Abstract

This article examines three exceptional synagogues designed in Israel in the 1960s and 1970s. It aims to explore the tension between these iconic structures and the artworks integrated into them. The investigation of each case study is comprised of a survey of the architecture and interior design, and of ceremonial objects and Jewish art pieces. Against the backdrop of contemporary international trends, the article distinguishes between adopted styles and genuine (i.e., originally conceived) design processes. The case studies reveal a shared tendency to abstract religious symbolism while formulating a new Jewish-national visual canon.

1. Introduction

The present article explores three exceptional synagogues designed in Israel in the 1960s and 1970s: The central synagogue in Nazareth Illit (1960–1968), the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) officers’ school synagogue in Mitzpe Ramon (1967–1969), and Heichal Yehuda synagogue of the Thessaloniki Community in Tel Aviv (1980). Despite the prevalent nation-building spirit, which advocated a uniform style of Israeli synagogues, the designs of the synagogues under discussion are conspicuously exceptional. Over the years, the synagogues’ unique designs and remarkable technological innovations won them general popularity and favorable reviews in architectural circles. However, the art featured in these synagogues has been overlooked. This study takes a closer look at these synagogues, exploring the interface between their experimental concrete structures and their artworks. It aims to serve as a productive platform for future research into modern synagogue art and architecture in the early State of Israel.1

1.1. The Synagogues’ Exceptional Architecture

The unusual design of the synagogues under discussion is rooted in the circumstances of their construction during the first three decades after the establishment of the State of Israel. An unprecedented number of new synagogues were built in Israel during that period, due to the fast-growing number of new villages and towns. This massive construction gave rise to questions regarding the desired architectural identity of synagogues in Israel. Traditionally, the synagogue had not been bound to any particular historic style (Kampf 1966, p. 27). While biblical sources and Rabbinic literature include strict instructions for the interior design of a synagogue, including the sitting arrangement and the locations of windows and ceremonial objects, there are no architectural guidelines regarding the exterior other than orienting the building in the direction of Jerusalem (Krinsky 1985). Consequently, the most characteristic features of these structures are their contemporary architectural styles, mainly influenced by Brutalism, Structuralism, and Biomorphism. The designers adopted Modern architecture because it held the promise of a fresh start for the young state, and combined practical requirements with expressions of the symbolic purpose of the synagogue (Kampf 1966, pp. 27–28).

The structures’ exceptional appearance reflects the designers’ attitude towards the synagogue as the Jewish house of worship. Many of the synagogue designers were young secular architects and artists, who did not specialize in Jewish art. The synagogues they designed reflected the secular spirit that dominated Israeli culture at that time (Breitberg-Semel 1986). While both architects and artists were attempting to invent a modern national synagogue style, their projects were subsequently criticized for reflecting the embarrassment of secular designers struggling with sacred buildings (Elhanani 1961, p. 1).

From a different perspective, the radical architecture may be understood as an attempt to contend with the biblical precept against figurative images, “Thou shalt not make unto thee a graven image” (Exodus, 20, 3). Historian Lionel Kochan explores the implications of the biblical ban on idolatry for Jewish art. He argues that representations of the human body and architectural designs that are shaped as complete static structures misrepresent the essence of God. In other words, an earthbound edifice cannot represent the ever-changing nature of God. However, incomplete forms that represent the disintegration of space suggest an appropriate path for the Jewish artist (Kochan 1997, pp. 30, 130, 132, 135). In the spirit of Kochan, one could identify the deconstruction of traditional and symbolic forms in the discussed structures as an expression of the dynamic nature of Judaism.2

The use of concrete illustrates the tension between the synagogue’s function as a house of worship and the exceptional design that is its earthbound expression. Although concrete is rarely used in religious art and architecture, this article proposes that it imbues the discussed synagogues with new meanings, allowing the designers to integrate old and new modes of expression. In 1925, architectural historian Lewis Mumford argued that the concrete dome is the most appropriate form for the modern synagogue. In his view, the dome combines historical tradition and modern construction methods (Mumford 1925, p. 232). Moreover, the deployment of rough mundane material in a house of worship calls for a renewed interpretation. Architectural historian Adrian Forty proposes that the construction of modern concrete churches reflects an attempt to redeem concrete from notions that it is a mundane material (Forty 2012, p. 169).

1.2. Contemporary Synagogue Art

One might expect synagogue art to derive from the architectural design of a synagogue (Kampf 1966, p. 26). However, examination of the artifacts in the synagogues under discussion reveals conceptual and stylistic differences between their architecture and artworks. The first major difference between architecture and artwork pertains to their respective religious stances. While the appearance of the structures is manifestly secular, the artworks in the synagogues serve a religious purpose. Other than obeying the precept “worship the Lord in the beauty of holiness” (Psalms 29, 2), synagogue art is also designed to reflect community ideas, values, and goals, and generate a rewarding religious experience.3 The stylistic attributes of the art pieces in the studied synagogues combine didactic religious art with details influenced by major modern art trends.

This article examines its case studies against the backdrop of the synagogue and other Judaica artworks created in Israel in its first decades of independence. The images and symbols used in those artifacts reflect a search for a new Jewish identity in the young state, emphasizing the Jewish historical connection to the country. The new visual canon combines traditional Jewish motifs with modern patterns and imbues old symbols with renewed national meanings. In the first decades after independence, the most prevalent images are those of national icons such as the map of Eretz Israel, the Israeli flag, and Israel’s national emblem, with depictions of nation-building symbols: dancers in folk costumes, the kibbutz, IDF soldiers and Jewish immigrant ships (Kenaan Kedar 2006, pp. 10–11, 34–35; Behroozi Bar Oz 2014, pp. 57–58). In contrast to the period’s Israeli visual canon, the discussed synagogue art features mainly traditional Jewish symbols. This turn towards traditional symbols is associated with a contemporary attempt to illuminate the rebirth of the Jewish nation in Israel as anchored in its ancient history (Shapira 1997, pp. 645–74).

Nevertheless, the synagogue art under examination also echoes major trends in modern Israeli art, and unique representations of the process by which Israeli national identity was consolidated. The Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, established in Jerusalem in 1906, was a pioneering institution for the visual arts in Israel during the 20th century. In their efforts to formulate a distinctive style for the new nation, Bezalel artists blended biblical themes, local landscapes, Jewish symbols, oriental art and European traditions (Zalmona 1998, pp. 48–49). After World War II, local artists renounced Bezalel’s art, instead adopting prevalent international modern styles (Fischer and Manor-Friedman 2008, pp. 9–10). Indeed, the synagogue artworks under examination reflect the adoption of major international contemporary art trends, mainly Purism and abstract art (Ball 1981, p. 231; Kandinsky [1911] 1946, pp. 79–94). These styles were later interpreted as introducing new meanings into Jewish art. Art historian Robert Pincus-Witten argued, for example, that abstract art gave adequate expression to Jewish iconoclastic tradition, in line with the biblical commandment (Pincus-Witten 1976, pp. 55–57).

This article explores the relationships between the discussed synagogues’ architectural design and the Jewish art integrated into them. The key research questions are as follows: what underlying perceptions about the identity of the Israeli synagogue are reflected in the unusual structures? How does the architecture influence the synagogues’ art? Does the synagogue art and architecture under discussion correspond to Pincus-Witten’s definition of “Jewish Abstraction”? Each case study includes an architectural analysis and commentary on selected original art pieces.

2. State of Research

Although quite a few architects and artists were involved in synagogue construction in the State of Israel, the historiography of Israeli synagogue architecture has not yet been comprehensively examined. Numerous scholarly works have investigated ancient, medieval and early modern synagogue architecture,4 and many studies have investigated modern and contemporary synagogues in Europe and the United States.5 In contrast, very few works have been dedicated to synagogues constructed after the establishment of the State of Israel. The historiography of art history includes numerous studies dedicated mainly to synagogue art and ceremonial objects,6 along with an in-depth investigation of Israeli art during the period under discussion.7

The existing literature dedicated to Israeli synagogue architecture includes anthologies published by government institutions to guide Israeli synagogue designers. One such example is an anthology published by the Ministry of Religious Services in 1955. The publication included a comprehensive study of synagogue history, Jewish worship practices, and the traditional and new functions of the synagogue. Significantly, the study included an investigation of synagogue design (HaCohen 1955).

The most comprehensive work dedicated to synagogue architecture in the State of Israel was written by architectural historian Amiram Harlap (1985). The book offers an historical analysis of synagogues constructed in the Land of Israel from ancient history to the contemporary world, and points out the major trends in each period. Harlap maintains that the synagogues discussed in this article mirror Jewish symbols and ideas.

In my book chapter “The Modern Israeli Synagogue as an Experiment in Jewish Tradition” (Simhony 2019), I examine the exceptional designs of the synagogues discussed in this article. The paper explores the tension between the unusual designs and ways in which delegates of prominent state institutions (including rabbis, mayors and government representatives) attributed symbolic connotations to these designs. I argue that those symbolic interpretations, which attributed religious meanings to the designs, were in line with contemporary national ideology and contributed to the buildings’ later reception as canonical Israeli synagogues.

The exhibition Concrete Folklore: Experimental Architecture in Israeli Synagogues in the 1960s and 1970s, which I co-curated in 2018, was dedicated to an exploration of the architecture, ceremonial objects and Jewish art articles of five unique synagogues, including the three case studies featured in this article. In my curatorial article, I maintain that the radical architecture revitalizes previous synagogue design traditions, thus contributing to the shaping of Israeli synagogue architectural identity (Simhony 2018). The documentary photographs and three artworks by Eli Singalovski included in this article were all displayed in the exhibition.

The present article explores these structures from a different perspective, that of the fusion between synagogue art and architecture. Specifically, I analyze the tension between synagogue design that functions as ceremonial art and the integration of artworks into synagogue structures. The questions explored are: did the exceptional architecture leave room for originality in the artworks? Is the nature of the artworks governed by the architecture of the synagogue, and do they introduce new meanings into the overall synagogue design? By so doing, the article proposes a pioneering iconographic analysis of Israeli synagogue art and architecture, revealing a blend of expressions given to traditional Jewish symbols and to the visual canon formulated in Israel’s first decades of Statehood. Ultimately, the article aims to present a complex picture that reflects the dialectic behind the formation of a Jewish–Israeli style.

3. Case Studies

3.1. The Central Synagogue, Nazareth Illit. Architect: Nahum Zolotov (1960–1968)

Capacity: Main prayer hall—400 seats; women’s section—250 seats; secondary hall—30 seats. Prayer style: Sephardic.

Construction: Michael Horowitz, Ami Buch; Interior design and lighting: Yosef Mushli; Ceremonial objects and Jewish art: David Alaluf, Moshe Sternschuss, and Ruth Tzarfati.

