Abstract

This article continues my earlier work of reading Jung with Lacan. This article will develop Zizek’s work on Lacan’s concept of objet petit a by relating it to a phenomenological interpretation of Jung. I use a number of different examples, including Zizek’s interpretation of Francis Bacon, Edvard Munch, Hans Holbein and Johann Gottlieb Fichte, to describe the objet petit a and its relationship to a phenomenological interpretation of complexes. By integrating other Lacanian concepts, such as subject, drive, fantasy, jouissance, gaze, desire, and ego as well as the imaginary, symbolic and Real, this work also highlights how Hegel and Heidegger can elucidate the relationship between objet petit a and complexes. Jung’s transcendent function and the Rosarium Philosophorum also elucidate the relationship between Jung and Lacan.

1. Complex as Foreign Body

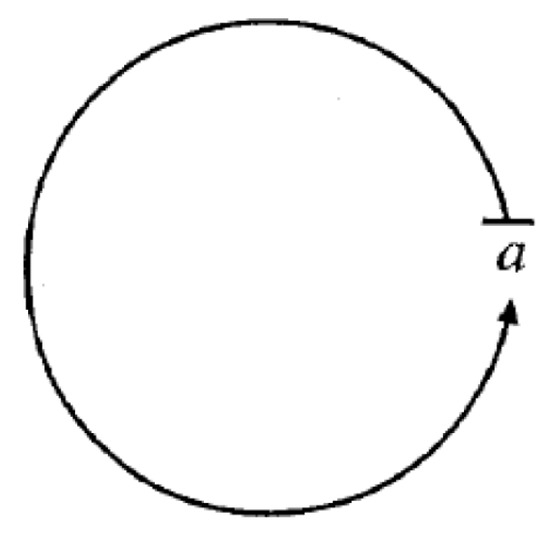

This article continues my earlier work of reading Jung with Lacan [1]. Penot says “And it is indeed an intimate and continuous frequentation of the stranger in oneself that should be required of anyone who intends to become a psychoanalyst for others” ([2], p. 6). I will describe how to engage in a “continuous frequentation of the stranger in oneself” by reading Zizek’s interpretation of Lacan’s objet petit a with a Heideggerian interpretation of Jung’s writing on complexes. Zizek explains the objet petit a such that “even if the psychic apparatus is entirely left to itself, it will not attain the balance for which the ‘pleasure principle’ strives, but will continue to circulate around a traumatic intruder in its interior—the limit upon which the ‘pleasure principle’ stumbles is internal to it. The Lacanian mathem for this foreign body, for this ‘internal limit’, is of course objet petit a: objet a is the reef, the obstacle which interrupts the closed circuit of the ‘pleasure principle’ and derails its balanced movement—or, to refer to Lacan’s elementary scheme” ([3], p. 48).

The relationship of objet petit a, to Jungian psychoanalysis can be identified by comparing it to a phenomenological interpretation of complexes [4]. My earlier work shows that a complex is phenomenologically disclosed “when Dasein’s world is conspicuously experienced as unready to hand and “not-being-at-home” ([4], p. 967).” In the event of a complex, angst, conscience and guilt are experienced in a moment of conspicuous obstructiveness and obstinacy, which results in the ready-to-hand losing its readiness-to-hand in a certain way. In other words, the experience of a complex is an experience of objet petit a: a complex disrupts the “pleasure principle” because of “a traumatic intruder”. When this “foreign body” is encountered “Dasein’s world is conspicuously experienced as unready to hand and “not-being-at-home”([4]. p. 967)”1. This initially highlights the compatibility of complexes with objet petit a. This relationship can be further elucidated by reading a phenomenological interpretation of complexes into Lacan’s schema (Figure 1). The objet petit a, which derails the balanced movement of the pleasure principle, also depicts a “conspicuous obstructiveness and obstinacy, which results in the ready to-hand losing its readiness-to-hand in a certain way” ([4], p. 967). When Lacan and Jung are read alongside Zizek and Heidegger, we can see that this derailment of the pleasure principle by objet petit a (Lacan) or a complex (Jung) also results in the experience of angst, conscience and guilt (Heidegger).

Figure 1.

Hoop net ([3], p. 48).

Complexes arise when an analysand’s understanding of existence is inauthentically narrow and dogmatically averse to the authentic meaning of the call of conscience which discloses the truth of Being [4]. By reading this Heideggerian interpretation of Jung with Lacan and Zizek, Lacan’s schema can be understood in more detail. Zizek says “The resemblance of the depicted Lacanian scheme to a cross section of an eye is by no means accidental: objet a effectively functions as a rift in the closed circle of the psychic apparatus governed by the ‘pleasure principle,’ a rift which ‘derails’ it and forces it to ‘cast a look on the world,’ to take into account reality” ([3], p. 49). In other words, the analysand’s inauthentic understanding of the experience of a complex/objet petit a leads to a rift which “derails” “the analysand and this forces the analysand to” “cast a look on the world”: to discover the truth of Being. The experience of a complex/objet petit a consists of anxiety, conscience and guilt which is understood as a call of care from Dasein to itself [4]. This reveals another new meaning embedded in Lacan’s schema. This schema (Figure 1) resembles an eye and indicates that the analysand needs to “cast a look on the world” to remove the conspicuous obstructiveness and obstinance of complex/objet petit a to care for their being in the world. In other words, when the analysand experiences a “derailment” from a complex/objet petit a, “the world makes itself known in a new way as the Being of that which still lies before us and calls for our attending to it” ([5], p. 104). This is another way to understand the meaning of the eye in Lacan’s schema.

Zizek argues that “we should conceive Lacan’s thesis that objet a serves as a support to reality: access to what we call ‘reality’ is open to the subject via the rift in the closed circuit of the ‘pleasure principle,’ via the embarrassing intruder in its midst” ([3], p. 49). The objet a provides access to Dasein’s authenticity via the rift of a complex’s “pleasure principle”. However what should be added here is that although the objet a “serves as a support to reality” for Dasein to be authentic, Dasein needs to resolve to authentically listen to the call of conscience to exist in the truth of Being [4]. By being resolute, the analysand can authentically confront the objet petit a/complex and develop an interpreted understanding of new possibilities to expand the meaning of their being in the world. What Zizek calls “reality” can therefore be translated as “the unconscious” or the truth of Being. The “unconscious”, the truth of Being or “reality” is “an ‘excess,’ of a surplus which disturbs and blocks from within the autarky of the self-contained balance of the psychic apparatus” ([3], p. 49). The analysand experiences this excess when falling prey, which occurs when the analysand has inauthentically fled from the ontological truth of existence disclosed in the experience of angst, guilt and conscience [4]. Zizek argues this excess of “reality” is “the external necessity which forces the psychic apparatus to renounce the exclusive rule of the ‘pleasure principle’ is correlative to this inner stumbling block”([3], p. 49). This again shows that the objet petit a is identical to my phenomenological description of a complex. Through this experience of the objet petit a/complex, the analysand is forced to renounce the exclusive rule of the “pleasure principle” so that the transcendent function/individuation can take place by removing the “inner stumbling block” from being in the world [6]. Renouncing the “pleasure principle” means to go “through the wearisome” ([7], p. 223) by resolving to confront angst, guilt and conscience. An authentic understanding of the objet petit a/complex means to be resolute in the face of the experience of guilt, angst and conscience when “not being in the world” [4] has been disclosed by an obstinately obstructive world. By being authentically resolute, “the inner stumbling block” of the objet petit a/complex can be removed when the analysand does not become absorbed in only one of its possibilities and has instead interpreted new possibilities for being in the world. What this also reveals is that not renouncing the “pleasure principle” “can be described as inauthentically absorbing an entire human existence in only one of its human possibilities, which is perpetuated through an inauthentic turning away from angst, guilt and conscience through a being perfect projection” ([4], p. 973). This is the work of the narcissistic ego/I and this will be examined in more detail in my future research. I will now relate Jung’s transcendent function to Lacanian psychoanalysis.

