Abstract

In this paper, we will analyse how Xesús Fraga’s novel Virtudes (e misterios) (2020) and María Ruido’s audiovisual project The inner memory (2002), by creating memory and post-memory of Galician emigration in the 1960s and 1970s, reconfigure the symbolic image of the Galician nation, which has always been defined on the basis of the discourse of mobility and emigration. Both authors, from the fragmentation of intimate memories and through an ambiguous pact with the reader, between the documentary and the fictional, bring us the stories of emigrant women—narratives in which identities are inevitably hybrid, fragmentary and far removed from homesickness as a defining factor of the Galician identity. Emigrant women do not fit into the hieratical traditional identity, which marginalises them because they do not fit the archetype of ‘widows of the living’.

1. Introduction

É posible imaxinar unha Galicia sen fronteiras, confluencia de culturas e puntode encontro, unha Galicia dinámica e viaxeira, aberta á hibridación, que encontrao seu lugar no mundo. Sería necesario construír unha nova cartografía ondeGalicia non fose periferia, unha Galicia solidaria co mundo, e sobre todo consigomesma, unha idea de Galicia posible para o século XXI.José () Galeg@ sen fronteiras

This article compares the novel Virtudes (e misterios) (Editorial Galaxia) by Xesús () with María () audio-visual project The inner memory. Both authors belong to what we might call ‘the generation of the children’ of Galicians who emigrated to Europe in the 1960s–1970s. A migratory wave of historical importance that Ruido summarises with precision:

The importance of the numbers of the Spanish emigration to some European countries such as Germany, France or Switzerland between 1959 and 1973 is well known. The conjunction of a surplus work force in Spain (and in other countries in the South) and a strong demand for unqualified workers in these countries, immersed in a period of economic growth, together with the abandonment of a restrictive migratory politics and of the so-called autarchy, resulted in an abundant flow of work force destined to Europe.

Fraga and Ruido represent two sides of the same coin. Ruido was the daughter waiting in Galicia for the return of her parents before they emigrated to Germany. Fraga was the unforeseen pregnancy of a newly married couple emigrating to London, and therefore was also an emigrant himself.

However, to Ruido’s summary, we should add two more aspects which, in our opinion, are essential:

(a) The gradual but massive incorporation of women into the migration process. Even travelling entirely alone (). A process that had much to do with the previous surplus of women to the Spanish labour market, after the scarcity of the post-war period and the National Stabilization Plan of 1959, which prohibited them from having more than one job (). Spain’s dictatorship had to acknowledge, de facto, the existence of women workers1 () and emigrants. However, a suspicion that these two processes facilitated labour abuses and, especially amongst women, a higher degree of illegal migration. In the absence of traditional channels, women followed strategies, typically based on family and friendship networks, as a means to migrate […]. (). Clearly, the incorporation of women into a hostile world of work was an emancipating factor, since it meant not only the possibility of an increase in income and potential savings, but also an increase in the awareness of their rights and needs (). However, the role given to women during Franco’s regime had not changed at all:

claro es que referido únicamente a la mujer casada, las limitaciones de Derecho, una vez más confirmado en la reforma del Código Civil en mil novecientos cincuenta y ocho, que el matrimonio exige una potestad de dirección que la naturaleza, la religión y la historia atribuyen al marido. Sigue siendo norma programática del Estado español, anunciada por la Declaración segunda del Fuero del Trabajo, la de “libertar a la mujer casada del taller y de la fábrica”. (Ley Sobre derechos políticos profesionales y de trabajo de la mujer, Ley 56 de 22 de julio 1961)2

(b) “A cuestión dos fillos, que moitas veces permanecían aquí, constitúe unha peza clave na representación cognitivo-afectiva deste colectivo”3 (). The migration waves of the 1960s and 1970s were generally a family endeavour that was focused on children:

For the first time, they have the possibility for their sons and daughters to not face the same tiring and destructive jobs that they faced. Class becomes a place one wants to abandon. And for what reason wouldn’t they want to abandon it? Why should they try again, after having swallowed so many defeats?()

Until then, the ranks of migrants had largely been swollen by young people from large farming families, who, without inheritance or land, had few prospects in Galicia’s future. However, the migratory mass towards Europe was already responding to a different kind of mentality: children were no longer seen as hands for agricultural or livestock work, but as hands for the future (). Contraceptive methods had made birth planning possible and, thus, facilitated a new family model in which children represented an economic expense, as parents sought to give them the best possible quality of life. Hence, the motivation for displacement was no longer centred around the need to increase the size of the family estate. This shift in family planning towards the ‘children’s issue’ was made possible by what Marianne (), in her study Os retornados, calls ‘Family Business’. A concept that describes the functioning within migrant families, which consisted of a reciprocal exchange of family care, in which grandparents took care of grandchildren in exchange for care in their eventual old age. This system facilitated both the migration of couples and their ability to save money quicker. Emigration was understood to be a sacrifice for the sake of their children, in order to give them a good education.

Regarding the works under consideration, there are many points that both have in common, which we will briefly outline below.

Firstly, the desire to put into practice an exercise of individual and collective memory. Ruido’s definition of The inner memory is also equally valid for Fraga’s novel:

“[…] tackles the theme of the construction of memory and of the mechanisms of the production of history. Through the narration of my family’s history, it delves into the memory of the recent emigration from the Spanish state to Europe, and reflects on the mechanisms of oblivion and remembrance, by recuperating the idea of the construction of memory as a nexus and a dialogue, and the elaboration from personal experience against the idea of an official history and memory, restricted to the institutional and articulated around the aestheticisation and the deactivation of the political subjects”

Both authors create a story from fragments of intimate memories which, nevertheless, have great collective implications, as they allow us to understand the recent past from a new perspective. But the similarity does not only lie in their intention, their narrative strategies are also the same: to establish an ambiguous pact with the reader, by placing themselves between fiction and the documentary.

However, perhaps the most obvious similarity is that they establish a dialogue with the women in their families. It is the female emigrants, mothers and grandmothers, who ultimately become the protagonists of the story and legitimate interlocutors: “All your efforts were directed at changing our future, and the changed future rose between us like an unsurpassable distance: mother,4 I will carry with pride the legacy of your little treasures to tell you that which I have never told you” (). Male actors are often left in the shadows, although sometimes, their more systematic and detailed memories allow the reconstruction of memory. Fraga acknowledges that, without his father’s precise recollections, his book would not have been possible, and Ruido’s work, it is striking that the father ends up answering many of the questions that were originally asked of the mother. Yet, the recognition is given to those women who, despite having encountered many more obstacles, did not hesitate to emigrate whilst dreaming of improving both their own education as well as that of future generations. Not only they, but they above all, had to give up many projects, and rebuild their life plan over and over again, because society was not prepared to recognize them as emigrants or as emancipated women. How could they recognize themselves in them if the essentialist identity of the nation recognized the only role of women in emigration as ‘viúdas de vivo’ (widows of the living).

Finally, another relevant topic is the return as a part of the migratory process, and the fact of not considering that the return puts an end to the emigration, because in Fraga and Ruido’s stories, hybrid identities, fragmentation, separation of family members and the feeling of foreignness prevail after coming back to the homeland:

But, at that moment, the connection between the two, the grandmother, and the city, had reached such a degree of blending that it seemed the most logical thing to me: I could not conceive of the one without the other, as if she had already been born an emigrant and as if that condition was timeless and unalterable.()

A matter that has set the topic of homesickness aside in the literary discourse.

2. Memory, Post-Memory, and Family Albums

“I have made this trip because I have the duty of memory, and the necessity to tell our history which is also the History”.()

Ruido and Fraga, like the Galician authors who have approached the Spanish Civil War without having lived it5, “asumen la función de correa de transmisión de la memoria cierta”6 (). Based on family testimonies, scraps of their own memories, a bunch of photos and some small objects that have survived the passage of time in an old suitcase or in an aunt’s brass box—with the urgency caused by the gradual disappearance of the living witnesses ()—they build the memory and post-memory7 of the Galician emigration to Europe in the 1960s and 1970s8.

