2. The Contents of the SCP Foundation

SCP Wiki

4 is a collaborative writing website that has an immense collection of disturbing and bizarre stories about entities with supernatural powers that are potentially damaging to humanity. The site presents itself as a crossroads between the imaginary and the documented, to which the large community of collaborators can contribute either with fictional content or with elements of encyclopedic documentation with iconographic references. Since 2007, SCP Wiki has started to develop a complex alternative universe populated by monsters and anomalies, which has been the source of inspiration for several different types of media: books, plays and video games. Minecraft, the world-construction game, is one of the most famous examples of a platform where places and creatures described on the SCP Wiki site are found.

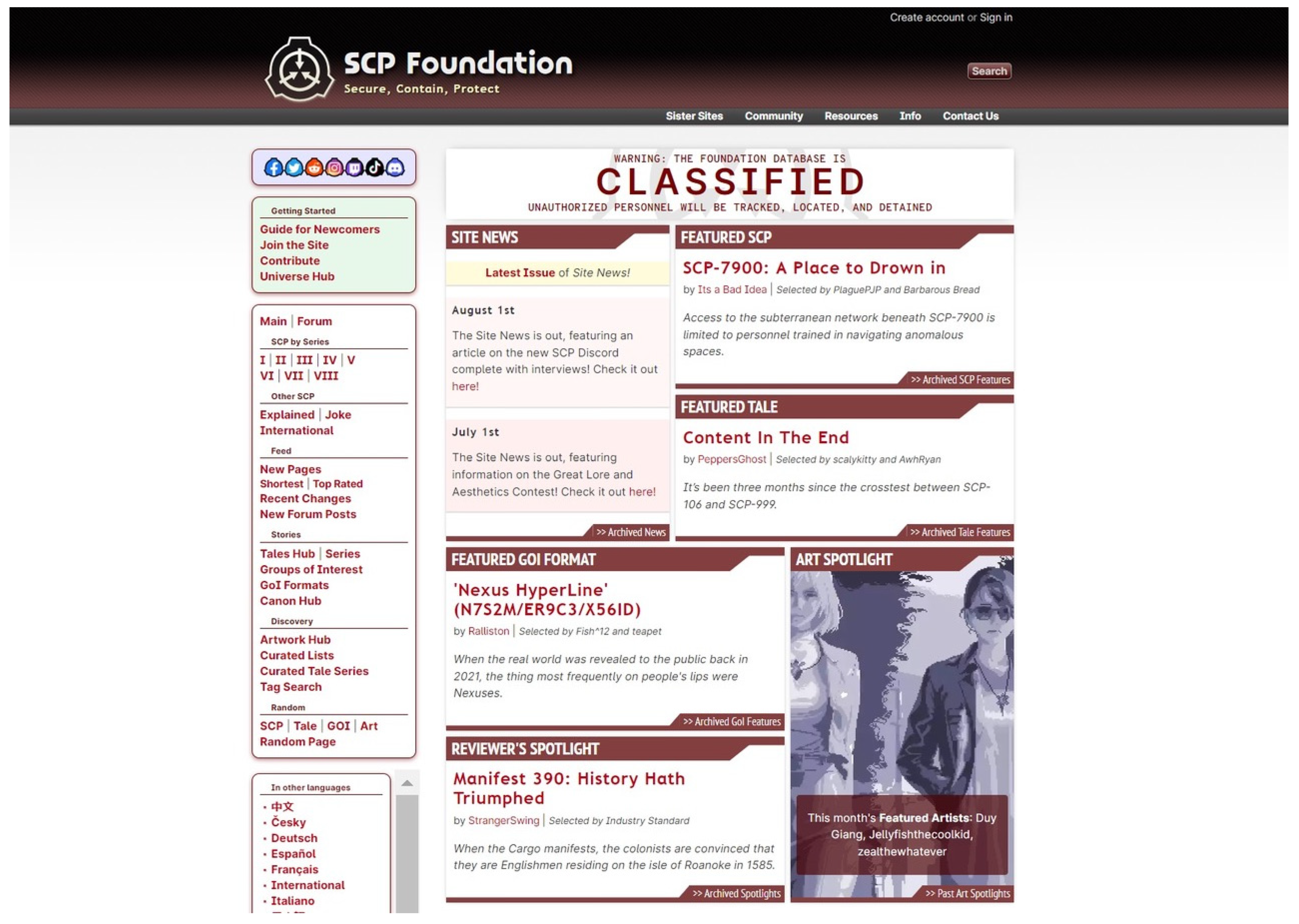

In the imaginary universe of SCP, in which mankind is constantly threatened by the supernatural, the Foundation operates in almost total secrecy. It is a ghost-like organization composed of researchers and military personnel that captures the entity of SCP in its own structures in order to study their competencies, classify them and contain their effects. The site is its official communication organ; the following is written in bold on its homepage: “WARNING: THE FOUNDATION DATABASE IS CLASSIFIED ACCESS BY UNAUTHORIZED PERSONNEL IS STRICTLY PROHIBITED. PERPETRATORS WILL BE TRACKED, LOCATED AND DETAINED”. (Cfr.

Figure 1).

It appears to be the site of a big governmental organization rather than being something entirely editable, and it is immediately difficult to understand what the Foundation really is or if it is geographically traceable. The administrators’ and contributors’ identities are hidden behind nicknames, and although there are informative and documented sections, these have clearly been partially or fully censored. There are also images and maps, for example, of the dislocation of SCPs in Italy. Its communicative aspects seem to have been planned carefully, giving this project a great ability to expand itself, aided, of course, by the accessibility to the web but also by the propensity to reproduce the disturbing tone of some public communication and to imitate contemporary stereotypes with a dose of irony. Through word of mouth, the site has become a small phenomenon of the web, able to take full advantage of one of the paradoxes of the digital era: the absence of a physical location does not mean that a place does not exist.

As stated in the introduction, the abbreviation SCP stands both for the Foundation’s motto, “Secure, Contain, Protect” and for “Special Containment Procedures”, which are specific settings that are often extravagant and creative and which the Foundation uses to contain anomalies. It is, therefore, a cold, cynical prison dedicated to the safety of the human race; however, it leaves room for doubt in the reader’s mind with regard to its ethical principles: is it good or evil?

