Abstract

In this study, I expand on the Black feminist tradition of rethinking Black women’s activism by examining how Black queer women’s fashion shows challenge traditional definitions and sites of activism. I present BlaQueer Style as an interpretive framework that largely draws on the wisdom and theories of Black feminism to undercover how these productions and the politics that shape them are not only sites of activism because they challenge the conventions of mainstream cultural institutions, but because they make space for the social and personal transformation of the communities they center. In this analysis of two public LGBTQ+ fashion shows, I argue that intention aside, the Black queer women founders and fashion workers and their practices and performances of centering marginalized communities, using the body to signal and subvert controlling images, and building coalition among these communities, highlight the liberatory potential of their fashion work. In a time when Black queer and trans people are experiencing misrepresentation and other forms of violence globally, BlaQueer Style is what I name the politics that presents a deep commitment to both the aesthetics and the liberation of these communities in Black queer women’s fashion work.

1. Introduction

But the one thing I thought about was that one day way back when, someone sat down, with whoever it is, some gay white man whomever, and they said let’s do this, let’s have a show about blah, blah, blah, and let’s make sure that the models are 5’10” and they’re zero to two, and have very elongated bodies, and alabaster skin, and they all look duplicative of one another, so on and so forth, and this is how we’re going to present fashion. And so, as I started to think about it, I was like well, someone came up with that idea: I’d like for the new model to change– to break that mold.—E. Jaguar Beckford1

Black feminism has long been a project of rethinking Black women’s activism, particularly when accepted definitions of the term activism have focused on organized activities primarily meant to drive institutional change (Collins 2008). Locating how Black women create or circumvent traditional institutions to produce alternative spaces where their work and communities can thrive is one of the many ways Black feminists have sought to redefine activism. For example, Black lesbian feminist Barbara Smith started Kitchen Table Press to find homes for lesbian of color feminist writing that was otherwise met with hostility from mainstream publications (Bailey and Gumbs 2010). Smith and other Black lesbian feminists laid the groundwork for contemporary Black queer women to produce homes for their creative work in times of precarity and violence towards not only Black queer women, but toward the people in the communities they navigate.

In this study, I seek to contribute to the archive of Black feminist theorizing that examines Black women’s cultural work to locate, define, and redefine their activism. I present BlaQueer Style as an interpretive framework to uncover the ways that Black queer women’s fashion work expands our conception of activism. Additionally, I argue that with intention aside, Black queer women are engaging in activism that has the liberatory potential to challenge the misrepresentation, erasure, surveillance and other forms of violence that Black queer and trans people experienced globally during this time. BlaQueer Style is not about simply naming acts of resistance for the sake of doing so. The framework is meant to showcase how disruptions performed in cultural productions often uncover the conventions and systems that undermine the lives of Black queer and trans people. These conventions are often linked to the very ideologies that shape or reinforce the systems and structures that marginalized people navigate. Therefore, even when cultural productions themselves cannot change policies or systems, they can prevent us from settling for the status quo. Cultural productions can represent society as is, and disruptions within those productions can represent what society can become.

This analysis stems from my participation, observation, and documentation of Rainbow Fashion Week (RFW) 2016 and and DapperQ Presents: iD (iD) 2016. RFW is an annual 8-day fashion event that founder E. Jaguar Beckford executive produces. The event took place 17–24 June 2016, primarily at the Caelum art gallery, and other venues in New York City. Anita Dolce Vita executive produces the annual one-day fashion show in partnership with the Brooklyn Museum in New York City. iD is the third installation of the show and took place on 8 September 2016.

Each year Beckford and Vita recruit fashion workers (models, stylists, designers, performers) who are otherwise excluded from the mainstream fashion industry because their non-normative physical features, business models, and politics are not always deemed palatable to mainstream fashion brands.2 While mainstream fashion brands may argue that they promote diversity and multiculturalism, the fashion workers at RFW and iD are often rejected by these brands because they are too urban, too radical, unable to pass as cisgender, too masculine, too short, or too fat. Furthermore, many of these fashion workers’ lack of social and or cultural capital makes it difficult for them to secure the resources and relationships necessary to navigate the mainstream fashion industry successfully.

As decidedly anti-racist, queer, trans and size-inclusive spaces, Beckford and Vita illustrate that fashion shows can be more than attempts to integrate and diversify the existing fashion industry. They show that fashion shows can operate as counter-spaces where queer bodies, aesthetics, senses, knowledges, and histories are central. This was especially important during a time in the United States we were nearing the end of a presidential campaign season that would result in the election of a president that would only intensify the violence against the people in this study. It is not only important that these shows exist, but that they are engaged critically to affirm the humanity of people living on the margins of society.

The first section of this analysis provides a background of RFW and iD and their executive producers. The section includes a brief overview of the performances; the demographics of the fashion workers; the role of digital technologies in making the event accessible, and the strategies for incorporating sociopolitical issues into each show. I draw on the field notes of my observations, photographs, video recordings, and the semi-structured interview with Beckford to analyze RFW and provide a background of her and the show itself. In addition to the field notes I compiled from my observations at iD, I rely on press images and videos featured on DapperQ the website and its accompanying Facebook page, as well as the written coverage of iD, Vita, and past DapperQ fashion shows to provide a background of iD and Vita.3

This second half of the article gets at the heart of the study, which is to deploy BlaQueer Style to examine the liberatory aesthetics and politics embedded in Vita and Beckford’s fashion shows. In my analysis of both RFW and iD, I argue that BlaQueer Style is the ways in which Beckford, Vita and the fashion workers who shape these shows center people and issues that are at times marginalized within LGBTQ+ communities. For example, elements of Black expressive culture embedded many of the shows during RFW disrupt and decenters the whiteness that is often ingrained in queer fashion spaces making room for Black queer and trans children, adults, and elders to engage in self-definition, to signal disciplinary codes, and subvert controlling images or misnaming practices. Similarly, during, iD many of the fashion workers featured provocative clothing designs, demonstrations, and other elements to stand in solidarity with the Movement for Black Lives, centering Black people and their struggles for freedom from state violence. They put into practice the sentiment behind the Combahee River Collective’s declaration that, “If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression” (The Combahee River Collective 1995, p. 8).

“Not your average fashion show” was a refrain that could be found in the promotional materials across digital platforms and verbal communication throughout Rainbow Fashion Week 2016. It is an articulation of Beckford’s desire to break the existing mold for presenting fashion. She argues that if someone can create a vision of fashion that is narrow and exclusive, someone else can also curate fashion shows that are inclusive of diverse body types, genders, races, and sexual orientations (Beckford 2017). Beyond representing marginalized people at these not-so-average fashion shows, both Beckford and Vita show us that fashion shows can be sites of activism that lead to the social and personal transformation of the communities that face dehumanization, particularly during this time in United States history. These fashion workers demonstrate that while fashion shows have maintained the status quo in ways that repress Black queer and trans people, Beckford and Vita’s fashion shows have the potential to reshape political ideas that could better serve these communities.

2. Background

2.1. Rainbow Fashion Week Origins

This section provides a background and description of RFW. I draw on my field notes, photographs and recordings to document the creative vision and mission of the fashion week. My interview with Beckford functions to better understand her vision, her reason for producing a fashion show, and how she brings the show to life logistically and financially. Rather than completely relying on my analysis of RFW, I felt it was important to provide readers with Beckford’s perspective about her work and activism since part of what I believe Beckford is doing is using fashion to become an agent in her own story and producing her own legacy.

Beckford’s personal history with fashion goes back to her time in law school. During her tenure as a law student, she supported herself by designing jewelry, t-shirts, and handmade jeans. Although she ended up working as an entertainment lawyer for 15 years, Beckford makes clear that doing fashion work was not a drastic career shift for her because she always had a “passion for fashion” (Beckford 2017). In 2009, Beckford spent time in Ghana, West Africa producing the Ghana International Music Festival. During that time, she was also traveling back and forth from Ghana to Brooklyn, New York City to be at her ailing mother’s bedside. During her mother’s final days, she affirmed Beckford’s desire to pursue fashion. With her late mother’s blessing and a desire to design clothing for masculine-identified women, Beckford decided to launch her clothing company Jag and Co. Clothier in 2013 (Beckford 2017).