Mentres eu lle daba voltas a como escribir este libro, que se unha novela cos personaxes cos nomes cambiados, que se un reconto máis achegado a non ficción […] pois chegou a vida e meu pai faleceu. Eu aí decateime que a vida non agardaba que había que espelirse, como diría a miña avoa Virtudes e tratar de escribir a historia dunha vez mellor ou peor, pero polo menos sacala a diante. Ese foi tamén un gran estímulo para min e o mesmo tempo unha mágoa que de todas as conversas que tivemos e todas as memorias que eu sabía que lle ían gustar pois non chegase a tempo para lelas porque eu estivese demasiado ocupado dándolle voltas a como contalo […] debo dicir que no proceso de recollida de información meu pai foi unha fonte valiosísima, porque el o lembraba absolutamente todo […]()9

These scattered memories and objects are built from the ruins of a past time, they are reassembled in a collage shaped by both memory and oblivion, both essential for the construction of identity, because what we forget also says a lot about ourselves, because, “¿no es cierto que un individuo dado -un individuo sometido como todos al acontecimiento y a la historia- tiene recuerdos y olvidos particulares, específicos? […] dime qué olvidas y te diré quién eres”10 ()11. At the same time, both of them keep, in a deep and affective way, memories prior to their own birth such as the family migration movements that preceded them or the social and economic circumstances that triggered said movements as well as scenes from their childhood that they were too young to remember properly, but became vivid memories through familial retellings. An archetypal example of this construction of memory is the tale of Fraga’s mother’s entry into Great Britain, when he, himself, was barely an embryo, which is an anecdote to which the author repeatedly returns to in later texts, either changing the narrative voice or hiding the biographical nature of the event. However, both authors also experience directly part of their parents’ migration process—a factor that makes it difficult to adhere only and strictly to Hirsch’s concept of post-memory, which is why we refer to both memory and post-memory to analyse the works that concern us.

On the other hand, childhood memories, both their own and those acquired, are subjected to examination and reworking from their adult perspective—“I didn’t understand then why you insisted on writing in Castilian” ()—and contrasted against the recollections of family and friends who contribute further information and other perspectives

percibía que para a avoa aquelas comuñóns eran importantes, mantiñan acesa a súa fe cristiá e supuñan un vínculo claro, mesmo se a lingua era outra, co seu lugar de orixe. O que daquela eu non sabía era que unha daquelas misas case lle salvara a vida12.()

Perhaps the most obvious comparison to the works of Fraga and Ruido are the stories from the children of ‘the disappeared’ from the time of Argentina’s dictatorship because there, as in Galicia, there are many stories in which children experienced the disappearance of their parents or were forced to live in hiding at an age that allowed them to preserve their own memories of the 1976–1983 period. Furthermore, this particular generation of Argentinian authors draw on ‘autofiction’ () and other ways in which the pact with the reader is ambiguous (), as well as utilising family documents and photo albums. However, this comparison is only relevant in a relative way, since some of these Argentinian works have a style akin to autobiography whereas others adopt an ironic, or even sarcastic, tone (; ; ; ). However, this last modulation of the narrative voice barely relates to the works we are discussing in this article. Neither Fraga’s nor Ruido’s work features critical distancing due to a misunderstanding of their parent’s migratory circumstances or resentment of a demanding childhood. In Fraga’s case, although he is aware that his grandfather’s emigration has drastically altered life for further generations, he does not fault his mother, grandmother, or great-grandmother. In the case of Ruido, reproach and doubt are expressed by questioning, but those questions are swiftly annulled by the realization that the socioeconomic situation left them no alternative.

—Well, if that had been nowadays, it would have been better not to leave, wouldn’t it?—Oh, well, if we weren’t getting paid our retirement, it is the same as before, because now we get more than two hundred thousand pesetas every month, but one year you sell the potatoes a little better, and another- last year Sindo sold 34 or 35,000 kilos at 3 pts. What is that!()

Those conditions have barely changed though there is now a shared family identity “even though I dreaded parents’ reunions at school, even though later I would resent your internalization of the firm’s paternalism and of the life at the barracks, I have always known who I was, where I came from” (). Both Ruido and Fraga narrate from a working class perspective and as heirs and apprentices to a way of life: “outro precepto que rexía a moral familiar, e cuxa autoridade lle escoitei tantas veces a miña nai atribuírlla á súa avoa—Por moi pobre que sexas, nunca lle debas nada a ninguén”13 (). Their stories are told, partly, as a debt owed to the efforts of previous generations:

It is necessary to have an attentive self-control, to avoid being the object of external control, of pity or charity: get on, don’t fall, go by yourself to the doctor, don’t get any debts, don’t ask for the impossible. And all that fear, and that rage that you have gone through. All that fear still lives inside me. Today, from my work, I think of how to make your work visible: the production of history, the history of production.()

Returning to the experiences of these authors, there are two further issues that need to be considered. The first is the fact that parental emigration does not cause the displacement of the courses of their children’s lives, at least, not in the sense of usurping their own existence, nullified by the need to advocate the memory of their parents. Fraga and Ruido speak as immigrants and, with their writing, they also try to value their history, both in the public and private senses. Fraga and Ruido speak as immigrants and, with their writing, they also try to value their history, both in the public and private senses. However, their control over the circumstances of their experiences is more than relative. For they are the main reason that compelled their parents to displace this generation of children, “the promise of happiness” ()14 that led them to leave: the desire to send them to college. The children are conditioned by that desire, by a family project that they have not chosen for themselves. Something particularly evident in both works, since Ruido clearly reflects the purpose that led his parents’ generation to emigrate: “You are the ones who turned and turned. Because it was very hard to leave, but thanks to that, these little ones were able to study” () and Fraga reflects on how not going to university would upset his mother terribly:

Ninguén da familia accedera aínda á universidade, pero confiaba caladamente en que á Escola de Idiomas lle seguise a facultade e a licenciatura que a ela as circunstancias lle negaran. Aquel primeiro título chegou cando eu fixen os dezaoito, pero cando o enmarcamos e colgamos a carón do de miña nai, eu estaba a piques de estragar o seu soño e, de paso, un futuro meu no que ela depositara tantas esperanzas e investira tanto sacrificio15.()

Nevertheless, the fact that it is a story driven or conditioned by the expectations of their parents does not prevent Fraga or Ruido from recounting their own encounter with emigration and with the trauma of return, which is also part of the physical and psychological displacement that begins with the departure, either their own or that of their parents. If we look at the emigrant not from the dichotomy of country of origin vs. host country, but from what really defines him, the movement (), we will see that this movement affects everything; families and societies. Thus, in Virtudes (e misterios), the story shows us how the emigration of the grandfather ends up conditioning the life of each and every one of the family members; as in a collapsing house of cards. In the case of Ruido, her traumatic childhood as a result of his parents’ emigration and their hard work in German factories, serves to show us how the effects of migratory biopolitics are inscribed in the bodies converted into memory because “memory is imperfect, it is selective, forgetful. Only our bodies, registered passers-by, keep the sour taste of the price of the justest dreams” (). So, either as a returned child or as a daughter who no longer knows her parents, both are affected by movement and emigration. That is why “to speak from the bodies of others” is to allude one’s own body and memory, because bodies are the only “possible spaces in which to reconstruct the history learned at university, in the monuments” ().

Another issue resulting from the inclusion of children within the migratory movement is that, although the parents sought to prevent them from having to emigrate as well, thanks to access to higher education, the structural and economic conditions of Galicia have not changed so much and emigration continues to be an option. Ruido narrates from a position of self-assumed foreignness—“today, when I get home, I feel a stranger; I am already a stranger, as a condition, as a debt” ()—and as an emigrant in Barcelona where she has been able to fully develop his career. Fraga has returned to London periodically throughout his life. The decision to stay would have been a ‘natural’ and simple step, a fact that is depicted in the novel. In addition, in his case, he publishes after the crisis of 2010, so Virtudes (e miterios) coexists on the shelves of bookstores with younger authors—from his children’s generation—who are writing about emigration from the diaspora or after having recently returned. That is to say, the emigration continues present in the adult life of these authors and in the collective narrative, not only as an effect of trauma, but as a current fact that involves each generation.

