The elaborate subtitle,

Outtakes and Scores from an Archaeology and Pop-Up Opera of the Corporate Dump, suggests the multiple forms of expression and documentation Jennifer Scappettone employs in her 2016 work of ecopoetics titled

The Republic of Exit 43. The book developed from her investigations into two specific manifestations of the global “corporate dump” located right near where she grew up: the Syosset Landfill, an “ex-copper mill and free-for all landfill” (

Scappettone 2016b, p. 15) in the Town of Oyster Bay, New York that was used from 1933 to 1975, later designated a Superfund site, and the Fresh Kills Landfill, where “150 million volatile tons of solid waste” were dumped until the 2200-acre Staten Island facility closed in 2001. That subtitle positions the poet as also filmmaker, musical composer, and archeologist, while a look at the actual volume reveals the additional importance of her production as visual artist. The volume contains four “POPs-Up Interlude[s],” each presenting seven or eight pages of colorful collages made by Scappettone from cut-up found text, book illustrations, and photographic images. (POP is the acronym for Persistent Organic Pollutants, a category that includes organochloride pesticides such as DDT along with PCBs, dioxins, and other industrial chemicals.) Additional visual materials in the volume include photographs documenting the landfills either in the past or in the process of recent remediation, as well as more than a dozen photos recording Scappettone’s collaborative installations and performances where text-covered garbage excavated from Fresh Kills and solicited from performer and audience garbage bins was strung up over the site or on a set of large “looms.”

Scappettone’s book is the most complex and multi-layered of those I discuss in this essay that explores the recent interest in generating eco-poetry or environmentally engaged works written under the capacious sign of poetry that hybridize artistic genres, incorporating visual elements created by the poet

1 and sometimes musical elements or scores as key modes of meaning-making in the text. Of course, poetry has long relied on visual and musical elements for its communicative power. In the anglophone traditions, at least since the early-17th-century writing of George Herbert, page space has been a valued expressive resource, and for far longer poetry and music—as is evident in the etymological roots of lyric in the Greek word for lyre—have been intimately bound. The collage practices of such modernists as William Carlos Williams and Ezra Pound, extended by Charles Olson, Susan Howe, and others, provide precedent for including in longer poetic forms images, photographs, and portions of found documents. While drawing upon that rich collage tradition, numerous contemporary poets are doing something distinctive with visual materials. Employing strategies beyond (if sometimes including) concrete poetics, illustration, or photo-documentation and beyond the musicality of poetic language or the aural techniques of sound poetry, they are drawing so centrally on the resources of the visual arts and of musical scoring that their poems become inter-arts hybrids

2.

The interdisciplinary character of ecopoetics—its frequent integration of knowledge associated with the natural sciences—along with its attention to material conditions of planetary life particularly invite the use of visual or audio technologies as modes of representation or documentation. While serving ecopoetry’s aim of accurately reflecting environmental conditions or processes, these multi-modal elements can also support current investigations within the environmental humanities into multispecies connectivity and into the sensory and communicative worlds of plants and non-human animals

3. They provide prompts toward multisensory attention that may shift readers’ perceptions of the more-than-human world.

This essay will present four exemplary texts to explore some of the ways in which, by integrating into volumes of poetry visual and musical art usually of their own making, poets are expanding the environmental imagination and enhancing their environmental messaging. The visual and musical elements in these multi-modal works, I argue, offer fresh perceptual lenses that help break down cognitive habits bolstering separations of Western human from more-than-human realms or dampening awareness of social and cultural norms that encourage environmental degradation and violations of environmental justice. In particular, the visual and/or musical elements (1) provide alternatives to the conventions of the individual, bounded lyric speaker, opening instead to communal and sometimes multi-species voices, histories, and understandings of embodiment; (2) enhance understanding of the scalar challenges of our time, whether that means providing better access to more ecocentric, less anthropocentric, perspectives and understandings or fostering recognition of the vastness and daunting complexity of current environmental crises, entangled as they are in capitalist, colonialist, and patriarchal social structures; and (3) require additional levels of involvement and participation by the readers, who must activate multiple senses and discern for themselves the relations among the text’s multiple media. Taking on those interpretive responsibilities encourages more multifaceted environmental awareness. With these claims in mind, let us return to The Republic of Exit 43.

Ten years in the making and depending on vast amounts of research,

The Republic of Exit 43 is an astonishingly ambitious project. To produce it, Scappettone had to piece together the histories of the two landfills and the legal struggles involving townships, corporations, and the EPA surrounding their remediation, even as the documents she needed were nefariously disappearing. While her mother was undergoing chemo and amid the “unparallel afflictions of an increasing toll of friends,” she investigated health impacts of dumped toxins and the cancer clusters in the area. On even the simplest levels of the amount of trash and the range of toxins the two local landfills contained (or, failing to contain, leached), the immensity of scale involved was difficult to convey. Moreover, this archeology of the dump “found itself addressing a multinational sprawl of diversified environmental mishaps along the way” (

Scappettone 2016b, p. 15). The “Chorus Fosse” section, for instance, focuses on the record-breaking Deepwater Horizon oil spill. It also mentions the underground coal mine disaster in Montcoal, West Virginia; the lead poisoning of children in La Oroya, Peru due to heavy-metal mining; and the poisoning of Agbogbloshie, in Accra, Ghana by exported Western e-waste. A need to give sensory and intellectual immediacy to the enormity and the complex layering—geological, temporal, legal, and figurative—of her subject pushed Scappettone toward multi-modal strategies.

Here is a passage where the poet explains how her performances and installations that displayed text-covered trash pulled from the gargantuan dump and from ongoing waste streams, partially recorded in the photos in

The Republic of Exit 43, provided a way to render the enormity of its contents “articulate”:

Fresh Kills: a landscape yielded from half a century of ‘mounding,’ or the dumping of up to 29,000 tons of trash per day, for decades the largest of its kind in the world. Massiveness abstracted from its contents isn’t articulate; and a monument to consumption, on land still off limits, has to exist in time, in transit. This is how we came by fits and starts to salvage garbage by threading the dregs of post-consumer language for a chorus: 150 million tons of trash, as sheer lumpen mass, balks eloquence.

