Abstract

Since the late 1990s, Chinese internet publishing has seen a surge in literary production in terms of danmei, which are webnovels that share many of the features of Anglophone fanfiction. Thanks in part to recent live-action adaptations, there has been an influx of new Western and Chinese diaspora readers of danmei. Juxtaposing these bodies of literature in English in particular enables us to examine the complexities of how danmei are newly circulating in the Anglophone world and have become available themselves for transformative work, as readers also write fanfiction based on danmei. This paper offers a comparative reading of the following three such texts, which explore trauma recovery through the arc of romance: Tianya Ke, a danmei novel by Priest; Notebook No. 6 by magdaliny, a novella-length piece of fanfiction based on Marvel characters; and orange_crushed’s Strays, a fanfiction based on the live-action drama that was, in turn, based on Tianya Ke. The space described by Lotman’s semiosphere offers an additional model in which these texts reflect on one another; furthermore, along the porous digital border between fanfiction, danmei in translation, and fan novels based on danmei, readers and writers negotiate and vex contemporary culture.

1. Introduction

Since 1998, Chinese internet publishing has seen a surge in literary production in terms of danmei, male/male romantic webnovels, which first came to the mainland from Japan via Taiwan (Feng 2009, 2013; Yang and Xu 2016; Xu and Yang 2022). Danmei and fanfiction share many features, such as the following: primarily female-authored and read by female fans (Liu 2017), they are pseudonymous texts that are serially published, center queer romance and issues of queer sexuality, arise within a frequently non-professional community of writers, and rely on internet platforms to give underrepresented writers a voice. In China, these novels generally fit into already popular tropes, such as science fiction “revolution plus love” narratives (Ni 2018), police procedural, urban fantasy, wuxia, or xianxia. Since the pornography crackdown of 2014, followed by additional restrictions in 2021, their legal status remains murky at best, and more than one danmei author has been arrested and imprisoned (Yang and Xu 2016; mercyandmagic 2021). Despite this, as of 2019, the popular danmei site, Jinjiang Literature City (jjwxc.net), had 12.8 million registered users and 1.6 million contracted writers, and the website has published 29 million titles (Wu 2019). While not all, or even most, webnovels on JJWXC are danmei, they are frequently among the most popular VIP webnovels purchased and read, and Priest (whose work is the topic of this paper) is the top romance author on the site, authoring both heterosexual and queer romances.

In 2018, the danmei fandom began to gain popularity in the West thanks to a handful of popular critically well-regarded dangai, or live-action adaptations. Thanks to these series, there has been an influx of new Western and Chinese diaspora readers of danmei, mostly relying on translations, which are typically unofficial and created by fans. The first highly successful adaptation was 2018’s Zhen Hun or Guardian, based on a 2012 urban-fantasy danmei of the same title by Priest; followed by 2019’s Chen Qing Ling or The Untamed, based on the 2015–2016 xianxia novel Modao Zushi by Mo Xiang Tong Xiu (MXTX); and, most recently, 2021’s Shen He Ling or Word of Honor, based on Priest’s (2010–2011) wuxia novel Tianya Ke or Faraway Wanderers. The breakthrough popularity of these three television dramas, internationally as well as in China, has brought attention and readership to the danmei on which they were based, and many Western and diaspora fans who may previously have only read Anglophone fanfiction1 now find themselves navigating and negotiating a new subject position with regard to Chinese media, often acquiring cultural competencies in pursuit of this interest.

Juxtaposing these bodies of literature in English enables us to examine the complexities of how danmei are newly circulating in the Anglophone world and have become available themselves for transformative work, as international and Western fans in turn write fanfiction based on Chinese-language danmei. While both fanfiction and danmei are romances, that is not all they are. Their literary complexity and themes lend themselves to subtle analyses of psychology and power. Of particular interest are the ways in which danmei and fanfiction collect and encode important information not only about women’s writing and queer literature, but how reader–writers negotiate and vex contemporary culture and politics in their telling and retelling of trauma narratives, transposing or translating the body of the (usually female) reader–writers onto the male character in a transformative act of appliqué.

With trauma as a common and crucial theme underlying fanfiction, Lucy Baker and I have argued elsewhere that fanfiction offers uniquely intimate literary examples of personal writing, and, in the case of “trauma texts”—autobiographical works that combine life writing and memoir with the political, social, and emotional context of the

trauma—that use the extant canon to draw on personal experience and political contexts of media. The form of fanfic provides a unique space for literary exploration of trauma, including what Whitlock and Douglas (2015) call “the ethics of testimony and witnessing, the commodification of traumatic story, and politics of recognition.” (Baker and Lowe 2020).

Both Western and Eastern media are rife with traumatized male characters, incapable of speaking to their suffering in canon, who are capably adopted by the writers who volunteer to tell their stories. Whitlock and Douglas also consider “the question of who gets to speak/write/inscribe autobiographically and how and where and why”. For marginalized writers in imperialist and/or autocratic societies, in spite of whatever putative social advances they have been reassured, they may prefer to craft and share life writing using the veneer of telling another’s story. The authors’ own sublimated accounts of the rebelliously queer, disabled, or female body may be rendered as transformative works of fanfiction and/or danmei, saturated with tropes as reader–writers extroject themselves into relevant characters, figures able to manifest and display, hold, and contain, traumatic significance.

This paper considers the following three such narratives: Tianya Ke, a wuxia novel by Priest in which two martial artists with blood-soaked pasts must fight to see if they can now live in peace; Notebook No. 6 by magdaliny, a novella-length investigation of political violence, trauma recovery, and the rebelliously queer disabled body, based on Marvel characters; and orange_crushed’s Strays, a fanfiction based on Priest’s characters from the 2021 live-action drama. These texts were selected because there has been little to no work in English on Tianya Ke, and because the two representative pieces of fanfiction particularly illuminate the work created by transformative writing speaking as trauma text.

Along the porous digital border between fanfiction novels, danmei in translation, and fan novels based on those danmei, how can we locate the reader–writer, so often the same person, to shed light on her process and solutions? As a researcher whose previous work has focused on Anglophone fanfiction, I came to this task with many fewer cultural competencies than I could have wished, and appreciate the reader’s patience with this cross-cultural attempt, given the complexities of the genre and literary history. In conducting such research, it seems to me that the received notions of subject and other become rapidly shifting novel targets amidst the upheaval of discursive positions. To recontextualize these so that anything useful or universal may be said about the reader–writer, it becomes necessary to read cross-cultural texts very closely.

