Constructing Digital Game Exhibitions: Objects, Experiences, and Context

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Game Artifacts in Exhibitions

2.2. Exhibited Games as Interactive Experiences

A museum is a non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education, study and enjoyment.

2.3. Beyond Original Experiences

Visitors come to museums with their own agendas and construct their own meanings within museums. Regardless of what the museum staff intend, visitors’ different expectations, previous museum experiences, and levels of perceptual skills mean that museum experiences is often personal and individual rather than standard and generic.

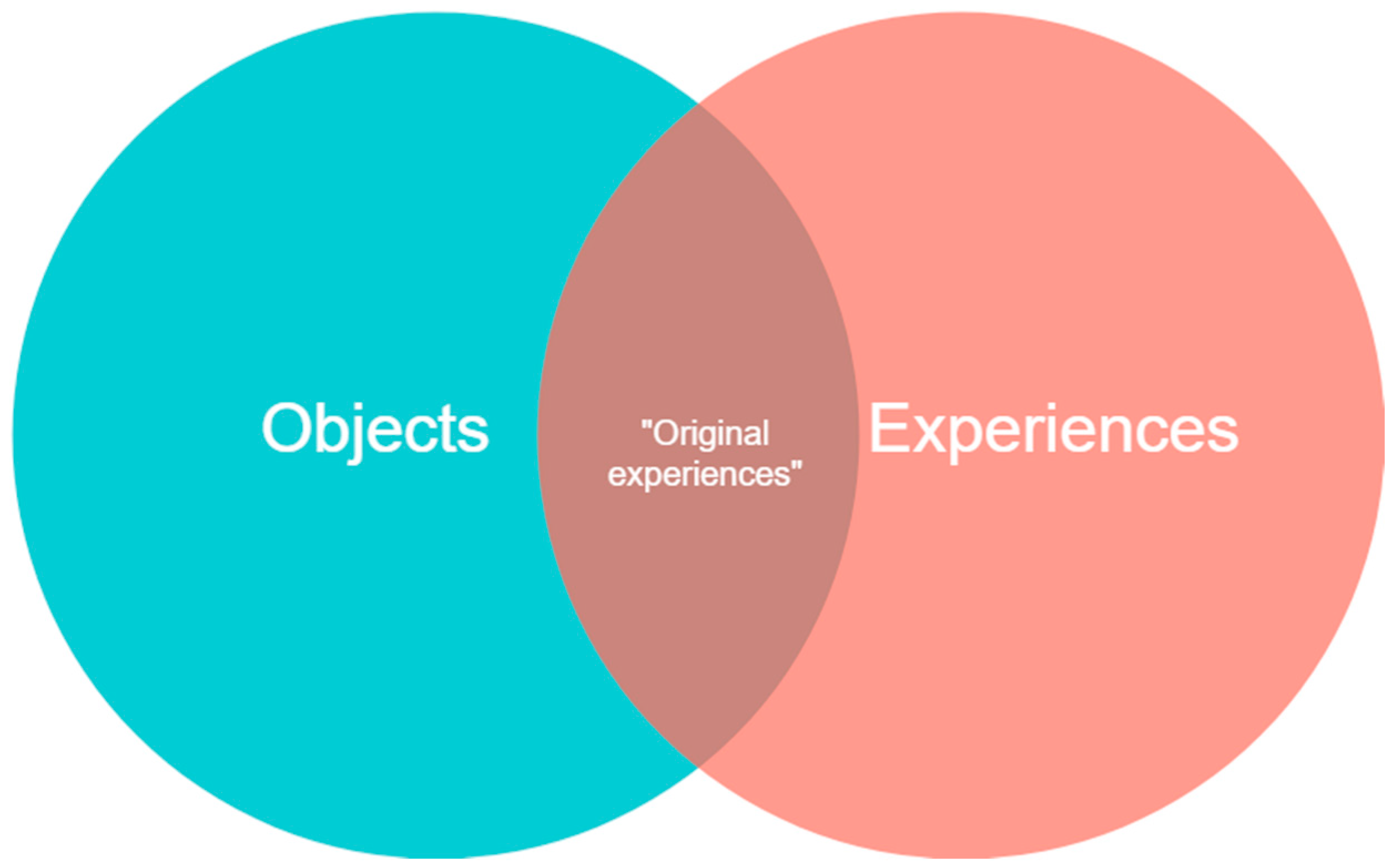

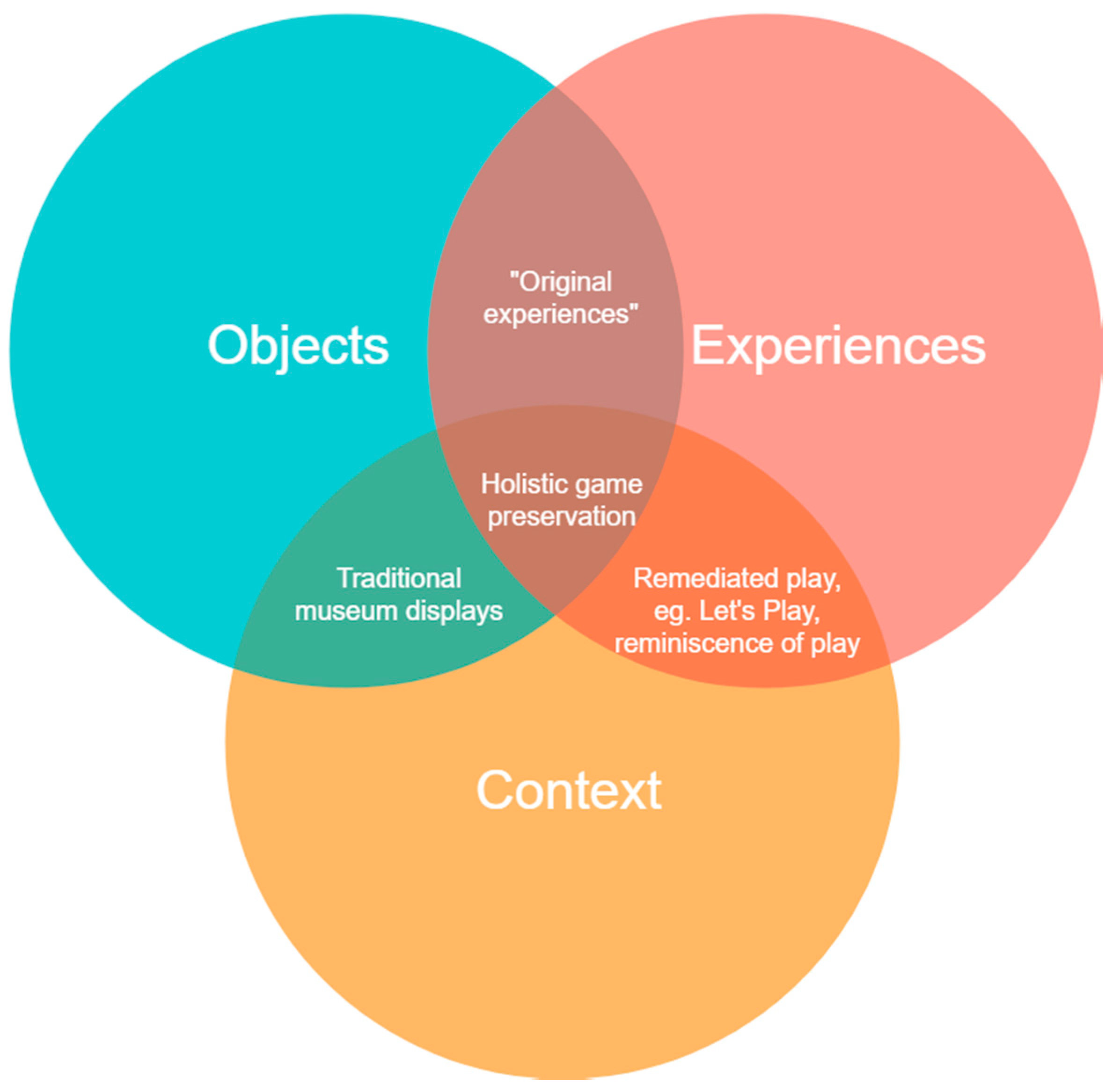

(W)hile it is desirable to present playable original games in an exhibition it cannot be expected that visitors will have the same experience as players had with the game in its historical context and it is questionable whether providing playable games on original hardware is enough to achieve the objects of game preservation and exhibition.

