Abstract

The digital humanities are rapidly expanding access to scholarly and literary materials once largely confined to the university. No more: now, with free digital resources, like Giuseppe Mazzotta’s lecture series available for free through Open Yale Courses on YouTube, or Teodolinda Barolini’s 54-lecture long “The Dante Course”, also available for free through her Digital Dante website, academic discussions of difficult masterpieces are available to any person with enough bandwidth to handle it. I, too, made a brief foray into the digital humanities, and prior to turning to academic work, I provided a 42-lecture Dante-in-translation course which itself covered the entirety of Dante’s Comedy and sought to offer a less academic, and more accessible series of lectures on Dante than its more academic and more popular predecessors.

1. Dante and the Digital Humanities

In this Special Issue of Humanities, the authors have been asked to consider the issue of anti-academicism in Dante’s work, particularly in his Paradiso. Before I returned to academia, I was a charter school teacher, and I was tasked with building a course that would appeal to a general or high-school-level audience. From those efforts, I recorded 42 lectures guiding students through Dante’s three canticles in English translation. These recordings, as I show, have been far less popular than their more academic compatriots: Giuseppe Mazzotta’s series of lectures on Dante posted on YouTube by Open Yale Courses, which now has millions of views on even single lectures, and Teodolinda Barolini’s magisterial 54 lectures from her “The Dante Course” on her Digital Dante webpage. Since, however, the theme of the Special Issue of the journal is why Dante appears to be anti-academic in his Paradiso, it is ironic that more academic presentations of his work have received a more general appeal than my more general approach has. There is a rich—if recent—history of scholarship on digital and web-based Dante resources, including work by Michael Hemment, Leloup and Ponterio, and Amy Earhart (more general digital literary studies). Most recently, Akash Kumar has written an article which focuses on reviewing recent innovations in Teodolinda Barolini’s digital resource (2021) as well as additional recent Dante resources. Additionally, this article will utilize the methodologies of auto-ethnography1 and the recently developed digital methodology, a tool gaining popularity in both digital and archival studies.2 In particular, the work by Marc Tuters on how “views” and “likes” affect the YouTube recommendation algorithm, and that by Hazem Ibrahim et al. (2023) on the potential political biases inherent in YouTube’s recommendation algorithm which can keep videos with seemingly similar content from being suggested together. Finally, this article will serve to offer the first comparison between Teodolinda Barolini’s lecture course, Giuseppe Mazzotta’s, and a lesser-known other series of lectures given by Alexander Schmid.

In Michael Hemment’s (1998) article, “Dante.com: A Critical Guide to Dante Resources on the Internet”, Hemment laid out the condition, location, and use of critical resources available related to Dante Alighieri prior to the turn of the millennium. In his work, he summarized and analyzed the use of the Calendario Dantesco, DanteNet, Dartmouth Dante Project, Digital Dante, Guida allo Studio di Dante, Lectura Dantis, Opera del Vocabolario Italiano, Otfried Lieberknecht’s Homepage for Dante Studies, Princeton Dante Project, Progetto Dante, RAI Italica: “Area Dante”, Renaissance Dante in Print (1472–1629), Società Dantesca Italiana, and The World of Dante. I include this exhaustive list of resources which Hemment reviewed in order to show that Dante scholars and aficionados have been working diligently to create usable and lucid resources to share Dante’s work with a general audience now for almost three decades. Even in 1998, Hemment could see the value of creating and evaluating digital resources related to Dante:

Among the estimated 320 million web pages currently online, sites dedicated to Dante are among the most popular among literary-minded web “surfers”. Yet, few professions seem more at odds with the maturing technical infrastructure of online research than a specialist in medieval literature. “Going digital” somehow blasphemes the sacredness of holding an original manuscript in one’s hand, of archival research in venerable libraries centuries old, or of suddenly corroborating one’s hypothesis from a phrase in a dusty book on the bottom shelf. And yet, utilized properly, the Internet can provide literary scholars with access to more manuscripts, libraries and “dusty books” than they could ever imagine (Hemment 1998, p. 127).

Just as Hemment’s work at the time showcased the importance of searching a particular Dante site rather than a search-browser, so will this article seek to illuminate the appropriate places to find Dante courses and audio in three particularly useful places on the web.3

In their 2006 article, “Dante: Digital and on the Web”, LeLoup and Ponterio (2006) describe the now defunct “Dante Alighieri on the Web” page as follows:

This site is another example of an effort to use technology in order to make classical texts available to the public and provide a context in which the works can be read and understood. This site, maintained by an individual rather than being an institutional project, offers information about the poet, Dante Alighieri, his life, works, and time period. It is a labor of love by Carlo Alberto Furia in the Computer Science Department at the Politecnico di Milano—which just goes to prove that interest in the humanities is everywhere. His home page has a running commentary about improvements and additions to his site as well as suggestions for optimization of browser settings for proper viewing of the pages (Leloup and Cortland 7).

Although The Princeton Dante Project still has a link to Carlo Furia’s former resource on the following page (https://dante.princeton.edu/pdp/da_e.htm, accessed on 1 August 2023), the resource itself now contains only “resume” material and a very brief selection on Dante as part of its vestigial past as a digital Dante resource.4 When it was in its heyday, however, the Dante Alighieri on the Web project was the personal attempt of one person, Carlo Furia—a labor of love—as it is described by Leloup and Ponterio, and it was also intended to be a general resource available and digestible to the general public. In these two respects, Carlo Furia is an intellectual predecessor to my own project, the Alexander Schmid Podcast, which itself was an individual effort that was certainly a labor of love rather than an economically enriching endeavor, and also sought to make Dante’s life and work more accessible and graspable to a general, non-academic audience.

Amy Earhart, in her 2015 work, “The Era of the Archive”, considers the history of the digital literary space, beginning in the 1990s, and the additional, hypertextual opportunities which such resources allowed. Rather than there simply being “editions” of texts and one “final” text, digital archives could be created which could continue the work of creation as accretion and add many voices to the unitary voice of the author herself.

