1. Introduction

Data-driven, machine-learning-based AI technologies have gained increasing attentions recently across academic, industrial, commercial, and public spaces. However, with the accelerating development of AI also comes concerns around its social, cultural and ethical implications. We want to use the medium of videogames to explore this tension, and develop a critical game where the player is encouraged to reflect on contemporary issues of AI. To this end, we deploy critical game design, as Malazita and O’Donnell describes, “the deep synthesis of game design, cultural critique, and reflective design research practices”

Malazita and O’Donnell (

2023). This article aims to show not only how contemporary issues around AI are reflected in our game design, but also how our design goals made us reflect on the very established principles of game design itself.

We present our project

Sea of Paint1—a narrative-driven game with a custom-made text-to-image system. The game is set in a sci-fi world where big data has become a naturalized part of the world and where “spirits” can be conjured based on machines—as analogs of AI. We identify our design approach in this article as non-ludo-centric. We define ludo-centrism as having mechanics as the center of game design, with narratives and audiovisuals at the periphery. Decentering mechanical design means that each aspect of our game (mechanics, narratives, visuals) includes significant decisions that can afford or constraint decisions in other aspects—the meaningfulness of one aspect cannot be considered without the other. Theory-wise, this article aims to challenge the ludo-centric game design languages and models standardized in education and academia. It does not seek to claim that our design process is novel, rather, non-ludo-centric design decisions already occur in practice without being framed as such. Our design process starts out with themes around issues of AI, and then explores ways the game can realize those themes.

To this extent, this article aligns with framing our game through the research and design approach, developed mostly within the field of HCI (Human-Computer Interaction), where “the resulting designs are seen as embodying designers’ judgments about valid ways to address the possibilities and problems implicit in such situations”

Gaver (

2012). Through specification of our project and design decisions, we hope to demonstrate a particular approach to develop a critical AI game. Near the end of the article, we offer insights on the design elements that designers can utilize to promote criticality in a non-ludo-centric way.

It should be noted that, at the time of writing, the game is still very much incomplete. The general mechanics, characters, and the narrative beats are largely finished, but the writings and artworks are still in progress. The decisions discussed in this article are largely set in place and will be specified if otherwise. Our specification should provide a general idea of the design direction of the game, and therefore, are applicable for design reflection provided in this article.

We’ll briefly discuss the intellectual background of our work in

Section 2, including an overview of ludo-centrism. We introduce our game and its themes in

Section 3, and then discuss the specifics of design in

Section 4.

Section 5 will provide general design reflections and suggestions based on our design practice.

2. Background

2.1. Ludo-Centrism in Game Studies and Game Design

Ludo-centricism has a rather long and complicated story in the studies of games. It has its roots in defining the distinct properties of games compared to other media. Early game scholars defined a game’s ludic qualities: interaction, participation and the rules/systems, as the formal properties of the medium. Even the debate between narratology and ludology, which marked the founding of game studies as a field

Aarseth (

2001), did not disagree on this formal definition, rather on the degree to which studying rules/systems needs its own methodology, separate from those of other fields such as literary studies

Frasca (

2003);

Murray (

2005). Interaction here takes on a particular meaning as the “nontrivial efforts” required to navigate the artifact (

Aarseth 1997, p. 94), or as Lantz puts it, “what looking is to painting, listening is to music, […]

thinking and doing are for games.” (

Lantz 2023, p. 26, original emphasis). Game also distinguishes itself because of its configurability—the fact that it “restructures itself” (

Galloway 2006, p. 3) and grants the user that configurative power (

Aarseth 1997, p. 164). Thus, ludic qualities can be appreciated in their own terms because interaction becomes a distinct way of media engagement and configurability becomes a distinct property of games, as Lantz proposes, “games are the aesthetic form of thinking and doing.” (

Lantz 2023, p. 27).

As a result, game design becomes a discipline that mainly tackles the craftsmanship of rules and systems for play, as distinct from storytelling

2 and audiovisual design. This is quite evident in game design textbooks

Adams and Dormans (

2017);

Anthropy and Clark (

2018);

Sellers (

2017);

Zubek (

2020), which focus mainly on designing game rules such as goals, mechanics, systems, rewards and difficulties. But games, especially computer games, are nevertheless multi-media and multi-sensory experiences. How much other qualities of games would relate to their ludic qualities remains somewhat ambiguous. Game designers and scholars largely see them as equally important to a game, thus theoretically do not endorse ludo-centrism. For example, Hunicke et al.’s MDA model (Mechanics, Dynamics, Aesthetics)

Hunicke et al. (

2004) is often recognized as one of the most influential game design models. But the word choice of “mechanics” (game components that designers have direct control over) and “aesthetics” (subjective experience of play) were criticized for reinforcing “pre-existing concepts like ’gameplay vs. graphics’ or ’underlying system vs. surface qualities’ or ’abstract rules vs. images and story’ […] It suggests a point of view that considers a game’s assets to be of secondary importance.”

