1. Introduction

“Imagine that in a few hundred years’ time humanity has put aside all its misguided supernatural beliefs and turned its religious instincts to the Earth, the true author of our being. Then a rite will be called for to celebrate this thoroughly realist and romantic-materialist cult of the Earth. This rite will be the Visiting of Places, to contemplate them in all their particularity.”.

This description of a “rite” associated with the secular contemplation of place presents a very telling knot in the author Tim Robinson’s thought. He is, of course, an atheist who dismisses religion’s “misguided supernatural beliefs” here. Such beliefs are, for him, too transcendental, too dependent on any other world than this. However, there is something lingering in the religious outlook that holds his fascination. Though religion itself is not for him, there is nothing wrong with our “religious instincts” which might simply be re-deployed into this “realist and romantic-materialist cult of the Earth”. The subtitle of his first book is

Pilgrimage, though it is a pilgrimage “with eyes raised to this world rather than lowered in prayer” ([

2], p. 25). There is a pattern here. While he rejects the supernatural, there lingers a ritualised exploration of place suggesting veneration for its hidden dimensions, for its more-than-immediately-apparent meanings. As such, place still presents a metaphysical question for Robinson, but a question about immanent rather than transcendent metaphysics. The key to understanding Robinson’s distinctive, secular metaphysics, however, is in his fascination with space, not place: “I prefer this body of work to be read in light of ‘Space’ […] somatic space, perceptual space, existential space and so on,” he describes, “ultimately there is no space but Space, ‘nor am I out of it’, to quote Marlow’s Satan, for it is, among everything else, the interlocking of all our mental and physical trajectories, good or ill, through all the subspaces of experience up to the cosmic” ([

1], p. vi).

Place and landscape are the themes with which his writing is more readily associated, grounded in that “particularity” he mentions above. However, place and landscape might simply be the most concrete ways to apprehend the more labyrinthine and metaphysical exploration of space itself, one that extends deep into perception, subjective experience, memory, community, history, knowledge, and even a variety of disciplinary expertise. One way of thinking about deep mapping is as a form of

working the social and cultural medium of place—carefully and deliberately manipulating the relationships between these various and “interlocking” depths and fields that our social life opens up—and in this sense the medium of place, for Robinson, is “Space”. There are a great many definitions of space and place to draw on today from phenomenological to Marxist geographers but this article draws its definitions from Robinson himself in reference to his own distinctive spatial thinking. Contrary, for example, to a philosopher, such as Edward S. Casey, for Robinson, it is “Space” that is primal in our universe, not place. Whereas, for Casey, space and time are concepts abstracted out of the immediate place-world, for Robinson, place is preceded by “Space”; it contains

and is contained by “Space” [

3]. I am not arguing necessarily for the truth of this view, but rather setting out, at the beginning, the distinctive spatial premise on which Robinson’s thought it based and from which his wider practice emerges.

Robinson is not an author alone, and before he was an author he was a maker of maps. But before he was a maker of maps, he was also an artist practicing under the name of Timothy Drever, preoccupied with abstract and geometrical forms and their relationship with the spaces of exhibition and the art-going public, with topographical and with social space. In more ways than one then, space precedes place in his work. When we understand his career as more than writing alone, as a practice that has art at one end, map-making in the middle, and writing at the other, we see that space itself is the medium with which he has been working all this time.

Robinson was born in Yorkshire and studied mathematics at Cambridge before leaving England to travel and explore a career in visual art, living for periods in Istanbul, Vienna and London. However, at the very point when his career as the artist Timothy Drever was gathering momentum in London, he left, turning his back both on the city as a cultural centre and on visual art as the medium in which he would work. In 1972 he and his wife moved to the Aran Islands off the west coast of Ireland in the mouth of Galway Bay where they lived for over ten years before moving once again to the village of Roundstone on the coast of Connemara where he still lives today. Since this dramatic move west he has created several editions of new maps of the Aran Islands, the Burren, and Connemara (what he calls his “ABC of earth-wonders”) ([

1], p. vi). The Aran maps in particular were the first to have been made since the Ordnance Survey had attempted to do so as a part of the British government’s colonial administration in the mid-nineteenth century. When he began to produce these maps it was out of an innocent curiosity as to whether it might be possible “to make amends”, correcting the misplacement of topographical features and the mistranslation and Anglicisation of Gaelic place names that had taken place under the British and in which he had detected a “carelessness that reveal[ed] contempt” ([

1], p. 3). The research undertaken for the maps soon led to what he called the “world-hungry art of words” and he is now the author of a two volume study of the Aran Islands a three volume study of Connemara, two editions of miscellaneous essays mostly exploring the same places, and a volume of short fiction and experimental writings. These works, as John Elder has suggested, have earned Robinson “a permanent place on the shelf that holds the scientifically informed, speculative and at the same time highly personal narratives of such earlier masters as Gilbert White and Henry David Thoreau” ([

4], p. 1).

The relationship between his map-making and prose is well known and something that he has reflected on frequently in the books. However, there has been little reflection on the relationship between all

three aspects of his career—the maps, the writing, and the earlier visual art

1. This is despite his having exhibited at some quite prestigious galleries in the 1960s and 1970s

2, his selection for exhibition at a John Moore’s Biennial in Liverpool by a panel of judges featuring Clement Greenberg in 1965 ([

5], p. 44), and despite there even being a print of his still to be found in the Tate Gallery archives in London today [

6]. By looking a little more closely at the relationship between this neglected alter ego, Timothy Drever, and the more familiar Tim Robinson, a comprehensive picture appears of the developing practice of a quite singular, inquiring mind, one capable of very striking leaps of faith in pursuit of his elusive subject matter. “Deep mapping” as an emerging form of artistic and academic practice offers perhaps the most appropriate critical framework through which to consider Robinson’s work like this

in full without segregating any one aspect of the work such as his writing, as other studies have (very illuminatingly) done [

7,

8]. Deep mapping may also be the only appropriate description of precisely what he has been doing in the west of Ireland since 1972.

The early work of Tim Robinson that this article discusses took place largely before the (practice-led) theorisation of “deep mapping” by figures in Europe such as Ian Biggs [

9,

10], and Mike Pearson, Clifford McLucas, and Michael Shanks [

11]. It even precedes the moment when the idea of it was called forth from the work of Wallace Stegner by William Least Heat-Moon [

12] in the American tradition. Nonetheless, the way that deep mapping, in the UK especially, has formulated itself

in practice does suggest a reflection on the curious historical relationship between it and Robinson’s work. Not least of all because, for Ian Biggs in particular, Robinson is singled out as a figure who “anticipates” deep mapping, part of a thread that Biggs traces back through John Cowper Powys to Thoreau ([

10], p. 11). Reading Robinson’s work holistically as “deep mapping” rather than just as writing also encourages us to draw attention to aspects of the work that have involved a wider, committed social engagement, the germ of which emerges from certain tensions that were there in his early artistic practice. Deep mapping is at heart a form of place-making, or place-transformation. It recognises that the identity associated with place is not a matter of essence, stability, and boundedness but of work, life, and creative energy. It explores new dialogues between the variety of perspectives with which a place is invested, past and present, though with an emphasis on “constructive reconciliations in the present” ([

9], p. 5).

