Abstract

The present paper brings to the fore issues relating to the meaning and construction of ethics in online team communication by exploring the discursive strategies that contribute to the construction of a team’s sense of duty and individual virtuousness. The study relies on a complex toolkit which includes ethnolinguistics, sociolinguistics, discourse and conversation analysis. Data consist of a one-day interaction unit as part of a larger set of real communication exchanges (ca. 34,000) over a time period of six months, observation notes, as well as unstructured interviews. Our empirical analysis has revealed that individual virtuousness and sense of duty are actually interrelated. A virtuous team climate leads team members to share positive perceptions about the team, which in turn increases team commitment. Furthermore, we argue that the blurring of private and professional life not only allows for the enactment of ethic-driven discourse strategies that result in enhanced cooperation and improved team performance, but also for high levels of interconnectivity and improved social interaction. The results of the analysis supplement organisational literature based on ethics-centred observations on the effectiveness of virtual work, and show how a discourse-driven approach can provide tools for further theorisations about the practices and the ecology of digital communication.

1. Introduction

The present paper brings to the fore issues relating to the meaning and construction of ethics in online team communication by exploring the discursive strategies that contribute to the construction of a team’s shared sense of purpose and responsibility.

At the workplace, the use of communication technologies has blurred the boundaries between private life and work life; so-called virtual ‘corporate spaces’ have raised ethical issues for employers, employees and their representatives especially as regards the relationship between the autonomy of workers’ individual lives and the needs of employers to rely on the constant availability of their staff.

As concerns communication, it has been observed that the intrusion of the private life sphere into the workplace has implications for the register used in communication at work, with a predictable shift towards more direct language (Crystal 2011). We suggest that in work team environments, and particularly in situations related to sectors in which the constant availability of employees is implicitly requested, collegial interaction between members not only removes the ethical implications of continuous readiness, but also enhances commitment and individual contributions, leading to more effective teamwork. In building an atmosphere of companionship and cooperation, interactants often negotiate work availability through the use of frames within the context of small talk. We have noted that frames function as intertextual leads that guide members to contextualise teamwork in a special way, thus mitigating the effects of absence from work on those who will have to make up for such absence and helping create opportunities for empathy and interpersonal alignment.

The present study offers an insight into specific discursive situations in which team ethics is created through the interplay of meanings triggered by the use of frames. Through framing, team members share knowledge, repertoires and interests while creating a jocular atmosphere, thus reinforcing the interpersonal bonds that make it possible to balance needs in one’s private life and requirements at work, and between off-work and at-work time and availability.

In the past decade, the pervasiveness of IT tools that allow for immediacy in workplace communication has brought about the need for a new understanding of ethics in the corporate world. In online teamwork, individuals find themselves in a communication network that bypasses online contexts, mixing experiences and ways of being from different sectors of life (Stutzman and Hartzog 2012).

In professional environments, the simultaneous connection to the on- and off-work alters previously defined physical spaces of work and private life (Fiesler et al. 2014; Bargiela-Chiappini 2015). This changes the individual’s perception of what is public and private, of personal space and of the working sphere, thus bringing into discussion topics related to employers’ ethical behaviour and employees’ professional ethics (O’Leary et al. 2017). Yet, if on the one hand, the online workplace lays down the prerequisites for constant availability, on the other hand, it creates the feeling of an open conversation flow, which contributes to building a strong sense of cooperation and companionship.

In research on business ethics, much has been said about how to implement the corporate code of ethics concerning work–life balance, especially in terms of the right of companies to exercise control over the private use of computer-based communication at work (e.g., Gheorghe 2017), how employees’ behaviour may increase distraction and decrease productivity (Koch et al. 2012), and the importance of taking immediate corrective action in response to any unethical conduct (De Cremer and Vandekerckhove 2017). Few studies, however, have so far examined how ethics are actually developed and managed in interaction and, more specifically, how the ethical principles underpinning the collaborative work of a high-performing work team are built, understood and put into practice. In online communication, this implies taking a broader view of ethics and looking beyond the commonly referred to borderline between the private and the work life, and turning the spotlight on the construction of interpersonal relationships, as well as ongoing discursive strategies which are adopted during teamwork.

Throughout fieldwork, we observed that team members were establishing their own codes of trust, personal respect, and professional moral conduct. This contributed to improving collaboration and building that sense of collegiality, on the base of which the efficacy and effectiveness of the team relied. Hummels and De Leede (2000) posit that “the rationale for a strengthened moral awareness and behaviour in a team structure is found in the discretion of the team to regulate its own processes and thereby to foster (or restrict) moral reflexivity as the main criterium for ethical interaction.” (p. 76). Taking the self-regulatory power of ethics as a starting point, we decided to analyse the effects of individual behaviour on the development of collective ethics in discourse at the macro and meso levels.