It is unfortunately beyond the intention and purview of this paper to go very deeply into the historical and sociological contexts of BL culture and its gradual spread throughout Asia. However, of particular importance to note is the recent collection Queer Transfigurations: Boys Love Media in Asia, which offers a chapter specifically dealing with the cross-fertilization of Chinese danmei and Anglophone fanfiction (Xu and Yang 2022). The authors argue that “the danmei genre itself has functioned as a productive contact zone in which BL and slash [fanfiction] interact, as Chinese fans have appropriated useful elements from both genres” (Xu and Yang 2022). They go on to observe that “BL and slash [fanfiction] are generally assumed to have developed independently of each other in the 1970s, and thus far there has been very little comparative research of the two genres…[though] a ‘world system’ of women-oriented male homoerotic narratives seems to be emerging.” This paper hopes to augment such comparative research with a study in the form of close reading.

While examining these three pieces specifically as trauma texts, the space described by Yuri Lotman’s semiosphere may offer an additional model via which they reflect on one another. Lotman suggests that mutual untranslatability yields a valuable parsing of reality. The author creates ostensive characters, and the readers consume those characters—but what is being described, really, and for whom? One potential way to fix this point in space may be triangulating using precisely such a set of collocated texts: Sinophone, Anglophone, and those derived from both. Given the way such texts circulate and cross-pollinate digitally and transculturally, their juxtaposition may suggest points of rhyming and overlap.

2. Mapping the Jianghu

Originally published in China in 2010, Tianya Ke has had a recent spate of new readers, in spite of the fact that the novel has been removed from Jinjiang Literature City (as have most novels by Priest, possibly to have troublesome homosexual content edited out of them), and that its existing fan translations into English are multiple, uneven in quality, and not easy to locate or stitch together to make a complete, easily readable version.

A danmei novel in the wuxia style, Tianya Ke, is both an exemplar of these received, culturally embedded forms with their own tropes and historicity, and pushes against them. The story is told from the point of view of Zhou Zishu, founder and head of a spy organization called Tian Chuang (Heaven’s Window, literally Skylight). After years of serving the emperor, Zhou Zishu becomes disgusted by court politics and the horrific deeds that he himself has carried out (told in a previous novel by Priest, Qi Ye or Lord Seventh, in which Zhou Zishu is a memorable minor character). To escape Tian Chuang, he elects a slow form of suicide variously translated as the Seven Nails, the Nails of Seven Orifices, or, more poetically, the Nails of Seven Apertures for Three Autumns, which will leave him with only three years to live, with his martial powers much reduced. Disguised as a beggar, he sets off to travel the jianghu, or martial world, with whatever time he has remaining.

Given the importance of the jianghu to the wuxia genre, it seems worthwhile to examine it more closely. The jianghu (whose characters literally mean “rivers and lakes”) into which Zhou Zishu attempts to disappear is an unstable site familiar to both readers of classical Chinese literature and viewers of John Woo films, with a long cultural history. It is at once analogous to the medieval realm of knights’ errantry, the Wild West, and gangster/Mafia narratives, and is also exactly like none of these—the jianghu is an actual cultural space in contemporary China, as well as an historical and metaphorical literary realm that is “both a fantasy fueled by the popular media and a social reality for the marginalized working-class men” (Cao 2012). Priest describes the jianghu with characteristic evasiveness as follows: “ambiguity was one of its staples. If the royal court was a battleground for fame and power, jianghu was a battleground between white and black. Though some were unable to understand this, and took the title of a wandering hero too seriously even until they died.” (Chapter 3; all subsequent references will refer to chapters by number.)

Filmmaker Jia Zhangke notes that rivers and lakes “implies an ocean of people…a visual picture of individual members being dissolved into and devoured by this jianghu world”(Chen et al. 2019) He continues as follows:

“The jianghu subculture is a core value deeply rooted in Chinese culture, usually emerging when a society or community or country undergoes dramatic transformations, or when the social environment is riddled with crises…The jianghu subculture is…provides from the margins of society a distinctive perspective with which to examine and challenge the orthodox culture. […] These people also experience intense emotions, often raw and visceral, whether among brothers, friends, or between lovers. In addition, people in jianghu also navigate a gray area of society and live, paradoxically, by using illicit or illegal means to defend justice, morals, or values.”

In Stateless Subjects, Liu takes the concept of the jianghu as “an approximate equivalent for ‘statelessness’…a public sphere unconnected to the sovereign power of the state.” In reviewing Liu, Altenburger notes that “previous discussions of the notion of jianghu…tended to read it as an alternative, even otherworldly, sphere at the periphery of human society.”(Altenburger 2012) These descriptions also highlight the jianghu’s blurrily liminal state of existence, a coalescent quality that lends it perhaps most closely of all to comparison with the chivalric Arthurian realm, particularly those narratives (e.g., Chrétien de Troyes’s Yvain) that thrust the knight-errant out of cities and castles and into the forests of the possible, where he must roam unshaven and insane, without salt or bread, until he has recovered from his initial ostracizing narcissistic injury.

Zhou Zishu’s injury is, by contrast, self-inflicted; moreover, he has embodied his trauma and his guilt and made them visible and literal by penetrating himself with the Seven Nails. This punishment seems a worthwhile exchange for him to be liberated from Tian Chuang, even at the cost of the martial arts abilities that define him. He appears pleased to receive the final nail, which we have already seen incapacitate one of his subordinates, a man hauled away, unable to stand on his own, as shown in the following excerpt: “He looked like he had come across the funniest tale, sickly pale complexion flushing faintly. With great delight, he turned to Duan Pengju, putting the nails into the latter’s palms, ‘Do it.’ …Even [his] groans seemed to contain joy. […] He walked out of the study, all the baggage over the years now light as feather. His silhouette seemed to flash for a moment, and he vanished without a trace” (1).

In addition to his all-but-undefeatable gongfu or quingong (as it is left untranslated in the text), Zhou Zishu’s other defining feature is his spycraft, especially his ability to vanish in a crowd, hiding in plain sight. Priest tells us that he “was like a drop of water in a big ocean; the moment one lost sight of him, his existence would be impossible to be detected” (25). Zhou Zishu’s absorption into the jianghu is his apotheosis as the consummate spy; furthermore, he is nameless, faceless, unknown, able to mingle in this current of anonymity and dissolve his boundaries, so troubling and troublesome, in the rivers and lakes, peaceably drinking himself to death.

While drinking and basking in the sun, however, he encounters Wen Kexing, who seems to be no more than an annoying dandy, as shown in the following excerpt: “Wen Kexing disguised himself too well; many times, even Zhou Zishu would mistake him for just an ordinary, talkative man” (46). From its gothic first chapters, Tianya Ke settles into a meandering narrative of life on the road, with adventures and fight scenes sprinkled through with Wen Kexing’s overbearing attempts at seduction and Zhou Zishu’s withering replies.

It is only gradually revealed that Wen Kexing is the ruthless master of Ghost Valley—once entered, no one can leave, not unlike the Window of Heaven. Ghost Valley’s inhabitants are “a swarm of the wickedest venomous insects that had been sealed in a narrow, cramped container, where massacring one another was the only way to keep surviving. […] There were no morals, and no axioms; there was only the survival of the fittest” (46). As a collection of society’s castoffs, too lawless to fit in elsewhere, Ghost Valley contrasts with the rigid-mannered hierarchy of the imperial court and its arm Tian Chuang.