The database of the mysterious entities detained within the walls of the Foundation is the main content of the site. The entities are classified on the basis of how difficult they are to contain, with the SCP abbreviation followed by an identification number. They are also organized numerically, with each entity containing 1.000 SCP articles. The community is currently working on the compilation of the VI series. There are three levels of classification: Secure, Euclid and Keter. Obviously, this kind of classification obscures the monstrosity that can hide behind each level.

The items that the Foundation considers to be secure pose either a small threat to people or none at all because although they are dangerous, they are safely contained and, therefore, rendered harmless. For example, SCP 1025 is a book entitled ‘The Encyclopaedia of common illnesses’; when someone reads about an illness, they start getting its symptoms. All you have to do to avoid these effects is not open those pages. The same applies to SCP 1004, a search engine on the web that offers extreme pornographic images, such as zoophilia, necrophilia and pedophilia and which induces the user to experience disturbing sexual desires.

The SCP classification of Euclid indicates an intermediate level of danger, which generally consists of anomalies that are capable of acting, thinking or hearing independently and which can, therefore, be unpredictable. For example, SCP 173 is a mysterious and monstrous sculpture that moves at astonishing speed and kills everything in its path by snapping the part of the spine found in the neck but which is as still as a statue if observed by a human eye. SCP 407, also known as the bone hive, is a semitransparent insect of unknown origin located in China. Its sting is painful, but the real danger resides in the construction and reproduction of its habitat, which starts when the insect enters the mouth of a sleeping human and settles in the lungs, where it starts to cause such rapid bone tissue growth that it creates spurs which protrude through the host’s flesh. In the final phase of this transformation, the host’s body curls up into a fetal position, and the new protrusions continue to grow, permanently anchoring the body into a cage.

The most dangerous classification that can be assigned to an SCP object is that of Keter: anomalies that are difficult to contain and which pose a threat not just to human beings but also to the Foundation’s personnel. For example, SCP 734 is a child who is very dangerous because any human tissue that comes into contact with this child rapidly starts to shatter. SCP 993, also known as Bobble the clown, is a video that makes children over the age of 10 lose their senses and teaches homicidal cannibalism and forms of torture to younger children, causing psychotic symptoms.

