1. Introduction: A History of the Sanctions

Since the Iranian revolution in 1979, the country’s relationship with the Western world, more specifically the United States, has become soured. This animosity towards the West resulted in devastating economic sanctions against Iran, which indirectly impacted the Iranian art market as well. To understand the impacts on the art market, it is necessary to comprehend the history and the nature of the sanctions and the sectors they target.

The history of the sanctions against Iran goes back to the early months of the revolution when the hostage crisis ended several decades of harmonious relationship between Iran and the United States. In November 1979, President Carter ordered the freezing of Iranian assets in U.S. banks and banned imports from Iran (

O’Sullivan 2003, p. 50). Since that time, every U.S. president has imposed a new sanction against some sectors of Iran’s economy, military, or foreign policy. However, the first comprehensive sanctions targeting the entire Iranian economy were imposed during the Obama administration. As part of these sanctions, several countries worked together on a resolution against Iran’s nuclear program (

Nephew 2017, pp. 70–71). Many of these sanctions persisted until the agreement between Iran and the P5+1

1 was finalized in 2015; however, many remained unchanged even after the deal (

Leal-Arcas 2016, p. 61). In 2016, the election of Donald Trump changed the United States’ political approach towards the deal between the P5+1 and Iran (The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action or JCPOA). The Trump administration set the most systematically intensified sanctions against Iran, which encompassed almost all of the country’s economic and financial activities and blocked any feasible way that Iran can legally or illegally bypass the sanctions.

2 Even though the sanctions do not target the art market, the financial restrictions make any business with Iranian art entities impossible. Furthermore, international art institutions are sensitive as working with Iranian organizations or individuals may put them in risk of losing the more lucrative American market.

2. Domestic Factors

In the late 1990s, a shift in the Iranian political sphere resulted in enormous changes in Iranian art. The rise of reformists in 1997 gave relative freedom to those artists whose works were not aligned with the government’s ideological discourse. Among them were many young artists with no memory of the 1979 Islamic revolution. The reformist president, Mohammad Khatami, entered the elections with the slogan of improving relations with the world: “Dialogue Among Civilizations”.

3 Although unable to avoid the international pressure, Khatami paved the way for major changes in the cultural area domestically, including the development of public and private art galleries and museums, the expansion of educational institutions,

4 and investment in digital network infrastructures and the internet (

Rabasco 2002, p. 118). Notably, such changes were not privileges granted from the leaders, but rather were the result of two decades of struggle by the middle-class Iranians for their social rights.

5After the rise of reformists, the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (TMoCA) began to include independent artists in group exhibitions (

Keshmisrshekan 2013, p. 234). Additionally, the Center of Plastic Arts of Iran (Markaz-I Honar-hay-i Tajasomi Iran) began to support commercial galleries in Tehran and other cities through funding (ibid.). During this time, the TMoCA increased its international activities through connections with other international institutions and museums by holding several shows of Iranian artists in the Western and Asian countries (Ibid., p. 235). After two decades (1979–1997) of isolation, these shows were crucial for Iranian artists, as they introduced contemporary Iranian art to the world. Another significant factor that indirectly affected the Iranian art market was the Tehran Biennial, and more specifically the Islamic World Art Biennial. Regardless of the political and ideological motivations behind such events, the biennials became a forum of intercultural communications between Iranian and international artists and introduced Iranian art to dealers and collectors of Middle Eastern art. Yet the nascent Iranian art market did not shift to an organized and regionally notable market until the late 2000s, when the Western auction houses opened salesrooms and offices in the Middle East.

The expansion of internet use was influential in Iranian artists’ awareness of global art and resulted in the emergence of new forms of arts, such as digital art and video. Young artists’ penchant for new media can also be interpreted as reactions against the dominant currents of traditional art supported by the governmental entities. Thus, the development of new art forms took place in a relatively open political space, yet its rapid growth in the last decade—in an atmosphere of economic and political tension between Iran and the West—cannot be separated from the influence of economic sanctions.

3. Art Galleries and Sanctions

Rapid growth in the number of private art galleries and institutions took place in the mid-2000s. During the last decade, the number of art galleries has significantly increased in Tehran and Dubai. While there are 191 art galleries in Tehran today, the number barely went beyond 20 in the 1990s.

6 In Dubai, similarly, investment in art began in the mid-2000s, when Alserkal Avenue, which was an industrial district, was allocated to contemporary art (

Our Story 2020). Besides the rapid increase in the number of art galleries, the move by Christie’s and other Western auction houses into the Middle Eastern art market changed the structure of the Iranian art scene. Therefore, in the late 2000s, the new market sought massive investments in Iranian art (

Grigor and Moussavi-Aghdam 2019). At this point the sanctions had not yet targeted Iran’s financial system, and the country was considered, as Nephew pointed out, economically a “normal” state for the rest of the world except the United States (

Nephew 2017, p. 65). Consequently, investing in the Iranian art market was free of any possibility of engaging in an illegitimate business. Iranian artists, dealers, and collectors were able to ship their works easily and benefit from the international banking system. In these years, Iranian calligraphy had found its way into the Arab states’ market and profoundly influenced the Middle Eastern art market. For instance, in 2008 at Christie’s’ Dubai, Hossein Zenderoudi’s calligraphy sold for

$1.6 million and Parviz Tanavoli’s sculpture

The Wall for

$2.8 million (

Christie’s 2016). In the early years of the market, the most expensive artworks sold in Dubai were either calligraphy, such as Mohammad Ehsai’s and Zenderoudi’s oeuvres, or influenced by calligraphy, such as Tanavoli’s and Farhad Moshiri’s works.

This situation changed very soon after; in June 2009, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (president 2005–2013) won a disputed presidential election. People, particularly in big cities, challenged the validity of the election and protested it as they believed it was a fraudulent election. The government suppressed the protesters, and many people were killed and arrested. The suppression enacted by the regime was rebuked by the West. Additionally, the decision to appoint a hardliner as the country’s nuclear negotiator in the P5+1 (in order to curb any possibility of reconciliation with the West) brought all the members of the P5+1 together on a resolution against Iran. The new wave of the sanctions imposed by the Obama administration in November 2009 was even more crippling (

Nephew 2017, p. 73). Iran was no longer economically considered a “normal” country, and financial transactions over 40,000 euro were subject to hefty fines for the trade partner (ibid., p. 77).

