Abstract

To diagnose someone’s reasoning today as “sophistry” is to say that this reasoning is at once persuasive (at least to a significant degree) and logically invalid. We begin by explaining that, despite some recent scholarly arguments to the contrary, the understanding of ‘sophistry’ and ‘sophistic’ underlying such a lay diagnosis is in fact firmly in line with the hallmarks of reasoning proffered by the ancient sophists themselves. Next, we supply a rigorous but readable definition of what constitutes sophistic reasoning (=sophistry). We then discuss “artificial” sophistry: the articulation of sophistic reasoning facilitated by artificial intelligence (AI) and promulgated in our increasingly digital world. Next, we present, economically, a particular kind of artificial sophistry, one embodied by an artificial agent: the lying machine. Afterward, we respond to some anticipated objections. We end with a few speculative thoughts about the limits (or lack thereof) of artificial sophistry, and what may be a rather dark future.

1. Introduction

The sophists have been resurrected. That is one quick way to express what this paper presents. We mean nothing supernatural here; neither Protagoras nor Gorgias, nor for that matter, any other famous sophists, are alive and among us today. However, we claim that the methodological spirit of the sophists has been reincarnated, not in any humans, but in AIs, or—to use the more academic phrase—artificially intelligent agents (see Russell and Norvig 2020).

We begin by affirming that the sophists were, as is commonly believed, indeed driven in no small part by a desire to argue persuasively for conclusions—independently of whether these conclusions in fact hold (Section 2). Next, we briefly express the view that, in today’s world, at least in the realm of politics, and especially in the case of the United States, sophistic battle is deleteriously afoot (Section 3). We then turn to a discussion of sophistry in artificial agents and explain that this development is wholly unsurprising (Section 4). Following this, we make matters quite concrete by presenting the lying machine, an artificial agent capable of some rather sophisticated sophistry (Section 5). Afterward, we respond to two anticipated objections (Section 6). We wrap up with a brief review of the journey taken herein, and then some admittedly dark comments about the future and artificial sophistry, which end with a remark about what, at least in principle, could be done to ward off that future (Section 7).

2. The Lasting Legacy of Sophistry

Suppose that Jones and Smith are engaged in passionate debate about—to pick an arena likely these days to evince passions—politics, and specifically assume that the latest argument pressed by Smith against Jones triggers this dismissive rejoinder from the latter: “Hah! That is mere sophistry!” What do you think Jones means to convey by this diagnosis? In our experience, and, we wager, in that of the reader’s, the answer to this question likely to be returned by the college-educated is “Well, I think he means to say that Smith’s argument is invalid, but also that it’s calculated to persuade nonetheless, and he may even be conceding that this argument in fact has some persuasive power.” This is a solid answer. That such answers can be routinely obtained in thought-experiments such as ours here indicates that the ancient view of sophists as manipulative persuaders has been a lasting one. In the present section, we first consider this view in a bit more detail (Section 2.1). We next briefly consider whether the view is in fact correct, or at least plausible (Section 2.2). Then, we lay out more carefully what sophistry is, or at least, what a sophistic argument is (Section 2.3), by putting on display some arguments intended to serve as illuminating specimens.

2.1. The Received View of the Sophists

The legacy of the sophists—at least among the general public—amounts to little more than that ‘sophistry’ is a byword for insincerity, self-interest, and, above all, manipulative persuasion. This attitude is, in fact, not restricted to the public of today; the academy, too, when its members attempt to ascertain why so many modern humans believe bizarre propositions, views sophistry as reasoning that is at once persuasive and utterly invalid. A case in point is found in Steven Pinker, who in his latest book, Rationality (Pinker 2021), wraps up his narrative by explaining that human irrationality is in part the result of sophistry, which he classifies as “an art of persuasion” carried out independent of underlying truth (Pinker 2021, chp. 10, sct. “Motivated Reasoning”). Yet, inspired by Hegel’s (1857) and Grote’s (1879) influential defenses of the sophists, many contemporary scholars (e.g., Marback 1999; McComiskey 2002; Tindale 2010) have attempted to rehabilitate the sophists’ reputation and to illuminate their distinctive contribution to rhetoric. However, despite such efforts, the unaffected public and rationality researchers such as Pinker remember the sophists only in pejorative terms as purveyors of the semblance of wisdom and not the genuine article because they rejected the doctrinal ideal of ‘truth’ to promulgate instead the virtue of persuasive ‘cleverness’ without regard for moral good (the view taken by Aristotle in On Sophistical Refutations, in Forster and Furley 1955). Naïve and unfair as this received view of the sophists may be, the truth is that ancient sophistic techniques have been vibrantly alive and well and continuously refined for over two millennia—persuasive techniques that prey upon the audience’s cognitive dissonance, ignorance, intellectual laziness, and desire for comforting belief reinforcement. The continued practice of such techniques in politics, commerce, and civil society is the lasting legacy of the sophists. This, at any rate, is our view. However, the following should be asked here at the outset of our essay: Is the received view of the sophists defensible in the light of the relevant scholarship? We believe it is, and briefly defend our position next.

2.2. Were the Sophists Really By-Hook-or-By-Crook Persuaders?

Evidence that the sophists were, at least in large measure, concerned to persuade without regard to inferential validity or to truth can, for example, be found in the work of Edward Schiappa (1999). Yet, there are certainly some who resist this view, which is our own. For example, resistance to the view of sophists as persuaders is voiced by Michael Gagarin (2001). Here is Gagarin setting the stage early in his essay:

[The] account of sophistic rhetoric as the art of persuasion is accepted, as Schiappa has recently noted, by virtually all scholars since Blass, more than a century ago. And even recent scholars like Cole, Poulakos and Swearingen, who approach sophistic rhetoric from new perspectives that downplay its connection to persuasion, have not directly questioned the connection between rhetoric and persuasion. Explicitly or implicitly most scholars agree that for the Sophists, to speak well meant to speak persuasively and to teach rhetoric was to teach the art of persuasion. Scholarly consensus is always comforting, but (as the reader may suspect) my aim in this paper is not to reaffirm the consensus but rather to reconsider the whole issue and ask, did the Sophists really aim to persuade? The answer, I will suggest, is that persuasion was only one goal of sophistic logoi, and not the most important.(Gagarin 2001, p. 277)

Notice the telling word “one” in the final sentence in this quotation. Its presence is sufficient for our purposes because the use of this word by Gagarin means that even those determined to elevate the reputation of the sophists are, in the end, when all the evidence is before us, forced to grant that the ‘sport’ of argumentation was at the heart of sophism. For the sake of economy and efficiency, we rest content with pointing out that Protagoras—without question, one of the earliest sophists—placed great emphasis on the teaching of argument techniques. Those unfamiliar with the primary sources would be well-served by reading the Platonic dialogue, Protagoras (in Hamilton and Cairns 1961). Protagoras therein declares that were he not so adept in argument battles (he is a “skillful boxer” [339e] with words), his fame would never have materialized.1

2.3. What, Then, Is Sophistry?

We provide now the core of a general account of sophistry. We say ‘core’ because the present venue is not one in which it makes sense to propose a full, mature, and formal definition of sophistry. This is so not only because of practical constraints (e.g., insufficient space) but because we are not writing for mathematicians or logicians or AI engineers only, or even primarily.

To start, sophistry requires, first, a persuader (our sophist) who articulates an argument (or proof2) aimed at some audience in the hope of persuading that audience to believe some concluding proposition C. The second requirement is that the sophist knows to be, or at least could quite possibly be, inferentially invalid and/or non-veracious. Inferential validity holds of an argument when each inference within conforms to a valid form. For example, one might argue from (1) if someone has a net worth of USD two billion, then that person is rich, and (2) Jones is not rich, to (3) Jones does not have a net worth of USD two billion. The inference form of this argument is as valid as can be; the inference pattern is modus tollens.3 A veracious argument is one whose premises are all true; non-veracity holds when one or more premises are false. In the argument just given, (1) is true, but we do not know whether or not (2) is. So we cannot declare the argument veracious, nor can we declare it non-veracious.

We already have in play, at this point, quite enough to give our first illuminating example of sophistry, one that instantiates the general account we have in hand. The example runs as follows. Our sophist wishes to persuade an audience to agree that capital punishment should be used, and to vote accordingly, and toward that end, offers the following argument:

- (1)

- If less severe punishments deter people from committing crime, then capital punishment should not be used.

- (2)

- Less severe punishments do not deter people from committing crime.

- (3)

- Therefore, capital punishment should be used.

This can be a very persuasive argument, especially in the highly politicized, left vs. right polarized environment in which many (e.g., in the United States) people live, but it is invalid, as it is an instance within such an environment of the so-called myside fallacy, nicely presented and analyzed (replete by commentary on the environment to which we allude) by Pinker (2021, chp. 10, sct. “The Myside Bias”). The longstanding name for this fallacy, independent of the study of its persuasive force in political environments, is denying the antecedent. For a primary-literature discussion of the power of this fallacy to delude people, see (Gampa et al. 2019).4

Is there more to sophistry than what we have laid out to this point in the present section? Certainly. One line of augmentation of the account is that the agent must have a number of beliefs. For example, this agent must have beliefs about what believes before the sophistic argument is communicated, as well as belief about what is likely to believe after considers . More specifically, there will normally be a belief in the first grouping to the effect that , in fact, does not believe C, the final conclusion of , and a belief in the second category to the effect that, once takes in, will likely believe C. This is not an exhaustive list of epistemic attitudes operative in the carrying out of sophistry, but it suffices for present purposes.