Lantz (

2015). The model was either reworked

Walk et al. (

2017) or was acknowledged for its limits (

Zubek 2020, p. 9), but because of the focus that game design puts on rules and interactions, narrative and audiovisual aspects have to be considered out of scope and have somewhat limited functions in game design education. Anthropy & Clark would discuss visual, animations and sound in terms of “context” to “help a player to internalize those otherwise-abstract rules” (

Anthropy and Clark 2018, p. 77). Zubek would discuss narrative structures as “content arcs” and frame narrative design mostly through choice structures (

Zubek 2020, p. 152).

It is within this context that we define our approach as beyond ludo-centric game design: what does game design look like when rules/systems, visuals and narratives are placed on equal footings, where decisions made in one would implicate decisions in others, and the meaningfulness of one aspect cannot be considered without others? We have no doubt that this crisscrossing decision-making is not new to game design practice, but making them explicit pushes them to assume a position where these decisions deserve to be discussed and studied. This is additionally significant when one considers how game studies has moved to acknowledge the audiovisual (

Keogh 2018, p. 135) and affective

Anable (

2018) qualities of play, and how game design education is still very technical

Howe (

2015) and split design and engineering with humanities in the institutional context

Malazita and O’Donnell (

2023), thus marginalizing many disciplines in game development that may contribute to more diverse kinds of games. It is also relevant for the goal of developing a critical game, as Aubrey Anable notes, “In the focus on interactivity and code, we have lost some critical tools for analyzing how video games matter as representation and how they are bound up with contemporary subjectivities” (

Anable 2018, p. xv).

2.2. A Critical Game with AI, About AI

Yannakakis & Togelius summarize the field of game AI as mainly three branches: playing games, generating content and modeling players

Yannakakis and Togelius (

2020). Many AI algorithms, machine-learning-based or not, are developed for these three purposes. Nowadays, with the rise of generative AI, it is increasingly being seen as the foundation of a potential new media paradigm. Sun et al. would present their game

1001 Nights Ada Eden (

2001) as what is called an “AI-native” game, where generative AI is “fundamental to the game’s existence and mechanism”

Sun et al. (

2023). Although generative AI offers many new possibilities for game design and research, most current applications remain in an early and underdeveloped stage where design considerations are still being explored

Samuel et al. (

2021);

Yang et al. (

2024);

Zhu et al. (

2021). Our game utilizes a small sentence transformer model for our more rule-based text-to-image system, whose purpose mainly aims to provide an interpretation of the dynamics of machine-learning-based text-to-image interaction rather than adopting widely-used text-to-image models such as Stable Diffusion.

Overall, it is evident that the current research on game AI primarily focuses on their engineering and design aspects, with not much discussions on the value of games as a medium for exploring AI’s impact on humanistic and societal dimensions. We seek to promote criticality towards AI as inspired by the field of critical AI, including discursive critique of generative AI

Bender et al. (

2021);

Birhane (

2021), big data

O’neil (

2023), hidden labor

Gray and Suri (

2019) and extractivism in production

Crawford (

2023). This is also why we adopt a non-ludic centric approach—we believe different topics and questions are explored more efficiently through different forms. For example, we created one of the main characters as a data worker so our narrative can include many research and reports around the current condition of data labor.

We define our critical game in a looser way, in contrast to other more specific genres of games or design methodologies that promote reflection and criticality such as serious games

Laamarti et al. (

2014) and persuasive games

Bogost (

2010). It is a critical game because criticality towards current state of affairs is the core design goal that guides our design decisions. As Flanagan defines, a critical game/play would “occupy play environments and activities that represent one or more questions about aspects of human life […] be fostered in order to questions an aspect of a game’s ‘content’” (

Flanagan 2013, p. 6). However, we also took the liberty to develop fictional settings and characters for dramatization and appeal.

3. Sea of Paint

This section will provide a brief overview of the in-progress game

Sea of Paint. To reiterate, the game is the main case study of this article in order to illustrate a non-ludo-centric game design approach that emphasizes game rules and systems’ symbiotic relationships with other media forms. The mechanics, characters, artworks and narrative beats are fully laid out and in production.

Section 3.1 will go over the game’s general setting, story and gameplay. And

Section 3.2 will lay out the current themes the game is trying to explore, as the core orientations for design specifications in

Section 4.

3.1. Game Overview

Sea of Paint is a narrative-driven game that combines dialogue-driven interaction with text-to-image generation as its core gameplay loop. The game is set in a sci-fi setting based on the current boom of data-driven and AI technologies. The current version of the introductory text gives an overall summary for the world and the narrative context around gameplay:

The Sea is everywhere, all around us. Every minute, traces of ourselves dissolve into the man-made Sea. A whole continuously breaks into parts to become the Whole again.

Machines were developed to harness the Sea. Machines that bring back the spirits. Machines that can produce words like a person. And machines that can turn words of the spirits into images.

I’m an operator of one of these machines. As per the grieving’s request, I am contracted to temporally bring back the deceased.

Just have to remind myself first: the beginning is always the hardest. Be patient and be kind.

