This article builds on Kochalka’s reflections on identity by placing them in conversation with existing work on embodiment in the disciplines of identity social studies and comics studies to explore the narrative function of lists in several autobiographical graphic illness narratives. After detailing why visual embodiment is particularly complex in these illness narratives, it examines key examples of poetic lists in autobiographical graphic illness narratives to ask how they communicate the ill subject’s changing embodied realities. Throughout, it suggests that lists that feature prominently in autobiographical graphic illness narratives do not give order to the lived experience of illness and its impact on identity. On the contrary, they are narrative tools used to address the ill subject’s varied, processual, and ambiguous embodied identity.

1. Embodiment

The three aspects Kochalka lists in his deceptively simple four-panel autobiographical comic reflect recent conceptualizations of embodiment as shaping both physical and cognitive processes that are central to formulating a strong, coherent sense of self. Embodiment theory holds that “every human stands in a unique and exclusive relationship to her own body” (

Buckley and Hall 1999, p. 191) and that “the boundaries of our embodiment are determined by something about how we experience our bodies as sites of agency and subjectivity” (

Aas 2021, p. 6511). The body’s sensorimotor interaction with the physical, social, and cultural environment is not only essential to how one thinks and communicates, but also to how one comes into knowledge of one’s own self. Accordingly, cognition is recognized to be utterly dependent upon “the kinds of experience that come from having a body with various sensorimotor capacities”, which “are themselves embedded in a more encompassing biological, psychological, and cultural context” (

Varela et al. 1991, p. 173). Embodiment announces the body’s position in the world, the parameters in which the body moves, and it is through this positionality—this embodied experience of the physical world—that a sense of self is formulated. As Kochalka’s final listed item confirms—“your existence in the minds of others”—such an experience is not a solitary one; rather, it involves others that interact with the embodied self, exerting influence over its embodiment and, by extension, its understanding of the self.

Since Judith Butler’s seminal work on gender that accentuates subversion, regulation, and embodiment, much critical autobiographical writing has theorized the intimate connection between subjectivity, identity, and the body (see

Egan 1999).

Paul John Eakin (

1999) traces the centrality of the body in autobiographical discussions of identity to conclude that “The life of the self is the life of the body—there is no other” (18). The link between the body and the self is particularly evident in autobiographical comics where the protagonist’s body, which features repeatedly and oftentimes differently throughout the text, serves as a canvas for communicating the subject’s physical and emotional realities. In autobiographical comics, identities and bodies are inseparable, overtly and often self-reflexively intertwined. Comic theorists generally agree that the “nature of graphic texts […] promotes a particular kind of embodied understanding of the events represented, along with access to the emotional worlds of the characters” (

Davis 2015, p. 253). In autobiographical comics, multiple bodily representations of the autobiographical subject and the bodily knowledge of self that makes this possible grant access to an individual identity and its subjective experience of the self (see

El Refaie 2012b;

Miller 2007;

Versaci 2007). Indeed, the autobiographical subject’s sense of self, its consciousness and subjectivity—in short, its embodiment—is the central focus of autobiographical comics.

Embodiment becomes stylistically and thematically complex in autobiographical graphic illness narratives—autobiographical comics in which the autobiographical subject relates their personal experience with mental or physical illness—because they feature an autobiographical subject that grapples with changing physical and emotional experiences of the self. As in other autobiographical comics, the body is literally “on the page” (

Chute 2010, p. 10), but when the focus is on an ill body or mind its bold assertion of an embodied sense of self is fraught with the vulnerability and unpredictability of illness (see

DeFalco 2016, p. 225). Caught up with and in its lived experience of illness, the autobiographical self in autobiographical graphic illness narratives engages in a complex pictorial embodiment that addresses the “ever-shifting process of lived experience” that is especially accentuated through illness (

El Refaie 2019, p. 20). In them, the ill subject struggles to understand their new lived reality and navigates towards a new sense of self through its own embodied experiences and imagined understandings of self, but also through how their embodied experience triggers new formulations of self in the imagination of others. Pictorial embodiment in autobiographical graphic illness narratives thus raises for explicit consideration Kochalka’s three aspects that make one whole.