4. Psychoanalytical Explorations

SCPs, therefore, belong to a narrative, mythological or folkloristic genre from which terrors and anguish, belonging to a denied and removed complexity, emerge like geysers. These narrations can be read as contemporary mythopoeic phenomena. They are, in fact, the result of collaborative practices and collective creations in which emotions and group dynamics affect each other. However, they obviously do not have the power of classical myths because they lack the propulsive force of mourning and the elaboration of the violent emotions that they testify and produce. They are a type of folklore that can be ascribed to the Freudian sphere of the disturbing, which has continued to battle with ‘Evil’ during these times in which narrations have been rendered less violent, even if they are forced to comply with a modernity infested with ghosts. The web seems to facilitate sharing in a fluidity that creates identity recognition spaces but, at the same time, exposes individuals and the community to unpredictable structural disintegration, which can lead to forms of alienation and masking things up. In fact, this genre of narrative universe harks back to sclerotic myths, which have a negative retroactive effect on the communities that identify with them. This creates a potentially dangerous vicious cycle that risks falling to the level of fetish. What I mean is that these narrations are certainly a fuel (which is, fortunately, ecological) that is fundamental to communities; however, they can also be used as oppressive and paralyzing instruments. It does not take long for cohesion and the sense of having a clear path to lead to the construction of a fixed identity to be maintained and preserved by external contamination.

I think that it is significant that the protagonists of the world of SCP are monsters born from hybridizations between the organic and the inorganic, from which dangerous new perceived, cognitive or corporeal functions are derived. They are experiments that seem to bend matter and subvert time.

6 This universe definitely echoes the real world, where, as a result of extraordinary and fast technological progress, daily life is filled with inorganic presences that rapidly go from integrating themselves into boosting to replacing people in many of their functions, making us reconsider the boundaries between the organic and the inorganic, between oneself and others and between the mind and the body.

7 These are presences which, with their power to be appealing, can cause us to catch a glimpse of another ghost, that of the strength of ‘I’, of the ‘return to the inorganic’ which Freud had warned us of and which claims to still be there to embody the continuous and uncertain battle between Eros and Thanatos.

The myth of the artificial man, or, better, of becoming a human imbetween the two extremes of the organic and the inorganic prospers within the kingdoms imbetween fact and fiction. Two different approaches to the artificial man are certainly recognizable and each has its ancestral story. The biological approach starts with Frankenstein or the Modern Prometheus by Mary Shelley (

Shelley [1818] 2016), and the mechanical approach has its origin in Der Sandmann by

Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann (

1815), which has been analyzed by Freud in his essay about uncanniness. Both of these stories have tragic endings: in the first, the creature assembled with human body parts taken from corpses reanimated by electrical energy rebels against its creator, showing free will and a violent disposition. In the second story, the main character is driven to madness and suicide after he discovers that Olimpia, the stunning woman whom he had fallen in love with, is actually an automaton. Literary history appears to be dominated by two epidemics: “the morbidity of Frankenstein, which strikes robots by pushing them to rebellion and the Olimpia syndrome, which instead manifests itself in individual humans, who lose their sense of true and false when they come into contact with robots” (

Giovannoli 1991, p. 9). There are at least two crucial and connected questions that dominate this imagined world: on the one hand, the ways of making artificial men or women, which poses questions of an ontological nature, and on the other hand, the question of human interaction with these creatures created by humans themselves.

However, what interests me is the observation that in SCP stories, the short circuit between man and machine and between the organic and the inorganic carries the problem of the difficulty of discerning between the natural and the artificial, the authenticity of feeling something. These are representations that certainly emerge from our internal worlds and which are easily elaborated. They have an impact on how we imagine the deepest things that we have experienced, and they reactivate fantasies originating from interactions with others, which attain the sexual sphere, the formation of identity and the possibility of living out desire.