The Sea and the Machine are direct analogies to data and current data-driven artificial intelligence technologies such as large language models and text-to-image models, with some magical realist and supernatural motifs to help integrate the themes and add flourishes to the premise. The game aims to be a one-hour session where the player will switch between conversing with the “spirit” and generating images that supposedly capture the spirit’s experiences. The conversations and images will revolve around the life of the spirit’s experience as a data worker, a once-aspiring writer, a working mother, someone exposed to the uncertainty around technologies, and someone whose current existence is mediated by that very technology.

The main way to progress through the game is finding the keywords or the code words for the text-to-image interface through dialogue. If the player attempts to generate images without the keywords, the game’s image generation system will output an image with two image assets blended together. The play loop consists of the player conversing with the spirit to infer words to unlock the unblended image asset.

The ending sequence will become available once the player unlocks three out of five images. The player is granted the agency to choose how to remember the spirit, where the player can generate images as memorabilia. While the blended images are framed as undesirable during the main game loop, since the goal is to unlocked the unblended images, the ending will acknowledge them as legitimate ways to narrate the spirit’s past.

3.2. Themes

Sea of Paint is a theme-driven game, as in, its design is oriented towards exploring questions and exposing problems around the current development of AI technologies. This gives a certain flexibility to some design elements while fixing others in place. For example, the character backgrounds, the world, as well as the dialogue are developed based on their contribution to the themes. This subsection will list three main themes that we have identified as core to the game.

Section 4 will further detail design elements based on these themes.

3.2.1. Visual Meaning-Making and Text-to-Image

As part of the core mechanics, text-to-image generation is a thematic focus explored mainly through interactive design. This theme can be broken down to two topics: firstly, meaning-making through visuality and secondly, visual creativity through text-to-image generation.

The first topic mainly focuses on designs that encourage the player to engage with meaning-making activity through visuality, instead of typically narrativity or interactivity in the form of games. Compared to games about visual creativity such as

Chicory Lobanov (

2021) and

Passpartout 2 Flamebait Games (

2023), where the player is given narrative context and simplified drawing tools to be visually creative in the game, the game is much more restrictive in terms of authorial freedom. The game will first function more as a database adventure game where the player discovers how to unlock different images. But the game will prompt the player to interpret the images within the context of the narrative, as detailed further in

Section 4.1 and

Section 4.2.

The second topic centers around how the interactive modality of text-to-image is distinct from more well-practiced methods of visual creation, such as drawing and painting. This is inspired by Zhou et al.’s theorization

Zhou et al. (

2024), where they argue that text-to-image habituates a different form of intention through recognizable ideas and objects, where low-level visual decisions are made by algorithmic generation. We explore this interactive dynamic through the design of our image generation system and its framing within the narrative, as discussed in

Section 4.2.

3.2.2. Consequences of Data-Driven AI Technologies

This theme focuses on the various ethical concerns around the recent boom of data-driven AI technologies. We aim to realize this theme mainly through the narrative, where a substantial part of the story and setting are grounded within contemporary issues of AI, as further discussed in

Section 4.3. Thus, instead of exploring sci-fi topics that can be more abstract, the narrative intends to be more representational and research-based. These concerns are introduced through fictional setups such as the spirit’s past life as a data worker, and the history of the Sea as an analogue for big data. The narrative decisions will be informed by research such as realities of data workers in the production of current data-driven AI, as well as the discourses and histories around data and big data.

3.2.3. Memory and Remembering

We see this theme as central for the development of different story beats. We are particularly inspired by the philosophical discussion around enactive memory

Caravà (

2023). Instead of thinking about memory as storage and representation, and remembering as retrival, the enactive memory thesis argues that memory is the “dynamical coupling between the agents’ brains and bodies, and the sociomaterial environment they inhabit” (p. 2), and remembering is more “action-like.” This is most explicit in gameplay progression, where the spirit has to remember their memory through the assistance of the player.

The enactive memory thesis also helps us relate to the concerns of critical AI by highlighting the sociomaterial nature of memory and remembering. There are many story beats that can relate to this point, such as the Sea (analogue to big data) as a technical and institutional construction, tech-enabled personhood as inevitably linked to corporate practices (inspired by

Birhane et al. 2024), and real humans behind the scene such as data workers becoming forgotten and marginalized. The very presence of the player character as a contracted worker, and is needed for the spirit’s memory, draws in questions regarding how the player character’s personal interests distort the spirit’s own memory. This will be further discussed in

Section 4.3.

4. Designing Beyond Ludo-Centric Models

Having reviewed the central themes of the game, this section will detail current design specifications to realize these themes. In addition, the section also aims to illustrate how the designs of these different aspects (mechanics, visuals, narratives) are inter-dependent, instead of understanding these three different aspects of the game as having fixed relations to each other (such as the visual as decoration and narrative as content). Each decision, no matter the aspects, is made with the intention to serve the themes and to shape the interactive experience. The design decisions discussed here are mostly finalized with some yet to be implemented. The text would make explicit which aspects are not yet finished.