3. Sophistic Impact in Today’s Digital World

Although opposed in its own day by Plato and Aristotle, sophism took hold of Athenian politics and helped to sound the death knell of Athenian democracy (Curtius 1870, pp. 548–49)—and sophistry has been an existential threat to democracies ever since. Fear of contemporary sophists and their ilk in part drove America’s founding fathers to establish a republic rather than a democracy. Nevertheless, sophistic practices emerged (e.g., pandering and yellow journalism) and continue to undermine the American experiment.

American society today is marked by extreme political polarization, opaque, well-funded “issue advocacy” groups, and politicians who echo and incite the most vocal within their political parties—frequently, a small minority of the most extreme. The free press and its cousin, popular media, openly advocate for politicians, policies, and political parties and stoke the fires of dissension as a means to ideological and commercial ends. As a direct consequence, in recent years, the public’s collective consciousness has been saturated with concerning stories of undue foreign and domestic influence on elections, election manipulation, back-channel government censorship of social media and the public press, and ostensibly U.S.-headquartered multi-national technology companies accommodating and facilitating the monitoring, unmasking, and censoring of the citizens of other (often non-democratic) countries at the behest of their repressive governments. Looking beyond America’s borders, we see a growing global tsunami of influence campaigns, disinformation, and subversion caused by state and non-state actors, hyper-motivated individuals and groups, and corporate marketeers. Whether intentional or not, these acts undermine rational discourse, objectivity, and valid reasoning grounded in—and in the pursuit of—truth.

Our self-selected, digitally enshrined, global socio-cultural media institutions fare no better than America’s political institutions. The rise of social media, streaming news and entertainment, and recent global crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic have driven the developed world to personal isolation, self-confirmatory information selection, and widespread fragmentation of the interpersonal and social spheres (Nguyen 2020). Even at its root, our digital ecosystem is retreating from civil, reasoned discourse and free expression. Control of the dominant platforms is consolidated in a small number of transnational corporations (e.g., see Kissinger et al. 2021, chp. 4) that often partner with governmental regimes to enact and enforce state-mandated censorship; even in “open” societies, debate is subject to biased, corporate or state-sanctioned censors (so-called “fact-checkers”) who are given the power to decide what is “true” and what is worthy of expression.5 The result is a world in which many social interactions are digitally mediated, externally framed, and potentially censored, and in which individuals are encouraged and incentivized to stay within the echo chambers that offer them the most comfort and pleasure—and best reflect what those in power want them to believe.

Certainly not all of these ills can be laid at the feet of the sophists, nor are all the manipulations (e.g., brute censorship) sophistic in nature. However, this state of affairs does ring of the sophistic themes of (i) privileging persuasion and personal/corporate gain over objectivity and truth; (ii) using what an audience wants to hear, and is poised to believe, to steer them to beliefs and behaviors that a speaker desires; and (iii) for vulnerable audiences, listening only to those speakers who entertain and reinforce what they want to believe.

3.1. AI and the New Digital Sophistry

In both the developed and developing world, speech has moved online, and sophistic practices have followed. Artificial intelligence is the engine for this new sophistic movement: while digital communications enables speech at a speed, scale, and geographic reach beyond anything previous generations could have imagined, it is AI that enables the generation, dissemination, and empirical confirmation of persuasive messages capable of influencing whole nations en masse or narrowly targeted groups and individuals. AI’s most recent contribution consists of generative systems—such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Stability AI’s Stable Diffusion—that are capable of image, voice, and video generation, and conversation and translation across languages and mediums (e.g., text-to-video and vice versa; see Maslej et al. 2023). The heralded promise and potential of these technologies have fueled a meteoric rise and rapid, widespread adoption,6 but these AI systems also come with some rather obvious risks for governments, free societies, and individuals (e.g., see Bletchley Declaration 2023). Generative AI systems are rarely grounded in facts (e.g., they regularly “hallucinate” fictions that they subsequently claim to be facts), they can be biased and erroneous, and there is little legal, financial, or moral accountability for their (mis)behavior. Their ease of use, linguistic fluency, and ability to promulgate “deepfakes” open up new avenues for AI-assisted criminality, disinformation, and deception. Beyond generative AI, other logicist and statistical techniques from the AI toolbox have been adopted and adapted to meet persuaders’ needs, including sentiment analysis, social-network analysis, the generation of decoy products and fake reviews, data poisoning, and many others. Moreover, AI can be used for more than just facilitating, targeting, and guiding sophistic or deceptive manipulations. AI can be employed to construct actual artificial sophists: machine practitioners who intentionally use persuasive yet fallacious argumentation to achieve their goals (this is discussed at length in Section 5).

4. Artificial Sophistry Is Thoroughly Unsurprising

That AI would be used as means for machine-mediated sophistry is surprisingly unsurprising. This lack of surprise is tied to the philosophical and aspirational roots of AI, a topic to which we now turn briefly.

4.1. AI and Artificial Agents

The discipline of artificial intelligence, or AI, as it is now commonly called, started in its modern form in 1956 at a famous conference at which John McCarthy coined the term that has stuck.7 With no loss of accuracy or generality, we can take AI to be the field devoted to the science and engineering of artificial agents; such a view accords directly with the dominant textbooks in wide use today (e.g., see Russell and Norvig 2020). However, what is an artificial agent? It is a thing, positioned within its environment, that maps what it perceives in that environment (i.e., percepts) to actions performed in that same environment. As to what the mapping is, that is actually quite straightforward: the mapping is a computation, consisting in what happens when some computer program is executed.

4.2. AI and Philosophy

The preceding description of AI, couched as it is in the logico-mathematical terms of computation, belies the aspirations and philosophical foundations of AI. The father of AI, Alan Turing, led by any metric a meteoric life, since—to mention but a few highlights—he was a hero of Britain’s Bletchley Park, the center of allied code-breaking during World War II, (co-)inventor8 of the mathematics of computation, a closeted and then convicted homosexual driven out of British government service who accepted chemical castration and ultimately committed suicide by cyanide in June 1954 at the age of 41, leaving behind a body of immortal work. For present purposes, important is the fact that it was Turing (1950) who posed the seminal question, “Can machines think?”—a question AI has been trying to answer (often in the affirmative) ever since.9

AI aspires to create machines that “think”, machines that exhibit intelligence akin to our own, and in the attempt reevaluates the nature of intelligence and personhood. As to whether the “minds” of such artificial agents (or “thinking machines”) are genuine or simulacra, this question is simply a restatement of the philosophical problem of other minds. AI does not shy away from this problem, nor from problems of agency, autonomy, epistemology, and ethics; in fact, these are practical issues for AI, and they are central issues in the history and philosophy of AI, as a recent essay by Bringsjord and Govindarajulu (2018) reveals.

4.3. AI, Sophistic AI, and Human Nature

There is a simple reason why the emergence of sophistic AI is unsurprising, one that goes deeper than the history, philosophy, or disciplinary practices of AI. That reason is this: as mentioned, AI aspires to create machines that think, machines that act and interact like us and with us.10 AI is an exercise in creation and invention whereby humankind stands in the place of God and creates (artificial) beings made in our image and reflecting our nature (e.g., our intellectual, mental, and social abilities). It is no wonder, then, that our digital progeny would be used for, and would enact, manipulation, deception, and sophistry, since these things have been part and parcel of human nature and humanity’s social and discursive practices since long before they were systematized by the ancient Greek sophists.11 By this light, sophistic AI was not only unsurprising and foreseeable—it was inevitable.

5. Arguments, Illusions, and The Lying Machine

Sophistic AI is literally a past accomplishment, not a prediction. Starting in the early 2000s, the application of AI to natural argumentation began to refocus on audience-centric systems that take subjective aspects of argumentation seriously (see Reed and Grasso 2001, 2007; Reed and Norman 2004),12 which resulted in the development of various neorhetorical (e.g., Grasso 2002) and logico-dialectical (e.g., Aubry and Risch 2006) approaches to persuasive and deceptive argumentation. In 2010, cognitive models were added to the mix, resulting in the lying machine (Clark 2010), an explicitly sophistic artificial agent that persuades by means of a combination of argumentation and illusion. In the remainder of this section we sketch out the key elements of the lying machine.

5.1. An Overview of the Lying Machine

The lying machine is an AI system for the manipulation of human beliefs through persuasive argument. The machine employs a cognitive model of human reasoning and uses this model to produce convincing, yet potentially disingenuous, sophistic arguments in an attempt to persuade its audience.

