Abstract

The Count de Rethel: An Historical Novel (1779) can be ascribed to Georgiana Spencer Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire (1757–1806) as a translation of Anecdotes de la cour de Philippe-Auguste (1733) by Marguerite de Lussan. The action is set at the court of Philip II of France, known as Philip Augustus, at the time of the war with King Henry II and the Crusade with Richard I, known as the Lionheart. This inspired revival of fictionalised medieval history heralding romanticism in the age of sensibility refashions the codes of chivalry according to the aesthetics of the second half of the eighteenth century. This essay focuses on the interplay between fiction and history, between the present of writing and the rewriting of history through Cavendish’s translational prism, featuring the Middle Ages as a golden age of heroism and the Count de Rethel as a paragon of ancient virtue set against contemporary men of fashion.

1. Introduction

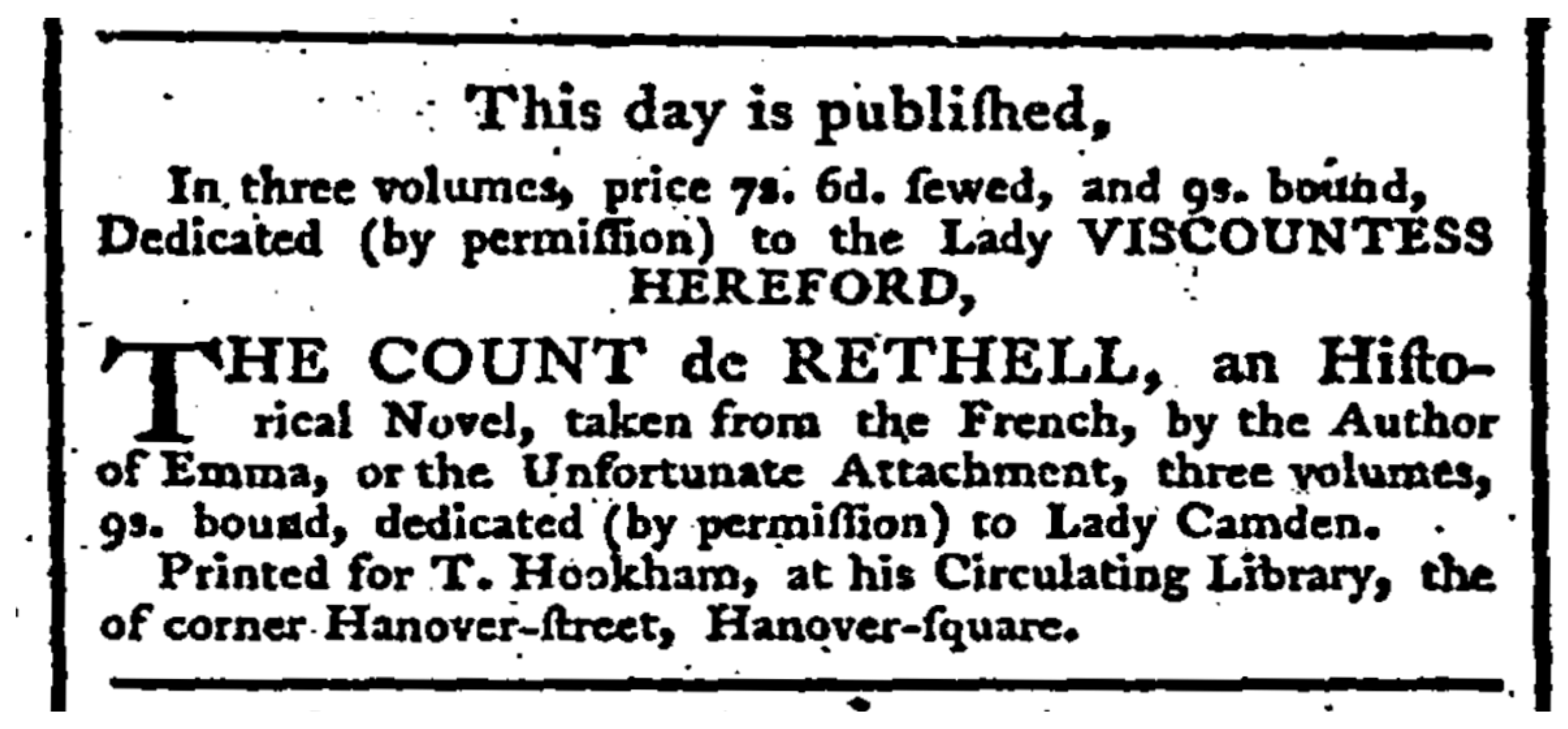

In May 2022, while looking into the critical reception of the Duchess of Devonshire’s published works in the newsroom of the British Library, I saw, advertised in an eighteenth-century newspaper, that the book The Count de Rethell (sic): An Historical Novel (Figure 1), published by Hookham in 1779, was by the same author as Emma, or The Unfortunate Attachment, that is to say, Georgiana Spencer Cavendish, the 5th Duchess of Devonshire, who published her books anonymously. The epistolary novel Emma, or The Unfortunate Attachment has been attributed to her by Jonathan David Gross, who re-edited the volume in 2004, based on a 1784 Dublin edition whose title page states that it is “by the author of The Sylph”, a work that is reckoned to be by Cavendish (Devonshire [1779] 2001). Evidence is still thin, but in the absence of any other attribution, The Count de Rethel can be considered part of her literary production (Devonshire [1773] 2004). This historical novel claims to be “taken from the French”, but it took me a long time to trace the source text, so much so that I had accepted the idea that it was probably a pseudo-translation, a practice that was frequent in the eighteenth century, as pointed out by Gillian Dow in her book chapter “Criss-Crossing the Channel: The French Novel and English Translation”. Following the footnotes in an article about the revival of the chivalric novel at the end of the eighteenth century, I consulted Anecdotes de la cour de Philippe-Auguste (1733) by Marguerite de Lussan and recognised it as the original of The Count de Rethel. The action is set at the court of Philip II of France (1180–1223), known as Philip Augustus, at the time of the war with King Henry II and of the Third Crusade (1189–1192) with King Richard I, known as the Lionheart, who was Henry II’s son.

Figure 1.

Advertisement of the publication of The Count de Rethel. “Advertisements and Notices”, General Advertiser and Morning Intelligencer, 21 January 1779, Issue 590. Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Burney Newspapers Collection. By permission of the British Library.

Anecdotes and Rethel are three-volume historical novels of about 1100 and 850 pages, respectively. Comparing the English version with the French version, a few salient features can be highlighted. The English advertisement mentions the following: “It has been taken from the French, without submitting to the slavery of a literal translation. The Editor did not think it improper to make such trifling alterations, here and there, as would make it more conformable to the general style of such performances, adopted by the writers of modern novels” (Devonshire 1779, Advertisement, iii). The translation proposed by Cavendish is rather faithful and flows with the same ease as the original composition. The first three sentences of the novel are quite representative:

