1. Introduction

Both urban and rural spaces are saturated with stories. Every day we pass through these spaces we work, walk, live, and breathe them. Moreover, they are multi-textual and often highly politicized. Spectral traces of history ebb and flow in, through, and under the tide of contemporary life. To engage with these stories, this paper explores the use of “deep mapping” as a methodology and aesthetic choice. Deep mapping as an approach to place, aims to democratize knowledge through the crossing of temporal, spatial, and disciplinary boundaries. As a term and concept, has been used as both a descriptor of a certain type of approach to aesthetic representations of place (be they literary, performance based, or geo-representational), and a distinct set of aesthetic practices that can be linked, historically, to a number of diverse practitioners. More generally deep mapping can be categorized as involving intensive topographical exploration that aims to present diverse sources—histories, ecologies, poetics, memoires, and so on—as being of equally valid, and is often used to amplify the voices of marginalised stakeholders, both socially and ecologically. The aesthetic act of deep mapping as a practice, or set of practices is a method of creating a record of space, place or time that commits to an investment in enacting multi-vocal understandings: a “deep” (as opposed to shallow, one sided or perfunctory) investigation of place. “Deep map” first emerged as a literary term after being coined by American travel author William Least Heat Moon [

1]. Moon spent nine years documenting Chase County, Kansas in the plains country of the Midwest United States. In minute detail

1, he meticulously recorded and interwove interviews with locals, botanic information, Native American folklore and histories, literary and archival records, weather reports, geological data and cartographic references with travel writing and personal poetic reflections. As such, deep mapping has often been employed to engage with, narrate, and evoke multivocal, non-linear, open histories of place that are cross-referential. Opening up sometimes surprising resonances and dissonances.

The historical adaptations of deep mapping practices, from literary deep mapping, theatre archaeology, geographic information systems (GIS), and cross-disciplinary based productions, all strive towards more holistic methods of spatial representation. In perhaps its most common form, it is regarded as an intensive topographical research, encompassing spatial narratives, and with an aim to document, through the use of agency and inclusion, the interpenetrations of past and present [

3]. I argue that the practice of deep mapping must be considered as a performative act, and one that can be perceived as a reflection of other concurrent ontological and epistemological trends discussed later in this paper. Karen Barad ([

4], pp. 801–4) suggests a “

performative understanding

2 of discursive practices challenges the representationalist belief in the power of words to represent pre-existing things.” In a performative reading, according to Barad, the focus shifts from “questions of correspondence between descriptions and reality… to matters of practices/doings/actions.” Deep maps go beyond description or simple communication, rather they are an

enaction of place. They offer a certain type of storytelling that seeks to democratise knowledge,

3 through the use of

the map. While this may not necessarily involve mapping in a traditional cartographic sense (although in some cases it does) deep mapping embodies the act of placing information on a plane of representation where the various components are connected metaphorically, and sometimes materially, by inhabiting the space on the same “map”. As such, this mapping process attempts to give different knowledge equal audition or representation; be they botanical, historical, indigenous, folkloric or otherwise. Fundamentally, this seeks to be inclusive across fields and exemplifies an inherent interdisciplinarity.

The move towards a more explicit engagement between cartographic representations in geography through GIS and the arts has becoming steadily prevalent in discourses with arts and geography. Australian artists and academics Petra Gemeinboeck and Rob Saunders [

5], in a critique of traditional cartographic exercises, speak of how the move to digital and GIS have given the illusion of a precise view of reality and suggest by engaging in art practice that apply alternative geographies it is possible to challenge this discourse. They propose that the “critical lenses of cultural, experimental and feminist geography distinguish themselves from cartographic science fiction by their desire for the embodied, multiple and plurivocal” ([

5], pp. 160–62). In opting for this approach, they hope to challenge positivist notions of objectivity and truth. Scottish theorist and artist Iain Biggs ([

6], pp. 5–9), who has written extensively on deep mapping, also draws on feminist theory, suggesting that deep mapping makes contributions to “a new ecology of embodied knowing” and should be seen in the form of “essaying” in the same way feminist reconstruction saw the essay as a “model of resistance”. I read his work as asserting deep mapping as a method of production in which people can begin to see things in a relational way through underscoring the fundamental connectivity of various knowledge orders. The trend of eroding disciplinary boundaries leads geographer Daniel Sui ([

7], pp. 62–64) to suggest that a “third culture” be created, one which embraces the traditional two culture model of arts and science, originally proposed by C.P. Snow [

8] some fifty years earlier where analysis becomes a synthesis, “scientific rigor with artistic sensitivity, and pure intellectual pursuits with dominant societal concerns of our time”. Although, that said, the authorizing knowledge production of science must be tempered in such statements.