Wen Kexing has chosen camouflage. He hides his trauma and his ruthless Ghost Valley identity beneath a smile, but his eyes are described as being almost reptilian, inhuman in their flatness, and his qi is so powerful he can make air slice like a sword with his bare hands. Immediately drawn to Zhou Zishu, despite his unattractive beggarly disguise, Wen Kexing essentially stalks him, even though Zhou Zishu tells him repeatedly (and unconvincingly) how irritating he finds this devotion, a not-uncommon trope in danmei. Thanks to their proximity, they become caught up together in a violent conflict that threatens to involve the entire jianghu.

One of the many pleasures of Tianya Ke is the realization that Zhou Zishu is a profoundly unreliable narrator, and nothing that he says can be taken at face value, which makes sense for a man of veils and masks, a poisoner, assassin, and wearer of disguises. In Qi Ye, he was mostly notable for, in addition to various heinous murders, his invisibility. However, to Wen Kexing, Zhou Zishu is preeminently visible, even when he protests that he would prefer to be left alone. His objections ring hollow, as he does nothing to get rid of him, as shown in the following excerpt:

“Even if I refuse, this person will tail me around anyway, Zhou Zishu thought, and if I agree he will pay for my food. He accepted the request quite cheerfully. Wen Kexing led the way with the brightest face. Zhou Zishu did an internal introspection; back when he was a half-ghost flitting about the palace, wearing robes and doing murderous business in a mysterious place full of apricot blossoms2, he might be brutal, but at least there was a grace to him as a cover. Since when had he become unabashedly shameless?”.(15)

Against Zhou Zishu’s exasperated tolerance of Wen Kexing, or at any rate his lazy unwillingness to be rid of him, Wen Kexing reads him as secretly yearning for companionship, and he provides what Zhou Zishu most needs, a worthy soulmate. The romance in the novel happens with excruciating slowness. At first, other than Wen Kexing’s persistent flirtations and rhapsodic poeticizing, there’s no romance to speak of, but with an inexorable accelerando, Zhou Zishu starts to take notice of Wen Kexing, despite himself, and, by the end, their mutual devotion is flagrant and inescapable, having made subtle advances on the reader in the same way it does on Zhou Zishu, gradually increasing until it is unavoidable that this is not merely a wuxia novel, one of “the pugilist world.” Priest took a minor villain and gave him a redemption arc, but via an atypical romance, one made notable by the fact that the men express their love mostly via insults and brawls.

Zhou Zishu lets Wen Kexing in with glacial slowness, wondering if he is really “sincere” (51). For men such as them, sincerity has never been a virtue. They are talented at dissembling, relying on seeming nonthreatening so as to strike unprepared enemies. Midway through the book, Zhou Zishu finally removes his facial disguise and Wen Kexing, dazed by his appearance, can only manage, “Have I mentioned before that I like men?” (38). In another metaphor for concealment and disguise, Wen Kexing skillfully inserts himself into Zhou Zishu’s bed, “like a cuckoo that had taken over a magpie’s nest” (52). Even while most of their romantic activities take the form of quarreling, their continual bickering horrifies and embarrasses those around them, to whom their infatuation is evident.

In addition to depicting romantic love as combative, Priest also complicates the traditional danmei dynamic of gong and shou—popular sexual and romantic roles possibly analogous to seme/uke in BL, or perhaps adjacent to top/bottom in Anglophone fanfiction3. Chao argues that “using the terms of attacker and receiver in danmei narratives suggests sex positions and emotional relationships that work in a binary fashion” (Chao 2016, p. 67). However, while Zhou Zishu repeatedly and slightingly calls Wen Kexing wife, he winds up being the receptive partner in their single sex scene (Extra 1), though this may be due to his canonical laziness rather than anything else. While Wen Kexing is parental towards his young charge Gu Xiang, Zhou Zishu also has a found child in Zhang Chengling, so both are equally parental figures (cf. shou partners who give birth in shengziwen, a subgenre of danmei roughly analogous to mpreg in Anglophone fanfiction) (Wu 2019). Slighter and physically weaker than Wen Kexing, Zhou Zishu is nonetheless formidable in a fight, increasingly so as the novel progresses, and is ultimately tasked with rescuing Wen Kexing in the novel’s violent climax. Similarly, while Wen Kexing may be the physically more imposing partner, the household duties, such as cooking and marketing, are invariably relegated to him, and his complaints about this seem pro forma and perfunctory (see Figure 1). Troubling this dynamic is important to the project of Priest’s writing, as is her upheaval of standard wuxia tropes.

Figure 1.

Official art for the Tianya Ke audio drama depicts an aestheticized Wen Kexing as gong and Zhou Zishu as shou, though in the novel their roles are often complicated.

Whatever role either plays in the relationship, their trauma (which arises from their own coerced horrific actions) turns out to be soluble in mutual beneficial acceptance, or the concept popularized by psychologist Carl Rogers as unconditional positive regard. Zhou Zishu’s friend Jing Beiyuan states, “he has done those deeds that the heavens would strike him down for, but not one of them was committed out of selfish desires for his own ends” (Rogers 1951, p. 67). Wen Kexing similarly has committed unspeakable atrocities, but to survive Ghost Valley he could have done little else. In the process of self-recovery, Zhou Zishu remarks that “being a good person [is] really exhausting” (8), and he has found the only person in all of the jianghu who perhaps has done even worse, with a deeply concealed, desperate desire to exorcize it. Zhou Zishu’s unreliable narration lets us know that their blood-soaked pasts make them perfect for each other, and that Zhou Zishu’s repeated refusals do not really speak to what he deeply wants: recognition—for Wen Kexing to see through his disguises—acceptance, and ultimately, via that acceptance, redemption.

3. On the Mongolian Steppe

Viewers may be already familiar with James Buchanan “Bucky” Barnes, a character from Marvel Comics who reappears in the Marvel Cinematic Universe films, first as Steve Rogers’s World War II sidekick and, later, the brainwashed Soviet assassin known as the Winter Soldier. In the films, particularly Captain America: The Winter Soldier and Captain America: Civil War, Bucky is depicted as marked equally by the torture that he has undergone and by the harm he has unwillingly inflicted. His trauma is inscribed indelibly on his body by the fact of his metal arm. Being a cyborgian memento mori of his unconsciously violent days, the arm is both injury/wound and the occasion/cause of wounding others. A great deal of fanfiction is devoted towards both describing his trauma, often with elaborate descriptions of the pain caused by the arm, and then rehabilitating him in a way that the films could not make space for, or whose narratives would not permit.