Hugues, Duc de Bourgogne, Prince digne de regner, avoit trop d’intérêt de sçavoir tout ce qui se passoit à la Cour de France, pour ne pas y entretenir des intelligences secretes. Phililppe, connu par le surnom d’Auguste, si justement mérité & acquis, avoit succédé à son pere Loüis le Jeune. Le nouveau Monarque en prenant les rênes de son Empire, n’étoit appliqué qu’au bien de son Etat, & cela, dans un âge où les Princes se reposent volontiers sur l’habileté de leurs Ministres.(Lussan 1733 I, 1–2)

The generic hybridity that characterises Cavendish’s writing is manifest in her choice and interpretation of this very rich work by Lussan. The respected French author’s Vie de Louis Balbe-Berton de Crillon (1756) had attracted the attention of Samuel Richardson, who published a revised translation of it in 1760. Cavendish showed an eager interest in history, both French and English, and she loved reading novels. She wrote to her mother, Countess Spencer: “I have the rage of reading history to such a degree, that I devour what I read & feel about it as one does about a novel” (Devonshire Collection Archives 1778–1782, CS5/422)1. The interplay between history and fiction, modernity and tradition is central to an analysis of Cavendish’s The Count de Rethel: in it, in spite of the structural constraint of the translation, a personal vision can be seen.Hugh duke of Burgundy, a prince worthy to reign, had too much interest in knowing all that passed in the court of France, not to keep up secret intelligence with some belonging to it. Philip, known by the surname of Augustus, so justly merited and acquired, had succeeded his father Lewis the Young. The new monarch, in taking the reins of empire into his hands, had applied himself entirely to the well governing of his state, and that at an age when princes generally rely on the talents of their ministers, and save themselves the trouble of thinking about it.(Devonshire 1779 I, 1–2)

We will first consider the historical palimpsest Cavendish works from, which comprises both antiquity and the Middle Ages. We will then examine The Count de Rethel as a historical novel and a translation. Finally, we will analyse Cavendish’s novelistic rendering of the emphasis she placed on the notion of virtue and the aesthetics of sensibility.

But, first, let me present the main characters (Table 1) and give a brief outline of the main sentimental plot of The Count de Rethel.

Table 1.

Main characters in The Count de Rethel.

In volume I, Raymund de Rethel and Alicia de Rosoi love one another, but Alicia’s mother, Madame de Rosoi, because of her guilty passion for Raymund, keeps postponing the match after her husband, Lord de Rosoi, dies. The unnatural mother does her utmost to tear Alicia and Raymund apart, preventing their marriage and sending her daughter to the abbey of Chelles before marrying her to another man, the Count de Dammartin. The deaths of the latter and Madame de Rosoi enable the two lovers to prepare for their wedding, but volume II opens with the tragic end of Alicia, falling off her horse because of a wild boar. The inconsolable Raymund leaves the court and disappears for almost two years until he is found again at the court of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa in Germany. Raymund comes back to Paris and falls in love with Adelaïde de Couci, the very image of his deceased Alicia. She loves him, too, but has been betrothed to Albert du Mez by her father, Everard de Couci, who is the figure of the jealous parent seeking revenge on his daughter for not complying with his demand. Adelaïde flees to the abbey of Chelles in order to escape her father’s tyranny. At the end of volume III, Ralph de Couci, Raymund’s friend and Adelaïde’s brother, dies during the Third Crusade but writes a letter to his father imploring him to let his sister marry Raymund, and the two lovers are finally united.

The Count de Rethel is definitely fiction since no Raymund de Rethel existed at the turn of the twelfth century. In her plot, Lussan juxtaposes a real king and an invented count bearing the name of a real noble family and surrounds them with historical figures as well as characters from her imagination.