In order to clarify our analytical approach, we will first define the meaning herewith attached to ethics; second, we will briefly describe the concept of framing in discourse; third, we will analyse the frame complex underpinning the discourse excerpts chosen for analysis and discuss the implications that the negotiation of meanings associated with such frames has on the ethical choices of participants; we will then conclude our study with considerations on the contribution provided by discourse analytical tools to the understanding of ethics in real communication at the workplace.

2. Ethics of Online Teamwork in Business Settings

Teaming requires ethical values. The literature on ethics in the corporate world is extensive and is dominated by principle-based approaches which are often inspired by theories including utilitarianism, Kantian ethics, rights theory, contract theory and justice theory. In business environments, ethics typically involve the imposition of specific standards of moral corporate behaviour and a cohesive set of rules for appropriate action (Ferrell and Gresham 1985). In practice, ethics are understood as being prescriptive, with corporate regulations describing the duties and obligations of individuals towards the organisation and the duties and obligations of the organisation towards its stakeholders. However, influenced by the emerging interest in virtue ethics in moral philosophy, a growing body of literature argues for the necessity of broadening the scope of ethics to include virtues, emotions and relationships (e.g., Kristjánsson 2018; Lindebaum et al. 2017; Segon and Booth 2015; Changwoo and Han 2013). In the workplace, this means seeing ethics beyond the two well-defined concepts of rational judgement underpinning individual decision-making, and external regulation that requires conformity to codes and rules of conduct.

Due to the immediacy of communication and the simultaneous connection to the on- and off-work environments, previously defined regulations on work and private life spaces have been altered (Fiesler et al. 2014) and employees’ sense of duty, moral integrity, and individual virtuousness is brought to the fore (O’Leary et al. 2017).

Research on business ethics has paid little attention to the ways in which interactants frame the boundaries between private and professional roles in online communication, as well as the effects that the negotiation of those boundaries may have on the ethics and conduct of a team.

Although conscious of the fact that ethics is essentially inscrutable, we use the term in relation to Bank’s (2016) concept of ‘situated ethics’ where ‘situated’ implies understanding ethics as being embedded in the socio-cultural context of practice, and responsibility understood in a relational sense. This perspective entails acknowledging and accounting for the internal motivations and emotions of moral agents, considering these not as individual features, but rather as resulting from the relational dynamic between people and the interactional context. In the present paper, we see ethical behaviour as behaving consistently in regards to rules of good conduct, not damaging the other or doing any harm, and supporting or investing in the system (Ferrell and Gresham 1985; Hansen 1992). Against this backdrop, ‘ethos’1 is considered to be referring to virtuousness, what individuals aspire to when they are at their very best. It relates to qualities that allow people to excel (Cameron et al. 2004).

3. Framing in Discourse

Frames are coherent schematizations of experience or unified frameworks of knowledge. According to Fillmore (1985), a frame characterises the background knowledge against which concepts make sense. When interpreting a frame, “it is assumed that linguistically encoded categories presuppose particular structured understandings of beliefs about the world, shared experiences, standard or familiar ways of doing things and ways of seeing things” (p. 230). The interpreter constructs their interpretation of a text by bringing to the ‘blueprint’ a great deal of knowledge, in particular knowledge of the frames which are evoked by or capable of being invoked for the sentence in question, but also including knowledge of the larger communication structure within which the sentence occurs. Fillmore determines that “a frame is invoked when the interpreter, in trying to make sense of a text, is able to assign it an interpretation by situating its content in a semantic pattern that is known independently of the text” (p. 232). In terms of overall discourse structure, a frame is evoked by the text if some linguistic form or pattern is conventionally associated with the frame in question.

The concept of frames is often associated with Bateson (1972). Bateson observed that no move in communication, be it verbal or nonverbal, can be understood without reference to a metacommunicative message. This “metamessage” instructs the receiver on how to interpret the message. While observing monkeys playing at the zoo, Bateson realized that the monkeys could establish a “play frame” and it was only by reference to the metamessage “this is play” that a monkey could understand an aggressive act from another monkey as conveying something different from the hostility that it would clearly denote; in other words, metamessages “framed” the hostile acts as play. Building on Bateson’s notion of frames, Goffman (1974, 1981) used the concept in his investigations of the underlying meanings constructed in social interactions in discourse. Goffman considers frames as fundamentally social and situational, namely “definitions of a situation” that interlocutors establish in interaction (Goffman 1974, p. 10). He observes that what takes place in interaction is usually governed by principles implicitly set by the features of the definitions of a larger situation within which the interaction occurs. For example, a real-life experience is framed differently from a “theatrical performance” and participants deal with what occurs differently.