This paper seeks to explore how deep mapping can be understood as echoing a trend in ontological practices of connectivity and subsequent epistemological “flattening” of knowledge. Specifically, systems put forward by poststructuralism and cultural theorists, such as Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari, and Bruno Latour, as well as those under the umbrella term of Speculative Realism and New Materialism including Levi Bryant, Timothy Morton, and Ian Bogost. This connection is both a reflection and a refraction, adopting in one sense the underlying theoretic drive but opting for a diverse spatiotemporal descriptor; one that is “deep” rather than “flat”.

2. Trends of Production: Defining Deep Maps

The term deep mapping has been adapted or applied to a number of diverse projects and is becoming an increasingly popular as a signifier and an area of cultural production. Defined by Canadian literary academic Alison Calder ([

9], pp. 164–70) early on as a type of “vertical travel writing”, she explains, it interweaves “autobiography, archaeology, stories, memories, folklore, traces, reportage, weather, interviews, natural history, science, and intuition”. The deep map has been adopted or reinterpreted to become both a methodological and philosophical approach driven by and extending into creative practice, including archaeological research, performance, GIS systems, and large scale art works. Pearson and Shanks([

3], p. xi) and Calder ([

9], p. 165) both suggest deep mapping blurs genres and while the former see it as involving the “recontexualisation of material” the latter emphasizes community as vital to the deep map. Calder ([

9], p. 165) suggests the narrative of deep mapping as being ‘cross-sections’ which provide shifting and contingent readings of both human and natural landscapes. While her discussion focuses mostly on literary deep mapping, Mike Pearson [

3] and Michael Shanks [

10] write on a practice-based deep mapping, a type of environmental, ecological performance ethnography and a disciplinary practice described by Pearson and Shanks ([

10], pp. 20–27) as “archaeological cultural poetics” that attempts to “record and represent the grain and patina of place”. Both interpretations acknowledge that multiple and conflicting narratives connect and underscore this type of cultural production and that these narratives are equally important. It is of interest to note the close association between archaeology and deep mapping as being open to the politics of display and documentation and interrogating the perceived gap between subjectivity and objectivity. This recognition of such pre-existing hierarchies of knowledge and a desire to represent in a way that is more truthful of open multivocal contexts of place is an underlying current typical of deep mapping.

The theorization of both the performance and practice side of deep mapping coalesced through the development of a manifesto, which included ten tenets

4. This arose from collaboration between the two directors of well-established and successful Welsh group

Brit Gof, Clifford McLucas

5 [

11,

12] and Mike Pearson, and American archaeologist Michael Shanks [

13]. The tenets themselves were jointly authored as part of a collaborative research project, called “

Three Landscapes”, sponsored and funded by Stanford University Humanities Center between 1999–2001. It was designed “to generate a creative short circuit between the artist’s studio and the academy” [

12]. These tenets were consequently adopted by Australian choreographer Rachael Swain [

14] who, at the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Conference in 2012, quoted these ten points as being integral to the performances she undertakes as co-artistic director of the highly successful physical theatre company

Marrugeku6. Her group utilises contemporary dance, circus skills, installation, video art as well as traditional and contemporary music in large-scale indoor and outdoor productions. Based in Broome in the far north west of Australia,