Jag and Co. Clothiers is a custom-design suiting company sold on the Jag and Co. website and promoted on their Instagram account. The clothing company was even featured at DapperQ’s 2015 fashion show. When Beckford wanted to showcase her designs and celebrate the talents of LGBTQ+ fashion workers, she created RFW, an 8-day event that merges the art of fashion with social justice. Beckford has two distinct missions for RFW. Her first mission is to explore what she calls “the art of fashion, film, art, and technology,” meaning the pre-production processes and backstage elements that audience members do not have insight to, such as hair styling, make-up application, and lighting (Beckford 2017). RFW 2016 included several themed fashion shows such as a hair show, drag show performance, a body art and modification exhibit, celebrity stylist showcase, and a sneaker design competition. Each event also features fashion workers that represent the various demographics of the LGBTQ+ community. Beckford believes that fashion aesthetics are just as important as the messages they produce, she also does not shy away from addressing societal issues in her fashion shows.

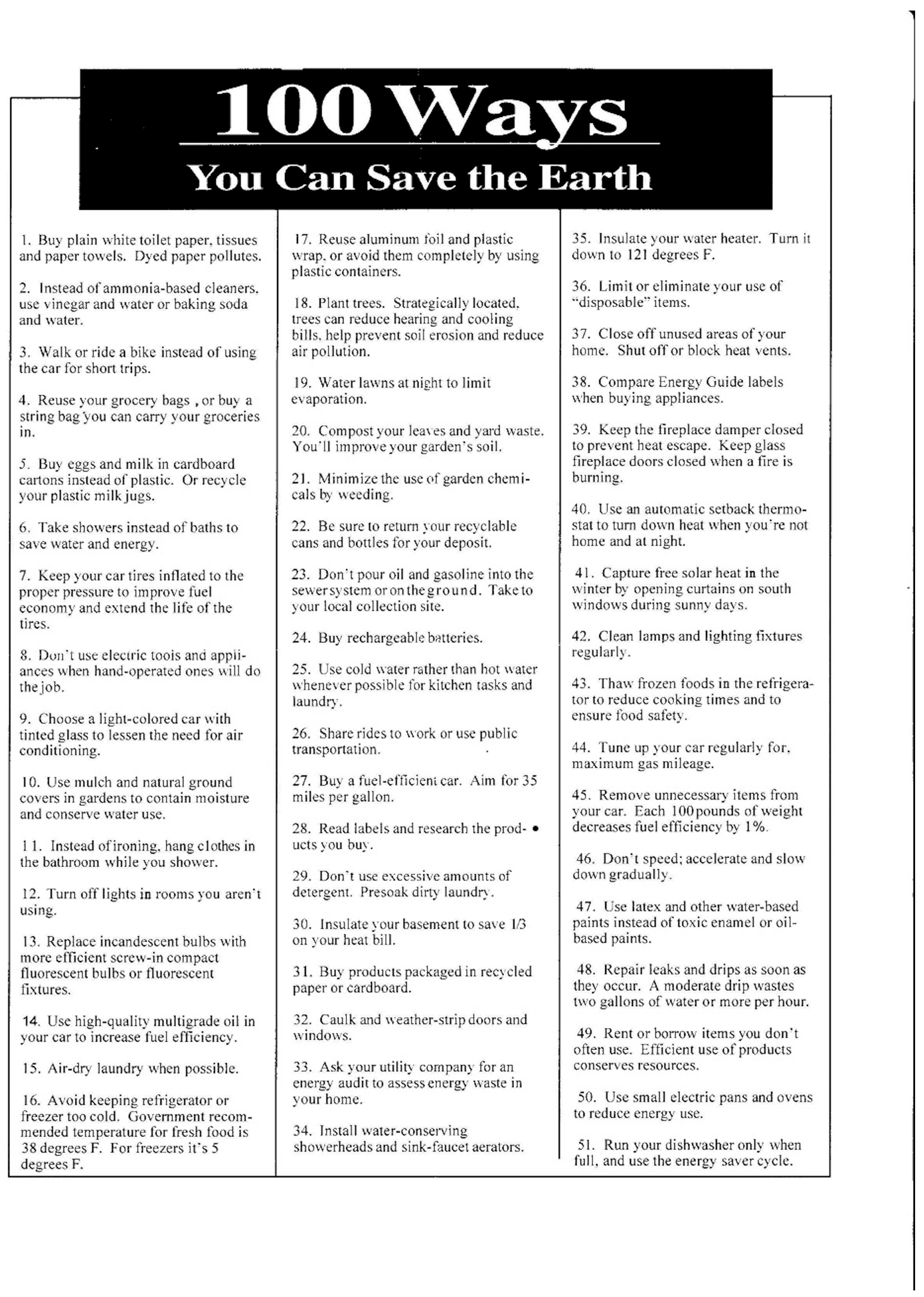

The second mission of RFW is to bring awareness to social issues. Beckford requires that each event include an artistic public service announcement such as a spoken word or interpretive dance performance that brings awareness to topics such as LGBTQ+ youth homelessness, elder isolation, and environmental pollution. For example, the event, Urban Knights Dumpster Diving, marked the beginning of a new mission for RFW, which is to create a carbon neutral fashion week. The purpose of Dumpster Diving was to contribute to environmental justice stakeholders’ mission to lessen the negative impact the textile industry has on the global water system. A group of health and mental wellness professionals that Beckford named The Metamorphic Corner delivered a spoken word performance about protecting our environment. They then used a handout given to patrons called “100 Ways You Can Save The Earth” to assist them in explaining the myriad ways the audience could conserve energy (see Appendix B). Even when people are resistant to her social justice imperative, Beckford explains that she recalls moments when a teen from the “scene” follows up with her after the show to learn more about the resources at a homeless shelter, and she feels affirmed in her mission. Being of service to a small group of people, or even one person drives her fashion work (Beckford 2017).

The primary location for RFW was the Caelum Gallery. Only two events took place at a different venue including Inside the Celebrity Closet which took place at a supper club, and an event called DragStars which was held in a speakeasy within a pizza parlor. The fashion workers used a similar set up for all the shows that took place at Caelum Gallery. Partial walls served as partitions that divided the room into three separate areas. Walking through each section was akin to walking through a wide doorway. The runway platform was set up in the back of the gallery where only about 40 chairs were positioned on the opposite side of the DJ booth. The runway platform was a T-shape painted piece of wood placed in the area with the sitting audience members. The other side of the sitting area was mostly standing room where people would form a pathway for the fashion workers to walk during each show. Fashion workers who were modeling the clothing walked down the runway, stepped up on the platform, and posed for the photographers positioned at the end of the runway.

During my interview with Beckford, I asked her a few questions about how she financed the show. She spoke candidly about the number of strategies she employs to secure funding and even the struggles she faces in funding the event. She explains that she funds much of RFW out-of-pocket, sometimes using the money she makes from legal consultation to invest back into the show. Sometimes the equipment or spaces are donated or given to her at a discounted rate because the owners are impressed with the vision and mission of the production (Beckford 2017). The beverage company, Myx Moscato, and a local jewelry company were in-kind donors at the 2016 event.

Beckford promotes cooperative economics as a strategy for securing resources. She understands that working within one’s community is a critical step in not only pulling the show together on a shoe-string budget, but it also allows those communities to be agents in creating the vision. Beckford also teaches younger producers how to navigate the process of garnering investors and sponsorships when an event is not well known. She explains that sometimes sponsors are not willing to sponsor 100% of the event so the producers have to break down the total asking amount into small parts to secure funding, or ask for resources from multiple people to meet their financial goals (Beckford 2017).

Finally, Beckford tries to be inclusive and accessible at every level of production including pre-production, fashion workers recruitment, and the show itself. For example, Beckford uses social media to recruit many of the fashion workers in RFW. She states that the fashion workers she recruits are talented individuals who work tirelessly to perfect their craft (Beckford 2017). However, many of these individuals lack the social and cultural resources to advance in the fashion industry.

Furthermore, these fashion workers may be marginalized in mainstream fashion institutions because their physical features are not palatable to mainstream audiences. For example, an aspiring plus size fashion worker in Beckford’s show may have been rejected from walking in a mainstream designer’s runway show because they do not have the “Coke bottle frame” or proportionate curves that are deem appealing by mainstream fashion stakeholders. In this case, even if a casting agent wants to perform inclusivity by recruiting a plus size fashion worker, their body remains outside of what the casting agent thinks the dominant culture deems attractive. It is often the too muchness of queer bodies—the too urban, too masculine, too fat—that prevents them from accessing the industry.