Central to the understanding of how frames work is the notion of footing or alignment (Goffman 1981). While creating frames, people construct alignments, or footing, between one another (i.e., production format) and between themselves and what is said in the specific communication context (i.e., participation framework). Therefore, “a change in footing implies a change in the alignment we take up to ourselves and the others present as expressed in the way we manage the production or reception of an utterance. [It is] another way of talking about a change in [the] frame for events.” (Goffman 1981, p. 128). Goffman then proposed that changes in footing are a common feature of natural talk and typically language linked. In his analysis of the structural framing underpinning real-life discourse, Goffman turned the spotlight on the central role of language for the analysis of social interaction. He argued that “linguistics provides us with the cues and markers through which such footings become manifest, helping us to find our way to a structural basis for analysing them.” (p. 157). Although the influence of Goffman’s work is pervasive in studies on social interaction, there have been few studies to have applied framing as a linguistic tool of analysis of real discourse produced in online team interactions at the workplace. Using Goffman’s conceptual framework as a starting point, we will analyse the way members of a team realize ethical values in their group work by means of the semantic frames activated through the on- and off-work discourse.

4. Data

The company in which we conducted fieldwork is a food manufacturer that in the five years leading up to this research, doubled its income, and, at present, employs close to 1500 people globally. One of the biggest challenges for the team was ensuring continuous production in several factories in the US and managing communication with the headquarters in Europe. Because of the specificity of the task, and as the complexity of production work rapidly increased, continuous availability became a requisite, often blurring the lines between the private and working life of team members.

The data set, collected through fieldwork over six months, represents more than six thousand exchanges between members of a virtual team operating between two continents and across multiple time zones. Due to space restrictions, we will confine the focus of our analysis to the frames evoked in the exchanges of one day (constituting one Interaction Unit, IU), as part of the larger data. The reason behind the choice of this particular conversation unit is twofold. Firstly, it shows interactional strategies which are recursive in the conversational flow of the group. Secondly, the small-scale description allows for a more detailed analysis of the multi-layered network of frames and related socio-dynamic strategies. Furthermore, it provides an insight into ways in which ethics are co-constructed among team members, as well as how interlocutors socially make sense of individual experiences and create collegiality by means of moral alignment.

The examples at hand refer to instances of small talk frames typically bracketing—as pre-play or post-play—larger frames of job-related conversation topics (Hoffman and Cowan 2008). The IU encompasses 33 communication exchanges occurring between the five team members (Eli, Daisy, Marian, Mark and Damian). One of the members, Damian, is the Chief Communications Manager of the company (hereafter Manager). The raw data start at the very beginning of the work team activity on the virtual platform. During fieldwork, we were able to collect background information through observation (Spradley 1980) and informal and unstructured interviews (Bernard 2002) with the team members and the manager. This provided useful data for understanding the role of the participants and proved necessary for pragmatic interpretation, that is, the series of processes during which members/interactants assign particular conventional acts, i.e., illocutionary force, to each other’s utterances (Van Dijk 1977).

5. Methodology

We used a complex methodological framework which relies on ethnolinguistics, sociolinguistics, discourse, and conversation analysis. Specifically, acknowledging Goffman’s (1974) work on how people behave in interactions and Foucault’s (2003) observations about the construction of the ethical self, we will take a post-constructionist and post-interactionist approach whereby people are seen as interactants-in-discourse and ethics is seen as ongoing action.

The data were collected through fieldwork as non-participants or shadowers. As such, we could actively observe and record behaviour as the conversation was unfolding from both -emic and -etic perspectives, although we were conscious of the difficulties that this implies for the analyst (Czarniawska 2018).

Throughout fieldwork, we observed that while performing the team tasks, members show respect for each other, demonstrate responsibility, commitment and integrity, are trustworthy, and do not damage others. Such behaviour is referred to in the literature as ethical behaviour (Ferrell and Gresham 1985; Hansen 1992; Cameron et al. 2004). However, at the same time, members participate in the making of ethics through ethos-construction processes that the team elicits through interaction.

As discussed above, we refer to team ethics as the good habits or virtues that contribute to the flourishing of team members as individuals and to them taking seriously their responsibility for achieving the purpose of the team (Poff and Michalos 2019). Along a similar line, ethos is considered as being related to virtuousness in the Aristotelian sense, that is the internal values that characterize an individual (MacIntyre 1985; Solomon 1992; Cameron et al. 2004).

