Abstract

This paper investigates border-making dynamics in the two political arenas where my subjectivity is most acutely implicated across time—the Jewish Holocaust (as an intergenerational victim) and the Aboriginal genocide (as an unwitting beneficiary). Albeit that there are many differences between the drivers of antisemitism and racism against Indigenous Australians, I investigate both of these racist structures through the lens of border-thinking as theorised by Walter Mignolo as a method of decolonisation (2006). The article has been formatted as an example of discursive border-crossing by juxtaposing theoretical ideas (particularly inspired by Zygmunt Bauman and Deborah Bird Rose) with interjections from my personal journal. I explore my own performative storytelling as a means for me to take responsibility to question power structures, acknowledge injustice, and to enact the potential for ethical dialogue between myself and others. This responsibility gestures to the possibility of border crossing as an ‘act of liberation’ that resides in the acknowledgement of historical injustices and their continued impact on both the beneficiaries and the victims of coloniality in the present.

1. Introduction

This article investigates the ways borders operate in order to explore the limits of personal responsibility for acknowledging injustice. In foregrounding my own process, my focus is on the value of the storytelling witness when faced with the two particular atrocities where I am the most implicated: as an intergenerational victim of the Jewish Holocaust and as an unwitting beneficiary of the Aboriginal genocide in Australia. It is important to note that I am not entering into a discussion of the causes of racism generally, but rather analysing their boundary-making drives. Sporadic italicised and boxed interjections from my personal diary are clearly demarcated. Although personal and academic writing are fundamentally different ways of communicating, by including diary entries, I endeavour to render divisions between the personal and political more porous. There is a need to share stories in a variety of media as a way of taking responsibility for witnessing and honouring them. I argue for the emancipatory value of different kinds of storytelling as a means to break down barriers between people, highlighting connections across time and space. I share my personal journey in the hope that it may encourage others on similar paths.

Personal Diary Entry No.1. October 2019

It is my second visit to the Djap Wurrung Heritage Protection Embassy, where activists have been camped out since last year to try and protect ancient birthing trees from destruction by Vicroads’ Western Highway duplication. At this time there are no workers threatening the trees so my attempt at taking responsibility for something I care about involves helping my partner to cook lunch and then amuse the activists’ children by teaching them juggling and hula-hooping.

Through the Djap Wurrung Facebook page I discovered that another Aboriginal activist group, Warriors of the Aboriginal Resistance (WAR), were recently visiting a nearby sacred women’s site, Sister Rocks, near Stawell. These rocks are covered with graffiti from early colonial times until the present. In consultation with the traditional owners, WAR decided not to clean the rocks by sandblasting them, but to close the site to public access with flagged rope. Their Facebook post states, ‘We urge all those to redirect the graffiti tagging to local church’s [sic] and other significant colonial buildings and institutions’.

Googling more on this site, I discovered a December 2018 ABC news article about Nazi graffiti that the Northern Grampians Shire Council, who own the rocks, had no plans to remove. Archaeologist, Darren Griffin, from the local Land Council states, ‘You get some good art and some bad art so where do you draw the line? Who makes the decision on what gets removed and what stays?’ (Cansdale 2018). Additionally, the Shire Council’s chief executive, Michael Bailey opines that the Nazi symbols were reprehensible, but ‘if we start to clean that, we’d effectively have to clean the whole rock work so allowing it to stay for a period of time is probably the best management’ (ibid.). His strategy seems to have paid off—in the photo posted by WAR, there are a number of layers of designs covering where the Nazi symbols used to be (at the bottom right of this rock). See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Sisters Rocks, near Stawell, 2019. (One Facebook comment on this photo reads ‘That fence will keep the colonials out!’).

2. Border Thinking

In Debating and Defining Borders: Philosophical and Theoretical Perspectives, authors Anthony Cooper and Søren Tinning observe ‘bordering’ not only as a geopolitical activity, but also ‘in the messy here-and-now micro-politics of everyday life practices and experiences’ (Cooper and Tinning 2019, p. 1). This ‘messiness’ speaks to my use of personal stories in this article, as well as the way I use my unavoidable awareness of the Holocaust (as a Jew) to help my developing understanding of a distinctly different tragedy that I feel responsible for trying to understand: the Aboriginal genocide.

In her 2019 Australian Academy of the Humanities Annual Lecture, Professor Joy Damousi forcefully critiqued ‘fortress Australia’s’ cruel use of its borders to exclude refugees. Additionally, she acknowledged the role of her personal history as a child of Greek migrants in propelling her research, telling the story of learning of the plight of her mother’s neighbours, the northern Greek Jews, under the Nazi invasion. In her lecture, Damousi clearly showed the links between the Aboriginal and Jewish genocides: ‘Dehumanising the other is an effective way of justifying inhumanity’ (Damousi 2019). Additionally, she affirmed the supreme importance of witnessing, ‘Before there can be justice, there must be truth’ (ibid.).

Another Australian historian, the late Professor Colin Tatz, would concur. In his book, With Intent to Destroy, he describes growing up in South Africa. By 1960 the extremes of racism against blacks forced him to make the decision leave (Tatz 2003, pp. 7–8). In 2003, responding to conservative attacks from genocide denialists in Australia on scholars with a ‘Jewish background’, Tatz asserts that he ‘would prefer to be regarded as one of Jewish foreground, as it is that foreground of my existence which compels me morally to investigate all manners and matters of genocide’ (pp. 140–41). Sharing Jewishness, Australian citizenship, and South African heritage with Tatz, I am also conscious of the impact of my background on my research interests.

Growing up in Australia in the 70′s, my schooling did not challenge the complacency of, in Stanner’s phrasing, ‘the great Australian silence’ (Stanner 1968). I had very little awareness of the awful toll of colonisation on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This article is part of my slow process of self-education.1 Settler Australian artist and historian, Rachel Joy, has followed a parallel path. She asserts that to be non-Indigenous in Australia with integrity, ‘we must ask ourselves how we can unsettle our Occupier subjectivity’ (Joy 2017a, pp. 143–44). She emphasises the importance of finding valid processes for this ‘on-going journey’ (p. 144), and aims for her art to create ‘a space of inquiry, of ethical encounter that offers transformation’ (Joy 2017b, p. 125).

