5.1. Philosophical Sense

Transcendence embodies three distinct senses: the metaphysically absolute, the divine realm, and a quality that surpasses a certain threshold, with the latter being the most commonly understood sense. The concept of transcendence in Confucianism pertains to the broadest and most encompassing interpretation (

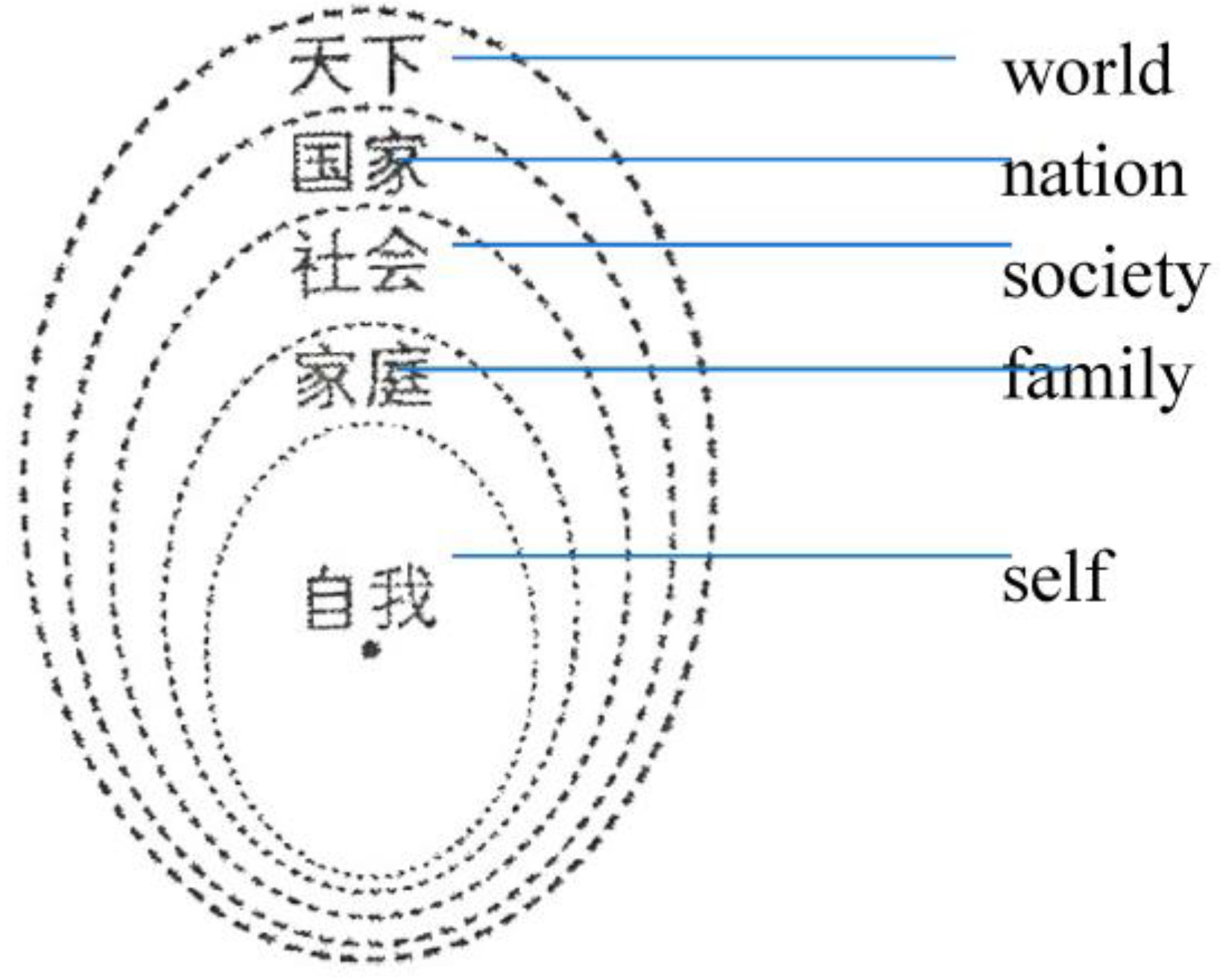

Zhang 2008), which can be understood as an ability of self-reflection or self-realization, namely, to separate oneself from the current environment. During self-reflection, there are four dimensions that need to be noted in the conceptualization of the Confucian style of moral reasoning. One is the question of the self. The second is the question of community understood in a very sophisticated way. In other words, the community is not only the nation, but also the society, our family, university, dormitory, and small working group. It is a much more concrete idea of a series of concentric circles.

