Abstract

Using statistical data, scholarly research, institutional models from higher education, and highlighting key personages from the academy and the business world, we argue that including Buddhism-related content into the general education of students can offer a powerful avenue of reform for the humanities in American universities. The article shows how humanities-based skills are becoming more desirable in today’s business environment, and demonstrates how the skills that Buddhist Studies—and religion more broadly—provide are consistent with those needed in today’s global and integrated technological world. Utilizing the Universities of Harvard and Arizona to help frame the discussion, the paper outlines the history of the American general education system, the ongoing crisis in the humanities, how Buddhism fits within the humanities viz. religion, and specific ways to implement Buddhism-related content into the academy domestically and internationally.

1. Introduction

Buddhism is a universal religion that originated in India in the fifth century BC and spread to Central Asia, Southeast Asia, and East Asia in subsequent centuries. It has disseminated into the Western world in earnest over the past two hundred years, and is now one of its fastest-growing and intellectually stimulating religions. Buddhism’s sophisticated philosophy, vast textual traditions, and exquisite painting, calligraphy, architecture, and sculpture invite students and scholars—without any religious proclivity—to delve into the wealth of this extraordinary human achievement, absorbing its content into academic research and the curriculum of higher education.

Western secular universities introduced Buddhist curriculum roughly 150 years ago. Sanskrit and Pali scholars of seventeenth-century Europe were the first to teach Buddhism in the West, but its scope was very small, and limited to philology and language studies (Prebish 2002, p. 18; Li 2009; De Jong 1985). Buddhist-related courses entered the sequence of American university curriculum with the rise of Asian research and religious studies after the Second World War. As a result of the development of American immigrant society and the promotion of ethnic cultural diversity, these courses are becoming increasingly popular in the United States.

To a large extent, the rise and fall of Buddhist education in the American university is closely related to the humanities and general education. Yet, there is a well-known and continuing crisis in humanities education, caused by various cultural and social circumstances. Polemical questions exist about the field’s practical relevance, political use, excessive academicism, and declining numbers (Bowen et al. 2014, pp. vii, 17–32; Stover 2017). This paper explores some of the opportunities that these recent crises provide with respect to the development of Buddhism-related courses and programs in the American university. The emphasis placed here on the American university is not meant as a contracting nationalism, but is merely salient in that our experience and examples derive from a background in the American educational system. Indeed, the forward-looking outlook that we advocate is important for higher education worldwide.

As the traditional liberal arts and humanities have expanded to include the subject of religion, the authors maintain that of all the religious traditions currently being studied today in higher education, Buddhism offers a unique opportunity to assuage these crises. Using statistical data, scholarly research, institutional models from higher education, and highlighting key personages from the business world and the academy, we argue that Buddhist Studies courses can, by their inclusion in the general education of American universities, increase the profile of the humanities and—as we demonstrate below—address the crisis in the field by expanding its relevance in today’s technology-driven commercial society

2. “Reform”

The notion of education reform, particularly with respect to the humanities, is thought-provoking and complex. The crisis in the humanities has caused many in the field to seek reformative modifications and transformation. But, what do we mean by reform in this instance? Do the humanities even need reforming, inasmuch as such a restructuring implies that there is something intrinsically wrong with the subjects and methodologies of the field? The question of strategy also becomes salient. Does reform here mean a return to a past time when humanities-based education thrived, or a jettisoning of previous modes of inquiry to conform to a set of future values, attitudes, and beliefs? In this regard, scholars have addressed the issue in a number of ways. In a relatively recent investigation, Sidonie Smith approaches the topic from the point of view of doctoral education. She claims that the current problems in the humanities began with the decrease in state support in the 1970s, the negative effects of which have reverberated into the present day. The way forward, in her view, is multifaceted and somewhat strident:

Beware the route of nostalgia; avoid the blame game of theory and identity politics; hold the vision of inclusive excellence in sight; muster data for evidence-based counternarratives to commonplaces about the sorry state of the academic humanities; recognize the larger community of activists throughout the academy and the resources they mobilize for making change happen; remember all the humanists and allies out there; and act to make doctoral education forward-looking for future humanists.(Smith 2016, p. 16)

This multidimensional approach is appropriate, as the factors at work in the field’s current state of affairs stem from a multiplicity of integrated issues that need to be confronted, which have led to declining numbers in undergraduate enrollment. Yet for some, deteriorating statistics are not even the main point. According to Michael Bèrubè, “... it is a crisis in graduate education, in prestige, in funds, and most broadly, in legitimation” (Bèrubè 2013). However, here, we in effect argue that this negativity is in the end misplaced. Like Smith, rather than engage in solidifying the past with a nostalgia that becomes unproductively negative, we assert that the humanities must look to the future with a positive and additive disposition. The below discussion reviews how the humanities relate to general education in American higher education, how the humanities in their present state can be understood in relation to society’s current commercial and humanistic needs, why religion and Buddhism are particularly suited to become an elemental aspect of today’s cultural and educational paradigms, and demonstrate—using the authors’ home institution—the means and methods whereby Buddhism-related academic content might be incorporated into a “reformed” American university predicated on the humanities.

The notion of reform here is a qualified one. For, in our view, there is nothing fundamentally wrong with the humanities or the American university that frantically needs fixing. To anticipate a sentiment from Harvard University mentioned below, the world has changed since the heyday of the humanities in American liberal education. The humanities and general education need to change and adapt as well. Of course, to some extent they already have, with a broader array of subject matters, courses, and departments (e.g., the Digital Humanities). Thus, when speaking of a “reformed” humanities or university, a better or alternative word might be “reinvigorated” or “refreshed” in advocating for an increased presence of Buddhism-related courses in general education. In any event, although reform may be a technically accurate characterization of our proposal, we are at the same time acutely aware that the concept of reform is a bit stodgy; that it has been overused and is virtually empty of any real dynamic sway. To affect its greatest impact in the academy and the world energetically, Buddhist Studies and the humanities must continue to cooperate in multidisciplinary research, increase the number and scope of Buddhist research centers as distribution hubs of Buddhist Studies courses, and make full use of the Internet and other communication technologies. Doing so helps cultivate a humanities-rich educational system that takes full advantage of the skills that Buddhist Studies can offer students.

3. The Humanities in American University Education

In spite of the current situation of the humanities, there remains a profound concern for humanistic education in the modern American university, which is generally understood to have originated from ancient Greek civilization (Kimball 2010, p. 13). The ancient humanities—such as logic, grammar, rhetoric (trivium), as well as arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy (quadrivium)—are the oldest subjects in the history of Western education, dating back over two thousand years (Kimball 2010, p. 147; Shen 2010; Wagner 1983). These have evolved in the present day into three branches called the liberal arts (or the arts and sciences), which have a general educational character: the social sciences, the physical sciences, and the humanities. The last of these traditionally included the subjects of literature, philosophy, art history, music, and languages. In the present day, the humanities have grown to incorporate religious studies, classics, musicology, and history (Bowen et al. 2014, p. 3; Flannery and Newstad 1998, pp. xvi–xix; Wagner 1983).