Under the new sanctions, cooperation between Iranian and Arab states’ art institutions became more difficult. The main challenges that Iranian galleries and artists confronted were (and still are) shipping and bank transactions. Opening branches and offices in Dubai and other global cities did not solve the problem in the long run. Some Iranian galleries opened branches abroad, such as Khak and Etemad galleries in Dubai and Shirin Gallery in New York, to avoid the restrictions, but sanctions thwarted all these efforts. It was not only Iranian galleries that were affected by the sanctions; many galleries in the Arab states in the Persian Gulf, particularly the United Arab Emirates, also had challenges working with their Iranian partners.

According to Rozita Sharafjahan, the owner of Azad Gallery in Tehran, the shipment of art to international destinations has become nearly impossible for Iranian dealers and galleries. These global problems have been augmented by the internal restrictions imposed by Irshad (the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance), which has made the issue of transportation permits difficult for dealers.

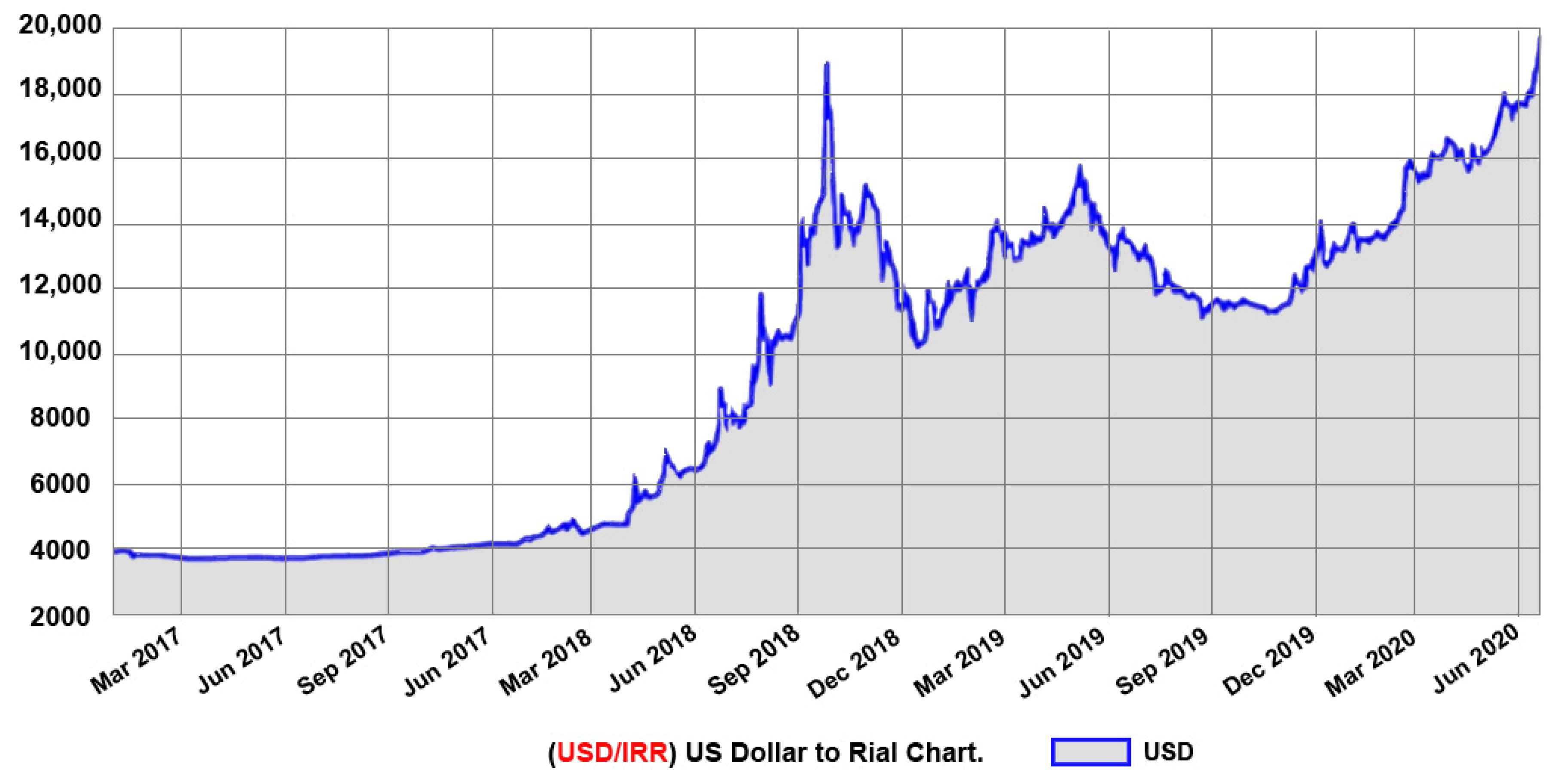

7 As a result, for galleries in Tehran and Dubai, a shift towards digital and video arts and a hybrid of traditional and online marketing became a solution to minimize the impact of the sanctions. Notably, the fall of Iranian currency was another factor that accelerated this shift. Trump’s decision of leaving the P5+1 deal impacted the Iranian currency, as Iran’s rial has depreciated 540 percent since 2017 (

Figure 1). In this case, even if galleries overcome all obstacles, the cost of international shipping is unbearably high. Even though each player in this fluctuating market reacts differently, a general orientation towards new arts and online marketing is visible, at least in Tehran- and Dubai-based galleries working with young Iranian artists. Indeed, besides economic motivations, there are several factors involved with such a shift. Nevertheless, this study focuses on economic rationales and avoids generalizing the statistical results to debunk other influential factors.

4. A Statistical Analysis

This study analyzed statistical data provided from 12 art galleries in Tehran and Dubai (to examine the shift towards less tangible production, exhibition, and marketing). To collect statistical data, this analysis also relied on first-hand experience of attending shows, exhibition catalogues, and gallery websites. For this study, the criteria for selecting art galleries in Dubai were based on their exhibition performances. The focus was on contemporary art, mainly from Iran and other regional states and exhibiting both internationally recognized and emerging artists, and art fair participation. In Tehran, however, galleries rarely work with international artists. Therefore, in selecting Tehran-based galleries, the research focused on their contribution to the Iranian contemporary art scene, through exhibitions, publications, artistic policymaking, and art fair participation as essential factors.

