Abstract

By using a carnivalesque strategy, netprovs discussed in this article introduced a disruption innovation into the social advertising market, a new source of value: creative satire. By playing multiple characters or forcibly separating the real person from the avatar they revealed the myth of the consistent online identity. By encouraging users to look on the other side of the mirror they sought to increase awareness of the real “why” these tools exist. Users were introduced to skepticism of online affection and of projected affection in general. Most importantly they promoted an alternative value network: a culture of contentment and satisfaction — satisfaction in play, in creativity. They created a value network of inner rewards, redeemable in the moment, good forever, producing a real community in which players demonstrate with intentionality genuine attention and approval in the improv manner, by saying “yes, and,” by elaborating others’ fictional themes and moments.

1. Intro (Rob)

We “Like” on social media, but do we like social media?

In a conversation with undergraduate students, we were sharing our daily media habits, an eye-opening experience for many. In the middle of a wake-to-sleep accounting of the apps and sites she visited daily, one student sighed and said, “Then I have to go on Facebook, even though I hate it,” and went on with her list. A few students later, her comment had finally registered with me. I stopped and asked the group “How many of you feel the same way she does about Facebook?” The majority of hands shot straight up.

When I followed up students described Facebook and other social media as stressful, competitive spaces in which they felt obliged to perform, to entertain, where they were constantly being measured and evaluated by Likes, Favorites, Reposts, and Retweets, an experience well-supported by research (Baker et al. 2016; Lee-Won et al. 2015, to name just two examples). One student said he had to check into social media many times a day to “see how he was doing” statistically.

“Social Media functions as a giant scoreboard to confer significance to events that are more or less meaningless in the moment,” writes Rob Horning (2012). “Getting likes on a photo of the meal you made yourself is more important and more significant than eating it” (Horning 2012). Metrics make the meal.

As Jacob Silverman, in Terms of Service, Social Media and the Price of Constant Connection, writes, “Metrics help create the hierarchies that are embedded in all social networks... ” and adds “… the goal of the digital space becomes not to enjoy yourself or aimlessly interact, but to rise higher in the game, which really can’t be won...” (Silverman 2016, p. 53).

Reflecting on the role of metrics, I began to view social media as a vast stock exchange of emotion, with statistics changing 24-7. My research led us to the dark art of “sentiment analysis” (Pang and Lee 2008) the statistical tracking and profiling of human emotion, which is used by hedge fund analysts, spy agencies and above all by the giant companies commonly known as social media, but perhaps more accurately known as social advertisers.

Because involvement in this emotional stock market was having clear psychological impact on the lives of not only our students, but friends and family as well—the actions of this market were hurting people’s feelings on a daily basis—my creative collaborator Mark C. Marino and I felt we needed to step in. When feelings are getting hurt systematically, creative writers are first responders. We began to produce participatory netprov (internet improv) projects dealing with these issues.

Nor were we alone in our response. We had seen artists who had dealt with similar systemic observations, notably Fred Forest and Ben Grosser. In a sense, these two projects book end our current media moment.

Years ago, my collaborators in the group Invisible Seattle were inspired toward our crowdsourced novel of Seattle by Seattle by an early French media artist, Fred Forest, and his Pompidou Center Installation Bourse de l’Imaginaire, (Stock Exchange of the Imaginary, aka, Stock Exchange of the Sensational) in June of 1982. Forest’s archive describes the project:

Through this Project, Forest flipped the relationship between audience and media producer, pointing the way to the present moment of the producing consumer (or prosumer).For a period of five weeks, the artist turns an exhibition space in the Centre Pompidou into the nerve center of a nationwide exchange of fictitious news items that are composed by members of the public. It is equipped like the headquarters of a news wire service with a phone bank (handling up to 8000 calls a day), a computerized database, video production facilities, and a full range of office equipment. Working 24 h a day, its staff of 15 are responsible for gathering, editing, displaying, archiving, and rating the news items….(Forest 2017)

Now years after we have all become broadcasters on our overlapping social networks, artists and critics have looked to intervene in our unhealthy relationship to our social ratings. Ben Grosser’s Facebook Demetricator, a browser extension, hides all the metrics on Facebook (http://bengrosser.com/projects/facebook-demetricator/). By turning off one of the key components of our continued engagement (and trigger of our insecurities), he reveals the emotional economy behind these self-produced content ecologies that were presaged by artistic works like Forest’s decades earlier. Both of these pieces act as disruptors of everyday experience because they bring to the surface this economy of emotion, as well as the anxiety it produces in us.

Growing out of similar concerns, three netprovs, #1WkNoTech (One Week, No Tech), I Work For the Web, and Trading Faces, each aimed to serve as market disruptors creating a “disruptive innovation” (one creates a new market and value network that disrupts an existing market) of the emotional stock exchanges, and show potential paths of escape.

2. Who We Are as Critters: Do I Belong?

As individuals, each of us has experienced a definite before and after, a time of relative unconcern about the esteem of others outside the family, and then, with puberty, a biologically determined time of all-consuming obsession about one’s wider social rank and social worth. It’s biological: our brains have evolved to give us chemical rewards for being well-liked.

From Catcher in the Rye to Sixteen Candles to Superbad, writers have focused on Middle School and High School as the primary modern arenas where our ranking-prone brains seek reassuring results. Novels and film fictions of middle age then frequently describe various ways of coming to peace (or not) with a sense of one’s ranking as one muddles through, and stories of old age often wrestle with a final accounting: what is one’s score when the game is over? The path of life can then be framed as a journey toward a reckoning of our own value in the world, and major world philosophies and religions address this process, whether by discounting or deconstructing pervasive systems of worldly value.

3. What Social Advertisers Are as Systems: You’re Not Where You Should Be!

If then he reasons users invest in the emotional stock market are complex, the reasons the companies who provide the platforms invest in it are simple and blunt. They are advertisers and the more they know about their audience the more money they can make from them. As Google’s Eric Schmidt brags: “We know where you are, we know what you like” (qtd. in Tsotsis 2010).