The present study is part of an ongoing research project on organisational discourse in which different methodologies are applied for the investigation of various topics related to social interaction in organisational environments.

Although the exchanges analysed in the current work refer to a one-day interactional unit, the knowledge of the context gained by the researcher during the six-month period of participant observation made it possible to gauge the validity of the sample for the purpose at hand.

6. Analysis and Discussion

While the conversation was unfolding, our attention was caught by the participants’ ease in shifting in and out of the ‘virtual’ workplace. This was realised in interaction through the interplay between private-life frames and (project-centred) work-life frames. The resulting effect upon the overall conversation structure is the perception of a ‘univocal online persona’ (Panteli 2004); this is particularly relevant in the private subframes. The intertwining of private and work life results in a complex frame chain based on common knowledge that is shared and experienced in interaction by the collective. We observed that the private life subframes do not divert the members’ focus away from the overall target of the team. Rather, they contribute to the construction of an ecological setting that enables coordination and cooperation among members, factors that lead to team success (see De Freitas et al. 2017).

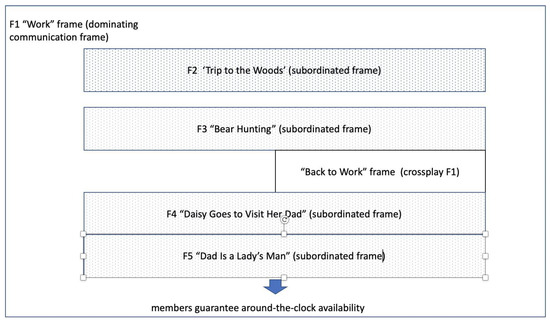

Our understanding is that upon collective framing, members position themselves and create footing (Miron-Spektor and Paletz 2020). After Goffman (1981), the overall framing construction can be illustrated as follows (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Framing construction schemata.

The subordinated communication frames F(2,3,4,5) explicitly refer to off-work life and are evoked in an uninterrupted communication flow within the dominant “Work” frame (F1), thus contributing to the perception of the on- and off-work life spheres as a unified setting. For a better understanding of the setting, we describe below the background events to the “Work” frame (dominant frame).

6.1. Background

“Work” frame (F1). The manager is overworked. Due to the fact that they are in charge of communication services in both local and overseas factories, they have to travel frequently between two continents and manage work over different time zones. Because of this, they need to be able to count on the full-time availability of the team members. For several reasons, they decide to hand over part of the responsibility of the team project to Eli, who is re-organizing the team schedule and the repartition of duties. So far, the team has reached a high level of self-awareness and has a stabilized identity.

Yet, due to the remodelling, the manager has to rely increasingly on the team’s virtuousness, that is, those qualities that allow people to excel (e.g., humanity, integrity, forgiveness, and trust), and are practiced, disseminated, and sustained at both the individual and collective levels (Cameron et al. 2004). It is therefore paramount for the manager and Eli to test team members’ commitment to the new circumstances in terms of their sense of responsibility to each other, as well as to the group’s project, and in representing the organization’s values, among which are fairness and propriety (as stated in the company’s Code of Ethics, article 3).

Furthermore, Eli, in his new position as second team leader, has to re-align with his colleagues. For example, in the days preceding the data exchanges, Eli would often check his peers’ assessment of his role by means of reiterated formulas such as ‘does that kind of scenario make sense to everybody?’.

Within this context, expressions of this type are not read as an attempt to soften or persuade, but rather as a way to make his indications not sound patronizing or overbearing, and at the same time, elicit alignment (i.e., an equitable reading of the roles).

6.2. Analysis

Against this backdrop, we will focus our analysis on manifestations of individual ethos or virtuousness in the interplay between private and work-life frames, and the implications that this may have on the team’s ethics.

Eli launches the communication thread with a reminder of the trip to the woods he will take on workdays (Table 1, F2). This is framed as a personal necessity inserted in a wider frame of family duties (he had promised his family he would devote time to them and go camping), which portrays time off-work and off-platform as morally justifiable. Eli emphasises (through the use of the word ‘excitement’ marked by intensive tone) his emotional involvement in the trip by expressing excitement for the experience.

Table 1.

F2 (“Trip to the Woods” frame).

This has the double effect of minimizing the fact that he will be away from the platform (and the actual work of the team), as well as involving the other members in his personal commitment to family life. Segments (3) and (4) add to the construction of Eli’s ethos. Hard work, perseverance and family commitment are prerequisites to loyalty to the company. An ethical employee owes the company hard work and their best efforts, whether they are at work or off work (O’Higgins and Zsolnai 2018).

