Indigenous ExtrACTIVISM in Boreal Canada: Colonial Legacies, Contemporary Struggles and Sovereign Futures

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Origins

3. Challenges

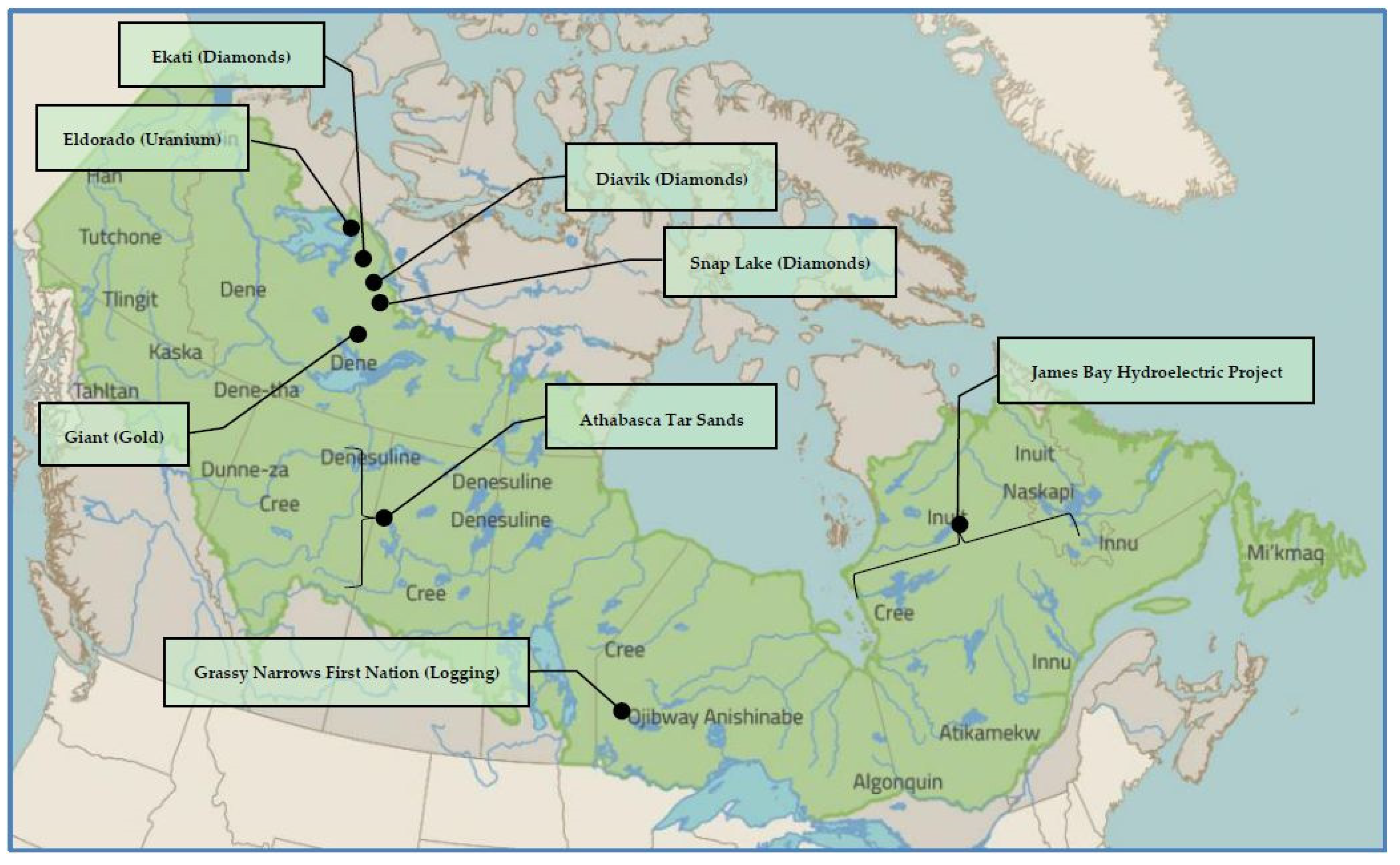

4. Cases

4.1. As Long As the Rivers Run?

4.2. Every Available Log

4.3. Mining the North

4.4. The Most Destructive Project on Earth

5. Conclusions

Extraction and assimilation go together. Colonialism and capitalism are based on extracting and assimilating...The act of extraction removes all of the relationships that give whatever is being extracted meaning. Extracting is taking. Actually, extracting is stealing—it is taking without consent, without thought, care or even knowledge of the impacts that extraction has on the other living things in that environment. That’s always been a part of colonialism and conquest. Colonialism has always extracted the indigenous—extraction of indigenous knowledge, indigenous women, indigenous peoples.[68]