Bucky’s notebook is canonical in Captain America: Civil War, seen by Steve Rogers, whose picture is stuck inside and bookmarked, as Bucky struggles to remember his former best friend and previous life (see Figure 2). Bucky’s notebook becomes his memory device and the place where he can sort out the puzzle of himself, as if he were pieces dumped from a box, all chaos and unmatched edges.

Figure 2.

Steve Rogers, in costume as Captain America, finds Bucky’s notebook.

Actor Sebastian Stan has claimed that, inside of Bucky’s backpack, the safety of which he prioritizes even as he flees detection in Civil War, are even more notebooks, as follows (Stan 2016):

“In his backpack there are a dozen notebooks that compose the scattered memories dating back to as far as he can remember which somewhat piece together a scattered life. In a similar way to Alzheimer’s, he’s written things down, for fear of losing his memory again. He was prepared, were something to happen, to walk away with nothing but that backpack, which is why it’s the only thing he takes and knowing full well that not everything those pages contain is pretty.”

Author magdaliny’s series Notebook No. 6 (magdaliny 2018) takes as its occasion the presumed existence of these notebooks, life writing meant to return him to his own agency. Notebook No. 6 also gives the reader an overt cue in the metadata for the novella-length “The Interrogation” as the author has tagged the fic with “Unreliable Narrator,” so we know up front that her Bucky, while directly dictating events into his notebook, is nonetheless not someone to be trusted, because his mind is the very thing that has been taken away from him. In recounting the story of Honi, the Circle Maker from the Talmud, Bucky adds, “I wish I’d only slept for seventy years. I wish I’d only been forgotten. There’s things out there worse than dying, sweetheart. I’m one of them.” For Bucky, the horror of his body committing acts over which he had no control was precisely that he was conscious of his actions the entire time. Bucky describes the conditions of his loss of self-possession as follows:

“I was made of confusions and when I wasn’t confused about real things I was seeing things that weren’t. I was remembering missions but backwards and topsy-turvy. I was remembering people but not who they were to me. I was remembering Jew things but not that I was one, not exactly, and everything muddled-up on account of the goy years. Just information floating around inside me with no context.”

Bucky’s dissociation and depersonalization is so profound that he does not even understand himself as a body for most of the story. Like Zhou Zishu, he sets out to wander the world. He flees the scene at the end of Captain America: The Winter Soldier, after he has destroyed no small quantity of military equipment and nearly killed Steve Rogers (whom he flatly describes as his “mission,” and fails to recognize, except fleetingly). Bucky is almost completely out of his mind when he starts his journey, so he wanders equally wildly, veering from Singapore to Jakarta, and then the Mongolian steppe. Here, again, we see the monomyth, that trope particularly found in medievalism, of the mad, grieving hero going into the wilderness, such as Nebuchadnezzar letting his beard grow and his clothes become tattered, until some transformative act renders him fit to rejoin humanity as one of their own, as himself. Bucky writes, “I was more than half an animal still by the time I wandered out onto the steppes with no drive left in my head but north, stripping grains from grasses with my teeth and trying to decide if I was predator or prey.” Similarly, “Around then all I knew was the animal time. […] Animal time’s when you figure out the difference between you and things that aren’t you and why that distinction means anything at all when you’re aiming to rebuild a person from spare parts.” In distinguishing between “you and things that aren’t you,” Bucky eventually regains some grasp on his own subject position.

Magdaliny’s descriptions of his physical deterioration are graphic and abject, mirroring his internal disarray. Once he is taken in and cared for, however improbably, by a family of female Mongolian horsewomen, he begins to return to himself, chronicled in his notebook. He writes the following:

“Now I probably sound like every other white asshole going abroad to find themselves. Trouble with that kind of person is they who know they are and they just don’t like it…if anything you could say I was trying to find a self. My self, I didn’t have one of those yet, or at least not a sense of ownership, not something I felt I could grasp or describe or feel in my body. Not a solid thing at all. And anyway I’m not white, or I’m only white under the right conditions, or when it’s convenient for other folks, in the way of my momma’s people.”

Crucial about magdaliny’s Bucky is his non-canonical Jewishness, an identity that makes him both outsider/other and someone with deep roots, a heritage from which he can draw stories and strength of self, a connectedness that enables him to rediscover himself while literally lost in the world. Incantatory repeated phrases (“there’s a story and it goes like this”) are tells that place him back in telling his reinterpretation of his own life a midrash, in the same way that fanfiction itself can (Howell 2019)—but a version gaining authority and selfhood with every piece of past he sets down. He speaks about his previous notebooks and their primitive attempts at relating to/as a self, as follows:

“I wasn’t human and I wasn’t not and there was a lot of weeks where that was true, where the boundaries were feathery and I was a proto-person […] Back then I don’t think there was anything in the whole world that could’ve made me feel better, could’ve sped up that process, coming to the place where I could—not understand I suppose but begin to get what understanding even was, what it felt like In the thing I was slowly figuring out wasn’t an extension of a gun, a tool for conveying and converting calories into energy; a body, I mean. That was mine. Not mine because I’d killed it and dragged it back to my den for later. Mine because it was given to me.”

The sentence in the middle is perhaps so tangled syntactically because it is Bucky trying to separate himself, to reconstitute an identity beyond being someone else’s weapon. Like Zhou Zishu, with a second skin over his face, at this point Bucky is embodied only at a safe distance from himself.

Bucky’s Ma is vividly alive in the story, a character who tells stories from the Talmud to him and his sister, as is Steve’s mother, and this mention of her here as the one who gives him his body is a restorative act of inscription, as much as Oktyabr, the widow who takes him in and, along with her four daughters, nurses him back to physical health. The body of the mother alone is capable of restoring him to himself. Unlike Zhou Zishu and Wen Kexing’s romance, the romance between Bucky Barnes and Steve Rogers can only take place offscreen. It is not itself redemptive; however, increasingly, in the notebook, Bucky addresses Steve directly and takes issue with him on various matters. Instead, it is through repeated connection with the feminine maternal that Bucky begins to recover. A passage near the end of the fic recalls the names that their immigrant mothers gave to him and to Steve: Yankl and Stíofán, before America assimilates them. They use these names with each other, as secrets, calling on the maternal in their most intimate moments.

Bucky’s travels take him further, to the Mideast, and then to Eastern Europe, where he meets more characters who help him, including a young mutant girl, a barber, and a rabbi and his congregation. As the events of Avengers: Age of Ultron and then Civil War begin to unfold, Bucky sees the Avengers on a television in a bar, and his notebook begins to take on a more political tone. On historicity, and his being blamed for assassinations but not wartime killshots of “German boys,” he puts it as follows:

“Truth’s a thing that’s decided on and most of history’s either a compromise or an agenda in the making. You can’t measure it like weight or distance or time and you can’t hold it up to the light and check for flaws. You got to crack it open to see what it’s made of and then it’s not truth anymore, not a story, just a big soggy heap of facts you can rearrange how you like. And you can’t ever put it back again into the shell.”