2.4. Context in Game Exhibitions

2.5. Understanding Games on Display

3. Discussion

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

Ludography

Inva-Taxi (1994), Åkesoft.Max Payne (2001), Remedy Entertainment.Propilkki (1999), Procyon Productions.Raharuhtinas (1984), Amersoft.Super Mario Bros. (1985), Nintendo.Supernauts (2013), Grand Cru.Where in Time is Carmen Sandiego? (1989), Broderbund.Exhibitions Mentioned

Applied Design/The Museum of Modern Art (MoMa). New York, NY. 2013–14Computerspielemuseum. Berlin, Germany. 2011–eGameRevolution/Strong National Museum of Play. Rochester, NY, 2010–Game On/Travelling exhibition produced by Barbican International Enterprises, 2002–Game On 2.0/Travelling exhibition produced by Barbican International Enterprises, 2010–National Videogame Museum. Frisco, TX. 2016–Nexon Computer Museum. Jeju Island, South Korea. 2013–Play Beyond Play/Tekniska Museet. Stockholm, Sweden. 2018–The Finnish Museum of Games. Tampere, Finland. 2017–Bibliography

- Bettivia, Rhiannon. 2016. Enrolling Heterogeneous Partners in Video Game Preservation. International Journal of Digital Curation 11: 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogost, Ian. 2009. Videogames Are a Mess. Keynote at the 2009. Paper presented at the Digital Games Research Association (DiGRA) Conference, Uxbridge, UK, 1–4 September; Available online: http://bogost.com/writing/videogames_are_a_mess/ (accessed on 30 October 2018).

- Chang, EunJung. 2006. Interactive Experiences and Contextual Learning in Museums. Studies in Art Education 47: 170–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consalvo, Mia. 2017. When Paratexts Become Texts: De-Centering the Game-as-Text. Critical Studies in Media Communication 34: 177–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desvallées, André, and François Mairesse. 2010. Key Concepts of Museology. Paris: Armand Colin. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, John. 1916. Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. London: Macmillan Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, Sandra H., ed. 2010. Museum Materialities: Objects, Sense and Feeling. In Museum Materialities: Objects, Engagements, Interpretations. London: Routledge, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- EmuVR. 2018. About | EmuVR—Virtual Emulation. n.d. Available online: http://www.emuvr.net/about/ (accessed on 27 October 2018).

- Falk, John H, and Lynn Dierking. 2013. The Museum Experience Revisited. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Fornäs, Johan. 1998. Digital Borderlands: Identity and Interactivity in Culture, Media and Communications. Nordicom Review 19: 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, James J. 2011. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception, 17th pr ed. New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guins, Raiford. 2014. Game After—A Cultural Study of Video Game Afterlife. Cambridge: MIT Press, vol. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Guttenbrunner, Mark, Christoph Becker, and Andreas Rauber. 2010. Keeping the Game Alive: Evaluating Strategies for the Preservation of Console Video Games. International Journal of Digital Curation 5: 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggbloom, Steven J., Renee Warnick, Jason E. Warnick, Vinessa K. Jones, Gary L. Yarbrough, Tenea M. Russell, Chris M. Borecky, Reagan Mcgahhey, John L Powell III, Jamie Beavers, and et al. 2002. The 100 Most Eminent Psychologists of the 20th Century. Review of General Psychology 6: 139–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, George E., and Mary Alexander. 1998. Museums: Places of Learning. Professional Practice Series; Washington: American Association of Museums. [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen, Mikko. 2017. From Our Garage to the Finnish Museum of Games-History in the Making. Skrolli International Edition 1E: 82–83. [Google Scholar]

