Abstract

Bildungsroman is a genre that concerns the formation of individual identity and particularly focuses on the moral and psychological growth of the protagonist in a novel. This article aims to analyze the bildungsroman process in a dystopian context, primarily focusing on the significance of emotions in the dystopian society of Clone (2018) by Priya Sarukkai Chabria. This study scrutinizes the emotive structure of the novel based on two kinds of emotional movements: firstly, the psychic and textual movement of emotions is explored using Bharata’s rasa theory and, secondly, the spatial significance of emotions in social spaces is probed through phenomenological inquiry into the anatomy of shared emotions in the text. Through this theoretical approach, this article addresses the following questions: (a) How does a dystopian context problematize the identity formation of the protagonist in Clone? (b) How does the dystopian genre treat emotions in its structure and how instrumental are they to the identity formation of the bildungsheld in the selected novel? (c) How does Chabria manifest rasa theory and emotional movement in the structure of the novel?

1. Introduction

The German term ‘bildungsroman’ was coined by philologist Karl Morgenstern in 1819. The term stands for ‘novel of identity formation’ or ‘novel of education.’ The genre places an implicit importance on a protagonist’s psychic and spiritual journey from youth to adulthood. The dystopian context problematizes this psychic development of an adolescent protagonist, hindering the process of identity formation. Since emotions are a significant aspect of personality, they are very instrumental in dystopian imaginations that carry a bildungsroman trope—The Giver (1993), Ascendance (2018), and Clone (2018). Comprehension of emotions in a dystopian bildungsroman “allows us to further our understanding of the aesthetic, didactic, social, and cultural works of these texts” (Davis 2014, p. 51). This article is contextualized around the significance of remembrance and literature, highlighting the emotional aspects of both in a dystopian bildungsroman.

It aims to scrutinize the bildungsroman process in a dystopian context, primarily focusing on the significance of emotions to explore the identity formation of the protagonist in Clone (2018) by Priya Sarukkai Chabria. Clone is one of the most significant novels in Indian science fiction (SF). Despite being written in a Western genre, it establishes a new paradigm in Indian SF on various levels: (a) the story imagines futuristic possibilities for the caste system, which is a predominant practice in Indian society; (b) Chabria uses a distinctive narrative structure in her novel, which is somewhat inspired by the Jataka tales, where the character of Buddha embodies many forms of existence, such as a king, an animal, an outcaste, and so on; (c) the incorporation of an emotive structure. The application of rasa theory in a SF novel evinces the unparalleled significance of millennials’ old Indian literary aesthetic practice in contemporary times, which makes this study a critical and relevant intervention into Indian SF and SF in general. The article uses rasa theory and a phenomenological standpoint on emotions to analyze the emotive structure of the novel, which is central to the plot and is instrumental in the successful bildung of the protagonist. This theoretical approach addresses the following questions in this article: (a) How does a dystopian context problematize the identity formation of the protagonist in Clone? (b) How does the dystopian genre treat emotions in its structure and how instrumental are they to the identity formation of the bildungsheld1 in the selected novel? (c) How does Chabria manifest rasa theory and emotional movement in the structure of the novel?

Priya Sarukkai Chabria is a contemporary poet, writer, and translator. She channels her knowledge of Indian history, mythology, and rasa into her writings. Her major works include Andal: The Autobiography of a Goddess (2015), Generation 14 (2008), and Sing of Life: Revisioning Tagore’s Gitanjali (2021). Since she is primarily a poet and uses emotions and rasa in her translations and poems, her novel, Clone (2018), a rewriting of her debut novel, Generation 14, is also full of poetic prose and poems. Both versions of the novel have been researched with a focus on posthumanism (Maiti 2021; Karmakar 2016), casteism (Naik 2021; Khan 2018), and postcolonial fiction (Banerjee 2010). However, none of the previous studies explored the themes of bildungsroman and emotive structure in the novel, which this study carries out. The novel engages with the theme of emotions more comprehensively than its Western counterparts, The Giver (1993), The Maze Runner (2008), and Delirium (2011). It is a mise-en-abyme; there are many stories within the central narrative of the novel that have crucial importance in resurrecting the emotional faculty in the protagonist Clone 14/54/G’s psyche and in her identity formation. Thus, it depicts the role of emotions in its entirety: the textual and psychic movements of emotions, emotions as ‘affect’ influencing the protagonist’s experiences of her surroundings and herself, and the significance of emotions in social spaces. The text also points out that the lack of emotional faculty stunts the growth of the protagonist; whereas, the revival of the same results in her identity formation. Thus, the novel has an emotional structure; Chabria herself comments on the use of rasa in her writings:

…the reader equally makes the text through the way she inhabits it, imagines it, and draws significance… [also important] is the intensity it accords to ‘main’ emotions—how to draw this out, enhance it, stay with it. I found that very useful in my fiction, where I move the characters along an emotional journey rather than through planned plot development.(Barnes 2021)

In this comment, Chabria aphoristically mentions, in a way, what this article sets out to explore: how literature carries the protagonist through an emotional journey of her identity formation. Her explanation of emotions directly connects to the rasa, where a ‘permanent state’ is maintained with the help of ‘transitory emotions’ in a text. Further, one of the key ideas in this article indicates that “the expression and circulation of emotion” function as “a catalyst for” personal as well as “social change” in the selected text (Davis 2014, p. 52).

2. Bildungsroman in a Dystopian Context

Franco Moretti asserts that the traditional bildungsroman genre was about forming personal identity according to the values of modern industrial society. Maturity was supposed to be gained successfully when a bildungsheld (the protagonist of a bildungsroman narrative) eventually harmonizes his/her ‘self’ with society according to its standards. Therefore, Moretti pronounced that the conventional genre of bildungsroman and “novelistic youth [were] the symbolic form[s] of modernity” (Moretti 1987, p. 5). This harmony between the self and society became possible based on a forced “compromise” rather than a healthy “synthesis” in the 19th-century bildungsroman genre (Moretti 1987, p. 9). Contrarily, in the modernist bildungsroman2, the notion of individuality and freedom becomes dominant over forceful harmony with society; hence, the bildung “arises as a crisis” in modernist literature (Castle 2019, p. 144). Jacob’s Room (1922), Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916), and Sons and Lovers (1913) are some examples of such bildungsroman.

Moving to the late twentieth and twenty-first century, the bildungsroman genre drastically altered its course in emerging feminist, postcolonial, and dystopian fiction. Dystopian societies are often based on social, historical, and political control and use different types of surveillance to impose collective ideologies on their citizens. These surveillance conditions are also achieved and ensured using the institutional repression of emotions and culture through the manipulation of history, language repression, the destruction of art and literature, and so on. Further, in dystopian bildungsroman narratives, young protagonists do not possess any individual memories of the past; they are born and brought up in their dystopic societies. Therefore, the erasure of past literature and art becomes further important to keep them deprived of the imagination of other possibilities of their society, culture, and selves. All these factors, in a subtle way, not only contribute to maintaining cultural amnesia but also diminish the emotional capabilities of the psyche. A quintessential example of this argument can be noted in a recent Indian SF novel, Ascendance (2018) by Sadhna Shankar, where a futuristic society on an outer planet has lost strong emotions. And, like Chabria, Shankar also incorporates the past and music as a medium of the revival of “passion” (strong emotions) in her novel (Shanker 2018). This is how the conflict between individuality and society goes deeper in SF narratives. Dystopian societies often erase the prerequisites (past, emotions, monuments, language, etc.) for personal identity formation so that the very notion of individuality ceases to exist. This is why the protagonist in Clone is inquisitive about one of her dreams, “Why should anyone turn against one’s community? Besides, what else is there?” (Chabria 2018, p. 27).