Beckford primarily uses Instagram to connect with people from all over the world who end up working with the production. For example, Beckford used Instagram to recruit gender-neutral fashion worker Petr Nitka to walk in the 2017 show. Prior to the 2017 show, Nitka connected with Beckford via direct message on Instagram expressing interest in the show. Compelled by her story, Beckford promised Nitka that if she could purchase her plane ticket from the Czech Republic to the United States, she would provide her with housing. Beckford kept her promise and ensured that Nitka had a housing arrangement and was also safely transported from the airport to her housing accommodation (Beckford 2017).

For Beckford, fashion shows can do more than impose specific standards of beauty and fashion on their audience; they can be counter-spaces where LGBTQ+ communities engage in social justice activism. Her articulation of BlaQueer Style operates as a form of knowledge production that teaches communities how to disidentify with corporate models of fashion production and lean on their communities to secure resources. Finally, she demonstrates that the emancipatory potential of LGBTQ+ fashion shows lies not in its ability to make queer fashion legible in the mainstream fashion industry, but instead it illustrates how marginalized communities can be led to work on and against dominant culture to author their style politics and serve their interests and needs.

2.2. DapperQ Presents: iD Origins

This overview of DapperQ includes a background and description of DapperQ the blog, its founder, Anita Dolce Vita, past fashion shows and iD. I primarily rely on blog posts, articles, videos and my own field notes and recordings to document how Vita presents her mission and vision online and how that translates into the fashion shows she has produced over the years. While I did not have the opportunity to interview Vita, the consistency in which she articulated her vision and mission for the blog and fashion show was substantial.

Nonprofit executive Susan Herr founded DapperQ in 2009. The style website is considered one of the leading “queer style” websites for “masculine presenting women, gender queers, and trans-identified individuals” (DapperQ Team n.d.a). The website features editorials and styling tutorials for dapper dress. As of 2025, the site garners over 100,000 social media followers, 90,000 unique page views per month, 1 million average unique views per year, 500–3000 average attendance, and media coverage in mainstream publications such as The New York Times and The Washington Post (DapperQ Team n.d.b). In 2014, DapperQ became a multiplatform network that now includes the style website, a large social media following, an annual public fashion show hosted in partnership with the Brooklyn Museum in New York City, and a 2023 book called DapperQ Style: Ungendering Fashion. DapperQ also demonstrates the domestic and international reach of “queer style” by reproducing the fashion show at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, Massachusetts and Montreal Fashion and Design Festival in Québec, Canada. Its large social media following in addition to the annual transnational fashion show indicate that in expanding queer style across digital and physical platforms, they increase the level of access people in marginalized communities have to this movement.

Some of the earlier representations on DapperQ depict “queer style” and dapper styles through a narrow lens of white gender and sexual non-conformity. Many of the fashion workers featured on the site were white, queer, non-disabled, young, cisgender women or transgender men. Once self-identified Black lesbian femme Anita Dolce Vita acquired the site from Herr in 2013, DapperQ evolved from being single platform project, to a multiplatform movement dedicated to exploring dapper style and “queer style” at the intersections of race, class, gender, and culture.

Unlike Beckford who transitioned from working as an attorney and entertainment executive to a fulltime fashion worker, Vita has written that she is a fulltime research nurse, who spends the time outside of her nursing job working as fashion blogger and author. She has written for publications such as The New York Times, Huffington Post, and Refinery29 and published the aforementioned book in 2023. Her goal is to create both digital and physical platforms for queer people to present and construct their style politics. One of the guiding principles in her fashion work is to promote racial diversity within the queer style movement by showcasing the work of people of color, mainly Black, Asian, and Latine individuals. Vita has written that white LGBTQ+ people have more opportunities to be queer style influencers than their queer of color counterparts (Vita 2016b). During a panel with digital media company Refinery29, Vita says that even in her best attempts to represent all bodies on DapperQ and its accompanying social media platforms, when she posts a picture on Instagram with a person who is “queer” yet white and conventionally beautiful (i.e., young/youthful, symmetrical facial features, thin, no visible disabilities), the picture receives more “likes” than people she posts who do not adhere to those beauty standards (Bernard 2015). She remarks “I’m sitting on the other side of that, as a black femme lesbian, and I’m like—it pains me, because I know exactly what’s going on” (Bernard 2015). While marginalized groups use digital technologies to create their representations and discourse outsides of the hegemonic gaze, technocultural scholar Miriam Sweeney reminds us that these spaces operate in ways that reinforce racism, sizeism, and ableism (Sweeney 2016). Examining how LGBTQ+ communities perpetuate racism and classism in digital spaces propels Vita to leverage fashion to create change as opposed to waiting for the fashion industry or the queer community to shift its ideologies (Bernard 2015).

On 6 December 2014, DapperQ partnered with the Brooklyn Museum to host its first show, un(Heeled): A Fashion Show for the Unconventionally Masculine. Target™ sponsored the show as a part of its Target First Saturday initiative, which provides patrons access to free and family-friendly events at the museum each Saturday. Continuing the success of the first show, on 17 September 2015, during New York Fashion Week, DapperQ along with the collective bklyn boihood, Posture Magazine, and DYDH Productions formed a partnership and hosted the VERGE Queer Fashion Show. According to DapperQ, VERGE participants both analyzed and celebrated how LBGTQ+ communities use art and visual activism for social change (DapperQ Team 2015). Members of bklyn boihood, DapperQ, and historian Tanisha C. Ford participated in a panel about the politics of queer style (DapperQ Team 2015). DapperQ also hosted the third annual fashion show, DapperQ Presents: iD at the Brooklyn Museum on 8 September 2016. The most recent fashion show took place at the Brooklyn Museum on 11 September 2025. It is also important to note that DapperQ promoted R/Evolution as “NYFW’s (New York Fashion Week’s) largest LGBTQ runway show” (Vita 2017). DapperQ has in some ways started to associate more with mainstream fashion institutions than it did in previous years, which has implications for who is allowed to participate in future events.

Vita uses social media and the website as promotional tools to garner interest in the fashion show and the website. Digital technologies also allow Vita and the DapperQ team to make the fashion show accessible to her audience and other fashion workers in the show. In preparation for the 2016 show, DapperQ announced that it would be facilitating digital casting calls to allow people from all over the world to audition (DapperQ Team 2017). While this does not entirely alleviate the financial and physical burden of fashion workers traveling to the show, and that means that financially stable fashion workers will have greater access to the event (especially since the position is unpaid), it does illustrate how Vita practices an ethic of care by ensuring that as many people as possible can participate in the show. The third annual event was also streamed live on Facebook via Huffington Post. The streaming allowed thousands of viewers who were unable to see the event in person to view the show.

Each annual fashion show is a one-night runway show that attracts more than 1000 patrons to the Brooklyn Museum. The shows typically feature between six to eight “queer style” clothing companies. These fashion workers’ designs are rooted in gender non-conformity and acknowledges that gender non-conformity lies at the nexus of race, ethnicity, and culture (DapperQ Team 2015). The 2016 show, iD, began with a happy hour where guests could walk around the perimeter of the large mezzanine of the museum and browse or purchase clothing and accessories from the various “pop up shops” with both the clothing brands featured in the show and other queer style vendors. Once the happy hour ended, the show began with a host introducing the event and paying tribute to the victims of the Pulse nightclub shooting with a moment of silence.

The fashion show was one continuous runway performance; there were no interludes or announcements. There was an elevated platform in the middle of the room and projector at the top of the runway with a slide listing the names of the fashion workers who designed the clothing. As they transitioned between collections, each company’s name would enlarge on the screen, and then they would transition to that clothing company’s runway show and music. The show featured over 60 fashion workers of various races, sexualities, genders, abilities, and body sizes.

Even though DapperQ has received a great amount of attention from mainstream fashion media including a feature by Vita in the HBO documentary Suited, Vita, along with the DapperQ team, work across digital and physical platforms to illustrate that queer fashion and social justice are not merely “on trend” or only significant when mainstream media chooses to pay attention. Vita recognizes the importance of decentering the white cisgender gay male gaze and bring to the center people at the margins who want to construct their definitions of beauty and fashion. As I will explore further in this article, this decentering of whiteness does important work culturally to represent queer fashion in a more inclusive way. Moreover, her disruption to the status quo has the potential to reframe the oppressive political ideas that inform the structures and systems that make these communities vulnerable.