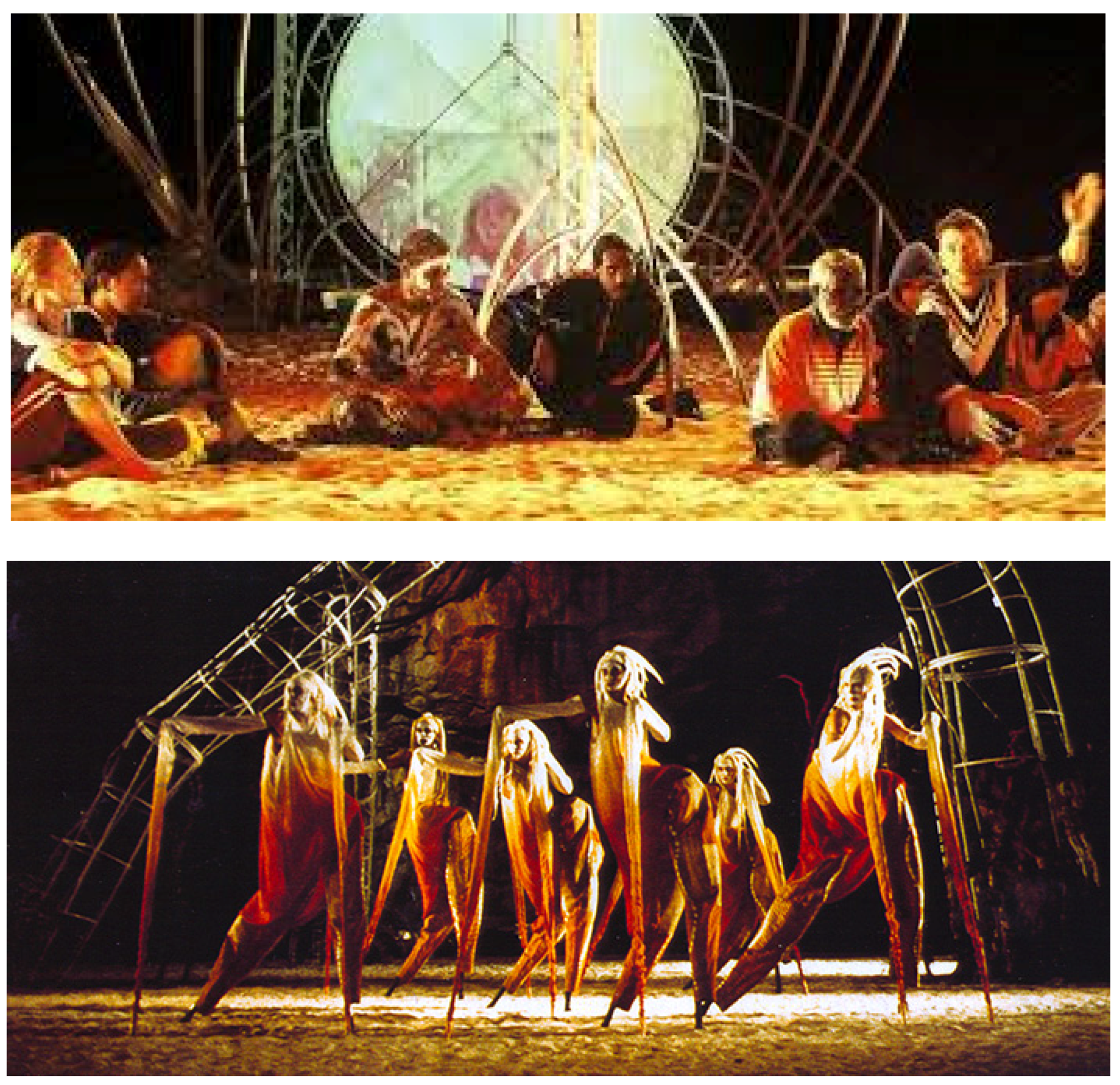

Marrugeku’s works explore intimate spatiotemporal stories through specifically indigenous and cross cultural collaborations and in consultation with community elders. Working closely with Kuwinjku artist and story keepers and the Yawuru people of Broome, the memories, tradition, stories, and lives of indigenous culture can be shared as can be seen in the highly successful

Mimi (see

Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Production stills from Marrugeku production Mimi, Arnhem Land August/September 1998.

Figure 1.

Production stills from Marrugeku production Mimi, Arnhem Land August/September 1998.

These proposed tenets of McLucas [

10,

11] adopted by Swain are useful in furthering my argument for both the performative nature of deep mapping––notably in the sense that it invokes a carrying out of something, as well as according to prescribed ritual––and in relation to how it functions as a democratisation of knowledge by exposing hierarchies.