In the book, each photo of these threaded dregs accompanies one of fourteen texts composed primarily from words—often advertising text— found on salvaged trash, some of them visible in the photos. By their very existence the verbal mashups demonstrate how consumerism, especially in a culture of planned obsolescence, generates ever-accumulating waste. Collectively, the visual/verbal ensembles, as if each pairing were a line of verse, form Scappettone’s “Post-Consumer Confessional Sonnet: A Quavering Stanza in Fourteen Displacements.” Here’s a sample from one of the textual portions:

| With herbs & spices just for you—healthy living, well-being and fitness push our buttons—Safety never |

| felt so good—feel better—play through sensible sound solutions song—The only home-use |

| device on the market—Nature’s path 440 sound barrier—it does so much so well. . . Presenting |

| the blue cash from American Express |

| In tears. Related over the tax-smart options to extend healthy water activities—roasted seaweed summer |

| sounds—introducing kyrobach—dipped suddenly down, quick cook keep refrigerated—Our |

| bakers come in early—Pacifica |

| Ritual community services CA SEFS compliant hint: Fireplace $1.50 off-- a pack of black menthol words |

| might settle after all, scorched earth food for life crisps made in LA—success stories and rave |

| reviews—Over 5 million sold! 888-654-FIRE (Scappettone 2016b, p. 125) |

“THINGS JUST GOT REAL,” announces one of the displacements; indeed, the “sonnet”’s hybrid technique calls upon multiple senses to register the nearly ungraspable material reality of our always expanding, seemingly indestructible corporate-driven remains. It is as a combinatory form of sense-making that the text and photos most effectively bring into view the overwhelming scale of our accumulated waste as well as the vastness of the capitalist forces behind it.

4The POP’s up collages in

Exit 43 enhance other dimensionalities, emphasizing the poet’s archeological exposure of legal, historical, and literal subterranean layers of the corporate dump, for which Alice’s disorienting plunge down the rabbit hole provides a recurrent figure. These eye-catching collages position horizontal lines of cut-out text of varied fonts and sources across background images that are usually landscape photos, so that reading from top to bottom involves a descent from sky to sea, or from sky though the built landscape to plants and ground and sometimes beyond to subterranean strata. Their construction suggests an over-writing of the traditional pastoral, not an excision but a penetrating analysis and a radical modification. As Scappettone explains in the book’s prefatory “Underture,” these “pop-up choruses” “sample the syntax and nonsense logics of Lewis Carroll to graft / last-ditch pastorals of poetasters, from Virgil to Victorians, onto the quarrels of buried corpuses, CEOs, the EPA, estimated pupils / and halflives of chemical substances, tracing the pathways of a malice in Underland that is incompletely virtual, / for which the responsibility has been rendered abstruse” (

Scappettone 2016b, p. 16). Responsibility is not just obscured deliberately by the corporations immediately involved, but, as is evident in the longer history of Western relations to nature, by our culture more broadly; that culture is represented here by fragments unearthed from literary history.

Elaborating the particular resonances of the quotations from Matthew Arnold’s poems alone—snippets from “Strayed Reveller,” “Dover Beach,” “The Forsaken Merman,” “Stanzas from the Grande Chartreuse,” “Thyris,” “Resignation,” and perhaps others—would be an illuminating interpretive project

5. But for the purposes of this essay, it is sufficient to note that the many phrases from works composed in the Victorian era reflect the longings, losses, and self-deceptions of that period of sweeping industrialization and rapid environmental pollution—the period many regard as the beginning of the Anthropocene. Often suggesting pastoral nostalgia, these bits of 19th-century literature collide with fragments from legal documents generated in battles over responsibility for environmental poisoning near the Syosset or Fresh Kills landfills or from a medical study of the Long Island breast cancer cluster. In context, the literary selections often acquire ominous overtones. “[G]rowing and growing, and very soon” (

Scappettone 2016b, p. 36), for instance, which in its original context describes Alice’s bodily transformation after she imbibes an unidentified chemical potion, here suggests the horrifying growth of consumer society’s accumulating waste and the growth of toxin-related tumors in nearby residents. (Human and non-human beings living near the landfills were heavily exposed to POPs, which can be transported by wind and water; these harmful chemicals biomagnify in the food chain and bioaccumulate in the body, and most are likely carcinogens.) A background photo and quotations from another Victorian era text, Jacob Riis’s

How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York, point to the history of Scappettone’s family and the larger immigrant history of which it is part. Her great-grandfather and grandfather who immigrated from Italy and sold salvaged items from a pushcart would have been among those whom Riis, in a bit of text Scappettone includes, disparagingly identified as “swarms of Italians who hung about the dumps.” As Kate Lewis Hood observes in her excellent essay, “In the ‘Fissures of Infrastructure’: Poetry and Toxicity in ‘Garbage Arcadia,’” incorporating his language “point[s] to the ways that waste and toxicity get stuck to certain bodies along class and racial lines” (

Hood 2021). These two examples can suggest how the visually compelling POPs-up collages compress into a few pages sweeping amounts of often occluded intellectual, social, and environmental history, enhancing the scalar resources of the book.

Scappettone has been explicit about her belief that the traditional bounded lyric speaker is inadequate to our period of environmental catastrophe. In a short essay titled “I owe v. I/O” she declares, “the poetic fallacy of a coherent lyric person must…continue to be pierced in favor of industrious focus on the forces, the substances, the spills that breach and bind us” (

Scappettone 2016a)

6. The visual/verbal hybrids of both the “Post-Consumer Confessional Sonnet” and the “POPs-up Interludes” reflect just such an industrious focus, and both rely on an alternative to the singular lyric speaker that Scappettone conceptualizes as a chorus.

7 Her thinking about the chorus, as explained within

The Republic of Exit 43, is shaped by etymology that links the chorus to “the polis’s threshing floor”— “a place where thrashing and coaxing the harvest for its seed…and dancing” occur, where “the seduction of fertility—skids, sensationally, into the genre of tragedy” (

Scappettone 2016b, p. 49). The chorus functions, then, to expose a fertile kernel or essential truth, though doing so may require violent “thrashing” and may reveal tragedy. A civic and religious space, the “choros” is the place in the city for the “many voices” of “the policed populace at large.” These voices do not speak for the powerful; instead, “the poetic feet of the chorus evolve a contrapuntal relation to those of the looser marionettes of the deities onstage, like the gossip expressing darkling secrets and anxieties the actors cannot” (

Scappettone 2016b, p. 103). Scappettone’s additional descriptions suggest the chorus is both the Dionysian “zone of emoting” and a “site of penetrability.”