Advertisers have tools for mapping what we like. A Social Graph is the professional term for a web user’s complete profile: who you know, what you do, what you like. Facebook’s trademarked Open Graph, their proprietary data set on users, is arguably their chief asset. The more users share, the more Facebook profits, thus Mark Zuckerberg’s championing of the concept of “frictionless sharing.”

The most difficult kind of information to add to a social graph is subjective, emotional information.

Writer Nicholas Carr foresees a system for “...automating the feels” “Whenever you write a message or update, the camera in your smartphone will ‘read’ your eyes and your facial expression, precisely calculate your mood, and append the appropriate emoji.” This … removes the requirement for subjective self-examination and possible obfuscation” (Carr 2013)

And what are the goals of advertisers? As John Berger wrote way back in the Mad Men era of 1972: “The purpose of publicity is to make the spectator marginally dissatisfied with his present way of life” (Berger 1990, p. 142). And Christopher Lasch noted succinctly that “advertising institutionalizes envy and its attendant anxieties” (Lasch 1991, p. 72).

Behind the facade of networks of friends and Google Doodles, Google and Facebook are dissatisfaction engines.

As my fictional nom de clavier, Hans Paedeweyder recently wrote in my Facebook account:

Facebook is a communication experience that, instead of satisfying your need to know, constantly reinforces a subtle, haunting, desperate awareness of the other, more important communications you missed while you were away from Facebook. The longer you spend on Facebook the further you are from a sense that you know enough about your surroundings to relax and turn your attention back to your own goals and priorities.

This is where Facebook has done Coke one better. Coke created an artificial craving only they could satisfy. Facebook has created an artificial craving that nothing can satisfy. It is a beverage that makes you thirstier the more you drink it.

4. The ‘Feels’ vs. the Algorithm

- And when someone needs a makeover

- I simply have to take over

- I know, I know exactly what they need

- And even in your case

- Though it’s the toughest case I’ve yet to face

- Don’t worry - I’m determined to succeed

- Follow my lead

- And yes, indeed

- You will be

- Popular!

Wicked, Stephen Schwartz and Winnie Holzman

The sounds of active listening—“Mmmm,” “uh-huh,” “awww,”—these are some of the most important vocables in our intimate relationships. Likes, favorites, hearts—these are their social advertising equivalents. But these tokens of attention serve two masters. While they appear to tend to your relationships, they are also reporting back to headquarters, adding scores to your social graph. There is a simple kindness to these clicks, these gestures. There is an ethical anguish about reciprocity (“she liked my post, must I like hers?”). In a time without a common digital etiquette, this causes a lot of hurt feelings.

While the metrics of response seem to reaffirm your value, they are instead conditioning you and subjecting you to another system of validation. Social advertising scorekeeping confirms that you’re “doing a good job” of parenting, vacationing, eating. It is your performance review as well as your ticket into a lottery of externally awarded self-worth.

So with what tools might one disrupt this system? Humor. Despite deep learning studies aiming at increasingly subtle facial recognition and slang recognition, to date sentiment analysis algorithms are bad and parsing sarcasm and humor. Humor itself is a form of blessed invisibility. Satire can be understood by humans but not by machines.

5. Netprov: An Emerging and Emergent Form

To intervene in the world of social media, various artists have embarked on a practice which combines improvisation and collaborative linguistic and narrative play with contemporary social media. Rob Wittig has called this form, netprov, and have been developing it through a series of collaborative projects (cf, Meanwhile Netprov Studies site: http://meanwhilenetprov.com/).

The form picks up the literary baton passed on by the games and ludic creation of the Surrealists, Situations, and Oulipo (Ouvroir de littérature potentielle). However, it owes just as much to live-action role play (LARP) and other forms of personified play. The “prov” of netprov harkens to arguably its strongest influence, theatrical improvisation in a lineage from classical commedia dell’arte to the Twentieth Century work of Dell Close, founder of the famed Second City improv troop in Chicago, from which many theatrical games and additional improvisationa theatres have sprung directly or indirectly. Wittig, Robert Gardner. “Networked Improv Narrative (Netprov) and the Story of Grace, Wit & Charm.” (Wittig 2011)

A typical netprov, if such can be described, involves a networked of platform (such as Twitter, a blog, or Facebook), a set of collaborators, a narrative premise, and a set of constraints. For the most part, netprovs have time limits, although that is not a necessary requirement. Fundamental to netprov is creative play on contemporary platforms.

One of my earliest netprovs was a project called Grace, Wit, & Charm, an office comedy about workers in a fictional company devoted to helping you polish your online persona. However, a netprov with more thematic ties to this paper may be The Chicago Soul Exchange, on which people bought and sold a limited number of past lives (since the current number of people on the planet far out-number any previous population). But netprovs can be as light-weight as a fictional Twitter account or even a fictional post on a blog.

6. #1WkNoTech

#1WkNoTech (2014 and 2015) was a netprov in which participants pretended to use no technology for a week and documented the “experiment” obsessively in social media. The netprov consisted of: real and fictional Twitter accounts; a fictional organizational website; a fictional organizational Facebook page; and private documents for featured players in Google drive.

The invitation to netprov players was extended on the project website:

“It’s Just 1 Week.You know you should cut down—even quit—your dependence on technology, right? But it’s hard. Too hard to do by yourself!That’s why we’ve created the #1WkNoTech community to take a stand from November 10–16.We’ll support each other in 1000 ways so we can all step back from the madness, take a breath and get real!Join our active and supportive community! We’ll keep you company throughout your own personal version of #1WkNoTech.How to participate:Narrate your own version of #1WkNoTech, day-by-day: will it be heaven? will it be hell?Show us yourself enjoying a peaceful moment in the woods!Share the glories and horrors of battling tech withdrawal over Twitter!Post a pic of you throwing your phone away!

There were butterflies in stomachs as the start time of the project drew near.

Mike & Sara @mikensara4ever · November 9.wait a minute. how are we going to favorite each other’s #1wknotech tweets?#onehandclapping.The first few days paid off the basic joke of the netprov.