The third one is nature and the fourth one is heaven, which is not God, Brahman, or Buddha, but a transcendent referent. Heaven is a category which cannot be reduced to nature. Put simply, the self is always an essential relationship. The community is ideally a community of trust. Nature is our home, and heaven is the ultimate source of the meaning of life (

Tu 1996). “It is through preserving one’s mind and nourishing one’s nature that one may serve Heaven” (

Bloom 2009, p. 144). The initial motivation of Confucianism to transcend or learn is not for parents, society, or state, but for cultivating and improving one’s own personality. Inward cultivation is to study objects, gain knowledge, upright the mind, and accumulate sincerity. Outward cultivation is to cultivate the self, regulate family, govern the state, and then lead the world to peace (

Tu 2012). Confucianism attaches great importance to the subjectivity of the individual and morality, centering around “the self”. It holds that an individual is by no means an isolated self, but the center of a radiating relationship network. According to Mencius, there are five human relations: “that between parents and children there is affection; between ruler and minister, rightness; between husband and wife, separate functions; between older and younger, proper order; and between friends, faithfulness” (

Bloom 2009, p. 57). The notion of radiating circles is also consonant with Hume’s concentric circles of reducing loyalties, which posit that “human beings love and are loyal to their families first, and then their loyalty diminishes as they move from the center to the periphery” (

Calloway-Thomas 2010, p. 4). Only by extending the love of oneself to others can we make long-term meaningful work for the country and the world, as shown in the following radiating figure (

Tu 2012, p. 98):

The Confucian Style of Moral Reasoning.

![Humanities 13 00108 i001]()

The view of transcendence from the perspective of Afrocentricity also refers to a quality that transcends ordinary experience and appears in the harmonious relationship between man and nature or individual and group (

Asante 2003). The harmony between man and nature is basically anthropocentric: man is the core of existence, with all the other elements in the natural world being perceived in relation to this pivotal human position. As the explanation of humans’ origin and sustenance, God seems to exist for the sake of individuals. Animals, plants, land, rain, and other natural objects and phenomena are seen as components of the human environment, deeply integrated into the African people’s profound understanding of the cosmos (

Mbiti 1970).

Corresponding to the four dimensions of self-reflection in embodied Confucianism, Africans also have their own ontology, which is divided into five dimensions (

Mbiti 1970, p. 20):

God as the ultimate explanation of the genesis and sustenance of both man and all things.

Spirits being made up of superhuman beings and the spirits of men who died a long time ago.

Man including human beings who are alive and those about to be born.

Animals and plants, or the remainder of biological life.

Phenomena and objects without biological life.

With man as the center, the Afrocentric transcendence is also embodied in the harmony between individual and group in the form of horizontal and vertical kinship systems. The horizontal system can be described as an expansive, all-encompassing network that extends in all lateral directions, aiming to include every member of a local community. This implies that each person is interconnected with every other person, and there is a rich vocabulary of kinship terms available to express the precise kind of relationship pertaining between two individuals (

Mbiti 1970). The individual’s awareness of their own identity, the duties they are bound by, and the rights and responsibilities they have towards themselves and others is only fully realized in the context of their relationships with others (

Mbiti 1970). The vertical system includes the departed and those yet to be born. The genealogy gives a profound sense of historical continuity, a feeling of being deeply connected to one’s roots, and a profound sense of duty and engagement to perpetuate the lineage (

Mbiti 1970).

In Africans’ view, the two kinds of life are interdependent and inseparable. They believe that human society is a continuous family of the dead, the living, and the coming (those yet to be born) (

Zhang 2021).

