Abstract

Giovanni Boccaccio’s Teseida delle nozze d’Emilia (1339–1341?) is an innovative vernacular text in which Teseo (Theseus) and the Scythian Amazons are reinvented as antagonists in a war fought to determine how women are meant to live their lives. Boccaccio’s characterization of these figures and their interactions offer an effective counter-narrative to the prevailing ethos that women’s inborn proclivities and deficiencies preclude, perforce, their participation in the public arena. In the absence of written criticism, cassone (marriage chest) paintings constitute the quattrocento Nachleben of the text, whose readership comprised a wide swath of the literate populace through the 15th century. I will argue that painters, in conjunction with their patrons and humanist advisors, fashioned Teseida visual narratives that undermined Boccaccio’s vision of the potential of women to productively and autonomously engage in the governance of successful societies.

Giovanni Boccaccio’s Teseida delle nozze d’Emilia (1339–1341?) is the work of an intellectual young writer experimenting with the hybridization of classical and medieval literary traditions to develop new ways of engaging with ageless concerns. Insight into early Renaissance reader reception of Boccaccio’s innovative endeavor is hampered by a lack of contemporary commentary; as Jane E. Everson observes, humanists were “at best silent about vernacular literature…and at worst scathing in their hostility towards all such fables and fictions, especially in verse and in Italian” ([1], p. 112). The Teseida, written both in verse (ottava rima) and in Italian, was indeed ignored by literary exegetes; nonetheless, it was adapted for visual narratives made to embellish Tuscan cassoni (marriage chests). In the absence of written criticism, these paintings constitute the quattrocento Nachleben of a text whose readership comprised a wide swath of the literate populace through the 15th century (see [2]; [3], pp. 9–11, 27–28, 42–43; [4], pp. 34–38, 99–103, 130–32, 301–3).

In the Teseida, Boccaccio reinvents Teseo (Theseus) and the Scythian Amazons as antagonists in a war fought to determine how women are meant to live their lives.1 His characterization of these figures and their interactions offer an effective counter-narrative to the prevailing ethos that women’s inborn proclivities and deficiencies preclude, perforce, their participation in the public arena.2 I will argue here that cassone (marriage chest) painters, in conjunction with their patrons and humanist advisors, fashioned Teseida narratives that undermined Boccaccio’s vision of the potential of women to productively and autonomously engage in the governance of successful societies. Through a process of alteration, omission, and contrived association, Boccaccio’s text was reconstructed to promote patriarchal customs and the entrenched assumptions of gender that gave rise to them. The example of Teseida paintings suggests that Florentine plutocrats employed the imaginative power of visual artists as a counterweight to the anormative literary imaginations finding expression in vernacular fiction.

Commissioned as gifts to betrothed children throughout the 15th century, Florentine cassoni were constructed in pairs and filled with marriage gifts that were ceremonially carried from the bride’s natal home to that of her husband. The chests thereby became standard fixtures in the homes of educated Florentine patricians, where the “readership” of their narratives comprised the many and varied occupants of a growing household who might receive edification from imagery associated with marital and/or civic obligations.3 Scholarship relevant to understanding the process of translating texts to cassone pictorial imagery is hampered by a paucity of documentation regarding the relative contribution of artists, patrons, and knowledgeable advisers to the selection of imagery and its manner of representation. Further, having been undervalued for centuries as “decorative art”, the vast majority of cassoni have been dismantled or destroyed. Fortunately, extant panels attest to the practice of employing a canon of recognizable (though often modified) templates, suggesting that the paintings discussed in this study should be considered as illustrative of a larger body of lost work.

The necessity of distilling source material into a few discrete, recognizable episodes meant to convey a narrative arc and a sense of its moral significance gave those involved in designing cassone panels appreciable editorial license; even so, these Teseida narratives (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3) betray a marked lack of interest in condensing Boccaccio’s 12-book text into a sequence of highlights from which one might recreate the storyline. On the contrary, the vast majority of the author’s Teseida finds no point of correspondence in these paintings, and the events that are represented differ substantively from their portrayal in the text.4

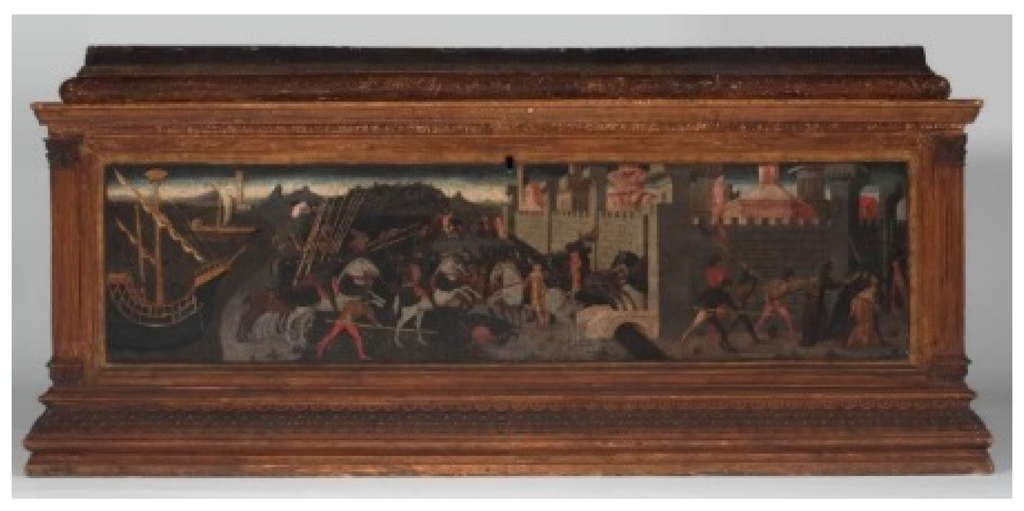

Figure 1.

Domenico di Michelino. Teseida: Battle of Theseus and the Amazons. c.1450. Indianapolis: Indianapolis Art Museum, Martha Delzell Memorial Fund, 62.164, imamuseum.org. [14].