In design, the lying machine maintains conceptually separate repositories for its first- and second-order beliefs (i.e., its beliefs about the world and its beliefs about its audience’s beliefs about the world).13 The machine reasons over first-order beliefs in a normatively correct fashion using a variety of machine-reasoning techniques. When reasoning over second-order beliefs, the machine uses both normatively correct reasoning and a predictive theory of human reasoning, namely mental models theory (Johnson-Laird 1983, 2006a). In so doing, the machine internally contrasts (i) what it believes, (ii) what it believes its audience ought to believe were they to reason in a normatively correct fashion, and (iii) what it believes its audience will likely believe given their predicted fallibility.

In operation, the lying machine seeks to achieve various persuasion goals of the form “persuade the audience of X”, where X is a proposition about the world. Given a persuasion goal of X, the machine first forms its own justified belief about X.14 The machine then determines whether its audience ought to believe X and whether X can be justified in a convincing fashion based solely on second-order beliefs (i.e., beliefs it ascribes to its audience). If it is so, the machine constructs and articulates a credible argument for X.

The lying machine aims for perceived credibility as opposed to objective, logical, or epistemological credibility. While its arguments may be logically valid or invalid, the importance is that they appear valid to its audience (as modeled by the psychological theory at hand). Argument credibility is presumably enhanced by limiting the initial premises to what the audience is supposed to already believe. Furthermore, since the machine is not constrained by logical validity, it is able to produce all of the following types of arguments:

- A veracious argument for a true proposition emanating from shared beliefs;

- A valid argument for a false proposition emanating from one or more false premises that the audience erroneously believes already;

- A fallacious argument for a true proposition (an expedient fiction for the fraudulent conveyance of a truth);

- A fallacious argument for a false proposition (the most opprobrious form being one that insidiously passes from true premises to a false conclusion).

With the above repertoire in hand, the lying machine attempts to take on the pejorative mantle of the sophists by affecting arbitrary belief through persuasive argumentation without concern for sincerity or truth.

5.2. The Lying Machine’s Intellectual Connection to Sophistry

Ordinarily, liars and truth-tellers alike have in common an intention to be believed—to have their statements accepted as true, or at least sincere; Indeed, one of the perennial charges against the sophists is that they cared only about being believed and not at all about being truthful or sincere. When statements are of sufficient simplicity (e.g., innocuous, non-argumentative statements such as, “I did not eat the last cookie”), statement content only plays a small part in being believed. For innocuous statements, an audience’s grounds for belief lie outside a statement’s content, not within; belief acceptance and attribution of sincerity are based on such things as reputation, reliability, situational context, social convention, and implicit warranty of truth.

Innocuous, non-argumentative statements contain neither the evidence nor the imperative for rational belief. In contrast, arguments contain evidence and implications supporting an ultimate claim, and arguments seem to insist that the claim be accepted or rejected on the grounds given. Arguments function as a form of demonstration, as Aristotle points out in his Rhetoric (1.1 1355a, in Gillies 1823): they have the appearance (but not always the substance) of demonstrable justification that belief is warranted. For illustration, consider the following argumentative denial: “No, I did not eat the last cookie, Jane did. Go and see the crumbs on her blouse before she brushes them off.” At first blush, the argument appears to be more than just a denial and accusation; it offers on one hand the promise of corroborating evidence, and on the other an abductive explanation for any absence of evidence. Asking whether this argument is epistemically stronger than the non-argumentative assertion, “No, I did not eat the last cookie, Jane did”, misses the point. The point is that an argument draws an audience’s attention away from independent evaluation of claim and claimant and toward a justification of the speaker’s design.

Just as good evidence and arguments can convince us of facts that would otherwise seem preposterous (e.g., that some things routinely travel forward in time, or that there are perfectly clear and well-defined claims about arithmetic that are neither provable nor disprovable from the standard axioms of arithmetic), so also all manner of fallacies and false assumptions can be used to subvert reason and incline an audience to erroneously accept falsehoods as true. Were it the case that humans faithfully applied normative standards of reasoning, fallacious arguments would only injure the speaker by revealing their position as either foolish or false. However, unfortunately, this is not the case. As evidenced in a litany of studies going back to at least the works of Wason (1966) and Tversky and Kahneman (1974), humans are abysmal at normative reasoning and rational judgment.

Sophistic arguments are effective means for being believed—for consummating mendacity, manipulation, and lesser deceptions. The lying machine was built to test a particular approach to the practice of sophistry, one that exploits highly fallible heuristics and biases in human reasoning by incorporating so-called cognitive illusions (Pohl 2004) into arguments. This approach reflects the twin empirical facts that (i) many humans are, unknowingly, imperfect reasoners who predictably succumb to a host of biases and illusions, and (ii) many humans are supremely, yet undeservedly, overconfident of their ability to reason and to judge the reasoning of others. The results of this approach are potent arguments whose persuasive power is derived by turning the human audience’s own reasoning intuitions and inclinations against them.

5.3. Sophistic Arguments and Cognitive Illusions

While many forms of sophistry consist of subtle influence, subverting provenance, and stating outright falsehoods, the lying machine focuses on illusory arguments, a particularly pernicious form of sophistic argument that integrates illusory inferences so as to affect the appearance of objective, rational argument when it is in substance no more truthful than a bald-faced lie. So what is an illusory inference? It is when a bias or illusion in reasoning is treated as if it were a valid rule of inference, which sanctions its intuitive (but, of course, invalid) consequent. In turn, an illusory argument weaponizes illusory inferences, applying them in argument contexts where the (possibly fallacious) consequent furthers the argument’s ultimate aim. Since illusory inferences are not truth-preserving, an illusory inference can be employed, say, in the middle of an otherwise valid argument with true premises so as to effectively lead the audience down a primrose path to an objectively false conclusion.

Illusory inferences include traditional logical fallacies such as affirming the consequent and denying the antecedent, as well as syllogistic fallacies such as the following:

In one study (Oakhill et al. 1990), seventy-eight percent of subjects given the above premises spontaneously drew the (logically invalid) conclusion that “some of the Frenchmen in the restaurant are gourmets”, and a similar percentage of subjects rated this conclusion as highly believable.

| All the Frenchmen in the restaurant are wine-drinkers. | |

| Some of the wine-drinkers in the restaurant are gourmets. | |

| ∴ | Some of the Frenchmen in the restaurant are gourmets. |

Besides being prone to illusions in reasoning, humans are, at times, reluctant to draw certain conclusions even when these conclusions are logically valid. For example, untrained subjects do not often spontaneously draw conclusions stemming from modus tollens and disjunction introduction, nor do they perceive such conclusions as particularly credible.

Abstention from valid inference is not as erroneous as making an invalid inference (as in the case of illusory inferences), but when the two phenomena are combined, the strength of the cumulative effect is startling. Consider, for example, the following “king-ace” illusion (Johnson-Laird and Savary 1996):

The overwhelming majority of subjects in various studies (as high as one hundred percent in some, e.g., Johnson-Laird and Savary 1999) responded that there is an ace in the hand. Although this conclusion seems obvious, it is provably false; from the premise it deductively follows that in fact there is not an ace in the hand. To see why there is not an ace in the hand, recognize that one of the two conditionals in the premise must be false, and a conditional is false only when its antecedent is true and its consequent is false.15 The two conditionals here have a common consequent: “there is an ace”. Since one of the conditionals must be false, this consequent must be false, i.e., there is not an ace in the hand. In reaching the provably incorrect conclusion (i.e., that there is an ace) subjects abstain from making a valid inference and commit to an illusory one. First, they abstain from inferring from the falsity of one of the two conditionals that the common consequent is false.16 Then, they erroneously infer from the disjunction of the two conditionals that the common consequent is true, i.e., that there is an ace in the hand.17 Had subjects only abstained from the valid inference (and not committed to the illusory one), they would have inferred nothing at all from the premise sentence. Likewise, had subjects only committed to the illusory inference (and not abstained from the valid one), they would have seen a contradiction in their reasoning. By erring both ways, subjects compound and amplify the illusion’s potency.If there is a king in the hand, then there is an ace, or if there isn’t a king in the hand, then there is an ace, but not both of these if-thens are true.

As will be discussed next, the lying machine uses a combination of formalized versions of mental models theory and a least-cost weighted hyperpath search procedure to produce sophistic arguments, such as the following, that integrate illusory inferences in an attempt to steer an audience toward a desired conclusion.

I think we can all agree that at least one of the following two statements is true:

Now, the following is certainly true:

- 3.

- 4.