In the sections that follow, I provide an overview of my interpretive framework, BlaQueer Style. I describe the origins of the term BlaQueer and outline why the term BlaQueer Style best captures the type of aesthetics—the styles and styling practices, clothing designs, and performances and the politics—the principles and ethics that inform the productions, that I was seeing in both fashion shows. I then move on to an analysis of the RFW and iD respectively. In my discussion of each fashion show, I include several smaller discussions of my findings. I argue that Beckford and Vita’s work to center Black queer and trans people is articulation of BlaQueer Style because they disrupt the Euro-centric, heteronormative, and cisgender status quo embedded in both mainstream and queer fashion spaces. I also examine various performances in these shows as expressions of BlaQueer Style because of the way they function to disrupt, call attention to, or correct the misnaming, misrepresentation, and the material violence that Black queer and trans people experience. I am interested in these acts of resistance as they stand, but also for what they mean in shaping political ideas that inform structures and systems that Black queer and trans people face.

3. Interpretive Framework

BlaQueer Style’s Origins and Theoretical Underpinnings

I came across the hashtag #BlaQueer on social media during the development of this project. In searching the media connected to the hashtag, I came across a blog post written by legal scholar Anansi Wilson, who is cited as Tabias Wilson in the references, who wrote that BlaQueer was a term they used to expand on the concept of intersectionality, a Black feminist framework coined by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw (T. Wilson n.d.). Their goal was to emphasize the liminality of being both a Black queer person. When trying to describe the type of activism that I was seeing in the fashion shows I was studying, I found terms like “queer style” or “Black style” while at times inclusive of queer Black people, tended to center whiteness, heteronormativity, and cisgenderism. Additionally, I wanted to develop a term that was not only about style of dress or descriptions of the aesthetics found in these productions, but inclusive of the politics and practices that also make them sites of activism.

BlaQueer became useful in developing this interpretive framework because it challenges users to resist the urge to parse out the myriad identities that make Black queer people who they are. Stylistically, the way the “Q” in BlaQueer replaces the sound of the “ck” removed from the word “Black,” illustrates that black and queerness are inseparable. The formality brought on by the capitalization of both “B” and “Q” highlighted that black and queer are equality important, even in moments when Black queer people are asked to choose what aspect of their identity is more salient. While not expressly written in Wilson’s blog post, I also drew connections between BlaQueer and Performance Studies scholar E. Patrick Johnson’s term “quare.” Quare is a term Johnson derived after hearing his grandmother pronounce the word “queer” with her southern dialect (Johnson 2005). Quare does similar and important work to center Black queerness however, my use of BlaQueer is in part my commitment to use the language that came out of the online spaces and communities that I was examining in this study.

BlaQueer Style is a trickster of sorts, shape shifting to name both the aesthetics and the politics of Black queer women’s fashion work. There is a level of “undecidability” and refusal that makes this interpretive framework useful for understanding the myriad styles of dress, as well as the liberatory politics that make these fashion shows sites of activism.4 Most importantly, it imagines Black queer women’s (cis and trans) cultural work within its purview. In my experience, Black lesbian feminist thought has often been the theoretical backdrop to explore “queer” styles, performances, and aesthetics but very few have centered Black queer women’s cultural work. Brittney C. Cooper argues it best in her essay “Love No Limit: Towards a Black Feminist Future (In Theory)” when she writes that Black feminist thought has been revered as a theoretical foundation and intervention that make queer theories possible; however, it is often relegated to an outdated mode for theorizing contemporary queer identities and performance (Cooper 2015). Cooper argues that in the process of operationalizing Black feminism as the building blocks of contemporary queer theory, scholars have often participated in the erasure of the Black women (cis and trans) for which Black feminist seeks to make visible (Cooper 2015).

As a scholar committed to the sustained growth of Black feminist thought, I present BlaQueer Style as a Black feminist interpretive framework for defining and theorizing the aesthetics and activism in Black queer women’s fashion shows. Much of what I uncover and argue is that BlaQueer Style is the work Black queer women do to engage in activism, specifically a Black feminist project of resisting Black queer and trans people’s erasure, misrepresentation, and surveillance at some of the most repressive times in our global history.

Cultural Critic bell hooks’ and Performance Studies scholar Marlon M. Bailey’s theorizations of visual art and Black performance respectively provide language to articulate how BlaQueer Style is used throughout my analysis to describe both the aesthetic qualities and the politics that inform the activism in these two fashion shows. hooks’ definition of “visual politics” makes clear that we can concern ourselves with how “race, gender, and class shape art practices,” without “abandoning a fierce commitment to aesthetics” (hooks 1995, p. xii). In Marlon M. Bailey’s work on ballroom culture, he argues that producers undertake the cultural labor of performance “both to fortify their community and to withstand the difficult conditions under which they live” (Bailey 2013, p. 143). Taken together, BlaQueer Style as informed by hooks’ notion of visual politics then is how race, gender, class, and sexuality shape styling and fashion in these fashion shows. Moreover, Bailey’s theorization of ballroom culture, make possible the notion that BlaQueer Style is Black queer women’s construction of fashion shows as intentional spaces where misrepresentation, erasure, and other forms of violence can be disrupted.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. BlaQueer Style Is…Bringing the Margins to Center

4.1.1. Hair du Soleil

Beckford articulates BlaQueer Style in the hair show she produces, Hair du Soleil, by centering Black people and Black expressive culture. Hair shows started in the mid-20th century and rose in popularity during the 1980s. They evolved into competitions or “avant-garde weave battles,” that featured extravagant hairstyles and designs (Byrd and Tharps 2001, p. 117; Hazelwood 2010). Johanna Lenander writes that creating “fantasy hair” “is a hobby of predominantly African-American professional hairstylists” (Lenander 2007, p. 1). Additionally, Black gay men, Black women, and working-class Black people are the primary hair show attendees, participants, and producers, illustrating that hair shows are not simply an articulation of Black culture, but of a queer Black culture that refuses erasure.

Hair du Soleil featured many elements of Black expressive culture including the avant-garde weaving showcases; the fashion workers stylized runway struts to house, pop, and hip-hop music; and the call and response between audience and host. At the beginning of the show, the fashion workers walked down the runway with simple hairstyles such as a straight blonde wig, bald hairstyle, or ponytails with extensions. These sleek hairstyles helped to draw attention to the extravagant evening gowns and leotards the fashion workers wore. Towards the middle of the show, the hair show began. Fashion workers with extravagant, bold hairpieces walked down the runway to the sounds of house, pop, and hip-hop music. A fashion worker with a Skittle candy bag printed dress, trimmed with actual Skittles candy struts down the runway, twirling while trying to hold the headpiece in place. The audience “oohs” and “aahs” in amazement with the design. The fashion worker’s hair is styled as a huge rainbow piece placed on top of clouds that were made of white cotton balls. The fashion worker who styled this headpiece created each ring of the rainbow with Skittles candy and designed the top layer of the rainbow with hot pink hair extensions. The fashion worker completed the hairstyle with a bow made of Skittles candy wrappers.

Beckford articulates BlaQueer Style in her fashion shows by centering and reclaiming elements of Black expressive culture that are often marginalized or appropriated with Euro-centric queer spaces. The marginalization and appropriation of Black culture often result in the intentional and unintentional erasure of the very Black queer people who create these cultures. This erasure is not just important to highlight at the cultural level; it also has structural implications for Black queer people. It is in “queer spaces” where activism emerges or grows. When Black queer people are outside of the purview of queer culture and activism, their issues and their concerns about the oppressive structures they navigate run the risk of falling out of consideration. By engaging in BlaQueer Style through her centering of Black expressive culture and Black people in Hair du Soleil, Beckford is presenting not only a subversive way of doing fashion work, but also a way of doing activism that is inclusive of people that find themselves on the margins of dominant culture as well as within LGBTQ+ communities.