4.1. Visual Design

For Sea of Paint, the visuals have a significant place in the game. This is in contrast to more ludic-focused game design, in which gameplay would either take priority or be treated as separate from visuality (in this sense, the common practice of grayboxing/blockout implies an interpretative practice that determines the extent visuality matters to gameplay). For Sea of Paint, visual design is interactive design, with feasibility and quality of the visuals necessarily implicating the interactive system itself.

We made the decision of using dithering as the stylistic motif across all of our artwork. In computer graphics, dithering is a technique that applies noise to imply a more granular gradient of colors. It typically looks like two colors are interlaced in variable patterns to imply a gradient between the two. Applied intentionally, dithering can artistically evoke an ambiguity of form, where concrete shapes and figures come in and out of discernibility among the visual noise. We find this feature attractive, as the main fictional invention of the narrative is the sea, as an analogue to big data. As the theme of memory in

Section 3.2.3 states, the game explores this tension of individuality and authenticity as constructed from data. The sea is supposedly “everywhere, all around us.” We seek to utilize this visual motif as part of the theme, as shown in our sample artwork in both

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

Since the main interactive feature is the text-to-image system in which two artworks are blended together, much time and thought have been devoted to how such mechanized process can produce something aesthetically pleasing. This is a core part of making the text-to-image system engaging, and also complements the final narrative beat of the game, in which the player is asked to treat blended image as meaningful in itself. We interpret blending as a visual way to communicate connection. Regardless of what is being blended, the player registers a connection between the two layers and interprets based on contextual clues in the image or game dialogue.

For example, there are already many possibilities when the two figures are blended together. If the figures seem to be the same person, a blended version connects them through distinct moments, giving a fuller view of the character’s life. This especially comes through when the two images have contrasting features, such as differences in time, mood, or activity. If the figures are distinctly different persons, the blended image communicates the connection between the two, such as how one is important to the other in their life, or that one figure is thinking about the other figure. We organize the span of our artwork with these possible blended meanings in mind.

Figure 1 showcases some examples of our artwork, where one image is blended with three different images.

We want to reinforce how the generated images are distinct ways the game narrative unravels itself besides the game dialogue and enable different interpretations of the story, as part of the visual sense-making theme discussed in

Section 3.2.1. Once an image is unlocked, the game will ask the player to interpret the image. To use the person walking and smoking in

Figure 2 (or the middle of

Figure 1) as an example, the player is asked to choose whether the image shows the person being angry, detached or stressed (included in the playable intro link). The player is thus asked to examine the artwork to its fullest extend. This is the instance where remembering the spirit’s memory is entangled with the player character as well as the player’s agency, which complicates an idea of “authentic” remembering, as discussed in

Section 3.2.3.

Because part of the interactive loop is to prompt the player to interpret the image, and to create blended images that can be read meaningfully, the design of the artwork has to be intentional in leaving the possible takeaways open. One technique we utilized in the artwork is to obscure the interiority of the character in the image. Take the seated person in

Figure 1 as an example, the facial expression was fine-tuned extensively to give an impression of her being in deep thoughts, without clearly communicating what the thought is about. The secondary image, then, can be interpreted as the explication of her thoughts.

4.2. Text-to-Image System

The decision was made early that the system will not rely on existing diffusion-based models such as Stable Diffusion, DALL-E and Midjourney. Besides the computational overhead and ethical concerns over models trained on non-consenting data, diffusion-based models are simply too general to control their interactive limits within the game. Additionally, the consistency for the characters, setting and tones also requires control. We anticipate heavy mechanisms and vigilant testing if we were to adopt diffusion-based text-to-image models. As a result, we resorted to a custom-made and narrower text-to-image system, where the generation mechanism is constrained and predictable.