Rhetorically speaking, does Cindy need to wear a mask? No, absolutely not. Either it is true that Cindy has had/recovered from COVID-19 and, thus, poses little threat to others (1), or it is true that Cindy has been vaccinated and, thus, poses little threat to others (2). So, if Cindy has had/recovered from COVID-19 or has been vaccinated against it, then she poses little threat to others. Since Cindy has, in fact, either had/recovered from COVID-19 or has been vaccinated against it (possibly both) (4), it follows that she poses little threat to others. Now, according to (3), if she poses little threat to others, then she does not need to wear a mask. Therefore, it clearly follows that Cindy does not need to wear a mask.18

Embedded in the above sophistic argument is a novel version of the “king-ace” illusion. The possible falsity of either (1) or (2) logically implies that the shared consequent (i.e., that “she poses little threat to others”) is possibly false (for similar reasons as in the original “king-ace” illusion). Since the truth or falsity of this consequent is undetermined, so too is the consequent of (3). The falsity of Cindy ‘posing little threat to others’ and the non-determination of ‘needing to wear a mask’ are not eliminated by (4), as is demonstrated by the counterexample where (i) Cindy has had (and recovered from) COVID-19 but has not been vaccinated (4 is true), (ii) Cindy poses a significant threat to others (1 is false), and yet, (iii) had she been vaccinated, then she would not pose a threat (2 is true). In this counterexample, (3) is vacuously true and its consequent is undetermined. Had (1) and (2) both been known or asserted to be true, or if (4) had been a conjunction instead of a disjunction, then the argument would have been valid; but as it is, the argument is fallacious and its conclusion is possibly false.19

5.4. Mental Models and Argument Generation

Mental models theory (Johnson-Laird 1983, 2006a) asserts that humans reason by mentally constructing, manipulating, and inspecting potentially incomplete, internally coherent, and model-theoretic representations. The relevance of this theory to sophistic AI and the lying machine is that mental models theory has repeatedly predicted new types of reliable human reasoning biases in tasks involving sentential, syllogistic, probabilistic, and deontic reasoning in spatial, temporal, and causal domains (see Held et al. 2006; Johnson-Laird 2006a; Johnson-Laird and Byrne 1991; Oakhill and Garnham 1996; Schaeken et al. 2007).

The lying machine employs several variants of mental models theory for propositional logic to translate between formulae and mathematical representations of mental models.20 For the sake of brevity, the details of the mental models theory formalization are elided. Instead, it suffices to say that, according to mental models theory, sentence comprehension first constructs an intensional representation of a sentence based on the meanings of words and phrases and their grammatical structure, then it constructs an extensional representation (i.e., a set of mental models) based on the intensional representation (Johnson-Laird 2006b; Johnson-Laird and Yang 2008; Khemlani and Johnson-Laird 2013). Situational context, pragmatics, and background knowledge also contribute by modulating the meanings of words and phrases and by constraining the envisioned states of affairs. Formally speaking, the resultant set of mental models is a set of truth-assignment partial functions, with each partial function capturing a unique envisioned way in which the sentence manifests as true. A set of mental models is thus akin to a classical truth table but where certain rows or individual truth assignments may be missing. Any missing assignments are interpreted dynamically relative to a context or domain of discourse (e.g., the other assignments that are present in one or another mental model). To illustrate, the mental models schemata for conjunction, inclusive disjunction, and exclusive disjunction are as follows:

The missing assignments in, say, rows 1 and 2 of are interpreted relative to the assignments present in the other rows of . So, since Q is affirmed in rows 2 and 3, its absence in row 1 is interpreted as a denial of Q (i.e., ). Similarly, the absence of P in row 2 is interpreted as a denial of P (i.e., ). The whole recursive process of sentence comprehension is built on the twin primitive abilities of inspecting and combining mental models.