The archive offered possibilities that the book did not: “When a book is produced it literally closes its covers on itself”, but archives, in McGann’s mind, are “built so that its contents and its webwork of relations (both internal and external) can be indefinitely expanded and developed”. The web of relations is crucial to the archive form and is derived in large part from new historicist conceptions of the archive. Working in reaction to perceived limitations of new criticism and poststructuralist criticism, new historicists centered their research within the physical archive. Marjorie Levinson aptly calls new historicism “a kind of systems analysis”, a statement oddly predictive of the way that computer technologies would be enacted in the digital archive and an emphasis on how archives have become the sort of space in which the scholar would piece together textual interrelations. If an intervention into an archive is a sort of systems analysis, the intervention is also, in reference to Derrida’s Archive Fever, a constructed and deconstructable entity. No archive can be “without outside”. Archival instability, a legacy of Derridian conceptions of power and truth, continues to inform the way that digital literary scholars understand the work we undertake. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the 2009 DHQ special cluster entitled “Done”. Underlying this special cluster is the insistence that digital works are highly mutable and perceptions of completeness are purely subjective (Earhart 2015, p. 44).

Following in Earhart’s footsteps, then, I will attempt to add to the store of “Dante texts and materials” by analyzing and including my own contribution to the digital Dante world. Besides attempting to reach an audience outside the walls of an academic or university classroom, I also wanted to illuminate Dante’s words and thoughts in ways that his 14th century text no longer could. This leads to a consideration of the most recent scholarship on Dante in the digital world.

In Akash Kumar’s more recent work in a chapter called, “Digital Dante” from The Oxford Handbook of Dante (2021), he describes the evolution of the digital space and its relationship to the humanities and Dante as fostering a “transmedia” approach which emphasizes greater functionality and a new, unique way of experiencing the digital humanities.

There are particular trends in the wide world of digital humanities that are readily apparent in the realm of medieval studies and in Dante studies. Chief among these for the specific nature of the Commedia, perhaps, is an understanding of digital humanities as fostering a transmedia approach, “one in which students and faculty alike are making things as they study and perform research, generating not just texts (in the form of analysis commentary, narration, critique) but also images, interactions, cross-media corpora, software, and platforms”. Stephen McCormick, in laying out a history of the intersection of medieval studies and digital humanities, has made clear that one of the biggest points of contact is in the “scholarly digital edition” that can provide greater functionality in emphasizing the non-textual features and thus cause one to “experience textuality in a new way”. Pushing this point further, Alison Walker suggests that electronically mediated texts “revisit a medieval practice and create a multi-sensory reading experience” to the point that we are pushed to redefine a text as something that “encompasses a world, soundscapes and bodily understanding” (Kumar 2021, p. 96).

Like Earhart, Kumar notes and is excited by the possibilities of new forms of interaction with texts which cross traditional media boundaries and allow for new knowledge and experience. In particular, with the inclusion of new media, like music, recordings of readings, visual art representations, and theories concerning Dante’s Commedia, the digital edition allows for an experience far different and more unique than either reading Dante’s text itself alone in a physical edition and even the traditional experience of reading Dante’s text alongside a commentary. The images, sounds, and community of thinkers accessible in a resource like Digital Dante are so vivid that they can even create a sort of “virtual reality” that can really bring Dante to life for a contemporary reader (Kumar 2021, p. 107). In particular, though, the Commento Baroliniano, and its adjoining classroom lectures by Teodolinda Barolini are of the utmost interest to this study (Barolini 2014). Just like Barolini, I, too, have constructed a “Dante Course”, though hers is 54 lectures long, and my own is only 42, and though her lectures were given at Columbia University, mine were given in a non-university setting and for the general audience. Like Kumar claims about Barolini’s Commento, my own “Commento” attempts to alter and “yet embod[y] a traditional mode of reading the Commedia” which “opens out to a different sort of reading public, one that might easily be a casual reader of the poem, a student searching for guidance, or a scholar from within or without the discipline of Dante studies, and so unbinds the scholarly style that we may be accustomed to finding in the curated pages of an academic journal or volume” (Kumar 2021, p. 103).

Kumar’s final point is that translating Dante into the virtual world helps to create a “virtual experience”, like the sort one might imagine a “virtual world” or “virtual reality” giving one. He suggests that the time is ripe for contributing to this virtual world and that websites like Digital Dante, World of Dante, and others would benefit from attempts to “actualize” the elements in the poem which immerse its readers in a strange afterlife. Although my own project is not a “virtual reality” in the sense of creating an audio–video–tactile sensation throughout which one moves like a character within a video game, my project does seek to add to the “virtual reality” to which other, earlier, digital Dante scholars have already contributed and given its initial form (Kumar 2021, p. 108).5 I now turn to the analysis of my own work and its own features and relative significance compared to giants like Teodolinda Barolini and her “The Dante Course”, and Giuseppe Mazzotta and his Dante course given through Open Yale Courses.

2. Opencourseware Dante Courses and Their Relative Impact: Titans and Tadpoles

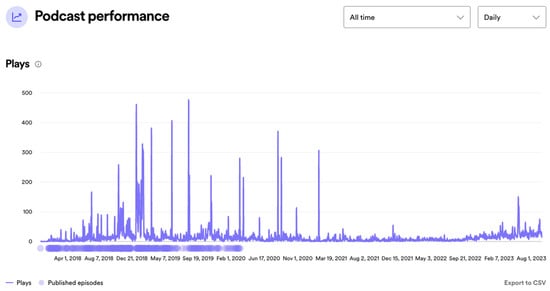

As I am writing these lines,6 the Alexander Schmid Podcast currently has 405 episodes across Anchor (now owned by Spotify) and seven other platforms.7 The total number of plays sits at 32,663; the current audience size is 43 and my follower count is 134, and the episode which has received the most “plays” is “Lecture 6: Introduction to Sophocles, Athenian Tragedy, and Antigone (Lines 1–1352)”, which has 2395 plays. The second most-listened-to episode is “Dante’s The Divine Comedy 2019/2020 Lecture 39: Paradiso’s Empyrean: Cantos 30–33”, which was published on 5 March 2020, is thirty-three minutes and thirty-four seconds long, and has been played 1571 times. Since Spotify allows donations from listeners, the podcast has a current balance of USD 28.35, which an application called Stripe is supposed to help me collect, but has remained at a steady balance for years now. The first podcast episode, prosaically entitled, “Podcast 001” was four minutes and forty-six seconds long, played 122 times, and was first published on 11 December 2017. The final podcast was published on 10 March 2020 and was the very same “Introduction to Sophocles”, which I mentioned above. Were the podcast to be practically defunct—the iron now cooling—one might think that the podcast, Dante, and my own personal star were rising. Now writing in August of 2023, however, it does not look like the popularity of my beloved podcast is trending up, though it has experienced a very slight spike over the past month according to Figure 1 below, even without new content.