(ノ

ω

)ノ~ @lolidkgina · November 10.

roomie just asked to play words with friends... I had to suggest actual Scrabble.And now I can’t google acceptable Q words. #1wknotech.

Melissa Ng @MelissaNg11 · November 10.Bet my parents in Ohio are dying to know how my interview today went. Keep wondering, parents! #1wknotech.

Manic AF @MP89MP · November 10.But seriously think of all the fun stuff you can do without technology! The possibilities are ENDLESS. I feel lonely. #1WkNoTech.

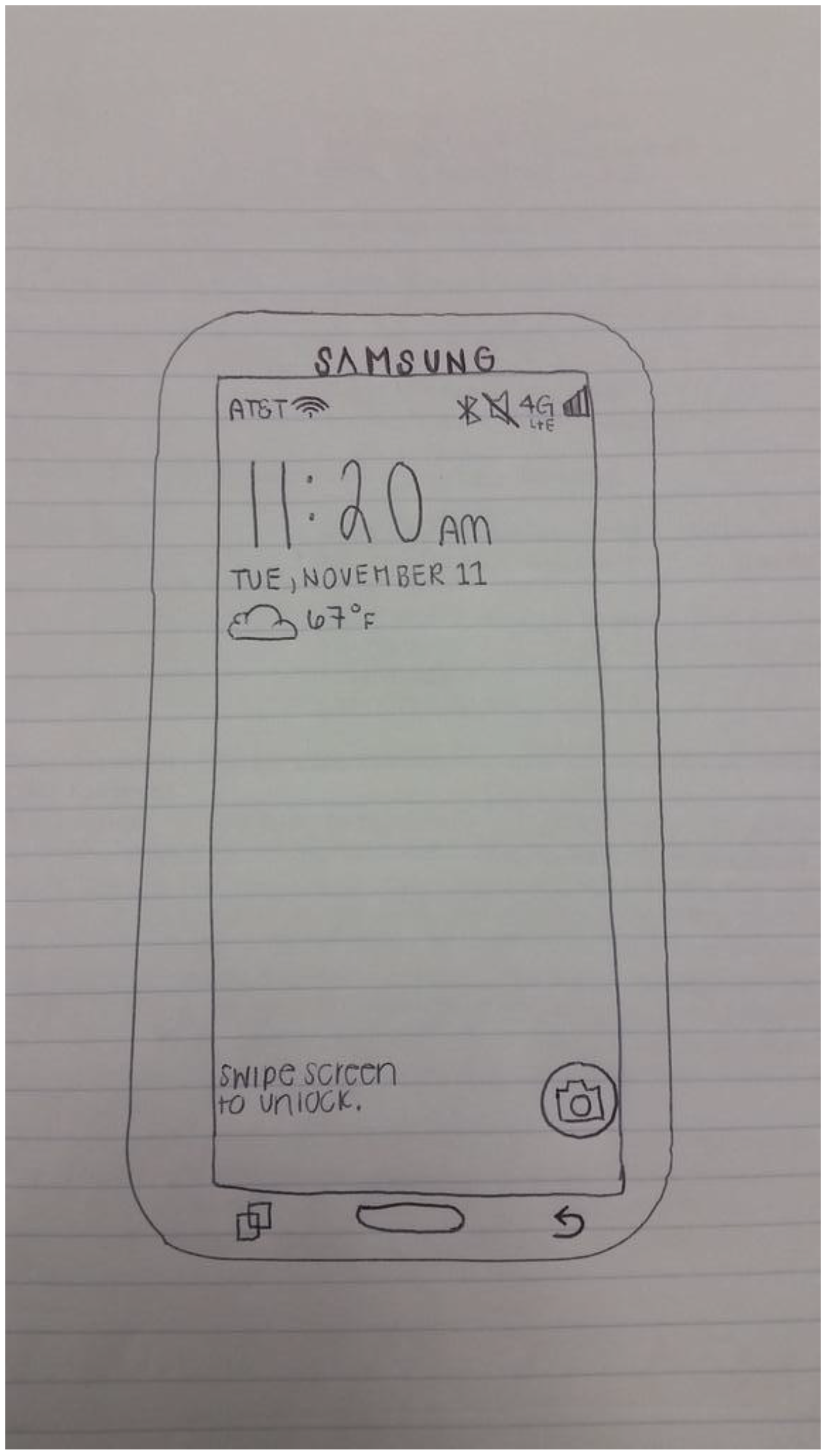

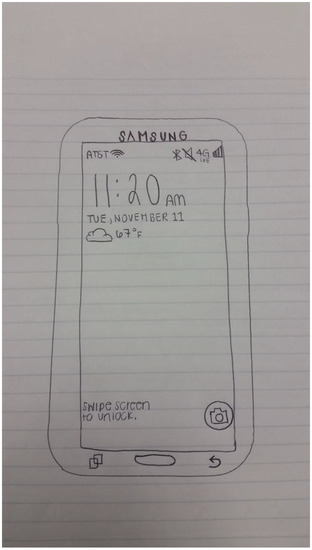

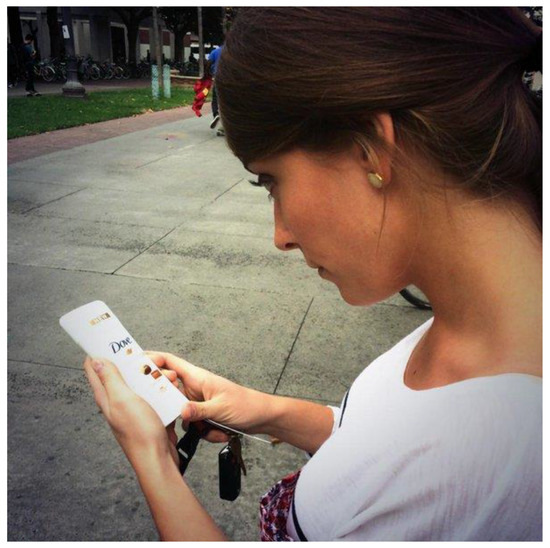

Brittani Thompson @brittanithomp · November 11.My phone for the week #1wknotech #tumblr. (See Figure 1). Figure 1. Image from @brittanithomp Twitter post.