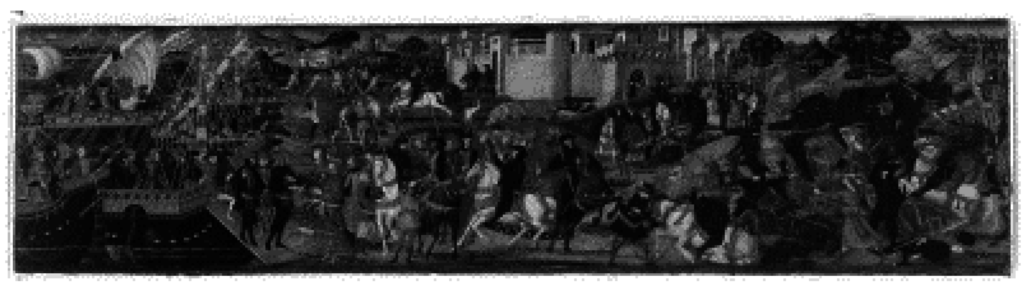

Figure 2.

Paolo Uccello. Teseida: Battle of Teseo and the Amazons. c.1460. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery. [15].

Figure 3.

Apollonio di Giovanni, and Marco del Buono. Teseida: Duel of Arcita and Palemon and Triumphal Procession. c.1465. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Bequest of Mrs. Martin Brimmer, 06.2441. [16].

Figure 1 and Figure 2 are similar fabrications of an Amazonomachy in which all of the warriors who engage in combat with an invading army are women. This distinguishes Boccaccio’s Amazonomachy from that fought by the Greeks at Troy, where Penthesilia and her viragoes represent but a small fraction of the Trojan forces. It also distinguishes Boccaccio’s battle from the war fought by Aeneas (against Turnus) in his attempt to claim Latium for his band of displaced Trojans. While Camilla is frequently depicted as one of Turnus’ allies in this cause, she did not lead an army of Amazons; her dedication to the virgin goddess Diana came about under singular circumstances, and as queen of the Volscians she led an army of men. I therefore agree with Paul Watson ([17,18] and Cristelle Baskins [13], pp. 26–49), who identify these cassone paintings as representing Boccaccio’s Amazonomachy which Teseo, Duke of Athens, initiates after receiving word that the Scythian viragoes have been forbidding men access to their territory. The images depict, explicitly and without exception, men doing battle against women, a situation unique to the Teseida and the incensed duke’s resolve to employ a violent corrective to the female audacity that is an affront to his sense of moral order.

In the first panel, Teseo’s fleet and the Amazons’ city flank a battlefield on which the women clearly outnumber the men. The viragoes, who continue to stream through the city gate, are also in the enviable position of riding horseback into battle against soldiers who have just come ashore on foot. Nonetheless, the heavily armored Greeks decisively dominate the warrior women, who enter the fray wearing long, colorful gowns. This choice of raiment suggests that, though they might play at being men, the Amazons are hobbled by deficiencies intrinsic to womanhood. This message is reinforced by a large group of Amazons in the middle ground who, with no immediate pursuers in evidence, inexplicably flee in retreat. The body count alone attests to the women’s inability to leverage their material advantages: five prominently displayed female corpses are gruesomely trampled underfoot while the only hint of Greek vulnerability is the scarcely discernable head of a single fallen soldier. The second panel (Figure 2) depicts a more balanced, though comparably composed, scene of battle. In this instance, male supremacy manifests on the right side of the panel, where soldiers prod a number of cowering Amazons towards a city gate. Although armed, the women do not fight, but instead allow themselves to be corralled by three soldiers and a flag bearer. Regardless of whether or not the events depicted on each of these panels are read as concurrent, the men never lose and the women never win.

This vision of the Amazon’s futile attempt to defend their autonomy runs counter to Boccaccio’s detailed account of their martial prowess:

they poured molten oil, pitch, and soap over the Greek troops. There was no hand-to-hand combat because the Greeks had not yet been able to seize any part of the coastline. The encouragement and assistance which good Theseus offered them availed them nothing. Rather, each one seemed utterly lost as he saw the ranks of those ladies increasing and becoming bolder from moment to moment. I shall say nothing of the darts, arrows, and missiles with which the sky was darkened and which filled all the lovely air and rained down one after the other.[19].5

Boccaccio’s Amazons defend themselves with courage and skill, and the bloodied invaders beat an ignominious retreat to their ships. Teseo, “with an enflamed face and an angry scowl” [19], berates his dispirited men as being the “disgrace of the Argive people” [19].6 Despairing of their virility and “almost losing his wits in grief” [19] he plunges into the water, strides ashore, and attacks the women “just like a ravenously hungry wolf who thrusts himself among the little lambs and seizes them here and there by the throat with his teeth until he has sated his greedy craving” [19].7 His chastened men follow, and the viragoes must eventually retreat to their fortress. Having failed to vanquish the women in battle, the Greeks set up camp and settle in for a prolonged siege of their city.

Boccaccio’s description of the Greek/Amazon conflict is one component of a multivalent critique of the tenet, rendered problematic throughout the Teseida, that the subjugation of women by men is driven by the unassailable dictates of biology. Trusting in gender as a reliable construct, Teseo, in anticipation of a rapid and painless victory, sends his soldiers ashore ill-prepared. In the face of Amazon strength, he accuses his army of being weaker than weak women. Cassone Amazonomachies effectively circumvent Boccaccio’s critique by expunging all evidence that “no one had ever suffered more” [19] than did the Greeks at the hands of the Amazons.8 These stalwart and unscathed soldiers are unrecognizable as the men who shouted in pain because “there were very few, in fact, who were not wounded in the heart or in the side or in some other part of the body” [19].9 Are these the warriors who “saw their blood flowing on the waves and turning the melancholy foam a deep red,” among whom “even the bravest took cover, so fearful were they of the women’s arrows?” [19].10 There is certainly no indication that, had they not been led by a veritable superhero fueled by an inexhaustible supply of bile, the Greeks most certainly would have fled the Scythian shores.

Scholars have traditionally read Teseo as an enlightened hero who subdues the forces of chaos represented by the untethered Amazons (see [21]; [22], pp. 46−47). Robert R. Edwards considers the duke to be a “model of heroic action…and a figure of considered judgment” ([23], p. 23). These readings incontestably align with Teseo’s conception of himself as being a dutiful arbiter and purveyor of justice at home and abroad. Carla Freccaro, however, argues that the Greek suppression of the “autonomous female principle…destabilizes Theseus’ exemplary heroic status and the effort to exclude alternative and competing mythological genealogies from the text” ([24], p. 30). I suggest that his status as a warrior king is further compromised by the impetuous, passion-driven nature of his quest. Although Teseo will later demonstrate the composure necessary for a leader to be guided by the reason, justice, liberality, and mercy encouraged by the medieval speculum principis (mirror of princes) tradition, in his crusade against female autonomy he reacts impulsively and in the grip of emotions over which he exercises no control—a dangerous proclivity long associated with the inferior constitutions of women.