That notion of penetrability is important in the context of “the spills that breach and bind us,” for Scappettone’s adaptations of the Greek chorus reflect an ethically crucial re-conception of communal voice that is capable of registering our globally trans-corporeal entanglements, including the ease with which human bodies are penetrated by environmental toxins. Her choral technique enacts what I call trans-vocality, following from Stacy Alaimo’s notion of the “trans-corporeal,” which emphasizes the “material interconnections of human corporeality with the more-than-human worlds.” “By emphasizing the movement across bodies,” Alaimo observes in

Bodily Natures,

trans-corporeality reveals the interchanges and interconnections between various bodily natures. But by underscoring that trans indicates movement across different sites, trans-corporeality also opens up a mobile space that acknowledges the often unpredictable and unwanted actions of human bodies, nonhuman creatures, ecological systems, chemical agents, and other actors.

Scappettone’s parenthetic list of the members of her POPs-UP CHORUS is similarly inclusive. It reads: “EPA, H

20, CEOs, VOCs, Pb, PRPs, organics, arsenic, MAY, ESQ., ETC.” (

Scappettone 2016b, p. 17). (VOCs is the acronym for Volatile Organic Compounds and PRPs for Potentially Responsible Parties, an abbreviation used by the Environmental Protection Agency [EPA] in Superfund clean-up projects.) The trans-vocal collages, then, give voice to government entities, lawyers, corporate leaders and other parties potentially responsible for or attempting to control toxic pollution, as well as to the pollutants themselves, such as lead, arsenic and carcinogenic volatile organic compounds used in manufacture, and to water—necessary for life yet also a vehicle for trans-corporeal toxin transmission. “Organics” could designate agricultural products grown without potentially harmful chemicals, though it also could mean any organisms containing carbon-based compounds—that is, all forms of life. Such a chorus may be infinitely expansive. Like the POPs-up collages, the “Post-Consumer Confessional Sonnet” is also a verbal-visual choral piece, “a woven chorus score” (

Scappettone 2016b, p. 108); its voices are those of corporate advertising but also of the public’s nostalgic longings for pastoral purity and health. My term

trans-vocality acknowledges the importance of multiple actors’ voices in

The Republic of Exit 43 and points to the thoroughness of those actors’ often unwanted material intertwining; it registers that chemicals in the environment leach into and transform human and non-human animal bodies. Interconnectivity has a dark side in our chemically polluted world.

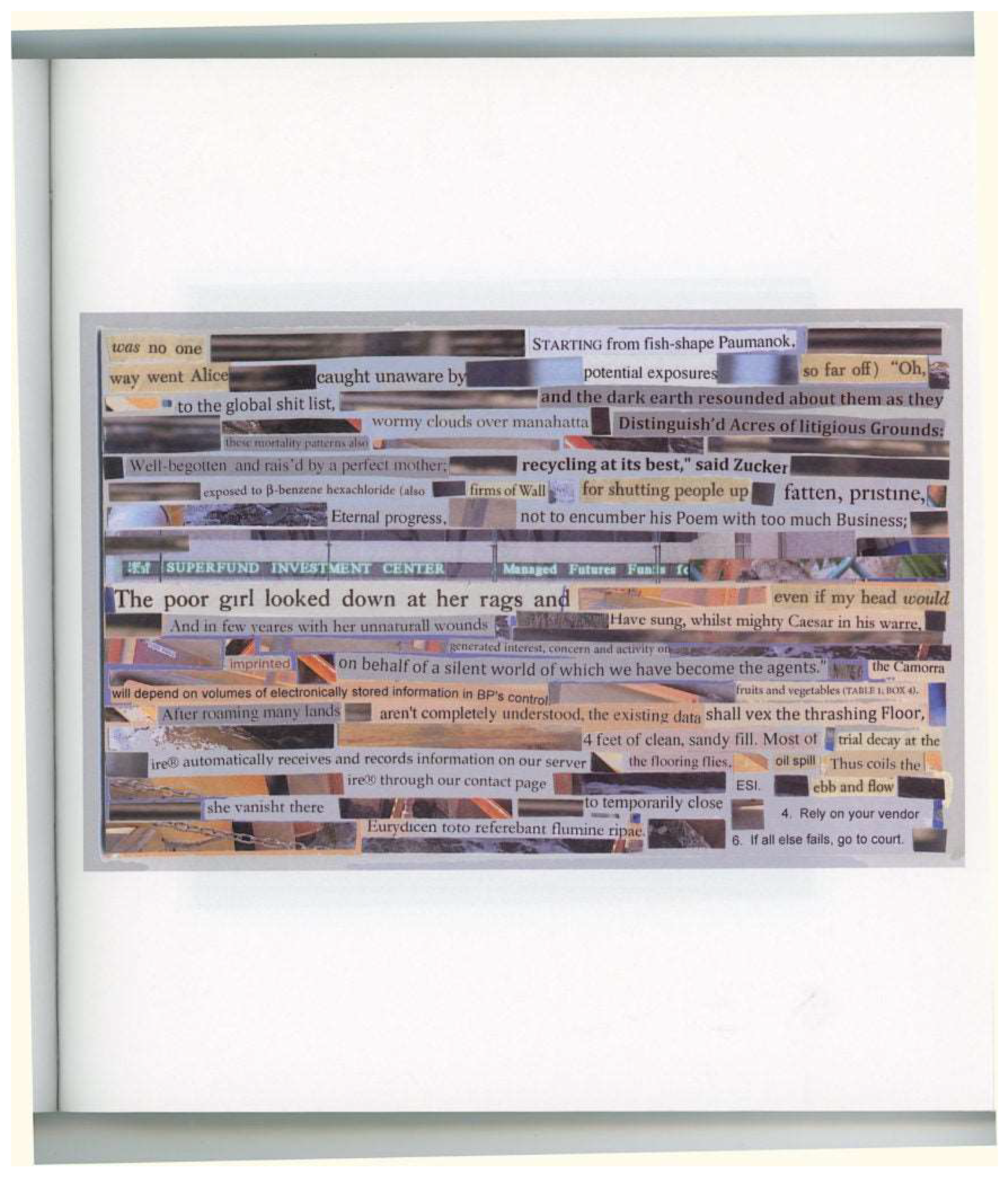

The text section “A Chorus Fosse”—in which the identified “players” Alice, Orfeu, and Virgil employ multiple voices, including echoes of the musical “A Chorus Line” and a snippet from Arnold’s “The Strayed Reveller,”—demonstrates that visual elements are not necessary when Scappettone stages choral voicing. However, as

Figure 1 demonstrates, the collaging of varied texts in the “pop-up choruses” (

Scappettone 2016b, p. 16) and their juxtaposition with photographed landscape elements produces especially intense registration of the inseparability of human and “environment” and of the mobile, often invisible communal poisoning that Scappettone is exposing. In the collage displayed below (

Figure 1), phrases evidently from multiple sources—“potential exposures,” “mortality patterns,” “exposed to B-benzene hexachloride,” “unnatural wounds,” “oil spill,” and even perhaps “wormy clouds over manahatta”—suggest health threats to everyone in the polis. The opening phrase alone, “

was no one,” might point to the lack of separation of bodies, their permeable boundaries rendering no

one apart. Quotations from Whitman, Hesiod, Virgil, Levi-Strauss, Lewis Carroll, technical reports, and more, because jammed together in their different colors and fonts, render inescapable the collective character of this cacophony.

