Beyond Vision: The Aesthetics of Sound and Expression of Cultural Identity by Independent Malaysian Chinese Director James Lee

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sound Aesthetics in Malaysian Cinema: Cultural Resistance and Representation in Independent Film

2.2. Cultural Identity and Sonic Practices in James Lee’s Filmmaking

3. Research Methodology

4. Coding Process

4.1. Open Coding

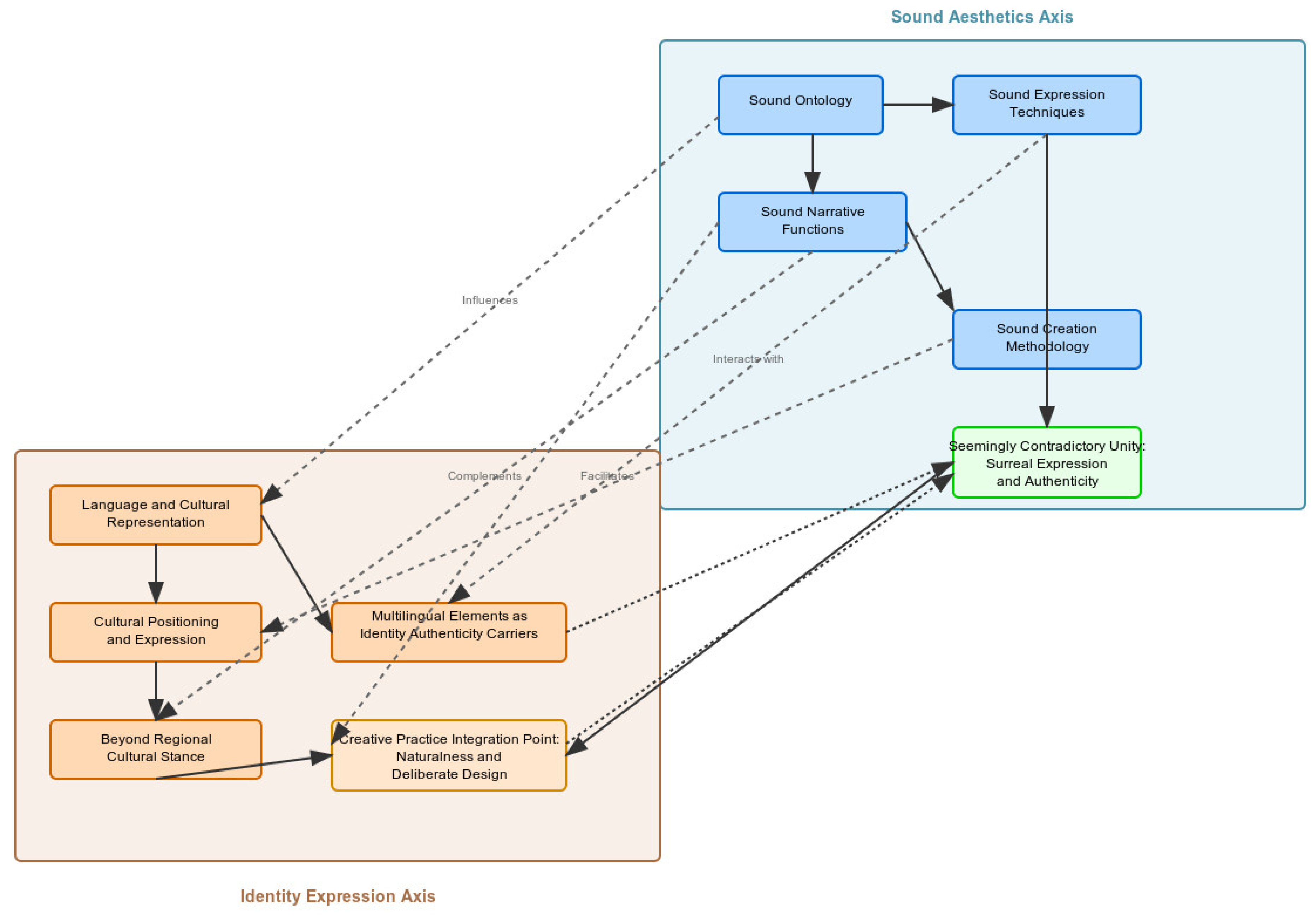

4.2. Axial Coding

4.3. Selective Coding

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Sound Aesthetics

5.2. Identity Expression

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Abd Muthalib, Hassan. 2007. The Little Cinema of Malaysia. Kinema: A Journal for Film and Audiovisual Media. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, Rick. 1992. Sound Theory, Sound Practice. London: Psychology Press, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Roland. 1977. Image, Music, Text: Essays. Roermond: Fontana. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgärtel, Tilman. 2012. Southeast Asian Independent Cinema: Essays, Documents, Interviews. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bhabha, Homi K. 1994. The Location of Culture. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1990. The Logic of Practice. Redwood City: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chion, Michel. 2016. Sound: An Acoulogical Treatise. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chion, Michel. 2019. Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eagleton, Terry. 2011. Literary Theory: An Introduction. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Edward T. 1973. The Silent Language. New York: Anchor. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Stuart, Laura Chrisman, and R. J. Patrick Williams. 1993. Cultural Identity and Diaspora. London: Harvester Wheatsheaf. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, Zawawi. 2012. Social Science and Knowledge in a Globalising World. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Social Science Association. [Google Scholar]

- Johan, Adil. 2018. Cosmopolitan Intimacies: Malay Film Music of the Independence Era. Singapore: NUS Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, Gaik Cheng. 2004. Contesting Diasporic Subjectivity: James Lee, Malaysian Independent Filmmaker. Asian Cinema 15: 169–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoo, Gaik Cheng. 2006. Reclaiming Adat: Contemporary Malaysian Film and Literature. Singapore: NUS Press. [Google Scholar]