2. Zizek and Jung’s Transcendent Function

The aim of Jung’s transcendent function is not to obtain what the analysand desires. The aim of the transcendent function is equivalent to “the pass” of Lacanian psychoanalysis [8]. Zizek says “Saying that the pass is the final moment of the analytical process in no way means that the impasse has finally been resolved (that the transfer has closed off the unconscious, for example), that its obstacles have been overcome. Rather, the pass is just the retroactive experience that the impasse itself was already its own “resolution”. In other words, the pass is exactly the same thing as the impasse (the impossibility of the sexual rapport), in the same way that as I said earlier—the synthesis is exactly the same thing as the antithesis. The only thing that changes is the subject’s position, his ‘perspective’”([8], p. 122). Jung’s transcendent function is successful when the analysand discovers the impasse as a ‘resolution’. In other words, the transcendent function or pass takes places when the analysand changes perspective to discover the impossibility of removing an impasse.

In the section “Subject as an answer of the Real’” of The Sublime Object of Ideology [9], Zizek says “the subject is not a question, it is as an answer, the answer of the Real to the question asked by the big Other, the symbolic order. It is not the subject which is asking the question; the subject is the void of the impossibility of answering the question of the Other”([9], p. 178). His statement links Jung’s transcendent function to a process of questioning that leads to the “Subject as an answer of the Real’” and highlights a convergence between Jung and Hegel since the “Subject as an answer of the Real’” is “The reversal operated by AK comes about when we realize that the field of the Other is already ‘closed’ in its very discord. In other words, because the subject is barred it must be posited as the correlate of the inert remainder that blocks its full symbolic realization, its full subjectivization: $◊a. This is why, in the matheme for Absolute Knowledge [SA], both terms must be barred, because it is the conjunction of $ and A”([8], p. 123). Jung’s transcendent function needs to lead to an experience of the barred subject ($) to be successful and this occurs when the analysand questions the objet petit a/complex. Zizek explains that “The real object of the question is what Plato, in the Symposium, called—through the mouth of Akibiades—agalma, the hidden treasure, the essential object in me which cannot be objectivated, dominated. (Lacan develops this concept in his unpublished Seminar VIII on Transference.)” ([9], p. 180)2.

3. Desire to Drive

Another way to explain this is to say the aim of Jung’s transcendent function is for the analysand to shift from desire to drive. Zizek explains this shift by claiming that “the Thing is first constructed as the inaccessible X around which my desire circulates, as the blind spot I want to see but simultaneously dread and avoid seeing, too strong for my eyes; then, in the shift towards drive, I (the subject) ‘make myself seen’ as the Thing—in a reflexive turn, I see myself as It, the traumatic object-Thing I didn’t want to see” ([10], p. 301). Jung’s transcendent function involves “making myself seen” as the Thing. Desire leads the analysand to the Thing but the Thing can only be experienced as an answer of the Real when desire shifts to drive. The objet petit a of desire is a sublime object or “’an object elevated to the dignity of the Thing’: the void of the Thing is not a void in reality, but, primarily, a void in the symbolic, and the sublime object is an object at the place of the failed word” ([11], p. 696). This highlights an important relationship between desire and drive, where desire is a way of relating to the Thing (void in the symbolic) through the imaginary object, whereas drive is a way of relating to the Thing through the Real.

Desire is a path to the barred subject $ as an answer of the Real when the analysand questions this desire (objet petit a) as a question of the Other. For Zizek “the subject is an answer of the Real (of the object, of the traumatic kernel) to the question of the Other” ([9], p. 180). Zizek also highlights that this questioning of the sublime object of desire hystericizes the analysand: “The question as such produces in its addressee an effect of shame and guilt, it divides, it hystericizes him, and this hystericization is the constitution of the subject: the status of the subject as such is hysterical” ([9], p. 204). In other words, the analysand becomes hysterical by questioning the sublime object of desire and this sublimity comes from the subject which is an answer of the Real. The subject is hysterical because questioning is necessary for the void of the Thing to be experienced ‘as the place of the failed word’ as an answer to the analysand’s questioning [12] and highlights that “The subject is constituted through his own division, splitting, as to the object in him; this object, this traumatic kernel, is the dimension that we have already named as that of a ‘death drive’, of a traumatic imbalance, a rooting out. Man as such is ‘nature sick unto death’, derailed, run off the rails through a fascination with a lethal Thing”([9], p. 181). The analysand needs to confront this traumatic kernel through the death drive for the analysand to remove the obstructiveness of a complex by discovering the possibilities missing from the readiness to hand [6]. When the analysand discovers the possibilities missing from the readiness-to-hand the analysand shifts from desire to drive through an experience of the barred subject as an answer of the Real. In other words, removing the obstructiveness of a complex/objet petit a results from reaching absolute knowledge ($A) where the analysand is barred from the imaginary objet petit a (a) and ‘makes myself seen’ as the Thing as a void in the symbolic (barred subject $ as an answer of the Real). This also elucidates why Heidegger emphasizes the importance of questioning when he says “the wonder of questioning must be experienced in carrying it out and must be made effective as an awakening and strengthening of the power to question” ([13], p. 10) and “in questioning reside the tempestuous advance that says ‘yes’ to what has not been mastered and the broadening out into ponderable, yet unexplored, realms. What reigns here is a selfsurpassing into something above ourselves. To question is to be liberated for what, while remaining concealed, is compelling” ([13], p. 10).

Zizek is also unknowingly instructive to explaining the process of Jung’s transcendent function when he says “This, perhaps, is the most succinct definition of aura: aura envelops an object when it occupies a void (hole) within the symbolic order”([11], p. 696). This is important for stage 1 of Jung’s transcendent function [6]. Jung says “First and foremost, we need the unconscious material” ([14], p. 283). This involves a retrieval of the meaning of a guilty mood from a complex from having-been and is can now be linked to the objet petit a. When explaining the transcendent function, Jung suggests a technique called active imagination, for conjuring unconscious material, where the symptom (guilty mood) provides a starting position to initiate the unification of opposites, “The patient would like to know what it is all for and how to gain relief. In the intensity of the emotional disturbance itself lies the value, the energy which he should have at his disposal in order to remedy the state of reduced adaptation” ([14], p. 289). Zizek’s description of objet petit a and my article on complexes [4] allows the acquisition of the meaning of the unconscious guilty mood to be better understood. The meaning of the unconscious guilty mood can be acquired when the analysand projects an understanding into having-been to discover regions of being in the world which are conspicuously experienced as obstructive, unready to hand and “not-being-at-home”. These regions of being in the world are where the analysand experiences the aura that “envelops an object when it occupies a void (hole) within the symbolic order” ([11], p. 696). The analysand can experience the aura of the objet petit a as obstructive, unready to hand and “not-being-at-home” because “what Lacan calls the objet a, the subject’s impossible-Real objectal counterpart, is precisely such an ‘imagined’ (fantasmatic, virtual) object which never positively existed in reality” ([11], p. 645). The aura of the objet petit a comes from the void in the symbolic order and the analysand will experience this void as obstructive, unready to hand and “not-being-at-home” if this void has not been discovered, or as Zizek has it, “Man as such is ‘nature sick unto death’, derailed, run off the rails through a fascination with a lethal Thing” ([9], p. 181). The analysand is fascinated with the aura of the objet petit a but the analysand will be “derailed, run off the rails” by the Thing until desire shifts to drive to discover the barred subject $ as an answer of the Real. This occurs when the analysand discovers the meaning of the unconscious complex and the missing possibilities from the ready-to-hand [4,6]. To discover the meaning of an unconscious complex is to change perspective to see how the objet petit a occupied a void within the symbolic order. This occurs when the analysand can remove the obstructive complex/objet petit a by discovering the void of the symbolic order where the subject is as an answer of the Real. This happens because the analysand has hysterically questioned the aura of a complex/objet petit a, to discover the missing possibilities from the readiness-to-hand until reaching “the place of the failed word”. The analysand discovers the meaning of an unconscious complex by changing “the error in perspective” which “consists in thinking that the end of the dialectical process consists in the subject finally obtaining what he was looking for. This is an error in perspective because the Hegelian solution is not that the subject will never be able to possess the thing that he was searching for, but that he already had it, in the form of its loss” ([8], p. 122). As a result, the analysand needs to move beyond the error in perspective of the aura of the objet petit a/complex, to the perspective of loss which is revealed through the void of the symbolic order or “the place of the failed word”. Just as Wiener ([15], p. 82) says the first woodcut is “a symbolic representation of the theory and practice of analysis and, metaphorically, the beginning of an analysis”, so too the aura of the objet petit a can also be seen to be represented in the first woodcut of the Rosarium Philosophorum [16], as the fluid substance in the mercurial fountain.