Further, in the traditional bildungsroman genre, the conditions of modernity are not explicitly dealt with within the narratives; rather, the character’s compromise, growth, and changes are the focus of the texts. In other words, society’s nature was never questioned and was accepted as a given condition for a protagonist to ‘mature’ into. On the other hand, a dystopian context brings society into play by questioning and critiquing both the individual and the society. It conspicuously evinces political interference in the social and personal space of the protagonist, thereby critiquing how the state regulates the identity of an adolescent citizen. Therefore, dystopian bildungsroman texts, such as The Maze Runner trilogy (2008–2011), Escape (2008), The Island of Lost Girls (2015), the Divergent trilogy (2011–2013), and Clone (2018), firstly, scrutinize repressive social structures in their contexts and, secondly, bring about the revolutionary stance of adolescents against such despotic societies. In this regard, Carrie Hintz writes, “…explorations of personal autonomy and growth are…a way of using the transition from adolescence to adulthood to focus on the need for political action and the exercise of political will within a democratic society” (Hintz 2002, p. 255). Inferentially, it is inevitable for these plots to end with conflict rather than harmony between the protagonists and society. Where traditional bildungsroman undermines the ego, the dystopian bildungsroman solidifies it against social forces (superego).

It is also interesting to note that there is always some type of exposure to the banned, tabooed, or erased substance or ideas that let a dystopian protagonist dissent from a rigid collective ideological stance toward the other possibilities of their selves, such as Winston’s exposure to the manipulation of history at the Ministry of Truth in Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), Jonas’s to the collective cultural memory as a Receiver of Memory in The Giver (1993), and Clone 14/54/G’s to the history and memories of Aa-Aa in Clone (2018). The significant question that arises considering the argument is why dystopian regimes go to such extreme lengths to repress history, literature, and their resultant product, emotions. In The Cultural Politics of Emotion, Sara Ahmed (2004) notes that emotions and feelings, when exploited in a larger political structure, are significant in determining the fate of the status quo. Regarding the ‘emotionality of texts,’ she rightly mentions “how words for feeling, and objects of feeling, circulate and generate effects: how they move, stick, and slide. We move, stick and slide with them” (Ahmed 2014, p. 14). Her statement directly echoes a kavya’s3 power of emotional movement and sums up its literary effect on the audience, which is subtly captured in Bharata Muni’s rasa theory.

3. Rasa Theory: An Overview

In English, the word ‘rasa’4 has been understood through multiple nouns, such as sentiment, juice, taste, emotion, essence, and so on; although, it always eludes its true essence in translation5. V. K. Chari defines rasa as “aesthetic relish,” which comprises two meanings: a quality inherent in an artistic work as “emotive content” and an “experience occasioned by the work in the reader or spectator” (Chari 1993, pp. 9–10). However, this article uses the term rasa strictly in its objective sense “beyond the confines of aesthetics;” as Chari remarks, “rasa…[is] the expressed meaning of… [a] work…more specifically… [the] emotive meaning or meaning that conveys information about people’s emotions” to a reader or a spectator (Chari 1993, p. 227). It is also important to explain that the word ‘bhava’ has two connotations: ‘states’ and ‘emotions.’ First, it represents the psychic state of a character or a spectator/reader; second, it refers to the emotions that evoke a particular state or a series of states in the psyche. This article uses both translations in their respective sense: ‘state’ when the psychic domain is being referred to and ‘emotion’ when the textual domain is being referred to.

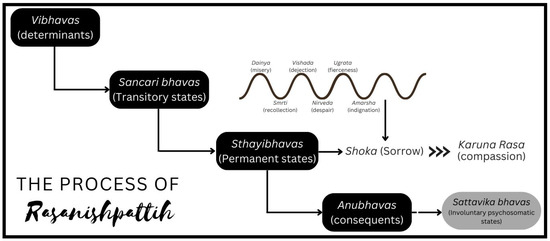

Bharata’s Natyasastra describes eight rasas in its sixth and seventh chapters, namely, “Erotic (sringara), Comic (hasya), Pathetic (karuna), Furious (raudra), Heroic (vira), Terrible (bhayanaka), Odius (bibhatsa), and Marvellous (adbhuta)” (Bharata 1951, p. 102). The ninth rasa, quietude or tranquillity (shanta rasa6), was introduced later by Udbhata in Udbhata Kavyaalankara Sara Sangraham. In the process of rasanishpattih (production of rasa), determinants (vibhavas) and consequents (anubhavas) represent the causes and the final effects in a kavya, respectively. Let us have an example; in one of the stories in the novel, the Dumb Madwoman of Dauli is lamenting over the dead body of her son in the middle of the Kalinga battlefield. Here, the dead body, the battlefield, and the blood are the ‘determinants’ (the main event, atmosphere, and context) that stimulate transitory states (sancari bhavas7), such as misery, recollection, dejection, despair, and anger, in the character (the Madwoman). While a text carries multiple transitory emotions, it always has a single dominant/permanent emotion (sthayibhava), which would be pervasive throughout a kavya (literary text); as Chari writes, “The transitory states can exist only as accessories to one of the prime emotions, serving the purpose of intensification or contrast” (Chari 1993, p. 61). The eight permanent states—love (rati), humor (hasya), sorrow (soka), anger (krodh), enthusiasm (utsaha), fear (bhaya), repulsion (jugupsa), and wonder (vismaya)—are stable emotional states “innate in every person” that correspond to and generate eight rasas in the reader/spectator (Maity 2019, p. 105). The transitory emotions surface to contextualize and maintain the permanent emotion and then disappear themselves in a kavya. Thus, the permanent emotion of ‘sorrow’ is permeated throughout The Dumb Madwoman’s story. These transitory and permanent emotions are reflected in a character’s8 behavior through his/her physical, verbal, and motor reactions, which are called consequents (anubhavas). Consequents further contain eight involuntary psychosomatic states (sattvika bhavas9), which are characters’ spontaneous bodily and psychic reactions, such as trembling, horripilation, and so on. The permanent state of sorrow and its allied transitory emotions can be observed in The Dumb Madwoman’s behavior (consequents)—crying, shouting, stroking the head of her son, and so on. The oft-quoted words of Bharata sum up this process in an aphoristic manner, “Vibhavanubhav-Vyabhichari-Samyogat-Rasanishpattih” (the accumulation [samyoga] of vibhava, anubhav, and vyabhicari bhava10 produces rasa) (Mathur 2023). Thus, the Dumb Madwoman’s story would ultimately stimulate karuna rasa (pathetic/compassion) in the psyche of the reader/spectator. Figure 1 explains the upper-discussed paraphernalia of rasanishpattih. However, as Chari suggested, this whole “layout of situation factors can be expected only in a long composition, for example, a drama, an epic, or a novel” (Chari 1993, p. 54). A short story or a lyric may incorporate one or two of the elements prominently and other elements may be briefly implied, which also should not hinder the manifestation of rasa.

Figure 1.

A diagram explaining the basic process of rasanishpattih. In the transitory and permanent states; the diagram exemplifies emotional movements in the Dumb Madwoman’s story. Different texts may produce different emotions based on their stories. However, the process remains the same. (Created by the authors).

For a successful rasanishpattih, Bharata explains the necessity of an ideal spectator in his dramaturgy. Later, Abhinavagupta incorporates the concept of sahridaya (possessed of the same heart) into Bharata’s ideal spectator11. A ‘sahridaya spectator’ is a person who firstly can put oneself into the shoes of a character by feeling the character’s emotions and, secondly, can reflect and relate one’s own experiences to the representation on the stage or in a text12. Therefore, the emotional states experienced by a character in the novel and allied emotions in a text can also be experienced by the sahridaya spectator/reader, thus generating the ‘rasa experience’ in his/her psyche.

This article draws a web of logic on how the posthuman protagonist Clone 14/54/G is portrayed as a sahridaya spectator. In every visitation (dream), which, in fact, are stories written by her original (human-ancestor) named Aa-Aa:

- (a).

- Clone 14/54/G finds herself to be a different individual or species, sensing the physical and mental experiences of those characters in a literal sense. To make a fleeting analogy, she is like a Keatsean poet showing the capacity of ‘negative capability’ by the spontaneous negation of her own “self” in order to embody the lives and perspectives of the characters in her dreams, though as a spectator, not as a poet (Kumar 2014, p. 914);

- (b).

- She judges her own existence in the Global Community based on her visitations.