The terminology associated with the practice of deep mapping—and it is crucially to be understood

as practice—can be read along a continuum of verbs that enact an engaged cultural work associated with this transformation. Drawing on Biggs again, deep mapping “intervenes”, “challenges”, “destabilizes”, “mediates”, and “reconfigures” “existing territories and presuppositions” ([

9], p. 5). It offers a form of resistance to prevailing conventions of place representation and a recovery of the rich but underappreciated cultures going overlooked. As such it has to it a fundamental inclusiveness of attitude and often a quite radical “heterogeneity” of outcome ([

11], p. 166). This is often a matter of nurturing the less visible “small heritages” (to borrow an eloquently plural term from David Harvey)—that can be anything as small as a field name, a superstition, or pneumonic—by a range of means ([

13], p. 20). Tim Robinson’s body of maps and written work, understood within the wider context of his whole artistic practice, can be read along a similar continuum insofar as they have endeavoured to engage with an intangible and oral topographical culture damaged by a colonial legacy and often found to be precariously balanced on the edge of memory.

Biggs has described deep mapping not just as interdisciplinary but as “challenging the very distinctions between academic and artistic outcomes” ([

9], p. 5). In doing so, academic research and artistic practice often work collaboratively to produce what he calls “a potent catalyst for social change” ([

9], p. 5). As will become apparent, Robinson’s artwork, maps and the accompanying books represent a sustained form of cultural heritage and conservation work that operates along very similar lines. His achievements have now been celebrated by the people of the places themselves, by a highly commended citation in the British Cartographical Design Awards in 1992, and by a European Conservation Award, recognising the work of his and his wife Máiréad’s company Folding Landscapes, in 1987 [

14]. These are significant forms of recognition for a socially engaged practice of place-based heritage work that goes beyond the literary achievements for which he is best known.

In what follows, I explore Robinson’s preoccupation with space through the three key aspects of his career. In the first part, his early experiments with the geometrical spaces of autonomous abstraction in a particular strain of modernism in the visual arts are shown to expand in conflicted ways out into the public and social sphere at a crucial time of political awakening in London in the 1970s. This conflicted expansion is then shown to be the guiding influence in his navigation through this very unusual exploration of map-making in Ireland which begins to challenge the conventional sense of cartographic space and explore more inclusive and non-standardised forms. In the third part, this same line of developing spatial thought and practice is traced from cartographic to linguistic forms of space as language is found to be able to do what neither the art nor the map could. The article concludes with a reading of a particular prose aesthetic of “consilience” in the written work which, it is argued, can be understood as the culmination of Robinson’s spatial practice and thought. Finally, I argue that his work not only anticipates deep mapping but also exceeds it and extends it in a distinctive, literary direction. While a reflection on this career-long development of a line of spatial thought and practice will offer a uniquely full reading of Tim Robinson’s work, at the same time, it aims to reveal something about the wider kinds of twentieth century cultural history out of which “deep mapping” might be understood to emerge, as well as looking toward the future in offering a reflection on the nature of its wider spatial practice where space itself becomes a social and artistic medium.

2. The Art: “A Bridge into the Real World”

In 1996, Robinson was asked to take part in an exhibition at the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin. It had been nearly twenty-five years since he had left the London art world and turned to map-making and the literary essay. Nonetheless, the work he chose to exhibit brought together his earlier visual art with his mapping and writing in an interesting way that demonstrated a certain surprising coherence of thought. In the middle of the room, scattered on the floor like large pick-a-sticks were what seemed to be surveyors’ rods, some with equidistant black and white stripes, some just white with a single inch painted grey at different points on the rods, and above them, suspended by a splayed rainbow of thread, was one more yard-long white rod. The lines on the black and white rods were not, however, all equal, suggesting a certain divergence from the standard that they brought to mind. On the walls around them were two of his intricate, hand-drawn maps of the Aran Islands and of Connemara, and between them were some twelve extracts from his books

Stones of Aran: Pilgrimage and

Setting Foot of the Shores of Connemara and Other Writings [

15]. After visiting the exhibition, a friend described the surveyor’s rods on the floor as “measure become organic” (quoted in [

15], p. 11). It is an interesting phrase in which there is a sense that the measure has somehow lapsed or that it has been overcome from the inside. The phrase has an echo of “gone native” to it, since what use is measure if it is not answerable to a universal standard? There is something absurd and paradoxical about these surveyors’ rods, each with its own measure and none of them bound by the same proportions. The white rods with a single inch painted grey at different points were called “Inchworm”, a name for the caterpillar form of the geometer moth, so called because, according to Robinson, its movement in small loops seems to “measure the Earth” ([

15], p. 57). Again, there is something absurd about the idea of an animal that might measure to no purpose other than travel. The measurement is not recorded or abstracted but simply performed. Life as lived is the only measure of which these rods speak. They

are a standard rather than appealing to one. There is something very strangely prescient in this installation, the rods of which, were created originally before Robinson left London in 1972 and had been in storage all the while. They seem to have within them the kernel that would grow into his remapping of the Aran Islands, the Burren and Connemara, refusing the standards of the nineteenth century Ordnance Survey and asserting a form of spatial autonomy.