General education plays an important role in the curriculum design of American universities, and the humanities occupy a central place in this tradition while supporting academic freedom, university autonomy, and administrative neutrality (Bèrubè and Ruth 2016; Bok 1982). A salient example is that of Harvard University, a leading institution whose example helps inform higher education throughout the world. We include the example of Harvard as a way to start thinking about models of education, reform, and the future of the humanities. Harvard has a strong humanistic tradition, which continues to be a critical component of its educational system (Harvard University 1945; University of Chicago 1950; Huang 2006). There are not only a multiplicity of humanities departments, but also a large number of liberal arts courses in undergraduate education, especially general education. While these courses are constantly changing, the basic idea is that future citizens should have a strong foundation in the humanities, including cultural content from outside the U.S.

In the 1950s, the humanities and general education of Harvard University were principally based on practices dating back to religious reforms in Western Europe, which emphasized individualism, national tradition, social progress, and cultivating young people’s ability to adapt to society. Although it was mainly humanistic, it also highlighted the combination of humanities and practical technology and their need in a free society. Important to this discussion is that, with the rise of American religious studies in the 1970s, Buddhist courses were taught through newly established academic organizations such as the Center for the Study of World Religions and the Committee on the Study of Religion (Graham 1978; Shephard et al. 2011). In the 1980s, with the change of American society and the neoliberal reforms of higher education, foreign cultures became increasingly important (Spencer 2014, pp. 398–99). For example, Professor Tu Weiming, a contemporary representative of Confucianism (Weber 2016), has long taught Confucian ethics at Harvard University as part of general education. In our view, these additions were a great step forward in the curriculum development of the American university.

In recent years, Harvard University carried out a series of reforms that greatly enriched its general education and multicultural curriculum. In October 2006, the university proposed a general education reform agenda. It did so because “The world has changed since the last time the Faculty instituted a general education curriculum [c.1945]. So has the state of knowledge, and so has Harvard. We think that a general education curriculum needs to take these changes into account” (Task Force on General Education 2006, 2007). This reform affirmed the importance of religious curriculum in the general education of renowned American schools; although, its overt distinction between secular and religious thought struck some as problematic (Hollywood 2011, pp. 460–62). Harvard updated its general education program once again in 2019, with religious courses now classified into different categories according to their specific characteristics (Harvard College Program in General Education 2021).

Buddhist and Buddhism-related courses are an important part of the general education curriculum at Harvard. In Spring 2022, for example, they offer “Permanent Impermanence: Why Buddhists Build Monuments” and “Happiness”. Buddhist courses are taught mainly through units such as the Department of East Asian Cultures and Civilizations, the Department of History of Art and Architecture, the Department of South Asian Studies, and the Divinity School. Given Harvard’s continued role as a leading private institution in the U.S. and the world, its historical and ongoing concern for a robust general education curriculum provides a strong indication of the importance that the American academic system places on the humanities. In terms of the argument of this paper, it presents an example of how other institutions can incorporate Buddhist content into general education.

Nevertheless, this dedication to the humanistic notion of knowledge for its own sake—a concept dating back also to the ancient Greeks and their distinction between “theoretical knowledge pursued for its own sake and knowledge pursued for practical ends” (Gk. paideia)—is being powerfully questioned (Cuypers 2018, p. 703). In many ways, what is at stake here is the ultimate value and purpose of a university education. General education courses have been essential in attaining a university degree insofar as taking these courses—the great many of which lie in the humanities—lets the world knows that one has been exposed to a wide swath of thoughts and ideas (universities are not technical or trade schools, where one learns a specific skill) (Flannery and Newstad 1998, p. 4). Students are ostensibly more valuable to society with the university degree, for obtaining the credential has historically been a sign that one is broadly educated. Therefore, any diminishment of general education or humanistic learning—real or perceived—will lead to a less educated population and, thus, a diminished society overall.

4. The Practical Aspect of the Humanities

A plethora of research exists that investigates the troubling state of the humanities, which need not be reargued here (Geiger 2015; Cvejić et al. 2016; Rosenthal-Pubul 2018). However, a series of statistics can help frame our views with respect to the field’s present situation. In terms of government funding, National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) budget requests decreased 90 percent since 1979, given 2019 numbers (American Academy of Arts and Sciences 2021). In higher education, although the total number of graduates in the humanities has increased, this number has decreased significantly with respect to the total number of graduates university wide. The number of degrees awarded to humanities students was 20.7 percent in 1966, compared with 12.7 percent in 1993, and is now even lower (Kernan 1997, pp. 5–6, 245–58). The number of dissertation grants in the humanities amounted to 13.8 percent in 1966, compared with 9.1 percent in 1993, while by 2014 “humanities doctorate recipients were more likely to draw on their own resources than were doctorate recipients in engineering and the life and physical sciences” (American Academy of Arts and Sciences 2021). According to a report published by the Association of Departments of English (ADE):

In the four years since 2012, bachelor’s degree completions in English have fallen by almost 11,000, or 20.4%, from 53,840 in 2012 to 42,868 in 2016. The recent downturn is not confined to English but has affected all the humanities, especially history, where bachelor’s degree completions have fallen by over 9500 (27.0%) between 2012 and 2016, from 35,190 to 25,686.(Association of Departments of English 2018, p. 49)

An important and logical aspect of these declines is that as teaching positions decrease, humanities graduates have less job opportunities. At the graduate/professional level, many PhDs cannot find academic jobs, and as a result, the time and effort spent on research and writing in studying the humanities is considered useless (Smith 2016, pp. 11–14). At the same time, with the emergence of a large number of new subjects, the number of humanities students is also relatively reduced. When economic crises come, humanities are often cut first and foremost, especially in public universities (Classen 2020b; Hutner and Mohamed 2013). The latest example is the University of Kansas, which has decided to cut its humanities program entirely due to financial restraints and low enrollment (Moody 2022). Moreover, as the cost of education rises, the humanities receive less and less help, and parents and education administrators are forced to support more practical and vocational positions and courses (Ferrall 2011). These statistics indicate that the number of students studying the traditional arts is getting increasingly smaller. According to a survey conducted by the Association of Departments of English Ad Hoc Committee on the English Major in 2016–2017, the problem is alarmingly circular, for as a result of the decrease in the number of students, these departments feel more pressure, and the administrative emphasis and support for the humanities in schools gets reduced (Association of Departments of English 2018).

Both academics and the general public should be concerned with the decline of the humanities in higher education. To the extent that his change has larger societal implications, we can ask what type of human is now being created in place of the kind that was once molded by a humanistic general education? As is widely acknowledged, the prestige and practical effectiveness of science overshadows the humanities today (Deneen 2010; Konnikova 2012; Issit 2015). A technologically and economically skilled operative seems to be supplanting the broadly educated and scholarly trained human of collegiate experience. A scientistic-oriented humanoid dedicated to positivity and utility appears preferable to a civic-minded academic grounded in the somewhat more subjectively-laden disciplines of humanist inspiration. As Stanley Fish has argued, “You can talk...about ‘well-rounded citizens,’ but that ideal belongs to an earlier period, when the ability to refer knowledgeably to Shakespeare or Gibbon or the Thirty years’ War had some cash value (the sociologists call it cultural capital). Nowadays, larding your conversations with small bits of erudition is more likely to irritate than to win friends and influence people” (Fish 2015). The developing field of the Digital Humanities has been one response to the changes that science has brought to the academy. Some, like Matthew Kirschenbaum, see this new technology-oriented field as a positive move (Kirschenbaum 2012). Others, on the other hand, feel like catering to the methods and means of science is just a way for the humanities to “confer some sort of missing legitimacy in our computerized, digitized, number-happy world” (Konnikova 2012).