Thus, she fulfills both the prerequisites for being a sahridaya spectator to experience rasas infused in the stories. While the whole process, intent, and methods of representation have changed from a traditional performance on stage, the subsequent experience of emotions is achieved and can be further intensified due to the reality-like experience of the events for Clone 14/54/G. Therefore, it is the “emotive meaning or meaning that conveys information about people’s emotions” that mediates her own experiences in the Global Community and the experiences of the characters in her dreams (Chari 1993, p. 227). The argument does not at all imply that the stories in the novel contain only emotions (they also contain history and memories) but emphasizes that ‘emotions’ are the common ground among a spectator, a character, and a writer as all three are “bound together in a common matrix” of the emotionality in a kavya (Chari 1993, pp. 26–27). On the other hand, the intensity of the rasa experience in a reader/spectator depends upon the degree of comprehension of and relatability with the events and characters in a literary work.

Rasa was introduced as a theory to scrutinize the art of dramatic representation. However, several studies advocate its relevance in literary and cinematic representations in contemporary times. In this regard, Manjura Ghosh’s recent article titled “Revisiting Bharata’s Rasa Theory” (Ghosh 2022) rightly examines its application in contemporary forms of artistic representations. Further, while Gregory Fernando (2003) and Rama Kant Sharma (2003) apply rasa to the classical fiction of Hemingway and Hardy, respectively, Gopalan Mullik (2020) and Saman Rizvi (2023) examine its relevance to contemporary cinema. This study incorporates rasa theory not as an aesthetic tool but as a medium to affect the personality of a spectator/reader; therefore, it goes beyond rasa toward a larger perspective of emotions and identity in its exploration and provides new insights into the practical significance of art and literature in life.

4. Clone: An Emotive Analysis

The novel Clone (2018) is inherently based on the tropes of memory and emotions. The text moves from personal to collective memories. Clone 14/54/G’s dreams of Aa-Aa’s memory traces are a type of personal memory; however, since Aa-Aa was a writer, the content of those memory traces (stories) falls under collective memories, thus making the clone’s experience a complex jumble of both types of memories. Here, collective memory is part of personal memory. Using rasa theory, this emotive analysis sheds significant light on how literature, as a powerhouse of emotions, helps the posthuman protagonist revive her dormant emotional faculty. It traces the movements of emotions in the protagonist’s psyche and her changing behavior throughout the text. Then, it elaborates on the significance of emotions in uniting the oppressed clone community based on their shared experiences and shared feelings, employing Sara Ahmed’s critique of emotions and phenomenological inquiry.

As a text dealing with a posthumanist subject, Clone crosses the boundary of physical aging and primarily emphasizes the psychical formation of the self and identity of the protagonist. As a bildungsroman narrative, it is the journey of a posthuman protagonist from the oblivion stage of symbolic childhood to the knowledgeable state of adulthood about one’s self-image, social realities, and future goals. All posthumans (clones, the working force; firehearts, the poets of society; zombies, the militia; and robotic dogs) are manufactured with pre-installed limited consciousness, essentialized bodies, and capacities according to their social roles, which also concretize the traditional “social class and Hindu caste” system of India (Banerjee 2010, p. 123). The prevalent social and cultural amnesia is being maintained through this physical and mental essentialist production of posthuman subjects. A group of clones is manufactured physically in the image of their original (human) and implanted with their original’s brain tissues and genes; however, they are “without…freed-consciousness” (Chabria 2018, p. 27). Therefore, it is a malfunction of ‘remembrance’ in Clone 14/54/G’s system that provides her access to Aa-Aa’s (her original) memories.

The story begins with the premise of the problem, as well as the solution, which is put forth in the first few lines of the prologue as the narrator (Clone 14/54/G) says, “…something has gone wrong with me…. I remember. My consciousness is morphing in an unplanned way” (Chabria 2018, p. 1). The expansion of consciousness through memory, past, and history in dystopian societies is a reiterative theme in Western counterparts of the genre, such as in The Dream Catcher (1986) by Monica Hughes, The Giver (1993) by Lois Lowry, and The Maze Runner (2008) by James Dashner. In such texts, ‘remembrance’ beyond a limit is often interpreted as a threat to the status quo of the presiding powers and is, thus, considered a deviancy that is sometimes not allowed and, in the case of Clone, not manufactured in the mechanical systems of clones in the Global Community (the ruling regime). It should also be noted that while Dashner’s, Hughes’, and Lowry’s novels treat remembrance as historical things and events of the past, Chabria incorporates remembrance as literature and achieves different semantic values of emotions, identity, and the past in her SF novel Clone. Further, remembrance is an act that forms a memory, which, in the novel, contains traces of history, emotions, and attachment. On the performativity of memory, Jay Winter remarks, “The performative act [of memory] rehearses and recharges the emotion which gave the initial memory or story embedded in it its sticking power, its resistance to erasure or oblivion” (Winter 2010, p. 12). Clone 14/54/G’s bowing down before her ancestor’s remains is a performative act of her original’s memory traces, which recharges the emotion of respect and reverence.

Similarly, when a thing or object holds such emotions, it becomes a memento, a relic, or a mnemonic, “giving… [it] a significance and weight… [it] would not have without the emotion” (Fuchs 2020, p. 324). This is also why certain objects and acts (mnemonics) have significance for characters in dystopian narratives, such as Winston’s diary in 1984 (1949); Deitrich’s Kuran in V for Vendetta (2005); and Clone 14/54/G’s diary in a hidden cell chip, Bullet’s eye, and an amputated hand of a gladiator in Clone (2018). The basic entity that mediates a mnemonic and a memory is an ‘emotion’ that revives a whole array of events of the past as memory and recharging the same ‘emotion’ resists the forgetfulness of one’s past and influences one’s identity in the present; as Jay Winter says, “remembrance and identity formation are braided together in powerful ways” (Winter 2010, p. 16).

In the novel, the repression of the posthumans’ sense of self is further ascertained through ‘The Drug,’ which has a similar functionality to the Soma in Huxley’s Brave New World (1932). The Drug is a regular mandatory pill for all clones. Soma, The Drug, and its many counterparts, such as Dr. Iyer’s Pill in Leila (2017) by Prayaag Akbar and Erasure in The Island of Lost Girls (2015) by Manjula Padmanabhan, benumb and pacify any emotional probability, anxiety, or mental disturbance created by overwhelming circumstances. For example, upon noticing the changes in her body, the clone became anxious, and then she “took The Drug and felt better” (Chabria 2018, p. 16). Further, it is implied in the novel that The Drug also stunts the physical growth of clones into complete humans; it ensures their exclusion from what is otherwise considered a normal—‘human.’ Both these functions of The Drug ensure their subordination and erase any possibility of dissent. Thus, when Clone 14/54/G stopped taking The Drug and took an antidote (given by Clone 14/53/G), she could reach the full potential of her mental (emotional and intellectual) and physical (menstruation, pregnancy) capacities, which directly affected her self-image.

Apart from the memory traces of Aa-Aa, emotions themselves are performative tools, which is reflected in Clone 14/54/G’s behavior. She narrates her inexplicable emotional upheaval while looking at the packed remains of her ancestor Clone 13/15/G, “It was as if the coldness had transferred into me, as if I was packed in frozen plasma” (Chabria 2018, p. 4). This incident also shows signs of her growing ego against the overpowered superego (which does not allow her to have emotions). As the story develops, the clone discovers that her dreams (remembrance) are her dead original’s (Aa-Aa’s) memory traces. The importance of these dreams and how they affect Clone 14/54/G’s psyche is explored using rasa theory in this article.

5. Rasa: Literature as a Medium for Emotions

This section highlights the two-fold significance of the visitations (dreams): firstly, it explores how the stories revive the emotional faculty in Clone 14/54/G’s psyche, which results in ontological changes in her experiences and, secondly, it highlights the significance of collective historical memory as the content of those stories which help Clone 14/54/G to form an Eriksonian ‘historical perspective’ and eventually her personal identity. The visitations that Clone 14/54/G watches are multiple stories written by her original (human) Aa-Aa, from whose DNA and brain tissues she was manufactured. Aa-Aa herself was a writer, archaeologist, and revolutionary who was killed because she spoke against the cruelty and inequality of posthumans. These dreams are the fragments of the stories from her banned book titled “Fictive Biographies, a series on histories narrated by different species who possessed equal validity and voice” (Chabria 2018, p. 139). The stories consist of different species (parrot, wolf, fish, etc.) as narrators, whose voices, actions, and narrations symbolically sign toward inclusivity and equality among all creatures on earth (including posthumans), thereby dismantling the anthropocentric social structure of the Global Community. These visitations prove to be an integral part of developing a ‘sense of self’ in Clone 14/54/G’s personality by taking her through a roller-coaster of emotions while weaving critical discourses on worldly phenomena like slavery, violence, peace, freedom, desire, killing, devotion, past, illusion, pretense, reality, sacrifice, death, friendship, ignorance, truth, and so on. The article enquires how Clone 14/54/G’s revival of emotions based on the remembrance of these stories helps her form a personal identity and results in the repudiation of her singular existence.