The semantics of the “Trip” frame offer a reason for Marian to comment on Eli’s vacation, by evoking a frame that contains a clear moral hint (Table 2).

Table 2.

F3 (“Bear Hunting” frame).

Marian takes the turn with an old hunter’s saying recalling Ralph Waldo Emerson’s quote in Farming (Emerson 1904). The citation evokes the “Bear Hunting” frame, which makes it possible to interpret Marian’s utterance in two ways. The first interpretation: Marian warns Eli about going to the woods when his presence as team leader may be requested. The second interpretation hinges on the moral message, that is, the balance of success and failure.

Furthermore, in the first reading, the message can be perceived as a warning for the group as well: ‘dangers’ are often lurking behind the scenes, that is, in areas outside the team’s control. Moreover, the moral metaphor of the second interpretation can be understood as an encouragement, even a hint to perseverance; the latter being motivated by the fact that Marian is affected by the instantiation of Eli’s ethos; in other words, by his commitment to the endeavour of the team in the preceding frame (Table 1, seg. 4). Thus, Marian responds to Eli’s decision with an alert (6), which is then turned into affectionate advice (7). The mitigator ‘just’ has the effect of minimizing the imposition. In this way, she acknowledges Eli’s effort. Nevertheless, she takes the turn by marking Eli’s willingness to go regardless (So…).

The warning in the second part of the segment softens the effect elicited by ‘so’ and the perception is ultimately of alignment in a tone of camaraderie and companionship rather than a remark.

The previous two frames (Table 1 and Table 2, F2 and F3) allowed for a digression from teamwork to which Daisy promptly reacts, summoning everyone back to work (Table 3, F1). In turn, Daisy’s sense of duty shuns the other members’ willingness to linger in small talk. Daisy takes a stance (8 and 10) which reflects her virtuousness as a responsible and reliable employee as well as her deontological ethics. In doing so, she contributes to the construction of the team’s ethics through the amplifying effect of virtuousness (according to Cameron et al. 2004).

Table 3.

F1 (“Back to Work” frame).

As Sandage and Hill (2001) posit, when people observe virtuousness, they are inspired by it. The manager acknowledges Daisy’s reliability, giving her full responsibility for solving the cash credit issue (11). Daisy’s summoning switches the scene from the conviviality elicited by the “Trip to the Woods” frame back into the semantics of teamwork (i.e., F1).

The “Back to Work” subframe is marked by elements that are semantically dependent on the dominant “Work” frame, such as the request to read the email message and support the connection check. This frame consistently foregrounds the team’s duties (i.e., goals to achieve) while backgrounding off-work topics.

The fact that Daisy will be away on weekdays elicits the manager’s concerns, so he asks her to stay remotely connected regardless. However, the mention of the days off work evokes a frame that leads conversation back to private life. This time the tone gradually shifts from professional conversation in (Table 4, 13) to casual (15,16), with humorous hints at the behaviour as a bon-vivant of Daisy’s dad in spite of his old age. Daisy reacts to the manager’s request promptly with a positive answer but cannot conceal a note of irony and sarcasm in the first segment of turn (15).

Table 4.

F4 (“Daisy Goes to Visit Her Dad” frame).

It seems that Daisy feels that her ethos is threatened by the manager’s request. Daisy’s comment, however, is immediately followed by a statement that provokes sympathy and softens the assertiveness of the previous segment of speech. The use of hedges, i.e., “just” and “even”, and the metonymic phrase expressing affection for her father (i.e., “oldy moldy dad”) indicates her willingness to interrupt the previous tone and drift into a more personal and familiar type of talk. Daisy readjusts the tone of her statement and drops a sarcastic hint (16), which is taken up humorously (17) by the manager and Eli, eliciting the jocular atmosphere of the excerpt that follows (i.e., Table 5).

Table 5.

F5 (“Dad is a Lady’s Man” frame).

The epistemic modality of utterance (16) reveals once more Daisy’s sense of responsibility. The use of epistemic ‘might’ conveys the force of confidence in the possibility, which can be interpreted as a hint to her sense of commitment. The Manager eventually ratifies Daisy’s trustworthiness with his silence (i.e., lack of further reply to Daisy’s statement).

In sum, the manager’s request for availability in off-work time relies on Daisy’s sense of duty. As Cameron et al. (2004) argue, individual virtuousness “eventually serves a buffering function by enhancing the potential for extraordinary performance” (p. 174) of the work group. In organizational practices, ethical behaviour is usually referred to as sense of duty, behaving consistently with the rules, being trustworthy, not damaging others or upholding the system (Rawls [1971] 1999). Frame (4) thus extends the boundaries of Daisy’s ethos to team ethics.