- Khoo, Gaik Cheng. 2007. Just-Do-It-(Yourself): Independent filmmaking in Malaysia. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 8: 227–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvale, Steinar. 1994. Interviews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, James. 2025. Personal communication. March 29. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, Laura U. 2000. The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, Christian. 1981. The Imaginary Signifier: Psychoanalysis and the Cinema. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Murch, Walter. 1995. In the Blink of an Eye: A Perspective on Film Editing. West Hollywood: Silman-James Press. [Google Scholar]

- Naficy, Hamid. 2001. An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Filmmaking. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, R. Murray. 1993. The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Seidman, Irving. 2006. Interviewing as Qualitative Research: A Guide for Researchers in Education and the Social Sciences. New York: Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenschein, David. 2001. Sound Design. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, Anselm, and Juliet Corbin. 1998. Basics of Qualitative Research Techniques. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Trinh, Thi Minh Ha. 1991. When the Moon Waxes Red: Representation, Gender, and Cultural Politics. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Heide, William. 2002. Malaysian Cinema, Asian Film: Border Crossings and National Culture. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yusoff, Norman. 2013. Contemporary Malaysian Cinema: Genre, Gender and Temporality. Ph.D. thesis, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2123/9925 (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Zhang, Xuqing. 2013. James Lee: Malaysia New Waves Director. Contemporary Cinema, 156–160. [Google Scholar]

| A. Concepts Related to Sound Aesthetics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Concept | Source Question | Description | Typical Quote |

| R1 | Priority of Sound | Q2 | The director believes sound is more important than visual elements and is key to a film’s success. | “I think there is one thing that many people don’t understand about movies: the most important thing is the sound and the music; if there is no music and sound in a movie, it’s just a picture, it doesn’t look good, and sometimes that feeling doesn’t come out.” |