In her first three visitations, Clone 14/54/G dreams of a wolf named Trichaisma, of the Dumb Madwoman of Dauli during King Ashoka’s reign, and of a junior acolyte named Dhammapada during the carving of the Ajanta caves, respectively. She has first-hand exposure to these events, almost mentally sensing the skin and blood of the wolf, the Madwoman, and Dhammapada. This puts the clone “into the experience of the characters,” metaphorically marking her as an actor acting on stage as well as a spectator (Chari 1993, p. 26). She feels Tri’s fear, the Madwoman’s sadness and sorrow, and Dhammapada’s calmness.

In the first visitation, a wolf pup (Trichaisma) is separated from its family; it narrates how its family was killed by Vrikama, a tribal leader who then enslaved him. It elaborates on the accounts of the chivalry of its master (Virkama), who valiantly crossed a river on his stallion, attacked the dasyu settlers, captured Ulupi (a dasyu), and then was attacked by The Panis. In another visitation, as exemplified above, the Dumb Madwoman of Dauli is wailing over the dead body of her son on the Kalinga battlefield. And, in the third visitation, Dhammapada, an acolyte, fulfills his daily duties and encounters Buddhist art and culture. It is very significant to notice that the visitations have two-fold teleological importance in the novel. Firstly, they are set in historical sites of cultural importance from a national perspective as there are frequent references to the Indian subcontinent. Trichaisma belongs to the Vedic era, to “‘the Aryan speakers’ who spread from the Saraswati valley civilization into Central Asia from 2100 to 1500 BCE,”; Dumb Madwoman to Ashoka’s reign during the time of his conversion to Buddhism (3rd century BCE); and Dhammapada to the time of the carvings of the Ajanta caves “Between 1 BCE and 8 CE” (Chabria 2018, pp. 13, 28). These stories consist of three chronological historical scenarios: the prehistoric time of chaos and survival, the times of war and battlefields, and the time of art and peace in India. Secondly, they are thematically varied and evoke different emotions and meanings that cause Clone 14/54/G to doubt her existence as “merely [a] Worker Clone” (Chabria 2018, p. 16).

The visitations occur as intermittent flashes of dreams during the protagonist’s routine. In Trichaisma’s story, when the pup is being captured, the Moon, darkness, nighttime, coldness, and arrow through her wolf-mother’s neck are ‘determinants,’ which takes the character (Tri) through the transitory states of affliction and fright. The subsequent act of Vrikama successfully crossing the river has ‘determinants’, such as the cold white river, the old man’s words about the Bhrighu clan, and the painted pottery, which consist of suspicion, impatience, fright, joy, agitation, and pride (transitory emotions). In the next dream, when Vrikama is attacking the Dasyu settlers by breaking their dams, ‘determinants’ like overwhelming water, Vrikama’s flaming of the Dasyu clan, rising flames, the night, capturing Ulupi (a Dasyu), and Ulupi’s stroking Tri’s furs take the character (Trichaisma) through deliberation, violence, compassion, and sleep (transitory states). Similarly, when The Panis attack Vrikama’s group, the story moves through fierceness, fright, and deadliness (transitory emotions). However, what overpowers the whole narrative is a dominant presence of ‘courage’ (dominant/permanent emotion). These events cause certain reactions in characters (consequents), such as Vrikama leaping into the river on his stallion; both of them shuddering; Vrikama’s frenzied laugh; the crowd’s cheering and thumping of their breasts with the slogan, “Who will lead us across the rivers of the Sapta Sindhu? Vrikama! Vrikama!” (Chabria 2018, p. 12); Ulupi’s weeping; Tri’s sleeping in Ulupi’s arms; Vrikama celebrating his victory over the Dasyus; and the urgency in Vrikama’s words, “up, Tri, up!” during The Panis’ attack on his clan (Chabria 2018, p. 15). Further, Vrikama’s violent shuddering during the river-crossing and Ulupi’s weeping are some of the psychosomatic states in the story. These consequents reflect the psychic emotional states of the characters, thereby strengthening the understanding of the characters’ emotions for the spectator (Clone 14/54/G). Thus, corresponding to ‘courage’ as a permanent emotion, Clone 14/54/G experiences veer rasa (heroism). The visitation explores the ideas of slavery, cruelty, violence, hatred, bravery, and so on. The emotions she experiences in the visitation are reflected in her courageous act of climbing into the fighting arena to save her clone-twin Clone 14/53/G and in her feelings of compassion and pity for her clone sisters dying while working in ‘The Plasma Transfusion Centre.’ Further, the visitation forms her sense of slavery; like Tri, she is a slave to the Global Community, which exploits her existence and would not flinch at her sacrifice whenever required.

As aforementioned, dystopian protagonists often are exposed to some type of internal manipulation of the system, due to which they subvert from the collective ideology. In the story, Clone 14/54/G’s transfer to the local Museum of Civilization provides her access to probe into the historical significance and validity of her visitations and helps fulfill her curiosity. In the museum, she comes across the “Grey-Painted Pottery” artifact from the Indus Valley that she watched in her dream. The ephemerality of her existence in comparison to art unsettles her mind, “When I am gone there will be no trace of me. Why does this thought cause unease?” (Chabria 2018, p. 17). This question delineates how ‘emotions’ problematize the facticity of death for the clone. The next two visitations are triggered by her exposure to artifacts in the museum. The Dumb Madwoman’s visitation has already been discussed and Dhammapada’s story arouses shanta rasa (tranquillity) in the clone’s psyche. As Clone 14/54/G is embodying different creatures and species in her dreams, they also cause ontological curiosities about the singularity of her existence; she narrates:

“It is curious to ‘exist’ in two times and more curious to carry…an emotional-link with the past.”(Chabria 2018, pp. 15–16)

“Who now is speaking? Who am I? Clone 14/54/G.”(Chabria 2018, p. 18)

“Yet, who was I? To what species did I belong?”(Chabria 2018, p. 240)

At this stage, it needs to be reiterated that the spectator, character, and the author share the common element of emotionality in a kavya. Thus, Clone 14/54/G, as a sahridaya spectator, goes through emotions similar to those of the characters in the stories. She experiences the fear of Tri, the courage of Virkama, and the grief of Ulupi. Similarly, she also experiences the Madwoman’s sorrow, the compassion of Dhammapada, and, in the latter visitation, the disgust of Vidya-Shakti and the erotic love of the Begum. The emotion of grief provides her with a historical understanding of the futility of wars. In the denouement of the novel, she recalls the story of the Madwoman and questions herself, “Can it [compassion] spurt from a source other than sorrow, born in blood flowing” (Chabria 2018, p. 280). The deaths of clones in the final uprising remind her of the futility of the war on the Kalinga battlefield. This is how the stories carry emotions and memories binding each other into a whole; both of them help Clone 14/54/G to understand her own surroundings and form her own ‘way of life,’ her own philosophy of living, which she expresses in the last lines of the novel.

The occurrence of the visitations changes Clone 14/54/G’s identity into what the Global Community calls a ‘mutant clone.’ However, her unknown spontaneous “instinct” of “primordial survival” has helped her keep the fact hidden (Chabria 2018, p. 6). Moreover, she considers herself a deviant clone in the novel’s first quarter. It is her research into the past of her visitation that makes her doubt the reality of her existence both as a clone and a mutant. Firstly, she confirms that her dreams are not merely part of her anatomical anomaly but something of the past that “had been real” (Chabria 2018, p. 17). Then, she understands that she can experience her surroundings the same way the characters in her dreams experience theirs. Further, her scrutiny of her unknown sensations, which are different emotions, confounds her and forces her to question her existence merely as a clone. After the death of Bullet, she narrates, “I felt alone. This was a curious sensation. I did not know what I was missing. But my identity as Clone 14/54/G was incomplete” (Chabria 2018, p. 41). This is how her emotions disturb the present complacency of her singular existence and provide her with the capacity and reasons to be curious and skeptical.