This does not mean that American society does not need the humanities. On the contrary, many influential people in high-tech circles have put forward the importance of cultivating the humanities with respect to the development of science and technology. A number of CEOs and professionals in the tech world retain a strong background in the humanities and liberal arts, such as Alibaba’s Jack Ma (English), the founder of LinkedIn Reid Hoffman (Oxford University, philosophy), PayPal founder Peter Thiel (philosophy and law at Stanford), Palantir Associate Founder CEO Alex Karp (neoclassical social theory and law), Pinterest founder Ben Silberman (political studies at Yale University), former HP CEO Carly Fiorina (medieval history and philosophy at Stanford), YouTube CEO Susan Wojcicki (history and literature at Harvard University), and others. Knowledge of the humanities, together with their deep understanding of technological progress, aided in their commercial success. This is because technology is rooted in people’s needs. Only when we know people well is it possible to turn technology into useful applications. It is a utilitarian realization foreshadowed in Michael Bèrubè’s influential article “The Utility of the Arts and Humanities”, where he argues that while science and technology help us know how things work:

when it comes to grappling with the larger social process by which cultural meanings are challenged and established, the tenuous understanding of what a ‘meaning’ is, our endless debates over specific attributions of meaning, over our methods of interpretation and our interpretations themselves, our struggles to grasp how things mean as well as what they mean—this is where the Humanities are uniquely useful.(Bèrubè 2003, p. 37)

Recently, American intellectuals concerned about the declining trend of the humanities have come to re-evaluate the importance of “soft” skills with respect to the needs of the employment market (Aubry 2017; Jackson 2017; Chriss 2018; Shappley 2019). A growing awareness has emerged that business majors are learning some of the technical skills needed to obtain employment “without having made the gains in writing or critical-thinking skills they’ll require to succeed over the course of their careers, or to adapt as their technical skills become outdated and the nature of the opportunities they have shifts over time” (Appelbaum 2016). This observation pertains to corporate leadership as much as it does to middle management and entry-level business people. Christian Madsbjerg argues that a rigorous and sustained engagement with cultural knowledge is critical to succeed in today’s data-driven world: “I don’t mean market research numbers or data analytics. I mean a study of culture that involves the humanities: reading a culture’s seminal texts, understanding its languages, getting a first-hand feeling for how its people live” (Madsbjerg 2017, p. 4). We argue, as techno-optimists, that the humanities provide an essential element for us to adapt to technological progress and respond to future challenges (Roth 2014, p. 11). As Lief Weatherby, states, “The core competencies of the humanities are the analysis of representational forms and the systemic critique of the meanings and values at least implicitly embedded in those forms. The study of data, as sign and infrastructure, combines these vocations” (Weatherby 2020, p. 88).

Moreover, with the development of high technology and the Fourth Industrial Revolution (which entails the development of advanced technologies such as AI, robotics, internet technologies, and genetics), people are becoming increasingly heterogeneous. At the same time, as a greater swath of the global population become exposed to other cultures and ideas via the Internet, there is now a commensurate increase in the desire for human knowledge. Working hours are changing too. With the expansion of high technology, and as the development of artificial intelligence continues, there will be greater number of people with leisure time as they become liberated from the confines of boring or tedious work. As a result, earlier retirements can take place. Society may even provide universal basic wage guarantees. These forces and others will create an increasing need for ways of spending free time and generate a desire for knowledge of the arts and humanities, which will foster a growth curve in these fields (Hartley 2017). As Klaus Schwab writes, “Human needs and desires are infinite, so the process of supplying them should also be infinite” (Schwab 2017, p. 37). The trend in institutions offering online Buddhism courses is a positive step in this new environment (Ratner 2016).