Another example of an unintentional articulation of BlaQueer Style that served to center those who were invisible in the space occurred when the fashion workers engaged in improvisation during parts of Hair du Soleil. When events start late, the host of these productions will do everything from signifyin’, to singing, to storytelling to keep the audience engaged as they wait for the “real” performance.5 For example, when the host Bianca Golden from the ninth cycle (season) of the modeling contest America’s Next Top Model, tried to stall during an intermission, her improvisational strategy unintentionally highlighted the erasure of Deaf people and by extension people with disabilities within LGBTQ+ communities.

During this intermission, the fashion workers who were designing and modeling the clothing were taking longer than expected to start the next showcase. After sensing the restlessness in the audience, Golden jumps up as if a light bulb went off in her head. She then asks a fashion worker who is deaf to come out from backstage. As the fashion worker stood next to her, she explains that they taught her how to sign “I Love You.”6 She then proceeds to follow the fashion worker as they signed the words “I Love You” together. While this moment could have easily been dismissed as filler or read as a performance that tokenizes Deaf people, I chose to see it as an articulation of BlaQueer Style because it signals ableism and audism (the notion that hearing people are superior) in many cultural and activist spaces.

Golden’s improvisation is also an expression of BlaQueer Style because it pushed me to interrogate my own mappings of queerness on to certain bodies and not others when theorizing the liberatory potential of Black queer women’s activism within their fashion work. When I saw this fashion worker at previous RFW events, I assumed they might identify solely as LGBTQ+. The fashion worker was also someone I perceived as a person of color, so I was reading queerness as a product of their race or ethnicity. I did not immediately consider how Deaf people could be read as “queer,” because they disrupt Western notions of productivity and normativity (Kafer 2013). While I do recognize that people in the Deaf community may not necessarily view their deafness as a disability or may not identify as queer, employing queer as an analytic signals how Deaf people become disruptions in audio-centric societies where hearing is the norm (Kafer 2013).7 When Golden asked the fashion worker to help her sign, “I Love You,” I remember being shocked to learn they were deaf. At the time, I still read queerness as something that is legible. In other words, I was praising the show about the diverse demographic it brought together without interrogating how difference as something visible erases how queerness can also be illegible.

In the same way that we expect to see difference, we also conceptualize disability as something physical or something we would be able to tell by looking at a person rather than a system of power that is socially and culturally constructed (Thomson 2014). That moment demonstrates that we must think about queerness, difference, and inequality as not always a visible characteristic or a barrier that is readily knowable. As I stated in my earlier discussion of Hair du Soleil, there are structural implications to erasures that happen at the cultural level. There is violence in only seeing what disrupts the norm and using that to inform the freedom we work toward in our activism. It means that we miss some of the critical ways that people are harmed within our systems and even in our attempts at advocacy. This disruption continued at the event PhotoViews as fashion workers brought attention to the way Black queer and trans bodies are disciplined through the dominant gaze.

4.1.2. PhotoViews

During the event called, PhotoViews fashion workers engaged in an expression of BlaQueer Style by using their bodies and performances to reveal disciplinary codes imposed on them. One aspect of the show included fashion workers posing in a larger-than-life picture frame. The fashion workers who created the event placed two large gold picture frames in the corner of the standing room area with a white box where the fashion workers who were modeling would sit. During the cocktail hour and intermissions, spectators could walk up to the fashion workers in the frames and take pictures. Some of the fashion workers’ tattooed bodies served as the “art” on display in this New York gallery. For example, one of the fashion workers displayed their full chest piece tattoo and a partial thigh sleeve tattoo while posing in the frame. Some of the fashion workers had their faces painted to look like lions, tigers, and leopards evoking an image of a caged animal. The metaphor of the caged animal is amplified as a fashion worker with a burnt orange evening gown poses with their face painted like a tiger inside of the frame.

The performance art piece allowed audience members to participate in the artistic production by taking the fashion workers’ picture. Whereas photographers might direct a model by telling them how to pose, and even the casual spectator might instruct the model; each fashion worker controlled what spectators photographed. If they changed positions, the audience members waited until they were not moving. If they decided to direct their gaze at another audience member, another person wanting a photo either had to take the picture as-is or wait until the fashion worker acknowledged them. While it is true they may have been instructed to shift poses periodically, they controlled when and how those changes occurred.

The fashion workers evoke BlaQueer Style in PhotoViews by blurring the lines between subject and object. Much of visual culture centers the gaze and therefore the perspective of the person capturing an image. The fashion workers’ refusal to be disciplined by the conventional standards of fashion photography—where the photographer controls the outcome of the image—restructures the relationship between audience member and fashion worker even if momentarily. Instead of controlling how and when the image is taken by the audience member, the fashion workers illuminate the transient nature of agency in this interaction. This performance signals what is possible when Black queer people control their representations.

I liken the articulation of BlaQueer Style here to Fleetwood’s concept of excess flesh in that it does not necessarily “destabilize the dominant gaze or its system of visibility. Instead, it refracts back on itself” (Fleetwood 2011, p. 112). In other words, rather than undoing the dominant gaze, the fashion workers signal the photography conventions that ascribe meaning and work to discipline their bodies. The disciplining is not only in the act of gazing, but it is in what meaning those gazes produce and how they inform the systems and structure that Black queer and trans people navigate. This refraction or changing the direction of subject and object in the production of the image does more than momentarily give the fashion workers agency to construct their representation, it has the potential to bring awareness to how political ideas and outcomes are shaped by who controls the production of the representation. By controlling their representations, Black queer and trans people are participating in a form of labor that could transform their material lives. We also see this labor to reshape political ideas about Black queer and trans people happening when fashion workers use performance to engage in self-definition and as a means of creating safe spaces for themselves and other people in their communities who are forgotten on the margins of society.

4.1.3. DragStars

Beckford and the fashion workers performing as drag queens in DragStars engage in an expression of BlaQueer Style by creating safe spaces for Black queer and trans people to engage in self-definition and storytelling to affirm their communities, correct their misnamings and mark their histories. DragStars was a new addition to the lineup of shows at RFW. The event took place in a speakeasy behind the wall of a pizza parlor. Beckford’s choice in venue signaled her evocation of BlaQueer Style because she created what Sociologist Patricia Hill Collins terms “safe spaces,” what Bailey calls “Black queer spaces” and what literary scholar, Sharon P. Holland defines as “home.” Creating “safe spaces” has a long history in Black women’s political organizing and activism. Collin’s points out that “safe spaces” were the places where Black women could concentrate on the issues that mattered to them (Collins 2008). Bailey argues that creating “Black queer spaces” are “place-making practices that Black LGBTQ people undertake to affirm their non-normative sexual identities, embodiment, and community practices and values” (Bailey 2013, p. 146). Holland describes “home” in several ways including a practice within black queer/quare studies to provide a “place of refuge and escape” (Holland 2012, p. xii). The speakeasy behind the wall also references historical articulations of Black queer space. Speakeasies, particularly during the Harlem Renaissance era, functioned as counter-spaces where Black, gay and lesbian subcultures, and working-class people would fellowship outside of the dominant gaze, and circumvent laws prohibiting homosexuality and alcohol use (J. F. Wilson 2010). Together these frameworks provide a language for reading the drag show as an articulation of BlaQueer Style, an event that facilitates the construction of spaces of refuge where Black queer and trans people can affirm their identities and address issues that concern them.

Beckford’s expression of BlaQueer Style can also be seen in the principles that drove the transformation of the spatial elements and the community practices that shaped the event. For example, even though there was no runway platform, there would always be a runway formed by the bodies of the patrons who stood or sat at either side of the room. The use of space also signaled an expression of BlaQueer Style in that it primarily functions to highlight the Black queer and trans fashion workers. During each performance, the fashion workers figuratively “worked” each table, at times leaning down to shimmy their chest over the small coffee tables full of drinks. Once the fashion workers circled the perimeter of the space, they made their way back to the middle of the “stage” to continue singing, or to close out the performance.

An example of the community practices that informed the event was the disruption of conventional time to center the cultural norms of Black queer and trans people. I arrived early to venue so that I did not miss the performances. As I was searching for the entrance to the performance space, Beckford stops her conversation and says, “it’s behind that door, they not ready yet.” After waiting nearly 45 minutes, we were finally ready to start the show. The late start is important to point out because it signals a connection between DragStars—an extension of ballroom culture and the cultural practices of Black queer and trans people within ballroom culture. In Bailey’s study of ballroom culture in Detroit, he notes that the shows did not begin until the commentators arrived sometimes up to two hours after the audience arrived (Bailey 2013). I found this significant because it highlights a deliberate choice by the fashion workers at DragStars and to some degree the audience to accept this queering of conventional time.