The Dubai-based galleries are Lawrie Shabibi, Ayyam, The Third Line, Leila Heller, Isabelle van den Eynde, and Green Art Galleries. This study investigated the hypothesis that sanctions increase the number of intangible artworks

8. Thus, the selection of Dubai-based galleries for this study helped to evaluate the connection between the sanctions and changes in the galleries’ exhibition policies in the Persian Gulf region.

The Tehran-based galleries are Mah, Azad, Khak, Dastan, Etemad, and Shirin. All six Iranian art galleries were founded after 1997 when reformists came to power. Except for Etemad and Dastan, the galleries are directed and owned by women, which shows that women are playing an active role in the contemporary Iranian art market. Until 2010, galleries in both cities relied on traditional methods of marketing and forms of art (e.g., painting, calligraphy, and sculpture). In this period, the number of exhibitions in Tehran and Dubai focusing on digital and video art was limited. Even though there are not always links between intangible art and intangible marketing, for Iranians who were not easily able to ship their works abroad the links became more inextricable.

Among galleries explored in this study, Azad Gallery in Tehran dedicated more shows to new arts. As mentioned before, in the late 2000s, many galleries in the Middle East, particularly in Iran and the United Arab Emirates, invested in calligraphy and paintings influenced by calligraphy. Iranian artists (mainly the Saqqakhaneh artists)

9 comprised a notable part of this market, but the market was shaken up by the new waves of the sanction. In this period, many Saqqakhaneh artists were not artistically active, if alive. In contrast, the young artists produced energetically, though they were less able to participate in international exhibitions (due to denial of visas, shipping, and insurance complexities). Thus, changing artistic material and technique was a solution to bypass the sanctions as much as possible; as artists and galleries did not need to ship digital arts and videos, the process was feasible electronically. Although financial transaction processing remained a significant issue, a critical part of the problem had been solved. The transition towards less material art forms and online marketing is conspicuous in exhibitions held in many art galleries in Tehran and Dubai between 2009 and 2019. Internet marketing has found its way into the Iranian art market. Besides internationally popular social networks, Iranian galleries and artists use software and apps to market their artworks to local and regional clients, particularly during the sanctions. These strategies, however influential in absorbing local clientele and dual citizen dealers, are less effective internationally as the result of the sanctions.

10A statistical analysis can confirm the validity of this hypothesis, particularly if the number of intangible art exhibitions has increased in the years that the U.S. sanctions have been intensified. The analysis of data shows that in 2009, as expected, all galleries in both Tehran and Dubai exhibited artists working mainly with traditional media, including painting and sculpture.

11 In contrast to Dubai-based galleries, the inclination towards new media among Iranian galleries increased in the early 2010s, but the number of such shows was still insignificant. Sharafjahan emphasizes Iranian dealers’ difficulties in marketing intangible arts. She argues that over the last decade her gallery (Azad Gallery) has sold only around 10 videos and video installations and points out that she has been more successful in marketing digital photographs.