Nazareth Illit (Upper Nazareth) was founded in 1956 next to the old city of Nazareth as a Jewish development town, and was part of a state policy to settle Jews in the Galilee.8 In 1957, a process for designing its central synagogue was begun. Initially, the purpose of the project was to strengthen the Jewish presence in Nazareth Illit by constructing a prominent synagogue to stand out against Nazareth’s churches and mosques. Later, this purpose was moderated, and the synagogue’s distinct appearance was described as prominent yet modest.9

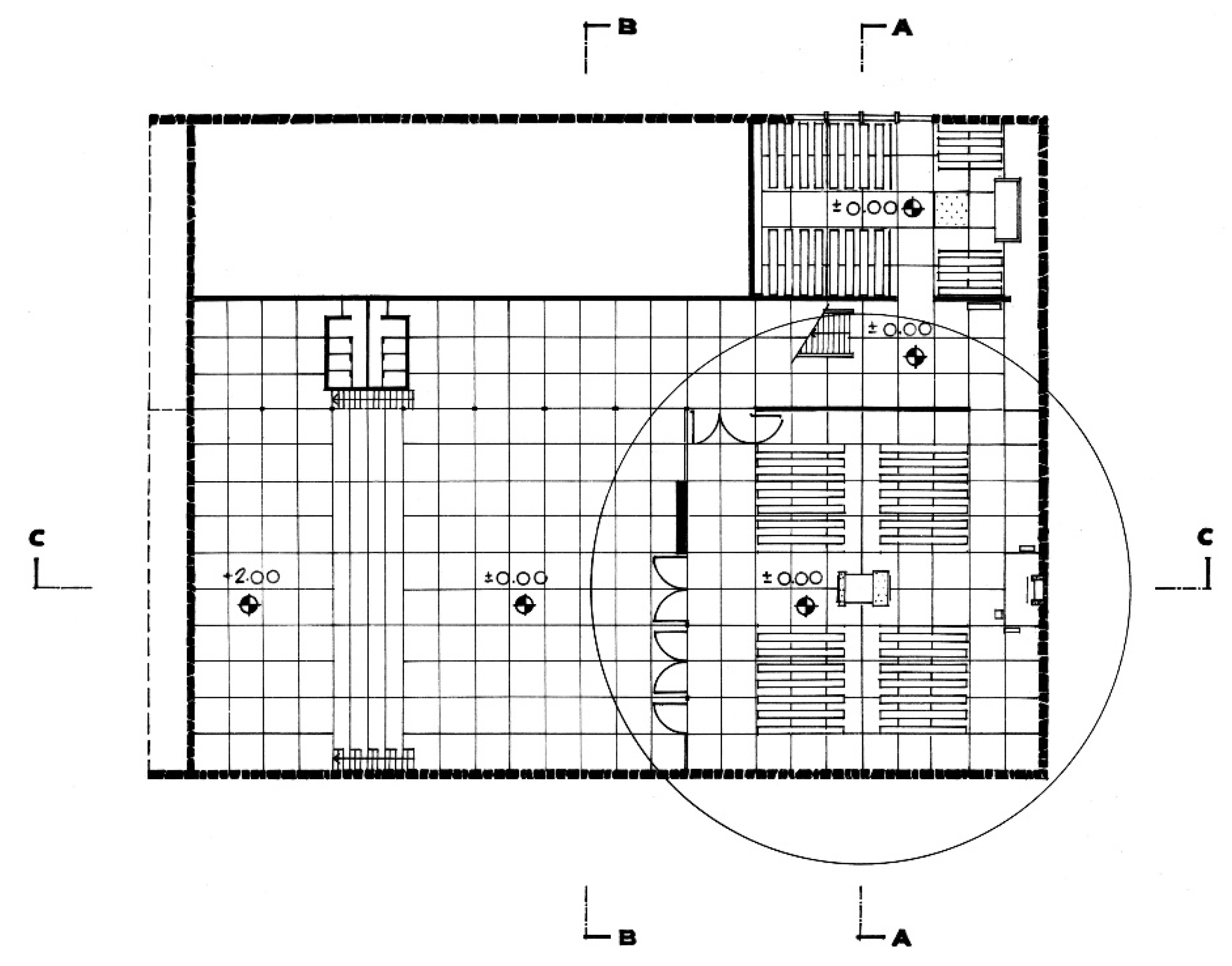

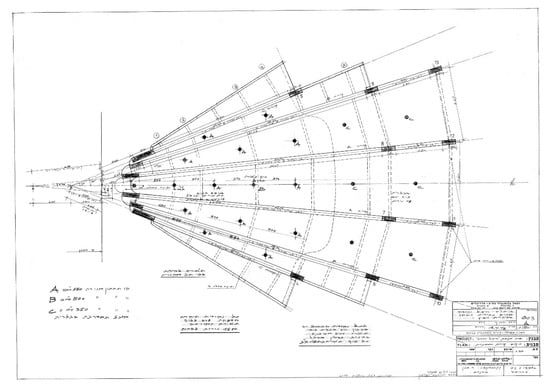

The synagogue was designed for two types of worshippers: the local religious community, whose members gather for prayer in the small hall on weekdays and Shabbat, and a larger crowd of worshippers, who gather for prayer during the High Holidays and other major Jewish festivals (Amir 2011). On those occasions, the worshippers use the main prayer hall and the lower courtyard situated next to it (Figure 1).10

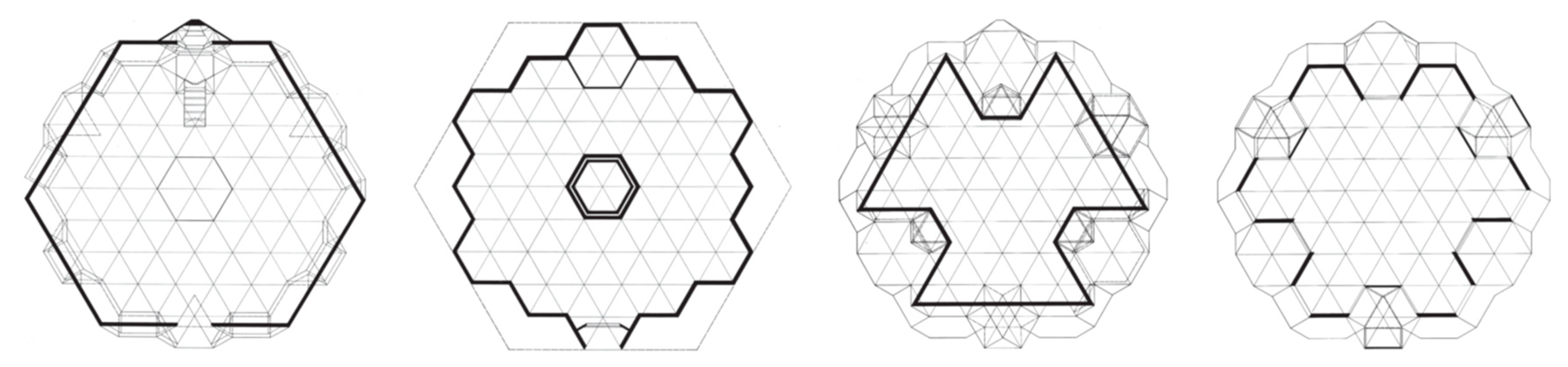

Figure 1.

The Central Synagogue, Nazareth Illit, architect Nahum Zolotov, 1968. Plan. Courtesy of the Azrieli Architecture Archive, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Nahum Zolotov Collection.

Architect Nahum Zolotov won the project in an architectural competition for the synagogue’s design in 1960. The structure is composed of a rectangular building with an inverted dome on top (Figure 2). In accordance with the competition’s specifications, simple building materials were used. The walls are made of reddish earth-colored local stone; the inverted dome is made of exposed concrete, and the courtyard floors are made of concrete-bonded gravel (Amir 2011, p. 30).

Figure 2.

The Central Synagogue, Nazareth Illit. Architect: Nahum Zolotov, 1968. Photo: Eli Singalovski, 2018. Used with permission.

The most dominant feature of the building is the inverted concrete dome that covers the main prayer hall and draws a contrast between the synagogue and the convex contour of the hill on which it is built, giving it considerable prominence. Zolotov declared he had worked out the design scheme after visiting the site for the first time. From an aerial view, the building seems to be sunk into the ground: “I chose … to reveal only the inverse dome, which is antithetical to the dome-shaped naked hill. Above the convex hill, the synagogue’s dome would have disappeared.”11 In addition to the environmental consideration, the inverted dome design meets the acoustic requirements of a place of worship.

The synagogue’s design corresponds to the European and Middle Eastern tradition of dome construction in sacred architecture. The modern interpretation of the domed structure features the use of raw concrete, the inverted shape, and the planting of the building mass into the hill. The most striking inspiration for the synagogue’s design seems to be Le Corbusier’s Notre Dame du Haut Chapel in Ronchamp, France, completed in 1955 (Curtis 1982, pp. 271–81). Both buildings stand on hilltops and feature an expressive upturned roof, whose shell is separated from the building’s envelope. Yet the synagogue’s design appears conservative compared to the expressionist design of the chapel.

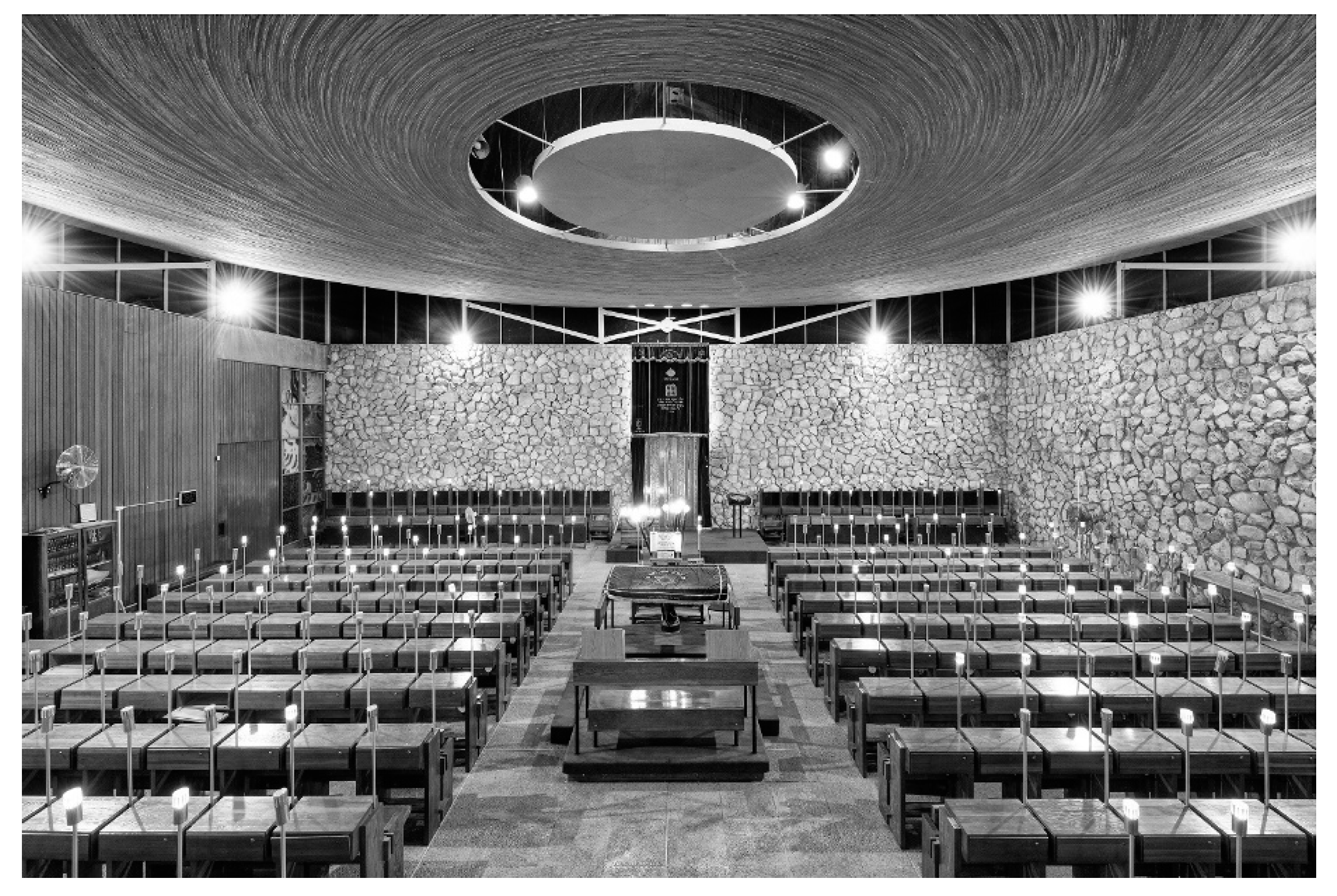

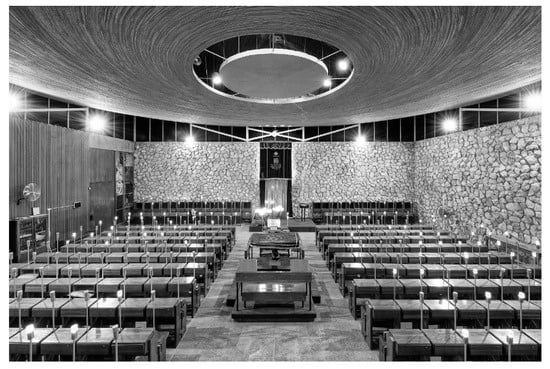

Supported by a slender steel frame, the massive concrete dome hangs above the main hall. A long ribbon window runs the length of the dome circumference, separating it from the bearing walls and creating the illusion of a floating dome (Figure 3). Structural engineer Michael Horowitz notes that the dome is made of two units: a wide concave dome that defines the shape of the building’s roof and a smaller convex dome that nestles within it and reinforces it. Together, the two domes form a triangular beam that transfers the concrete dome’s weight onto steel pillars placed along the building’s square envelope, as well as onto a massive concrete bearing-wall (Amir 2011).