It may also be that starting an event late is a part of the fashion workers’ performance of diva “realness.” In the same study, Bailey argues that “to be ‘real’ is to eliminate or minimize signs of deviation from gender or sexual norms that are dominant in heteronormative society” (Bailey 2013, p. 58). Arriving “fashionably late” is an accepted behavior for “divas” in the mainstream fashion and entertainment industry. Therefore, the tardiness is perhaps both an articulation of “realness” and a critique of the erasure of Black queer and trans people whose styles and practices have been appropriated in the mainstream fashion and entertainment industry. Whether the lateness was a performance of realness or a disruption of conventional time, this articulation of BlaQueer Style centered the cultural norms and practices of Black queer and trans communities.

The last example of cultural practices that shaped this event and signaled Beckford’s articulation of BlaQueer Style was the unspoken gratuity policy. As the fashion workers performed, spectators rushed to the middle of the dance floor to tuck dollar bills into their exposed cleavage or to place the dollar bills into their hand as if they were giving the fashion worker a handshake. While the stronger performances appeared to produce larger cash tips, the audience seemed to understand the cultural expectation that even if the performance was not particularly good, tipping was mandatory. Tipping is an important practice of gratitude, but it also helps to enhance the material conditions of Black queer and trans fashion workers. Many of them are working for little to no money, and tipping is a cultural practice that not only supports their talent, but it also supports their livelihood.

Beyond the cultural practices that shaped DragStars, the fashion workers’ lip-syncing performances were also articulations of BlaQueer Style in that they signal their labor to engage in self-definition. Each fashion worker performed songs by iconic and contemporary Black cisgender female artists such as Whitney Houston, Beyoncé, Destiny’s Child, Kelly Rowland, Lil Kim, Trina, Tamar Braxton, and Rihanna. These performances were very specific articulations of Black R&B, pop, and hip-hop “divas.” Bailey argues that unlike depictions in Paris Is Burning, Black drag performers (male-to-female, MTF) have “exclusively emphasized Black women singers rather than White women” (Bailey 2013, p. 132). Drag shows draw on elements of Black femininity and Black popular culture. The fashion worker’s effectiveness is determined by her ability to emulate known Black women entertainers through physical appearance, comportment, and facial expressions (Bailey 2013). Reading drag performances as merely gender and sexual subversion would displace race and racialization as tools of analysis in Black queer cultural production and resistance work.

One fashion worker’s performance of pop singer Rihanna’s song “Work” became the most emphatic expressions of BlaQueer Style, as it blurred the boundary between audience and fashion worker. “Work” was one of the most popular songs of the summer of 2016. Every time the song came on at the other events, it created an infectious energy where people would immediately dance, sing, and sway along to the music. The performing fashion worker dressed in a black long sleeve see-through leotard that was worn with fishnet tights and rhinestone encrusted thigh-high platforms boots exuded Black diva glam.8 She wore a rather large gold neck collar above the leotard, and a short, tapered cut wig. Finally, her thick black and gold belt was tightened to accentuate her curvy figure.

The fashion worker begins the performance standing with her back toward the audience on a stage in the corner where the step and repeat was positioned. The crumpled dollar bills lying on the floor and even the gold microphone stand standing in as a “stripper pole” creates a quintessential scene of many exotic dance performances, setting the tone for her sultry performance. The performance begins with the pulsating dancehall instrumentals of “Work.” The fashion worker starts winding her hips slowly to the sensual rhythm as the crowd bursts into cheers encouraging her as she literally “works” the stage. The repetition of the command to “work” in the chorus borrows from Black gay vernacular. According to Bailey, “werk” in ballroom culture is a command “to give a grand or exceptional performance” (Bailey 2013, p. 254). Therefore, the repetition of “work” over a melodic dancehall beat conjures a queer African diasporic experience that connects the American Black gay and Caribbean culture. The command to werk also stands in as a command to the fashion worker to give the audience her best show. As she leaves the stage, she walks toward the middle continuing to wind her hips and bend down to shake her backside. She walks over to collect a tip but does not leave the area until she gives one of the audience members a seductive lap dance.

As she continues to perform in the middle of the floor, one of the audience members gets up from their seat, swaying and singing along to the song as they walk onto the middle of the dance floor holding their phone’s camera. The audience member continues to dance with the fashion worker while filming an almost 360-degree scan of her body, including her backside, with the phone. The audience member bends down and then backs up and walks around the fashion worker directing the camera’s gaze until they capture what seems to be the appropriate length of a video to post on social media. As the audience member documents the performance potentially to circulate online, they not only become a part of the performance, but they also become the performance for the other audience members in the room. They are no longer an audience member but perhaps a “fashion worker” who is allowed to create and change the course of the performance.

This moment of audience participation in DragStars also became an articulation of BlaQueer Style because it served to momentarily disrupt binaries like fashion worker/audience, simultaneously shifting and affirming both the fashion workers’ and audience members’ agency. The fashion workers would unapologetically pull the audience into the performance, blurring the lines between the object on “stage” and the subject in the audience. The fashion workers would even walk around giving lap dances to unsuspecting audience members, creating an entirely new layer to the performance. The fashion worker’s insistence on audience participation is an expression of BlaQueer Style that undercuts the notion that the fashion workers are the objects that are solely responsible for producing the entire experience for the subjects, the audience members. Like the fashion workers at PhotoViews, the fashion workers at DragStars are challenging the dominant gaze by signaling the transient nature of agency and pointing to the at times oppressive conventions of performance that discipline Black queer and trans people. By signaling these oppressive conventions of subject and object, they are disrupting the political ideologies that inform these very structures even if they do not dismantle them entirely. Disruptions and even changes to oppressive political ideologies can do so much to reshape the material conditions of Black queer and trans people.

The final articulations of BlaQueer Style that I will discuss in relation to RFW involves the various testimonials from Beckford, the host, and fashion workers during DragStars. I argue that these testimonies centered trans people and their stories in ways that disrupt their marginalization and or exclusion from both dominant society and LGBTQ+ communities. Testifyin’ is both a secular and religious form of storytelling in Black language and African diasporic religions (Smitherman 1997). While RFW was primarily a secular event, testifyin’ as a ritual of Black expressive culture made the drag show an articulation of BlaQueer Style that was just as sacred as it was profane (Stallings 2015). Testifyin’ is a mode of resistance that is less about recounting the past merely for others to know, but it is also a coping tool for marginalized communities to withstand the conditions of living in oppressive societies (The Combahee River Collective 1995).

During one of Beckford’s these testimonials, she revealed that her activism is trans-inclusive. Beckford centers transgender people, especially transgender people of color, as knowledge producers at RFW events to facilitate meaningful conversations about transitioning, trans identity, as well as the material acts of violence against trans people. For example, Beckford shares a story about how she started to recognize the importance of greater trans-inclusion in LGBTQ+ spaces. In 2014, she noticed that many of the fashion workers who modeled in her shows previously were starting to transition. She continues to share that 11 of those fashion workers identified as aggressives or masculine-of-center women and over time transitioned now identifying as transmen or male. Beckford explained that she centers trans issues in her showcase, Haus of Jag and Co. because she was finding out via social media that many of these fashion workers who modeled for her were transitioning but were doing so with “no conversation” about the process or the challenges they face. She claims that they usually have no one to talk to about the complexities of the experience. Therefore, the show became her way of producing a conversation about the joys, challenges, and violence associated with trans identity.

Another example of this centering of Black trans people and their stories, specifically, Black transwomen occurred at DragStars when Beckford honored the mother of a young 22-year-old Black transwoman who was brutally beaten and killed in New York City.9 In introducing the mother to the audience, the host, Sasha Fierce testifies about the devastation of losing children to transphobic violence. As she presents the mother to the audience, Sasha Fierce provides the following testimonial:

…and she let him know what it is, and he decided to beat her to death. Because he don’t want his manhood to be exposed or over, and now she lost her beautiful, talented, young, daughter of God. And I was with you to fight this case, and we ain’t win. We didn’t get justice. Even though the videotape told on him and he finally confessed, it still didn’t get justice the time that this man want to kill another human being. I have asked this mother to come tonight because we wanted to honor you and show you our appreciation. Even though this night is not going to cover and get Tina because I know how it feels to lose a child.10 June 29th will make five years of my son being gone, so I know how it feels to lose a child. And I’m letting you know that you’re not alone, you’ll never be alone, never, and Tina ain’t never went nowhere, you know what I mean. Thank you so much, everybody, give it up for this young lady’s mother, y’all.