2. Antique Substratum and Glimpses of Medieval History

Lussan presents her main male characters as heroes, crowned with laurels. William des Barres is nicknamed “the Achilles of France” after the Third Crusade (1189–1192). Gabriella de Fagel, a married woman, has secretly loved Ralph since before her marriage. She calls him Alcides, which is one of Hercules’s names. In volume I, which dwells on the chivalric accomplishments of the four warriors sent by Philip II to the camp in Burgundy, namely Raymund de Rethel, Ralph de Couci, William des Barres and Albert du Mez, the entrance to the camp is associated with the image of the “triumphal arch”, which points to ancient Roman architecture as a monumental structure erected in honour of a hero or a historical event. Main female characters Adelaïde de Couci, Gabriella de Fagel and Elizabeth du Mez are themselves called “heroines”, each of them torn between reason or duty and passion like the tragic heroines of ancient Greece. The translator—presumably Cavendish—expands the antique imagery by developing “l’Amour” (Lussan 1733 II, 50) into “the fickle deity” (Devonshire 1779 II, 43) and “le cruel destin” (Lussan 1733 III, 252) into “the fatal Sisters” (Devonshire 1779 III, 238), that is to say, the Fates, and by characterising Adelaïde as a Roman virgin who, were she to refuse to marry Albert, would therefore be “dragged to the altar, and there bound by the most sacred oaths to live a Vestal, since she would not vouchsafe to be his wife” (Devonshire 1779 III, 48).

In its structure, The Count de Rethel is reminiscent of the Alexandrian romance. As pointed out by David Richter in his chapter “The Gothic Novel and the Lingering Appeal of Romance”:

The love between Raymund and Alicia follows the same pattern, as it survives a double parental opposition, Alicia’s death, the Third Crusade and the passing of time; finally, the lovers can marry. Further, Madame de Rosoi, Alicia’s evil and unnatural mother, can be seen as a witch or the enchantress Circe in The Odyssey. By her artifice, she deceives everyone, including the king. She entices Guebriant into serving her and has him do everything she wants as if moved by a love philtre or love spell. She calls him “my agent” (Devonshire 1779 I, 254) and makes him disappear at will, as Cavendish grammatically does in her translation: “je fis dire par Guebriant, au Comte de Dammartin” (Lussan 1733 I, 321) becomes “I sent directions to the Count de Dammartin” (Devonshire 1779 I, 256–57). After completing the task Madame de Rosoi asked of him, Guebriant is rejected by her.[…] there is no doubt that long-form prose fiction goes back more than fifteen centuries to the Alexandrian romances of the first to third centuries AD […], fictions in which narrativity is generated by the separation of the nobly born lovers, who are subjected to tremendous dangers by natural disasters and human adversaries before being finally reunited in erotic bliss.(Richter 2020, p. 473)

Philip II, known as Philip Augustus, is reminiscent of Augustus, the first emperor of Rome, and the advertisement reads that “It was the age of heroism and romance”, linking ancient and medieval times. With offhand allusiveness, Cavendish refers to several historical events and characters throughout the novel, though she hardly provides any dates featured in the notes to the original text. This practice illustrates Richard Maxwell’s notion of “history in glimpses” as follows:

On the first page of the novel, the narrator mentions that Philip Augustus had succeeded his father Lewis the Young, although then, for the rest of volume I, the story of Raymund’s love for Alicia takes centre stage. Similarly, the rivalry between the king and his dukes resulting in the establishment of the camp in Burgundy provides the occasion to describe the display of military force at the tournament. The battle of Bouvines (1214) is alluded to (p. 216) as a later event. Emperor Frederick Barbarossa (1155–1190) is referred to at the beginning of volume II (p. 50), Isabella of Hainault is reported to have given the king a son (p. 72), Prince Lewis (p. 95), and Saladin to have conquered Jerusalem (1187) (p. 142). In volume III, Henry II’s son, Richard the Lionheart, is the French king’s new rival (p. 85). Philip launches a war in Berry (1187) (p. 85) and Maine (p. 137), where he takes Le Mans (p. 144). The siege of Tours is mentioned (p. 146), and so is King Henry II’s death in Chinon (p. 147). The news of the death of Philip’s wife, Queen Isabella, is alluded to (p. 226) before Philip and Richard I are reported to meet at Vezelay (1190) (p. 234) and leave for the Crusade. The capitulation of Acres (1191) is referred to (p. 247) before Philip’s return to France.this phrase is meant to suggest the flickering, equivocal way in which historical materials surface, then disappear, then surface once more, in fictional works by Lafayette and her successors. History is an on-and-off presence in these books. It is glimpsed, at somewhat unpredictable junctures, rather than viewed or experienced steadily.(Maxwell 2009, p. 12)

Cavendish uses romance and the secret history as a generic framework. Rebecca Bullard notes that “romance shares with secret history an emphasis on the importance of love as a controlling passion in public as well as private affairs, an interest in the private motivations behind public actions, and a commitment to exploring the most secret space of all: the interior world and the hidden passions and motivations of individual agents” (Bullard and Carnell 2017, p. 5). In volume II, Cavendish provides a secret history of the death of the Duke of Brittany, Geoffrey Plantagenet, who reportedly died from the wounds he received in a tournament but whom she has poisoned by the Count de Fougeres (sic) because of the Duke of Brittany’s love of Madame de Fougeres. In her book chapter “Secret History, Politics, and the Early Novel”, Bullard explains that secret history plays with the categories of fact and fiction. There does not seem to be, on Cavendish’s part, a Whig political intention to reinterpret the past but rather a behind-the-scenes interest in the private side of history. Bullard writes the following: “Secret history’s female-centered plots, its interest in what goes on behind closed doors, and its self-conscious approach towards the concept of fiction may have helped foster these characteristics in the mid-eighteenth-century novel, but the legacy is not a direct one” (Bullard 2020, pp. 151–52).

