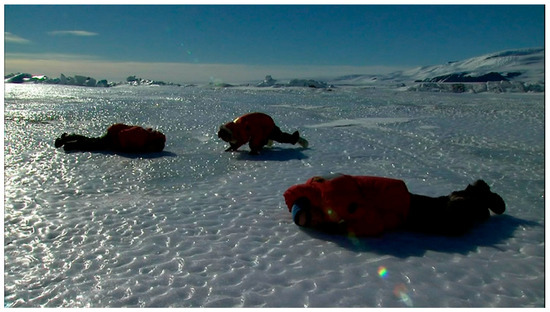

Therefore Encounters does more than show the sometimes peculiar proceedings of a remote research center within a seemingly barren and lifeless icescape. The film displays a particular curiosity for different ways of interaction and confrontation between humans and nature, including various animals that range from penguins, seals, starfish, and underwater crustaceans all the way to single-cell organisms. Furthermore, the film engages with complex natural systems and their inherent, stretched temporal scale such as drifting icebergs, volcanism, climate, and the impact that human civilization has on them. This way, a holistic view evolves of humans as entangled within a complex multitude of various life forms and material forces whose dynamic seems intractable. This depiction of nature as animate and elusive is emphasized by a distinctly self-reflexive form of representation that puts the camera, as it is used both in scientific and artistic contexts, into physical proximity with a more-than-human world.5 The effect of this aesthetic is not only a defamiliarized image of the environment, but also of human observers and their spatial position in regard to nature. All inhabitants of McMurdo are required to participate in a two-day survival school, part of which is the “bucket-head whiteout scenario” that tries to imitate the meteorological conditions of a whiteout. In situations of severe snowfall or fog, conditions of visibility can be blurred to such an extent that any spatial orientation in regard to the corporeal outline of objects and the horizon becomes impossible; an experience that is understandably described as disconcerting and frightening. With some amusement, Encounters shows a hopelessly disoriented training group that gradually loses any orientation and is neither able to reach its supposed destination nor its point of departure (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The “bucket-head whiteout scenario”.

In other words, “whiteout” means the loss of one’s self; a collapse between perceiving center and outer environment. At the same time “whiteout” is the name of a white correction fluid used to erase writing. A thick liquid, it blurs the borders between the written letter and its formless “environment”, the blank page. In the previous Section 1 argued that Grizzly Man creates a lively space that is inhabited both by human and nonhuman life forms. As the following part of this paper suggests, Encounters at the End of the World both enlarges and intensifies this image of entanglement, as it situates human beings among the fluxes of various interacting ecosystems, the sum of which seems to constitute the earth system. In this whirl of various forces, Herzog’s filmic approach to Antarctica creates the disorienting conditions of the whiteout-scenario in which the line between humans and their so called nonhuman environment starts to dissolve.

On its surface level, Antarctica is a quiet place. It is so quiet that, as the physiologist Regina Eiser remarks in Encounters, you can hear the sound of your own heart beating. This silence also enables an increased awareness for the sounds and voices that stem from underneath the ostensibly solid ground of the frozen Ross Sea, where seals swim and hunt for prey. The underwater soundscape is given extensive attention in the film, and in the next scene one of Eiser’s colleagues euphorically describes the “chucks and the whistles and the booms […] which make you realize that there is a whole world underneath you” (Encounters at the End of the World 2008, 00:31:05). While underwater recordings of seals are playing, the biologists are seen lying down and putting their ears close to the ice—a scene that lasts over a minute within the film (Encounters at the End of the World 2008, 00:31:17–00:32:27).

This rather uncomfortable tableau vivant manifests a literal freeze-frame of the human body (see Figure 4). The temporal continuity of the film is interrupted, the three figures are arrested in their movement and thus seem to embody the very act of attentive listening to the calls of the seals. The ice above the Ross Sea turns into the vast membrane of a loudspeaker, from which the sounds of a foreign and utterly strange world right underneath one’s feet resound. Just like bears, seals are predators. However, they are depicted sinking elegantly into the deep like gentle and peaceful torpedoes. Eiser compares their calls to the music of Pink Floyd or even to a sound that originates rather from outer space than from organic nature.