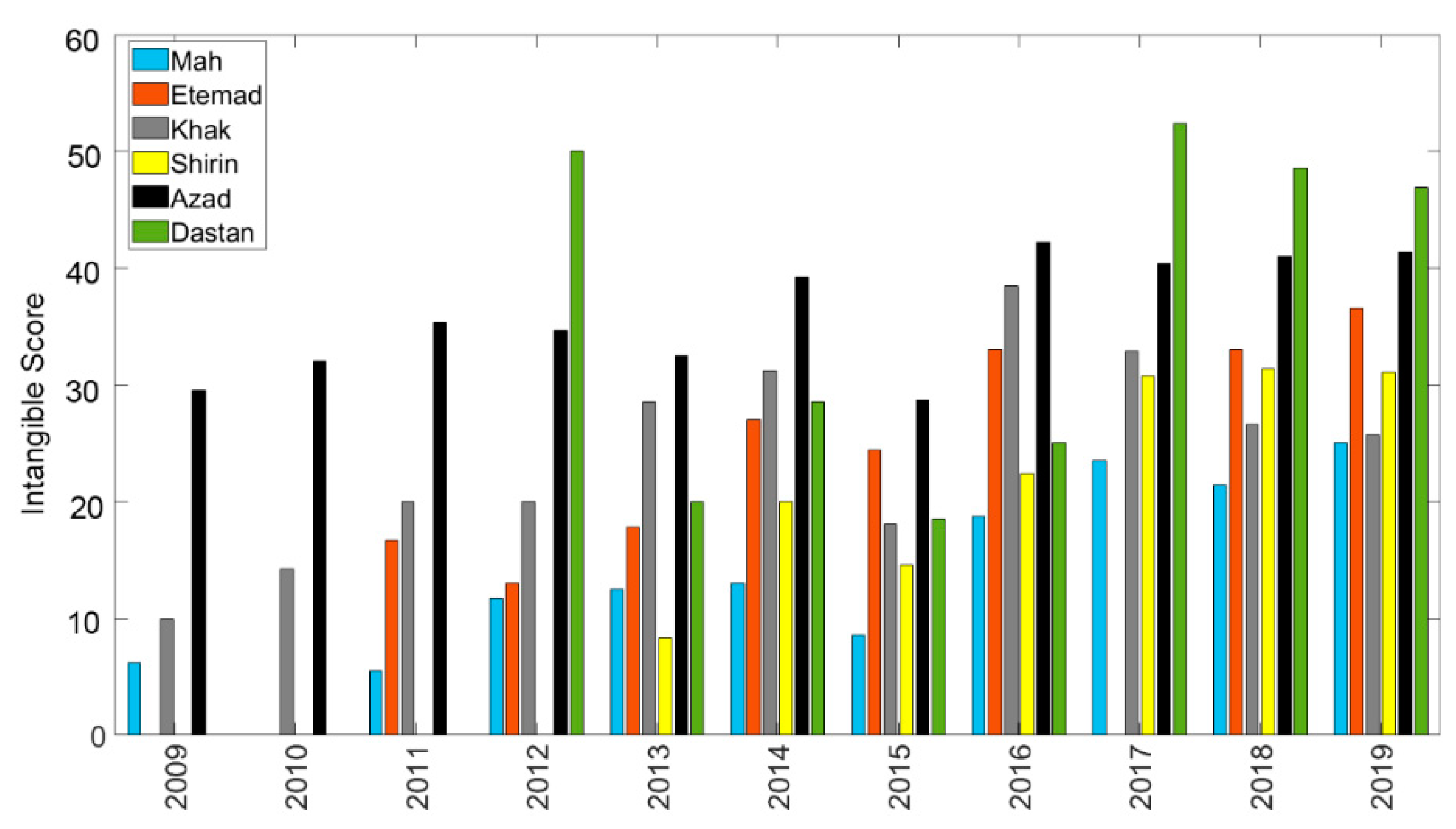

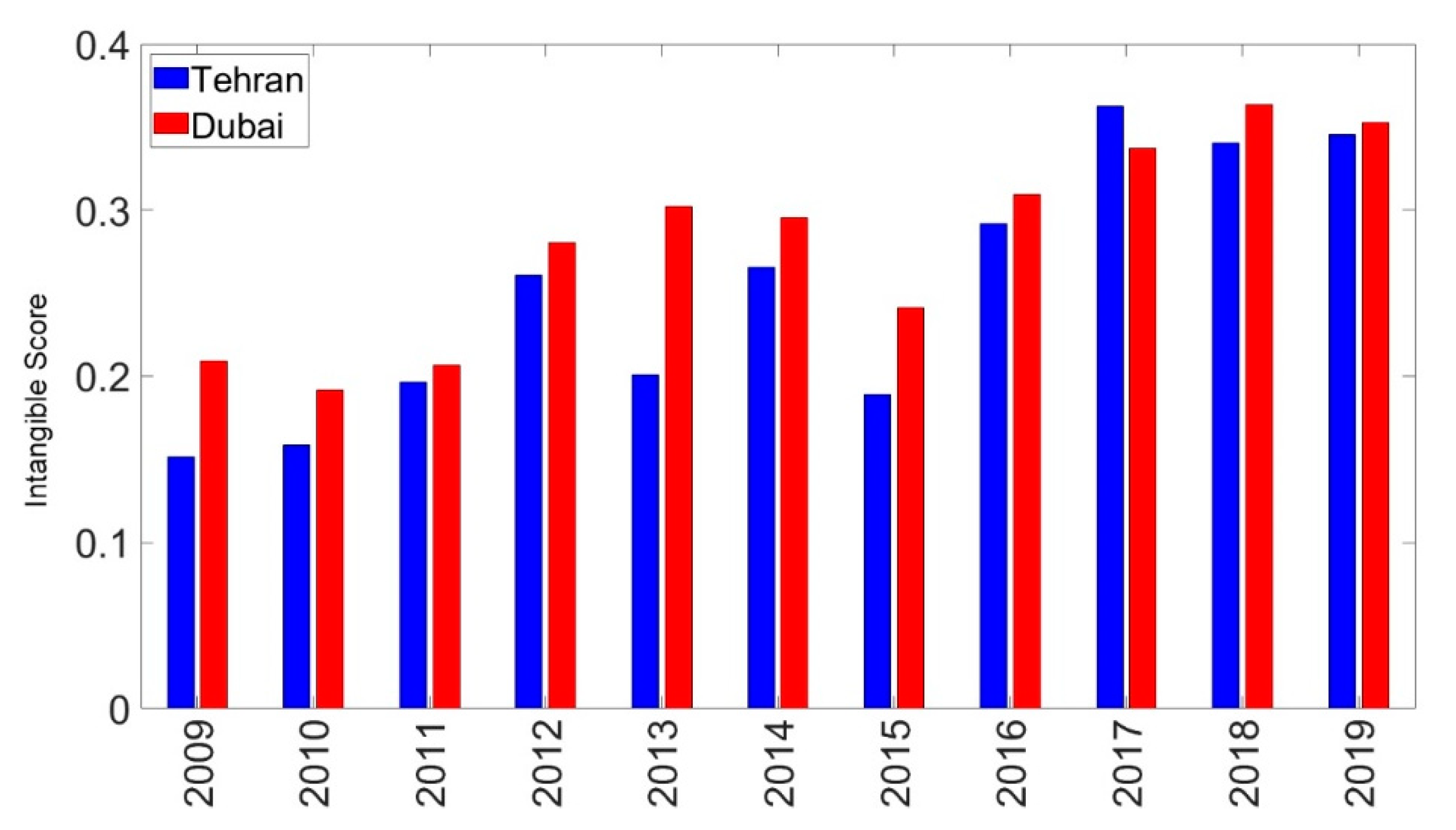

12 Nevertheless, new arts constituted around 30 percent of art shows at Azad Gallery in 2009, while the number was 10 percent for Khak, Etemad, and Shirin galleries, and zero percent for Mah Gallery (

Figure 2).