Other voices continue to sabotage the reliability of Teseo’s perceptions. Queen Ipolita, in marked contrast to a duke struck mad with fury, first by the Amazons’ audacity and subsequently by his soldiers’ failure to render that audacity groundless, never loses her equanimity. In response to the impending and unprovoked attack, she speaks calmly to her followers of their longstanding resolve to live free from servitude:

“And do not let your conscience trouble you that you have sinned against your men, since it was their ingratitude that justified their deaths in our hearts. For they did not treat us as if we had been born of the same kind of seed as they were, but we pleased them little more than if we had been engendered of monsters, or oak trees, or even caves.”.[19]

She rightly surmises that Teseo “deems us troublesome because we are not satisfied with remaining subject to men and obedient to their whims like other women” [19],11 and stresses that “we have never committed any offense against him for which we should be attacked. Besides, his reasoning lacks genuine merit, since anyone who helps himself in recovering the freedom he has lost is not doing anything wrong” [19].12 Whether or not the reader approves of the viragoes’ methods for obtaining their freedom, these are not the “wild and ruthless women” [19] of rumor.13 Access to the Amazons’ interpretation of and response to their treatment by men (first husbands, now Greeks) helps to dissipate ineffable fears of otherness that accrued to the Amazons of legend. Edwards, who sees Teseo as a “model of heroic action” considers the Amazons to “reproduce the essential features of epic heroism” ([25], pp. 23–24), while Gambera notes that they “act very much like Teseo and the Greeks who have come to attack them” ([26], p. 164). Ipolita and her followers discuss the situation and decide to defend the right to “display virile courage” [19] and to “perform manly, rather than womanly, deeds” [19], of which men are determined to deprive them.14 Thus, although the antagonists agree that the most valuable lives are those defined by adherence to the dictates of conventional masculinity, Teseo disavows the possibility of women meeting this standard within the parameters of a civilized cosmos, while Ipolita knows that they can, and believes that they should.

During the months of the siege, Teseo frequently “assailed the damsels in battle with his confident troops. But he found the women equipped with such intrepidity, that one assault or another availed little…because very often the women within risked death by preying on them boldly…” [19].15 When the duke finally discovers a way to undermine the walls, he draws ridicule from the queen: “But now you have sounded out your might and, if you reflect, you have found it useless. So you have found other ways underground to have me safely in your prison…fighting in dark places is neither the craft nor the art of a good warrior” [19].16 Readers of the text, having both watched the conflict unfold and become familiar with the motivations of the antagonists, may sympathize with this assessment—the Amazons will lose not because they are inferior warriors but because the Greeks got lucky. While Teseo is (and ever will be) unmoved by Ipolita’s words, her textual voice, in conjunction with the Amazons’ proven capacity for self-governance and self-defense, is a potent rejoinder to Teseo’s conviction that the women must be subjugated. Readers of the visual narratives, however, are restricted to a vision of the world as Teseo would have it be, and therefore see the Amazons lose because they are fundamentally incapable of winning.

Recharacterizing the natures of the Greeks, the Amazons, and the course and outcome of their war, was not the only means by which cassone artists countered the Teseida’s vision of women as able to govern and defend societies with competence equivalent to that of men. At the time these paintings were executed, humanist pedagogues promoted Virgil’s Aeneid as a peerless model not only for excellence in writing but also for virtuous living.17 The most widely read work of Latin antiquity in the 15th century, the Aeneid, like the Teseida, explored civic duty and gender politics in the context of a legendary figure’s invasion and defeat of an indigenous people. Craig Kallendorf notes that quattrocentro commentary “shaped the kinds of moral content that readers were able to see in Virgil’s poetry,” so they would not be “set adrift to form their own conclusions” ([29], pp. 35, 38).18 Many literary critics recognize Boccaccio’s multifaceted debt to the Aeneid; I suggest that painters sought to shape reception of the Teseida by aligning it with imagery employed in Aeneid cassone narratives.19 Envisioning the Teseida as a late medieval heir to this unparalleled treasure of classical antiquity would have favored the accentuation of features most recognizable as “epic” in Boccaccio’s work, thereby encouraging conservative interpretations familiar from established exegesis.

The extreme popularity of the Aeneid as a source for Florentine cassone narratives speaks to a widespread interest in extending its didactic potential to the daily visual environment of patrician families (see [13], pp. 75–102; [33,34]). Workshops developed iconographical shorthand to translate the relevance of Aeneas, the displaced Trojan warrior king destined to found Rome, to the civic-minded patriarchs of a thriving Tuscan republic. Both ancient and contemporary commentators read the Trojan conquest of Latium as an allegory for the supersession of native barbarism by the civilizing force of reason, and the landing of a hero’s ships on foreign shores signified the imminent subjugation of an inferior culture to a superior one. Aeneas’ fleet is prominent in Figure 4 and, while Teseo’s fleet does not compare in size, Teseida cassone painters devote even more precious space to this signifier of enlightenment (Figure 1 and Figure 2), thereby squarely situating their narratives within the tradition of classical epic.

Figure 4.

Paolo Uccello. Trojans Land in Latium and the Battle of Camilla, Turnus and the Trojans. c.1470. Seattle: Seattle Art Museum, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 61.173. [35].

In Figure 1, soldiers are shown attacking from their ship, visually binding the Greek forces to an ennobling emblem that, in the text, Boccaccio immediately degrades: “The women continuously hurled fire onto the armed ships, which caught flame, and this greatly hampered the Greeks. At the same time their engines catapulted heavy rocks which immediately splintered those ships they hit and that had been left unprotected” [19].20

So, by the time the Greeks successfully engage the Amazons in battle, their fleet has been badly damaged. The pristine ships depicted in paintings not only eliminate this embarrassing evidence of Amazon military might and Greek negligence, but preserve their significance as symbolic of a wise and righteous quest.