However, despite the specific characteristics that we have just pointed out, studying these two works with Hirsch’s texts as a theoretical basis proves pertinent if we consider that both works start from an intimate appropriation of their family past to build a collective, generational gaze, from which they take part in a story in which they had a passive role. Both authors intend to give historical value to the experiences of a group of which rather little has been said, especially regarding overseas emigration. A value in which, as we will see in the next section, the migrant woman acquires a main and particular representation. Moreover, works such as those written by Ruido and Fraga contribute to the way authors of the ‘nova diáspora galega’ rethink themselves, their process of emigration, the relationship with the host country, the possible return… It is a process that we can observe in particular, for example, in Eva Moreda, who before writing a novel about the current emigration and the return—a story that is not autobiographical, but that is written in a way for the reader to think it is—in 2011, she wrote A veiga é como un tempo distinto, a story set in the London’s diaspora in the 1960s and 1970s. In fact, () publicly reflects on how her vision of emigration in this period has evolved due to her own migratory experience in an article in Galicia 21. In other words, the current memory of any of the migratory waves that Galicia lives/has lived through is conditioned by others’ stories. Therefore, the memory of Galician emigration is, using () terminology, “conecctive” and that is why “el lenguaje de la familia puede convertirse en una accesible lingua franca que facilite la identificación y la proyección”16 () both within the Galician community and in general given the universality of the subject. This fact justifies and explains the use that both creators make of family photos and narratives, an artistic medium that, as Hirsch points out, has been widely used to deal with the aftermath of trauma17.

On the other hand, it is true that the trauma and catastrophic violence of the Holocaust—which served, at first, as an anchor point for Hirsch—or the Civil War are not comparable to the events narrated by Ruido and Fraga. But, emigration, as an endemic phenomenon in Galicia and a source of family fractures that constitute an inheritance and an open wound that never ceases to ooze, causes that the memories that give rise to the works studied in this article do not “strictly create a position of identity”, although there is much in them of the search for one’s own identity, “sino una estructura generacional de transmisión integrada en múltiples formas de mediación, desde las privadas e íntimas, a imágenes, mitos e historias compartidas y públicas18” (). Thus, for example, the mystery that hides the emigration of the grandfather to Venezuela, of which we know almost nothing, it is really the story of the emigrant par excellence

unha convencional historia de emigración, tan tópica que era imposible non asumir a súa verosimilitude: remendar zapatos apenas daba uns patacóns e a Venezuela dos anos cincuenta aparecíase coma unha terra prometida de prosperidade, a xulgar polo que dicían as noticias que se recibían nas casas dos que tiñan parentes naquela beira do Caribe19”.()

In other words, the lack of information about the grandfather’s stay in Venezuela is a void easy to fill with intuitive veracity, because it is a topic of the collective memory of Galician emigration. With examples like the one we have just pointed out, and again similarly to what happened with the writers who approached the Spanish Civil War without living it, it is not surprising that Ruido and Fraga insist on “impedirnos la lectura de sus novelas en clave documental, quizás por el afán de no sentirse obligados a una fidelidad factual”20 () that they cannot assume. Thus, the sentences that refer to the impossibility of approaching the story from a documentary point of view and the references to memory and forgetfulness are a constant: “Calquera intento de reproducilos aquí sería un exercicio de memoria que, coma todos, tería máis de invención que de fiabilidade, e ademais quedaría curto, moi curto”21 (), “E ninguén máis garda lembranza testemuñal dese noivado e voda. A maioría morreron, os poucos que quedan esqueceron”22 (), “[…] more than twenty years ago I was here, and now I return to speak about it, to take those images which fed this memory of oblivion: the factory is smaller than in my memories, the Bergstrasse busier, the Central Station.” (), “Pero, malia a súa transcendencia, apenas sobreviven documentos que nos poidan ofrecer unha lectura obxectiva da súa emigración”23 ().

Both authors know that they are navigating between individual and collective memory and write from responsibility and commitment to a story and circumstances with which they empathize. As per (), The inner memory is born as a result of this dichotomy and of disputing the privileged place that history has “It is banal to say that memory is a liar, it is more interesting to see in this lie a form of natural protection that can be governed and modelled. Tales of the other, of the stranger (foreigner) in me”. She leaves no room for doubt, she expresses it openly, as we can see in the introductory quote of this section. Furthermore, the work of this author, as we already pointed out in the introduction, generally revolves around the construction of memory and its relationship with the narrative forms of history or the social construction of the body and identity. Fraga, however, struggles for years with how to translate his family ties with London emigration into literature. In fact, the author of Virtudes (e misterios) in AZ (), who also talks about emigrating to London, hesitated in using autobiographical elements. In the first pages of this book of stories, we find a photograph of the family record book, in which he is registered as born in London on 28 February 1971, and the first story is nothing more than a childhood memory that shows how family and daily experiences of the author are inseparable from the migratory fact. Therefore, if the aldea is the small town where the grandparents live and where their classmates go every weekend and on vacation, he also has a village: his village is London. That is where he spends his holidays, it is there where his grandmother lives, and his adventures with her are not very different from those of the others. However, the author goes back and leads us towards the fictional, cancelling the biographical elements with a phrase such as “nese Londres ben puideron acontecer as historias deste libro. Ou ben imaxinalas”24. () In addition, although the main content of AZ is an accumulation of stories and anecdotes that have in common the city of London to which the title refers and that are carried out by immigrants and visitors to the city on the Thames, over an extensive period of time, they do not seem to have a specific connection to either the author or the narrator. In fact, in the translation of AZ into Spanish, he removes the photograph, he replaces the childhood memories in the first person with a description of the registry of an immigrant on the border “to avoid that with that new life a new life is smuggled” () and introduces a significant change in the title that becomes AZ Emigrados en Londres (), which connotes with more intensity the idea of polyphonic narration. With this, it goes from what, in principle, was aimed to be a family story—by the textual elements, the dedication and the childhood memories in first person—to a structure closer to Remuiño de sombras25 ()26. The resemblance between the two works is probably not accidental since Neira Vilas was the author’s father’s favourite author (). Moreover, this way, Fraga turns the map of the streets of the British capital into a huge hive of emigrants and inscribes AZ in the collective memory of Galician emigration, both thematically and symbolically. However, today we know that the description of the midwife in search of possible pregnancy is an incident that Isabel Sánchez Edreira, the author’s mother, experienced, and the fetus was Xesús (), since the author picks up the description in Virtudes (e misterios), quoting this fragment, because it is a literal quote from AZ’s translation. He himself reveals to us that it is a meta-literary exercise: “Un momento que varias veces tratei de presenciar dende a escrita de ficción: “As mans da matrona son expertas. Os seus dedos beliscan e as palmas palpan guiadas por horas de eficaces servizos no control de inmigración […] teimosa no seu cometido, o de evitar que con aquela nova vida se cole de contrabando outra nova vida máis”27 ().