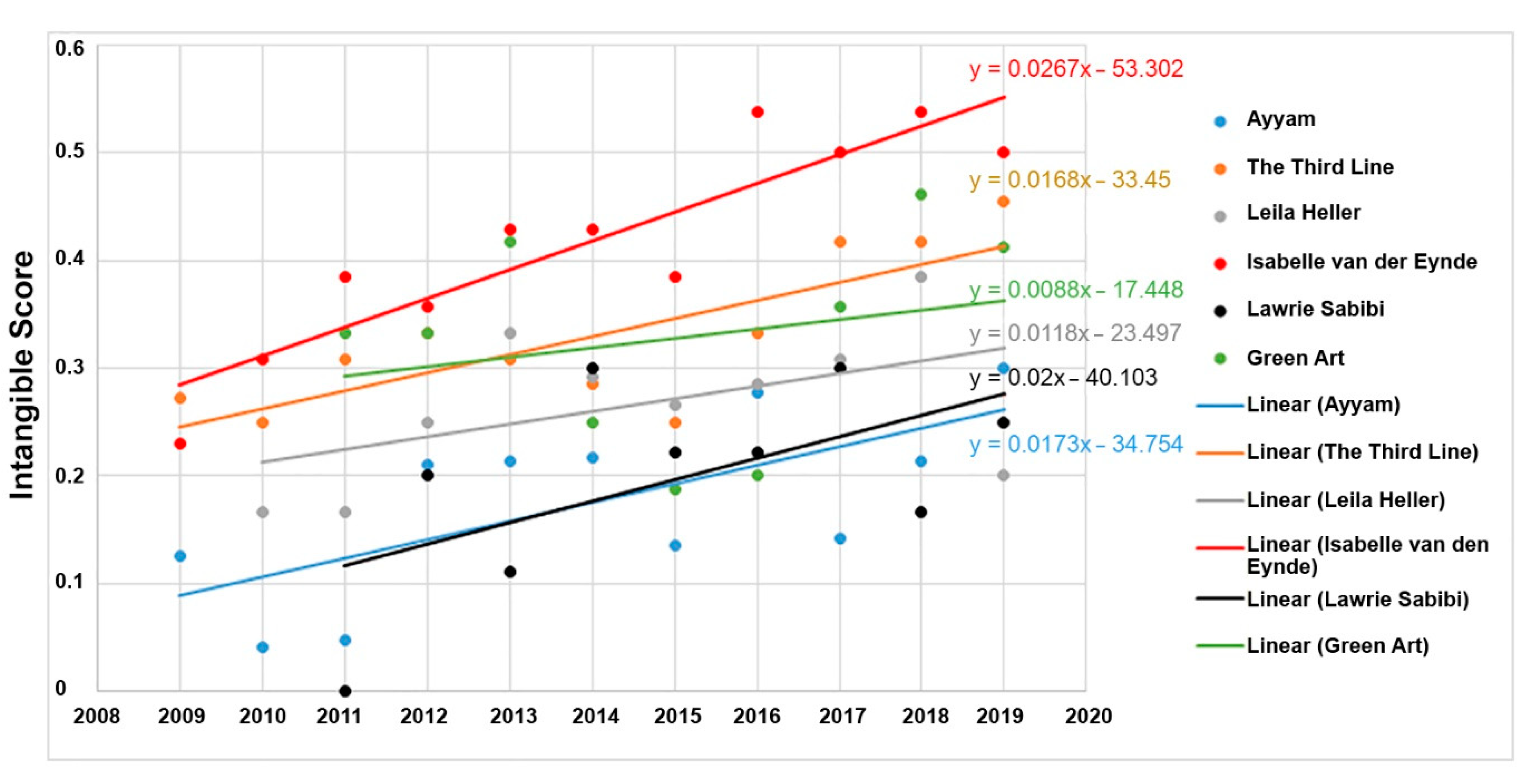

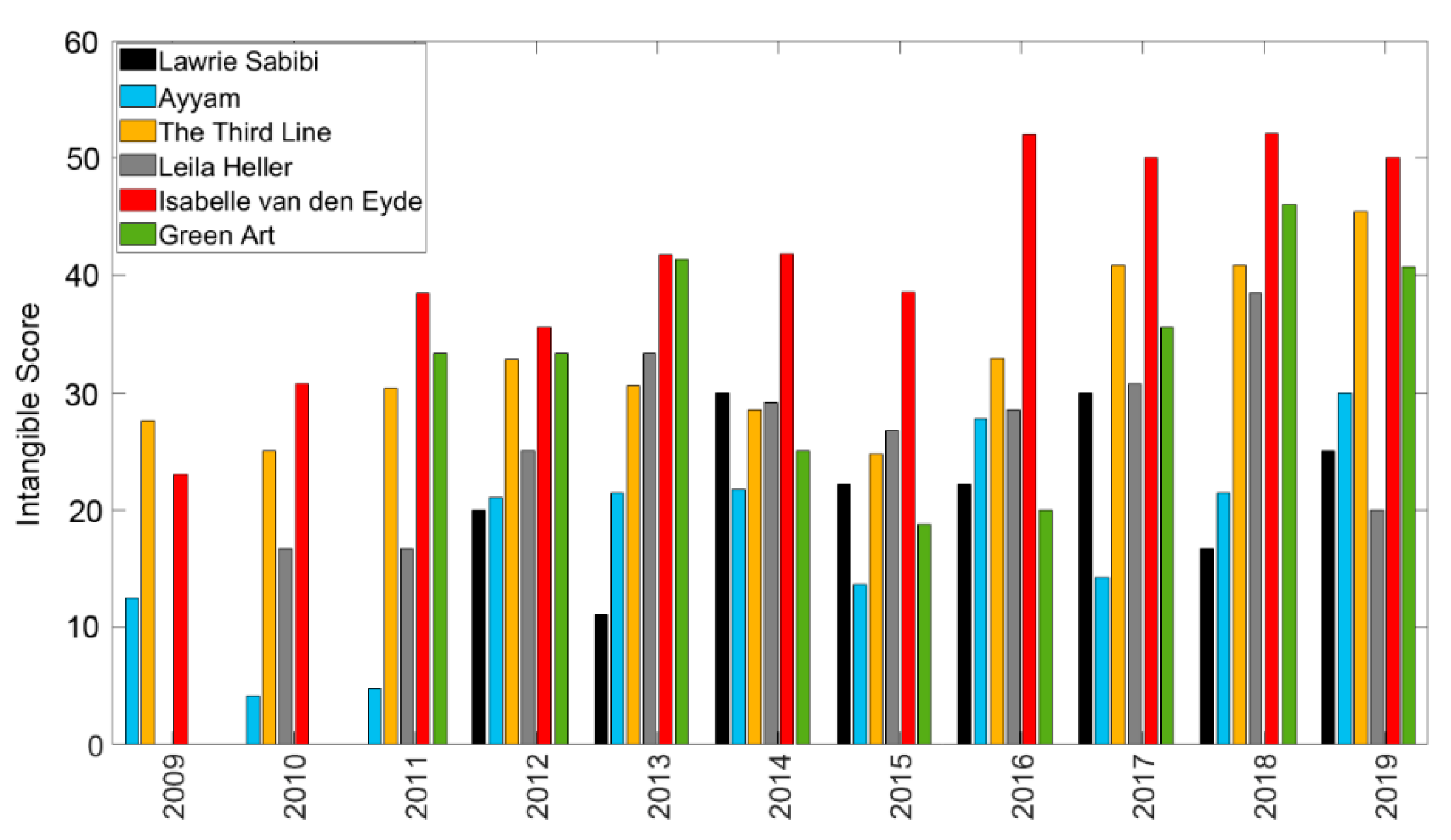

According to the data, since 2010, there has been a gradual increase in presenting new arts in Dubai’s art galleries. The trend lines (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) show the growth at a steady rate for all the galleries, yet there are notable differences between galleries and significant yearly changes. Based on both charts, a sudden shift, particularly in Dubai-based galleries, in presenting new arts is conspicuous in 2016. In Tehran-based galleries, the sudden acceleration in the index of changes occurs in 2016 and 2017, and mostly remains indifferent to the political issues in 2012.

