Abstract

Transhistorical accounts of fanfiction often refer to the Brontës’ juvenilia, but such references are largely cursory even as they make a claim about the siblings’ Angria and Gondal writings that needs more careful consideration. This essay offers a more thorough examination of what it means to claim “the Brontës wrote fanfic”, analyzing their family- and site-specific mode of creative production and consumption in relation both to established definitions of contemporary fanfiction and to their own sources and environment. Archival research has enabled me to situate some of the Brontës’ earliest texts in their original tiny, hand-produced format alongside the print periodicals and physical books that the young authors read and transformed. I analyze how the siblings’ books mimic the multiplicity and flexibility of authorship modeled in their local newspaper and how their drawing, marginalia, and corrections accentuate the interactive nature of the printed book. Viewing the Brontë siblings as a family fandom enthusiastically devoted to the creation and appreciation of transformative works helps make visible a model of authorship they share with contemporary fanfiction: authorship not just as collaboration but as play and exchange among diverse materials, sources, activities, media, writers, and readers. Then, as now, this mode exists simultaneously with commercial authorship but is distinct from it, as the siblings recognized, altering their plots, practice, and presentation for their novels.

Keywords:

fanfiction; juvenilia; The Brontës; Angria; Gondal; authorship; interactive media; print culture; hand-made books 1. Introduction

When the Brontë children took up toy soldiers, named them after famous military figures, and began acting out and then writing up their adventures, is this fanfiction? Can we call texts fanfiction that were written in the 1830s, long before the term “fan” let alone “fanfiction” or “fanfic” had been invented and before many of the media environments and technologies basic to contemporary fanfiction existed? According to Andy Sawyer, historian of science fiction culture and curator of the 2011 British Library exhibition “It’s Science Fiction, but Not as You Know It”, the answer is yes:

The Brontës are well known authors with no apparent association with science fiction but their tiny manuscript books, held at the British Library, are one of the first examples of fan fiction, using favourite characters and settings in the same way as science fiction and fantasy fans now play in the detailed imaginary ‘universes’ of Star Trek or Harry Potter.(British Library 2011)

Sawyer is neither the first nor the last to make this claim. The Brontë juvenilia—stories that future novelists Charlotte, Emily, Anne, and their brother Branwell wrote over many years, known variously as the Glass Town, Angria, or Gondal sagas—has often been cited in popular accounts of fanfiction’s history, especially as internet fanfiction gained in popularity and notoriety in the 2000s and 2010s. A 2009 Wichita Eagle article entitled “what my son and Charlotte Brontë have in common”, for example, gave fanfiction as the answer to its title question (Brontë Blog 2009). Defenses of fanfiction became even more common in the wake of Twilight-fanfiction-turned-bestseller Fifty Shades of Grey. A 2013 post to the Quirk Books blog proclaimed that “Charlotte Brontë did a lot of things typical for teenagers: made ‘zines, wrote fan fiction, and had a Gothic phase” (Thornfield 2013); on a Seattle radio podcast in 2014, Slate editor Dan Kois mentioned the Brontës along with Superman and Spiderman crossover comics and Virgil’s Aneid in the course of defining and defending fanfiction in the broadest transhistorical terms (Nicks and Scher 2014). Contributing to that trend, my own earlier work referred in passing to the Brontë juvenilia in a section called ”A Prehistory of Fanfiction” and captioned an image of one of their hand-made books as “Duke of Wellington ‘fanfiction’” to illustrate “The Look of Fanfiction 1800” (Jamison 2013).

Such gestures to the Brontës’ early work as fanfiction, however, rarely if ever examine the actual claim being made or consider its implications. This is understandable in popular formats such as blogs, podcasts, or journalistic articles that make no claims to scholarship, but it is also true of my book Fic, which readers approach with different expectations. In keeping with other examples of my recent work, then, this essay addresses claims made briefly in a book written for a popular audience that has nonetheless also functioned as an academic text almost since its publication. Given that the Brontës’ ubiquity on lists of historical fanfiction writers may be partly my responsibility, it is arguably also my responsibility to explain in more scholarly terms what I mean by that claim and to what extent I stand by it. Thus, in this essay, I explain what understanding the Brontë family as a fandom and its culture of collaborative authorship and interactive media as fanfiction can teach us about fanfiction, literary history, and the Brontës themselves.

To be clear, you would not need to be a fan studies or literature scholar to understand why these texts get called fanfiction. Like most fanfiction, the Angria sagas are fiction without being novels (though, like contemporary fanfiction, they do include some more stand-alone, novel-like stories). The body of work by the young(ish) Brontës is immense, heterogeneous, and encompasses multiple contradictory emphases and preferences in ways that can seem incoherent to readers expecting traditionally published and polished novels, but which would feel familiar to contemporary fanfic readers. On the other hand, the invented yet colonized African country of Angria, with its arcane political systems, intrigues, and wars, is sure to feel unfamiliar to anyone not well-versed in early nineteenth-century British parliamentary and colonial politics—that is to say, to most people currently alive. But then, like any fanfic text that delves into the politics of a complex world for an audience of other devotees, the Brontës wrote for other “fans” of period political and military campaigns (that is, for each other). So even Angria’s sometimes off-putting complexity would feel familiar to any fanfiction reader who has stumbled into a half-a-million-word Lord of the Rings fic, for example, without ever having read a word about Middle Earth. By the same token, a seasoned fanfic reader of today would recognize key Angrian plot and character elements as well as the intra-fandom conflicts about them. For example, the Angria stories prominently feature coercive and clearly sexual affairs enmeshed in intricate worlds, wars, political systems, family structures, and even periodical literature. And, just as in fanfiction fandoms today, tensions often arose among the Brontë siblings about where best to place narrative emphasis among these diverse elements—conflicts analogous to though perhaps less heated than the acrimonious arguments that contemporary fandom refers to as both “wars” and “discourse”. To further complicate matters, each Brontë sibling wrote under multiple pseudonyms and personae who would also argue amongst themselves using stories and plot twists as satirical weapons. Such self-aware, winking devices were once claimed by literary scholars for postmodern metafiction but in fact are frequently employed in the 1820s’ and 1830s’ periodical press the Brontë siblings were obsessed with. Such devices also often feature in contemporary fanfiction, as in “Fandom AU” (alternate universe) stories in which characters are written as fanfiction writers or artists themselves, often in their own fandom (meta-hilarity ensues). Indeed, one of the most “ficcish” elements of the Brontë writings is the centrality of play, from their earliest accounts of it well into adulthood, when Anne and Emily could spend days roleplaying their Gondal characters to help pass their time traveling (Moon 2020).

Such resonances and commonalities may need no academic training to identify, but they do require some familiarity with fanfiction as well as with these early Brontë texts. And, despite the ubiquity of the Brontë juvenilia in defenses of fanfiction, these audiences do not always overlap (although, as I discuss in my conclusion, they do overlap more than many might think). Because fan studies and Brontë studies do not always overlap either, some sections of this essay will seem basic to one population or the other, so I have tried to label clearly to help readers find what they need. First, I give an overview of fan studies concerns about literary historical approaches to fanfiction, explaining why many scholars reject calling historical, literary, or commercially published texts fanfiction at all. Next, partly in response to some of these critiques, I take Francesca Coppa’s popular and widely-disseminated definition of fanfiction and explain point by point the ways in which the Brontë siblings’ early work qualifies as fanfiction by these well-known criteria. Sections that follow delve more deeply into the Brontë texts and contexts. Using archival material, I describe the workings of “the Brontë family fandom” in more detail, focusing especially on the texts’ and siblings’ relationships to literary, media, and material sources, to period publishing practices, and to each other. I explain what these relationships tell us about the famous siblings’ understanding of authorship and how it changed and diverged. I consider what Charlotte, Emily, and Anne’s later reception as authors can tell us about how literary historical trends and commercial publishing practices have shaped, and arguably deformed, our understanding of their work and Victorian authorship more broadly. By way of conclusion, I acknowledge a different sense of the phrase “Brontë family fandom” in the way my scholarly practice has overlapped with my own conflicted love of these writers—and close with an instance of contemporary fanfiction’s active engagement with Angria and Gondal through beloved fanfiction writer AJ Hall’s multivolume, multisource Queen of Gondal saga—which I also hereby recommend to any readers unfamiliar with contemporary fanfiction as both reference and initiation.

2. Fan Studies and Literary Studies

By training, I am a Victorianist and a comparatist, so comparing nineteenth-century texts to contemporary fanfiction is probably second nature to me. For better and worse, though, equally second nature is a somewhat polemical irony that led me to write things like “Shakespeare wrote fic for the Ur-Hamlet” in what turned out to be an influential book, and only several pages later to explain this was only partly true for a variety of literary historical reasons that turned out to be much less quotable. As many critics since have more earnestly and with much more scholarly precision explained, to say Shakespeare (for example) wrote fanfiction is not accurate given (for example) historically divergent conventions of authorship and conditions of literacy and material production. To such valid critiques, my first response has been, “yes, of course” and my second an essay about the term “fanfiction” in a transhistorical and literary theoretical context and why I still think there’s a value in its “big tent” usage (Jamison 2018). I am not going to reproduce those arguments here, although much of what I say there would apply to the goings-on at Haworth parsonage.