Freed from the constraints of commercial feature films, magdaliny is able to let Bucky set his own record straight, not only about the violence that he has committed for the sake of the empire, but also about being, as Bucky puts it, “a queer mutant Yid.” Details from historical pre-war Brooklyn interweave with Bucky’s queerness to give it verisimilitude, with canonical events interleaved with historical ones, such as the East Coast hurricane of 1938. Thorough readers in this fandom will also know that the neighborhood in which Steve and Bucky grew up was adjacent to a well-known gay community, therefore, this Bucky’s accounts of dancing with and kissing men are not improbable (alwaysanoriginal 2020).

He has managed to keep his queer identity and desires a secret from Steve, or so he thinks. When Steve finally catches up to him, Bucky is horrified to have his intensely private notebook be the first thing that Steve touches, as shown in the following excerpt:

“Holding the first notebook open with your thumb like it was a pulp you just couldn’t shut. I wanted to die even after you closed it up and put it back. I could feel your fingerprints like it was my skin my bones my heart bruising up blue and purple under your hands. And that’s when I saw you were in your uniform and I thought oh God oh Lord oh please I don’t want to do this again oh please I wish you’d never found me and now I’ll never get away….[That] is what I thought as you opened your mouth and said: you know me? I sure as shit do, you son of a bitch. That always has been my problem.”

Bucky fantasizes about Steve throughout the fic, and yearns to be close to him, even as he is guarded around him. Their interactions are erotically charged, even when Steve later symbolically restores Bucky’s notebook to him, stating the following: “you pulled out this notebook and handed it to me still warm from your body.”

Thus begins the final, more intense, period of healing for Bucky, as Steve and he travel to the Afro-futurist paradise of Black Panther’s Wakanda to have Bucky’s arm repaired, and once again he is housed with a female shepherd, Mowayndu. During this time, Bucky describes himself as a golem, but one that has taken on autonomy, as follows: “Knife’s in my hand now and my hand belongs to me. I’ll carve out everything they put in me or turn to dust trying. No more weapons. No more soldiers. No fucking more.” He circles the notion that he has been a tool of others who has reattained his own personhood, and that Steve should do the same, stating the following: “They wake you up and they give you a name and they put a thing in your hands and that thing is you, they say. You’re a gun. You’re a fist. You’re a shield. Sound familiar?” His stubborn old-fashioned insistence on feeling and being, as opposed to analysis or interpretation, gives the text a quality of fighting back, even against the reader. Bucky has for too long been a tool for others and refuses to be pinned in any one object position.

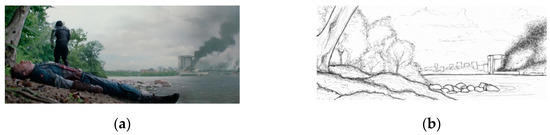

Magdaliny has illustrated her fic as images that are drawn as if through Bucky’s eyes, so that the reader is seeing what he sees, possibly as sketches in his notebook, as follows: his sister as a young woman, ruins in Aleppo, a Wakandan rhino, and the shul in Ivano-Frankivsk. The exception to this viewpoint is a drawing of the banks of the Potomac, immediately following the events of Winter Soldier. Here, the landscape is empty of both Bucky and Steve Rogers (see Figure 3a,b). This absence portrays the crucial way in which romance is elided in, yet at the heart of, Notebook No. 6. As an object, Bucky cannot find his subjectivity, except in Steve’s absence. Being brainwashed to the point of insanity, he asserts the remnants of his agency and selfhood by rescuing Steve from the river and then leaving to start his journey to find what has been taken from him.

Figure 3.

(a) The scene on the banks of the Potomac, after Bucky has rescued Steve from drowning in the river; (b) magdaliny’s illustration for “The Interrogation,” a landscape without either person.

Ultimately, in a novella both polyglot and polyvalent, magdaliny has brought many kinds of texts into collusion or collision—canonical, fictitious, religious, historic, visual—rousing questions as to what agency really means, as well as whether military or martial history may serve as metaphoric for other kinds of bodily trauma. Victims are stripped of agency when assault takes over either their body or mind, or both. We can read Bucky’s physical violations—indeed, we are invited to read them—in his abjection and his victimization by powerful others, as a kind of sexual assault. In canon, Bucky is shirtless when he is “wiped.” He is made to bite down on a rubber mouthguard and his calm, tacit assent to this procedure reads as eerie, uncanny, almost as troublesome as the violation itself (cf. sexual assault survivors universally describing their own compliance or freeze response). Consider in relation that Zhou Zishu’s piercing nails, which either penetrate or create new orifices, are not an accidentally sexual punishment. In the political warp and weft of empire, how much agency did Zhou Zishu really have, barely out of boyhood when he started Tian Chuang? And what re-enactments are danmei and fanfiction readers experiencing through these texts when they presumably are not themselves retired assassins seeking to reconstitute their autonomy? Which kinds of agency do they have in their lives, and which do they lack?

Notebook No. 6 ends with Steve and Bucky’s reunion, now told in third person through Steve’s limited point of view—a switch only possible because Bucky now exists to be seen, to be interacted with as a person. The romance can finally become overt as Steve has read the notebooks, and embraces Bucky fully, knowing his worst secrets. Similarly perhaps to Zhou Zishu and Wen Kexing hiding their affection through aggression, Bucky’s love confession happens when he thoroughly upbraids Steve for his carelessness with himself, consistently putting himself into danger. For Steve, Bucky’s own confession lay in the notebook. “You wrote me a love letter,” Steve tells him, “You wrote me a goddamn novel; what did you think I was gonna do with it?”

“Bucky,” is all that Steve can seem to say, and then, helplessly, “Yankl”, and Bucky’s carefully composed expression crumbles as though he has been stabbed, soft, wounded, and shocked. “Come—c’mere,” Steve says, “Please,” and Bucky takes a step forward like he is winding up for a punch and practically crawls into Steve’s arms. When Steve tucks his face into Bucky’s neck, he can hear the machinery in his arm whirring tinnily away, whatever he has for muscles in there revving up high as he clutches Steve tighter and tighter, following his lead. Steve must be hurting Bucky with how hard he is hanging on. His own lungs are being crushed, but it feels like he is breathing for the first time in a year, all the same.

Even in this most intimate connection, violence remains (stabbed, punch, machinery whirring, being crushed) in an embrace that is physically painful because of their enhanced strength. The narrative, nonetheless, insists that two men can show tenderness to one another even after the horrors wrought upon their bodies by history.