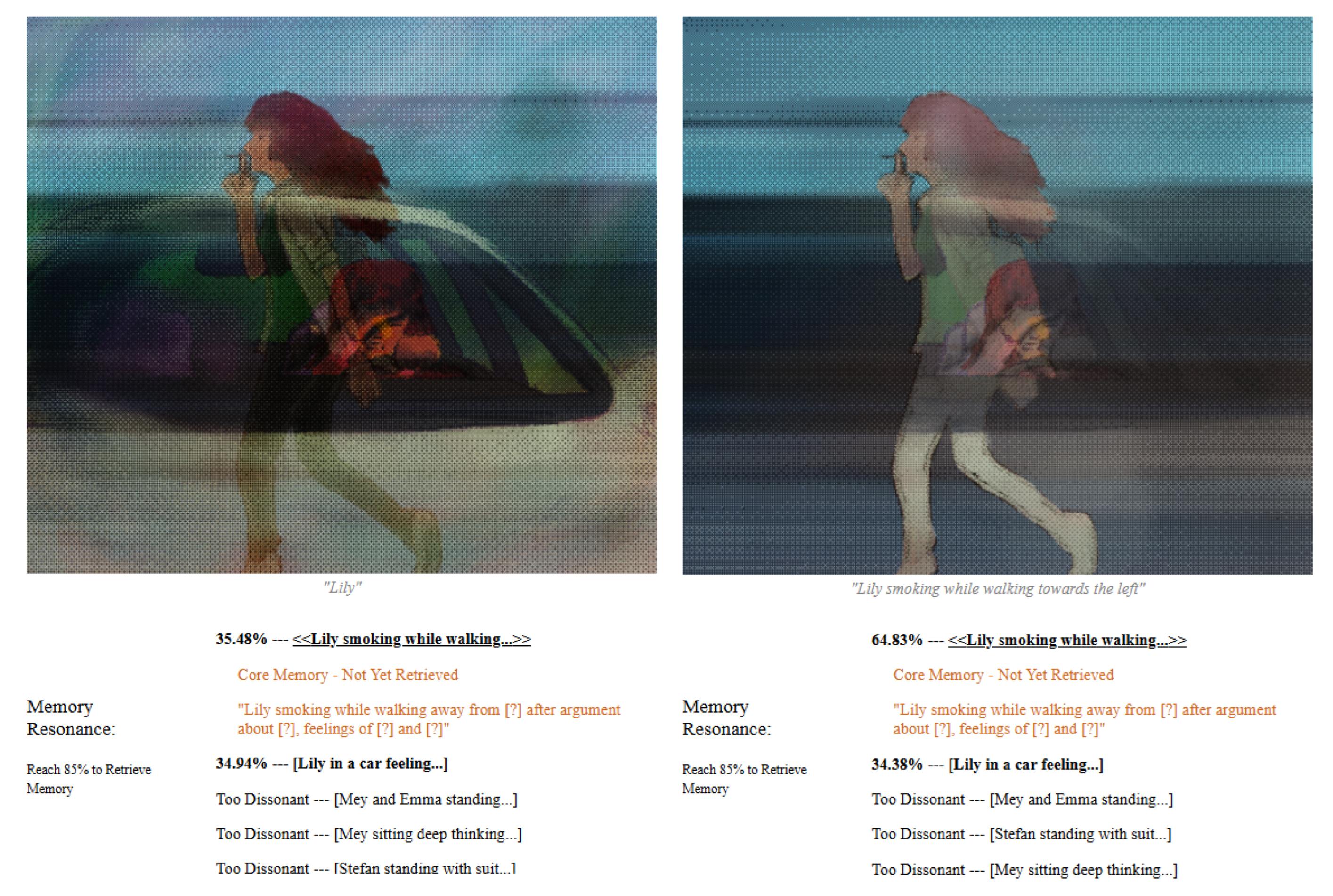

The system mainly operates on images hand-drawn by the authors that are intended to be aesthetically pleasing and narratively meaningful. The main gameplay tasks the player to find keywords in the dialogue to unlock each hand-drawn image. Most of the time, the system will blend two images together and render a new image. Two sample interaction results are shown in

Figure 2.

A sentence transformer is used to pick out the image—the only machine learning model used in this system. Each image has its own description that is measured against the user prompt and returns a similarity score. If the prompt is not sufficiently close to any description, the system returns a white noise, signaling that the user cannot simply enter whatever they want. The system randomly picks two images with sufficiently matched descriptions to blend. If one or more descriptions reach a certain threshold of similarity, the system will pick the highest matched one to blend with the second. Depending on the difference in similarities between the blended images, the system interpolates between different blending methods, resulting in different looking images, as shown in

Figure 2.

The similarity scores are fully displayed to the users. In addition, a part of each image’s underlying description is also displayed to the player (e.g., “Lily smoking while walking away…”, more discussion on the obscured words in

Section 4.3). The overall system is quite deterministic and much information is fully displayed to help the player quickly orient themselves around the system. Early playtesting indicated the necessity of this, as text input gives player too much freedom to fully comprehend how the system works under the hood.

Using the system has two distinct phases. The first phase is the player finding an unlockable images and then trying to match the text description for a specific image. This gameplay is similar to database games such as

Her Story Barlow (

2015), where the player navigates through pre-made assets to construct the overall narrative. This way, each image becomes “content” for the progressing through the game.

The second phase comes near the end of the game, which is yet to be implemented, where the player is asked to give interpretations to the spirit’s life through blended images. The player is asked to intentionally choose the two images to blend by mixing the image descriptions together. This is where the player has some form of creative control, because they have general idea of what the prompts are, while still largely relying on the algorithmic generation and text-based curation for the final result.

While not using diffusion-based text-to-image model, this gameplay system does a particular interpretative work of text-to-image activity: the player gets a sense of what text is valid and invalid to the system, and then does curation over the image results of the text inputs. The player is encouraged to continuously click on the generation button to explore a satisfactory generation of results. This is the intended dynamic, as

Zhou et al. (

2024) points out, the users tend to continuously click on the generation button for games that utilize text-to-image models. At the same time, overusing the system is discouraged, framed as the generation hurting the spirit. This interactive setup asks the player to find a balance between exploring new results and committing to one. The punishment for overusing the system is discussed in

Section 4.3.