The tenets of deep mapping as outlined on the

mometo mori site of McLucas, have continues to be influential. Mapping Spectral Traces [

16], of which McLucas was a member, is a transnational and interdisciplinary collective of artists and academics that work creating deep maps. This collective is also linked to a number of international creative, practice led, academic research centres called PLaCE [

17], which “address issues of site, location, context and environment at the intersection of a multiplicity of disciplines and practices”. There is no privileging or authorizing knowledge of one source of information over another and all agents have equal resonance in deep mapping, at least philosophically. The first point of the manifesto relates to the issue of resolution and states that deep maps should be “big”. While this may not necessarily denote a physical size, the act of engaging in a deep map explicates a commitment to a large-scale investigation. The second tenet dictates that deep maps must be “slow” [

12]. In this they call for an immersion in the subject that can only come with, and be actualised by time—not dissimilar to situated knowledge [

18]. Deep maps [

12], according to the tenets must” embrace a range of different media or registers in a…multilayered orchestration and may only be achieved by the articulation of a variety of media”. This is certainly true of the work of

Marrugeku [

15]. According to tenet five deep maps will have at least three elements including a visual element, “a time-based media component…and a database or archival system that remains open and unfinished”. With this he distinguishes in form from literary deep maps and while he lists as time based components film, video and performance—I would argue that sound, notably missing, should also be considered in this list. McLucas [

12] then goes on to list as a necessity the inclusion of both privileged “insider” and the marginal “outsider”, specifically of the “amateur and the professional, the artist and the scientist, the official and the unofficial, the national and the local”. This strongly suggests an equal status of knowledge in the narratives of deep mapping.

McLucas [

12] proposes deep maps are only now possible as different orders of materials may be easily combined within modern digital media practices. This is a discernable divergence from literary deep mapping. Whether this tenet is strictly true is debatable, as spatial representation can be manifested in numerous ways––not all necessarily digital. Although, that being said the popularity of GIS as a way of deep mapping must be noted. However, the penultimate tenet of McLucas’ manifesto do reflect the sometimes political or ethical ideals underlying wider deep mapping practices, namely:

Deep maps will not seek the authority and objectivity of conventional cartography. They will be politicized, passionate, and partisan. They will involve negotiation and contestation over who and what is represented and how. They will give rise to debate about the documentation and portrayal of people and places.

This is true of the work of PLaCE [

17] who, as part of their mission, describe their work as focussing on the creation of a “supportive, open-ended space”. They are interested in considering how they may engage, respectfully, in creative and research practices which employ “mapping” that seeks to “honour unacknowledged pasts and presences, and imagine more socially just futures.” Their projects focus on employing visual and performing arts to address “such relevant concerns as ecological activism, place-based memory work, trauma, postcolonial geographies and related topics”. Not unlike the underlying theme in the work of Least Heat Moon’s [

1]

Prarie Eryth mentioned earlier which weaves historical, social, ecological, and indigenous narratives. Similarly, Rebecca Swain’s collaborative work with co-director Dalisa Pigram [

15] strongly ties in indigenous contestations in her performance theatre choreography and thematic explorations through works such as

Mimi (see

Figure 1),

Gudirr Gudirr and

Cut the Sky [

15]. Now, let us consider one project of PLaCe that also works within an Australian context,

The Stony Rises Project [

19]. The presence of indigenous culture both in the past and in the present sense in a multi-tiered way is also poignantly included in this project. Run between 2008 and 2010, the work was expressed on manifold platforms including an artist camp, a travelling exhibition, a book, and in the community. Through the individual perspectives of a team of artists, scientists, designers, historians, curators and theorists,

7 they collectively created a deep map of a particular region (the Stony Rises near Lake Corangamite) within the Western District of Victoria, Australia. The investigation of one place and its features led to multiple histories being uncovered and shared.