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- J. David Henry. Canada's Boreal Forest. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Alberto Acosta. “Extractivism and Neoextractivism: Two Sides of the Same Curse.” In Beyond Development: Alternative Visions from Latin America. Edited by Miriam Lang and Dunia Mokrani. Amsterdam: Transnational Institute, 2013, pp. 61–86. [Google Scholar]

- Henry Veltmeyer, and James Petras. The New Extractivism: A Post-Neoliberal Development Model or Imperialism of the Twenty-First Century. London: Zed Books, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brian J. Burke. “Transforming Power in Amazonian Extractivism: Historical Exploitation, Contemporary ‘Fair Trade’, and New Possibilities for Indigenous Cooperative and Conservation.” Journal of Political Ecology 19 (2012): 115–26. [Google Scholar]

- Al Gedicks. The New Resource Wars: Native and Environmental Struggles against Multinational Corporations. Boston: South End Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Anna J. Willow. “Conceiving Kakipitatapitmok: The Political Landscape of Anishinaabe Anti-Clearcutting Activism.” American Anthropologist 13 (2011): 262–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbara Bender, and Margaret Wiener, eds. Contested Landscapes: Movement, Exile, and Place. Berg: Oxford, 2001.

- Veronica Strang. Uncommon Ground: Cultural Landscapes and Environmental Values. Berg: Oxford, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Boreal Songbird Initiative. “Indigenous Communities in Canada’s Boreal Forest.” Available online: http://www.borealbirds.org/aboriginal-communities-canada-boreal-forest (accessed on 30 July 2015).

- Naomi Klein. “Capitalism vs. the Climate.” The Nation. 9 November 2011. Available online: http://www.thenation.com/article/capitalism-vs-climate/ (accessed on 3 July 2015).

- Shepard Krech. The Ecological Indian: Myth and History. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Anna J. Willow. “Collaborative Conservation and Contexts of Resistance: New (and Enduring) Strategies for Survival.” American Indian Culture and Research Journal 39 (2015): 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana Powell. “The Rainbow is Our Sovereignty: Rethinking the Politics of Energy on the Navajo Nation.” Journal of Political Ecology 22 (2015): 53–78. [Google Scholar]

- Taiaiake Alfred, and Jeff Corntassel. “Being Indigenous: Resurgences against Contemporary Colonialism.” Government and Opposition 40 (2005): 597–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anna J. Willow. “Cultivating Common Ground: Cultural Revitalization in Anishinaabe and Anthropological Discourse.” American Indian Quarterly 34 (2010): 33–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devon A. Mihesuah, ed. Natives and Academics: Researching and Writing about American Indians. Lincoln: Bison Books, 1998.

- Luke Eric Lassiter. The Chicago Guide to Collaborative Ethnography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick Wolfe. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” Journal of Genocide Research 8 (2006): 387–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennifer Huseman, and Damien Short. “‘A Slow Industrial Genocide’: Tar Sands and the Indigenous Peoples of Northern Alberta.” The International Journal of Human Rights 16 (2012): 216–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory Hooks, and Chad L. Smith. “The Treadmill of Destruction: National Sacrifice Areas and Native Americans.” American Sociological Review 69 (2004): 558–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas Homer-Dixon. “The Tar Sands Disaster.” New York Times. 31 March 2013. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/01/opinion/the-tar-sands-disaster.html?_r=0 (accessed on 19 July 2015).

- Andrew Nikiforuk. Tar Sands: Dirty Oil and the Future of a Continent. Vancouver: Greystone Books, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shauna Morgan. “The True Price of a Resource Economy in Canada’s North.” World Policy Journal. 28 January 2015. Available online: http://www.pembina.org/op-ed/the-true-price-of-a-resource-economy-in-canadas-north (accessed on 6 July 2015).