A pivotal text with similar social justice aspirations in the North American context, is Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands. As declared in the introduction to the 2012 publication, ‘Borderlands is dangerous only because it has the power to change minds, to disturb complacencies’ (Anzaldúa 1987, p. 3). Anzaldúa’s book is astute in both its political analysis and poetic expression, for example her injunction to enter a new consciousness by being ‘on both shores at once, and, at once, see through serpent and eagle eyes’ (pp. 100–1). She argues that a hybrid identity as ‘outsider within’ gives one ‘the ability to hold multiple social perspectives while simultaneously maintaining a centre that revolves around fighting against concrete material forms of oppression’ (p. 7). Additionally, it is important to note her insistence that her thinking does not just apply to the U.S./Mexican border—borderlands are present wherever cultures ‘edge’ each other (p. 19). They are the places where distinctions between inside and outside blur, locations for thinking and releasing fears of what may come from outside (Mignolo 2012, p. 260). According to Walter Mignolo, who was inspired by Anzaldúa’s work, ‘border thinking’ emerged

from and as a response to the violence (frontiers) of imperial/territorial epistemology and the rhetoric of modernity (and globalization) of salvation that continues to be implemented on the assumption of the inferiority or devilish intentions of the Other and, therefore, continues to justify oppression and exploitation as well as eradication of the difference.(Mignolo and Tlostanova 2006, p. 206)

In the Australian context, Richard Davis argues that ‘[t]he frontier is one of the most pervasive, evocative tropes underlying the production of national identity’ (Rose and Davis 2006, p. iii). Deborah Bird Rose extends this idea even further, asserting that in settler societies the frontier is ‘a site for the making of the nation’ (p. 57). Goenpul scholar, Aileen Moreton-Robinson, finds that contemporary Indigenous sovereignty struggles occur in the Australian borderlands as Indigenous bodies undermine the possibility of white Australian belonging (Moreton-Robinson 2007, p. 301). The epistemic violence that is the result of white efforts to maintain Australian social order ‘continues in the everyday’ (p. 311). However, bearing and hearing witness are essential steps towards reparation. Rose outlines two precepts for structuring ethical dialogue: recognition that dialogue is always situated, and openness to the destabilisation of one’s own ground (Rose and Davis 2006, p. 49).

Personal Diary Entry No. 2. November 1984

A group of my friends from the Zionist youth group, Habonim-Dror, have spent the year after finishing high school in Israel. I join them at the end of the year at the kibbutz they’re working on, in the disputed Golan Heights. In general the kibbutzniks are animal-lovers. But the men I’m working with in the banana plantation so hate a black dog that they believe has strayed from over the border in Syria, that they shoot it, burn it, and leave its blackened carcass, legs pointing into the air, lying in the yard.

As Queensland poet and activist, Oodgeroo Noonuccal (Kath Walker) poetically states, the past always has the potential to cross into the present and destabilise us:

Let no one say the past is dead

The past is all about us and within (Walker 1981, p. 93).

Another expert from a troubled era, philosopher Hannah Arendt, hopes ‘[t]hat even in the darkest of times we have the right to expect some illumination’ from stories of the past (Arendt 1968, p. ix). Arendt was writing in the wake of WWII and the Holocaust. There are some who argue against a possible dilution of the term ‘holocaust’ by applying it to situations outside of WWII (Hier 2010), but Arendt was not one of them. She was not afraid of the controversy aroused by her assertion that the Nazi’s actions constituted a crime against humanity (Rose 2001, p. 148). Justification for Arendt’s claim can be found in the fact that the Nazi’s aims certainly went beyond Jewish concerns, envisioning a complete control of time in which, according to Hatley,

no room is left for the ongoing generation and generations of responsibility. Human temporality itself would collapse into a “final solution”, an apocalyptic moment in which the ongoing bearing and birthing of differentiation and heterogeneity […] would simply end.(Hatley 2012, p. 62)

On the other hand, Arendt was clear that she did not regard Germans to be guilty ‘as a whole’. I find her distinction between feeling guilty and taking responsibility to be useful:

There is such a thing as responsibility for things one has not done; one can be held liable for them. But there is no such thing as being or feeling guilty for things that happened without oneself actively participating in them (Arendt 1987, p. 104). [… W]e are always held responsible for the sins of our fathers as we reap the rewards of their merits; but we are of course not guilty of their misdeeds, either morally or legally, nor can we ascribe their deeds to our own merits (p. 108).

Personal Diary Entry No. 3. July 2020

I’m lying awake worrying about the residents of the North Melbourne and Kensington public housing estates who are under ‘hard lock down’ restrictions due to the new COVID-19 outbreak. I’m also aware that my insomniac worrying is not doing those people any good. … I remember a story of what happened at a Bono concert to raise funds for starving people in Ethiopia. Bono stood at the microphone and slowly clicked his fingers. After a while he said, ‘Every time I click my fingers a child in Africa dies’. The silence was punctured by someone in the audience shouting out, ‘Well, stop fucking clicking!!!!’2

3. Witnessing Holocausts

The term ‘holocaust’ has been used by several theorists to describe the situation in Australia, particularly powerfully by Rose who described colonisation here as ‘the great Australian holocaust’ (Ravenscroft 2012, p. 3). In a specific Australian example, Rose relates a horrific story told to her by Ngariman man, Riley Young Winpilin. In the early 1900s a station boss tasked an Aboriginal worker who was due to get his wages to build a big woodpile. The boss then told him to stand on top of the pile so he could take his photo, but instead the boss shot him dead and used the burning wood to get rid of the evidence (Rose 1991, p. 260). Rose argues that Australia was conquered by practical men, most of whom ‘possessed a tunnel vision focussed on the future […] that detached actions from consequences. Brutality was always said to be in the past; visions of the future demanded that it be forgotten’ (p. 262). However, she theorises that in telling this story Winpilin links past and present, making listeners (and readers) witnesses. By re-telling it again here, I am making you, my reader, another witness in your present.