Figure 3.

The Central Synagogue, Nazareth Illit. Interior view facing the bimah and the Torah Ark. Eli Singalovski, Nazareth Illit #1, 2018. Archival pigment print, 100 cm × 67 cm. Used with permission.

Nahum Zolotov (1926–2014) was a prominent Israeli architect. His work mainly includes public and residential buildings, representing his functional approach. His buildings epitomize the adoption of Brutalism by contemporary Israeli architects (Efrat 2004, pp. 189–95). While Zolotov was not a religious man, his non-conventional synagogue designs were meant to create an atmosphere of holiness.12 When asked if he believed in God, he laughed and shook his head, but then said, “I do have faith, and I believe God enters each one of my synagogues.”13

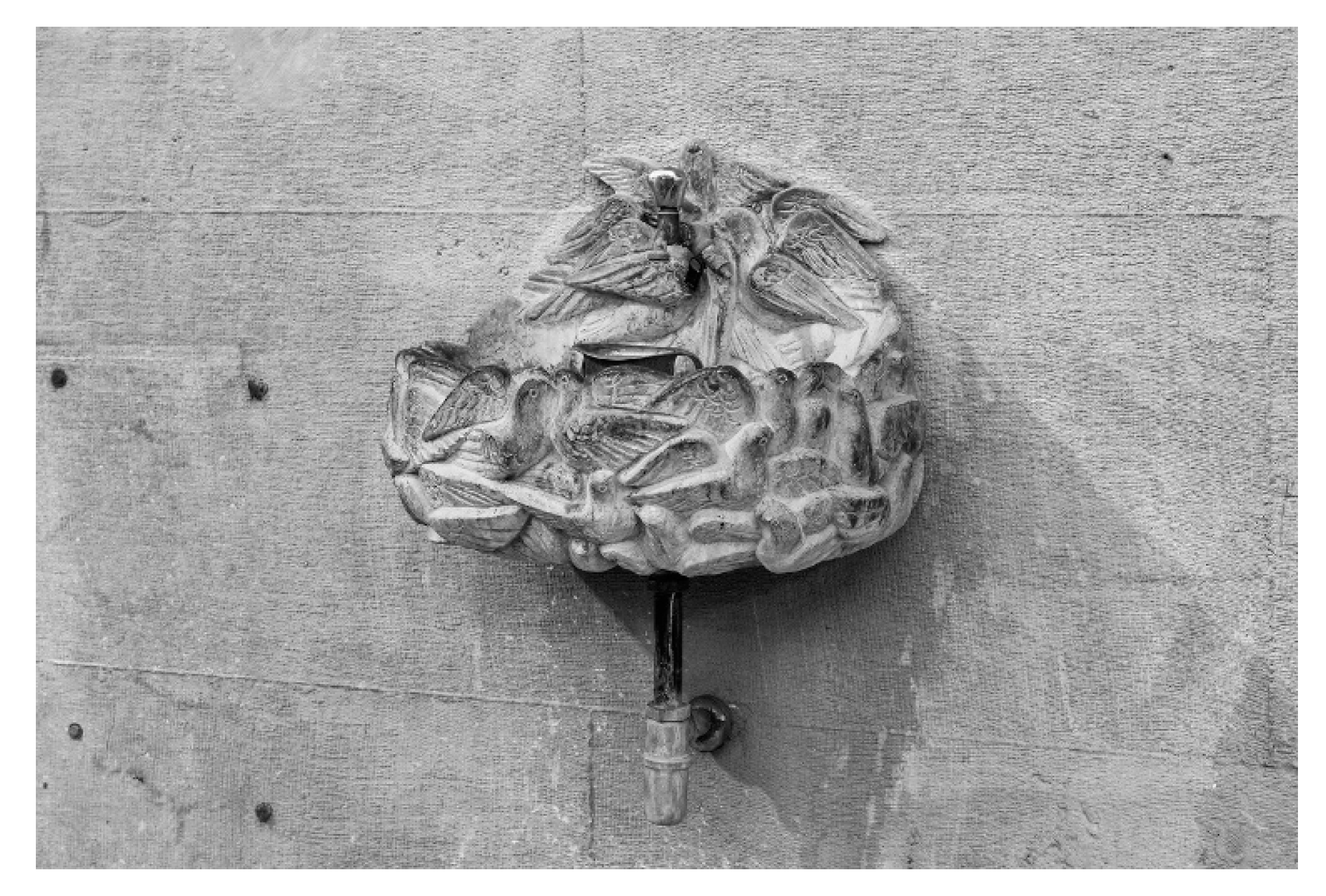

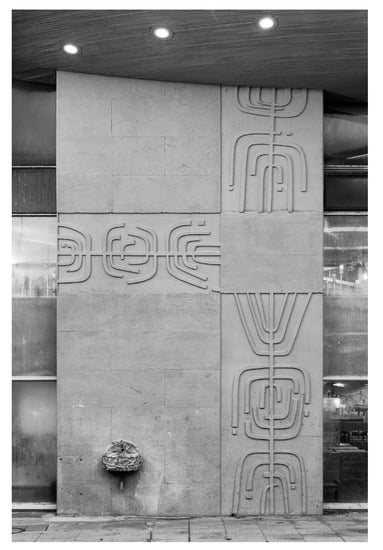

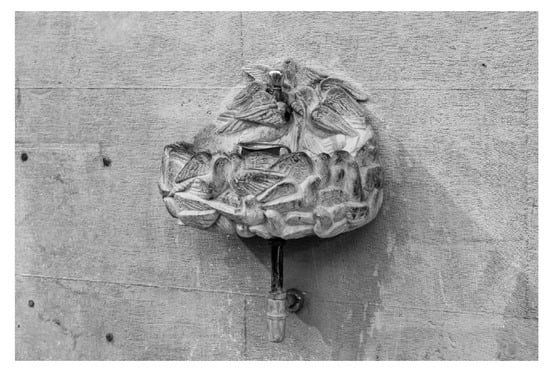

The artworks integrated into the Nazareth Illit synagogue contrast with the Brutalist style of its architecture. The first is a bronze basin created collaboratively by Ruth Tzarfati (1928–2010) and Moshe Sternschuss (1903–1992).14 The basin was installed on an exposed concrete bearing-wall in the synagogue’s lower plaza. The piece features a delicate continuous pattern composed of recurring dove figures (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Of special interest is another art piece that demonstrates the use of concrete as an art material; an abstract relief by Ruth Tzarfati installed on the same wall (Tvai 1970). The relief is composed of a semi-abstract linear pattern, which alludes to the menorah symbol (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Artworks in the courtyard: Ruth Zarfati, relief, ca. 1968. Photo: Eli Singalovski, 2018. Used with permission.

Figure 5.

Artworks in the courtyard: Ruth Zarfati and Moshe Sternschuss, a bronze basin, ca. 1968. Photo: Eli Singalovski, 2018. Used with permission.

Moshe Sternschuss was a trained sculptor, a graduate of the Bezalel Academy of Art in Jerusalem and the École Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, and an influential art teacher. He was a member of the “New Horizons” avant-garde art group, which revolted against the mainstream national art represented by Bezalel. Instead, Sternschuss and the “New Horizons” adopted the abstract style as a universal mode of expression, reflecting their affinity with major international art trends (Hadar 2001, p. 184; Ofrat 2008, pp. 16–18; Fischer and Manor-Friedman 2008, pp. 9–10). Ruth Tzarfati was a prominent versatile artist. She received her art training at the Studio for Painting and Sculpture in Tel Aviv under Moshe Sternschuss, who she married in 1949. In the same year, she joined the “New Horizons” group. Zarfati, a figurative artist, developed an original modern style of her own. Her sculptures are mostly abstract, and characterized by a combination of bursting vitality and clumsiness. Her paintings reflect her spontaneous impressions of sites and figures, and are characterized by inventive use of color (Ronen 2013, pp. 8–14). The two artists’ bodies of work explain the significance of the dove motif on the basin: Mythical and concrete birds appear in Sternschuss’ oeuvre (Hadar 2001, pp. 102–4, 110), iconography which presumably derives from the biblical dove sent out from the ark by Noah (Genesis 8, 6–12). Doves also appear in some of Zarfati’s work (Ronen 2013, pp. 84–88). In Jewish art, the dove image symbolizes the yearning for redemption and salvation (Ofrat 2012).

The menorah has been a Jewish symbol since ancient times. It is first described in the Bible as one of the ark ornaments that God instructs Moses to craft (Exodus 25, 31). As a national symbol, it acquired a Zionist meaning in modern Israel. In his research, Steven Fine explores the resignifications of the symbol, from its iconic representation on the Arch of Titus in Rome, c. 81 CE, to contemporary Israel (Fine 2016, pp. 23, 29–30). Fine demonstrates how, in modern Israel, the menorah was transformed into a symbol of victory and strength by symbolizing the return from “Rome” to Jerusalem. In contrast with the depictions of menorahs found in ancient synagogue mosaics in the Galilee, local to the Nazareth Illit synagogue, its use in this relief embodies the motif of a renewed ancient tradition. The minimalist sculptural use of concrete in this relief stands in contrast to the use of rough concrete in the synagogue’s structure.

The use of concrete and cast bronze as art materials might be perceived as corresponding to the Brutalist architectural style. Rusty steel has been described as a Brutalist art material, similar to exposed concrete, reflecting a secular, physical reaction to earlier mythical and symbolic Israeli sculpture (Baruch 1989). Moreover, concrete sculpture has been said to express the influence of Brutalist architecture on contemporary artists (Ofrat 2017, p. 30; Neumann 2007, p. 429). However, in this case, the minimalistic abstraction endows concrete with a new, poetic and delicate meaning.

The diverse uses of concrete in the design of the Nazareth Illit synagogue are evidence of the tension between nationalism and universalism. At first glance, art and architecture seem both to be exploring Jewish symbols: the dome, the Menorah, and the doves are abstracted religious motifs. However, the difference between the rough use of concrete in the architecture and the delicate concrete synagogue art represents the dialectic of Jewish–Israeli identity. In the contemporary nation-building spirit, adopting Brutalism represented a deep-rooted local identity and strength. Abstract art, on the contrary, was associated with cosmopolitan identity, demonstrating an affinity with the western world. By combining concrete in both architecture and art, the synagogue represents a dual attitude towards the local, national and religious context.