This interpretation is in line with a more general rendering of what constitutes “deep mapping” and in particular can be seen as a way of de-colonizing. In each case traditionally prosaic modes of representation are combined with a particular place-conscious poetic that is socially and ecologically engaged. What I see as being clear from these examples is that creating a deep map is an act of undoing, a performative act that connects diverse disciplinary modes of enquiry and production, and blends ethics with aesthetics. The final tenet of McLucas alludes to the openness and humble nature of deep maps; rather than being a declaration or avowal they are to be considered a conversation. As such, various enactions of deep maps aim to present place as always open to the addition of supplementary voices, democratically positioning existent past, present and future knowledge and, thereby, building a structure of connectedness.

3. Mapping Ontologies of Connections and Flattened Epistemes

A recognition of connectedness in diverse epistemological approaches of deep mapping—which I perceive as abounding in a greater ontological trend of connectedness—traces pathways between the micro and the macro, the poetic and the prosaic, and past and present narratives. Let us begin by drawing comparisons with the work of French philosopher Bruno Latour [

20,

21]. I will deal first with his concepts outlined in his methodological paradigm:

i.e. actor network theory (ANT). Through his ANT, Latour warns against neat “sizing”. That is, nesting, or perhaps more clearly identifying micro processes within macro; a practice that according to Latour ([

20], pp. 14–28) is a confusion of scale, and runs the risk of making leaps of cognition or oversimplifying causality. This could be equated with a top down systems logic, whereas Latour ([

21], p. 175) states the micro should be examined

alongside the macro, rather than as existing “above” or “below”. Latour advocates slowing the investigative process down so as to trace the connections, which may have been previously considered “micro” to that which is “macro”. The interactions and connections each actor makes are equally important in this system. This is echoed in the theoretical application of deep mapping, which calls for an unhurried investigation, a concerted effort to listen to and seek out multiple voices connected to place. Latour ([

20], p. 15) warns against making assumptions or declarations without asking the all-important: “but why?” He suggests this is only achievable by slowing down and examining the minute interactions that connect the so-called micro with the macro. In this way it is possible to explore how existent human and nonhuman actors represent a kind of agency, and how these work in exchange with and on each other. In relation to deep mapping it becomes an enaction of place in so much as that it puts into practice material explorations of the multitudinous exchanges that occur within such spaces. Perhaps most significant epistemological understanding here is the recognition of human and nonhuman actors as active rather than passive in ongoing mutual exchange processes. Concurrently, deep mapping processes map plurivocal agents that are to be considered as both connected and equal in import.

While Latour ([

20], pp. 165–72) instructs to

flatten the landscape or to

render it flat in order to begin to understand the topography, he also, argues against “sizing” and “zooming” that give what he terms “false frames”. By frames I understand him referring to conditions that impose restrictions to the possible connections or circumstances which may occur outside of the imposed frames. The flattening does not necessarily imply an elimination of depth then, but rather a democratisation of knowledge; for him, functionally, there is no pyramid of power. Latour ([

20], p. 19) argues that “size and zoom should not be confused with connectedness”. The use of what I refer to as

flat ontology (a term initially borrowed from Manual De Landa [

22], and further discussed by speculative realist Levi Bryant [

23]), is something that is evident across a number of postmodern, poststucturalist and social constructivist discourses of the last half a century. It is a trope that argues against a hierarchical configuration. This may be understood as a democratisation of knowledge ordering. In this paradigm each “voice”, be it historical, social or spanning diverse disciplinary understandings is equally audible or valid within the system. It points to a synchronous structuring with a focus on how the network is coordinated. This allows the importance of ongoing communications to be privileged, and the decentralisation of a single “objective” voice. This type of egalitarian connectivity can also be seen in the work of Deleuze and Guattari [

24] who posit epistemes based on a rhizomatic structure or trope, eschewing the classic arboreal model––one which is inherently hierarchical––and enacts mapping rather than a tracing. In