I will say the following, however, about the broader argument that animates much of my ongoing work: Approaching fanfiction as a literary practice on a historical and procedural continuum with other literary undertakings should challenge our understanding of central categories—fanfiction, literature, media, authorship—without erasing them. At the same time, this mutual reinvestigation stands to illuminate the impacts of material, economic, and political influences on literary production whether amateur or commercial, all while restoring our active understanding of the diversity of authorship models that have coexisted in earlier eras as they do today. Considering literary history from the perspective of fanfiction highlights collaborative, heterogeneous, interactive, and derivative elements of authorship that the author-text taxonomies still dominant in publishing and scholarly discourses overlook or de-emphasize. Similarly, understanding certain fanfiction practices as longstanding elements of literary life potentially depathologizes a still disparaged and artificially excluded cultural form—and not just because special people called authors wrote fanfic. Rather, the fannish work they left, work that has been preserved in large part because its writers were later recognized as authors, shows how the underlying practices and principles of what we now call fanfiction are, in historically and culturally distinct and contingent iterations, deeply ingrained in the history of reading and writing. I offer the present essay as an example, hopefully, of what might be gained in bridging the fan studies and literary studies divide to examine specific objects from both perspectives. However, since I considered critiques of this practice important enough to inspire a whole essay, I do not want to give them short shrift here and so will engage with several that came out after I would completed my work on that piece (Jamison 2018).

In understanding why hackles sometimes get raised when texts produced outside of contemporary fandom get called “fanfiction”, it’s important to understand not only that the definition of fanfiction is contentious, but that outside of fandom circles, the term is still most often used as a pejorative. That is, while referring to classic texts such as The Inferno and Paradise Lost as fanfiction is now commonplace, denigrating some cultural artifact or trend by calling it fanfiction remains more so. Even when there is clearly no derogatory intent, and even when the intent is defensive or laudatory, some fan studies scholars and fans argue against reading contemporary fan practice back into history or out into commercially published retellings or adaptations. If “it’s all fanfiction”, the designation collapses meaningful distinctions and elides historical conditions involving (for example) media, technology, and conceptions of intellectual property. Nor is it only the use of “fanfiction” in literary contexts that draws objections. Judith Fathallah, reviewing literary approaches to fanfiction in a whirlwind tour of disdain, takes issue with the rhetoric of literature per se and what she terms the “Modernist trap” of seeing texts as self-sufficient or divorced from social context (Fathallah 2017). To be clear, it has been a long time since Brooks and Warren’s Understanding Poetry (Brooks and Warren 1938) and its strictures to read only “the text itself” held sway in literary studies scholarship, which has largely centered the social and historical for the past several decades at least. Similarly, “the author” has been soundly critiqued since structuralist Roland Barthes (“The Death of the Author”) and semiotician Michel Foucault (“What is an Author?”) published their influential essays in the 1960s. Jack Stillinger’s 1991 Multiple Authorship and the Myth of Solitary Genius emphasized the multiple roles involved in textual creation and production, and since then, authorship studies has expanded to consider book history, material culture, and sociology as well as a far more culturally diverse frame of reference (Stillinger 1991). Despite all of this, however, the New Critical assumptions about textual autonomy and authorship that draw Fathallah’s ire continue to be influential, especially in the classroom and the profession’s organizational and indexical norms. Furthermore, Brooks and Warren were so dismissive of women writers and (relatedly) anything they understood as “sentiment” that it is not difficult to imagine what they would have thought about fanfiction. Given the continued latent influence of these outmoded ways of thinking, it’s easy to see how reading literature from a fan studies perspective or vice versa can seem a condescending gesture of justification or legitimation, as if fanfiction is not itself sufficiently worthy of study on its own terms.

The process of reading fanfiction back into literary history also raises methodological concerns. As Cait Coker explains, while early studies of fanfiction tended to rely on ethnothgraphy rather than textual analysis, literary historical approaches to fan fiction are increasing but continue to face disciplinary challenges arising from “problems of definition (what ‘is’ fan fiction?) and genre (literature versus media)” and “prejudices of discipline arising from the conservative literary canon writ broadly and literary theory more beholden to ‘the author’ than to the circulation of the text” (Coker 2021) Similarly, while giving a “gentle push” directed at “English as a profession” to “embrace fandom as a legitimate area of inquiry”, Alexandra Edwards recognizes the many pitfalls of such an undertaking, also citing “the tendency of literary scholarship to privilege the author as a singular figure”. This continued centrality of the author (despite half a century of interventions) “obscures the varied ways that texts can be composed across networks” while “anachronisms, muddy timelines, and claims to historical specificity, and paternalistic attitudes toward women readers” also raise concerns. Edwards cautions specifically against “the approach to fandom that sees it as a prop in the analysis of literary fame” and the anachronistic use of words such as ‘fan’ and ‘fandom’ in the analysis of early works (Edwards 2018). In outlining how scholars might better talk about “premodern fanfiction” (“premodern” in an academic context means roughly pre-1600), Anna Wilson insists that “we must first answer the question, ‘What are the essential qualities of fan fiction, and which are transposable beyond its twentieth- and twenty-first century cultural contexts and can be applied to the literatures of other times and places?’” (Wilson 2021) Wilson too wants to get beyond what I call the “Virgil wrote fanfic” gesture (she calls it a cliché) to examine what such a proposition means and “what analyses it might generate”, which, albeit for a different period, is also my goal here. Before that happens though, Wilson insists, fanfiction must be defined.

Does it? “Poetry” also has multiple contradictory definitions, but not every essay about a poem sees the need to define poetry as its first order of business. Does every discussion of fanfiction really need to make this critical gesture, by this point so ubiquitous it could itself be called a cliché? Thus far, apparently, yes. Fan studies is a relatively recent and interdisciplinary field that draws readers unfamiliar with many of its terms and objects of study. I have Victorianist colleagues who have never heard of fanfiction, much less read any. Then, too, like much in fandom, the definition of “fanfiction” (also known as “fanfic” or just “fic”) is contentious. In common usage, as I’ve argued, the term emphasizes very different aspects of a phenomenon it nonetheless successfully designates (Jamison 2018). The definition Wilson offers is novel, precise and yet flexible enough to acknowledge this variability and contention within the term. Wilson proposes three axes corresponding to different understandings of fanfiction that would make sense for premodern texts: “poaching” (orientation towards textual authority, “poached” from Henry Jenkins); “transformation” (orientation towards the formal or literary); and “affect” (orientation towards, well, affect): that is, prioritizing the relationship of a given text to source, form, or feeling. I am echoing linguist Roman Jakobson’s “orientation toward” phraseology from his influential “Linguistics and Poetics” (Jakobson 1960) in part because Wilson’s “axes” recall the watershed in literary theory that Jakobson’s metaphorical and metonymic “axes” in his 1956 paper “Two Aspects of Language” (Jakobson [1956] 2010) turned out to be. Indeed, Wilson’s essay exhibits a near Structuralist insistence on consistent methodology, all while valorizing an entire field of inquiry, affect studies, that had little place in the approaches of this earlier generation of critics. Although Jakobson does identify an emotive function of language (“orientation toward the speaker”), it is the “orientation toward the message” as language and form rather than meaning or expression that he designates as “poetic” (1960). Wilson thus evokes a rigorously linguistic approach to literary studies and applies its rhetoric to include the affective elements it largely sidelined. While Wilson rejects the “Virgil wrote fanfic” gambit, she does understand its appeal: “Suggesting that august canonical authors like Dante wrote fan fiction may serve to puncture reverence for a literary canon that still dominates high school and university curricula; it could equally make an argument for fan fiction’s place in that canon”. Wilson’s subtle evocation of Structuralism accomplishes something similar with relation to a still-influential critical canon. Old notions about the “squishiness” of feeling as a category of value and analysis persist despite the recent prominence of affect studies. In a later section, I discuss how the “enthusiasm” that characterized the Brontës’ early work led it to be passed over when other of Charlotte’s papers were being prepared for publication. When Wilson places affect on an equal “axis” with literary form, she also demonstrates how “fanfiction” approaches to literary studies can provide frameworks for including elements of literature that earlier critical methodologies excluded. To my mind, bridging the gap between literary history and fan studies through more focused and sustained analyses of, for example, fanfiction and Virgil (Basu 2016) fanfiction and Sydney (Simonova 2012), and fanfiction and Richardson (Havens 2019) demonstrate the value Wilson promises. The complexities and pitfalls of this rapprochement are worth navigating not least because failure to do so also comes with costs. Again, despite the historical limitations of the term “fanfiction”, failure to consider “fanficcish” elements of historical writing practices—such as the Brontë siblings imitating their favorite magazines, collectively developing favorite heroes into increasingly independent characters, infusing ongoing serialized stories with contemporary events—makes fanfiction seem weirder and literature more isolated, underscoring misleading prejudices about both.