Figure 1.

Anchor–Spotify podcast performance: 1 April 2018–1 August 2023.

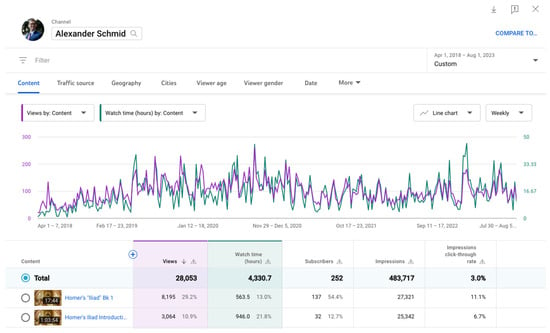

The Alexander Schmid Podcast does not only exist on Spotify and all its seven affiliated distributors, however. Since Anchor originally featured podcasts without video, and even required recording from one’s smartphone as if one were having a telephone conversation at first, I sought to share not only my voice but also my face on YouTube. I did this only in select episodes, though, since I continued to import my Anchor–Spotify podcasts to YouTube either with a black screen or cover image related to the content of the episode. On YouTube, I have uploaded 227 episodes of the Alexander Schmid Podcast, have 272 subscribers, and 28,447 total views. According to YouTube’s analytics, the most popular episode is “Homer’s “Iliad” Bk 1”, the first episode of my 2017–2018 set of lectures on Homer’s Iliad from 3 February 2018 (Schmid 2018). As of now, the episode has 8195 views (as shown by Figure 2), 144 likes, and 18 comments, many of which are complimentary. Sadly, the most watched content on Dante on my YouTube channel is an episode entitled, “Dante’s Purgatorio: Cantos 1–3” with a paltry 236 views. My most-watched episode of Dante, therefore, ranks 15th behind eleven episodes on Homer’s Iliad (323 views to 8225), two episodes on the works of Hayao Miyazaki (Nausicaa, 523 views; The Wind Rises, 363 views), and one episode on Harry Potter (786 views). To some extent, the difference between the views Dante has received on Spotify vs. YouTube makes sense; my presence on Spotify came first, and I never converted my 2019–2020 lectures on Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, Sophocles’ Antigone, and The Divine Comedy to video, and thus never uploaded them YouTube. YouTube, therefore, has slimmer pickings from my overall work, especially including my work on Dante. That said, unlike on Anchor–Spotify, my views have remained fairly consistent on YouTube, regardless of the two-and-a-half-year hiatus from producing and uploading content, as the graph below shows.

Figure 2.

YouTube video performance: 1 April 2018–1 August 2023.

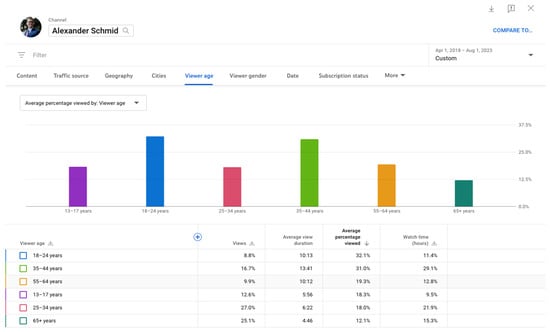

If one only considered the views alone, one might assume that my podcast had reached tens of thousands of people and was now doing the good work of providing a free education in the humanities to an international populace. The average percentage of each podcast viewers watched by age, however, tells the story that whatever knowledge I transmitted, it was certainly in partial form (see Figure 3). Those aged 35–44 listened to my work for the longest, an average of ten minutes and thirteen seconds, while those 65+ had little patience for my work, listening only for an average of four minutes and forty-six seconds.

Figure 3.

YouTube average percentage viewed by age: 1 April 2018–1 August 2023.

Across YouTube and Spotify, however, how much Dante content did I create, and in what way does it interact with the question of why Dante had an anti-academic view of the medieval academic world? On YouTube, though I have twelve separate playlists, I only have one singularly dedicated to Dante. This playlist, itself only focusing on a partial examination of Dante’s Purgatorio, is only five videos long and covers Dante’s Purgatorio cantos 1–15. Of the 227 total videos on my channel, Dante occupies squarely 2.2%, and is dwarfed by others on my playlists, like “Night School” (33 videos; 14.5%) and “Homer’s Iliad Lecture Course” (also 33 videos; 14.5%). With that said, the far larger quantity of my pre-academic work on Dante exists on Anchor–Spotify as episodes rather than videos.

Unlike YouTube, Anchor–Spotify does not have a playlist function, so all my work exists arranged according to when it was first published: newer episodes on top and older ones at the bottom of a seemingly endless homepage (https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/alexander-schmid9, accessed on 1 August 2023). Of the 405 episodes I have uploaded onto Spotify, 73 episodes across two years of courses focus on Dante’s The Divine Comedy. While only 2.2% of my videos on YouTube focus exclusively on Dante, 18% of my much larger selection on Spotify focus exclusively on Dante.8 The first set of episodes is actually a set of lectures from a 2018–2019 course I was then teaching C.H. Sisson’s 2008 translation of Dante’s Divine to secondary-education students. The lectures span from Purgatorio 1 to Paradiso 33, but sadly, of the 31 lecture episodes I uploaded, none include any lectures on the first canticle of Dante’s Commedia, his Inferno. This is made up for, however, by my second set of lecture episodes from 2019 to 2020, which not only include a full complement of lectures on Dante’s Inferno, but even include helpful summary reviews of each canticle among the 42 total episodes.