4.3. Narrative Design

To develop a critical AI game, we want our story to be faithful to the current ethical concerns around AI, as

Section 3.2.2 describes. This means that we mainly develop the world, the characters and their stories from current research and reports around the development and production of AI. We design the spirit’s past life as a data worker, who gave up on her writing aspiration to choose a more stable family life.

Since the story is largely fictional and set in a sci-fi universe, we have a greater authorial freedom on how to represent certain facts and issues through the narrative. It is a case by case basis whether we decide to completely replicate the facts from the research, or to ambiguate certain details, or to extrapolate certain patterns we observe in the research. For example, we found that Chinese data workers tend to work in an office-like setting

Li (

2023);

VICE News (

2019), while data workers in other regions tend to work remotely

Alrayes (

2024);

Fuentes Anaya (

2024). We decided to design the spirit’s work as in-person to better introduce interpersonal drama without regional information. Other details such as the exploitation and discrimination in the workplace

Li (

2023), as well as the emotional stress for content moderators

Anonymous (

2024), are replicated as faithfully as possible in the dialogue. Other facts such as the California bill CJPA, originally proposed to support newsroom and journalists, being hijacked to accelerate the adoption of AI

Reilly (

2024), are reduced to very brief and vague mentions in the context of why the spirit did not choose the path to be a writer. We seek to strike a balance between being informative and representative of real-life concerns of AI and being conscious of the each detail’s relevance to narrative development.

To progress through the game, the player has to unlock a number of “core memories” around significant people in the spirit’s life, illuminating the spirit’s overall life story (e.g., family, work, internal struggles). The missing keywords are sorted into two categories: information about the specific moment in the memory and the spirit’s own feelings around that memory. The player needs to engage in dialogue with the spirit about that specific memory to find the keywords. For the first kind of missing keywords prompt the player to engage with the spirit in an inquisitive way, trying to find specific details about the moment to piece the missing pieces together. The second kind of missing keywords allows the player to reflect on the spirit’s own subjectivity. A feature currently in development at the time of writing is the highlighting feature so the player can highlight dialogues and then refer back to them quickly when trying to unlock the memories.

Additionally, as

Section 4.2 discusses, the game would have a mechanism to punish overusing the text-to-image system. This is framed as the system needing to draw from both the spirit itself and the Sea, and the overuse of it would cause the spirit to lose their individuality to the Sea. When the player overuses the system, the text-to-image will automatically return back to the dialogue interface, and for the next conversation, a simple generation system would scramble the written words at certain moments to make the content a little harder to parse. For example, “That sounds ridiculous” would become “That cannot be seen and will recognize them and the places visited remained uncertain sounds ridiculous”. The generation system is a Markov model trained on a small selection of classic literature.

Throughout the dialogue, there will be explicit options to “[affirm]” the spirit. This tends to take the form of praising the spirit or affirm the spirit’s identity as a living being. This is given a similar narrative reason as to above, where the spirit needs to be “affirmed” to not lose themselves to the Sea. A successful affirmation has the chance to increase the allowed number of image generated. This gameplay consequence is communicated to the player explicitly (included in the playable demo). But what is not communicated to the player is that some options will appear to be to patronizing to the spirit. The game keeps the difference between the two hidden. When too many patronizing “[affirm]” options are picked, the spirit will initiate conversation with the player to discuss that fact. This narrative mechanics as well as the above keyword mechanics serve the gameplay, but also are critical of themselves. The keyword mechanics direct the player to process the spirit’s dialogue in an instrumental way, as well as the affirmation mechanics. This serves the theme mentioned in

Section 3.2.3 by making explicit the player character’s own positionality that continually casts the spirit in an instrumental way. The game goal does not only serve the game form, but also the narrative itself. The player’s change of perceptions and criticality towards the game goal is driven by the narrative design.

It does not take very long to converse about the core memories and unlock enough memories to reach a state where the player can end the game. But much more information and dialogues can be engaged with as optional content, around the non-core memories and follow-up topics after the key dialogue interactions. After a discussion topic is finished, the player is put into a “hub”, where the player is offered to either switch to text-to-image generation or pick another topic. These optional topics offer many insights into the spirit’s life, their interpretation of the characters, and state of the world and the technologies involved in the game. These optional dialogues will change the endings of the game, which are yet to laid out as of the time of writing. The general structure and how much content is offered are mostly fixed in place.

5. Design Reflections

This section briefly summarize lessons and decisions made throughout our design process. We hope these decisions help future game designers, especially those designing games with similar intersections of genres and themes: critical AI, narrative-driven and experimentation with visual creativity. This section also demonstrates that our design work is helpful to further elaborate on the value of non-ludo-centric game design, specifically, how to inform decisions around specific game elements such as game goals.