Figure 1. Image from @brittanithomp Twitter post.

bhallamk @Bhallamek · November 11.my face was always buried in the laptop, never noticed how STRANGELY my dog stares at me al day. #1wknotech #tumblr.PICTURE AVAILABLE.Sasha M @sasha_m98 · November 11.The great thing about #1wknotech is that I don’t have to be bombarded by images of people having a lot more fun than I am.

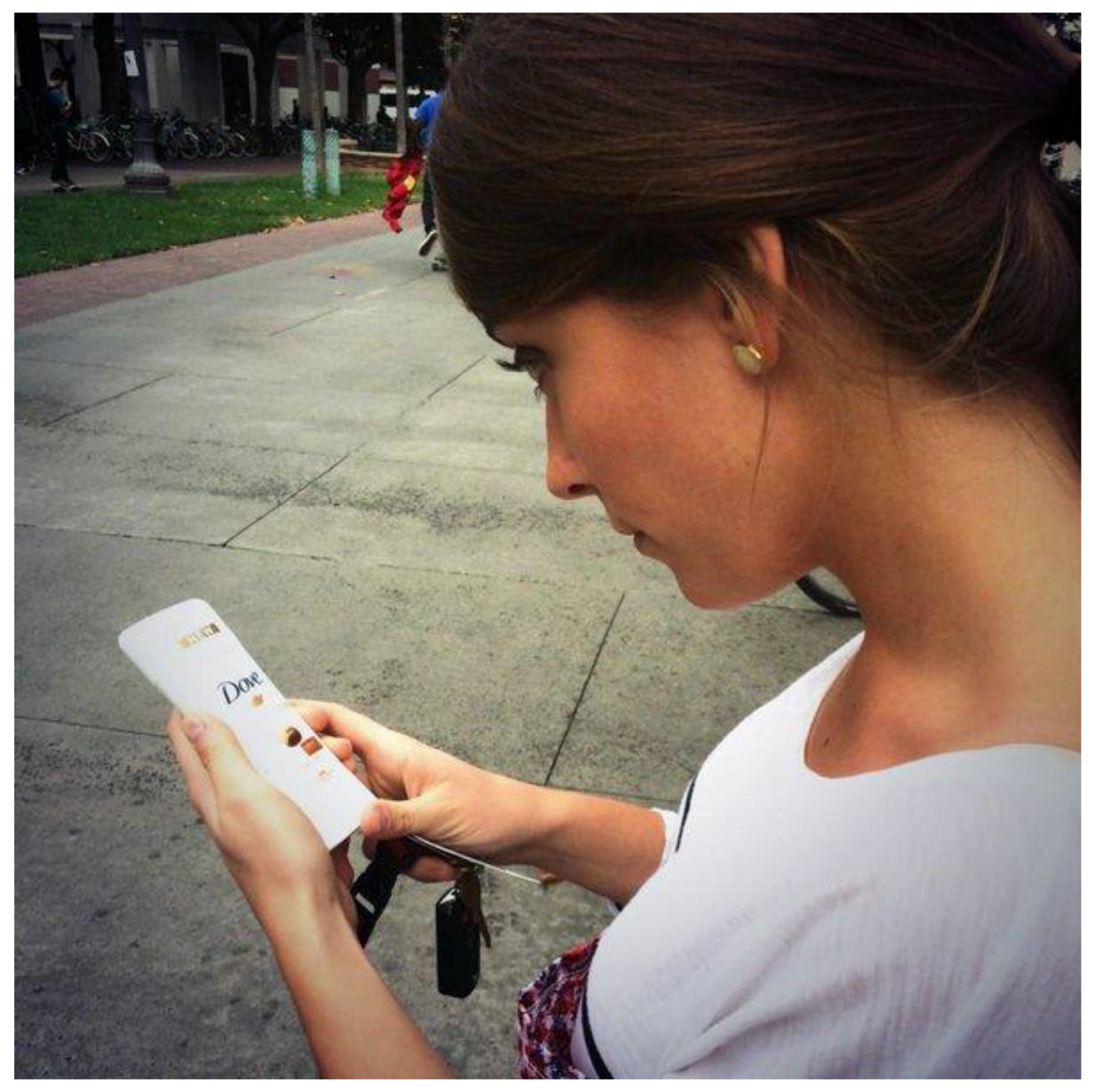

Grace Anaclerio @Granaclerio 11 November 2014.Catching myself staring vacantly into small rectangular objects...Force of habit. #1wknotech #tumblr. (See Figure 2). Figure 2. Image from @Granaclerio Twitter post.

Figure 2. Image from @Granaclerio Twitter post.

Sketchy McGinn @Sketchy_McGinn · November 12.Each hour that goes by, it feels better and better to know I’m not using Twitter.Starting to feel bad for the people who are. #1WkNoTech.

Then anxiety began to set in. The emotional markets were closed.

Lita_lota @litalota228 · November 11.Having night anxiety without my phone near by bedside #1wknotech #whatislife.

Jack Taylor @karb0020 · November 11.I changed my mind I need class to not be canceled so I have something to do rather than lay in bed crying all day. #1wknotech.

Manic AF @MP89MP · November 11.I feel so trapped in an analog world. Nothing is discrete or incremental, just continuous like eternity. #1wknotech #continuity #nondiscrete.

Manic AF @MP89MP · November 12.I wonder if my family is still alive? #1wknotech.

Grace Anaclerio @Granaclerio 14 November 2014.Can we pls talk about how Miley was at the USC game and I had to find out afterwards by word of mouth like some basic commoner? #1wknotech.