I see a terrifying connection between this story and one I related above about kibbutzniks shooting, burning, and abandoning a dog from across the border. In Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive, Giorgio Agamben values testimony to the extent that ‘human beings are human insofar as they bear witness to the inhuman’ (Agamben 1999, p. 121). He elaborates on Holocaust survivor, Primo Levi’s understanding that the true witness of the concentration camps is the one who cannot speak, the one who is not human, the ‘Muselmann’ (p. 88). Muselmann (German for Muslim) was a term widely used by concentration camp victims to describe prisoners who were near death, perhaps because their prone state recalled a Muslim prostrated during prayer (Shoah Resource Center n.d.). This figure of the no-longer-human is the one tasked with bearing witness to the impossibility of witnessing (Mills 2003).3

Personal Diary Entry No. 4. May 2012

Visiting the National Gallery of Victoria’s Design Studio, I find a video work that crosses borders of propriety in Holocaust memorialisation: Jane Korman’s Dancing Auschwitz—I will survive. It features Korman, her father, who is a Holocaust survivor, and her children dancing to Gloria Gaynor’s hit song ‘I Will Survive’. This work attracted much controversy (Ferst 2010), the main argument against it being that it was disrespectful to the many people who did not survive Auschwitz—the yes-sayers were of course pleased that survivors were being celebrated.

Levi relates that the SS militia tormented their prisoners: ‘However this war may end, we have won the war against you; none of you will be left to bear witness, but even if someone were to survive, the world would not believe him’ (Levi 2017, p. 1). Another Holocaust survivor, Elie Wiesel, wrote, ‘It must be emphasized that the victims suffered more, and more profoundly, from the indifference of on-lookers than from the brutality of the executioner’ (Wiesel 1968, p. 229). Rose describes the violence of this indifference as ‘an active reinscription of a boundary of exclusion’ (Rose 2011, p. 98).

Personal Diary Entry No. 5. May 2015

Since 1999 I’ve worked with Melbourne Playback Theatre Company. In a Playback show audience members are invited onto the stage to share a true story about their lives which is then improvised back as a theatrical performance. One of our newest members, Yawuru woman, Lenka Vanderboom, has coordinated a Reconciliation Week event, ‘Down Under’. We hear and enact stories from a Queensland Aboriginal woman who’s very proud of her grandfather who escaped from Palm Island by swimming to the mainland (dodging crocodiles!) and rode a wild brumby home to Cherbourg mission; and from a Dutch woman who cries as she relates how appalled she is by racism.

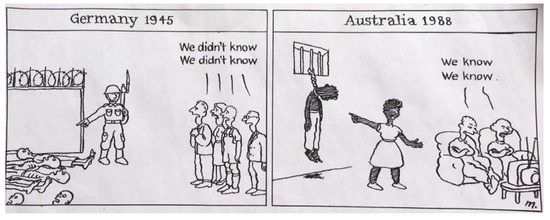

In the foyer of the theatre Lenka had co-curated with Jim Bridges, President of the Australian Cartoon Museum, an exhibition, ‘She’ll be right, Mate?—An Indigenous History in Australian Cartoons’. After the event, as I was helping with the bump out, one of the cartoons fell off the board it was attached to and Jim asked, ‘Do you want to keep that one? … Maybe it’s significant?’ It was this (see Figure 2):

Figure 2.

Matthew Martin, from Australian Cartoon Museum’s 2014 exhibition, ‘She’ll be right, mate? An Indigenous History in Australian Cartoons’, (originally published Sydney Morning Herald, 1988). Courtesy Matthew Martin.

An alternative to the onerous concepts of responsibility proposed by these Holocaust scholars is offered by Kelly Oliver. She privileges the idea of ‘response-ability’; a ‘being with’ others dependent on the exchange of address and response that is an essential aspect of bearing witness (Oliver 2001, pp. 88–91). In this context one can see the importance of Rose’s assertion that her writing is.

an act of witness; it is an effort not only to testify to the lives of others but to do so in ways that bring into our ken the entanglements that hold the lives of all of us within the skein of life […] if no stories are told, if all the violence goes unremarked, then we are thrust into the world of the doubly violated. […] If we choose silence […] we ourselves become deader than dead, for without an ethical sensibility we lose our capacity to be responsive to the dynamic exuberance of life.(Rose 2012, pp. 138–39)

I am inspired by this beautifully positive perspective on the responsibility of witnessing, and the way it invites connection. Rose advocates a version of relationality that breaks barriers—’to live is to be part of it all: clear boundaries become an invitation to act as if there were a place of moral purity’ (Rose 2011, p. 142). She shows that in contrast to modernity’s idea of monological time as a linear sequence, there are ‘a plurality of times existing together’ (Chakrabarty 1997, p. 25), speaking ‘heteroglossic narratives’ (Rose 2004, p. 28). Acknowledging this complex diversity enlarges our thinking, and opens us to moral responsibility. Additionally, her call ‘to act, to engage in the dramas of call-and-response’ (Rose 2011, p. 143) speaks to the modus operandi of performance—a space where actions and responses are played out second by second. A space where new possibilities of ways of thinking and doing are tried and responded to.

Personal Diary Entry No. 6. May 2017

As a small gesture of ‘taking responsibility’, I went to a morning of tree-planting at Coranderrk Bushland Reserve, near Healesville, targeted at restoring habitat for the endangered helmeted honeyeater and leadbeater’s possum. One of the hosts, a local Wurundjeri elder whose family had lived on the Aboriginal reserve here, was moved to tears at the large turnout of volunteers.

The play, Coranderrk: We will show the country, by Nanni and James (2013) uses testimony from the 1881 Victorian Parliamentary Inquiry detailing the Coranderrk mission residents’ protests at being forced to move by local pastoralists who wanted access to their productive land. They were granted a temporary reprieve but the so-called Board for the Protection of Aborigines managed to destroy the community by only allowing people who, in the racist terminology of the period, were regarded as ‘full-bloods’ to remain, and forcing Aboriginal people of mixed heritage to assimilate into the wider community. A perverse example of border-making—forcing people into reserves to free up land for settlers; forcing them out (on the basis of ‘bloodline’ boundaries) when the land of their reserve was desired.