One particular non-ludo-centric approach is to foreground the premise of the game rules and the game goal. For example, the purpose of the player character to recount memories of the spirit frames the overall game goal and the conditions for story progression. But the fact that this setup draws attention to itself (“why does the player character need to do this, and in this way?”) promotes a kind of criticality towards not only the narrative, but also the game itself. Early playtest showed that the player is immediately uncomfortable between the extractive dynamics underlying the player character and the spirit. The game rules and goals, typically taken for granted and inevitable in a game, are constantly challenged on the ground of the narrative. This is also reflected in dialogue choices. The “[affirm]” mechanics is established from the player character’s perspective, but some hidden logics (not all affirm options should be picked) draw attention to the unreliability of this goal. Early in the playable intro, the player also had to lie to the spirit, without alternative options offered. These interactions are intended to draw a separation between the player and the player character, thus encouraging the player to reflect on who they’re playing as throughout the game.

In tackling critical AI topics, we hope to show some solutions to approach the topics of AI. In addition to utilizing the narrative and storytelling to highlight factors outside of the computational nature of AI, such as its social and philosophical tensions, we also hope to demonstrate that a game does not need to utilize AI algorithms in order to examine how they function algorithmically. This is a more prominent concern since adopting machine-learning technologies almost always implicate an infrastructure of data exploitation and high power consumption. To borrow the language from the MDA model

Hunicke et al. (

2004), the game mechanics can conduct a

procedural interpretation of AI algorithms by modeling the

dynamics of interaction without replicating its mechanics and algorithms. In

Sea of Paint, the text-to-image system likens text-to-image interaction to a recombinatorial practice of existing data, and some sense of player freedom is provided through different image blending results by prompt-mixing.

6. Concluding Thoughts

This article gives the conceptual justification for a non-ludo-centric approach to game design. We position ludo-centrism in the historical development of video game studies and game design education, and experiment with non-ludo-centric design to create a critical AI game. The outcome of this research through design practice is a small set of design decisions that may serve as inspiration for future designers.

Nevertheless, extended playtesting is needed to continuously assess how the approach is effective at promoting criticality. But we refrain from thinking of playtesting as a way to verify our design theory or approach. HCI researcher William Gaver would comment that theories coming out of research through design is not “extensible and verifiable […and] tends to be provisional, contingent and aspirational”

Gaver (

2012). A rigid verifiability of our design also betrays the artistic aim of making a game, where the intent is always under negotiation and there’s no clear designation of responsibility for having a final say in what the game might mean. Indeed, even the direct parallel between Big Data and Sea, as well as the Machine and AI can be missed for those not well-informed or familiar with the game’s critical premise. To this end, the most certain thing we can say is that by working with the game’s mechanics, narrative and visuals, we the authors have come to learn a lot about what the game form can do for the goal of criticality towards AI, and hope to share this game as the accumulation of our discoveries.

We would also like to note that because of the inter-connectivities across the different aspects of the game, the small scale of our three-person team made the quick iterations more tractable. It is an entirely different question to investigate what non-ludo-centric design decisions would look like in a larger scale, where divisions of disciplinary responsibilities become clearer. Regardless, we hope to have demonstrated a space for more nuanced discussions of design, and potentials for more experimental game experiences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z.; Writing—original draft, H.Z., F.M. and K.K.; Writing—review & editing, N.W.-F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project received the Coha-Gunderson Prize in Speculative Futures through The Humanities Institute in University of California, Santa Cruz.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | |

| 2 | It should be noted that interactive narrative is still an actively researched field and has many overlaps with game design. But it is nevertheless not synonymous with game design. |

References

- Aarseth, Espen J. 1997. Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aarseth, Espen. 2001. Computer game studies, year one. Game Studies 1: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ada Eden. 2001. 1001 Nights. Available online: https://ada-eden.itch.io/1001-nights-official (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Adams, Ernest, and Joris Dormans. 2017. Game Mechanics: Advanced Game Design. Edison: New Riders. [Google Scholar]

- Anable, Aubrey. 2018. Playing with Feelings: Video Games and Affect. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 2024. Mind over Moderation. In The Data Workers’ Inquiry. Available online: https://data-workers.org/berlin/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Anthropy, Anna, and Naomi Clark. 2018. A Game Design Vocabulary: Exploring the Foundational Principles Behind Good Game Design. London: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Alrayes, Yasser. 2024. Annotate to Educate: The Dual Life of a Syrian Student & Data Annotator [Coordination by M. Miceli, A. Dinika, K. Kauffman, C. Salim Wagner, & L. Sachenbacher]. Available online: https://data-workers.org/yasser/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Barlow, Sam. 2015. Her Story. Available online: https://store.steampowered.com/app/368370/Her_Story/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Bender, Emily M., Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Shmargaret Shmitchell. 2021. On the dangers of stochastic parrots. Paper presented at the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Virtual, March 3–10; pp. 610–23. [Google Scholar]

- Birhane, Abeba. 2021. The impossibility of automating ambiguity. Artificial Life 27: 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birhane, Abeba, Jelle van Dijk, and Frank Pasquale. 2024. Debunking robot rights metaphysically, ethically, and legally. arXiv arXiv:2404.10072. [Google Scholar]