The background images occupy little space in this collage, but the glimpses we get of metal banisters, chains, and chain-link fencing suggest the context of the built environment, industrialization, and attempted barriers, while the superimposed language indicates how flawed such superficial attempts to separate the public from pollution have proven to be.

For Scappettone, a juxtapositional multi-vocal practice is essential to making meaning from the detritus of the “corporate dump.” Speaking of the performances/installations with inscribed trash from Fresh Kills that were produced during the capping of the landfill to transform its poisonous wasteland into a “garbage arcadia,” she explains,

Out of language manufactured utterly within closed circuits of consumption, how was my insubordinate message to emerge? Branding had to be irrupted by idioms other to it: those of collective observation, nursery rhymes and lullabies inspired by the hills innocent of building, transsense logics, technology news, Bartleby’s dead-wall reveries, and the human mic echoes filling the rerouted streets and newly public squares, printed in emergency colors.

Other eco-poets may not use trans-vocal choruses as their alternatives to the bounded lyric speaker, but this strategy powerfully gives communal voice to the slow (and sometimes not slow) violence of the global chemical disaster that is Scappettone’s environmental focus.

***

None of my other exemplary texts are as focused on environmental crisis as Scappettone’s. Indeed, JJJJJerome Ellis’s Aster of Ceremonies: Poems, published in Milkweed’s Multiverse literary series that “emerges primarily from the practices and creativity of neurodivergent, autistic, neuroqueer, mad, nonspeaking, and disabled cultures,” is most readily categorized within disability studies and also black studies. Its author, who uses the pronoun they, is a “proud stutterer” of Jamaican and Grenadian heritage, and much of the book considers the stutter and its surprising resources. Yet Aster of Ceremonies also reflects a powerful interest in environmental history as it attends to the plant species that would have aided the survival of the “run-away” enslaved. Moreover, it calls ceremonially for a current relation to the plants with which the enslaved “ha[d] relationships”—and by extension, to all plants around us—of reverent respect, gratitude, and recognized kinship. The book’s commitments to environmental history and knowledgeable attachments to plant life justify its consideration as a work of ecopoetics.