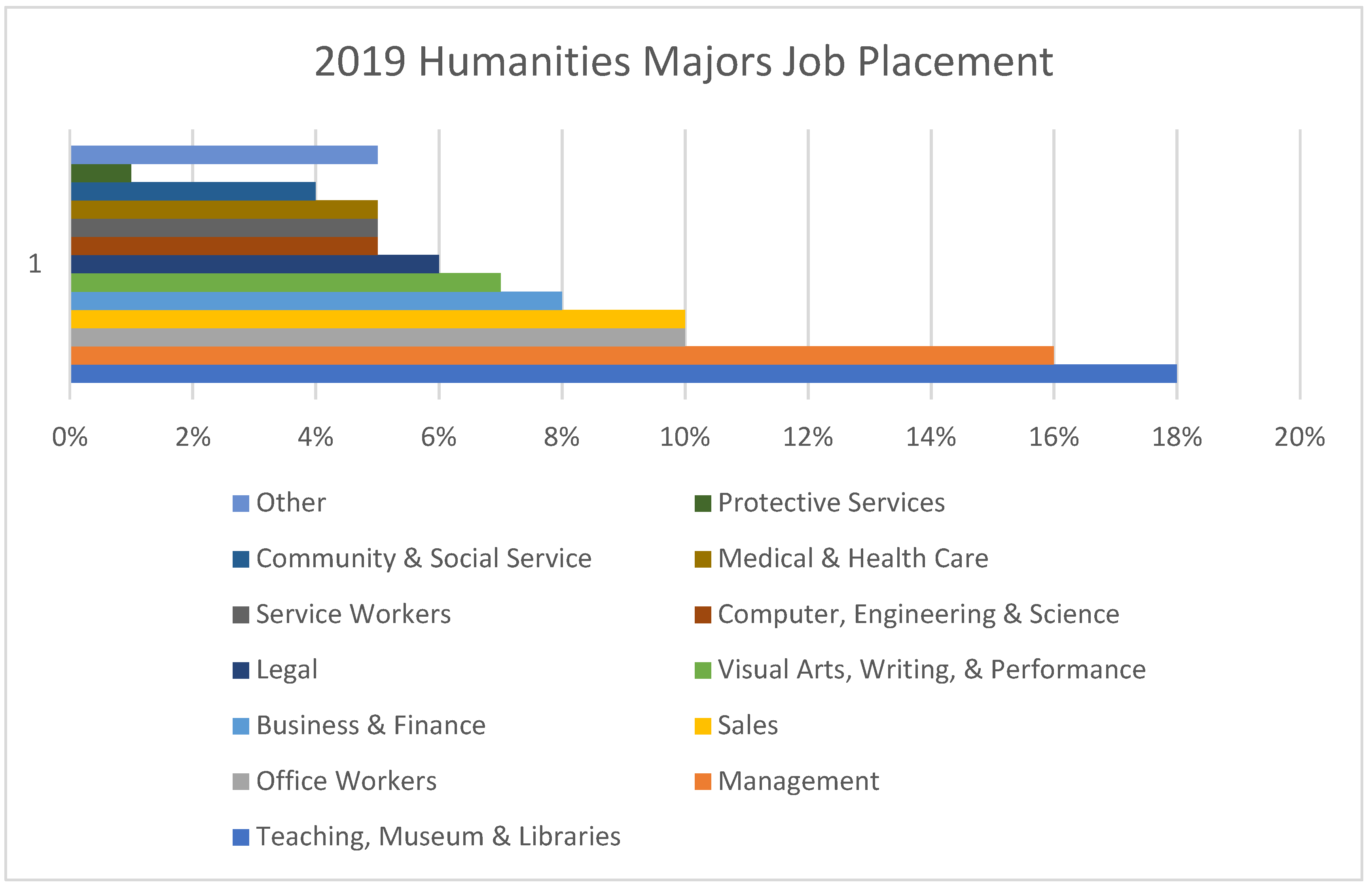

The upshot of the above discussion is that a new outlook or strategy is needed in the American university’s educational system as it pertains to the humanities. We argue that the humanities should not look back to the past, but as Sidonie Smith argues as well, be brave enough to face the future of the scientific and technological revolution. This puts humanities students within the progressive curve of present and future employment opportunities. Surveys from sources such as the World Economic Forum and the National Association of University Leaders’ Report on Employment Prospects 2017 (National Association of Colleges and Employers 2017) underscore these assertions. These studies indicate that employers today have at last used the skills taught in the humanities as a requirement for hiring, such as leadership, communication, cooperation, critical thinking, professional ethics, and problem-solving. In fact, the prospects for college graduates with degrees in the humanities are not as bleak as they once were. For example, a recent survey of 700,000 people in humanities departments in the United States showed that 18 percent worked in education, museums and libraries, 16 percent in management, of whom 135,000 were education administrators, 129,000 worked as marketing and sales managers, 107,000 were CEOs or legislators, 10 percent worked in sales, and 10 percent worked in office clerks. There have been further changes in the composition of the American population, as ethnic minorities, seniors, and female university students have shown great interest in the humanities (Humanities Indicators Project 2018) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Source: https://www.amacad.org/sites/default/files/media/document/2019-11/Humanities-in-Our-Lives_Workforce_2019.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2022).

To be clear, such a forward-looking approach for the humanities does not eschew the past as such, where the preponderance of humanistic subject matters is centered, but understands that a future informed by the humanities is advantageous to society. “In fact, historical knowledge, ideas, and values play a much larger role in culture, identity, value formation, and character than many stakeholders today are willing to admit” (Classen 2020a). In this paradigm shift, religion—particularly Buddhism—has the opportunity to play a substantive role.

5. Why Religion, Buddhism?

Having established the history, role, and present state of the humanities in higher education and society in general, the question remains what to do about it. It is a perennial one. As Patrick Deneen asked self-reflexively of the discipline, “Could an approach based on culture and tradition remain relevant in an age that valued, above all, innovation and progress?” (Deneen 2010, p. 64). If the humanities can contribute substantively to today’s technological data-driven world of commerce, then which subjects are best suited to do so? Harvard University’s example of incorporating religion into its general education reforms—together with its inclusion of Buddhist/foreign culture courses—offers one important example in this regard. To be sure, the subject of religion was not substantively included in the historical tradition of Western humanistic education. Nevertheless, scholars have been systematically discussing the position of religion in general education since the mid-twentieth century (Harner 1945). As a result, religion has become an indispensable subject in American humanities education, and has emerged as a discrete field of inquiry. But, can it exist productively with science and society today?

With the ever-growing acknowledgement of the pluralistic society of America, particularly since the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, religious education has become especially important (Eck 2015, p. 54). This is because religion spreads across the breadth and width of human survival and experience, providing the ideological basis and materials for pluralistic reflection. Future leaders in the U.S. must have basic religious education and the ability to handle religious affairs as they contribute to the development of religious and cultural dialogues. The inclusion of religious courses has added new content to humanities education because of its comprehensiveness and interdisciplinary nature. The academic study of religion presents an important opportunity to train students in personal, social, and cultural introspection. It develops students’ ability to think rationally in discussing religious and social issues in the public sphere, and to understand the diversity and pluralism of the world viz. the religious dimensions of society. Because of the global and international nature of religion, religious courses are exceptionally relevant in the current globalization upsurge. As Miroslav Volf has succinctly stated, “world religions are part of the dynamics of globalization—they are, in a sense, the original globalizers” (emphasis added, Volf 2015, p. 1). According to the American Academy of Religion’s Religious Literacy Guidelines, religion’s influence “remains potent in the 21st century in spite of predictions that religious influences would steadily decline with the rise of secular democracies and continuing advances in science” (American Academy of Religion 2019). Therefore, religion in the United States is not only one of the humanities and social science disciplines, but also a critical aspect of public discourse.

Yet, to be clear, we are not claiming that religion, or Buddhist Studies courses in particular, are a panacea in helping increase the contemporary profile of the humanities. Instead, we believe that they are an important part of a broader shift in general education. This is consistent with Martha Nussbaum’s “citizen of the world” view of imparting broad cultural knowledge in liberal education. She maintains, as we do, that religion is an important element in formulating a global citizen. For Nussbaum, “Responsible citizenship requires, however, a lot more: the ability to assess historical evidence, to use and think critically about economic principles, to assess accounts of social justice, to speak a foreign language, [and] to appreciate the complexities of the major world religions” (Nussbaum 2016, p. 93). We both share the view that the academic study of religion is just one part of a great humanistic thrust in liberal education. Her emphasis on developing critical thinking skills (to be used in conjunction with factual knowledge of cultural content) is also an important part of our argument.

Yet, the question remains why Buddhism should be foregrounded as a vehicle of humanities reinvigoration in today’s techno-scientific environment, as opposed to other spiritual traditions. Of course, the point of this article is not to forward an exclusionary critique of other religions viz. their value or applicability as academic disciplines to today’s techno-centric commercial society. Rather, as stated above, we forward Buddhist Studies as one avenue of approach—a compelling one, to be sure—in increasing the profile of the humanities in the contemporary world. Other religious studies disciplines may have their own ways of formulating their unique characteristics in this respect. In fact, we encourage other religious studies scholars, and the humanities overall, to approach the world today with the same innovative, techno-optimistic spirit we forward in this paper. Christianity, for instance, has a long visual art tradition, particularly Catholicism. This can be a foundation for a contemporary engagement with today’s omnipresent visual culture made possible by new media technologies. Although some in the religion are trepidatious about technology, Christian colleges nevertheless have embraced virtual technologies since their dramatic ramp up during the 1990s (Robbin 1996). Indeed, for many practitioners, “the virtual provides a space to explore new forms of religious expression that can be carried into life offline, and for them the virtual church offers a glimpse of what ‘real’ church could be like” (Horsfield and Teusner 2007, p. 291). Buddhism and its study have its own intrinsic and unique characteristics that make it an attractive addition to the general education of contemporary students, who are fully enculturated into our present-day technological society.

Yet, Buddhism is distinct from other major world religions insofar as its founding was not predicated on a theistic event. Its foundational legacy is one of rational discourse and freedom of thought, a grounding in various philosophical ideas of human existence and interaction, and its basic concern for the well-being of human life in the here and now (Rāhula 1959, pp. 2–14). The incorporation of deities and heavens occurred subsequent to the historical Buddha’s teachings, as the religion migrated and amalgamated other indigenous beliefs into its global identity. However, the religion’s inherent emphasis on intellectual discourse and at least outward affinity with modern secular thought, particularly scientific ideas (e.g., rationality, cause and effect, and the medical effects of meditation), continues to generate excitement and interest across a wide range of contemporary Western life (Verhoeven 2013, p. 107). Importantly, this seems to imply that Buddhism retains the ability to excite contemporary minds and ignite the imagination of students and scholars in a way that other religion’s have not.