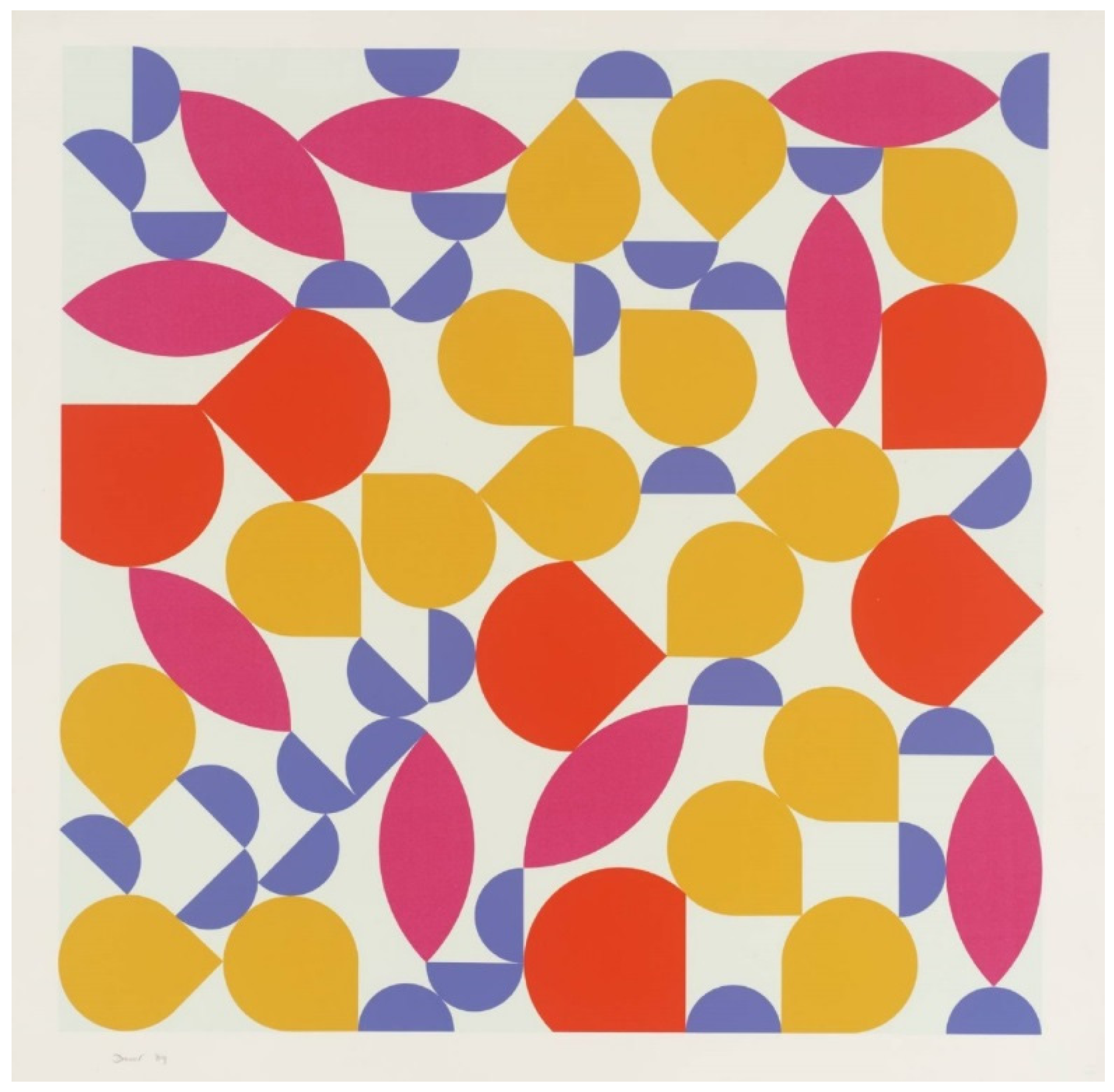

The level of abstraction and the subtle but philosophical commentary on space that we see in the rods here was characteristic of Robinson/Drever’s London work of the time, though of course without the accompanying maps and writing. In the 1960s, modernism had returned to the London art world reconstituted by American intellectuals like Clement Greenberg who, since 1939, had been defending a purist abstraction and the avant-garde in a way that we might imagine could appeal to Robinson’s background in mathematics. For Greenberg, abstraction narrowed and raised art “to the expression of an absolute” in which “subject matter or content” had become “something to be avoided like a plague” ([

16], p. 531). This led, he suggested, to “free and autonomous” work, pure painting or sculpture, “valid solely on its own terms” ([

16], p. 531). As mentioned, Greenberg had been among the judges who selected Robinson/Drever to exhibit in the John Moore’s Biennial in Liverpool in 1965 and other exhibited works of his from around the same time also show a fascination with geometry and mathematical proportions. For example, the print that remains in the archive of the Tate Gallery in London is one, the form, composition and proportions of which were produced by a strict adherence to certain geometrical principles and rules (see

Figure 1). As he describes in an exhibition catalogue from the time, “aesthetic choices were progressively replaced or limited (and so made more crucial) by geometrical demands” ([

17], p. 15).

Figure 1.

Timothy Drever. Untitled. 1969. Tate Gallery.

Figure 1.

Timothy Drever. Untitled. 1969. Tate Gallery.

However, there was also an emergent pull away from the “autonomy” of abstraction at this time and it is this subsequent tension between the two that would propel him out of London in 1972. For an exhibition in the summer of 1969, he and the artist Peter Joseph published an essay in

Studio International called “Outside the Gallery System”. In it they voiced their dissent at an art world bound up with commodity fetishism, suggesting that this “increasingly isolates the artist from the public”, channeling work “at best into a museum, at worst into an investor’s cellar”, leaving the artists themselves to a “comfortable enervation” ([

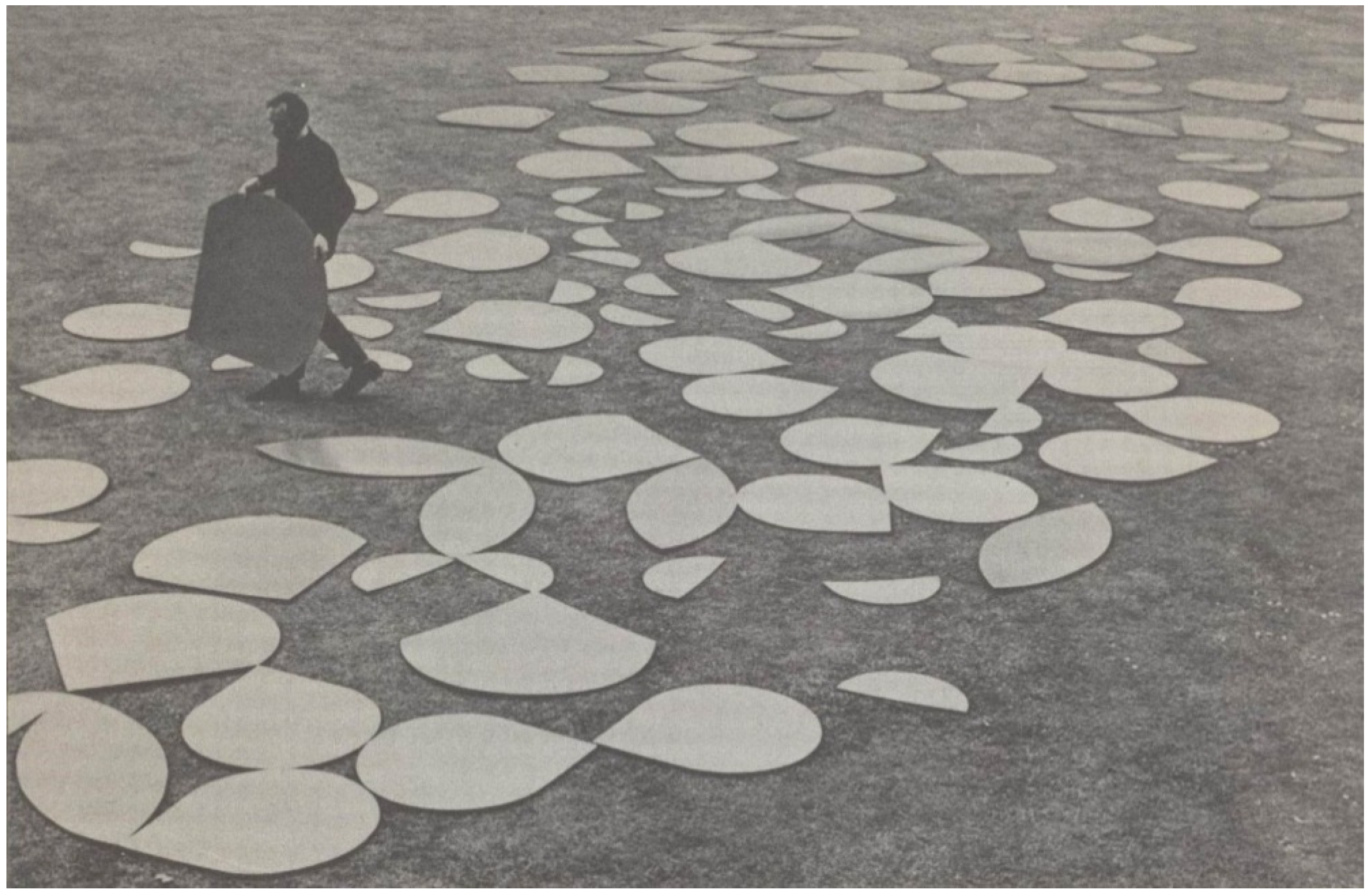

18], p. 255). Robinson/Drever and Joseph set about challenging this by holding their exhibition outdoors in the grounds of Kenwood House. Not only this but the art they exhibited relied on the interaction and participation of visitors to be fully realised. “Consideration of the environment is essential”, they declared, “the scale and dynamics of the work must relate to the area in which it is shown. Thus, it seems natural that ‘environmental art’ should be not just the latest fad of the art-world, but a bridge into the real world” ([

18], p. 255). Robinson’s own exhibition piece was a series of large, flat, coloured shapes produced, again, according to geometrical rules, but here they were set down on the lawn and he invited the public to move, reorder, and experiment with new compositions to bring the work alive (see

Figure 2). This echoed a previous interactive installation that he had exhibited indoors at Kenwood House the same year called “Moonfield” where visitors were invited to enter a darkened room with a black floor only to find their feet knocking black wooden shapes on the floor which they were encouraged to turn over revealing a white underside. As people made their way through the room new patterns of black and white emerged dependent on their physical interaction. “Moonfield is thus a new surface to be explored, and this exploration creates its topography”, the exhibition catalogue claimed ([

17], p. 5). This topography that was created through the interaction between artist, artwork, and public was described as a “real space both in philosophic and social terms” ([

17], p. 17).

