Proto-Acting as a New Concept: Personal Mimicry and the Origins of Role Playing

Abstract

:1. Introduction

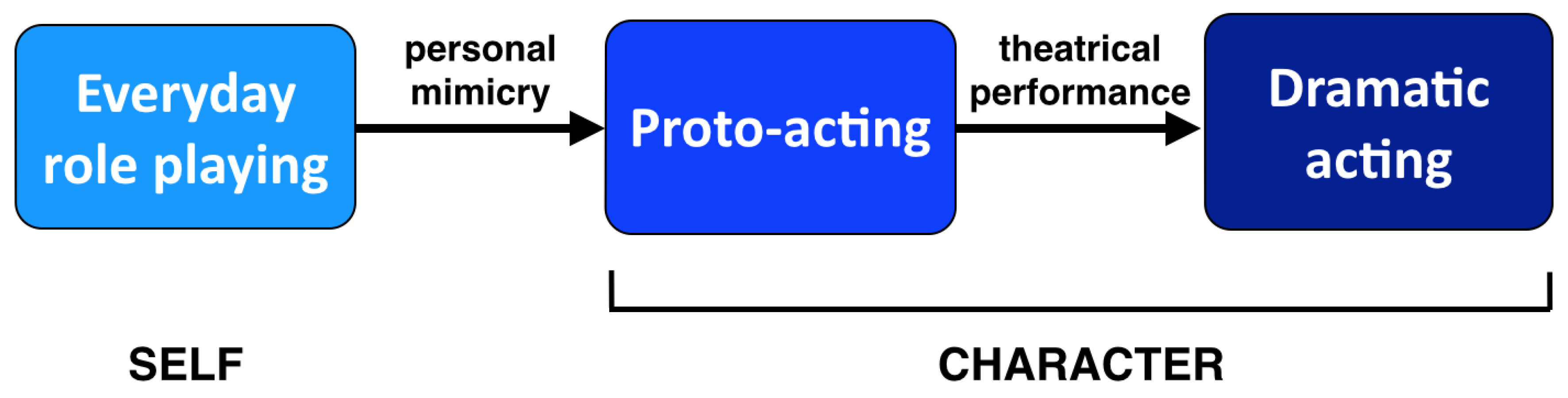

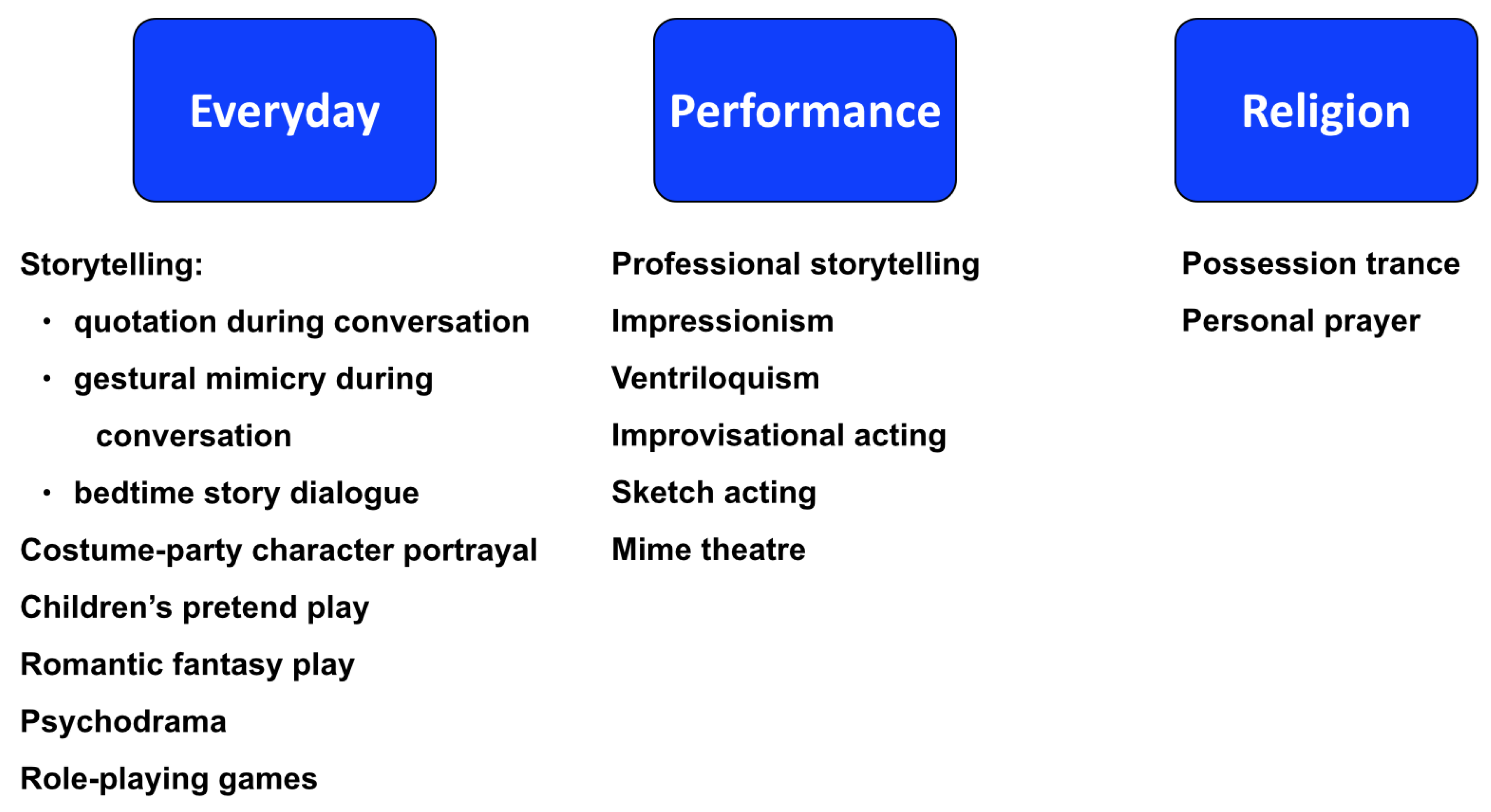

2. Features of Proto-Acting

Contexts and Forms

- ∙

- “Somebody’s been eating my porridge,” said Father Bear.

- ∙

- “Somebody’s been eating MY porridge,” said Mother Bear.

- ∙

- “Somebody’s been eating MY porridge and it’s all gone!” said Baby Bear.