Indeed, this excitement can be evidenced by how the overall awareness of Buddhism in contemporary culture has increased dramatically over the last forty years or so, including scholarly engagement with the subject (Prebish 2002). The American Academy of Religion (AAR) is the largest professional organization of scholars of religions in North America and reflects the contour of scholars, teachers, and university programs in Buddhist Studies. According to José Cabezón’s presidential address delivered at AAR’s 2020 Annual Meeting, there are more than 350 scholars teaching Buddhism in North American university programs, while there were only less than 50 in the 1970s when Buddhism was classified as a small subject in the field of religion (Cabezón 2020). From the 1990s, more specialized topics on Buddhist texts and traditions appeared in the AAR annual meeting panels, and related articles have been published more frequently in the organization’s journal, JAAR (Journal of the American Academy of Religion). Other organizations and journals now exist as well that cater to Buddhologists and area specialists.

Frank Reynolds (1930–2019) has been an important voice for those who are thinking deeply about the overall state and teaching of Buddhist Studies in higher education. Reynolds points out that the introduction of Buddhist curriculum into a liberal arts education is a post-modern reaction to Enlightenment-era rationalism, whose hegemony has substantially diminished in contemporary times. In his view, an improved Buddhist curriculum should be able to create a new paradigm that helps students develop “sympathetic understanding, the skills of critical analysis, and the skills of personal evaluation and judgment” (Reynolds 2002, p. 11). This approach seems particularly applicable to the humanities in the American university. For according to Reynolds, “These are...the very same skills that will ultimately facilitate an effective engagement in the kind of serious and rational public dialogue that is absolutely essential for the future health of a democratic society” (Reynolds 2002, p. 14). Significantly, however, not all Buddhist courses would be suitable in this vision for liberal education, “but specifically those that would be designed to convey to a wide range of students a kind of collage of very vivid impressions and insights. Assuming that...the course is well taught, these impressions and insights should constitute a responsible and compelling introduction to significant commonalities, differences, and conflicts that are characteristic of various Buddhist traditions” (Reynolds 2002, p. 9). This discursive distance is consistent with AAR’s view of religious literacy, which for them entails “the ability to discern and analyze the role of religion in personal, social, political, professional and cultural life. Religious literacy fosters the skills and knowledge that enable graduates to participate—in informed ways—in civic and community life” (American Academy of Religion 2019).

It is important to emphasize these qualifications. For we are not arguing that any one Buddhist tradition or teaching (e.g., Theravada, Mahayana, or Vajrayana) ought to be promoted via its inclusion in a general education curriculum. The religion is not a unitary belief system, and there are many forms and practices that can be understood under the broad moniker of “Buddhism”. In other words, we are not advocating that students be trained to become Buddhists. Rather, it is the academic study of the religion under discussion (hence “Buddhist Studies”). The claim here is that Buddhism’s historical and discursive character and attributes are particularly well suited as a humanistic and academic subject matter to be included in the general education curriculum of American universities. That, in the very least, there is something uniquely appealing and relevant about Buddhism as a worldview and proven system of analytical thought that makes it an attractive vehicle to help connect the humanities to today’s techno-scientific environment.

As a practical matter, we believe that Buddhist Studies courses will help students to be both critical (i.e., rational/analytical) and compassionate when discussing matters of culture and belief. This is a highly necessary skill in today’s diverse interconnected world. Compassion is a central component of Buddhist thought and shines through any curricular engagement with the topic. Other religions preach compassion to one extent or another, but not as a fundamental aspect of their doctrines as in Buddhism. Students who learn the cultural and intellectual value of compassionate intellectual engagement will be valuable humanities-centered assets in the contemporary employment market.

Furthermore, Buddhist visual culture courses are steadily increasing (e.g., at Berkeley, the University of Chicago, Rice, UC Santa Cruz, UArizona, and others.). This growth is clearly related to the religion’s rising academic profile in higher education, as referenced in AAR’s statistics above. As Buddhism continues its increased presence in the West and its social institutions, individuals who have some grounding in Buddhist imagery are able to productively navigate their interconnected cultural meanings. This can have practical benefits for those who are technologically creative (computer programmers, web designers, video artists, filmmakers, etc.), who regularly encounter non-Western cultural material. This is also true for those in fields of heightened interpersonal interaction (such as sales and marketing) insofar as it fosters a familiarity and point of human understanding with individuals from other cultures, particularly as Eastern ideas and motifs continue to proliferate in the West. Moreover, studying the humanities brings us closer to things that affirm our humanity. The virtual world(s) that now exist can decrease one’s contact with other people and sometimes insulate a person from the outside world—from their own humanity as social beings, generating feelings of loneliness and self-doubt. Unlike other religions, Buddhism explicitly asks practitioners and learners to think deeply about what it means to be a person viz. the nature of “the self” as the focal point of its belief system. Buddhist Studies therefore provides the unique opportunity for people to ground their psychological center within a humanistic framework.

Finally, with respect to other fields of investigation within Religious Studies, our argument foregrounds the unique and compelling attributes of Buddhist thought and study. We further highlight the religion’s inimitable characteristics below, as a way to expose their deep humanistic propensities. However, uniqueness and applicability are not conceived of here as superior or eliminative with respect to other Religious Studies fields. Judaism, Hinduism, Christianity etc. retain their own unique histories and traits that may or may not fit well in today’s commercial and technical modes of living. However, we concur with Jose Cabezón that the study of religion is “translocative”, inasmuch as it organically flows across borders. Indeed, “North American buddhologists continue to be influenced by the historical forces of their past, while crossing boundaries into new fields that enable novel ways of thinking and a distinctive style of scholarship all its own” (Cabezón 2020, p. 816). Thus, it is possible that Buddhist Studies can find common cause with other Religious Studies departments and work collaboratively with those who are likewise searching to cross programmatic lines in order to impact contemporary society through the rising academic profile of religion. For this and the reasons articulated above, Buddhist Studies is situated extraordinarily well to affect positive change in general education and to foster a renewed energy for the humanities.

6. Buddhist Resources for Humanities Curricula

The discussion above argues for the reinvigoration of the humanities with respect to their societal value via an increased presence of Buddhist Studies curriculum in the general education programs of American universities. Yet, the Buddhist tradition also retains the following unique resources and characteristics that further connect it synergistically to today’s humanities education, based on our observations and surveys of the field:

- A sophisticated doctrinal and philosophical system with emphasis on humanistic values: One of the most attractive aspects of the Buddhist tradition is its sophisticated doctrinal system, which is predicated on the primacy of mind and consciousness as the ontological origin of the world and various mundane human predicaments. Existential human conditions are then explained in terms of mental and psychological awareness. In association with this emphasis on mind, various meditation techniques were developed in both the Theravada and Mahayana traditions, assimilating indigenous philosophical ideas and creating new variations such as Abhidharm, Madhyamika, Yogacara, Vajrayana, Chan/Zen, Dzogchen, etc. Their nuanced intellectualizations have compelled modern philosophers to study them in light of new inspirations from existentialism, phenomenology, analytical philosophy, psychoanalysis, etc. (Emmanuel 2013; Williams 2009).

- Intersections with global history and geography: The history of Buddhism has been tied closely with the rise and expansion of major Asian empires and civilization: its promotion by King Asoka’s Maurya Dynasty, Kanishka’s Kushan Empire, the various Thai and Burman Dynasties, the Chinese nomad regimes and the great Tang dynasty, Prince Shotoku’s medieval Japan, and Songsten Gampo and Trisong Detsen’s Tibetan Empire in the seventh century. The geographical and historical presence of Buddhism in world history has generated excellent scholarship in academia and will continue to provide foundations for research and instruction (Robinson 1996).