Of the five videos on Dante’s Purgatorio I have uploaded to YouTube, the one with the most amount of views is “Dante’s Purgatorio: Cantos 1–3”, with 299. Of the seventy-three episodes of Dante lectures I uploaded to Spotify, the episode “Dante’s The Divine Comedy 2019/2020 Lecture 39: Paradiso’s Empyrean: Cantos 30–33” has the most number of listens, at 1571 in total. Let us now compare the reach of my podcast and YouTube channel against the extraordinary and wide-reaching Yale courses channel on YouTube. The Yale course features twenty-four lectures by Giuseppe Mazzotta, the former president of the Dante Society of America from 2003 to 2009. These lectures largely guide the reader through Dante’s Divine Comedy, but they feature content on the Vita Nuova as well. From the very first video, however, one observes the titanic difference in scale between the influence of the Yale course and my own humble course. The first episode, named “1. Introduction”, is 18:46 long and is called by Mazzotta a lectio brevis in the episode itself. This episode was first uploaded 13 years ago on 2 October 2009. Since then, the first episode alone has garnered 212,125 views. This is already about 100 times more viewers than my most-watched episodes from Spotify and YouTube combined together, and the difference in scale does not stop there. Although there are more sparsely watched episodes only viewed in the tens of thousands, like “General Review”, which only has twelve thousand reviews, the most viewed video, “21. Paradise XXIV, XXVIII, XXIX” boasts 8,441,901 views.

Teodolinda Barolini’s extraordinary resource, Digital Dante,9 itself features a section on its home page entitled, “Dante Course”. Under that section, one finds Barolini’s full set of 54 lectures from a two-hour-long bi-weekly seminar that convened fall of 2015 through spring of 2016.

What did my podcast, with its niche appeal, have that Mazzotta’s lectures at Yale did not? First, Mazzotta’s class was condensed into 24 sessions, so he had to cut certain cantos from his analysis. Since my lectures were based on a course which covered five days a week and was also two semesters long, I was able to lecture on every single canto of the Comedy. Of course Mazzotta’s was far more academic, learned, and scholarly than my lectures, but my lectures also benefitted from the influence of watching each of Mazzotta’s lectures, often multiple times.

Answering how my course fills a gap which Barolini’s far more comprehensive 54 lectures does not is much harder to do. Largely, the appeal is different. She offers a comprehensive reading of the text, largely informed by her work The Undivine Comedy and also her Digital Dante web-resource which itself houses the lectures as well as many other resources, like art, and Italian readings of the canti. There are, however, differences in audience and academic rigor which ultimately distinguish the lectura Barolini from my own work.

First, Barolini reads from and quotes from Dante’s Comedy in Italian. Although this is a fantastic resource for graduate and undergraduate students, much like the Columbia graduates and undergraduates whom she is delivering these lectures to in her Italian W4091 and Italian W4092 classes, quoting from Italian shaves some of the broad appeal of the course off. In this way, my 42-lecture course offers a broader appeal to a more general, less-academic audience. When I quoted from the text, I quote in English, usually from Allen Mandelbaum’s, C.H. Sisson’s, or Durling’s translation. I also prepared my lectures with the general reader and strong secondary-education or early-college student in mind, whereas Barolini’s course is clearly geared toward the more advanced undergraduate and graduate students. For this reason, Barolini’s differing focus allows her to showcase a host of scholarship which I do not touch on in my lectures, and I am allowed to meander while myself making broad connections not particularly scholarly in nature. And herein may lie the difference between my course and Barolini’s. Hers was a set of university lectures for highly academic graduate students studying to be specialists and also advanced undergraduates. Since my lectures were meant for lower-level students and a general audience, I focused instead on what I thought would be most important in the text for a broader audience and how to convey the deepest and most meaningful messages from the text with powerful and modern analogies, which would illustrate the timelessness of Dante’s writing. This ultimately led to a very different product from Barolini’s which can happily exist alongside it due to its differing focus and end, and differing audience.

If only my podcast had reached this general audience, though. Sadly, even though Mazzotta’s 24-video-lecture course from Yale Courses on YouTube is also based on an upper-level Italian course, ITAL 310 in his case, it has a massive viewership. As I quoted above, its 21st episode on Paradiso 24–26 has 8.4 million views. This is curious to me because my thesis is that an academic message, and Dante’s most academic canticle, Paradiso, should be the most difficult to communicate. How then is it that an academic from Yale, by the former president of the Dante Society of America, about the most academic canticle, have the most views for any of his videos (and also of all my podcasts) on YouTube? I had to investigate this.

In Mazzotta’s lecture, he is discussing Paradiso 24–26, the canti of Dante’s testing on the virtues of faith, hope, and love, and then in 26, the linguistic canto, he meets his fellow poet, Adam (Yale Courses 2009, 21. Paradise XXIV, XXV, XXVI).10 In my own parallel podcast on Anchor–Spotify, I cover Paradiso 22–27, in order to include Peter’s excoriation of the papal seat and Church, and I only have 43 views. What, then, specifically does Mazzotta discuss in his lecture, and does this lecture have so many views because its highly academic discussion is attractive to the YouTube’s audiences, or because these concepts are so attractive to audiences or because they are so inscrutable?

In Mazzotta’s 21st lecture of his 24-lecture series, he discusses the eighth sphere of Dante’s Paradise: the abode of the Fixed Stars or Constellations. There Dante meets St. Peter, St. James, and St. John. Each saint conducts a medieval university-style examination of Dante concerning the three theological virtues of faith, hope, and love. Using the “most replayed” feature on YouTube, in the 8.4 million times this video lecture has been played, three parts of the lecture have been played distinctly more frequently than the others. Using these three discussions as rubrics, we will infer from their content whether Mazzotta’s listeners were enamored or confused. The timestamps of the three most-replayed parts of the discussion are: (1) 22:57–24:24, during Mazzotta’s discussion of faith; (2) 46:33–48:00, during his discussion of love; and (3) 1:09:26–1:10:53, during his question and answer period of the lecture. In the first most-replayed part of the video, Mazzotta begins by quoting from Paradiso 24.68ff. I will quote Mazzotta’s quoting of Sinclair’s text below, though the text Reading Dante, based on Mazzotta’s lectures curiously cites Singleton’s translation from 1991 (Alighieri 1991; Mazzotta 2014, p. 278):