From the perspective of the cultural community, the philosophical senses of transcendence in embodied Confucianism and Afrocentric religion both value man’s important role in the universe. The difference lies in the fact that transcendence in embodied Confucianism is anthropocosmic, which means a continuous interchange of vital energy between the human body (anthropo-) and Heaven, Earth, and the myriad things (cosmic). With man as the starting point of an ever-expanding network of relationships, Confucian transcendence includes inward cultivation and outward cultivation by way of our bodies being experientially in communication with every conceivable modality of being (

Tu 1992). Afrocentric transcendence is anthropocentric by holding that everything is in relation to the central position of man, who especially transcends the simple experiential life with a sense of obligation and deep rootedness in the form of the horizontal and vertical kinship systems.

5.2. The Ultimate Goal

In the Confucian tradition, the concept of benevolence in the form of “the unity of heaven and earth” is the highest embodiment of self-transcendence, which means benefiting both self and others (

Tu 2012, p. 105), and is manifest in the following quotations:

“Heaven is my father and Earth is my mother, and even such a small being as I finds an intimate place in their midst. Therefore, that which fills the universe I regard as my body and that which directs the universe I regard as my nature. All people are my brothers and sisters, and all things are my companions.”

“When the Mean, the great root of all-under-heaven and Harmony, the penetration of the Way through all-under-heaven are actualized, Heaven and Earth are in their proper positions, and the myriad things are nourished.”

Dong Zhongshu, the most famous Confucian scholar of the Han Dynasty, greatly reinforced the metaphysical concept of benevolence. He elevated it to a theological level (he named it after the archaic “way of heaven”), claiming that it was the source of the existence of the whole universe and the ultimate external moral core. He also put forward the thought of “unity of nature and man”, which was regarded as the perfect theory of Confucianism by the Song Dynasty, Ming theory, and even contemporary Confucianism, and was constantly inherited and expounded. Therefore, as a transcendent being, Heavenly Way also exists in the heart of human beings. “Heaven, human nature, and nature are intrinsically integrated with each other. This is the basic feature of Chinese classical thought” (

Zhang 2008, p. 120). This concept finds its expression in many Confucius sayings like “extending the respect of the aged in one’s family to that of other families and extending the love of the young ones in one’s family to that of other families” and “If you want to establish yourself, help others establish themselves”, which reflect a win–win concept.