3. The 5 + 1 of the Brontës’ Angria Fanfic (or, Five Ways the Brontë Juvenilia Is Like Fanfiction and One Way It’s Like a Different Kind of Fanfiction)

In this section, I purposefully make use of a popular, generalist definition of fanfiction—not one I’ve tailored to my topic here—to explain why I think the term is appropriate to the Angria sagas despite the anachronism. In The Fanfiction Reader, Francesca Coppa—who gestures towards Chaucer in the structure of her anthology but is largely concerned with contemporary texts—defines fanfiction by means of five criteria, plus one, playfully evoking the “5 + 1” fanfic genre, as she explains (Coppa 2017). These criteria are more or less (in the sense of some more, and some less) widely agreed upon, and the Brontë juvenilia meet them in a way that seems almost systematic.

One: “fanfiction is fiction created outside of a literary marketplace” (Coppa 2017) Check. The Brontës not only authored but hand-produced these texts for and with each other in ways that rendered them almost inaccessible to anyone else. As part of this first criterion, Coppa quotes fan studies pioneer Camille Bacon-Smith as stipulating that fanfiction was created for “’an insider audience trained to share in [fanfiction’s] conventions” and generally stresses that work created outside the marketplace is free to do things that commercial work cannot. Charlotte internalized this principle so intensely she first abandoned and then repudiated her juvenilia entirely on her journey to commercial success.

Two: “fanfiction is work that rewrites or transforms other stories”. Check, and the Brontës transformed not just stories by other people, but stories by each other (as contemporary fanfic also does, often by way of a remix challenge), and even by their own pseudonyms. Also, in working with their sources, it was not just stories that they were transforming, it was form and format (and sometimes, the physical source itself).

Three: “fanfiction is fiction that rewrites and transforms stories currently owned by others”. Check. There’s certainly a great deal of Byron and Scott in Angria, and probably Wordsworth in Gondal, as well as any number of books in the family library. The Brontës also go in a different direction with their sources, however, one that has only grown more prevalent in contemporary fandom: Real Person Fanfiction (RPF). The young Brontës base characters and their exploits on media accounts of the military celebrities their entire household followed with interest—the tin soldiers’ conquest and subsequent colonization of Africa is thought to have been inspired by stories in Blackwood’s Magazine, the source for so much of the juvenilia (Alexander 1994).

Four: “fanfiction is fiction written within and to the standards of a particular fannish community”. Check. Howarth provides a community of like-minded writers and readers within which fan texts—the chronicles of Angria and Gondal—are created and shared. It continues to provide this community even when individual members are removed from the parsonage itself, as when the children attend school, or later teach it.

Five: “fanfiction is speculative about character rather than about the world”. For this one, I would have to say, it depends on the fanfiction. The Brontës were speculative about both—but in the case of Angria, Charlotte, at least, is increasingly absorbed by character and romance, somewhat to her brother Branwell’s distaste.

Plus One: Coppa’s “+1” criterion, that “fanfiction is made for free, but not ‘for nothing,’” highlights the relationship between amateur and commercial authorship that I discuss in a later section. My own ”+1” here, however, is more caveat to Coppa’s fifth criterion above and, by extension, a caveat about fan studies. In its approach to fanfiction, fan studies overwhelmingly centers Archive of Our Own (AO3), the fan-designed, fan-run, non-profit archive that Coppa co-founded. This also tends to be true of my own recent scholarship and teaching.: like many of my colleagues, I find AO3’s policies to be more transparent and its filtering and search features easier to use and teach as compared with other fanfiction sites and archives. However, as my students remind me every time I teach my fanfiction course, AO3 is not coextensive with fanfiction more broadly. Whole fanfiction communities and methodologies of writing that are primarily interested in things like plot, world, and, frankly, battles, may not always end up on Archive of Our Own because, in the opinion of some fanfic writers and readers with these interests, AO3 is “all shipping [romance] and sex”. In some circles, the older archive Fanfiction.net is understood to be more hospitable to plot- and action-driven fanfic, whereas the site spacebattles.com tends to feature the kind of works its name suggests, as do many other smaller fandom-specific sites and messageboards. There’s a perception, at least, that this plot/world/battle v. character/romance split is gendered, despite the many male-skewing fanfic authors who claim affective or therapeutic motivations for their writing and focus on character and/or romance or the many female-skewing authors who focus on world and plot. I bring this perceived split up here because a similar conflict arises in the Brontë family fandom. While the siblings all engaged enthusiastically in worldbuilding and political intrigue, Branwell was more taken with detailing battles, while Charlotte tended to use war more as a backdrop for character and romance. Not all fandom fractures follow this paradigm, of course: Emily and Anne eventually split off to create their own world which seemed more realistic to them and more mundane to their siblings.

With this partial caveat, Coppa’s criteria for what constitutes fanfiction apply remarkably well across the many years and volumes of fiction set in the Glass Town, Angrian and, as far as we know, Gondal worlds (the Gondal prose texts were lost, though poems and references in journals remain). The application of these criteria also makes visible a key difference between considering the Brontës’ amateur transformative works as fanfic and, say, works by Dante or Chaucer: the literary and media environment of the 1820s and 30s is much closer to the environment of the 1960s, when “fanfiction” (or “fan fiction”) begins to be used in its present meaning, than to the 1310s or 1380s. In order for Coppa’s first criterion to apply, for example, there needs to be a literary marketplace to be outside of, with the literacy rates and means of production and distribution that requires. This relative historical closeness to our own time would be less necessary for other criteria or other well-known definitions, such as Kristina Busse and Karen Hellekson’s “extensive, multi-authored works in process” (Busse 2017, p. 122). While all uses of the term “fan fiction” to refer to “work that rewrites or transforms other stories” written before the 1960s might be anachronistic, some are more anachronistic than others.