Furthermore, in autobiographical graphic illness narratives, pictorial embodiment is often tangled up in lists, which share several characteristics with Kochalka’s three-item list as presented in his four-panel comic, including enumeration and grouping of items, fragmentary and simple form, and simplification or reduction in content. Defined as a set of items assembled in a formal unit (see

Belknap 2000b, p. 35;

Fludernik 2016, p. 309), lists are often used in graphic illness narratives to give expression to the ill subject’s keen awareness of self-emergence and evolution, messiness and fragmentation. Lists figure prominently in Ken Dahl’s

Monsters (

Dahl 2009), Brick’s

Depresso (

Brick 2010), Ellen Forney’s

Marbles (

Forney 2012) and

Rock Steady (

Forney 2018), and Leslie Stein’s

Bright-Eyed at Midnight (

Stein 2015), to name just a few autobiographical graphic illness narratives that rely on lists to narrate the autobiographical subject’s unpredictable, ever-changing sense of self. The autobiographical subject of Ellen Forney’s graphic illness narrative

Rock Steady: Brilliant Advice from my Bipolar Life offers some insight into why lists feature so prominently in graphic illness narratives. Reflecting on the making of lists, she reveals that they are an attempt to “transform a swirling mess into neat packets of information” (

Forney 2018, p. 69). Lists seemingly give order to thinking; they help to “pin it down” (

Forney 2018, p. 69) or, at the very least, they

give the impression to the autobiographical subject and to readers of giving order to or pinning down the messiness that is living with illness.

Anne Rüggemeier (

2018) has drawn critical attention to how practical lists are often remediated in graphic illness narratives, arguing that lists present readers with a form of representation that counters the “hand-drawn bodies and the often messy page layouts” of graphic illness narratives (56). By way of example, one may consider the careful management and arrangement of complicated information that guides the use of practical lists in

Tangles: A Story about Alzheimer’s, My Mother and Me (

Leavitt 2012), Sarah Leavitt’s graphic memoir about her experience with her mother’s Alzheimer’s. In it, lists present neatly organized items about a specific topic related to the ill subject, including “Things that Mom liked to carry around” (84) and “Questions” (88). The practical list’s organized mode of presentation frames the listed items in a way that accentuates thoughtful thinking, organization, and/or evaluation, which, in turn, reveals the list maker’s “critical ability and

savoir faire” (Hamilton qtd. in

Poletti 2008, p. 338). In

Tangles, practical lists result from Sarah’s attempt to order her thoughts and observations about a reality that is otherwise confusing and incoherent or just full of tangles. They communicate the character’s lived experience of her mother’s illness in a pragmatic, straightforward way.

However, as Rüggemeier reminds us, although processes of calculating, stocktaking, and accounting guide the practicality of the practical list, its re-presentation or remediation in graphic illness narratives often communicates confusion and chaos, rather than understanding. Examining a panel from Brain Fies’

Mom’s Cancer (

Fies 2006) in which Brian reads a book against a backdrop of photographed journal articles (24), Rüggemeier proposes that although the practical list of articles assembles and communicates information, the list’s form—the disorderly arrangement of the articles that extends beyond the page’s border—strongly suggests that a satisfactory understanding cannot be reached. The list announces its and, by extension, Brian’s inability to make the immense amount of information meaningfully cohere, much less grant insight into how to cure mom’s cancer. A lack of understanding also informs the practical lists created by medical professionals that abound in

Mom’s Cancer. As Rüggemeier shows through several examples, by categorizing and simplifying illness and the ill subject’s experience of illness, the lists created and used by medical practitioners engage in a knowledge-making process that polices identities even to the point of effacing “the ill and dying person as a holistic—that is physical, mental and emotional—being” (2018, 79).

In graphic illness narratives, lists also often partake in and expose the autobiographical subject’s process of self-reflection and in several instances function to represent a subjective identity that struggles to gain in meaning because of a new embodied experience. Instead of engaging in the objectification processes Rüggemeier analyses, in these cases, lists grant the ill subject the opportunity to reflect on, assess, and communicate their new embodied experience of self. This is especially apparent when lists intersect and engage with the visual representation of the ill subject’s body. In such instances, lists do not present as an orderly grouping of related traits, events, or other types of things. Rather, they acquire narrativity by entering into a dialogue with the visualized body to expose an experience of self that exists in relation to how the subject’s body feels in the world and to the self, as well as in relation to others and to the social discourses informing identity formations and the bodies that communicate them. They thus address the new, disruptive, or noncanonical embodied experience of illness as it intersects with the world, one’s mind, and others.