In Modernity and the Holocaust, Zygmunt Bauman uses a personal anecdote to delve into complex ideas about the boundaries of responsibility. When he was a young child, his grandfather story told him the story of a saintly sage travelling with a donkey loaded with food meeting a starving beggar. As the sage is unpacking his sacks to feed him, the beggar dies. The sage prays, ‘Punish me, Oh Lord, as I failed to save the life of my fellow man!’ (Bauman 2000, p. 204).

Bauman comments that the story is illogical, but not wrong and uses it to discuss the dilemma of people who had to decide whether to be responsible for endangering themselves and their family in order to save persecuted Jews. He finds that the only way to shatter the ‘mental prison’ of the Holocaust which has ‘outlived its builders and its guards’ is ‘morally purifying shame’ (p. 205). He concludes his book by emphasising what I think is an interesting perspective on the boundary between defying evil and being driven by the logic of self-preservation: ‘Is there a magic threshold of defiance beyond which the technology of evil grounds to a halt?’ (p. 207).

Here, the boundary of the ‘magic threshold’ is a positive structure, enabling a person to defy evil. However, often boundaries are counter-productive. Bauman cautions against our tendency to see the Holocaust as a unique aberration, our way of ‘framing’ it, confined in space and limited in time, separate from everything else in life, as a way of protecting ourselves from the implications it raises (pp. vii, xii). He proposes that rather than seeing the Holocaust as a picture neatly framed, we will gain better insights by regarding it as a window through which to more clearly see the world in which we currently live: ‘Auschwitz expands the universe of consciousness no less than landing on the moon’ (Kren and Rappoport 1980, p. 143). He admonishes us that the conditions that created Auschwitz still exist and so it could happen again (Bauman 2000, p. 11). He is lamentably right—at least five genocides have occurred since the Jewish Holocaust (Chalk and Jonassohn 1990).

Bauman argues that the human need to create boundaries is the main driver of antisemitism. As a people without a homeland (like the Romani and Sinti, who were also persecuted by the Nazis), the presence of Jews challenged a boundary that was needed for people to feel secure. They were ‘foreigners inside’ and the intensity of antisemitism is ‘proportional to the urgency and ferocity of the boundary-drawing and boundary-defining drive’ (Bauman 2000, p. 34).4

Of course the Jews (like the Romani and Sinti), did originally have a homeland (and the Jews have a highly disputed one again now). Since the Israelites were exiled over 2000 years ago, Jewish diasporic ceremony has had a focus on yearning to return to the ‘promised land’. At the end of the Passover and other important ceremonies, Jews all over the world say to each other ‘Next Year in Jerusalem!’. Jewish philosopher, Emmanuel Levinas, conveyed the idea of an imaginary place: ‘the people of Israel are the people of the Book [… whose] land rests on the Revelation […] and owes nothing to any organic attachment to a particular piece of soil’ (Hand 2001, p. 192). (Though some contemporary Israelis are very attached to particular pieces of soil.)

David Turner characterises Aboriginal Australia as being covered by many boundaried ‘promised lands’ each with its own ‘chosen people’ (Turner 1988, p. 479). Since colonisation, Aboriginal people have suffered from being moved off their ‘promised lands’, however they still strongly assert their relationship to their ancestral places. Moreton-Robinson states that ‘through cultural protocols and the commonality of our ontological relationship to country we can be in place but away from our home country’ (Moreton-Robinson 2003, p. 33).5 She emphasises the inalienable relationship between particular tracts of country that are ‘constitutive of us’ (p. 31). This relationship is derived from the Dreaming.

Kombu-merri elder and University of Queensland academic, Mary Graham defines the Dreaming as ‘a combination of meaning (about life and all reality), and an action guide to living’ (Graham 2008). She describes how originally the whole earth was like a moonscape and it was the Creator Beings who broke through its surface who created the landscape and all the creatures that live on it through their interactions. These relationships exist still: ‘There is never a barrier between the mind and the Creative; the whole repertoire of what is possible continually presents or is expressed as an infinite range of Dreamings’ (ibid.). Rose echoes this concept: ‘The boundary between Dreaming and ordinary is cross-cut by ceremony, site-based action, story and song, and the ecological experience of on-going life’ (Rose 2004, p. 56). As acclaimed Waanyi writer, Alexis Wright, affirms: ‘stories are told to and by this ancestral land’ (Ravenscroft 2012, p. 31)—an evocative description of the porous boundary between Country and people.

Personal Diary Entry No. 7. July 2008

I’m based in Alekarenge (Ali Curung), Northern Territory, working for The Song Room, teaching theatre and music in schools. I’m looking for opportunities to perform my graduation piece from my recent Diploma in Animateuring from the Victorian College of the Arts—a solo storytelling of the Book of Job. I’m playing guitar in the local church and discuss the idea with a Warlpiri elder there who agrees that a lot of Old Testament imagery resonates with central Australia—dry creek beds that burst their banks in the wet, braying donkeys, the importance of livestock, rubbish dumps, how to deal with intense suffering. However we decide to remove the disparaging remarks about dogs—dogs being such a familiar and valued part of camp life. (Alekarenge actually means ‘country of the dog’.) Strangely, when I was performing the show outside at a nearby community, Owairtilla (Canteen Creek), when I got to the part when I would have been saying:

And now I am jeered at by streetboys,

whose fathers I would have considered

unfit to take care of my dogs.

They grunted together in the bushes,

and copulated in the dust—

what were they but mongrels? (Mitchell 1989, p. 70)

I had to pause because a big mob of barking dogs bounded through the ‘performance’ space.