Daisy’s footing sets the tone for the frame that follows (Table 5).

What is interesting for us in the excerpt of Frame 5 (Table 5) is the (re-)alignment among members, especially between Daisy and the manager, brought about by the jocular, casual tone of the conversation about private life.

The “Dad Is A Lady’s Man” frame creates an empathetic atmosphere with sensitive humour on human relations and family ties, giving rise to a relaxed and familiar conversational tone. The footing that the manager establishes in turn (13) of Table 4 is now renegotiated: turn (24) indexes a more local dimension of the manager’s role (see Bucholz and Hall 2005). His utterance marks—both semiotically and lexically—his stance of ineptitude and clumsiness, only softened by the smiley. Through his assertion, the manager positions himself intersubjectively, aligns, and makes his position available to the others. This is in agreement with Kendall’s (2008) claim that “positions are mutually constitutive components of frames. Participants create frames by taking up and maintaining certain positions available to others; and conversely, participants make certain positions available through the frames they create and maintain” (p. 545).

Daisy’s around-the-clock availability functions as a ratifier for the other participants, and a motivation prompt (Table 6). All team members are induced into guaranteeing their remote availability for effective teamwork. For example, Mark strives to ensure his reliable and uninterrupted presence, to which effort Eli replies, offering also to be present: “If you can guestimate when you can the gaps Saturday, Mark. I’ll make sure I am at a place where I can get remote access.”

Table 6.

F 1.

The interactions in Table 7 close the unit, with total availability granted by all co-workers. The mood is relaxed, which builds the premise for a humorous ending note.

Table 7.

F 1.

7. Conclusions

A frame-driven approach to the analysis of the conversation between members of a virtual work team has proved extremely useful in shedding light on the interaction strategies that members deploy to construct team ethics.

We have observed that frames are evoked when participants need to get away from the work environment for private reasons/necessities. We have noted as well that frames allow members to move between on-and off-work states while creating a complex frame chain in which the unifying thread is the team’s univocal persona (Panteli 2004). This gives the impression that private and professional lives are part of a unified setting in which discourses from the two spheres merge.

The interplay between personal and work scenarios has effects on typical features of the social interactional setting, including the language (i.e., preferred familiar register), role perception (i.e., frequent role alignment and negotiation of footing), as well as the way in which ethics is felt and understood. For example, Eli’s two-day trip to the woods or Daisy’s trip to see her dad, which, despite taking place during times of crisis for the team, are perceived as morally justifiable. This is due to effects elicited by the evoked frames on two levels: a—discursive, that is, the emotional involvement triggered by the use of words that index footing and minimize the off-duty event; b—interpersonal, namely, the way in which the sharing of virtuous beliefs and acting (e.g., commitment to family life and respect for the other members) creates a ‘virtuous’ interactional space in which ethos and deontological ethics feed into each other. Thus, not only are Eli’s and Daisy’s days off work felt as permissible and required, but their immediate response to the availability request is perceived by the other members as an opportunity for them to show their sense of duty, reliability, and commitment to the performance goals of the team, for which members hold themselves mutually accountable.

The rehabilitation of virtue concepts in contemporary business ethics (e.g., Audi 2012; Alzola 2015; Tripathy and Sarangi 2017; Sison et al. 2018; Pinto-Garay 2019) has turned the spotlight on an ethics of the individual emphasizing the centrality of motives and emotions, the role of character, and a concern for the whole course of a person’s life (virtue ethics) in contrast to a rule-centred ethics of duty (deontological ethics) creating a principled distance between the two perspectives.

Our empirical analysis of ethics construction in team interactions has revealed that the two concepts of ethics are actually interrelated. A virtuous team climate leads team members to share positive perceptions about the team (e.g., “Boss man! You have an awesome team! (6/7/17); “we got a great team” (6/16/17); “Dream team” (5/7/17)), which in turn increases team commitment. In this way, the team grows more potent, that is, ethical behaviour nurtures integrity and trust within the team, developing positive collaborative spirals, making it more virtuous (Gatti 2016). Team virtuousness creates a sense of duty. This is in line with Stajkovic et al.’s (2009) findings in their meta-analytical studies, which show that team virtuousness has a high impact on team performance. Indeed, Cameron et al. (2011) also suggest that boosting team virtuousness may not only promote team commitment to the organization, but also support team members’ engagement, thus elevating the team’s performance.