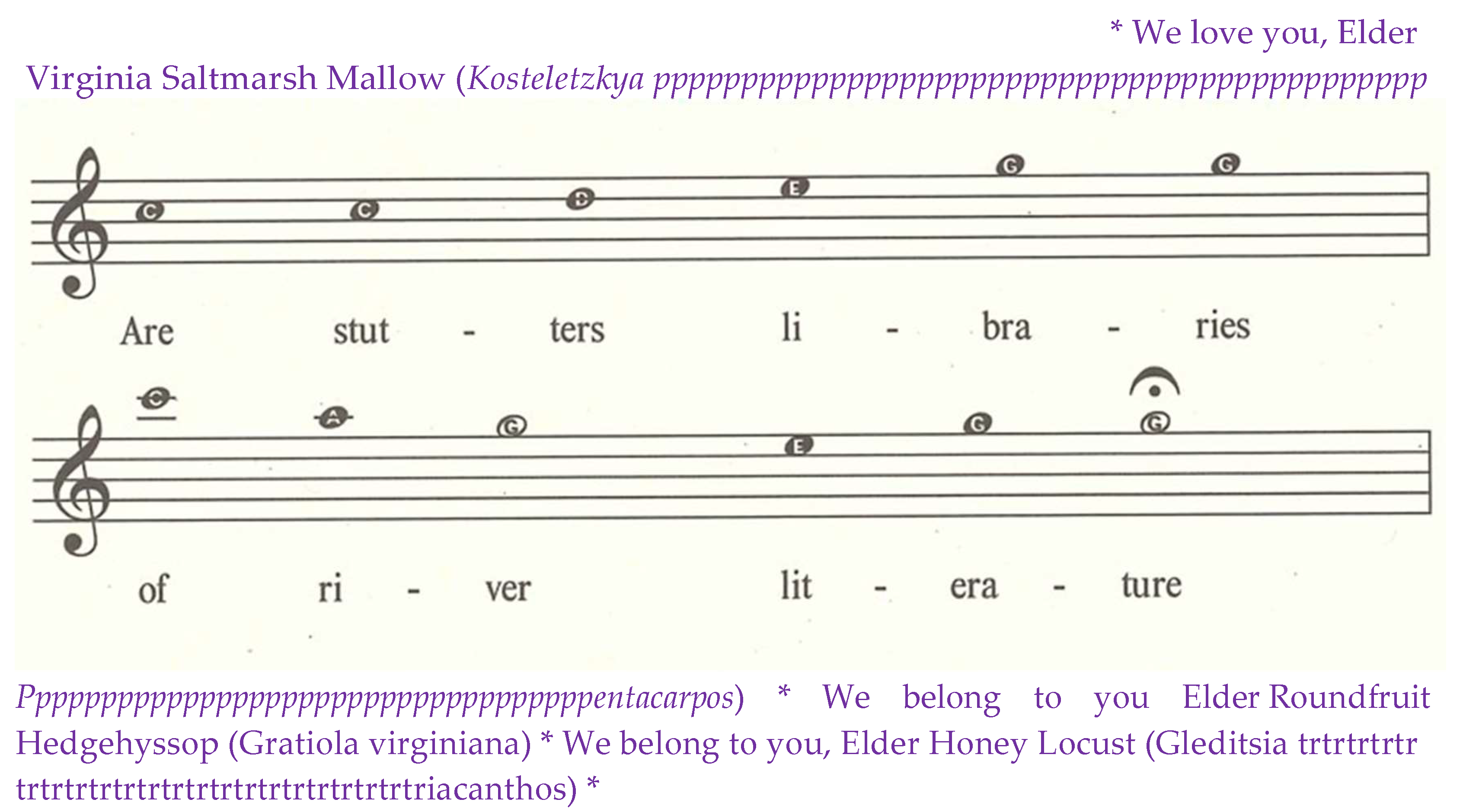

The honorific recognition due plants is visually marked by initial capitals and by use of magenta ink whenever a plant is named. This use of color is surprisingly effective at making one notice plants in the text and beyond it. The entire “Benediction, Movement 2 (Octave),” 33 pages of solid single-spaced text addressed to literally hundreds of individual plant species that live in and around Charleston and interrupted only for some short musical passages, is printed in that bright ink. These plants are addressed as Elders (and the enslaved as Ancestors), and the book is dedicated to one: “FOR SWAMP HONEYSUCKLE.” It also contains three full-page botanical drawings—of yarrow in bloom, the cone of the longleaf pine, and chokeberry in bloom—again in magenta ink.

While the choral and operatic sections of

The Republic of Exit 43 have no musical scores,

Aster of Ceremonies does incorporate musical compositions displayed on treble clef staffs and accompanied by words to be sung. One can hear the author performing the music in the audio version of the book, but Ellis’s hope is evidently that readers will also become its singers. The simple music’s notation is clearly explained in the text; readers are invited to transpose to any key and employ any rhythm they desire, assured that “The way I sing this music on the audiobook is just one interpretation of the rhythm” (

Ellis 2023, p. 32).

Music takes its important place in the book as a way to “hear slavery’s stutter (or slaveries’ stutters)” (

Ellis 2023, p. 6). The discovery that launched the book was a sentence from a scholarly article: “Some statistics indicate a high incidence of stuttering among slaves.” Reading this led Ellis, a life-long stutterer, to uncover an archive of 18th- and 19th-century newspaper advertisements placed by enslavers seeking people they enslaved who “ran away” and eventually to focus on those ads that identified individuals who “stuttered, stammered, or spoke with speech impediments” (

Ellis 2023, p. 3). Following the example of M. NourbeSe Philip, who wrote

Zong! by “restricting herself to the words (and anagrams of those words) of an eighteenth century legal decision concerning the massacre of Africans aboard the slave ship

Zong” (

Ellis 2023, p. 3), Ellis used these ads as sources for his text, generating from within this “archive of Black dysfluency” (

Ellis 2023, p. 29) statements about stuttering that opened for him more positive understandings of the stutter (e.g.,

“stutters are vessels” (

Ellis 2023, p. 3)). “Here,” Ellis writes, “as so often, I have used music to try to hear. The musical notation in this book is only one layer of a bigger music, a long song I call on constantly to protect and guide me, and to undo my learning.” A few lines later they observe, “I’ve tried to use my senses to attend to Plants, to music, to the Ancestors, and to the Stutter. I’ve tried to use this book as a musical instrument of unknowing” (

Ellis 2023, p. 6). Engaging in unknowing becomes one of the challenges this multi-modal text poses for its readers, encouraging unexpected appreciations of what might be discovered within the silences of a glottal-block stutter or by turning fresh attention to common plants. Ellis’s work with the source texts becomes a model of transformative environmental imagination, as the title’s

Aster comes from (the slave-owning) Master, while “GRO,” as in “the

Rose of the stutter / shall GRO / through the fence / of prose” (

Ellis 2023, p. 67), derives from the ads’ objectified NEGRO.

Like Scappettone, Ellis invokes choral voicing, a further way of encouraging an unusually active readership and employing a more-than-individual voice. The title page’s description of the volume concludes, “Some Pages of a Reverence Book Awaiting to be Gathered and Sung with other Quires,” and, while a footnote identifies quires as “groups of pages gathered to form a bound book,” the homonym “choirs” rings loudly. All three movements of the volume’s lengthy “Benediction” are introduced with the words, “the choir chants:”. This use of choir connects to Christian spiritual practice rather than the chorus of Greek tragedy, but both serve to shift from an individual voice to a communal one. In the act of reading, the reader becomes a member of the choir.

A shared voice may have particular emotional resonance for one whose speech has set them painfully apart. Ellis elaborates on the burden experienced by the stutterer whenever they must say their own name. When younger, they had dreaded these occasions; “For most of my life I named my stutter Burden, Curse, Disorder, Issue, Problem” (

Ellis 2023, p. 3). Now Ellis thinks of those occasions as initiating a ritualized “Liturgy of the Name” (

Ellis 2023, p. 25):

Whenever I approach a moment when I may need to introduce myself, a liturgy begins. I’m in line at Shake Shack and I know the cashier will ask for my name when I have ordered my hamburger. The liturgy begins in line, my spirit already inhaling the incense of anticipation. How do I prepare? A vector of attention and tension stretched out within me like a taught violin string ready to vibrate.

They can now embrace the moment when the stutter will block their self-identification as an opportunity for expansion beyond a bounded self:

When the door of my vocal cords closes, another opens. And through that open door I escape into a region I do not know what to call but which is vaster than the space of my body. You could say: my name is the door to my being, and in that interval when I’m stuttering the door is left wide open and my being rushes out. What rushes in?

No single answer to that question emerges. At one point Ellis wonders whether the stutter might be one of the mother tongues spoken by “my African ancestors” passing through their body (p. 31). Elsewhere, lines whose italics signal their origins in the words of the run-away slave ads suggest that rather than isolating the speaker, the stutter may bring the stutterer into community: “

is the stutter an arbour / of maybe // the arbour of maybe made I into our” (

Ellis 2023, pp. 38–39). Later, “

with a speech Impediment, the Instant can flower” (p. 49). Having come to regard the stutter as “a seeking after the only thing that will quench me: sound, thunder, god” (

Ellis 2023, p. 25), Ellis now appreciates this supposed handicap as something that may allow a person to be filled with more than themselves—and, I would note, to escape the bounds of the lyric I. While trans-vocality in Scappettone’s work often registers shared vulnerability to environmental poisoning, Ellis’s version of the intertwining of multiple voices, ironically available through the vocal interruption of the stutter, is thoroughly positive.

In other aspects of its ceremonial character, the volume further invites group participation. “Benediction, Movement 1,” for instance, repeats for 15 slaves a blessing (one acknowledging that slaves, too, may not have been comfortably connected to the name they had to go by) spoken in a collective first-person plural:

What name did Ancestor Lucy call herself? We do not know. We honor her relationship to her own name.