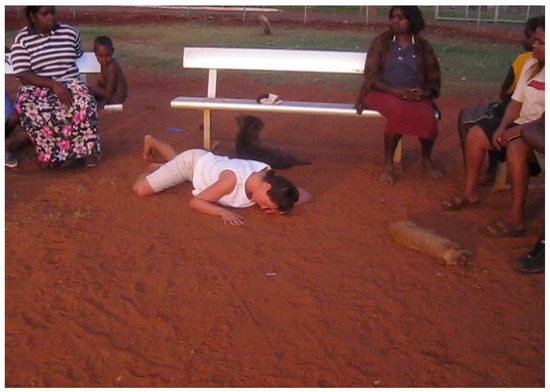

At the time when I was so interested in The Book of Job, it was the individual’s task of seeing beyond suffering that was important to me. Rose focusses on Job’s ‘call for connection’ (Rose 2011, p. 73), and she compares the Old Testament story to one she learnt in Yarralin, a small community north-west of Alekarenge (p. 71). In the story of the Moon and the Dingo, Moon persuades Dingo to die, reassuring him that he will return, just as Moon does. But Dingo cannot return after death, and nor can humans (pp. 71–2)—traditionally Yarralin people believe that in the Dreaming dingo and human were one (Rose 2000, p. 47). Rose imagines Job with a stray dog to keep him company—like Dingo who had his Dingo mates (Rose 2011, p. 78). But God and the Moon are so powerful they are condemned to ‘utter loneliness’ (p. 79). See Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The dogs and me performing the ‘Book of Job’ at Owairtilla, 2008. Photo: Alex Pinder.

I now return to some of the destructive ways boundary-making has been used in the context of the Aboriginal genocide and Holocaust. Ian McLean shows how the British humanitarian lobby argued that once Aboriginal people were no longer a threat to colonisation, ‘that is, the frontier had passed’, they would not be considered ‘vermin to be exterminated’, but ‘would be studied and protected as if an endangered species’ (McLean 2016, p. 54). Rose demonstrates that the initial violence was later denied, or lost to memory (Rose 1991, p. 34). Settler violence often occurred as a matter of indifference, negligence, and casual cruelty and was ‘attributed to the agency of history rather than to settlers’ own agency’ (Rose 2001, p. 153). This was an effective way for colonisers to pretend to themselves that ‘the annihilation would happen without their having to take responsibility for it’ (Rose 1991, p. 34). As Arendt argued in Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, Nazis such as Eichmann relied on other ways to evade responsibility (Arendt and Kroh 1964).

According to Bauman, Jews in pre-modern Europe, never passed the ‘threat’ frontier, sitting ‘awkwardly astride the barricade, thereby compromising its impregnability’ (my emphasis, p. 37). The paradox of the ‘foreigners inside’ is particularly poignant in terms of the relationship between Judaism and Christianity. Jews are neither not-yet-converted heathens nor fallen-from-grace heretics; they are both the fathers of Christianity and its detractors (ibid.). This generalised view (as opposed to the Jews that many people were used to dealing with in their everyday lives) is an inherent aspect of racism. It was explicitly stated in a 1940 document setting out ghetto rules: ‘The individual Jew does not exist for the German authorities in the occupied territory’ (p. 121). As the German authorities correctly perceived, when individuals make person-to-person relationships, it is much harder to treat someone in a general way—to put them in a box of undesirables to be disposed of.

In writing this essay, I have been endeavouring to find ways of making person-to person relationships. Of course the flow is one-way—I am sharing anecdotes from my life—but my aim is that the reader will be triggered to remember analogous stories from their own life. By incorporating material from vastly different places and times, I have crossed borders in a way that has enabled me to break down barriers to connection that preclude mutual understanding.

Personal Diary Entry No. 8. September 2009

I’m performing my show The Magic Teapot, at the Singapore International Children’s Festival. At my hotel there is another female Australian performer to whom I’m briefly introduced. She has a beard. The following day I’m in the hotel lift with a bearded person wearing an Akubra hat. For some unknown reason, the presence of this person is making me very uneasy—fight or flight chemicals are circulating in my system. When she says hello, I realise that I’d met her the day before and my tension dissipates. Reflecting later, I understand that it was due to being unable to process two things at once—on the one hand by wearing a masculine hat, she was sufficiently disguised that not only I didn’t recognise her, but I thought she was a man. On the other hand, part of me did recognise her as a woman I’d met yesterday. This experience of cognitive dissonance helped me understand the fear generated by the crossing of boundaries, and even gave me a sense of how it could lead to violence.

Bauman shows how the fear of boundary-crossing triggered by the onset of modernity (as old boundaries keeping strangers and identities secure and well-defined became porous), resulted in both an effort to defend old boundaries, and an attempt to build new boundaries around new identities (p. 34). He finds that the extreme antisemitism that led to the Holocaust was due to Jewish boundary breaking. Having been ghettoised in Europe for centuries, the advent of modernity meant that Jews could now live and dress how they wanted, and some achieved social status. These changes ‘epitomized the awesome scope of social upheaval’ (p. 45). For those who felt threatened by the radical changes, Jews became the principal carriers of their anxieties (pp. 45–46). Jews were so associated with the new instability as to be considered agents of the chaos, actively blurring the boundaries of things which ought to be kept apart (p. 50). Bauman coins the term ‘conceptual Jew’, for the person imagined to embody these fears, as opposed to the Jews people actually knew. His definition clarifies the danger of boundary-crossing:

The conceptual Jew ‘straddled so many different barricades’, labelled alien, vagrant, millionaire, Bolshevik, liberal, capitalist, socialist, indolent pacifist and eternal instigator to wars, resulting in ‘cognitive incongruence’ and the inevitability of ‘boundary conflicts’ (pp. 40–41).6The conceptual Jew was a semantically overloaded entity, comprising and blending meanings which ought to be kept apart, and for this reason a natural adversary of any force concerned with drawing borderlines and keeping them watertight. […] The conceptual Jew performed a function of prime importance; he visualised the horrifying consequences of boundary-transgression, […] he was the prototype and arch-pattern of all nonconformity, heterodoxy, anomaly and aberration. […] The conceptual Jew carried a message; alternative to this order here and now is not another order, but chaos and devastation.(emphasis in original, p. 39)

In the early days of modernity it was commonly predicted that once Jews were offered legal equality their distinctiveness would disappear and they would assimilate into the wider society (p. 44). The fact that this did not wholly happen was resented. Similar predictions and ensuing resentments happened in Australia with Aboriginal peoples’ insistence on their separate identities. This relates to the reasoning used to destroy the Coranderrk mission, (see journal entry above, May 2017). Aboriginal people who also had European heritage were forced out into the general community under a program to destroy their political force by assimilation. Indigenous academic, Tyson Yunkaporta uses the Nazi term ‘final solution’ for this policy, celebrating that it did not work (Yunkaporta 2019, p. 124).