3. “An Historical Novel. Taken from the French”

Supposing that Cavendish is the author of The Count de Rethel, she must have indulged her taste for history and novels in her translation of Lussan’s work. Historical fiction indeed relies on the interplay of history, romance and novel within it. As underlined by Janet Todd reflecting on the term “novel”: “At different periods it is interchangeable with romance and with history (these are not discrete categories and romance could at times rely heavily on documentation). In the early years, the novel often claims a historical status, in the later an empirical, verifiable and general truth” (Todd 1989, p. 6). The novel’s unstable relation to “truth” has been much debated and depends on the definition that is given of it in its relation to objective or subjective reality.

Cavendish’s marked interest in history steadfastly grew throughout her life; and, on the occasion of the birth of her illegitimate daughter by Charles Grey, she made the most of her exile to the continent in the years 1791–1793 to perfect her geographical and historical knowledge of France, a country she had known since she was a child owing to her parents’ Francophilia and connection to the French court2. At that period, Cavendish had gathered sufficient information to write what she calls “a little description of France”, which is, in fact, a short history of France destined to her eldest daughter, Georgiana Dorothy, known as Little G. She devoted a few lines to each of the French kings, from the Merovingians to the Capetians (Castle Howard Archives 1791–1792). During the summer of 1792, Cavendish and her intimate friend Elizabeth Foster stayed at the house of famous historian Edward Gibbon in Lausanne and took part in the rich intellectual life of the place.

Cavendish must have read history books as much as novels as her sources for The Count de Rethel. She had access to the best private libraries in the country, Althorp House and then Chatsworth House in particular, and only a portion of the volumes that she read are part of what has been recreated of her library (Vidal, forthcoming), which accounts for the lack of information in this regard. Apart from the reference works she may have consulted, it is known that her library included Histoire des révolutions arrivées dans le gouvernement de la République romaine (1727) by René Aubert de Vertot, known as Abbé Vertot, as well as Clélie, histoire romaine (1654–1660) by Madeleine de Scudéry and Le Siège de Calais, nouvelle historique (1739) by Claudine-Alexandrine Guérin, marquise de Tencin, whose action is set in 1346–1347, during the Middle Ages. No book of Cavendish’s related to the twelfth century—when the action of The Count de Rethel takes place—has been found so far, but internal evidence shows that she knew about that period. While dealing with the events of the Third Crusade, which culminates in the siege of Acres at the end of volume III, Cavendish inserts substantial extra historical information into her translation in several instances, notably about the personal and family life of King Henry II (pp. 147–50) and the situation in Messina between Sicilian king Tancred, Richard I and Philip II (pp. 235–37), in order to shed light on the subject.

Through its subtitle, “An Historical Novel”, the text self-identifies with the genre of the historical novel, while the original French title, Anecdotes de la cour de Philippe-Auguste, points to another literary tradition. In her book chapter “The Porter Sisters, Women’s Writing, and Historical Fiction”, Devoney Looser notes that the coining of “historical novel” in a title is anterior to the beginning of the nineteenth century:

In a footnote that illustrates her point, Looser mentions The Count de Rethel: An Historical Novel published in 1779, which makes its supposed author–translator, Cavendish, a trendsetter in the genre for judiciously choosing her source text and fashioning it to the new tastes of the reading audience. She continues as follows: “The English vogue for using the past to respond to the present has been dated to the 1790s, which has led scholars to link the flourishing of the historical novel to the French Revolution […]” as an underlying force shaping intellectual productions (Looser 2010, p. 245).Once we investigate the use of the term ‘historical novel’ or ‘historical romance’ on the title pages of eighteenth-century fiction, we discover that the label (if not the genre tout court) pre-dates Scott and the Porters by decades. The terms are used as the subtitle of dozens of productions of the 1790s, but they appear on occasion much earlier”.(Looser 2010, p. 239)

The Count de Rethel is an anonymous translation but this does not mean that Cavendish’s contemporaries were ignorant of the fact that she was a writer—it soon became common knowledge that she was the author of The Sylph (1779)—and efforts in literary history have been made since the 2000s, ensuring that she may still be considered as such today. Catherine Gallagher thus vindicates the use of the expression “nobody’s story” by claiming the anonymous women writers’ presence through their apparent absence:

It is known that Cavendish did not sign her published works, maybe because she was a woman and an aristocrat. As explained by Todd:[…] the “nobodies” of my title are not ignored, silenced, erased, or anonymous women. Instead, they are literal nobodies: authorial personae, printed books, scandalous allegories, intellectual property rights, literary reputations, incomes, debts, and fictional characters. They are the exchangeable tokens of modern authorship that allowed increasing numbers of women writers to thrive as the eighteenth century wore on”.(Gallagher 1994, p. xiii)