Then I heard, thou thinkest rightly if thou understandest well why he placed it among the substances and after among the evidences.’ And I then: ‘The deep things which so richly manifest themselves to me here are so hidden from men’s eyes below that their existence lies in belief alone, on which is based a lofty hope; and therefore it takes the character of substance. And from this belief we must reason, without seeing more; therefore it holds the character of evidence.’ Then I heard: ‘If all that is acquired below for doctrine were thus understood, there would be no room left for sophist’s wit’. This breathed from that kindled love; and it continued: ‘Now the alloy and the weight of this money have been well examined; but tell me if thou hast it in thy purse’.(Par.24.67–85; Alighieri 1961)

The “most-replayed” indicator disappears just before Mazzotta finishes the final lines of the quote, but just after he mentions wanting to sit around a seminar table inviting discussion of the meaning of this canto. The fact that this part of Mazzotta’s lecture is so replayed, then, would seem to be precisely because it is so academic that the relationship between faith and hope is so enigmatic that it attracts additional attention and thought to itself.

The second “most-replayed” part of Mazzotta’s lecture is from 46:33 to 48:00, and Dante’s confrontation with Adam, the first human.

…‘O fruit that alone wast brought forth ripe, O ancient father of whom every bride is daughter and daughter-in-law, as humbly as I may bessech thee to speak with me. Though seest my wish, and to hear thee sooner I do not tell it’.(Par.26.91–96; Alighieri 1961)

Mazzotta brings out the academic and puzzling elements in this quote: was Adam created in a natural state or a perfect state of grace, fully ripe, without becoming; and why did he fall if he were created in a state of grace? And was it a transgression for Adam to eat from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil? In this case, though Mazzotta’s discussion ranges beyond the “most-repeated” portion of this section, the audience appears to have been curious to see what Dante’s representation of Adam was, which include questions Dante would ask Adam, and what Adam’s responses to Dante would be. Although this section is among the most repeated of Mazzotta’s lectures, my own “Dante’s The Divine Comedy 2019/2020 Lecture 37: Paradiso’s The Sphere of the Fixed Stars Pt. 2 Cantos 22–27” also contains an analysis, and while not so sophisticated and academic as Mazzotta’s, is at least as in depth and takes a look at the question individually spanning over eleven minutes (15:26–26:48) out of a total of 34:16. We also both give Dante’s definition of faith as “the substance of things hoped for, and the argument for what we cannot see”. We both also consider the tetragrammaton, though I mention its two most popular pronunciations as “Yahweh” and “Jehovah”. I did make mistakes in my lecture, like saying that many scholars do not teach the cantos of the Fixed Stars (Mazzotta, Barolini, and Cook and Herzman’s The Great Courses lectures all include lectures on The Fixed Stars (Cooke and Herzman 2001, Lecture Twenty-Three)),11 and by saying that the Hebrew Bible was written in Arabic!12 But those mistakes aside, the lecture substantively covers much of the same ground, even including some of the same quotes, and more quotes from The Epistle of James. The difference in views cannot be due to the material covered or due to the naturally intriguing or puzzling aspects of the question, but must have something more to do with the production value, prestige of the lecturer and the university at which he lectured, and also the relative age of his work compared to my own. Let us take this as the hypothesis as we move on to Mazzotta’s third “most-replayed” section of his most popular lecture.

The third “most-replayed” part of Mazzotta’s lecture is from 1:09:26 to 1:10:53, and Mazzotta’s question and answer period following his lecture. At this spot in the question–answer section, Mazzotta is explaining the ways in which Dante disagrees with Joachim of Fiore’s position that God cannot be a unity if the trinity is in fact three separate beings near the end of an almost four-minute-long response to a question (1:05:54–1:09:47). The question which prompted his compendious response was about how differing factions of Christianity appear to hold differing views on the status and nature of the trinity, and therefore, what did Dante believe? The second part of the “most-replayed” section features a long question by one of Mazzotta’s students off camera who is trying to understand how the Fall could be good, though it leads to self-knowledge. The student continues by mentioning the tension between Ulysses’ trespassing on the Purgatorial island from his speech in Inferno 26 and Adam’s trespassing on God’s law in the Garden of Eden by eating of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. Although knowledge is attained, can that really be good if the end is only reached by a crooked means; does the crooked means itself change the nature of the end and make it not good, but bad? The section concludes with Mazzotta saying that the question is very clear, and he only just begins to answer it, and spends the first minute of his response accurately restating the question (1:10:54–1:11:48). Mazzotta then spends the remaining four minutes (1:11:49–1:16:15) responding. His response is that curiosity is useful and essential to mankind but that it leads to “the violation of boundaries”, and that the fall of mankind is not an act of “mortifying” but is simply a re-establishment of values. This response to the question which occasioned it could itself alone justify the millions of views which this lecture generated with its subtlety and brilliance. The only correlation to this question and response comes at 25:45 in my own lecture when I discuss Adam’s response to Dante’s fourth question. I mention that Adam gives a “sort of geometric explanation”, saying that bounds were set; man trespassed on the boundaries; and then man receives a punishment. I expand upon this to suggest that man is simply learning “the order of the universe” and the law of cause and effect, by extension. Although I make a tropological claim based on this that one ought to look at “being disciplined” as an act not denigrating in nature but rather integrating, I do not do so with the rhetorical flare and articulated brilliance of Mazzotta. Perhaps then the difference in viewers between our lectures has to do with the difference between viewers of Yo-yo Ma playing Brahms’ Lullaby with its 1.2 million views (YoYoMaVEVO 2015) to even fellow professionals in the Newark Symphony Orchestra who have 64,306 views (Newark Symphony—Simeone Tartaglione 2014). The difference is still not as stark as the difference in views between Mazzotta’s one lecture and all the podcasts and videos I created combined, but the difference in quality may justify that division.