- Linguistic and philological values of Buddhist texts: Buddhist ideas and history are well-documented and preserved in the Buddhist canons (commonly called the Tripitaka) and their ancillary compilations in various indigenous languages. The total amount of these written texts and documents may well exceed 2 million printed pages and can easily supply the content of a small library. Because of its nature as the accumulative collections of ancient texts in various historical languages, its linguistic and philological values are extremely high for reconstructing lost languages and histories, such as in the Gandhara area in Central Asia (Salomon 2018).

- Artistic value in painting, calligraphy, architecture, and sculpture: Many people in modern times are first attracted to Buddhism and Buddhist Studies by its visual presentation in arts. As a devotional effort, monasteries and communities have been decorated with colorful murals and statues housed in splendid monastic architecture. Out of spiritual inspiration, individual Buddhist artists created highly sophisticated artwork such as the Zen calligraphy and paintings in East Asia. Many renowned Western museums such as the British Museum, the Guimet Museum in France, and the Metropolitan Museum in New York retain Buddhist art and treasures as part of their permeant collections, which have been made largely available online during the pandemic. These visual resources create excellent teaching tools for Buddhist-related courses (Chicarelli 2004).

- Openness to Science, Medicine, and Technology: Buddhism has been seen by many in the West since the nineteenth century as “the religion of science”, uniquely compatible with modern life (McMahan 2004, p. 898; Verhoeven 2013). This view, though tainted with the popular Western imagination of Buddhism, speaks to an interesting combination and complicated history of Buddhism with science, medicine, and technology. In the Buddhist definition of knowledge, secular areas of study such as logic, cosmology, astrology, medicinal expertise, and physiology have their proper places and Buddhist monks are encouraged to master them. In association with the dissemination of Buddhism and accumulated merits, technologies such as printing were developed in China and greatly facilitated civilizational growth in the world. In the digital age, Buddhist Studies is one of the few pioneering fields that started projects such as Collections of Electronic Buddhist Text Association (CBETA) in Taiwan and the SAT Daizōkyō Text Database in Japan to digitize the entire Chinese Buddhist canon (Wu and Wilkinson 2017). Along with the rise of the Digital Humanities, these projects are moving to more sophisticated data processing techniques such as AI and deep learning (Veidlinger 2019). It is notable that in recent years, inspired by the Buddhist explanation of mind and consciousness, neuro-scientists are extremely interested in Buddhism and more research is expected to be conducted in the fields of consciousness studies and wellness studies (Lopez 2009).

- Encounters with Western culture and society: Buddhism has undergone several cultural appropriations in its encounters with major world cultures, such as the Chinese civilization. Its recent dissemination in the Western world offers another example of how complex societies reacted to the introduction of a foreign religion and assimilated with its characteristics. So far, Buddhism in the West has been deeply involved in the transformation of Western culture since the 1960s, resulting in a unique Western configuration of spirituality emphasizing contemplative practices such as meditation and active engagement in peace, democratic, environmental, human rights and social justice movements. Firmly established as a Western tradition now, this potential new Buddhist “vehicle”, provides plenty of source materials for curricula on contemporary Western culture and society, deepening students’ awareness of the evolution of Western civilization in a global context (Fields 1992).

- Buddhism as a living tradition: In addition to the Western type of New Buddhism, traditional Buddhist beliefs and practices continue to influence people in and outside of Asia. Their persistence has attracted many sociologists, anthropologists, and ethnographers to conduct in-depth field work in Buddhist communities, such as Melfred Spiro’s study in Burma (Spiro 1982). These documentations and reports, adding another dimension to our existing knowledge based on textual and historical studies, have become a significant source for building a robust curriculum.

Finally, it is important to make another distinction with respect to the academic and pedagogical engagement of Buddhism in American higher education. When discussing Buddhism in the American university, we have been referring to secular public and private institutions. Yet, there are a number of state-accredited, religiously inspired Buddhist universities that have emerged over the last decades, such as the University of the West (Taiwanese Buddhism), Dharma Realm Buddhist University (Chinese Buddhism), Naropa University (Tibetan Buddhism), and Soka University of America (Japanese Soka Gakkai) (Storch 2015, p. vii). These Buddhist-based institutions offer courses in the humanities as well as liberal arts degrees. For example, the University of the West, located just outside Los Angeles, offers general education courses that:

... reflect [its] conviction that the higher education of the whole person requires a breadth of knowledge beyond the specialized study and training covered in the majors. University of the West’s General Education courses empower students to design their own lives, their personal philosophies, their unique ways of being in this world. As they move through their GE coursework, our students explore their inner selves and learn how to face challenges, to make decisions, and to adapt in a rapidly changing world.(University of the West 2018–2019, p. 180)

These goals are consistent with those of the countless public university general education programs throughout the nation. Indeed, they embody the sort of skills that Buddhist Studies can offer the modern world that we argue for here. According to Tanya Storch, a recently retired professor of Religious Studies at the University of the Pacific, the ongoing success of Buddhist universities such as these stems from a growing cynicism and fear that traditional higher education as a whole is in crisis and heading in the wrong direction, pointing to research polls and surveys of college administrators (Storch 2015, p. viii). Nevertheless, secular public and private universities, given their ubiquity and legitimation in the American economic, social, and institutional fabric of society—something that is not the case at present with such Buddhist universities—remain the best avenue of approach in strengthening the humanities in higher education.

7. Conclusions

To close, we believe that increasing the presence of Buddhism-related courses in the general education of American universities can be a dynamic and essential component in a reinvigorated humanities. This entails maintaining a future-oriented attitude that continues to foster cooperation with various other units in the university and the world. Technologies and the world have changed greatly in the last half century or so. Higher education must likewise embrace this change, and seek alternative methods for maximizing its impact on future society. Increasing the profile of Buddhist curriculum in general education can be one way to do so. This requires us to overcome the confines of traditional religious study and to develop an education system that takes full advantage of the skills that Buddhist Studies offer students. One way to achieve these goals is to increase the number and scope of Buddhist research centers as distribution hubs of Buddhist knowledge, and encourage them to make full use of virtual and communication technologies.

The University of Arizona and its recently established Center for Buddhist Studies offers an example of what a forward-looking, technophilic approach to general education and the humanities might look like. Like Harvard, UArizona has taken a serious look at its general education program, with the dual understanding that its curriculum is both intrinsically important and pragmatically necessary in today’s global environment. Like the business world, the university recognizes that the humanities provide skills that are desirable and highly needed for individuals and companies to succeed as the Fourth Industrial Revolution continues. The university recently embarked on a “General Education Refresh”, in which humanities courses play a substantial role in fostering critical, innovative, interdisciplinary thinkers. The reform incorporates the viewpoints of the humanist and natural scientist, as well as emphasizing quantitative reasoning and world cultures, which encourages learners to think and experience life from a multiplicity of perspectives. Students gain important abilities in “communication, showing empathy, critical thinking, and working together to solve problems” (General Education Refresh 2021). These institutional reforms underscore the significance of integrating scientific and humanistic proficiencies in today’s society. As these are consistent with those skills that the study of Buddhism can provide, the importance of incorporating Buddhist curriculum into the general education of students becomes even more apparent.