4. Shixiong and Shidi

To consider an enriching complication, there are now on Archive of Our Own about 7500 pieces of fanfiction citing Word of Honor as a canonical source text or point of entry (with another 1800 or so directly referencing Tianya Ke). Strays is one such, a novella-length piece of fiction by orange_crushed that places Zhou Zishu and Wen Kexing one degree over in an alternate universe, as the two struggle to escape Tian Chuang together, as its adherents and victims (orange_crushed 2021). In this case, Zhou Zishu’s hunger for freedom is not something that he is able to identify in himself alone. It takes the presence of Wen Kexing to catalyze his need for liberation, and, this time, he is able to escape with Wen Kexing without the self-inflicted penance of the Seven Nails. The romance here is the redemptive arc, and is overtly sexual; moreover, romantic love is that which can sustain one through trials and bring one to eventual safety, as shown in the following excerpt: “What is it, if not standing together on whatever steady or shifting ground is at your feet? To stand fast if an earthquake comes, an army, an avalanche, a flood to wash the face of the world away: what is love, if not a strong tree to hold your body against, when the howling wind would whip you into the sky?”

Word of Honor, the live-action adaptation of Tianya Ke, tempers the erotic relationship between Wen Kexing and Zhou Zishu by making them long-lost childhood friends who call each other shixiong and shidi, senior student and junior student—likely an attempt to weaken the danmei’s queer content onscreen. Strays not only maintains this distinction, but leans into it as a common wuxia trope. Zhou Zishu is in charge of training students. Wen Kexing, a “teenaged runaway,” begs for admission into Tian Chuang, and Zhou Zishu, in his mid-twenties, permits the vagrant boy to be an apprentice, despite his misgivings, drawn to his intelligence, martial abilities, and fiery determination. He sends him to live in a barn, to care for the animals, and work his way up gradually, as shown in the following excerpt:

“The boy ought to hate him. He wouldn’t begrudge Kexing if he did. He’s been mucking stalls for half a year already, all through spring and summer, without the encouragement of a single lesson…his arrogance could practically be royal, but he works like a servant, and there’s no evidence of squeamishness in the way he moves around the animals or cleans out his own scraped knuckles. He fights viciously and quotes elegant lines that an educated man like Zishu ought to know but couldn’t recall from memory so easily. […] Zishu has met kind people and cruel ones, but rarely seen such a disquieting mixture of both in the same jar. The only conclusion Zishu has come to is that Zishu should not think about him so much.”

Among the other things that Zhou Zishu does not know about Wen Kexing is that he has managed to smuggle in his younger sister, for whom he cares in secret, until Zhou Zishu belatedly realizes that he has been feeding two people. This scene brings Zhou Zishu’s begrudging affection for Wen Kexing to its first crisis, because a child cannot be allowed to stay with the trainees. In addition, with this crisis comes Zhou Zishu’s first yearnings for freedom, as shown in the following excerpt:

“What if, when the snow cleared, the world had been washed away? What if it were only him and Kexing and Kexing’s feral little girl-child, left to wander through the scrubbed spring forests. To live free in the hills with no masters and no duties and no rules and no pasts at all, nothing but flowers and mushrooms and daylight. It rolls in him like a marble, that odd idea. When it reaches the top of his spine he shudders, and crushes the thought like a bug.”

Wen Kexing and his sister may be the strays of the novella’s title, but Zhou Zishu has also gone astray. He has no family, and Tian Chuang is a cruel replacement. At only twenty-five, there are already too many places in his mind where he cannot go and acts he has committed about which he cannot bear to think. And the violence continues. Zhou Zishu leaves for long months on missions, and, in one scene, assassinates a general after forcing him to sign a false confession, an episode that tells the reader truths that Zhou Zishu, still an unreliable narrator, has not yet divined. Before he dies, the general (“curious, almost amused”) says to Zhou Zishu, “Come and see me in hell when you’re finished.…I’ll want to know if you stayed this naïve all your life.”

It is not naïveté that informs Zhou Zishu’s loyalty, but only his failure to conceive of a way out. No one knows Tian Chuang as well as he, nor, therefore, the full extent of its reach, and the impossibility of leaving without taking the punishment of the Seven Nails, as shown in the following excerpt:

“He answered his cousin’s [the emperor’s] call, stepped up hungrily to take his place in the machinery of the world, and became what he is today. A good hunter, a good killer. […] But his life feels muddied now, like a puddle splashed through by a boot.…until he met Kexing he never dreamed such fool things about forests and solitude and peace, about being an idle, free man lying out to feel the wind. Sometimes when he looks at Kexing he thinks, insanely, we should run away. To what, to where, he doesn’t know. His imagination fails him past that point.”

Despite his not being able to envision a future, removing himself from the “machinery” of the emperor’s avarice and ambition begins when he becomes romantically and sexually involved with Wen Kexing. Their love is at once doomed and inevitable, and laced through with the violence of their lives. When they first kiss, Wen Kexing, canonically a cannibal in Priest’s danmei, bites Zhou Zishu’s lip a little too hard, as shown in the following excerpt:

““It’s nothing”, he says, and lips at Kexing’s fingers. “Come back”. But Kexing runs his thumb along Zishu’s mouth and it comes away pink with a thin little smear of blood. He looks dismayed. “So what?” Zishu says. Kexing can’t think it would put him off. Zishu has seen his own leg opened to the bone.”

Being inured to the abject horrors of the body and its injuries only extends to the self, of course, not the other. Wen Kexing is horrified that Zhou Zishu would take the Seven Nails to facilitate their escape into the jianghu, an escape that Zhou Zishu allows himself to dream of openly for the first time, as shown in the following excerpt:

“All this time he thought himself outside the world, above it, beyond it… This world of lakes and rivers that they have been sent to mutilate and steal from. He thought himself apart from it entirely. He planned to die in service; for someone like him there was no point in seeking out the things other men wanted. But if he can love like other men do, then he must be just the same as they are. Just one warm hand looking for another.”

Unrecognizable to himself after a life of killing, Zhou Zishu does not want a similar fate for Wen Kexing, who argues that “There’s no trap you couldn’t get out of if you wanted to. I know that much about you… If you’d fight for me, you can fight for yourself.” The lovers separate, Wen Kexing in a fury. However, each on his own comes up with a mutually assured solution, relying on the other’s innate violence (for which Strays offers various metaphors, such as: a hawk, a tiger, and a pair of wolves), and in the end the soulmates are reunited.

This narrative by orange_crushed interweaves novel and drama elements, but unhesitatingly explores the power differential of the shidi/shixiong relationship from the drama, while also complicating it in the same way that Priest’s novel blurs the roles of shou/gong. The lovers must also take on a degree of bodily harm, not only to survive Tian Chuang, but to leave it, and healing comes only after their freedom. Once again, we see a fan writer approaching different elements with an eye towards leveraging those that underscore recovery. And ultimately, taken together, fanfiction and danmei—despite vastly differing genealogies and material culture—do not infrequently depict such isolated, traumatized individuals finding that recovery through the intimacy and mirroring of same-sex romance.