2. The Poetic List

In his

Infinity of Lists,

Umberto Eco (

2009) adopts an historical approach informed by semiotics and communication theory to examine the list as a particular discourse unit. Providing readers with a critical overview of listing forms and styles and distinguishing between practical lists and poetic lists, Eco advances an understanding of the practical list as a particularly pragmatic discursive form. He proposes that the items in practical lists correspond to particular objects in concrete reality. Consequently, these lists are referential, finite, and unalterable (113). Practical lists abound in everyday life and serve as tools to remember things and events (shopping lists, calendars) and to plan ahead (to-do lists, grocery lists, bucket lists) or as organizational guides (brain dump lists, errands lists, guest lists, inventory lists). In them, items are often assembled straightforwardly—clearly separated, enumerated, and/or labelled—and arranged in neat and easily legible patterns—grouped, categorized, and/or associated so that they can impart information quickly and in an orderly, clear manner. The formal features of practical lists make them particularly suited to manage information that may not otherwise as effectively be managed and communicate it in a non-ambiguous fashion.

Eco also notes that most lists—especially those in literary texts—communicate differently than the referential way of practical lists. Breaking the narrative thread by introducing a different mode of representation, lists in literary texts fulfill narrative functions that extend beyond the naming and listing, the thoughtful grouping and organizing of real things. These lists, which Eco calls poetic lists, present readers with what cannot be articulated, enumerated, or controlled (117). Fostering a sense of incompleteness, of not ending or forever expanding, they are characterized by excessiveness and dizziness. Poetic lists suspend the “common expectation of termination” (

Belknap 2000a, p. 28) in their articulation of the ineffable, thus offering numerous interpretive possibilities. Unlike practical lists, poetic lists point to that which is not present, to that which is “inarticulate and incommunicable” (

Mancino 2017, p. 140) and, by extension, not fully comprehensible. Consequently, their meaning is suggestive, ambiguous, and unfixed. Open and endless, poetic lists always announce what Eco calls the “etcetera”, communicating through the realization that “the quantity of things is too vast to be recorded” (

Eco 2009, pp. 122–23).

Poetic lists rely on and activate the potential of lists to communicate “the informal, makeshift or random aspects of experience” (

Belknap 2000a, p. 7). They often forgo the formal pattern of practical lists to present the disorganization of thinking that comes with not knowing and that characterizes the type of identity presented in many autobiographical graphic illness narratives. Indeed, Eco’s specifications about poetic lists call to mind the oft-repeated assertion that identity is too messy, too fragmentary, and too often invented and re-invented to be represented with certainty and once and for all. Those who study life-writing have emphasized that not only is the autobiographical self split into observer and observed, as Sidonie Smith and Julia Watson assert (

Smith and Watson 2010, pp. 124–25), it is also always in process, constantly emerging and evolving through the very process of representation (

Eakin 1999, p. 20). Or, to adopt Eco’s terminology, identity in life-writing, including the identities represented in autobiographical graphic illness narratives, always announces its etcetera state of being.

Indeed, it could be argued that the ill self is particularly vast and boundless, unpredictable and unknowable. As American sociologist Barbara Rosenblum writes in her co-authored cancer memoir,

Cancer in Two Voices, the ill self is “hostage to the capriciousness of [one’s] body, a body that sabotages [one’s] sense of a continuous and taken-for-granted reality” (

Butler and Rosenblum 1991, p. 138). In autobiographical graphic illness narratives, where illness threatens identities and the bodies that house them and help to form them, the ill subject is often aware of being marked by plurality and experiences a fleeting, uncertain understanding of self. “I know who I was when I got up this morning, but I think I must have been changed several times since then” reflects Alice, the protagonist of Dana Walrath’s

Aliceheimer’s: Alzheimer’s through the Looking Glass (

Walrath 2013), an autobiographical graphic illness narrative about Walrath’s and her mother Alice’s experience with Alzheimer’s. A similar feeling of having one’s identity overtaken and configured anew by illness is expressed in Peter Dunlap-Shohl’s

My Degeneration: A Journey through Parkinson’s (

Dunlap-Shohl 2016) when Peter admits, “I realized then how far I had incorporated my illness into myself…The person I have become has lived with the ills of PD for over a decade. Over that time I evolved a different scale to measure my well-being” (66). Illness has long been recognized by theorists and practitioners alike as a subjective experience that impacts one’s sense of self, imposing new meaning—different role positions, choices, and behaviors—on the ill self (see

Charmaz 1983;

Charmaz 1991;

Karp 1996;

Lively and Smith 2011). Just as bodies and minds change and become unrecognizable through illness, so too does one’s sense of self.

Autobiographical graphic illness narratives thus join the type of memoirs

Thomas Couser (

2009) calls nobody memoirs: memoirs by minorities or that deal with physical or mental catastrophes that are “often about what it’s like to have or to

be, to live in or

as, a particular body—indeed, a body that is usually odd or anomalous” (2). Like literary nobody memoirs, autobiographical graphic illness narratives inscribe a personal sense of self across the body. However, because visual representations of the body are visually malleable, graphic illness narratives can avail of different discursive forms or representational modes to speak identity across the body. The list form is quite obviously at the top of the list of discursive forms used in autobiographical graphic illness narratives.