| R2 | Authenticity of Sound | Q2 | Sound is considered more authentic and emotionally impactful than visuals. | “What you see can be fake, but what you hear is different. So, what you see doesn’t mean it’s true.” |

| R3 | Collaborative Sound Design | Q2 | The director enjoys collaborating with professional sound designers for fresh creative perspectives. | “I think it’s better to work with people. In movies, I feel like something you and a different person seem to be succinct.” |

| R4 | Surreal Use of Ambient Sound | Q6 | Intentionally using or enhancing ambient sound to create a surreal atmosphere, rather than seeking realism. | “For example, like you said, the sound of insects. There aren’t that many insects at night in Malaysia, especially in Kuala Lumpur. I use the sound more often, inspired by Japanese author Haruki Murakami.” |

| R5 | Ambient Sound as Emotional Carrier | Q6 | Ambient sounds are used to express characters’ emotional states and inner worlds. | “In Call If You Need Me, after the character kills his friend, the cricket sounds are intensified to represent his emotional state.” |

| R6 | Audiovisual Contrast Art | Q5 | Deliberately designing contrasts between visual and auditory elements to convey deeper thematic messages. | “Sound is more important, and in Gerhana, the point was to express the idea that what you see isn’t real. Many people rely on hearing to process what I wanted to convey.” |

| R7 | Narrative Function of Sound | Q5 | Using sound as an important element in advancing the narrative, rather than as mere background. | “The sound from the TV in Gerhana was designed from the scriptwriting stage. The TV is the main focus, so it wasn’t something added in post-production.” |

| R8 | Sound Effects and Music Transition Techniques | Q8 | Using smooth transitions between in-film and out-of-film sounds to create cinematic language. | “The beauty of film is that sometimes what you hear in the film world, like a motorcycle bell, can suddenly transition from a sound effect to the soundtrack.” |

| R9 | Emotionally Contrasting Music Selection | Q7 | Choosing music that contrasts with the film’s overall atmosphere to highlight emotional release. | “I needed a sense of unrestrained freedom, which contrasted with the overall controlled, suppressed tone of the film.” |

| R10 | Atmosphere-Oriented Music Selection | Q7, Q8 | Selecting music based on its overall atmosphere and feel, rather than its lyrical content. | “I focus more on the overall feeling of the music, the style it presents.” |

| B. Concepts Related to Identity | ||||

| No. | Concept | Source Question | Description | Typical Quote |

| R11 | Natural Multilingual Transition | Q3 | The natural presentation of multilingual switching in Malaysia reflects local language habits. | “If I speak Mandarin with you, although it’s not good, later on I might use Cantonese, and then there’s a possibility that I speak English with my Malay friends, because some Malays speak English.” |

| R12 | Language as an Element of Authenticity | Q3, Q4 | Using authentic language environments as part of the film’s realism, rather than arranging them artificially. | “Originally, why did I make a distinction between Mandarin and Cantonese? The problem is that the old actor in the second part of the movie doesn’t speak Mandarin, he speaks Cantonese.” |

| R13 | Showcase of Linguistic Diversity | Q4 | Displaying Malaysia’s multiculturalism through language diversity for international audiences. | “Once I went to that film festival, many people wondered why there were Malay plays, Indian plays, Chinese plays, but all came from Malaysia.” |

| R14 | Language as Regional Identity | Q4 | The uniqueness of Malaysian Chinese is a marker that differentiates them from other Chinese communities. | “Our Chinese language is not very standard—it’s not like Singapore’s, nor Taiwan’s, and not from anywhere else either.” |

| R15 | Non-Identity-Oriented Creation | Q1 | The director’s creative inspiration does not stem from personal background or cultural identity. | “My upbringing didn’t influence my work because I lived in Ipoh quite a lot during that time, nothing special, so I rarely put my own life experiences in my movies.” |