Figure 2.

Timothy Drever. Four-Colour Theorum. Kenwood, 1969.

Figure 2.

Timothy Drever. Four-Colour Theorum. Kenwood, 1969.

Both of these works demonstrate the fascinating paradox of an artist working in forms of autonomous abstraction while at the same time expressing a yearning for the social engagement and interaction that abstraction had spurned. In the case of the outdoor exhibition at Kenwood House, there was also clearly a disillusionment emerging with the conventions of the gallery-oriented metropolitan art world. Deep mapping itself can be seen to emerge from a similar uncomfortable feeling about the lines drawn between an “art world” and a “real world” though it has also grown to challenge the lines separating an “academic world” as well. On the one hand, this “environmental art” was not then what we might expect it to be today, “environment” referring simply to the nature of the public space of exhibition. It was simply about finding, quite concretely, new environments for art and encouraging real human interaction through which the visitor takes part in the process of creation. However, the decision to search for a new environment does speak of a frustration with the prevailing spatial discourse of exhibitions and recognition of the need to question its hegemonic hold on the relationship between artist and the public. This seems to parallel a growing realisation at the time of modernism’s own waning political antagonism. Alan Sinfield reminds us how easily Greenberg’s defence of the autonomous freedom of the abstract expressionist was co-opted into an ideology threading through a number of C.I.A.-funded European exhibitions that served as propaganda in the Cold War ([

19], pp. 210–14). By bridging the art world and the real world, or rather by making that bridge out of the art world and “into the real world”, connecting the gallery with wider, more democratically public, environments, and with questioning the social and economic implications of setting a work in a metropolitan gallery, Robinson himself has noted that there may have even been the beginnings for him of an “environmental art” in the sense that it is more readily understood today ([

20], p. 4). In his essay “Environments” in that same edition of

Studio International in 1969, the performance artist Stuart Brisley asks: “[t]o what extent does the artist maintain responsibility for the implications implicit within his artistic processes beyond production?” suggesting that the commodification of art ought

not to be something of which the artist passively disapproves while continuing to feed ([

21], p. 267). For Brisley, as perhaps for Robinson/Drever at that time, “environmental work specifies that the artist take a positive position in relation to his own behaviour as it affects other people within the social and physical context” ([

21], p. 268).

It was during this same period that Clarrie Wallis recalls the first “walk-as-art” taken by the young Richard Long and Hamish Fulton, a conscious decision to turn their backs on the city as authoritarian centre of culture. She quotes from Long’s diary of 1967:

We announced we were going to walk (at a normal pace) [...], out of London until sunset. A few didn’t start. We went along Oxford Street to the Edgware Road—the Old Roman road of Watling Street—which we followed in a more-or-less straight line north-west out of London. A few more people dropped out along the way, leaving about six of us at the end. We had no preconceived idea of where we would end up; in fact at sunset we found ourselves in a field, not lost, but also not knowing exactly where we were. The first place we came out to was Radlett, so we caught a train back from Radlett station.

(quoted in [

22], pp. 42–43)

Here, the walk-as-art appears an eccentric student experiment influenced no doubt by student marches of the earlier 1960s. However, there is something very carefully thought out about this, the spatialization of a train of thought or feeling that encourages us to read this walk as a performance, even a tenuously constituted sculpture. Wallis has gone so far as to describe this moment as representative of a “shift in consciousness [...] the end of Greenbergian modernism and the beginning of a new era. It coincided with a turning point away from technological optimism to preoccupations with ecology, conservation and a crisis of the 1970s as the British were uneasily forced to face their post-industrial and post-colonial future” ([

22], p. 38). In many ways this walk, through the very area where Robinson was living at the time, can be seen to parallel his own departure from London for Aran along a similarly north-westerly axis just a few years later

3. Both moves offer a performative rejection of the capital at a key time, a rejection of what Raymond Williams has critiqued in modernism as the “persistent intellectual hegemony of the metropolis” ([

23], p. 38).

It was after seeing Robert Flaherty’s film

Man of Aran (1934) that Robinson and his wife decided to make the move. The film is a strange blend of documentary anthropology and dramatized narrative, but it was the film’s sheer Romanticism that appealed to them at the time: windswept cliffs, a life lived between rough limestone and the Atlantic Ocean on the outer edge of Europe. There could have been nowhere further from the modernist metropolis. Nonetheless, though such Romanticism might have been the initial appeal, it should be noted that Aran became for them not an escape

from the world so much as an escape

into a new world. Theirs was not a move of retreat from social and cultural politics and Robinson would be drawn to the complex political, international, and economic tensions that ran through the life and history of the islands just as J.M. Synge had before him. When Yeats offered that famous advice to Synge in the early twentieth century—“Give up Paris [...] Go to the Aran Islands. Live there as if you were one of the people themselves; express a life that has never found expression” (quoted in [

24], p. xix)—Synge found a way of life and culture richly alive with the language, history and folklore that had already become so important to a burgeoning sense of Irish national identity. He found, in the cottage of Páidin and Máire MacDonncha, not rural isolation but what had come to be known as

Ollscoil n Gaeilge (the University of Irish) due to the number of scholars that had stayed there for their research ([

25], p. xvii). Synge also found it a very poor place, exploited by ever rising rents set by legislation decided upon in Westminster, a place in which people were being evicted from their homes ([

25], p. 143). Though Robinson had not read Synge before he left, this sense of the Aran Islands as a centre of culture in their own right, connected by a long and complicated history to Britain, was something he would very soon come to discover.

In the first few years of living on the islands, Robinson attended an exhibition of Richard Long’s in Amsterdam and found on the poster one of Long’s sculptures photographed on Aran in 1975. Long had also spent a summer there but they do not seem to have met at that time [

26]. He also describes himself and his wife catching sight of one of Long’s sculptures from a plane window when they were returning after a trip away, “an instantly recognisable mark that told us who had visited the island in our absence” ([

2], p. 44). In fact, he actually gets into a dispute when Long is “aghast” to find two of his stone-works marked on Robinson’s map of the island (quoted in [

27], p. 113). “[T]he essence of his works”, Robinson concedes, “is what he brings home to the artworld: a photographic image in many cases” which serves as “the entrypoint to a concept, the idea of a journey” ([

27], p. 115). Robinson reminds Long that, nonetheless, he does in fact leave something behind, something that he, as a maker of a very detailed map, could only find it hard to ignore. The tension is here once again between abstraction (“the entrypoint to a concept”) and a more tangible real-world social interaction (the stone-work left behind). For Long, the pull back to the metropolitan centre from the periphery was still strong and where the work reached its final realisation, but for Robinson, who was by that time beginning to map the islands and recognise them as a centre in their own right, that “bridge to the real world” was coming to look final.