Rhizome Deleuze ([

24], p. 12) writes “what distinguishes the map from the tracing is that it is entirely oriented toward an experimentation in contact with the real. The map does not reproduce an unconscious closed in upon itself; it constructs the unconscious”. Rather than understanding being mapped neatly on a tree-like structure, a complex network of connections, each as important as the other, is made to explain ecologies, or complex systems of interrelatedness. Metaphorically, this is a flattened plain of connections. This also works to break down binaries of definition. No longer are we fixated on structured existing binaries of man [sic.] against nature, good

versus evil, dominance

versus submission, mind over body; rather what is to be highlighted is an intractable web of connectivity, inextricably bound together. Many theorists cited in this article––including Ian Bogost, Bruno Latour, and Graham Harman (amongst others)––argue that this dissolution of dualistic opposition is a reaction to the post-enlightenment or post Kantian philosophies, whose legacies are grounded in such dichotomies and hierarchical taxonomies. Similar to feminist theory, it argues against positivist notions of objective absolutism that are to be rejected. Tendencies are describes rather than causalities and personal narratives and testimonials are accepted as valid. Relatedly, feminist theorists Rick Dolphijn and Iris van der Tuin [

25] understand New Materialism as being “transversal”, specifically stepping away from dualism and representationalism to explore an active theory-making which interrogates paragdigms, spatio-temporality and the boundaries of disciplinarity. Interestingly, to tie into previous discussions connected to deep mapping Shanks ([

26], p. 1) outlines archaeology as being distinctly materialist in terms seen as “a collection of what people do”, rather than a “set of ideas or a body of knowledge”, ideas which were formulated in dialogue with Latour, and Deleuze and Guattari whilst Shanks was in Paris.

Relevant to the modus of deep mapping––which is open to, or inclusive of, poetic, imagined or felt knowledge––are those of the Speculative Realists and Object Oriented Ontologists (OOO) [

26]. Levi Bryant [

23], Graham Harman ([

27,

28]), Ian Bogost [

29], and Quentin Meillassoux [

26], amongst others, bring into play the idea of “flat ontology”. This is discussed in line with the theoretical assertion of this paper, the act of flattening knowledge systems can be read as a fundamentally democratizing action concurrent with the etho-ecological approach of deep mapping when applied to thinking about place. However, there is a distinct ethical or even political underpinning to most deep mapping projects that is missing from flat ontology. Particularly in the case of OOO, in which conceivably everything are deemed “objects” and nothing has special status––be it plate tectonics ([

29], p. 9), an enchilada, the Taj Mahal, an iceberg ([

29], p. 8), or digestion;––nonhumans, humans, and even ideas, for example, are all considered as being worthy of the same kind of philosophical metaphysical investigation. This assertion is to be understood not simply in a correlationist ([

29], p.11) way––through their relation to humans––but as an equally important voice within discourse, rather than things being “elevated

up to the status of humans” the whole system of objects are flattened to an egalitarian stasis. Not all loosely-bound members of OOO are strict adherents to a flat ontology [

30]––Timothy Morton’s ([

30], pp. 1–24; [

31]) posthuman “hyperobjects” for example, nuclear radiation, global warming, the Internet or the Earth are considered far greater in scale, time and, ultimately, importance than humans––there is still a flattening in the respect that the anthropocentric hierarchical model is abandoned. In such a system the centre of determination is not necessarily human but rather “object” oriented. The difference from some of these speculative realists to the theoretical models put forth by Deleuze and Guattari [

24,

32], and Latour [

20] is that objects are presented as possessing unique qualities in and of themselves—that is, having properties unknowable to humans, and existing independently of humans. The emphasis is shifted to being on the connection they may have with both other non-human and human objects. However, where they do align, work towards shifting the metaphysical centre away from the singular human/ego, or even simple centralised node or hub of understanding. In this way denying the presence of a powerful nucleus or privileged standpoint from which all else can be defined is simply displaced or given realignment. Similarly, deep maps seek tend to deliberately dissipate the concept of a solid centre by actively generating pluralistic narratives. While the impetus to speculate flat ontological understandings inherent in OOO methods, there is a danger however, that by granting equal status to all objects you run the risk of losing any nuance of an increasingly necessary ecological (and ethical) argument. So while the electric massage chair, on a flattened ontological plane may have the same metaphysical complexities as the iceberg, do we offer the same amount of energy to debating or investigation of the demise of each? While humans, theoretically speaking, may be regarded as of no more importance than space dust, we are in a world where pressing social and environmental concerns require our action and thought. Similarly, while the idea of a flattened ontological ordering may on appearance be seen to be a democratising action, in effect, we might also detect an anti-humanist position, even if utopian. The power to flatten can appear to largely come, from a position of privilege. (The human is undoubtedly a privileged species). This must be seen as distinct to the democratising ideologies of deep mapping, which seeks to flatten hierarchies that are specifically social or ecological in nature.