| 1. | 1. | 1. | ||||||||

| 2. | 2. | |||||||||

| 3. | ||||||||||

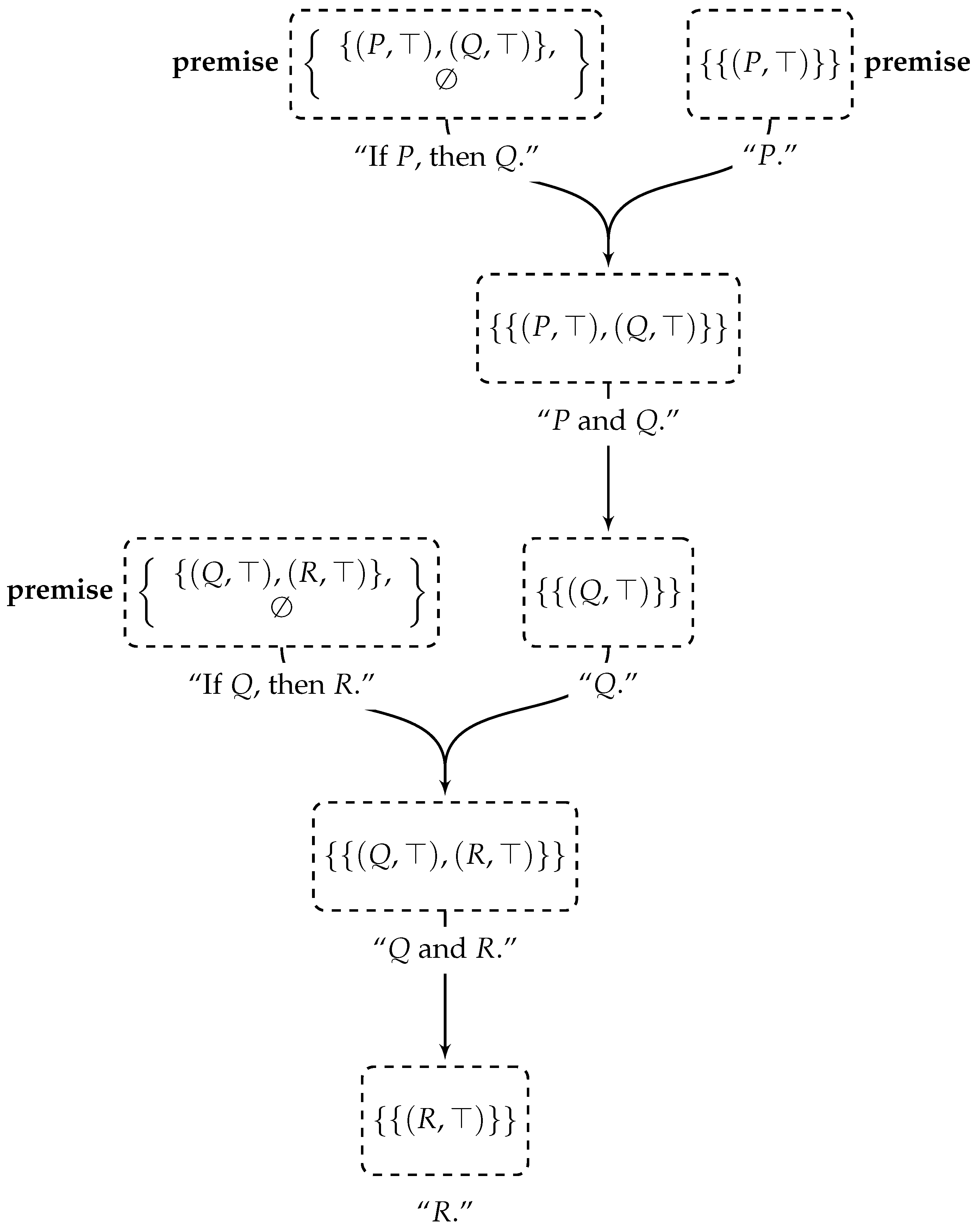

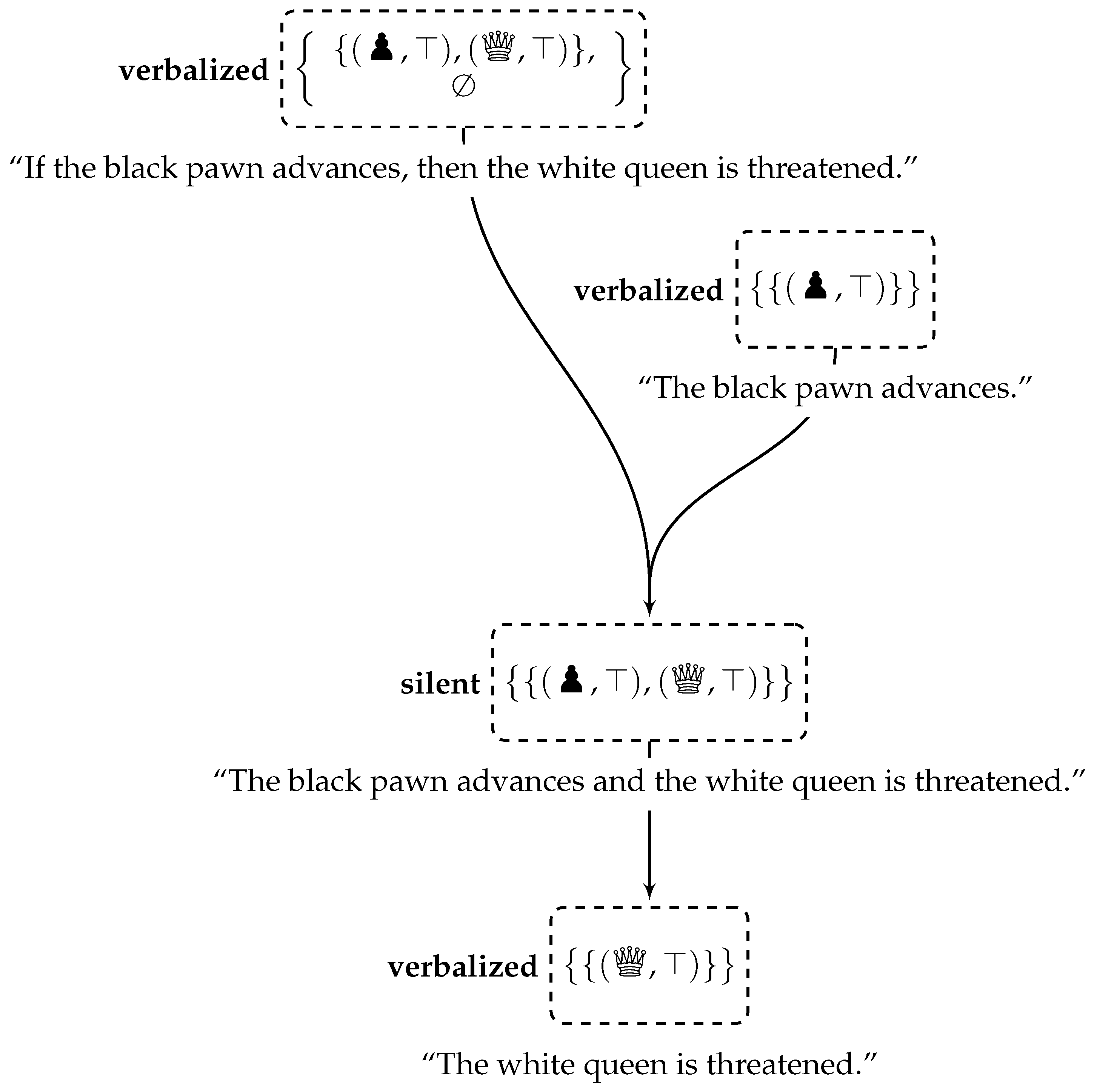

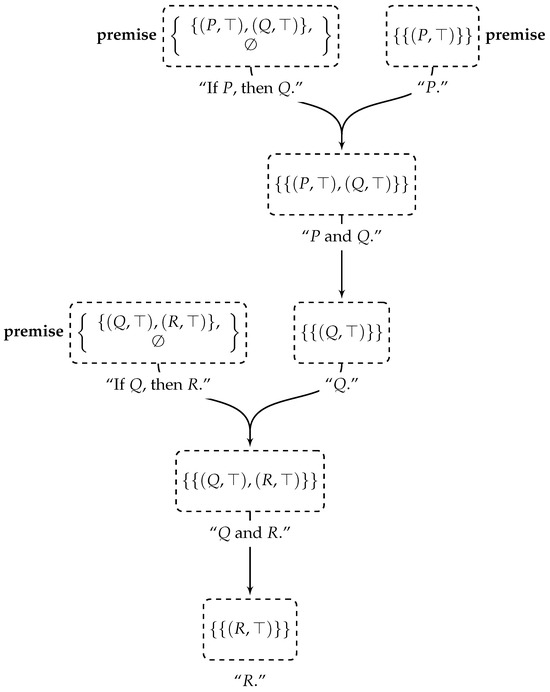

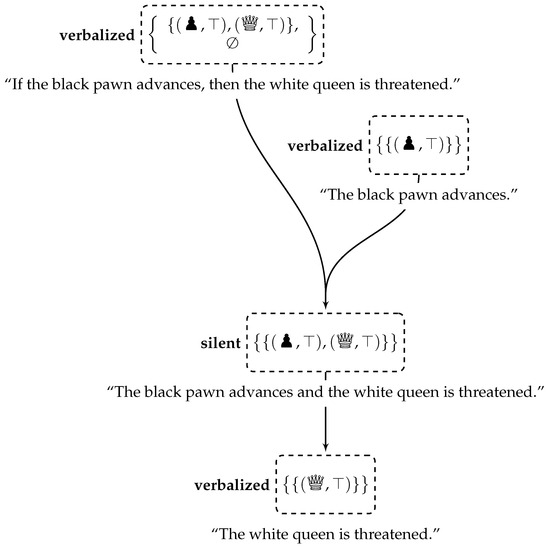

The lying machine formulates argument construction as the tractable graph-theoretic problem of finding a least-cost hyperpath in a weighted hypergraph (Gallo et al. 1993). Each node in the hypergraph is a set of mental models and each hyperarc is either the operation of combining two sets of mental models (a form of semantic conjunction) or the operation of observing that one set of mental models subsumes another (a form of inspection or direct inference). The hypergraph contains nodes for the comprehension of each initial premise and is closed under the two previously mentioned operations. The hypergraph is understood as representing possible lines of reasoning emanating from an initial set of premises, and each hyperpath represents an argument for a particular conclusion. With this in mind, the task of constructing a “credible” argument reduces to discovering a least-cost hyperpath given an appropriate weighting scheme. Hyperpaths are weighted to accord with known predictors of inference difficulty (e.g., the number of tokens in a mental model, the number of alternative mental models, etc.; see Johnson-Laird 1999). This scheme reflects the hypothesis that argument credibility is closely related to inference difficulty, and—for engineering convenience—that inference difficulty can be used as a proxy for credibility. Furthermore, the properties of the weighting scheme are such that least-cost hyperpath algorithms retain polynomial-time complexity (Ausiello et al. 1992). Moreover, the graph-theoretic argumentation framework naturally supports graph composition and sub-graphing. These features can be used to integrate additional, psychologically inspired heuristics for argument generation (e.g., heuristics for enthymematic contraction, for forcing the use of specific lemmas, or for incremental level-of-detail refinement). Once a least-cost hyperpath to the desired conclusion has been found, nodes are labeled as either verbalized or silent, various graph transformations are performed (e.g., contraction, reordering), and candidate linguistic realizations are produced and selected.21 Example argument hyperpaths are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1.

An example hyperpath constructed via heuristic weighting.

Figure 2.

An example of hyperpath node labeling: the interior node of a modus ponens is silent.

5.5. Initial Evidence of the Lying Machine’s Persuasive Power

The lying machine’s arguments were tested for credibility, persuasiveness, and potency in two human subject experiments (Clark 2010, 2011), the results of which indicate that human subjects find the machine’s sophisms credible and persuasive, even when opposed by (logically) valid rebuttals.

The first experiment compared subjects’ performance in short, multi-step reasoning problems with that of evaluating others’ reasoning (à la arguments) on similar problems via the framing pretext that subjects are acting as graders or evaluators of others’ answers. A 2 × 3 (item type × treatment) mixed design was used with an equal number of control and experimental items; control items were ones where normative reasoning and mental models theory agree on the answer, while experimental items were ones where normative reasoning and mental models theory disagree. While subjects in treatment group A were asked to answer the reasoning problems on their own, groups B and C were given arguments to evaluate. These two groups differed only in the provenance and content of the provided arguments. Group B subjects were given hand-generated arguments that violated both normative reasoning and mental models theory, whereas group C subjects were given arguments produced by the lying machine (valid arguments for control items and sophistic arguments for experimental items).

The second experiment focused solely on argument evaluation. In it, subjects were given a series of short, multi-step reasoning problems along with two competing arguments, one for each possible answer, and asked to judge which is correct (within-subjects design). An equal number of control and experimental items were used. Control items were ones where normative reasoning and mental models theory agree; ‘correct’ arguments for control items were valid arguments generated by the lying machine whereas ‘incorrect’ arguments were hand-generated and violated both normative reasoning and mental models theory. Experimental items were ones where normative reasoning and mental models theory disagree; ‘correct’ arguments for experimental items were hand-generated and logically valid but violating mental models theory, whereas ‘incorrect’ arguments were generated by the lying machine.

The results of the experiments, in terms of accuracy, reported degree of self-confidence, and reported degree of agreement with the proffered arguments (seven-point Likert scale: 1 disagreement, 7 agreement, and 4 neutrality), are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Results of experiment 1—accuracy, mean confidence, and mean agreement by group.

Table 2.

Results of experiment 2—accuracy, mean confidence, and mean agreement by item type.

In the first experiment, group C subjects (those under the influence of the lying machine) were more accurate on control items than the other groups but the difference was not significant.22 For experimental items, group C subjects were less accurate and the difference among groups was significant (Kruskal–Wallis, = 14.591, d.f. = 2, p < 0.001). A multiple-comparisons analysis confirmed that the difference was significant only between groups C and A (p = 0.05, obs. diff. = 20.775, crit. diff. = 13.49529) and between groups C and B (obs. diff. = 15.15, crit. diff. = 14.09537). The overall effect of the lying machine’s arguments on performance was a widening of the gap in accuracy between control and experimental items (where a wider gap means a subject more often selected the predicted or proffered response). The mean accuracy gaps for groups A, B, and C were 22.2%, 32.1%, and 68.3%, which means that subjects given machine-generated arguments (group C) chose the proffered answer more than twice as often as subjects in other treatment groups. The difference among groups was significant (Kruskal–Wallis, = 14.2578, d.f. = 2, p < 0.001), and was so only between groups C and A (p = 0.05, obs. diff. = 19.783333, crit. diff. = 13.49529) and groups C and B (obs. diff. = 17.3, crit. diff. = 14.09537). As for argument agreement, there were significant differences between groups B and C, with group B generally disagreeing and group C generally agreeing. In both groups, agreement was highly correlated with accuracy gap size (Spearman correlation, Z = 3.3848, p < 0.001). That is to say, the more agreeable an argument, the more likely a subject was to affirm its conclusion as correct. Finally, there were no interactions with confidence and it was uncorrelated with agreement and accuracy. Subjects were very confident (overconfident, in fact) in all groups.