Although Todd places emphasis on Cavendish’s personal life and gives a reductive presentation of the author’s second epistolary novel, she makes it clear that writing was unusual for a member of the aristocracy and that they must have had a particular incentive to do so, as is the case here.Aristocrats rarely turned to the novel except under some idiosyncratic compulsion; the obsessively gambling Duchess of Devonshire squandered a fortune at cards and was probably the author of a fantasy about gambling entitled The Sylph (1780 sic) in which […] an attentive male lover helps save a woman from herself. But this, like the size of the Duchess’s debts, was unusual”.(Todd 1989, p. 132)

As underlined by Dow, translation is excellent practice for fiction:

Writing fiction and translating fiction are closely linked in Cavendish’s practice since both The Sylph and The Count de Rethel were published in 1779.Translation has long been viewed as a rite of passage for the woman novelist in the period. Josephine Grieder is just one critic to have pointed out that almost every woman novelist of the latter half of the eighteenth century translated from French ‘often as she was pursuing her own work independently’. This can be partly explained by the increasing emphasis on female education in French as an accomplishment for gentlewomen. The constant comparisons between English women writers and what were seen as direct earlier French models such as Scudéry and La Fayette may provide another reason […].(Dow 2020, pp. 98–99)

Marks of the contemporaneity of her translation are to be found in several instances. Through the praise of chivalric heroes, contemporary men of fashion (who are already debunked in the advertisement) become the butt of the translator’s criticism. Praising Ralph de Couci’s behaviour towards Gabriella de Fagel, she adds that “he did not resemble the gallants of our age” (Devonshire 1779 II, 211) who, implicitly, act with impropriety. Cavendish adds eighteenth-century high-society expressions such as “to introduce her into the great world” (Devonshire 1779 II, 120) to allude to Adelaïde’s entrance into the world, “the circle they had left with Madame de Couci” (Devonshire 1779 II, 212) to denote a fashionable group of friends, or “did you ever see so beautiful an angel as Madame de Fagel was yesterday?” (Devonshire 1779 II, 117)—“angel” being a laudatory word that Cavendish frequently uses in her writings. At the end of volume I, Raymund’s tour of Italy is reminiscent of the Grand Tour, especially as Cavendish uses the periphrasis “that land of sights” (Devonshire 1779 I, 261) to refer to this country. She also adds to the original mentions of many monuments and deplores the number of foreign visitors, who seem less distinguished than before: “la variété des Objets, les respectables monumens de l’Antiquité, le nombre d’illustres Etrangers, leur attention à réfléchir & à raisonner sur ce qu’ils voïoient“ (Lussan 1733 I, 327–28) is translated as “the numbers of objects that presented themselves to my eyes; those noble monuments of antiquity so thickly sown in every part of that country, the quantity of strangers who flocked thither, their observations on all they viewed, and their way of reasoning” (Devonshire 1779 I, 262). To give a reality effect to her writing, Cavendish does not hesitate to insert an allusion to health problems travellers may encounter, having Raymund say the following: “one day, that I had staid at home from indisposition, I saw a courier arrive, who brought me a letter” (Ibid.). Travel writing, which was a very popular genre in the eighteenth century, recorded objective facts and increasingly incorporated subjective interpretation. Cavendish’s library unsurprisingly comprised works such as Fielding’s The Journal of a Voyage to Lisbon (1755), Smollett’s Travels through France and Italy (1766), Ives’s A Voyage from England to India (1773) or Johnson’s A Journey to the Western Isles of Scotland (1775).

4. The Idealising Standard of Virtuous Sensibility

The most striking feature in Cavendish’s love-centred novel is the pervasive use of the vocabulary of sensibility, starting with the term itself (“sensibility”, “insensibility”, and “sensible”, meaning “aware” or “touched”). She was very much defined by the aesthetic of sensibility, a literary movement which, under the influence of Richardson and Rousseau, had been in vogue from the late 1760s and spread throughout Europe. In her book on sensibility, Todd gives the following definition of the word: “Sensibility […] came to denote the faculty of feeling, the capacity for extremely refined emotion and a quickness to display compassion for suffering” (Todd 1986, p. 7). Particular emphasis is laid on the senses, such as sight, and Cavendish regularly uses words connected to the senses in her text. For example, she adds that “it enervates the soul” (Devonshire 1779 I, 184) in her translation, expressing the role of the nerves in the transmission of information from the senses to the brain; she renders “je veux en vain douter de mon malheur” (Lussan 1733 I, 247) by “I would impose upon my senses” (Devonshire 1779 I, 199), in which the faculty of perceiving is linked to understanding. Sensibility is conceived as a higher disposition that enables the human being to appreciate beauty, as appears in Cavendish’s translation of “né pour être sensible” (Lussan 1733 I, 147) as “sensible, and destined to feel the force of beauty” (Devonshire 1779 I, 116).