4. Objet Petit a and Jung’s Transcendent Function

This situates desire and the objet petit a as fundamental to the first stage of Jung’s transcendent function because it provides a path to the end of analysis where the analysand uncovers a loss which is the barred subject ($). The objet petit a is a fantasy “so that all its fantasmatic incarnations, from breast to voice and gaze, are metonymic figurations of the void, of nothing” ([11], p. 639). Zizek says “the true object-cause of desire is the void filled in by its fantasmatic incarnations”([11], p. 639) and so the aim of analysis and Jung’s transcendent function is to “traverse the fantasy” of desire and objet petit a. Traversing the fantasy removes the obstructiveness of a complex by discovering the missing possibilities from the readiness to hand to reveal the barred subject $ through loss or as an answer of the Real.

Zizek also refers to the objet petit a as tickling the subject (The Ticklish Subject, [10]). Zizek says the objet petit a which tickles the subject is “the parallax object. The standard definition of parallax is: the apparent displacement of an object (the shift of its position against a background), caused by a change in observational position that provides a new line of sight”([17], p. 17). This explains the relationship between the obstructiveness of a complex and the objet petit a which tickles the subject. The objet petit a tickles the subject with its aura and obstructiveness through its parallax or error in perspective. When the analysand traverses the fantasy and removes the obstructiveness of a complex with Jung’s transcendent function, the objet petit a no longer tickles the subject through its aura or obstructiveness. This occurs because the analysand has shifted its “observational position that provides a new line of sight”. The objet petit a no longer tickles the subject when the analysand reveals the void of the symbolic order or “the place of the failed word”. Zizek argues that “subject and object are inherently ‘mediated’, so that an ‘epistemological’ shift in the subject’s point of view always reflects an “ontological” shift in the object itself”([17], p. 17). This is another way of elucidating the shift involved in Jung’s transcendent function. The transcendent function allows a transition to takes place from being ‘tickled’ by the objet petit a/complex to removing the obstructive objet petit a/complex. This is a shift in perspective which occurs by discovering the void in the symbolic order which is the place of the analysand’s barred subjectivity ($). This is an experience of the Real which “is purely parallactic and, as such, nonsubstantial: is has no substantial density in itself, it is just a gap between two points of perspective, perceptible only in the shift from the one to the other”([17], p. 26). In other words the analysand needs to discover how the tickling “object embodies, gives material existence to the lack in the Other, to the constitutive inconsistency of the symbolic order” ([3], p. 22).

The analysand experiences the obstructiveness of a complex/objet petit a because “phantasy is the unique way each of us tries to finish with the Thing, to settle our score with impossible jouissance, which is to say, the way in which we use an imaginary construct in our attempt to escape the primordial impasse of the being of language, the impasse of the inconsistent Other, the hole at the heart of the Other” ([8], p. 153). This highlights that fantasy involves an imaginary understanding of the other instead of a Real understanding. Removing the obstructiveness of a complex equates to traversing the fantasy (of the imaginary I or ego) as the analysand discovers “the hole at the heart of the Other” where the word fails. A complex is “formed in the specular relation, and of being fundamentally in the service of the pleasure principle—that led Freud to the theoretical necessity of envisioning a beyond the pleasure principle” ([2], p. 10). Going beyond the pleasure principle of an imaginary relationship to other is necessary to remove the obstructiveness of a complex/objet petit a and “it is precisely in this that the subject function can be distinguished as not simply reducible to narcissism” ([2], p. 10).

5. Reading Jung with Heidegger, Reading Lacan with Hegel

My interpretation of Jung is assisted by Heidegger whereas Zizek’s interpretation of Lacan is assisted by Hegel. As a result, through my integration of Jung with Lacan my work can also integrate Hegel and Heidegger. For example, when clarifying the way the fantasy of objet petit a fills the hole in the symbolic order, Zizek explains why he uses Hegel to read Lacan by saying “What is concealed in the fascinating presence of this phantasmic construction? A hole, an empty space. It is possible to define this hole by undertaking the reading of Hegel with Lacan, which is to say against the background of the Lacanian problematic of the lack in the Other, the traumatic emptiness around which the signifying process articulates itself”([8], p. 2). Zizek adds to this by saying “From this perspective, Absolute Knowledge reveals itself to be the Hegelian name for what Lacan attempted to pin down with the term “the pass” [la passe], the final moment of the analytical process, the experience of the Lack in the Other. If, according to Lacan’s famous formulation, Sade gives us the truth of Kant, then Lacan himself could give us access to the fundamental matrix that gives the movement of the Hegelian dialectic its structure” ([8], p. 2). This highlights that Zizek equates absolute knowledge with the final moment of psychoanalytic treatment where the analysand experiences the lack in the Other. This is also what is required for Jung’s transcendent function to remove the obstructiveness of a complex [6]. When Jung is read with Lacan, the transcendent function can be understood to involve the retrieval of the fascinating presence of the objet petit a, and to discover the meaning of an unconscious complex by shifting the analysand’s perspective from desire to drive. This takes place by reaching Zizek’s interpretation of absolute knowledge which involves shifting the analysand’s perspective to see that the fantasy objet petit a, conceals a hole, an empty space which is the barred subject ($). The empty space comes from an experience of the lack in the Other and equates the lack in the Other with the place of the barred subject of the analysand. Penot, too, says the “subjectivating function implies the participation of at least two subjects. I would say that it is fundamentally and from the beginning an intersubjective experience” ([2], p. 18).

My work continues in the tradition of reading one philosopher with another to show a different perspective on the same phenomena. Zizek has read Hegel with Lacan, I have read Heidegger with Jung and now this current article applies my Heideggerian interpretation of Jung to a Zizekian interpretation of Lacan. Just as Zizek says “To my eyes, Lacan was fundamentally Hegelian, but did not know It” ([8], p. 3), my work shows that Jung and Heidegger were fundamentally Lacanian ‘but did not know it’. Zizek explains Lacan’s “Hegelianism is not to be found where we might expect it to be, in his overt references to Hegel, but rather in the final stage of his teachings, in the logic of the pas—tout, in the importance he placed on the Real, on the Lack in the Other” ([8], p. 3). Likewise, although Jung and Heidegger do not make overt references to Lacan, their writing is compatible.

6. Zizek and Nietzsche

Zizek also links Francis Bacon’s art to the objet petit a, noting that in his drawings “we find a (naked, usually) body accompanied by a weird dark stain-like formless form that seems to grow out of it, barely attached to it, as a kind of uncanny protuberance that the body can never fully recuperate or reintegrate, and which thereby destabilizes beyond repair the organic Whole of the body—this is what Lacan was aiming at with his notion of the lamella” ([18], p. 10; my emphasis). The key words in this segment of Zizek’s writing are dark stain, uncanny protuberance and destabilizes. There are a number of ways to link this to my Heideggerian interpretation of Jung but now I will relate it to my earlier work on Jung’s transcendent function as Nietzsche’s Will to Power [19]. Specifically Zizek’s description of the objet petit a, in Bacon’s art, is equivalent to Heidegger’s description of chaos in his interpretation of Nietzsche’s Will to Power. Heidegger says chaos “means the jumbled, the tangled, the pell-mell. Chaos means not only what is unordered but also entanglement in confusion, the jumble of something in shambles” ([19], p. 55). In my earlier work I related this to my Heideggerian interpretation of Jung’s writing on complexes. This led me to argue that the chaos of a complex urges, streams, and is dynamic, and the order of the chaos of a complex is covered, “whose law we do not descry straightaway” ([19], p. 55). I then argued that Jung’s transcendent function allows Dasein to resolutely schematize the law of the chaos to remove the obstructiveness of a complex from being in the world to preserve and enhance the life of Dasein. This can be seen to be describing the same phenomena in Francis Bacon’s drawing. The chaos of a complex is a dark stain which is an uncanny protuberance that destabilizes the analysand. As a result, this again highlights that my work on Jung’s transcendent function can be applied to Zizek’s writing on the objet petit a. If the analysand is inauthentic, they will misunderstand and encounter the obstructive chaos of the objet petit a/complex. The aim of psychoanalytic treatment is then to remove this impasse of the objet petit a/complex by retrieving the meaning of a guilty mood and possibilities missing from the readiness to hand [6]. This means the analysand is required to shift from desire to drive so the objet petit a does not tickle the subject as obstructive chaos (This is symbolically depicted on the cover of Returning to Jung with Heidegger as the sunlight of the drive allows the analysand to traverse their way through the obstructive chaos of the trees of desire [fantasy]).

