1. Introduction

The artist and actor Raida Adon was born in Acre in 1972 to a family that includes members of all the three religions of this region: Muslims, Christians, and Jews. She regards herself as Palestinian, but also as Israeli in every way, and is deeply involved in local art, cinema, and theater. A former model, she studied art at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem between 1999 and 2002 and has acted in critically acclaimed films, plays, and Israeli television series. Since 2001 she has created video works that were presented in galleries and museums in Israel and abroad. Her status as a multidisciplinary artist and celebrity, whose opinions frequently appear in the media, have made Adon a unique figure in the local art scene; unaffiliated with any specific gallery or artistic group, she lives between two worlds that do not generally overlap: the world of theater and cinema, and the world of contemporary visual art (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5).

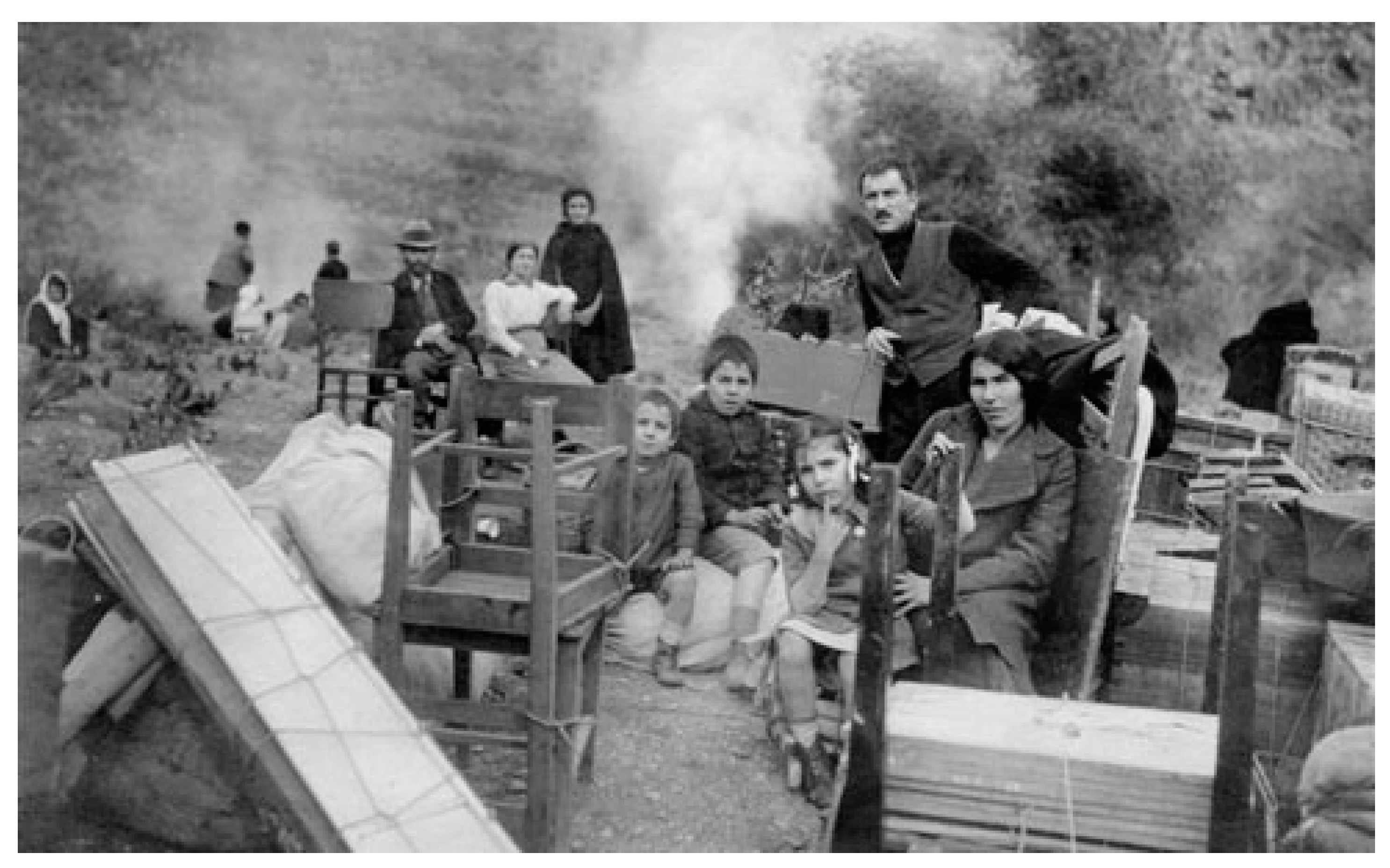

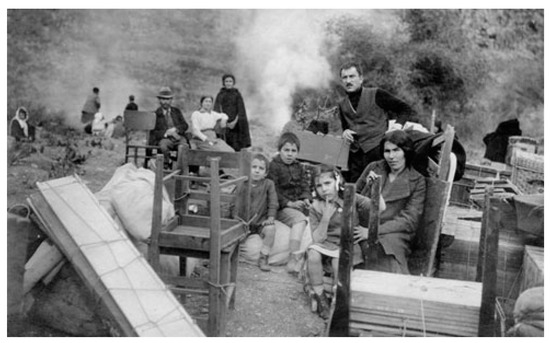

Figure 1.

Jews expelled from Jaffa and Tel Aviv, 1917, The Central Zionist Archives.

Figure 2.

Raida Adon, Strangeness, 2018, Video, 33:30 mins. © Tami Weiss.

Figure 3.

Raida Adon, Strangeness, 2018, Video, 33:30 mins. © Tami Weiss.

Figure 4.

Raida Adon, Strangeness, 2018, Video, 33:30 mins. © Tami Weiss.

Figure 5.

Syrian refugees who fled the city of Raqqa leaving a camp in Ain Issa, Raqqua Governorate, 2017, Reuters News Agency.

“Strangeness”, Adon’s first solo exhibition at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem (curator: Amitai Mendelsohn), and the first monographic show for an Arab artist in what is considered Israel’s national museum, opened on 20 February 2020, some three weeks before the museum had to shut its doors for alomost half a year due to the coronavirus pandemic1. Since then the museum reopened and the public can once again appreciate the exhibition’s visually powerful and poignant message.

The exhibition focuses on the video work Strangeness (2018) and includes a sculptural element that also appears in the video: situated in a suitcase is a doll house, based on Adon’s childhood home. Also on display are preparatory sketches that document the evolution of the video. To a certain extent, Strangeness is a continuation of Adon’s previous video works. Like other works it deals with a personal journey, and with the suffering that yearning