3. The Maps: “Making Amends”

On the south west coast of Aran, at the base of its two-hundred-and-fifty-feet limestone cliffs, there is a cave called An Poll Dubh, or “the black hole”, in which a piper is said to have wandered, never to be seen again. The folklore of the islands has it, though, that inland, under the village of Creig an Chéirín, his music can still sometimes be heard. It is a story that occurs across England as well, though sometimes in the guise of a fiddler rather than a piper. Jennifer Westwood and Jacqueline Simpson tell of a group of people in the village of Anstey in Hertfordshire, for example, who were curious about how deep a local cave went so they sent a fiddler below ground, playing his fiddle, while they walked above ground listening as a way of plotting the depth of the cave in the known landscape. In a horrible twist, the music stops suddenly as the fiddler is taken by the Devil and never heard of again while his dog comes running from the cave with its hair burned off ([

28], pp. 332–33). Similar stories are associated with Grantchester in Cambridgeshire, Binham Priory in Norfolk, Peninnis Head in the Isles of Scilly, and Richmond Castle in Yorkshire. The story becomes something quite different in Robinson’s hands. Though it is not clear whether this is because of its particular inflection in the memory of the islanders or because of a certain license he takes himself (more than likely it is both), the sense of a community collaborating with the piper is stripped away and he is reported to be exploring the cave alone. The function of his music in the story becomes a little more mysterious too, as in Aran it shifts from a means of mapping the cave to merely a haunting vestige of a disappeared man. Robinson absorbs this story into a personal mythology in

Stones of Aran: Pilgrimage and we get a curious glimpse of the lone, questing artist, literally immersed in place, but somehow searching for something more mysterious within it as well:

Thus: the artist finds deep-lying passages, unsuspected correspondences, unrevealed concordances, leading from element to element of reality, and celebrates them in the darkness of the solipsism necessary to his undertaking, but at best it is a weak and intermittent music, confused by its own echoes and muffled by the chattering waters of the earth, that reaches the surface-dweller above; nor does the artist emerge; his way leads on and on, or about and about.

It is an image in which we can certainly read feelings about his remote and isolated existence in those early years on the islands, perhaps even a certain alienation from the place itself, coupled of course with a fear of being literally swallowed by it. And yet, there is a paradox that emerges in this image as well. The “darkness of the solipsism necessary to his undertaking” is, in fact, not a darkness of solipsism at all. It is a darkness that belongs to both the island’s geology and its folklore. Robinson’s account of a supposed interior, subjective space is contradicted by its origin in the island’s own cultural repertoire, the recognition of what was, in fact, a shared cultural space. Though the community who trace the piper’s movement from above ground are stripped away from this story then, nonetheless, in the “weak and intermittent music” that does make its way to the “surface-dweller” we can see the beginnings of a tentative emergence of the artist to his social context. The withdrawn autonomy of Drever the modernist artist was beginning to unfold his fascination with abstract space into the manifest reality of the island’s cultural landscape as it was encountered by Robinson the hoarder of place lore.

He had begun collecting the place names, stories, and histories like this after Máire Bn. Uí Chonghaile, the postmistress of Cill Mhuirbhigh, suggested that he make a map of the islands. He was surprised to find that no map had been made since the Ordnance Survey’s nineteenth century project which had produced impractical, large scale maps, copies of which were difficult to get hold of. He did, nonetheless, acquire copies and began studying them. He learned Gaelic, still then the first language of the islands, and spent a lot of time visiting his neighbours, walking with farmers and fishermen, and talking at length about the topography and its associated history and culture over tea. He soon found that the maps were full of errors, not just of mistranslation and Anglicisation but also of misattribution. As he began to collect place names and understand the stories and histories associated with them, the rich depths of life and heritage that had been ignored or misunderstood, and that often existed only in the memory of a few ageing individuals, he began to understand that, for the officials planning the survey from Westminster, “rents and rates came before any other aspect of life” and for many of the soldiers conducting the survey on the ground, the “language of the peasant was nothing more than a subversive muttering behind the landlord’s back” ([

1], p. 3). We can imagine the appeal of correcting these mistakes, and of exploring the possibilities of reparation that might be involved with representing, for the first time, the actual geographical complexities he was discovering in getting to know his neighbours. He was, after all, an artist emerging from a movement that Stuart Brisley had described as in search of that “positive position in relation to his own behaviour as it affects other people within the social and physical context” ([

21], p. 268).

Looking at early cartography up to the medieval period, Michel de Certeau reminds us that there was once a much closer relationship between the map and linguistic description than there is today. Early maps were often written on with accounts of tours, histories, or itineraries of pilgrimages ([

29], p. 121). Their two dimensions offered up stories of the mapmaking process; but, he says, these stories were slowly shouldered out to make way for more purely visual-spatial description. The history of the map “colonizes space; it eliminates little by little the pictural figurations of the practices that produce it” in favour of the top down, precisely surveyed representation of static space dotted with symbols that we have today ([

29], p. 121). This erasure of the stories of the landscape from the official representation is nowhere more felt than Ireland. Too small to have developed its own map-making tradition before the English came with theirs, Ireland did nonetheless have its own rich linguistic geography:

dinnseanchas, the oral tradition of keeping the lore of the land. Charles Bowen describes

dinnseanchas as “a science of geography […] in which there is no clear distinction between the general principles of topography or direction-finding and the intimate knowledge of particular places” ([

30], p. 115). He goes on: “Places would have been known to them as people were: by face, name and history […] the name of every place was assumed to be an expression of its history” ([

30], p. 115). Unlike the increasingly spatial mapping practices of the English, this method had a temporal and historical depth to it and existed, not on paper, but in memory and social interaction.

From the 1520s the English government began commissioning maps of Ireland. Begun as they were, just before such a trend of recording linguistic description began to die out in the 17th and 18th centuries, these first maps do in fact contain a few of these examples of the kinds of place lore Bowen refers to actually written onto them in the style of the medieval maps that de Certeau describes. J. H. Andrews tells us that on the Dartmouth Maps of 1598, for example, there is the description: “O’Donnell camped by this logh where his men did see 2 waterhorses of a huge bigness” ([

31], p. 202). Or the following even stranger piece from the same map: “In this bog there is every whott [hot?] summer strange fighting of battles sometimes at foot sometimes wt horse, sometimes castles seen on a sudden, sometimes great store of cows driving & fighting for them” ([

31], p. 202). This was, however, the exception to the rule and such curiosities should be read alongside derisive illustrations of “wild Irishmen peeping from behind rocks” and in the context of a brutal colonial rule ([

31], p. 202). Additionally, as Andrews explains, what there was of this practice soon died out as main roads were introduced and maps of Ireland began to endeavour to be more objective for the purposes of administration, achieving a certain regimented abstraction. A concern for the Irish

dinnseanchas would not be seen until briefly the Ordnance Survey set up its Topographical Department charged with the collection of heritage information in 1835. Even this, however, was brought to an end in 1842 on the basis that it was “stimulating national sentiment in a morbid, deplorable and tendentious manner” (quoted in [

32], p. 287). In the English mapping of Ireland a certain living history was erased from the map before it ever really found its place on it.