Notably, until 2012, European countries did not follow policies that the United States escalated against Iran. The intensification of the sanction on Iranian people and the economy began in 2012, when, aligned with the United States, European countries became unsympathetic to the inhumane aspects of the sanctions (

Habibi 2014, p. 195). Such political decisions did not make Dubai-based galleries reluctant to continue working with Iranian artists, but had enormous impacts on the shape of their business with Iranians. Dealers in Dubai attempted to maintain their relationship with Iran, an artistically productive society. Changing the modes of marketing and keeping connections with Iranian artists through the digital network were responses to the new economic restrictions. These strategies impacted the artistic forms and media and have engaged the Middle Eastern market in contemporary discourses.

The charts (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) indicate that the scope of changes towards digital arts intensified in 2018 and 2019. In this situation, international galleries have reduced the costs of cooperating with Iranian individuals and organizations. However, the main challenge is still financial transactions; this issue is partially solvable through Iranian galleries and dealers in Dubai. According to the charts, only in 2015 did the number of exhibitions of new art forms decrease in most galleries in Dubai and Tehran. That was the year that the JCPOA was finalized between Iran and the P+1, and the United States lifted the sanctions against Iran. A comparison between the two cities also reveals a notable percentage decline in 2015 in representing new arts in both places (

Figure 6).