While the museum works as an access to the past, the clone’s subsequent transfer to The Artificial Glade exposes her to the reality of her existence in the present. The Glade is a large fighting space for the originals’ entertainment through the demonstration of the blood and gore of posthumans (clones, gladiators, and cyborg animals).

In her next visitation, the “Vidya-Shakti” fish (power of knowledge fish), the only survivor of a destructive flood in the Ganga River of Benaras, is bragging about herself being pure and pious as she is the only creature alive in the aftermath of the flood (Chabria 2018, p. 42). Through the sights of dead animals, debris, and the disemboweled guts of creatures (determinants), the story contains agitation, disdain, arrogance, and deliberation (transitory emotions) while carrying the dominant emotion of ‘disgust.’ The clone watches the story in three dream fragments; thus, the movement of her psychic states is reflected in the changing contour of her behavior and words. The first two fragments give her hope as she compares her existence to Vidya-Shakti’s. She says, “Like the survivor fish Vidya-Shakti, I hoped I would be fortunate in my present state of actuality” (Chabria 2018, p. 46). She questions, “Am I comprised of multiple selves like the corrupted multiple versions of the religion? How soon before I am cleansed?” (Chabria 2018, p. 46). The cleansing is in reference to eliminating the anomaly of remembrance from her system and becoming her clone self again. However, the third fragment consists of a commentary on illusion and hypocrisy, “People say the worst sin is expiated by a pilgrimage to Varanasi. It’s a matter of convenience, of wrapping the veil of illusion tighter around one’s self” (Chabria 2018, p. 47). This alters her psychic state from deliberation to apprehension and fright; she expresses:

“Yet I no longer know what is the reality of my…actuality.Eyes pinned open, I seem to be wrapped in veils of deception. Either I know nothing of the world I inhabit or only the fake is real and righteous. The Global Community drapes a skin of normalcy beneath which insanity floods.What is sought to be hidden and why?”(Chabria 2018, p. 48)

The question remains unresolved for her: what is an illusion? Her present existence as a clone or the alternative notion of having the ability of humans, as she has also begun to menstruate. The whole story stimulates bibhatsa rasa (odious) in Clone 14/54/G’s psyche. It ponders upon the tropes of hypocrisy, materiality, ignorance, greed, deception, veneer, and horror. In search of the answer to her question, the clone resolves, “I had to invent my writer Original Aa-Aa as I had to invent myself Aa-Aa Clone 14/54/G” (Chabria 2018, p. 52).

The last story does not appear as a dream but comes to her as a memory. She writes it with “a scarlet lipstick” on the walls of her Recovery Pad (Chabria 2018, p. 80). The story is about a parrot narrating an illicit sexual encounter between an acrobat and the third Begum of the exalted Khan-Sahib of Lucknow, “capital of the kingdom of Avadh, shortly before the Indian Mutiny” (Chabria 2018, p. 90). It begins with, “I don’t remember ever being free” (Chabria 2018, p. 81). The captivity in the story symbolizes the parrot in its cage, the Begum in her zenana13, and the clone’s captivity in the Recovery Pad. The story consists of the permanent emotion of ‘erotic love’ (rati) and stimulates sringara rasa (erotic) in the clone’s psyche. The impact of the emotion of erotic love is reflected in Clone 14/54/G’s sexual acts and strong lascivious desire for The Leader14 (her secret lover and Aa-Aa’s son, who holds a high position in the Global Community). She expresses her carnal desires in the following words:

“Even before the doors closed I pulled him to me and started unfastening his clothes.”(Chabria 2018, p. 86)

“After he left, I would recall each move, imprint each sequence into my memory. And re-live it again. This too became a necessity.Is this what the parrot wished with my Love [Begum]?”(Chabria 2018, p. 89)

In this analysis, only a few stories are scrutinized, applying certain aspects of rasa theory. However, all of them are discussed briefly with their emotional impact on the clone’s personality and changing contours. Clone 14/54/G’s emotional development during these visitations is also reflected in the performative acts15 of her emotions, such as her assigning emotional value to things and forming attachments with particular objects: she keeps an eye of her dead companion Bullet (a posthuman dog) and the amputated hand of a gladiator from The Artificial Glade; both of them become the objects of emotions for her. She later calls the hand “a sacred relic” and seeks comfort in its presence (Chabria 2018, p. 48).

Beyond the emotional significance, these visitations carry history and philosophical discussions on multiple ideas. The visitations, thus, help the clone form a unique perspective of existence detached from the ideological stance of the Global Community. Her understanding of the futility of war and violence from the Madwoman’s story, compassion and peace from Dhammapada’s story, illusion and deception from Vidya-Shakti’s story, and courage from Tri’s story makes her observe the hidden reality of the Global Community, which has been elaborated on in this analysis.

While exploring the relation between emotions and personal identity, one must observe emotions not as abstract entities but as an underlying medium of experiences, as ‘affect.’ ‘Affect’ is not something we think of but something we think or act with; as Thomas Fuchs writes, “…emotions are ways of perceiving, namely attending to salient features of a situation [or an object], giving them a significance and weight they would not have without the emotion” (Fuchs 2020, p. 324). They provide a subjectivity to one’s perception of things, thereby providing a unique experience of the external world. The Global Community maintains a collective sameness among clones by manufacturing them as emotionless creatures. The malfunction of remembrance and the resultant emotional faculty changed how the protagonist was experiencing her surroundings. Due to the affective dimension of emotions, she was involuntarily reacting to situations differently. When Clone 14/53/G is about to be executed, the protagonist climbs into the fighting arena out of the emotion of care for her sibling clone and demands “the right to fight for Clone-twin!” (Chabria 2018, p. 58). After the death of her watchdog Bullet, she secretly kept one of its eyes as a relic because she considered it more of a companion than a watchdog. These newfound relations of brotherhood, companionship, and love, based on affective dimensions of emotions, make her realize the other plural possibilities of her ‘clone-self.’ Therefore, she comprehends, “Clone 14/54/G’ is no longer enough. I am more—and less—than what I was. Less sure, less safe, less isolated. More curious, more in pain, more resolute about my uncertainties” (Chabria 2018, p. 89). This is how emotions play a crucial role in the protagonist’s self-questioning, self-image, and identity formation. While the rasa process delineates the internal revival of emotional faculty in Clone 14/54/G’s psyche, its external significance in social spaces of uniting the posthuman and bringing an uprising in the novel is further discussed in the next section.

6. The Formation of Personal Identity

In his psychosocial identity theory, Erik Erikson introduced the term ‘identity crisis,’ which stands for a kind of anxiety and ‘identity confusion’ during the process of personal identity formation. In the novel, due to the visitations, Clone 14/54/G’s constant skepticism about the ‘sense of self,’ as elaborated in the above analysis, is this phenomenon of ‘identity crisis.’ For Erikson, it is a state when an adolescent has not yet developed an identity and is still questioning and exploring multiple ideologies for his/her ‘self.’ It is a stage of analyzing oneself through multiple lenses and deciding one’s way of life; as the protagonist in the novel determines, “I had to invent my writer Original Aa-Aa as I had to invent myself Aa-Aa Clone 14/54/G” (Chabria 2018, p. 52). On the resolution of the ‘identity crisis,’ Erikson writes:

… youth must forge for himself some central perspective and direction, some working unity, out of effective remnants of his childhood and the hopes of his anticipated adulthood; he must detect some meaningful resemblance between what he has come to see in himself and what his sharpened awareness tells him others judge and expect him to be.(Erikson 1958, p. 14)

The statement indicates that one does not merely choose but consciously forges one’s identity with all the content gained from childhood, memory, self-knowledge, experiences, understanding, intellectual capacity, and history. Further, this is also the stage where Clone deviates from bildungsroman’s traditional structure of a forced “compromise between the individual and the society” (Upadhyay 2020, p. 7). Since the Global Community does not offer any possibility of a compromise to accommodate the individuality of Clone 14/54/G, her bildungsroman would inevitably end with a ‘conflict’ rather than any artificial harmony. Her identity, therefore, works as a centrifugal force in the novel, kindling an uprising for the oppressed clone community.