3. The Physical World and Your Physical Body

Robert Belknap (

2000a) notes that lists allow us “to order our surrounding world, verbally or symbolically putting everything into a sequence and an arrangement we desire” (xxii). In autobiographical graphic illness narratives, the role of the list joins that of the body in making possible knowledge of the world and of the self within it, opening new ways of thinking about lived embodied experiences of illness.

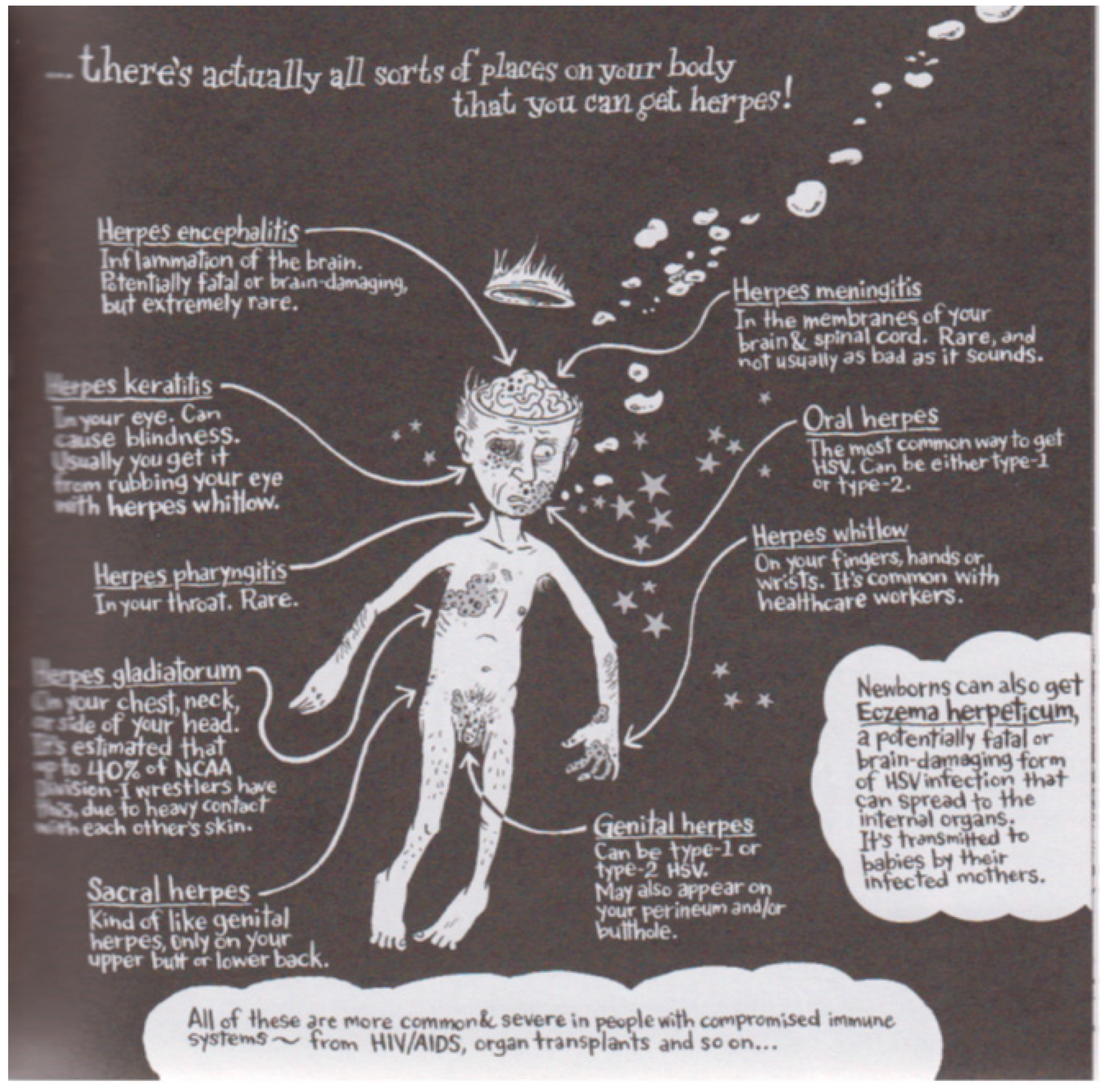

1 In Ken Dahl’s

Monsters, for instance, a verbal list of possible types of Herpes often specifying who is most prone to contracting a given type of herpes surrounds the protagonist’s naked limp body, his brain exposed (115). Arrows point to where on Ken’s body the different types of herpes listed could impact (