The relation between the objet petit a and Nietzsche’s writing of the Will to Power is evident again when Zizek says “This forever lost excess of pure indestructible life is—in its guise as the objet a, the object-cause of desire—also what ‘eternalizes’ human desire, making it infinitely plastic and unsatisfiable (in contrast to instinctual needs)” ([11], p. 989). This clarifies that the Will to Power which Heidegger argues is eternal recurrence of the same [19] is intimately involved with the objet petit a. The analysand experiences the eternal aspect of objet petit a by shifting perspective from desire to drive (imaginary to Real). When this happens the analysand sees that the objet petit a/complex, is a phantasmic construction concealing “A hole, an empty space”([8], p. 2). This empty space appears when the analysand discovers the missing possibilities of the lack in the Other and this is an eternal lack in the Other which is experienced as an eternal recurrence of the same. The objet petit a/complex leads the analysand to the barred subject $ through the fantasy ($◊a) when the analysand changes perspective to see the lack in the Other which was concealed by the objet petit a/complex. Zizek confirms this as recent as 2016 when he says “the objet a is the strange object which is nothing but the inscription of the subject itself into the field of objects, in the guise of a stain which acquires form only when part of this field is anamorphically distorted by the subject’s desire” ([20], p. 188).

7. Fantasy and the Desire of the Other

Zizek then elaborates by saying “What we encounter in the very core of fantasy is the relationship to the desire of the Other, to the latter’s opacity: the desire staged in fantasy is not mine but the desire of the Other. Fantasy is a way for the subject to answer the question of what object he is in the eyes of the Other, in the Other’s desire—that is, what does the Other see in him, what role does he play in the Other’s desire? A child, for example, endeavours to dissolve, by means of his fantasy, the enigma of the role he plays as the medium of the interactions between his mother and his father, the enigma of how mother and father fight their battles and settle their accounts through him. In short, fantasy is the highest proof of the fact that the subject’s desire is the desire of the Other” ([21], p. 177). This explains and reiterates a number of things I have said. Zizek declares “Fantasy is a way for the subject to answer the question of what object he is in the eyes of the Other” and Lacan writes the formula for fantasy as ($◊a). This formula shows how “Fantasy is a way for the subject to answer the question of what object he is in the eyes of the Other”. In fantasy, the barred subject $ is covered by the imaginary objet petit a/complex. Fantasy covers the lack/desire of the Other through the imaginary “fullness” of objet petit a. When fantasy covers the lack/desire of the Other with the objet petit a/complex in this way, the analysand misrecognises his or her place within the symbolic order because the objet petit a/complex covers the place barred subject ($). This is what Lacan means when he says there is a “function of misrecognition that characterizes the ego in all the defensive structures so forcefully articulated by Anna Freud” ([22], p. 80). This imaginary relationship of a complex/objet petit a to the other through fantasy also involves “aggressiveness linked to the narcissistic relationship and to the structures of systematic misrecognition and objectification that characterize ego formation” ([22], p. 94).

To remove the obstructiveness of a complex/objet petit a, the analysand needs to go beyond an imaginary relationship to the other to discover the lack/desire of the Other or in Lacan’s words, beyond this imaginary relationship of the ego “language restores to it, in the universal, its function as subject” ([22], p. 76). This is achieved clinically with “speech to bring about change in the structure of the subject” ([23], p. 4). If the analysand does not go beyond an imaginary relationship to the other, they will experience the obstructiveness of a complex/objet petit a because fantasy conceals the Real of the lack/desire of the Other. Through Jung’s transcendent function as Will to Power and eternal recurrence of the same, the analysand can traverse the fantasy through a shift in perspective in relation to the complex/objet petit a. This happens when the analysand no longer desires the objet petit a, because the analysand’s new perspective sees that it is a fantasy. The analysand sees the objet petit a/complex as a fantasy by discovering the desire/lack of the Other and that is why “Objet a is simultaneously the pure lack, the void around which the desire turns and which, as such, causes the desire, and the imaginary element which conceals this void, renders it invisible by filling it out” ([21], p. 178).

8. Obsessional Neurosis

Zizek also uses Lacan’s theory of fantasy to explain obsessional neurosis, noting that “It is at this level that we have to locate the obsessional neurotic’s version of Cogito ergo sum: ‘What I think I am, that is, what I am in my own eyes, for myself, I also am for the Other, in the discourse of the Other, in my social-symbolic, intersubjective identity. The obsessional neurotic aims at complete control over what he is for the Other: he wants to prevent, by means of compulsive rituals, the Other’s desire from emerging in its radical heterogeneity, as incommensurable with what he thinks he is for himself” ([21], p. 177). Obsessional neurosis is an example of a complex where the imaginary fantasy of the objet petit a, which conceals the desire of the Other, leads to the experience of “not being at home” because of the obstructiveness of a complex. The obsessional will experience the obstructiveness of their complex/fantasy by not discovering the missing possibilities of the desire of the Other and this provides a rationale to define obsessional neurosis as pathological. The obsessional desires the possibility “What I think I am, that is, what I am in my own eyes, for myself, I also am for the Other, in the discourse of the Other, in my social-symbolic, intersubjective identity”. However this will lead to the obsessional’s obstructive being in the world because the obsessional has not discovered the missing possibilities [4] of the desire of the Other. Because these possibilities are undiscovered, the obsessional neurotic will experience the desire of the Other as an obstruction to their imaginary fantasy when the desire of the Other is encountered. When considered in this way, the obsessional has only an imaginary relationship to the other which does not engage with any of the meaning of the others subjectivity (symbolic and Real). The aim of psychoanalytic treatment in this case is for the analysand to engage with the other beyond the imaginary so the obsessional’s fantasy can be broken and the obstructiveness of a complex removed from being in the world.

Zizek summarises the pathology or inauthenticity of obsessional neurosis by saying “The key ingredient of obsessional neurosis is the conviction that the knot of reality is held together only through the subject’s compulsive activity: if the obsessive ritual is not properly performed, reality will disintegrate” ([21], p. 177). This shows that obsessional neurosis is a complex because of an inability to discover the missing possibilities from the readiness to hand. The obsessional must perform a compulsive ritual to ensure that the possibilities of the desire of the Other do not enter their “knot” of reality because if it does, the obsessional’s reality will “disintegrate”. “Disintegrate” is another way of saying “obstructiveness”. The obsessional’s reality/fantasy disintegrates when the obstructiveness of their complex is encountered through the desire of the Other.

9. Munch’s Scream

Zizek also refers to Lacan’s seminar on anxiety to elucidate the objet petit a. In this seminar “Lacan referred to Munch’s Scream in order to exemplify the status of the voice qua object. That is to say, the crucial feature of the painting is the fact that the scream is not heard” ([3], p. 116). Zizek argues “one could say that the scream ‘got stuck in the throat’: the voice qua object is precisely what is “stuck in the throat,” what cannot burst out, unchain itself and thus enter the dimension of subjectivity” ([3], p. 117). In this section I use the example of Munch’s Scream to relate a phenomenological interpretation of complexes to the objet petit a. First what I will say is that a complex obstructs the voice and throat in Munch’s Scream. The objet petit a/complex gets “stuck in the throat” because the analysand experiences the un-ready-to-hand, where the world of entities ready-to-hand becomes obstructive, which means the world “cannot be budged without the thing that is missing” ([5], p. 103). As a result, what should now be apparent from the introduction of Heidegger’s writing is that the experience of a disturbing complex is an important moment to the analysand. This experience not only indicates that the current way of existing is unsuitable because of the conspicuous obstructiveness of the world but it also indicates its obstinacy and need for attention (care) to remove this obstructiveness from being in the world for the analysand to find their voice and “unchain itself and thus enter the dimension of subjectivity”. The scream is not heard because the experience of the obstructiveness of a complex/objet petit a blocks speech because the analysand has not discovered an entity (possibilities) to be assigned or referred to being in the world. Possibilities are undiscovered and missing from the analysand’s world and therefore the world falls into unreadiness to hand which is experienced as a complex/objet petit a. Zizek says “Lacan determines the object small a as the bone which got stuck in the subject’s throat” ([3], p. 117) and this experience highlights that the analysand has discovered some regions of Being but has left others undiscovered. Heidegger says the readiness-to-hand of the world belongs to any region that has been discovered and “has the character of inconspicuous familiarity” ([5], p. 137). The conspicuous experience of the bone of the objet petit a/complex highlights that the analysand has encountered something unfamiliar and “The region itself becomes visible in a conspicuous manner only when one discovers the ready-to-hand circumspectively and does so in the deficient modes of concern.” ([5], p. 138). This ‘derailment’ or ‘inner stumbling block’ occurs because ‘one fails to find something in its place’ ([5], p. 138)”. The analysand has not gone beyond an imaginary relationship to the other or unchained themselves from the complex/objet petit a by discovering the missing possibilities from the readiness to hand and therefore the bone/voice is “stuck in the throat”. Munch’s Scream symbolises an analysand who has an inauthentic and imaginary understanding of the meaning of a complex/objet petit a. This is because the region where the complex/objet petit a is experienced is left undiscovered (imaginary) and thus remains conspicuously obstructive to being in the world.