4. Angria and Gondal: The Sagas and Their Sources

4.1. The Brontës “Come to Fandom”

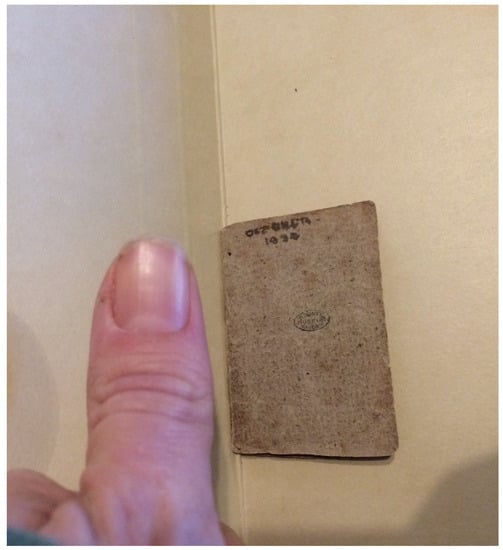

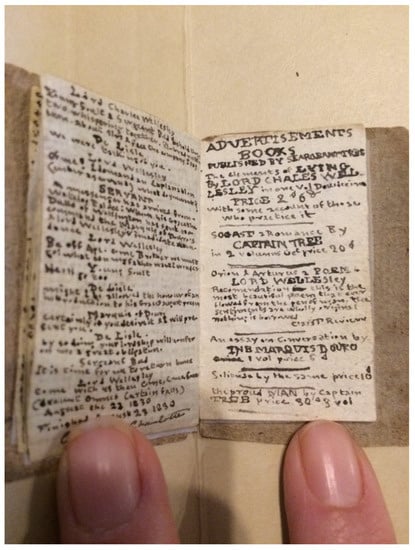

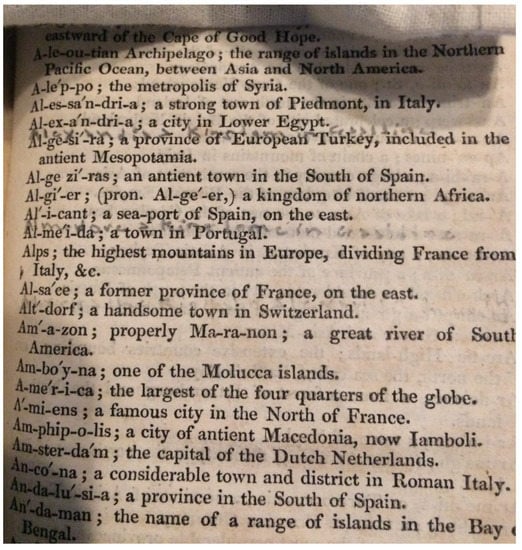

A ubiquitous element of fan studies and fandom narratives alike is the “coming to fandom” or “coming to fanfic” story, a pivotal moment in countless formal ethnographic studies and fan-authored critical writings known as “meta”. All the fan writers I have invited to contribute essays or lectures in any forum over the years have wanted to include their own story of how they got their start in fanfiction. A strikingly similar impulse guides Charlotte Brontë’s earliest account of her and her siblings’ creative work. Charlotte’s second earliest extant writing, dated 12 March 1829, introduces what she identifies as their major works: “our plays were established: Young Men, June 1826; Our Fellows, July 1827; The Islanders, December 1827. These are our major plays which are not secret”. (Alexander and The Brontës 2010, p. 3) Although Charlotte at first suggests “their nature I need not write on paper, because I think I shall always remember them”, she immediately goes on to describe them in more detail. The beginning of these “plays” is famously introduced as a momentous occasion: “Papa bought Branwell some soldiers at Leeds. When Papa came home it was night and we were in bed, so next morning Branwell came to our door with a box of soldiers. Emily and I jumped out of bed and I snatched up one and exclaimed, ‘This is the Duke of Wellington! It shall be mine!’” (p. 3). Branwell also gives an origin story a year later, in 1830, that differs in some respects as to the arrival of the various soldiers. But whenever their arrival, since that time, the Duke of Wellington and his various offspring and colleagues, some real and some more purely fictitious, would go on to populate the children’s collectively imagined, enacted, and chronicled adventures, their islands, and eventually their cities and countries. The toy soldiers, furthermore, would double as initial audience, which determined the production scale (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The author’s thumb next to an early edition of the Young Men’s Magazine. Images are the author’s photos taken with kind permission from The Bronte except as otherwise indicated.

Contemporary fanfiction is organized primarily by source, and this inspiration by a particular text or source (Star Trek or Sherlock Holmes, for example) tends to be what draws people to write and read fanfiction. The sentence “Charlotte wrote Duke of Wellington fanfic” indicates the Duke of Wellington as a primary inspiration for Charlotte, and in contemporary fandom, it would identify the story for readers who share that interest. The stories might also be called Military RPF (Real Person Fanfic) or, in keeping with this origin story, Toy Soldier fanfic, or Military RPF X Toy Soldier crossover fic, etc. In contemporary fandom, the source has largely supplanted the author’s primary indexical role. However, just as the primacy of the author has oversimplified the many forces at play in textual production, the tendency to think of fanfic as being based only on one or two primary sources oversimplifies a much more complex endeavor (an oversimplification the archive AO3’s equally complex tagging system seeks to address). Just as early Sherlock Holmes stories sometimes mimicked elements of The Strand Magazine, or early Star Trek fandom took the form of encyclopedia entries, or today stories are told in the form of social media exchanges or even academic articles, the Brontës’ rich media environment had an influence on their sagas equal or greater to that of the primary sources the famous journal entry initially claimed.

4.2. The Haworth Media Environment: Newspapers and Periodicals

If the Brontë juvenilia are to be considered as fan texts, fan writers will counsel that fan texts are best understood in the context of the source material. They are not for us (to the extent that we are non-fans); they are intended for the community that knows and understands their sources and should be judged and understood within that framework. However, despite clearly writing only for themselves (as, again, their painstakingly produced but near-illegible production format suggests), this small fandom was nonetheless eager to explain their contexts, histories, and procedures. In same early manuscript, Charlotte Brontë lays out a handy primer, minutely detailing the circumstances, media environment, and influences via which she and her siblings undertook collective authorship of their “plays”. One of Charlotte’s very first impulses in introducing herself as a writer is to describe the material site of reading and writing, including the material and textual inspirations, their origins and means of distribution to the household, and their place alongside other household activities. Those involved with the production of these materials are also known and introduced as actors with personalities—even before the advent of the inspiring toy soldiers was chronicled:

Once Papa lent my sister Maria a book. It was an old geography and she wrote on its blank leaf, ‘Papa lent me this book’. The book is an hundred and twenty years old. It is at this moment lying before me while I write this. I am in the kitchen of the parsonage house, Haworth. Tabby the servant is washing up after breakfast and Ann, my youngest sister (Maria was my eldest), is kneeling on a chair looking at some cakes which Tabby has been baking for us. Emily is in the parlour brushing it. Papa and Branwell are gone to Keighley. Aunt is up stairs in her room and I am sitting by the table writing this in the kitchin. Keighley is a small town four miles from here. Papa and Branwell are gone for the newspaper, the Leeds Intelligencer, a most excellent Tory news paper edited by Mr [Edwa]rd Wood [for] the proprietor Mr Hernaman. We take 2 and see three newspapers a week. We take the Leeds Intelligencer, party Tory, and the Leeds Mercury, Whig, edited by Mr Baines and his brother, son in law and his 2 sons, Edward and Talbot. We see the John Bull; it is a High Tory, very violent. Mr Driver lends us it, as likewise Blackwood’s Magazine, the most able periodical there is. The editor is Mr Christopher North, an old man, 74 years of age. The 1st of April is his birthday. His company are Timothy Tickler, Morgan O’Doherty, Macrabin, Mordecai Mullion, Warrell, and James Hogg, a man of most extraordinary genius, a Scottish shepherd. Our plays were established: Young Men, June 1826; Our Fellows, July 1827; Islanders, December 1827. Those are our three great plays that are not kept secret. Emily’s and my bed plays were established the 1st December 1827, the others March 1828. Bed plays mean secret plays. They are very nice ones. All our plays are very strange ones.(Alexander and The Brontës 2010, pp. 3–4)

For Charlotte Brontë, authorship begins with a book, with writing in a book, one that is passed down and remains part of the environment. In this case; the book has remained longer than its inscriber—their elder sibling Maria had died in 1825, her inscription surviving and continuing to keep its place in the writing and reading environment that was Haworth. If authorship begins with a book, however, that is not its only province. Writing happens in the kitchen with co-authors absorbed with various domestic tasks and others “gone” to procure more reading materials. Emily’s journals similarly present the doings of (for example) her father, her aunt in the kitchen, the Empresses of Gondal and Gaaldine, and Queen Victoria (whose coronation directly preceded similar events in Gondal), all on the same page and without any distinction among them (Barker 1995, p. 271). At Haworth, writing and reading are collective activities that exist alongside and on a continuum with other kinds of domestic work and domestic spaces, a parallel with contemporary fanfiction authors’ notes detailing the conditions of work and family that may have interrupted or informed the fan text being disseminated.

In Charlotte’s early manuscript, the people of Haworth and their doings are presented as being of a piece with media personalities and creators and their doings (or, in Emily’s case, Queen Victoria’s). At this point, the children are writing outside the literary marketplace, but they see it as part of their world and vice versa. It is not surprising that Charlotte’s account of Haworth’s media landscape leads seamlessly to her account of the siblings’ own creators’ origins. The Leeds Intelligencer, the “most excellent Tory newspaper” to which Charlotte gives prominent place, had directly established print media as a participatory space open to Brontës. A single issue of this newspaper—the January 29 edition, just a few months before this March 1829 manuscript—features letters to the editor by and about the children’s father Patrick Brontë (Leeds Intelligencer 1829). A reader has written to challenge Patrick Brontë’s previously published account of Catholic influence on early British Christianity, although the writer also defends Brontë as “a most upright, faithful, and conscientious priest” based on personal experience of his sermons and his parish. At issue is Brontë’s claim, requoted in the letter, that ‘the gospel light that first illumined the darkened minds of our forefathers emanated from the papal throne”, to which the reader objects at lengths, citing various histories of Christianity in the British Isles in considerable detail. In “Mr. Brontë’s Second Letter” (so entitled and printed alongside this response to his first), as an Irish native and member of the Church of England clergy, Patrick Brontë wants to set the record straight about his position in favor of the continued union of Church and State: “Should your invitation to answer me, have been duly attended to; have the goodness to place that answer and this letter in juxta-position…” The dispute’s nationalist and anti-clerical underpinnings are hardly irrelevant to the Brontë siblings’ future literary output: the attraction and repulsion of the Catholic Church is a central theme of Charlotte Brontë’s novel Villette. More pertinent here, however, is the way this exchange presents media interactivity as an ordinary part of Haworth life: their home is a recognized cultural force; there’s a clear precedent for family authorship, and print is a place for contestations among readers and writers. In this world, readers are part of the media they consume. Occupying multiple roles as writer, topic, and reader in a single text appears quite ordinary, of a piece with Maria’s adding her name to the family geography.