Figure 4.

Nutrition physiologists listening to seals.

More than anything else, the ensuing moment of strangeness seems to be the common denominator that keeps the film’s different representations of animals together. This is particularly vivid when Encounters turns to another being that lives at the intersection between water and the mainland: the penguin. The engagement with this particular animal, however, is loaded with symbolic meaning since it also works as a commentary on the contemporary filmic representation of Antarctica. When, right at the beginning of Encounters, Herzog states that “I would not come up with another film about penguins” (Encounters at the End of the World 2008, 00:02:36), this is to be understood as a quite forward pun on Luc Jaqcuet’s March of the Penguins from 2005. Jaqcuet depicts the life and reproductive cycle of the emperor penguin within a sublime and untouched ice landscape. Although this vision of Antarctica does not show any trace of human presence, including the film team, for some this absence seemed conspicuous. As critics have argued, March is about the very beings that are absent: humans. Framed by the sympathetic narrative voice of Morgan Freeman, the heartwarming story about the hardship and toil that penguins go through in bringing up their offspring was read as a stand-in for the nuclear family that makes up its main audience. Presented as a timeless and eternal cycle of life, it naturalizes a certain ideology of sexuality and society. Apart from Herzog’s tendency towards self stylisation, his representation of the penguins differs indeed from Jaqcuet’s “story […] about love.” (March of the Penguins 2005, 00:03:18).6 At first, when Herzog interviews the marine ecologist David Ainley in front of the object of his studies, a colony of penguins that he has been observing for years, the scene is reminiscent of the conventions of a wildlife film and its epistemological hierarchy. Ainley finds himself on a slightly elevated position from which the colony below can be observed. Herzog gently but perseveringly tries to undercut this frame and baffle the taciturn Ainley with an array of rather unusual questions. Asked about the possibility of insanity within the animal world, Ainley eventually points out that sometimes they “do become disoriented” (Encounters at the End of the World 2008, 01:13:40) and after a cut the next scene shows a penguin stopping on the route between its colony and the feeding ground at the open sea and suddenly heading toward a mountain landscape in the distance, a place where it will have no chance to sustain itself. No explanation for this behavior is given; it remains incomprehensible. However, when the penguin is described as “disoriented”, he becomes in fact quite similar to the humans that lose any orientation in the so called bucket-head whiteout scenario and whom Herzog describes as “drift[ing] completely off course“ (Encounters at the End of the World 2008, 00:25:06). In other words, within the logic of Encounters there is no presupposed stable human perspective from which the actions of animals could be easily discarded as lacking expression or reason. While there is an apparent need to paint human physiognomies on the white bucket-heads, as seen in Figure 3, they are less expressive than the bear’s alleged “blank stare”. The structure of “whiteout” I am trying to describe is a blurring of distinct lines between inside and outside or even a form of reversal. While the communicative exchange among seals constitutes a “whole world” of signification, human beings seem to have lost a clear perspective.

This gradual dismantling between humans and their “environment” is intensified as Herzog quite explicitly considers the impact of human civilization on the seemingly timeless landscapes that he is filming and thus extends his approach to the realm of non-organic nature. In this context the introduction of the glaciologist Douglas MacAyeal is of particular importance since it begins right away with the account of a dream in which the sleeping scholar finds himself on top of his subject matter, the gigantic iceberg B15:

At night, lying in my bed here at McMurdo, I am again walking across the top of B15. Might as well be on a piece of the South Pole, but yet, I am actually adrift in the ocean, a vagabond drifting in the ocean and below my feet […] I can feel the rumble of the iceberg, I can feel the change, the cry of the iceberg, as it’s screeching and as it’s bouncing off the seabed, as it’s steering the ocean currents, as it’s beginning to move north, I can feel that sound coming up through the bottoms of my feet and telling me that this iceberg is coming north.(Encounters at the End of the World 2008, 00:13:15)