At this stage, when Clone 14/54/G has developed her cognitive schema and has gained knowledge of history, the past, and ancestral roots, she is able to observe and situate her society (Global Community) in a larger perspective of multiple social structures and ideologies. This is a process that Erikson calls ‘historical perspective’—“a sense of the irreversibility of significant events and an often urgent need to understand fully and quickly what kind of happenings in reality and in thought determine others, and why” (Erikson 1968, p. 247). The development of this historical perspective and the deepening root of discontentment with the status quo reverberates at times in her narration:

“I saw no justice in this, only the presence of the Global Community that fills us with fear and makes us act on command.”(Chabria 2018, p. 95)

“The Global Community drapes a skin of normalcy beneath which insanity floods.”(Chabria 2018, p. 48)

As mentioned in the theoretical approach of the article, unlike traditional bildungsroman protagonists, Clone 14/54/G deviates from a strict oppressive ideology of the status quo and seeks validation in historical narratives for her subversive acts and beliefs. She questions the present order of things and seeks answers through her research in the museum and her experiences in The Glade. In the denouement, taking cues from her unified understanding of humans and clones, she repudiates the discrimination imposed on the bodies of clones by announcing herself as ‘human,’ as equal to the originals. She not only defies the Global Community’s ravages on clones but also disapproves of their ‘division of laborers’ as a rigid distinction among posthuman citizens by becoming a poet (climbing the social ladder), which is a designation belonging to the firehearts only.

For Clone 14/54/G, the ultimate challenge is to separate her unique self from that of her original. Once her secret is open, she is incarcerated to reveal some enigmatic memory (a revolutionary message) of her long-dead rebellious original Aa-Aa. She is transferred to Aa-Aa’s palace, given her clothes and food, and taken to the places where Aa-Aa visited, such as Gandhi Bhawan in the “suburbs of Old Bombay,” the Global Community School, and the plasma transfusion plants (Chabria 2018, p. 237). However, she repudiates all these as a symbolic protest and demands her ‘clone life’ to assert her unique identity. She demonstrates her uniqueness in the performative acts of her emotions. At the Gandhi Bhawan, instead of recalling Aa-Aa’s memories, she forms an emotional connection of her own with the ruins:

“We stayed so long that the silence and ruin seemed to become part of me. All of it entered, and settled in me…. I became the discarded body parts, the crumbling walls, the faded holograph, the forgotten memory of the Mahatma, the distorted force field light.”(Chabria 2018, p. 239)

The excerpt exemplifies the purest form of emotional performativity, where no ulterior motive is attached to this emotion of tranquillity. Further, the place metaphorically and literally symbolizes ‘peace’ since this place belongs to “the Mahatma…an apostle of peace,” and Clone 14/54/G enjoys the tranquillity of the place away from the cacophony of the Global Community (Chabria 2018, p. 238). Her experience of this place can also be interpreted as a motivation for her later-developed philosophy of non-violence and peace, though it is not explicit anywhere in the novel. The other significant aspect of the performativity of Clone 14/54/G’s emotions is her becoming a poet; she herself becomes a source of the past. She reproduces the lost works of Aa-Aa and is admitted into the firehearts’ (poets’) council by taking their solemn oath16. She becomes a connoisseur of emotions and words; she writes, “Even as I was discovering words, I was learning of their betrayal. Even as I was discovering myself, I was learning how to wear masks” (Chabria 2018, p. 245). Thus, her brief compliance with the demands of the Global Community is only a subterfuge to produce favorable conditions for a coup d’état to help The Leader reform the Global Community. In this regard, Rocío G. Davis writes, “Emotions… have revolutionary possibilities as they undermine the pre-accorded paradigms of political stability” (Davis 2014, p. 61). A perfect example of Davis’s remark is Clone 14/54/G’s poem:

“Which war are you speaking of my friends?The one in Hiroshima, New York, Syria?…Which bloody Kurukshetra doyou wish to speak of?……Your hatred, yourhopeless manoeuvres againstdeath, and your helpless defeat.”(Chabria 2018, pp. 101–2)

Although the novel centers around one clone, it is implied that she is symbolizing all the marginalized, “The Kafir Others,” as well as the mutants, and empowering them through her declaration (Chabria 2018, p. 267). In the novel, other mutants, Clone 14/53/G and the gladiator, help her at the cost of their lives. What prompts these unpredicted actions are their (clones’) shared bodily existence and the performativity of their shared feelings of pain, plight, compassion, empathy, and so on. Therefore, it needs to be established that emotions are not merely subjective but they also have spatial value in social space; in The Cultural Politics of Emotion, for instance, Sara Ahmed (2014, p. 4) explores “how emotions circulate between bodies…how they ‘stick’ as well as move.” Elsewhere, while explaining the circulation of emotions in social spaces, Ahmed (2004, p. 120) writes, “Emotions work as a form of capital: affect does not reside positively in the sign or commodity, but is produced only as an effect of its circulation.” The uprising in Clone happens in this manner; the unexpressed emotions of suffering and brutality do not have social value in the individual psyche but only gain momentum through their performativity, through their circulation among bodies, through expressing them in words and actions as Clone 14/54/G does. From this point of view, literature can also be observed as a medium of the circulation of emotions; furthermore, it is a considerably significant medium since it can cross the boundaries of time and place and reach the farthest of future and places. This seems to be the reason why firehearts could only survive on memory pills so that the Global Community could control their emotions. Moreover, this is also the reason why Chabria makes her protagonist a poet who can use those emotions to unite the oppressed and revolutionize society. At the celebrations, Clone 14/54/G voices her opinion against the rampant discrimination and brutal exploitation of clones by claiming her humanity. She proclaims, “The secret is that I am human. Each one of us is human. We still have the capacity to live as humans” (Chabria 2018, p. 269). Her proclamation kindles a revolution and clones rise, shouting the slogan, “I claim my birthright to be human” (Chabria 2018, p. 269). The self-declaration of Clone 14/54/G as a human is also supported by the physical changes of growing pubic hair, experiencing menstruation, and experiencing pregnancy in her body. These transformations alter how she perceived her body in the past as “merely a Clone” and how she perceives it now as equal to a ‘human’ body (Chabria 2018, p. 80).

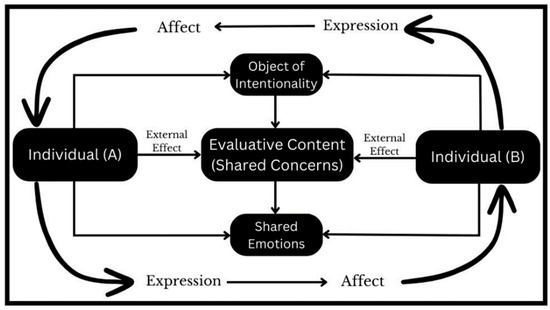

A phenomenological exploration also aptly captures the significance and spatial ontology of emotions in the novel. In this regard, Robert C. Solomon emphasizes that there is always an object of every emotion and “this feature of emotions can be called their intentionality; all emotions are about something” (Solomon 1993, p. 112). It is the ‘affectivity’ related to the intentional object that generates emotions. And, when a multitude identifies a common object of intentionality of their emotions, they share the same concerns (see Figure 2), which then indicates a common requirement of a joint action leading to “the sense of agency for a joint outcome” or “the sense of we-agency”17 (Pacherie 2014). Mikko Salmela and Michiru Nagatsu point out a discrepancy in Elisabeth Pacherie’s theory and insist that “an agentive sense of we-agency…emerges from shared emotions in joint action” for the joint outcomes; both of them have a mutually amicable relationship (Salmela and Nagatsu 2017, p. 456).

Figure 2.