For Robinson, the work that began to present itself was a matter of collecting and identifying the correct place names, representing them on his map in the correct place, and then subsequently recording the stories associated with them in supplementary written material. The map and the book together seemed the only logical way of making a record of a place so linguistically alive. Patrick Curry has called this “a kind of Edenic naming in reverse”, a recovery of a world beneath the English language that had imposed itself ([

33], p. 13). In an interview Robinson describes a typical example of the kind of work he was beginning to undertake:

A very striking case was a place name that was recorded down at the south-eastern corner of the big island. It was something like “Illaunanaur”. The surveyors had obviously thought that the first part of it was “oileán”, island, when in fact it should have been the Irish “glean”, glen. But apart from making it an island when it was a glen, the rest of the name “-anaur” meant absolutely nothing in English phonetics. But in the Irish the name means “the glen of tears”—it’s exactly the biblical phrase “this vale of tears”, “Gleann na nDeor”. And the story I heard from the local people, was that, in the days leading up to the famine when there was a lot of emigration from the islands, those emigrating would get a fishing boat to take them over to Connemara and they’d walk 30 miles along the Connemara coast into Galway, where they’d wait for one of the famine ships heading for America. These ships used to sail out past the Aran Islands and very frequently had to wait in the shelter of the islands while a gale blew itself out. So they would be stationary just a few hundred yards off shore from this place, Gleann na nDeor, and people would come down to that little glen where they could wave to their loved ones but not talk to them. So the name had immense resonances and told you an immense amount about the personal griefs behind the statistics of the famine.

It is not at all unusual that such a small name as Gleann na nDeor should contain such an elaborate and interesting story. Thinking of this coastal place as a “vale of tears”, a phrase used in Christian theology to describe the world that must be endured before the soul can pass on to Heaven, suggests a poignant sense of hope about the life that might await relatives making their way to America. Yet unmapped, such names were slipping out of memory and there are numerous examples of intriguing names that Robinson is unable to find an explanation for. He describes this work as a kind of “rescue archaeology”, gathering things in from the outer edge before they are lost forever ([

1], p. 13).

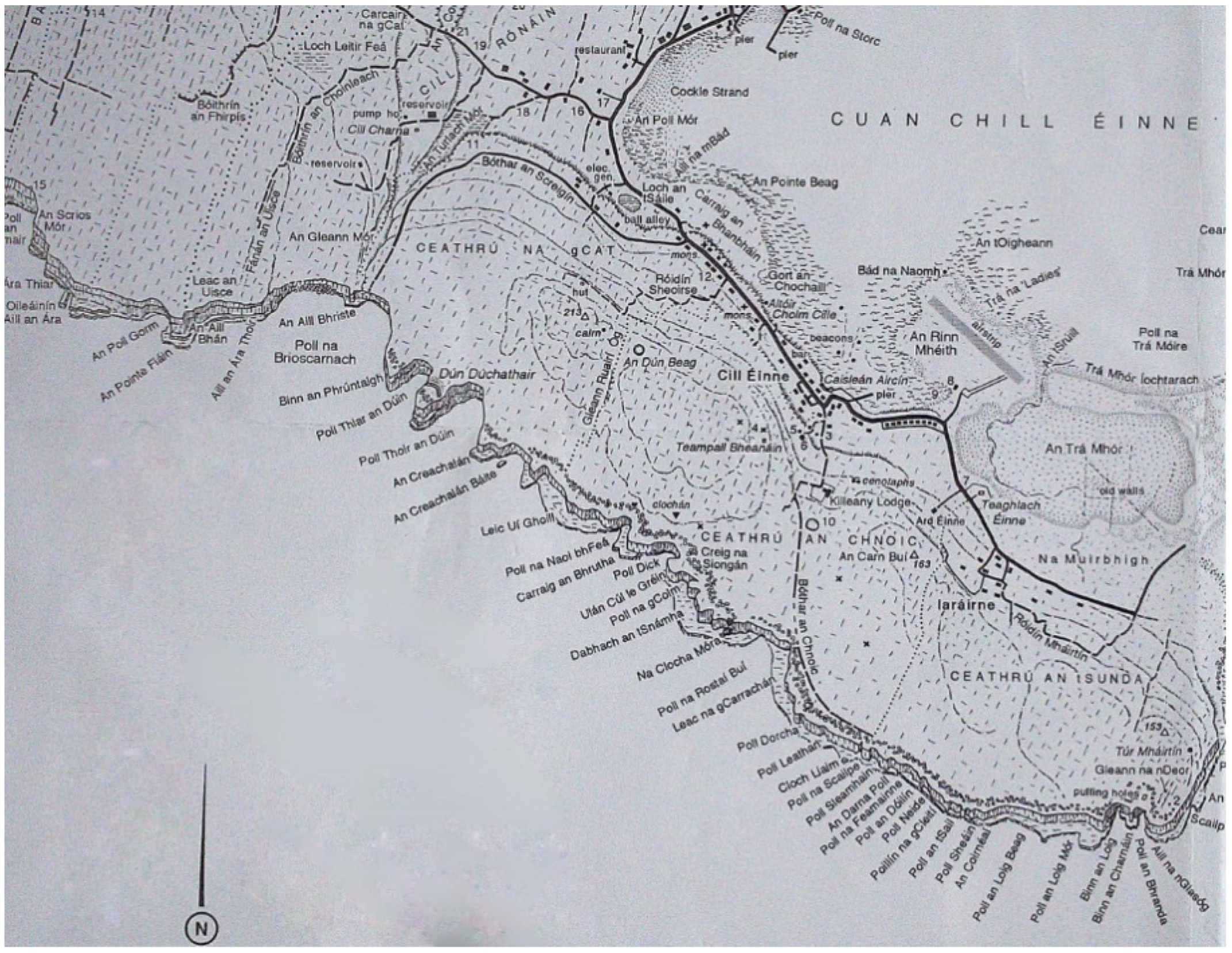

As for the form of the map itself, he set about exploring something that would be importantly founded on the place itself. In a sense he was liberated by being able to tailor his map to so specific and small a location. The rules he worked by did not have to conform to so abstract or generalised a standard as those of the Ordnance Survey. For example, on its south-west side Aran is all cliff and on its north-east all beach, so the angle of vision that looks down on the island in his map is tilted slightly to the south west—what he calls a “seagull’s-eye perspective”—thereby capturing the shapes of the sea-cliffs (see

Figure 3) ([

34], p. 38). This was important to a fishing culture that navigated by these shapes, and that had their own names for many of the headlands that differed from the inland names that farmers had for the same features. By making his such an isolated study, Robinson was enjoying a freedom of singularity, beholden to no distant, administrative standard, something that of course recalls the surveyors’ rods he had created in London in 1972.

Figure 3.

Map detail of south-east coast of Árainn. Folding Landscapes.

Figure 3.

Map detail of south-east coast of Árainn. Folding Landscapes.

Such flexibility, though, also stemmed from the belief that all attempts at mapping are in some small way absurd, “a sustained attempt upon an unattainable goal”, and that this nagging ambition towards objectivity might find its peace with something closer to the personal artistic vision ([

1], p. 77). At his most personal he even playfully includes an image of his dog on the map where it kills its first rabbit, and of a badger that he stumbles upon in the Burren. As he describes in a later essay on Aran:

“This horde of men who tramped over the countryside with theodolites and chains so adequately measured its lengths, breadths and heights that I am free to concentrate on that mysterious and neglected fourth dimension of cartography which extends deep into the self of the cartographer.”.

Recognising the straightforward mathematical survey offered by the Ordnance Survey, Robinson sees his role as populating that Euclidian space with something more psychological and personal. The idea of a personal space, though, also becomes the space for historical, cultural and narrative depth, all of which comes to oppose the international standard of imperial space. The personal becomes an assertion of freedom from that standard which resonates with the island’s own freedom from imperial rule.