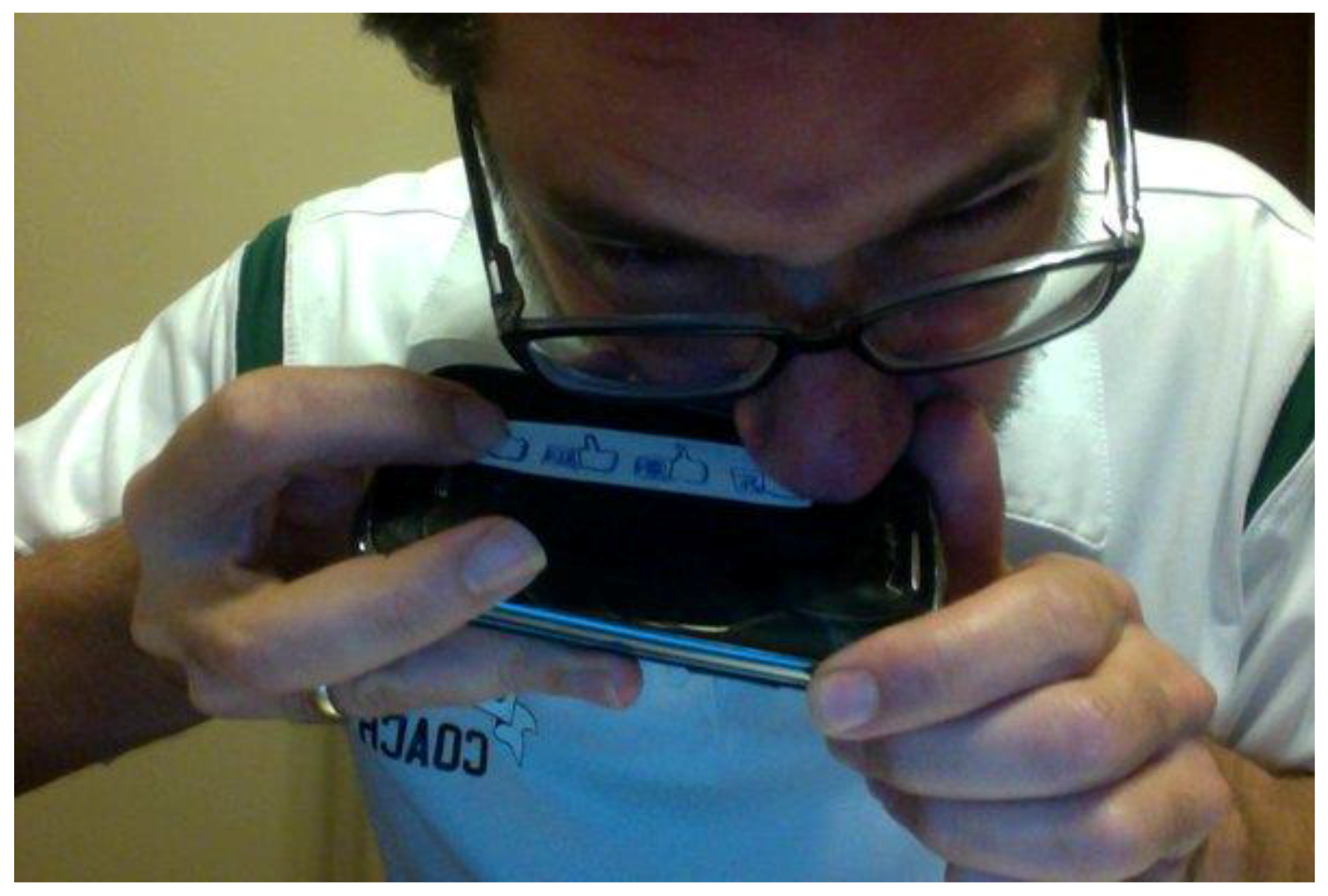

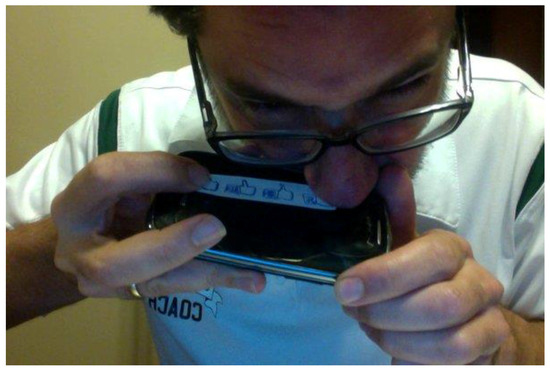

Amanda S Gould @stargould · November 12.With no tech and no friends we must like our own #1wknotech posts.#augrealities. #notechmoreproblems #tumblr.Kathi Inman Berens @kathiiberens · November 15.LIKE withdrawls. #1wknotech #digiwrimo #tumblr #FOMOM.Mark C. Marino @markcmarino 15 November 2014.Snorting a line of LIKEs off my powered down phone #1wknotech #tumblr. (See Figure 3). Figure 3. Image from @markcmarino Twitter post.

Figure 3. Image from @markcmarino Twitter post.

0 retweets 3 likes.

Sketchy McGinn @Sketchy_McGinn · 19 h.Starting to feel bad for my food. It’s practically begging to be photographed.#1WkNoTech.

By the end of the week the strain was beginning to show.

Chris Gnarley @Chris_Gnarley.@CooperV12 seriously. I’ve missed out on so much reassurance of worth via likes. never be the same #1wknotech #FOMO.

What Am I Doing? @whatamidoing_16 · 12 h.I am going to slightly miss this week of no tech though. Oh, wait. No I’m not.#1wknotech.

Lita_lota @litalota228 · 10 h.Farewell #1wknotech. You end in 15 min. Let the sleep deprivation over.Instagram/Facebook nonsense commence! #goingtomiss1wknotech.

7. #1WkNoTech Reflection: Do I Exist?

The formula ‘I share, therefore I am’ is now a commonplace in media analysis. But the complete cycle of activity is the sharing plus the reaction. Social advertisers Facebook and Twitter create an environment where judgment is inflamed, for to judge is (eventually, they hope) to buy. The discriminating consumer discriminates. Everybody knows why there are no “dislike” buttons: even without them people are routinely crushed by haters. There is a dark sewer of hate beneath the shiny, positive streets of Facebook.