Furthermore, on the basis of our findings, we argue that the blurring of private and professional life not only allows for the enactment of ethics-driven discourse strategies that result in enhanced cooperation and improved team performance (Darics and Gatti 2019), but also for high levels of interconnectivity and improved social interaction. In fact, constant availability, although posing the ethical question of how employees’ demands for leisure can be reconciled (see, among others, Reilly et al. 2014), creates a sense of an open conversational environment, which enhances commitment as well as mutual responsibility among team members.

Despite its limitations, which include the small size of the sample, the present study enriches the literature about the construction of team ethics at the discursive level and suggests that virtuousness and a sense of duty nurture each other, thereby developing collective upward/positive spirals. Furthermore, the results of the analysis supplement organisational literature based on ethics-centred observations on the effectiveness of virtual work, and show how a discourse-driven approach can provide tools to further theorisations about the practices and the ecology of digital communication.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Alzola, Miguel. 2015. Virtuous Persons and Virtuous Actions in Business Ethics and Organizational Research. Business Ethics Quarterly 25: 287–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audi, Robert. 2012. Virtue Ethics as a Resource in Business. Business Ethics Quarterly 22: 273–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, Sarah. 2016. Everyday Ethics in Professional Life: Social Work as Ethics Work. Ethics and Social Welfare 10: 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargiela-Chiappini, Francesca. 2015. Foreword. In Digital Business Discourse. Edited by Erika Darics. Basingstoke: Palgrave, pp. ix–xi. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson, Gregory. 1972. Steps to an Ecology: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychology, Evolution and Epistemology. San Francisco: Chandler. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, Russell H. 2002. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 3rd ed. Lenham: Alta Mira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz, Mary, and Kira Hall. 2005. Identity and Interaction: A Sociocultural Linguistic Approach. Discourse Studies 7: 585–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, Kim, Caza Arran, and Brianna Barker. 2004. Ethics and Ethos: The Buffering and Amplifying Effects of Ethical Behavior and Virtuousness. Journal of Business Ethics 52: 169–78. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, Kim, Mora Carlos, Leutcher Trevor, and Margaret Calarco. 2011. Effects of Positive Practices on Organizational Effectiveness. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 47: 266–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changwoo, Jeong, and Hyemin Han. 2013. Exploring the Relationship between Virtue Ethics and Moral Identity. Ethics & Behavior 23: 44–56. [Google Scholar]

- Crystal, David. 2011. Internet Linguistics. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Czarniawska, Barbara. 2018. On Meshworks and Other Complications of Portraying Contemporary Organizing. In Dealing with Expectations and Traditions in Research. Edited by Levi Gårseth-Nesbakk and Frode Mellemvik. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk, pp. 109–27. [Google Scholar]

- Darics, Erika, and Maria Cristina Gatti. 2019. Taking a Team into Being in Online Workplace Collaborations: The Discourse of Virtual Work. Discourse Studies 21: 237–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cremer, David, and Wim Vandekerckhove. 2017. Managing Unethical Behavior in Organizations: The Need for a Behavioral Business Ethics Approach. Journal of Management & Organization 23: 437–55. [Google Scholar]

- De Freites, Julian, Cikara Mina, Grossmann Igor, and Rebecca Schlegel. 2017. Origins of the Belief in Good True Selves. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 21: 634–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, Edward Waldo. 1904. The Complete Works. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin Company. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell, Odies C., and Larry Gresham. 1985. A contingency framework for understanding ethical decision making in marketing. Journal of Marketing 49: 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiesler, Christian, Meckel Miriam, and Giulia Ranzini. 2014. Professional Personae-How Organizational Identification Shapes Online Identity in the Workplace. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 20: 153–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillmore, Charles. 1985. Frames and the Semantics of Understanding. Quaderni di Semantica 6: 222–54. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 2003. Society must be defended: Lectures at the College de France 1975–1976. Translated by David Macey. London: Picador. [Google Scholar]

- Gatti, Maria Cristina. 2016. In Search of Trust: A Model for Trust Construals in Instant Messaging. RILA Rassegna Italiana di Linguistica Applicata 2/3: 173–188. [Google Scholar]