- International Committee of Museums (ICOM). 2007. Article 3—Definition of Terms/Section 1 (ICOM Statutes Art.3 Para.1). Paris: ICOM. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, Graeme. 2012. Constitutive Tensions of Gaming’s Field: UK Gaming Magazines and the Formation of Gaming Culture 1981–1995. Game Studies 12. Available online: http://gamestudies.org/1201/articles/kirkpatrick (accessed on 30 October 2018).

- Lowood, Henry. 2014. It Is What It Is, Not What It Was. Keynote address at Born Digital and Cultural Heritage Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 19 June; Available online: http://refractory.unimelb.edu.au/2016/08/30/henry-lowood/ (accessed on 30 October 2018).

- Naskali, Tiia, Jaakko Suominen, and Petri Saarikoski. 2013. The Introduction of Computer and Video Games in Museums—Experiences and Possibilities. In Making the History of Computing Relevant. Edited by Arthur Tatnall, Tilly Blyth and Roger Johnson. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 226–45. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, James. 2012a. Best before: Videogames, Supersession and Obsolescence. Milton Park and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, James. 2012b. Ports and patches: Digital games as unstable objects. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 18: 135–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, James, and Iain Simons. 2018. Game Over? Curating, Preserving and Exhibiting Videogames: A White Paper. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/11vWx_5LMK6qxW-3rqqvB-MemW6Sk-Ep3/view (accessed on 30 October 2018).

- Nexon Computer Museum. 2014. 컴퓨터, 세상을 바꾼 아이디어 = (The) computer, an idea that changed the world. vol. 0–1, Jeju-do: Nexon Computer Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund, Niklas. 2015. Walkthrough and Let’s Play: Evaluating Preservation Methods for Digital Games. New York: ACM Press, pp. 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylund, Niklas. 2017. Preserving Game Heritage with Video Interviews: A Case Study of the Finnish Museum of Games. In Finskt Museum. Helsinki: Suomen muinaismuistoyhdistys, pp. 8–27. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer, Frank. 1968. A Rationale for a Science Museum. Curator: The Museum Journal 11: 206–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Rietz, Peter, ed. 2018. Dataspelens Världar: Digitala Spel Som Kultur Och Kulturarv. Stockholm: Tekniska museet. [Google Scholar]

- Prax, Patrick, Björn Sjöblom, and Lina Eklund. 2016. GameOff: Moving Beyond the ‘Original Experience’in the Exhibition of Games. SIRG Research Reports 2016: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Reino, Juan. 2017. Pac-Man and Tetris alongside Picasso and Van Gogh. A Comparative Approach to Preservation of Video Games in Museums. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/36171603/Pac-Man_and_Tetris_alongside_Picasso_and_Van_Gogh._A_comparative_approach_to_preservation_of_Video_Games_in_Museums (accessed on 26 October 2018).

- Schmitt, Stefan. 2007. Half a Century of Digital Gaming: ‘Game On’, at the Science Museum, London, 21 October 2006–25 February 2007. Technology and Culture 48: 582–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Barbara, and Nicole Cheslock. 2003. Measuring Results: Gaining Insight on Behavior Change Strategies and Evaluation Methods from Environmental Education, Museum, Health, and Social Marketing Programs. San Francisco: Coevolution Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Sicart, Miguel. 2014. Play Matters. Playful Thinking. Cambridge and London: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Siefkes, Martin. 2012. The Semantics of Artefacts: How We Give Meaning to the Things We Produce and Use. In Themenheft Zu Image 16: Semiotik. Vol. Part 1 (“Principles of semantization,” section 1–3). Köln: Herbert von Halem Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Sköld, Olle. 2018. Understanding the ‘Expanded Notion’ of Videogames as Archival Objects: A Review of Priorities, Methods, and Conceptions. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 69: 134–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Laurajane. 2006. Uses of Heritage. London and New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Sotamaa, Olli. 2014. Artifact. In The Routledge Companion to Video Game Studies. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenros, Jaakko, and Annika Waern. 2011. Games as Activity: Correcting the Digital Fallacy. In Videogame Studies: Concepts, Cultures and Communication. Oxford: Inter-Disciplinary Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, John. 1991. The Long-term Impact of Interactive Exhibits. International Journal of Science Education 13: 521–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swalwell, Melanie Lorraine. 2013. Moving on from the Original Experience: Games History, Preservation and Presentation. Available online: https://dspace.flinders.edu.au/xmlui/handle/2328/35513 (accessed on 30 October 2018).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). 2003. Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Paris: UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The term digital game is used throughout. It is understood as a concept covering all games played on digital devices, e.g., mobile games, computer games, console games, and online games. |