Alternatively, when the analysand has an authentic/Real understanding of the meaning of a complex/objet petit a, the analysand can discover the unconscious involvements required for them to unconceal the barred subject/truth of Being and find their authentic home in the world. This is how we should understand Zizek when he says “To this silent scream which bears out the horror-stricken encounter with the real of enjoyment, one has to oppose the scream of release, of decision, of choice, the scream by means of which the unbearable tension finds an outlet: we so to speak ‘spit out the bone’ in the relief of vocalization”([3], p. 117). This is what happens when the analysand retrieves and understands the meaning of the complex/objet petit a through an interpretation of possibilities to remove its obstructiveness from being in the world [6]. This “spitting out the bone” can be explained in more detail when Heidegger’s work on truth is integrated. Heidegger says Being-true “means to-be-discovering” ([24], p. 201) and the being true means to let beings be seen in their unconcealment (discoveredness), taking them out of their concealment. As a result, the process of spitting out the bone (complex/objet petit a) can be understood in Heideggerian terms as taking Being/the subject out of concealment, which results in a new understanding of possibilities for being in the world when the truth of Being/the barred subject is authentically discovered. The analysand “finds an outlet” for “the scream of release” when the authentic/Real truth has been “wrested from beings. Beings are torn from concealment” ([24], p. 204)” and this allows the obstructiveness of a complex/objet petit a to be removed from being in the world. The analysand “spits out the bone” and finds their voice by retrieving “missing possibilities from the readiness to hand to remove the obstructiveness of a complex from being in the world” ([6], p. 91). Zizek elucidates this further when he says “the opposition of silent and vocalized screams coincides with that of enjoyment and Other: the silent scream attests to the subject’s clinging to enjoyment, to his/her unreadiness to exchange enjoyment (i.e., the object which gives body to it) for the Other, for the Law, for the paternal metaphor, whereas the vocalization as such corroborates that the choice is already made and that the subject finds himself/herself within the community” ([3], p. 118).

10. Particularity and Community

This can be examined in more detail by noting that “the opposition of silent and vocalized screams coincides” with the opposition of being authentic (Other) and inauthentic (enjoyment). The silent scream from the objet petit a/complex “stuck in the throat” coincides with the analysand’s imaginary/inauthentic understanding of the meaning of this experience which involves a projection of Being-perfect [4]. Being perfect is the analysand’s inauthentic understanding that understands themselves to have developed to the very apex of their potential and is coupled with closedness to other possibilities (e.g., imperfection, failure and guilt.) As a result, instead of authentically understanding the experience of a complex/objet petit a as the call of guilt from conscience which discloses the truth of the analysand’s “not being at home”, a Being-perfect projection resolutely flees facing the truth of guilt from falling prey and therefore lacks the discovery of new possibilities for being in the world.

Being-perfect is of form of “the subject’s clinging to enjoyment” because it “reveals something like a flight of Da-sein from itself as an authentic potentiality for being itself” ([24], p. 172). The analysand clings to the enjoyment of identifying with the Being-perfect ego. Jung explains that the genesis of a complex “arises from the clash between a requirement of adaptation and the individual’s constitutional inability to meet the challenge” ([25], p. 82) and Jung suggests that “Naturally, in these circumstances there is the greatest temptation simply to follow the power Instinct and to identify the ego with the self outright, in order to keep up the illusion of the ego’s mastery” ([7], p. 224). When this aspect of Jung’s writing is analysed phenomenologically, it can be appreciated that identifying with the ego is a symptom of the analysand’s “unreadiness to exchange enjoyment (i.e., the object which gives body to it) for the Other, for the Law, for the paternal metaphor”. Identifying with the ego means the analysand has fled from an authentic/Real understanding of the experience of a complex/objet petit a, to identify with an inauthentic familiar (imaginary) everyday being in the world. Identifying with the imaginary relationship to the other through the ego and the inability to adapt to life’s challenges can be phenomenologically described as fleeing into the average everyday familiarity with the world to tranquillize the angst, guilt and conscience of a complex/objet petit a. The analysand clings to enjoyment by fleeing into the familiarity of the “at-home” and avoids the truth of facing the “not-at home” ([5], p. 234) which is disclosed by the experience of a complex/objet petit a. By inauthentically understanding the experience of the complex/objet petit a, the analysand “does so by turning away from it in falling; in this turning-away, the ‘notat-home’ gets ‘dimmed down’” ([5], p. 234). By identifying with the imaginary ego and the “at home” of familiar enjoyment, the analysand flees to the “relief which comes with the supposed freedom of everydayness” ([5], p. 321).

Alternatively, if the analysand understands themselves authentically in the experience of a complex/objet petit a, the analysand can critically interpret their being-in-the-world to determine those unfamiliar and obstructive elements that have been neglected and so threaten the analysand’s care for being in the world. This is how the analysand exchanges enjoyment “for the Other, for the Law, for the paternal metaphor”. By falling prey to a complex/objet petit a which discloses an unfamiliar, absurd and meaningless world, the analysand encounters an obstinate and obstructive existence which calls the analysand forth to individuate “to its ownmost being-in-the-world, which as understanding, projects itself essentially upon possibilities” ([24], p. 176). Importantly, the positive nature of the experience of a complex/objet petit a can bring the analysand face to face with concealed authentic/Real possibilities which have the potential to appropriate the unready to hand and obstructive world which allows the subject to find “himself/herself within the community”. In other words, discovering possibilities involves using language through a symbolic relationship to the Other and “Using language, on the one hand it attempts to lead people to perception of the general structure that conditions all their reactions and decisions in life; on the other hand, it tries to lead them to perceive what makes them unique, their own particularity” ([23], p. 4). The obstructiveness of a complex/objet petit a, is a symptom. This obstructiveness indicates the analysand misrecognises “their own particularity” because of an imaginary relationship to the other through the ego.

To discover “their own particularity” “within the community” the analysand must understand the authentic/Real meaning of the experience of a complex/objet petit a as being the basis for not discovering possibilities to be assigned or referred to the analysand’s world. Possibilities are undiscovered and missing from the analysand’s world and thus the world falls into unreadiness to hand which is experienced as the ‘bone in the throat’ of a complex/objet petit a. When the analysand has an authentic/Real understanding of the meaning of a complex/objet petit a, they have the possibility of discovering the unconscious involvements required to unconceal the truth of Being (the Other, Law, paternal metaphor) to find their authentic/Real home in the world. For the analysand to exchange enjoyment for the Other, the Law, or the paternal metaphor, the analysand must free other beings for their own authentic possibilities. This occurs by letting these possibilities be involved by making room for them to be part of the analysand’s world in the region of the experience of the obstructive complex/objet petit a.