MacAyeal’s recurring dream is about a primordial awakening. While he is sleeping, the iceberg transforms itself into a living being that moves its weary limbs and expresses its slowly increasing vigor in a series of sounds and calls that find their way from the ice into the human ear. As it becomes clear in the following scenes, this dream presents a means of understanding in its own right, with its own epistemological status. As MacAyeal points out, the heroic period of Antarctic exploration, shaped by figures like Amundsen, Scott and Shakleton, commonly conceived of Antarctica as “a static, monolithic environment” (Encounters at the End of the World 2008, 00:17:05). Understood as the mere scenery for the drama of reaching the South Pole, an endeavor fueled by nationalistic pride and colonial striving, the unmarked ice landscape functioned as a blank field on which the human was able to inscribe its designs and ideology. In this view, Antarctica appears as a featureless object that can be crossed and thereby symbolically conquered. Its structure thereby bears similarities to the whiteness of the whale, that can be used to “symbolize whatever grand or gracious thing” (Melville 1983, p. 997), and the bear’s “blank stare” that functions in a similar way.

As I argued at the beginning of this section, whiteout erases human writing. In the sped-up sequence of satellite images that MacAyeal points at, the environment of Antarctica is not seen as a mere object of signification but as an agent. Of course the nature of climatic changes manifests such a large temporal and spatial scale that it cannot be perceived from a singular point in time and space. Almost invisible in real time, the slow changes of climate and the movement of the icebergs need forms and media of visualization, such as the accelerated rate of the satellite images. Seen from this unusual perspective, Antarctica becomes increasingly defamiliarized and uncanny. The frozen and barren landscape does not present itself as a stable and unchanging entity but as a complex and living system in which human beings are not the exclusive origin of agency and meaning. The iceberg’s movements become animated and reality itself has become dreamlike:

Now our comfortable thought about Antarctica is over,” Douglas continues. “Now we’re seeing it as a living being, it’s dynamic, it’s producing change. Change that it’s broadcasting to the rest of the world. Possibly in response to what the world is broadcasting down to Antarctica.(Encounters at the End of the World 2008, 00:17:15)

Here, Antarctica is depicted in a reciprocal, productive interplay of various subsystems such as climate, cryosphere, ocean currents, and the landmasses. The earth seems to display a functional interaction and thus exhibits similarities to Donna Haraway’s terms of sympoiesis or holobiont. In continuity of the model of symbiosis as a mutual dependency of different life forms, sympoiesis understands relationships as the basic and irreducible structure of natural phenomena. Unlike symbiosis as a form of mutual dependency or advantage, the notion of poeisis emphasizes the productive and constantly evolving aspect of such a relationship.7 Haraway writes:

I use holobiont to mean symbiotic assemblages, at whatever scale of space and time, which are more like knots of diverse intra-active relatings in dynamic complex systems, than like the entities of a biology made up of preexisting bounded units (genes, cells, organisms, etc.).(Haraway 2016, p. 60)

However, Haraway does not limit her model to a distant realm called nature or the environment but understands human agents as an integral part of sympoietic processes, a fact that is made prominent by her use of the term “natureculture”. In fact, a surprisingly similar view is expressed by MacAyeal’s remarks on Antarctica that he describes as “a living being” that sends and receives data to and from “the rest of the world”. What is so remarkable about his statement is not only the changed understanding of nature as an active agent, but also its articulation in terms of a radio or television transmission. While Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo steadfastly blared his opera recording of Enrico Caruso into the jungle, this unidirectional relation has changed into the rhetorical structure of a chiasmus. The iceberg and its stirrings not only affect the complex interplay of ocean currents, water temperatures, and the meteorological patterns of the atmosphere, but its voice also affects the receiving set of Herzog’s film. This emphasis on the technical media of recording is telling because ultimately Encounters is, again, also a film about filming and how the medium of film is related to other media used in the depiction and understanding of the environment. When Herzog accompanies a group of volcanologists to Mount Erebus, an active volcano on Ross Island that reaches an altitude of almost 4000 m, the crater is completely covered in clouds and fog. But apart from the scientists that heave their material through the unreal scenery of fog, snow and rocks, particular attention is paid to the cameras, microphones and other technical devices that are installed at the rim of the crater and point into the abyss. Similar to Timothy Treadwell who filmed himself filming the Alaskan wilderness, Herzog directs his camera at cameras that are designed to monitor the environment in Antarctica (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

A camera pointed into the crater of Mount Erebus.