According to the advertisement, she “ran way” on March 19, 1797, on or near land and water traditionally stewarded by, among others, the Sewee people—also known as Charleston, South Carolina.

We honor the holiness of her speech, and of her whole being.

We thank all the Plant Elders for creating the oxygen she breathed. (

Ellis 2023, p. 37)

Recurrences give different names, dates, and tribal locations, while the collective final lines remain unchanged as ritualized non-individual speech.

The final lines of that repeated pattern, one devoted to a single enslaved person and the other to the entire realm of plants over billions of years,

8 indicate the scalar challenges highlighted by this work. For

Aster of Ceremonies brings together two archives, materially of sharply different scales yet both reflecting realms of stunningly large scale. As Ellis notes, the escaped slave ads are “typically brief…and brutally to-the-point.” Yet his fifteen examples represent an estimated 200,000 such ads that were published in American newspapers before the end of the Civil War. Ellis’s source for plant knowledge is

The Flora of North America, a detailed scientific guide already more than a dozen volumes long and projected to run to thirty volumes due to the huge number of plants on this continent. Working from that guide, Ellis

began making lists of the Plants that grow in the areas where the Ancestors “ran away.” Some of the lists focused on Plants that would have been in flower at the time the Ancestor is reported to have “run away.” Others [as becomes evident in “Movement 1”] focused on communities of Plants that have evolved to grow together in certain environments like swamps or dunes. Making these lists helped me feel protected as I engaged with this hard material. And it felt like a way of expressing gratitude and respect to the Ancestors, as well as to the Plants themselves.”

The astonishing number of plants to which we owe reverence, love, attention, and so forth is suggested by the 30-plus pages of “Benediction, Movement 2 (Octave),” in which Ellis again employs a first-person plural speaker to honor literally hundreds of named species. Each address, moreover, incorporates the stutter, so that the reader, while encountering the vastness of this realm of non-human kin, becomes as much a stutterer as the author, experiencing whatever might emerge from the stutter’s suspension of enunciation.

Figure 2 provides a small sample from the dense single-spaced pages that includes some of the book’s musical notation:

This Movement is one manifestation of what Ellis in the following section explains is an alternative to their earlier failed attempts to master the stutter which was then a source of “shame, anger, and despair.” Instead, Ellis asked “What might it mean to

Aster my stutter?” (

Ellis 2023, p. 123), not trying to tame the stutter but allowing it to “

gro wild in my throat” (

Ellis 2023, p. 124). Ellis finds a solution to a personal problem in a transformed relation to plants that in turn transforms their relation to their “disability.”

Implicitly, the transformation Ellis seeks is far more than an individual one. For just at this point Ellis recounts two autobiographical incidents reflecting the pervasive microaggressions and threats experienced by black Americans as slavery’s legacy in our racist society. Only then does Ellis return to the subject of astering the stutter—of what it might mean to treat the stutter, directly addressed as You, as an Elder that, like the “marvelously plural” composite asters, has so much to teach. Importantly, the processes of unknowing and learning that Ellis has been modeling, which involve profoundly altered relations to more-than-human lives, are also potential modes of social resistance. Two of the title page’s footnoted quotations seem especially relevant: “I’ve been concerned for a long time with Black performance as the resistance events of persons denied the capacity to claim normative personhood” and “our nonhuman kin are sometimes the family members with the greatest fugitive stance for resistance.”

***

Danielle Vogel’s Edges & Fray: On Language, Presence, and (Invisible) Animal Architectures is another inter-arts hybrid that models and invites altered attention to more-than-human beings. The book investigates the processes of writing and reading largely by considering how various bird species—and occasionally other nest-building creatures such as organ-pipe wasps—construct their nests. Structured, in Vogel’s words, as “a series of filaments,” the volume is composed of fragmented text arranged in varying forms that highlight the airy space of the page, interwoven with 19 pages containing Vogel’s selectively focused, close-up photos of portions of bird nests. These extraordinary photos reveal in astonishing detail the nest materials and their interweaving, while the images’ earthy palette of browns, ochres, and rusts gives the volume a harmonious warmth. Like the text in its varied formal arrangements, the photos appear in varying design: Most often, two or three photos of different or identical sizes appear on a page, but a single image may be set off by the generous space of the page, while four or six may occupy facing pages. Usually, the images are surrounded by white margins, but in one set of four images arranged in a line across a page-spread, the outer photos run all the way to the edges. Once, a single photo appears cut into vertical strips of varying height separated by equal units of white space.

These photographs are far more than aesthetically enhancing illustrations. They contribute importantly to the environmental messages of this multi-modal hybrid. The plain backgrounds make clear the photos are not taken in the wild. Vogel took them at several museum collections, and notes at the back list the cataloging number and the species as well as the place and date (often in the late 19th or early 20th century) of each nest’s being collected. This sourcing for the volume’s visual elements calls attention to how Western humans have related to the natural world by attempting to categorize, control, and manage it as something apart from themselves—often without regard to the destruction involved. To preserve the nests for human study, collectors took them from the places where they might have sheltered additional clutches of eggs, where they would eventually have decayed and nourished other lives in the ecosystem. Moreover, many of the photos offer evidence of humans’ pervasive impact on the environment and other species in it, revealing bits of newsprint (with letters and occasionally words still legible), twine, fabric, even a piece of sleeve with a sewn button-hole that are woven into the nests along with the not-human-generated twigs and plant fibers, leaf fragments and seed heads, feathers, horsehair, and, in one, a piece of snakeskin. Readers are reminded that our detritus is everywhere, and other species have had to adjust to that transformation of their habitats.

Figure 3 is a sample photo, a blue-headed vireo nest collected in 1890:

The wondrous character of the images encourages in readers the closest possible attention to more-than-human life forms and the architectures they construct, both within and beyond

Edges & Fray. The text accomplishes something similar by informing the reader of how particular nests are made, e.g.,

| a red-winged |

| blackbird |

| low / among vertical shoots -- |

| soaked marsh vegetation |

| stringy plant material |

| woven to gather |

| upright stems |

| a platform / / |

| |

| wet leaves / decayed wood |

| plastering the inside with mud |

| to make a large, open cup |

| |

| |

Yet Vogel’s deployment in one poem of diacritical marks to convey a hummingbird’s movement in a field or, in another, to suggest water surfaces registers the inadequacies of verbal depiction alone. The photos’ fine detail that sometimes blurs into ethereal patches of color substantially enhances readers’ grasp of the remarkableness of avian architectures.