The analysand begins the process of ‘spitting out the bone in the throat’ by projecting its being-in-the-world upon possibilities. Interpretation of being-in-the-world is the development of possibilities projected in understanding. Through an interpretation of possibilities, the analysand can authentically free other beings for their own authentic possibilities by letting them be involved by making room for them. By projecting possibilities with interpretation, “innerworldly beings are discovered, that is, have come to be understood, we say that they have meaning” ([24], p. 142). This is how the analysand vocalises their scream by discovering the meaning of the Other, the Law or the paternal metaphor through this interpretation of possibilities. The analysand “finds himself/herself within the community” from this because discovering the meaning of the Other, the Law or the paternal metaphor modifies the experience of a complex/objet petit a in “both the way in which the ‘world’ is discovered and the way in which the Dasein-with of Others is disclosed.” ([5], p. 344). As a result, “The ‘world’ which is ready-to-hand does not become another one ‘in its content’, nor does the circle of Others get exchanged for a new one ; but both one’s Being towards the ready-to-hand understandingly and concernfully, and one’s solicitous Being with Others, are now given a definite character in terms of their ownmost potentiality-for-Beingtheir-Selves.” ([5], p. 344).

This explains how the analysand “finds himself/herself within the community” by exchanging enjoyment for the Other, the Law or the paternal metaphor. The analysand “finds himself/herself within the community” by authentically retrieving and letting the Other, the Law or the paternal metaphor be free for its involvement in the ready to hand which removes obstructiveness from being in the world by understanding the authentic/Real meaning of the complex/objet petit a. By understanding the authentic/Real meaning of a complex/objet petit a, the analysand “makes it possible to let the Others who are with it ‘be’ through solicitude which leaps forth and liberates.” ([5], p. 344). The analysand finds themselves with the community because they have “let others be” by discovering and vocalizing the meaning of the Other, the Law or the paternal metaphor through an interpretation of possibilities. This is also consistent with Jungian individuation. Jung says “I note that the individuation process is confused with the coming of the ego into consciousness and that the ego is in consequence identified with the self, Individuation is then nothing but ego-centredness, the self comprises infinitely more than a mere ego. It is as much one’s self, and all other selves, as the ego. Individuation does not shut one out from the world, but gathers the world to oneself.” ([7], p. 226). In other words, ego-centredness is what Zizek would equate with the “silent scream” from “the subject’s clinging to enjoyment”. On the other hand, individuation can be equated with “spitting out the bone” because enjoyment has been exchanged “for the Other, for the Law, for the paternal metaphor” which “does not shut one out from the world, but gathers the world to oneself” which allows the subject to find “himself/herself within the community”.

11. Fichte

Zizek also makes the most of Fichte’s philosophy to examine the objet petit a in more detail. Zizek argues that “Fichte was the first philosopher to focus on the uncanny contingency at the very heart of subjectivity” ([11], p. 149). Zizek explains that Fichte’s word for the objet petit a is Anstoss which “functions as the challenge (Aufforderung) compelling me to limit/ specify my freedom, that is, to accomplish the passage from the abstract egotistic freedom to concrete freedom within the rational ethical universe” ([11], p. 150). The Anstoss is clearly equivalent to the phenomena of a complex and objet petit a when Zizek says “It is important to bear in mind the two primary meanings of Anstoss in German: check, obstacle, hindrance, something that resists the boundless expansion of our striving; and an impetus or stimulus, something that incites our activity” ([11], p. 150). This is confirmed when Zizek says “If the Kantian Ding an sich corresponds to the Freudian-Lacanian Thing, Anstoss is closer to the objet petit a, to the primordial foreign body that ‘sticks in the throat’ of the subject, to the object-cause of desire that splits it up” ([11], p. 150). Therefore, a complex (Jung) and objet petit a (Lacan) are the same phenomena as Fichte’s “Anstoss as the non-assimilable foreign body that causes the subject’s division into the empty absolute subject and the finite determinate subject, limited by the non-I” ([11], p. 150). This also means that the experience of a complex/objet petit a as Anstoss thus designates the moment of the “run-in;” the hazardous knock, the encounter with the Real in the midst of the ideality of the absolute I: there is no subject without Anstoss, without the collision with an element of irreducible facticity and contingency—“the I is supposed to encounter within itself something foreign”: The point is thus to acknowledge “the presence, within the I itself, of a realm of irreducible otherness, of absolute contingency and incomprehensibility” ([11], p. 150).

This explains why the analysand inauthentically understands the experience of a complex/objet petit a “by turning away from it in falling; in this turning-away, the ‘not-at-home’ gets ‘dimmed down’” ([5], p. 234). The Anstoss is “the moment of the ‘run-in’ the hazardous knock, the encounter with the Real” which is the barred subject $ and is therefore an encounter with the truth of Dasein. The analysand is inauthentic by not understanding “the presence, within the I itself, of a realm of irreducible otherness, of absolute contingency and incomprehensibility”. Zizek explains this further: “In clear contrast to the Kantian noumenal Ding that affects our senses, Anstoss does not come from outside, it is stricto sensu ex-timate: a non-assimilable foreign body in the very core of the subject” ([11], p. 150). This means that the experience of a complex/objet petit a, is the “very core of the subject” and explains why the analysand who turns away from understanding this experience also flees the truth of its authentic self (the barred subject). Dasein is entrusted with and concerned about its being-in-the-world but can cover over its authentic/Real possibilities for care which remain unconscious or undiscovered. Dasein’s essence as being-in-the-world is care, but if an inauthentic/imaginary understanding of its Being is present, Dasein can be said to be “fleeing from it and of forgetting” ([24], p. 41) its authentic/Real Being which is disclosed in the experience of the obstructive Anstoss/complex/objet petit a.

The obstructive experience of a complex/objet petit a is important because “The Anstoss which awakens (what will have been) the subject out of its pre-subjective status is an Other, but not the Other of (reciprocal) intersubjectiity as Lacan put it much later: ethics is the dimension of the Real, the dimension in which imaginary and symbolic balances are disturbed” ([11], p. 163). The experience of the Real of the Anstoss/objet petit a disturbs and hinders daily life just in the same way Heidegger phenomenologically describes the world as unready to hand and when Jung says the ego is “frequently disturbed by strong feeling tones” ([4], p. 968) and “A situation threatening danger pushes aside the tranquil play of ideas and places in its stead a complex of other ideas of the strongest feeling-tone” ([4], p. 968). These examples all highlight the experience of the Real where “imaginary and symbolic balances are disturbed”. This experience is important because the aim of psychoanalytic treatment is for the analysand to become authentic through an encounter with the Real to awaken “the subject out of its pre-subjective status”.

Complexes and the objet petit a can be better understood when Zizek says the Anstoss is “an appearance without anything that appears, a nothing which appears as something’ This is what brings the Fichtean Anstoss uncannily close to the Lacanian objet petit a, the object-cause of desire, which is also a positivization of a lack, a stand-in for a void” ([11], p. 168). There are two important things to extract from this. First, because a complex and objet petit a are the same thing said differently and Zizek says the objet petit a is the “object-cause of desire”, it is important to understand that the experience of the obstructiveness of a complex comes from the analysand’s “object-cause of desire”. What this means is that desire is always involved whenever a complex is experienced. The second important thing to note from this extract is that the obstructiveness of a complex/objet petit a actually comes from a void. This is because, as Zizek says, the objet petit a, is “also a positivization of a lack, a stand-in for a void”. This void is not without significance because “here we come to the crucial point: the otherness, the ‘stranger in my very heart;’ which Fichte endeavored to discern under the name of Anstoss, is this ‘bone in the throat’ which prevents the direct expression of the subject (and which-since the “subject” is the failure of its own direct expression-is strictly correlative to the subject)” ([11], p. 175). With this, Zizek ties together a number of things. What this highlights is that the experience of a complex takes place when the analysand’s desire leads it to be obstructed by a void which is the barred subject ($). In other words, a complex is experienced when the analysand’s desire leads to a void which is a “’bone in the throat’ which prevents the direct expression of the subject”. Ultimately, the aim of psychoanalytic treatment is “to grasp this inherent impediment in its positive dimension: true, the objet a prevents the circle of pleasure from closing, it introduces an irreducible displeasure, but the psychic apparatus finds a sort of perverse pleasure in this displeasure itself, in the neverending, repeated circulation around the unattainable, always missed object” ([3], p. 48).