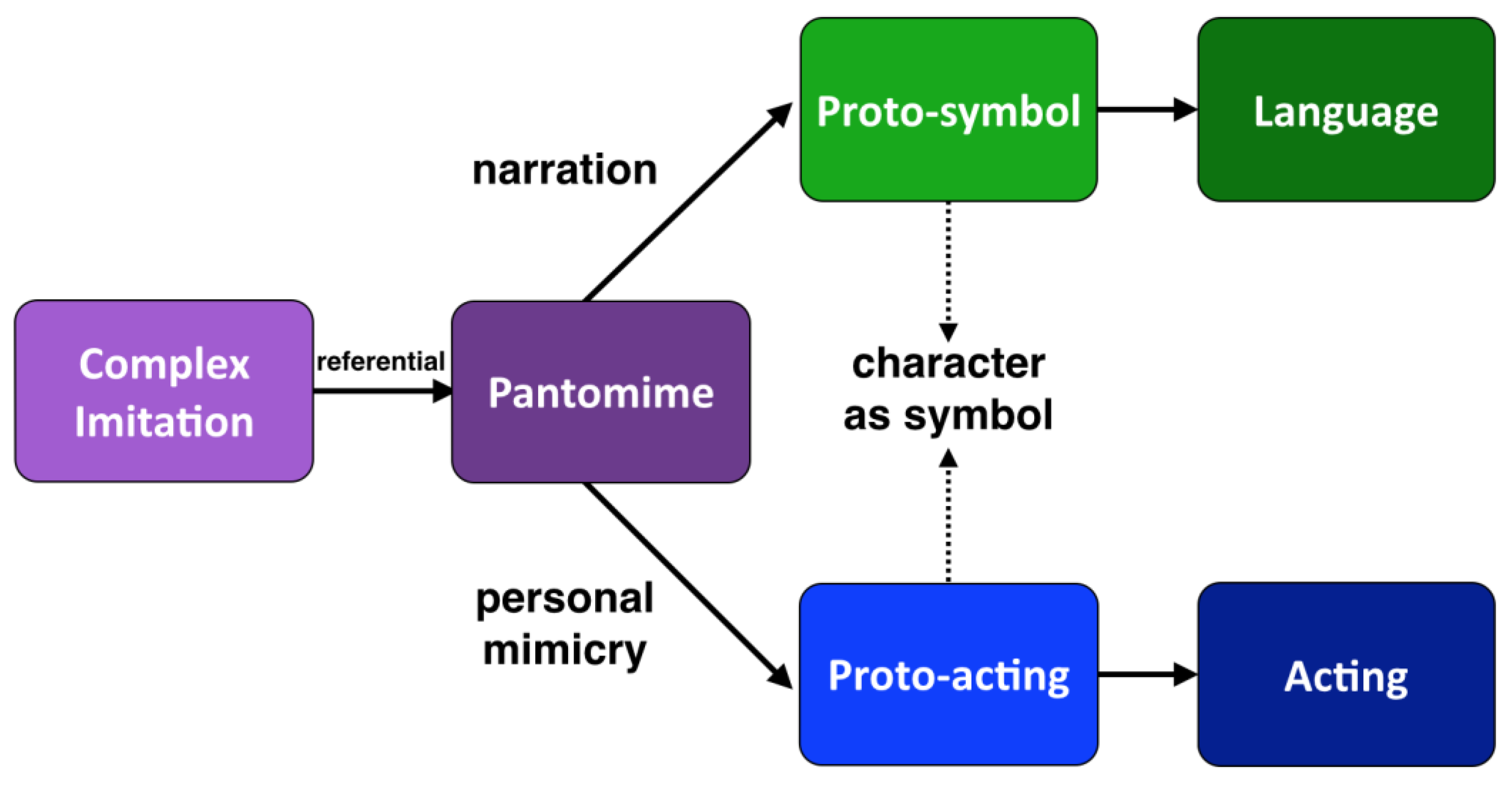

3. The Evolution of Proto-Acting

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arbib, Michael. 2012. How the Brain Got Language: The Mirror System Hypothesis. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arbib, Michael A., Katja Liebal, and Simona Pika. 2008. Primate Vocalization, Gesture, and the Evolution of Human Language. Current Anthropology 49: 1053–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, James H. 2009. Selfless Insight: Zen and the Meditative Transformations of Consciousness. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, David F., and Sherman E. Wilcox. 2007. The Gestural Origin of Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis, Chris J., and Malcolm W. Watson. 1993. Preschool Children’s Symbolic Representation of Objects through Gestures. Child Development 64: 729–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chartrand, Tanya L., and John A. Bargh. 1999. The Chameleon Effect: The Perception-Behavior Link and Social Interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 76: 893–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Amato, Rik C., and Raymond S. Dean. 1988. Psychodrama Research: Therapy and Theory: A Critical Analysis of an Arrested Modality. Psychology in the Schools 25: 305–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, Erving. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Anchor Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Edith. 2009. Introduction: Pantomime, A Lost Chord of Ancient Culture. In New Directions in Ancient Pantomime. Edited by Edith Hall and Rosie Wyles. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Paul L. 2000. The Work of the Imagination. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, Graham. 2006. Animism: Respecting the Living World. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hitchens, Michael, and Anders Drachen. 2009. The Many Faces of Role-Playing Games. International Journal of Role-Playing 1: 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, Rick. 2012. Embodied Acting: What Neuroscience Tells Us about Performance. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kipper, David A., and Timothy D. Ritchie. 2003. The Effectiveness of Psychodramatic Techniques: A Meta-Analysis. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice 7: 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konijn, Elly A. 2000. Acting Emotions. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leménager, Tagrid, Julia Dieter, Holger Hill, Anne Koopmann, Iris Reinhard, Madlen Sell, Falk Kiefer, Sabine Vollstädt-Klein, and Karl Mann. 2014. Neurobiological Correlates of Physical Self-Concept and Self-Identification with Avatars in Addicted Players of Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games (MMORPGs). Addictive Behaviors 39: 1789–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lillard, Angeline S. 1996. Body or Mind: Children’s Categorizing of Pretense. Child Development 67: 1717–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacNeilage, Peter F., and Barbara L. Davis. 2005. The Frame/Content Theory of Evolution of Speech: A Comparison with a Gestural-Origins Alternative. Interaction Studies 6: 173–99. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, Shaun, and Stephen Stich. 