Fierce’s somber testimony did not match the overall jovial demeanor she presented the entire night or general spirit of joy the event evoked. However, her speech became a time to momentarily suspend the glamorous and jovial essence of the event to grieve and heal. Fierce’s testimony illustrates that there are countless stories of transwomen and gender variant people of color never brought to justice in our legal system. Fierce’s speech underscores the interlocking nature of oppression and the ways that racism, sexism, transphobia, and classism manifest itself through the legal system. However, in the following moment when Fierce instructs the mother to take center stage, and the mother struts down the runway to Beyoncé’s song “Formation,” a song that evokes the aesthetics of Black liberation movements, we see that articulations of BlaQueer Style in the face of death are ways that Black queer and trans communities engage in resistance to state and vigilante violence. This moment along with the other intentional and unintentional acts of BlaQueer Style during the week mark a commitment to more than centering Black and queer trans people in the moment. These articulations signal and disrupt the broader oppressive ideologies or structures and have the potential to transform Black queer and trans people’s material conditions.

Beckford and the other fashion workers that produced RFW articulated BlaQueer Style because they worked to center the people and communities that are often left at the margins in dominant society and in LGBTQ+ communities. We also see BlaQueer Style expressed in the ways that the fashion workers blur the lines between subject and object to point to how their bodies are disciplined through the dominant gaze. Additionally, BlaQueer Style is the labor to produce safe spaces where Black queer and trans people are free to construct their identities, narratives, and histories. These acts of BlaQueer Style serve to challenge and even correct their misnamings, misrepresentations, and the historical record. As I stated earlier, what happens at the cultural level has political consequences for Black queer and trans people. BlaQueer Style a description of the aesthetic qualities of the fashion shows and the politics that signal, destabilize, and perhaps correct conventions in fashion. Fashion shows are a microcosm of society, meaning they reflect and produce the systems in society that continue to harm Black queer and trans people. Examining how people engage with fashion to disrupt these systems has the potential to benefit everyone including those who are most vulnerable in our society. Continuing this discussion, I turn to the articulations of BlaQueer Style by Anita Dolce Vita and the fashion workers involved in creating DapperQ’s annual fashion show, iD.

4.2. BlaQueer Style Is…Practicing Solidarity and Building Coalitions

4.2.1. Anita Dolce Vita and dapperQ

Vita articulates BlaQueer Style in her recruitment of fashion workers representing a range of ages, abilities, body sizes, gender identities and expressions, races, and cultures. Additionally, her insistence upon using a fashion show marketed as a queer fashion show to build coalitions with and stand in solidarity with the Movement for Black Lives is an expression of BlaQueer Style. Vita is intentional about including people with bigger bodies, disabled people, queer and trans people of color in the show. Her recruitment approach is an articulation of BlaQueer Style in that she thinks beyond queer as merely gender and sexual non-conformity to make legible the bodies that become queer through their inability to align with hegemonic beauty standards (Cohen 2009). The decision to position queer people as the art in cultural institutions like the Brooklyn Museum is a radical expression of BlaQueer Style in Vita’s fashion work. It disrupts the history of art museums that have historically excluded the artwork and bodies of women, people of color, and LGBTQ+ people. In addition to Vita’s articulations of BlaQueer Style, I also choose to read the moments in the show when both Black queer fashion workers and non-Black queer and trans fashion workers stand in solidarity with the Movement for Black Lives as BlaQueer Style. I do so to illustrate that BlaQueer Style is not only a set of aesthetics by Black queer people, but it is also a set of politics to build coalition among movements for social justice and to affirm Black queer and trans people.

Since the inception of DapperQ’s annual fashion show in 2014, Vita and the fashion workers working alongside her have incorporated runway performances centered on promoting social justice. More specifically, fashion workers have incorporated runway performances that show solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement. These performances illustrate that fashion is not only a byproduct of social movements but as historian Tanisha C. Ford argues, fashion and beauty served as the political strategy (Ford 2015). Vita states in an interview, “Queer fashion is not just a trend, but it is a lasting social movement and it’s a social movement that benefits everyone” (Brekke 2016). As a participant and leading force in the queer style social movement, Vita holds herself responsible for building a movement that does more than disrupt traditional codes of gender and sexuality in fashion. DapperQ’s consistent displays of solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement show that queer social movements should only focus on the marginalization of gender and sexual nonconforming people and ignore how multiple systems of domination compound to harm queer people that fall outside of the queer/straight dichotomy (Cohen 2009). Vita reveals through her fashion work that marginalized communities have an opportunity to leverage fashion to build coalitions that make social movements dynamic, intersectional and most importantly, transformational. Up until this point, I have analyzed the fashions shows that I attended in person. While I do provide an analysis of iD, the show I attended in 2016, I first would like to examine Vita’s earlier production to illustrate how her articulation of BlaQueer Style started long before that show.

4.2.2. (un)Heeled

Vita expresses BlaQueer Style in her first fashion show (un)Heeled, by creating a counter-narrative to the Killer Heels: The Art of the High-Heeled Shoe exhibit featured in the Brooklyn Museum that same year (Vita 2014).11 The show was also an opportunity for the fashion workers to engage in a discourse about the necessity of coalition building between the queer style movement and the movement for Black lives. Vita articulates a standpoint similar to Collins, who argues that for Black feminist thought to be fully actualized “it must be open to building coalitions with individuals engaged in similar social justice projects” (Collins 2008, p. 42). By connecting Black Lives Matter to the queer style movement, she engages in an expression of BlaQueer Style that draws attention to the myriad and interlocking systems of oppression that is harming all those positioned at the margins of society.

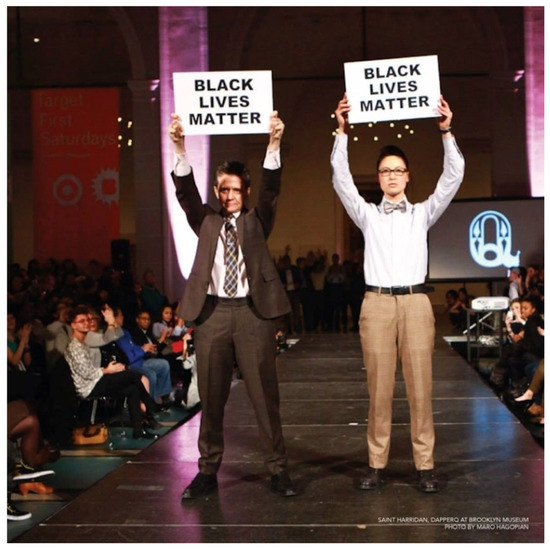

Two expressions of BlaQueer Style from (un)Heeled were the displays of solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement the fashion workers who designed one of the featured clothing lines and by Vita and her co-producers at the end of the show. The show took place on 6 December 2014, less than four months after the killing of Mike Brown, an unarmed Black teenage boy from Ferguson, Missouri who was shot by police officer Darren Wilson on 9 August 2014. The first moment occurred when founder and owner Mary Going, of clothing company Saint Harridan, used their segment of the show to articulate their solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement. Fashion workers of various races and abilities all dressed in suits, suspenders, bowties, and dress shoes, walked the runway holding white signs with the words “BLACK LIVES MATTER” printed on them with black lettering—affirming that Black humanity matters (see Figure 1). During their finale walk with one of the fashion workers, Going, a white masculine-of-center person, and another fashion worker posed at the end of the runway platform holding up the “BLACK LIVES MATTER” sign.

Figure 1.

Owner of Saint Harridan, Mary Going and model with BLM signs from Hagopian (2014).

During the show’s finale, the DapperQ organizers, including Vita, DapperQ founder Susan Herr, and one of the producers closed the show creating in physical form the #HandsUpDontShoot demonstration depicted in images circulating social media in response to Mike Brown’s death. Hundreds of members in the audience also participated in this act of protest by putting their #HandsUp as well (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(un)Heeled audience enacting #HandsUpDontShoot with producers from Prue (2014).