12. Death, Drive

This is the aim of psychoanalytic treatment because it “allows the obstructiveness of a complex to be removed from being in the world and this provides Dasein the understanding to authentically care for being in the world” [4,6]. The end of psychoanalytic treatment requires the analysand to find “a sort of perverse pleasure in this displeasure itself, in the neverending, repeated circulation around the unattainable, always missed object” because this removes the analysand’s guilty mood from having-been and the obstructiveness of a complex/objet petit a from being in the world [6]. Zizek says “The Lacanian name for this “pleasure in pain” is of course enjoyment (jouissance), and the circular movement which finds satisfaction in failing again and again to attain the object, the movement whose true aim coincides therefore with its very path toward the goal, is the Freudian drive” ([3], p. 48). With this, Lacan’s concepts of jouissance and drive find their connection to Jung and Heidegger. What this adds to my earlier work on Jung’s transcendent function [6] is the observation that the obstructiveness of a complex is removed from being in the world through the drive. The drive is necessary because the analysand’s desire leads to a void which is a “’bone in the throat’ which prevents the direct expression/symbolization of the subject ($). In other words, Jung’s transcendent function involves the analysand retrieving the obstruction of a complex/objet petit a so the analysand can discover the missing possibility of the impossibility of the readiness to hand which is the impossibility of their desire [26].

This is how the ontological meaning of death should be conceived in Heidegger’s philosophy. The analysand needs to authentically discover the impossibility of their desire to remove the obstructiveness of a complex/objet petit a, and this is achieved through the death drive. Heidegger explains “We have conceived death existentially as what we have characterized as the possibility of the impossibility of existence” ([24], p. 283) and this ontological explanation needs to be understood in relation to the Freudian/Lacanian drive. The drive is the discovery of the impossibility of a desire because it is a “neverending, repeated circulation around the unattainable, always missed object”. This discovery involves the death of attaining the impossible desire and changes into a “circular movement which finds satisfaction in failing again and again to attain the object”. The possibility of attaining this desire provided the analysand with an imaginary and symbolic identity and therefore when the possibility of this desire dies (discovered as impossible), the analysand “simultaneously loses the Being of the there” ([24], p. 221). This loss of Being-there needs to be understood ontologically not physically. Dasein does not physically die when the impossibility of a desire is discovered through the death drive. Dasein dies ontologically when this happens where “Death is a possibility-of-Being which Dasein itself has to take over in every case. With death, Dasein stands before itself in its ownmost potentiality-for-Being. This is a possibility in which the issue is nothing less than Dasein’s Being-in-the-world. Its death is the possibility of no-longer being-able-to-be-there. If Dasein stands before itself as this possibility, it has been fully assigned to its ownmost potentiality-for-Being” ([5], p. 294). In other words, the death of the analysand’s impossible desire through the drive brings the analysand to stand “before itself in its ownmost potentiality-for-Being”([24], p. 232). This means that “Becoming free for one’s own death in anticipation frees one from one’s lostness in chance possibilities urging themselves upon us, so that the factical possibilities lying before the possibility not-to-be-bypassed can first be authentically understood and chosen” ([24], p. 243). Dasein discovers itself authentically when the analysand’s impossible desire dies through the drive because the drive “frees one from one’s lostness in chance possibilities urging themselves upon us” ([24], p. 243). The analysand’s authenticity from discovering the impossibility of a desire through the death drive is reflected in its experience of being in the world. When this happens, the obstructiveness of a complex/objet petit a, from the analysand’s impossible desire is removed from being in the world and this shows that “Care is Being-towards-death” ([24], p. 303). The death of the analysand’s impossible desire removes the obstructiveness of a complex/objet petit a from being in the world because “the revelation of this impossibility means to let the possibility of an authentic potentiality-of-being shine forth” ([24], p. 315). The analysand’s discovery of an impossible desire “reveals the nullity of what can be taken care of, that is, the impossibility of projecting oneself upon a potentiality-of-being primarily based upon what is taken care of”([24], p. 315). When this happens the analysand experiences Jung’s transcendent function because they have retrieved the missing possibilities from the readiness to hand and this allows the complex to be unified with the ego to widen consciousness [6].

When this occurs, the analysand “spits out the bone” because enjoyment has been exchanged “for the Other, for the Law, for the paternal metaphor” which “does not shut one out from the world, but gathers the world to oneself” which allows the subject to find “himself/herself within the community”. This is possible because the analysand discovers it’s authentic/Real ‘being at home in the world’ when an impossible desire has been removed through the death drive. Heidegger highlights this by saying “Death does not just ‘belong’ to one’s own Dasein in an undifferentiated way; death lays claim to it as an individual Dasein. The non-relational character of death, as understood in anticipation, individualizes Dasein down to itself. This individualizing is a way in which the ‘there’ is disclosed for existence” ([24], p. 243). The analysand’s individual “there” is disclosed through the death drive of an impossible desire when enjoyment has been exchanged “for the Other, for the Law, for the paternal metaphor”. The analysand understands themselves and others authentically when the impossibility of the possibility of a desire has been discovered and this explains why the obstructiveness of a complex/objet petit a is no longer experienced and this is why “Care is Being-towards-death”.

This can be understood better when Zizek says our understanding of the world “is by definition always inconsistent, full of lacunae, which the subject must somehow fill in to create a minimally consistent Whole of a world-and the function of imagination is precisely to fill in these gaps” ([11], p. 176). Zizek says, in imagination “the subject’s void is present[ifi]ed as an [imagined] object)” ([11], p. 176). This highlights that the analysand’s impossible desire fills the void of the place of the barred subject $ with the objet petit a/complex through imagination. This also explains that the analysand’s desire is impossible when the void of the barred subject $ is filled with objet petit a/complex through imagination. This desire constitutes the analysand’s inauthenticity and that is why psychoanalytic treatment needs to bring the analysand “face to face with the absolute impossibility of existence” ([5], p. 299). The analysand needs to discover “The nullity by which Dasein’s Being is dominated primordially through and through” which “is revealed to Dasein itself in authentic Being-towards-death” ([5], p. 299). This is how the obstructiveness of a complex/objet petit a is removed from being in the world through the death drive when the analysand discovers “a certain curvature of the space itself which causes us to make a bend precisely when we want to get directly at the object” ([3], p. 48). The analysand needs to discover that “the objet a is not a positive entity existing in space, it is ultimately nothing but” ([3], p. 48) the analysand’s imagination of the possibility of a desire. Psychoanalysis involves moving the analysand away from filling in the void with the objet petit a/complex to discover the “possibility of the impossibility of existence, that is, as the absolute nothingness of Da-sein” ([24], p. 283).

Heidegger also says “that proximally and for the most part Dasein covers up its ownmost Being-towards-death, fleeing in the face of it” ([5], p. 295). The analysand experiences the obstructiveness of a complex/objet petit a when the analysand does not exist as “Being-towards-death” of an impossible desire. The analysand experiences this obstructiveness because the analysand has not freed “one from one’s lostness in chance possibilities urging themselves upon us” or discovered “the nullity of what can be taken care of, that is, the impossibility of projecting oneself upon a potentiality-of-being primarily based upon what is taken care of” ([24], p. 315). Successful psychoanalytic treatment requires the analysand to stop “fleeing in the face of one’s own most Being-towards-death” which is “a constant tranquillisation about death” ([24], p. 235). This allows the analysand to discover the impossibility of the possibility of a desire [26] and to find “a sort of perverse pleasure in this displeasure itself, to renounce the exclusive rule of the ‘pleasure principle’” ([3], p. 49). Although the death of the analysand’s impossible desire “introduces an irreducible displeasure”, “The revealing of this impossibility, however, signifies that one is letting the possibility of an authentic potentiality-for Being be lit up” ([5], p. 393).

Zizek explains “The Lacanian name for this “pleasure in pain” is of course enjoyment (jouissance)” ([3], p. 48) and this highlights its important role for the obstructiveness of the objet petit a/complex to be removed from being in the world and confirms its connection to an “authentic Being towards the possibility which we have characterized as Dasein’s utter impossibility” ([5], p. 378). In other words, removing the obstructiveness of a complex/objet petit a through the death drive “means that the minimal emptying of subject, the reduction of its reality (of its ‘thingness’), is constitutive of subjectivity: the subject is caught in its loop because it is not-All, finite, lacking, because a loss of-reality is co-substantial with it, and Anstoss is the positivization of this gap” ([11], p. 175). In other words, the aim of psychoanalytic treatment is for the analysand to empty Anstoss from the place of the void of the subject and when this happens the analysand removes or traverses the obstructiveness of this “bone in the throat”. The bone in the throat of the objet petit a/complex “is an object which is a direct counterpoint to the subject and, as such, gives body to a lack” ([27], p. 180). The experience of the obstructiveness of a complex/objet petit a indicates the impossibility of a desire has not been discovered because the analysand covers the truth of the void of the barred subject $ and “this paradoxical conjunction is designated by Lacan’s matheme of fantasy: $◊a” ([27], p. 180).