This depiction of the camera enshrouded in mist and fog alludes to the whiteout scenario that Encounters introduces at its beginning but it can also be read as a commentary on the general position of the human observer towards nature as a subject of study. Throughout the film, the viewer watches ecologists listening to seals, studying penguins and other sea animals, glaciologists measuring the movements of the allegedly eternal ice, and geologists reconstructing the history of volcanic activity. In Herzog’s take on these configurations, the attempt at translating natural phenomena into a human sign system is never entirely successful or complete; humans are not placed in a privileged and distanced epistemic or aesthetic position from which they can comprehend and contemplate the sublime wonders of nature.8 Just as the camera is enshrouded in mist, humans and their natural environment become so entangled with each other that the presupposition of a center loses its meaning.

This study began with the question of how animals and, on a larger scale, nonhuman nature, could become present as independent sources of agency and narrative energy, maybe even as narrative instances in their own right, with their own perspectives and their own story to tell. Since Herzog is not relying on animation, the films in question do not reverse the hierarchy between narrating human and narrated animal in a literal sense—a structure I outlined in the beginning through the relationship between Ishmael and the white whale. Herzog does not try to stage an imaginary entrance into the consciousness or subjective perspective of animals, not to speak of inorganic forces. Nevertheless, both Grizzly Man and Encounters at the End of the World focus on a range of various animals like bears, foxes, seals, penguins and sea animals, and they consider larger natural phenomena such as climatic and geological processes that develop their own irreducible physical presence and cannot be considered as mere background phenomena for the story of human individuals. As has become clear at several points of the analysis, this conception of nature as an active and autonomous force is not necessarily a comforting notion. Herzog’s gaze shows a human body that is entangled with dynamic nonhuman agencies, and both films linger on resulting moments of incomprehension, disorientation, and physical danger.

The lack of distance between human and nonhuman agents emerges also on a medial level. Both films explore forms of representation that indeed reach “beyond a wildlife film”, as Herzog puts it in regard to Timothy Treadwell’s work. As I pointed out in my analysis of Grizzly Man, the conventions of the wildlife film tend to obscure the physical presence of the camera and the mere fact of filmic representation remains mostly hidden; a strategy often associated with the rhetoric of unmediated realism.9 By contrast, Herzog’s gaze is not a disembodied view from nowhere. Grizzly Man and Encounters employ a purposefully self-reflexive way of representation and go to great lengths to emphasize and display the different technological media that are used to record and visualize their respective environments: Treadwell’s video recordings of the brown bears, the soundtrack of the hunting and swimming seals, furthermore the sped-up depiction of floating icebergs in fast-motion, and the video recordings of the volcanic crater of Mount Erebus. Finally, it is also Herzog’s own camera and his way of figuration that are alluded to by the various cameras that appear on the screen. In a meta-hermeneutical meditation on human’s epistemic and medial stance, both Grizzly Man and Encounters at the End of the World take a step back and ask about the different ways of narration and representation by means of which the human is trying to make sense of nature. The effect is a defamiliarized image of the human observer and his spatial position in regard to nature but also of nonhuman animals. As a common feature of the various animals that have been introduced in this essay, they all seem to disturb or interrupt human forms of narrative signification and use the resulting gaps in order take on an autonomous and expressive status. While Melville’s white whale eludes the attempts of representation or translation, Treadwell’s camera shows human and nonhuman animals in a dynamic relationship that is not controlled by the human operator. In a similar way, yet with a more global perspective, Encounters situates the human in a vast system of natural processes, a situation I brought into connection with the semantic ambiguity of the whiteout. Representing both the erasure of human writing and the dissolution of corporeal lines in meteorological conditions of severe snow and fog, it can also be understood as an aesthetic form that attempts to leave behind the limits of an anthropocentric perspective on nonhuman nature. In my view, Werner Herzog’s work can be understood as walking in this whiteout.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Armbruster, Karla. 1998. Creating the World We Must Save: The Paradox of Nature Television Documentaries. In Writing the Environment: Ecocriticism and Literature. Edited by Richard Kerridge and Neil Sammels. London and New York: Zed Books, pp. 218–38. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, Philip. 2008. What Animals Mean in the Fiction of Modernity. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ayoub, Nadine. 2014. Autriche—Des “Vaches-Tueuses” Dans Les Alpages. Arte.tv. September 10. Available online: https://info.arte.tv/fr/autriche-des-vaches-tueuses-dans-les-alpages (accessed on 9 November 2017).