One would expect that painters, having reimagined the first book of the Teseida to advocate for an ideology that the author subjected to adverse scrutiny, would find much of the 11 books’ worth of remaining material to be either dispensable or antithetical to their cause. This proves, in fact, to be the case: the material of books 2–7 is omitted, and not for want of incident. Book 2 is devoted to Teseo’s war against Creon of Thebes, who will not allow the rotting corpses of his enemies to receive burial rites. The cassone panels make no reference to this campaign, in which Teseo corrects an unambiguously blasphemous wrong and kills a manifestly insane tyrant. This would be an inexplicable omission if the paintings were meant to celebrate the breadth of Teseo’s heroism; if, however, the objective were to construct narratives aimed at promoting and defending the gendered tenets of a patriarchal society, Creon would be an irrelevant distraction.

In the following books, Teseo returns to Athens with two noble Theban hostages, Arcita and Palemon, who fall prey to an ever-intensifying passion for Teseo’s beautiful young sister-in-law, Emilia. Emilia is Ipolita’s sister; following the Amazon’s surrender, the duke marries the vanquished queen, who disappears into the silent and passive role of Duchess of Athens. Intrigues and emotional upheavals associated with the Thebans’ captivity and unrequited love are examined in Books 3–7 of the text but are ignored by the painters. As a result, the visual narratives are devoid of medieval romantic tropes that would compromise the Teseida’s conscription into service as an epic in the grand tradition of the Aeneid.

We cannot know how representative Figure 3 is of panels executed to be pendants to Amazonomachy paintings. It is clear, however, that the events depicted are consistent with an intention of selecting material that painters could both mold into the forms of classicism and use to reinforce the necessity of containing women through marriage. The painting opens with yet another scene of battle, this time a tournament engineered by Teseo to determine which of his Theban captives will marry Emilia. This scheme is devised when the duke comes across the young men—one having escaped from prison and the other having surreptitiously returned from forced exile—dueling to the death for Emilia, who loves neither of them. Not recognizing the men, Teseo offers to exchange amnesty for knowledge of their identities. Although their disclosure momentarily angers the duke, he immediately resolves to host a magnificent tournament in which the greatest warriors of Greece will battle on behalf of the suit of one or the other of the young men. His objective is to replace the savage duel with a civilized, structured contest.

The painted tournament grounds bear no resemblance to the detailed description provided in the text:

The round theater was situated outside the land and was not a finger less than a mile around. Its marble wall, of impeccable workmanship, rose so high toward heaven that the eye almost tired of gazing at it. It had two entrances with strong, well-made doors…Circular terraces rose up from it in more than five hundred tiers, I believe, and ascended up to the height of the wall by means of wide steps of splendid stone. People used to sit on these steps to watch cruel gladiators or others engage in some game, without getting in one another’s way anywhere.[19]21

Painters chose to ignore Boccaccio’s description in favor of relocating the melee to a piazza and the spectators to a Renaissance palazzo from which the action could safely be observed. While such anachronisms were often employed to help render history and legend relevant to contemporary viewers, it is worth noting that this setting, down to the three large second-story windows draped with decorative textiles, is nearly identical to that depicted on a panel in which Aeneas prepares to execute Turnus and thereby secure both Lavinia’s hand in marriage and the Latin throne (Figure 5). Within both fortress-like structures, a young virgin (Emilia in the Teseida, Lavinia in the Aeneid), surrounded by attendants and family members, placidly awaits an outcome that will dictate her transfer from one patriarch to another. As, famously, Virgil’s Lavinia never speaks, she is typically read as emblematic of the beneficial alliances that may be established through prudently arranged marriages. Because viewers were unlikely to pity the woman who married Aeneas, Lavinia presented a good object lesson for Renaissance daughters, who were expected to submit passively to furthering their fathers’ interests.

Figure 5.

Apollonio di Giovanni. Death of Camilla and the Wedding of Aeneas and Lavinia. c.1460. Ecouen: Musée de la Renaissance. [36].

By likening Emilia to Lavinia in context and demeanor, the painter suggests that they share a common function in the larger narrative. This is indeed the case; in both texts, the patriarch has determined that his female dependent will be awarded in marriage to the victor of an armed conflict. As this victor is presumed to be the better man of the two, both patriarch and daughter/ward will have fulfilled their familial and civic obligations by playing their respective parts in forging advantageous alliances. Additionally, the fear of scandal occasioned by having an unmarried woman under the roof has been averted. Lavina and Emilia thus appear as interchangeable exemplars whose individuality (like that of Renaissance daughters) is largely irrelevant to their raison d’etre.

In the Aeneid, Lavinia’s response to her suitors is limited to tears and a blush, which, while variously interpreted by modern critics, was easily ignored by 15th-century interpreters interested in her allegorical significance. Painters of a contentedly pliant Emilia, however, knowingly disregarded Boccaccio’s portrayal of a woman intensely opposed both to Teseo’s tournament and to her ultimate marriage to Palemon. Her resistance to the first is revealed in a lengthy prayer to Diana, and to the second in a reasoned plea, addressed to her brother-in-law, that she be allowed to remain virginal:

“As you have been able to hear, all the Scythian ladies were vowed to Diana when they first desired their freedom and you well know that she quickly wreaks vengeance on those who oppose or do not keep what they have promised her, as those know whom it awaits…I think that it would be better, without any further test of the will of the gods, to let me serve Diana and to live and die in her temples.”[19]22

Emilia is not Lavinia. She wishes to remain virginal in fulfillment of a vow to a goddess. Her suitors are unexceptional; all that is known of them is that they were loyal to a madman, quick to deceive their merciful captor, and in thrall to lovesickness. Her marriage is not integral to a providential design of incomparable import; it is the consequence of an autocrat’s caprice that proves grievously misguided as the conflict devolves into a casualty-ridden bloodbath. What Teseo wrongly identifies as isolated savagery is revealed to be a predilection of even the finest of civilized men. Nonetheless, although Emilia’s piety, integrity, and clarity of thought led her to suggest a respectable course of action that will relieve Teseo of the obligations of guardianship, he tells her that her words are as niente—nothing.23 The duke never sugarcoats his refusal to engage with women’s ideas, which are invariably met with disparagement. Thus, Boccaccio uses Emilia’s voice, as he did her sister’s before her, to problematize Teseo’s restriction of women who are manifestly capable of rational deliberation to the submissive existence of wifehood.24