The only thing is that in this dystopic world, the cannibalization of the positive potential of otherness seems to be its structuring principle. The entities classified by the Foundation cannot be fought; all that one can do is try to escape. This creates an incurable sense of vulnerability. When faced with creatures without a face, every similarity is lost along with the possibility of a similar, of recognition: otherness becomes disturbing because the “identification contract” within which one can negotiate is impossible

8. In this way, one is constantly exposed to the threat of death, which takes distinct and complementary forms: that of scary agitation, of attraction to something terrible and seductive at the same time, or the form of impotence, of a sense of fragmentation, of being overwhelmed and dominated by something which is looming. “Different but close polarities”. Correale says, “because excitement is never a stranger to feeling dragged around at the mercy of something, and passivity is never deprived of its dark power of fascination” (

Correale 2021, p. 96).

9The triumphant discovery of the young Ernest, Freud’s grandson, as described in Beyond the Pleasure Principle, springs to mind. In this essay, during a period of solitude away from his mother, he discovers how to make his reflection in a mirror disappear (

Freud 1920, p. 201). This act of making oneself disappear is similar to camouflage, a cancellation of the body that leaves the illusion of a uniform background. However, to Ernest, this discovery does not only mean the acquisition of a method of self-defense but also the emergence of subjectivity, like an emerging affirmation against the background of one’s own negative capacity.

In contrast to this, I have had the experience of hearing a young boy who has been my patient for many years because of psychotic behavior and who is trapped in SCP stories tell me that: “Terror obliges me to stay within the confines of my home and to become myself”. This statement, which at first glance appears to be shocking, seems to me to be very rigorous in a metapsychological way. It seems to contradict the spontaneous tendency to think of dehumanization as the loss of identity. What relationship is there between terror and becoming oneself? Maybe the anguish of becoming oneself is an indication of self-hatred; however, it also appears to designate the intolerable state of someone who is forced to be nobody but themself and who, for reasons related to their past, can no longer contain anything else. By ‘contain’ I mean to keep inside the bosom of an other-self dialectic as well as to host. The other has not disappeared, but the psychic differentiation that keeps the dialectic alive has been abolished. In this sense, this boy’s way of being himself is rather a sign of his alienation. The other is not a guest but an invader, just like an SCP. Furthermore, on close analysis, the concept of a guest and of hosting is ambiguous and complex: it puts together contrasting meanings that lead to the idea of a guest, an enemy and a stranger. We are dealing with a notion that simultaneously represents both reciprocity and hostility, which alludes to both solidarity and distance, which requires both friendship and enmity and both otherness and belonging. In Latin, the hostis-hospes semantic link gives hospitality all the ambiguity present in the act of both putting oneself forward and the anguish of this being reciprocated.

10Derrida emphasizes that the enemy has the ability to question the validity of the subject, triggering a process of “reciprocal identification”. Not only does this contrast the subject with the other, but it also forces it to define its own identity through this complex dynamic. The initial question, “Who is my enemy?”, is, therefore, transformed into “Who am I?”, directing the attention away from hostility and towards an ambivalent form of hospitality. No longer able to simply push the enemy away, the subject finds themself welcoming it as a disturbing guest (

Derrida 2020).

Furthermore, according to Derrida, hospitality is not only an aspect of ethics but the very essence of ethics themselves. Welcoming the other, protecting it and responding to its arrival, even if it is eccentric and strange, constitutes the essence of deconstruction, paving the way for the arrival of a destabilizing otherness. This raises questions about being, about justice, about the other and about norms. Hospitality implies a double orientation towards justice and rights, which are often in conflict with each other. The law of absolute hospitality asks that the level of hospitality based on rights be exceeded. This opens up one’s home to the other without asking for reciprocity or knowing the other (

Derrida 2000).

Over the course of my career as a psychotherapist, I have seen many young people seduced by these narrations with psychopathological aspects; young people who, by feeding off of these pervasive images and finding false dimensions of relativity within them, are subjected to forms of social self-exclusion, or of serious dependency, constantly experiencing the sensation of being fragmented and confused as well as excited and seduced. These young people guarantee themselves power and control over the realities that scare them, but their mental life remains unwanted and takes perverse forms.