Whereas Aboriginal people are strongly connected to their individual countries, the fact that diasporic Jews, as Hannah Arendt wrote, were a ‘non-national element in a world of growing or existing nations’ (Arendt 1973, p. 22) was the strongest driver of antisemitism. National boundaries did not define them, they undermined the difference between ‘us’ and ‘them’; they were a ‘void’ (Bauman 2000, p. 53).

Therefore, under the new conditions of modernity, a new method of boundary-building was required. Conversion was no escape (p. 59). Bauman defines the philosophical essence of racism: ‘Man is before he acts; nothing he does may change what he is’ (p. 60). He posits that ‘racism is inevitably associated with the strategy of estrangement’—the offending people must either be removed or exterminated (p. 65)—modern genocide’s purpose being the creation of a ‘better’ society (p. 91). The notorious Nuremberg Laws were successful in clarifying exactly who was a Jew, leaving no ‘no-man’s-land’; labelling who was due for annihilation, but reassuring a far greater number of German citizens of their worthiness (p. 125).

The Nazi’s first step of separating Jews into ghettos was very effective. Initially Jewish leaders saw it as a protective measure from harassment and pogroms and as a way to enhance Jewish self-management and culture (Bauman 2000, p. 136). Nazis were successful in soliciting the cooperation of their Jewish victims by continually appealing to their sense of rationality and seeming to offer them choices:

It was because the ultimate objective of the Holocaust operation defied all rational calculation that its success could be built out of the rational actions of its prospective victims (p. 137). […] It appeared that when God wanted to destroy someone, He did not make him mad. He made him rational (p. 142).

In 1935 Rabbi Joachim Prinz of Berlin delivered a moving speech:

The ghetto is the ‘world’. Outside is the ghetto. On the marketplace, in the street, in the public tavern, everywhere is ghetto. And it has a sign. That sign is; neighbourless. Perhaps this has never before happened in the world, and no one knows how long it can be borne; life without a neighbour (p. 123).7

However, Berlin’s non-Jewish residents were mostly unmoved, and did not remark on the disappearance of the Jews as Germans had ‘long since removed them from their hearts and minds’ (p. 124). ‘Loneliness of the victim is not just a matter of his physical separation. It is a function of the togetherness of his tormentors, and his exclusion from this togetherness’ (p. 156). Or, as Moreton-Robinson declares:

The existence of those who are defined as truly human requires the presence of others who are considered less human. The development of the white person’s identity requires that they be defined against other ‘less than human’ beings whose presence enables and reinforces their superiority.(Moreton-Robinson 2004, p. 76)

4. Conclusions

In search of a more positive ending, I would like to provide a contemporary example of artistic ‘togetherness’ across Aboriginal and Jewish cultural boundaries. Melbourne playwright, Elise Hearst, was inspired to write the play, Bright World (James and Hearst 2016b), from a story told by her father, the child of Holocaust survivors. This story, originally researched by Professor Gary Foley (1999), was of the Australian Aborigine’s League, led by Yorta Yorta elder, William Cooper’s 1938 march to Melbourne’s German embassy to protest against Kristallnacht, the most violent Nazi pogrom against Jews thus far,8 and a prelude to the Holocaust. She decided to write about this story in parallel with the story of her grandparents fleeing Vienna during WWII (James and Hearst 2016a). At the first reading of the developing play, Aboriginal actors suggested that the play would work better with an Aboriginal writer to give an authentic voice to Cooper’s side of the story. They suggested Yorta Yorta/Gunaikurnai playwright, Andrea James. Hearst contacted her, not knowing that James was in fact a descendant of Cooper. Over the next year, James and Hearst collaborated, emailing versions of scenes to each other which were then edited.

The finished play is a mélange of scenes about Cooper—his childhood, education and politicisation, formation of the Australian Aborigines League and the drafting of the letter to the German Consulate; scenes focusing on Hearst’s grandfather—his childhood, persecution by the Nazis and escape to Switzerland; and scenes dramatizing the process of writing, misunderstandings and gradual friendship between James and Hearst. In the script these contemporary scenes are glossed ‘Meeting of Minds’.

As one way of publicising the show, James and Hearst participated in a public forum at the Koorie Heritage Trust. Justifying the contemporary scenes, James clarified that, ‘We did not want it to be only historical. Cultures are working out how to live on Aboriginal land, now.’ She explained that the ‘starting point is to find commonality.’ Hearst elaborated on the Jewish experience of ‘otherness’, and making art as a mechanism for coping, an act of defiance which happened even in the concentration camps (James and Hearst 2016c).

The set of Bright World was a school gymnasium complete with a marked-up basketball court, a reference to a scene where James enacts her debutante ball, which are often held in school halls. The other time the court was directly referenced was when an argument between James and Hearst deteriorates into them aggressively throwing basketballs at each other. Otherwise, the hall became a somewhat neutral ‘play’ space upon which all the scenes could be layered, and borders between different times and places could be crossed. The addition of the ‘Meetings of Mind’ scenes (which included projected text message conversations) where James and Hearst played themselves, added a layer of complexity that was effective in making the audience reflect on the issues of racism and mis/understanding between culturally different groups now.

In both its content and form, Bright World provides a fine example of the kind of ethical border crossing I have been investigating in this paper. It tells stories that would seem to be highly divergent—that of a Yorta Yorta boy growing up in country Victoria at a time when children had to hide in order not to be stolen from their families, and of a Jewish couple fleeing Nazi Vienna. It jumps between eras and places, but lands with the two protagonist playwrights discovering how to truly meet each other on Australian country.

Visual artist, Rachel Joy, argues that transformative decolonisation requires a process that allows constant renegotiation that is sensitive to relationships between people and place (Joy 2017a, p. 144). Art can do this by ‘perform[ing] a kind of psychic archaeology in unearthing hidden truths and enabling the imagination of different ways of being’ (Joy 2017b, p. 36). Ideally this art slows the viewer down, enabling the border between themselves and the artwork to become permeable (p. 52), so that they are active participants, allowing themselves to be moved (Joy 2017a, p. 150). This echoes Rose’s precepts for ethical dialogue, quoted at the beginning of this article: recognition that dialogue is always situated, and openness to the destabilisation of one’s own ground (Rose 2004, p. 49).