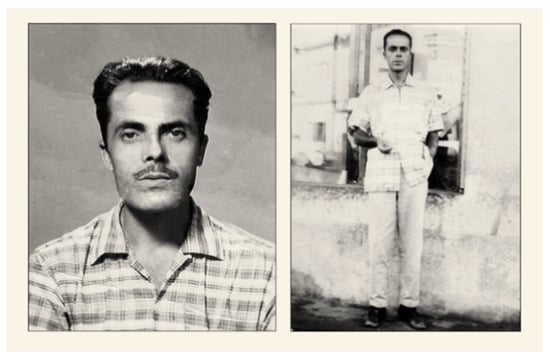

In essence, after multiple experiments of some works prior to Virtudes (e misterios), both Fraga and Ruido come to adhere to a narrative framework that subverts the most classic distinctions between the intimate and the public, the political and the personal, to show identities, affiliations and inheritances. An approach that they achieve using a great range of resources, which together create what Leonor Arfuch calls “biographical space”: interviews, chronicle, private diary, autobiography, biography, story, documentary research28. Means and techniques to which in the case of Ruido we can still add archive images, her own video recordings or fragments of theatrical pieces, among others29. A collage in which, however, what stands out the most is the use of the authors’ family albums, “un medio ampliamente disponible”30 that serves as a link with reality and invites “la empatía, la solidaridad y la responsabilidad hacia otros cercanos o distantes” (). The family photo album, although intimate, accounts for the universality of the theme because “nos vuelve susceptibles a percibir las conexiones entre historias y grupos divergentes”31 (). In this case, the emigrant as a foreigner, as an outcast and stateless, either in the host country or in the country of origin upon return. That is, the family photos achieve an emotional identification and show a commitment to those who are no longer there, because “the process of affiliative familial looking fosters and shapes the individual viewer’s relationship to this collective memory” (). Fraga and Ruido, putting all these elements into play, lead us through the migratory universe of parents and grandparents. Their vivid and intimate view of feelings and family relationships is perceived as transparent and honest, and allows the viewer/reader to adopt these memories as their own, since they are reflected in those experiences or they see their own parents and grandparents in those parents and grandparents, because “photographs in their enduring ‘umbilical’ connection to life are precisely the medium connecting first- and second-generation remembrance, memory and postmemory” (). Fraga’s grandfather’s suitcase is packed with the most curious objects, a leather case with glasses that are missing a lens, a Caravelle comb, Davis Menthol ointment, Clorets chewing gum, calendars from Lira’s butcher shop… They are old personal objects with no apparent relevance, but “memory’s duty is the duty of the descendants, and has two sides: remembrance and vigilance, to find the shape of the unnameable in the everyday” (). Objects, letters and photographs affirm the existence of the past and restore the presence of the absent. They are fragments with which Fraga creates a story, which, however, is impossible to reconstruct completely, there will always be mysteries. That is why it is logical to speak of a ‘poetics of ruins’ (), since the “fragmentos terrestres—islotes, masas rocosas, rompientes—parecen haberse diseminado sobre el mar de modo que hoy en día la mirada del profano no puede dejar de percibir un cierto parecido familiar pero tampoco puede reconstituir la coherencia perdida”32 (). The absolute veracity of past events or the temporal order in which they took place cannot be guaranteed. It is neither possible nor logical to do so, since the photos that once crossed the Atlantic in opposite directions now take on a significance of much more depth than the one they have as a document (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Virtudes (e misterioso) Xesús (). Reprinted with permission from Xesús (). Copyright 2020 Copyright Owner’s Xesús Fraga.

Figure 2.

Virtudes (e misterioso) Xesús (). Reprinted with permission from Xesús (). Copyright 2020 Copyright Owner’s Xesús Fraga.

As they are not designed to be seen as a whole, they lose the meaning that they were intended to have back then, to become evidence of a failed immigration and of an abandonment, that of the grandfather:

O obxecto destes retratos non era o de xuntarse, a non ser que os seus destinatarios se reunisen de novo. Pero o azar quixo unilos e remexelos nunha lata que, non se sabe moi ben como ou por que, gardaba na casa Ermila, unha das irmás da avoa. Agora, sobre o meu escritorio, reconstrúen ese imposible plano/contraplano transoceánico que enxergaba un diálogo diferido de miradas no que elas semellaban ollalo coma se o tivesen diante no mesmo cuarto para botarlle en cara, sen palabras, as súas expectativas, os seus reproches, os seus medos ante unha ausencia que presaxia o maior dos terrores, o abandono.33()

On the other hand, the photographs, as an apparently objective testimonial document, call into question History and its supremacy over memory and post-memory. In the case of Fraga, the photographs are, at times, susceptible to different interpretations, but above all, they acquire a different look due to the passage of time or the change in function that is given to them. This is what happens with the photographs that the grandfather sends from Venezuela, Figure 1: “a fotografía fora tomada dez anos antes de que acabase en mans da súa antiga familia, cun propósito que descoñeciamos pero que excluía claramente a intención de conmover dende a pena”34 (). In the case of Ruido, the letters and family pictures, which are tangible documents and therefore valid for a historian, are presented as a mere fiction of progress

The letters with photographs came and went: my first bicycle, the birthdays, the first family vacations, the knitted dresses that you sent me. […] The break-up grew with the distance, feeding on our efforts.We changed in your absence, to the point of becoming complete strangers, but the fiction of progress was almost perfect. […]How to retrieve all that absence of the time of the photographs? How to finish with the silence and the TV on at all times so as not to ask?()

In Sandra () opinion, the poetics of the ruins are contrasted with the fascist aesthetics of the monuments. Indeed, Ruido makes this same contrast when she states that “memory and oblivion are mutually bound, both are necessary for the complete occupation of time. Memory’s duty is the duty of the descendants, and has two sides: remembrance and vigilance, to find in the everyday the shape of the unnameable. But the official memory needs monuments: it aesthetisises death and horror” ().

In the Galician case, there is a static and epic image of emigration and the emigrant35. An essentialist image that has served as the basis for the configuration of a Galician identity36, in which there is no room for the failed emigrant that Fraga shows us and which curiously revolves around a concept to which the authors studied in this article hardly draw on, since it is certainly not central in their works, the morriña [homesickness]. Fraga and Ruido’s works oppose this image because they carry out a trip to the past, to ‘the inner memory’, to “become the subjects of history, against its history of the subjects, to arrest our look at the unpunished and intransitive look of the statues” (). Statues that in Galicia have almost always have been chosen to be represented as Penelope. That is the official and petrified image that honours the male figure of the emigrant and that serves as a metaphor for the subaltern nation. However, Ruido and Fraga tell us stories of specific individuals, stories in which the undisputed protagonists are also women. It is from the sum of individualities, since we know that they were multiplied by thousands, that we arrive at the collective history of the Galician emigration of this period.

3. From Widows of the Living, the Mater Amantisima, to Emigrant Women

The feminization of Galicia as a ‘female-nation’ (), which was built throughout the 19th and 20th centuries and which is hegemonic in the Galician discourse (), responds to a long list of factors: a literary discourse that is inevitably reborn and nourished by a female inaugural voice closely linked to the discourse of the emancipation of women—Rosalía de Castro—the political appropriation of the canonical sentimentality37 of Isabelline women’s literature38 in response to the misogynistic burden of foreign attacks39; the naturalization of the female sexualization of the nation from Celticism40 (), the general tendency to project feminine values in the environment (especially in rural areas)41 (); the fact that a woman’s body is, much more usually than a man’s, the map on which collective signifiers are inscribed; identities and values (); the existence of a fishing tradition accompanied by heritage protection measures such as matrilineal mandate and a male migratory model in which the wife waits like Penelope as administrator-protector-caregiver.

In addition, the concept of motherland is built under a specific description of the Galician woman’s way of being and some coercive guidelines of what her correct behaviour, her social role, should be. In this sense, we can consider paradigmatic the following quote from González Besada, extracted from his reception speech at the Royal Spanish Academy (RAE), in 1916. A text that revolves around the figure of Rosalía de Castro and in which the first eighteen pages are basically a description of the qualities that he believes Galician women have. A whole series of topics that, broadly speaking, also Manuel Murguía or Ramón Piñeiro42 repeat in their galicianist essays and that are at the base of such emblematic poems for Galician literature as “Penélope” by Díaz Castro ():

Ella, la que antes no era más que esposa amante y madre cariñosa, consagrada por entero a los menesteres de su casa, se crece, se agiganta, cuando la necesidad lo exige, y revenda revelando singulares actitudes para todo trabajo, lo mismo labra el campo que apacienta el ganado, nutre con su sabia al hijo del poderoso, compra y vende, cose, hila y teje, sin que haya oficio que se le resista, ni empresa que no acometa […]. Y esta condición adquiere especial relieve en el litoral […]. Cuando el hombre se ausenta y, salvando los mares, busca en lejanas tierras el sustento que la patria le niega, el hogar gallego no se resiente, antes bien, parece que su condición mejora al estímulo de una severa economía y diligente laboriosidad de los que quedan43.()

Now, within this essentialist construction of Galician identity and for the subject that concerns us in this paper, we want to draw attention to how the texts of Ruido and Fraga are a counterpoint to both that naturalized female image and the representation par excellence of Galicia: the widow of the living, the ageing mother. A traditional and essentialist identity construction of the experience of absence, based on a bipolar ideal model (): the migrant who does return and the rural woman who waits—usually compared to a Penelope static and incapacitated for desire, the first defined by homelessness, and the second by self-denial and communion with the land.