The psychic dimension of the fictional world of the stories of the SCP Foundation is torn: on the one hand, there is the other, which the reader has turned into an enemy, and on the other hand, the reader is deprived and inconsistent. These are disturbing themes that are specific to adolescence, a phase of life inhabited by violent and undigested emotions, of the internal battle between the alien nature of corporeal changes and of the eruption of sexuality and then of the desired and feared prospect of the exit from family life which involves oscillations between the desire to separate oneself from it and the vertiginous fear of falling, of losing oneself in the experience of something lacking. This is a phase in which young people are attracted to the monstrous, which represents both a pulsating aggression activated by puberty-related transformations and the problem of the desire to and the difficult necessity of living with it. This problematic reality inevitably leads to the conflict and mourning necessary for transformation, which does not only constitute mourning for the serious and very real losses that we suffer but is instead present in every interaction because interactions are constantly lost, repositioned and renewed moment by moment. It is, in fact, mourning itself, which is the instrument that allows us to keep mutual understanding alive.

Nowadays, adolescents have neither classic tales nor rites of passage to accompany them in this transformation. They are more alone, and maybe this is, in fact, where the compulsive need for hyperconnection to virtual communities on the web comes from, as this is the birthing place of new mythologies that act as an interface with the unknown and which help to fill that lack of meaning with explanations which, as bizarre as they can appear, have the goal of taming the disturbing, but only in bodiless digital forms of communication, in which silence means only the ceasing of communication and which produces nothing, leaving the reader in profound solitude (

Byung-Chul Han 2021).

Manipulated and integrated bodies, which are materially or cognitively hybrid in nature, are aspects of contemporary society that make us think about their boundaries and which we find in a natural form in mass culture, where boundaries are uncertain.

11 Of course, in these cases, the metamorphosis of bodies rises to the level of icons; the monstrous also inhabits the hybrid, the ambivalent, the intermediate zone between that which is foreign and that which is familiar (an assumption which disturbs the observer). In a way, the narrative folklore that we are discussing is making itself the responsibility of a heroic and perhaps desperate effort to give all this, including ideas that carry questions that touch bare nerves and something hidden and terrifying that asks for recognition, a voice, a limit and a new meaning. But what structure or sense can it give itself in a sphere characterized by the formless?

A part of the search for a form is the hastening of the re-emergence of all the aspects of existence that have been removed, starting from one’s own body and physicality, fragility and weakness, desires and limits, functions and needs. In fact, psychoanalysis has shown that even the origin of oneself, the ‘I’ follows the trajectory that leads from the formless to forms: according to Freud, “The ‘I’ is above all a corporeal entity” (

Freud 1923, p. 488). He then goes on to state that it is the projection of a surface, which is an image with a shape. A part of putting the body into discussion is about asking oneself about the imaginary status of the subject and of the relationships it has with its self-image and with how it sees others.

Just like in other types of contemporary horror folklore, in SCP narrations, one can see anxiety transferred from the psychic to the somatic level. This inevitably reminds us of original forms of contact, in which rather than the nature of the other being grasped, the nature of the impact one has with oneself and with the world is grasped. Meanwhile, the coming together of bodies prevails over that of subjects, with cannibalistic and destructive fantasies, which Melanie Klein’s (

Klein 1948) clinical and theoretical thought describes in detail.

The strange thing about the descriptions of SCPs is that despite how much effort has been put into making them interesting and captivating, they never symbolize a possible other thing. SCPs are monstrosities that only represent the fear of incompleteness and distortion. In psychoanalytical terms, it could be said that they are, in fact, split objects that have a life of their own but that are not susceptible to connections or branches. This means that when there is a breakdown in one’s fundamental relationship with the other (or with oneself), one is faced with scary anxieties about getting lost. Normal realities become mysterious and bizarre, and one’s thoughts take on an intensely visionary nature that is not down to earth, so to speak, but which has instead fallen from the sky and which, at the very least, comes from an unknown world. It is as if there were a collapse of the spatial-temporal coordinates, which is immediately filled in because both the solitude and the sense of the cancellation of subjectivity that it creates is intolerable.