Figure 1). The lesions on Ken’s body join the list’s verbal specifications to communicate Ken’s new embodied experience, his physical suffering, and his attempt to mentally process that suffering. Similarly, in Kirsti Evans and John Swogger’s

Something Different about Dad: How to Live with Your Amazing Asperger Parent (

Evans and Swogger 2016), Sophie’s father, Mark, who has Asperger syndrome, is pictured in the center of a list that groups his behavioral difficulties, differences, and talents into four categories that swirl around him (27). Finally, in

Tangles: A Story about Alzheimer’s, My Mother and Me, Midge Leavitt, who suffers from Alzheimer’s, sits in the middle of a list of questions the doctor poses to her while assessing her mental health (Leavitt 36). Hands crossed over her chest, she stares out at readers overwhelmed if not defeated by the questions listed. In these and similar examples, the list surrounds the subject’s body, which, due to its lack of coherence, makes it difficult or impossible for the self to make sense of the new physical reality it inhabits. The pairing of the list, which gives an impression of ordered knowledge, to the protagonist’s ill body, which struggles to make sense of its new physical reality, strongly suggests that the embodied experiences of illness are foreign to and fractured from a coherent sense of self. Consequently, these autobiographical subjects are unable to formulate a coherent understanding of themselves and the world in which they exist.

At times, lists in autobiographical graphic illness narratives are literally inscribed across the body, making it possible to speak of an autobiographical subject embodying the list’s terms. In

Raised on Ritalin (

Page 2016), Tyler Page’s autobiographical character, Tyler, lists the negative aspects of ADHD by way of a body list drawn on a board to which he points (316), the first half of which is transcribed into a lived embodied experience on the next page (317) (

Figure 2a,b). The first three items on the list—(1) “impulsive” (2) “thrill and novelty seeking”, and (3) “hard time weighing future consequences”—are visually translated on the next page across Tyler’s body that presents with clown-like features: puffy hair, large round nose, and long protruding tongue. In a study of class clowns,

Ruch et al. (

2014) list disruptive behavior, indulgence in a life of pleasure, and low self-regulation as character traits of clown personalities. The traits of clown-like behavior listed by Ruch, Platt, and Hoffan pair up quite straightforwardly with the ADHD traits in Tyler’s chart that, in turn, are translated across Tyler’s clown body. In this transition and translation from verbal list to visually embodied list, the negative aspects of ADHD are filtered through our protagonist’s mental workings that are also informed by his world knowledge of clowns.

4. Lists Integrating Mind and Body, or the Realm of Your Imagination

The mind, commonly “understood as the connected totality of a person’s thoughts, emotions, intentions, desires, sensations, perceptions, dispositions, etc.”, is embodied (

Walker 1969, p. 45). In her influential study,

Volatile Bodies, feminist scholar

Elizabeth Grosz (

1994) references the Möbius strip to illustrate the dynamic interrelationship between body and mind, which she posits as “the torsion of the one into the other” (xii). In graphic memoirs, of which the autobiographical graphic illness narrative is a sub-genre, the production and presentation of the self across the body realizes the dynamic and interactive mind–body relation that Grosz’s model suggests. As

Elisabeth El Refaie (

2012a) argues, the drawn, corporeal self in a graphic memoir (i.e., autobiographical comics) offers a holistic model of subjectivity that integrates the body and mind (51). In its visual track, physical and mental realities meet across the body so that “individual minds and perceptions necessarily intersect with the body” (

Horstkotte and Pedri 2016, p. 81). Although the portrayal of the self in graphic memoir is multiple—diversiform, multifold, multiplied—and often oscillates between various fashionings of the subject (

Groensteen 2011, p. 108), it nonetheless externalizes—gives visual body to—the subject’s interior landscape. Thus, besides resemblance and recognition, graphic memoirs’ portrayals of the autobiographical subject’s body achieve a manifestation of intangible characteristics—personality and inner life—and of all of the elements of one’s identity that can be sensed, but not seen.

Unsurprisingly, in autobiographical graphic illness narratives, fashionings of the self across the body communicate the impact of illness on one’s changing sense of self. Unlike graphic memoir, which is most often concerned with a self in the making, graphic illness narratives portray a self that is in many ways being unmade and remade differently through illness. In them, the autobiographical subject is split between health and illness, existing between and within what

Susan Sontag (

1978) has called the “kingdom of the well and the kingdom of the sick” (3). In addition, it also experiences a sense of being split because made painfully aware of the “grind[ing] against each other” of “the external and internal worlds” that is often experienced by people suffering from physical or mental illness (

Williams 2014, p. 69).