The Leeds Intelligencer more broadly holds other lessons that the young authors seem to have internalized, among them that the Brontë family might comfortably share page space with “the discovery of the human skeleton at Wheatley, near Doncaster” and the account of the ensuing inquest; or, for that matter, with Thomas Love Peacock’s “Touchandgo” (uncredited in the Intelligencer), a satirical verse inspired by “real life” rogue bankers that appeared under the boldface newspaper heading POETRY. This poem, first published in the Globe and Traveler (and credited only to the Globe in the Leeds paper), would ultimately go on to partially engender Peacock’s 1831 novel Crotchet Castle. Though this fate could not be known to the Brontë children in 1829, they might well have recognized the character name “Touchandgo” in the later novel from this edition of a paper that so prominently featured their father. Regardless of their future awareness of this detail, the trajectory of the poem from newspaper to newspaper to novel underscores several pertinent features of the literary and media landscape the Brontë children grew up in and around. It exemplifies the heterogeneous and interactive authorial space that was this regional newspaper; the close relationship between high and low culture (Peacock had been a close friend of Percy Bysshe Shelley and other Romantics); and the porous relationship between and among poetry and prose, on the one hand, and fiction and “real persons”, on the other. Peacock’s poem was based on the banker Rowland Stephenson and his assistant, whose fraud and theft led to the fall of a bank and whose escape to Savannah, Georgia, was by this point extremely well-known and had been much covered in the newspaper—thus the newspaper is both source and venue for poetry. Last but by no means least, the paper daily featured editors playing a large and active role in shaping newspapers and their contents, emerging as characters in their own right.

This single issue of a newspaper shows how the publications taken regularly at Haworth set the stage for the Brontë children’s literary output specifically—even down to the lack of distinction in their journals among different kinds of information and contexts. It also demonstrates that the understanding of authorship and literary production they would have gained as regular readers of such papers was by no means peculiar to them. The Leeds Intelligencer and other papers like it should be recognized as highly interactive and multiply generative media that united many discourses and kinds of writing in a single space. When scholars such as Carol Bock and David Latané theorized “the birth of the Victorian author” from the Victorian periodical press archive, they did not evoke the Intelligencer specifically, but Bock did center her argument about authorship and the periodical press on the Brontës and their “coming-forward” as authors via their juvenilia’s engagement with Fraser’s Magazine (Bock 2001; Latané 1989). The Intelligencer also models an active and highly participatory readership. The paper was not a serialized affair, or course; it would be largely comprehensible to a visitor to the area who happened to pick up an issue. Yet, as a local paper, it is clearly aimed at a regular readership conversant in its environment and concerns. Such readers would be expected to check in and out and play catch-up if they missed some ongoing coverage of local issues and would furthermore be expected to pick and choose within a given edition in accordance with their interests, available time, access, etc. This “dip in/dip out” model of readership is far closer to the experience of reading fanfiction on the internet than that of reading even the most sprawling serialized nineteenth-century novel, where readers would need to follow along so as not to miss the thread of the story (although there are also many long, serialized fanfics that exceed this hypothetical sprawling three-decker novel in length).

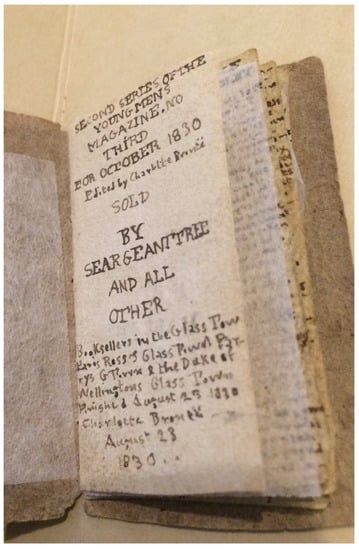

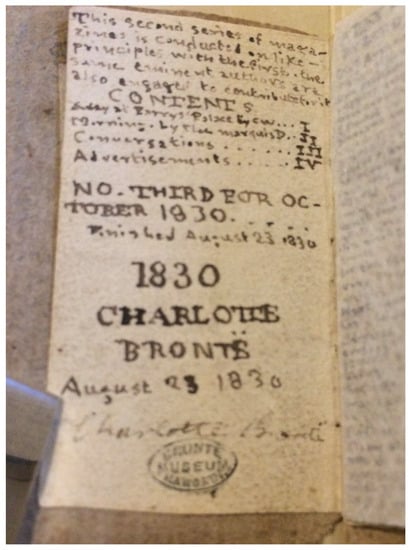

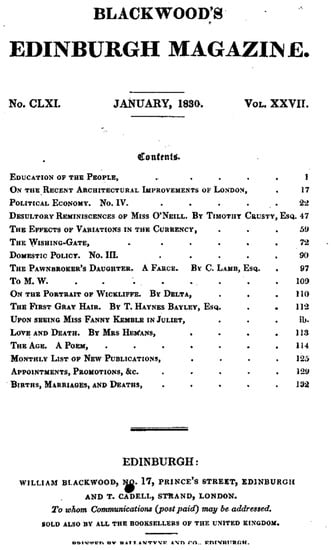

The formats of the Brontë siblings’ early self-publications respond not only to “audience” need (toy soldier-sized) but to this media environment. As producers as well as writers, the siblings modeled themselves and their books after beloved publications, taking on roles and invented personae to match the editorial and writerly personae they knew. Most famously, Blackwoods’ Magazine, “the most able periodical there is”, provided the format and source texts for many of the early Glass Town and Angrian texts (see Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 2.

Title page of the October 1830 Young Men’s Magazine pictured above.

Figure 3.

The table of contents of the October 1830 Young Men’s Magazine.

Figure 4.

Blackwood’s Table of Contents. Available online: https://archive.org/details/sim_blackwoods-magazine_1830-01_27_161 (accessed on 18 August 2022). Public domain.

Figure 5.

The Advertisements page of the Young Men’s Magazine.

As it is for fanfiction writers today, the presence of an interactive media space as forum and model was a profound influence on the way the Brontës produced their sagas. In both eras, by allowing for a diversity of lengths, formats, modes, and focuses unavailable to the commercially published novel, these media spaces present an expanded and expansive field for fiction.

4.3. The Codex as Intergenerational Interactive Media

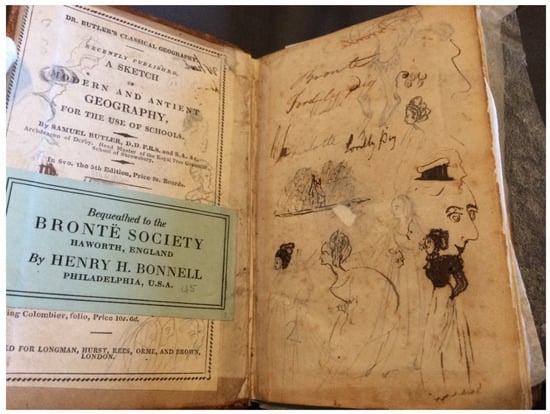

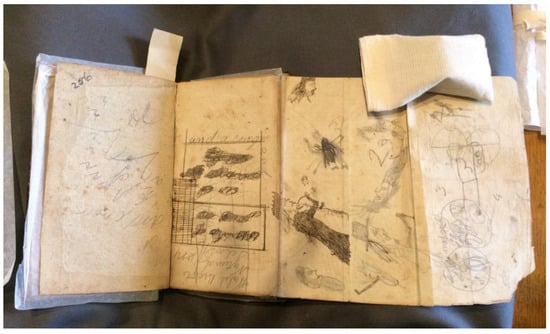

This interactive and familial relationship to media was hardly restricted to creating tiny new books or imitating journalistic media. The Brontë children were no passive consumers of books, either, a precedent Charlotte also establishes in her early description of Maria inscribing herself into the family geography. That the chronicle of the Brontë siblings’ writing career begins by describing such an act is only appropriate—Emily will go on introduce her own later creation, Catherine Earnshaw—like poor Maria, already dead at the start of her story—by just such a device. We meet Catherine via the inscription of names, first on the wall of the eponymous house in Wuthering Heights marked “Catherine” and her various possible surnames, and then on a Bible: “It was a Testament, in lean type, and smelling dreadfully musty: a fly leaf bore the inscription ‘Catherine Earnshaw, her book.’” The model of print books as interactive media was passed down to the children by the “one hundred and twenty year old” books in their schoolrooms, and this was far from unusual. Writing in family books was a common practice; readers, especially child readers, would be expected to leave their marks, as Pat Crain has discussed at length in her excellent Reading Children (Crain 2016). Andrew Stauffer’s collaborative web archive Book Traces (n.d.) displays hundreds of digital images of such readerly traces left in nineteenth-century books. The notion of the codex as a one-way conduit to passive consumers is itself an anachronistic projection--first from the era in which books were common and paper was cheap and plentiful and then from the digital and internet eras by way of contrast to themselves. This misapprehension of the nature of books and their role in everyday lives sometimes leads scholars of the digital era to overestimate the passivity of the media environments that preceded their own. The Brontës suffered from no such delusions (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The Brontë family copy of Dr. Butler’s Classical Geography.