SCP wiki is, therefore, an extremely rich sampler of objects in which a ‘good form’, in other words, the ability to contain and transform fear, is missing. On the contrary, there is a neurosis of fear, an imposing influx of latent, overexcited and difficult-to-contain aggressivity produced and disposed of in a “single use stories” fashion, which only allows infinite accumulation. In this paranoid and nevrotic scenario, the other cannot contribute to the development of thought. Instead, one can only excite the transitory pleasure of a prescribed sexuality, which is unable to replace the pleasure of openmindedness towards objects and availability in their regards. Paranoia induces the necessity of maintaining a strict order. It is an inflexible sequentiality of rituals that immobilizes all evolving processes. Of course, there is a lived experience of impotence in the face of being overwhelmed and dominated by something imminent. This comes from the risk of coming into contact with mysteriously alien-like bodies, which are vehicles of contagion and which induce a very real paranoia towards groups. For the subject who feels fragmented, the prospect of a meeting becomes radically incompatible. This forces them to make the dramatic choice between their own existence and that of the other. A subject who seems to have lost faith in the world as a place where peaceful coexistence is possible, therefore, seems to emerge. These subjects live with the constant fear of a possible storm, which is perhaps subject to brief pauses but which is, in some way or another, always ready to come back. Faced with the risk of the collapse of presence (of being present and of feeling alive in time and space), this subject draws on a dark and powerful sense of vitality by imposing unconditional vigilance on themselves: a constant state of alert. We are faced with systemic rigidity built on structural uncertainty: the subject demands that a phantom-like hypervigilant organization guarantees guardianship, which their “immune system” cannot. This organization then suffocates the desire of the other and prevents the reopening of any negotiation, which is a vital force for potential transformations.

However, it is not so much the problem of the difficulty of the external otherness that characterizes subjects that inhabit the world of SCPs; this is only the symptom. The real problem they face is the difficulty they experience living with and deciphering their own emotions and understanding the otherness that moves inside them like magma. Moreover, they appear to grasp some truths in the depths of their souls, but they are incapable of admitting this to themselves, of creating an appropriate location for glances and questions or of any intimacy where forms change, and so do points of observation.

12 Instead, the subjects have a tendency to simplify and to remove, and in doing so, they invest in the most rigid part. They help themselves by constructing a grander and idealized form of themselves, an enemy to be fought in order to compensate for their intimate state of uncertainty and vulnerability.

Healthy mental development does not depend on historical, scientific or philosophical truth but on emotional truth. It does not depend on what has happened to us but on how we have been affected by what has happened to us. We are talking about subjective truth, which does not coincide with external truth. Hanna Segal (

Segal 1984) states that truth is not a fact but a process. Furthermore, what counts the most is that emotional truth is not immutable and identical to itself once grabbed. Instead, it modifies itself continuously with time.

In a world of continuous migration crises, of widespread attitudes based on exclusionary logic and of walls and barriers that separate and divide peoples, an aversion towards the different seems to be a pervasive trait of contemporary society. These phenomena, based on a resurgence of hatred, push us both towards a radical interrogation of the phenomenology of hostility and of its diverse declensions and towards an equally radical re-thinking of the concept of hospitality.

It was as if the SCP Foundation had installed itself into our factual reality, and of course, some bizarre narrations have developed. Narrations that have hints of conspirative paranoia and would carry the risk of creating more social and cultural fractures if they were leaked in contemptuous ways.

Of course, it is important to take unbiased studies into account. However, it is also important to take into account the human experience (opinions, behaviors and the reactions of both individuals and groups). In order to gain a profound understanding of this, we should not only ask ourselves what is really happening, but we should also try to understand the narrations, beliefs and behaviors that are circulating and the motivations for these.

Let us analyze two of the main different narrative accounts: that of the media, which, despite the many true and factual elements, also leans towards the sensational at the cost of objectivity, and that of the opinions of ordinary people, which are sometimes considered irrelevant and unappreciated but which spread a lot on social media. These narrations paint a problematic and confused world, and maybe it is not enough to say that these define us. These

are us: body and soul, flesh and idea, technique and ethics: a connection that goes beyond the simple metaphor. Understanding the differences will lead to better communication and to us being better equipped to face the divisive and sometimes racist or xenophobic narratives that arise from migration crises.