As evidenced in Todd’s definition, sensibility manifests itself as compassion for others. Cavendish sometimes uses the word “sensibility” for “compassion”, seeming to see them as synonyms. Ralph’s compassion for his friend is manifest in volume I when Raymund recounts his love tribulations: “At length, my dear Raymund, said Ralph, I may take breath; your story has so oppressed my heart, that, until this moment, I have not been able to do it—Never have I suffered so much before from hearing of the calamities attending any other person!” (Devonshire 1779 I, 263; the last clause is added by Cavendish). To raise compassion is one of the aims of sentimental literature, which is repeatedly achieved in the novel. Attention to others is conversely mirrored in attention to oneself or introspection, a practice that Cavendish’s mother, Lady Spencer, encouraged in her daughter, which was a painful experience for the latter. Similarly, in an added passage of more than a page, Gabriella urges Adelaïde to “examine” her own heart before accepting Albert or rejecting him, and both women find themselves in a state of “dejection” (Devonshire 1779 II, 169–70).

The characters’ inner lives are given such importance that a parallel can be drawn with the “closet” drama, a genre interested in the exploration of intimate passions, with dilemmas, obsessions and whispered confessions. Every hero and heroine in this novel is torn between their duty or reason and their passion, and the closet itself is a recurring setting where secret conversations are held, and sometimes overheard. In the case of Ralph, it is the place whence he overhears a conversation between his sister and the woman he loves, Gabriella (Devonshire 1779 II, 200–1). Because of his passion, which forces him to rob her of her secret, the hero finds himself in the degrading position of a peeping Tom, taking the reader-spectator with him. His lack of delicacy creates a scene when it escapes him, in a conversation with Gabriella, that he knows she secretly loves him. He indeed lets out the secret of her love for him to her in front of his sister, Adelaïde, who comes under suspicion by her friend for letting him know about it. Ralph immediately clears Adelaïde who blames him in the terms of “you stole into the privacy of our conversation”, foreshadowing the fact that Gabriella will no longer agree to see him (Devonshire 1779 III, 106). The closet can be linked to the symbolic object of the cabinet; the French word is the same, “cabinet”, for both the room and the piece of furniture. The cabinet is the case or cupboard where Gabriella keeps what she holds dear: a letter by her friend Adelaïde and a poem by Ralph, whom she secretly loves. Here, again, the character’s privacy is violated as she beholds these two objects (Devonshire 1779 III, 184–85), this time by her husband whose jealous anger drives her to an untimely death.

Cavendish generally adds text to her translation in the most emotionally charged moments, such as the death of Gabriella at the hands of her cruel and jealous husband in volume III. Indications are inserted (for example, “more faintly” to characterise her answer to her husband as she is dying, p. 270) and a whole dialogue between Gabriella and her father is created, which sounds like a tirade, at the end of which the wronged but virtuous woman dies:

Cavendish frequently resorts to italics in her translation to enhance certain aspects, thus offering her interpretation of the text. She markedly resorts to italics when Adelaïde implicitly discloses her love to Raymund and reproaches her father for denying her any agency: “You have no rival, replied she; and yet you will be as miserable as he is. My father, irritated at my refusal of the Marshal, will never permit me to make a choice he would have prided himself in doing, had he made it for me” (Devonshire 1779 II, 163). The translator regularly uses superlatives and dashes, which do not appear in the original text and are part of the rhetorics of sensibility. For example, “un père” (Lussan 1733 II, 21) becomes “the tenderest, the mildest of parents” (Devonshire 1779 II, 20) and Adelaïde, full of joy, thus informs her brother and Count des Barres that the king will favour her love for Raymund: “I have nothing more to fear! He knows I love; he does not blame my choice—He will interpose with my Father for me—He will make Albert espouse Constance de Montmorenci—He loves Raymund—His goodness is beyond conception!” (Devonshire 1779 III, 132). At the end of volume III, one scene is too intense for Cavendish to describe: it is the reunion of Adelaïde to her mother, after being disowned by her father for refusing to marry Albert du Mez. The three characters are shocked by the news of Ralph’s death: “There are some scenes which do not come within the power of description: that of the meeting between Madame de Couci and Adelaïde was one of them” (Devonshire 1779 III, 283). That is an addition by Cavendish, who also makes Everard, Ralph and Adelaïde’s inflexible father, weep. His tears are the way to the forgiveness he offers his daughter, in compliance with his son’s dying request to see her and his friend Raymund de Rethel united at last.I lay my death to nothing but the weakness of my constitution; but ere I go, let me exculpate myself from any charges that may be brought against me. You know I have not been happy; Monsieur de Fagel has been less so: we have both been the victims of our own sentiments; mine, however, never caused me to swerve from the duty I owed him: he misconstrued my meaning often, and never encouraged the propensity I had to do right; jealousy had made him gloomy and perverse: he imputed to me as a crime the melancholy I should have lost, had he not by his own fixed mine. I do not accuse him for this; his nature could not be changed: I sincerely pity him, and beg of you to tell him I would fain have us exchange a mutual pardon.(Devonshire 1779 III, 272–73)