Whilst these maps are the work of an individual artist, their collaborative element arising from interactions with a broad range of people and their knowledge and memories of the places, meant that Robinson came to view the maps as taking on “aspects of communal creation” ([

34], p. 35).

In fact, it was recently discovered that while writing the content for his first book on Connemara, Robinson would publish his findings in the local newspaper, The Connacht Tribune, and has described the response:

I had no idea quite how much attention was being paid to them until quite well into the process I found that everyone was waiting for me to turn up. They were quite indignant if I hadn’t turned up to them. And they’d have all their information absolutely on the tip of their tongue ready for me. I’d say in a sort of diffident way: “O I’m the man from Roundstone who’s making the map”, and they’d immediately start “O himself has a stone he wants to show you”, “the name of that hill is such and such.”.

In a range of different ways the “aspects of communal creation” really did involve the communities. The maps became expressions of collective experience, a folding together of discrete forms of knowledge and memory, what David Harvey calls “small heritages”, a plural term articulated in contradistinction to the idea of an “Authorised Heritage Discourse”, and both the maps and the books together began to constitute a new cultural space that could openly contain really quite diverse variegations ([

13], p. 20). The openness of this process found itself very eloquently expressed in a recent exhibition of his Aran map in London. In 2011 Robinson was invited to exhibit in Hans-Ulrich Obrist’s “Map Marathon” at the Serpentine Gallery alongside Louise Borgeoise and Ai Weiwei. His contribution was a twenty-two foot vinyl print of his map of the Aran Islands laid on the floor. Come and walk on it, he invited. Come and dance on it. Come and write your name, or your message on it. Pens were provided and people did. The map has gathered all kinds of annotations now, recalling the earlier public participation of his work at Kenwood House but also giving a useful visual metaphor for all those different public contributions that his vision of Aran, the Burren, and Connemara has accrued over the years [

35].

4. The Writing: A Quest for Space

“Space”, as Robinson describes it, is his preoccupation ([

1], p. vi). Aran and Connemara we might more readily and more comfortably describe as

places but, as was suggested in the introduction, they have become sites in his work for investigating the wider question of space itself as well. Seamus Deane, in a review of the Aran books, suggested that they represented “not perhaps a quest for Aran but a quest to which Aran gives shape and meaning” ([

36], p. 9). The nature of space itself is what the wider “quest” has been for in Robinson’s work, a quest made all the more intricate by the inward, subjective recesses, the outward, subjective projections, the historical depth, the community feeling, the disciplinary varieties, and the imaginative possibilities, of space in its fullest understanding. The early geometrical spaces that his artwork explored in London, when he was just beginning to invite public and social interaction, found themselves complicated by the two clearly contested and “interlocking” spaces that he uncovered in Aran in tensions between the islands’

dinnseanchas and the Ordnance Survey maps ([

1], p. vi). Space as plural, contested, and yet common, at one and the same time became an experiential reality for him through the map-making and it wasn’t long before a growing interest in different, more complex, forms of space began to shoulder out his previous interest in Euclidean conventions.

In the book that completes his

Connemara trilogy,

Connemara: A Little Gaelic Kingdom, Robinson addresses precisely this interest, taking, “as a source of metaphor and imagery”, the fractal geometry of Benoît Mandelbrot ([

37], p. 252). He is prompted to do so by Mandelbrot’s 1967 essay “How Long is the Coast of Britain?”, which he applies to the intricate folds and convolutions of the Connemara coastline showing that the more closely it is observed the greater the answer until the answer becomes nigh infinite. When he writes of the intricate and changing coastline of this landscape, it is increasingly with a realisation of the inadequacy of Euclidean geometry to represent its complexity. Not only this, but we begin to hear an echo in the language suggesting a parallel with the inadequacy of the Ordnance Survey to represent Irish culture. The land is described as “largely composed of such recalcitrant entities, over which the geometry of Euclid, the fairytale of lines, circles, areas and volumes we are told at school, has no authority” ([

37], p. 249). And again, coastlines are “too complicated to be described in terms of classical geometry, which would indeed regard them as broken, confused, tangled, unworthy of the dignity of measure” ([

37], p. 249). The lack of “authority” chimes with the book’s earlier part on Connemara’s histories of political and cultural rebellion and the mention of something “confused, tangled, unworthy of the dignity of measure” could as easily describe the English bafflement and contempt for the Irish

dinnseanchas as it describes here a mathematical difficulty.

The depths and complexities opened up by fractals can be read also as a way of understanding the manner in which language came to take over the exploration of certain spatial depths that cartography could not capture. The spaces of stories and histories are a part of that “interlocking” of “all our mental and physical trajectories” that he suggests when he claims that “ultimately there is no space but Space”, a part of the community’s or the culture’s intersubjectivity, that empathic belief in a common lifeworld shared by others ([

1], p. vi). While few would disagree that our distinctive knowledge, memories, and experiences of space are “interlocking”, what Robinson is curious about is the manner in which this “interlocking” takes place, the manner in which it

might potentially take place, and the role that writing can play in working with the textures of this common but plural “Space”. It is in this sense that his interest in “Space” has gone beyond the safeguarding of a body of oral history knowledge precariously balanced on the edge of memory and perhaps that his work has come to exceed and extend the work of deep mapping as well as anticipate it. At least, it draws attention to space as a social and artistic medium rather than as an area or volume in such a way that may be useful for deep mapping as it develops its practice.

In a recent essay he tells us that for a good many years now he has been building a computer database on CD-ROM of all the topographical knowledge he has been collecting, a way of indexing and preserving the research in a more detailed manner than the paper maps allow and in a more systematic manner than the literary books allow. In this essay—called “The Seanachaí and the Database”, where “

seanachaí” comes from the same root as

dinnseanchas—he begins to weigh the strengths and weakness of his database against the strengths and weaknesses of the

dinnseanchaí (or “keeper of topographical knowledge and lore of place”) ([

38], p. 46). He finds that the database “transcends” the local inhabitant’s mental gazetteer “in powers of recall and logical organization”; it is searchable and it has no limit to the amount of information it can store ([

38], p. 47). However, the database falls far short when it comes to “ambiguous or doubtful data” and “as a memorandum of lifelong inhabitation” ([

38], p. 47). The

dinnseanchaí is not simply a vessel containing historical and cultural information but perceives and creates meaningful relationships between the different parts of the retained lore; he or she is capable of ordering or reordering the history and lore according to values related to that lifelong inhabitation. This is echoed in Ian Biggs’ claim that deep mapping’s preoccupation with bringing the past to light always has an eye on the contemporary as well and on necessary investigations and productions of meaning “so as to enact constructive reconciliations in the present” ([

9], p. 5). Though Robinson does not make such a claim himself, it is precisely this lively negotiation of relationships and the capacity to create meanings that we see in his writing, and that distinguishes it from the maps and the database.