Goldstein (

2004, p. 56) observes that Education on the topic of culturally sensitive health has to adapt itself to the beliefs, attitudes and practices that exist within a community rather than expecting that the community will change to adapt itself to the educational program. In line with this idea, the Freudian theory on the disturbing provides key interpretations: this can be defined as a theory of trauma that is more powerful and explanatory than any form of metapsychology (

Freud 1919). As Conrotto writes, “by ‘trauma’ one means the lack of or break down of meaning; however, whereas trauma and representation are opposites, traumatic theory is the representation of the lack of representation” (

Conrotto 2000, p. 200). Therefore, as Moroni writes in the disturbing, “there is an attempt on one’s own behalf, on behalf of the I, to create a formation of compromise, in order to give oneself a reason, to tolerate the anxiety which invades its boundaries in order to attempt to restabilize one’s own narcissistic homeostasis”, which is one’s own drive to exist (

Moroni 2019, p. 96). It is a big representative effort with which the subject struggles to master a situation in which there is a dramatic loss of control. This provides a temporary narrative organization deprived of any representation with a pathway that allows it not to be overwhelmed by unknown and undigested emotions.

If myths, therefore, are the dreams of humanity and can be excellent vehicles with which to cross the landmine-filled field of emotions without exploding, then let us consider dreams, both in Freudian terms and in Bionian terms related to dreamlike thought. The SCP narrations which I have attempted to analyze are anything but useful to psychic development. Instead, they appear to encourage the excitement of the perverse/polymorphic dimension through an idealization of certain forms of confusion (good–evil, true–false, etc.). Through these filters, the sense of limitation is dispersed and the boundaries between the psychic I and the corporeal I become imperceptible. Symbolization and sublimation activities also fade away, causing direct damage to the work of the preconscious mind, in other words, the ability to associate and to think.

13Rather than using a “transformative object”, which, as Moroni says, helps to transform trauma into creativity and development, these narrations use “objects which agitate”, with no transformative work, in an ever increasingly artificial way. There is something here that reminds us of hysterical phenomena: original trauma and the way it is transformed into a sort of spectacle in the body, the immersion in the hypertrophy of details that become hallucinatory, elements that seem to effectively represent the contemporary hysteria of powerful, perceptive and hypnotizing data to the virtual community which does not ask itself any questions and which is satisfied with the deadly pleasure of dancing joyously on the edge of a precipice.

In conclusion, the analysis of SCP narrations offers a profound reflection on the evolution of humanity in an era of technological acceleration and identity challenges. By always remaining ambiguous, these stories fuel persecution, fear, a permanent state of alert without rules and a flood of primordial emotions, which lead to the questioning of the boundaries between the organic and the inorganic, a problem which the common sense of our era seems to warn against with a greater sense of urgency.

Digital horror narrations offer a perspective for the exploration of the intricate connections between the psychic evolution of the subject, collective imagination and the complex theme of the fear of the other.

The necessity of bringing about a humanity capable of navigating the subtle line between nature and technology emerges clearly. This is in harmony with the vision of the “Chthulucene” in Donna

Haraway (

2019), which embraces the idea of an ecology that transcends the boundary of the antropos in order to consider the entire planet.

The analysis of SCP narrations highlights the crucial importance of recognizing the existence of the binding unconscious and of interacting with it, opening the door to new perspectives of comprehension and meaning.

In contemporary society, in which traditional social norms are rapidly mutating, and new possibilities are forming, the careful examination of the link between the body and technology, which has reached unprecedented levels of proximity and interdependence, becomes essential. This phenomenon fades the traditional categorical axes of difference, which are essential for the regulation of impulses. This complicates the boundaries between the normal and the abnormal and the real and the virtual, therefore opening up the possibility for the exploration of what is happening in this liminal phase. Although such a process might not yet be fully integrated into a shared social meaning, it paves the way for future evolutions.

In this scenario, Freud’s words on sublimation, narration and myths as instruments to emancipate oneself from the mentality and the uncritically shared ideals of the I (

Freud 1921) maintain a significant relevance.

Resisting the temptations of nostalgia and technological utopias helps us to maintain a balanced position, which helps us to fully understand the impact of technological changes on the development and the functioning of the mind.

In order to embrace change and make the most of the opportunities that present themselves in this fascinating world that is evolving, what we need is a severe and serene glance like that of Athena, who was blind and deaf but guided by her nose and appeased by her surroundings, and like that of Hera whose purpose of being and life reward was the defense of the living space of the herd.