The insistence on morality is characteristic of Cavendish’s translation. The English title highlights the particular merit of Raymund, who embodies constancy and is a paragon of ancient virtue while his lover, Alicia, and later, Adelaïde, whom he loves as Alicia’s double after her accidental death, is a symbol of chastity. Cavendish further justifies Raymund’s love for Adelaïde by adding Alicia’s explicit dying request to him that he marry and have children in the future: “[…] and, when the lenient hand of time shall have closed the wounds your poor heart now bleeds with, let some amiable female supply my place in it; your family and name must not be extinct” (Devonshire 1779 II, 18). Alicia’s very last words to Raymund become proleptic when, upon meeting Adelaïde for the first time, he sees her as a new Alicia: “He could scarcely credit his eyes: they presented to him the image of the Countess de Dammartin; it was she herself that appeared before him!” The end of the description of Adelaïde further highlights the sameness between the two women: “[…] it was Alicia living again in Adelaïde, and Raymund stood gazing at her as such” (Devonshire 1779 II, 100). Together, Raymund and Adelaïde, who is Alicia’s living double, are the image of the ideal couple, setting an example to follow. The translator explains how to act with propriety in various love situations and how blameworthy those are who do not. In this respect, courtship should always remain chivalric. Mentioning Ralph’s attitude towards Gabriella, Cavendish adds: “he did not resemble the gallants of our age; he respected the virtue of the woman he adored, and would have died sooner than have sullied it by any attempt to lessen the value she had for her duty. Satisfied with being preferred by her, he only aimed at maintaining, by his behaviour, the good opinion he had acquired” (Devonshire 1779 II, 211–12).

In one instance, Cavendish even goes as far as to say the exact opposite of the original work to express her own vision. On the subject of fleeing a person that one loves, the French text reads as “les plus vertueuses sont celles qui y pensent le moins; leur vertu condamne leur sentiment, & cette même vertu leur cache le danger” (Lussan 1733 II, 244), which can be translated as “the most virtuous women are those who less think about it; their virtue condemns their feeling, and this same virtue prevents them from seeing danger”, while the translator’s version states that “the most virtuous females are always the most diffident of themselves; the prudence which bids them shun temptation is the surest guardian of their honour” (Devonshire 1779 II, 211), a more true-to-life moral principle as it seems.

In her translation, Cavendish clearly condemns marital infidelity. “J’adore depuis trois ans Madame de Fougeres” (Lussan 1733 II, 98) becomes “I have, alas! been unhappy enough to let my heart wander from its fidelity to my wife, and, Heaven pardon my crime! have indulged myself in an unlawful passion for Madame de Fougeres.—It has been chastised by the pangs I now endure.—Oh! may they be expiatory!—But let the mischief end with me” (Devonshire 1779 II, 80). Whether Cavendish herself wrote the advertisement or not, the same moral judgement can be found in the point against contemporary men of fashion, both French and English. The hero is thus praised as follows:

“Antiquated” seems to be spoken from the point of view of the fashionable people who are the butt of criticism, which really means that antiquity should be the new fashion.He was romantic; he would not have deceived his friend, or have forsaken his mistress, on any account: sincerity had not then been banished from Courts, nor constancy been laughed at by Men of Fashion. Such as he was, he is recommended to the patronage of those who can distinguish worth though somewhat antiquated, and can excuse the aukwardness of one who will not shine amongst the Beaux of Paris or London at present”.(Devonshire 1779, Advertisement, ii–iii)

5. Conclusions

By way of conclusion, I would like to put the novel The Count de Rethel in a biographical perspective. Through her choice of Anecdotes de la cour de Philippe-Auguste as the source text for her translation, Cavendish expressed her attachment to the French language and history as well as to the chivalric values associated with the Middle Ages as a historical period. As pointed out by Margaret Anne Doody, the historical novel “provided a means of return to space, grandeur, action, adventure, and foreignness. Walter Scott is considered to have perfected the mode, but not before female predecessors had worked on it, as he himself acknowledges in his own notes to Waverley (1814)” (Doody 1996, p. 295). The Count de Rethel, subtitled “An Historical Novel”, uses history as a canvas to explore the possibilities offered by translation, which extends to the rewriting of entire passages and the addition of new ones, according to how they struck Cavendish’s sensibility. Her first act of rewriting lies in the title that she chose for her translation, The Count de Rethel, instead of Anecdotes de la cour de Philippe-Auguste. Through this change, she shifted the focus from multiplicity to unicity, from the impersonal to the personal, making one of the main characters in the source text the eponymous hero of this work and fashioning him as a romantic hero avant la lettre. Cavendish repeated this personal interpretation of a title in her translation of Metastasio’s sacred opera Isacco Figura del redentore as Abraham, switching the focus from the son, Isaac, to the father, Abraham, who is, indeed, the central actor in this drama.