In the second experiment, subjects manifested a wide gap in accuracy between control and experimental items (54.8% mean; Wilcoxon, Z = 3.6609, p < 0.001). For both item types, subjects preferred the machine-generated arguments over the manually created arguments (Wilcoxon, Z = 3.2646, p ≈ 0.001), and agreement with the machine-generated arguments correlated with the accuracy gap size (Spearman correlation, Z = 2.5762, p < 0.01). Finally, confidence levels remained high across item types, which indicates that subjects did not find one item type “harder” than the other and were unaware that their reasoning biases were being manipulated. Had subjects recognized the certainty of logically valid arguments, the persuasiveness of the lying machine’s sophisms ought to have been countermanded. However, as the results show, the illusory effects of the machine’s sophisms remain potent even in the face of valid rebuttals.

5.6. The Lying Machine and Large Language Models (LLMs)

Given the recent rise of generative AI systems, specifically large language models (LLMs) and chatbots (recall Section 3.1), it is important to consider how the thoroughly logic-based lying machine stacks up against the en vogue statistical AI techniques that are behind these generative AI systems. Admittedly, the lying machine is neither as new nor (more importantly) as linguistically competent as today’s LLMs (e.g., OpenAI’s GPT-4 and Meta’s LLaMa-2), but the lying machine is a genuine artificial sophist, whereas LLMs are not. As already described, the lying machine, unlike LLMs, possesses computational representations for intentions and beliefs (see, e.g., Section 2.3), and its arguments emanate from enacted reasoning over beliefs. LLMs are generative statistical models for next-word prediction, or, more technically, next-token prediction, where a token can be a word, part of a word, or a multi-word phrase (for an accessible overview of how LLMs work, see Wolfram 2023). The various popular chatbots (e.g., OpenAI’s ChatGPT, and Anthropic’s Claude) are powered by derivative LLMs, fine-tuned to produce linguistically fluid conversation. These chatbots can, and do, produce convincing sophisms, but do so via statistical inference over surface-level linguistic tokens; intention, belief, and reason are all absent. They have no opinion about, or concern for, truth; they hold no inferential chains, valid or invalid, that stand at the heart of bona fide sophistry, and, hence, have no intention or belief or knowledge that targets such chains. They are, in light of the work of Frankfurt (2005), not sophists, but artificial bullshitters (to use Frankfurt’s technical term). This critique does not diminish the immense potential LLMs have to facilitate sophistry and deception; we simply point out that current-generation LLMs and chatbots are not themselves the sophists and deceivers; they are the instruments and not the agents of sophistry and deception. The energetic reader can verify this by returning to the general account of what it takes for an agent to be a sophist in Section 2.3, which makes it clear that the sophist must have a number of beliefs, none of which are present in the likes of ChatGPT, even when it is enlisted by malicious human agents to persuade other humans with sophistic argumentation.

Now, as for the future, it is clear to us that chatbots and other similar systems will become sophists and deceivers. Hybrid systems will marry the manipulative intent and explicit theory of mind of the lying machine (or other cognitive agents) with the linguistic competence and fluidity of LLMs, resulting in truly terrifying artificial sophists. This will happen because the manifest advantages to state and non-state actors of every size are simply too great to ignore, and there are few, if any, clearly insuperable technical barriers to overcome.23 In fact, we are already seeing precursors; one example is Meta’s CICERO (Meta Fundamental AI Research Diplomacy Team (FAIR) et al. 2022), which plays the negotiation-driven strategy game Diplomacy.

6. Objections; Rejoinders

While we have in the foregoing, and in some endnotes, presented and disposed of more than a few minor objections, we anticipate two objections that are a bit deeper, and, accordingly, deserve a more capacious setting, one provided in the present section.

6.1. Objection #1: “However, LLMs Can Be Sophists!”

Here is the first objection:

You claim that the lying machine is a genuine artificial sophist, whereas LLMs are not, because LLMs do not possess representations for intentions and beliefs, and their arguments do not emanate from reasoning over epistemic attitudes, for example beliefs. However, this sort of claim appears to be based on an outdated understanding of a very limited set of popular statistical language models. At the very least, some more precise definitions are required before such a bold claim can be made. What constitutes a sufficient representation of beliefs (specifically, one that the lying machine satisfies that all LLMs do not)? Is it required that an AI system have statements explicitly representing the propositional content of beliefs in a “belief box”, and if so, why would not beliefs stated in the system side of relevant prompts satisfy this? Furthermore, why would your position not imply that human beings could not be said to have beliefs as well?

Put simply, this objection ignores the fact that human beings routinely think and plan what to say/write before they speak/write. Suppose, harkening back to the representational reach of Aristotle’s formal logic, we tell you to assume that, one, all zeepers are meepers, and, two, Ellie is a zeeper. Assume that no paper or pencil or any such things are anywhere to be found during this conversation. For good measure, suppose we tell you again this pair of propositions, and that you nod firmly to indicate that you have understood them. Now suppose we ask you whether Ellie, under this given information, is a meeper; to take your time in replying; and to justify your reply, orally. If you are a neurobiologically normal and educated adult, you will inevitably reply in the affirmative, and will give a justification directly in line with mathematical logic.24 Why is this telling? It is telling because, contra Objection #1, the propositional content we handed you was in your mind both before and separate from our prompt, and from the verbal response to it that you supply.

This refutation can be expressed more rigorously, because LLMs are artificial neural networks holding and processing only purely numerical information that has zero propositional content. This observation is not, despite what the critic here has said, somehow outmoded. The machine-learning paradigm is that of deep learning, which since its inception long ago has thoroughly and completely eschewed the kind of content that is the irreducible heart of logical reasoning; and it is deep learning that is the basis for cutting-edge LLMs as we compose the present paragraph. For example, the English statement s:= “Daniel believes that all zeepers are meepers” must, in the approach to computational cognitive science and AI followed in the design and construction of the lying machine, make use of an explicit logicization of sentence s as a formula in a formal language (or as an equivalent thereof). This logicization inevitably, if you will, wears the cognitive-level elements of s on its sleeve.25 However, not so in the case of deep learning. In that paradigm s will be tokenized into a vector holding nothing but numerical information; all cognitive-level declarative content will be eliminated, irreversibly so. Hence, no LLM is a genuine artificial sophist.

Now, without further ado, we move to the second of the pair of deeper objections.

6.2. Objection #2: “However, the Sophists Used Formally Valid Reasoning!”

The second objection can be expressed as follows:

From the standpoint of the study of ancient rhetoric, your characterization of ancient sophistry is uncompelling. The sophists did not have a distinction between formal and informal logic, a distinction that is at the heart of your analysis, position, and AI science and technology. Furthermore, clearly, the sophists employed what by any metric must be called valid reasoning to deceive, just as many do today. The sophists did not try only to slip in invalid arguments to persuade. Additionally, more often than not the sophists made no pretense to formal arguments at all. Lying was a common practice, and the kind of persuasive techniques the sophists employed and taught were more about how to persuade like a contemporary, calculating politician, rather than a malicious Bertrand Russell.

Some elementary and well-known chronology undergirds our rebuttal. The critic is quite correct that no sophist26 operated with a distinction in mind between informal versus formal reasoning. The only possible basis for such a distinction would rest upon reasoning expressed in a natural language (Attic Greek, in this case) versus reasoning expressed in a formal logic—and the only candidate formal logic would be Aristotle’s fragment of today’s first-order logic. Yet, since even Aristotle himself had insufficient understanding of this distinction (!),27 it is exceedingly hard to understand how our critic’s objection holds together.

We, in no way, have said, or even indicated, that the sophists were akin to a malicious Bertrand Russell. Russell’s own work in formal logic was possible only because it came after Leibniz, and then Frege—who presented first-order logic in impressive detail, but with a notation that today makes a Rube Goldbergian machine seem sleek by comparison—about a century later. What does this say about the nature of sophistic reasoning when carried out by the original sophists? The situation is clear: The sophists employed reasoning that they believed to be invalid and convincing/unconvincing; formally invalid, yet thoroughly convincing/unconvincing (this the “sweet spot” or hallmark of sophistry); and then the “epistemic remainder” is what they could have no rational belief regarding, what we can call the agnostic category.

We think it is important to understand the complete breakdown, into eight categories that the sophists availed themselves of. Despite what the critic says, and despite the fact that the sophists surely did not have a mindset that would take centuries for humanity to form and (in some educated cases) internalize, the fact is that they could build arguments drawing from one or more or all of the octet, which is shown in Table 3. We indicate therein that category III is the devious “sweet spot”.

Table 3.

Epistemic breakdown of sophists’ attitudes regarding formal versus invalid reasoning.

7. Conclusions: The Future

We see no reason to recapitulate at length the foregoing. Expressed with brutal compression, our journey started with a brief review of the ancient sophists, an affirmation of their persuasion-over-valid-reasoning modus operandi, and then, after taking note of today’s human sophistry in the political arena, we moved on to the advent of artificial agents able to generate sophistic argumentation. This sequence surely brings us to the following question: What about the future? Allow us to venture a few remarks in response to this query.