3. Investigating the Causality Underlying the Relative Popularity of the Openourseware Dante Courses

Although Mazzota’s and Barolini’s exalted status as Ivy-league professors could serve as a starting point for understanding their comparative success, the mechanism underlying YouTube’s suggestion algorithm could also be a factor. Marc Tuters writes the following regarding “the precise mechanisms” of YouTube’s suggestion algorithm:

I am certainly not arguing that Mazzotta’s work is extremist, or far-right, or nationalist at all. There are, however, two aspects of YouTube’s recommendation algorithm that may be working against my podcast and expanding its viewership to Mazzotta’s viewers. First, insofar as Mazzotta’s work preceded my own and reached a critical mass of views and likes (comments are disabled on the course’s videos on YouTube), YouTube’s suggestions algorithm would be far more likely to suggest Mazzotta’s work than my own while searching YouTube for Dante content. This is also true for those who find Teodolina Barolini’s work rather than my own through searching the web-browser, Google.Whilst the precise mechanisms of YouTube’s algorithms are unknown, what is clear is that they are designed to optimize ‘engagement,’ defined in terms of ‘views’ as well as the number of ‘comments’, ‘likes’, and so forth (Covington et al. 2016). In recent years, YouTube’s algorithm has been critiqued as creating a so-called ‘rabbit-hole effect’ (Holt 2017), whereby the platform’s algorithms, as mentioned above, have been accused of recommending ever more extreme content, in an effort to keep viewers engaged. It has thus been argued that this particular environment has helped to draw audience from the mainstream towards the fringe. Along these lines, it has indeed been argued that, on YouTube, ‘far-right ideologies such as ethnonationalism and anti-globalism seem to be spreaking into subcultural spaces in which they were previously absent’ (Marwick and Lewis 2017, p. 45). Academic researchers exploring this phenomenon have, for instance, found that YouTube’s ‘recommendation algorithm’ has a history of suggesting videos promoting bizarre conspiracy theorties to channels with little or no political content (Kaiser and Rauchfleisch 2018). Beyond this current ‘radicalization’ thesis, for some years new media scholars have observed that YouTube appears to multiple extreme perspectives rather than facilitating an exchange or dialogue between them.(Tuters 2020, p. 219)

The second reason is grounded in recent research but itself is hypothetical: it may be the case that Mazzotta’s work is defined by YouTube’s algorithm as politically distinct from my own. Hazem Ibrahim et al. have recently concluded a study analyzing whether YouTube’s recommendation algorithm leans politically left or right and how, if it does, it may create spaces for online “echo-chambers”. Though my work is by no means political, and Mazzotta’s work too is highly academic in nature, it is possible that three distinct features of our respective lecture series have led YouTube’s recommendation algorithm to “think” that we are on separate sides of the political fence in the United States. The first is the (1) left-leaning nature of the Ivy-league universities. The second is (2) the right-leaning nature of charter schools. The third is (3) my mentioning the name Jordan Peterson in a lecture on Homer’s Iliad which I gave in a separate course on ancient literature.

First, YouTube’s recommendation algorithm may categorize Mazzota’s Yale Courses as “very liberal”, and therefore recommend the lectures partially based on a viewer’s academic interests but also based on a viewer’s political ones. Though I do not personally know Mazzotta’s political ideology, it is well documented that professors and universities tend to skew leftward,13 which may have led YouTube’s recommendation algorithm to portray Mazzotta’s work to a largely liberal audience, an audience my work may not have been recommended to because I may have been identified as more moderate and possibly even right-leaning.

But why would my work be categorized as anything but liberal itself? I have two potential answers. As I mentioned in the opening paragraph of this article, I was a charter school teacher in California prior to re-entering academia as a scholar. How would YouTube’s algorithm have access to this information, however? On a separate playlist I developed, called “Recurrent Events”, I recorded a lecture entitled “Public Charter Schools vs. Traditional Public Schools” on 3 March 2019 (Schmid 2019).14 Although this single conversation hardly constitutes a right-leaning ideology, it is possible given Sarah Reckhow’s work below that it partially encouraged YouTube’s recommendation algorithm to sort my work into a different political category from Mazzotta’s. Just as Mazzotta’s work might be labeled as liberal or very liberal by YouTube’s recommendation algorithm due to his position as a professor and his affiliation with Yale, it is possible that my affiliation with a charter school led the YouTube algorithm to “think” that my work came from a political right-leaning perspective. Sarah Reckhow et al. (2015) show why affiliation with and showing online approval for a charter school might induce YouTube’s recommendation algorithm to categorize one on the political right:

The final reason that Youtube’s recommendation algorithm may have categorized my work as less liberal than Mazzotta’s could be my mentioning the name of Jordan Peterson in my first lecture on Homer’s Iliad on another playlist. Between 1:05 and 1:20 of my first lecture on Homer’s Iliad, I state that part of my framework for interpreting Homer’s work comes from “the Jordan Peterson terms of mapped territory… and unmapped territory, that which you have never seen” (Schmid 2018, 01:05–01:20). The single reference to Peterson’s notion of mapped and unmapped territory, is really a reference to Eliezer Yudkowsky’s notions of rationality, mapping, and territory,15 and has nothing to do with Peterson’s political ideology. But given the hot-button nature of Peterson’s name, this single reference alongside my defense and association with charter schools, may have been enough for the YouTube recommendation algorithm to categorize my work as politically right-leaning. Tuters describes YouTube’s categorization of Jordan Peterson and why the YouTube recommendation algorithm might view the use of his name as making a thinker right-leaning:Our results show some ideological division on charter schools in both contexts. In the control condition, conservatives are much more supportive of charter schools than liberals. Across the two levels of support, only 23 percent of liberals support increasing the number of charter schools in their communities compared with 49 percent of conservatives. Regarding the worst-performing districts, 32 percent of liberals support more charter schools compared with 60 percent of conservatives. The party differences are similar in scope: Republicans support charter schools at higher levels (53 percent in their own community and 63 percent in the worst districts) than Democrats (28 percent in their own community and 40 percent in the worst districts). Across the ideological and partisan spectrums, there is a greater support for charter schools in the worst districts.(Reckhow et al. 2015, p. 216)