Why is the judgmental nature of Facebook and Twitter so painful? Because the system is a set up. It is built to reward not sharing but oversharing. “We often use confessionalism… to curry attention by being willing to make the confession itself,” notes Jacob Silverman. This confessionalism, he points out “allows for us to gain some of what is most scarce in this economy: time and attention.” And it allows social advertisers to reap the richest data: intimate data. They coax you to reveal intimacies they know will make you prey to trolls. They profit from both.

For users it is that perception of received time and attention that is paramount and leads so many compulsively back to the phone to chart their stats? How many likes or faves or retweets makes a post worthy? Is there ever an “enough?”

8. I Work for the Web

In the netprov I Work for the Web, which ran April 6–14 2015, players realized their addiction to the “Like” thumb (the small “thumbs-up” illustration), even as they recognized that it pokes us all in the eye. As they imaginatively performed the impossibility of getting themselves out from under this thumb, they took the opportunity to turn it upside down.

The seed for I Work for the Web grew out of a post Mark wrote on his Facebook account:

From this came the ad campaign of the benevolent Internet monopoly along the lines of the great vertical monopolies of America’s antitrust heritage.“For those of you asking how things have been going here at Facebook Dept. of Likes: generally everything is hunky-dory. Everywhere you look there’s someone throwing a thumbs up (or Flipping the Zuck). But I’ve started noticing different kinds of Likes. Like the not-so-nice Likes, and sometimes it seems like people feel obligated to do it, like they’re afraid if they don’t thumb up everything they might miss out, miss some opportunity, lose some social media capital (which come back to us as bonuses paid in FaceBucks to use in the company store). So while all and all things are really swell, I’m starting to suspect something beneath the surface—though I try not to notice it.So mostly things are A-Ok.”

Technically, the netprov consisted of: fictional Twitter accounts; fictional organizational website; fictional organizational public Facebook page; a private Facebook page for featured players; and private documents for featured players in Google drive.

In the frame fiction the viral “I Work for the Web” campaign is launched by RockeHearst Omnipresent Bundlers, the “exployer” (exploiter/employer) who owns the internet, and its charismatic leader, Andrew Rockehearst, Sr. (@tycoonthropist).

The exployer’s website exhorted:

You work for the Web!And it’s so easy, you probably don’t even know you’re doing it!Likes 59%Favorites 89%Friends 51%Favorable Comments (Ouch, you’ve got to work on that!) 12%

We gave you a stage to perform on!We let you upload your dreams and images to the clouds!

So tell us your stories on Twitter and Facebook!Now!

The Stats Don’t Lie

38%Awkward Moments.

29%Waiting On Downloads.

66%Friends Ignoring You.

100%Time On Device.

Earning Your AttentionBe Proud of Your Contributions!

Sending Comic Selfies, Trying New Emoticons, Inventing New Passwords, Clicking Celebrity Teases, Counting Your Likes, Winning Next Level, Re-typing Captchas.

The wheels of the Web turn on your generosity!You’re welcome!

The website contained an animated slide show, the text of which read, in part:

The World Wide Web, every post, every selfie, every like50 billion posts each secondThe work you do collectively could LIGHT up the entire WORLD

Andrew RockeHearst, Sr.He put the Web to Work for You...Just a twinkle in his eye...And has made it HIS life’s workTo build a cyberspace where Workfeels like Play!Say it loud, Say it proud:I Work For the Web!RockeHearst Omnipresent Bundlers says: Tell us your story #IWFW**By Tweeting your story using the #IWFW hashtag, you waive all copyrights and contribute your content to R.O.B. Marketing and Promotions.(Marino and Wittig 2015)

RockeHearst’s campaign backfired when web workers—“emplustomers” (employee/customers)—realized how much labor they’d been contributing for free in the form of click-throughs, likes, upvotes, favorites, reposts and other normal web behavior. As players engaged with the IWFW, through fictional and real accounts, they decided whether their characters would buy into the union and walk out of this complicit economy of what Davin Heckman’s character dubbed “emplovers” (employer lovers).

As a union movement arose of the International Web and Facetwit Workers (also, IWFW), players decided whether to side with Rockehearst or the workers protest movement, culminating in a vote (Like thumbs up or down) to decide the fate of the movement. Mark as the tycoonthropist was a thin-skinned demagogue railing at the ingratitude of the rebellious emplustomers. Votes for the union took the form of a photograph of a real hand in the Facebook Like “thumbs up” position; the exployer’s minions promptly flipped them over into thumbs down images and retweeted them.

Writer and theoretician Talan Memmott’s character Link Dinn became the shop steward for the IWFW union. Represented by an avatar of brave little wooden toy, Link Dinn produced rousing posters and exhortations, was stalked by the tycoonthropist’s private army of “Pingertons” and finally assassinated. A photograph of a pile of woodshavings marked his demise.

The week culminated in a fingertip “walkout” of the emplustomers.

9. IWFW Reflection: Who Am I Working for?

I Work For the Web attempted to show netprov players the other side of the social advertising mirror. In reality, everything that seems like it is for you, the user, is also for them. Emoticons on Facebook are not for you, they’re for them, so that they can quantify your emotions and sell the data. Autocorrect is not for you, it is for them, because computers are not as good at decoding misspellings as you are. Captchas are ways of getting you to do unpaid work: reading house numbers machines cannot decode. The We said to RockeHearst: You don’t know me! Protection of inner experience

The moment kids realize no one can read your mind.

The goal of the social advertisers is to customize feeds tailored to the desires and affections of each user. These ultra-customized feeds intensify the American reluctance to look at our economic experience in terms of groups or classes, but instead as individual successes or failures, as counted on the scoreboard in traditional ways (money, house, clothes, toys) or new ways (likes, favorites, retweets).

One of the major insights of I Work For the Web was that tweeting as different characters using multiple accounts was in itself a rebellion, a shoe in the gears of social advertisers, since amassing preference data under a single, real-life social graph is paramount to their business model.