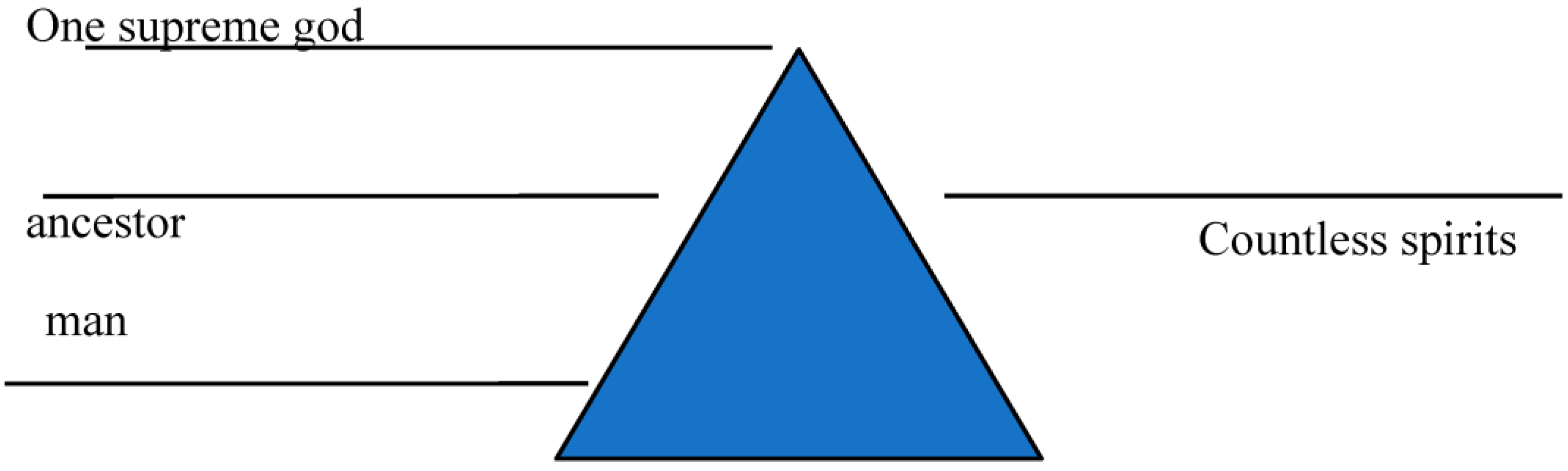

The ultimate goal of Afrocentric religion can be illustrated with a diagram. The apex of the triangle symbolizes the supreme god in heaven, and the man is at the bottom of the line, which symbolizes the land. The ancestors and countless spirits are on slanting edges separately (

Zhang 2022).

![Humanities 13 00108 i002]()

In this diagram, God is the creator and the force that maintains human life; the spirits interpret the fate of humanity. Humans are at the core of this existential framework. The animal, plants, and all natural phenomena and objects form the backdrop of human existence, offering sustenance and, if necessary, a spiritual connection. This human-centered view of existence is an indivisible whole, a unity that cannot be disrupted or annihilated. To undermine or eliminate any part of this framework would be to jeopardize the entire reality, including the divine being, which is an impossibility. Each form of existence is contingent upon all the others, necessitating a delicate equilibrium to prevent these elements from becoming too distant or overly intertwined (

Mbiti 1970).

Therefore, according to Afrocentric religion, transcendence is, in the end, “the regulation of a harmonious power”, which guides us to seek the “type of connections, interactions, and meetings that lead to harmony”. “I am most healthy when I am harmonized with others. I am most in touch with transcendence when I am moving in time to others” (

Asante 1998, pp. 201–4). The secret of African American spirituality is that the individuality of the responsibility cannot be carried out without others. Our own transcendence can only be reached with the help of others. It can be represented by the philosophical and religious concept of Maat, which essentially means “truth, justice, balance, harmony, righteousness, and reciprocity” (

Asante [2000] 2007, p. 186).

In the context of the Sino-African cultural community, the ultimate goal is to foster a solidarity that embodies the harmonious and reciprocal principles found in Afrocentric religions and embodied Confucianism. But with the goal comes along different human propensities. Afrocentric religion attaches greater importance to individual responsibility while embodied Confucian thinkers believe that the goal of transcendence entails sympathetic and empathic identification, indicating a common experience of “forming one body with all” (

Tu 1992, p. 97).

5.3. Vehicle for Transcendence

When talking about the vehicle for transcendence in embodied Confucianism,

Tu (

2012, p. 98) maintains that it is necessary to “learn to be human or build character”, rather than “simply acquire knowledge”. It should be a broadening process of learning for the sake of the self as a central relationship, which is a ceaseless process. One way of looking at this endless process is to imagine our life in terms of a series of concentric circles from the person to the family, to neighborhood, to society, to nation, to the world, and beyond. Anything that a person does is meaningful not in a very limited, private sense, but politically, socially, and even cosmologically. To say the self is the central relationship is to suggest the idea of the self as a stream that flows, rather than a static structure, which is always in a ceaseless process of transformation full of unpredictabilities, new possibilities, experiences, and new kinds of danger. Each human being is a concrete living being situated in a particular time, space, and all kinds of social forces (

Tu 1996).