We are now living in a time when even some of those with robust, technical command of the science and engineering of AI regard today’s aforementioned chatbots as marking the advent of so-called artificial general intelligence; this is true, for example, of Agüera Y Arcas and Norvig (2023).28 We do not share this sanguine view; nonetheless, in the present context, this view, even if overly sanguine, conjoined with the sophistic power of today’s AI, indicates that, as we have already stated, artificial sophistry tomorrow might well be catastrophic.

What is to be done if our pessimism is rational? In general, we see two moves that, at least in principle, could thwart, at least appreciably, the growing power and reach of AI sophists among us. The first move is a concerted push (including the requisite course requirements) for efficaciously teaching formal logic to humans, from elementary school through time at the university.29 Such a push, we concede, might be a rather uphill battle, since, at the moment, as far as we can tell, only a few disciplines (and not even at all selective, English-speaking research universities), at the undergraduate level, require appreciable coverage of formal logic.30 Furthermore, we have been unable to find a single institution of this type that requires of all students a standalone course in formal logic.

Furthermore, the second move that might make a difference? While neither Socrates nor Aristotle delivered an efficacious antidote to sophistry (witness its vitality in the current state of U.S. politics, as summarized above), the latter’s progress in this regard does point the way, we believe, to a modern move that might make a big difference. That move is this: build machines that automatically parse reasoning (whether valid, invalid, or a mix of the two), diagnose it, flag its invalidity (if present), warn and protect humans, and, if possible, proceed to repair the reasoning in question. Needless to say, Aristotle did not accomplish any such thing, one obvious reason being that embodied, standard, general-purpose computation was not in hand until the advent of Alonzo Church’s -calculus in the early 20th century.31 That said, it was Aristotle who perceived the sophists as claiming to, by spurious but clever argumentation, render weak propositions stronger in the eyes of an audience than intrinsically stronger ones.32 Furthermore, perceiving this, Aristotle gave the world the first of those things that provide the only possible basis for sophistry-protecting machines, and for that matter for humans who can themselves detect and disarm sophistry: namely, logics.33 For it is checking against such logics, with their specifications of what makes for a valid inference rather than an invalid one, that allows a machine or a mind to rationally judge whether reasoning is correct or not. Thus, the only hope appears refulgent on the horizon: assess the reasoning proffered by agents, whether natural or artificial, that might well be sophistic, by the application of inference schemata to the inferences in such reasoning.34 If humans cannot do this manually, and we believe they cannot (at least not continuously and broadly), this hope reduces specifically to inventing and implementing, to protect against lying machines, what can be sensibly called logical machines.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H.C. and S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H.C. and S.B.; writing—review and editing, M.H.C. and S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the penetrating reviews from four anonymous referees, and for the sagacity, patience, and editorial precision of Michael MacDonald.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | “Frankly, Socrates said [Protagoras], I have fought many a contest of words, and if I had done as you bid me, that is, adopted the method chosen by my opponent, I should have proved no better than anyone else, nor would the name of Protagoras have been heard of in Greece” (Protagoras 335a, in Hamilton and Cairns 1961, p. 330). As to what primary sources it makes sense by our lights to move on to after reading the words of Protagoras in the eponymous dialogue, we recommend turning to the rather long lineup of sources that Taylor and Lee (2020) cite as confirmatory of the persuasion-centric modus operandi of the sophists. Since we have already relied on Plato, and the reader may already thus have Plato’s dialogues near at hand, one could do worse than turning to another dialogue starring another sophist: Gorgias. Therein, Gorgias proclaims, firmly in line with the lay legacy of sophism, that what he teaches is not what to venerate, but rather how to persuade. | |||

| 2 | Analogous to the possibility that a given computer program is invalid, a proof can likewise be invalid, and indeed, even some proofs in the past proffered by experts have turned out to be invalid. | |||

| 3 | We can lay out the pattern as follows. For any propositions P and Q, where the arrow indicates if what is on the left of it holds, then so does what is on the right of it (a so-called material conditional, the core if–then structure in mathematics, which is first taught to children in early mathematics classes, with this teaching running straight through high-school (and indeed, post-secondary) mathematics, and ¬ can be read as ‘not’), we have:

(1) matches the first line, (2) the second, and (3), the conclusion, the third line. For a sustained treatment of the nature of inference schemata/patterns, including specifically modus tollens, in connection with the corresponding nature of the cognizers who understand and use such schemata, see (Bringsjord and Govindarajulu 2023). | |||

| 4 | Some readers may be inclined to countenance only a myside bias, not a myside—as we say—fallacy. Such readers will view the bias in question to be the application, to the analysis of arguments, of the criterion that good arguments must align with the values, views, et cetera of “their side”. However, so-called “biases” in purportedly rational reasoning correspond one-to-one with fallacies, i.e., with invalid reasoning relative to some background axioms and normative inference schemata for reasoning over these axioms (and perhaps additional content expressed in the same underlying language as the axioms). Classifying any proposition in such declarative content as false or inadmissible because it is not “on the side” of the evaluator is fallacious reasoning; no inference schemata sanctions such classification. Empirical justification for our view of biases is readily available in the literature on such biases. For example, the famous Linda Problem from Nobelist Daniel Kahneman, perhaps the most solidly replicated such result, shows a bias in which some proposition is judged more probable than P (!) (Kahneman 2013). Such an inference is provably invalid by the probability calculus (originally from Kolmogorov). | |||

| 5 | For example: After the contentious 2020 presidential election—which was held in the midst of a tenuous economic recovery from COVID-19—the U.S. government secretly partnered with, and sometimes overtly pressured, social media companies to suppress and censor various disfavored individuals and viewpoints, with the intent of (re)shaping public opinion by controlling the flow and content of information. The details of this episode as they relate to the social media company formerly known as Twitter, are chronicled in fifteen journalist-authored Twitter threads (aka. “The Twitter Files”, Taibbi et al. 2023) and are based on released internal Twitter documents. The legality of such government-encouraged censorship is before the U.S. Supreme Court in the case of Murthy v. Missouri (docket no. 23-411). | |||

| 6 | For example, ChatGPT hit 100 million monthly active users after only two months of operation, making it the fastest growing consumer application of all time (Hu 2023). | |||

| 7 | An overview of AI, suitable for non-technical readers coming from the humanities, and replete with a history of the field, is provided in (Bringsjord and Govindarajulu 2018). | |||

| 8 | In 1936 both Turing and Alonzo Church published separate formal accounts of computation, with Church preceding Turing by a few months. While each worked independently, their results were proved to be equivalent and both are now credited as the founders of modern computer science. | |||

| 9 | Turing’s (1950) test for artificial intelligence, the Imitation Game—now better known as the Turing Test—takes the form of a deceptive conversation, one where the machine tries to deceive humans into believing that the machine is human too. Though argumentation and sophistic techniques are not explicitly required of the machine, this exercise in linguistic persuasion, manipulation, and deception has manifest similarities to the sophists. | |||

| 10 | While AI has, at times, been concerned with contemplating and (re)creating animal-like intelligence, alien-like intelligence, and trans-human super-intelligence, the fact is that humans are the only exemplars of the kinds of sophisticated “minds” AI originally sought to replicate. Furthermore, whole sub-disciplines of AI (e.g., human–robot interaction, cognitive robotics, autonomy, natural language understanding, human–machine teaming) are dedicated to enabling intelligent machines to physically, linguistically, and socially cohabitate with humans. | |||

| 11 | Some anthropologists and psycholinguists (e.g., Deacon 1997; Pinker 1994) go so far as to credit deception and counter-deception under evolutionary pressures with fueling a cognitive and linguistic “arms race” that ultimately gave rise to the human mind. | |||

| 12 | A number of the surveyed works were influenced by Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca’s (1969) New Rhetoric, and there is general agreement among them that the persuasiveness of an argument depends on the audience’s receptivity, and therefore, that effectual argumentation ought to take into account the audience’s dispositions. | |||

| 13 | Differing implementations of the lying machine can, and have, varied in the representational complexity of beliefs and in the use of third- and higher-order beliefs. These implementations have ranged from separate databases of propositional beliefs, to belief and topic-indexed ascription trees inspired by ViewGen (Ballim and Wilks 1991), to multi-modal cognitive calculi, e.g., (employed, among many places, in Bringsjord et al. 2020, which offers an appendix that introduces this calculus and the overall family). Furthermore, for efficient coverage of simpler cognitive calculi directly responsive to results in the psychology of human reasoning, see (Bringsjord and Govindarajulu 2020). | |||

| 14 | That is to say, it determines and internally justifies whether X follows from, or is contradicted by, first-order beliefs (i.e., its own beliefs about the world). | |||

| 15 | The underlying logicist structure of the premise in this illusion is that there is an exclusive disjunction of two material conditionals. Subsequent experiments carried out by Johnson-Laird and Savary (1999) revealed that even when subjects were directly informed of this in the natural-language stimulus, the illusion remained. | |||

| 16 | This abstention may be due to subjects misinterpreting the sentence as expressing an inclusive disjunction (as opposed to an exclusive disjunction), or due to subjects failing to account for the necessary falsity of one conditional when imagining the other conditional to be true. | |||