Evaluative content refers to the value Individuals A and B assigned to the object of intentionality, which then determines the degree of their shared concerns. ‘External effect’ refers to how ‘shared concerns’ are affected (adversely or favorably) by external circumstances, which then gives rise to corresponding emotions. (Figure created by the authors).

The presence of other mutant clones, aside from Clone 14/54/G, with similar emotional upheaval is frequently hinted at in the novel; for instance, Clone 14/53/G tells Clone 14/54/G, “You are mutating… it has happened to me.” “The Others will reach you” (Chabria 2018, p. 49). It is also implied in the novel that mutants are uniting and preparing for a revolution in secret; thus, they have the same object of intentionality: equality. The shared concerns regarding the intentional objects are rightly reflected in Clone 14/54/G’s words, “I…am ‘one of them,’ am I not? I too was meant to work till my actuality ran out. I too was supposed to live under the [oppressive] rules the children sang about” (Chabria 2018, p. 235). These shared concerns of the clone community find the appropriate emotions and values in social spaces at the proclamation of the protagonist, which gives “rise to the kind of non-reflective absorption in shared emotional experience in which the evaluative and affective dimensions18 of emotion become thoroughly intertwined…taking the form of a phenomenological fusion of feelings into ‘our’ feeling” (Salmela and Nagatsu 2017, p. 458). This ‘our’ feeling is also a result of the cyclic process of expression and affect among clones, as shown in Figure 2. The eventual formation of the ‘agentive sense of we-agency’ emerges from this ‘our’ feeling of the shared emotions of the clone community in the novel. Figure 219 summarizes this discussion on Clone and represents the anatomy of ‘shared emotions’ based on Salmela and Nagatsu’s paper.

At this stage, the protagonist has resolved the ‘identity crisis,’ has ascertained her future directions, and has demonstrated her stance as a symbol of hope for the Kafir Others and the mutants. Therefore, emotions are weaved centrifugally in the novel, moving from personal to collective. Amidst the chaos, Clone 14/54/G’s poetic sensibility kindles; she contemplates the Madwoman’s question to Asoka, “What is the wellspring of compassion?” and the answer is, “love tremendously beyond myself. This is the only way” (Chabria 2018, pp. 280–81, emphasis added). Love is one of the strongest emotions, which is frowned upon in many dystopian imaginations, from Brave New World (1932) and 1984 (1949) to Delirium (2011). Moreover, Lauren Oliver’s Delirium goes on to implicate love as a disease. A similar plotline of depriving people of their emotional capacities is also presented in Luis Lowry’s The Giver (1993), in which citizens are “prohibited from access to historical and cultural memory…art and music, with their attendant passions such as fear, pride, envy, sorrow, joy, and love” (Davis 2014, p. 54). Thus, the revival of emotions in Clone is crucial for the protagonist’s successful bildungsroman. The denouement shows that the protagonist has gained agency and has decided her own way of life is to be a poet and to revolutionize society like her original. The novel ends with her writing an alternative ending to Aa-Aa’s story of Trichaisma, who hails the Gods while advocating the clone’s own philosophy of non-violence in the following words:

“Heaven, Earth, Breeze of the mountains and of the plains, may the killing stop.…Pollen, all that moves and does not, may we be at peace.Hear this call of Trichaisma, the Three-Eyed.Hear me, you Gods.”(Chabria 2018, p. 283)

7. Conclusions

Like many other dystopian bildungsroman texts, such as Escape (2008), The Giver (1993), and The Hunger Games (2008), the plot of Clone follows a deviant structural pattern to the traditional bildungsroman, where an adolescent protagonist surviving in an oppressive society is somehow exposed to the hidden realities of his/her world. Subsequently, in the impossibility of the traditional compromise between individual and society, the bildungsheld challenges the status quo not only to gain a ‘sense of self’ but also to revolutionize society. The article highlighted the instrumentality of emotions in the dystopian genre; explored the crucial relation between literature, emotion, and identity; and proved the relevance of rasa theory in contemporary literature. Chabria’s use of emotions in the bildung process of her protagonist unfolds new intricacies in the paradigms of control and repression in dystopian texts. Using an emotive structure, Clone subtly penetrates the well-structured ideological mechanism of control and evinces the teleological impact of historical and cultural amnesia on identity to its core. Therefore, her novel offers a deeper perspective than the above-mentioned texts to scrutinize the relations of history, memory, and identity under the overarching theme of emotions.

The article significantly contributes to the current scholarship in Indian SF and bildungsroman genres by exploring the role of emotions in the process of the personal identity formation of the protagonist Clone 14/54/G in the dystopian world of Clone. It scrutinizes the emotive structure of the novel based on two kinds of movements of emotions: (a) Clone 14/54/G’s reviving of her emotional faculty in her psyche through literary pieces (which is scrutinized using rasa theory); (b) the performative aspects of emotions and their circulation in the external social spaces (explored using phenomenological inquiry on emotions). While the psychic revival of emotional faculty lets Clone 14/54/G experience and judge her surroundings with personalized values, the performative aspects of emotions function as expressive tools of dissatisfaction and discontentment. While the first movement marks the realization of oppression in the individual psyche, the second one functions as a social resistance to that oppression. Thus, the article concludes that emotions and personal identity together function as resistance against oppression and discrimination in the novel. The analysis of the text further signifies that dystopian regimes separate the present from the past by destroying literature and manipulating historical records to limit the psychic capacities of its citizens to extrapolate their regimes. In other words, the two movements explain the fundamental mechanisms of emotions in dystopian bildungsroman and that the psychic suppression of emotions erases any possibility of them (emotions) being used in social spaces so there should be no dissent in the future. This also echoes the famous Orwellian dictum in Nineteen Eighty-Four, “He who controls the past controls the future. He who controls the present controls the past” (Orwell 2021).

Further, the article implicates the notion that there are always ideological aspects involved in the sustenance of oppressive systems. If the lack of emotional faculty makes clones believe their essentialist inferiority to humans, they will remain subordinated indefinitely. In the same line of thought, the novel simulates the prevalent caste system in India, where people ideologically distance themselves from and discriminate against others based on the caste they are assigned at birth. This caste system in India is extrapolated because people ideologically believe in their own ‘castes’ as their essentialist destiny. Therefore, the article also provokes its readers to question such oppressive institutions of society that are being sustained based on certain ideological factors.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to developing the main idea and theoretical framework of the article. The first and final drafts of the manuscript were written by the author, S.J. (Shreyansh Jain), under the supervision of the coauthor, S.J. (Smita Jha). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The protagonist of a bildungsroman text. |

| 2 | ‘Modernist literature’ refers to early 20th century literature. |

| 3 | As V. K. Chari mentions in his book, ‘poetry’ from English and ‘kavya’ from Sanskrit are understood in a broader sense of all ‘imaginative literature.’ The word is used only in this sense throughout this article. For more, see Chari’s Sanskrit Criticism (1993), p. 227. |

| 4 | Different theorists have translated the term ‘rasa’ differently. V. K. Chari uses the word in its original form, suggesting ‘aesthetic relish’ as its translation, whereas Manmohan Ghosh uses ‘sentiment.’ |

| 5 | We found multiple translations and meanings in English for a single Sanskrit term. The English language frequently lacks precise parallels to the words representing different bhavas (emotions or states) in Sanskrit, or scholars tend to use different synonyms for words in Sanskrit. Therefore, we are taking the liberty of using different translations at different places for a single bhava in Sanskrit as Vinay Dharwakdar’s paper demonstrates multiple connotations of a single bhava. For an exhaustive list of translations of Sanskrit terms, see Dharwadker’s “Emotions in Motion,” pp. 1398–400. |

| 6 | However, it was Abhinavagupta’s defense of shanta rasa that resulted in its inclusion in mainstream rasa theory. See Masson and Patwardhan’s SantaRasa and Abhinavagupta’s Philosophy of Aesthetics (1969). |

| 7 | Also called vyabhicari bhavas. To know all 33 transitory states with a comprehensive translated list, see Dharwadkar’s “Emotion in Motion,” p. 1398. |

| 8 | ‘Character’ refers to a person or a creature in a text or a play, not the spectator or reader. |