Confucianism believes that the primordial ties are so much a part of us. Not only do they need to be recognized as constraints, but also they should be recognized as resources for self-realization or transcendence. Therefore, the answer is that a person can become what he or she ought to be not by transcending his or her ethnicity, gender, or language, but by realizing himself or herself through his or her ethnicity, work, and gender. In this way, those constraints will become a way of trying to free oneself. To transform the constraints into instruments of self-realization becomes an important aspect of the Confucian quest for transcendence. Each community that is meaningful to our personal self-realization is both a condition as well as a constraint and an instrument of self-realization. If we cannot go beyond our self-centeredness, we suffer from egoism and selfishness. We can only care for the things that are immediately relevant to us, not even our close family members. But if we can only relate meaningfully to our family members, rather than anyone else, then Confucian ethics becomes a kind of mafia ethic. Internally there is a great deal of sense of affection and concern, but very brutal, sometimes extremely insensitive to the area that is outside the family circle. If we do not go beyond our neighborhood, we suffer from parochialism. If we do not go beyond our ethnic group, we suffer from our ethnocentrism. If we cannot go beyond our country, we suffer from nationalistic chauvinism. If we cannot go beyond our own gender group, we suffer from either exclusive male orientation or exclusive female orientation. If we cannot go beyond the human species, we believe that anything that is good for the human species is good for everything. Man is the measure of all things. Then, we suffer from a human disease—anthropocentrism (

Tu 1996).

Then, what is the best way to broaden this process of learning?

Tu (

1996) suggests transcendence or self-realization should be realized in ordinary human existence, which implies another deepening process and takes our body absolutely seriously. Confucian learning is body learning. The body is not something we own, but a place where we are in. We learn to become our bodies. All learning is to allow the experience of learning to be inscribed in our body, which is transformed as a proper expression of our emotions and of our rational way of dealing with the outside world to purify our soul and to make our spirit brilliant. Therefore, the Confucians talk about learning archery, song, dance, and calligraphy, which are all connected with the body discipline, or ritualization that allows the body to follow certain kinds of rituals.

Huang (

2007, pp. 196–97) also maintained that this type of body, as a “moral agents with the ability to think and make value judgments”, is “thoroughly penetrated by social values and norms”. For example, when Confucius describes the realm of “sixty years old and obedient”, the spiritual progress of his journey, the “body” in this realm does not refer to a human organ with hearing ability, but a body that can make a judgment “in the face of all kinds of value discourses”, so that any discourse that enters the “ear” will be “obedient,” and there is no longer any “contrary to the ear” speech. Therefore, to realize transcendence in personality, rationality, and morality, the key vehicles are dialog and listening, which have a long history in China as in the

Analects of Confucius. Dialogue can cultivate our ability to listen, especially to the voices of those who do not share our values. The morality of listening is a very important value in Confucianism. In Mencius’ description, Confucius’ life realm is expressed by music, which is the echo of the harmony between heaven and earth. From that harmony, all things receive their being (

Chapter of Yue Ji n.d.). In the Confucian Temple, you can listen to the” sound of gold (indicating the music is just beginning) “and “jade (indicating the music is almost ending)”. In the opening ceremony of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, the performance of rites and music represented Chinese Confucian culture. The so-called harmony is the pleasure achieved by the “resonance of various musical instruments” (

Tu 2012, p. 44), with which to appease and purify people’s hearts, stabilize society, and achieve the function of individual spiritual transcendence and national governance.

Similarly, the Afrocentric vehicle for transcendence, according to Asante, is also firstly to interact with others, accompanied by magical words. What African preachers were “seeing or experiencing or trying to analyze was the way the African world approached the generative powers of the spoken word” (

Asante [2000] 2007, p. 68). It is only in the give and take of the nommo, not in the lives of solitude, that we find energy. The most beautiful thing is ecstasy that occurs when a group of people have got on the same road to harmony at the same moment in the collective expression of power, which is the true manifestation of spirituality and the state of transcendence. The value put on the spoken word is the message of both sacred and secular orators in the African American experience, as can be found in Malcolm’s and Martin Luther King’s rhetoric, which was meant to move their audiences toward the ultimate goal of possession, or attaining harmony through style and power (

Asante 1998).