4.3.1. Angria, Empire, and Geographies

The Brontë children learned by the example of the family library that books were for writing in, and thus grew up assuming any such real estate was to be considered as open to their contributions and authority. The Brontës appropriated and altered military history, geographies, maps, and their corresponding continents to the service of their imagination. This understanding of their world, media and otherwise, was clearly established by their much loved and much altered geography book (albeit a more recent one than the one into which Maria inscribed herself).

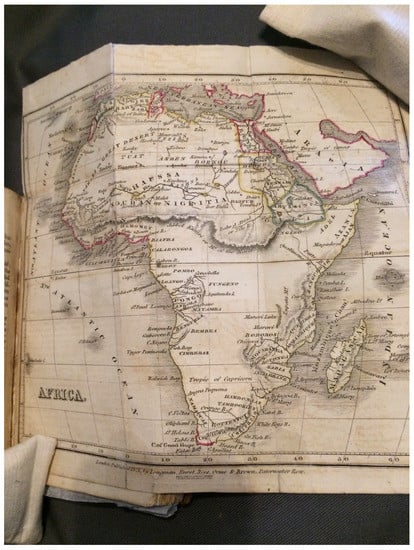

It is well-known that Goldsmith’s Geography provided the Brontë children with territory for their imaginations to run wild—in the margins and on the endpapers, and on a map of Africa (see Figure 7 and Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Map of Africa from the Brontë copy of Goldsmith’s Geography (Rev. J. Goldsmith 1823).

Figure 8.

Back of a foldout map of Europe from the Brontë copy of Goldsmith’s Geography.

The texts’ regulatory authority ended at the printed line—sometimes not even then, as Charlotte could be known to correct her grammar book and Emily added place names from her invented islands Gondal and Gaaldine (see Figure 9):

Figure 9.

Emily’s additions on Gaaldine to the Goldsmith’s Geography dictionary of proper names.

As Joetta Harty has shown in the context of a broader argument about childhood paracosms (detailed imagined worlds such as Angria and Gondal were not peculiar to the Brontës), the Haworth geographies provide “striking evidence” of how period geography texts inspired children to world creation (Harty 2016, p. 99). Unfilled spaces on pages and maps alike were “blank” and could be filled with whatever the children chose, image or word, their imagination the only governing authority.

Of course, it is crucial to acknowledge that none of these were “blank books” in any sense, however much the children may have written in them. A more harmful influence and legacy is on display on these pages as well and shaped the way the Brontës imagined their colonial African country as decisively as any map. The Africa Goldsmiths’ portrays is compelling and contradictory: it has been reduced to “barbarism” only by the “villainy” of slave traders, having previously been home to “several kingdoms and states eminent for arts and commerce”. Its deserts, the textbook explains to the children of people who consider themselves to be an island race, are like “oceans”, and its oases are like “islands”. However, Africa is also, on the same page, “the country of monsters” and “predatory animals reigning undisturbed in the vast deserts of that continent”, deserts that are then rendered by blank spaces on a map (Goldsmith 1823). By contrast, an older family geography presents the Irish, their father’s heritage, as being “hardy” and “nimble”, presumably, it explains, because of the “Moisture and Temperament of the Air” (Goldsmith and Goldsmith 1768). From their geographies, then, the Brontë children learned that the very air they breathed made them superior to Africans even as Africa was presented as a land of almost impossible imaginative potential. The invitation these books extended is apparent on their pages: Africa, map and imagined continent alike, were theirs to populate as they chose. It was at once a large blank space to be projected upon, a land of great kings and cultures laid low by Europe, and inherently barbarous, all at the same time. The nest of contradictions that is the Bronte siblings’ adolescent and later young adult imagining of Glass Town and Angria bears direct relation to these much beloved and inhabited geographical textbooks. Along with their enthusiastic colonialism, the Bronte children imagined Africans who fought as respected foes and who, though vanquished by British military superiority (and the help of an island Genii, who much prefers the colonists), refuse to accept British rule and continue to rebel., One African character, Quashia Quamina, is given agency and voice, perhaps reflecting abolitionist texts and sympathies (Heywood 1989; Meyer 1996). As Zaina Ujayli points out, however, the African characters are never free of a mix of period Orientalist and anti-Black stereotypes, even at their most sympathetic, and the villainy of white characters is often portrayed in racialized terms (Ujayli 2020). Ujayli suggests that some of these contradictions may be reflections of the competing interests of Charlotte and Branwell, but they also reflect the conflicting ideologies of the time, as reflected in Goldsmith’s self-contradicting account of Africa. Like so much fanfiction, the Brontës’ Angrian tales reproduced the prejudices and systemic injustice encoded in their sources. An idealized account of fanfiction has it pushing back on institutionalized power structures, and it can, but it also, by its very nature, replicates these structures, sometimes inadvertently, but often enthusiastically. Both are certainly true of the Brontë texts.

4.3.2. Zamorna, Gender and Grammar

While these texts reproduce the political and racial dynamics of Empire—not entirely uncritically, but certainly not critically enough—these are not the only power dynamics that drive the sagas. Much of Charlotte’s novelistic (or novella-istic) Angrian fiction focuses on the Byronically womanizing Zamorna and his adoring, pining, occasionally dying, and often indistinguishable lovers. In The Spell, Zamorna is taunted with having to bury his infant son in the arms of its mother, whom Zamorna had abandoned to pursue another woman, leaving his wife to die of a broken heart. Zamorna insists she knew he never stopped loving her despite his having left her for another; his interlocutor suggests he might find this wife equally attractive in her grave as he ever had in life. To be fair to Zamorna in this instance, the preface to the novella also identifies it as a spiteful embellishment written by his brother: “The Duke of Zamorna should not have excluded me, for the following pages have been the result of that exclusion! …here I fling him my revenge” (Alexander and The Brontës 2010, p. 67). But then, part of the revenge is the mix of truth and fiction: “There are passages of truth here which will make him gnash his teeth with grating agony”. In Mina Laury, the title character, we are told, “belonged to the Duke of Zamorna… She had but one idea, Zamorna, Zamorna! It had grown up with her, become part of her nature. Absence, coldness, total neglect for long periods together went for nothing. She could no more feel alienated from him than she could from herself” (Alexander and The Brontës 2010, p. 192). When she is assaulted by another man, Hartford, who with the cry “Nay, you shall not leave me, by heaven! I am stronger than you!” stops her from leaving and then “clasped her in his arms & kissed her furiously rather than fondly. Miss Laury did not struggle”. (p. 196) He relents, and she ultimately explains she cannot marry him—not because he’s just attacked her, but because her love for Zamorna is so great that even if she were to marry Hartford, at one look from Zamorna, she would “creep” back to his side “like a slave”. Zamorna, hearing of this encounter, reacts badly if predictably: “What drivelling folly have you let into your head, sir, to dare to look at any thing that belonged to me? Frantic idiot!” (p. 204) Then, he calls for pistols and shoots his would-be rival. After this, Zamorna meets with Mina Laury and “offers” her Hartford as a husband. She is so horrified she faints and, after Zamorna has tested her faint to make sure it is genuine, when she wakes, he rewards her with the news that, after all, it was only a love test and he’d actually shot the attacker he’d just suggested she marry. She “shuddered”, but, we are told, “so dark and profound are the mysteries of human nature” that “this bloody proof of her master’s love brought her love more rapture than horror” (p. 216).

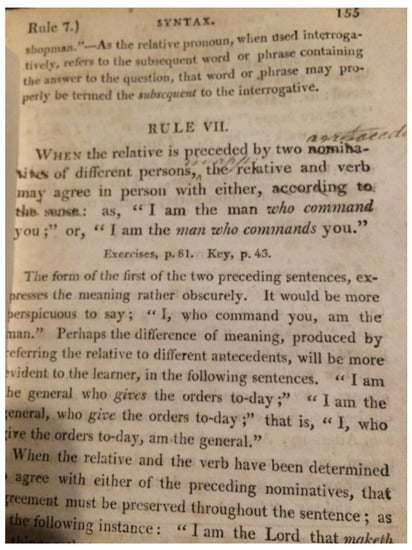

Charlotte was well-versed in Byron, as is fully obvious, but he was hardly the only source for such dynamics. Observe the grammar book that Charlotte corrected (see Figure 10).

Figure 10.

English Grammar as annotated by Charlotte Brontë.

Charlotte corrects the grammar but leaves the examples umremarked: “I am the man who command you” or, “I am the man who commands you” or, “I, who command you, am the man”. Perhaps so, the emendations seem to suggest, but Charlotte’s is the hand who corrects you! Charlotte does not extend such power to her female characters like Mina Laury; like many fanfiction writers, Charlotte talks back to her books through the act of writing, much more so than in what she represents. As Timothy Gao has argued, the omnipotent Genii are more than just figurative stand-ins for the young Brontës; they are an entire authorial mode, one that signals play and power both (Gao 2021). Throughout the juvenilia, Charlotte figures herself, again and again, as masculine authority, not in opposition to it. The Brontës’ relationship to these instructional texts is an allegory of the book as interactive media, open to being inscribed and transformed but also inscribing ideology onto their participatory readers.