James H. McGregor, in his reading of the Teseida as a critique of paganism, observes that “Theseus is seriously deluding himself” into thinking that he has the “capacity to regulate so much furor” ([22], p. 66). I suggest that he is also deluding himself in thinking that women must be vigilantly regulated to preserve civilized order; how could Emilia pose a threat greater to men than they do to themselves? By associating Emilia with Lavinia and Teseo’s contrived tournament with Aeneas’ war, painters were able to exploit the positive potential of Teseida/Aeneid visual associations and thereby sanitize Boccaccio’s fraught vision of patriarchal authority. A final detail of the tournament scene is worth noting; the dramatic image in the center foreground recontextualizes a pivotal moment in the competition for Emilia’s hand: the suitor Arcita is crushed beneath his horse, which falls backwards after rearing up on its hind legs and throwing its rider. The accident happens when Arcita, having been declared the winner, takes a number of jubilant victory laps around the arena. By depicting his tragedy as occurring during the heat of battle, painters transform an act of bravado into a misfortune of war.

The right half of the Teseida panel is devoted to a classical triumph that reads as an outcome of the battle that precedes it. In Book 9, the dying Arcita rides in a chariot with Emilia by his side; however, if this is Arcita’s chariot, the visual narrative concludes three-quarters of the way through the text. There are other compelling reasons why this is unlikely to be the couple depicted in the painting. The planned post-tournament procession of victors and vanquished has become a charade enacted because Teseo is unable to accept that his grand spectacle failed to produce a viable victor. Although a wedding is hastily performed, Arcita’s injuries preclude its consummation. Not simply a detail that vitiates his “triumph,” Arcita’s impotency would have been recognized as amounting to a legal invalidation of his marriage.25 New complications arise when, during the course of a protracted deathbed speech, the self-pitying young husband bequeaths his wife to his erstwhile friend Palemon who, humiliated in defeat, refuses the gift. Teseo steps in and, ignoring the pleas of the traumatized young widow, orders Palemon to marry Emilia. Palemon thereby takes possession of a prize he did not earn and, thus, by implication, may not deserve. I suggest that the cassone triumph celebrates neither Arcita’s pyrrhic nor Palemon’s tainted victory, but is emblematic of the power of marriage to forge political alliances. Seen as allegory, this entire panel distances itself from a text that might reasonably be read as a parody of female subjugation through marriage.

Fifteenth-century literary and visual engagement with the Aeneid supports a symbolic reading of this final image. In 1428, the Florentine Maffeo Vegio wrote Libri XIII Aeneidos Supplementum to address a moral quandary associated with Book 12 of Virgil’s epic.26 In this concluding chapter, Aeneas, in the grip of an uncharacteristic rage, decapitates the defeated Turnus. Kallendorf argues that Vegio’s Supplementum picks up where Virgil left off in order to frame Aeneas’ action as an safeguard from the threat of chaos posed by Turnus’ intractable insanity ([40], p. 51). The Supplementum, frequently included in manuscripts and early printed editions of the Aeneid, also gives a moral seal of approval to Trojan aspirations by providing Aeneas with both a ceremonial triumph and a wedding. That these addenda were considered as compelling signifiers for the legitimacy of Aeneas’ claims is attested to by their frequent appearance in cassone narratives [33,37].27 So, in Figure 5, Turnus’ execution is followed by Aeneas’ marriage ceremony, while in other paintings Aeneas rides in triumph with Lavinia walking at his side. In closing their Teseida narratives with an image of a triumphant betrothed couple, painters continue to occlude much of the import of Boccaccio’s text by alluding to Virgil’s.

There is yet another way in which Teseida painters may be seen to dissociate their work from the particulars (and thus implications) of Boccaccio’s text: constructed similarities between cassone representations of the Teseida and the Aeneid do not extend to elevating their eponymous protagonists to positions of equal visual prominence. Aeneas is always the visually salient hero of his narratives: he speaks to the king (Figure 4 and Figure 5); he executes his enemy (Figure 5); he marries the right woman (Figure 5); he rides in a triumphal chariot. While it may be assumed that Teseo is present in cassone paintings (he is probably the soldier in the water in Figure 1 and one of the men watching the tournament in Figure 3), disambiguating this point was not a prerogative. Teseida didacticism in Renaissance painting relies on recognition of firmly established tropes of epic heroism—ships, battles, and triumphs—rather than identification with a virtuous exemplar.

Florentine Chancellor Coluccio Salutati asserted that Virgil “gathered all virtue into Aeneas and proposed him to us for imitation,” and 15th-century exemplarity rhetoric continued to promulgate this view.28 Christopher Landino (1488) considered Aeneas to be a vir perfectus, “the perfect man in every way,” created “so that we all take him as the sole exemplar for the living of our lives.” ([41], p. 20). Aeneas earned the distinction of vir perfectus through a painful process of maturation through introspection; he allows his experience of a harsh world mold him into an empathetic leader who accepts the imperative to subordinate both his desires and antipathies to justice and the greater good. Nowhere is this more evident than in his relationship with Dido, whom he loves and respects as a political and intellectual equal, but relinquishes in order to advance Trojan ambitions. Teseo’s success lies in having a will whose strength and endurance rivals his fighting arm. His decisions are adamantine from the moment of their inception, and self-reflection never enters into an assessment of their consequences. The lens through which Teseo perceives the world effectively filters out information that contradicts his biases and assumptions, setting him apart not only from the heroes of epic, but of romance; as Simon Gaunt observes, chivalric heroes generally “evolve and assume new identities through love and their relations with women” ([42], p. 72). Perceiving his extraordinarily intelligent and capable wife as an acquisto ([20], 1.131.8), he marries her for her beauty, and it is only for her beauty that she will be admired as Duchess of Athens. Following the duke’s denial of her request to fight alongside him in Thebes, Ipolita falls silent (although the narrator observes that Amazon valor continues to burn within her).