Despite the glamorous and often frivolous image attached to her, Cavendish was a well-read woman, and her library included material sources for her to work from. Among what has been recreated of it, she read Horace, Lucan, Virgil, Plutarch and Homer in their English translation, Amadis de Gaule, Gil Blas, Mme de Scudéry’s Clélie, Mme de Tencin’s Siège de Calais, Mme Riccoboni’s works and Fénelon’s Télémaque in the French text. She must have read Mme de La Fayette’s La Princesse de Clèves as well. Life at Coxheath Camp in Kent, where Cavendish accompanied the Duke of Devonshire for a few months in 1778, provided her with an occasion to learn more about France (at a time when England was in danger of invasion) from a number of possible informers and books3. The whole of Cavendish’s correspondence has been censored and edited, but what remains of that year reveals that she was reading Spenser’s Faerie Queene (1609), which follows the adventures of several medieval knights using the literary technique of entrelacement, in which several simultaneous stories are interlaced in a larger narrative, as is the case in Lussan’s Anecdotes, which follows the adventures of the Count de Rethel and other heroes—and heroines. Cavendish wrote to her mother “I am reading the Fairy Queen (sic) & consequently Spencer (sic) mad” (Devonshire Collection Archives 1778–1782, CS5/217), later commenting on the figure of the Red Cross Knight. The style of her letters to her mother sometimes becomes archaic; she also mentions a short poem about virtue and reason set in ancient times and another about a heroic knight (Devonshire Collection Archives 1778–1782, CS5/224 and CS5/253). The tone of her correspondence is rather melancholy for the end of that year and she keeps coming back to the notion of virtue. From her personal situation in 1778, it seems that Cavendish was partly describing her own story through that of the Count de Rethel. It is known that, in July 1778, at camp, the Duke of Devonshire had an openly public affair with Lady Jersey, whom she considered a close friend. The double treason appears to have had a lasting effect on Cavendish. This is the untold story of that period in her life, something she could not write about, except, maybe, to a very close correspondent. The only mark left of it in her letters is a veiled reference to her uneasiness with Lady Jersey (Devonshire Collection Archives 1778–1782, CS5/248).

The Sylph and The Count de Rethel were both published anonymously in 1779. The first was an insider’s criticism of the corrupt mores of eighteenth-century London high society in the shape of an epistolary novel. The second is a translation of Lussan’s Anecdotes or anecdota, a synonym for secret history. Taken together, the two works by Cavendish, The Sylph and The Count de Rethel, are the two sides of the same coin: life as it is, and life as it should be; reality as fiction, and fiction as a way to reach a higher kind of reality, the ideal of sensibility.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed during this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Cavendish’s vastly unpublished correspondence is mainly held at Chatsworth House and Castle Howard. |

| 2 | General information on Cavendish is taken from the biography by Amanda Foreman (Foreman 1998). |

| 3 | It would be tempting to assume that Cavendish met Viscountess Hereford (presumably Henrietta Charlotte Tracy, 12th Viscountess Hereford), to whom The Count de Rethel is dedicated, at Coxheath Camp, since the latter’s husband, Edward Devereux, 12th Viscount Hereford, was Colonel of the Montgomeryshire Militia from 1764 to 1778; but this meeting appears unlikely as Devereux had been succeeded in his functions by the Earl of Powis before Coxheath Camp was formed. The 12th Viscountess Hereford’s name is not mentioned in Cavendish’s correspondence at that period and she did not seem to be part of Cavendish’s circle, which is why the relation between the two women still needs to be researched. |

References

- Bullard, Rebecca. 2020. Secret History, Politics, and the Early Novel. In The Oxford Handbook of the Eighteenth-Century Novel. Edited by James Alan Downie. Oxford: Oxford University Press (OUP), pp. 137–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bullard, Rebecca, and Rachel Carnell. 2017. The Secret History in Literature, 1660–1820. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Castle Howard Archives, J18/67/2.

- Devonshire Collection Archives, CS5 series: 217, 224, 248, 253, 422.

- Devonshire, Georgiana Spencer Cavendish (Duchess of). 1779. The Count de Rethel: An Historical Novel. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, Gale. London: T. Hookham. [Google Scholar]

- Devonshire, Georgiana Spencer Cavendish (Duchess of). 2001. The Sylph. York: Henry Parker. First published 1779. [Google Scholar]

- Devonshire, Georgiana Spencer Cavendish (Duchess of). 2004. Emma; or, the Unfortunate Attachment. A Sentimental Novel. Edited by Jonathan Gross. New York: State University of New York Press. First published 1773. [Google Scholar]

- Doody, Margaret Anne. 1996. The True Story of the Novel. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dow, Gillian. 2020. Criss-Crossing the Channel: The French Novel and English Translation. In The Oxford Handbook of the Eighteenth-Century Novel. Edited by James Alan Downie. Oxford: Oxford University Press (OUP), pp. 88–104. [Google Scholar]

- Foreman, Amanda. 1998. Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire. London: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, Catherine. 1994. Nobody’s Story. The Vanishing Acts of Women Writers in the Marketplace, 1670–1820. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Looser, Devoney. 2010. The Porter Sisters, Women’s Writing, and Historical Fiction. In The History of British Women’s Writing, 1750–1830. Edited by Jacqueline M. Labbe. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan UK, vol. 5, pp. 233–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lussan, Marguerite de. 1733. Anecdotes de la cour de Philippe-Auguste. Book Digitised by Google from the Library of the University of Michigan and Uploaded to the Internet Archive. Paris: Veuve Pissot. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, Richard. 2009. The Historical Novel in Europe, 1650–1950. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (CUP). [Google Scholar]

- Richter, David. 2020. The Gothic Novel and the Lingering Appeal of Romance. In The Oxford Handbook of the Eighteenth-Century Novel. Edited by James Alan Downie. Oxford: Oxford University Press (OUP), pp. 472–88. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, Janet. 1986. Sensibility: An Introduction. London: Methuen. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, Janet. 1989. The Sign of Angellica: Women, Writing and Fiction, 1660–1800. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal, Hélène. Forthcoming. From Shelf- to Self-Fashioning: The 5th Duchess of Devonshire’s Library. In Corpus Feminae. Edited by Guillaume Coatalen and Aurélie Griffin. Clermont-Ferrand: Presses Universitaires Blaise Pascal.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).