- Anna J. Willow. “Doing Sovereignty in Native North America: Anishinaabe Counter-Mapping and the Struggle for Land-Based Self-Determination.” Human Ecology: An Interdisciplinary Journal 41 (2013): 871–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Peter Brosius. “Prior Transcripts, Divergent Paths: Resistance and Acquiescence to Logging in Sarawak, East Malaysia.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 39 (1997): 468–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beth A. Conklin, and Laura R. Graham. “The Shifting Middle Ground: Amazonian Indians and Eco-Politics.” American Anthropologist 97 (1995): 695–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William H. Fisher. “Megadevelopment, Environmentalism, and Resistance: The Institutional Context of Kayapó Indigenous Politics in Central Brazil.” Human Organization 53 (1994): 220–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amazon Watch. “Brazil’s Belo Monte Dam: Sacrificing the Amazon and its Peoples for Dirty Energy.” Available online: http://amazonwatch.org/work/belo-monte-dam (accessed on 16 December 2015).

- Robert Boos. “Native American Tribes Unite to Fight the Keystone Pipeline and Government ‘Disrespect’.” In Public Radio International; 19 February 2015. Available online: http://www.pri.org/stories/2015-02-19/native-american-tribes-unite-fight-keystone-pipeline-and-government-disrespect (accessed on 16 December 2015). [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D. Hall, and James V. Fenelon. Indigenous Peoples and Globalization: Resistance and Revitalization. Boulder: Paradigm Publishers, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Frank Quinn. “As Long as the Rivers Run: The Impacts of Corporate Water Development on Native Communities in Canada.” The Canadian Journal of Native Studies 11 (1991): 137–54. [Google Scholar]

- Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. “Pre-1975 Treaties in Canada.” Available online: http://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100032297/1100100032309 (accessed on 4 July 2015).

- James Rodger Miller. Compact, Contract, Covenant: Aboriginal Treaty-Making in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Michael Asch. On Being Here To Stay: Treaties and Aboriginal Rights in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- James E. Windsor, and J. Alistair Mcvey. “Annihilation of Both Place and Sense of Place: The Experience of the Cheslatta T’En Canadian First Nation within the Context of Large-scale Environmental Projects.” The Geographical Journal 171 (2005): 146–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natural Resources Canada. “About Electricity.” Available online: https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/energy/electricity-infrastructure/about-electricity/7359 (accessed on 9 July 2015).

- Environment Canada. “Dams and Diversions.” Available online: http://www.ec.gc.ca/eau-water/default.asp?lang=En&n=9D404A01-1 (accessed on 16 July 2015).

- Ronald Niezen. Defending the Land: Sovereignty and Forest Life in James Bay Cree Society. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Matthew Coon Come. “Survival in the Context of Mega-Resource Development: Experiences of the James Bay Crees and the First Nations of Canada.” In In the Way of Development. Edited by Mario Blaser, Harvey A. Feit and Glenn McRae. London: Zed Books, 2004, pp. 153–65. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce Richardson. Strangers Devour the Land. White River Junction: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ronald Niezen. “Power and Dignity: The Social Consequences of Hydro-electric Development for the James Bay Cree.” Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology 30 (1993): 510–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brian Craik. “The Importance of Working Together: Exclusions, Conflicts and Participation in James Bay, Quebec.” In In the Way of Development. Edited by Mario Blaser, Harvey A. Feit and Glenn McRae. London: Zed Books, 2004, pp. 166–86. [Google Scholar]

- Grand Council of the Crees. “Critical Issues: Pais des Braves.” Available online: http://www.gcc.ca/issues/paixdesbraves.php (accessed on 16 July 2015).

- Caroline Desbiens. “Producing North and South: A Political Geography of Hydro Development in Québec.” The Canadian Geographer 48 (2004): 101–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USEPA. “Terms and Acronyms: Clear Cut. ” Available online: https://iaspub.epa.gov/sor_internet/registry/termreg/searchandretrieve/termsandacronyms/search.do?search=&term=clear%20cut&matchCriteria=Contains&checkedAcronym=true&checkedTerm=true&hasDefinitions=false (accessed on 21 July 2015).

- Andrew Park, Chris Henschel, Ben Kuttner, and Gillian McEachern. A Cut Above: A Look at Alternatives to Clearcutting in the Boreal Forest. Toronto: Wildlands League, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Neil Osborne, and Lindsay O’Reilly. “Canada’s Boreal Forest.” Canadian Geographic. Available online: http://www.canadiangeographic.ca/magazine/jf04/indepth/justthefacts.asp (accessed on 21 July 2015).