Similarly, the UArizona College of Humanities (COH) recently carried out steps to cope with the decline of the humanities in a major effort to address the needs of students today. The COH created three new units within the last few years: the Department of Public and Applied Humanities, the Center for Digital Humanities, and the Center for Buddhist Studies (CBS). The last of these is a key element of this enterprise. With respect to general education, its faculty now offer (as of 2021) gen ed courses such as “North American Buddhism: Transmission, Translation, and Transformation”, which critically explores what “American” Buddhism entails and how it differs from Asian Buddhism. Indeed, working closely with these newly formed units situates the CBS as a forward-leaning center through an earnest engagement with new technologies and scientific research. Other collaborative and curricular partners include the Department of East Asian Studies, the Department of Religious Studies and Classics, the Confluence Center, the Andrew Weil Center for Integrative Medicine, the colleges of Public Health and Medicine, and the Center for Consciousness Studies. In addition, the CBS and East Asian Studies launched a study on Buddhism in the Hangzhou region of China, which combines scientific research, teaching, and outreach activities with digital technology such as GIS and virtual reality. These combined professional, technological, and pedagogical efforts demonstrate how Buddhist Studies centers can implement various activities in support of the large-scale goals of the college and university. They directly engage critical thinking, public discourse, cultural engagement, technological change, and evaluation and judgement.

In conclusion, it is hard to escape the fascinating and somewhat dichotomous notion that the way forward for the humanities and the American university entails a deeper engagement with the study of an ancient tradition. Nevertheless, as Albrecht Classen believes, “the Humanities are all about hope, which is anchored in the past and reaches out to the future... probing what the many different voices past and present have to say and how they resonate with our own ideals and needs” (Classen 2014, pp. 12–13). Indeed, we argue for a fearless and visionary disposition in this regard, remembering the axis that connects the past, present, and future is that of the human being. The humanities are thus essential to our success as a modern technological society.

Author Contributions

J.W. provided the concept and proposal, initial text, data figures, and curricular resource observations (Section 6). R.E.G. provided scholarly research, argumentative structure, and additional content throughout. Total academic effort is 50/50. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 2021. National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) Funding Levels. Available online: https://www.amacad.org/humanities-indicators/funding-and-research/national-endowment-humanities-neh-funding-levels (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- American Academy of Religion. 2019. AAR Religious Literacy Guidelines: What U.S. College Graduates Need to Understand about Religion. Available online: https://www.aarweb.org/AARMBR/Publications-and-News-/Guides-and-Best-Practices-/Teaching-and-Learning-/AAR-Religious-Literacy-Guidelines.aspx?WebsiteKey=61d76dfc-e7fe-4820-a0ca-1f792d24c06e (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Appelbaum, Yoni. 2016. Why America’s Business Majors Are in Desperate Need of a Liberal-Arts Education. The Atlantic. June 28. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2016/06/why-americas-business-majors-are-in-desperate-need-of-a-liberal-arts-education/489209/ (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Association of Departments of English. 2018. A Changing Major: The Report of the 2016–2017 ADE Ad Hoc Committee on the English Major. Available online: https://www.ade.mla.org/content/download/98513/2276619/A-Changing-Major.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Aubry, Timothy. 2017. Don’t Panic, Liberal Arts Majors. The Tech World Wants You. The New York Times. August 21. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/21/books/review/you-can-do-anything-george-anders-liberal-arts-education.html (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Bèrubè, Michael. 2003. The Utility of the Arts and Humanities. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 2: 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Bèrubè, Michael. 2013. The Humanities, Declining? Not According to the Numbers. The Chronicle of Higher Education: The Review. July 1. Available online: https://www.chronicle.com/article/the-humanities-declining-not-according-to-the-numbers (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Bèrubè, Michael, and Jennifer Ruth. 2016. The Humanities, Higher Education, and Academic Freedom: Three Necessary Arguments—A Forum. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 15: 209–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bok, Derek Curtis. 1982. Beyond the Ivory Tower: Social Responsibilities of the Modern University. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, William G., Alvin B. Kernan, and Harold T. Shapiro. 2014. What’s Happened to the Humanities? Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cabezón, José I. 2020. AAR Presidential Address: The Study of Buddhism and the AAR. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 89: 793–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicarelli, Charles F. 2004. Buddhist Art: An Illustrated Introduction. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. [Google Scholar]

- Chriss, Alex. 2018. Don’t Ditch that Liberal Arts Degree. US News World Report. January 19. Available online: https://www.usnews.com/opinion/knowledge-bank/articles/2018-01-19/in-this-digital-age-students-with-liberal-arts-training-stand-out (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Classen, Albrecht. 2014. The Challenges of the Humanities, Past, Present, and Future: Why the Middle Ages Mean So Much for Us Today and Tomorrow. Humanities 3: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Classen, Albrecht. 2020a. The Amazon Rainforest of Pre-Modern Literature: Ethics, Values, and Ideals from the Past for Our Future. With a Focus on Aristotle and Heinrich Kaufringer. Humanities 9: 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Classen, Albrecht. 2020b. Reflections on Key Issues in Human Life: Gottfried von Strassburg’s Tristan, Dante’s Divina Commedia, Boccaccio’s Decameron, Michael Ende’s Momo, and Fatih Akın’s Soul Kitchen—Manifesto in Support of the Humanities—What Truly Matters in the End? Humanities 9: 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuypers, Stefaan E. 2018. The Existential Concern of The Humanities: R.S. Peters’ Justification of Liberal Education. Educational Philosophy and Theory 50: 702–11. [Google Scholar]

- Cvejić, Žarko, Andrija Filipović, and Ana Petrov. 2016. The Crisis in the Humanities. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong, Jan Willem. 1985. A Brief History of Buddhist Studies in Europe and America. Delhi: Sri Satguru Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Deneen, Patrick J. 2010. Science and the Decline of the Liberal Arts. The New Atlantis 26: 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Eck, Diana. 2015. Pluralism: Problems and Promise. Journal of Interreligious Studies 17: 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Emmanuel, Steven M. 2013. A Companion to Buddhist Philosophy. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrall, Victor E. 2011. Liberal Arts at the Brink. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fields, Rick. 1992. How the Swans Came to the Lake: A Narrative History of Buddhism in America. Boston: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Fish, Stanley. 2015. Will the Humanities Save Us? In Think Again: Contrarian Reflections on Life, Culture, Politics, Religion, Law, and Education. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Flannery, Christopher, and Rae Wineland Newstad. 1998. The Classical Liberal Arts Tradition. In Liberal Arts in Higher Education: Challenging Assumptions, Exploring Possibilities. Edited by Diana Glyer and David L. Weeks. Lanham: University Press of America. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, Roger L. 2015. From the Land-Grant Tradition to the Current Crisis in the Humanities. In A New Deal for the Humanities: Liberal Arts and the Future of Public Higher Education. Edited by Gordon Hutner and Feisal G. Mohamed. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, pp. 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- General Education Refresh. 2021. The University of Arizona, General Education Office. Available online: https://provost.arizona.edu/content/general-education-refresh (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Graham, William A. 1978. Rethinking General Education at Harvard: A Humanistic Perspective. In The Humanities: A Role for a New Era: A Colloquium. Santa Barbara: Educational Futures International, pp. 58–72. [Google Scholar]