Undeniably, there has been an ongoing, sometimes explorative, discursive shift away from an anthropocentric imagining of the world to one that is increasingly aware of the importance of non-human actors, both biological and ecological. I would propose, that the act of deep mapping has the potential to be inclusive of ecological as well as social concerns and work towards creating conversations that change the way people perceive, think about and ultimately engage with place. While this may not always be true of all the projects that carry the title of “deep map” it is something, which works within the framework of its ideology.

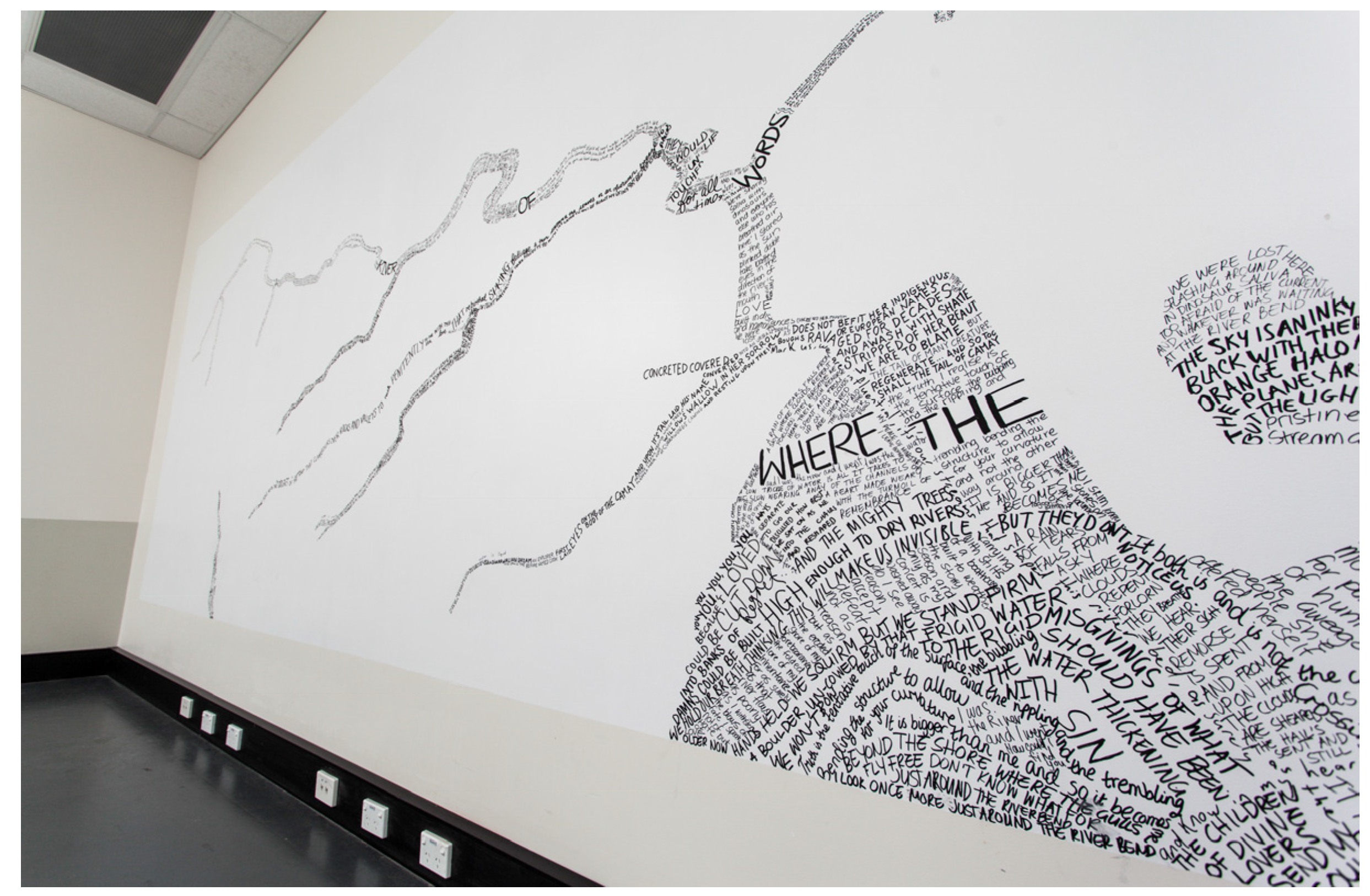

4. Deep Mapping the River

In my own work, I am seeking to explore the significance of a site through its permutations, and by the process of deep mapping in a consciously performative way. My own interpretation of deep mapping has evolved through engagement with an ongoing sound art project about the Cooks River, an urban river system in Sydney, Australia. The project offers a suite of works that use multiple sources including archival research, interviews with locals, and a range of stakeholders such as botanists, ecologists, environmental scientists, as well as collaborations with spoken word poets and field recordings of the river—both ambient and subaqueous. In these investigations, I have attempted to adhere to the philosophical and ethical drives of deep mapping by seeking out these multiple voices and research into geological and ongoing indigenous histories. These multiple layers coexist, to combine in different ways, media, and permutations in an attempt to create a deep map of the river.

To label a place as urban is often to discount the underlying topography of the urban/natural boundary. Liminal zones where natural and urban environments combine, and the stories of these zones, have often been shaped and scarred by an anthropocentric idea of the urban that is separate from its underlying natural ecology. This label can ignore the land it was built on, or the native flora and fauna that sometimes continues to share space with concrete and bitumen; and the rivers, creeks, and waterways that sustained life in the area for millennia have not always dried up, but can be found in the deeper strata, or as new diversions. Viewed in this way, the liminal status of urban rivers becomes not a deficiency; rather the stories of their becoming can be new and productive sites for exploration. Concomitant with Henri Lefebvre’s [

33] work on rhythm analysis, it is not merely the place which is significant, but how the site has been conceived of over the years, taking into account not only the