2003. Mindreading: An Integrated Account of Pretense, Self- Awareness and Understanding Other Minds. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, Anne W. 1995. Using Representations: Comprehension and Production of Actions with Imagined Objects. Child Development 44: 309–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouget, Gilbert. 1985. Music and Trance: A Theory of the Relations between Music and Possession. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schechner, Richard. 2013. Performance Studies: An Introduction, 3rd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman, David. 2017. The Presentation of Self in Contemporary Social Life. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Suddendorf, Thomas, Claire Fletcher-Flinn, and Leah Johnston. 1999. Pantomime and Theory of Mind. Journal of Genetic Psychology 160: 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tychsen, Anders, Michael Hitchens, Thea Brolund, and Manolya Kavakli. 2006. Live Action Role-Playing Games: Control, Communication, Storytelling, and MMORPG similarities. Games and Culture 1: 252–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, Kendall L. 1990. Mimesis as Make-Believe: On the Foundations of the Representational Arts. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilshire, Bruce. 1982. Role Playing and Identity: The Limits of Theatre as Metaphor. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zarrilli, Phillip B. 2009. Psychophysical Acting: An Intercultural Approach after Stanislavski. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

| Everyday Role Playing | Proto-Acting | Dramatic Acting | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self or Other | self | other | other |

| Personal Mimicry | no | yes, based on personal mimicry | yes, if gestural acting |

| Characters | personas of the self | familiar people | dramatic characters |

| Gestural or Mentalistic | more mentalistic than gestural | gestural | gestural or mentalistic |

| Role Changes | infrequent role changes | frequent role changes | few or no role changes |

| Alternation with Self | only self, hence no alternation | self/character alternation | no self/character alternation |

| Auto-Dialogue | no | yes | no |

| Context | usually everyday contexts | everyday contexts or performance | performance |

| Bout Length | short or long | generally short | long |

| Script | unscripted | unscripted or scripted | usually scripted |

| Use of Props | minimal use of props | some use of props | frequent use of props |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brown, S. Proto-Acting as a New Concept: Personal Mimicry and the Origins of Role Playing. Humanities 2017, 6, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/h6020043

Brown S. Proto-Acting as a New Concept: Personal Mimicry and the Origins of Role Playing. Humanities. 2017; 6(2):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/h6020043

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrown, Steven. 2017. "Proto-Acting as a New Concept: Personal Mimicry and the Origins of Role Playing" Humanities 6, no. 2: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/h6020043

APA StyleBrown, S. (2017). Proto-Acting as a New Concept: Personal Mimicry and the Origins of Role Playing. Humanities, 6(2), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/h6020043