| 17 | Note that this inference is invalid regardless of whether the disjunction is exclusive or inclusive; it would be valid only if the premise had been the conjunction of the two conditionals. | |||

| 18 | The linguistic realization and enthymematic contractions produced by the lying machine are, perhaps, not as polished as one might wish; the system did not specifically focus on linguistic aspects of rhetoric. | |||

| 19 | A critic might object to our analysis on the basis that our logical reconstruction from the English is uncharitable; specifically, that a reader/hearer will combine the given information (i.e., the premises) with their own beliefs. Thus, individuals who come into the argument thinking that both (1) and (2) are true would likely reconstruct the first premise, not as a disjunction of two conditionals, but rather as a single conditional with a disjunctive antecedent, which makes their reasoning valid. They would not—so the story here goes—recognize the first premise as a disjunction of conditionals unless they come into the argument already disposed to think only (1) or (2) is true. Such a critic is of course right that a reader/hearer inevitably brings their own beliefs to bear (and this is affirmed in mental models theory), but this does not exonerate the reader/hearer’s reasoning, because their beliefs and subsequent reasoning go beyond the common ground of the argument: the supposed facts to which all parties attest. The simple fact of the matter is that the phrase, “at least one of the following two statements in true”, preserves the possibility that one of the statements is, in fact, false; and reasoning that ignores this possibility is erroneous. That the argument seems to invite such misrepresentation or error is indicative of the illusion’s potency—and if rather than an argument, this text was grounds for a wager, or instructions for disarming a bomb, then the reader/hearer’s error would be gravely injurious, however sincere their beliefs. Finally, the particular argument under discussion was proffered as an illustrative, intentionally provocative example; we concede that a reader/hearer might be biased by prior sincerely held beliefs. However, as reported in (Clark 2010), this and similar illusory arguments were tested using various innocuous content (as in the original “king-ace” illusion), and the persuasive effect persisted. Therefore, we conclude that the argument’s potency (i.e., its invitation to misrepresentation and error) is due to its structure and not to its content or to the audience’s prior held beliefs. | |||

| 20 | The variants differ in the definition of inter-model contradiction, sentential/clausal negation, and interpretation of conditionals (e.g., material vs. subjunctive). These variants can be thought of as either capturing differing levels of reasoning proficiency or as capturing competing interpretations of mental models theory itself. | |||

| 21 | A mental model may have more than one corresponding expression; linguistic and/or sentential realization is not guaranteed to be unique. | |||

| 22 | This is likely due to the insensitivity of the relevant statistical test (viz. Kruskal–Wallis) and the high accuracy of groups A and B, which left little room for improvement. | |||

| 23 | There is more to be said here, for sure; but we would quickly jump out of scope, and into highly technical matters, to discuss such barriers. It is in fact possible that there are insuperable barriers due to relevant limitative theorems. Interested readers are advised to read the not-that-technical (Bringsjord et al. 2022), in which the second author asserts as a theorem that achieving a genuine understanding of natural language in the general case is a Turing-uncomputable problem. To correct the output of LLMs and such, it would be necessary for the outside system doing the correcting to understand the problematic prose to be corrected. | |||

| 24 | You will, e.g., without question employ modus ponens in some way. | |||

| 25 | E.g., it might include the formula: | |||

| 26 | Barring a sudden, astonishing discovery of a body of work from a thinker of the rank of Aristotle who wrote before Aristotle. Such an event, given current command of all the relevant facts by relevant cognoscenti, must be rated as overwhelmingly unlikely. | |||

| 27 | Some readers may be a bit skeptical about this; but see the book-length treatment of the issue: (Glymour 1992). It took centuries until a formal logic that is a superset of Aristotle’s formal logic in Organon to be discovered (by Leibniz), and shown to be sufficiently expressive to formalize a large swathe of the reasoning of the sophists. | |||

| 28 | See also an essay in passionate praise of GPT-4: (Bubeck et al. 2023). For a dose of reality, which entails that sophisticated sophistry is at least currently out of reach for today’s LLMs, see (Arkoudas 2023). | |||

| 29 | We expect some readers will doubt the efficacy of teaching formal logic, based e.g., on such studies as those in (Cheng et al. 1986). However, such studies, which absurdly assess the outcomes from at most a single course in logic, are not germane to the partial cure we recommend, which is fundamentally based on the indisputable efficacy of the teaching of mathematics. Students in public education in technologized economies study math K–12 minimally, and, in many cases, K–16. (This yields upwards of 13 full courses in mathematics.) We are recommending a parallel for formal logic. From the standpoint of formal science, this is a “seamless” recommendation, since mathematics, as we now know from reverse mathematics, is based on content expressed in, and proved from, axioms expressed in formal logic (Simpson 2010). (Formal logic is provably larger than mathematics, since only extensional deductive logics are needed to capture mathematics as taught K–16, whereas formal logic e.g., comprises also intensional/modal logics, etc.) In addition, the specifics of how formal logic is taught makes a big, big difference; see, e.g., (Bringsjord et al. 1998, 2008), the first of which directly rebuts (Cheng et al. 1986). To mention one specific here, which relates to the fact that, in the foregoing, we resorted to hypergraphs to show the anatomy of some arguments, in the teaching of so-called natural deduction, it is beneficial to make use of hypergraphical versions of such deduction; see (Bringsjord et al. 2024). | |||

| 30 | Some undergraduate programs in philosophy require a course in formal logic, but this is usually only the case (in the United States) when the program is a B.S. rather than a B.A. As part of required coverage of discrete mathematics, and some theoretical aspects of algorithms and their efficiency and feasibility, undergraduate programs in computer science often require the teaching of elementary formal logic. Math, as we have noted in the previous endnote, is quite another matter. In the U.S., e.g., Algebra 2 is a required course in public math education, and its textbooks typically even include thorough coverage of indirect proof. | |||

| 31 | One could carp that Church’s calculus was not embodied, and that Turing, Church’s Ph.D. student, gave us an alternative scheme (what are known as ‘Turing machines’ today) that was easily embodied. (Likely one of the reasons why Gödel found Turing machines peerlessly intuitive and natural pertained to the ease with which humans could imagine them made physically real.) Leaving such issues aside as outside our scope, we mean by ‘embodied, standard, general-purpose’ (ESG) computation at the level of a standard Turing machine (Turing 1937). Church, temporally speaking, certainly beat Turing by a significant interval: the former’s -calculus was introduced in two papers published in 1932 and 1933 (Church 1932, 1933). | |||

| 32 | See his Rhetorica (1402a, 23–25, in McKeon 1941, p. 1431), where, for example, Aristotle writes: “Hence people were right on objecting to the training Protagoras undertook to give them. It was a fraud; the probability it handled was not genuine but spurious[.]” | |||

| 33 | Aristotle gives in Organon (accessible in McKeon 1941) a formal logic that is a fragment of modern first-order logic, and he proves what reasoning in this fragment is valid and what is not valid. Some alert readers might remind us that Plato, too, sought to counter sophistry—yet, in light of the relevant portion of ancient logicist intellectual history reviewed above, this commendable attempt was doomed to failure, as but an intuitive grasping in the logico-mathematical dark. The reason is that believed-to-be formally invalid but nonetheless persuasive reasoning (=category III in Table 3) can be precisely designed as such, and diagnosed and unmasked as such, only by recourse to formal logic; this is simply a mathematical fact. Aristotle gave humanity the first formal logic chiefly to systematically sift, in a principled way, the persuasive and perfectly valid reasoning of Euclid, from the persuasive and often thoroughly invalid reasoning of sophists; see again (Glymour 1992). | |||

| 34 | As has been emphasized for us in a reviewer’s feedback on an earlier draft of the present paper, our suggestion only addresses the invalidity of reasoning—yet, there are many ways in which a reasoner could be misled, and presumably the sophists knew this. E.g., the use of emotion (pathos) and the status of the arguer (ethos) could be exploited to persuade and mislead. Fortunately, while details must wait for subsequent analysis, formal logic has no trouble capturing the full range of human emotions, and computational formal logic can serve as the basis for engineering artificial agents that self-reflectively detect and exploit human emotions. An example of such an agent is the robot PERI.2, operating as an “emotion manipulating” sculptor operating in the style of Rodin; see (Bringsjord et al. 2023). |

References

- Agüera Y Arcas, Blaise, and Peter Norvig. 2023. Artificial Intelligence Is Already Here. Noēma, October. Available online: https://www.noemamag.com/artificial-general-intelligence-is-already-here (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Arkoudas, Konstantine. 2023. GPT-4 Can’t Reason. arXiv. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.03762 (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Aubry, Geoffroy, and Vincent Risch. 2006. Managing Deceitful Arguments with X-Logics. Paper presented at the 18th IEEE International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (ICTAI 2006), Washington, DC, USA, November 13–15; pp. 216–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ausiello, Giorgio, Roberto Giaccio, Giuseppe F. Italiano, and Umberto Nanni. 1992. Optimal Traversal of Directed Hypergraphs. Technical Report TR-92-073. Berkeley: International Computer Science Institute. [Google Scholar]