Towards the end of his book, attempting to articulate a sociological theory of morality, Bauman quotes Dostoyevsky: ‘We are all responsible for all and for all men before all, and I more than all the others’ (cited in Bauman 2000, p. 182). This is another formulation of the illogical stance of the sage before the dead beggar (and God). With this sentiment we are in the utopian (practically humanly impossible) realm where boundaries between people do not exist. However, in telling stories that enact this level of compassion, we can create the space for envisioning emancipatory acts of liberation.

This has been my aim in writing this paper. I have shared my boundary-crossing journey of using a story of suffering I have been aware of since childhood—that of the Jews in the Holocaust—to enhance my understanding of an atrocity that I had little awareness of—the Aboriginal genocide. Taking responsibility to do this connects my personal and familial connection to the suffering of the Holocaust to the suffering of the First Nations in the land I call home. It gestures to the possibility of border crossing as an act of liberation that resides in the acknowledgement of historical injustices and their continued impact on both the beneficiaries and the victims of coloniality in the present.

Funding

This research was conducted as part of my PhD studies at Federation University. I am grateful for the financial support afforded me by a Federation Postgraduate Research Scholarship (FPRS) and RTP Fee-Offset Scholarship through Federation University Australia.

Acknowledgments

Firstly: I would like to thank Rand Hazou for the patient, persistent and perspicacious editorial support he has provided. Acknowledgement is also due to my supervisors, Jill Orr and Angela Campbell, and my interviewees, Andrea James, Elise Hearst and Lenka Vanderboom. Thanks so much to Matthew Martin for allowing me to reproduce his cartoon.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | To provide a little background to my ‘self-education’: At my high school to the only history I learnt was Jewish history. In my early twenties, when I quit my first PhD, I got a job as a field officer in the Northern Territory, setting up administration systems in Aboriginal communities. Spending time in remote communities provided some radical hands-on education, but was not grounded in any understanding of the ongoing impacts of colonisation. When I left this job and went to study theatre in Paris, I so offended a more politically aware British fellow student with my comments about Aboriginal people needing to find a way to deal with Western society, she refused to have anything more to do with me. Later I worked in Namibia and Ghana, where my observations of locals’ relationships with colonisation was complex and varied. (Two examples: Entering the Namibian Department of Education, I experienced hostility that I felt was directly related to my whiteness. Approaching a former slave fort with a Ghanaian student, he said to me proudly, ‘My ancestors were slave traders’). However, it is really the research conducted for my M.A. and recent PhD that has deepened my understandings of what it means to live in a postcolonising society. The work continues—I am currently a research assistant for a project investigating Indigenous truth-telling initiatives in Australia, and am co-directing two theatre shows that have a decolonising focus: Barbary Coast about the personal impacts of Algeria’s war of independence, and 13:12 which explores Senegalese spirituality. |

| 2 | Trying to find a reference for this story, I discover that it is an urban myth: “Did Bono Say Every Time He Clapped a Child in Africa Died?” 2006, https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/bono-of-contention/; accessed on 11 July 2020. |

| 3 | In On the Postcolony, Achille Mbembe writes, ‘as a miraculous act, the act of colonizing is one of the most complete expressions of the specific form of arbitrariness that is the arbitrariness of desire and whim. [… C]olonialism frees the conqueror’s desires from the prison of law, reason, doubt, time, measure. Thus, to have been colonized is, somehow, to have dwelt close to death’ (p. 189). Additionally, he quotes Georges Bataille on the colonised from the standpoint of colonial epistemology: ‘We cannot properly feel ourselves into his nature, no more than into that of a dog’ (p. 190). |

| 4 | This narrative of the Jewish ‘enemy within’ is maintained in contemporary ultra-right wing circles. For example, protestors against the 2017 removal of a Charlottesville statue of a confederate general chanted, ‘Jews will not replace us’ (Peter Mitchell, “To the Far Right, Attacks on Protesters as Enemies of ‘Western Culture’ Are a Gift”, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/jun/10/attacks-protesters-enemies-western-culture-traction-far-right; accessed on 11 June 2020). |

| 5 | On 11 February 2020 in a landmark case, the Australian High court ruled that Aboriginal Australians cannot be considered aliens, wherever they were born, and whatever their citizenship, and cannot be deported (Karp 2020). |

| 6 | Yunkaporta remarks that the ‘European tradition of propaganda in which victims of genocide are portrayed as dangerous animals was […] used to great effect against the Jews, and even our own ‘mob’ here in Australia, who up until half a century ago were often considered animals rather than human citizens (Yunkaporta 2019, p. 136). |

| 7 | Rose quotes Levinas, ‘the justification of the neighbour’s pain is certainly the source of all immorality’ (Levinas in Rose 2004, p. 14). It is curious that Rabbi Prinz could not think of other examples of enforced ‘neighbourlessness’… |

| 8 | In 2018 I participated in a commemorative re-enactment of this march. |

References

- Agamben, Giorgio. 1999. Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive. Translated by Daniel Heller-Roazen. New York: Zo Books. [Google Scholar]

- Anzaldúa, Gloria. 1987. Borderlands/La Frontera. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, Hannah. 1968. Men in Dark Times. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, Hannah. 1973. The Origins of Totalitarianism. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, Hannah. 1987. Collective Responsibility. In Amor Mundi. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, Hannah, and Jens Kroh. 1964. Eichmann in Jerusalem. New York: Viking Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2000. Modernity and the Holocaust. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cansdale, Dominic. 2018. Lost Children, ‘Deplorable Vandalism’ and Picnics at Sisters Rocks, an Unusual Graffiti Hotspot. ABC News. December 18. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-12-18/sisters-rocks-vandalism-lost-children-picnics/10589348 (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 1997. Minority Histories, Subaltern Pasts. Humanities Research 33: 473+475–79. [Google Scholar]

- Chalk, Frank Robert, and Kurt Jonassohn. 1990. The History and Sociology of Genocide: Analyses and Case Studies. Gneuhafen: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, Anthony, and Søren Tinning. 2019. Debating and Defining Borders: Philosophical and Theoretical Perspectives. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Damousi, Joy. 2019. Being Humane: A Contested History. Address Presented at Humanising the Past, Present and Future. Brisbane. November 14. Available online: https://www.humanities.org.au/2019/12/17/being-humane-a-contested-history/ (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- Ferst, Devra. 2010. Auschwitz Edition. Forward. July 14. Available online: https://forward.com/news/israel/129336/i-will-survive-auschwitz-edition/ (accessed on 25 February 2020).