here and now, but also rhythms that work over expanded time, not unlike the ebb and flow of the river. It would be impossible to investigate the Cooks River without taking into account the attitudes that shaped it over time, as collective imagined history moulded and continues to mould its identity and behaviour. The river in itself, a material signifier, is not simply the visible water but extends to include all the catchment. The gaze of humans over time has determined, to a large extent, the flow of the river and its ecological well-being. It has been viewed as water source, sacred country, sewer, drain, channel and is slowly returning to river. Through the enactment of a process of “deep mapping” the river, diverse and conflicting identities can be incorporated to create a rendering of place that aims to be both open, democratically located, inclusive of human and non-human actors and reflecting historic, narrative, and poetic imaginings. The following image (

Figure 2) is from one of these projects made as part of a residency at the Bankstown Arts Centre and in collaboration with members of the Bankstown

8 Poetry Slam, who wrote and performed works inspired by ecological and historic stories of the river and their personal experiences. These words were then written literally into a large-scale mask of the river (see

Figure 3). The mask was then removed, leaving the words behind echoing its shape and tributaries. The recorded works were then mixed into an accompanying sound piece that was installed into the exhibition space and experienced alongside live performances from the poets.

Figure 2.

Installation still Where the River Rises: A River of Words. Created in collaboration with Bankstown Poetry Slam. Approx. 2.5m × 6m 2014 (Photo by Christopher Woe).

Figure 2.

Installation still Where the River Rises: A River of Words. Created in collaboration with Bankstown Poetry Slam. Approx. 2.5m × 6m 2014 (Photo by Christopher Woe).

Figure 3.

Installation still Where the River Rises: A River of Words. (Photo courtesy of artist).

Figure 3.

Installation still Where the River Rises: A River of Words. (Photo courtesy of artist).

As touched on before this particular work forms only one layer of an ongoing palimpsest deep mapping project, it signifies the site where the river rises. It incorporates the tenets of deep mapping by working towards the inclusion of sometimes marginalized voices and poetic imaginations, and presents these as a recontextualisation of place. The performative enaction of this type of thinking about the river works to both locate and generate new and diverse imaginings in the collective stories generates by/in the presence of the river.