| 2 | Swalwell (2013, p. 11) presents a critical reading of the disparate problems the “original experiences” approach advances and juxtaposes “original experiences” with a “critical historical and scholarly understanding”. According to Swalwell (ibid., 4), the “original experiences” approach is “popular writing about games history, in journalistic pieces or enthusiasts’ forums, rather than in the writing of scholars or critical game historians”. |

| 3 | There are many different degrees of interactive experiences. A TV set can be switched on or off and the content can be changed with a remote controller, but it is only when the TV is connected to a game console or similar piece of interactive technology that the user can interact with the content. In addition, digital interactivity and physical hands-on have differences that this study will not deal with in more detail (cf. Fornäs 1998). |

| 4 | As seen in e.g., Computerspielemuseum, the Finnish Museum of Games or the National Videogame Museum. |

| 5 | EmuVR is a “VR simulation of those good old nostalgic days just playing video games in your room” which features authentic models of period rooms and game emulation embedded into a VR experience (EmuVR 2018). |

| 6 | Raharuhtinas (1984), one of the oldest published digital games from Finland, is a maze exploration game that assumes the player is drawing a map of her progress (Nylund 2015, p. 61). Where in Time is Carmen Sandiego? (1989) requires the use of a printed encyclopedia “as a source of historical, geographical, and cultural information for players seeking to solve the game’s virtual scavenger hunt puzzles” (Newman and Simons 2018, p. 16). Without the map or the encyclopedia, the games are nigh impossible to complete. |

| Game/Aspect | Experience | Object | Context of Play | Context of Development | Context of Public Reception |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inva-Taxi (1994) | No/Content deemed unethical by exhibition curators | No | Gameplay footage shown in documentary | No/Game developers refused to speak publicly | Conversation between game educator Mikko Meriläinen and disability rights activist Amu Urhonen |

| Propilkki (1999) | Playable game/Propilkki 2 1.1.5 on original hardware with a unique map made for the exhibition | PC used for making the graphics of the first version | Cardware cards from around the world | Developer interview with graphic and level designer Mikko Happo | No |

| Max Payne (2001) | Playable game/Original hardware | Retail boxes of Max Payne (2001) and Max Payne 2 (2003) | No | Developer interview with writer Sami Järvi | No |

| Supernauts (2013) | No/Closed servers | Yes/Fan made crochet character | No | Yes/Concept art | No |

| Example of content | Playable game (original hardware, emulation) | Retail box, original console | Let’s Play video, video or photograph of play | Developer interview, design document | Review, forum discussion |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nylund, N. Constructing Digital Game Exhibitions: Objects, Experiences, and Context. Arts 2018, 7, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040103

Nylund N. Constructing Digital Game Exhibitions: Objects, Experiences, and Context. Arts. 2018; 7(4):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040103

Chicago/Turabian StyleNylund, Niklas. 2018. "Constructing Digital Game Exhibitions: Objects, Experiences, and Context" Arts 7, no. 4: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040103

APA StyleNylund, N. (2018). Constructing Digital Game Exhibitions: Objects, Experiences, and Context. Arts, 7(4), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040103