The second vehicle is rhythm, especially the call-and-response mode, which is a principal path to transcendence for African Americans. For example, the short story

Sonny’s Blues by the famous African American writer James Baldwin shows the great charm of black music represented by blues and jazz: the revival was being carried on by three sisters in black, and a brother. All they had were their voices and their Bibles and a tambourine. But their unity and cooperation allowed them to achieve the artistic charm of black music. “As the singing filled the air the watching, listening faces underwent a change, the eyes focusing on something within; the music seemed to soothe a poison out of them; and time seemed, nearly, to fall away from the sullen, belligerent, battered faces, as though they were fleeing back to their first condition, while dreaming of their last” (

Baldwin 1998, p. 854). Through the description of the Revival meeting, Baldwin not only promoted the spirit of unity in the creation of black folk music and the soothing effect of music on black people, but also combined music with another black tradition—religion, consciously raising music to the height of religion (

Bi and Tan 2011). Another case in point is Ralph Ellison’s works; the deep and melancholy blues music in his novels, as a metaphor for black people’s way of living, is not only a kind of emotional text used for performance, but also a survival philosophy and expression transcending suffering (

Tan 2007). According to

Asante (

1998, p. 210), “a people oppressed and discriminated against created a liberated and free thought” in the form of music, which contains “the quality of freedom and transcendence”, and is the essence of the Afrocentric ideal as expressed in African American culture.

From the perspective of the Sino-African cultural community on the vehicle for transcendence, we may observe that both philosophies acknowledge the transformation of the constraints of primordial ties or ethnicity into tools for self-realization, achieved through the medium of music, which brings harmony, purification, and freedom to individuals and helps them transcend the restrictions of reality. In addition to that, embodied Confucianism values body learning and discipline in the form of ritualization while Afrocentricity prioritizes the generative powers of the spoken word toward the ultimate goal of possession or transcendence for the communal good.

5.4. Orientation of Time

A point of departure in the embodied Confucian style of transcendence is a concrete living human being here and now, and reflecting on things at hand and very close to our immediate concern. This is sharply contrasted with some of the great spiritual traditions like Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism, and so forth, which assume there is some spiritual sanctuary, a realm that is particularly meaningful to us and not necessarily directly linked to the world here and now (

Tu 1996). However, Confucians maintain that an individual is not only connected with his or her family, society, country, and the world in space, but also with his or her past and the future in time. For example, the “sacrifice of rites” is the Confucian ancestral worship. As the saying goes, “Pay a careful attention to the funeral rites to parents and recall forefathers, then the virtue of the people will resume its proper excellence”. If the governor treats death as an important matter and honors the ancestors of distant generations, then the morality of the people will tend to be rich (

Tu 2012). In other words, the essence of the present can only be enhanced by integrating the legacy of the past with the aspirations of the future. In the Confucian ethos, the concept of a utopia is not sought beyond the confines of society; rather, it is cultivated within the very fabric of society itself. Similarly, the pursuit of heaven is not a journey to a separate realm but a quest to elevate the earthly realm to a state of grace. Unlike the seclusion of Buddhist and Christian monasticism, Confucius advocated for the cultivation of virtue in the midst of daily life, where the noblest spiritual ideals are not merely contemplated but lived and experienced. This is the essence of embodied Confucianism, where the pursuit of the divine is intertwined with the mundane, and the transcendent is found in the ordinary (

Tu 2012).

The concept of time in traditional African societies does not hold the same academic interest as it does for Western cultures. In these societies, time is viewed as a tapestry woven from past events, current experiences, and imminent occurrences. This perspective leads to a two-dimensional understanding of time, characterized by a rich history and a present moment, while not neglecting the future because the latter is also embodied in the ancestors. The Western linear perception of time, which encompasses an extensive past, a present, and an endless future differs from African thought. The future is considered almost non-existent because it is unmanifested and unrealized, thus it cannot form part of the temporal framework that is recognized in African traditional thinking (

Mbiti 1970).