3.2. The Military Officers’ Academy Synagogue in Mitzpe Ramon. Architects: Alfred Neumann and Zvi Hecker, in Collaboration with Naomi Neumann (1967–1969)

Capacity: 120 seats (no women’s section). Prayer style: as the Torah reader chooses. Currently not in use.15

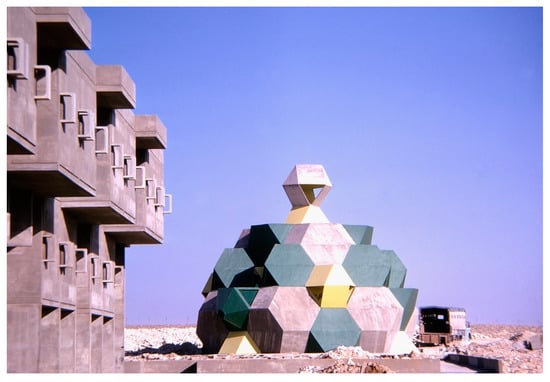

The synagogue is situated at the edge of the central parade ground of the military base and its crystalline structure stands out against the surrounding desert and military landscape (Figure 6). A synagogue located in a military base is a national institution, built and maintained by the state. Former Chief Rabbi of the IDF Mordechai Piron defined military synagogues as educational and spiritual centers for every religious soldier. The military synagogue represents the Torah’s spirit and values and symbolizes the ideals the Jewish People have struggled to maintain throughout history (Piron 1955, pp. 69–74). Architect Zvi Hecker was involved in the preliminary design of the base during his military service in the Israeli Combat Engineering Corps. In the early 1960s, Hecker and his partner Eldar Sharon won a limited architecture competition for the design of the base and were commissioned to carry out the project.16

Figure 6.

The Military Officers’ Academy Synagogue in Mitzpe Ramon. Architects: Alfred Neumann and Zvi Hecker, 1969–1970. Photo: Zvi Hecker. Courtesy of Zvi Hecker, Architect.

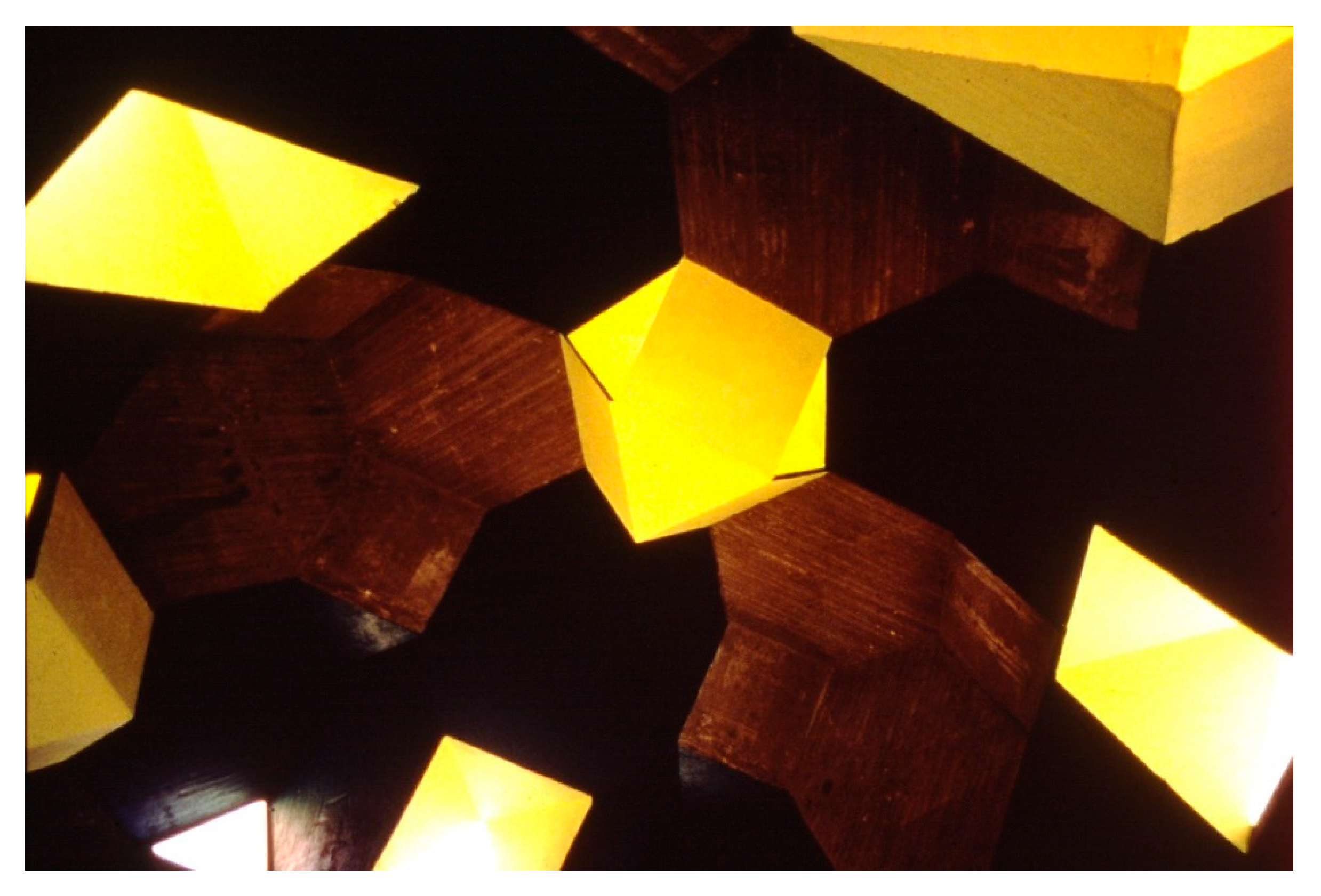

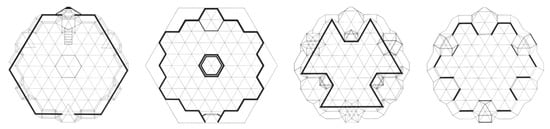

The building is composed of polyhedral spatial bodies, namely, geometrical bodies composed of several identical polyhedrons with hexagonal faces. The synagogue structure is composed of three types of polyhedral units. The basic units are hexagonal planes. Then there are triangular areas formed between the hexagonal planes, where semi-transparent yellow glass windows were installed, allowing the penetration of soft filtered daylight. Zvi Hecker points out that the architects intended the windows to call to mind the delicate flickering light of wooden Polish synagogues.17 The third element is that of ventilation windows, built into sub-octahedrons projecting from the structure (Segal 2011, pp. 544–56).18

The collaborative works of Alfred Neumann (1900–1968) and Zvi Hecker (b. 1931) belong to an experimental trend that flourished in Israeli architecture during the 1960s and 1970s. While the examination of structures composed of recurring basic units suggests the influence of European Structuralism (Efrat 2004, Dvir 2012), Hecker insists that the military synagogue’s building represents Alfred Neumann’s original architectural language rather than a particular European trend.

The architects were inspired by prominent modern European architects such as Adolf Loos and Auguste Perret.19 In his notable manifesto Ornament and Crime (Loos [1908] 1971), Adolf Loos excoriates the decorative Art Nouveau style, and rejects the ornamentation of objects. His ideas are manifestly expressed in the synagogue’s design, where the exceptional morphology functions as the structure’s ornamentation. The architects’ joint works consist mainly of residential and public buildings. The synagogue under discussion is the most striking example of religious architecture among their oeuvre.