- Gheorghe, Monica. 2017. Considerations on the Conditions under Which the Employer May Monitor their Employees at the Workplace. Juridical Tribune 7: 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Ervin. 1974. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. New York: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Ervin. 1981. Forms of Talk. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Randall. 1992. A Multidimensional Scale for Measuring Business Ethics: A Purification and Refinement. Journal of Business Ethics 11: 523–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, Mary F., and Renée Cowan. 2008. The Meaning of Work/Life: A Corporate Ideology of Work/Life. Communication Quarterly 56: 227–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummels, Harry, and Jan De Leede. 2000. Teamwork and Morality: Comparing Lean Production and Sociotechnology. Journal of Business Ethics 26: 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, Shari. 2008. The Balancing Act: Framing Gendered Parental Identities at Dinnertime. Language in Society 37: 539–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, Hope, Gonzalez Ester, and Dorothy Leidner. 2012. Bridging the Work/social Divide: The Emotional Response to Organizational Social Networking Sites. European Journal of Information Systems 21: 699–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristjánsson, Kristján. 2018. Virtuous Emotions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lindebaum, Dirk, Geddes Deanna, and Yiannis Gabriel. 2017. Moral Emotions and Ethics in Organisations: Introduction to the Special Issue. Journal of Business Ethics 141: 645–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, Alasdair. 1985. After Virtue, 2nd ed. London: Duckworth. [Google Scholar]

- Miron-Spektor, Ella, and Susannah Paletz. 2020. Collective Paradoxical Frames: Managing Tensions in Learning and Innovation. In The Oxford Handbook of Group and Organizational Learning. Edited by Linda Argote and John M. Levine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Higgins, Eleanor, and László Zsolnai, eds. 2018. Progressive Business Models: Creating Sustainable and Pro-Social Enterprise. London: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary, Patrick, Miller Megan, Olive Melissa, and Amanda Kelly. 2017. Blurred Lines: Ethical Implications of Social Media for Behavior Analysts. Behavior Analysis Practice 10: 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Panteli, Niki. 2004. Discursive Articulations of Presence in Virtual Organizing. Information and Organization 14: 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Garay, Javier. 2019. Virtue Ethics in Business: Scale and Scope. Business Ethics (Business and Society 360) 3: 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Poff, Deborah C., and Alex C. Michalos. 2019. Encyclopedia of Business and Professional Ethics. Edited by Poff Debora and Alex Michalos. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Rawls, John. 1999. A Theory of Justice. Revised Edition. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. First published 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly, Nora, Sirgy Joseph, and Allen Gorman, eds. 2014. International Handbooks of Quality-of-life. In Work and Quality of Life: Ethical Practices in Organizations. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Sandage, Steven, and Peter Hill. 2001. The Virtues of Positive Psychology: The Rapprochement and Challenges of the Affirmative Postmodern Perspective. Journal for the Theory of Social Behavior 31: 241–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, Lydia, and Mark Lehrer. 2013. The Conflict of Ethos and Ethics: A Sociological Theory of Business People’s Ethical Values. Journal of Business Ethics 114: 513–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segon, Michael, and Chris Booth. 2015. Virtue: The Missing Ethics Element in Emotional Intelligence. Journal of Business Ethics 128: 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sison, Alejo José, Ferrero Ignacio, and Gregorio Guitán, eds. 2018. Business Ethics: A Virtue Ethics and Common Good Approach. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, Robert. 1992. Corporate Roles, Personal Vitues: An Aristotelian Approach to Business Ethics. Business Ethics Quarterly 2: 317–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spradley, James P. 1980. Participant Observation. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Stajkovic, Alexander D., Lee Dongseop, and Anthony J. Nyberg. 2009. Collective Efficacy, Group Potency, and Group Performance: Meta-analyses of their Relationships, and Test of a Mediation Model. Journal of Applied Psychology 94: 814–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stutzman, Fred, and Woodrow Hartzog. 2012. Obscurity by Design: An Approach to Building Privacy into Social Media. Paper presented at CSCW‘12 Workshop on Reconciling Privacy with Social Media, Seattle, WA, USA, February 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathy, Mitashree, and Itishri Sarangi. 2017. Exercising Concepts of Virtue Ethics in Business Culture. Journal of Business and Management 19: 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, Teun. 1977. Context and Cognition: Knowledge Frames and Speech Act Comprehension. Journal of Pragmatics 1: 211–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | ‘Ethics’ and ‘ethos’ are etymologically and ontologically linked. The word ‘ethics’ derives from the Greek ‘ethos’, which means ‘character’ or ‘customs’. ‘Ethos’ refers to that core set of attitudes, beliefs, and values that gives coherence and identity to a community of people. ‘Ethics’ is seen as both the participation in and the understanding of an ‘ethos’. Hence, the relationship between ethics and ethos is double faceted. On the one hand, ethics presupposes an ethos, i.e., the set of attitudes, beliefs, and values that have played a role in shaping our own moral stance. On the other hand, ethics also transcends ethos, i.e., the reflection that helps us clarify, justify and criticize aspects of the ethos (for more details on ethos and ethics in business settings, see Segal and Lehrer (2013). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).