The parentheses around “invisible” in the book’s subtitle point to the book’s revealing what is usually unseeable to humans, or simply unseen by humans, due to their existence at scales we too rarely attend to. The ruby-throated hummingbird, for instance, typically constructs its nest ten to twenty feet up in a tree with exterior dimensions of one to one-and-three-quarters inches across and one to two inches in height. No wonder most of us have never seen one! Vogel’s text allows insight into this nest’s extraordinary formation: the hummingbird starts “with a disk / of saliva // moss . lichen / then, it’s a matter / of catching webs // vegetation / silk” (

Vogel 2020, p. 14). The photos are equally key to

Edges & Fray’s revelation of the usually invisible; indeed, the intense close-ups in which strands of hair or thin twigs loom large bring the viewer’s perspective much closer to a bird’s. At one point Vogel appreciatively observes, “nests have taught me about the miniscule -- / -- that haunts toward the whole” (

Vogel 2020, p. 47). This scalar shift into the unfamiliar miniscule is also a shift away from anthropocentric perception.

While her photos derive from museum exhibits, Vogel herself has been out in the world observing and attempting to incorporate into her writing more-than-human life processes. Her attention includes but goes well beyond ordinary observations like “I’ve watched the swallow scoop clay with its beak / deposit the silt / against its nest” (

Vogel 2020, p. 40). For, as Vogel states on her website,

For well over a decade, I have devoted my practice to infusing English language grammars with what I think of as the “organic grammars” of elements, plant and mineral beings, ecosystems, and bioregions. What can human languages learn from—or remember through—the organic, polyphonous intelligence and the innately reparative or regenerative logics of specific water bodies, clay and ochre deposits, plant beings, environmental entanglements, fields of light, or currents of air? What becomes possible when we (re)introduce these logics into the body by way of the poem? These questions have been my compass.

Attempting an amalgam of human linguistic grammars with those of the more than human world constitutes another version of trans-vocality. In

Edges & Fray Vogel’s process of “infus[ion]” yields an emphasis on the intensely material energy within words and sentences (e.g., “how I’m revealed / through the muscle / and synapse fields of each syllable”). Additionally, as Vogel cultivates an appreciation of “language’s ability / to bond / to create momentary enclosures” (

Vogel 2020, p. 33), her introduction of non-human logics fosters awareness of the close parallels between a person’s building with language and a bird’s with natural materials

Paying attention to how birds make their nests and discovering profound analogues between human and more-than-human creation transforms Vogel’s understanding of the body’s role in linguistic architectures. Birds use their bodies to shape their nests—a frequently mentioned fact reinforced by the cup-shapes in some of the photos—thereby modeling those very material “logics” Vogel hopes to introduce into the language-producing human body by way of the poem. Thus, one page describes how a bird “weaves a thing / presses its breast / against the circle/inverts itself against the weave ; no , / the weave becomes / its inversion / a shape / that harbors” (

Vogel 2020, p. 57). A few pages later, Vogel depicts herself engaged in a similar activity of creating from her body’s form and thereby expanding her powers:

on the floor , looking outward , gathering until I feel the inward

shape of myself , exteriorly . to make a space for what has always

fled , always refused form , and then to incubate it with

intention , with the very material of what has always held me

Exploring human/avian commonalities also prompts an expansion of voice beyond the singular lyric speaker, as bird and humans may blur. Statements like “we read debris and make seemingly complete shapes” (

Vogel 2020, p. 47) apply to both. The addressee of the following passage cannot be neatly identified as either avian or human:

| start by making a loose ball of words |

| |

| |

| bind it with the cocoons of forest tent |

| |

| catterpillars . your saliva , a sphere around the ball |

| |

| filled -- with finer sounds / to line the cup |

| |

| of the mouth --- feathers -- - fur , pleats of |

| |

| lichen , language |

| |

| |

| to press one’s body against this curve (Vogel 2020, p. 37 ) |

If directed to humans, those instructions recommend that people, as they imitate with words the nest-building of birds, acquaint themselves intimately with the materials of the more-than-human realms, incorporating those materials into their bodies and/or their bodies’ imprint in language. Just as

Edges & Fray cultivates awareness of “an unstable boundary: the body / the book” (

Vogel 2020, p. 35), it dramatizes through its combination of visual and textual materials such profound human/avian commonalities that species boundaries, too, are revealed as potentially unstable. Nest-building non-humans do, however, retain enough distinction to be held up as models for human language and living:

| sentences build in me like swallow huts : |

| |

| |

| muddying the ribs / |

| |

| |

| weighing the muscle |

| |

| |

| |

| to write like the term or killdeer |

| |

| the whip-poor-will or marbled murrelet |

| |

| the duck or goose |

| |

| |

| to start where one lands |

| |

| to hardly alter the surface of the earth (Vogel 2020, p. 54 ) |

| |

| *** |

My final example in this small array of texts intended to suggest the range of forms and uses of verbal/visual/and sometimes musical hybrids being created by contemporary environmentally engaged poets

9 occupies not a full volume but a handful of pages: Jonathan Skinner’s “Blackbird Stanzas.” In addition to being a poet, critic, and editor of the groundbreaking journal

ecopoetics, Skinner is a skilled birder. Much of his poetry has emerged from experiments involving bird songs or calls

10, and, having done extensive field recording, he has come to think of vibration, whether in the substrate beneath our feet or in the atmosphere rising overhead, as “the communication model for ecopoetics” (

Skinner 2017, p. 235). While acknowledging that “the dual role of sound waves—to communicate but also to echo back and in so doing to sound the substrate, in the submarine sense of ‘sounding’—has been exploited by the hydrocarbon industry to map the subsurface lay of its prospects’ (

Skinner 2017, p. 237), Skinner sees possibilities for ecopoetry in recognizing that the “seismic channel also vibrates at the heart of our ‘social media’ (

Skinner 2017, p. 238) when the social network’s devices “interface with bodies, with Earth’s gravity, and with the surrounding magnetosphere.” For Skinner,

Communication in the seismic channel means attending to distant bodies, absent bodies, difficult bodies, prosthetic bodies, beyond the echo chamber and groove of eros—in the promising if darkened reach of the manifold body of Earth and its open circuits. There are, of course, other models for ecopoetics. Much can be accomplished within the high fidelity, sharply encoded signals of closed circuit communication: birds sing there too. You can reach bodies that speak your language with very specific instructions. Vibrational communication does not, however, reach from abilities and fluencies but from the disabling interconnections that constitute the very possibility (and necessity) of communication.