for a home entails. In the case of Strangeness, however, there is a clear focus on the state of refugeehood and of being an Other, a stranger. Although this video presents a story with a beginning, a middle, and an end, in essence it follows the artist’s stream of consciousness. It operates on at least two identifiable planes: the collective level of a group of women and men, elderly people and children, who act as a single unit, wandering with their belongings in the local landscape; and the personal level of the artist herself, who always appears alone, walking in various landscapes, staying in empty houses, and lying ill or asleep, beset by nightmares. At the end of the video, she assumes the role of a seer or prophet who foresees the tragic and enigmatic end of the group’s voyage.

Raida Adon’s dramatic and epic video takes its inspiration from many visual references: children’s books, famous paintings, and historic photographs (Mendelsohn 2020). Some of her references stem from Jewish history and art that dealt with wandering and the state of being a refugee, forced to leave their home to an unknown future. A famous example of a (now lost) depiction of Jewish refugees is Galut (Diaspora, 1904) by Polish Jewish artist Shmuel Hirszenberg (1865–1908). The large painting depicts Jews marching in the snow in the middle of nowhere, most likely after a pogrom, carrying their belongings, their future unknown. Adon may not have known this particular painting but it stands for a whole world of references—photographs and paintings—that depict wandering people in search of a home. Similar images can be found in totally different contexts: Palestinian refugees leave their villages in 1948, refugees from Syria walk in the desert with sacks and suitcases after having been forced to leave their home. A photograph taken in 1917 in the (then empty) territory between Jaffa and Tel Aviv tells an interesting and not well known story of Jews that were expelled from Jaffa and Tel Aviv in 1917 by the Ottoman Authorities a few months before the British conquest of the region (Figure 1). Men, women, and children are seated with their belongings outside, some holding their children on their laps, looking at the camera, their future unclear. All these accounts of human tragedy served as inspiration for Adon’s work. For her, the fate of Jewish, Palestinian, Syrian, or any other group of people engender the human state of strangeness and alienation caused by war and violence (Figure 5).