5. Conclusions

In Tianya Ke, Zhou Zishu’s friend Jing Beiyuan, often given to philosophizing, makes an abstract speech about “equilibrium” in general, but actually very specifically about Zhou Zishu and Wen Kexing, as follows:

“Firstly, both sides have to be equally matched. There cannot be a stronger or weaker side, otherwise, the stronger party will devour the weaker one. Being equally matched alone won’t do either—there is a possibility that two equally-matched sides will struggle to the death to produce a victor. There still have to be a few natural, or man-made barricades that must not be crossed.…in order for such a perfect and elegant equilibrium to happen, various coincidences have to occur in tandem—in other words, the heavens have constructed it.”(62)

The characters in all three of these pieces of fiction manage to find this equilibrium; however, as we have seen, it only comes after rediscovery and integration of the autonomous self. There can be no equality and no equilibrium when either partner is less than a person, still so marked by trauma and grief that they are not human. Humanity must be earned, an injury suffered, before the “heavens” (the narrative) can make a match between soulmates. In a statement that could have been uttered by any of these characters, Bucky writes, “Any sniper knows how to become just a thing that breathes and watches while everything else passes through them like their bones are hollow and whistling in the breeze, going to the place inside you that isn’t a place at all.” Similarly, in Tianya Ke, the following is written:

“Zhou Zishu watched all of it, detached from everything as a habit. He didn’t know how to view himself as a human—someone with emotions, with a sense of right and wrong. It was for his own self-preservation; as long as he acted without thinking, he wouldn’t be driven to insanity. He was merely a pair of bloody hands on which the kingdom of Da Qing rested. Prosperity was like beautifully decorated sleeves, and his hands were forever hidden inside of them, making it difficult for people to really see him.”(27)

These damaged men know the detached, depersonalized, empty places inside of themselves intimately. Their survival of the necropolitics has been made possible by their accepting nearly lethal damage to their bodies and minds. The necessary injury, however, is the extraction strategy, which is what pulls these characters out and rescues them from imperialism’s death-grip on their agency. The Zhou Zishu of Strays thinks to himself, “It doesn’t matter what they’ve been ordered to do. They can’t go on like this.” Wounded, but gradually freed into choice via a recovery narrative and a romance that recognizes them in their specificity and particularity, they are restored to the epistemic order of things.

I have placed these three texts in conversation because danmei and fanfiction alike have evolved and continue to evolve into forms that, at their most complex and compelling, challenge neoliberal and heteronormative Strictures and argue, if not plead, for deliverance and for personal autonomy within the matrix of all but unlivable constraints. While fandom studies has moved past its initial need to lionize all forms of fannish production as transformative, subversive, and emancipatory (when many of its creations in fact reinforce and reinscribe social norms), these texts, nonetheless, collect and encode important information about both women’s writing and contemporary culture and politics and offer narratives crafted around the possibilities of liberation from social violence to the self—a construction that it is not difficult to imagine and one that might offer an important act of psychological soul-retrieval for the primarily female reader–writers of danmei and fanfiction.

I would also like to propose that the space described by Yuri Lotman’s semiosphere offers an additional model via which these texts may reflect on one another. Per Lotman has stated the following:

“The idea of the possibility for a single ideal language to serve as an optimal mechanism for the representation of reality is an illusion. […] The idea of an optimal model, consisting of a single perfect universal language, is replaced by the image of a structure equipped with a minimum of two or, rather, by an open number of diverse languages, each of which is reciprocally dependent on the other, due to the incapacity of each to express the world independently.”(Lotman 2009)

Lotman’s semiosphere is a human, cultural, phenomenological space in which new meaning can only be produced via the collision of signs jostling against one another. It is Lotman’s “mutual untranslatability” that yields this valuable parsing of reality using languages to triangulate—a maneuver that we can approximate in the digital semiosphere with precisely this kind of collocated text: Chinese, English, and derived from both. Ibrus, Hartley, and Ojamaa have described such a textual plurality as being collaborative and polyvalent, claiming that “Instead of an objective and stable artefact, given once and for all and carrying constant meanings inserted into it…The source of creativity is located in group-forming culture instead of being the property, intellectual or otherwise, of an individual creator. […] The appropriation of texts as the property of just one individual is a legal fiction, not a cultural fact” (Ibrus et al. 2021). Earlier, I described this movement as being similar to appliqué. In fact, it may be more profitably compared to quilting, where writers take pieces of a story, rearrange them in a presentation uniquely meaningful to them, and baste them down until such time as they may be needed by another author or set of readers.

Bucky says to himself angrily, of the notebooks, “can you even pretend it ain’t him you been writing to all this time?” And the reader–writers of such romances, which take place in the boundaried interstices between trauma and recovery, can locate themselves in a similar subject position. Elsewhere, Lotman has said the following:

“The semiosphere, the space of culture, is not something that acts according to mapped out and pre-calculated plans. It seethes like the sun; centers of activity boil up in different places, in the depth and on the surface, irradiating relatively peaceful areas with its immense energy. But unlike that of the sun, the energy of the semiosphere is the energy of information, the energy of Thought.”(Lotman 1990)

Online texts mutate, proliferate, and speciate near the speed of thought, and they give information beyond what they seem to offer on their moving surfaces. Lotman’s “metastructural space” barely contains what traverses it and what transgresses as it passes by; however, his project is ultimately uninterested in containment, rather only in the observation of motion, marking a Derridean trace of movement through. Nöth has said, writing of Lotman, that the notion of the boundary is vital in describing the semiosphere, as follows (Nöth 2015):

“[The boundary] divides the territory of one’s own, good and harmonious culture from its bad, chaotic, or even dangerous anti-culture. It is a frontier between an inner and an outer space. However, the boundary does not only separate, it also constitutes the semiosphere in its cultural individuality and identity. It secures the identity of the culture by creating an inner space whose boundary protects it from the influences alien to it.”

The writer–reader of light novels, of danmei or fanfiction, may consider her activity slightingly, dismissively, as in fact the literary monde does, as it long has of écriture féminine. However, in the inner protected spaces where reader–writers of danmei and fanfiction flourish, such work is centered, rather than being treated as anti-cultural and alien; moreover, the boundary filters content differently in its permeability.

Of critical importance to all three novels is poetry. The unknown narrator of Tianya Ke, who flickers in and out of view, refers to poetry freely, almost as much so as Wen Kexing, who likes to deploy it as he presses his suit (and does so in Strays as well), whereas Zhou Zishu never makes literary references, though he recognizes them. He does, however, sing, with much emotion, as does Wen Kexing, and their songs function as a heightened form of utterance, occupying a similar métier as in musical theater or opera, whether classical Chinese or Western, as an incantation to be resorted to when dialogue can no longer convey the intensity of emotion. Bucky has his myths and stories from the Talmud, and magdaliny has titled her fic after Li-Young Lee’s poem “The Interrogation.” These glimpses of poetic, musical, and mythological utterance point to the importance of distilled, compressed language as suggesting a solution to the situation of pain. The interrogation works both ways. The text interrogates the writer as much as the reader, and the language offers both an escape from strictly boundaried, rule-enforced hegemony into self-determination.