When explaining the orientation of time in Afrocentric transcendence, Asante holds that the person does not look for external powers to produce self-definition or self-transcendence, but develops inherent powers as an extension into the future of those who have gone before. The person is a testament to his or her forebears in a different guise, living in a different world (

Asante 1998). In reality, African people place a profound emphasis on the significance of history. They hold the belief that following the cessation of physical life, a person’s trace does not swiftly vanish. The individual’s presence is sustained through the memories of those who were acquainted with him during his earthly existence and have outlived him. Individuals honor their legacy by recalling the names of their ancestors, though it is not always explicitly stated. Traditional Africans cherish the memory of their ancestors’ demeanor, traits, utterances, and the significant events of the life of the ancestors. If they “appear” (as people believe), they are recognized by name. The deceased ones are primarily perceived by the elder members of their family line, and seldom, if ever, by the younger generation (

Mbiti 1970).

As far as the worship of ancestors is concerned, Afrocentricity is consistent with embodied Confucianism, which holds that ancestors seem to be more important than gods in everyday life. We must revere and appease our ancestors. They must be summoned and respected as agents of change. Ancestors help us understand human society because they live in it with a keen insight into the nature of ordinary life, represent moral and social values, and could serve as guiding principles for a good society (

Li 2017), where we become more human and in tune with the rhythms of the universe, therefore, realizing the transcendence embodied in harmonious power (

Asante 1998).

Although both perspectives share a transcendental view, they exhibit significant differences. Confucian transcendence is embodied in the harmony of past, present, and future, with a particular focus on the present moment. It posits that every individual should lead a daily life infused with the highest spiritual values, which are not just anticipated in the future but are actively experienced in the present, with great respect for the past, which is memorialized in the ancestors. This in turn enriches the current moment with the legacy of the past. In contrast, the Afrocentric concept of time is two-dimensional, characterized by a profound sense of the past and the present, yet with an almost negligible sense of the future. Their transcendental experience of time is manifested in the cultivation of inherent abilities that are inherited from ancestors, drawing strength from those who have preceded them. This does not mean that Africans have no conception of the future. Rather, it is a matter of emphasis.

5.5. Thinking Pattern

The “exclusive dichotomy” approach in Western philosophy is characterized by the “either/or” methodology, which is evident from the mind–body dualism in ancient Greek philosophy, through to the spirit–flesh, God–human (creator-creation) dichotomies in later Christian thought, and extending to the distinctions between the objective and subjective, materialism and idealism. These concepts have all employed mutually exclusive categories as the fundamental criteria for reasoning.

Contrasting with Western linear thinking, the transcendent perspective found in embodied Confucianism includes a “dialogical dichotomy” in the form of “both-and”. This could be aptly described as the yin–yang mode of thinking, which represents a more integrated and harmonious approach to philosophical inquiry. According to this mode, the yang is in the yin and the yin is in the yang in the form of mutuality and interchange.

Tu (

1992, p. 96) explained this mode of thinking as follows:

“The relationship between yin and yang is, therefore, both contradictory and complementary. The creative tension engendered by the fundamentally different thrusts of vital energy provides the wellspring for the great transformation of Heaven, Earth, and the myriad things. Actually, not only concrete living things but all modalities of being, including mountains, rivers, rocks, buildings, economic structures, political institutions, social organizations, and cultural artifacts, are the results of the generative power of yin-yang vital energy. The self, family, community, state, world, and universe are all suffused with the same kind of energy that makes the body alive”.

In essence, all things hinge on personal development. While managing one’s household requires a complex process of self-cultivation, governing a state presents additional challenges beyond this, though it may not be as intricate as achieving global harmony. In the pursuit of universal peace, the importance and complexity of self-cultivation become even more pronounced. To put it another way, when a household is in order, the focus is primarily on self-cultivation. When a state is governed, the task is not only self-cultivation but also includes the regulation of households. And when striving for world peace, the challenges encompass not just self-cultivation and household management, but also the governance of the state itself (

Tu 2012).