The collision of external and internal worlds, “consciousness and experience” (

Gilmore 2016, p. 678), across the body is particularly evident in Ellen Forney’s

Marbles and

Rock Steady about the author’s experience with bipolar disorder. As

Courtney Donovan (

2014) notes, “Embodiment is central not only to Forney’s experience of bipolar disorder, but also to her written and visual narratives; specifically, she emphasizes how the contrasting moods of mania and depression create distinct embodied experiences” (238–39). In her two autobiographical graphic illness narratives, lists “figure prominently in the long process of coming to terms with her chronic illness” (

Rüggemeier 2020, p. 479). Addressing embodiment or the what it is like to live with bipolar disorder, lists fulfill a central narrative role in Forney’s works.

In Rock Steady’s third chapter, in which Ellen, the autobiographical subject, promotes the mental health benefits of journaling, five drastically different self-portraits are arranged across a page (53). Each self-portrait in the visual list is a recrafting of Ellen’s body and results from one of Ellen’s many attempts to visually express different physical and mental experiences. Together, the self-portraits list a number of possible and seemingly incongruent embodied manifestations of who Ellen feels herself to be. Each item in the list is drawn in a spiral notebook or on ripped pieces of lined paper and arranged in an orderly fashion across three rows with no overlap between them. Their careful arrangement creates the impression that Ellen may be gaining a better understanding of the many mental states she experiences and how they change her sense of self. Whereas the first two self-portraits are ambiguous and offer little as to what they communicate of Ellen or her understanding of self, the final three reproduce visual traits that are associated with Ellen throughout Marbles and Rock Steady, such as her recognizable hair style and eyes. They also include short reading directives in Ellen’s voice—“Okay. Got this” and “space cadette”—that suggest the particular mental state Ellen aims to translate into drawing.

In line with the visual depiction of Ellen throughout

Marbles, the five self-portraits are characterized by difference and incongruence. However, they are carefully grouped together as separate, but equally important, valid, and insightful renditions of Ellen. In this way, they can be approached as staging Ellen’s sustained process of self-understanding and self-revelation as a person with bipolar. As the caption at the bottom of the page states, each self-portrait is representative of “drawing in action”, an exercise in self-understanding “where [she] could face [her] emotional demons in a wholly personal way” (92). As

Lisa Diedrich (

2019) writes, Forney’s autobiographical graphic illness narratives “demonstrate how drawing can offer a therapeutic method for externalizing internal thoughts and feelings.” The items in the visual list communicate Ellen’s differing experiences of the self across the body, visually mapping her identity as being in process, changing and multiplying, moving and shifting between Ellen’s different states of being and different imaginings of the self.

In Marbles, Forney introduces a significantly more striking list of self-portraits that depict how she “was feeling” (99), or how she perceives or imagines herself to be. Drawing her body or parts of it wrapped in bandages across the fingers of her hand (102), Ellen again addresses her emotional states of being that morph into wildly different experiences, but that also come together in lists (and in its creator’s mind—Ellen’s mind) to convey a messy, unfinished, unknowable formulation of the self. Forney’s lists communicate Ellen’s struggle towards self-understanding. At the same time, the doubling back on the process of self-exploration also indicates a self in flux, infinitely reconfiguring its impression of self across the body and according to each new lived experience.

In this sense, the many visual lists included in Forney’s autobiographical graphic illness narratives do not merely function as “a handy means to define and manage a disease that by its very definition (bipolar

disorder) suggests that something about Forney (thinking, emotions, behavior) is not ‘as it should be’ and therefore needs to be (re-)ordered” (

Rüggemeier 2018, p. 476). They do not only serve to enumerate or illustrate distinct embodied experiences or reactions to the discourses that surround illness. Rather, they also highlight the incompleteness of the autobiographical subject’s experience with illness and the impossibility of fully or even satisfactorily knowing and managing ever-fluctuating impressions of the self.

By foregrounding variation and interpretation, the lists included in Rock Steady and Marbles also complicate the relation between identity and its visual, embodied self-representation. On the one hand, the lists speak to the autobiographical subject’s explicit engagement with her own mind and body as they intersect with changing understandings of the self. By presenting and re-presenting different versions of the self, the self-portraits posit Ellen’s identity as open to plurality and fragmentation because it is highly susceptible to changes in experience. Constantly revisited, reworked, and adjusted to new physical and psychic realities, Ellen’s identity multiplies into unpredictable configurations that always point to the incompleteness of that very configuration. Thus, although these visual lists that present the body in different states and across different styles communicate her sustained commitment to fashioning an embodied self on her own terms, they also accentuate the incompleteness and the fleetingness of personal, subjective understandings of the self.