Zizek again reveals the compatibility of his work with my work when he says “The difference between subject and object can also be expressed as the difference between the two corresponding verbs, to subject (submit) oneself and to object (protest, oppose, create an obstacle)” ([17], p. 17). Psychoanalytic treatment helps the subject, submit to the object instead of being opposed/obstructed by it. Zizek explains this aim of psychoanalysis by saying “The subject’s elementary, founding, gesture is to subject itself—voluntarily, of course: as both Wagner and Nietzsche, those two great opponents, were well aware, the highest act of freedom is the display of amor fati, the act of freely assuming what is necessary anyway”([17], p. 17). Psychoanalysis helps the analysand reach amor fati by “submitting oneself to the inevitable” and this is achieved by traversing the complex/objet petit a “which moves, annoys, disturbs, traumatizes us (subjects)”([17], p. 17). In other words, psychoanalysis uses Jung’s transcendent function to guide the analysand to remove the obstructiveness of a complex/objet petit a which “at its most radical the object is that which objects, that which disturbs the smooth running of things” ([17], p. 17). This is why Jung also says “It is the man without amor fati who is the neurotic; he, truly, has missed his vocation” ([28], p. 308).

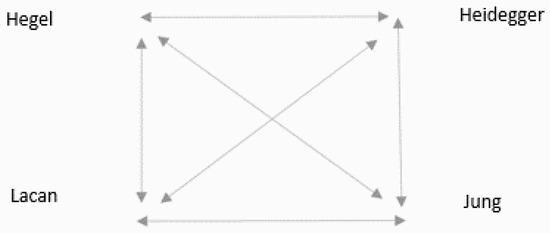

13. Holbein

Zizek also uses Holbein’s painting Ambassadors to describe the phenomena of objet petit a. He does this by distinguishing “between objet petit a as the cause of desire and the object of desire: while the object of desire is simply the desired object, the cause of desire is the feature on whose account we desire the object, some detail or tic of which we are usually unaware, and sometimes even misperceive it as an obstacle, in spite of which we desire the object” ([29], p. 67). This is important because it provides a more detailed and nuanced understanding of complexes which is important for Jung’s transcendent function. The obstructiveness of a complex comes from the objet petit a, which comes from the object of desire. In my article on Nietzsche’s Will to Power [19], I explain that a complex is experienced as chaos and this is equivalent to “The status of this object-cause of desire is that of an anamorphosis. A part of the picture which, looked at from straight in front, appears as a meaningless blotch takes on the contours of a known object when we shift our position and look at the picture from an angle” ([29], p. 68). A complex is experienced as chaos or a “meaningless blotch” from the perspective of desire. When the analysand shifts to the perspective of drive “the object-cause of desire is something that, viewed from in front, is nothing at all, just a void” ([29], p. 68). As a result, the object of desire is only desired through the complex when objet petit a “acquires the contours of something only when viewed at a slant” ([29], p. 68). The objet petit a has this effect when the analysand has not gone beyond an imaginary relationship to the object of desire. When the analysand has not removed the obstructiveness of a complex, the objet petit a will be experienced as “an entity that has no substantial consistency, which in itself is ‘nothing but confusion’, and which acquires a definite shape only when looked at from a standpoint slanted by the subject’s desires and fears—as such, as a mere ‘shadow of what it is not’” ([29], p. 69). The experience of the chaos and obstructiveness of a complex indicates that the analysand has yet to reveal the barred subject $ hidden by the objet petit a since “Objet a is the strange object that is nothing but the inscription of the subject itself in the field of objects, in the guise of a blotch that takes shape only when part of this field is anamorphically distorted by the subject’s desire” ([29], p. 69). Zizek uses Holbein’s Ambassadors painting (Figure 2) to add a visual layer/perspective to his description of objet petit a by saying “the most famous anamorphosis in the history of painting, Holbein’s Ambassadors, concerns death: when we look from the proper lateral angle at the anamorphically extended blotch in the lower part of the painting, set amongst objects of human vanity, it reveals itself as a skull” ([29], p. 69). Zizek importantly notes the death symbolism of this painting and this is important because the analysand needs to pass through the death drive to remove the obstructiveness of a complex/objet petit a (symbolised by the skull). Holbein’s painting is another way of highlighting that discovering the meaning of a guilty mood from an unconscious obstructive complex [6] is to shift perspectives from desire to drive. This involves the death of the fantasy of objet petit a by discovering the missing possibilities from the readiness to hand to reveal the void of the barred subject.

Figure 2.

Holbein’s Ambassadors [30].

The objet petit a is fascinating and desired because it covers the place of the barred subject (Dasein) and because it can lead the analysand to ground the barred subject (Dasein) through “the knowledge of the event, by way of the grounding (as Da-sein) of the essence of truth” ([13], p. 13). The barred subject is discovered at the place of “the void in the Other (the symbolic order), the void designated, in Lacan, by the German word das Ding, the Thing, the pure substance of enjoyment resisting symbolization” ([3], p. 8). The objet petit a/complex covers the Thing when the analysand has not gone beyond an imaginary relationship to the objet petit a/complex. An imaginary relationship to the objet petit a results in a complex disrupting the analysand’s being in the world and the experience of anxiety, guilt and the call of conscience. This phenomena is described by Zizek when he articulates the experience of the objet petit a “as the spot disturbing the picture, as a kind of blot on the white marble surface of the statue” ([3], p. 8). This experience is important for the analysand because “in the Lacanian perspective, the subject is strictly correlative to this stain on the picture. The only proof we have that the picture we are looking at is subjectified is not meaningful signs in it but rather the presence of some meaningless stain disturbing its harmony” ([3], p. 8). The analysand will continue to experience “not being at home in the world” as long as the analysand does not go beyond an imaginary relationship to this “meaningless stain disturbing its harmony”.

Zizek not only highlights the connection between Hegel and Lacan but also anticipates the connection to my phenomenological interpretation of complexes when he says “Does not the proposition ‘the Spirit is a bone’—this equation of two absolutely incompatible terms, pure negative movement of the subject and the total inertia of a rigid object—offer us something like a Hegelian version of the Lacanian formula of fantasy: $◊a?” ([9], p. 208). When Hegel says “the spirit is a bone” and Lacan writes his formula of fantasy as $◊a, they are describing the same experience as the obstructiveness of a complex. By aligning Zizek with my work in this way, I can show how a Heideggerian interpretation of Jung can develop the projects and understanding of both Hegel and Lacan. Zizek says “The bone, the skull, is thus an object which, by means of its presence, fills out the void, the impossibility of the signifying representation of the subject. In Lacanian terms it is the objectification of a certain lack: a Thing occupies the place where the signifier is lacking; the fantasy-object fills out the lack in the Other (the signifier’s order). The inert object of phrenology (the skullbone) is nothing but a positive form of certain failure: it embodies, literally ‘gives body’ to, the ultimate failure of the signifying representation of the subject” ([9], p. 208). When Hegel says “the spirit is a bone”, he is describing the phenomena of the obstructiveness of a complex as a path to the spirit. Spirit is experienced as a bone when the analysand has an imaginary relationship to the lack in the Other. In other words, a complex which can be described as a “bone”, is experienced when the analysand has not discovered the lack in the Other because the fantasy of objet petit a covers the “ultimate failure of the signifying representation of the subject”. Desire is desire for something negative/lacking (the Thing) but is misrecognised as objet petit a as something positive. This clarifies that Jung’s transcendent function aims to convert “this lack of the signifier into the signifier of the lack; from Lacanian theory we know that the signifier of this conversion, by means of which lack as such is symbolized, is the phallus” ([9], p. 209). In other words, the analysand desires to discover the signifier for the objet petit a but the objet petit a is an imaginary positivity of a void (fantasy). As a result, the analysand needs to shift perspectives to convert the lack of a signifier into the signifier of lack, and this space of the phallus (lack in the Other) is the barred subject $.