Why were painters and their humanist advisers and patrons sufficiently interested in the Teseida to confront the challenge of reshaping its vision to conform to their own? The answer must lie in part with Boccaccio’s standing (alongside Dante and Petrarch) as one of the venerated “Three Crowns of Florence.” Modern criticism, heavily weighted towards Boccaccio’s vernacular fiction (especially the Decameron), tends to obscure the fact that Boccaccio’s 15th-century auctoritas rested on humanist esteem of his late, Latin works.29 For early Renaissance letterati, these pedantic, scholarly works of Boccaccio’s old age eclipsed the vernacular fiction of his youth. On occasion, however, the classicizing aspects of the Teseida (especially the extensive authorial glosses) appear to have exempted the text from the stigma suffered by other vernacular poetry. Daniels documents prominent humanist pedants as figuring among the Teseida’s quattrocento readership; elegant parchment manuscripts were commissioned both in Florence and in the Este court, while Agostino Carnerio printed the editio princeps of the text in Ferrara in 1475, one of few literary (and even fewer vernacular) works to be printed in this seat of humanist learning at so early a date ([2], pp. 48–51). Daniels argues that Carnerio used a roman font for both vernacular and Latin works in order to emphasize their classical elements and thus make them more appealing to humanist readers ([2], p. 60).

Justification for reimagining the Teseida to promote complementary notions of the prerogative and capacity of men to govern and the duty and necessity of women to be governed can be found in Boccaccio’s own reevaluation of gender and gender politics in his late writings. Female intellect and talents, often valued in his early vernacular works, came to be regarded as tools employed to keep men in thrall.30 De mulieribus claris (begun c.1360), a compendium of the lives of famous women drawn primarily from classical source material, was not only the touchstone for 15th-century biographical anthologies of women, but a source mined for both literary and visual imagery throughout the Renaissance. Boccaccio situates De mulieribus claris within the ancient genre of edifying exempla literature and fully exploits the heavy-handed moralizing encouraged by this form; his stated goal is to present lives that “will drive the noble towards glory and to some degree restrain villains from their wicked acts” ([46], p. 11).

Throughout De mulieribus claris, Boccaccio frames the strengths and accomplishments of famous women as being dangerous to men [43,47,48]. Adam and Eve establish a paradigm of disaster born of male failure to rein in female ambition: “(Eve) flattered her pliant husband into her way of thinking” because she “foolishly thought that she was about to rise to greater heights” ([46], p. 17). Subsequent biographies reinforce the warning that female intelligence, except when employed specifically to further the interests of absent husbands, sons, and fathers, cannot be trusted. So, for example, when Ceres invented the plow and taught men (who had hitherto subsisted on acorns and wild fruit) to cultivate the land, she interfered with God’s intention that humans “content themselves with only the law of nature” ([46], p. 33). Boccaccio weighs the benefits of living in a “civilized age” against “those golden centuries,” and credits Ceres’ innovations with unleashing countless evils now endemic to mankind: poverty, servitude, war, envy, laziness, disease, lasciviousness, and even—through a tortuous process of reasoning—starvation ([46], pp. 31, 35). In several biographies, female intelligence is correlated with sexual wantonness, a vice for which no virtue can compensate. Sempronia wrote “with such discernment as to elicit the admiration of all her readers,” but, “to satisfy her burning lust, she completely discarded any kind of reputation as a chaste woman and was not so much men’s prey as their hunter” ([46], pp. 329, 331). Leontium, who had “extraordinary intellectual powers,” nonetheless “disregarded feminine decency…staining Philosophy, the teacher of truth, with ignominy” ([46], pp. 251, 253).

The burden to maintain dominance must be shouldered by the patriarch of every household. In De casibus virorum illustrium (begun c.1360), Boccaccio repeatedly employs the language of warfare in addressing gender relations: “It is not necessary to believe a woman’s tears or her complaints, but a person should be as wary of their cunning as of that of an implacable foe” ([49], p. 45). He exhorts men to conquer any tendencies towards capitulating to womanly wiles, as “it is not in any way necessary to divide the power given us with them, much less to abdicate to them, as a few persons overly devoted to women have done to their great disaster” ([49], p. 45). The ideologies promulgated in these writings of the author’s maturity may have been plumbed as a corrective to the youthful meditation on female agency that is woven into the very fabric of the Teseida.

Boccaccio’s vernacular fiction is rife with critiques of the notion that women are teleologically bound to yield authority to men, and the Teseida offers a fresh means of appraising prevailing antagonisms towards female autonomy. Its vision of women functioning both independently of, and on a par with, men is not undercut by heinous aberrations in either their motivations or behavior. Visual artists responded by reimagining Boccaccio’s text to convey as axiomatic that gender-based expectations, restrictions, and rewards inhere in successful patriarchies. In the case of the Teseida, the audacity of the literary imagination to question contemporary patriarchal practices was more than met by the audacity of the pictorial imagination to shamelessly assimilate it.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References and Notes

- Jane E. Everson. The Italian Romance Epic in the Age of Humanism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rhiannon Daniels. Boccaccio and the Book: Production and Reading in Italy 1340-1520. London: Legenda, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Edvige Agostinelli. “A catalogue of the manuscripts of Il Teseida.” Studi sul Boccaccio 15 (1985): 1–83. [Google Scholar]

- Vittore Branca. Boccaccio Visualizzato. Turin: Einaudi, 1999, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Josine Blok. The Early Amazons: Modern and Ancient Perspectives on a Persistent Myth. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Leon Battisti Alberti. I libri della famiglia, n.p.: 1430.

- Francesco Barbaro. De re uxoria liber, n.p.: 1416.

- Letizia Panizza. Women in Italian Renaissance Culture and Society. Oxford: Legenda, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Christiane Klapisch−Zuber. Women, Family and Ritual in Renaissance Italy. Translated by Lydia Cochrane. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Paul Schubring. Cassoni: Truhen und Truhenbilder der italienische Frührenaissance. Leipzig: Hiersemann, 1923. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen Callmann. Apollonio di Giovanni. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Cristelle L. Baskins, Adrian W. B. Randolph, and Jacqueline Marie Musacchio. The Triumph of Marriage: Painted Cassoni of the Renaissance. Boston: Isabella Steward Gardner Museum, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cristelle L. Baskins. Cassone Painting, Humanism, and Gender in Early Modern Italy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Teseida: Battle of Theseus and the Amazons. Indianapolis: Indianapolis Art Museum, Martha Delzell Memorial Fund, 1450, Available online: http://collection.imamuseum.org/artwork/35166/ (accessed on 5 January 2015).