- Tom Knudson. “State of Denial.” Sacramento Bee, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Anna J. Willow. Strong Hearts, Native Lands: The Cultural and Political Landscape of Anishinaabe Anti-Clearcutting Activism. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Canada Federal Government. (1871–1874) 1966; Treaty No. 3 Between Her Majesty The Queen and the Saulteaux Tribe of Ojibbeway Indians At The Northwest Angle On The Lake of the Woods With Adhesions; Ottawa: Queens Printer.

- Anna J. Willow. “Re(con)figuring Alliances: Place Membership, Environmental Justice, and the Remaking of Indigenous-Environmentalist Relationships in Canada's Boreal Forest.” Human Organization 71 (2012): 371–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raveena Aulakh. “Ontario Gives Green Light to Clear-cutting at Grassy Narrows.” Caledon Enterprise. 29 December 2014. Available online: http://www.caledonenterprise.com/news-story/5235322-ontario-gives-green-light-to-clear-cutting-at-grassy-narrows/ (accessed on 22 July 22 2015).

- David C. Natcher, and Clifford G. Hickey. “Putting the Community Back into Community-Based Resource Management: A Criteria and Indicators Approach to Sustainability.” Human Organization 61 (2002): 350–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innu Nation and Newfoundland and Labrador (Provincial Department of Forest Resources and Agrifoods). Forest Ecosystem Strategy Plan for Forest Management District 19 Labrador/Nitassinan; 2003. Available online: http://www.env.gov.nl.ca/env/env_assessment/projects/y2003/1062/text.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2016).

- Ellen Bielawski. Rogue Diamonds: Northern Riches on Dene Land. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Michael Gates. “Klondike Gold Rush.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. 2009. Available online: http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/klondike-gold-rush/ (accessed on 27 July 2015).

- Arn Keeling, and John Sandlos. “Environmental Justice Goes Underground? Historical Notes from Canada’s Northern Mining Frontier.” Environmental Justice 2 (2009): 117–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward Churchill, and Winona LaDuke. “Native America: The Political Economy of Radioactive Colonialism.” Critical Sociology 13 (1986): 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginger Gibson, and Jason Klinck. “Canada’s Resilient North: The Impact of Mining on Aboriginal Communities.” Pimatisiwn: A Journal of Aboriginal and Indigenous Community Health 3 (2005): 115–39. [Google Scholar]

- Rebecca Hall. “Diamond Mining in Canada’s Northwest Territories: A Colonial Continuity.” Antipode 45 (2013): 376–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher Hatch, and Matt Price. Canada’s Toxic Tar Sands: The Most Destructive Project on Earth. Toronto: Environmental Defense, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Phillippe Le Billon, and Angela Carter. “Securing Alberta’s Tar Sands: Resistance and Criminalization of a New Energy Frontier.” In Natural Resources and Social Conflict: Towards Critical Environmental Security. Edited by Matthew A. Schnurr and Larry A. Swatuk. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, pp. 170–89. [Google Scholar]

- Rene Fumoleau. (1975) 2004; As Long As This Land Shall Stand: A History of Treaty 8 and Treaty 11, 1870–1939. Calgary: University of Calgary Press.

- Stéphane M. McLachlan. “Water is a Living Thing”: Environmental and Human Health Implications of the Athabasca Oil Sands for the Mikisew Cree First Nation and Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation in Northern Alberta. Winnipeg: Environmental Conservation Laboratory, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jen Preston. “Neoliberal Settler Colonialism, Canada and the Tar Sands.” Race and Class 55 (2013): 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinton N. Westman. “Social Impact Assessment and the Anthropology of the Future in Canada’s Tar Sands.” Human Organization 72 (2013): 111–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Indigenous Environmental Network. “Tar Sands.” Available online: http://www.ienearth.org/what-we-do/tar-sands/ (accessed on 12 July 2015).

- Naomi Klein. “Dancing the World into Being: A Conversation with Idle No More’s Leanne Simpson.” Yes! Magazine. 5 March 2013. Available online: http://www.yesmagazine.org/peace-justice/dancing-the-world-into-being-a-conversation-with-idle-no-more-leanne-simpson (accessed on 12 December 2015).