- Harner, Nevin Cowger. 1945. Religion’s Place in General Education. Richmond: John Knox Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, Scott Hartley. 2017. The Fuzzy and the Techie: Why the Liberal Arts Will Rule the Digital World. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Harvard College Program in General Education. 2021. Available online: https://gened.fas.harvard.edu (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Harvard University. 1945. General Education in a Free Society: Report of the Harvard Committee. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hollywood, Amy. 2011. On Understanding Everything: General Education, Liberal Education, and the Study of Religion. PMLA 126: 460–66. [Google Scholar]

- Horsfield, Peter, and Paul Teusner. 2007. A Mediated Religion: Historical Perspectives on Christianity and the Internet. Studies in World Christianity 13: 278–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Kunjin. 2006. General Education in American Universities: Climbing the American Mind. Beijing: Peking University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Humanities Indicators Project. 2018. The Humanities in Our Lives. American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Available online: https://www.amacad.org/publication/humanities-in-our-lives (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Hutner, Gordon, and Feisal G. Mohamed. 2013. The Real Humanities Crisis is Happening at Public Universities. The New Republic, September 6. [Google Scholar]

- Issit, Micah L. 2015. The E-volution of Education and Thought. In The Reference Shelf: The Digital Age. Pasadena: Salem Press, pp. 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Abby. 2017. Mark Cuban: Don’t Go to School for Finance, Liberal Arts is the Future. Business Insider. February 17. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/mark-cuban-liberal-arts-is-the-future-2017-2 (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Kernan, Alvin B. 1997. What’s Happened to the Humanities? Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kimball, Bruce A. 2010. The Liberal Arts Tradition: A Documentary History. Lanham: The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschenbaum, Matthew. 2012. What Is Digital Humanities and What’s It Doing in English Departments? In The Digital Humanities. Edited by Matthew K. Gold and Content Provider. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota. [Google Scholar]

- Konnikova, Maria. 2012. Humanities Aren’t a Science. Stop Treating Them Like One. Scientific American. Available online: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/literally-psyched/humanities-arent-a-science-stop-treating-them-like-one/# (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Li, Silong. 2009. The History of European and American Buddhism: The Image of Buddhism in the West and Its Source. Beijing: Beijing University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, Donald. 2009. Buddhism and Science: A Guide for the Perplexed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Madsbjerg, Christian. 2017. Sensemaking: The Power of the Humanities in the Age of Algorithm. New York: Hachette Books. [Google Scholar]

- McMahan, David L. 2004. Modernity and the Early Discourse of Scientific Buddhism. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 72: 897–933. [Google Scholar]

- Moody, Josh. 2022. University of Kansas Looks to Cut 42 Academic Programs. Inside Higher Ed. February 18. Available online: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2022/02/18/university-kansas-plans-cut-42-academic-programs (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- National Association of Colleges and Employers. 2017. Job Outlook. Available online: https://www.naceweb.org/store/2017/job-outlook-2017/ (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Nussbaum, Martha C. 2016. Not for Profit: Why Democracy Needs the Humanities, new paperback ed. Princeton: Public Square. [Google Scholar]

- Prebish, Charles S. 2002. Buddhist Studies in the Academy: History and Analysis. In Teaching Buddhism in the West: From the Wheel to the Web. Edited by Victor Sogen Hori, Richard P. Hayes and James Mark Shields. London: Routledge, pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rāhula, Walpola. 1959. What the Buddha Taught. New York: Grove Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ratner, Paul. 2016. Harvard Has a Free Online Course on Buddhism That You Can Take Right Now. Big Think. December 4. Available online: https://bigthink.com/paul-ratner/want-to-learn-more-about-buddhism-take-this-free-online-course-from-harvard-university (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Reynolds, Frank. 2002. Teaching Buddhism in the Postmodern University: Understanding, Critique, Evaluation. In Teaching Buddhism in the West: From the Wheel to the Web. Edited by Victor Sogen Hori, Richard P. Hayes and James Mark Shields. London: Routledge, pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Robbin, Katherine L. 1996. Modern technology: A quantum leap forward on today’s Christian college campuses. Christianity Today 40: 60. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Richard. 1996. The Buddhist Religion: A Historical Introduction, 4th ed. Belmont: Wadsworth Pub. Co. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal-Pubul, Alexander S. 2018. The Contemporary Crisis of the Humanities: The Attack on the Western Canon and The Long Arm of Nietzsche, Marx, and Foucault. In The Theoretic Life—A Classical Ideal and Its Modern Fate: Reflections on the Liberal Arts. New York, Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 145–51. Available online: https://doi-org.ezproxy1.library.arizona.edu/10.1007/978-3-030-02281-5_16 (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Roth, Michael S. 2014. Beyond the University: Why Liberal Education Matters. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salomon, Richard. 2018. The Buddhist Literature of Ancient Gandhāra: An Introduction with Selected Translations. Somerville: Wisdom Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, Klaus. 2017. The Fourth Industrial Revolution. Cologny: World Economic Forum. [Google Scholar]

- Shappley, Jennifer. 2019. LinkedIn Research Reveals the Value of Soft Skills. Fast Company. January 19. Available online: https://www.fastcompany.com/90298828/linkedin-research-reveals-the-value-of-soft-skills (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Shen, Wenqin. 2010. Liberal Arts and Humanities: A Survey of Conceptual History. Comparative Education Research 32: 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Shephard, Jennifer, Evelynn Hammonds, and Stephen Kosslyn. 2011. The Harvard Sampler: Liberal Education for the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Sidonie. 2016. Manifesto for the Humanities: Transforming Doctoral Education in Good Enough Times. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, Vicki. 2014. Democratic Citizenship and the ‘Crisis in Humanities’. Humanities 3: 398–414. [Google Scholar]

- Spiro, Melfred. 1982. Buddhism and Society: A Great Tradition and Its Burmese Vicissitudes. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Storch, Tanya. 2015. Buddhist-Based Universities in the United States: Searching for a New Model in Higher Education. Lexington: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Stover, Justin. 2017. There is No Case for the Humanities. American Affairs 1: 210–24. [Google Scholar]

- Task Force on General Education. 2006. Preliminary Report: Task Force on General Education. Cambridge: Harvard University. [Google Scholar]

- Task Force on General Education. 2007. Report of the Task Force on General Education. Cambridge: Harvard University. [Google Scholar]

- University of Chicago. 1950. The Idea and Practice of General Education: An Account of the College of the University of Chicago. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- University of the West. 2018–2019. General Education Catalog. Available online: https://www.uwest.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/UWest_Academic_Catalog_2018-2019_18-General_Education.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Veidlinger, Daniel, ed. 2019. Digital Humanities and Buddhism. Berlin and Boston: Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven, Martin J. 2013. Science, Technology, and Religion VI: Science through Buddhist Eyes. The New Atlantis 39: 107–18. [Google Scholar]

- Volf, Miroslav. 2015. Flourishing: Why We Need Religion in a Globalized World. London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, David L. 1983. The Seven Liberal Arts in the Middle Ages. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weatherby, Lief. 2020. Data and the Task of the Humanities. The Hedgehog Review 22: 86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Ralph. 2016. Representing Tradition: An Analysis of Tu Weiming’s Confucianism. International Communication of Chinese Culture 3: 229–60. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Paul. 2009. Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations, 2nd ed. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Jiang, and Greg Wilkinson. 2017. Reinventing the Tripitaka: Transformation of the Buddhist Canon in Modern East Asia. Lanham: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).