- Teseida: Battle of Teseo and the Amazons; New Haven c.1460. : Yale University Art Gallery (Photo courtesy of the Yale University Art Gallery). Available online: http://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/6082 (accessed on 5 January 2016).

- Apollonio di Giovanni, and Marco del Buono. Teseida: Duel of Arcita and Palemon and Triumphal Procession; Boston c.1465. : Museum of Fine Arts, Bequest of Mrs. Martin Brimmer. Available online: http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/cassone-with-three-painted-panels-31299 (accessed on 5 January 2016).

- Paul F. Watson. “A Preliminary List of Subjects from Boccaccio in Italian Painting, 1400–1550.” Studi sul Boccaccio 15 (1985–1986): 149–66. [Google Scholar]

- Paul F. Watson. “Apollonio di Giovanni and Ancient Athens.” Allen Memorial Art Museum Bulletin 37 (1979–80): 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bernadette Marie McCoy. The Book of Theseus. New York: Medieval Text Association, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Alberto Limentani. Tutte le opere di Giovanni Boccaccio. Edited by Vittore Branca. Verona: Mondadori, 1964, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Janet Levarie Smarr. “The Teseida, Boccaccio’s Allegorical Epic.” NEMLA Italian Studies 1 (1977): 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- James H. McGregor. The Shades of Aeneas. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Robert R. Edwards. Chaucer and Boccaccio. Chippenham: Palgrave, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Carla Freccero. “From Amazon to Court Lady: Generic Hybridization in Boccaccio’s Teseida.” Comparative Literature Studies 32 (1995): 226–43. [Google Scholar]

- Robert R. Edwards. Chaucer and Boccaccio: Antiquity and Modernity. New York: Palgrave, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Disa Gambera. “Disarming Women: Gender and Poetic Authority from the Thebaid to the Knight’s Tale.” Ph.D. Thesis, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA, May 1995. [Google Scholar]

- David Scott Wilson−Okamura. Virgil in the Renaissance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Craig Kallendorf. A Bibliography of the Early Printed Editions of Virgil, 1469–1850. New Castle: Oak Knoll, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Craig Kallendorf. Virgil and the Myth of Venice: Books and Readers in the Italian Renaissance. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas Kelly, and Martin L. McLaughlin. Literary Imitation in the Italian Renaissance. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Paul F. Grendler. The Universities of the Italian Renaissance. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- David Anderson. Before the Knight’s Tale: Imitation of Classical Epic in Boccaccio’s Teseida. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Margaret Franklin. “Virgil and the Femina Furens: Reading the Aeneid in Renaissance Cassone Paintings.” Vergilius 60 (2014): 127–44. [Google Scholar]

- Jennifer Klein Morrison. “Apollonio di Giovanni’s ‘Aeneid’ Cassoni and the Virgil Commentators.” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin, 1992, 26–47. [Google Scholar]

- Trojans Land in Latium and the Battle of Camilla, Turnus and the Trojans; Seattle c.1470. : Seattle Art Museum. Available online: http://www1.seattleartmuseum.org/eMuseum/code/emuseum.asp?collection=27168&collectionname=WEB:European&style=browse¤trecord=1&page=collection&profile=objects&searchdesc=WEB:European&newvalues=1&newstyle=single&newcurrentrecord=12 (accessed on 5 January 2016).

- Apollonio di Giovanni. Death of Camilla and the Wedding of Aeneas and Lavinia. Ecouen: Musée de la Renaissance, 1460, ©RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY; Available online: http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/16021/thesis_shaw_rw.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 5 January 2016).

- Michael Sherberg. “The Girl outside the Window.” In Boccaccio: A Critical Guide to the Complete Works. Edited by Victoria Kirkham, Michael Sherberg and Janet Levarie Smarr. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013, pp. 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Julius Kirshner. Marriage, Dowry, and Citizenship in Late Medieval and Renaissance Italy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Emma Buckley. “Ending the Aeneid? Closure and Continuation in Maffeo Vegio’s Supplementum.” Vergilius 52 (2006): 108–37. [Google Scholar]

- Craig Kallendorf. “Maffeo Vegio’s Book XIII and the Aeneid of Early Italian Humanism.” In Altro Polo: The Classical Continuum in Italian Thought and Letters. Edited by Anne Reynolds. Sydney: University of Sydney Frederick May Foundation for Italian Studies, 1984, pp. 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy Hampton. Writing from History: The Rhetoric of Exemplarity in Renaissance Literature. Cornell: Cornell University Press, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Simon Gaunt. Gender and Genre in Medieval French Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Margaret Franklin. Boccaccio’s Heroines: Power and Virtue in Renaissance Society. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Janet Levarie Smarr. “Speaking Women: Three Decades of Authoritative Females.” In Boccaccio and Feminist Criticism. Edited by Thomas C. Stillinger and F. Regina Psaki. Chapel Hill: Annali d’Italianistica, 2006, pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- F. Regina Psaki. “’Women Make All things Lose Their Power’: Women’s Knowledge, Men’s Fear in the Decameron and the Corbaccio.” In Heliotropia 700/10: A Boccaccio Anniversary Volume. Edited by Michael Papio. Milan: LED Edizioni Universitarie, 2013, pp. 179–90. [Google Scholar]

- Virginia Brown. Famous Women. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen D. Kolsky. The Genealogy of Women. New York: Peter Lang, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Constance Jordan. “Boccaccio’s In−Famous Women: Gender and Civic Virtue in the De mulieribus claris.” In Ambiguous Realities. Edited by Carole Levin and Jeanie Watson. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1987, pp. 25–47. [Google Scholar]

- Louis Brewer Hall. The Fates of Illustrious Men. New York: Frederick Ungar, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 1In ancient accounts of Teseo’s interactions with the Amazons, he voyages to Scythia (often with Hercules), where he then decides to kidnap and marry the Amazon queen. His intentions are not political and her abduction, accomplished in stealth, comes as a surprise to the hospitable Amazons. The Amazonomachy is fought when the viragoes journey to Greece in an attempt to rescue their queen; failing, they simply return to Scythia. For Amazons in antiquity see, for example, [5].

- 2For views representative of those voiced in late medieval and Renaissance conduct manuals, see, for example [6,7]. Relevant modern scholarship on the subject is vast; see, for example, [8,9].