- Bradshaw, Gay A. 2017. Carnivore Minds. Who These Fearsome Animals Really Are. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, Bob, and Nickie Charles. 2013. Animals, Agency and Resistance. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 43: 322–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chris, Cynthia. 2006. Watching Wildlife. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cronon, William. 1995. The Trouble with Wilderness; or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature. In Uncommon Ground: Toward Reinventing Nature. Edited by William Cronon. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., pp. 69–90. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, Ralph Waldo. 1983. Essays and Lectures. Edited by Joel Porte. New York: The Library of America. [Google Scholar]

- Encounters at the End of the World, 2008. Werner Herzog, director. New York: Discovery/THINKfilm.

- Goebel, James. 2016. “Uncanny Meat”. Caliban. French Journal for English Studies 55: 170–90. [Google Scholar]

- Grizzly Man, 2005. Werner Herzog, director. Santa Monica: Lions Gate Entertainment.

- Haraway, Donna. 2016. Staying With the Trouble. Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hatley, James. 2004. The Uncanny Goodness of being Edible to Bears. In Rethinking Nature: Essays in Environmental Philosophy. Edited by Bruce Foltz and Robert Frodeman. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, pp. 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Laurie. 2012. Werner Herzog’s Romantic Spaces. In A Companion to Werner Herzog. Edited by Brad Prager. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 510–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kracauer, Siegfried. 1960. Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ladino, Jennifer K. 2009. For the Love of Nature: Documenting Life, Death, and Animality in Grizzly Man and March of the Penguins. Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature & Environment 16: 53–90. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- March of the Penguins, 2005. Luc Jaquet, director. Burbank: Warner Independent Pictures.

- McGavin, Laura. 2013. Terra Incognita. Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature & Environment 20: 52–70. [Google Scholar]

- Melville, Herman. 1983. Moby-Dick, or, the Whale. Edited by G. Thomas Tanselle. New York: The Library of America. [Google Scholar]

- Menninghaus, Winfried. 2003. Disgust: Theory and History of a Strong Sensation. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prager, Brad. 2007. The Cinema of Werner Herzog: Aesthetic Ecstasy and Truth. London and New York: Wallflower Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rigby, Kate. 2014. Confronting Catastrophe: Ecocriticism in a Warming World. In The Cambridge Companion to Literature and the Environment. Edited by Louise Westling. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 212–25. [Google Scholar]

- Steingröver, Reinhild. 2012. Encountering Werner Herzog at the End of the World. In A Companion to Werner Herzog. Edited by Brad Prager. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 466–84. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dooren, Thom. 2014. Flight Ways: Life at the Edge of Extinction. New York: Colombia University Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | See for instance Nadine Ayoub (Ayoub 2014). “Autriche—des “vaches tueuses” dans les alpages”. Arte.tv, 10.09.2014. Available online: https://info.arte.tv/fr/autriche-des-vaches-tueuses-dans-les-alpages. |

| 2 | In his reading of Grizzly Man, James Goebel reaches a similar conclusion: “The “human” is no longer effectively or definitively marked off from the rest of the material world, but is constituted and de-constituted by it: animal, vegetable, and human occupy a shared plane of creatureliness, zones of exchange that attest to their porosity, openness, and vulnerability.” See James Goebel. “Uncanny Meat”. Caliban (Goebel 2016, p. 181). I try to reach beyond this interpretation in stressing the dynamic and lively aspects in this relationship. |