The capacity of his prose to draw on detailed knowledge of, for example, botany, archaeology, folklore, geology, and history, all in the same chapter or essay—his attempt at “interweaving more than two or three at a time of the millions of modes of relating to a place”—shows something more deliberate and creative than the bringing forth of peripheral and precariously located knowledge that we find in the maps and their accompanying booklets ([

2], p. 363). It shows an attempt to make the discrete layers of space belonging to different disciplinary perspectives known to one another and present to one another for the reader. There is a creative practice in this, reaching into the imagination of the artist at one extent and into the cultures with which a given place is invested at the other. This gives rise to two identifiable traits in his written work. Firstly, as Pippa Marland has shown, there is an extraordinary range of experimental writing styles through which he moves, self-reflexive moments of pastiche and parody, mischief and humour, moments of elaborate construction suddenly undermined by irrepressible self-doubt, all of which engage with the often overwhelming possibilities available to an author seeking to do a kind of literary justice to place ([

8], pp. 19–21). This variety of registers is something that Susan Naramore Maher describes as characteristic of the form of writing associated with deep mapping in the United States, and something that she reads through Mikhail Bahktin’s writings on heteroglossia and the dialogic imagination in William Least Heat-Moon ([

39], p. 7). However, secondly, there is a more consistent and identifiable formal trait in Robinson’s recurrent endeavour to relate and intertwine distinctive perspectives on place, looking for what he calls, after E. O. Wilson, “consilience” ([

20], p. 10). The abiding question that he puts to the test again and again is “can the act of writing hold such disparate materials in coexistence?” ([

2], p. 210).

One such example of this we have in

Connemara: The Last Pool of Darkness in which he describes the large cleft in the hillside that forms the valley of Little Killary near the coast. Here in the land’s unusual geology “ancient uncouth states of the earth have been broken through and thrust one over the other” ([

40], p. 2), then gouged and worn away by glaciers. At the head of the valley there is a chapel and well dedicated to the little known St Roc where people used to bring their dead for funeral rites. Local folklore explains the dramatic landform by suggesting that it was here that St Roc struggled with the Devil: as the Devil tried to pull him away to Hell on a chain, St Roc resisted “so violently that the chain cut deep into the hillside, creating the pass and funerary way” ([

40], p. 2). “Thus geology reveals itself as mythology,” Robinson claims. However, it was also on the edge of Little Killary that Wittgenstein once stayed during a period of retreat from Cambridge while struggling with the philosophical argument about “the difference between seeing something, and seeing it as something” (the famous example is of the shape that appears as a duck from one angle and a rabbit from another) ([

40], p. 1). This particular branch of Wittgenstein’s thought has huge significance for Robinson insofar as different perceptions can give way to different explanations of place residing in the same “Space” (“there are more places within a forest, among the galaxies or on a Connemara seashore, than the geometry of common sense allows” ([

37], p. 252)). So Robinson suggests: “In some future legendary reconstitution of the past it will be Wittgenstein’s wrestling with the demons of philosophy that tears the landscape of Connemara” ([

40], pp. 2–3). Here, mythology, geology, and philosophy are all brought into a resonant proximity by geographical and historical association and intertwined through the narrative of the essay. Wittgenstein’s own problem about seeing something as something else is playfully deployed and perhaps even celebrated by revealing a literary form of the duck/rabbit diagram in the form of geological rift/St Roc’s struggle/Wittgenstein’s struggle. It is this prose trait that recurs throughout the writing in different forms and that Robinson describes as a form of “consilience”.

For E. O. Wilson, consilience is a means of bringing the, predominantly scientific, disciplines together in the joint endeavour of expanding the horizons of human knowledge but it too has a relationship to the religious past for him:

We are obliged by the deepest drives of the human spirit to make ourselves more than animated dust, and we must have a story to tell about where we came from, and why we are here. Could Holy Writ be just the first liberate attempt to explain the universe and make ourselves significant within it? Perhaps science is a continuation on new and better-tested ground to attain the same end […] Preferring a search for objective reality over revelation is another way of satisfying religious hunger.

There is, however, an important difference here. Wilson’s understanding of consilience is fundamentally teleological with religion fumbling in the dark behind us and the light of scientific explanation on “better-tested ground” ahead of us (theologians might find themselves irked by the thought that religion is a naïve form of scientific endeavour). However, Robinson’s understanding of consilience is not so teleological and is, instead, interested in the thoughts that appear as different layers of knowledge coincide, as different ways of seeing the same thing “as something” multiply its phenomenological and intersubjective possibilities. Robinson thinks like an artist, Wilson like a scientist. As Wilson himself suggests, somewhat reductively, “the love of complexity without reductionism makes art; the love of complexity with reductionism makes science” ([

41], p. 54). Michael Quigley has also suggested that “no book containing such a vast amount of detail on such a small portion of landscape could possibly be sustained were it not for its intrinsic literary quality” ([

42], p. 117). The artist and the cartographer eventually find a curious fulfilment of their quest for richer and richer forms of space in the contours and possibilities made available through language and the literary imagination.

Robinson has described the “base-triangle” of his philosophy of space as “that formed by the three church-towers of Proust’s Martinville”. ([

1], p. 19) The “base-triangle”, in cartography, is the measure from which all other measures are unfolded, one triangle after another. For the Ordnance Survey this first base-triangle was a precise measure taken with extraordinary care over a two-month period with help from members of the Royal Artillery on Hounslow Heath in the summer of 1791 ([

32], pp. 124–26). From that measure the survey worked outwards until it had taken in the whole of the British Isles. For Robinson, the reference to Proust suggests something much more deeply felt and subjective that is related to the impulse to write. The mysterious intensity of feeling that Proust describes upon watching from a coach window the triangulation of Martinville’s two church towers with Vieuxvicq’s one ignites in his narrator the need to write a response. The sense “that something more lay behind that mobility, that luminosity, something which they seemed at once to contain and to conceal’ wrenches open an irresistible need to respond creatively which, once fulfilled, produces feelings of extraordinary elation ([

43], p. 184). Robinson’s suggestion, then, that this moment in Proust serves as his own “base-triangle” expresses a very primal and mysterious response to what a place might at once “contain and conceal” then (and we might think back to the image of the piper in the cave again here). It alludes, again, to an immanent metaphysics. Part of what a place contains and conceals for Robinson is, of course, these “interlocking” spaces both of historical depth and diverse subjective and disciplinary perspectives. It contains these, but it also contains the endlessly deferred promise of a total form of spatial revelation, a revelation implicit in the very idea of concealment itself.

The central philosophy, introduced in the first Aran book, but running through both of the Aran books, is Robinson’s idea of “the good step”, an ideal, single footfall that traverses a portion of the earth while somehow containing an unthinkable awareness of all possible ways of knowing the place it is traversing, what he describes as an “unsummable totality of human perspectives” ([

2], p. 8). The “good step” is an aspiration to do a form of cognitive and spatial justice to a given place, to unlock it spatially. It is an ideal realisation, if not revelation, of all that is “contained and concealed”. It is, of course, he declares, “inconceivable” in the end but this does not prevent it, as an ideal, from shaping his attitude to the next step

ad infinitum, honouring the impulse to reach for and respond to the contained and the concealed even if the revelation may only ever be partial ([

2], p. 363). What is particularly interesting about this process of always partial revelation is the creative and imaginative work that is required to bring it about, particularly the way that it is the creative imagination of the prose essay and its aesthetic of consilience that brings the different spatial layers into productive contact with one another for the reader. It is in this sense that space takes on the qualities of a social and artistic medium, one worked over by language; worked in the sense that it is

produced, but with an effortlessness that gives it the impression of

revealing its own nature instead. It is through this interesting overlap between the production of space and the revelation of space that we learn something about the work of deep mapping by reflecting on Robinson’s career. Deep mapping explores a means of place-based social transformation but Robinson’s practice shows that this can happen fruitfully through creative and inclusive work at the level of space, when space is privileged as something with a psychological texture, a social fabric, and a cultural value, as a medium invested with and constituted by multiple perspectives at the intersection of history and community.