5. Angria Contra Publishing

The Glass Town, Angria, and Gondal sagas are not, of course, the Brontë siblings’ only creative work. Charlotte published four novels; Anne two, Emily one, and the sisters also published a collection of poetry. Branwell’s Angria works are the sum total of his fiction, and though he published poems in local and national newspapers, he published them under one of his Angrian pseudonyms, Northangerland. Although not all their published works met with success (the volume of poems sold only two copies), Charlotte’s Jane Eyre and Emily’s Wuthering Heights remain two of the most widely read and beloved novels. Charlotte, who outlived all her siblings, went on to become one of the most respected authors of her day. Anne, while outstripped by her sisters in fame then as now, has gained in popularity since feminist perspectives have highlighted her comparatively less compromising attitudes towards abusive men—perhaps most memorably in Kate Beaton’s comic “Dude Watchin’ with The Brontës”, which the artist glosses as: “Anne why are you writing books about how alcoholic losers ruin people’s lives? Do not you see that romanticizing douchey behavior is the proper literary convention in this family! Honestly” (Beaton n.d.). While they may now be collectively known as “The Brontës”, the sisters are understood as separate authors with separate styles and identities, a separation which, as professional authors, they cultivated and insisted upon. Famously, Anne and Charlotte went to London to prove that the works of Currer, Acton, and Ellis Bell were written by separate persons (London 2019). Because of this success in publishing and their subsequent enduring fame, critical literature on the juvenilia has tended to understand the Angria and Gondal works as apprenticeship or practice for greater things. The later Charlotte, even later than the one who penned an essay known as “Farewell to Angria” as she embarked on her quest to become a published novelist, would likely be pleased to agree. While in “Farewell”, Charlotte wrote that she needed to “quit for a time that burning clime where we have sojourned too long” because “the mind would cease from excitement & turn now to a cooler region”, she still referred to herself as the author of “many books”, by which she meant the Angria texts (Alexander and The Brontës 2010, p. 314). Later, however, she further distanced herself from Angria and contributed greatly to the myth of her own mystic, singular authorship (London 2019). Similar moves have been common among more contemporary writers who “got their start” in fanfiction and went on to repudiate or condescend to this earlier work as apprenticeship, often after having drawn heavily on it to launch their careers—much like Charlotte, whose stormy and coercive Mr. Rochester owes much to her earlier creation Zamorna. Charlotte, it should be noted, was the only one of the siblings who thought this repudiation necessary, and she went even further to construct her sister Emily’s author-image, even to the extent of changing her poems, for the 1850 reissue of Wuthering Heights (Malfait and Demoor 2015). Emily continued to write in the Gondal universe after Wuthering Heights was published and stopped only with her death. For a time she kept separate notebooks for “Gondal poems” and for other verse, but a third notebook made no such distinction (Alexander and The Brontës 2010, p. xxviii). Fewer of Anne’s poems exist, and only twenty-some are Gondal-related, but of these some were written as late as 1846. Christine Alexander argues that Anne kept more separation between Gondal and her life than did Emily, and that it was largely for Emily’s sake that Anne kept the fantasy world alive—but that she did keep it alive is clear (Alexander and The Brontës 2010, p. XL). Branwell, for his part, neither quit Angria nor published other fiction. The youngest any of the siblings left their collective creative enterprise was 23, and even by that time, Charlotte’s Angria writings would already surpass in volume (though not size!) the entirety of her published novels.

The Web of Childhood, Fannie Elizabeth Ratchford’s 1941 study of the Brontë juvenilia, contrasts the then already voluminous critical literature around the Brontës and their novels with the paucity of attention paid to the Angria and Gondal works. As Ratchford explains, Elizabeth Gaskell, the first and then still the most influential Brontë biographer, mentions receiving a “packet” containing some of these texts but largely left its contents undiscussed in her book. Clement Shorter, who purchased Charlotte’s letters and papers—including the packet Gaskell mentioned—from her widower in 1894, published two volumes of her letters but “the [Angria] manuscripts as a whole he passed over as worthless”, singling out only “A Tale in Ireland” as “’Perhaps the only juvenile fragment which is worth any-thing is also the only one in which she escapes from the Wellington enthusiasm’” (Ratchford 1941). Ratchford remarks somewhat drily that had Shorter read the material at any length, he would have known that Charlotte soon abandoned the Duke of Wellington for his son in their chronicles and suggests that in any case a “Byron enthusiasm” would be closer to the mark. As Ratchford acknowledges, it is not hard to discern at least one reason the juvenilia has received shorter shrift: “It would seem that neither Mrs. Gaskell nor Mr. Shorter was equal to the forbidding and apparently interminable task of reading in chronological order the hundreds of pages of microscopic hand printing which guarded the secret of Charlotte’s childhood and early womanhood”—and in all fairness, it is a daunting task. From a fan studies perspective, though, Shorter’s denigration of the manuscripts on the basis of “enthusiasm” and what would now be understood as fannishness, and the equation of value with the absence of such fannishness, strikes a familiar enough tone. Similarly, from a fanfiction writer perspective, a gatekeeping critic and editor who disdainfully dismisses an entire body of fannish writing as valueless without having read more than a small sample (if that) is likewise a familiar phenomenon—the kind that has traditionally led many fanfiction writers with professional ambitions to cover their fannish tracks. Shorter’s dismissal of the Angria manuscripts as “juvenile” equally plays into the cultural denigration of the tastes and creations of young people, especially women.

Ratchford identifies one other likely factor for ignoring the manuscripts in favor of the letters: “Perhaps they found themselves unable to reconcile the contradictory revelations of letters and manuscripts and chose the more understandable one—the letters”. In context, it is clear she means the more understandable content of the letters, but the same holds true at the generic level: letters are a recognizable and coherent genre in themselves, usually written by or perhaps to a single person. As a publishing category, collections of author letters were recognizable, acceptable, and marketable, tending to shore up the individual model of authorship even as they may include exchanges suggestive of collaboration. By contrast, whereas juvenilia have been understood to be youthful writings since the seventeenth century, the Brontë writings in particular challenge the notions of originality, individual authorship, and generic consistency on which the publishing industry has built its commercial and organizational models.

A fanfiction perspective provides a more generative approach to texts such as the Brontë’s “juvenilia”. Not that there is anything wrong with the term “juvenilia” per se, but it does suggest that the primary interest of the texts it references lies in insights about the more mature authors their writers would become. Juvenilia gains scholarly interest and literary credentials by authorial association. The Brontë siblings certainly came to know that what they were doing in their private writings was different from what the publishing world demanded of novels, although as I have argued, they had closely patterned their work on other contemporary models of authorship and publication. They transformed their work and praxis to become novelist authors—and Charlotte continued to transform it further after her siblings’ deaths. While period reviews often responded to the Brontës’ novels as “wild” and “untamed”, the violence, sex, and politics in Glass Town, Angria, and Gondal make clear by comparison that this is far from the case. When these writers’ imaginations were beholden to no commercial interests or consistent generic conventions: no marriage plot; no gendered constraints on content; no public morals; no three volume format preferred by period publishers, they produced very different work than when they wrote for publication. Designed to be read by toys and to be illegible to almost everyone else, these sagas were created by the siblings for one another, sometimes by writing, sometimes by imaginative play or oral storytelling or illustration—an analogue transmedia extravaganza. Despite the vast quantity of the Angria material now available (for which we owe the tireless efforts of a handful of scholars and their patient eyes, most recently and extensively Christine Alexander), the writings remain largely inaccessible—if no longer illegible—to a readership for whom they were never intended: those who approach these heterogeneous texts through the lens of the singly authored published novels of their creators. If you are looking for “more like Jane Eyre”, you are likely to be disappointed, because despite Angria being full of elements that look forward to Jane Eyre, the genre and conventions are entirely different. Like the historical referents of period newspapers and periodicals with their open acknowledgement of interruptions, discontinuities, strong-willed editors and multiple pseudonyms, fanfiction provides a different context and tradition for the reading and understanding of such fictions.