- Bogost, Ian. 2010. Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caravà, Marta. 2023. Enactive Memory. In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Memory Studies. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, Kate. 2023. The Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Flamebait Games. 2023. Passpartout 2: The Lost Artist. Available online: https://store.steampowered.com/app/1571100/Passpartout_2_The_Lost_Artist/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Flanagan, Mary. 2013. Critical Play: Radical Game Design. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frasca, Gonzalo. 2003. Ludologists love stories, too: Notes from a debate that never took place. Paper presented at the DiGRA Conference, Utrecht, The Netherlands, January 1. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes Anaya, Oskarina Veronica. 2024. Life of a Latin American Data Worker [Animation by V. L. Ochoa-Andrade. Coordination by M. Miceli, A. Dinika, K. Kauffman, C. Salim Wagner & L. Sachenbacher]. Available online: https://data-workers.org/oskarina (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Galloway, Alexander R. 2006. Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gaver, William. 2012. What should we expect from research through design? Paper presented at the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Austin, TX, USA, May 5–10; pp. 937–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Mary L., and Siddharth Suri. 2019. Ghost Work: How to Stop Silicon Valley from Building a New Global Underclass. Manhattan: Harper Business. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, Austin C. 2015. On The Ghost of Formalism. Haptic Feedback. Available online: https://hapticfeedbackgames.blogspot.com/2015/01/on-ghost-of-formalism_62.html (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Hunicke, Robin, Marc LeBlanc, and Robert Zubek. 2004. MDA: A formal approach to game design and game research. Proceedings of the AAAI Workshop on Challenges in Game AI 4: 1722. [Google Scholar]

- Keogh, Brendan. 2018. A Play of Bodies: How We Perceive Videogames. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laamarti, Fedwa, Mohamad Eid, and Abdulmotaleb El Saddik. 2014. An overview of serious games. International Journal of Computer Games 2014: 358152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantz, Frank. 2015. MDA. Available online: https://gamedesignadvance.com/?p=2995 (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Lantz, Frank. 2023. The Beauty of Games. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Xin. 2023. Across China, an Unseen Rural Workforce Is Shaping the Future of AI. Sixth Tone. Available online: https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1014142 (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Lobanov, Greg. 2021. Chicory: A Colorful Tale. Available online: https://store.steampowered.com/app/1123450/Chicory_A_Colorful_Tale/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Malazita, James, and Casey O’Donnell. 2023. Introduction: Toward Critical Game Design. Design Issues 39: 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, Janet H. 2005. The last word on ludology v narratology in game studies. Paper presented at the International DiGRA Conference, Vancouver, CA, USA, June 17. [Google Scholar]

- O’neil, Cathy. 2023. Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy. New York: Crown. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly, Liam. 2024. Google Agrees to First-in-the-Nation Deal to Fund California Newsrooms, But Journalists are Calling It a Disaster. CNN. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2024/08/21/media/google-california-pay-newsrooms-journalists-content-deal/index.html (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Samuel, Ben, Mike Treanor, and Joshua McCoy. 2021. Design Considerations for Creating AI-based Gameplay. Paper presented at the Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital Entertainment Workshops, Virtual, October 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers, Michael. 2017. Advanced Game Design: A Systems Approach. Boston: Addison-Wesley Professional. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Yuqian, Zhouyi Li, Ke Fang, Chang Hee Lee, and Ali Asadipour. 2023. MDA: Language as Reality: A Co-Creative Storytelling Game Experience in 1001 Nights Using Generative AI. Paper presented at the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital Entertainment, Salt Lake, UT, USA, October 8–12; pp. 425–34. [Google Scholar]

- VICE News. 2019. Grandkids On Demand & China AI Workers: VICE News Tonight Full Episode (HBO). YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mXLeBs0fGa4&t=338s (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Walk, Wolfgang, Daniel Görlich, and Mark Barrett. 2017. Design, dynamics, experience (DDE): An advancement of the MDA framework for game design. In Game Dynamics: Best Practices in Procedural and Dynamic Game Content Generation. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Daijin, Erica Kleinman, and Casper Harteveld. 2024. GPT for Games: A Scoping Review (2020–2023). arXiv arXiv:2404.17794. [Google Scholar]

- Yannakakis, Georgios N., and Julian Togelius. 2020. Artificial Intelligence and Games, 2nd ed. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Hongwei, Jichen Zhu, Michael Mateas, and Noah Wardrip-Fruin. 2024. The Eyes, the Hands and the Brain: What can Text-to-Image Models Offer for Game Design and Visual Creativity? Paper presented at 19th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games, Worcester, MA, USA, May 21–24; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Jichen, Jennifer Villareale, Nithesh Javvaji, Sebastian Risi, Mathias Löwe, Rush Weigelt, and Casper Harteveld. 2021. Player-AI interaction: What neural network games reveal about AI as play. Paper presented at 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Online, May 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zubek, Robert. 2020. Elements of Game Design. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).