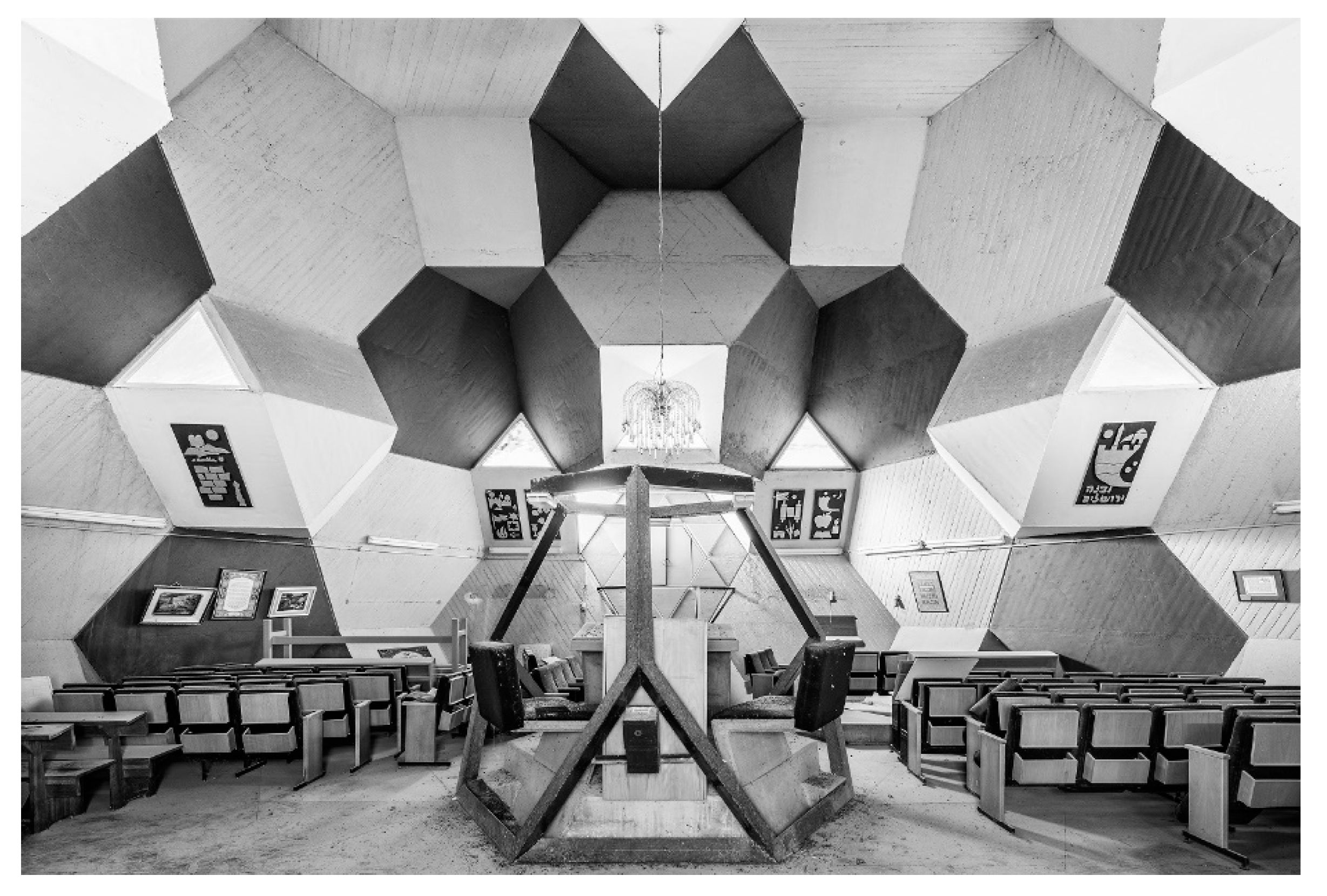

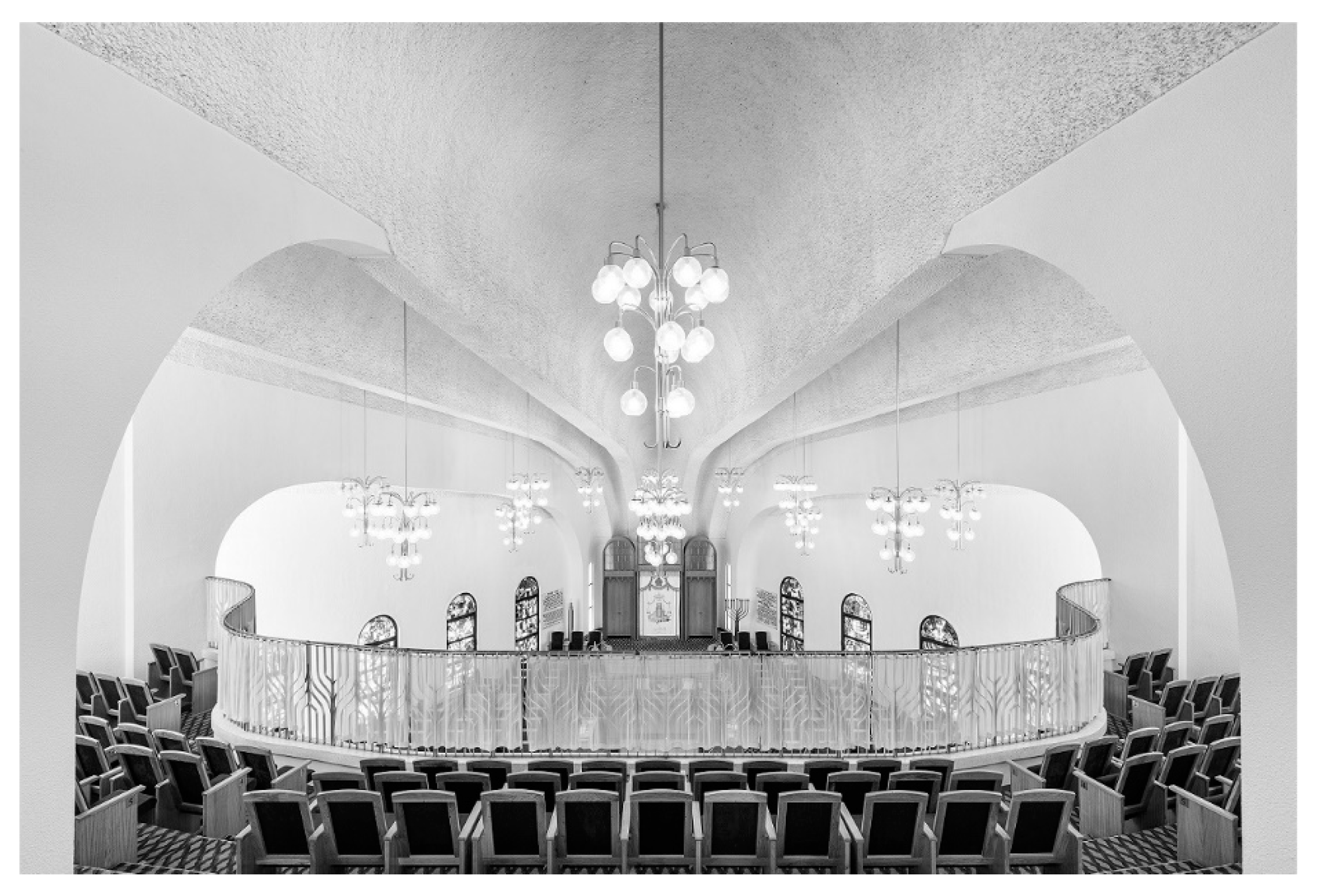

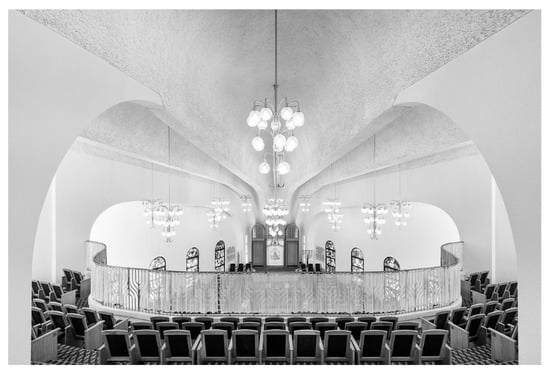

The synagogue’s plan is hexagonal and symmetrical. A central axis connects the entrance, the bimah and the Torah Ark. The benches are arranged in rows on both sides of the central axis so that the worshippers face the Torah Ark. The Ark is positioned against the eastern wall, facing Jerusalem, in an elevated niche that projects from the building. Next to the Ark stands a concrete lectern for Torah reading, with concrete benches on both sides. Situated at the center, the bimah is the focal point of the hall, ascribing religious meaning to the polyhedral architecture. It is enclosed in a metal framework shaped as a regular hexagon, replicating the shape of the structure’s envelope (Figure 7). Since no artworks have been incorporated into the building, unlike in the other reviewed synagogues, I propose that the polyhedral architecture functions and is experienced as an artwork in and of itself. This is particularly noticeable at the front of the wooden Torah Ark, which is shaped as a Star of David. The Ark’s design merges into the geometrical pattern of the concrete planes.

Figure 7.

The Military Officers’ Academy Synagogue in Mitzpe Ramon. Interior view facing the bimah and the Torah Ark. Eli Singalovsky, Bahad 1 #1, 2018. Archival pigment print, 100 cm × 67 cm. Used with permission.

At first glance, the building may be understood as an architectural reflection of the Star of David (Even 1970). However, Hecker affirms that religious symbolism did not dictate the design process. The architects intended the six-pointed star to be projected onto the synagogue’s interior by the flickering light that penetrates through the windows. Thus, the symbol appears as an integral part of the architectural language. Unlike its common use in synagogue design, the Star of David is not an element separate from the architecture.20

Meira Yagid-Haimovici (1996) notices a visual affinity between Neumann and Hecker’s polyhedral structures and Muslim ornamentation (Figure 8). While the Israeli mainstream denied the Middle Eastern cultural landscape, the architects proposed an alternative model by utilizing a multifarious morphology. The architects used geometry as a vehicle for dialogue between diverse sectors of Israeli society.

Figure 8.

The Military Officers’ Academy Synagogue in Mitzpe Ramon. Different forms of the building envelope along the vertical axis. Courtesy of Zvi Hecker, Architect.

A precedent for geometrical explorations that seek to promote mixtures of cultures appears in the works of the early modernist American architect Claude Bragdon (1866–1946). Bragdon argued that “organic architecture” based on nature could cultivate a democratic community within an industrial capitalist society. Jonathan Massey’s examination of Bragdon’s works argues that by harmonizing crystal and arabesque he alluded to a synthesis of different cultures that produces a universal order (Massey 2009, pp. 7–8).

While the Star of David is generally recognized as a symbol of modern Judaism, the history of the hexagram has its origins in earlier Jewish and Muslim depictions of the Seal of Solomon and has been used as a decorative element in Christian churches. Gershom Scholem showed that the Star of David was etched into our collective memory as a symbol of Judaism only when Jews were forced by the Nazi regime to wear a yellow star badge as a mark of disgrace. Only later, when it was emblazoned on Israel’s national flag, did it become a source of pride (Scholem 1949, pp. 243–51). In light of the shifts in the symbol’s meanings, I argue that Neumann and Hecker’s exceptional quotation of the symbol leans on its multicultural history.

The synagogue is exceptional in its dual approach to religious ornamentation. While at first glance the structure appears to reject synagogue decoration, a closer look reveals that the utilization of a complex morphology in the design of ceremonial objects represents a unique blend of synagogue art and architecture. As a whole, the synagogue design reflects an attempt to establish a new local culture: Mediterranean, multicultural and inter-religious.

3.3. Heichal Yehuda Synagogue, Tel Aviv. Yitzhak Toledano (Architect), Aharon Rousso (Structural Engineer), in Collaboration with Architect Amiram Niv, 1980

Capacity: Main prayer hall—400 men and 200 women; secondary hall—a few dozen.

Prayer style: Sephardi.

Interior design: Raphael Blumenfeld and Meir Pintchuk. Stained glass: Joseph Chaaltiel. Relief: Yehezkel Kimchi.

The synagogue was built for the Thessaloniki community (Greece), comprised of families who immigrated to Israel in the 1930s, as well as Holocaust survivors who arrived after World War II. The community members first settled in southern Tel Aviv and later moved to the northern neighborhoods of the city, where there was no Sephardic synagogue. To address this need, the community initiated and funded the construction of the synagogue.21

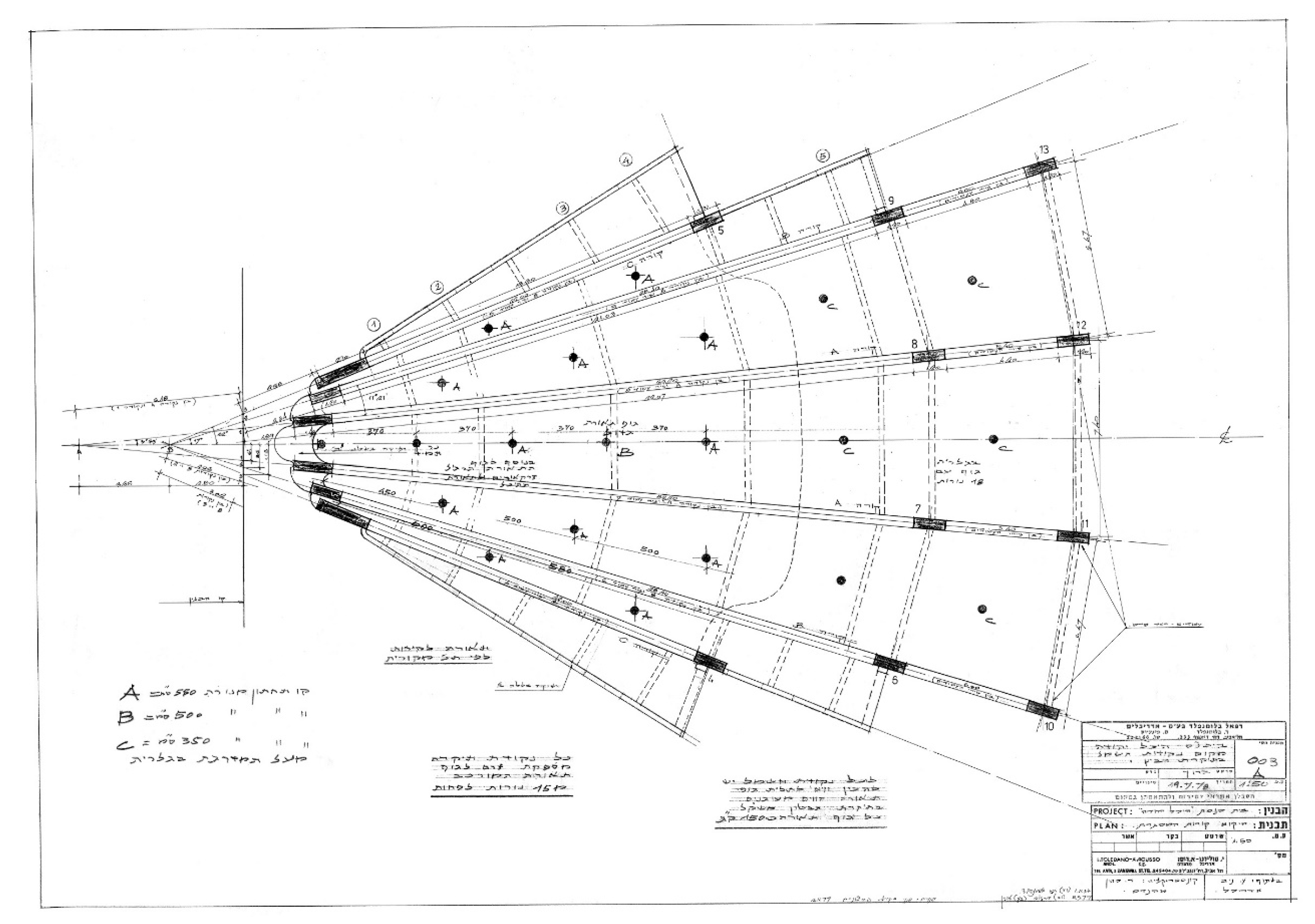

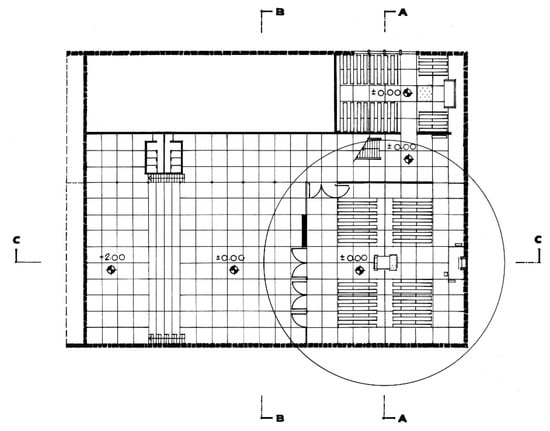

The building comprises two prayer halls as well as classrooms, a commemoration hall, a library and an office (Tvai 1984). The main sanctuary was designated for use on Shabbat and during major Jewish festivals, while the smaller lower-floor hall is used by religiously observant community members on weekdays for prayer.22 The main sanctuary’s design follows the traditional seating arrangement of Sephardic synagogues, and the women’s section is located in a gallery above the entrance (Figure 9) (Krinsky 1985, pp. 21–34).