6. The Brontë Family Fandom Fandom

I am not only interested in thinking about the Brontës as fanfiction because I am invested in the theoretical questions such investigations can illuminate. In this paper, when I look at the young Brontës as a family fandom, I do so partly because I have been fascinated by Brontës since I faked sick in eighth grade to finish Jane Eyre. As a critic and reader, I am invested in finding new ways of approaching their work. When this essay examines the writing environment of Haworth parsonage as a complex exchange between different kinds of materials and activities, my perspective is informed by a number of interests, intellectual and affective, that were strong influences earlier in my writing process (like the Brontës’ toy soldiers) but ended up being less central. An earlier draft had me working through assemblage theory as derived from the works by Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari, and Bruno Latour, as I have discussed elsewhere with regard to fanworks. My thinking has also been influenced by Louisa Stein and Kristina Busse’s account of how fanfiction authors “thrive on limitations of technological interface, genre, cultural intertext, and community” (Busse 2017, p. 121). Although I have at times been unsure how this distinguishes fic writers from other authors, my sojourn with the Brontës has me thinking that perhaps it is the thriving that sets them apart—although “thriving” is not a term often associated with the family, it seems to apply to their lives in writing and imagining Angria and Gondal. My argument here also has less traditional scholarly influences. It is shaped by what the curators of Haworth Parsonage have collected and exhibited: the museum makes its own case for the Parsonage’s material influence on its author denizens. These exhibits were designed based on what is in the tiny manuscripts, letters, diaries, and other material objects they display and are certainly scholarly, but they also feel fannish—the museum’s enthusiasm for its objects is palpable, filled with invitations to imagine beloved writers penning beloved texts within its walls for the predecessors of the toy soldiers displayed on a children’s bed. This essay is also conditioned by my own complex love of the Brontës and the frisson of seeing the physical books they read and wrote in. I do not think that my enthusiasm for the Brotnes’ tiny books, my distress at their textbooks’ portrayal of Africa, or my perpetually irritated admiration for Charlotte, are incompatible with my scholarship. That the fannish and the scholarly need not be opposing categories is one of the founding principles of fan studies. And yet, early writers in the field nonetheless insisted that “acafans” be “fans first” as scholars were called upon to prioritize the fannish over the academic, affective attachment over adherence to disciplines founded on dispassionate analysis. While understandable, this insistence also underscored and reinscribed the very division the young field sought to bridge—one that amateur Brontë scholars and enthusiasts have been bridging for the better part of two centuries. “The Brontë family fandom” might just as easily refer to the generations of fans and their collections, essays, blogs, adaptations, fanfiction, merchandise, societies, and pilgrimages like mine. Haworth Parsonage today is a fannish space—and, as I argue here, it always was. The Brontë children may not have understood themselves as writers of fanfiction, but they did understand themselves as an active community of readers, writers, and participants bound by shared and sometimes competing enthusiasms, engaged in a kind of serious play. They are hyper-aware of their surrounding media environment and model their tiny writing on its diverse elements. They were characters, writers, editors, printers, binders, and audiences for their work (not to mention omnipotent Genii). They intertwined real life and fantasy, real politics and invented; they satirized and contested with their sources and with one another. Call it what you will, this is, fundamentally, what fanfiction does.

And, two centuries later, this is still what is happening in the worlds they created, which have enjoyed a livelier existence in transformative works than in critical reception. In Antonia Forest’s 1961 Peter’s Room, other fictional children make up stories based on Angria and Gondal after having been assigned them in a school project and also spend several chapters arguing about whether the created worlds that absorb them were a triumph or a waste of time for their authors. Forest’s engagement with these worlds in turn inspire another, far more extensive fictional treatment. Beloved fanfiction writer A. J. Hall, whose Sherlock fanfic I discussed in Fic and have taught for years, wrote a multivolume Queen of Gondal series for over ten years, matching her Brontë sources in convolutions, interruptions, intrigue, and complexity. Sources come and go (Cabin Pressure? Life on Mars? Pride and Prejudice?); minor characters show up as the center of a shorter story, disappear for many volumes, resurface back in the margins or not at all. Sherlock is a Crown Prince; Gondal and Gaaldine are in the Balkans; it is the late seventeenth century, as many well-researched details attest and a number of plot elements belie. As the author’s note to a “genre fusion: Murder in Ruritania” advises, “in a choice between genre conventions and naturalism, genre conventions win hands down” and, this being Sherlock fanfiction, one of these genre conventions is that Sherlock and John are extremely gay for each other (Hall 2011–2012). The stories are available on the AO3 platform but also as carefully designed downloadable ebooks on the author’s website. Many of the stories were written as gifts for other writers. Another writer contributed an epistolary chapter in verse, inspired directly by one of Emily Brontë’s poems. The author website describes the saga as “a quasi-historical AU of the BBC Sherlock series set (more or less) in three fantasy kingdoms devised by the Brontë children” about a “supremely dysfunctional bunch of royals and their friends, enemies, lovers, haters and associates, set in the late seventeenth century in three fictional countries located in the Balkans but with weather, geography, geopolitics and culture arranged to suit the whims of plot and atmosphere” (Hall n.d.b). The AO3 series note, in keeping with conventions of the site culture, includes some warnings and more specific information about genre and ethnicity:

…readers should bear in mind that this saga contains the doings of a set of supremely dysfunctional more-or-less European Royal families steeped in the “divine right of kings” ideology of monarchy, filtered through an early nineteenth century Romantic/Gothick sensibility and then depicted using the freedom of expression afforded by the early twenty-first century internet.

Furthermore, if the Greek myths contemplated it, some member of the Royal houses of Gondal, Angria or Gaaldine has probably put it into practice somewhere.

Gentle reader, consider yourself advised accordingly.(Hall n.d.a)

I, of course, am delighted. Nothing pleases me more than when fanfiction does my work for me. I wanted to argue that Angria, Gondal, and Gaaldine are fanfiction, and here they are.

7. Materials and Methods

Some of the materials referenced in this essay are archived at the Brontë Parsonage library and are available only by application and appointment. Images are the author’s photos taken with kind permission from The Bronte Society.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Utah College of Humanities.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the staff at the Brontë Parsonage Library.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Alexander, Christine, and The Brontës. 2010. Tales of Glass Town, Angria, and Gondal: Selected Writings. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, Christine. 1994. Readers and Writers: Blackwood’s and The Brontës. The Gaskell Society Journal 8. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/45185571 (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Barker, Juliet. 1995. The Brontës. New York: St. Martin’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, Balaka. 2016. Virgilian Fandom in the Renaissance. Transformative Works and Cultures 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, Kate. n.d. Dude Watchin’ with the Brontës. In Hark! A Vagrant. Available online: http://www.harkavagrant.com/index.php?id=202 (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Bock, Carol A. 2001. Authorship, The Brontës, And Fraser’s Magazine: “Coming Forward” As an Author in Early Victorian England. Victorian Literature and Culture 29: 241–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Book Traces. n.d. Available online: https://booktraces-public.lib.virginia.edu (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- British Library. 2011. The Brontë’s Secret Science Fiction. Available online: https://www.bl.uk/press-releases/2011/may/the-bronts-secret-science-fiction-stories (accessed on 4 June 2022).

- Brontë Blog. 2009. Charlotte Brontë’s Hobby. The Brontë Blog (Blog). May 26. Available online: https://Brontëblog.blogspot.com/2009/08/charlotte-Brontës-hobby.html (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Brooks, Cleanth, and Robert Penn Warren. 1938. Understanding Poetry: An Anthology for College Students. New York: H. Holt and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Busse, Kristina. 2017. Framing Fan Fiction: Literary and Social Practices in Fan Fiction Communities. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coker, Cait. 2021. Defining Fan Fiction: An Exercise in Archival and Historical Research Methods. In A Fan Studies Primer: Method, Research, Ethics. Edited by Paul Booth and Rebecca Williams. Iowa: University of Iowa Press, pp. 179–92. [Google Scholar]

- Coppa, Francesca. 2017. The Fanfiction Reader: Folk Tales for the Digital Age. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Crain, Pat. 2016. Reading Children: Literacy, Property, and the Dilemmas of Childhood in Nineteenth-Century America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Alexandra. 2018. Literature fandom and literary fans. In A Companion to Media Fandom and Fan Studies. Edited by Paul Booth. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Fathallah, Judith. 2017. Fanfiction and the Author: How Fanfic Changes Popular Cultural Texts. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Timothy. 2021. Virtual Play and the Victorian Novel: The Ethics and Aesthetics of Fictional Experience. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, Oliver, and John Goldsmith. 1768. The Present State of the British Empire in Europe, America, Africa and Asia. Containing a Concise Account of Our Possessions in Every Part of the Globe, Etc. [Compiled by Goldsmith]. London: W. Griffin. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, Rev. J. [Richard Phillips]. 1823. A Grammar of General Geography, for the Use of Schools and Young Persons. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green & Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, A. J. (as AJHall). 2011–2012. “The Curious Incident of the Knight in the Library.” Part 6 of the “Queen of Gondal” Series. Available online: https://archiveofourown.org/works/302826/chapters/484437 (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Hall, A. J. (as AJHall). n.d.a “The Queen of Gondal” Series Description. Available online: https://archiveofourown.org/series/7681 (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Hall, A. J. (as AJHall). n.d.b About. Available online: https://ajhall.net/about (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Harty, Joetta. 2016. Imagining the Nation, Imagining an Empire: A Tour of Early Nineteenth-Century Paracosms. In Home and Away: The Place of the Child Writer. Edited by David Owen and Lesely Peterson. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [Google Scholar]