However, as I have already argued in the introduction to Xohana Torres: da viúva de vivo a muller navegante (), there is an alternative national construction line that also emanates from Rosalía de Castro but respecting what her texts had of gender vindication and denouncing both the situation of abandonment and the strenuous exploitation in which emigration placed Galician rural women. A transit that begins with Castro’s maddened and suicidal ‘widow of the living’ to give way to a succession of mad women and even monstrous witches. A representation of Galicia from the ‘other’, marginal and abject, and the realization that the individual, historical woman cannot wait forever, since misfortunes and time have made her aware of her untenable situation. A line that we can trace in the dramatic texts written by the components of the Irmandades da Fala, in texts of some exiles after the coup d’état of 1936 or in Xohana Torres’ work, who updates the topic with the ‘orphan of the living’ in her novel Adiós María (). The protagonist of Torres, Maxa, as in the case of Ruido, awaits the return of her parents who emigrated to France in the late 1960s. They left with the conviction that, while working abroad, their intelligent daughter will study to become a secretary, but the misogyny and blame of her grandmother frustrate the plan and bring Maxa back to the role of ‘orphan of the living’: sacrificed and selfless caretaker of the home to the point of becoming ill due to anaemia44. The teenager is not capable of writing to her parents and breaking the image of progress and well-being that she conveys in the letters in which, like in Ruido’s story, the “fiction of progress was almost perfect.” However, she resists madness and suicide to become a young woman desperately looking for a solution for the traumatic and suffocating situation she is experiencing, even if she only finds it through writing and dreams. That is, Torres’ teenage parents break with the traditional patterns of Galician emigration; in fact, Maxa’s mother realizes her fears in the face of so many past stories of abandonment and insists on emigrating herself. Likewise, and similar to Ruido’s family story, they seek to improve their daughter’s chances, although their expectations are still highly conditioned by social class. Now, in Adiós María there are references to historical events such as the closure of tram activities on the 31st of December of 1968 and Ruido’s parents emigrating between 1970 and 1987, when she was still very young. In addition, Ruido’s mother had already been a single migrant. In other words, there is a difference between Torres’s story and Ruido’s, which we can see as different steps in female emancipation and social aspirations. A big difference, based on a small temporal variation, which is very significant, because it shows the rapid evolution and the enormous leap that Galician society has experienced during those years. Especially in the case of women. Both family stories, that of Maxa as a literary character, and María, a woman of flesh and blood, close the cycle of the ‘widow of the living’ and open that of the migrant woman eager to improve and to educate herself and her children.

In Fraga’s narration, the grandmother is in principle a ‘widow of a living’ man. However, despite the dictatorship, the evil tongues that stigmatized women who emigrated alone and their families, and despite the highest rates of illegality, emigration is a very real possibility for women of this period and migratory networks are already functioning in feminine too.

Foi Fina a que falou: que o marido marchara a Venezuela, que non mandaba cartos porque disque non gañaba pero tampouco quería volver, que Virtudes tiña ao seu cargo tres fillas pequenas, que se eslombaba sen que lle chegasen os cartos, e que estaba disposta a irse ao estranxeiro ela tamén se iso lle aseguraba a mantenza das cativas. Fina escoitou, ollando a muller que falaba e a muller que calaba, a cabeza baixa. E logo dixo: ‘Eu volvo a semana despois da que vén. Se dá amañado para marchar, pode vir canda min.45 (pp. 166–77)

Virtudes finds obstacles to overcome such as not having a copy of the family record book or the written permission of her husband to be able to travel but manages to overcome them. The grandson presents his grandmother as a unique and exceptional character, “viña doutro lugar, doutro mundo, que falaba con nos pois con esas peculiaridades léxicas expresivas e ademais cando digo doutro mundo non me refiro a que viñese de Londres, é que viña da Galicia dos anos 40, do Londres dos 70 e todo estaba mesturábase nunha personalidade que resultaba única”46, but we can deduce how social circumstances and the emigrant tradition, logically, had to result in a lot of cases like Virtudes’. In fact, the intuition is confirmed by the stories of Amalia and Celia, which also broaden the range of different complex situations that led the women of this time to bring their families forward through emigration: “o fillo era a razón de ser última da súa vida en Londres, que lle permitira empezar de novo despois de verse repudiada na súa terra como nai solteira”47 (p. 888).

In principle, Fraga considers telling the emigration of the two grandparents:

[…] eu quería contar tanto a emigración do meu avó como a emigración da miña avoa. Pero eran dúas circunstancias moi diferentes no sentido de que eu vivín a emigración coa miña avoa. Primeiro porque coincidimos no tempo en Londres, como veciños, durante cinco anos, mentres eu era cativo, e tiñamos un contacto case diario e logo nas vacacións de verán cando ela viña aquí […] Digamos que sempre fun testemuño da súa vida emigrante. En cambio o meu avó desaparecera das nosas vidas moito antes de que eu nacera e todo aquilo era un misterio. Así que eu empecei a escribir primeiro sobre un e logo sobre outro e decateime de que todo o que tiña que ver coa emigración do meu avó era unha incógnita e que tiña que andar indagando, preguntando. En cambio para relatar como fora a vida da miña avoa tiña un tesouro na miña memoria, porque eu gardaba moitas lembranzas deses momentos compartidos, e pensaba que era una agasallo que ela me deixara […] Aí decateime de que realmente tiña moito mais para contar sobre a miña avoa e que merecía ese tratamento… O que de primeiras ía ser apenas un capítulo sobre ela e logo no segundo xa pasaba a meu avó converteuse creo que son os seis ou sete primeiros capítulos nos que vou debullando toda esa forma de ser dela48.()

Virtudes, who, for the author belongs to the domestic, day-to-day and known sphere, is elevated in someone’s “larger than life story”, which even displaces the curiosity that, at first, teases the mysterious life of the grandfather (). The migratory story of Fraga’s family does not begin with the emigration of the grandmother, but she is the great protagonist, without a doubt. It is the grandfather, when he is boarding towards Venezuela, that begins an endless movement, as if the Galician families touched by emigration were, forever, a pendulum without resistance in some kind of outer space. An individual act conditions successive generations. However, the facts speak for themselves and Fraga’s honest account highlights the role of Galician women in emigration, long before he began to tell us about his grandmother’s journey in London. History books do not capture, or at least do not emphasize, the consequences for those who were waiting in Galicia and neither does the collective memory of Galician emigration, with its traditional correlate ‘saudade/morriña’ [nostalgia/homesickness] as a universal element of masculine thinking about the motherland as feminine ().

In Fraga’s book, however, women are devoted, self-sacrificing mothers, but also women of desire and an overwhelming force for progress. The great-grandmother, Elena, leads a very hard life and brings up her daughters and granddaughters, with the added burden of having a sick husband and not being the owner of her land, for which she pays a ‘foro’49 fee. The grandmother, Virtudes, is terribly conditioned by her economic circumstances, and her life is also a race to provide for her family, her mother and her daughters. Indeed, as the author points out, her character matches the so-called theological virtues (). Nevertheless, she is aware of her circumstances. She weighs up whether it is wise to travel with her daughters to Venezuela and eventually decides to emigrate to London alone. She no longer wants to live conditioned by “servility and uncertainty” (). She needs to regain her dignity and become an independent woman. Betty’s persona will emerge from this decision. Virtudes

fixera os quince o mesmo ano que rematara a guerra civil e que xa adulta pasara da existencia labrega das agras e a servidume vilá á enorme cidade que nese tempo estaba a se reinventar de metrópole colonial en epicentro da modernidade. Londres obrara unha transformación: Virtudes convertérase en Betty, dúas mulleres que habitaban un mesmo físico. Unha coexistencia indisociable pero que concedía maior ou menor protagonismo a unha faceta ou outra segundo o contexto.50()

Moreover, the economic and socio-political circumstances of the British capital, which certainly make an impact, lead to a progressive and open mentality that was shocking in a Galicia living under the dictatorship. In A-Z, a book full of different voices and anecdotes, we find stories that are an example of it:

- —

- ¿Non me diredes que lles íades limpar a dous vellos que eran noivos?