Figure 9.

Heichal Yehuda Synagogue, Tel Aviv. Yitzhak Toledano (architect), Aharon Rousso (structural engineer), 1978. Plan. Courtesy of Toledano–Rousso Collection.

The designers, architect Yitzhak Toledano (1913–1973) and structural engineer Aharon Rousso (1914–2008), were both members of the Thessaloniki community. They immigrated to Israel together, studied at the Technion in Haifa, and were partners in a firm they established in Tel Aviv.23 Their works mainly include residential buildings, schools, and hotels. Some of their projects were designed for the religious sector, for instance the Deborah Hotel (1964)—the first religious hotel in Tel Aviv, and others for the Thessaloniki community, such as the Leon Recanati Retirement Home in Petach Tikva (1956).

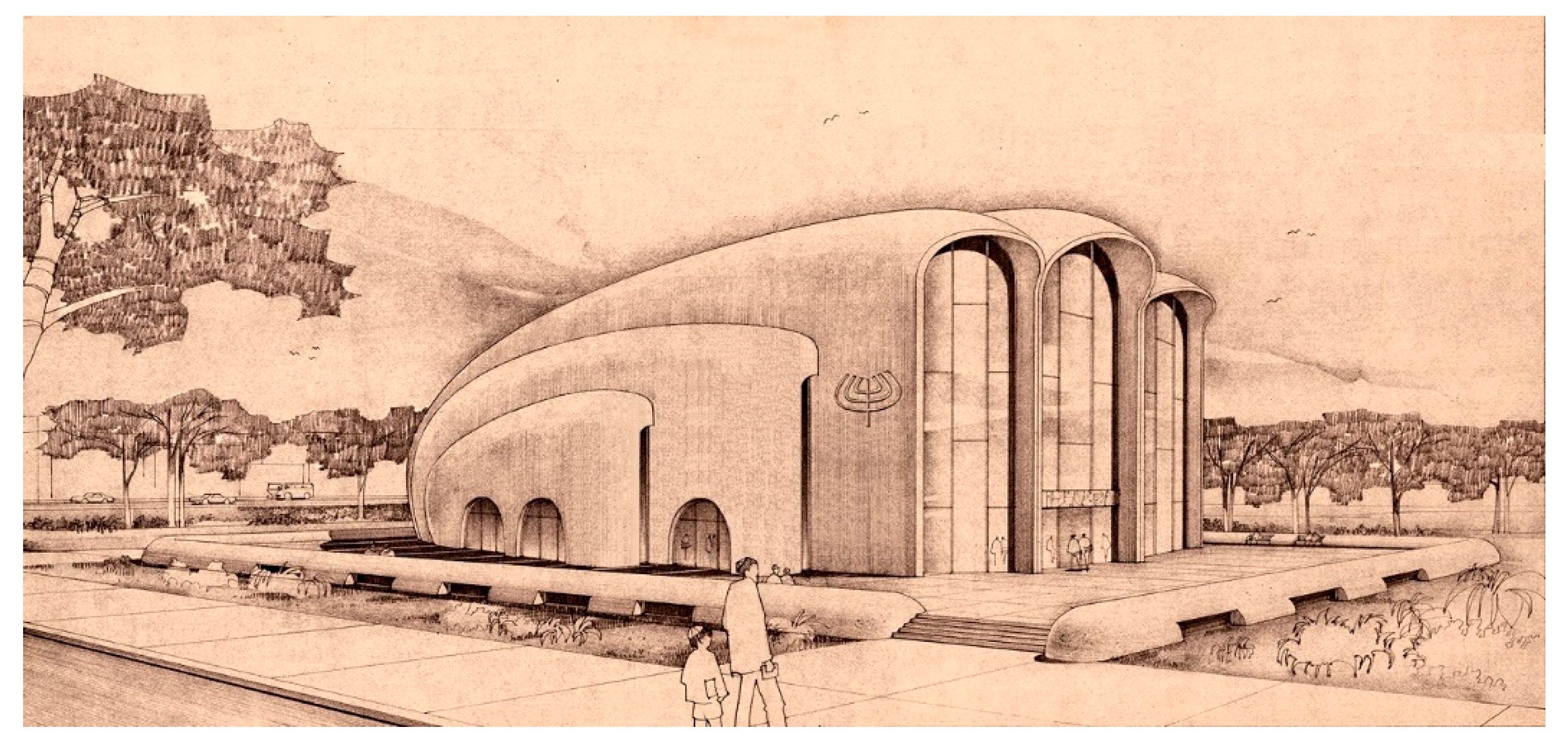

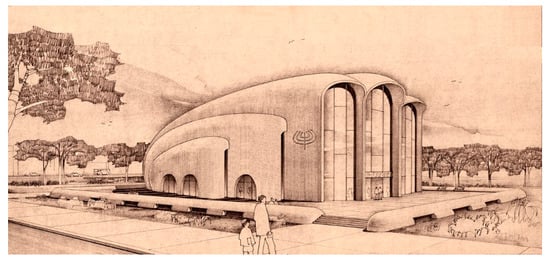

From an aerial view, the building’s shape resembles a shell (Figure 10). The designers chose the seashell motive to evoke the memory of the Thessaloniki seashore, from which the community members had arrived. The shell is considered a religious symbol in many cultures. There are numerous examples of the use of concrete shells in modern religious architecture. One such example is Alvar Aalto’s Church of Holy Spirit (1962) in Wolfsburg, Germany (Weston 1995, pp. 198–225). In ancient Jewish art, the conch motive is a symbol of holiness. Aside from being used as a decorative element in ancient art, the shell has also been used in synagogues throughout history to embellish the round depression above the Torah Ark niche. Over time, this motif became a symbol of this niche in synagogues (Hachlili 1980, pp. 57–65).

Figure 10.

Heichal Yehuda Synagogue, Tel Aviv. Yitzhak Toledano (architect), Aharon Rousso (structural engineer), 1980. Perspective. Architect Norberto Kahan, early 1970’s. Used with permission.

The iconic structure is typical of contemporary postmodernist architecture, aiming to evoke the users’ emotions (Frampton 1983, p. 19). Conversely, the exceptional shape may be interpreted as an expression of secularization. In his seminal discussion of critical regionalism, Kenneth Frampton examined Jorn Utzon’s Bagsvared Church in Denmark (1976), whose main sanctuary’s idiosyncratic design features a reinforced concrete shell vault spanning the nave. According to Frampton, this exceptional design is meant to secularize the sacred shape by precluding the usual set of religious meanings. In so doing, the design reflects the essentially secular age in which it was built, wherein any symbolic allusion was perceived as kitsch, while at the same time proposing a new basis for collective spirituality (ibid., pp. 22–23).

The main structural challenge the architects faced was designing the span of the main sanctuary roof without supporting columns. They solved this problem by designing an envelope that consists of seven adjacent thin concrete barrel vaults, supported by massive beams buttressing each vault and preventing them from collapsing sideways. This structural accomplishment is further emphasized by the vaults’ profiles, which are exposed to the main façade. The vaults stretch from the northern façade and converge towards the southern side of the building, where they curve down to the ground behind the heichal (Torah ark). The convergence point of the symmetrical, shell-like envelope determines the Ark as the focal point of the prayer hall (Figure 11). The main axis, which connects the entrance with the tevah (bimah, a central platform) and the Ark, emphasizes this point. The shell-like shape enhances the acoustics of the main prayer hall, making the Torah reading ring out throughout the space.24

Figure 11.

Heichal Yehuda Synagogue, Tel Aviv. View from the women’s section. Eli Singalovski, Heichal Yehuda #1, 2018. Archival pigment print, 100 cm × 67 cm. Used with permission.

While the synagogue was built for a specific community, the modern structure carries no recognizable sign of its identity. The synagogue’s art, however, comprises explicit expressions of the community’s history and its modern Jewish identity. One such example is an implied representation of Thessaloniki’s White Tower, together with numerous traditional Jewish symbols in Yehezkel Kimchi’s concrete relief on the synagogue’s façade (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Heichal Yehuda Synagogue, Tel Aviv. Left: Yehezkel Kimchi, concrete relief on the synagogue’s façade; right: detail, Thessaloniki’s White Tower. Photos: Eli Singalovski, 2018. Used with permission.