The act of autobiographical writing is one through which the account of self—the events, emotions, and people that shape an identity—is informed by “one’s interpretation of one’s life” (

Yagoda 2009, p. 110). Questions of self-representation and expression such as those raised in several autobiographical graphic illness narratives thus tightly entwine with questions of how the self understands itself as a textual subject, and this understanding is strongly rooted in the realm of one’s imagination. In Forney’s lists, the identity of the autobiographical subject is made an object of that subject’s own investigations and mental reworkings of self. As

Michael Chaney (

2011) specifies, there is a “narrative urgency in graphic memoir to make the autobiographer visible as a self in relation to itself” (31), and this visibility manifests across the autobiographical subject’s body and its manifestation in lists.

5. Your Existence in the Minds of Others

Writing in 1988 about women’s autobiographical selves, feminist critic

Susan Stanford Friedman (

1988) emphasizes that a sense of existing alongside others, with others, and through others makes autobiography possible (38). Autobiographical theorists and practitioners alike have followed Friedman’s theorizing, approaching personal identity “as a complicated interaction of one’s own sense of self and others’ understanding of who one is” (

Nelson 2001, p. xi; see

Meynell 2021, p. 7). Far from autonomous, the self extends to and is formed it relation to others, “through interpersonal relationships with others and within socio-political, historical, and other contexts” (

Boon et al. 2023, p. 1).

This understanding of identity as dependent on the relationship between the embodied self and others is reflected in a panel from Ken Dahl’s

Monsters briefly examined above in relation to embodiment (

Figure 1). The verbal list, which is visually translated across Ken’s body, carries readers into Ken’s imaginary world. In Ken’s self-portrait, he physically manifests the types of herpes he discovered while surfing the internet, which are familiar to readers from an earlier four-panel visual list of the herpes Ken found on the internet (51–2). The similarities between the herpes spread across Ken’s afflicted body and the internet images are so striking that they strongly suggest that the autobiographical subject’s understanding of his ill self intersects seamlessly with how the current medical discourse conceives of herpes.