- 3The seminal text on cassone painting is Schubring [10]; Callmann [11] has also done foundational work on Florentine cassoni. For a recent review of scholarship related to the decoration and function of cassoni see [12].

- 4Cristelle L Baskins, interested primarily in situating Boccaccio’s Amazons within the complex Renaissance reception of the armata e bella tradition, discusses Teseida cassone imagery as “illustration” of Boccaccio’s text ([13], p. 33). Although she does not explore the thesis that Teseida literary and pictorial imagery reflect competing ideologies, her observation that Amazons could “serve both as virtuous exempla and blameworthy projections” ([13], p. 38) does not contradict such an argument.

- 5…olio e sapone/sopra lo stuol gittavano a fusone./Battaglia manual nulla non v’era,/perciò ch’ancora non avean potuto/prender li Greci di quella rivera/parte nessuna; e ’l conforto e l’aiuto/del buon Teseo per niente gli era;/anzi pareva ciaschedun perduto,/di quelle donne mirando le schiere/crescere ognora e diventar più fiere./Di dardi, di saette e di quadrella/non fo menzion, che ’l ciel n’era coverto/e occupata tutta l’aere bella,/gittando l’uno a l’altro…([20], 1.52.7–8; 1.53; 1.54.1–4).

- 6…si rivolse a’ suoi con vista viva,/con piggior piglio…“vitupero della gente achiva…“ ([20], 1.61.1–3).

- 7…e quasi uscia per doglia della mente…([17], 1.57.6); Né altramente infra le pecorelle/si ficca il lupo per fame rabbioso,/col morso strangolando or queste or quelle,/fin c’ha saziato il suo disio guloso…([20], 1.74.1–4).

- 8…né in alcuna mai tanto sofferto…([20], 1.54.6).

- 9…perché rari/ve n’eran che nel capo o nel costato/o in altra parte non fosse piagato ([20], 1.55.6–8).

- 10E ’l sangue lor vedevan sopra l’onde/con trista schiuma molto rosseggiare…e qual più cuore aveva or si nasconde,/temendo delle donne il saettare…([20], 1.56.1–2, 5–6).

- 11“Teseo di venir s’argomenta/sopra di noi, avendoci moleste/perché nostro piacer non si contenta/di quell che l’altre, ciò è suggiacere/a gli uomini, faccendo il lor volere” ([20], 1.26.4–8).

- 12“…perciò che mai alcuna offensione/ver lui non commettemmo, onde assaltate/dovessomo essere;/e questa ragione/assai è vota di degna onestate,/perciò che non fa mal que’ che s’aiuta/per raver libertà, se l’ha perduta” ([20], 1.27.3–8).

- 13…donne in Scizia crude e dispietate…([20], 1.6.2). In the opening paragraphs, the narrator, as distinct from the author (whose voice is manifest in paratexts including glosses and a dedicatory letter), recounts the legend that the Amazons killed their menfolk to obtain their freedom.

- 14“…virile animo mostrare…uomini fatti, non femine ardite” ([20], 1.24.5, 8).

- 15…con battaglia spesso le donzelle/assaliva con sua gente sicura;/ma di tal cuor guarnite le trovava,/che poco assalto o altro li giovava…perchè le donne dentro assai sovente/di morte si metteano a ripentaglio,/predando sopra loro arditamente…([20], 1.93.5–8; 1.94.4–6).

- 16“Ma poscia c’hai le tue forze provate,/e ’l tuo pensiero hai ritrovato vano,/diverse vie hai sotterra trovate/per avermi in prigione a salva mano;/…e di combattere in oscura parte/non è di buon guerrier mestier né arte” ([20], 1.106.1–4, 7–8).

- 17Scholarship on the humanist reception of the Aeneid is vast; for recent analysis and bibliography see [27,28].

- 18See also ([30]; [31], pp. 235–72).

- 19See, for example, [22,32].

- 20Esse gittavan fuoco spessamente/sovra l’armate navi, il quale acceso/molto offendeva i Greci; e similmente,/con artifici, pietre di gran peso,/che rompevan le navi di presente/dove giugnean, se non era difeso…([20], 1.52.1–6).

- 21Poco era fuori della terra sito/il teatro ritondo, che girava/un miglio, che non era meno un ditto,/del quale il mur marmoreo si levava/inverso il ciel sì alto, con pulito/lavor, che quasi l’occhio si stancava/a rimirarlo, e avea due entrate/con forti porte assai ben lavorate…dal quale scale in cerchio si moveno,/e cre’ che in più di cinquecento giri/infino all’alto del muro salieno,/con gradi larghi, per petrina miri;/sopra li quali le genti sedeno/a rimirare gli arenarii diri/o altri che facesser alcun gioco,/sanza impedir l’un l’altro in nessun loco ([20], 7.108; 7.110).

- 22“Si come tu hai potuto udir dire,/tutte le donne scitiche botate/furo a Diana, allor che in desire/ebber primieramente libertate;/e tu sai ben quel ch’è contravenire/o non servare alla sua deitate/le cose a lei promesse, che vendetta/subita fa, qual sa quei che l’aspetta…crederei/che fosse il me’, sanza più provazione/fare oramai del poter dell’iddei,/che mi lasciassi a Diana servire/e ne’ suoi templi vivere e morire” ([20], 12.40; 12.42.4–8).

- 23“Questo dire è niente” ([20], 12.43.1).

- 24Michael Sherberg ([37], pp. 105–6) acknowledges the “ideological gulf that separates the lyric Petrarch from Boccaccio” in the latter’s decision to give Emilia a voice that enables her, in her “extraordinary” prayer to Diana, “to lament the paradox of her situation as well as her despair at being the object of undesired desire.” He concludes, however, that though ”the poem operates as a paean…to the catalytic power of womanhood, it also shows that the erotic power of women must submit to good social purpose” ([37], p. 102).

- 25See, for example, [38].

- 26For Vegio, see [39,40].

- 27This is not to suggest that the ‘triumph’, a motif frequently seen in cassone narratives, was always employed in the context of marriage and its societal significance.

- 28Quoted and translated by ([41], p. 21).

- 29See, for example, ([43], pp. 9–13).

- 30For anti-misogynism in Boccaccio’s vernacular work see, for example, [44,45].

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).