| R16 | Narrative Pursuit Beyond Regionality | Q1 | Tendency to explore story types and themes not present in Malaysian society. | “I think, if I have a chance, I would like to make a story about Hong Kong or Korea or something like that, not because I want to make a movie about their culture, because I think, sometimes they have stories that we don’t have, we can’t have that kind of story because society doesn’t have that kind of thing.” |

| R17 | Preference for Independent Music | Q7, Q8 | A preference for using local independent music, due to practicality and an appreciation for its authenticity. | “The first reason we often use local independent bands is that they are easier to negotiate with.” |

| R18 | Unintentional Cultural Choices | Q8 | Music is selected based on scene requirements, rather than deliberately choosing music from specific languages or cultural backgrounds. | “There isn’t much local independent music available, and although there is plenty of Malay music, their style and themes don’t always align with my films. But I’m not against using Malay songs in Chinese-language films if it fits the scene.” |

| A. Sound Aesthetics Axis | ||

|---|---|---|

| Theme | Code | Description |

| Ontology of Sound | Priority of Sound | Sound is regarded as more important and more authentic than visual elements. |

| Authenticity of Sound | Sound is seen as a more emotional and truthful medium. | |

| Sound Expression Techniques | Surreal Sound Aesthetics | Deliberate manipulation of ambient sound to create a surreal atmosphere. |

| Ambient Sound as an Emotional Carrier | Ambient sound is used to express the character’s emotional state. | |

| Audiovisual Contrast Art | Designing contrasts between visual and auditory elements to convey deeper messages. | |

| Narrative Function of Sound | Narrative Progression through Sound | Sound serves as a key element in driving the story forward. |

| Emotional Contrast Music | Music is selected to contrast the overall tone and emphasize emotional shifts. | |

| Sound and Music Transition | Using smooth transitions from diegetic to non-diegetic sound to create cinematic language. | |

| Sound Creation Methodology | Collaborative Sound Design | Working with professionals to gain fresh creative perspectives. |

| Atmosphere-Oriented Music Selection | Music is chosen based on the overall emotional atmosphere rather than lyrics. | |

| B. Identity Expression Axis | ||

| Theme | Code | Description |

| Language and Cultural Representation | Natural Multilingual Transition | Reflecting the natural switching of languages among Malaysians in different contexts. |

| Language as an Element of Authenticity | Using authentic language environments to enhance the realism of the film. | |

| Display of Linguistic Diversity | Showcasing Malaysia’s multiculturalism through linguistic diversity for international audiences. | |

| Language as Regional Marker | Malaysian Chinese as a cultural marker differentiating them from other Chinese groups. | |

| Cultural Positioning and Expression | Non-Identity-Oriented Creation | Creative inspiration does not directly stem from personal cultural identity. |

| Pursuit of Narrative Beyond Regionality | Preferring to explore stories beyond Malaysian local realities. | |

| Preference for Independent Culture | A preference for independent and non-mainstream cultural elements. | |

| Unintentional Cultural Choices | Music and cultural elements are chosen based on creative needs, not for the sake of emphasizing specific cultural backgrounds. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, X.; Suboh, R.b. Beyond Vision: The Aesthetics of Sound and Expression of Cultural Identity by Independent Malaysian Chinese Director James Lee. Humanities 2025, 14, 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/h14080170

Jiang X, Suboh Rb. Beyond Vision: The Aesthetics of Sound and Expression of Cultural Identity by Independent Malaysian Chinese Director James Lee. Humanities. 2025; 14(8):170. https://doi.org/10.3390/h14080170

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Xingyao, and Rosdeen bin Suboh. 2025. "Beyond Vision: The Aesthetics of Sound and Expression of Cultural Identity by Independent Malaysian Chinese Director James Lee" Humanities 14, no. 8: 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/h14080170

APA StyleJiang, X., & Suboh, R. b. (2025). Beyond Vision: The Aesthetics of Sound and Expression of Cultural Identity by Independent Malaysian Chinese Director James Lee. Humanities, 14(8), 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/h14080170