Elaine Scarry has observed that physical pain destroys language, and that “to be present when a person moves up out of that pre-language…is almost to have been permitted to be present at the birth of language itself.” (Scarry 1985) When the characters in these texts instead reclaim language—when they speak, tell stories, sing, or, for that matter, fall in love—they give this linguistic permission back to the writer–reader as well. Danmei and/as fanfiction, taken together, deftly sketch an evasion of rigid hierarchical values, moving from traumatic restriction into a rich semiotic sphere of full dimensionality—one not only of écriture féminine, but also of deep jouissance, and something even more vivid and rich: a speaking-back to patriarchy and power, as vital now as ever.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Lucy Baker, Mel Stanfill, and Katrin Tiidenberg for their assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | English is often viewed by fans as something of an official fanfiction language. Many fanfiction writers and readers prefer English, even when it is not their native language, and aver that it feels wrong to them to read fic generally, and pornography specifically, in their own language. |

| 2 | Flowers recur throughout the novel as a metaphor for freedom and autonomy. Even Zhou Zishu’s nails are scented like plum blossoms, and the poetry, which various characters quote frequently, has to do with flowers, juxtaposed against their sometimes tragic fates. |

| 3 | These dynamics are far more complex than we have time to tease out here, but they may have less to do with sexual position or kink-inflected dominance/submission and more to do with power and relatedness, in both fanfiction and danmei cultures, and our research has not begun to do either concept justice. Xu and Yang note that “rather than an ideologically incorrect reproduction of heteronormativity, the seme/uke trope could actually serve as a tool to symbolically resolve the inherent power imbalance in a hierarchical society and to achieve equality through difference” (2022). |

References

- Altenburger, Roland. 2012. Review of Stateless Subjects: Chinese Martial Arts Literature and Postcolonial History. Cornell East Asia Series 162, by Petrus Liu. China Review International 19: 297–301. [Google Scholar]

- alwaysanoriginal. 2020. Welcome to the Stevebucky Meta Collection! Available online: https://alwaysanoriginal.tumblr.com/post/617881912165466112 (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Baker, Lucy, and Jsa Lowe. 2020. Close Literary Analysis of Fanfiction as Trauma Text. Paper presented at Fan Studies Network–North America, Chicago, IL, USA, October 13. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Nanlai. 2012. Review of Gods, Ghosts, and Gangsters: Ritual Violence, Martial Arts, and Masculinity on the Margins of Chinese Society, by Avron Boretz. The China Journal 67: 233–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Shih-Chen. 2016. Grotesque Eroticism in the Danmei Genre: The Case of Lucifer’s Club in Chinese Cyberspace. Porn Studies 3: 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Lux, Cynthia Rowell, and Jia Zhangke. 2019. Searching for Dignity in the Ocean of People: An Interview with Jia Zhangke. Cinéaste 44: 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Jin. 2009. ‘Addicted to Beauty’: Consuming and Producing Web-Based Chinese ‘Danmei’ Fiction at Jinjiang. Modern Chinese Literature and Culture 21: 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Jin. 2013. Romancing the Internet: Producing and Consuming Chinese Web Romance. Series: Women and Gender in China Studies; Leiden: Brill, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, Linda. 2019. Supernatural’s Winchester Gospel: A Fantastic Midrash. In The Sacred in Fantastic Fandom: Essays on the Intersection of Religion and Pop Culture. Edited by Carole M. Cusack, John W. Morehead and Venetia Laura Delano Robertson. Jefferson: McFarland. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrus, Indrek, John Hartley, and Maarja Ojamaa. 2021. On the Digital Semiosphere: Culture, Media and Science for the Anthropocene. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Congyao. 2017. Beyond the Text: A Study of Online Communication within Slash Community in China. M.A. thesis, Wichita State University, Wichita, Kansas, May. Available online: https://soar.wichita.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/3df6d6a2-5c61-403e-a91f-4e414fd19d78/content (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Lotman, Yuri. 1990. Universe of the Mind: A Semiotic Theory of Culture. Translated by Ann Shukman. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lotman, Yuri. 2009. Culture and Explosion. Semiotics, Communication and Cognition 1. Translated by Wilma Clark. Edited by Marina Grishakova. Boston: De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- magdaliny. 2018. The Interrogation. Notebook No. 6. Available online: https://archiveofourown.org/works/14368212 (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- mercyandmagic. 2021. Was MXTX Arrested? Fact Checking Rumors Regarding the Wildly Popular Chinese Author. Available online: https://mercyandmagic.medium.com/was-mxtx-arrested-fact-checking-the-rumors-regarding-chinas-wildly-popular-author-e77559ba7a19 (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Ni, Zhange. 2018. Steampunk, Zombie Apocalypse, and Homoerotic Romance: Rewriting Revolution Plus Love in Contemporary China. Working Paper. Virginia Tech. October. Available online: https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/handle/10919/85435 (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Nöth, Winfried. 2015. The topography of Yuri Lotman’s semiosphere. International Journal of Cultural Studies 18: 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- orange_crushed. 2021. Strays. Available online: https://archiveofourown.org/works/30858098 (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Priest. 2010–2011. Tiānyá Kè (Faraway Wanderers), tr. Chapters 1–30 by Sparklingwater, Chapters 31–67 by Wenbuxing, Chapters 68–77 and Extras by Huang “Chichi” Zhifeng. Available online: https://tian-ya-ke.carrd.co/#novel (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Rogers, Carl R. 1951. Client-Centered Therapy: Its Current Practice, Implications and Theory. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Scarry, Elaine. 1985. The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stan, Sebastian. 2016. Cole (@coleisadreamer). March 14. Available online: https://www.instagram.com/p/BC697tLxpue/ (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Whitlock, Gillian, and Kate Douglas, eds. 2015. Trauma Texts: Reading Trauma in the Twenty-First Century. In Trauma Texts. Loudon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Di. 2019. The Cultural Legacy of Oscar Wilde in Modern China and Beyond (1909–2019). Ph.D. dissertation, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK, September. Available online: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/159846/1/WRAP_Theses_Wu_2019.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Xu, Yanrui, and Ling Yang. 2022. Between BL and Slash: Danmei Fiction, Transcultural Mediation, and Changing Gender Norms in Contemporary China. In Queer Transfigurations: Boys Love Media in Asia. Edited by James Welker. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Ling, and Yanrui Xu. 2016. The Love That Dare Not Speak Its Name: The Fate of Chinese Danmei Communities in the 2014 Anti-Porn Campaign. In The End of Cool Japan: Ethical, Legal, and Cultural Challenges to Japanese Popular Culture. Edited by Mark McLelland. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).