Just as Ellis seeks to be true to their “disability’ and uncover its “dysfluent” resources in their writing, Skinner pushes us to listen ever more carefully to the vibrations of our sonic surround without imagining that we can understand or speak the languages of non-human animals. Acutely aware of the limitations of human sensory organs—of our eyes that do not see in the infrared spectrum or our “lumbering” ears that do not register the ultrasonic and whose minimum unit of attention is much larger than a bird’s—he has often turned to spectrograms of bird vocalizations as a way of enhancing his listening with sight. These digitally produced images developed from slowed field recordings—recordings in which the scale has been shifted to better accommodate the limits of human hearing—track the varying frequencies of sound over time and register amplitude (volume) in the intensity of color. They reveal in greater detail than our naked ears can discern the multiple parts of bird vocalizations. “Finding ways to see what we hear offers a purchase into translations that become ways of performing other than human being,” Skinner claims (

Skinner 2017, p. 244). That is, these visual aids to our listening allow a potential transspecies expansion of the human speaker.

Skinner’s “translations” of bird song that have been aided by spectrograms often have not included those images in publication. “Countersong,” for instance, responds to a three-minute recording that captured two dozen exchanges between two Hermit thrushes he heard in northern New Mexico. Though leaving him still unable to “enter the musical microcosm of the Hermit thrush song,” the spectrogram of the slowed recording enabled Skinner to follow the “overall winding patterns” of the exchange. (Trans-vocality here is a goal humans can approach but not lastingly attain.) The published poem omits the spectrogram, yet the words attempt to register its patterns while page space sounds the silences between the vocalizations. In an ongoing project of “Birdsong Karaoke, a performance genre,” Skinner uses slowed recordings independent of visual images:

I play back birdsong at half or quarter speed and read or sing along lyrics composed to fit the bird’s tune. The bird is the composer and I am just trying to sing along with my poor human vocal cords. I often fail, but where there is a match, it’s as though I get to be the bird, for a brief instant, and the audience gets to hear birdsong in human language. If all that comes of the experiment is heightened attention to the specifics of these avian performances, then I am happy.

When Skinner performs the “Blackbird Stanzas,” he similarly runs the recording as a “backing track for my attempt to vocalize, karaoke style, the [European] blackbird’s song.” “Ideally,” he adds, “software would allow me to scroll through and follow the spectrogram as I sing, but we are not there yet” (

Skinner 2017, p. 243).

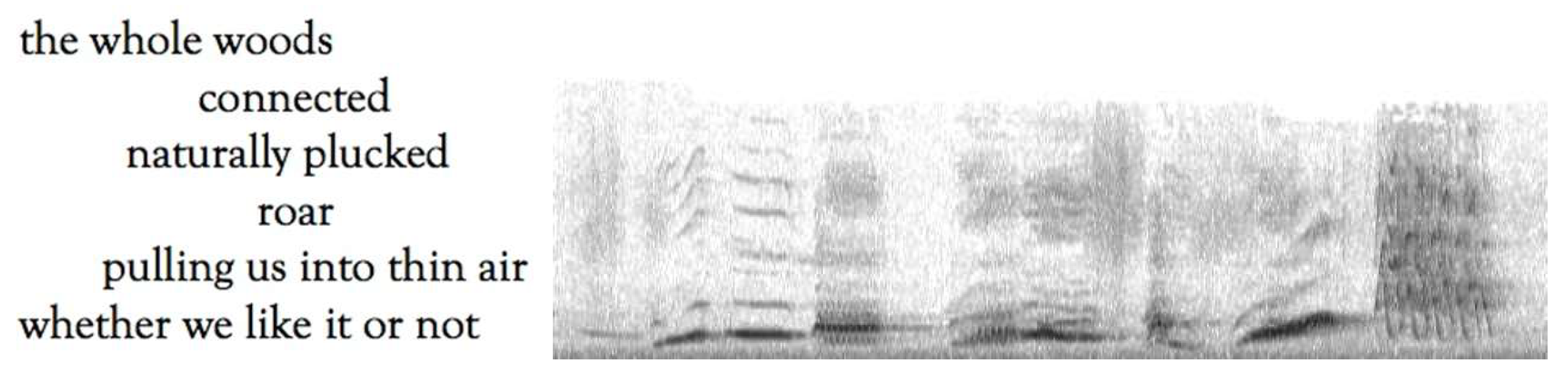

Fortunately, the print publication of “Blackbird Stanzas” in the anthology

Big Energy Poets does include the eleven spectrograms on which the poems were based, so that readers can attempt to follow the interplay of visual information and text.

Figure 4 displays the first of the stanzas and the spectrogram of the Eurasian blackbird to which it responds. (The Eurasian blackbird, unlike the American red-wing blackbird, is a thrush, an avian family known for their beautiful songs.)

As is true for all the stanzas, the words come from interviews Skinner conducted with scientists and do not attempt to reflect bird consciousness. In trying to understand the poem as a response to the image as well as the sounds behind it, I consider Skinner’s division of the image into six units, translated in six lines. As I read it, the column of fairly solid gray slightly more than halfway through registers as “roar,” while the streaks moving diagonally upward become “pulling us into thin air,” and the darkness (louder volume) of the section at the end registers as the resistance implicit in “whether we like it or not.” As with the other hybrid poems I have examined, in which the visual elements are not simply illustrations, the interpretive challenges for the reader are considerable. The multi-modal presentation on the page enhances readers’ recognition of the complexity of bird vocalizations and of the distance between species and between the scales of their sensory worlds, even as communication is attempted. Including the scale-adjusted visual record of bird song emphasizes for the reader the difficulties humans face in trying really to listen to other species. Yet the visual/verbal hybrid provides a tool for attempting just that.

All these texts, as they demand that readers focus attention on several media and their interactions, call for more careful and humbler attention to the world we inhabit. They reveal our ignorance, our misunderstandings, our limited sensory powers, our missteps, our sometimes disastrous and sometimes wondrous trans-corporeal and ecological entanglements in more-than-human realms. By enlivening through multi-arts ensembles our visual, aural, and semantic awareness, they push us to use the powers we do have to attend with still more care, to unlearn and learn anew, in order to live more wisely and respectfully on this planet.