The concept of yin-yang is also mirrored in the progression from sensitivity to sensibility, from sensibility to rationality, and ultimately from rationality to the realms of sympathy and empathy. This progression uncovers the essence of transcendence within the framework of embodied Confucianism. It implies that “sensibility is inherently linked to sensitivity; rationality encompasses both sensibility and sensitivity; and in the case of sympathy and empathy, all three—rationality, sensibility, and sensitivity—are integrated” (

Tu 2012, p. 218). Beyond moral and intellectual dimensions, there exists a form of “knowledge of experience” or embodied knowing, which transcends the confines of the mind and heart (

Tu 2012, p. 249). This is akin to a skill, a kung fu if you will, that “the body cultivates to assimilate the external world” (

Tu 2012, p. 198). This cyclical mode of thought embodies the dynamic interplay between the part and the whole.

When talking about the difference between the Western thinking pattern and the traditional African world view, Asante maintains that the Western bias of categorization, which “divides people into teachers and pupils, sinners and saved, black and white, superior and inferior, weak and strong has developed the catastrophic disharmonies that we experience in the world”. The opposite of this bias is “the practicality of wholism, the prevalence of poly-consciousness, the idea of inclusiveness, the unity of worlds, and the value of personal relationships” (

Asante [2000] 2007, p. 36) as expressed in Afrocentric transcendence. According to it, a healthy personality is grounded in the African idea of spiritual commitment to an ideological view of harmony, which is the source of all literary, rhetorical, or behavioral actions. The only important task of a person is to realize the promise of becoming human by performing actions that lead to harmony in the midst of others. One form of harmony where the Afrocentric transcendence finds its expression can be seen from the vertical kinship systems, which includes the departed and those yet to be born. Unlike Christianity, which maintains the separation of the spirit from the body and “a reincarnation that means the reentering of a body of the spirit that had left the dead person”, an Afrocentric point of view believes that an ancestor is not “a ghost, or spirit, but a person who lives, speaks, makes decisions, and can present in many different individuals at the same time and never leave the world of invisibility” (

Asante [2000] 2007, p. 62). Therefore, a one-to-one reincarnation is replaced by the ancestor’s appearance in several descendants. Take the Akan for example; their concept of community is in the construction of the person as “soul, personality, and blood” (

Asante [2000] 2007, p. 62). However, this cannot be understood in a Platonic sense, featuring the analytical thinking mode; it must be seen as an inseparable force of the human, a holistic thinking pattern, which shows there are no split humans in African culture. The holistic belief in the community of the dead as one with the living community means more than the oneness between the past, present, and future. “There was only what had been done before and what would be done again. This was not to be thought of as past and future, but, rather an orientation to the whole universe, a perspective on natural and human phenomena, and an acceptance of the inter-connectedness of the living with the dead and even the unborn” (

Asante [2000] 2007, p. 43).

Although there is a shared holistic approach to transcendent thinking in both embodied Confucianism and Afrocentricity, it is important to recognize the distinct differences, unique elements, and potential limitations within embodied Confucianism. These aspects highlight the inherent paradoxes of transcendental thought, which can be outlined as follows:

The Confucians place a significant emphasis on self-cultivation as a pathway to moral and intellectual development. However, this focus can sometimes lead to egocentrism and self-centeredness, where the individual’s growth becomes an end in itself, potentially neglecting the collective good. While Confucianism highly values the family unit as a foundational element for personal growth and self-realization, it can also foster nepotism and an unhealthy degree of family connectedness. This can result in a form of familial loyalty that resembles the close-knit, yet potentially corrupt, structure of mafia organizations. Confucians consider their immediate neighbors and community as integral to forming a supportive network. This network can be immensely powerful in fostering a sense of belonging and mutual aid. However, it can also lead to parochialism, where local interests and perspectives dominate, potentially excluding broader societal concerns. Confucianism is not immune to ethnocentrism, nationalism, anthropocentrism, and other forms of centrism. These biases can limit the universal application of Confucian principles, as they may be overly focused on the cultural, national, or human perspective, to the exclusion of other forms of life or broader ecological considerations (

Tu 1996).

This paradox confirms Derrida’s argument that community has a suicidal tendency in the form of “autoimmunity”, which results from the overemphasis on an aspiration and an ideal featured by commonality, sharing, belonging, connection, and attachment, and therefore, might lead to the disintegration of transcendental community.