- Foley, Gary. 1999. Australia and the Holocaust: A Koori perspective. In The Power of Whiteness and Other Essays. Aboriginal Studies Occasional Paper. Melbourne: Centre for Indigenous Education, University of Melbourne, pp. 74–87. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Mary. 2008. Some Thoughts about the Philosophical Underpinnings of Aboriginal Worldviews. Australian Humanities Review 3: 105–18. Available online: http://australianhumanitiesreview.org/2008/11/01/some-thoughts-about-the-philosophical-underpinnings-of-aboriginal-worldviews/ (accessed on 20 February 2020). [CrossRef]

- Hand, Sean, ed. 2001. The Levinas Reader. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Hatley, James. 2012. Suffering Witness: The Quandary of Responsibility after the Irreparable. Albany: Suny Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hier, Marvin. 2010. Holocaust: A Huge Word Made Small. LA Times (Los Angeles). June 29. Available online: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2010-jun-29-la-oe-hier-holocaust-overuse-20100629-story.html (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- James, Andrea, and Elise Hearst. 2016a. An Interview with Andrea James and Elise Hearst. Interview by Tara Daniel. [Google Scholar]

- James, Andrea, and Elise Hearst. 2016b. Theatre Works. Melbourne: Bright World. [Google Scholar]

- James, Andrea, and Elise Hearst. 2016c. Making Family Art. Melbourne: Koorie Heritage Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Joy, Rachel. 2017a. Unsettling Occupied Australia. London Journal of Critical Theory 1: 140–53. [Google Scholar]

- Joy, Rachel. 2017b. Being Occupier: A White Australian Visual Art Practice That Engages with the Nature of Belonging to Settler Culture. Ph.D. thesis, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Karp, Paul. 2020. High Court Rules Aboriginal Australians Are Not ‘Aliens’ under the Constitution and Cannot Be Deported. The Guardian. February 11. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/feb/11/high-court-rules-aboriginal-australians-are-not-aliens-under-the-constitution-and-cannot-be-deported (accessed on 12 February 2020).

- Kren, George M., and Leon Rappoport. 1980. The Holocaust and the Crisis of Human Behavior. New York: Holmes & Meier Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Levi, Primo. 2017. The Drowned and the Saved. London: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- McLean, Ian. 2016. Rattling Spears: A History of Indigenous Australian Art. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Mignolo, Walter D. 2012. Local Histories/Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mignolo, Walter D., and Madina V. Tlostanova. 2006. Theorizing from the Borders: Shifting to Geo-and Body-Politics of Knowledge. European Journal of Social Theory 9: 205–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, Catherine June. 2003. An Ethics of Bare Life: Agamben on Witnessing. Review Essay of Giorgio Agamben. Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive. Borderlands E-Journal: New Spaces in the Humanities 2: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, Stephen. 1989. The Book of Job. London: Kyle Cathie. [Google Scholar]

- Moreton-Robinson, Aileen M. 2003. I Still Call Australia Home: Indigenous Belonging and Place in a White Postcolonising Society. In Uprootings/Regroundings: Questions of Home and Migration. Oxford: Berg Publishing, pp. 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Moreton-Robinson, Aileen M. 2004. The Possessive Logic of Patriarchal White Sovereignty: The High Court and the Yorta Yorta Decision. Borderlands e-Journal 3: 2. [Google Scholar]

- Moreton-Robinson, Aileen M. 2007. Epistemic Violence: The Hidden Injuries of Whiteness in Australian Postcolonising Borderlands. In White Matters/Il Bianco in Questione. Rome: Meltemi, pp. 299–312. [Google Scholar]

- Nanni, Giordano, and Andrea James. 2013. Coranderrk: We Will Show the Country. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, Kelly. 2001. Witnessing: Beyond Recognition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ravenscroft, Alison. 2012. The Postcolonial Eye: White Australian Desire and the Visual Field of Race. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Deborah Bird. 1991. Hidden Histories: Black Stories from Victoria River Downs, Humbert River and Wave Hill Stations. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Deborah Bird. 2000. Dingo Makes Us Human: Life and Land in an Australian Aboriginal Culture. Cambridge: CUP Archive. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Deborah Bird. 2001. Aboriginal Life and Death in Australian Settler Nationhood. Aboriginal History 25: 148–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, Deborah Bird. 2004. Reports from a Wild Country: Ethics for Decolonisation. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Deborah Bird. 2011. Wild Dog Dreaming: Love and Extinction. Under the Sign of Nature: Explorations in Ecocriticism. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Deborah Bird. 2012. Multispecies Knots of Ethical Time. Environmental Philosophy 9: 127–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rose, Deborah Bird, and Richard Davis. 2006. Dislocating the Frontier: Essaying the Mystique of the Outback. Canberra: ANU E Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shoah Resource Center. n.d. Muselmann. Available online: https://www.yadvashem.org/odot_pdf/Microsoft%20Word%20-%206474.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2020).

- Stanner, William E. H. 1968. The great Australian silence. After the Dreaming, Boyer Lectures, 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Tatz, Colin Martin. 2003. With Intent to Destroy: Reflecting on Genocide. Canberra: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, David. 1988. The Incarnation of Nambirrirrma. Aboriginal Australians and Christian Missions: Ethnographic and Historical Studies 12: 470–83. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Kath. 1981. My People: A Kath Walker Collection. Brisbane: Jacaranda. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesel, Elie. 1968. A Plea for the Dead. In Legends of Our Time. New York: Avon. [Google Scholar]

- Yunkaporta, Tyson. 2019. Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World. Melbourne: Text Publishing. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).