| 3 | On several occasions, Herzog described his use of landscapes as externalized signs for inner visions, a transaction that critics frequently trace to German Romanticism: “For me a true landscape is not just a representation of a desert or a forest. It shows an inner state of mind, literally inner landscapes, and it is the human soul that is visible through the landscapes presented in my films.” Quoted in: Laurie Johnson: “Werner Herzog’s Romantic Spaces” A Companion to Werner Herzog, edited by Brad Prager (Johnson 2012, p. 511). See also Brad Prager. The Cinema of Werner Herzog: Aesthetic Ecstasy and Truth (Prager 2007), especially chapter 3 “Mountains and Fog.” |

| 4 | With regard to the aesthetics of nature documentaries Karla Armbruster makes a similar point: “They [nature documentaries] can also erase difference within nature by constructing it as a place without room for human beings, ultimately distancing humans from the non-human nature with which they are biologically and perceptually interconnected, and reinforcing the dominant cultural ideologies responsible for environmental degradation.” See Karla Armbruster. “Creating the World We Must Save: The Paradox of Nature Television Documentaries.” In: Writing the Environment: Ecocriticism and Literature, edited by Richard Kerridge and Neil Sammels (Armbruster 1998, p. 221). |

| 5 | In this regard, I strongly disagree with readings that deny the relevance of nature for Herzog’s Encounters, such as Reinhild Steingröver, who claims “that ultimately the subject of Herzog’s nature films is not nature.” See Reinhild Steingröver, “Encountering Werner Herzog at the End of the World.” A Companion to Werner Herzog, edited by Brad Prager (Steingröver 2012, p. 467). |

| 6 | As Jennifer Ladino describes the role of nature in March of the Penguins: “A stunningly beautiful Antarctic landscape provides the backdrop for the film’s anthropomorphic tale of tradition, stability, and continuity. Morgan Freeman narrates the penguins’ journey in terms that are alternately serious and humorous, but always pacifying and grandfatherly.” See Jennifer K. Ladino. “For the Love of Nature: Documenting Life, Death, and Animality in Grizzly Man and March of the Penguins.”(Ladino 2009, p. 54). |

| 7 | Bruno Latour, among other theorists, has broadened the notion of agency so that it includes nonhuman animals, entities and processes. See for instance Bruno Latour (Latour 2005). Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. This conceptualization of agency does not necessarily entail the attributes of self-consciousness, free will, or reasoning, but constitutes rather a deflated account of agency that does not presuppose intentionality. As a consequence, his position has become the object of criticism. For instance, Bob Carter and Nickie Charles point out that his model of nonhuman agency deludes the notion of agency to a point where it starts becoming useless: “since every thing has agency, and agency is the ability to have an effect, we arrive at the banal conclusion that everything affects everything else in some way or another“. See Bob Carter and Nickie Charles. “Animals, Agency and Resistance.” (Carter and Charles 2013, p. 328) This is a fair point to make. In the context of this paper I cautiously use the term of agency with regard to natural processes in order to emphasize their relevance and dynamics with regard to human beings. |

| 8 | In a similar way, Laura McGavin reads Encounters as a “nonanthropocentric vision of Antarctica as a complexly alive environment where single-celled organisms, Wedel seals, forklift operators, subatomic particles, PhD dropouts, and volcanic magma actively intermingle.” Laura McGavin. “Terra Incognita.” Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature & Environment (McGavin 2013, p. 53). However, McGavin seems less interested in the various media of recording and representation that Herzog portrays in Encounters. |

| 9 | See Cynthia Chris. Watching Wildlife (Chris 2006, p. 71): “The preference for unpeopled landscapes also bolsters an implicitly positivist belief in the veracity of direct observation, that is, in the camera’s capacity to represent reality. […] In other words, rather than relationships, conflictual or otherwise, between natural environment and human society, the strategy of minimizing human presence in wildlife films seems to invite viewers to forget that their view on nature is mediated, even as the very act of nature spectatorship underscores its distance and unfamiliarity.” |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).