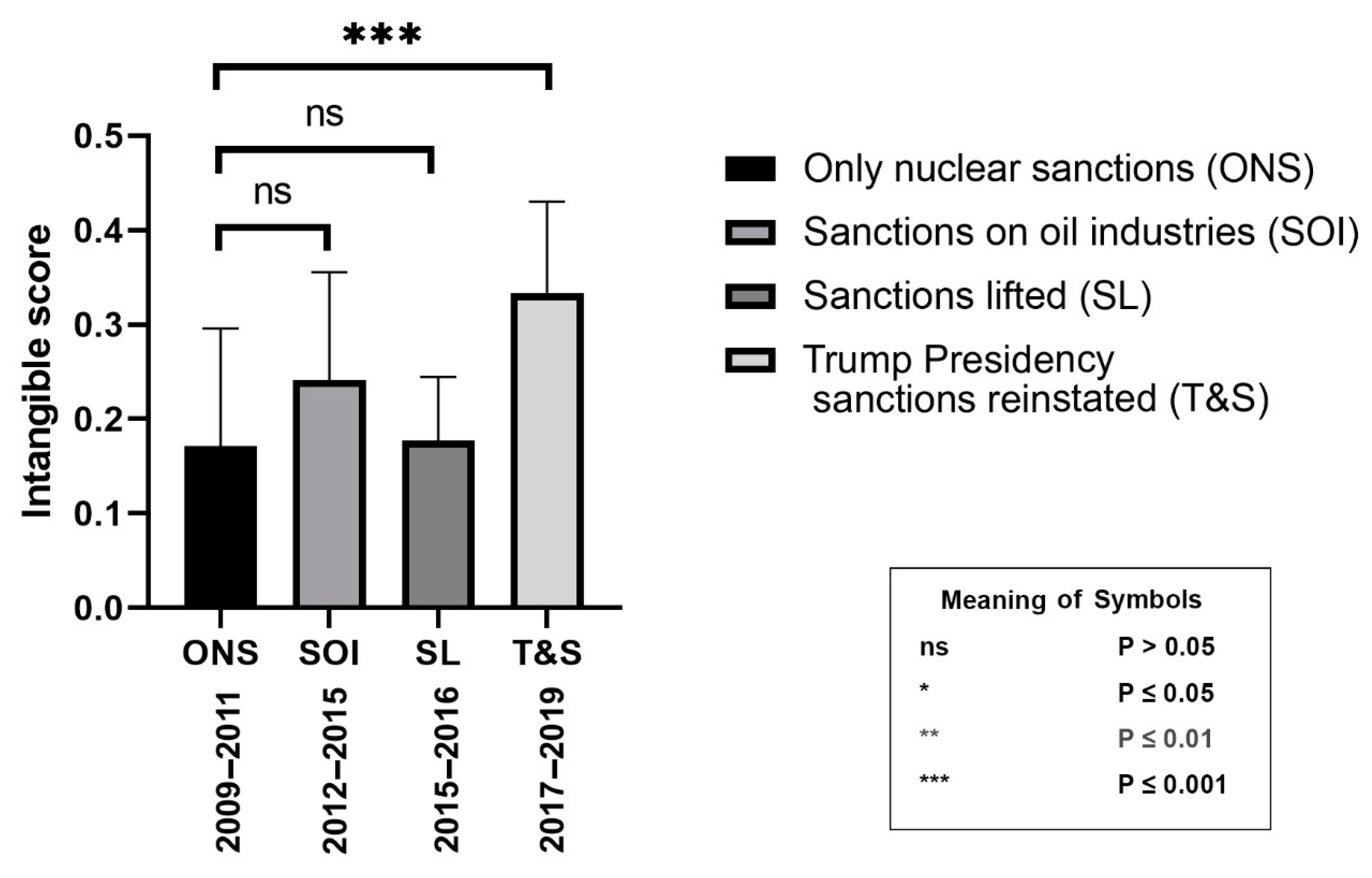

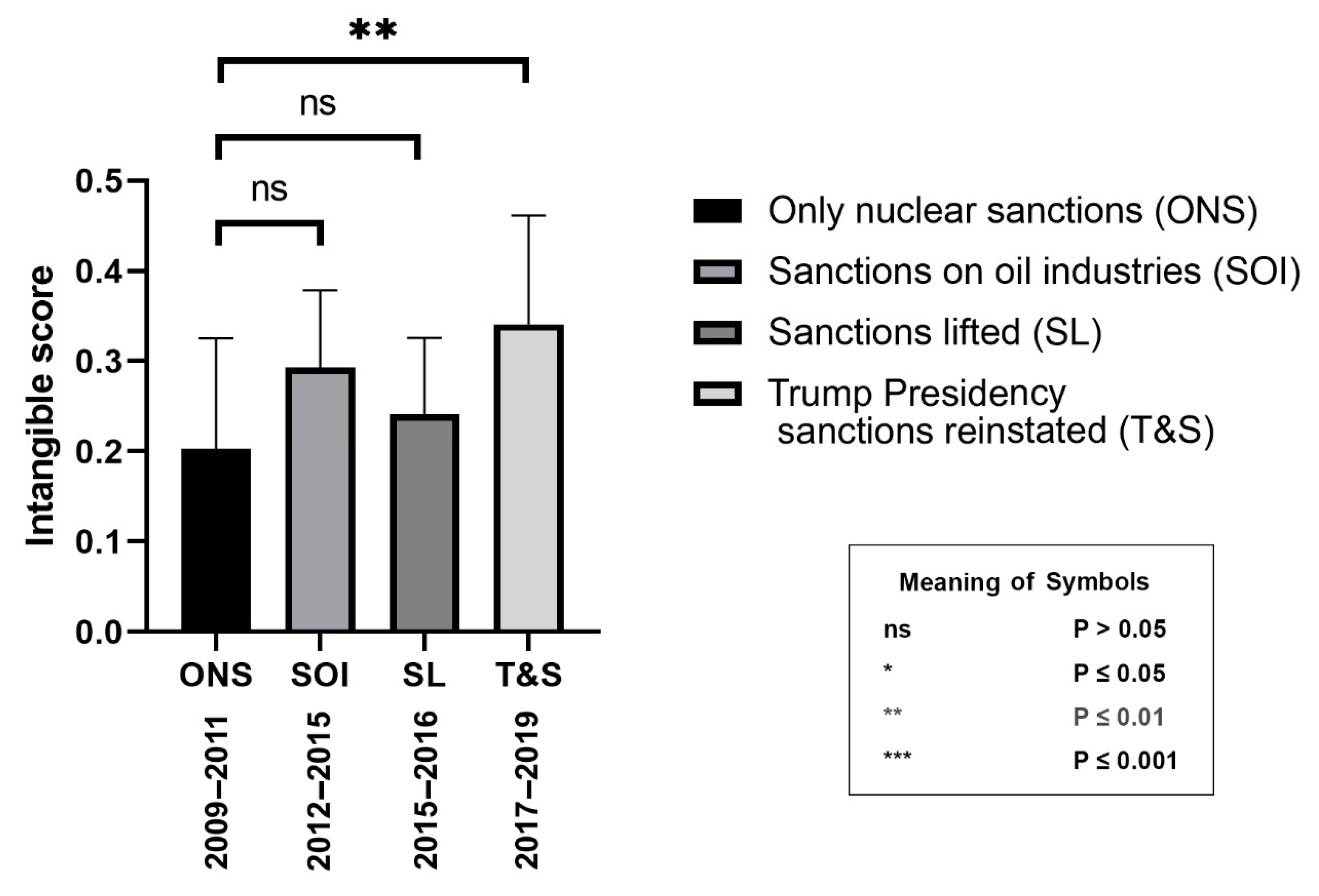

Analyzing the impact of sanctions on the intangible score is applicable through applying an unbalanced ANOVA analysis accompanied by a Dunnett’s multiple comparison test to conduct a treatment versus control hypothesis testing. Since encoding the severity of sanctions into a numerical variable is almost impossible, conducting a regression analysis seems unachievable. Therefore, to overcome the issue, the time interval 2009-2019 was divided based on the changes in the severity of sanctions into four periods:

2009–2011, when sanctions only targeted nuclear activities (ONS);

2012–2014, the United States imposed sanctions against the oil industries (SOI);

2015–2016, Iran and the P+1 finalized the JCPOA, and sanctions were lifted (SL);

2017–2019, Trump became the U.S. president, and sanctions were reinstated (T&S).

This analysis considers the “ONS” stage as the control situation and the next three steps as treatments. In this one-way ANOVA analysis, the four stages are four treatment levels. The intangible scores of galleries are considered as data points.

In this analysis, Tehran and Dubai were analyzed separately. The plots for both Tehran and Dubai galleries (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8) showed an increase in the average intangible score in both SOI and T&S periods when the sanctions were intensified. Therefore, the increase in the intangible score is statistically significant only for the T&S period, when the sanctions targeted all the country’s economic and financial sectors. However, the average intangible score in the SL stage is not significantly different from the ONS period, and this was expected because the sanctions were lifted during the SL stage, causing a decline in the intangible score.