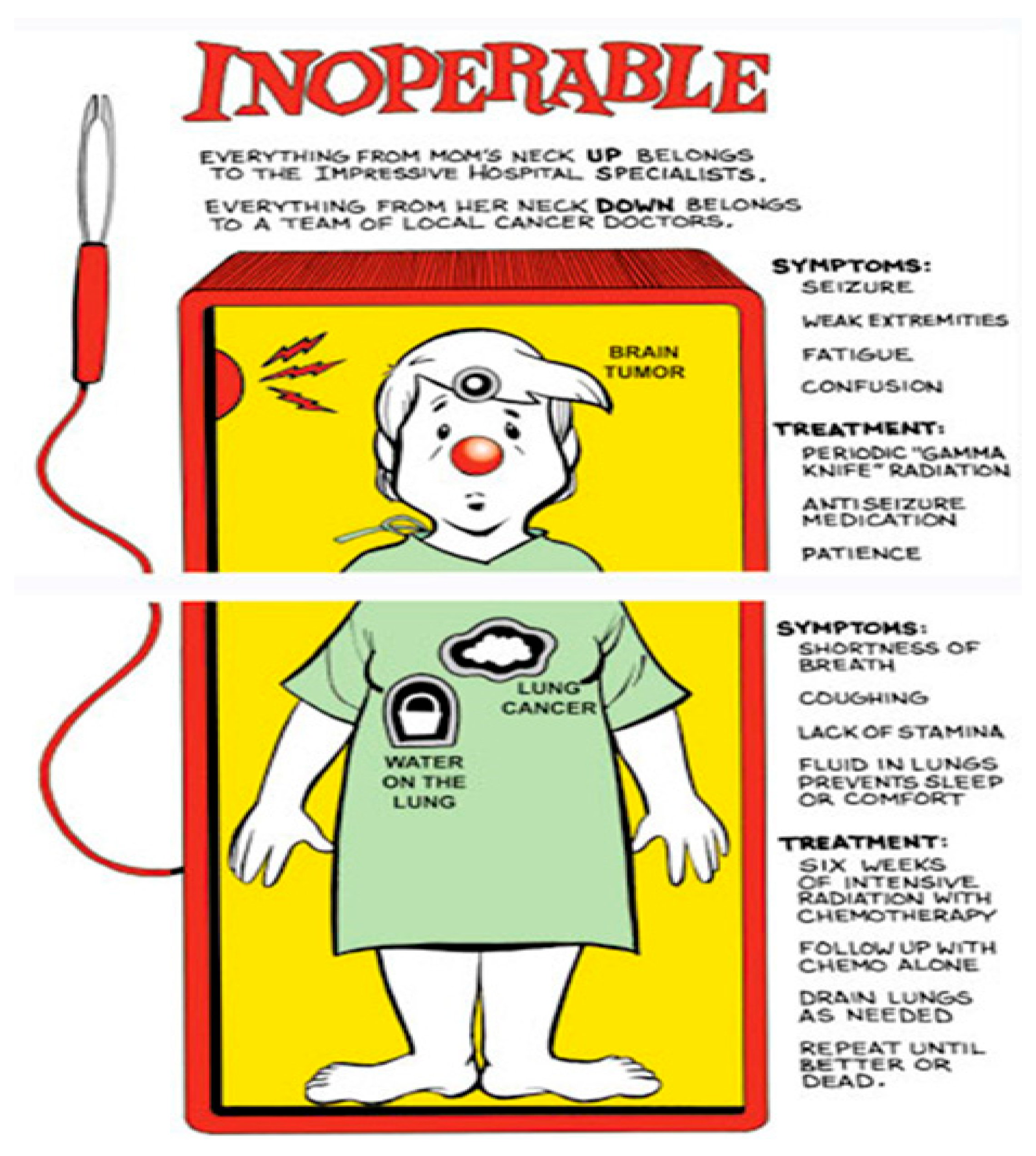

The formation of the ill self in the minds of medical professionals is critically addressed in a two-page image in Brian Fies’

Mom’s Cancer, a graphic illness narrative about caring for a mother with cancer (

Figure 3), showing mom wearing a green hospital gown figures in a parody of Milton Bradley’s Operation. Her body extended as she stares out at readers, she takes the place of Sam (the original game’s patient) on the operation table, a list of her three main medical conditions—“Brain Tumor”, “Lung Cancer”, and “Water on the Lung”—replacing the game’s original thirteen ailments. This short list, which reminds readers that “illness brings us back to the body” (

Langan 2007, p. 250), is paired with other lists: a two-item list above the game board and a list of symptoms and treatments along the side of the game board. The reduction in mom’s ill body to a three-item list divided across two separate sections of her body according to which doctors each section belongs to critically addresses how mom’s identity and understanding of self is in existential engagement with the sense others have of her. Once ill, her identity is modelled and managed, processed and known also under the aegis of medical discourses and practitioners.

That mom’s sense of self is impacted by how medical professionals perceive and treat her is further confirmed by the two sets of tidy lists of symptoms and treatments that run along the side of the Inoperable game board. The enumerated items are factual, but also clearly detached from mom’s actual body and self as felt by her. Here, her body is configured as a site through which health, medical experience, and identity intersect. Literally rendered a list of ailments, symptoms, and treatments, a not-me, a generic Other, in this state of illness, mom’s identity exists primarily as others conceive of it.

6. Conclusions

Lists in autobiographical graphic illness narratives often expose and engage with the workings of a mind in the act of processing changing physical and emotional realities that impact identity. Taking on “many forms and patterns” and inviting “many uses and interpretations” (

Belknap 2000a, p. xii), they narrate understandings of self, imagined by an embodied self and by others. As Rüggemeier has shown and as the examples above demonstrate, lists are remarkably malleable and can present as an alternative form of self-representation that gives shape to and imposes order onto disparate aspects of self. They can and often do organize important aspects because revealing information about the autobiographical subject’s embodied personal identity.

However, as I have shown through close analysis and in conversation with current theorizations of the list form, identity, and embodiment, lists in autobiographical graphic illness narratives intersect with the visualized bodies of ill subjects to express that subject’s changing physical and psychic realities as understood by them. When considered in relation to narrative practices of embodiment in graphic illness narratives, the list can also simultaneously propose many views and variant versions of the same identity, and thus give shape to a divided and multiple (‘decentered’) autobiographical self. As Eco argues, poetic lists announce their potential for expansion. I have detailed how autobiographical graphic illness narratives often rely on the list’s potential for expansion to invite readers to consider the ambiguity and multiplicity of the autobiographical subject’s identity and lived experience with illness. With repeated and diverse visual embodiments of the ill subject, lists are a popular narrative tool used by creators of autobiographical graphic illness narratives to communicate the ill subject’s changing identity and lived experience. In several autobiographical graphic illness narratives, lists fulfil an important narrative function: they join the multiple representations of an embodied self to address the three fundamental aspects of identity addressed by Kochalka and that are accentuated through illness: one’s embodied experience, one’s imagined experience, and one’s existence for others.