Amongst the figures who have risen to prominence through this YouTube debate culture, is for example the now internationally well-known, Canadian academic psychologist Jordan Peterson. Peterson is often viewed as a conservative political figure, even as a member of the so-called ‘alt-right’ (Lynskey 2018). This latter term, which stands for ‘alternative right’, gained popularity in the aftermath of the 2016 US election as a means of describing a seemingly new breed of conservative online activism that brought together a diverse array of actors united against the perceived hegemony of ‘politically correct’ liberal values, often through a jokey and transgressive style (Hawley 2917; Heikkilä 2017; Nagle 2017). Whilst Peterson has refuted an association with the alt-right, in consulting how the YouTube algorithm itself categorizes Peterson it would appear that the platform nevertheless still views him in this light. How exactly this categorization works is inscrutable to all but the owners of the platform. And while it should not be taken as definitive proof of what a given channel is about, we can nevertheless assume that YouTube’s categorization does reflect some essential aspect of its bottom line, which is to keep the most people watching for the longest time possible.(Tuters 2020, p. 218)

If Tuters’ analysis of Peterson’s videos as being categorized as alt-right is correct, and if my use of Peterson’s name was a factor in how the algorithm sorts me, it could certainly be the case that my work would not be suggested alongside or after Mazzotta’s videos due to “differing political views”. This would partially account for why Mazzotta’s viewing numbers are so much higher than my own. This hypothesis, however, is predicated on the notion that my numbers would be higher if YouTube’s recommendation algorithm were to “suggest” my videos to Mazzotta’s viewers after they finish watching his own or while searching for his or Dante content in general. Even then, my viewer numbers would be far lower than his, I concede. I will conclude, however, with cause for hope from Joseph Hanson:

YouTube’s “relevance” search algorithm—the default results sorting scheme used throughout this study—”does not necessarily elevate the most educationally-sound content to the top of the results list” (ElKarmi et al. 2016). Although YouTube does not disclose the variables that factor into its search algorithm, external analysts have found that it is likely based more on elements of viewership and popularity than on actual content (Gielen and Rosen 2016). Metadata, or the titles, descriptions, and tags that video creators add to their videos themselves, may also contribute to a video’s ranking and are not verified in any way. Fortunately, YouTube results can be sorted using other metrics besides “relevance”. Findings of this study suggest that sorting results by number of views or length might enable students and parents to find educationally-valuable videos more efficiently, although additional research is needed to test this theory and account for the possibility of bias.(Hanson 2018, p. 150; my emphases)

4. Conclusions

Although Mazzotta’s work is far more successful than my own in terms of views, there is hope that since YouTube’s relevance algorithm “does not necessarily elevate the most educationally-sound content to the top of the results list”, that Mazzotta’s videos are pre-selected due to the “likes” and “views” they already have rather than because the algorithm, at least, judges his lectures as having “the most-educationally-sound content!” Again, though there may be a clear difference in quality between my lectures and those of Mazzotta and Barolini, until the YouTube relevance search algorithm is fully understood, the algorithm itself does not confirm the fact. Further, my podcast is only six years old, where Mazzotta’s is now almost fourteen, so there is time yet for my podcast to catch fire and illuminate the world. As of now, I am only short 723 subscribers and 3020 more public watch hours (in the next 365 days) to meet the minimum required standards for being monetized on my own YouTube channel.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data utilized in this study are publicly available at the links contained within the text, Notes, and References. The information from the three Figures in the text come from the private Creator Dashboards of both Anchor-Spotify and YouTube, respectively and are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The article’s methodology is an ethnography in the sense it is described below: “Analysis of ethnographic data tends to be under taken in an inductive thematic manner: data are examined to identify and to categorise themes and key issues that “emerge” from the data. Through a careful analysis of their data, using this inductive process, ethnographers generate tentative theoretical explanations from their empirical work” (Reeves et al. 2008, p. 513). The article’s methodology is an auto-ethnography because it is a reflexive consideration of my own work and therefore experience. Further, it is a virtual ethnography in that it focuses on a digital resource spread throughout digital platforms. “Newer developments in ethnographic inquiry include auto-ethnography, in which researchers’ own thoughts and perspectives from their social interactions form the central element of a study; meta-ethnography, in which qualitative research texts are analysed and synthesized to empirically create new insights and knowledge”; and online (or virtual) ethnography, which extends traditional notions of ethnographic study from situated observation and face-to-face researcher–participant interaction to technologically mediated interactions in online networks and communities (Reeves et al. 2008, p. 512). |

| 2 | “One purpose of thinking through the consequences of manual practices of website analysis concerns the kind of webs we are left with once archived, and the kind of research we are able to perform with them, as I have discussed in historiographical terms: single-site histories or biographies, event-based history, and national history” (Rogers 2013, p. 76). |

| 3 | Contrary to popular belief, using online “search engines” or “directories” such as Yahoo, Infoseek or Altavista to locate web-based Dante resources is rather inefficient for the beginner. This is because (1) it often takes a while for new pages to be added to the index of these web “crawlers”, and (2) different search engines and directories provide strikingly different results, since each uses its own version of indexing software to scan and catalogue millions of web pages. In general, “directories” such as Yahoo, which depend on humans for listings, are more discriminating than “search engines” such as HotBot, which automatically compile and prioritize all of the sites pertaining to a particular topic. A far better approach is to locate a particular Dante site with a regularly updated links page, and “Bookmark” it (for Netscape users) or “Add it to your favorites” (for Microsoft Internet Explorer users) (Hemment 1998, p. 138). |

| 4 | This is the current URL for what was “Dante Alighieri on the Web”: https://custom-resumes.net/greatdante, accessed on 1 August 2023. |

| 5 | Such a practice of reading with an aim to translate the text into the digital realm of virtual experience is, in a sense, the logical next step when considering the approach of websites like Digital Dante, World of Dante, and others that seek to render the Commedia in a multisensory way, with the visual, auditory, textual, and material aspects that are all emphasized to varying degrees. A VR Commedia would actualize much of what has endured as the appeal of the poem that immerses its readers in an afterlife that feels ever more real even as it narrates what cannot possibly be put into words. To adapt the words of Roberto Busa, we might thus arrive to a point that provokes us to exclaim: Digitus Dantis est hic! The finger of Dante is here! |