10. Trading Faces (2015)

“Like all good literary projects, it began over drinks in a bar,” began Mark C. Marino in an interview I conducted with him and Claire Donato about their netprov duet, Trading Faces, in which they swapped Facebook accounts. According to Marino in the LA bar he and Donato “were talking about our social media in general, our interests, things that irritate us. I mentioned some dismay that no matter how fictional you try to be Facebook, people seem to return to the veracity of it in ways that in the early days of the Internet was inconceivable. You’d assume as a matter of course that someone on the Internet was probably not the person that they were saying that they were. But President Zucks and Co. have figured out a way to make it seem authenticated. I think that puts most users at a disadvantage when they interact with that system.”

Donato continued with the netprov’s genesis:

- Claire:

- Mark, you were telling us about an experiment. I don’t know if you actually pulled off this experiment with your class, or if it was speculative. But you had perhaps said to your class, “What would happen if everybody on social media moved over one seat to the left, and hopped on somebody else’s accounts?”

- Mark:

- That’s an experiment I do with my freshman writing class, in order to get them to see the way their newsfeed is filtering the world for them. But, of course, the idea is that you watch it only, because it would be unthinkable to have someone else touch your account. Just think of the damage they could do to you…. And somebody said, “Well, what if we swapped accounts for a while, and saw what happened?”

- Claire:

- Totally appealing. At which point, I think I said something like, “Oh, I would do that with you.”

- Mark:

- So, because I think maybe we put that out there as something that seemed so dangerous, that it immediately seemed like the next thing that we should do.

- Claire:

- And before we knew it, we had our tiny notebooks out, and had exchanged our login information and passwords; and, shortly thereafter, were exchanging our habits with one another in our notebooks.

- Claire:

- Yeah. My notebook says “no children’s names.” “Discretion.” It says “trust description.” “You are not your Facebook.” “Be the person relaying news.” And “LIKE EVERYTHING” is written in all caps.

- Claire:

- Mark, I remember in this conversation that you described yourself as a very enthusiastic Facebooker. I don’t like the word positive, but you’re like an ebullient presence there, and somebody who “likes” a lot. So I have a note on that.

- Mark:

- Yes, I am the face of a Facebook optimist. In my notes I have: If someone received a direct message from somebody through Facebook then we would relay it to the person and consult about how to respond.

The Trading Faces netprov had three phases.

- Mark:

- In the first phase, we were trying to pass as the other person, although there was a lot of fiction that happened then. Phase Two was a blur — where we’re sort of merging ourselves and the other person. And then, Phase Three was when we became fully ourselves in the other person’s avatar.

- Claire:

- We had originally intended it to be seven days, but I think it wound up being about eight days. So I would say that perhaps the first phase was about three days, the blur was three days, and the last phase was maybe two days?

- Mark:

- I’ve always liked the part of netprovs before we indicate clearly that they’re neprovs, for whatever reason. I would talk to Claire about what her daily routine is. Claire said she’s working on her novel, or she might go for long walks, things like that. Those little seeds of revelation to each other became what we would post. First, I had Claire say that she was sick of Facebook. She was just tired of it. And then she got so many “likes” for that comment. Except, of course, we had decided that we were going to post between like four and seven times a day.

- Mark:

- So within a few moments, I had to take that back and start posting about how things were going in LA. And I think the first day, I might have been pretty mild. But then, the second day, I had her go for an audition for what was going to be a car commercial, and it ended up being a prescription drug. And then, I think, it became surfing, I think, ultimately, was what the commercial ended up being for.

- Claire:

- Yeah. So, for example, like on the day when Mark sent me to the beach—which I think, too, was the day I actually went to the beach—I had Mark go to the beach as well. So there was a moment in which Claire-as-Mark thought that she saw Mark-as-Claire at the beach.

- Claire:

- I think, for me, it was hard to pass, not so much linguistically—though I don’t know that I like wholly captured your tone, Mark—

- Mark:

- I think you were much more poetic that I ever am.

- Claire:

- I think I just tend to be like a little bit too lyrical, and maybe interior, existential in my modes of using Facebook. But I think I ventured from Mark’s actual reality maybe sooner than he ventured from Claire’s actual reality. I immediately had him take on his really intense fitness regimen. And then he ultimately goes to CrossFit and gets injured. So I think I was a bit too hyperbolic in the passing phase.

- Mark:

- We would e-mail each other pictures that the other person could use in subsequent posts. You know, partly as inspiration, and partly as sort of proof that this is happening.

- Claire:

- And then we were basically chatting every night—right, Mark?—on Facebook. So I would be in Mark’s Facebook and Mark would be in my Facebook, and we’d be chatting with each other.

- Mark:

- And then those little seeds grew into bigger stories. You know, I think you still passed as me in that case. It just wasn’t a realistic story that was being told. Similarly, I don’t think people necessarily believed that she was auditioning for a commercial. They believed it was Claire telling a story about auditioning. Recently, I met with (fan-fiction and transmedia guru) Flourish Klink, and she told me that she recognized the trickery right away.

- Claire:

- I know Flourish pretty well. Whereas I ran into somebody I don’t know particularly well at a bar. And this person was like, “Oh, I thought you moved to LA.” So, I mean, there is residue from this project.

- Mark:

- As we entered into the blur, it became very anxiety-producing for me, very scary. Not only was I still trying to pull off being Claire, but I was trying to get into additional layers of trying to pull off being Claire while no longer trying to pull off being Claire. And then she was doing things with my character that were more out of character—but in character with herself—that colleagues or slightly closer friends were reacting to with delight. Like they were so happy that I had taken up yoga and was perhaps becoming a yoga instructor. I don’t know if I told Claire this, but I did receive one text and subsequent call from a friend asking if something was wrong; that I didn’t sound like myself on Facebook.

- Claire:

- Oh, no!

- Mark:

- And she wanted to know what was going on.

- Claire:

- What’s funny is a lot of people expressed concern over Claire’s mental state, but nobody really checked in on it in person. So they thought she was suicidal or having a nervous breakdown.

The netprov reached its third phase.