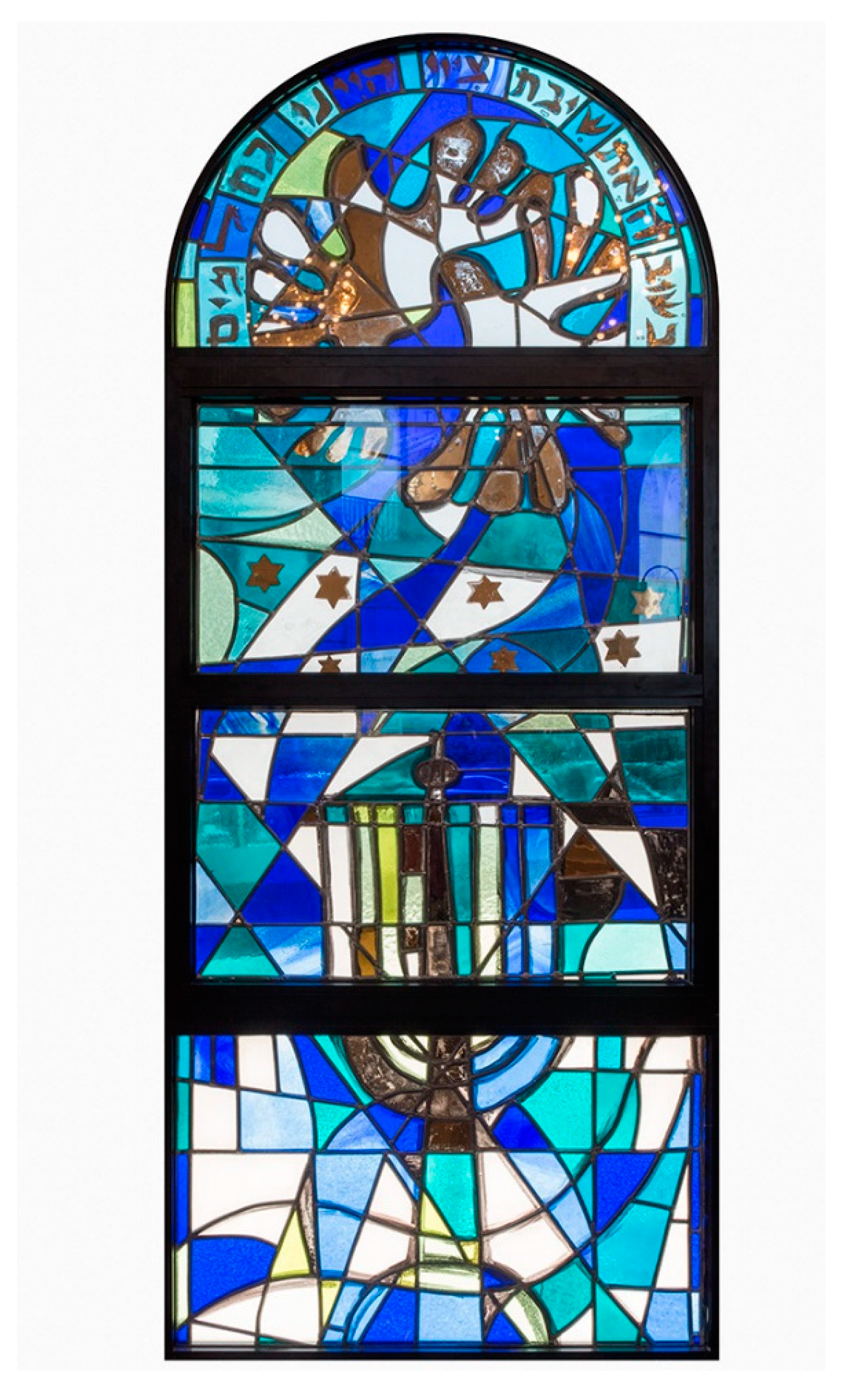

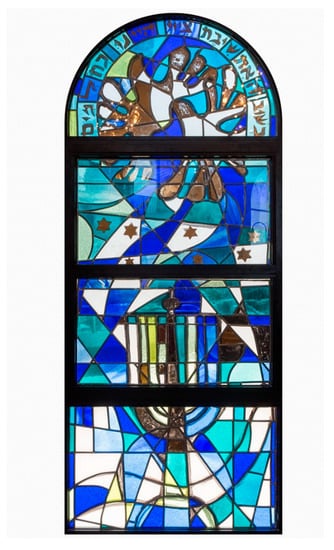

Of particular significance is a series of twelve arched stained-glass windows by Joseph Chaaltiel of Ein Hod (1931 Smyrna–2016 Israel). Chaaltiel was a painter and a prominent stained-glass artist, whose works were incorporated in residential and public buildings. He was a graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice (1959), and of the National College of Applied Arts in Paris (1961). His PhD research at the Sorbonne University, Paris was dedicated to the integration of art in architecture (Chaaltiel 1971).

In Gothic architecture, stained glass windows are thought to represent the idea of “heavenly light” entering a Cathedral through its windows (Chaaltiel 1987, pp. 6–7). In Israel, stained glass windows usually represent biblical scenes, while filtering the glaring sunlight and iluminating and coloring the internal architectural spaces. A significant precedent for stained glass in an Israeli synagogue is Marc Chagall’s windows in the synagogue of Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem (1962). The work comprises twelve arched windows representing the twelve tribes of Israel. The artist described the biblical narratives in a visual language of dream and fantasy.

Chaaltiel’s stained glass windows represent the emergence of a modern Jewish national identity. Their themes include Shabbat, Jewish festivals, and Israel’s Independence Day. Placing Israel’s national day next to the traditional Jewish festivals affirms its position as an inseparable part of the Jewish calendar, representing a Jewish revival in the State of Israel. A closer look at the window depicting Israel’s Independence Day reveals many telling details (Figure 13). The window’s colors recall the national flag. At the top is a quote from Psalm 126:1: “When the Lord brought back those who returned to Zion, we were like men in a dream.” By quoting the Hebrew bible, the artist attaches religious meaning to the national scene. A pair of abstract golden doves appears under the caption. Along with the motif’s allusion to the redemption of the Jewish people, in this context the doves could represent the bond between God, the Jewish people and the land of Israel. Seven golden Stars of David at the center of the scene recall Theodor Herzl’s proposed design for a national flag, introduced in his book The Jewish State (Herzl [1896] 1988), as well as the yellow star Jews had to wear under the Nazi regime. Together, the dual associations linked with the seven-star symbol represent a complex Jewish identity that combines Zionist ideology, post-Holocaust trauma and the revival of the Jewish nation in the State of Israel.

Figure 13.

Heichal Yehuda Synagogue, Tel Aviv. Joseph Chaaltiel, stained glass window (detail). Photo: Eli Singalovski, 2018. Used with permission.

A Hanukkah menorah appears in the lower part of the window. The Hanukkah menorah traditionally symbolizes the miracle of the small cruse of oil that sufficed to light the Temple menorah in Jerusalem for eight days. In Israel’s first years of statehood, the Hanukkah festival was given a new, Zionist interpretation. The Maccabean revolt against the Greeks became an allegory for the bravery and commitment of those who fought for national independence. At that time, the Hanukkah menorah also represented the emblem of the state. The artist uses this ritual object to illustrate that Jewish tradition is the source of Jewish revival in the state of Israel (Behroozi Bar Oz 2014, pp. 68–69; Sabar 2017, p. 433).

While the synagogue was designed for a specific community, its architectural language is mostly universal. The artworks, however, engage unambiguously with modern Jewish themes. The interaction between the shell structure and the art pieces represents a dialogue between the universal and the particular, reflecting the dialectics of the modern Jewish identity, comprised of a traditional heritage, a traumatic past and optimism about the future in the State of Israel.

4. Conclusions

The art and architecture of the three discussed synagogues demonstrates a common tendency for abstraction. Their exceptional appearance was achieved by abstracting traditional religious symbols and the adaptation of contemporary styles. In the Israeli context, this process reflects an attempt to fashion a modern, universal and cosmopolitan Israeli identity that stands in contrast to the earlier “Hebrew” style instituted by Bezalel. The tendency towards abstraction therefore reflects major trends that were dominant in Israel’s first decades of statehood, as well as the re-adoption of traditional Jewish symbols.

The exceptional expressions of Judaism in the reviewed synagogues bring to mind religious historian Mircea Eliade’s discussion of religious representations in modern art (Eliade [1985] 2011). Eliade maintains that the modern artist is faced with the impossibility of expressing a “sacred” experience through traditional religious imagery and symbolism. Consequently, “sacred” expressions in modern art and architecture have become unrecognizable, and are camouflaged within “profane” forms, purposes and meanings, that are no longer expressed in a conventional religious language. While the great majority of artists do not seem to have faith in the traditional sense of the word, Eliade maintains that the sacred, although unrecognizable, is present in their work (ibid., p. 123). The synagogues discussed here reveal the same attitude. Designed by secular artists and architects, these synagogues appear at first glance to renounce religious symbolism. However, as I have shown, their unusual forms articulate new sacred meanings.

Eliade mentions two specific characteristics of modern art: elimination of traditional forms and a fascination with the religious interpretation of the formless (ibid., p. 124). The question arises, then, whether an abstract expression is appropriate in a modern synagogue. Pincus-Witten defines “Jewish abstraction” as formless, saying that it turns any mimetic intention into a complex blur of texture produced in a process of assembly, tagging and erasure (Pincus-Witten 1976, pp. 55–57). In other words, he defines the deconstruction of identical forms and styles as the essence of genuine “Jewish abstraction”.

Pincus-Witten distinguishes between “Jewish abstraction” and “pseudo abstraction”, which distorts its essence. He maintains that pseudo abstraction is characterized by the imitation of prevalent abstracted styles of the early 20th century art movements, mainly Abstract Expressionism, Cubism and Fauvism (ibid., pp. 55–57). The abstract expressionist art movement developed in New York in the 1940s. The movement is associated with the works of notable artists such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman. These artists perceived abstraction as an end in itself, presenting expressions of emotional intensity and anti-figurative aesthetic in their work. However, their work is associated with distinct styles. (Herskovic 2003, pp. 12–13). Pincus-Witten distinguishes between stylistic expressions adopted from major international trends, and genuine abstraction that originates in the artists’ own design process, defining the latter as “Jewish abstraction”. This distinction suggests that an abstraction included in an originally conceived work of art is essentially unique. “Jewish abstraction” is therefore a significant criterion for the evaluation of modern synagogue art and architecture.

As demonstrated in this article, each of the case studies discussed display different extents of Jewish abstraction. This is most clearly articulated in the synagogue of the officers’ academy (Figure 14), where the “formless” expression is derived from the architects’ original design process, which resulted in a strikingly exceptional building. This structure represents a radical expression of the formless “sacred”, namely, of Jewish abstraction.

Figure 14.

The Military Officers’ Academy Synagogue in Mitzpe Ramon, interior, detail. Photo: Zvi Hecker, 1969–1970. Courtesy of Zvi Hecker, architect.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on the author’s on-going PhD research project, supported by the Leo Baeck Fellowship Programme and the Mandel-Scholion Interdisciplinary Research Center in the Humanities and Jewish Studies at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. I deeply thank Architect Nahum Zolotov, Tali Tzuker-Zolotov, Yosef Toister, Rabbi Isaiah Herzel, Architect Zvi Hecker, Ella Zimmerman, Architect Roni Toledano, Levana Eshed, David Recanati, Shimon Tzaiag, and Yair Ben Uri, for their willingness to share their knowledge and thoughts, and for the invaluable archival materials they provided. Special thanks go to. Shalom Sabar and Roy Kozlovsky for their valuable comments on earlier versions of this paper. Many thanks to Eli Singalovski for his permission to include his photographs in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Amir, Tula. 2011. Nahum Zolotov—Architect and City Planner. Tel Aviv: Ama Publications. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Ball, Susan. 1981. Ozenfant and Purism: The Evolution of a Style 1915–1930. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baruch, Adam. 1989. Yechiel Shemi: Secular Sculpture. Tel-Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad. [Google Scholar]

- Behroozi Bar Oz, Nitza. 2014. Local Judaica: Between Tradition and Renewal. In Local Judaica: Between Tradition and Renewal, Exhibition Catalogue. Curated by Nitza Behroozi Bar Oz. Tel Aviv: Eretz Israel Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Bland, Kalman P. 2001. The Artless Jew: Medieval and Modern Affirmations and Denials of the Visual. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Breitberg-Semel, Sara. 1986. The Want of Matter—A Quality in Israeli Art. In The Want of Matter—A Quality in Israeli Art, Exhibition Catalogue. Curated by Sara Breitberg-Semel. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Britton, Karla. 2011. Constructing the Ineffable: Contemporary Sacred Architecture. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chaaltiel, Joseph. 1971. Stained Glass Exhibition Catalogue. Haifa: Haifa Museum of Modern Art, (In Hebrew and English). [Google Scholar]

- Chaaltiel, Joseph. 1987. Art in Glass and Stone: Stained Glass, Mosaic, Enamelmail and Fresco. Jerusalem: Ministry of Education and Culture, the Division of Study Programs. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, William J. R. 1982. Modern Architecture since 1900. Oxford: Phaidon. [Google Scholar]

- Dvir, Noam. 2012. A Look into The Life of the Most Important, Yet Forgotten, Architects. In Haaretz. Available online: http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/features/a-look-into-the-life-of-one-of-israel-s-most-important-yet-forgotten-architects-1.408087 (accessed on 18 January 2018).