| 6 | All data were collected up to 1 August 2023. |

| 7 | The Alexander Schmid Podcast is also available on Amazon Music, Apple Podcasts, Castbox, Google Podcasts, iHeartRadio, Overcast, Pocket Casts, and RadioPublic. |

| 8 | The 227 videos I have uploaded to YouTube are only 56% as many features as the 405 episodes I have uploaded to Spotify. |

| 9 | https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/, accessed on 1 August 2023. |

| 10 | Mazzotta identifies Adam as Dante’s fellow poet because Adam is the first person to use language and is therefore a “maker of words” who “names the world” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KPJIZAmNhbw, accessed on 1 August 2023, 47:02–47:25). |

| 11 | Mazzotta considers The Fixed Stars in Lecture 21; Barolini considers the Fixed Stars in Spring Lectures 23 and 24. Herzman and Cook in Lecture 22 of 24. |

| 12 | I made this mistake in the context of relating that Jesus supposedly spoke in Aramaic. I later relate that Adam’s name comes from the Hebrew word for man, though I unfortunately never correct my slip of the tongue during the lecture. |

| 13 | “Sociological research consistently finds that American professors generally have social and political attitudes to the left of the US population. Not long after Will F. Buckley famously railed against liberal academe in God and Man at Yale (1951), a landmark survey showed nearly half of academic social scientists scoring high on index of “permissive” attitudes toward communism (Lazarsfeld and Thielens 1958). The next large-scale survey of professors’ political views, in the late 1960s (Ladd and Lipset 1976), found that just under half identified as left of center, compared to about a fifth of the US population, and that they voted 20–25% more Democratic than the American electorate. Recent studies echo these conclusions, confirming that professors are decidedly liberal in political self-identification, party affiliation, voting, and a range of social and political attitudes (Gross and Simmons 2007; Rothman et al. 2005; Schuster and Finkelstein 2006, p. 506; Zipp and Fenwick 2006)” (Gross and Fosse 2012, pp. 127–28). |

| 14 | https://youtu.be/OQR-WClnAkQ?si=BEUvl8w3G4bDp54P, accessed on 1 August 2023. |

| 15 | “But ignorance exists in the map, not in the territory. If I am ignorant about a phenomenon, that is a fact about my own state of mind, not a fact about the phenomenon itself. A phenomenon can seem mysterious to some particular person. There are no phenomena which are mysterious of themselves. To worship a phenomenon because it seems so wonderfully mysterious is to worship your own ignorance” (Yudkowsky 2018, p. 127). |

References

- Alighieri, Dante. 1961. Paradiso. Translated by John Sinclair. Oxford: Oxford Paperbacks. [Google Scholar]

- Alighieri, Dante. 1991. Paradiso. Translated by John Singleton. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barolini, Teodolinda. 2014. The Dante Course—Digital Dante. Columbia Digital Dante. Available online: https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/the-dante-course (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Cooke, William R., and Ronald Herzman. 2001. The Great Courses. Available online: www.thegreatcourses.com/courses/dante-s-divine-comedy (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Earhart, Amy E. 2015. The Era of the Archive: The New Historicist Movement and Digital Literary Studies. In Traces of the Old, Uses of the New: The Emergence of Digital Literary Studies. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 38–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, Neil, and Ethan Fosse. 2012. Why Are Professors Liberal? Theory and Society 41: 127–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, Josef. 2018. Assessing the Educational Value of YouTube Videos for Beginning Instrumental Music. Contributions to Music Education 43: 137–58. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26478003 (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Hemment, Michael J. 1998. Dante.Com: A Critical Guide to Dante Resources on the Internet. Dante Studies, with the Annual Report of the Dante Society 116: 127–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, Hazem, Nouar AlDahoul, Sangjin Lee, Talal Rahwan, and Yasir Zaki. 2023. YouTube’s recommendation algorithm is left-leaning in the United States. In PNAS Nexus. Oxford: Oxford University Press US, vol. 2, p. 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Akash. 2021. Digital Dante. In The Oxford Handbook of Dante, Oxford Handbooks. Online Edition. Edited by Manuele Gragnolati, Elena Lombardi and Francesca Southerden. Oxford: Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeLoup, Jean W., and R. Ponterio. 2006. Dante: Digital and on the web. Language Learning & Technology 10: 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzotta, Giuseppe. 2014. Reading Dante. Ne Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Newark Symphony—Simeone Tartaglione. 2014. Brahms’s Lullaby—Newark Symphony Orchestra. YouTube. August 9. Available online: www.youtube.com/watch?v=s86LeWVcWhQ (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Reckhow, Sarah, Matt Grossmann, and Benjamin C. Evans. 2015. Policy Cues and Ideology in Attitudes toward Charter Schools. Policy Studies Journal 43: 207–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, Scott, Ayelet Kuper, and Brian David Hodges. 2008. Qualitative Research: Qualitative Research Methodologies: Ethnography. BMJ: British Medical Journal 337: 512–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, Richard. 2013. Digital Methods. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, Alexander. 2018. Homer’s “Iliad” Bk 1. YouTube. February 3. Available online: https://youtu.be/YThroTj_mmI?si=2xJwf5RmpBgE3gji (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Schmid, Alexander. 2019. Recurrent Events 009: Public Charter Schools vs. Traditional Public Schools. YouTube. May 3. Available online: https://youtu.be/OQR-WClnAkQ?si=BEUvl8w3G4bDp54P (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Tuters, Marc. 2020. Fake News and the Dutch YouTube Political Debate Space. In The Politics of Social Media Manipulation. Edited by Richard Rogers and Sabine Niederer. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 217–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yale Courses. 2009. 21. Paradise XXIV, XXV, XXVI. YouTube. September 8. Available online: www.youtube.com/watch?v=KPJIZAmNhbw (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- YoYoMaVEVO. 2015. Yo-Yo Ma, Kathryn Stott—Lullaby (Brahms). YouTube. December 3. Available online: www.youtube.com/watch?v=T6nb35I9w-8 (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Yudkowsky, Eliezer. 2018. Map and Territory. Berkeley: Machine Intelligence Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).