Political scientist Cathy Cohen warns queer activists that singular-oppression frameworks “limit the comprehensive and transformational character of queer politics” (Cohen 2009, p. 244). Vita, her team, and the fashion workers designing the clothing demonstrate that queer style as a social movement is responsible for building coalitions with and among other movements for social change. These movements and the activists who shape them are also responsible for developing strategies within those movements to address multiple layers of injustice. The fashion workers’ displays of solidarity is an articulation of BlaQueer Style in that it illustrates that fashion work can disrupt racialized and classed gender and sexual state and vigilante violence creating what Vita calls a “lasting social movement that benefits everyone” (Brekke 2016). This expression of BlaQueer Style continues with the third year of the show.

4.2.3. iD

iD, the third installment of the annual fashion show, presented two distinct expressions of BlaQueer Style. One smaller display of BlaQueer Style occurred toward the end of the show. A fashion worker modeling for Thomas Thomas, a London-based “women in menswear” fashion worker, posed at the end of the runway with their back toward the photographers raising a fist with the marking “BLM!!!” on the back of their hand that stood for Black Lives Matter (see Figure 3). This articulation of BlaQueer Style by non-Black queer and trans people points to the power of using one’s position of privilege to bring about social change for Black people. While this demonstration was performed by the fashion worker modeling the clothing, it shows how non-Black fashion workers, like the founder of Thomas Thomas, do not have to become “saviors” to engage in political activism for vulnerable Black queer and trans communities. Their advocacy can direct our attention to Black queer and trans people as they engage in self-determination and community transformation.

Figure 3.

Model posing with “BLM” mark on raised fist from Lemonte (2016a).

The second and what I argue is the most dynamic expression of BlaQueer Style from iD came from the fashion workers who designed the clothing brand Stuzo. As the first collection to grace the runway, Stuzo Clothing set the tone for the show by creating a multilayered experience that served to critique police brutality and the injustices toward Black queer and trans people. The clothing designs in their “X” collection, the fashion workers modeling the garments, the music used during their set, and the visual images they displayed as a part of the performance, worked together as the articulation of BlaQueer Style aesthetics and politics.

In 2010, Black queer fashion workers Stoney Michelli & Uzo Ejikeme founded Stuzo Clothing, a Los Angeles-based clothing company. Stuzo most emphatically aligns with the mission and message of Black Lives Matter to affirm “all Black Lives along the gender spectrum” with their “genderless” clothing designs that affirm Black identity and resistance (Black Lives Matter 2023; Stuzo Clothing n.d.a; Stuzo Clothing n.d.d). Ejikeme explains in an interview that the “X” collection is “something to uplift,” and represents the current political climate, what they “want to see happen in the future for people of color and for people in the queer community” (BK Live 2016). On Stuzo’s website, the owners state that the “X” Collection:

The collection includes handmade designs such as monochromatic black shirt- and-pant sets, black faux leather shirts, black and white geometrical patterns, reversible raincoats and bomber jackets some of which were mixed with accents of hot pink material. Various pieces from the collection become a part of Stuzo’s most aesthetic expression of BlaQueer Style. Many of the items in the collection have a name that relates to the theme of the collection.reflects a new generation that is disaffected by societies’ rules and standards of the way things “should” be. We rebel against brutality and injustices and create beauty despite the ugly. Enjoy!(Stuzo Clothing n.d.g)

The first item featured on the runway was a black faux leather shirt and pants set called REBEL X. On Stuzo’s website they include the description “start resistance with style in our faux leather REBEL X Shirt” (Stuzo Clothing n.d.e). TRANS II FORM is another piece featured in the runway show. This black zip-up t-shirt has the word “Trans” written in white letters on the front and the word “Form” on the back. The design appears to have a double meaning of transgender identity and transform. DEPROGRAM, is a long-sleeved black sweatshirt with matching sweatpants with the word DEPROGRAM written vertically down the arms of the sleeves, each leg of the pants, and across the bottom in the back and in the front of the shirt (see Figure 4). Another item in the X collection is a black t-shirt with the word REBUILD printed twice diagonally forming the figure “X.” The white letters of both words meet at the large letter U. Their description “Rebuild your world” signals that the large “U” in the middle is a call for “you”– marginalized people– to rebuild themselves as they are world-making (Stuzo Clothing n.d.f).

Figure 4.

Stuzo model wearing DEPROGRAM outfit from Lemonte (2016b).

Much of the apparel Stuzo designs is political and promotes the radical politics of unapologetic Blackness that informed the Black Lives Matter movement. While BlaQueer Style is what I argue represents their politics in designing this line, Stuzo quite literally evokes BlaQueer Style as an aesthetic—the styles and graphics on the clothing they designed. Genderless garments like “BLACK AF,” which stands for Black as Fuck, and “BLACK SINCE” drives Black customers to “Express [their] blackness with this exclusive tee”12 (Stuzo Clothing n.d.a; Stuzo Clothing n.d.b). HUMAN TEE, which suggests a play on the word humanity, is a simple message to “Be Human.” The black t-shirt includes a list of racial gender and sexual slurs used against Black people, queer people, and women. However, for Black queer women who wear the shirt, the list of words “NIGGA,” “NIGGER,” “COLORED,” “FAGGOT,” “BITCH,” and “HO,”13 crossed out demonstrate an articulation of BlaQueer Style because it highlights a refusal for Black queer people to accept their dehumanization (Stuzo Clothing n.d.c). Stuzo uses their design to articulate BlaQueer Style to affirm all Black lives in their runway show.

Stuzo engaged in an expression of BlaQueer Style by using queer fashion workers to walk the runway, the visuals meant to align with the movement for Black lives, and the sonic sensations of liberatory music. The cheers of the crowd created affective registers of love, affirmation, and solidarity expanding on Stuzo’s visions for liberation. Together, Stuzo produces a mix of sensations that worked to disrupt systematic oppression at the intersections of race, gender, and sexuality.

At the start of Stuzo’s set, the sounds of clapping and the voices of children chanting the prelude “All I want to say is that they don’t really care about us” fill the room moments before anyone appears on the runway. After a sharp cacophony of sounds, creating a chilling pause, the percussions to Michael Jackson’s song “They Don’t Care About Us,” continues and a fashion worker wearing all black stands firmly at the end of the runway, dramatically peering at the audience. As the song continues to play with Jackson singing lyrics: “Beat me, hate me; You can never break me; Will me, thrill me, You can never kill me,” fashion workers reflecting a range of races, body sizes, and gender identities and experiences walked the runway. Bodies that would be considered too short, too fat, unable to pass as cisgender, or not white or not racially ambiguous enough for mainstream fashion were selected to walk in the show and for Stuzo’s collection. The clothing designs were just as subversive as the bodies wearing them, which demonstrates that while clothes can be political and take on their own meaning, bodies complicate and propel those meanings. As fashion workers walked the runway, cheers from the audience filled the room, unapologetically affirming the queer people that graced the runway.

A mash-up of images signifying Black resistance, feminism, equality, struggle, and liberation plays on a loop on the projection screen at the top of the runway. The mash-up includes an image of a woman holding a cardboard sign with “Equality” written on it; a picture of Sandra Bland, a Black woman who was pulled over, arrested, and died in police custody in 2015; and an image of Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old Black boy killed in 2012 by a neighborhood vigilante George Zimmerman. An image of the 2015 Times Magazine cover depicting the Baltimore uprisings appears in the mash-up; the cover of Beyoncé’s 2016 album Lemonade; and pictures of President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama—who at the time were concluding their second term—appear in the presentation. There is also a slide with a quote from actor and feminist Emma Watson that reads, “Gender equality is not a women’s issue it is a human issue. It affects us all.” Another slide reads, “upon demand the riches of freedom.” The clause is an excerpt from a line in Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I Have A Dream Speech,” in which he proclaims, “And so, we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand, the riches of freedom and the security of justice” (King 1963). A visual that appears in several still photos taken by photographers is a slide with a black background and the words #BlackLivesMatter typed with white letters. At the end of the show, the clothing company owner walked down the runway and raise their fists, a gesture synonymous with the Black resistance movements of the 1960s and 1970s.