- Efrat, Zvi. 2004. The Israeli Project, Construction and Architecture, 1948–1973. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Elhanani, Aba. 1961. Preface. Engineering and Architecture—Association of Engineers in Israel 19: 1. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Eliade, Mircea. 2011. The Sacred and the Modern Artist. In The Religious Imagination in Modern and Contemporary Architecture: A Reader. Edited by Renata Hejduk and Jim Williamson. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 122–25. First published 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Even, Tamar. 1970. A Portrait of a Synagogue as a Concrete Crystal. BaMahane, July 7. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Fine, Steven. 2016. Who is Carrying the Temple Menorah? A Jewish Counter-Narrative of the Arch of Titus Spolia Panel. Images 9: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, Yona, and Tamar Manor-Friedman, eds. 2008. Conversations. In The Second Decade: The Birth of Now-Art in 1958–1968. Ashdod: Ashdod Museum, pp. 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Forty, Adrian. 2012. Concrete and Culture: A Material History. London: Reaktion. [Google Scholar]

- Frampton, Kenneth. 1983. Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance. In The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture. Edited by Hal Foster. Seattle: Bay Press, pp. 9, 16–30. [Google Scholar]

- Geva, Anat. 2012. Frank Lloyd Wright’s Sacred Architecture: Faith, Form and Building Technology. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, Samuel D. 2003. American Synagogues: A Century of Architecture and Jewish Community. New York: Rizzoli. [Google Scholar]

- Hachlili, Rachel. 1980. The Conch Motif in Ancient Jewish art. Assaph: Studies in Art History I: 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- HaCohen, Mordechai, ed. 1955. The Synagogue: Articles and Essays; Jerusalem: Ministry of Religious Services, Government Publishing House. (In Hebrew)

- Hadar, Irith. 2001. Moshe Sternschuss: Volumes and Lines. In Moshe Sternschuss, Exhibition Catalogue. Curated by Irith Hadar. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, pp. 10–154. [Google Scholar]

- Harlap, Amiram. 1985. Synagogues in Israel from the Ancient to the Modern. Tel Aviv: Ministry of Defense and Dvir Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Herskovic, Marika. 2003. American Abstract Expressionism of the 1950s: An Illustrated Survey. Franklin Lakes: New York School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heichal Yehudah Synagogue. 1984. Tvai 22: 70–73. (In Hebrew).

- Herzl, Theodor. 1988. The Jewish State. Translated by Sylvie d’Avigdor. New York: Courier Dover. First published 1896. Available online: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/25282/25282-h/25282-h.htm (accessed on 7 September 2019).

- Kampf, Avram. 1966. Contemporary Synagogue Art: Developments in the United States, 1945–1965. New York: Union of American Hebrew Congregations. [Google Scholar]

- Kandinsky, Wassily. 1946. Concerning the Spiritual in Art. New York: The Solomom R. Guggenheim Foundation. First published 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Kenaan Kedar, Nurith. 2006. Modern Creations from an Ancient Land: Metal Craft and Design in the First Decades of Israel’s Independence, Exhibition Catalogue. Curated by Nurith Kenaan Kedar. Tel Aviv: Erets Israel Museum and Jerusalem: Yad Itzhak Ben Zvi, pp. 11–46. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Rudolf, and Gyorgy Kunszt. 1999. Peter Eisenman: From Deconstruction to Folding. Budapest: Akademiai Kiado, (In Hungarian and English). [Google Scholar]

- Kochan, Lionel. 1997. Beyond the Graven Image: A Jewish View. Basingstoke: Macmillan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krautheimer, Richard. 1994. Synagogues in the Middle Ages. Translated by Amos Goren. Jerusalem: Bialik Institute. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Kravtsov, Sergey, and Vladimir Levin. 2017. Synagogues in Ukraine: Volhynia. Jerusalem: The Zalman Shazar Center for Jewish History. [Google Scholar]

- Krinsky, Carol Herselle. 1985. Synagogues of Europe: Architecture, History, Meaning. New York: Architectural History Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, Lee I. 2000. The Ancient Synagogue: The First Thousand Years. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Loos, Adolf. 1971. Ornament and Crime. In Programs and Manifestoes on 20th Century Architecture. Edited by Ulrich Conrads. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 19–23. First published 1908. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, Jonathan. 2009. Crystal and Arabesque: Claude Bragdon, Ornament, and Modern Architecture. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh. [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz, Israel. 2019. Nazareth Illit Changes Name to Differentiate from Biblical Nazareth. Ynetnews, October 3. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, Lewis. 1925. Towards a Modern Synagogue Architecture. The Menorah Journal XI: 225–36. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, Eran. 2007. The Dialectical Meaning of Form. In Dani Karavan, Retrospective. Edited by Mordechai Omer. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, pp. 845–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ofrat, Gideon. 2008. The dialectic of the 50s: A Hegemony and a Plurality. In The First Decade: A Hegemony and a Plurality. Edited by Galia Bar or and Gideon Ofrat. En Harod: Mishkan le-Omanut En Harod, pp. 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ofrat, Gideon. 2012. Doves of Holiness and of the Spirit of the Times. In Gideon Ofrat’s Storeroom: Texts Archive (Personal Blog). Available online: https://gideonofrat.wordpress.com/ (accessed on 1 October 2019). (In Hebrew)

- Ofrat, Gideon. 2017. Tomarkin’s Concrete. In Anniversary to Mo’av Lookout, Exhibition Catalogue. Curated by Hadas Kedar. Arad: Arad Contemporary Art Center, p. 30. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Olin, Margaret. 2001. The Nation without Art: Examining Modern Discourses on Jewish Art. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pincus-Witten, Robert. 1976. Jewish Art: Six Hypotheses. Mussag: An Art and Culture Monthly 10: 55–57. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Pinkerfield, Jacob. 1945. The Synagogues of Eretz Israel from the End of the Geonim Era to the Rise of Hasidism. Jerusalem: Central Press. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Piron, Mordechai. 1955. The Military Synagogue. In The Synagogue, Articles and Essays. Edited by Mordechai HaCohen. Jerusalem: Hamadpis Hamemshalti, pp. 69–74. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Rodov, Ilia. 2016. What is “Folk” about Synagogue Art? Images: A Journal of Jewish Art and Visual Culture 9: 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronen, Avraham. 2013. Ruth Zarfati: Sculptures and Paintings. In Ruth Zarfati: The Joy of Creation: Sculptures and Paintings, Exhibition Catalogue. Curated by Avraham Ronen and Hagit Sterenshuss Amram. Ramat Gan: Ramat Gan Museum of Art, pp. 8–14. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Roth, Bezalel Cecil. 1974. The Jewish Art. Edited by Bezalel Narkiss. Ramat Gan: Masada. [Google Scholar]

- Sabar, Shalom, ed. 1996. And I Crowned You with Wreaths… The International Judaica Design Competition. Jerusalem: Kal Graf Studio. [Google Scholar]

- Sabar, Shalom. 2017. From the ‘Cruse of Oil Miracle’ to a Rifle Stock: The Changing Image of the Hanukkah Lamp in Israeli society. In Essays in Folklore and Jewish Studies in Honor of Professor Eli Yassif. Edited by Tova Rosen, Nili Aryeh-Sapir, David Rotman and Tsafi Sebba-Elran. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University, vol. 28, pp. 415–49. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Scholem, Gershom. 1949. The Curious History of The Six Pointed Star: How the ‘Magen David’ Became the Jewish Symbol. Commentary 8: 243–51. [Google Scholar]

- Segal, Rafael. 2011. Unit, Pattern, Site: The Space Packed Architecture of Alfred Neumann, 1949–68. Ph.D. dissertation, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Shapira, Anita. 1997. Ben Gurion and the Bible: The Forging of a Historical Narrative. Middle Eastern Studies 33: 645–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simhony, Naomi. 2018. Concrete Folklore. In Concrete Folklore: Experimental Architecture in Israeli Synagogues in the 1960s and 1970s, Exhibition Catalogue. Curated by Naomi Simhony and Dana Gordon. Tel-Aviv: Israel Association of Architects and Urban Planners, (In Hebrew and English). [Google Scholar]

- Simhony, Naomi. 2019. The Modern Israeli Synagogue as an Experiment in Jewish Architecture. In Israel as a Modern Architectural Experimental Lab. Edited by Inbal Ben-Asher Gitler and Anat Geva. Bristol and Chicago: Intellect Books, pp. 173–98. [Google Scholar]

- The Central Synagogue Nazareth. 1970. Tvai 8: 58–61. (In Hebrew).

- Weiser-Ferguson, Sharon. 2012. Forging Ahead: Wolpert and Gumbel Israeli Silversmiths for the Modern Age. Jerusalem: The Israel Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Weston, Richard. 1995. Alvar Aalto. London: Phaidon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wischnitzer, Rachel. 1955. Synagogue Architecture in the United States: History and Interpretation. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America. [Google Scholar]

- Yagid-Haimovici, Meira. 1996. Zvi Hecker: The Stance of the Other—An Alternative to Conventional Practice. In Zvi Hecker—Sunflower, Exhibition Catalogue. Curated by Meira Yagid-Haimovici. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Zalmona, Yigal. 1998. To the East? To the East! On Orientalism in the Arts in Israel. In To the East: Orientalism in the Arts in Israel, Exhibition Catalogue. Curated by Yigal Zalmona and Tamar Manor-Friedman. Jerusalem: The Israel Museum. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | This paper is based on the author’s ongoing PhD research at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, which investigates synagogue architecture in Israel’s first decades of statehood and its contribution to the consolidation of a new Jewish national identity. |

| 2 | For a broader discussion of deconstruction in contemporary Jewish architecture, see (Klein and Kunszt 1999). |

| 3 | Given the limited research dedicated to Israeli synagogue art, I refer here to literature dedicated to American synagogues, which share certain building circumstances and expressions with Israeli synagogues (Kampf 1966, pp. 26, 27, 49, 52). |

| 4 | See for example (Levine 2000; Pinkerfield 1945; Krautheimer 1994; Kravtsov and Levin 2017). |

| 5 | See for example (Wischnitzer 1955; Krinsky 1985; Gruber 2003; Britton 2011; Geva 2012; Klein and Kunszt 1999). |

| 6 | See for example (Kampf 1966; Roth 1974; Sabar 1996; Bland 2001; Olin 2001; Weiser-Ferguson 2012; Rodov 2016). |

| 7 | See for example (Breitberg-Semel 1986; Zalmona 1998; Fischer and Manor-Friedman 2008). |

| 8 | In 2019, the city was renamed Nof HaGalil (Galilee Landscape). In the present article, I use its previous name. See (Moskowitz 2019). |

| 9 | “Nazareth’s Synagogue—Conditions of the Open-Limited Competition,” 24.7.1959, Meir Ben Uri Archive, Haifa, “Nazareth, materials for the design competition and jury protocol. 320.10-0”. (In Hebrew) |

| 10 | Ibid. |

| 11 | Nahum Zolotov, interviewed by the author, Hod HaSharon, 9 November 2009. |

| 12 | Other synagogues designed by Zolotov include the Inter-Communal Synagogue in Be’er-Sheva (1958), and the Babylonian Community synagogue in Be’er-Sheva (1980) (Amir 2011, p. 5). |

| 13 | Nahum Zolotov, interviewed by the author, Hod Hasharon, 9 November 2009. |

| 14 | Hagit Sternschuss Amram, daughter of Sternschuss and Zarfati, telephone interview by the author, 21 August 2019. |

| 15 | In 2009, a new synagogue building designed by architect Eli Armon was inaugurated at this military base. |

| 16 | Zvi Hecker, interviewed by the author, Ramat Gan, 6 January 2019. |

| 17 | Zvi Hecker, interviewed by the author, Ramat Gan, 28 December 2015. |

| 18 | http://www.zvihecker.com/projects/synagogue _in_the_negev_desert-60-1.html (accessed on 20 October 2019). |

| 19 | Zvi Hecker, interviewed by the author, Ramat Gan, 3 December 2017. |

| 20 | Ibid. |

| 21 | Levana Eshed, interviewed by the author, Tel Aviv, 20 February 2017; David Recanati, interviewed by the author, Tel Aviv, 6 March 2017. |

| 22 | Levana Eshed, interviewed by the author, Tel Aviv, 20 February 2017. |

| 23 | Levana Eshed, interviewed by the author, Tel Aviv, 20 February 2017; David Recanati, interviewed by the author, Tel Aviv, 6 March 2017. |

| 24 | Ibid. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).