- Pramod Parajuli. “Revisiting Gandhi and Zapata: Motion of Global Capital, Geographies of Difference and the Formation of Ecological Ethnicities.” In In the Way of Development. Edited by Mario Blaser, Harvey A. Feit and Glenn McRae. London: Zed Books, 2004, pp. 235–56. [Google Scholar]

- 1The term unconventional refers to recent technological innovations used to extract oil and natural gas from shale formations, sands, and coal seams.

- 2Taiaiake Alfred (Kahnawake Mohawk) and Jeff Corntassel (Cherokee) reflect on the meaning of settler colonialism today, stating that “contemporary Settlers follow the mandate provided for them by their imperial forefathers’ colonial legacy, not by attempting to eradicate the physical signs of Indigenous peoples as human bodies, but by trying to eradicate their existence as peoples through the erasure of the histories and geographies that provide the foundation for Indigenous cultural identities and sense of self…[Indigenous peoples] remain, as in earlier colonial eras, occupied peoples who have been dispossessed and disempowered in their own homelands” ([14], p. 598).

- 3While a description of research ethics and reciprocity falls outside the scope of this brief article, readers interested in learning more about my stance should consult my earlier work [15]. In addition, Devon Mihesuah (Choctaw) and Luke Eric Lassiter have both published valuable guides on conducting research in Indigenous communities [16,17].

- 4These costs are typically (and conveniently) left out of industrial accounting. The term externality refers to impacts of commercial or industrial activities experienced by third parties and therefore not reflected in the pricing of produce goods or services.

- 5In a 2013 editorial, for example, environmental political scientist Thomas Homer-Dixon wrote that oil and gas extraction “is relentlessly turning our society into something we don’t like. Canada is beginning to exhibit the economic and political characteristics of a petro-state” [21].

- 6In October 2015, Canadian citizens elected Justin Trudeau of the Liberal Party as Prime Minister. While the implications of this leadership change for extractive industry are still uncertain, Trudeau campaigned on promises of more stringent environmental regulation and fuller participation in the fight against global climate change.

- 7I have elsewhere presented a detailed treatment of the land-based self-determination concept as it relates to contemporary Indigenous counter-mapping practices [24].

- 8The majority of Canada’s boreal region is overlain by 11 “numbered treaties” signed between 1871 and 1921 [32]. Although articulated in various manners, these treaties generally promise that Indigenous signatories would retain the right to engage in land-based subsistence throughout ceded tracts of land. Readers interested in learning more about Canada’s treaties and their relationship to contemporary questions of Aboriginal rights can consult books on the topic by J. R. Miller and Michael Asch [33,34].

- 9Coon Come later led the Grand Council of the Crees and went on to become National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations.

- 10Signed on 7 February 2002, this agreement is formally known as the “Agreement Respecting a New Relationship between the Cree Nation and the Government of Quebec” [43].

- 11From the author’s fieldnotes dated 9 October 2004.

- 12Annual logging rates in Canada’s boreal forests increased from 1.6 million acres in 1970 to 2.5 million in 2001 [48]. Northwestern Ontario was no exception to this trend.

- 13Treaty Three clearly states that signatory Indians would “have right to pursue their avocations of hunting and fishing throughout the tract surrendered” [50].

- 14The third largest source of diamonds in world, Canada’s diamond industry constitutes roughly 3 percent of the gross domestic project [55].

- 15Because it is so costly to produce, profitable tar sands production requires high oil prices and is therefore tied to the vagaries of the global market.

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Willow, A.J. Indigenous ExtrACTIVISM in Boreal Canada: Colonial Legacies, Contemporary Struggles and Sovereign Futures. Humanities 2016, 5, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/h5030055

Willow AJ. Indigenous ExtrACTIVISM in Boreal Canada: Colonial Legacies, Contemporary Struggles and Sovereign Futures. Humanities. 2016; 5(3):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/h5030055

Chicago/Turabian StyleWillow, Anna J. 2016. "Indigenous ExtrACTIVISM in Boreal Canada: Colonial Legacies, Contemporary Struggles and Sovereign Futures" Humanities 5, no. 3: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/h5030055

APA StyleWillow, A. J. (2016). Indigenous ExtrACTIVISM in Boreal Canada: Colonial Legacies, Contemporary Struggles and Sovereign Futures. Humanities, 5(3), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/h5030055