| 9 | The eight involuntary psychosomatic states are paralysis, perspiration, horripilation, change of voice, trembling, change of color, weeping, and fainting. For their Sanskrit words and other probable translations, see Dharwadkar’s “Emotion in Motion,” p. 1399. |

| 10 | Also called sancari bhava (transitory emotions). |

| 11 | See Maity’s “Genre Fiction and Aesthetic Relish,” p. 105. |

| 12 | As Maity writes, “the term ‘sahridaya’, retained from earlier usage, is usually combined with pāthak or reader.” For more, see “Genre fiction and aesthetic relish” p. 106. |

| 13 | A particular area of a palace used to be reserved for household women in 17th-century Indian Hindu and Muslim families. |

| 14 | See Clone (2018), chapter 35, p. 86. |

| 15 | By performativity of emotions, the authors mean ‘beyond mere feelings’–the teleological or functional aspects of emotions. |

| 16 | See Clone (2018), p. 244. |

| 17 | Elisabeth Pacherie’s phenomenological inquiry distinguishes between ‘a sense of agency for joint outcome’ and ‘the sense of we-agency.’ In the first case, individuals strive to achieve a common goal/object; thus, they come together to play individual parts in a joint mission, whereas, in the second, individuals dilute one’s self for a collective goal; it is at the cost of one’s individuality that the we-agency is gained according to Pacherie. For more, see Salmela and Nagatsu’s “How does it really feel to act together? Shared emotions and the phenomenology of we-agency,” p. 454. |

| 18 | The affective dimension stands for the bodily, mental, or motor manifestation of emotions. The affective dimension is reflected in all mutant clones shouting the same slogan, raising their arms together in support, which demonstrates the ‘our’ feeling. |

| 19 | This diagram is strictly limited to Salmela and Nagatsu’s explanation of ‘shared emotions.’ It is tenuously condensed to explain the representation of ‘shared emotions’ in the novel. For more, see Salmela and Nagatsu’s paper, pp. 456–58. |

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2004. Affective Economies. Social Text 22: 117–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Sara. 2014. The Cultural Politics of Emotion, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, Suparno. 2010. Other Tomorrows: Postcoloniality, Science Fiction and India. Available online: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3181 (accessed on 6 May 2023).

- Barnes, Elodie Rose. 2021. In Conversation with Priya Sarukkai Chabria: ‘It’s Only through Stutters That We Can Approach the Sacred’. Lucy Writers Platform. October 21. Available online: https://lucywritersplatform.com/2021/10/21/in-conversation-with-priya-sarukkai-chabria-its-only-through-stutters-that-we-can-approach-the-sacred/ (accessed on 4 May 2023).

- Bharata. 1951. The Natyasastra: A Treatise on Hindu Dramaturgy and Histrionics. Translated by Manomohan Ghosh. Calcutta: The Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal. Available online: http://archive.org/details/NatyaShastra (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Castle, Gregory. 2019. The Modernist Bildungsroman. In A History of the Bildungsroman. Edited by Sarah Graham. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 143–73. [Google Scholar]

- Chabria, Priya Sarukkai. 2018. Clone, 1st ed. New Delhi: Zubaan. [Google Scholar]

- Chari, V. K. 1993. Sanskrit Criticism, 1st ed. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited. Available online: http://archive.org/details/qYEG_sanskrit-criticism-of-v.-k.-chari-motilal-banarsidass-publishers-private-limited-delhi (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Davis, Rocío G. 2014. Writing the Erasure of Emotions in Dystopian Young Adult Fiction: Reading Lois Lowry’s The Giver and Lauren Oliver’s Delirium. Narrative Works: Issues, Investigations, & Interventions 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Erikson, Erik H. 1958. Young Man Luther: A Study in Psychoanalysis and History. New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc. Available online: http://archive.org/details/youngmanluther0000erik (accessed on 19 May 2023).

- Erikson, Erik H. 1968. Identity, Youth, and Crisis. London: Norton. Available online: http://archive.org/details/identityyouthcri0000erik (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Fernando, Gregory P. 2003. Rasa Theory Applied to Hemingway’s ‘The Old Man and The Sea’ and ‘A Farewell To Arms’. Ph.D. dissertation [unpublished], St Clements’ University, Turks and Caicos Islands. Available online: https://stclements.edu/grad/gradfern.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Fuchs, Thomas. 2020. Embodied Interaffectivity and Psychopathology. In The Routledge Handbook of Phenomenology of Emotion, 1st ed. Edited by Thomas Szanto and Hilge Landweer. London: Routledge, pp. 323–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, Manjura. 2022. Revisiting Bharata’s Rasa Theory: Relevance, Applications, and Contemporary Interpretations. RESEARCH HUB International Multidisciplinary Research Journal 9: 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintz, Carrie. 2002. Monica Hughes, Lois Lowry, and Young Adult Dystopias. In The Lion and the Unicorn. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 26 vols, pp. 254–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, Manali. 2016. Interrogating the Past and Speculating the Posthuman Future in Generation 14. Open Inquiry Archive. January 14. Available online: https://openinquiryarchive.net/2016/01/14/interrogating-the-past-and-speculating-the-posthuman-future-in-generation-14/ (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Khan, Sami Ahmad. 2018. The Annihilation of Cloning: Caste and Cloning in Priya Sarukkai Chabria’s Generation 14. Muse India: The Literary Ejournal 79. Available online: https://museindia.com/Home/ViewContentData?arttype=feature&issid=79&menuid=7819 (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Kumar, Mukesh. 2014. John Keats- The Notion of Negative Capability and Poetic Vision. International Journal of Research 1: 912–18. [Google Scholar]

- Maiti, Anwesha. 2021. Identity Formation as a Site of Resistance: An Investigation into Posthuman Identities through Priya Sarukkai Chabria’s Clone. Anudhyan: An International Journal of Social Science 6: 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Maity, Anwesha. 2019. Genre Fiction and Aesthetic Relish: Reading Rasa in Contemporary Times. In Indian Genre Fiction: Pasts and Future Histories. Edited by Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay, Aakriti Mandhwani and Anwesha Maity. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur, Priyaankaa. 2023. Natyashastra: A Study of the Underlying Unity of All Arts. The Raaga Room. Available online: https://theraagaroom.com/natyashastra (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Moretti, Franco. 1987. The Way of the World: The Bildungsroman in European Culture. London: Verso. Available online: http://archive.org/details/wayofworldbildun0000more (accessed on 4 May 2023).

- Mullik, Gopalan. 2020. Bharata’s Theory of Aesthetic Pleasure or Rasa: Classical Indian Theories of ‘Aesthetics’ and Their Relation to Cinema. In Explorations in Cinema through Classical Indian Theories: New Interpretations of Meaning, Aesthetics, and Art. Edited by Gopalan Mullik. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 197–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, Priteegandha. 2021. Dalit-Futurist Feminism: New Alliances through Dalit Feminism and Indian Science Fiction. Journal of International Women’s Studies 22: 106–22. [Google Scholar]

- Orwell, George. 2021. Nineteen Eighty-Four. London: Arcturus Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Pacherie, Elisabeth. 2014. How Does It Feel to Act Together? Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 13: 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, Saman. 2023. Locating Natyashastra: The Warp and Woof of Indian Cinema. Jamshedpur Research Review 4: 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Salmela, Mikko, and Michiru Nagatsu. 2017. How Does It Really Feel to Act Together? Shared Emotions and the Phenomenology of We-Agency. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 16: 449–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanker, Sadhna. 2018. Ascendance. New Delhi: Rupa. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Rama Kant. 2003. Hardy and the Rasa Theory. Delhi: Sarup & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, Robert C. 1993. The Passions: Emotions and the Meaning of Life. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub. Co. Available online: http://archive.org/details/passions00robe (accessed on 24 July 2023).

- Upadhyay, Abhishek. 2020. Postcolonizing a Genre: The Bildungsroman and India. Ph.D. thesis [unpublished], Utkal University, Odisha. Available online: https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in:8443/jspui/handle/10603/401825 (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Winter, Jay. 2010. The Performance of the Past: Memory, History, Identity. In Performing the Past: Memory, History, and Identity in Modern Europe. Edited by Karin Tilmans, Frank van Vree and Jay Winter. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).