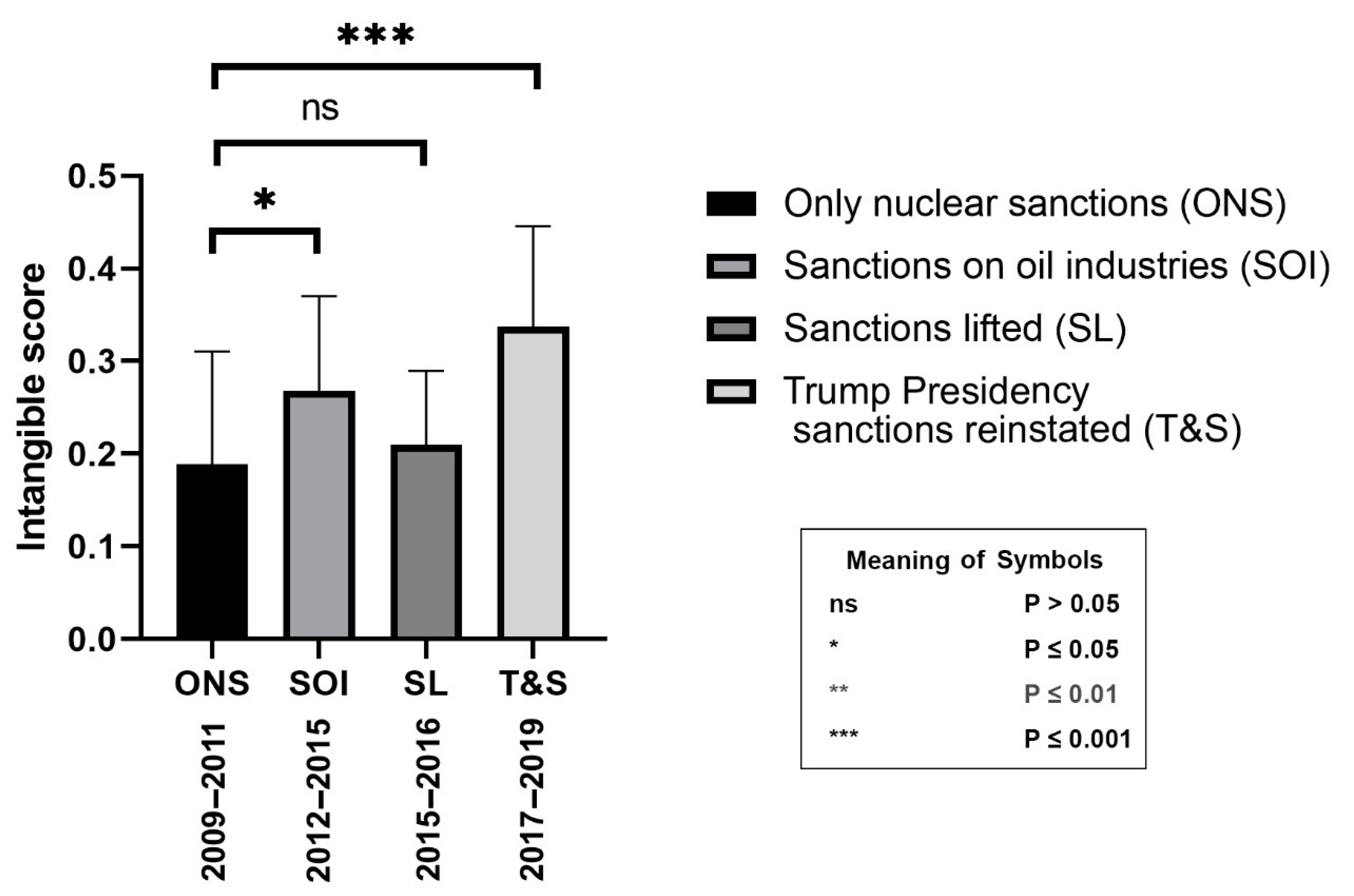

The sparsity of data for ONS and SOI stages, which resulted in a relatively large standard deviation for the intangible scores in both stages, is visible in the error bars in both plots. It seems that such a large standard deviation caused the lack of statistical differentiation in the intangible score for both ONS and SOI stages. Hence, the application of the same statistical analysis on a combination of Tehran’s and Dubai’s data (

Figure 9) was used as solution to overcome this problem. Interestingly, the average intangible score of SOI is significantly different from ONS, proving the hypothesis that the intensification of sanctions increases the intangible score.

5. Sanctions and Uncertainty in the Art Market

Hamid Keshmirshekan, the Iranian art historian, argues that the experiment of the new media and innovative modes of exhibiting is linked with the notion of “contemporaneity,” in which Iranian artists attempt to align their direction with the changes in the global art scene (

Keshmisrshekan 2013, p. 247). Keshmirshekan’s analysis scrupulously considers the shifts in the country’s political sphere in the late 1990s and the early years of the 21st century as well as the impacts of internal politics on contemporary Iranian art. However, the international considerations, such as the United States’ devastating sanctions against Iran, were not explored in his study. Except for a limited number of Iranian artists participating in the regional and international art events, it is almost impossible for the majority of artists and galleries to send their works to international art events.

Furthermore, due to the freefall of the rial (Iran’s currency) in the last two years, the price of artworks has dropped drastically, and has turned the Iranian art market into paradise for dual-citizen collectors and dealers, those who are able to buy works from artists living in the country.

13 The sanctions impelled the international art supplies manufacturers to withdraw from Iran’s market. The scarcity of high-quality art supplies, Iranian artist Meqdad Lorpour argues, has impacted both quality and dimensions of artworks.

14 Lorpour says that the dimensions of paintings exhibited in Tehran’s galleries rarely go beyond 60 inches (Ibid.). It seems that the dramatic rent increase in the housing sectors in the last two years, and art studios as a result, plus the rising cost and scarcity of art materials are influential factors. In this case, despite being aware of low marketability of new arts, many artists tended towards digital art, video, and less material forms of art, which were executable at home, more economical, and globally transferable.

Hence, the economic constraints have caused the formation of a hidden market because domestic dealers are unable to ship art objects abroad, and international dealers and collectors are banned from business with Iranian entities and individuals. In this case, art dealers’ activities become fully engaged with uncertainty. This ambiguity is visible in the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance data on art galleries in Tehran, which does not include the names of the owners of many galleries. Almost all these galleries have been established after 2010, during the intensification of the economic sanctions (

List of Galleries in Tehran Province 2019). Another effect of the sanctions is the migration of many Iranian artists to the Arab States of the Persian Gulf, Europe, and the United States, which reduces the risk of business with Iranians for international dealers. For example, Iranian artists Rokni and Ramin Haerizadeh and Hesam Rahmanian (working with Isabelle van den Eynde Gallery) and Afshin Pirhashemi (the Ayyam Gallery’s artist) have resided in Dubai for the last several years. Recently, art galleries in Dubai rely on a diaspora, who form the main body of the art community in the emirate.

In this situation, many international galleries invested more in the Iranian diaspora, dual citizens, and well-known artists. For example, among the Top 20 Young Artists from North Africa and the Middle East, as named in ArtTactic 2018, five artists are from Iran (

Dewar 2019, pp. 1–20),

15 but only one of them lives in Iran, yet those galleries that did not discontinue showing young Iranian artists had major problems with transfer of money and painting and sculpture works.