- —

- ¿E por que non?

- —

- Mira, Candidad, xa me gustaría a min que dese tan pouco traballo como eles. […]

- —

- Non, se non teño nada en contra. Dígoo porque aquí, sería un escándalo.

- —

- Aquí a xente éche moi falangueira. E en Londres a ver a quen lle tiñan que dar explicacións51. ()

The life of Isabel, Fraga’s mother, the next link in the chain, is full of disappointments and she forgoes lots of things. As the older sister, she takes care of the younger children and is the first to work for a small wage. She seems to match point by point Besada’s description of the emigrant’s daughter:

Con su natural precocidad, es desde niña compañera de su madre y madre de sus hermanos; se informa de las estrecheces y preocupaciones del hogar, y toma a su cuidado, por singular condición de su carácter, la labor de endulzar las penas y de ocultar o disimular sus propias contrariedades. Así es de reflexiva, que mas que mujer formada de ilusiones y esperanzas, con la voz de la experiencia y los desengaños […]52.()53

But Isabel has dreamt since she was a child of studying to become a teacher. The emigration of her father fuels her hopes: “—agora imos ter cartos para que eu poida estudar a carreira para ser mestra?”54 (). Then, despite the abandonment and precariousness, she does not give up on her endeavour. Her thrifty faith does not only aspire to alleviate the family’s battered situation. She wants to: “construír un cativo capital que investir cando chegase nun futuro próximo a oportunidade de continuar cos estudos. Cada vez que sumaba unha cantidade, por minúscula que fose, mantiña viva esa arela”55 (pp. 369–70). For this reason, when Virtudes, pressed by the expenses, asks her for part of her money, Isabel cries and despairs about her bad luck. She does not achieve her dream of going to university, but she does not give up. She accumulates diplomas to certify her improving level of English and spends her first savings on a typewriter. When Isabel reaches the age of 21 and her mother gives her the typical English card with scenes illustrating the most characteristic events in the life of a young woman, there is only “unha coincidencia total aos dezanove: a máquina de escribir, símbolo dunha preparación—camiño longo e retorto no caso de miña nai”56 (pp. 474–75). That is to say, at the age of nineteen, and with a great deal of effort, she achieves a certain level of education that puts her on a par with any other English girl, but it has cost her much more. Years later, having returned to Galicia, as in the case of Xohana Torres’s Maxa, Isabel will try to take advantage of her education and work as a secretary, but, although she has been able to acquire this knowledge, her aspirations will be frustrated by the system of favours resulting from the deep-rooted caciquism that Galicia suffers from. In the end, she will make it on her own by setting up an English internship at home and will finally be able to pursue the profession she dreamed of. Now, the hope of going to university lies with his son Xesús, whom he speaks to in English so that he can keep the language he learned as a child emigrant.

In conclusion, the self-sacrifice and effort of Fraga’s female ancestry is not mythologized. They are not enormous beings who can cope with everything despite the difficulties and who grow, become bigger, when necessity demands it, without anger, without frustration and with a natural predisposition towards renunciation. The author does not dilute the traumatic memory of emigration, nor the struggle of Galician women for emancipation by elevating them to the category of extraordinary beings. Fraga’s novel cracks the aforementioned essentialist identity of the nation because it questions the role of women in emigration as ‘viúdas de vivo’ (widows of living) and the saudade/morriña [nostal-gia/nostalgia] loses centrality in the face of the economic precariousness and the desires and dreams. The use of family photographs exemplifies this point very well.

For Marianne Hirsch, family frameworks facilitate affiliative acts. For this reason, the family album can become an accessible lingua franca. However, we run the risk of sustaining a fundamentally heteronormative and reproductive form of social organization, as the family as an institution “delimits the possibilities of individual development and social horizons under patriarchy” and consequently “el género cotidiano de la fotografía familiar es una tecnología reproductiva heteronormativa que produce y fija a la familia y sus mitologías”57 (). However, both authors’ narratives and photographs have little that is heteronormative. The ‘abnormality’ of their family albums becomes evident when we inquire into the usual strategies by which absent masculinity was restored. Thus, for example, it was customary to take a family photo in the days prior to departure and it was common practice to make photomontages that included the men when they had already been emigrants for some time, as Javier Lorenzo () points out in his master’s thesis at the University of Barcelona Hombres ausentes en la obra de Luís Seoane. La construcción de la masculinidad ausente en la literatura emigrante gallega de mediados del Siglo XX58.

En estos fotomontajes pertenecientes a álbumes familiares, el padre de familia y otro familiar sacerdote, ambos emigrados en América y ausentes en la foto original, son incluidos en la misma mediante un fotomontaje para naturalizar así el poder simbólico masculino a pesar de la ausencia59. (p. 4)

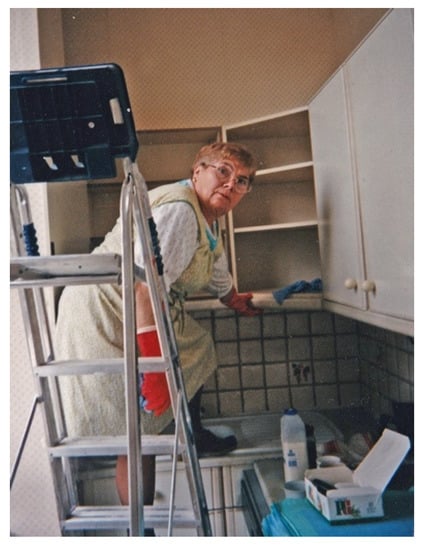

A custom also echoed by Sara Rosales () who, in her study of private photography in Galician emigration to America in the twentieth century, came across montages in which couples married by proxy posed together on their wedding day or reconstituted family pictures. The lack of a family photo prior to the departure of Fraga’s grandfather, the femininity of the photo of Virtudes with her three daughters that illustrates the cover of the book (Figure 2) and the absence of the grandfather or the non-existence of a photomontage that brings the family together signify Fraga’s grandmother as a “widow of a living man”. In addition, Rosales points out another issue that seems to us to be very relevant: the images never showed emigrant men at work. In contrast, Ruido’s and Fraga’s family photographs break with this convention. The photographs reproduced in Fraga’s book and Ruido’s project highlight the work of emigrant women.

In the case of Fraga, Figure 3 and Figure 4 are illustrative. In the case of Ruido, Figure 5 and Figure 6, the family photos of the emigrant couple with their children are interspersed with images of the world of work in the factory, whether current or from the past, in which the presence of working women is evident.

Figure 3.

Virtudes working, with cleaning products, and tea PG. Virtudes (e misterioso) Xesús (). Reprinted with permission from Xesús (). Copyright 2020 Copyright Owner’s Xesús Fraga.

Figure 4.

Virtudes and other workers at the nurses’ home at Bramham Gardens. Virtudes (e misterioso) Xesús (). Reprinted with permission from Xesús (). Copyright 2020 Copyright Owner’s Xesús Fraga.

Figure 5.

The inner memory María (). Reprinted with permission from María (). Copyright 2002 Copyright Owner’s María Ruido.

Figure 6.

The inner memory María (). Reprinted with permission from María (). Copyright 2002 Copyright Owner’s María Ruido.

The intention that Ruido gives to her project is clear, as the subtitle of her script states: “For a (thorough) look at the representation of (self)foreignness, the images of work and of absence”. She wants to recover individual bodies, especially those of women, and with them the memory that has been marked on them. She does this as a contrast to Franco’s biopolitics that conceals the emigration of the 1960s and 1970s, but she also manages to steal women from the national discourse: the life of the living as the body of the nation. Moreover, as we shall see in the following section, the works of these two authors problematize the return and barely make room for the discourse of homesickness.

Finally, the collective images in the workplaces fulfil another important function: they take us out of the particular and familiar to lead us to the memory of Galician emigration in this period.