- Claire:

- So by the end I would be logged into Mark’s account, and Mark’s photograph would be like a half-and-half Mark-Claire split. And I would be chatting as Mark to Claire. It was really disorienting—the different layers of persona and presentation. I would often forget who I was, and whose account I was logged into. Perhaps our avatars like take on these lives of their own. Mark can be logged in as Claire, but maybe Claire-the-avatar, is still Claire in some sense.

- Mark:

- Yeah, I think it’s interesting that you (Claire) felt freer doing things with you (Claire on Facebook) when I was inhabiting your avatar.

- Claire:

- Yes, I almost didn’t have to see what would happen on the other end. I could just put it into the world via you, and then whatever the repercussions of that would be, you could deal with it.

- Mark:

- I was relieved to be back to being me. It’s certainly easier than trying to be myself being someone else. And then there was the anxiety of how people were receiving the being who was not me. And yet, I think that project stayed with me, maybe more than some of our netprovs. Usually I’m always sad when they end.

- Claire:

- I got so attached to Mark’s friends while playing him that I was really sad to leave. Those emotions were very real. But I’ve learned there’s not a way to recreate the experience of someone else’s account in one’s own account. So I’m just back to my same old not-using-Facebook habits.

11. Trading Faces Reflection: Whom Am I? Whose Am I?

In Trading Faces, as in the other two netprovs, the constant and unremarked theatricality of self-presentation was made obvious. Donato and Marino were confounding the advertisers as well as their friends.

12. The Currency of Social Capital: False Value

Playing more deeply with the concept of social capital, troubling questions arise. What exactly is being traded? Does it accumulate? How? Can it be spent? Do Likes equal being liked? Are Facebook friends friends?

Jacob Silverman (2016) is right in pointing toward social capital as equaling time and attention. But is there real value there? Every web user knows that clicks and page visits do not necessarily equal attention. As a Slate article points out “data suggests that lots of people are tweeting out links to articles they haven’t fully read.” Media users skim, skip and attempt to multitask.

Like all authors, social media users boost their egos by projecting that readers read with full attention. But media metrics can only measure physical actions, not depth of reception. The most the statistics can really say is, in the words of the kindergarten jokester, “Made you look!”

Silverman (2016) is only partly correct. What users long to have the statistics represent is more than time and attention, it is affection. Here again social capital reveals itself to be a mirage. Why do people press “Like?” Again, as we all know, we press “Like” for a complex blend of reasons—obligatory reciprocity (she liked me so I’d better like her), envy, favor-currying, irony and more. We float in the social advertisers’ world in profound denial, wanting to believe that Likes represent real value. Like it or not, “Likes” are false value.

But what about the millionaires of social capital, the celebrities, the viral sensations? What do they really have? Celebrities’ attention counts more than others. How can they spend their riches? By receiving attention they have accumulated the power to bestow it. They can bestow false value. Social capital can only be spent on one thing: making people look, for an instant.

13. Conclusions

By using a carnivalesque strategy, these netprovs introduced a disruption innovation into the social advertising market, a new source of value: creative satire. By playing multiple characters or forcibly separating the real person from the avatar they revealed the myth of the consistent online identity. By encouraging users to look on the other side of the mirror they sought to increase awareness of the real “why” these tools exist. Users were introduced to skepticism of online affection, and of projected affection in general.

Most importantly they promoted an alternative value network: a culture of contentment and satisfaction—satisfaction in play, in creativity. A value network of inner rewards, redeemable in the moment, good forever. A real community in which players demonstrate genuine attention and approval in the improv manner, buy saying “yes, and,” by elaborating others’ fictional themes and moments.

But who’s keeping score?

Author Contributions

Rob Wittig and Mark C. Marino collaborated on the research for the paper. Rob Wittig wrote the substance of the draft. Mark C. Marino added some quips and tidied things up a bit.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baker, Zachary G., Heather Krieger, and Angie S. LeRoy. 2016. Fear of Missing out: Relationships with Depression, Mindfulness, and Physical Symptoms. Translational Issues in Psychological Science 2: 275–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, John. 1990. Ways of Seeing: Based on the BBC Television Series, rep. ed. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, Nicholas. 2013. Automating the Feels. Rough Type. Available online: http://www.roughtype.com/?p=3693 (assessed on 25 May 2017).

- Forest, Fred. 2017. Web Net Museum-Fred Forest-Retrospective-Sociologic Art-Aesthetic of Communication-Artworks-Actions-The Stock Market of the Imaginary. Available online: http://www.webnetmuseum.org/html/en/expo-retr-fredforest/actions/23_en.htm#text (accessed on 25 May 2017).

- Horning, Rob. 2012. Fragments on Microcelebrity. The New Inquiry. Available online: https://thenewinquiry.com/blog/fragments-on-microcelebrity/ (accessed on 25 May 2017).

- Lasch, Christopher. 1991. The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations, rev. ed. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Lee-Won, Roselyn J., Leo Herzog, and Sung Gwan Park. 2015. Hooked on Facebook: The Role of Social Anxiety and Need for Social Assurance in Problematic Use of Facebook. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 18: 567–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, Mark C., and Rob Wittig. 2015. I Work for the Web—It’s Almost Like a Job Except It’s Too Much Fun! Available online: http://robwit.net/iwfw (accessed on 24 May 2017).

- Pang, Bo, and Lillian Lee. 2008. Opinion Mining and Sentiment Analysis. Delft: Now Publishers Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, Jacob. 2016. Terms of Service: Social Media and the Price of Constant Connection, rep. ed. New York: London: Toronto: Sydney: New Delhi: Auckland: Harper Perennial. [Google Scholar]

- Tsotsis, Alexia. 2010. Eric Schmidt: ‘We Know Where You Are, We Know What You Like.’ TechCrunch. Available online: http://social.techcrunch.com/2010/09/07/eric-schmidt-ifa/ (accessed on 25 May 2017).

- Wittig, Rob. 2011. Open Research at the University of Bergen. Available online: bora.uib.no (accessed one 25 April 2017).

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).