Since 2000 Adon has created a large body of video works. Many of them use religious prototypes from the Christian, Jewish, and Muslim visual worlds (Ankori 2020). In all of them she combines her own experiences with collective symbols and references making them both personal and universal. It seems that in Strangeness, Adon has reached a clear and poignant synthesis of her personal experiences with a strong sense of collective yearning for a home. Although it is based in local landscapes, and its imagery takes its inspiration from the history of the never-ending Israeli–Palestinian conflict, Strangeness soars above the here and now to touch what is human and universal, in a realm where the boundaries between people dissolve and separations fade away. “Someone asked me what I feel in time of war,” she once wrote to a friend. “Where are my emotions and where is my heart? And I ask: Can limits be placed upon the heart? My heart beats constantly and does not stop beating because a Jew has died, or a Palestinian or a European has died ….”

2. The Interview

Your video work Strangeness combines scenes of loneliness, sleep, and dreams, in which you appear on your own, with scenes of a group wandering from place to place with their suitcases and personal belongings until it reaches a tragic and enigmatic end. It seems that all the characters, including yourself, feel like outsiders in perpetual search for a home. Can you tell us how the idea of the work came about? Is it a natural continuation of your earlier works, or are there new elements from more recent years?

This work was born out of the emotions that I felt then and now, my sense of strangeness in Israel and in the world—not necessarily in the political context, but in the sense that we all sometimes feel different from our friends or family. I believe that every work is a continuation of the previous one, and you can see the subject of wandering in almost all my work, as well as the notion of instability and the search for a safe and peaceful place. But in this work I added an element of being alone, not being exactly part of the group. I am observing from afar, watching what will happen, being alone in a suitcase that has become my home (Figure 4).

Can you tell me about your sources of inspiration for the video? There are visual sources here that reference different landmarks in the history of the region, such as the expulsion of the Jews from Jaffa by the Ottomans in 1917, and the expelling of Palestinians by Israeli military forces in 1948. Why was it important for you to incorporate sources representing the narratives of opposing sides of the conflict?

My inspiration came from a photograph I saw on the Internet showing a group of people with suitcases sitting on chairs and looking very aristocratic, but something in their look was empty, sad, restless. I thought they were Palestinians because in my childhood I saw a lot of photographs of aristocratic Palestinians expelled in 1948. Something about the photograph reminded me of my own family, but I was amazed to discover that they were Jews who were expelled from Neveh Zedek in Tel Aviv by the Turks in 1917. They were promised that they would be able to return to their homes and kept their keys in the hope of returning, but they did not return and some died of disease, sorrow, or hunger. It brought me to the story of Palestinian refugees who were also told that they would be able to return, and still hold on to the keys to their homes. It was important to combine both stories because the two stories are so similar. I felt that history repeats itself, and some nations have even disappeared.

What message does your work carry regarding the political situation in Israel and the unresolved conflict here? Does the work deal mainly with the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, or does it deal with issues that are universal?

My work has a very human message in it. I’m not really talking about the Palestinian–Israeli conflict, or about Palestinian refugees specifically, just because I am an Arab woman. This was not my message in this work. I tried to show the world what happens when one conquers land, what happens to the people on the other side who become refugees and who carry all their memories with them, which passes to the next generation in an ongoing cycle. The work begins with the singing of a Romany lullaby—I didn’t choose a Palestinian or an Israeli lullaby. You can’t identify in the film who is Palestinian, who is Israeli, or who is European. I included people from every background and religion in the video, to convey a human message—that my pain is the same as your pain.

Most of us sometimes feel strangeness or not belonging, even if we have a country and a flag. A home is not necessarily a country; a home is security, belonging, calmness. It is a womb that encloses you, and if you don’t feel this in your country, then you feel like a stranger and a refugee, exactly like someone who does not have a country or a flag.

Can you speak about the different people who appear in your work? Are they actors? People you knew? How did you work with them on this project?