4. The Fragmentation of Family Members and the Return

Some of the elements that Fraga and Ruido talk about in their works, such as the sound of the television sets, a toy TV in Fraga’s case and the one that was on at all hours to cover the silence of absences in Ruido’s, are not even memories as such. As Augé points out, they are traces, signs of absence, and are “desconectadas de todo relato posible o creíble; se han desligado del recuerdo”60 (). Sometimes they do not even constitute the ruins of a story to be reconstructed but speak to us of memories that will never come to exist. For Ruido, they are the evidence of absence, of a family life that she will never experience. On the other hand, Fraga searches in the ghostly images of his childhood stream, the Counter’s Creek, not for childhood memories and anecdotes but for those other possible selves, those Tonys forgotten in London that speak to him of other parallel lives, the ones he could have had if his parents had stayed in his hometown. They are shadows, connections, traces that in no way can we join together to form a memory because the memory does not exist. A restlessness and a mystery that was possibly latent in all the family members:

EX FUTUROS: II

Tamén meus pais deixaron atrás posibles existencias que non se lograron. Durante moito tempo, obcecado nas preguntas polo meu ex futuro, non fun quen de reparar nos deles. Cando oía a miña nai proclamar que tiñan morriña de Londres, ignoraba que quizais o que botaba en falta, ademais da cidade, era a vida que esta lles podería permitir61.()

The idea of split identity is very present and easily traceable in the texts that deal with Galician emigration to London, as the reflections on this conflictive relationship with identity are always associated with the difficulties that the English have in pronouncing Galician names, which they end up anglicising. Kristy () in her study Writing Galicia into the World: New Cartographies, New Poetics points out that this is a characteristic of what she calls generation 2.0, the children of emigrants who were also emigrants in the 1970s62. This is the generation on which she focuses her study. For (), the children’s novels erase the territorial borders of Galicia to extend them to these new migratory settlements that emerged from the 1960s and the 1970s onwards. Thus, because of this new cartography, hybrid identities emerge, altering the traditional coordinates of Galician identity: lingua [language], terra [land], morriña [homesickness]. However, the same question arises in A Veiga é como un tempo distinto, a novel in which the two main characters emigrate without family responsibilities and are not the children of emigrants. In Virtudes (e misterios), too, these fragmented and complex identities arise, but they characterise both the generation of the parents and grandparents and that of the children: Virtudes/Betty and Xesús/Tony. Moreover, in Ruido’s story, although we do not find this name changing so reiterative in the novels of London emigration, the author’s feeling of foreignness points to the author’s ceasing to be in order to become the “other”, the different, the foreigner: “Tales of the other, of the stranger (foreigner) in me” (Ruido). María Ruido is the daughter of the Germans and therefore German herself. She has not lived through emigration but has grown up conditioned by absence. A fact that distinguished her, which also did not allow her to be just another Galician child.

- -

- Foreigners. You get here, foreigner. The Germans have come, and that hurts, because they treat you like.—Well, they treat you normally.

- -

- Yes, but it hurts, because they say that word. They don’t say family, neighbours. Here come the Germans.—There is the German.

- -

- And that hurts, because inside, you feel Spanish, normal, Spanish. And then they come and say that. Foreigner there, foreigner here. You don’t have a choice. Like a gypsy. You don’t have anything positive.

- -

- Foreigner here, foreigner there. Because there isn’t anything else. ()

It is for all these reasons that Ruido, as we have already pointed out, writes from a position of inherited foreignness, understood as a debt to his parents’ generation. The return is not a reconstitution of identity. Ruido is the daughter of the Germans and Fraga’s mother, who insists that Xesús keeps Tony’s language, which is English. Likewise, the grandmother speaks in a hybrid language in which Virtudes and Betty intersect, provoking family hilarity:

Vinte e cinco anos en Londres, os que xa acumulaba cando nós eramos nenos, non evitaban que na súa fala agromase o substrato da súa anterior vida rural, nin tampouco ditos que naceran nese tempo—“Isto éche Corea!” usábao comodín para describir un abraio negativo—e que se fosen infiltrando nela para reforzar a súa natural expresividade. A adaptación fonética dos topónimos da capital—Edua (Edgware) Road ou Jaimesmí (Hammersmith)—coloreaba o seu galego británico, pero nada como a sonora e contundente colisión xuramentada para ceibar risos:—Fuckin’ merda!63 ()

Under these circumstances, using the Galician language, or at least the language found in the Academy’s dictionary, as an essential, invariable and defining element of a single identity is not possible, as Hooper pointed out. In addition, in the works of these two authors, we can hardly find any references to the sacro santa morriña [homesickness], or we find them linked to London and not to Galicia, as in the first quotation in this section.

Estaba a darse unha incipiente inversión de roles, na que a morriña se desprazara da terra natal á de acollida, un xogo de espellos que encarnaba, mellor que calquera outra pertenza, o cadro The Hay Wain de John Constable: vista en Londres, a bucólica escena evocaba, grazas a ollada deformadora da saudade, a Galicia rural que meus pais coñeceran na infancia; agora, enmarcada e nun lugar de honra no recibidor do piso de estrea, a reprodución que mercaran nunha visita á National Gallery lembrábanos a cidade culta dos museos e o coidado inglés pola paisaxe.64()

It is true that Fraga’s mother finds it hard to adapt to London and at first her head is in Betanzos, but she becomes fascinated by the cultural possibilities of the capital and is proud the first time she is taken for an Englishwoman. As for her father, Tito, he misses festivals and traditions, and reproduces them in London. However, the return is a practical question that above all has to do with interrupting or not the education of the children, with returning as caregivers of the grandparents who had brought up the grandchildren or a decision balanced between the weight of the family members who are in Galicia and those who continue in emigration. The return is not presented as an unavoidable action linked to a feeling of homesickness. Ruido’s father justifies it on the basis of possessions and land ownership. Galicians did not always take their children with them and always returned because they had somewhere to return to, a fact that distinguished them from emigrants of other origins:

- –

- Only the andalusians?

- –

- The andalusians, those from Madrid, well… as they could.

- –

- Were they grown already?

- –

- They had nothing, so they took them, because they had nothing here in Spain. Not a house, nothing. But we always wanted to come back to our land, so we saved for it. ()

Additionally, it is a decision that raises doubts, which is why it is delayed. Thus, even Virtudes, who had an obvious date for her return, her retirement, postpones leaving London for a few years, to remain a completely independent woman and the family provider, even though she no longer needs to do so.

In short, in both Fraga’s and Ruido’s stories, identity and return are problematized, not idealized. For women, the return, depending on the period in which it takes place, will be particularly hard. It can be a return to a more hostile, more cacique space with fewer opportunities for them.

5. Conclusions

Throughout the history of Galician emigration, women have not had an easy time either to emigrate or to return, because they were dependent on male support and were subjected to specific forms of sociability, recognition, and vulnerability (). This discrimination in comparison to men can be traced in literary texts as early as Rosalía de Castro’s poetry. Thus, for example, in the short story “Las medias rojas” (2015) by Emilia Pardo Bazán (), the father of the protagonist does not hesitate to beat and mark his daughter in order to discourage the desire to emigrate that he senses in her. Also, during the period of the Irmandades da Fala, Gonzalo López Abente (1878–1963) emphasises the impossibility of an honourable return in the case of the emigrant woman in his play María Rosa65 (). And finally, the same occurs in the contemporary A cicatriz Blanc66, a film by Margarita Ledo Andión about women emigration overseas. The ‘honour’ of the woman emigrant was always questionable. In the case of the works in scope, Ruido’s mother emigrates for the first time alone, “Between 1963 and 1966 my mother packed chocolate in a factory near Hamburg, however, she never knew the Baltic” (Ruido). A very brief description that nonetheless gives a good sense of the restrained and restricted life of the migrant women. Then, the story continues with the emigration as a couple and, although this period may seem to be a period of a woman emigrating as an accompaniment, Ruido’s mother is an emigrant worker in a German factory who, despite having previous work experience in the country, will receive less in retirement pay than her husband: “the factory gives us more than ten thousand pesetas a month (each). She was there for twenty years, and I was there eighteen, and I get more than her” (Ruido). In the case of Virtudes (e misterios), the grandmother faces a more illegal or unregulated emigration, because she does not have the necessary documents, which are in the hands of the head of the family, nor the protection of her signature. In the eyes of the law, Virtudes is a dependent individual. In Isabel’s case, it is her pregnancy that makes her entry into Britain illegal and leads to her subsequent dismissal. As mentioned in the introduction, female emigration is a fact assumed by the Spanish fascist dictatorship as inevitable, but neither desirable nor ‘natural’. Hence, the support networks that appear in Fraga’s story are religious, because, although there is no explicit criticism of them in the novel, since they were really of help to her mother and grandmother, the very description of the events reveals the control that the ecclesiastical sphere exercised over the ‘honour’ of the emigrant:

Á súa dereita atópase á súa amiga Marilyn, quen uns meses máis tarde, tamén cos dezanove de estrea, habería emigrar a Londres, cruzando así de novo as súas vidas nun entorno moi diferente a ese Betanzos católico que, non obstante, trata de reter o seu influxo sobre elas. Antes da súa partida, Marilyn e outras rapazas dispostas para a mesma viaxe reuníronse co párroco, don José Luis, para comprometerse nun voto de pureza como garante da súa fe en terras anglicanas.67()

In addition, such control itself implied a mark on the women who migrated and opened the door to questioning them, whatever their behaviour and circumstances

Absorta no barullo ledo que a envolveu á súa chegada, miña nai non repara en que algunhas das amigas que ficaron en Betanzos fan como que non a ven. Cando por fin se decata, pregunta e recibe por resposta que as nais lles prohibiron achegarse a ela: disque circulan contos libertinos sobre as mozas inglesas mais os non menos arrepiantes das españolas que viaxan a Londres co pecaminoso cometido de abortar. Quizais non chegou a oídos de nais e fillas que a rapaza á que evitan vén dun convento.68()

This explains the high number of women who emigrated because their situation in Galicia was already vulnerable: single mothers, abandoned women, wives or daughters of repressed people… Women who had no ‘honour’ to lose and who in the host countries found more open mentalities that allowed them to live in freedom: “había diversidade nos acordos: Amalia mantiña unha relación con Davy, de orixe mozambicana, […] e de cando en vez ela pasa a algunha noite na súa casa. Celia, no seu caso, levaba anos xa casada con Ali”69 (). This last point, the socio-political circumstances of the new host countries, which we have mentioned throughout the article, is essential. In the two cases studied, the family stories are close and recognisable, because they are the stories of the mothers’ and grandmothers’ generation. Also, they come to us at a time when the stories of emigration overseas are beginning to be considered exotic, because they are distant in time. But they are also stories that show Galician emigration as a continuum. In the case of Ruido’s story, it is the socio-economic conditions that force people to emigrate, and which last until today, which brings echoes of past migrations. In Fraga’s, the migratory continuum is even clearer because it links and connects two migratory wanderings. A matter that also arises in other recent novels, such as O paxáro de Nácara70 (2019) by Pura Salceda (). It is this contrast, from the women’s point of view, between the experience of emigration to America and emigration to Europe, or internal emigration to Barcelona in the case of Salceda, which highlights an issue that has not yet been well studied and to which historiography should return: how significant it was for them to emigrate to countries that, at that time, had a greater degree of emancipation and freedoms.

On the other hand, the stories of Fraga and Ruido fill a gap, since the emigration of the 1960s and 1970s had been almost not addressed in literary and artistic works. Indeed, their novels have a very important documentary and memorial value because they give a voice to a migratory wave in general and to emigrant women in particular, who provide vital experiences that are essential for the development of Galician society (). A silence which, in our opinion, responds to the difficulty of fitting the general characteristics of this migratory period, and above all the large number of women who participated in it, into the folklorized image that exalts homesickness as a core aspect of Galician identity. Although certain cultural products from the 1960s and 1970s, such as Ana Kiro, for example, continued to portray it, it does not fit in with the individual account of women emigration, indeed, it overshadows its memory. As we have already analysed, the female emigrant does not fit into this symbolic construction. Moreover, to consider that there can be a stable and identical feeling of saudade, century after century, is to consider “os afectos como monumentos invariábeis, idealizados e non performativos”71 (). A conception that, as we saw in the second section, Ruido attacks directly. She wants to recover the performative identity inscribed on the bodies of production, to shatter the statues erected by history, which are also designed following the patterns of the essentialist definition of the nation. Hence, her feeling of foreignness. A feeling that had already been echoed by Rosalía de Castro and which is a consequence of the marginality of her discourse.

In conclusion, Fraga and Ruido create memories of Galician emigration, but they also update its image, the representation of the emigrant and, consequently, that of Galicia. Pierre Bourdieu defines symbolic violence as the capacity of legitimation that manages to obviate the arbitrariness of symbolic production (). The mechanisms of symbolic violence rewrite the real experiences of discriminated people based on attitudes that turn them into subjects conceived as “others”, as “foreigners” and “threatening” () because it is a “violencia que arranca sumisiones que ni siquiera se perciben como tales apoyándose en unas «expectativas colectivas», en unas creencias socialmente inculcadas”72 (). For this reason, throughout the history of Galician emigration, the experience of the emigrant woman is ignored and the representation of the ‘widow of the living’ adapts to the myth of the matriarch waiting for redemption and takes the image of a mourning old woman who lives in terms of waiting. Likewise, the ‘other narratives’, those of young widows who go mad or commit suicide faced with the impossibility of living any kind of life, are expelled from the national narrative because, as Judith Butler has shown, the existence of such people, those ‘uncategorisable’, threatens the world’s view and the sense that has been taken as the basis for national construction (). To all this, with regard to emigration to Europe, we should still add a very strong class component that does not fit into a universal definition of Galicianness either, and which, in our opinion, flows in the migratory continuum towards the very strong presence of precariousness, in recent novels about the “new Galician diaspora”, much more present than the feeling of homesickness. The leap that the Galician working class took largely thanks to the emigration of this period is gigantic.

Fora o seu un sacrificio que primeiro procurara restituír a dignidade ferida pola ausencia do home, pero que axiña se proxectara a xeito dun investimento futuro que cobraría pleno sentido cando nós, os netos, fomos os primeiros da familia en pisar unha facultade: de pagar os foros en ferrados73 de trigo á licenciatura universitaria en apenas dúas xeracións74.()

A historical milestone which, when put in feminine terms, is even impressive: some families went from illiterate mothers to university-educated daughters. However, there are still very few texts that deal with this fact, perhaps because the current massive emigration of university students, again with a very strong female component, makes it an immeasurable milestone.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | See Law 56/1961 of 22 July 1961, presented by the Women’s Section. |

| 2 | It is clear that referring only to married women, the limitations of the Law, once again confirmed in the reform of the Civil Code in 1958, that marriage requires a power of direction that nature, religion, and history attribute to the husband. It continues to be a programmatic norm of the Spanish State, announced by the Second Declaration of the Labour Code, that of “freeing married women from the workshop and the factory.” (Act 56/1961, 22 July 1961). |

| 3 | The question of children, who often stayed here, is a key element in the cognitive-affective representation of this group. |

| 4 | Emphasis added. |

| 5 | In this list of authors we can include, among others, Carlos Casares, Xosé Fernández Ferreiro, Manuel Rivas, Antón Riveiro Coello, Xosé Manuel Sarille, Suso de Toro, Carlos Reigosa, Xabier Quiroga… |

| 6 | They assume the role of transmission of the certain memory. |

| 7 | Hirsch defines post-memory as “the relationship that the ‘generation after’ bears to the personal, collective, and cultural trauma of those who came before—to experiences they “remember” only by means of the stories, images, and behaviors among which they grew up. But these experiences were transmitted to them so deeply and affectively as to seem to constitute memories in their own right. Postmemory’s connection to the past is thus actually mediated not by recall but by imaginative investment, projection, and creation. To grow up with overwhelming inherited memories, to be dominated by narratives that preceded one’s birth or one’s consciousness, is to risk having one’s own life stories displaced, even evacuated, by our ancestors. It is to be shaped, however indirectly, by traumatic fragments of events that still defy narrative reconstruction and exceed comprehension. These events happened in the past, but their effects continue into the present. This is, I believe, the structure of postmemory and the process of its generation.” () |

| 8 | Note that, unlike the aforementioned authors who were born after the end of the Spanish Civil War, Fraga and Ruido did lived part of the migratory period detailed in their works. Although they live it as children. |