The people in the film are not actors and had no experience in front of a camera. Some of them were people I know from my childhood in Acre. I often use people from towns in the periphery, simple people who face daily problems. I make them part of my creation and they become an integral part of it. Working with people who are not actors is wonderful because their faces show something sincere and real; their expressions reveal the difficulties they face in their lives and they can empathize with the feelings I am trying to convey.

Can you speak about your background, and your sense of identity as a Palestinian and Israeli, with a mixed religious identity (Christian, Muslim, and Jewish); your professional life as a well-known theater and television actor; and as an active figure in the field of Israeli and Palestinian art. What experiences have influenced your work as an artist?

Firstly, I never felt like I had a split identity. I was born into two cultures and two peoples and I can take this identity to a place of drama and frustration. I try to look at both identities as enriching—I have two cultures, two languages. I know a lot about both peoples’ customs, foods, holidays, and so on, that the Israelis who live alongside me do not know because of their fear of getting close! I am a Palestinian Arab woman who has acquired no land or material things. I have conquered your language, your culture, and your customs; this is the kind of conquest that I love.

There are moments that are sad because of the inability of people to accept each other. This is what makes me as a human being feel a sense of strangeness and lack of belonging. I come from a home rich in the three religions; each of us chose his own religion and we live together in peace. It shaped my personality and led me to create and learn to accept, listen, and see the other, even if he or she is different from me in their viewpoints and opinions.

There are 13 drawings in the exhibition that look like movie storyboards, but that also stand as artworks in their own right. There is also a small house in the exhibition—a kind of doll’s house—which is a model of your childhood home in Acre. Can you tell me about the creative process that begins with drawings, models, and planning, and ends with the production of the film?

My creative process begins with sketching a storyboard. This is a very important process for me, and I enjoy it very much. It lets me see, hear, and visualize the characters in the scene, build the scenery, and set the location for filming. Without the drawings, there is no roadmap to produce the video work.

During this time that we are all sitting at home because of the coronavirus, the scene in which you are sitting inside the little house gains new meanings. You completely fill the house like Alice in Wonderland, listen to the music you grew up with, read, and sleep. Can you elaborate on the experience of being alone between the walls of your house, which is a place of creation and vitality, but also of anxiety and nightmare?

Indeed, at this time we are all sitting within our own four walls, perhaps I predicted what was going to happen in the world. I feel like I’ve already been immunized; I already know what it’s like to live alone in a little house that on the one hand is beautiful, safe, and comfortable but on the other hand is small and suffocating during the corona lockdown. It is like this country that we live in, which is so beautiful and organized, with its own laws, security, and democracy. But on the other hand, there is a lack of security, peace, tranquility, hidden dictatorship, religious coercion, and an imbalance between peoples, backgrounds, and religions.

The suitcase, and the little house, are also a lot like the world that awaits us. Recently, apart from my feeling of strangeness, I also feel I have a hard time keeping at pace with the world that is moving too fast and not stopping and not always noticing me. I felt that I had no way to protect myself. In my video I asked the actors to look into the camera lens in a way which would make other people stop for a moment.

Hiding in my suitcase let me stop and keep my sanity and humanity. A suitcase can travel anywhere; can belong to anyone; and has no religion, nationality, or color. I am a woman without a home, possessions, or religion. I can be in any country. The suitcase is just like my psyche; it can hold many things that I already hold, whether it is the conflict or religion, or an understanding of the other. The day might come when I will be expelled from my home. Meanwhile, I am a suitcase thrown on top of the closet, and if the time comes, it will carry me somewhere else, perhaps to another country where they may give me another identity without my asking.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Ankori, Gannit. 2020. Raida Adon’s Liminal Spaces of Art: Journeys, Rituals, and Intervisuality. Jerusale: The Israeli Museum of Jerusale, pp. 127–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelsohn, Amitai. 2020. The Weaver of Stories in Raida Adon: Strangeness. Jerusalem: The Israel Museum, pp. 135–28. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The video work was first exhibited in Raida Adon’s solo exhibition “Alienation” in the Walled Off Hotel, Bethlehem in 2019 (curator: Dr. Housni Shehada). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).